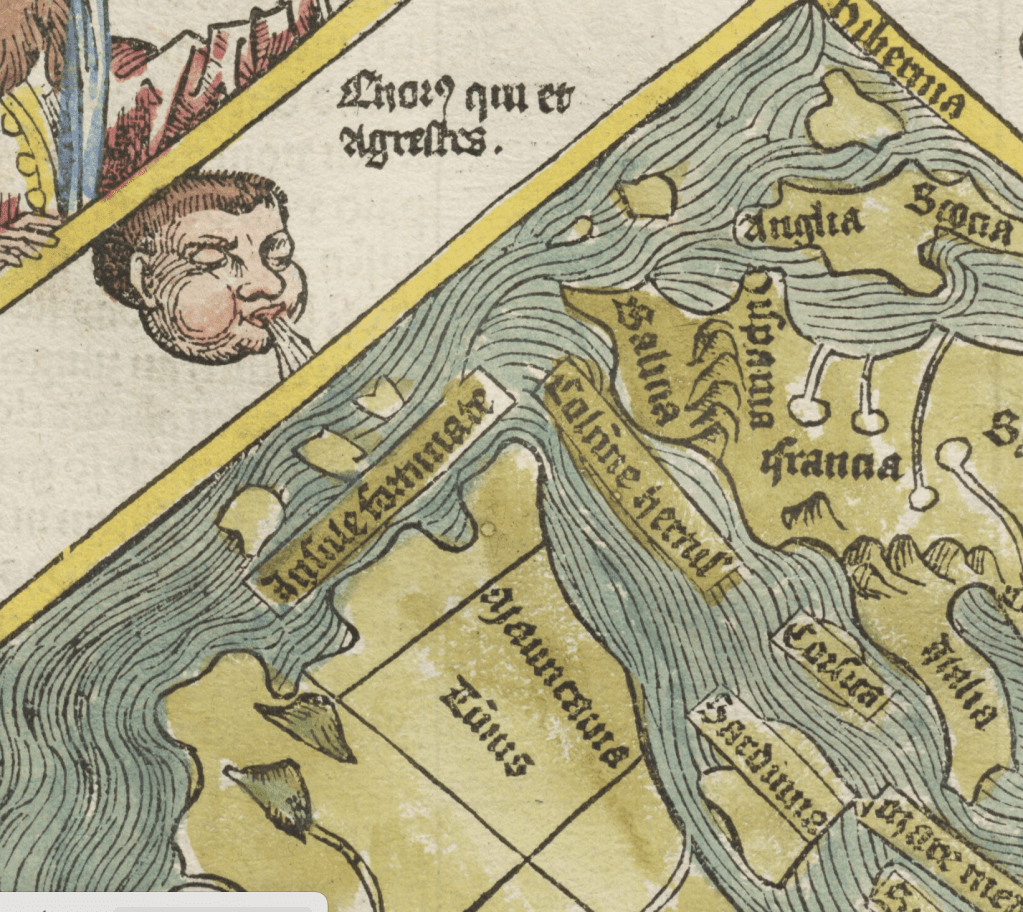

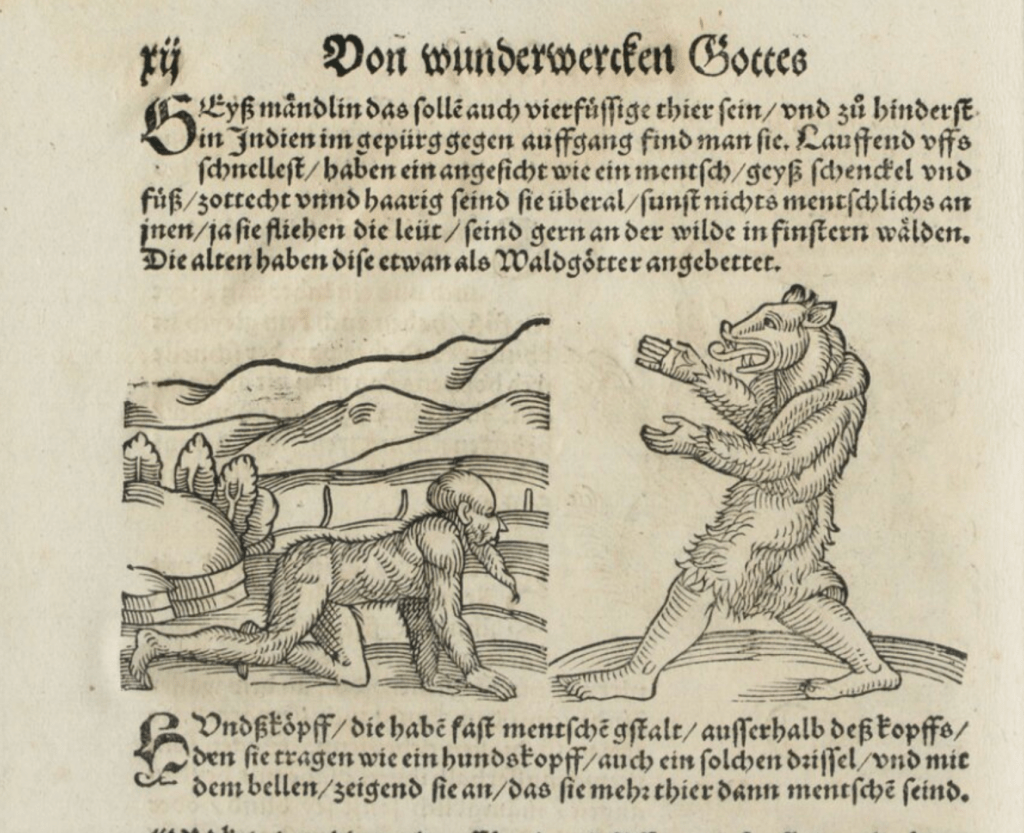

As non-human animals inhabited the edges of the inhabited world in medieval cosmologies, it may be unsurprising that the MAGA candidate who has done much to resurrect the contours of theocratic neo-medieval maps perpetuated stories of the consumption of pet dogs–the “pets of the people who live here”–as the latest hidden news fallen under the radar that he dredged up from the darker reaches of the internet. Donald Trump has long supercharged fears of migrants before the 2024 Presidential election. But the claim that Haitian immigrants who arrived illegally in Ohio were eating the pet dogs and cats of American citizens was a Hail Mary move of the 2024 election. As much as merely re-presenting the dark face of immigration unfurled as the banner of Trump’s 2016 Presidential campaign, delivered as he descended the golden escalator in Trump Tower, the fake news Trump was pedaling without foundation evoked an anxiety dating from the discovery of the New World, and the image of dog-headed men on the margins of comfort and of the inhabited world was registered in the first world maps,–not even intended to be truthful, but hoped to sell books that narrated a global history in the first age of the printed book–

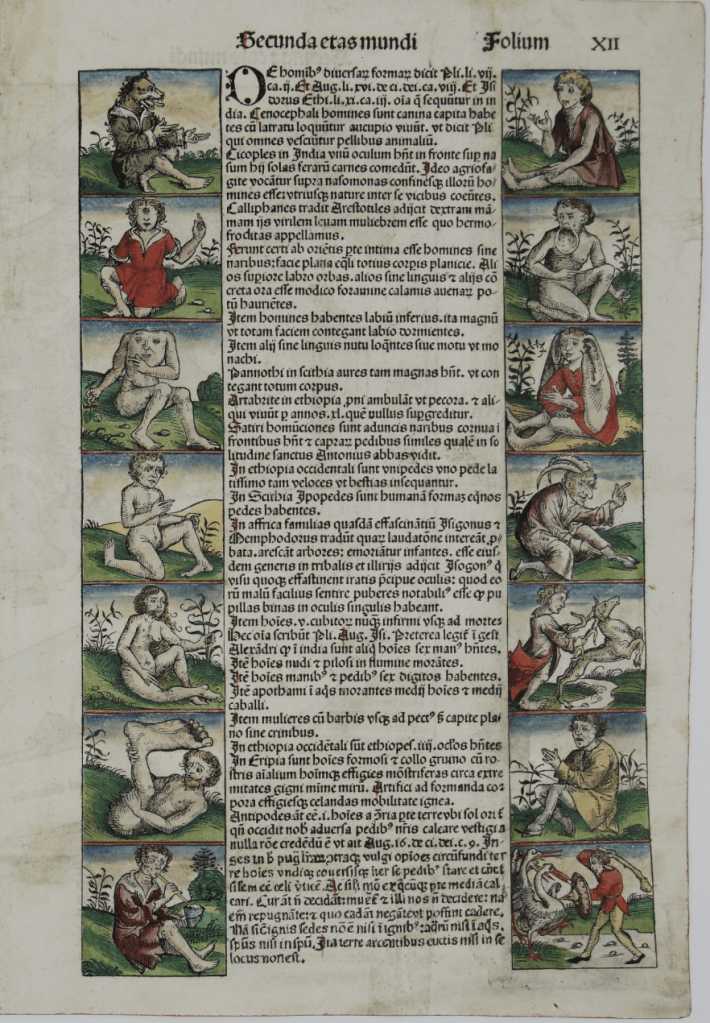

Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

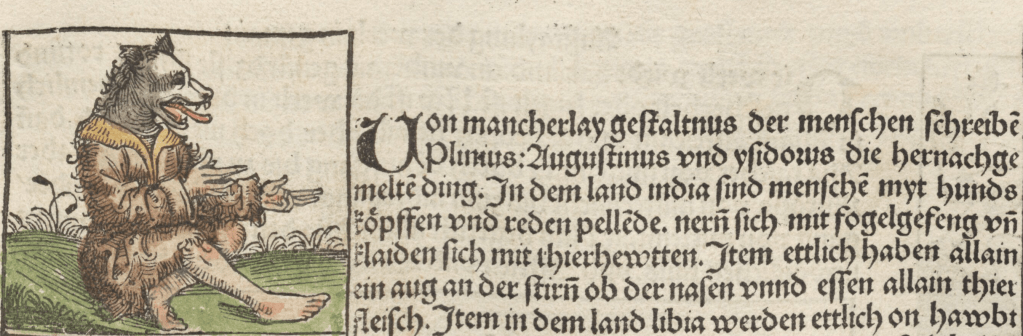

–as a facile combination of the barely credible that courted anxieties of the unknown. The telling combination of the cartographic and hysteric, announcing discovery of New Lands with evocation of monstrous races off of its margins, drawn from a repertoire of medieval mythology, by presenting the new worries of the Modern Age in circa 1493, featuring not only a range of fantastic creatures–from monopods, headless men whose mouths were situated in their chests, to creatures with a large single foot, but human-like creatures on the margins of the known with heads of dogs.

Monstrous Races on the Edges of the New World and Beyond, Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

And as much as the unfounded charges that Trump evoked in his bid to be U.S. President had a basis in law, or pretended to be grounded in fact, they trafficked in rumor and stereotype, drawn from the oldest anxieties of threats to stability and knowledge, myths of existential threats more than actual dangers, and a premonition of the baseless charges and illegal conduct and disrespect for legal norms that the Trump Presidency would encourage and indeed make its brand. While widely identified as from the internet, and quickly decried by local city authorities in Springfield as scurrilous, the outrageous charges held weight among all terrified to admit Haitians into the United States, as if an existential terrors to the American families that captured the charges of criminality and deviance identified with the immigrants accepted from below the southern border. The absurd claim was lent currency in the debate as valid evidence of the dangers migrants posed to residents of in the bucolically named Springfield, Ohio, was unfounded and without documentation. The theater of fear, and the theater of the unknown, was however the theater of American politics, at the start of a new Information Age stunningly removed from fact, but enmeshed in if not parasitic on maps.

But the imaginary dangers to “people who live there” have been accentuated, with brutal and compelling stories related to migrants retold to create a sense that the country is under attack, in ways that takes voters’ eyes off of the role that the United States might play to bolster regional security rather than build walls and deny asylum to migrants seeking to flee political persecution. In response to a question about immigration, the pivot to eating dogs was presented as evidence of fears that the twenty-thousand immigrants from Haiti in Springfield, Ohio, launched for all its absurdity as an attempt to resurrect fears of immigration across America, as a specter of the flouting of American values and identity across the border, and taking advantage of an alleged “open borders” policy that put America at risk: the arrival of even a small number of Haitian immigrants, even if the immigrants had boosted the local economy. The Haitians were seen as sites of deep anxieties of disruptions to normality, as dangers to personal safety, and as disrupting the all American family by the sacrifice of its pet–the friendliest family dog or cat–

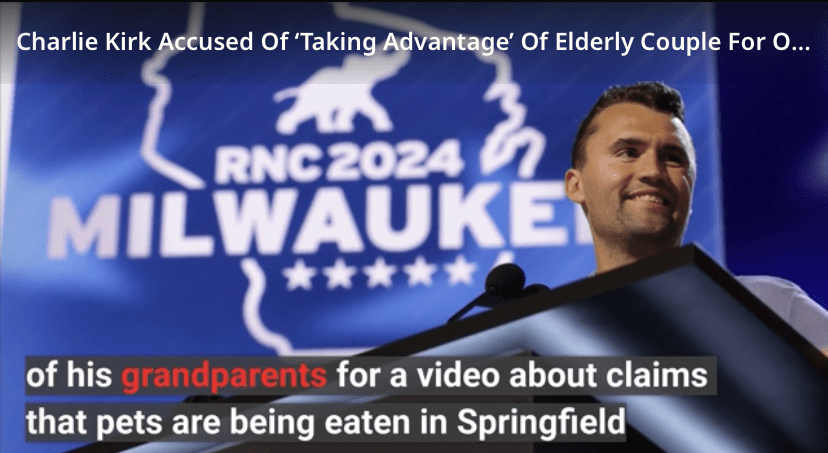

–taken as an icon of American identity. For Trump wanted to cast them, not tacitly but explicitly, as proof of a “great replacement” of whites that that did not need to be located in a state–Springfield might be in Missouri, Florida, Massachusetts, Kentucky, Illinois, or Ohio, where like-named towns existed–but denoted a replacement of American values that American needed to be paid attention to. And given the almost generic image of a Middle American society at risk. To be sure, social media provided a willing megaphone to expand these fears, that the Biden-Harris team ignored. The Haitian refugees were conjured as a danger to the nation, a synecdoche for the figure of the migrant in its most un-American form in the only Presidential Debate between Harris and Trump. A set of talking points that emerged from an interview stating that there was no evidence that Haitians had eaten animals–ducks, geese, or dogs–was shamelessly manipulated in the coming weeks by Charlie Kirk, the head of Turning Point who has never shown much respect for the truth in making vitriolic points, as if it was all the proof he needed to confirm a vicious internet meme.

The Speaker at the Republican National Convention Who Eagerly Spread False Rumors of Dog Eating Haitian Immigrants

But if the talking points became central to energize audiences at the Presidential Debate, they gained a life of their own on social media that seemed to erase any question of reality, as the image of disappearance of ducks, geese, and dogs had quickly conjured an enemy from within that boosted calls to enforce the investment of public funds to guard the border. The former President showed little sense of responsibility that would make him merit the Presidency, of course, as he mapped migration by local and not global terms in declarative sentences: “In Springfield, they’re eating the dogs. The people that came in. They’re eating the cats. They’re eating — they’re eating the pets of the people that live there. And this is what’s happening in our country. And it’s a shame . . .”

The generic third person plural was left unidentified, but asked one to map one’s relation to the country–as in “they’ve shot the President” or “they’ve killed the Senator!”–to distribute collective guilt across all migrants, in ways that were, to be sure, readily echoed after Charlie Kirk’s shooting with the blurring of the motives of his assassination as the product of “Democratic left” and “Democratic assassination culture” (John Kass), out to kill the real inspiration to America’s young, “the political left” (Governor Spencer Cox), and “an attack on [President Trump’s] political movement” (Lindsay Graham), or Joe Biden’s attempt to “silence people who spoke the utter truth” (J.D. Vance), and even “the damage that the internet and social media are doing to all of us” (Spencer Cox again, this time on Meet the Press and not a news conference). Yet the drumming up of internet rumors, as much as Kirk’s genius in organizing outreach to younger voters, was the basis of the sordid stock racist accusations of immigrants eating dogs. “They” did not need to be identified; “they” were the people we needed to keep out of the country.

The fears of the “open borders” policy that the Biden-Harris team had willfully persisted was cutting short America, as the Republican congressmen on the Judiciary Committee investigating the injust policy hadgenerated on what seemed official masthead, a waste of official papers to distract American voters–

–in a waste of official congressional paper, to make the meme material in the national news media and the consciousness of Americans who worried about those “leaky borders” as being a threat to American society. And now, it had gotten so bad that even the dogs would suffer.

Not only Charlie Kirk ran with this, but the entire right wing media system seems to have kicked in as the story materialized. The insinuation profited from how the “pet dogs”–even if they did not exist, or were not eaten as per rumor–had become red meat as clickbait within the Turning Point media empire and social media of the Alt Right. The alternative reality Trump dignified was imported wholesale from social media. Indeed, when the moderator questioned the basis for the statement in a forum for selecting the future President, Trump offered no actual proof but returned to innuendo: “Well, I’ve seen people on television . . . people on television say their dog was eaten by the people that went there,” revealing the wrong of offering migrants asylum as a threat to domestic pets. “Cats are a delicacy in Haiti,” offered the video that Kirk made to give wider currency to rumors of the abduction of pets–as if it were the 2024 version of the international pedophilia ring Hillary Clinton allegedly “ran” out of a pizza joint–and “ducks are disappearing,” as if to map the Springfield as a “tinderbox” of the crisis of immigration, and the 20,000 Haitian migrants who arrived in Springfield over the last four years who have helped to drive the small city’s economic boom became evidence of illegals taking open advantage of the Immigration Parole Program of Joe Biden to sacrifice American pets as if they were cannibals, eating the dogs that became a synecdoche for all Americans–and the American Dream.

Even as Haitians had themselves insisted on the news that “We’re here to work, not to eat cats,” in response to the outlandish accusation, the footage of their protests offers, however circularly, footage that was consumed as evidence of an admission of their alleged guilt. The protests became evidence for the need for a new Immigration Ban, and stoked fears of the Great Replacement. What was red meat for social media clickbait became passed off as truth, in the false currency occasioned by Presidential elections, that have become sanctioned rumor mills since Whitewater if not Watergate, as charges of incompetency materialize in disproportionate commensurability to the weightiness of the office of U.S. President.

The feast of hate male that the MAGA movement has invited has opened up the sluices on social media innuendo, inviting us into the society of spectacle of online memes to launch a bid to defend the nation. Trump’s brusk adoption of the first-person reminded us that he was in charge, and should be, effectively asking viewers of the debate to join him, watching TV in his home. He seemed to call for a need vigilance to supervising the crisis of migration that Vice President Kamala Harris had permitted to threaten the country, papering over a national emergency that the Democratic Party refused to acknowledge as an invasion as he had called-even at the risk of endangering the safety of Springfield’s domestic pets. He’d be watching . . .

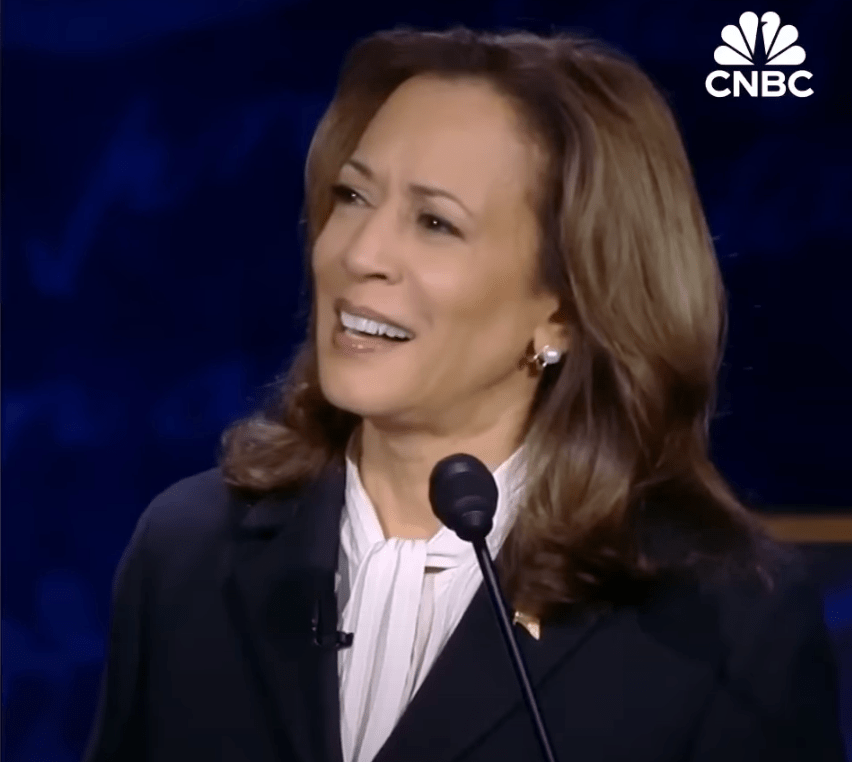

For her part, it was utterly unsurprising Kamala Harris was unable to respond to the outrageous charge with concreteness. Did she fail to connect in any similarly visceral way or was she just unable to reply to the outrageous claim? Trump had outflanked the outrage that his constituency had come to expect. The fictional charge perpetuated myths of aliens endangering Americans’ pets J.D. Vance used to reveal the threat admitting immigrants–even granting asylum–as a threat undermining civil behavior and the American family, but pushed the boundaries of civil norms. There was no sense that the charges aiming to dehumanize the immigrant and to blame her for the endangerment of American pets could be presented on national television as evidence of the danger she would cause the nation: it was all but impossible for her to enter that rabbit hole. Could one even trust Kamala Harris to be a defender of America against these Haitians, her very appearance and hair suggesting that she could not be trusted to protect white Americans from the arrival of migrants who failed to understand American values, and failed to integrate in white America? This proclaimed the reclaiming of tacit racism on steroids by Trump, Kirk, Vance and Stephen Miller.

Presidential Debate in Ohio, September 10, 2024

The outrageous and ungrounded accusation against Haitian immigrants of being cannibals recycled old fears of the beast-like nature of an island colonized by Spain and long used for American enterprise at low wages, was rather tired. After all, it was one of the more striking images of the Governor of the colonial administrator who had served as Governor of New York State, the Irish-born Cadwallader Colden’s colorful description of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, based on his early position as the first colonial representative to the Iroquois nation. His familiarity with the Five Nations of the Confederacy had featured the puzzled anthropological observation that “the young men of these nations feast on dog’s flesh,’ although Colden, in 1747, confessed he was unsure “whether this be, because dog’s flesh is most agreeable to Indian palates, or whether it be as an emblem of fidelity, for which the dog is distinguished by all nations.” Whatever the reason, he admired the indigenous “boast of what they intend to do, and incite others to join, from the glory there is to be obtained: and all who eat of the dog’s flesh, thereby enlist themselves” in a gory potlatch of canine flesh to display their martial bravery. The dog-eating indigenous males revealed their militant character that Colden felt worthy of the virtue, discipline, and honor of Romans, if their modern use of muskets, hatchets, and sharply pointed knives, if abandoning bows and arrows, accompanied fierce adornment of themselves with red war-paint, “in frightful manner, as they always are when they go to war,” rivaling the military discipline and honor of Romans.

Not so for the Haitians Trump painted who arrived across our open borders. The accusation Trump leveled suggested a third reason for the eating of dogs: the Haitians’ absolute inhumanity, which needed to be separated by a wall. It clearly bore fingerprints of his speechwriter Stephen Miller, who had just crested 100.000 views on X after questioning allowing “millions of illegal aliens from failed states” in “small towns across the American Heartland.” Donald Trump could not help himself in echoing Miller’s charge, as he held his ground on the debate stage, summoning a sense of grievance by lamenting as if to himself “What they have done to our country by allowing these millions and millions of people to come into our country . . . to the towns all over the United States. And a lot of towns don’t want to talk — . . . a lot of towns don’t want to talk about it because they’re so embarrassed by it.”

September 19, 2024

Was this not itself an open violation of social norms? It mapped Haitian migrants in the United States, if not openly criminal, as endangering the nation that demanded to be fully revealed. The outrageous charge of “eating the dogs” was not only unfounded, but pushed the nightmarish scenarios of migration, a stock trick of the 2016 election, mapping an invasion migrants allowed under the poor vigilance of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris: an outrageous charge fabricated out of whole cloth dominated post-debate discourse, becoming remarkably effective in social media, resurrecting the worst stereotypes of deep prejudice that subverted any debate on immigration policies by purported evidence no one in the White House was willing to acknowledge. The protection of domestic pets started to seem like it was about the enforcement of border policy. Was this pandering not a sort of primal fear of othering, tracking the approach of a race not like us who didn’t share our basic customs or social codes as they crossed the southwestern border?

Planting the rhetorically powerful fears of dog-eating immigrants as invasive revealed the Haitian as an attack on values that need not be brooked–an attack on American values passing under the radar of the current administration that failed to screen migrants in promoting a CBP One™ Mobile App as an open portal for undocumented migrants to allow migrants provisional I-94 entry, schedule appointments at points of entry, or gain temporary visas–a program he immediately shuttered after his 2025 inauguration. The mobile app reduced illegal immigration grew popular among Haitians, Cubans, Venezuelans, and Mexicans as it streamlined opaque processed of applying for residence, but Trump reviled it as evidence of a policy of open borders, attracting almost a million users for tens of thousands appointments with migration courts. It would abruptly cease functionality in January 2025, cancelling pending appointments migrants made, leaving many without any basis to pursue the hopes some 280,000 had had hopefully logged into daily, as he pledged to use the army to remove 11 million he claimed in the country illegally by mass deportations, and canceled court appointments of some 30,000 migrants made for coming weeks. The need for an “immediate halt to illegal entry” he asserted, began with a need to to restore human agency to define who gets to become an American citizen and ending refugee resettlement.

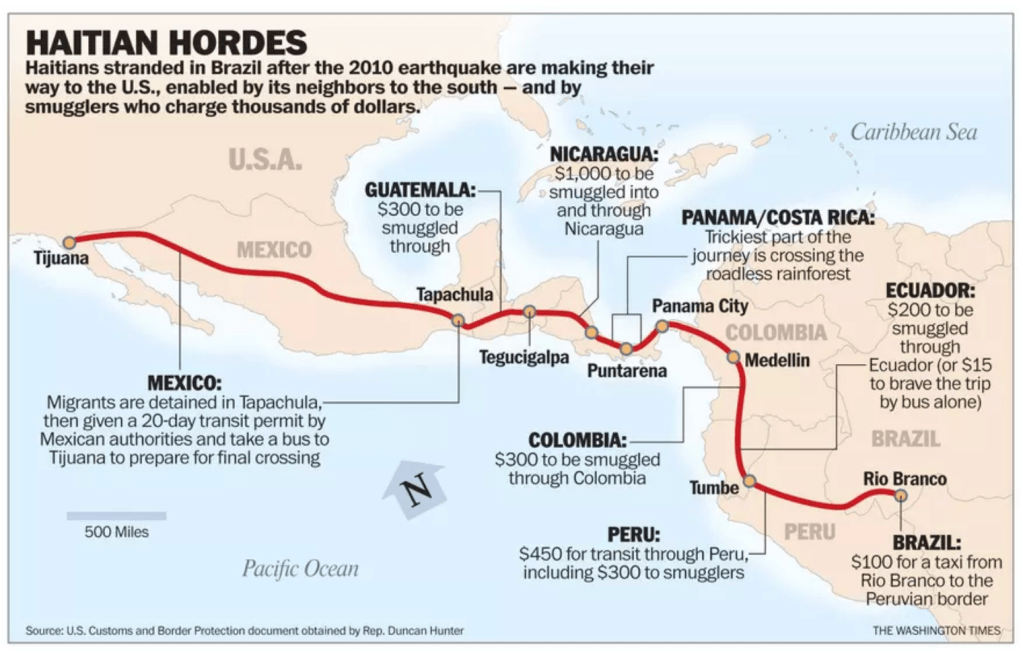

Trump has of course vowed to end illegal and legal entry of migrants, asserting as illegal border crossings had plummeted that the current pathways of migration were not sufficiently controlled. He cast the expedited streamlined avenues of legal migration by Apps as oversteps of Presidential authority, affording provisional entry of undesirables who the Haitians were a recognized token; the MAGA movement outrageously tagged Kamala Harris as having abetted illegal smuggling by an app that allowed nearly a million migrants to enter the United States. The sudden suspension of the app’s functionality be executive order would reduce the reliability, speed, and assistance available to migrants, as if they creating what he called illegal smuggling routes. echoing outdated MAGA maps that accused the Mexican government for enabling the smuggling of “Haitian words” into the United States illegally back in 2016, a map that probably lay at the back of his mind as he cast aspersions on the smuggling of Haitians into America that the CBP One™ mobile app allowed.

“Mexican Officials Quietly Helping Thousands of Haitian Make their Way to the United States Illegally,” Washington Times, October 10, 2016

“Hatian Hordes” did not emerge as a meme in the 2016 election, but it may have lay hidden at the back of Trump’s capacious mind. Did this outdated map of “Haitian Hordes” of the alt right Washington Times not rolled out as fodder in advance of his own earlier campaign for President, eight years ago, underly the logic of his new rather extravagant claim about “eating the dogs,” made without any grounds at all? Candidate Donal d Trump had repeatedly promised audiences of rallies he intended to “end asylum” most Americans did not want or desire, as if the Biden-Harris had enabled an unprecedented national invasion. The figure of the Haitian demanded to be contextualized in the escalating illegal immigration that Biden and Harris had abetted. At his rallies, he had promised the liberation of the nation he would bring about by “return[ing] Kamala’s illegal migrants to their homes,” explaining his intent to replace immigration with “remigration,” or forced rendition, vowing in rallies and social media to “save our cities and towns in [the swing states of] Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and all across America!” Perversely, he would do so by ending an app the app directs each type of user to the appropriate services based on their specific needs. indeed, “the United States lacks the ability to absorb large numbers of migrants, and in particular, refugees, into its communities in a manner that does not compromise the availability of resources for Americans,” read the Executive Order he signed upon inauguration in 2025, cutting off access to jobs in America or migrants fleeing persecution, or even American allies from Afghanistan, as if drawing up a drawbridge that had long existed on the grounds that the nation was “full up.”

August 20, 2024/Trump Rally in Howell, Michigan/Nic Antaya

The charge of dog-eating Haitians elevated the gutter of the internet to Presidential debates, as an exemplification of the false statistics displayed at rallies in order to make his point to the nation. The salacious accusation picked up off of social media was presented as if objectively true, elevated from social media to the forum of a Presidential debate as a basis to chose the next President. Trump recycled a hurtful and demeaning meme as if it were a charge, and evidence of the clear need to restrict and stop migration outright–and discontinue granting asylum to refugees, legal or illegal. The charge elided the right to asylum, or the persecution that immigrants faced–or, indeed, the dependence it would throw migrants into on smugglers. For by revealing the true identity of foreign-born immigrants as dangerous outsiders, ready to consume domestic pets, Trump tagged the Haitians as threats to the nation by mapping their foreign origins, introducing a logic of mapping the threats by their nation of origin as needing to be expelled from the social body to make it healthy again–and in suggesting the need of a strongman able and ready to confront the eaters of dogs to expel the migrants for breaking the deepest social bonds of American society.

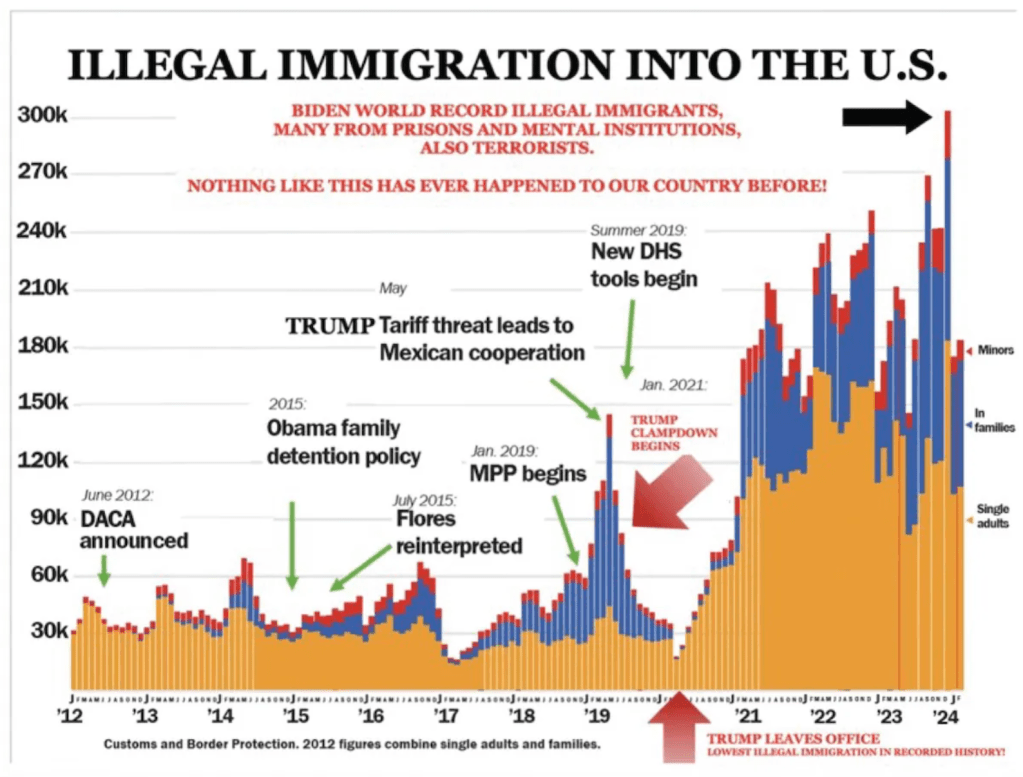

Indeed, the rhetorical image of migrants suggested an image of rounding up stray migrants, posing a danger to naturally born Americans, and the limits to which the Biden-Harris migration policies had pushed the nation to the bursting point–a powerful narrative if one hardly grounded in fact. The charge was but the latest dog whistle designed to stir up anti-immigrant fear resurrected old tropes not only of casting Haiti as the target of fear as a rare outpost of the European colonies where slavery was outlawed, where black majority rule stood to upset racial hierarchies and upset a civilized order. Fears of an imbalance in racial hierarchies fed unwarranted fears of immigrants fleeing repression as a known vector of infectious disease. Trump had long attacked a “Phone App for Smuggling Migrants” as a way to facilitate illegal immigration that Harris and Biden created for the sole purpose of “smuggling” migrants into the United States–an app Trump vowed to terminate, and did as soon as he entered the Oval Office. He blamed Harris for allowing migrants to access App dating from his Presidency, available from Google play stores and Apple since 2020, that he identified with Harris–maliciously vowing to “terminate the Kamala phone app for smuggling illegals (CBP One App), revoke deportation immunity, suspend refugee resettlement, and return Kamala’s illegal migrants to their home countries”–as if the presence of migrants eating pet dogs was due to Harris’ negligence in outsourcing human intelligence, rather than an effort to increase border security. The “big reveal” during the debates revealed the inner nature of the migrant as a threat, undetected by an app, and demanding human intelligence and vigilance he could provide, promising to end the spike of an alleged “Biden world record illegal immigrants, many from prisons and mental institutions, also terrorists”–as undesirable as the dog-eating Haitians seem to be.

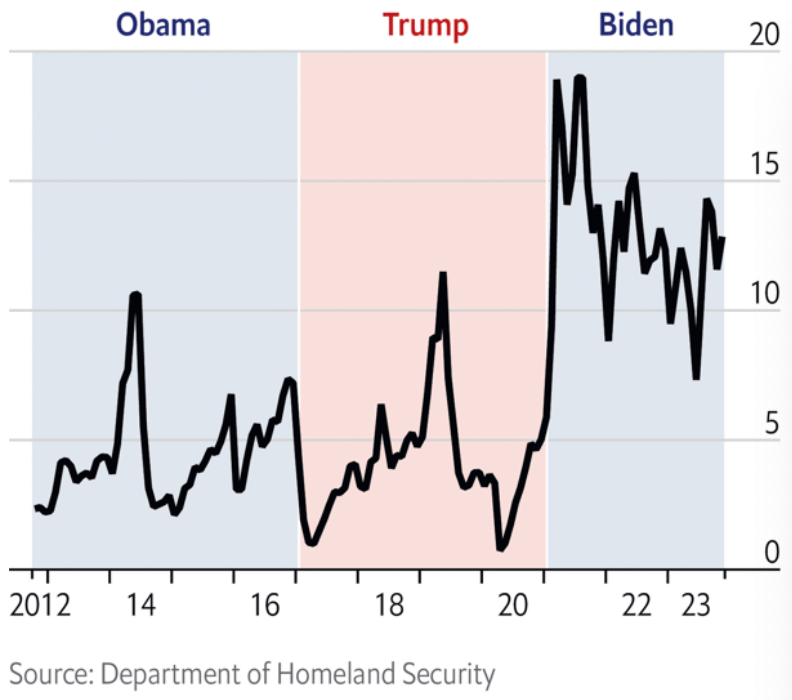

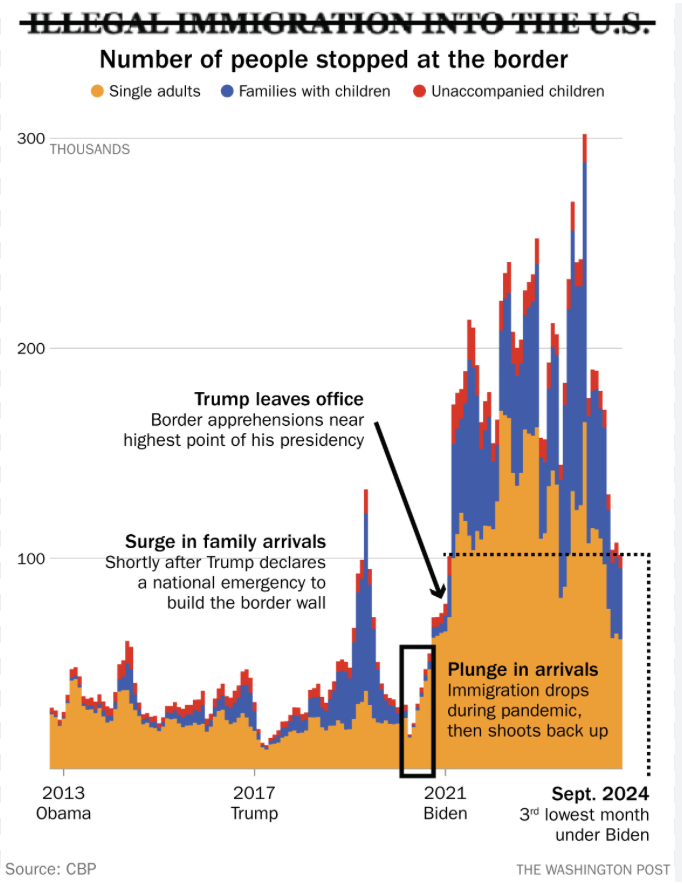

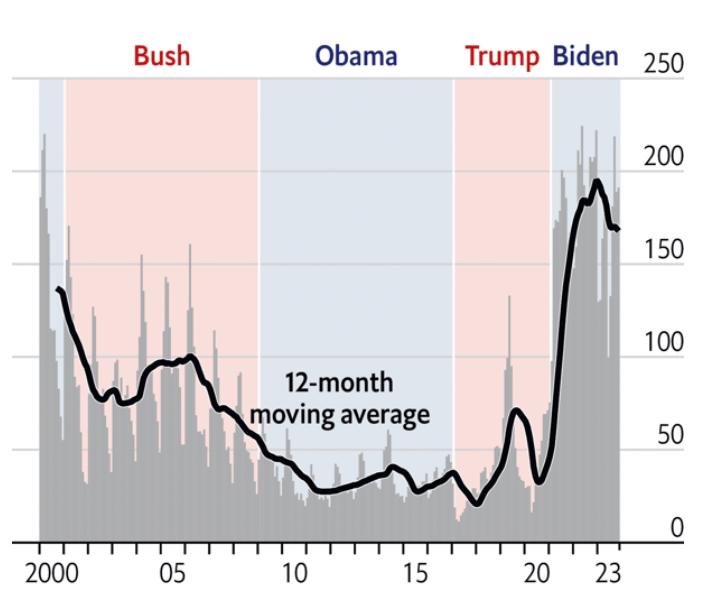

The vignette was a theatrical reminder of the need to “immediately end the migrant invasion of America,” blurring the need to “stop migrant flights, end all illegal entries, [and] terminate the Kamala phone app for smuggling illegals as if they were all contributing to an invasion we allowed–although the misleading chart he was so fond of displaying that suggested an emergency indicated not “illegal immigration” at all, but Border Patrol statistics on those stopped at the border, not admitted, and the drop in immigration arrivals of the pandemic shot up in his Presidency, readers of the Washington Post, before it became an organ of government, were reminded over a month after Trump presented the meme domestic pets had been injured by immigrants who crossed the border.

The misleading charts later touted as the “chart that saved Trump’s life” not because of its inaccuracies, but that had grabbed his attention for a moment as he looked toward it in the rally of July 14, 2024, moving his head to the chart that became the basis to boost his political fortunes, he dodged an assassin’s bullet. But for all its abundance of stubby red arrows and acronyms, was a story that he was massaging all along:

Washington Post/October 24, 2024

The statistics he presented of the escalation of illegal migration into the county. The insinuation animal-like people had attacked the pets of American families appeared grounds to impose discriminatory immigration policies that would abandon longstanding principles of granting asylum.

The baseless charge pushed us back in time, stoking fears of globalization opened the nations to attacks on white American families that dated from the first age of globalization. While presented as the latest evidence of the wiles of these immigrants Biden and Harris allowed to enter our borders by their Border App, it seemed evidence of their readiness to sacrifice the safety of the nation to a dog-eat-dog world that existed outside the safety of American borders, rather than expedite the complicated process of cross-border migration. If the partnership of man and dog has been long a sturdy basis for cooperation, and indeed a paradigm for human companionship, if not of parallel evolution, the immigrants were upsetting of categorical distinctions fundamental to the nation by treating pets as meat. This was not only evidence of their alleged desperate hunger, but an insidious attack on the stability of the social order–upsetting of naturalized hierarchies of man and animal feared since first contact with the New World and the naming of Hispaniola in 1492.

What was presented as the big “reveal” at the debates of the failure of the Harris-Biden team to look at the evidence before his own eyes was grounded in stereotype, it recycled fears dog-headed men inhabited New World islands on the edges of the inhabited world–among other monstrous races–in the first printed book to recycle attention-grabbing images in the encyclopedic images used in 1493 Liber chronicarum known as the “Nuremberg Chronicle”–a historic achievement of the early press–their wagging tongues colored red in deluxe editions to suggest their inarticulacy–

–where the corrupted tongues of the inhabitants of New World islands were imagined as a focus of concern, lacking rational speech.

Dog-Headed Man, or Cynocephali, from Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

There was almost the sense in Trump’s odd declaration in response to question about immigration to the United States that he expected us to believe at least some of those twenty-thousand might actually have, even if legal immigrants, crossed a threshold of civil behavior and violated one of the greatest taboos in the lands the AI image in the header to this post tries to conjure. “They’re eating the dogs” launched the most recent addition to the laundry list of the hidden cost Americans pay for a poorly policed border–but it raised the bar beyond criminality; dealing drugs; belonging to gangs; taking jobs; and taking housing. When I canvassed for Kamala Harris in Nevada, it was memorable that a friendly man on whose door I knocked in Carson City smiled as he lifted his cute kitty before me, assuring me at once that he would soon be voting Democratic and loved his pet– “[’cause] I don’t eat dogs; I don’t eat cats.”

In the month and a half since Trump delivered the unfounded accusation on national television it had percolated within the political discourse, taking shape as a hateful accusation and a venting of anti-immigrant sentiment. The confession was a joke, more than a confession, but an admission of the power of the Trump-Vance trope that extended to a theatrical appropriation of citizenship by a prospective voter, jokingly confessing to me the absurdity of the situation where migrants were so thoroughly demonized in ways that even if I weren’t the son of a psychoanalyst would make me think of Sigmund Freud’s reminder that jokes are deeply related to the unconscious–and even the collective unconscious that Trump had so successfully tapped–that reservoir of rhetorical figures of “women, fire, and dangerous beasts” that led Freud to ponder in 19054 how “only a small number of thinkers can be named [in western philosophy] who have entered at all deeply into the problems of jokes,” plumbed the relations of the comic to caricature, rooted in the comic nature of the verbal contrast between apparently arbitrary connections or links seem to discover a sense of truth in its verbal economy–a compression of meaning that creates a new statement, where the allusion to the monstrous may be a stimulus to revealing the nonsensical nature of the statement, as if it imagined the half-human people on the worlds’ edges imagined in 1493, as the first news of the New World filtered back to Germany, by the printing house in Nuremberg, blurring fact and fancy be medalling visually inventive if vertiginous half-truths.

The widely performed song adopted as a call and response by touring bands in clubs, audiences recite a chorus of dog sounds and cat purrs to personify the purported victims of Haitian migrants. If Freud reminded us that jokes rely on operations of condensation and displacement to subvert judgements by releasing what we might repress, Trump seemed to tap a long repressed collective unconscious of New World cannibals that cast migrants as non-humans, as much as not living legally in the land, drawing lines of exclusion to affirm the rights of nativism long repressed to assert them on the debate stage about the carnage faced by domestic pets–as it became a central point on which to determine who would occupy the White House.

This is not only interrupting consensus on immigration statistics, but elevating internet rumors to the stage of political debate of a Presidential election that is comic enough as displacement of speech acts. Eating pets powerfully indexed otherness and terrifyingly tagged a threat to domestic tranquility; in a nation where pets are in fact among perhaps the best-fed and most-protected of its inhabitants, the threat to domesticated animals violating a salient border of civil behavior, marking a moment of catharsis for its patent absurdity but evoking a long repressed image of the other. Harris had to laugh when Trump stressed “they’re eating the PETS of the people who live there” as if a refrain of moral outrage: the White House had just taken their eyes, the hidden message ran, at what is happening in small towns “across America”–and the state of affairs confronted by the people of Springfield or Aurora: “they don’t even want to talk about it,” because “it is so bad.”

The debate, widely promote4d as determining the next executive to lead the nation, may have allowed him to ask viewers who voters in America wanted to put into the White House, and who would have their best interests in mind–not only global warming, revealing a hidden “real threat” that immigrants posed in ways that Biden and Harris blithely overlooked from Washington, DC.

This wasn’t “news,” but demanded to be included among the issues confronted on the debate stage. For Trump specializes in escalating his oratory to stentorian tones, in explaining political elites had neglected that “they’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the pets, of the people that live there,” weighting each syllable as Harris reflexively laughed, and tried to preserve composure while wondering what she might say to reassure Americans as he uncorked a disclosure of the violence on unleashed on American soil. “This is what is happening in our country, . . . and it’s a shame,” Trump gravely intoned, masking his reach into the dark gutters of the internet with gravitas. Harris barely processed the outrageous claim clothed in faux seriousness as a peril. Harris clearly never expected to hear a displacement so extreme on the debate stage before a national audience, or an issue that the nation was taking seriously in a debate on their visions for the nation’s future. The red flag that was raised alleging that immigrants with government “protection” were engaged in eating pets gained national attention, as it coursed through the internet in ways that amplified a rumor to a story, gaining a faux credibility among anxious Americans, so that Springfield was forced to close its public schools and offices during the presidential campaign, after attracting numerous bomb threats from vigilantes interested in protecting American values that were allegedly under attack.

U.S. Presidential Debate, September 10, 2024

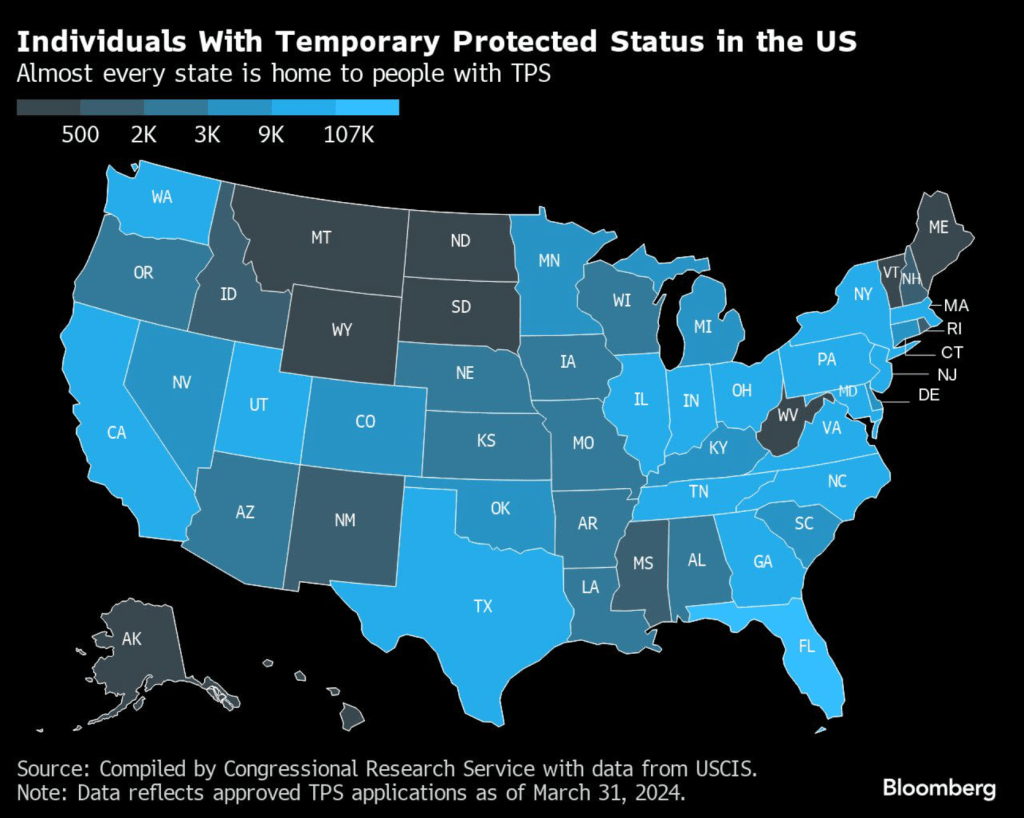

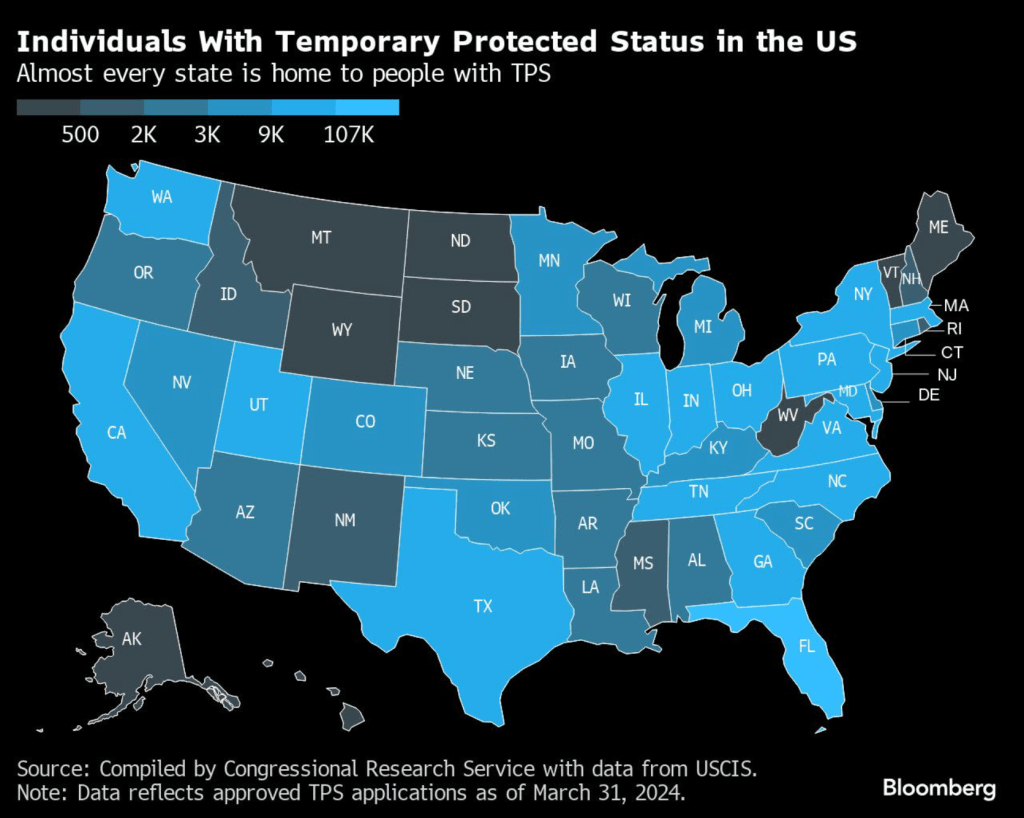

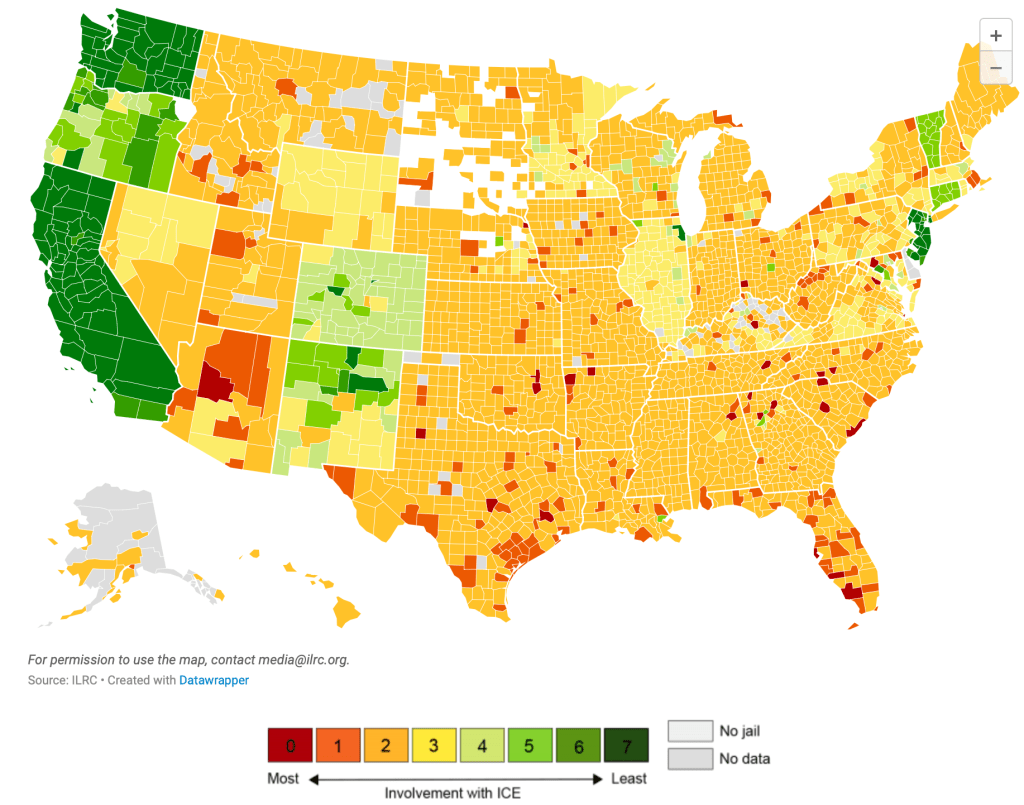

The question was rooted in anxieties that were not rooted in Springfield, or limited to Haitians, but the demographic proved a particularly scary straw man: the charge that an influx of below 135,000 Haitian immigrants Social services and the local health care system in a county of about 15,000 people was magnified in ways that reached the nation. Springfield’s public health officials have struggled to cope with the influx of an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Haitian migrants during the past three years, but the rage was directed to the fact that the US government was offering “Temporary Protected Status” to those fleeing violence and widespread poverty, a humanitarian action that Trump wanted to demonize, long before shuttering USAID: the idea that Americans might help others flee tough circumstances they didn’t deserve was identified as an example of international largesse that the United States couldn’t, in a global economy, afford to continue, as it had encouraged the destabilization of local communities and redirected assistance not to Americans, but to foreigners. And the Temporary Protected Status program had been filling many jobs across the country, but was a subject that was able to come in for a lot of wrath, as s displacement of the focus of government from Americans–even if maintaining a good relation to local states and populations was definitely in national interests. The presence of persons benefitting from Temporary Protected Status whose protections Trump had boasted he would immediately revoke were distributed across much of America, in fact–

–and the notion that these protections were granted seemed a great way for Trump to bring back the sort of cooperations of local law enforcement with federal immigration authorities that were a priority of his first presidency, and which, while Biden had attempted to roll them back, had split the country by 2019, when Biden was elected, as many counties had begun the very sort of close involvement with ICE that Trump was about to promise to restore.

The huge incommensurability between the safety of pets and migrants fleeing persecution was so great it was truly comic in its slippage, as Trump seemed to be spinning facts in ways that seemed to be about borders, but was doing so by peddling utterly unsubstantiated fears. If Harris was trying to process how seriously this fabricated claim might be taken by the viewing audience, amazed that there would be many ready to fall for the bait, and ignore the debate, the direction of which seemed like it might be in danger of suddenly slipping away, as easily as Trump had seemed to recover from the questions she raised about the size of his rallies by attacking her for fabricating the rallies she had held for the previous days. But the issue of a debate about elections seemed less important than the identitarian fears of endangered pets that Trump seemed to be saying had been neglected by the Biden administration.

Fears of dog-eating immigrants were outlandish. They echoed the fearsome nature of the unknown featured prominently in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle as an image of otherness outside the inhabited world–the dog-headed people who gestured, lacking recognizable human speech, were placed at the edges of the known world, talismans of the fake news about “barbarous” peoples and “marvelous races” that early modern readers might expect to define a threshold of the known.

Cynocephalus in Nuremberg Chronicle (Buch Der Chroniken und Geschichten,Blat XII), 1493

The woodcut of dog-headed exotics placed prominently on the edges of the known world circa 1493 in Buch Der Croniken und Geschichten to grab readers attention in the compendium of texts purporting to synthesize all known history, by situating many woodcuts to encourage reading its derivative text. While this motif can be seen as a classic–if not primal–dehumanizing of foreign peoples–the implicit question it raised in the early modern era was whether these dog-headed men possess souls. At a time when Europe was understood to lie on the boundary of an expansive ocean and bounded more clearly, revealed in the edges of early global map featured in the popular book–

Nuremberg Chronicle, detail of world map at Blatt XIIv-XIII Munich State Library, Staatsbliliothek

–the dog-headed men that lay among the fantastic races that ring the global planisphere of Ptolemaic derivation were inhabitants of the edges of the known world described not by Ptolemy, but Pliny Augustine, and Isidore of Seville, and Pliny, authorities one was loath to contradict, whose assertions demanded to be reconciled with the new maps that increasingly included New Worlds. The men who seemed to gesticulate with animation spoke no recognizable tongue, and may have been of some sort of diabolical creation, even if they seem to us early modern cartoons.

Nuremberg Chronicle, Blatt XII, Munich State Library/Staatsbliothek

Are not the dog-eating immigrants not their most recent iteration, people who don’t have respect for pets, fail the affection and citizenship test in one go,–and maybe even lack souls? They surely were imputed to lack patriotism and be un-American, putting aside for now the question of souls– even though the legal migrants in Springfield do not eat dogs. They were terrified at the charge that they did, as the Haitians of Springfield must have wondered what a weird, tortured, social media world they had moved to, where they might be accused of stealing their neighbor’s pets.

Yet these hoary old recycled images of dog-headed men, whose long, loose tongues seemed to compensate, if one notices their animated gestures, for their inarticulateness, emblematized babble in an early book of global history cobbled together from sources of dubious authority and biblical paraphrases. The synthesis of world history was in fact akin to a sort of early modern internet, recycling images and legends circulating in flysheets and leaflets in visually entertaining ways helped readers navigate derivative text that purported to summarize global history. At the same time the edges of Europe were defined, dog-headed Cynocephali were located at the edges of the known world as it was being remapped in real time, situating an upsetting of the divine order of creation that were echoed in fears of dog-eating immigrants who had the edges of the nation.

The eating of dogs has, incidentally, only been legally forbidden in the United States, with the exception of Native American religious ceremonies, and in New York specifically illegal to “slaughter or butcher domesticated dog” for human or animal consumption, suggesting how our legislators take the matter quite seriously–and even if the majority of dogs globally are free-roaming or stray (70% per one estimate at PetPedia, the existence of “dog meat markets” in Viet Nam, the Philippines, China, Indonesia, and Cambodia suggests a blindspot for animal suffering–South Korea will ban meat markets from 2027. The consumption and slaughter of dogs and cats for human consumption was part of the reconciled version of the Farm Bill the Trump White House helped pass in 2018, featuring the “Dog and Cat Meat Prohibition Act,” signed into law by President Trump. The ban on eating dogs was an achievement of the Trump Era, holding there was no place in America for the eating of dogs or cats–both animals “meant for companionship and recreation” and imposed penalties for “slaughtering these beloved animals for food” of up to $5,000. (While China tolerated such meat markets, its sponsor held, “should be outlawed completely, given how beloved these animals are for most Americans” on American territory.)

A part of Making American Great Again was criminalizing killing of dogs and cats, save for religious practices of indigenous,, by imposing federal penalties for slaughtering cat or dog meat for consumption, not protecting animal welfare. While there is no clear coherence for the alliance of the Animal Hope and Wellness Foundation, the nonprofit that promoted the bill’s passage in Congress, dedicated to protecting dogs and cats from being butchered abroad for customer markets in China and Viet Nam, as a step in “making America a leader in putting an end to this brutal practice worldwide,” seeking “to move towards bringing an end to the suffering of these animals who are like our children, our family,” identified two species sought to be banned from foreign meat markets was always a local exercise in response to global problems. The refugees escaping a human rights crisis in the hemisphere would perhaps be both a proxy and symbolic surrogate to the crisis of “illegal” migrants moving across the southwestern border.

The number of Haitian immigrants to the United States had for some precipitously risen–doubling since 2000–as immigration became a hot-button issue, and seems on track to grow tenfold since 1980, creating an irregular influx in response to economic crises, natural disasters as the 2010 earthquake, rising gang violence following the assassination of the Haitian President Jovenal Moïse in 2021, that make Haitians an ever larger immigrant community–and given the threefold increase in immigration since 1990, the community is easily othered, perhaps explaining their targeting by outrageous conspiracy theories about eating pets.

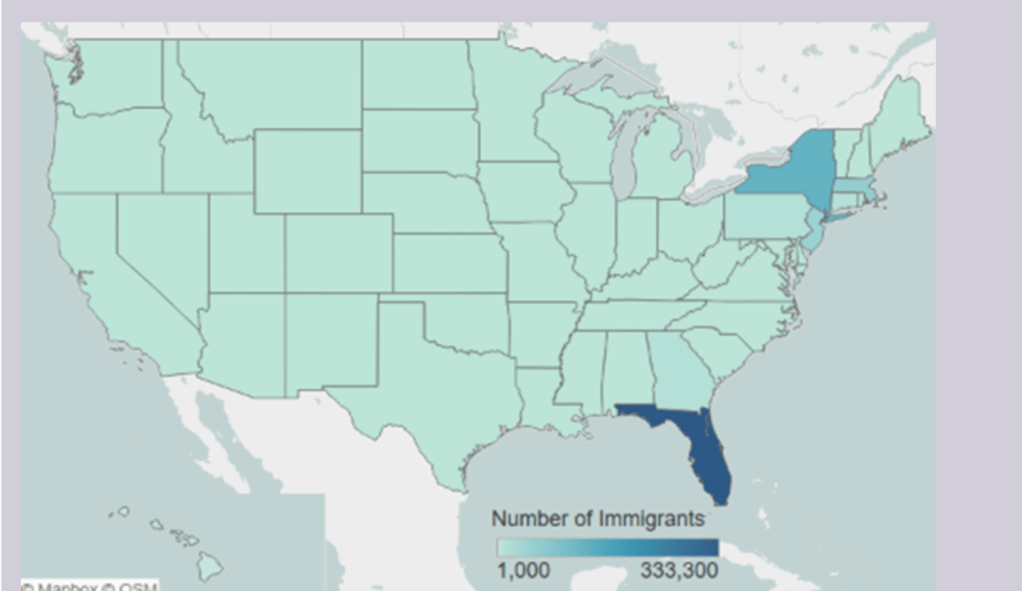

Most of these immigrants are clustered in Florida, with over 500,000 in that state, more than New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts–placing the 10-20,000 in Springfield at the edge of future immigrant wave of immigration fears, based on pre-pandemic destinations in the United States cities, 2017-2021–

Presence of Haitian Immigrants in the Unit4ed States, 2017-2021/MIgration Policy Institute

If America is the dominant destination of Haitian immigrants in the hemisphere, Haitian immigrants to the United States–about two thirds of foreign-born Haitians –68.7%–are naturalized, but current circuitous routes of immigration from the island are indeed through other regions of the hemisphere, creating a global optic for their arrival in the United States fora non-partisan group promoting the integration of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Most are easily cast as “global refugees,” in other words, and symptoms of a problem of the refugee within American shores, following paths that Donal Trump wants to show television audiences he intends to be in control, and prevent from arriving in the United States.

.

To be sure, eating of dog meat was, since 2018, a federal offense able to be punished with fines up to $5,000–even if eating dogs if rare was legal in forty-four states. The conjuring of the inhabitants outside the known world were specters, akin to dangers Trump conjured arriving from beyond America’s borders, by intimating how “the people that came in, they’re eating cats.” The dogs Haitian immigrants were claimed to have stolen from Ohio residences are hardly entertaining. In fact, they were rather spectral images ramping up the incendiary charges blamed on immigrants. From one police report filed in Springfield, the image of refugees from a dog-eat-dog world of open violence bringing a collapse of social values to Ohio, the American heartland, stuck in audiences’ minds. For in spreading social media memes of actually inexistent and unfounded assertions grounded in vitriol he was elaborating a mythic fear, as much as basing alleged local abductions, telling Americans that “Reports now show that people have had their pets abducted and eaten by people who shouldn’t be in this country.” Deriving from a single since-debunked police report of stolen pets, the vitriol launched against Haitian immigrants to Springfield was an instance of trying to trigger reactions to the recent presence of immigrants in the Midwestern city that Trump suggested were increasingly replacing local residents–and were, as “others,” tantamount to illegal residents, even if they were granted legal entry for humanitarian reasons.

The absurd charge helped reintroduced fears of immigrants into the national political discourse. The specters of eating dogs may have been false, but fed a demand to Make America Great Again by primal images of othering best captured in AI images. It was the latest in the incendiary charges Donald Trump raised about drug-dealing, gang-breeding, methamphetamine-smuggling, job-taking, un-American “illegals” about whom Trump had tried to spook the nation–maybe akin to how Hernán Cortés had described in a letter about his arrival in Tenochtitlan in 1519, soon before the historical city was captured by the Spanish, how its resident had bred dogs for eating–an image that seems to be confirmed by archeological evidence, more than as pets with whom to settle it. But the This buried echo of Great Replacement Theory rhetoric of an “invasion”–they “came in, they’re eating cats”–may have been a reminder that dogs were indeed brought to Haiti to discipline its indigenous inhabitants back in 1493 by Christopher Columbus when he returned to Haiti, if not that dogs had become part of the American family. The domesticization of canines in Europe dates 12,000-13,000 years, and dogs were eagerly conscripted to return for the transatlantic voyage to establish control over New World islands,–including Haiti.

But the American dogs rumored to be devoured by immigrants, unlike the unruly mythical beings with canid heads said to live in Africa or India, escalate attacks on the disruption of domestic peace. There are compelling reasons to map this anti-immigrant vitriol as the latest mutation of the Great Replacement Theory. The ungrounded rumor of dog-eating Haitians suggests how the unknown have somehow entered the known, and even if the geography was unspecified and unapparent, the claims that on their face are ludicrous: “In Springfield, they’re eating the dogs . . . they’re eating the pets of people that live there, and this is what’s happening in our country, and it’s a shame“–as if those “eating the pets of people that live there” didn’t legally live there. And these were “our dogs,” household members who were at increased risk not only of being killed, but even barbarously eaten. As much as Trump’s acid accusations has been mocked in memes on media like YouTube, Spotify and TikTok, his voice sampled, remixed and embedded in songs that sent it streaming far beyond immigration policy–the topic to which the former President was responding–a viral frenzy inspiring viral dance trends repurposed aims to rekindle fears of undocumented immigration to blunt their actual harm.

Conjuring images of eaters of dogs was the latest materialization of existential fears of invasion, and border-crossing, as the arrival of a threat allowed into the nation. A Springfield Republican explained that the same foreign residents were actually replacing the city’s population, as much as endangering its pets: “I’ve seen them, . . . They’ve replaced the population in Springfield, Ohio,” as if the bucolically designation of an American town was actually being desecrated by a demographic shifts allowed by the toleration of cross-border immigration. If multiple canines were in fact brought by Columbus to the “New” World–and to Haiti, whose indigenous residents they cruelly disciplined–in 1493, the sense of mastiffs and greyhounds as companions in his return to the Americas, used as attack dogs to discipline indigenous inhabitants,–if a local dog is painted among indigenous inhabitants, in the painting of the Landing of Columbus installed in the Capitol Rotunda, in 1847 and painted by John Vanderlyn, that portrayed Columbus’ triumphant landfall on Guanahani, as he claimed it for Apanish monarchs by raising the banner of Castile on San Salvador.

John Vanderlyn, Landing of Columbus (1846)

The painting was commissioned by the U.S. Congress in 1836, at the same time as indigenous lands were being seized by the federal government, featured Columbus looking heavenward pointing a sword to the ground, as a friar holds a cross, while unclothed indigenous hiding behind a tree watch the arrival of armed soldiers, beside a dog, as sailors who eagerly search for plentiful gold in its sands. Europeans brought a new variety of dogs as a sign of their arrival, having domesticated dogs far earlier, and developing over 20,000 years inter-species affection and communication and affection.

Domesticated dogs were later naturalized as part of the home in postwar American prosperity of wealth and back yards. Living in green suburbs, household dogs marked a well-being and prosperity by the dogs now cast as threatened by immigrants–if in 2016, an astounding 48% of American households had a dog, just under half–the canine idyll of domestic bliss that is currently supported by a booming pet industry resilient despite inflation or economic recession was being threatened.

“Fido and the Fairbanks Family” (1964), Eliott Erwitt/Magnum

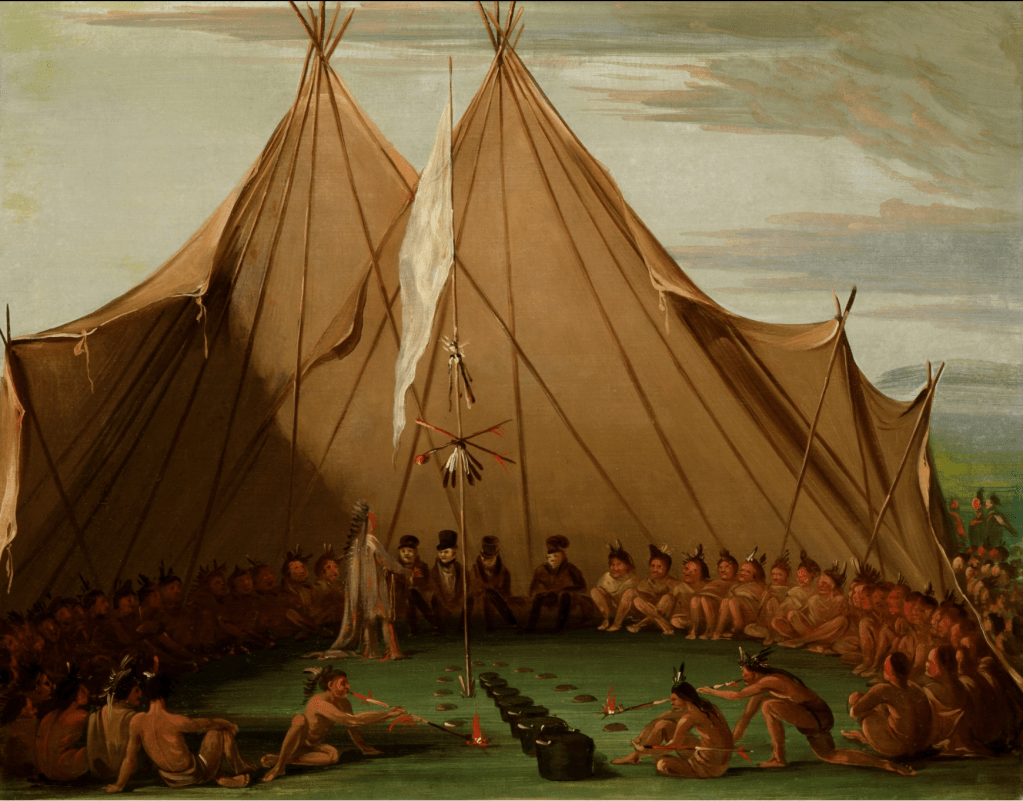

The dangers posed by potential illegal aliens who were purportedly attacking America pets in the midwest out of hunger or for satanic rituals was a “fake map”–a map worthy of the legends of dog-headed births and two-headed dogs of the Nuremberg Chronicle–not anything close to an actual map based on accurate data. There was a sense of the fears of dog-eating that existed, perhaps, at America’s mythic borders–the dog meat painter George Catlin was invited to joined was “the most undoubted evidence they could give of their friendship”–explaining the ceremonial significance y apparent in the “knowing the spirit in which it was given, we could not but treat respectfully” as he travelled through Indian Country as an early ethnographer, in hopes to negotiate treaties after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, as an emissary of the Department of War. He explained “the Indian sees fit to sacrifice his faithful companion to bear testimony to the sacredness of his own vows of friendship” in the ceremony he depicted c. 1832 as a sign of the frontier, he visited among the thirty-five tribes he visited as emissary of federal agents of Indian Affairs–

George Catlin, Sioux Dog Feast (1832-1837)

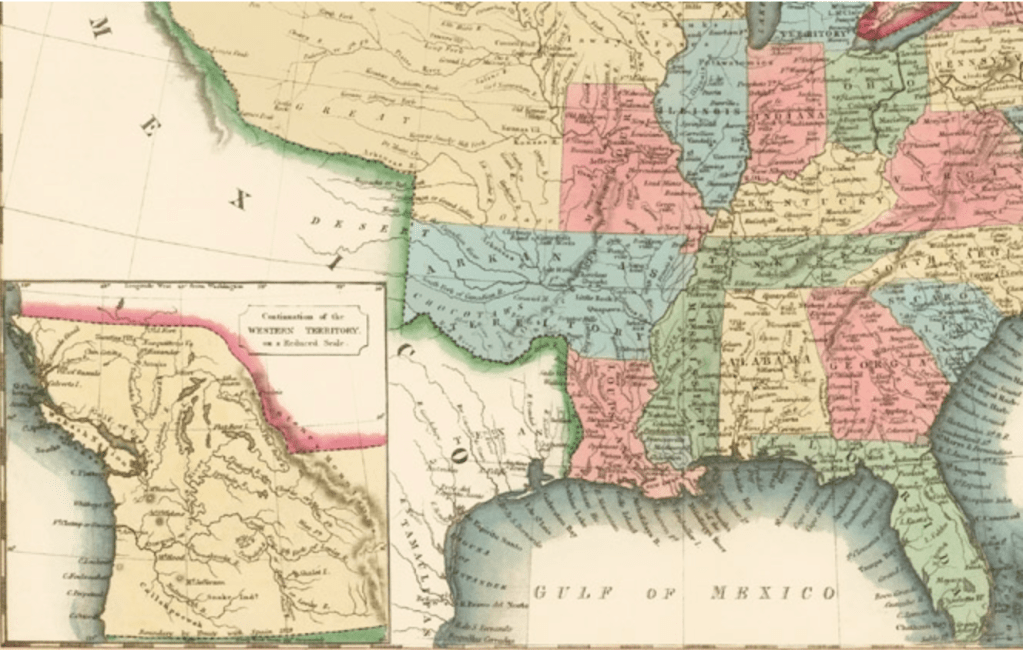

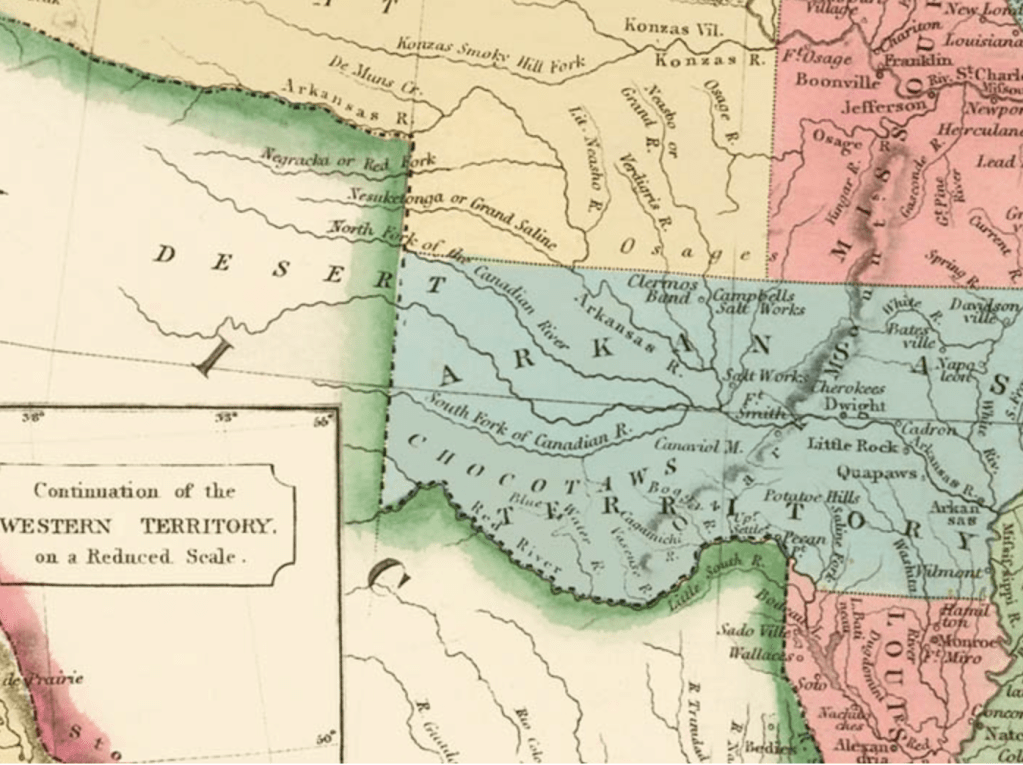

–a meal that suggested the uneasiness of the uptight hatted Americans sitting beside unclothed indigenous, as the western territories of the United States border were contested, before the expanded borders of the Oregon Treaty (1845), the annexation of Texas (1845) and Mexican Land Cession of 1848 redrew the west–

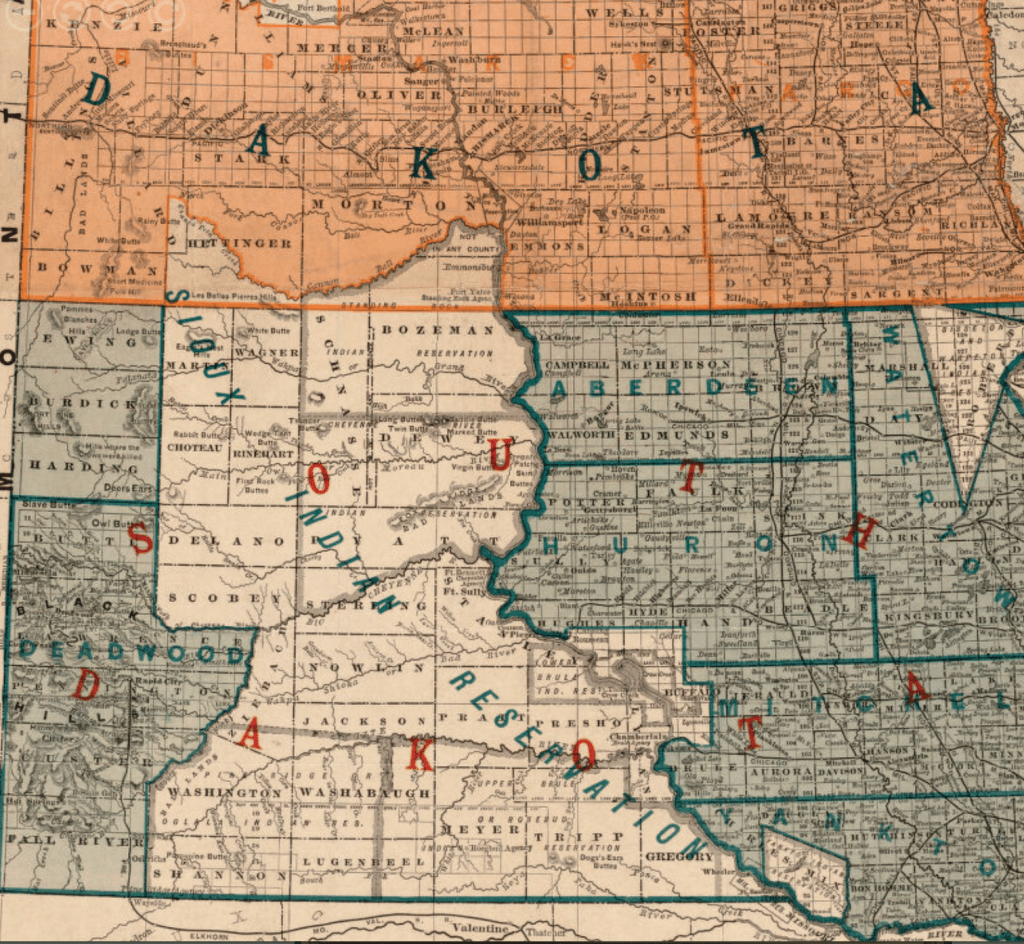

Western Borders and Indigenous Nations, 1832

–before the Sioux were confined in the somewhat sizable reservation between the Dakotas.

Official Map of the Dakotas, Showing the Two General Divisions of Dakota, North and South, the Land Districts, Indian Reservations, Counties, Towns and Railroads (1886)/Leventhal Map Collections, Boston Public Library (detail)

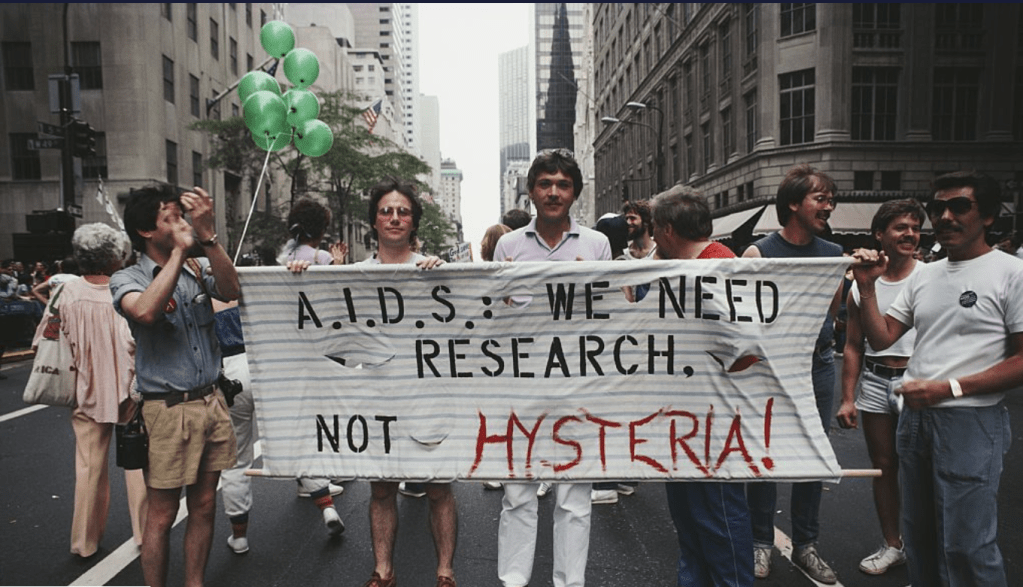

The specter of forceble unwanted canine abductions–an absurd intrusion into civil society illustrating the illegal action of migrants–was a colorful projection of the imagination akin to the indigenous captivity tales. As much as Michael D. Shear of the New York Times may not that “For Haitians in the United States, The Animus of Trump Goes Back Decades,” a “derision” rooted in “unfounded concerns about Haitians and AIDS,” when Haitians were identified among the at risk communities in a real health crisis that faced the United States–the AIDS epidemic–a bit of fake news echoed in recent statements by Trump that the nation still has “a tremendous problem with AIDS,” the strategic singling out of Haitians in Springfield was a desire to shift the electoral map in a swing state responded to the status of Haitians as temporarily protected humanitarian refugees–but the question of Temporary Protected Status was not confined in any way to the midwest, and not, by 2024,

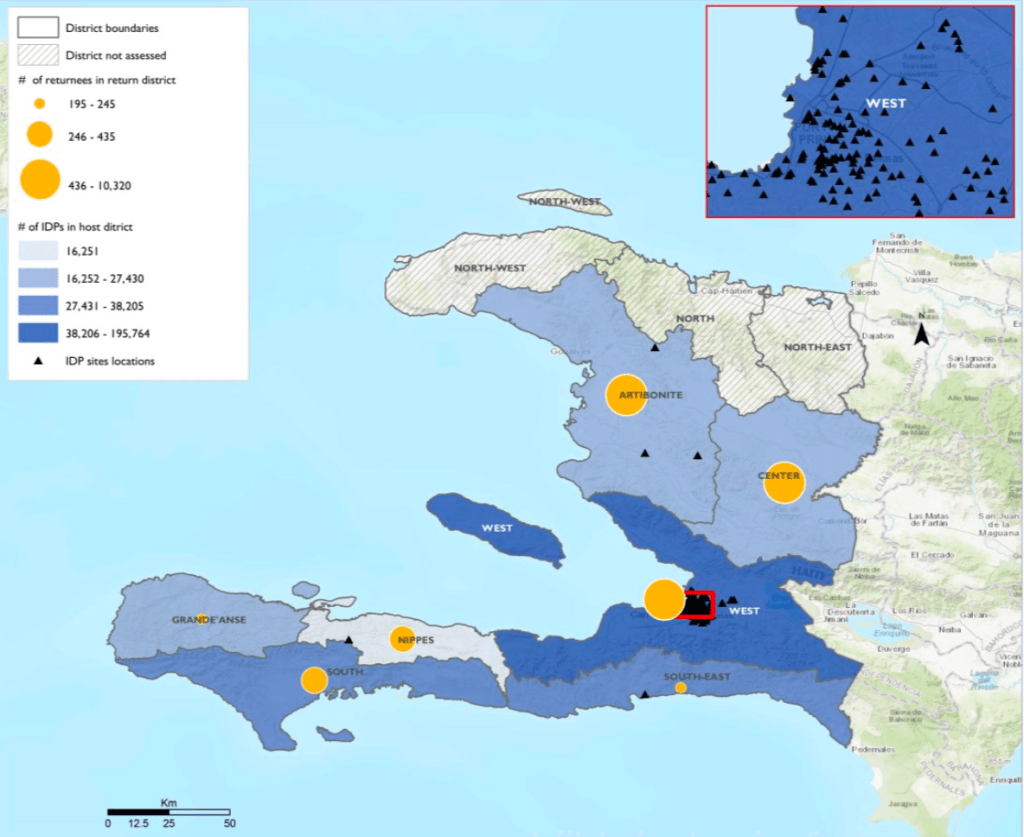

That actual map might well have been a topic for a true Presidential debate was the rise of a terrifying number of displaced persons in Haiti–almost 80,000 displaced households; far over 350,00 internally displaced peoples in recent months of early 2024–and the western hemisphere; not of Haitian immigrants baselessly rumored to eat dogs. The escalation of IDP’s, including some 25,000 “returnees” forcibly flown back to Haiti–per the Displacement Mapping Matrix of the International Organization for Migrations–was astonishing and truly terrifying, the mores as some 50%–over half!–of internally displaced are children, most in the terrifyingly lawless region of Port-au-Prince, where the entire social fabric has unravelled–even if the renditions are flying from the border, many removed from under bridges in Del Rio TX, having crossed the “border” from Mexico, flown in planes from Louisiana, and Florida to alternative airports to navigate chaos on the ground in Touissant Louverture International in Port-au-Prince.

Despite the provision of minimal humanitarian aid–displaced deportees were given a COVID test kit and a hundred dollars on arrival after being extracted and returned to their own “homeland.”

This is the largest and most rapid-scale deportation or expulsion of refugees from America in decades, a forced migration back to a scene of chaos where kids are “treated” in emergency medical shelters after their forced repatriation on airline flights that were the undesired end of their attempts to seek safety in the United States.

But we are discussing Americans’ best friends. The outrageous claims, refused to be corrected as their falsity was affirmed, seemed to sanction violence against the 731,000 Haitian born citizens who are fifth largest foreign-born demographic in the United States. The arrival of Haitians fleeing violence led many to be protected as refugees, Haitian migrants were symbolically returned to the edges of the inhabited world, the increased arrivals of Haitian migrants fleeing violence being turned back to beyond US borders, as if to remap the hemispheric crisis of Haitian migration as an arrival of the outsider from beyond the borders of a known world. But the true crisis of the increase of forced deportation of Haitians, even during the continued humanitarian crisis of gang violence and political instability in the nation, even giving NGO’s in Haiti funds to promote the integration of expelled Haitians in the hopes to help them integrate despite the heightened insecurity in the islands’ frayed society, expelling over 25,000 and refusing to develop any coherent plan for displaced Haitians in the western hemisphere as many flee a nation fearing its imminent collapse and absence of economic opportunities in a nation of increased numbers of internally displaced persons. And J.D. Vance has lead the charge, in many ways, to label legal immigrants as actually “illegal,” even if they legally arrived in the United States as humanitarian refugees, charging some 20,000 Haitians as being in Springfield “illegally” and “illegal aliens,” threatening outsiders as outsiders he imputes charges of having broken the law intentionally and barbarically.

As current deportation efforts of repatriation administration have led Republicans to search for flash-points to make migration return to the election year topic that it was when Donald Trump entered the White House. And the figments of foreign dog-eating men, disrupting the national peace at the domestic front by regarding our domestic pets as food, seems a way to give prominence to the current hopes of some Democrats to pause or end deportation flights and stoke fears about the legal entry that was granted Haitian border crossers–but 1% of those arrested for illegally crossing the US-Mexico border in the first three moths of 2024–allowed entry to the United States for humanitarian reasons since January 2023, by Presidential directive granting Temporary Protected Status to those immigrants fleeing unsafe conditions of civil strife. Sticking to the power of his narrative of dog-eating Haitians’ illegal presence in Springfield, Vance went on the offensive by asking “If [Democratic Presidential candidate] waves a wand, illegally, and says these people are now here legally, I’m still going to call them illegal aliens,” italics added for clarity, questioning Harris’ legality: “An illegal action by Kamala Harris does not make an alien legal.” Three weeks after the September 10 debate, as Election Day approached, Donald Trump said he would “absolutely” revoke the protected status of the Haitian migrants in Springfield, describing the need to “remove” them from “a beautiful, safe community,” claiming power to depot them, trying to coast to the Presidency on a wave of anti-immigrant fear.

And so we are engineering an election around the debates of illegal border crossings, turning a blind eye to the latest real humanitarian disaster spinning out of control in our hemisphere. Despite the return of forcible deportation flights, ending the pause of forcible deportation flights to a city wracked by gang violence, and the decision to no longer grant immigrants Protected Status, the image of immigrants eating our dogs and cats suggested a fraying wall to protect the nation, even as the Homeland Security Secretary tried to urge Haitians not to flee violence by taking to the seas, Trump evoked the decline of forcible deportation since 2021–and only concealed the true violence of their resumption of flying applicants for asylum from refugees fleeing unemployment, violence, and human rights abuses back to a country that cannot provide adequate health care.

The luxury of this sturdy and weighty book belied the fact that most of its content was recycled from existing books. The closed map of the inhabited world above showed at its far left margins recently discovered New World islands; and the dog-like beings shown as hideous marvels of God’s creation were notionally located not in nations, but outside the inhabited world, undomesticated non-human animals seen as freaks of nature, who might appear almost human–

–as on the borders of the known. They were simply, the map suggests, hard to fit to any taxonomy or even any map of creation; if accommodated to the universal scope that the Nuremberg Chronicle boasted interested readers might find among the over 1800 illustrations printed form 645 blocks, in a shop with some twenty-four presses, “so great a delight in reading that you will think you are not reading a set of stories, but looking at them with your very own eyes,” as it grabbed images from available sources, a visual feast that constituted a sort of World Wide Web on the internet before the internet, of similarly dubious truth value. The universal history famously featured “views of the most famous cities and places throughout Europe, as each rose, prospered, and flourished,” often derivative or adopted from an expanding trade in popular prints and city maps, among which were fascinating creatures, cast asthe rather marginal beings of the stateless who lay in no clear order off the map’s face, as if living at its far-flung edges.

As the Chronicle or Weltchronik recycled information from unfounded sources, so the story of pet-eating Haitians, deriving, from all places, from debunked posts of Neo-Nazi websites, and proudly claimed by the leaders of the group Blood Tribe–accusing unnamed immigrant groups of stealing and eating pets from American homes. These are serious folk, a hyper-masculinist group who see themselves and want to be seen as the bulwark of an ethnostate– hardcore white supremacists who reject softer “optics” and are interested in peddling images able to defend their sense of themselves as defending a notion of racial superiority who are prepared to scan the internet for powerful racist images of ethnic violation. And the group seized on the police reports of a potentially stolen cat to accuse Haitian immigrants of revealing their un-American nature and proving themselves foreign even if they had immigrated legally. And the evidence of the immigrant children chasing geese and ducks in the midwestern town of Springfield, Ohio had indeed mutated in the social media ecosystem, in recent weeks, to charges of eating ducks and geese, to lead Blood Tribe to launch incendiary charges of eating pets.

The Neo-Nazi origins of the accusation had led J.D. Vance, the Vice Presidential candidate of the Republican Party, baselessly to cite “Reports now show that people have had their pets abducted and eaten by people who shouldn’t be in this country.” The invented charge was tweeted without verification, or sources, as a way to taunt his Democratic opponent: “Where is our border czar?” The scurrilous rumor entered the Presidential Debates as if it were evidence that the presence of immigrants have been “generally causing chaos” that Vance’s running mate promised was “coming to your city next.” In ways that led many Haitians to fear their lives and part, the charges of eating pets that Blood Tribe promoted went mainstream, but reflected the dark secrets of right-wing nationalists eager to find confirmation of “what real power looks like” as Donald Trump himself adopted their fictional rumor to place it front and center on national political discourse: the leaders of the right wing group, judged among the most hard line, crowed in ecstatic recognition when the viral rumors emerged as talking points in a Presidential debate, even if a former member of Blood Tribe lamented publicly the ill effects of the “fake Haitian stories” intentionally “cooked up . . . a week ago as an election ploy” delivered before the august Springfield Planning Committee, but that social media helped quite strategically to propel to a forum to decide who the nation chose as President.

The impoverished nation of Haiti has long been construed as an icon of the dangers the outside world poses to the United States if we fail to exercise vigilance. These were men’s best friends, and the dangers of the blurring between dogs and dog food that were said to be going on in the bucolically named town of Springfield, Ohio suggested there was something wrong in America–this was a boundary-crossing of import to the entire nation, that was sleeping in an age of vulnerability, when nobody was guarding the gates. And it hardly helped that Haiti had topped the President’s list of “shit-hole countries” and distinguished as a nation whose citizens “all have AIDS”–a remark credited to the former President was long strenuously denied. The ungrounded generalization was perhaps based on the March 4, 1983 CDC Guidance grouping Haitians in a notorious “Four-H Club” of risk groups for AIDS–Haitians, hemophiliacs, heroine users, and homosexuals–even if the report conceded “very little is known about risk factors for Haitians with AIDS” at present, papering over the fact that no actual connection existed between the symptoms of the terrifying Kaposi Sarcoma cancer caused by the AIDS virus and spread and found in mucous membranes in the human body.

There was no causal connection here in these groups of the afflicted–but the association was powerful. Trump has a mind like a steel trap, more than being a man for details, especially given the drama (confirmed by genetic analyses) that AIDS first arrived in New York City, before the first patient was diagnosed in 1981 in Los Angeles, and was present in the blood samples of at-risk gay man screened for Hepatitis B, after probably arriving far earlier in the island of Haiti, where it has been documented in the Caribbean island from 1967 and a Haitian strain from 1969, circulating in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Early Patterns of HIV-1 Subtype B as it Spread via Haiti to the Americas in the 1970s/Nature October, 2016

The demands to end the silence about the true scale of the AIDS epidemic, even before the protests to win funding for research into the disease, was long drowned by an eery silence that imagined Haiti was not merely a site of transmission of the disease–now imagined to have occurred in circa 1963-71, but whose spread was incorrectly imagined to exist only among vulnerable communities–heroin users; hemophiliacs; Haitians; homosexuals–rather than a national health risk. Even after researchers recognized the gravity of the public health situation by January 1983, even as the CDC limited vulnerability to set groups of Haitians–with hemophiliacs, heroin users, and homosexuals.

The increased fears of the spread of AIDS was increasingly understood by the metaphor of a plague, if not a punishment. It inspired fears of alienation of the medical body analogous to syphilis or leprosy in an early modern Europe. For circa 1500, Europeans described Syphilis as “that foul contagious disease which . . . had invaded mankind [first] in a few places, and since overflows in all . . . for punishment of general licentiousness;” the dangers of AIDS were for longer than we knew better parsed among “risk groups” compromised by a decline of virtue or moral pollution–handily erasing how arrival of Europeans introduced multiple deadly diseases to indigenous in both the “New” World and Australia, AIDS was believed to arrive ultimately from across the Atlantic and from the “dark continent”–clearly racist stereotypes informed the etiology of its spread from Haiti to the Americas and United States often dislodged form science. Meanwhile, of coruse, Africans, as the disease devastated populations in Zaire, mapped its creation to a CIA laboratory in Maryland, rather than a “the revenge of nature” or “gay plague” seen in terms of virtue: AIDS was a story of global imbalances. Ether way, the sudden and pernicious proliferation of figures of speech recast disease as a threat of pollution infecting the social body truly tantamount to a fear of national survival. Susan Sontag felt it was “truly monstrous to attribute meaning, in the sense of moral judgement, to the spread of an infectious disease,” the apocalyptic terms of the disease made its origin readily mis-mapped–by “at risk” groups and origin–was mapped quite precisely in Haiti.

Hysteria is a treasured trope of public communication in times of social and political crisis–but not a disease. The fears that were transmuted into having the charateristics of a disease or contagion from outside of “our” national borders however stayed firmly lodged in Donald Trump’s psychic geography and spatial imaginary. They informed the latest broadside he has issued in the geography of fear: “If you look at the stats,” Trump was fond of saying from the White House, “if you look at the numbers, if you look at just–take a look . . .” If they only did so, most anyone might grasp the scale of national dangers posed but he island-nation that has suffered so much from economic rapaciousness and natural disasters in an age of global warming. Haiti is actually by afflicted by devastatingly low expenditures on health–creating a flash-point in the hemisphere–that continued to the fears of health in the AIDS epidemic conjured the mapping of disease in non-empirical ways typified by early modern fears of the arrival of syphilis from the New World, or from foreign nations.

The image of the stubborn presence of lesions on the body that were not able to be explained maps on the boils that afflicted the syphilitic body in what seemed only to be credibly explained outside diagnostic categories as akin to a wrath of God or astrological fates–

–whose etiology was mis-mapped by the French as the “Neapolitan disease,” English and Germans as “the French disease,” and Turks as “the Christian disease” in a moral tenor invoking the boundaries of faith; Russians mismapped he “Polish disease” while Poles bemoaned the “Turkish disease.” The misidentification of syphilis suggest saliency of boundaries in early modern Europe to seek explanations for the arrival of the affliction by vectors of communication. “God save me from the French disease!” warned an early woodcut showing symptoms that afflicted a syphilitic whose body was afflicted with boils without any readily available cure.

The specters of syphilis existed circa 1500 in an increasingly bordered and globalized world, mapped by national boundaries in print culture, and not only in maps of Ptolemaic derivation, distancing “others” behind geographic borders that shored up security behind imagined barriers in an era of unprecedented global economic and cultural exchange. The current demonization of The demonization of our nearby geographic neighbor, Haiti, both geographically proximate but epistemically removed, might be better mapped as the nation which not only threatens America by dog-eating immigrants, but by disequilibria of public health. Haiti offers quite terrifyingly stark discrepancies in health care in a globalized world. For even if maternal and infant mortality have been halved in the nation, and life expectancy grown, due to World Bank aid, only two thirds of children are getting vaccinated for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis, and it has the highest maternal mortality in the western hemisphere poor. And in early modern Europe, and perhaps also lurking in the back of the collective consciousness, dogs were seen as vectors of contagious disease and plague, as the bizarrely astrological image of the fear of contagions that were passing through all of Italy in the 1650s, crossing borders from port cities as Naples and Genova to Rome, carried by the fates and, closer to the ground, by rabid dogs, but which Venice need (it was argued) not fear.

Anotomia della Peste (Venice, 1657: Gio Pietro Pinelli)/Wellcome Collection

Venice need not fear, perhaps, the plague dogs of Italy, or the contagions as signs of divine wrath, putrid humors, and, if its port was exposed to the influence of the stars, contagious winds, or the pestilential cadavers that have accumulated in city hospitals across the peninsula. The dog, looking up at the stars as if almost conscious of her fate as a vector of disease, but caught on candid camera, was clearly the root of the virus that stood to devastate the unsuspectingly tranquil lagoon city.

But there were reasons for Haiti to be a site of potent fears in the developed world. The lack of care that those in remoter regions of the impoverished island of over 3.3 million residents is among the most difficult to reach by health services, due not only to systematic economic exploitation in the postcolonial era, but the challenging geography of the island’s marginal areas. And it is no surprise that we might not speak much about these difficulties, as preoccupied as we are with the specters of immigration, as Haiti, an island that was an epicenter not only of the disease but of sex tourism, was mapped in the public health warnings issued by the United States’ Center for Disease Control in 1982 in public warnings that included as at-risk populations homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroine users and Haitians, and continued to map Haitians as demonized others, as if the nation was a vector for disease, rather than unprotected sex or needles, keeping them on the list for three years until the disease was seen as knowing no clear maps of sovereignty that meant its citizens were indeed at more risk. The Center for Disease Control removed the national group from the list of “at risk” only three years later, long after the list was retired; but conceptual maps are slow to alter. Trump was ready to label Haiti as having “a tremendous problem with AIDS” as recently as 2021, and to light a fire under his campaign for President, he is ready to conjure the specters and bogeymen threatening the American people from the island, as if vigilantly mapping dangers facing the country. A self-confessed germaphobe, Trump styles metaphors of disease as questions of national security issues with truly terrifying rhetorical abandon.

Old stories of unauthorized–floridly recast as “illegal”–immigration became a stories of boundaries of safety, preventative caution, failures of due vigilance, and border guards, as well as, of course, vulnerability and compromised safety or peace. Even if it wasn’t true, the story was so gripping, bestselling author J.D. Vance felt, it demanded dredging it up from a baseless internet rumor to the Presidential campaign in its final months. More to the point, it demanded attention not as only a “story” but as a way to dramatize the actual threats that most Americans felt about immigration, a phantom menace he has worked hard to keep in focus–even blaming a national housing shortage on illegal immigrants, even if few would want to live where illegal immigrants live. “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’ what I’m going to do,” a defensive J.D. Vance let Dana Bash know. The “story” conjured feelings of insecurity not captured by facts of border crossing, criminal apprehension, and real threats–perhaps in part as the actual statistics of apprehensions along the Southwest border had only increased by 5%, even as illegal border crossings are “soaring to record levels”–despite the fact that apprehensions of immigrants on the border spiked in 2014 and 2019, and the current “surge” is a backlog of demand with the 2020 border closure due to COVID pandemic.

But there is nothing like a good story to capture the urgency of our national vulnerability, and the urgency of dogs being eaten in real time is far more dramatic than the detail demanded to parse immigration policies,–or obscure the need to pay attention to the reasons motivating immigration. Neither was seen as worth attention in the chaos with which restrictive border policies were adopted under President Trump, reguaraly confining asylum seekers south of the border before appearing in immigration courts, and the shifts in no longer expelling unaccompanied children from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador who are in Customs and Border Patrol custody. Yet our data visualizations suggest that spikes of immigration can be parsed by policies of political party–

Monthly Encounters with Unaccompanied Children on US-Mexico Border, Dept. Homeland Security/Economist

–despite the difficulty to house families of migrants in detention centers built to accommodate adult males, and the policies of separating children form parents during the Trump era of border policy depressed count of unaccompanied children, and conceal a change in tallying immigration–not the almost immediate jump of illegal immigration Homeland Security statistics show.

We are not talking about the dynamics of immigration flows from countries of rapidly deteriorating public safety and public health, as well as corrupt economies, even if these are real stories of human interest. But we can talk about the safety of domestic pets in our own homes. And if we might map the number of stray dogs needing care in Haiti as four-legged proxies for the dire costs of a crisis in public health, recently exacerbated by natural disasters, as a real concern of mapping human-nonhuman animal relations, in appeals for assistance for stray street dogs. It could be that the dangers of a division between human and non-human animals broached by Feed the Strays as especially “at risk” in Haiti, where it seeks to target “deep-rooted feelings of resentment toward dogs” by encouraging nurturing relationships for the dogs in different regions of the nation, by tackling the difficulties of street dogs by setting targeted goals of fostering humans to care for dogs feared as “strays” as a question of education “on the responsibility of caring for dogs” and “cultural sensitivity” only demonize the nation as out of step with with world in pet sympathies as a continued part of the civilizing process–rather than allot actual public health resources overseas.

The Dogs of Haiti

It may be such paternalistic feelings are well-intentioned. They install and exploit a global picture of inequalities, insisting on the low cost of creating such more caring feelings in a crisis of sympathies to the strays on Haiti’s streets who demand American sponsorship for dog futures. (We are good at exporting our feelings towards animals.). The urgent appeals for inter-species affection effectively pull on heart strings, and seem rather low cost, but they manage to bracket the broader dynamics of healthy cross-border relations.

The image of the friendly dogs that were kept on Noah’s Ark couldn’t have been totally happy at being cooped up for forty days and forty nights, but were, to come full circle, imagined as smiling and friendly beasts among the species selected for global survival during the Deluge–the recession of whose waters was, as it happens, mapped for readers of the Nuremberg Chronicle by that world map showing the dog-headed people living on the world’s far-off margins with which this post began, and that I called attention to as illuminating a deep-set geography of underlying attitudes of articulateness and abilities of language at the time of contact with what soon emerged in maps the so-called New World. The lovely illuminated image of an apocalypse illuminated in circa 975 showed a pair of prancing dogs, tails curled upwards as if wagging with excitement, despite the ark’s confines, as if they knew Noah had received an olive branch at the end of their forty days and nights at sea–and were dying to get out to prance around on dry ground.

The trials of the long-confined canines were masked by those animatedly wagging tails–making one imagine they were in, in an act of inter-species communication, on the secret of the arrival of a dove bearing an olive branch that announced receded floodwaters, before any other animal occupants of the ship–