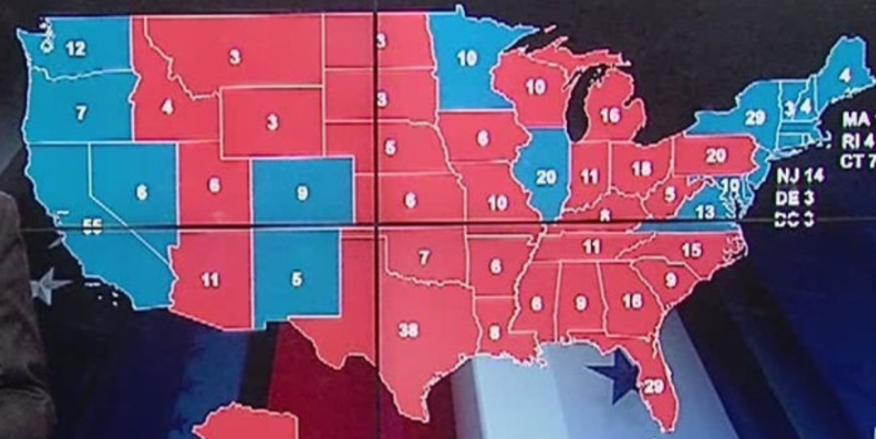

As news anchors stared directly at the camera on Election Day 2016, they might gesture mutely to the apparent dominance of Donald Trump’s presidential victory, shown the blanket of bright red polygons that took the viewer’s breath away by their sheer continuity affirmed that the people had spoken definitively. The map was a bit of a total surprise, evidence of the disproportionate appeal of Trump across most states other than the coasts. And it is an icon with which Trump has taken to celebrate in an almost proprietorial way as the result of his labors and his own hard work that he tried to celebrate in addressing the Boy Scouts’ annual jamboree this year. Casting a now-forgotten moment of compact between himself as Presidential candidate and the nation, incarnated in a map, and presenting it as a personal triumph, he recalled the electoral map as a definitive rebuttal of a “dishonest” press and media, urging we all “remember that incredible night with the maps and the Republicans are red and the Democrats are blue; that map was so red, it was unbelievable,” and rhapsodizing how the map struck so many dumb with disbelief so that “they didn’t know what to say?” The electoral map, for Trump, provided the ultimate confirmation for a “dishonest press” and “dishonest media,” but just how honest was that map, anyway?

The map seemed to show a dramatically lopsided margin of victory, but it of course concealed just as much. It seemed to celebrate red nation, indeed, until one considered the concentration of population, and drilled deeper down into population distributions than an electoral map can reveal. The map however remained so cognitively powerful that the geodemographics of the 2016 Presidential election seems to mark the return of a landscape of blue vs. red states, and a sense of the self-evident nature of a newly redivided republic. The promise of national maps to parse the division of the popular vote–a conceit fundamental to the electoral college–however creates a false sense of the breadth of support or the links between an individual candidate and the land–distilling the distribution of the vote into a false if compelling continuity of a sea of bright red. And it is not a surprise that the map has become a favorite demonstration of the extent of Trump’s popularity, and the myth of a landslide victory not seen in earlier years. Even if its geodemographic illusion demands to be unpacked, the scale immediately gave rise to the magnification of a margin of victory that is entirely to be expected from Trump.

But for a national figure who has convinced what seem continuous swaths of the nation’s so-called heartland he could speak for their interests, it is striking that despite some considerable variations among voting patterns, the intensity of that red block so clearly endured. The distribution illustrated the intensity of the affective relation to the candidate, or rather the failure of achieving any deep to Clinton as a candidate–but became a symbolic icon of Trump’s claim to represent the nation’s ‘heartland.’

Ben Hennig, from results of 2016 US Presidential Election

Ben Hennig, from results of 2016 US Presidential Election

The geodemographic conceit was not much evidence that he actually did. Despite the strength of such affective ties, Trump has only slim familiarity with that heartland–and rarely showed much tie to it. Despite the compelling nature of the geodemographics that suggest Trump’s close tie to the nation’s center, the region Candidate Trump convinced was ignored by the media and press alike was largely avoided by Candidate Trump. And few of its interests can be said to have been sustained by the President we now have, whose electoral success in the upper midwest will be hard to measure with a feared decline in health care subsidies, should the Affordable Care Act be repealed and Medicare gutted, leaving older working class voters in the cold, as a new tax code does little comfort.

But was Trump ever so tied to the band of red running vertically down the country? For the region that voted for him is increasingly becoming disaffected, as he qualifies his opposition to NAFTA and his assurances about the need to construct a border wall, in ways that raise questions about his strong showing across middle-America and his identification with the people’s will. Yet the iconic map itself may have provided for Trump himself a bit of a mirror illusion–as if to trigger a sense of recognition of his identification with the entire nation in ways that came as something as a surprise, it also effectively validated his long-time aspirations to the presidency, not only for the media, but for himself. To be sure, the notion of a “heartland victory” reflected the growth of a tendency to shift Republican on a county-by-county level, which reflected a targeting of the midwestern states that seem to have been conducted below the eyes of team Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential election; Trump’s vote share substantially grew in Ohio, West Virginia, Iowa, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Missouri.

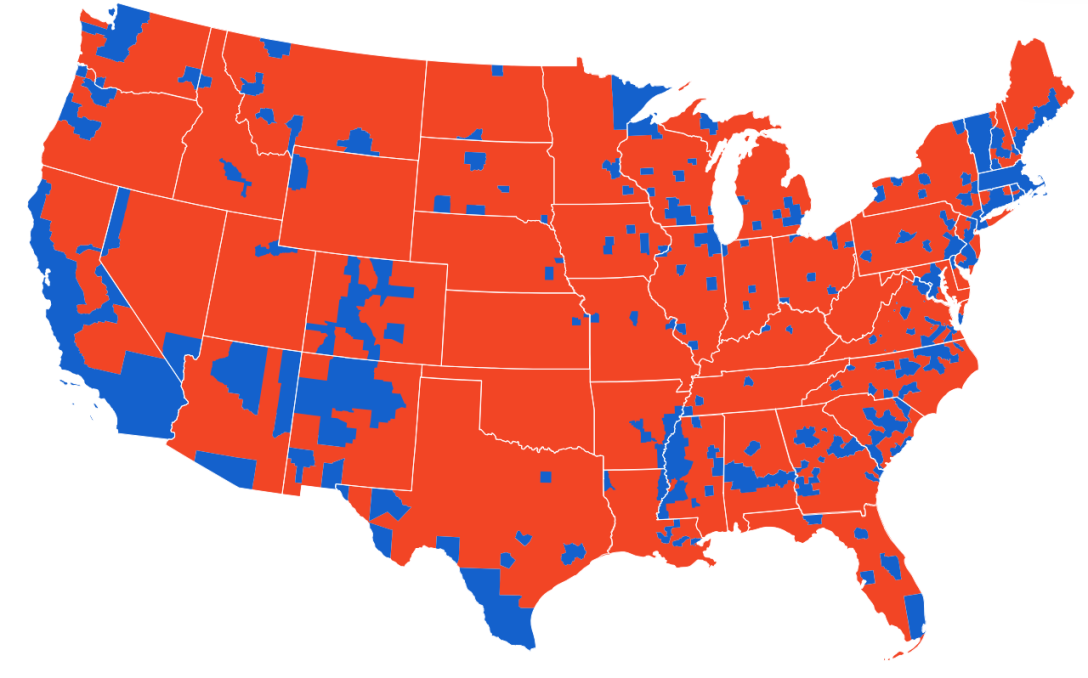

By normalizing the same choropleth of Trump votes, or using a color ramp that will foreground the percentages of voting intensity, a recommendation for all future voting maps Kenneth Field rightly suggests, the deep intensity of reds are brought out better, focussed almost in targeted sites in ways that might merit more retrospective scrutiny.

Kenneth Field

But the deep reds of the electoral map were the most compelling to The Donald, and continue to lead him to retreat into rhapsodies, some eight months after the election, in Cedar Rapids IA, about how “Those electoral maps, they were all red, beautiful red.” As much as Trump has seemed to be processing the legitimacy of his victory well past the first hundred days of his term, a framed version of the electoral map infographic is rumored to have been hung, framed, as an icon in the Trump White House for visitors, to which he can point only to ask, as if in desperation, ‘Aren’t you impressed by this map?’” The map has become something of a calling card to which Trump seems both boastful and still gleefully processing, perhaps precisely because it was so often broadcast on TV. The image transformed to a wall-map seems a needed confirmation of the areas that sent him to the White House, and has become a distributed visual for news interviews, as if its presence reminds interviewers that they are engaging with the representative of the real country.

Why post the map on the wall? The infographic presumably captures those areas of the US where Trump must continue to address outside Washington–and of the disempowerment of the mainstream media–as if to remind him of his ongoing sources of strength. Trump cannot conceal his pleasure to continue to crow, reveling in his unexpected ability to cathect with voters across so much of the northern midwest if not the silent majority of the national interior, and the map confirms a moment of joy: the map of a “sea of deep crimson” offered credible needed visual confirmation of the legitimacy his newfound power that responds to continued crises, and a sort of symbolic consolation: Trump, as if planning a billboard to the nation, requested no one less than the Washington Post run the image on his hundredth day in office, perhaps in hopes to brainwash the nation by the repetition of that apparent sea of deep, deep red. It reveals, moreover, the very silent majority that Trump had long evoked: Trump’s skill at resuscitating the Nixonian conceit of a “silent majority” supporting the Vietnam war and rejection counter-culture became a bulwark of sorts against the press; it was particularly pleasurable as it re-appeared within the very news maps that the media produced which were broadcast on television screens, in ways Trump himself wants to continue to broadcast. Trump not only holds TV in famously high regard–even if he did not mostly watch television for all of election night–it is almost credible that the iconic electoral map was framed for the White House walls, if distorting , offered a recollection of the magnitude of his margin of victory that must be comforting to show guests.

The considerable shock of the electoral results led many readers to recognize the reduction of support for the Democratic candidate, so well-qualified, to isolated regions near the more diverse and reliably Democratic coasts. The visualization of disembodied counties for Clinton registers an immediate anxiety in projecting the angst of isolation from the same heartland, as if to show what seem only pockets of Clinton supporters in a very tenuous archipelago with outposts hewing predominantly to the nation’s coasts, as the outliers of the vision of America that Trump was able to propose. As much as showing the lack of contact of Clinton’s messaging to so many counties in the in-between “forgotten heartland” that the Trump vote seemed so successfully to invest coherence in, the image shows a heartland that is almost abandoned by Clinton voters who seem not to have migrated from the country, but seem exiled from an increasingly fractured nation, in their own filter-bubbles, in which their own place has been rendered up for grabs.

The geodemographic illusion of such fracturing however belies the sharp dissonance that a deeply provincial figure long resident in one of the nation’s largest metropoles felt to much of the country and the nation that he so convincingly claimed he was able to represent. Trump’s ability to have convinced much of the country he could guarantee their continued safety lies in contrast with the limited presence Trump ever remained in many of the regions that the force of his Presidential campaign so solidly and deeply colored red. The clear divisions in the country that emerged in the 2016 Presidential election revealed a clearly widening set of divides between islands of populated blue and regions that trusted different news sources, more suggestive of a divide driven by eduction than wealth, using available census data on education from the Data Observatory in a CARTO visualization of the lower forty-eight, to create a more finely-grained record of the distribution of votes that allows the chromatic vacation to pop–

Michelle Ho‘s Carto Blog

Michelle Ho‘s Carto Blog

While the “split” between “heartland” and “blue islands” pops out better in the above courtesy the Carto dashboard, the surface of a flat map can conceal the extent to which the vote broke among more and less populated counties, as the following sizing of counties by votes received by Clinton (blue) or Trump (red).

The thin distribution of red dots calls into question the existence of “heartland” in the nation, and how much the notion of a coherent heartland is the creation of a map, suggests the extreme oddity of an election where votes so clearly broke with electoral votes. Notwithstanding the visualization of Alexis Egoshin being picked up on right-wing sites as a basis to argue for the need to continue the electoral college to represent the mass of land, pictured as a plateau, with which Trump won decisively, and could be called “TrumpLand” as it was so solidly voting in his favor–

–the thinly stretched archipelago of Tim Wallace might defy geographical explanation, and be rooted as much in media bubbles, fractured politics, anti-immigrant sentiment as it can be said to be geographically determined, and perhaps the tendency that we have to believe that there could be a geographic explanation at the root of the Trump victory, or a definable “Trump” community or constituency might be more tied to the contingency of information economies than anything as easily mappable in purely objective terms.

1. Trump’s own overly inflated claims to represent the red expanse of the rust belt was, for one, most strikingly undermined, however, by his regular return flights on his Boeing jet to his New York penthouse while on the campaign trail. For as he campaigned, Trump maintained a remove from much of the country, even as he evoked the “rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation,” and excoriated the policies that he claimed created them, urging voters to “take our country back again.”

While we are still trying to understand what he meant by “American carnage” save as a way to conjure fear, and a landscape beset by violence and “drugs pouring into our country and poisoning our youth,” within an “environment of lawless chaos,” the exaggerations of specters of social threats that proliferate from Trump’s mouth seem to be as emotionally figurative as they reflect actuality, and more a reflection of the America on television news than statistics. The call to “shake off the rust” appealed, however, by binding themselves to the possibilities of “wistful time travel” that Donald Trump’s candidacy seemed to promise voters, as Zadie Smith has keenly observed. Who better, in fact, to convince most of the country that he could bring it out of the shadow of threats of terrorist attacks that 9/11 has continued to cast across much of the nation, as if creating a bond of reassurance that stood in for any other tool of manufacturing consent.

And the tie was reified in maps. A land map magnifying the extent of Trump’s 2016 US election results in the electoral tally was widely trumpeted by right-wing news sites, as well as the nightly news, to proclaim Trump’s was a landslide victory–even though the differences in popular voting was not only decisive, but Trump’s own relation to the nation he now leads is poorly understood.

Trump can be claimed to have converted more far more Republicans to his candidacy than recent Presidential candidates, but Trump was long an outsider. And Trump’s imaginary tie to nation seems just that, despite some considerable crowing over Trump’s close relation to the American heartland that he claims as deeply tied to and to be the territory that he best represents–

–although these stark divisions in the distribution of voting patterns disappear in the district-by-district electoral votes map posted by Mark E. J. Newman in clearly contrasting stretches of red and isolated islands of blue with only the occasional all-blue state.

University of Michigan/M.E.J. Newman

University of Michigan/M.E.J. Newman

But the map of the distribution of electoral votes is only the start of the attenuated relation Trump has to the country. Trump’s insistence on an alleged “mandate” or a “massive landslide” seems designed to provoke collective amnesia by its repetition–Trump’s own convictions seem born from the illusion of democracy displayed in broadcast electoral maps on TV news. For the vagaries of the current electoral system meant that a shift of four counties from one state to a neighboring state, data scientist Kevin Hayes Wilson pointed out, would have redrawn the map of the election, and our picture of the nation to a more comforting baby blue–although this tantalizing alternate reality is not to have been, but is in fact not so far away at all:

Kevin Hayes Wilson/Redraw the States

Kevin Hayes Wilson/Redraw the States

Yet the victory of a continuous stretch of red is so iconic that the mapping of votes by counties is taken as an affirmation of regions of deep scarlet, as if the county is a meaningful unit for displaying voting tendencies:

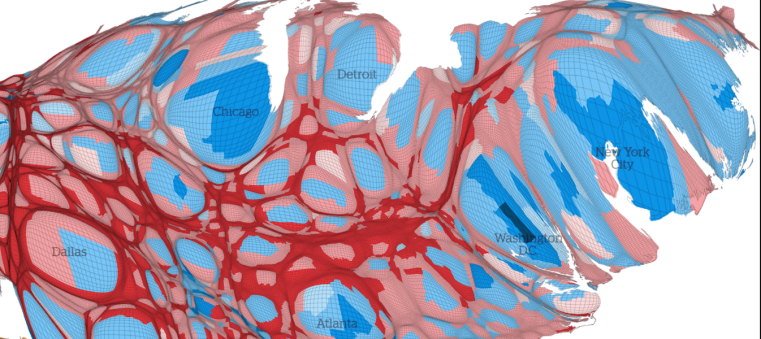

The image of “red” states or counties is so potent, however, that the image is taken as evidence of the appeal of Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again”–as if the slogan spoke to the heartland–that converting the map of counties to a cartogram which sized counties by population and voter size seems to be a weaponized warping of the nation for polemical intent, in which the center of the heartland has been stretched into a skein of thing red strands that slighted the region by stripping it of its political voice, as if created by a leftist cartographer who polemically diminished the heartland by rendering it as so much connective tissue in contrast to the prominence of blue cities.

Benjamin Hennig (detail of Hennig’s cartogram of 2016 US Presidential election)

Benjamin Hennig (detail of Hennig’s cartogram of 2016 US Presidential election)

The rendering of the heartland as a stretched skein of what seem ruts in the American landscape seems the polemic of a leftist cartographer from a metropole, to many, ready to slight the heartland in favor of the magnified cities whose names appear on the map.

To be sure, the tea leaves of county voting patterns do parse voter populations: to be sure, Trump did almost twice as well as Clinton in those counties that were at least 85% white, rural (fewer than 20,000 inhabitants), and won huge preponderance of the votes–70%–where less than 20 percent of the population has a college degree. But the continutiy that one can translate into spatial terms is much less clear, and the county is not the clearest organization or translation of a voting bloc, despite the clearly greater diversity of the cities, and the dominance that Trump exercised in counties that were predominantly–85%–white, in ways that may have single-handedly overturned the electoral map, and were the audiences to whom the visions of prosperity Trump promised most appealed, and where the Democratic candidate’s losses in comparison to Barack Obama were big–and where Trump won almost twice as much of the counties.

Bloomberg, “The Voters Who Gave Us Trump” (Nov. 9, 2016)

But, by and large, the rhetoric of the red intensity of maps perhaps have originated as pollsters talking among themselves, and against each others’ expectations, as much as the distribution of a close connection to the candidate; the intensity of the red appeared in a contrast of the predictions of the popular vote distribution against the actuality, even if it seemed within a margin of error, as the final actual distribution–

–broke ever so slighty, but so definitively and so strikingly, from their expectations:

2. Trump’s claims for a personal relation to the nation is far less apparent. It demands to be scrutinized, as it only seems demonstrated in electoral maps. Even though seven out of ten Republicans voiced expressed a preference for America of the 1950s rather than that of today, and Trump’s candidacy both entertained and invited such acts of willed nostalgia, it’s hard to believe Trump’s own proximity to the nation’s heartland is based on “lived” experience. The surprising story of Trump’s campaign may be the alchemy by which he cemented a bond among evangelicals, with the help of his only nominally Catholic running mate, Mike Pence, paired with the poorly thought-out strategy of Hillary Clinton to focus on cities, rather than rural areas or the economically depressed areas that reject the effects of globalization, which could have spread those blues out along the map with far greater surety–a need that the map of Hayes Wilson reveals by the washed out areas of even the states whose delegates she won.

For while growing the share of Republican voters across several states presumed to vote Democratic, including many in the so-called “rust belt”–here colored dark red–

–President Donald Trump seems himself to be quite alienated from the very folks whose economic interests he persuaded he would strongly defend, and less than ready to spend time there, save in his Florida estate, the new Winter Palace, Mar-a-Lago, ensconced as if forever a foreigner to much of the nation.

3. The familiarity that Trump created with the nation seems rooted in an imaginary, built on the lifestyle of the Trump brand–even though his election leaves us with a shrinking horizon of expectations. To say Trump ever knew much of the country is not only an exaggeration, but an outright deception that was willfully perpetrated if not orchestrated by his campaign. Despite the broad appeal of a Trump lifestyle, Trump seems to have little connection for the man in the street or his job. But his keen sense of playing the salesman for his brand, which promises to be a central part of his Presidency, led him to have so much practice at delivering people’s fantasies and recasting the art of promising anything but the greatest product ever to “innocent . . . exaggeration.”

For his policies betray little familiarity with the nation, beyond empty sloganeering, evident the belief that a repeal of the ACA would help the nation–when it would most likely, as Paul Krugman noted, “send the numbers right back up—[after] 18 million newly uninsured in just the first year.” And the imposition of punitive measures against American companies who chose to locate their production overseas or in Mexico, and even more punitive tariffs against foreign competitors demand to be called out as instances of economic bullying, rather than anything like a realistic economic policy or plan. And the notion of a 20% import tax would be passed on not to the Mexican government, but to heartland consumers who would pay for it in their purchases. And ending the American Care Act would put almost a half a million aging folks off of health care, in ways we cannot yet fully map, but will have deep consequences for the very deep red “heartland” that Trump champions. And as Anwar al-Awlaki, the radical Islamic American-born al-Qaeda preacher, foretold that the “West will eventually turn against its Muslim citizens,” Trump has successfully made his prophecy an actuality. (“You were a nation of ease,” al-Awlaki had addressed the United States ominously, inviting a similar sort of time, but “imperial hubris is leading America to its fate.”)

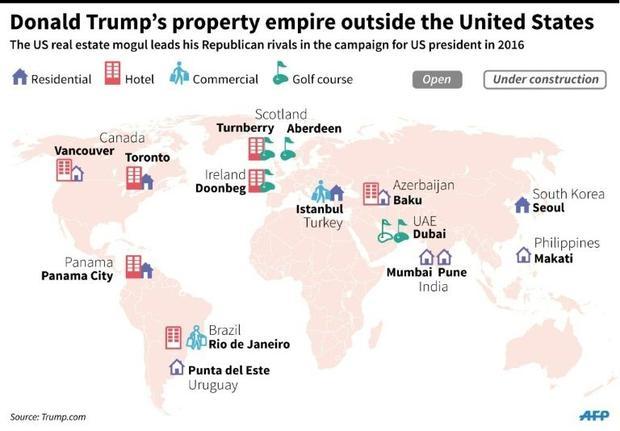

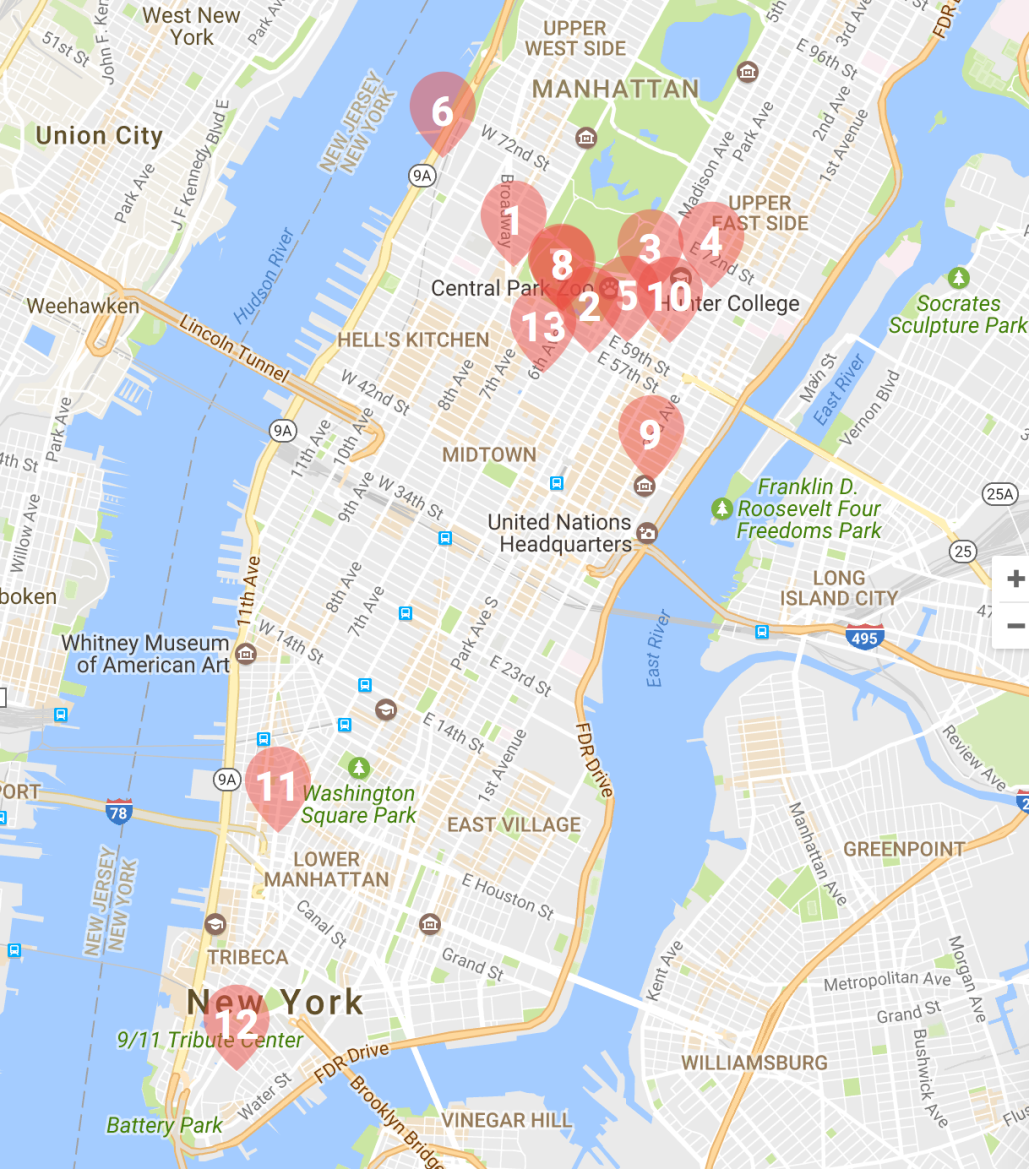

Although Trump claimed to speak for the country, he was most famous for retreating to the confines of Trump Tower: he was, confessed long-time political operative Roger Stone, something of a homebody. His attachment to owning properties in Manhattan and his estate in Mar-a-Lago were so great to start rumors Trump declined to make the White House his regular residence as President. And when Trump regularly returned to New York City or Mar a Lago, he always kept most of New York at a remove while sequestered in Trump Tower. While totaling some 276,000 miles in the air by late September since announcing his candidacy for the U.S. Presidency on June 16, 2015, Trump traveled over half of the days since announcing his candidacy, even while visiting far fewer places than other Republican candidates and fewer than his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton. And if one is to judge his familiarity with the country in terms of the cities where he chose to build and promote hotels as evidence for the sites he earlier visited, it is striking that the sites of Trump’s North American properties are located on its coasts, or outside of the very areas where his campaign was so wildly and only perhaps improbably successful.

For on the campaign trail, Trump buzzed about the country to create the sense of direct contact with constituents even without spending that much time in a single place, but regularly returned to New York, he may have visited places like Brooklyn, where Clinton’s campaign was based, far less frequently–and spending a considerable amount of time on the campaign trail sleeping in Trump Tower, if not resting in the large bed stationed in his 757; tweets from sites on the campaign trail conveyed his endless motion, but many began “just returned from . . .” in multiple tweets during the early days of the primary.

Were the steady accusations of his opponents’ tiredness but projections of his own somnolence or power naps?

Trump was regularly cast by ABC news as Palm Beach’s Most High-Profile Homebody by the year’s end. Trump was no doubt tired out by the extensive campaign where he projected his exhaustion first onto Jeb Bush and then, more dramatically, Hillary Clinton: for two weeks in December, rather than assemble his incoming cabinet, the PEOTUS remained in the sumptuous Mar-a-Lago, rarely leaving the estate for golf and dinner at the Trump International Golf Club, or Christmas Eve mass, and meeting with his transition team just “a stone’s throw from the croquet garden,” before returning to Trump Tower in January to assemble the rest of his incoming cabinet in the nineteen days before his inauguration–and expressed reluctance in leaving his aerie in Manhattan for periods of a week after assuming the Presidency, proposing frequent returns to his three-story penthouse on the 58th floor of Trump Tower for family time during his Presidency.

4. Even if he has warmed to the White House’ decor and furniture soon after moving in, Trump is a man who has stayed put in his lavish multi-floor apartment for much of the last three decades, and it has provided the perspective from which he looked at the United States–and may offer a perspective from which the strong opinions of his policies were formed. For a candidate who saw the sumptuous quarters designed in Louis XIV style as a tribute to his creation of his own self-image, was his creation of a time-frame also particularly revealing? Did his identification with an apartment decorated in 24-karat gold and marble and furniture and tapestries in Louis XIV style with a Tiepolo ceiling put him in ideal place as a candidate to promise a project of time travel to Americans seduced by his timeless lifestyle–

so effectively isolated as he was from the changes in the external world over the past twenty to thirty years? (And doesn’t being called a “homebody” mean quite a different thing for such a home?) For a man who grown up in a house with four white columns that were adorned with a confected crest and coat of arms and white columns, as a palace set apart from Queens, N.Y., with twenty-five rooms and nine bathrooms, the palatial abodes that he has continued to created for himself and his family similarly stepped outside of time.

The series of luxury hotels with which Trump’s name has been synonymous promote lifestyle packages promote pastiches of European luxury that are, after all, the tricks of the trade of a master hotelier–whose expertise is to offer an escape to a new comfort zone. Since winning an election for United States President seems to provide only an extension of the art of escapism he has already refined in the political sphere that can translate to the trade of the hotelier, it seems no surprise that recent publicity even integrated the image of the White House facade to a promise of escapism at Trump International located in Washington, DC–even if this reveals something of a conflict of interest or confusion of jobs, or rather imagines the sort of “Suite Escape” in which Trump Hotels specialize the possibility of looking at the photoshopped blanched federal Environmental Protection Agency through drape-graced windows in utmost Trump luxury, even if it does, as Philip Bump noted keenly, capture the “mess of conflicts of interest” that Trump is now likely to himself face far beyond that hotel.

5. For it seems that a large part of the promise of Trump Hotels is to offer to assemble for their eager visitors pastiches of the “finer things of life,” such as the guesthouse in the Blue Ridge foothills, combining a Georgian-style mansion with old-world elegance from Waterford crystal chandeliers, oil paintings, and statuary in surroundings recalling the Tuscan countryside; every one of his Trump International hotels or Trump Hotels is prized for its own thematic program of interior decoration that offer to their visitors. This is distilled in the utterly escapist residence Trump loves in Trump Tower, whose time-shifting decor to transport one to an idyllic past, free from social consequences or concerns, that might be the emblem of the escape he offers the country.

The notion of Trump sequestered, as a self-made Rip van Winkle, is somewhat appealing. Donald Trump rarely travels, and seems something of a homebody, flying home regularly while he was on the campaign trail on his private jet–and asking the Secret Service to follow him home, on an air company he owns. To the tune of $1.6 million, agents accompanied him on regular return flights on TAG Air, on which he logged some $6 million personally, boasting “I could be the first presidential candidate to run and make money on it,” as he walked to the bank, even outfitting his own ostentatious Boeing 757 jet at a cost of $1 million that situated his own name prominently in red, white, and blue. Trump often made late night trips back to New York during the Presidential campaign, to sleep in his own living quarters, according to the New York Times. (The cost of outfitting his plane in suitable luxury may have given Trump grounds to criticize current government contracts with Boeing for the real Air Force One of $4 billion–“Cancel the order!“–although the mechanics of what was entailed in that plane were probably not in his grasp.)

All those daily flights home on “Trump Force One” to sleep in Trump Tower during the Iowa Caucuses were at first feared to cost him some votes across the midwest. Trump had regularly returned to his morning view of Central Park and his lavish home quarters, however, and seemed to relish returning with regularity during the campaign. He didn’t allow any press members to accompany him on these flights, though the staff grew. But he didn’t hesitate to outfit the luxury jet which was a frequent backdrop for news conferences and televised appearances, at a cost of an extra cost within the 3.8 million taxpayers payed to Tag Air, Inc., to operate the jet which approximated his personal quarters in Trump Tower, from a master bedroom approximated with silk wall coverings, mohair couch that converts to a bed, 57-inch television, home theater, shower and gold-plated toilet on this fuel-inefficient plane–all the while insisting on returning to his penthouse in Trump Tower almost each and every night. (Trump claimed his flights were funded by checks he wrote to his own campaign, and the sale of MAGA hats and souvenirs at rallies, but the $27,000-$36,000 increase in daily operating costs of such regular flights home–the result of a deep resistance to overnighting outside his home long noted on the campaign trail–left the Secret Service sending a tidy check of $1.6 million for much of 2016 to Trump’s own airplane company.)

6. The web of financial ties to Trump are far-flung in their nodes, and their ties to members of the incoming Trump cabinet–including Betsy “Ah, Betsy; Education, Right?” DeVos–and seem to stretch to areas only begging to be fully mapped, but which extend far, far beyond the properties of the Trump Organization.

–in a virtual web of business connections, many concealed within his tax statements. The ties to much of the nation and newfound legitimacy and recognition of the Trump brand seems undeniable–even if Donald Trump, Jr. dismissed the idea that Donald, now that “he’s got real stuff he’s got to deal with” and “real people’s lives,” is anything but occupied with his governmental duties or realizes the extent to which hid new platform of recognition might encourage the expansion of a luxury hotel chain to new regions of the country. While scoffing at the “notion that [President Trump] is still running the business from the White House is just insane,” however, the network of hotel chains he has administered provide something like the template for Trump’s notion of his relation to space, as the deals he brokered with construction firms, cities, and property taxes have provided him with the basic tools by which he seems destined to project Presidential authority. Even as Trump sons Eric and Donald, Jr., the surrogates of his hotel empire, claim “There are lines that we would never cross, and that’s mixing business with anything government,” the inescapable confusion is one from which they will benefit.

Indeed, the range of hotel properties Trump owns are wide-ranging, although notably removed form the African continent or Australia, not to mention an almost entire absence in Asia, restricting interest in South America to the tourist destination of Rio and a planned residential development in Uruguay; and with no properties in continental Europe outside Istanbul–and an avoidance of Mexico which, for the owner of a chain of luxury hotels and hotelier, seems almost to be rooted in something like a deep personal dislike–

The selective seats of Trump International perhaps befits an entity long styled as “real estate super-brand” and linked to the lifestyle it marketed. But the absence of Trump’s ability to market the Trump lifestyle and brand of hotel destinations in Europe, save the recent and requisite golf courses in Scotland Ireland, may reveal a long ambivalent attitude to Europe and NATO countries, given the absence of Trump interests outside golf courses in Aberdeen, Tunberry and Doonbeg. (Indeed, Trump took no time after assuming the Presidency to rail against the EU based on his own experiences from “another world” of business–based on the firm refusal of the EU to resist a proposed seawall on the dunes of Trump International Golf Links and Hotel in Doonbeg, Ireland, on the grounds of the environmental protection for endangered animals. Trump was forced to curtail his planned seawall, the basis for the objection–an endangered snail–post-dates his aversion to expanding Trump International in Europe.

But is emblematic of the disproportionate scale with which Trump seems to view the world. While mocking local disturbances faced by his building projects as annoying disturbances, he promotes his vision of a single way of life cobbled together from historical periods, providing residents a view from Mumbai at the Park at a remove from the poverty of homeless families who sleep on cardboard on Mumbai’s streets–in an image long suspected to be photoshopped.

The withdrawal of Trump Tower is the opposite of global engagement, but is the site to which Trump seems to invite us all to retreat in an age of global refugees. Is it any coincidence that the self-confessed germaphobe so fearful of contamination from crowds is most inclined to adopt metaphors as floods, swarms, or infectious to describe the experience of refugees as threats to the social body, metaphorically re-framing their plight at a remove from social, politics or economics–and insisting on our need for better self-protection? The distorted view from Trump Towers elides the experience of many through the distorting lens of real estate.

7. Indeed, Trump’s gift for getting his name put on every empty surface known to man–including Trump-themed fiction–seems to have been taken as an excuse for his interest in political representation, which it is not. But it is no secret that business interactions have most importantly shaped and helped formed Trump’s world view. And the somewhat striking absence of Trump hotels in much of Eurasia–save residential developments in Seoul, and some under construction in Mumbai, Pune and the Philippines–raises questions not only of the appeal of the version of Trump glitz that they offer, but also of the place of these actual locations in Trump’s current mental map; the distance of the Trump brand entirely from the neighboring state of Mexico is more than clear, and may derive from personal distaste.

The presence of properties under construction in Uruguay, India, and Makati may indicate constraints of the Trump lifestyle, whose limited truck in Europe is not destined to grow in the future. The relative absence of Trump’s presence in Asia–save Baku–suggests not only a compromised notion of geography for Trump, but an untimely withdrawal from international markets that analyses of the previous administration suggested place millions of jobs at risk. How can we collectively trust a man with so compromised a notion of geography to can the Trans-Pacific Partnership? The punitive measures proposed to be taken against companies making products overseas suggest a deeply skewed notion of the place of the American workplace in the global economy, and punitive measures against foreign competitors, suggest a limited and deeply narcissistic notion of global economic transactions, distant from and out of touch with the distribution of global populations.

The remove of a spatial imaginary of real estate was long prominent in Trump’s mind. The sharply concentrated and geographically small circuit of properties Trump owns in New York suggests not only a limited knowledge of the huge diversity of New York City but define the notion of the Trump lifestyle he has sold to America as an outer borough boy. It betrays his narrow range of interest in coveted properties around Midtown and Trump Tower, revealing Trump’s longstanding interest in focussing his sights on Manhattan, despite his father Fred’s disinterest in the far fancier borough–and his open discouragement to Donald for chasing such properties from a firm that had roots from the Verrazano Bridge to the Long Island border, and offered middle-class housing, for hubris in reaching beyond his Brooklyn roots. Is the focussed expansion of Trump Properties into Midtown, by now long naturalized by its epicenter at Trump Tower, a form of inter-borough envy with roots in the class conflicts of New York City’s urban geography?

Such inter-borough rivalry seem to have guided not only the expansion of Trump properties as it expanded to the area around the future Trump Tower, site of the tony area of Tiffany’s, the Plaza Hotel and Central Park South–

–but the position in which he sees himself in relation to the world, and the caricature of the populist millionaire that became the conceit of The Apprentice and since become a basis for Trump to sell himself and his brand to the country.

Indeed, the eagerness of Donald to move to the toniest areas Fred Trump disdained, by casting himself from the “streetwise son of Brooklyn’s largest apartment builder,” allowed him to expand his stylized image as a colossus of Manhattan, but to disdain the outer boroughs of New York City as a place to plant the gold-plated image of his name.

In staking claims to building in such a restricted area of Manhattan, Trump may have used midtown as a sort of arena or performance space to broadcast his identity with such well-polished sheen that it served as a launching pad for Reality TV, long before declaring his Presidency.

8. More scarily, however, is that the quite limited previous experience Trump gained with world affairs from his perch in New York seems destined to shape the judgements that he shapes on issues of global consequence: as being in Queens and looking at Manhattan defined Donald’s appreciation and interest in power, the very tactics of aggression that worked for him to launch his brand in New York has become generalized in the trademark launching of hotel facades, and the confrontational bullying of world leaders seems to be the chosen metier of foreign policy, as cultivating allies and personal rapports; divisions between personal space and national destiny seem far closer than in the past, who seems to see foreign policy as conducted in confidence and in tête-a-tête rapports; foreign non-immigrant workers of HB-1 visas are viewed as “cut-rate” bargains, analogous to foreign construction workers; constant commentary on foreign affairs in Twitter permitted; brinksmanship is a working strategy; market negotiations as a primary means of statecraft with overseas partners and adversaries alike.

Trump’s deep need to impress world leaders takes precedence over policy or statements of national interest; tax-cuts are for corporations, whose rate is cut to 15 percent, and tax brackets collapsed from seven to three–while omitting how the US government would be able to afford the cuts. Trump works on small-scale corporate deals with companies about aircraft, but the big picture seems to slip away.

For Trump’s apparently unremitting focus on staking claims to what he considered higher status in New York City’s real estate market, and to promote his name in doing so, developed with an intensity that led him to continue to stake claims to that status for new arenas. This began in New York City, greedily and relentlessly, from the West Side Highway where his promise of a waterfront apartment building led the city to permanently close an exit ramp, to Soho, to Wall Street. This apparent search seeming to chase an image of prestige in the mirror of his own gold-plated marquee, combining deep desire with disinterest in much of the external world, almost desiring only to look in the mirror of the gold reflective surfaces naming the multi-billion dollar towers to which the developer lends his name and the status they take pains to create. Trump indeed boasted to a biographer Harry Hurt III, back in 1993, about having the best living room view in all of New York City, by virtue of being able to see from his Trump Tower apartment his own name on all sides: beside the Hudson River in the West Side Yards; on Third Avenue, atop the thirty-nine story Trump Plaza or the fifty-five story Trump Palace. Hurt compared it all to a child-like fantasy: mirrored in miniature on the ultimate stage of self-indulgent fantasy, as Trump’s name is branded not only on buildings but also “on a Monopoly-tyle board game branded ‘Trump'”, in a sort of ubiquity that needs its own constant affirmation, and itself engenders a desperate need for confirmation of loyalty and admiration.

For Trump seems to have lived in an extended or protracted mirror stage, where the materials of building provide themselves the foil for revealing the “I” that the builder seeks to cultivate, forged in a pre-linguistic stage but continuing as a distorting monumentalization of selfhood that desires to obscure if not obliterates the very map across which it spreads, disorienting the viewer. The reality of the Trump presidency seems retaining the sheen on the name that seems to gain a greater aura the more that it is reproduced.

But how long can that last? While Trump boasted that his ability to have “added show business to the real estate business” is an apt characterization as “a positive for my properties and in my life,” is the nation able to be defined as his property, or is he able to fulfill the fantasies of his constituents through inflated promises and empty patina?

Rather than build such bold pronouncements of self without oversight in Washington, DC, Trump seems to offer the nation new ideas of the landscape of governmental authority. For rather than seeing the role of the Presidency as representing the nation, Trump seems to have relentlessly presented the function of the Presidency as expanding own his personal enrichment at the cost of the nation–and indeed at the cost of the Presidency’s historical prestige.