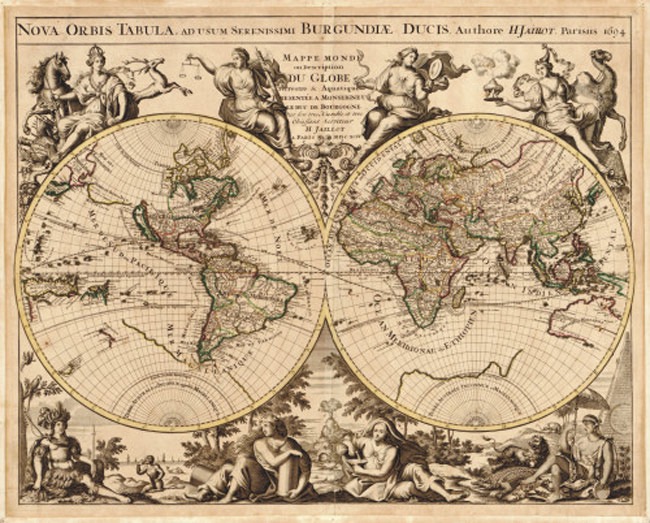

The medium of single-line engraving provided an expressive medium for organizing the continuity synthetic maps of land and sea long before trans-Atlantic travel was available to most. Mapping beyond one’s place or region is a specific area of expertise; it is not surprising that it is a difficult competency to define. It’s long been observed that the manner in which engraving produced an exactly replicable visual statement brought a variety of levels of expertise to bear on the map, both as a repository of collective visual memory and a coherent visual statement designed to orient readers to the notion of a uniform space. But it’s interesting to consider the local differences in how a coextensive notion of space was understood to be composed of mapping the integration of land and sea: and the understanding of the political power of the Serenissima–and the authority of the Venetian senate–as extending “onto the salted waters [sopra le acque salse]”–suggested a unique model of imagining worldly rule that uniquely inflected the construction of a cartographical space.

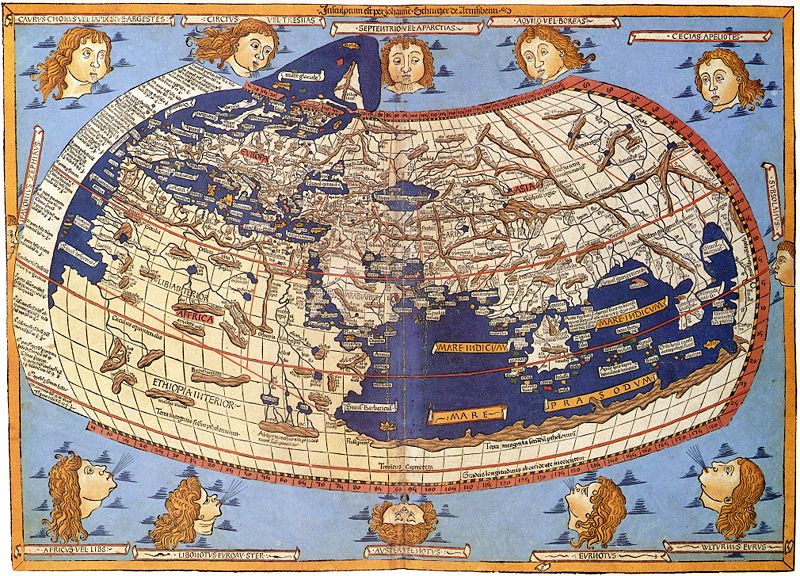

The transmission of the concept of a map of uniform coverage–one first expressed by the second-century Greek astrologer and mathematician Claudios Ptolemaios [Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος], bequeathed to us as simply Ptolemy, provided a template to illustrate the expanded edges of the inhabited world in the editions successively translated in early modern Europe considerably before maps of land were fully integrated with maps of sea. Translation of the forms by which Ptolemy mapped an inhabited terrestrial expanse not only to superseded the inhabited world as Ptolemy had described it and imagined it, but broached a different model of continuity within visual form: epistemologically distinct spaces of travel that corresponded to different forms of mapping were joined in a Ptolemaic planisphere, as were the distinct competencies of mapping, in what might be profitably examined and studied as a ‘trading zone’ of varied forms of technical skill. In Venice, perhaps, more than in other sites, the city offered a site connected by sea to other regions, and was a bit of an active trading zone of linking maps of water and land as Ptolemaic maps attempted, less constrained by territorial bounds, and more attentive to unifying the different metrics and scales of global mapping than many other engravers of global maps.

The image of the Venetian ties to the Mediterranean world and Gulf of Venice were rearticulated in maps, ordering a relation to a global expanse by nautical charts that had enjoyed broad currency in the city, and provided a cosmographic authority to articulate Ptolemy’s authority as a description of a terraqueous expanse.

1. Mapping Land and Sea

Techniques of artistic engraving offered a matrix in which to synthesize mapping forms from the fifteenth century, and the medium increased a synthesis of formats of mapping, as well as a the demand for maps as reproducable forms. As much as benefiting from Ivins’ useful characterization of the innovative ways that print afforded “exactly reproducable graphic statement,” engravers’ skills provided a way to transmit the map as a graphic form.

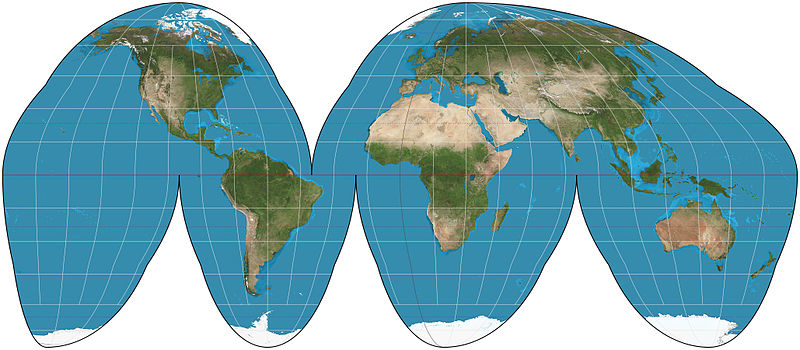

The Dutch engraver and cartographer Mercator in 1569 described his map as a synthesis of geographical maps and nautical charts: in so doing, he modernized the projection of the map’s surface as a continuous surface. In a unique and inventive way, Mercator assembled a record of terraqueous expanse on parallels and meridians to address a large audience of readers by boasting of his ability to bridge the distinct media of nautical charts of the ocean with geographic maps–whereas the Ortelian “Typus Orbis Terrarum” of 1570 directly below displayed traveling ships, riverine networks, and maritime expanse on curved meridians, Mercator’s projection distributes an inhabited expanse on perpendicularly intersecting meridians and parallels. But both maps advance cartographical expertise as preparing a surface that could be uniformly scanned by viewers as a proportional and uniform distribution of the inhabited world.

Mercator did not explain the mathematics of a uniformly mapped space. But the unique projection he devised gained broad authority by the seventeenth century as a means to visualize global relations. Although the Mercator projection ensured that the loxodromic lines of nautical travel, denoted in charts by rhumb lines, would perfectly intersect with meridians, the straight parallels construed “ad Usum Navigantium Emandate Accomodate” was not adopted for sailing or for plotting voyages until the ability to measure longitude at sea–partly since he did not explain his method for calculating the “true course” on straight lines, but also since the media of terrestrial maps were so distinct from nautical or navigational carts. But the combination of registers for noting nautical and terrestrial space, or imagining expanse on ship and on land, provided a major shift in maps’ graphic design and epistemological claims.

The gradual supersession of the autonomy of sea-charts facilitated increased claims of realistic representation–or reality effect of mapping land and sea in a continuous frame of reference. The combination of geographic and nautical charts to record of the known world in ways shifted how the world is known depended on acceptance of the descriptive potential of maps, as much as their accuracy or the use-value they gained to navigate in an era when calculation of latitude at sea depended on the sighting the altitude of the sun above the horizon and due course rarely achieved. But the Mercator projection integrates land charts and marine charts to provide totality of global expanse. This was the first age of globalism, and it could be readily understood. The cognitive basis of maps as vehicles seems concealed in Cornelius de Jode’s presentation of Mercator’s projection as a “Totius orbis cogniti Universalis descriptio” or record of the known world in 1589, a decade after its appearance: it offered tools for knowing the inhabited world as well as a record of the known world.

A similar visibility of the world’s surface was advanced in Cornelius de Jode’s later compendium of global coverage, which synthesized the conventions of nautical charts with the conventions of terrestrial mapping to create a convincing understanding of relationships between nautical travel and terrestrial expanse.

Such supersession of the conventions of mapping had to an extent previously occurred in the combination of results from different mapping formats in a unified cartographical space. Yet even before Mercator devised this projection, sixteenth-century maps had synthesized the content nautical maps had increased the claims of realistic representation–or reality effect–in printed maps. The graphic and pictorial detail and abundance of signifiers that was invested in Ptolemaic projections had increasingly shifted the status of the map from a schematic register which lay at remove of one from space, to a compelling synthesis of terrestrial relations for its viewer: and the map became a surrogate able to stand in metonymic relation to a place it described, stood at the center of modern claims of maps as forms of visual relation to space that could be inscribed with meaning. Indeed, the combination of registers of terrestrial and nautical cartography compellingly joined areas of practice that had been kept previously separate formats of spatial descriptions, if not incommensurable registers of qualitatively different registers to chart spatial continuity.

Was this change in attitudes to the map partly enabled by the combination of registers of terrestrial and nautical cartography? From previously separate formats of spatial descriptions, if not more significantly incommensurable registers of qualitatively different forms of space, the map’s surface became understood as a way to register motion through a uniform space and encounter places on a determined path of travel. The use and status of the map as both a register and descriptor of expanse was already evident in the integration of nautical charts and Ptolemaic maps Bernardus Sylvanus designed in Venice after 1508, which, despite the notorious absence of coverage of North America and reduced coverage of the globe, had previously described a terraqueous unity in compelling–and readable–ways by explicitly combining what had been seen as incommensurable orders of registering expanse.

The legibility of the 1511 projection of Sylvanus was both very contingent and local in nature, despite the universalizing viewpoint it prepared of the inhabited world. When Sylvanus, hailing from Eboli, possibly also an illuminator of erudite texts, undertook a newly illustrated printed edition of the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemy’s Guide to World-Mapping, known in the Renaissance simply as the Geography, he decided to create a more updated edition of comparative maps deriving from nautical charts collated by sailors and the set of maps transmitted in codices of the Ptolemy’s work of global geography. The plans for a new Venetian edition had recently been abandoned, although several plates for it had been made and perhaps engraved by 1508, probably including a new world projection. In confronting problems of modernizing the Ptolemaic maps, Sylvanus foregrounded the integration of islands and coastlines compiled in nautical charts in the maps transmitted in Ptolemy’s geographical treatise, translating the conventions for land-mapping into representational conventions from the graphic arts and advances of two-color typography: the birds perched on the cornices of his map of Italy, the sixth plate of Europe, may echo the modern bird’s-eye view of the peninsula he offered, using nautical maps to present the configuration with a sense of naturalism often foreign to early printed Ptolemaic maps.

2. Oceanic Space

The treatise that the second-century geographer titled a “handbook for drawing world maps” was both a technical guide and a compendium for drafting land maps. But in Venice, a city of maritime trade, Ptolemy’s promise to collate and list a database of all the places in the inhabited world’s surface had potential appeal as incommensurate with the chart used to decide or compare nautical routes of travel, and posed a specific challenge to synthesize mapping forms.

These charts provided an alternate source of information that promised both to refine and expand the ancient geographer’s encyclopedic claims that led him to list names of ancient cities and noteworthy cities or rivers exceeding 10,000 in number–if the richness of Ptolemy’s text led erudite readers to consult his book with their manuscripts of Herodotus or Livy, as Bernardo Machiavelli–father of Niccolò–their elegant terrestrial maps they more often addressed learned readers and armchair travelers as surfaces often read in relation to other ancient texts, rather than graphic descriptions of expanse. Indeed, their printers did not aim to address a larger audience of readers. Yet even when presenting accurate place-locations in coastlines that resemble charts, the maps struggled to offer an easily readable surface.

The synthesis of a more legible cartographical space was foreign to earlier cartographical traditions. The history of the transmission of medieval maps is considerably complex–as are the techniques of varied forms of map making. Elizabeth Edson argued information from accounts of travelers, traders, and sailors became accomodated in world-maps from the early fifteenth century, joining travelogues that both expanded the content and challenged the parameters of earlier symbolic world maps. The inclusion of information from travel accounts and nautical charts not only expanded the surface of maps, but posed complex problems of integration on parallels and meridians–a reproducible grid–and elicited potential graphic models for spatial representation over a century after its textual translation that lent formal authority to the world map.

The alternatives for such a synthesis were not clear. The considerable questions that surround the transmission and construction of earlier manuscript charts, often drawn on sheepskin to guarantee their preservation and illustrate their value, are raised by the unclear relations between how the maps were transmitted and copied–if not created–given the unclear questions about copyists reliance on the intersecting directional lines that seemed sketched over their content in tracing coastal shorelines and locating islands, or how the skein of lines apparently determined from compass-bearings provided guides for nautical travel. These maps were produced predominantly in port towns, as this Mediterranean chart executed in Alexandria by Jehuda Abenzara (or ben Zara), coastlines are crowded by names of coastal ports written perpendicularly to the shore, linked by a network or web of potential sea-routes that demand close reading and intense preparation by specially trained scribes:

In port cities like Alexandria, chart-makers regularly synthesized and collated a sort of collective memory of varied routes of travel that might be on board any arriving ship, in the hope of piecing together these local records of coasts or island-charts to synthesize more expansive networks of trade with a degree of accuracy that minimized cartographical distortion with a precision that geodetic observations had not allowed.

The chart synthesized a form of collective memory, if the protocols by which its contents were transmitted are not clear: the organization of a synthetic record of travels provided little more than symbolic reference to inhabited interiors, however, which in essence remained “off the map.” Rather than a representation of terrestrial space, it primarily provided a record of the location of ports and idealized potential lines of nautical–rather than terrestrial– travel.

The spatial mapping of coastal cities in the Mediterranean, and situation of coastlines in a broad nautical expanse–both in relation to both equinoctial lines and vertical bars of latitude however provided an alternate orientation to the network of the web of loxodromic lines of the compass rose. The below schematic version of a portolan chart, signed by Juan de la Cosa of c. 1500, provided a distinct frame of reference and spatial indices to enumerate points of landing and prominent capes in the New World at different latitudes for its readers.

The parchment portolan chart stored in Madrid’s Museo Naval and made in the port city of Andalusia, Puerto de Santa María, was prepared for competencies of a restricted audience, with specific interpretive tools in mind–whether they were kept by captains, or by trading houses is unclear, as is the primary techniques they use to demonstrate relations of space. By the fifteenth century, elegantly decorated versions became prized possessions among even landlocked elites–probably in copies that obscured or hid their own mercantile provenance and were designed to stake boundary lines of exploration or colonization in the New World, by demonstrating the boundary line of Tordesillas. But although the competencies of mapping these documents enlist to render expanse are opaque, their synthetic construction have provoked continued investigation of their formal manipulation or symbolic construction of mapped space.

Some of the relevant underlying schema of the networks and constellations in charts have been identified, but their operative value is not known–were they of use for copyists in Salamanca, Barcelona, or Genoa, or were these keys that allowed them to be read? The construction of scale lay in the relation among focal circles, wind roses, and loxodromic lines, as in this reading of the Cantino Chart.

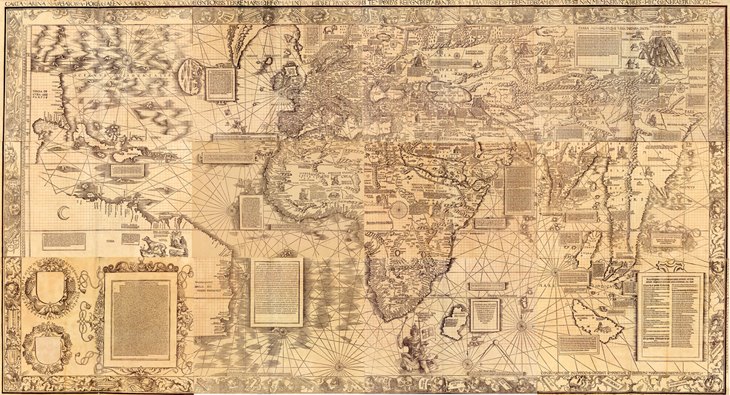

Spatial position is not much of an apparent interest, however, so much as the collation of alternative networks of travel–or, in the case of some charts presented by the Spanish or Portuguese, to illustrate the meridian that demarcated colonization of the New World at the Treaty of Tordesillas. The image of nautical continuity was a huge attraction for the humanist geographer Martin Waldseemüller, but his 1516 “Carta Marina” based on Portuguese marine charts like the so-called Cantino chart constituted part of his broader cosmographical project, but this image, discovered only by the Jesuit Josef Fischer around 1901, constituted an alternate model of cosmographical learning to his large world map of 1507, 4.5 to 8 feet, provided a wall-map whose comprehensive character was less successful in making claims for its legibility, if it invested greater artistic skills in converting the format of nautical charting to a legible form that Waldeseemüller had the projection engraved in the same dimensions. This map printed on high-quality hand-made rag paper was only found in one sixteenth-century bound volume, but was a complicated investment, even more so than the cosmographical map that Waldseemüller described as having been printed in 1,000 copies.

Somewhat oddly, the map did not include the image of “America” surrounded by oceanic waters that distinguished the lavish cosmographic wall-map he had printed in 1507, and whose accompanying treatise described America as “an island . . . surrounded on all sides by sea,” in his Cosmographiae Introductio—most probably because its sheets reflected the content of sea-charts–even if it superimposed an equi-angular grid that had little relation to the graticule employed in the terrestrial wall-map he had titled a Universalis Cosmographia.

The two large wall-maps produced at the University of Vosges, then in the Holy Roman Empire, both only recently acquired and restored by the Library of Congress, enshrined opposed if incommensurable models of world-geography at the very time Sylvanus prepared his own edition of Ptolemy’s precepts of geographic map-making and study of global geography. Did the lavishly produced “Carta Marina” offer a counterpart to the geographic theorization of expanse that Waldseemüller had advanced in his cosmographical writings? The ordering of Venice’s position in relation to a gulf, and to the expansive genre of island books or isolari printed in Venice and in Italy, provided a new way of describing Venice’s position in the world, and global continuity at a relatively early age.

3. Envisioning the Continuity of Terrestrial Geography

The location of geographical in the continuous coastlines of manuscript nautical charts was hastened by a demand to process the over 12000 identified sites Ptolemy specified as able to be mapped in a format which conformed to viewers’ expectations for representing spatial continuity. And Sylvanus seems to confront this difference shift in collating nautical charts with other mapping forms in Venice around 1510, in what seems a uniquely local manner to read a map’s universal claims.

The detailed coverage of the world’s surface in sixteenth-century Europe increased not only the coverage or precision of maps, I would argue, so much as the claims of realistic representation–or reality effect–of maps in critical ways. Yet changing understanding of the map as a medium, as well, provided Bernardus Sylvanus with grist to collate nautical charts in a set of new conventions that created a uniformity among data of diverse provenance previously regarded as qualitatively distinct if not incommensurable orders of spatial description. Although his exacting transposition of ancient names into modern outlines of land-masses ran against the critical project of comparing the ancient and modern worlds, the uniform conventions of maps he made presented a distinctly uniform continuous surface in images from charts.

For charts were less concerned with describing or denoting spatial location, than determining (and collating) potential routes of travel: the conceptual mapping of routes of travel was rarely invested with descriptive force or value; its competency reflected applied knowledge. The growing authority of the terrestrial map as a comprehensive description, however–one of the deepest of modern claims of maps as competencies rooted in visual design, rather than nautical knowledge–arose from the combination of registers of terrestrial and nautical cartography, previously separate formats of spatial descriptions if not more significantly incommensurable registers, in a sort of a trading zones of semiotic conventions from varied areas of life, which bridged or linked hitherto incommensurable formats to denote expanse.

As the rich spatial information contained within the medium of the chart was transposed to the surface of terrestrial maps, something like a wrestling with epistemological claims for knowing space and locations seems apparent in the maps included in treatises of global geography first translated in the fifteenth-century, most particularly in Claudius Ptolemy’s second-century Guide for Drawing Terrestrial Maps, whose maps Renaissance editors of the treatise had increasingly invested with increasingly comprehensive ends–increasingly relying on the toponymically crowded but crisply defined coastlines transmitted in charts to blend seamlessly with inland areas. The accumulation of local and pictorial detail to combine an over-abundance of signifiers altered the distinction between the land map and nautical chart, raising truth-value claims about the chart as a representation that stood at remove of one from the world that this post can only begin to suggest: increasingly, the map became a place that could be inscribed with meaning, or became a register from which to relate to foreign lands, if not a substitute for them. The diminishing authority of the chart lay partly in a limited ability to determine position at sea, but also a limitation of the ability for encoding further information in its content that would satisfy its audience. Edward Wright observed the errors of sea-charts as a basis for calculating position in 1599:

A word or two about this complex treatise, abundantly overflowing with strange toponyms that elicited readers’ curiosity even if its content were difficult to translate into the standards of eloquent expression to which many of its humanist readers were habituated–leading some to indicate Strabo as–to quote Isaac Casaubon–the “summo scriptore, quod praeter acuratissimam totius orbis nunc cogniti descriptionem, tanta doctrina, tamque varia omnium rerum scientia refertum est, ea denique arte contextum . . .“

Ptolemy’s expansive catalogue of locations had long demanded to be given a visual form. The question of their visual coherence led some of his later editors to rely on nautical charts that included places Ptolemy had not indicated, but the nautical chart provided little analogous framework of coherence by which to grasp their situation in a continuous expanse. The geographer Angeliki Tsorlini has recently employed digital technologies to map relative locations defined by the terrestrial coordinates in Ptolemy’s treatise in ways that reveal the very compelling map of Mediterranean cities his treatise would have offered. Most of the cities are ports, located along the shore, to be sure, but a considerable number remain inland cities located with apparent relative precision, with minimal significant distortion for much of Italy, the Adriatic, and Greece. The copious abundance of familiar locations and interest in their clustering must have increased demand for their depiction.

In the first codex that arrived in Rome, found by Maximous Planudes in the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century, the abstract ordering of the situation and topography did not pose an intellectual problem of viewing space (Burney 111; British Library). Despite the formal appearance of the island of Taprobana, thought to perhaps represent Sri Lanka, the red lines of parallels of latitudes and meridians of longitude in which Ptolemy argued geographic mapmakers could usefully divide the world for readers on measured units, provided limited claims to mediate a naturalistic image of expanse.

Planoudes was careful to note the precise location of places on spatial coordinates, but the metric values of locations were not presented as lying in exact correspondence to their spatial situation. The illustration of cartographical images that expanded later codices of Ptolemy’s treatise worked hard to provide maps that were commensurate with the over 1200 place-names–including mouths of rivers, promontories, mountains, or landmarks–contained in his geographic compendia were sought to be illustrated in authoritative form.

As the work reached a large audience in manuscript, terrestrial space was presented in schematic terms, the maps seem to wrestle with the abstraction of space, as if in ways that could not be imagined in visual or pictorial terms as a surface that could be scanned, as is evident in this map of German lands in one codex of the Geography, which enumerated towns and rivers in a new abstract form, listing inhabitants and towns as in the Ptolemaic manner, with minimal recognizable guides or explicit orientational clues about their spatial situation and topographical location, even when that region lay on the margins of the Roman world:

Yet the land-locked nature of these regions made the legibility of expanse less concrete.

Even in areas that claimed continuity with the ancient world, the production of Ptolemaic treatises curiously included modern views of Mediterranean cities in several deluxe of codices illuminated in Florence, as if to expand the treatise’s qualitative coverage of European cities in a rhetorically persuasive image for readers–these images had less regard for the systematic terrestrial coordinates Ptolemy proscribed than for preserving noteworthy sites in each place, or offer a ‘chorographic’ complement to Ptolemy’s explicitly geographic concern.

4. Symbolic Syntheses of Mapped Space

The question of what sort of graphic synthesis was provided in a geographic map is broadly tied to Renaissance visual culture, but posed particularly pressing questions in port cities that compared Ptolemy’s precepts with maps of nautical expanse. Bernardus Sylvanus assembled engraved maps for his edition of Ptolemy shortly after the plans to print an edition of the treatise in Venice collapsed or failed, for reasons of skill or financing. But a huge shift occurred in the production of maps that made such authoritative regional claims as depictions had already occurred, reflected in the preponderance of their incision, illumination, and distribution in centers of visual cultures in northern and central Italy, central Germany, and the Netherlands: the specific forms of overlap between nautical and terrestrial methods in sites from Venice to Rome to Nuremberg created a rich repertory of maps with expansive truth-claims as forms of depiction. His work came on the heals of an existing experimentation with combining cartographical registers of description in a universal register of mapping habitations of terrestrial space, evident in the 1507-8 world map of the Roman edition of Ptolemy, designed by the northern engraver Johannes Ruysch, and contemporary to the plans for a Venetian edition of Ptolemy’s treatise.

The manner that this 1507 world map mediated the legibility terraqueous expanse as a continuous surface might have offered a model for Sylvanus’ integrating of mapping forms: for the Ruysch projection is in ways a restatement of cartographic expertise.

The black-and-white outlines of the copperplate incision helps foreground the legibility of toponyms and textual panels alike that lie on the map’s curved meridian lines, as the stippled surface of oceanic expanse suggests the fact of its comprehension in the map–a comprehension rendered evident to viewers by the unveiling of the new form of a circumnavigable Africa and India, as well as the introduction of the newly discovered capes, rivers, and islands of the Americas:

The historian of cartography David Woodward argued that cartographical competence reveals a growing “rationalization of space” around 1492. In ways, we have begun to remove cartography from a professional genealogy that places a premium on rationality–such a claim is concealed within the creative combination of forms of diverse sources mapmakers have long imaginatively integrated in synthetic designs. But the limitations on the ‘rationality’ of the map–or the grounding of its authority in its rationality–demands future research for how mapmakers who amplified the local qualitative content of cartographical media.

Taking a step further backward in time, we can perhaps appreciate how the designers and illuminators of maps of maps included in manuscripts of Ptolemy’s treatise seem ambivalent in their use of parallels and meridians as a framework for defining a cognitive relation to expanse or for recording a cognitive relation to place: for they treat the graticule of the map more as a frame of reference by which to register terrestrial position, than as an enabling format for graphic representation: the iconic portrayal of place in early maps as clusters of houses that positioned against the blank ‘space’ framed by coordinate system or patches of forest tries to bridge Ptolemy’s ancient model for denoting a uniform abstraction of terrestrial expanse on Euclidean precepts and the ability to transcribe space. Illuminators, few of whom are known, invested maps with very limited mimetic qualities from the 1450s and 1470s to communicate their continuity: the new interest in regional maps as registers lead illuminators to position clusters of houses with peaked roofs and taller towers in dense proximity to each other to distinguish areas of settlement, beside clustered areas of forest growth–as the Black Forest in Bavaria–that provided some vague reassurance of the correspondence of space. Some of the owners of such maps added places near their own residence, or areas that they knew, omitted in the printed editions or codices they owned, as if to give the maps an expressive value that they feel they lacked.

Did the second-century geographer’s “handbook for drawing world maps” have different implications in Venice, a city of maritime trade and considerable diversity, where nautical maps were more prevalent than maps of terrestrial expanse by the early sixteenth century?

4. Back to Bernardus Sylvanus in Venice, ca. 1500

The shift in Venetian culture for locating place in a map’s expanse is reflected in the collation of a set of independent views of neighborhoods to create a dramatic imagined synthetic view of

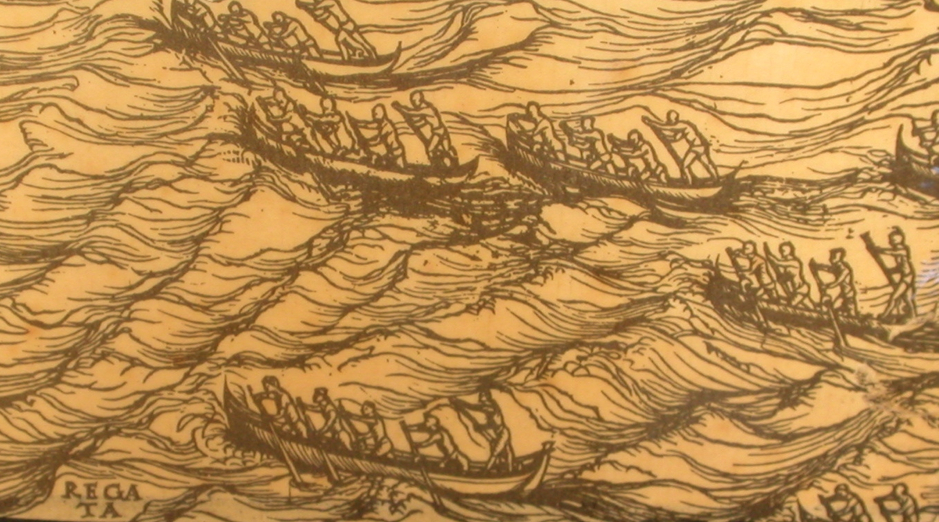

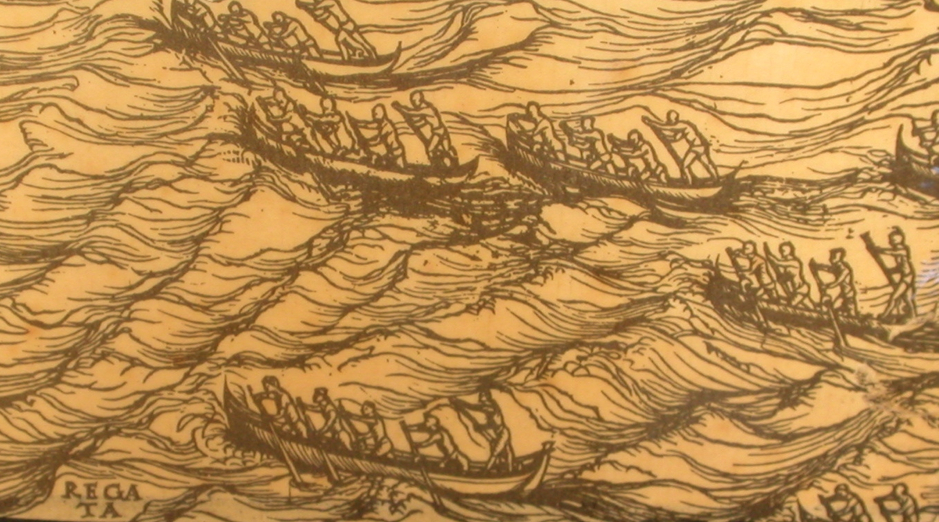

Venice as seen from above in a wall-map composed from six large individual woodblocks and large rag sheets. The master of perspective Jacopo de’ Barbari designed the detailed view by taking he city’s coasts a a frame in which to distribute its built and inhabited expanse: heads of winds of each direction frame the view, recalling the spokes of a wind-rose and the disembodied heads of

putti who surround most early printed Ptolemaic maps, magnify the city’s coastlines and maritime surroundings, revealing the complexity of its physical plant as if the city were something of a microcosm of the inhabited world, and to showcase the expansive position of Venice on the Adriatic. The view situates the “forma urbis” not only as a built space but in realtion to the surrounding sea, dotted with individual boats and a regatta: in the distance, one sees the Alps to the north: the city appears as a microcosm of global expanse, as the depiction of its inhabitation in each

rione of Venice stands as a graphic surrogate for the mapping of a miniature world.

The particular detailing of a sea as continuous with coastlines and inhabited world provides the informed viewer with something of a metaphor for the unity of land and sea in world-mapping, revealed in Jacopo’s attention to both wind-heads round the city and to a regatta that braves Adriatic winds, exploiting his attention to the finely engraved lines of the wavy waters:

What sort of view did Jacopo de’ Barbari compose in this elegant multi-sheet wall map? The view is often compared to the elevated “bird’s-eye” perspectival views of the “forma urbis” of Renaissance cities, but rests on a synthsesis of an imagiend or virtual view from individual surveys of the city: one recent digitization of the view of “Venetia 1500” helped reveal the synthetic unity Jacopo took pains to created a uniformity of urban space from individual surveys as an illustration of considerable skill of rendering an almost planimetric space for viewers to scan as a continuous surface that extended to the surrounding oceanic sea:

The multi-sheet map, whose production required three years, exemplifies a Venetian appreciation of elevating a record of collective perceptions by combining map-making and perspective with particular virtuosity.

Each of the six sheets provided detailed records of the city in what Fortini Brown has called an “eye-witness style,” but a imported mapping records to a continuous picture-frame that pushed the cartographic metaphor of transcription to transcend a single fixed perspective.

The luxury print of multiple sheets provide a surface into which the viewer can descend into specific neighborhoods or regions that are immediately recognizable: the continuity of its content were thematized in another recent digitization of the map created by the Correr Museum:

But the lines of the Venetian lagoon and Adriatic suggest the clearest inclusion of a sense of maritime space in the map–an illusion that was echoed in the corpus of Sylvanus maps. For Jacobo de’ Barbari created a model for viewing the coherence of urban space that responded to a challenge for ordering the unity of terrestrial and nautical space. When Bernardus Sylvanus intended to expand the cartographical corpus of Ptolemy’s Geography in Venice around 1508, he consciously and proudly incorporated information from the surface of sailors’ nautical charts into the land-maps denoted by spatial coordinates in earlier editions of Ptolemy’s treatise, creating a unified legible cartographical surface and using printer’s red to place cities in a continuous landscape–if often situating ancient names of place from Ptolemy’s work within the modern coastlines of nautical charts, in ways that went against the scholarly tradition of comparing ancient and modern geography by juxtaposing “ancient” and “modern” maps, but also advanced a single cartographic record as authoritative and unique, shading coastlines to suggest the maritime field in which he placed new nautical discoveries–and limited America, famously, to the Columban islands to the ahistorical exclusion of all North America.

Rather than enabling spatial travel, the world map of two sheets noted place-names in a distinctive printer’s red that stand out from rolling hills, framed by etched lines of waters on their coasts as if in imagined relief:

The map’s space was treated as a continuous surface, defined by the coastlines from modern nautical charts, if the toponomy was often ancient in origin, treating the cartographical surface as a uniform register of inhabited lands:

Little biographic information is known about the production of the maps of Bernardus Sylvanus da Ebola, though he has been possibly identified with an illuminator. But he clearly exploited, even more than his predecessors, the semiotic synthesis that print allowed in Venice. This is evident both in its combination of text and woodcut imagery in this two-sheet map, and the overlay of a graticule, equatorial bar, and wind-heads, combining conventions of different mapping media more explicitly than even earlier editions of the existing maps of the Ptolemaic corpus.

The introduction of islands and coastlines not in most all of the maps editors of the previous five printed editions of Ptolemy’s treatise on world-mapping (a sudden burst of editions which we can label Bologna 1477; Rome 1478; Ulm 1482; Berlinghieri 1482; and Rome 1507), presenting more clearly identified coasts and islands–as the ‘isole fortunate’ off of Africa’s western coast, although it omits the New World–but are often of limited geographic accuracy. The distinct use of type to balance the legibility of a map crowded with toponymy by two-color ink adopts the innovation of the material production of books to create a surface easily read by its customers–and he invited readers of the maps he organized as a comparison between the maps Ptolemy described and the versions corrected by modern nautical charts to “compare Ptolemy’s words with navigations themselves” and decide for themselves, using two-color printing to facilitate an intensive reading of the map’s surface, and in the attention that he gave to islands in the Mediterranean, as the Balearic islands off the coast of Spain, where the etching of lines suggest the surrounding seas that hit their rocky shores.

The significance of the line in the medium of engraving has been argued to facilitate the conventions of uniform mapping of terrestrial expanse, allowing engravers to exploit the geometric formats of Ptolemaic mapping in graphic form in particularly expressive ways, the expressive value of the Sylvanus maps derived from their synthesis of conventions of map-making in a continuously readable form–one that created new attentiveness, indeed, to the encryption of information from the surface of the map, both in the map of the world’s surface and the individual tables editors helped prepare for Ptolemy’s treatise.

This must have responded to an increase in what might be called geographic curiosity.

The universal coverage of the maps Sylvanus prepared for Ptolemy’s manual of global geography was constructed from a very local place, and reveals the local availability of island books or isolari in Venice, as well as nautical records of the Mediterranean and Adriatic that were available in abundance in the maritime city, which were carefully integrated within the system of parallels, meridians and equinoctial lines for readers to pour over, with attention to areas like Spain’s Mediterranean coast or Greek islands in the Adriatic, depicted by a similar accuracy reminiscent of charts, as are its inlets and bays.

Sylvanus illustrated the division between Africa and Asia, the origins of the Nile and shores of the newly-mapped Red Sea for readers to consult, probably in relation to available maps, by means of a similar etching of graphic relief:

The material surface of Bernardus’ maps synthesized a range of semiotic conventions that viewers would have been quick to recognize as a combination of a material landscape and a map: one of his Italian readers was quick to include images of the towns in the Marches in the map of Italy and the Adriatic, depicting both the towns of Monterubbiano and Moresco i in ways comparable to the iconic perspective views of cities.

The additions suggest a dramatic increased in the graphic materiality of the map as a pictorial register. Print are allowed men as Bernardus or fellow-engravers and editors of maps in Florence, Rome, and Antwerp to invest the map’s surface with new claims of legibility as a reproducible record. But it is also very possible that Bernardus’ sustained engagement with a project of printing he hoped would be far more successful derived from the prominent status maps already enjoyed in other visual media.

The interest of maps as depictions reflected a deep appropriation of Ptolemy’s instructions to his own second-century contemporaries to craft a map “ad oculorum aspectum commensurabilis“–the transmission of this precept to later mapmakers to create a surface that would appeal to their readers’ eyes, if not also the tacit presuppositions for viewing a continuous space in a detailed and harmonious form.

5. A tradition of fifteenth-century Venetian cartographers had incorporated nautical charts to illustrative or pictorial ends in inventive ways, in attempts to give greater expressivity and comprehensiveness to the Ptolemaic planisphere or nautical chart: a 1448 world map designed with great care by Giovanni Leardo framed by the months of the year and astrological signs (Verona, Bibl. Civ., Ms 3119); Fra Mauro’s famous circular map uniquely synthesized Portuguese charts, a unique matter given that it was in fact commissioned for Portugal’s monarch, without a graticule; it recalls an ellipsoid world map of 1457 constructed on the principles “of cosmographers” without a uniform graticule, and filled with textual legends, fanciful iconography, and perspective city views. None privileged the geometrical order of a uniformly continuous surface or a format of projection from terrestrial cartography, however, or bridged different semantic registers in the manner of Sylvanus’ maps.

The Ptolemaic model provided an authoritative basis to fashion a surface that could be readily scanned as a uniform distribution of expanse by around 1500, and in Venice shifted the attitudes of viewers to mapped space. By the later fifteenth century, the Venetian Senate had commissioned the repainting of territorial maps of the lagoon of Antonio de’ Leonardi from his nephew Sebastian along parallels and meridians by “Ptolemy’s doctrine” that Isabella d’Este and others Isabella d’Este sent painters to copy, marvelling at its proportions and scale. The painted map received praise as “così perfetta nelle sue misure [so elegant and well-proportioned]” that “diversi Principi [several princes]” had commissioned copies of it for their own enjoyment and pleasure before its 1577 destruction, Sansovino boasted among his catalogue of the city’s artistic treasures.[i]

Although the map is now destroyed, and cannot be pictured, it constituted something of a model for the multiple maps now present in the Palazzo Ducale, painted to replace it, and for the maps of the Veneto that Christoforo da Sorte created in its private chambers–as well as, perhaps, Egnazio Danti’s monumental remapping of the peninsula in colored paint. The much-admired peninsular map may have provided a model for integrating the format of nautical charts with maps of geographic content by men like Sebastian Cabot, piloto for the Casa de la Contratacion in Seville who created a new world map–or the map-engraver and engineer Giacomo Gastaldi, who from 1546 synthesized multiple elegant wall-maps that refined cartographical expertise; Gastaldi’s work with the geographer Giovan Battista Ramusio led him to design comprehensively detailed pictorial wall-maps as that of South-East Asia.

But we might also start from the 1511 modern map of the peninsula that Sylvanus designed:

Did this lost expansive painted map of the lagoon that extended to the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian sea, and their islands, provide a model for uniting terrestrial and nautical maps that men such as Bernardus Sylvanus sought to generalize for a larger audience in printed form? The reader of Sylvanus’ printed maps from Fermo sought to make the text his very own, adding his own qualitative views of the cities that he knew, in ways that register a distinct relation to the map as a continuous surface.

When the great cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli mapped the geographical situation of Venice in a broader gulf from the mid-seventeenth century, he described the place of Venice in the expanded gulf in his 1688 global atlas–placing Venice in relation across the Gulf of the Adriatic to the islands of its empire, which bordered on the expanding Ottoman by shifting boundaries, as if to affirm its own domain of the seas that opened along its shores.

As if overseeing an expanse that might be translated into varied scales, the dominion of Venice was defined across maritime expanse, not by territorial bounds, but in the cartouche from which the emblem of the lion of San Marco serenely oversaw its content. From the margins of the map, the winged lion that Coronelli cleverly located in the cartouche that looked over the expanse of the Gulf, overseeing the expanse from beneath its dogal crown, beneath six bars of scale of mapping that alligned each of five standards with maritime leagues.

[i] Gallo, “Le mappe geographiche del Palazzo Ducale di Venezia,” Archivio Veneto ser. V, 32 (1943): 47-54. Sansovino, Venetia, citta nobilissima et singolare (Venice: Iacomo Sansovino, 1581), fol. 122, “era una tavola d’Italia così perfetta nelle sue misure, che diversi Principi ne domandarono l’essemplare.”

University Library of Munich, ULM Cim. 107#2. Courtesy of University Library of Munich

University Library of Munich, ULM Cim. 107#2. Courtesy of University Library of Munich

Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia secundum Ptolomei Traditionem . . . . /

Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia secundum Ptolomei Traditionem . . . . /  Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia secundum Ptolomei Traditionem . . . . /

Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia secundum Ptolomei Traditionem . . . . /