In surveying artists’ maps at the recent symposium “Mapping and its Discontents,” Katherine Harmon celebrated how “creative cartographies” oriented viewers to a narrative about place. If most of the presentations made viewers re-think the nature of map making as an art and science, Harmon’s attention to how the art of mapping create narratives about place at the symposium sponsored by UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design suggest the inadequacy of separating “cartography” and “art” by examining the map as an art of orientation–by how maps invite viewers relate lived space to the space that they create. In a symposium that raised questions about the seductiveness of the ability of how better-defined datasets can make maps that better capture processes we want to describe, it was refreshing to shift focus to how cartographical arts register an individual relation to place. Indeed, if several papers in the symposium struggled over how to bridge map and narrative–do we need to depend less on maps? to be seduced less by its promises of truth?–each artist returns to the dialogic relation map instill between viewers by orienting viewers to their content in ways that pose questions about the lack of personal detail in an undifferentiated record of space.

In a sense, the survey of artists’ maps on which Harmon organized and explored exposed the artistic values in which all cartographical practices are embedded. But they also pointed up the narrative ends to which cartographical forms were so particularly suited as joint representations and explorations of space. All maps engage their readers’ appetite for knowing a place, and even revise it, by creating a relation–a “map”–between personal knowledge and the residue of collective knowledge distributed in the design of their surface. The narrative possibilities for registering personal knowledge of space are particularly inviting in such an ostensibly objective framework of geographical denotation: Harmon called attention to the particularly eloquent transformation or adaptation of how the framework of mapping offers both a compelling and legible text by the forms of “deep mapping” that technology now allows–and the expressive form for deeply personal narratives they offer even as they threaten to lose specific details in the very process of generalizing a record of a uniform space.

In an age where we are deluged by maps in all sectors of life, the tracing of these artistic strategies of mapping seems a recuperation of maps as orienting tools and arts of orientation, and this post surveys some of the maps that she presented, some known from other works, as serving to orient viewers in a practice of mapping that is often too removed or alienated from individual experience. For the ways that cartography can serve as a practice for engaging our different understandings of space in particularly inventive ways maps both feed cognitive by orienting viewers to place in revisionary (and potentially liberating) ways–by engaging viewers n how they uncover meanings about spaces one already thought one knew or believed to have been recorded in existing maps, by creating dialogue about spatial relations as much as to generalize a record of space.

Harmon’s presentation showed less interest in how to tell stories in a map than in using mapping to register personal familiarity with place, by orienting viewers to the multiple personal networks in a mapped social space. The “creative cartographies” recuperate the artistic basis of mapping as arts of individual and collective orientation that exploited the structure of synthesizing spatial knowledge in a combination of ways. The narratives each cartographer creatively located in maps exploit the innate curiosity maps invite by orienting viewers. Harmon distinguished the narratives that several maps create; the “creative cartographers” all draw connections between the specificity of individual narratives plotted in maps and their structural designs. If the “discontents” of mapping lay in the anonymity of the maps of public space that were universalized for their readers in many digitized mapping projects and by government planning agencies from Rio di Janiero to Beijing to Ho Chi Minh city to Zagreb to the Google Earth platform, creative cartographers exploit the inventiveness invitations of maps place oneself in space by the power of making meaningful cartographical spaces by balancing them with a personal reading of place.

Harmon invited the symposium to follow how creative maps buck the conceit of large data samples to inscribe maps with the personal meaning from a particular perspective–and in so doing, turn the abstracted nature of cartographical practice on its head, reminding us how such “scientific” practices are embedded in a discourse on the arts. Indeed, as they engaged scientific practices of cartography, they adopted the tools of mapping in as tools to chart a distinctively individual relation to a known space, rather than a universalized one–or, rather, they novelistically use the format of map-making to universalize the particular situated perception of space that maps rarely include or note.

Harmon emphasized in her own visually stunning and compelling presentation the narrative content in these creative maps as setting into space individual stories about space that pointedly contrast with the de-personalized map and emphasized their own personal knowledge. She showed a set of creative cartographies that exist in a dialogic relation to our own knowledge of a place, moreover, and, more deeply, out knowledge of objective–as well as subjective–renderings of it, making creative maps particularly neat ways of opening up new perspectives on a space that fence in interesting ways with our own. Indeed, maps have a unique power to illuminate the relation between our story and our surroundings, as much as to tell stories of their own about how we understand place.

The cognitive webs of connections that maps both embody and render visible and concrete have the effect of never seeing ourselves as isolated. They rather allow us to map our place in a set of other stories and narratives about place, in ways that are deeply social as well as rooted individual cognition. And perhaps the most problematic subject of mapping such an individual narrative–or restoring its centrality–is in as frequently a re-mappped event as the September 11 tragedy, whose multiple mapping has accreted more meaning on the event–as if it needed this injection–to erase its personal narratives, and imposed meanings on the event that have almost obliterated our memories of its occurrence, and our relation to its immense tragedy.

It is interesting how she began from 9/11–an event that illustrated the tyranny of the map in the public imagination, and a touchstone for how a local event effectively mapped a geopolitical relationship to the world, albeit a quite distorting one. The event is not only ripe for re-mapping, but demanded a resourcefulness in using mapping forms to forge new networks of meaning in an over-rehearsed geographic conceit. The artist Karin Shneider effectively re-mapped our cognitive understanding of events of 9/11–and the cognitive space of the twin towers–that re-framed memory of their destruction and the death of their unfortunate occupants in plate-glass maps inscribed with the commuter routes those who were tragically killed had taken on that morning as they arrived at work. The sounds of breaking plate-glass were inseparable for many observers of the twin towers’ collapse on September 11. In Shneider’s commemorative map, individualized etched glass plates restore both the fragility of their lives, and the integrity of each life that overlapped that day, providing a commemorative cognitive map of the event that viewers to consider how the event tied these lives together so tragically, tracing the routes each took to remind us of the voyages each performed that day. The set of maps commemorate the deaths of some 2,752 individuals by distilling the circumstances of their spatial intersection, giving specificity to that over-photographed and documented event by emphasizing their now unrecoverable perspectives with the evocation of personal letters or diary entries, so unlike the opacity we usually identify with maps, inviting us to see through their commutes to remember the loss of individual life. The map of approaches to a final intersection replaces the all too familiar rendering of collision courses of two airplanes on September 11.

Shneider’s composite of overlapping maps remind us of the very difficulty of recuperating individual narratives in such an over-narrated event–mapping the mess of lives that intersected fortuitously that morning, and which will no longer be with us. They reframe an event too often framed as a war on “terrorism,” “clash of civilizations,” or a sign of barbarity and civilization in distorting and exploitative ways, moreover, giving transparence to the very surface of the map. The absence of a one narrative that unites these paths is, indeed, a great part of the effectiveness of capturing such multiple individual itineraries within one map.

The decided lack of spatial narrative–but a snapshot summary of the lives that intersected on that day in early September–is evident in a quite different map that, oddly, interestingly emphasized the international origins of those who lost lives that day, perhaps in an attempt to remove its violence from a narrative of opposition, and disturbingly cast the loss of lives in terms of the quite different-order abstraction of individual nations:

That map’s argument is disquieting because of how it erases individuality.

Mapping can be a clarification of such tragedy, however. The far more delicate set of superimposed plate-glass maps Harmon described stands in contrast to the anonymity of this map, or the very disembodied and abstracted map of the routes that these hijacked planes took, by inscribing their paths at a complete remove from individual lives. Indeed, even the inscription of names of those killed in the event at the site itself on a granite plaque, evocative of the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, oddly strips them of individuality–unlike how the reflecting stone surface of the Vietnam War Memorial designed by Maya Lin invites viewers to touch individual names on its surface, as if to try to map abruptly curtailed lives.

The inscription of the names of the dead of 9/11, unlike Maya Lin’s monument, offers no attempt to embody the event–or to express the multiplicity of narratives that that event so tragically condensed.

At another extreme of mapping the 9/11 tragedy lies the grotesque dis-humanized blood-flecked map, so sensationally printed by the New York Post, allegedly based on a map fire-fighters compiled of human remains, as a broadside intended to vilify plans to construct a mosque nearby the site–a map so shockingly dispersive in its energies that rather than embodying the 2,752 deaths it seems to chart, aggressively alarms its viewer with an explosion of meaning impossible to process save by recoiling in horror from its tabulation of human remains near the scene of impact:

For if the violently voyeuristic map seeks to dignify the site’s sanctity by delineating the violent loss of life, its superfluity of meaning is something of a recapitulation of violence, attempting to shock the viewer as does the inset photography, by providing some access to the history of the event.

Scheider’s creative cartography also stands in eloquent counterpoint to the abstract cartography of that emptiest of maps, of PATH commuter routes, which she adopts as something of a basis to trace a palimpsest of commutes:

The problem of how maps evoke or shift a familiar narrative motivates the inventive ways itineraries are combined with maps to upend their abstraction, or the spatial oppositions that they create and reify. Daniel Zeller recuperated the itinerary as a unit of spatial knowledge in imagined maps linking two sites of worship in two different religions by imagining their proximity, and almost delineating an imagined route of pilgrimage that might link their footprints. Zeller used his deep study of topographic maps and satellite imagery to forge an imagined spatial tie between the Vatican and Masjid al-Haram, the mosque at Mecca, as if to bridge ties between two sites removed from one another in such popular and political discourse alike, by connecting them as if on an individual footpath. By tracing the footprint of each in graphite, and imagining a windy route of pilgrimage that might actually connect them in “Vatican/al Haram,” using the extreme precision to actively embody and create real spatial ties–

–with attentiveness to precision evident in this detail of the links he creatively mapped between both houses of worship.

Departing from digital simulations that often create information overload, Zeller’s craft-like remapping places with the symbolic continuity that maps create to all too improbably link two sites so often separately segregated in the global imagination.

Bridging divides through a pathway that itself unites or crosses cultures is the theme of Asma Ahmed Shikoh’s beautiful acrylic “Van Wyck Boulevard,” part of her project “Home.” Shikoh’s art maps her status as a Pakistani artist trained in Karachi who moved to New York: “Home” brilliantly reclaimed the craft traditions of mapping, recasting the NYC subway map as an Urdu manuscript and within a geometrical design borrowed from the Islamic Al Hambra, in Spain, to reexamine its functional status, and its role as an icon of urban belonging at the same time as mapping a Muslim diaspora–precisely by casting the map of the path of the MTA’s “F” line that took her to her first home in the city. Shikoh reconfigured the map in a painted form of distinct coloration, engaging its form as well as using language as a tool to assert my identity and make the new place my own.” The widely reproduced and iconic subway map served as a template to assert and recreate the familiar embodiment of the subway lines as a constellation of meaning invested with a narrative intent that the location of stations on this diagram rarely possesses: only by “transliterating every stop, was painstaking, repetitive, and yet therapeutic for a newcomer” that traced a narrative through a process of remapping and making the city her own– using the subway map to transcend the increasing construction of a dichotomous divide between East and West, and re-center her identity (and immigrant identity) in the mobile paths of New York City’s subways.

Cross-generational mobility was mapped through the shifting degrees of access or familiarity with space across generations in a map of the town of Sheffield, Harmon noted, when Dr. William Bird traced i the limits of known space created across generations living on an aerial view of the city that redefines the mapping of “city limits.” The chart of the boundaries of a “known world” where children were entitled to walk unaccompanied in Sheffield provides a far more general (and very poignant) map of a demographic group’s relation to space, investing the map with particular narrative and expressive properties beyond that of a spatial register.

“How Children Lost the Right to Roam in Four Generations“ (2007) employs the format of aerial photography to map the ambits at which children were allowed to walk on their own in the same neighborhood in one family. The result of comparing the increasingly restricted spaces parents tolerated wondering illustrates and documents the daramatic contraction of the consderable freedom eight year old George Thomas enjoyed in 1926 in Sheffield. His parents, not able to afford the tram’s fare, let him to walk six miles to fish on his own. The erosion of the English commons is a trope of the enclosures of the early nineteenth century, and the lack of urban exploration a more contemporary concern for city-dwellers who find their children less adventurous in making the out of doors their own. But the more recent specificity of Bird’s roaming map shows the harrowing circumscription of space up to the present: George’s great-grandson Edward, on a tether of some 300 yards, and with few liberties to roam at will unsupervised, possessed less of a spatial narrative of his relation to the far more industrialized region of Sheffield today, as his mother’s was far diminished from that of his Grandfather Jack or the wide range of space George was trusted to personally navigate. The narrative of a restricting relation of the person to space in mapped by the narrowing boundary lines in Sheffield:

As much as describe the changes in Sheffield’s geography and the story of its expanding industrialization, the map presents a strikingly local microhistory which echoes and encapsulates frequently expressed concerns about the lack of exploring a safe urban space.

It was made in the capacity as health officer to Natural England, to substantiate a concern for Bird’s belief in the benefits access to grassy areas, ponds, and trees brought to kid’s behavior and school work, and question the healthiness of the narrowing relations of space from George, his son Jack, his daughter Vicki and the eight-year-old Ed. The creativity of these practices of cartography bucks basing maps on their synthesis of a large data sample, by questioning how maps can be creatively rooted in a narrative of individual experience, even in ways that preserve their value as a collective register of the experience of space–and how a Google Maps template might be distinctly personalized as a record of spatial knowledge.

Discontents with Google Earth maps lie precisely in the deeply problematic recuperation of a cartographical art that they perpetuate for their users. And so Jeff Sisson focussed on the spatial meanings and consequences of the threatened disappearance of the Bodega as an institution and anchor to urban communities in New York by crafting an interactive Bodega Map within the city’s expanse. In charting the survival of a store central to communities across different neighborhoods, the map almost anticipated the recent turn against Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s New York that the recent De Blasio victory seems to portend. In tracing the footprint of the institution of the Bodega, Sisson selects stores pressed out of existence in the absence of rent control for shops in the city’s expansive real estate market, and provide evidence of a vanishing urban culture of diversity.

Sisson’s website invites all visitors to place Bodegas in local neighborhoods to elevate the individual discovery of a community store, in an exercise of collective crowd-sourced participatory mapping that displaces the archipelagic city’s usual contour lines by rather trying to map the local meanings of these distinctive and useful stores within local communities, in ways that invite one to insert one’s narrative connection to the colorful local Bodega so long an urban fixture situated at odd street-corners, combining such mapping resources as Google Earth, Google Maps, and Flickr snapshots of facades and marquees of individual family run stores.

The project “Mapping Bodegas” tracks processes of micro-urbanism, by marking sites of interaction and stages to which communities respond, to reflects on the danger of their erasure from the city’s map and its neighborhoods, as well as to preserve meaningful “hot-spots” of collective memory within outlines of the specific neighborhoods they nourished. This infusion of narrative content is, to be sure, one reaction or response to the universalized abstraction of an anodynely marked places of interest in the space of Google maps, with something approaching a zero-degree of the denotative signs of registering affect or place. It is in reaction to this lack of narrative that Adam Bartholl staged his public sculpture “Map,” creatively appropriated the blandly uniform “inverted tears” of a Google map push pins by placing these physical objects in the very center of Arles–on the hexadecimal longitude and latitude GoogleEarth uses to denote Arles.

The discontent with the abstraction of our knowledge of place in Google Earth led Adam Bartholl to remind us of the increased distance between iconic cartographical markers Google employs so blithely in its tiles and knowledge of places they denote. By the co-option or appropriation of the sign of place in geolocation practices in the public square of Arles, Harmon argued, Bartholl reminded us how the marker shapes (and fails to capture) our sense of place, as we use it to make our narratives of travel: by placing a larger than life physical embodiment of such a dayglo pushpin in the exact center of Arles’ public square on the altitude and longitude where it occurs in Google Earth, Bartholl asked us to confront a physical embodiment of a sign we too often internalize without interrogating its affectless muteness as a sign as itself a denaturing of place.

Arles? It happened right here . . .

On a more political level of the silences concealed in many maps, and the environmental consequences of these silences, Harmon turned to the failures of mapping ecological disasters of Bonga oil spill and transformation of the Niger delta. What are the limits of Google maps in tracking the multiple levels of ecological disaster within the Delta, seat to a preserve of some 600 million barrels of recoverable oil mapped in 2001, but whose mapping silenced the complex narrative of regional toxic pollution that has spun out around those platforms and oil rigs.

The delta, an oil-rich area long plagued by irresponsible levels of annual oil spillage greater than in the Gulf of Mexico Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010, is a site of widespread flares on rigs, and, as a very poor area where oil was found close to the surface, of dirty DIY oil refining and extraction have created deep-set ecological disasters through the Delta–over 7,000 spills from 1970 to 2000, some spewing at least 9 million barrels of crude into wetlands that sustain millions of local trades from fishing to agriculture, and where consistently poor clean-up of spills have eroded increasingly fragile local communities and economies in an image that, viewed from space, appears both ecologically fragile and remarkably pristine.

How to map the devastating ravages to the local environment, whose production the Nigerian government is economically dependent, is particularly problematic since the oil-rich delta is the source of 90% of the country’s foreign earnings. Regular under-reporting of spills by NOSDRA–the Nigerian Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency–to keep in line with corporate claims led to a failure to register the escape of up to 60,000 barrels of oil in 2011 from one Floating Production Storage and Offloading Facility at the Niger delta’s mouth by Shell oil (Nigeria’s major client) in Bonga, or 1979 spill of 570,000 barrels of crude, also by Royal Shell–eroding the environment all up the Delta, by the devastating toxic effects of acid rain that are only starting to be mapped–from the ruin of coastal livelihoods and fisheries to deadening formerly plentiful fields of kola nuts.

How to map or embody the narrative of the destruction of an ecosystem? This time-lapse map seems as disembodied as Vassily Kandinsky’s “Einige Krise,” but charted decade-long oil flares in surrounding coastal waters spewing crude into the air, in color-coded fashion since the expansion of oil drilling in the Deepwater Bonga project since 1993–blue from 1995; green 2000; red 2006–as the outlines of an ecological disaster since deepwater drilling began–and whose mapping almost defies narrative:

If the agglomeration of colored dots in this time-lapse map suggests pattern, the distribution mirrors the division of the Delta and surrounding waters by prospecting leases for locally administered oil fields since 1993, but only starts to map the disastrous consequences for the environment of this massive release of crude into the ecosystem and its local economy:

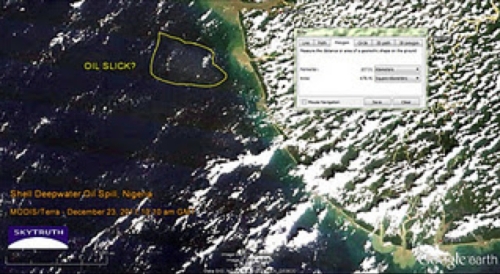

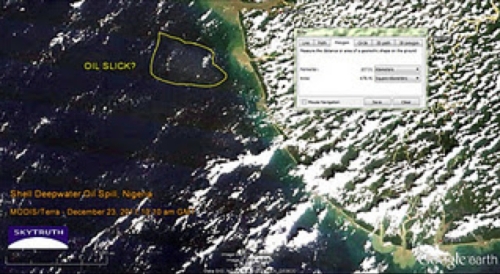

While the slick produced at Deepwater was not at first mapped, it occurred on a 2011 Google Earth view charting oil slick on the ocean’s surface:

This map provided one of the few media sources documenting the Bonga spill not provided by Royal Shell Oil itself. Indeed, it only starts to track the implications of the spills, fires, and leaks in the Delta that constitute the largest wetlands in all Africa rich with swamps, estuaries, rivers and streams, and can only suggest the extent to which forests and mangroves are being polluted by spills from a network of pipelines, acid rain, and water-borne or rain-borne oil slick–rain regularly returns drops of crude oil to formerly fertile region–where oil is relatively close to the surface has led to a distortion of the environmental perils of oil extraction–and over one thousand abandoned oil spill sites in the over-drilled Delta, with huge environmental consequences–often blamed on the ships that regularly illegally siphon crude from the pipelines that criss-cross the delta.

Google Earth views used by Sky Truth to map the 2011 Shell Deepwater spill barely chart the environmental devastation on the Delta rivers. The map that almost leaves one speechless in how the beauty of its sinuous detail chart the slicks of oil that have contaminated a once-healthy delta’s agricultural wealth; this NOAA aerial photography created by the United States Navy rebut the oil multinational’s silence as to the spill’s scope or devastating consequences, whose silences have only recently been targets of international blame, and obscured some 474 spills in one area during 2012 alone. Perhaps the recent expansion of Nigerian crowd-sourced mapping projects may shift these cartographical silences, but the burden for mapping the disaster has not been met.

The narratives that these aerial image of considerable beauty recover present a counter-narrative to that of the corporations that distanced themselves from the Bonga spill, and perhaps a case of maps speaking truth to authority. These maps begin to tell a story of the transformation of the land–and the destruction of the environment they map. These maps foreground new narratives about the Google Earth format that invite a broader story to be told about the event, and to fill the silence of Shell’s official narrative about the quantity or causes for the massive spill–and the blanket denial that any of the oil ever reached the coastline, and all barrels were successfully dispersed in the ocean waters, and seek “unconditional license to contain and disperse the Bonga oil spill” itself. Without these Google maps, Shell Oil would have retained a monopoly about the production of truth about the devastating Bonga spill.

Can a narrative emerge of this event from the perspective of those who dwell in the Delta, to capture the consequences of the toxic transformation of the land they live and work in, or those for its non-human inhabitants?

Some semantic possibilities of expanding the ecological narrative of place were suggested in the tracking of growth of Chesapeake Bay grasses, in a mapping project using data to track changes in the growth and density of grasses around the largest estuary in the United States particularly illustrative of the subtleties of overlaps to achieve the sort of deep mapping that Google Earth would not allow. The Stamen interactive map frames a unique narrative of the restoration of the estuary ecosystem incorporating data from over forty years across some forty years, redirecting data to create an image of where the estuary might later develop: the time-sensitive visualization of data about salinity, water-temperature and bathymetry with the restorations of bay grasses who are the subject of this narrative of ecological restoration, to offer a powerful–and positive–interactive map about the local recuperation of environmental health, by synthesizing a wide range of data from the EPA officials and local institutions about an area to reverse effects of chemical pollutants on wildlife and grasslands that viewers can read or virtually explore as unfolding over time, in ways that press against the technological boundaries of cartography as an art.

If this graphic visualization of the watershed appears a document only of the growth of grasses, as we unpack the map we realize the expanse of the effects of the possibly narratives of human interventions in the landscape that it presents–both on the ecosystem of the estuary and to possibilities of our future relation to that very dynamic environmental space–a space we better know through our more multi-leveled representations of it.

The art of registering knowledge of place has expanded to comprehend new personal individual narratives of fine grain by a GPS revision of the Google Map view of a city. Indeed, the maps of Christian Nolde and Ingrid Burrington both seek to recuperate the density of specific narratives of encounters in urban space that echo and engage the emerging forms of mapping by which Google seeks to plot points of interest for its users on the maps of cities that they visit, so that they might include selected points of interest, sites of beauty to visit, or local stores and commercial districts of interest judging by one’s web history. Both Nolde and Burrington used GPS to create a synthesis of these individualized maps of the city in ways that anticipated the announcement of Google’s plans.

Christian Nolde employed GPS technologies to register of feelings related to place in his emotional map of San Francisco (2007), created during a tenure at Northern Exposure. After collecting on data gathered by a galvanic skin response by which participants’ physiological responses, he keyed them to places that he transposed to a GPS map of the city’s locations, as if to trace itineraries in a city usually mapped by city blocks or along district lines. The maps seeks to register responses to a location or geographic environment on individual emotions, in a sort of counter-map synthesized individual responses into something like an encounter with places of specific individual resonance in the city, in a record “visualizing the emotional space of the city” by objectively tracing an alternate topography in 2007.

This map has a texture of accommodating the individual storyline or narrative that makes its reading an active part of its enjoyment, by engaging individual storylines in a dazzling if fragmentary novelistic detail, challenging the legibility of the map’s surface of significant local depth for readers who can take the time to delve into the map to read the actions that its maker associated with a specific place, but which would be ‘overlooked’ by scanning the broader path of his itineraries across the city:

GPS was used, in other words, to contextualize multiple narrative fragments in a composite view of the emotional significance of urban space by tracing if a residue of collective emotions on its surface. The completed artifact combines multiple spaces of reading, augmenting the notions of position that he noted in GPS at specific way stations by his own transient or apparently ephemeral personal reaction to the city at a specific place–“beautiful street with lovely houses”; “went into my house and got my mail”; “This is where I had the bike accident”; “i was remembering a person I had a major relationship with whose parents lived here”–that foreground the personal in ways GPS cannot alone register.

The practice of GPS creates a synthesis of discrete meanings rarely associated with geospatial mapping, and puts a premium on emotional or associative precision, as much as the abstraction of terrestrial locations. A similar desire to base a map on personal narratives to record the city as an emotive space led Ingrid Burrington to take data from Craig’s List “missed connections” as the data to reveal a hidden distribution of the desire for half-glimpsed connections in her “Loneliness Map” (2009-11), included in an earlier exhibit of personal maps Harmon earlier curated.

The map’s unique pinpoint form focusses observers’ attention on mini-moments of “missed connections” in the course of the day against a map of physical topography and street intersections, as if to present the variations among missed connections as an emotional terrain or urban psychogeography, creating a new sense of reading mapped data to register a notion first used by situationists such as Guy Debord.

Such collected ‘mini-moments’ trump the topography of the city, tracking personal attachment to selective moments in urban space as more meaningful than the mapping of the outlines of its streets that create a new experience of reading the map’s surface. They recall the Mappiness (LSE) smartphone app, which disrupts the relative abstraction of space in a GPS framework by registering our own states of happiness on a map.

The map becomes a site to register individual travels through the city in a collective document, or a capacious holder of narratives, as tangible with resonance as any map might ever be. And the very tangibility of this record of encounter that maps allow, even with limited qualitative content, suggest the underlying basis of cartography as an art.

aBefore these maps of spaces of dehumanization and devastation, we are really looking into hellish worlds we had not been able to see before. But even these dots cannot capture the scale of the hellscapes that emerged for the accelerated loss of life within the industrialization of death that proceeded from Heinrich Himmler’s order of 19 July 1942 stated that unleashed mass-killings from bullets, fire, and gas extermination to fullifll the demand that by the end of December 1942, all Jews, gypsied in Greater Germany be killed, leading to an unprecedented intensity of rates of mass-killings almost impossible to map on paper or by a graph, challenging as the spatial dynamics of the three-month long burst of killings is poorly documented–intentionally–and

aBefore these maps of spaces of dehumanization and devastation, we are really looking into hellish worlds we had not been able to see before. But even these dots cannot capture the scale of the hellscapes that emerged for the accelerated loss of life within the industrialization of death that proceeded from Heinrich Himmler’s order of 19 July 1942 stated that unleashed mass-killings from bullets, fire, and gas extermination to fullifll the demand that by the end of December 1942, all Jews, gypsied in Greater Germany be killed, leading to an unprecedented intensity of rates of mass-killings almost impossible to map on paper or by a graph, challenging as the spatial dynamics of the three-month long burst of killings is poorly documented–intentionally–and