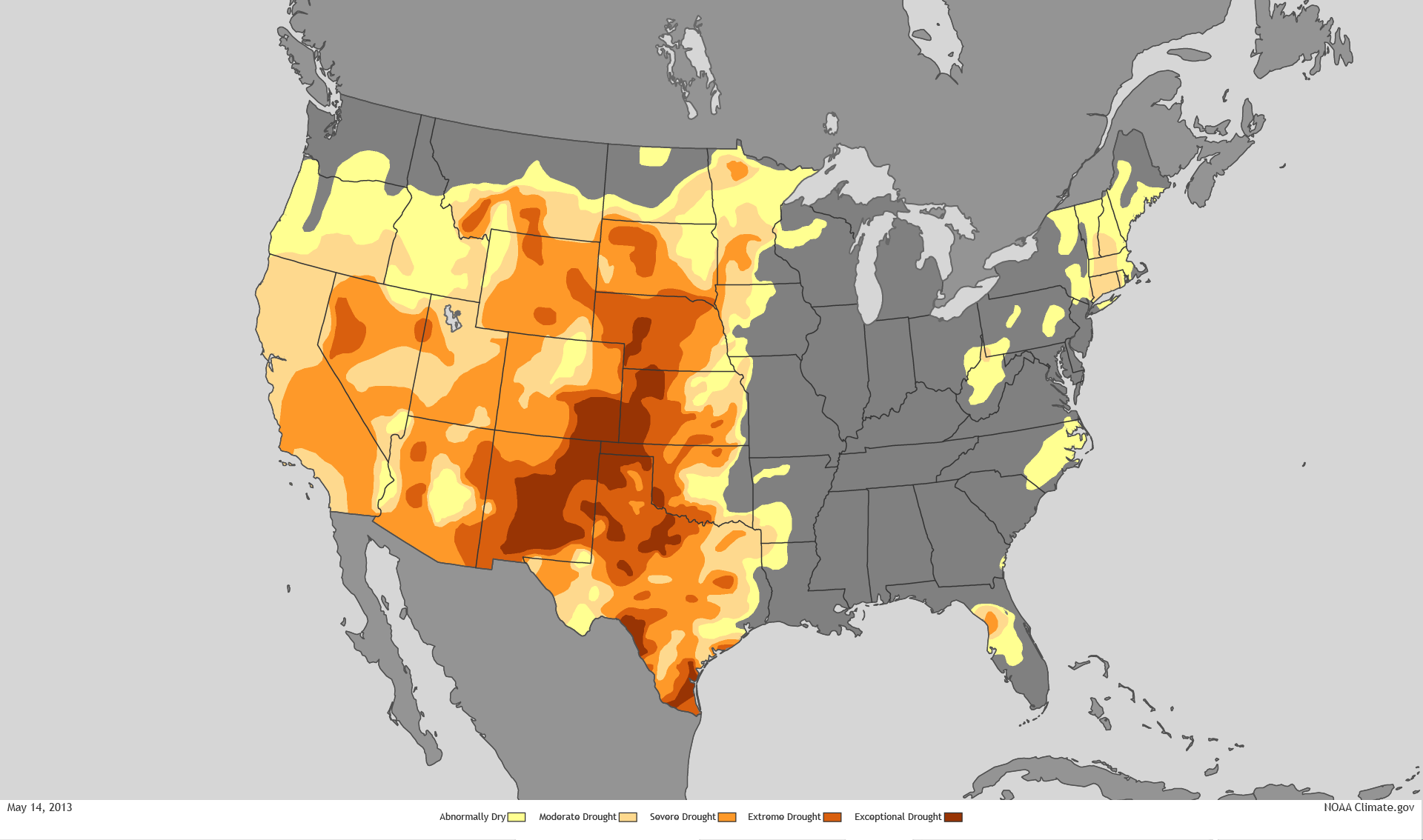

The southwest and states east of the Sierras magnify the effects of global warming in the intensity of their aridity. But global warming reveals a new relation of regions to overheating, and reveals the depths of inflexibility to accommodate water scarcity, as well as the tragedy of its effects. As aridity of the soil and reduction of groundwater reaches unprecedented scales, our passivity is accentuated as we are suspended before maps that try to visualize unprecedented aridity magnified by global warming and its magnifying effects.

For the cascading effects of warming on the land and environment might be mapped in ways that cannot essentialize the greater “aridity” of the region, but the effects of increased aridity of soil, air moisture, and dry air on a region that we have remade into a region of food supplies, agriculture, and livestock, but, beyond, on hydropower. While the Colorado mountains long provided an effective basin to gather rainwater for western states that have been funneled to state reservoirs for agricultural irrigation, the man-made irrigation networks were drying up as the snowpack determinedly fell, and warmer temperatures evaporated what snowpack fell.

The logic of this longstanding pattern of appropriation of water from across the Colorado Basin was in a sense begun with the Hoover Dam, but was, writ large, organized by very process of appropriating water rights to redistribute water that had been enshrined in California from the turn of the century, circa 1914 and the policies of filling reservoirs to redistribute water rights. While we have considered appropriative water rights a distinct feature of how water is redistributed unique to the Golden state, the appropriation of water rights by reshuffling of water in state’s now precarious supplies how diverts over 99 million acre feet of surface water diverted along the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers to farmland, created a powerhouse of national agriculture. Much of the 75 million acre feet that flow from reservoirs across the state evaporates before it arrives at crops, however–far more that actually reaches the farms or cities.

–and the growing heat of the Great Plains have likewise diminished surface flow of the Colorado Basin already reduced by diminished rainfall. The increasingly warmer atmosphere of recent years has created a new “Arid Region” of the United States, of even greater aridity than when it was first mapped by John Wesley Powell in 1890, and the renewed aridity of the region not only challenges the calculus of water distribution according by appropriative rights that is structured by the Interstate Compact, but the very logic of redistributing water.

The past two decades have seen the departure of seven trillion gallons from Lake Mead, the largest reservoir on the Colorado River, holding rainflow from the Upper Basin before it crests the Hoover Dam. The drop will trigger hydrologic stresses across western states, as ever ever-increasing amounts of water are sucked up into drying out air and atmosphere, requiring more abundant irrigation of croplands and grazing grounds. This new and expanded “Arid Region” suggests a return of the repressed, returning at even greater scale and aridity to haunt the nation by a lack of groundwater again.

that is not to say it ever left. But the solutions of diversion have been undermined by the cascading effects of climate change and increasing temperatures, across an expanse of irrigated lands where water from the Upper Colorado, as from the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, are funneled to cities, farms, and irrigation projects, and used to generate electricity. Even as Californians and westerners face the threat of further fires more destructive than any in recorded history–potentially enough to energize an implausible recall effort in the state of California–we face the problems of managing not only historic drought, mandated energy shortages, reduced water supplies. The climate crisis appears to have provoked a deep crisis in leadership, but one without easy means of resolution.

The most improbable political candidates–global warming skeptics after Donald Trump’s heart–have argued drought, wildfire, and electrical storms reveal Gavin Newsom’s lack of leadership, even as they stridently object to aggressive climate legislation aimed at emissions reduction as restraining the free market business,– preferring a free market approach for all climes that would be the laissez-faire redistribution of water to the highest bidder, monetizing a scarce resource to consolidate financial profits and gain in response to diminished water supplies.

As more water is being released from Upper Basin reservoirs to make up for the shortfall in Lake Powell, but the shortage of water in Lake Mead–the largest reservoir in the United States–to less than 40% capacity by 2022 will mean reducing water for lower basin states like Arizona of 812,000 acre-feet, Nevada–by 21,000 acre feet, and Mexico, by 80,000, that have led to the call for new “water markets” to be created across the western states. Indeed, even western states no longer carry the brunt of increased use of freshwater for irrigation–

–the demand for conserving water in agriculture is increasingly incumbent on western states, so much so that the shift to less water-intensive crops–like California’s almonds–at a time when many crops require more irrigation, and a shift toward fewer acres of pasturage for livestock–good luck–have become a necessity. Increasing the efficiency of irrigation systems is necessary–ending customs of flooding fields, increasing drip irrigation, center-pivot irrigation, or micro-irrigation, in a New Deal for agriculture, even regulating irrigation systems before water markets price rural communities out of their accustomed access to freshwater. The increased trend toward shifting the distribution of water by “water markets” from lower- to higher-value use is dangerous for farmers, and indeed all rural areas, but also for the western ecology, as it would be the most difficult to preserve water in rural communities or farming areas less able to pay for pricing of water for higher use-value, although they currently consume over 70% of the water in the Colorado basin, or encourage sustainability in regions that are increasingly facing realities of sustained drought, if not megadrought of unprecedented intensity.

Yet the systems of allocating water from the Colorado River by a system of dams, diversions, and canals have led to broad calls to end further projects of water diversion, as the diversion of water to western states may be drying up itself by up leads to calls for new policies of allocating water, not based on the highest bidder, as the river we have made increasingly mobile across boundaries will be divided or redivided between agriculture, urban use, indigenous Americans, and land trusts, as we are in need of redefining the working basis for conserving the redistribution of water rights beyond capture and diversion, and outside of existing water markets and appropriative water rights within states. While the Bureau of Land Reclamation has run the reservoirs, dams, canals, and hydroelectric plants and contracting with individual districts, a broad reconception of practices of regulating water markets, allocations of water, and costs of large-scale water diversion, as demand for water outstrips supply.

Yet as increased farmers are withdrawing water from the ground, or from rivers, from California’s Central Valley to the Lower Colorado River Basin, in Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada, the need to reduce the eighty percent of water dedicated to agriculture across the west will demand new practices of conservation, beyond what John Wesley Powell mapped, in 1880, when he advocated new practices of land use, as climate change increasingly destabilizes the Basin, including the thirty sovereign Native American tribes along the river basin. The need to manage demand and riverflow that will begin with the start of the “Tier One Shortage” from 2022, will introduce new rules on water-use and supply that stand to reduce the amount of water flowing to Arizona by a third. Water diversion from the Colorado River has transformed the land west of the hundredth meridian by re-engineering its flow to make the “desert bloom.” Yet the recent dramatic reduction of rainfall, river flow, and increased aridity of the lands, leave us contemplating the viability of relying on water diversion.

The new arid region is reflected in weather maps, but will be a region of radically reduced piped water and a new landscape of hydrologic diversion. If the “Arid Region” was mapped in earth-tones of clear distinction as a cautionary way by explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell, to alert the government to the distinct climate of lands west of the hundredth meridian, the recent area is both based on more detailed and specific remote sensing records, often from satellite observation, but suggests a far more complex area to manage.

For the western states are linked, both by projects of water diversion, and by hydropower, to a region where rainfall and snowpack has declined, and far less water enters into the river-flow of the rivers whose diversion allowed the expansion of agriculture and livestock across the western states. Due to global warming, the earlier “arid region” expanded, returning bigger and better than ever since it was described as extending west from the hundredth meridian by John Wesley Powell, in one of the foundational maps of climate aridity. In today’s parched California, dangerously low levels of rainfall across the central valley seem to belong to the Arid Region. But we have hardly come to terms with its new expanse or migrating edges. The “lands of the ‘Arid Region'” that Powell had hand-colored with earth-tones to communicate the dramatically falling rainfall west of the hundredth meridian long ago mapped a biting response to the eagerness of homesteaders to Go West, cautioning about constraints on water-rights that division by states–rather than drainage districts–would bring. If current rainfall maps of USDA or EPA seem to engage in dialogue with Powell’s old polemical cry, the limited traction of mapping policy against increased pressures of climate change place most maps in a sort of Scylla and Charybdis, located not in the Straits of Messina, but the scissors of decreased rainfall, rising temperatures, and lack of groundwater retention.

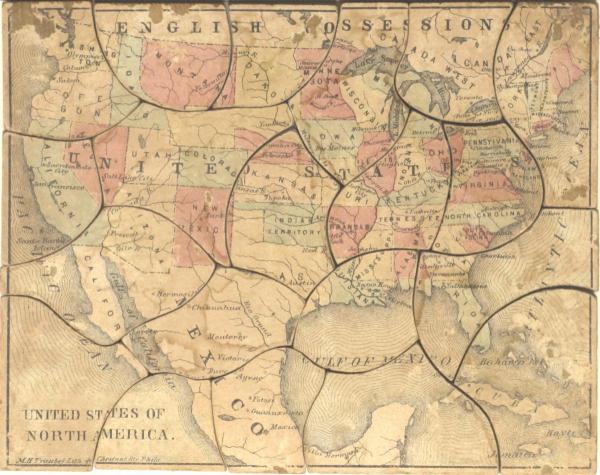

1. The problems of managing water rights and ensuring flow are now far greater than what Powell’s creative palette of before the fact overlays even imaged was able to depict, and was a puzzle beyond the interlocking pieces of drainage districts that he–as if akin to the first puzzle-boards composed of hand-painted maps, as this forty-nine piece puzzle map of ca. 1849, painted by Kelly & Levin, of the similar region, that curiously compressed the western United States. Was Powell’s map indicative of the difficulty of solving the puzzle of allocating water resources across arid western states?

While the puzzle pieces rarely echoed the shapes of individual states, undoubtedly because o the difficulty of their cutting the contours of states, the puzzling of how the rivers of the west would align with states in this roughly contemporary 1880 Milton Bradley map-puzzle, an “Outline Map of the United States,” posed by including light blue rivers across a map with little sense of varied topography.

In contrast to the resolution of assembling individual pieces of a map of fixed bounds, the expanded arid region mapped by remote sensing spans a farther territory and expanse, and raises deep questions of access to water or even soil moisture in a region that developed as an agricultural breadbasket and locus of husbandry of livestock.

The growing puzzle broached by how the water supply of the west will be reassigned is rarely faced or addressed, although it is ruminated upon as the sub-text–or super-text?–of terrifying maps of rising aridity and low rainfall across the western states, that magnify a new “arid region” with less clear suggestion of an outcome of land management but pause before the cyclically compounded effects of rising heat, low soil moisture, limited run-off, and the specter of drastic irrigation cuts.

Current remotely sensed maps use far less clearly set boundaries or edges of water-shortages, but pose similarly pressing puzzles of how to resolve the appropriative logic of water rights, as drought intensity reduces the water that once flowed from the “upper basin” of the Colorado, feeding the river and redistributed water, and even more surface water is lost to evaporation.

The puzzle of hydrological access to land-water has become so curtailed across western states, that increased pumping of groundwater risking depleting aquifers by draining vital aquifers, irreparably damaging rivers and riverine waters. The New Arid Region, afflicted by far more aridity and low soil moisture than at any time, parallel to increased global suffering of warming and increased heat, the persistence of private water “rights” to agrarian expanse stand increasingly on a collision course with global warming throughout the new arid West in ways we have yet to address, even as we recognize that we are facing a climate emergency of the sort without precedent in modern memory.

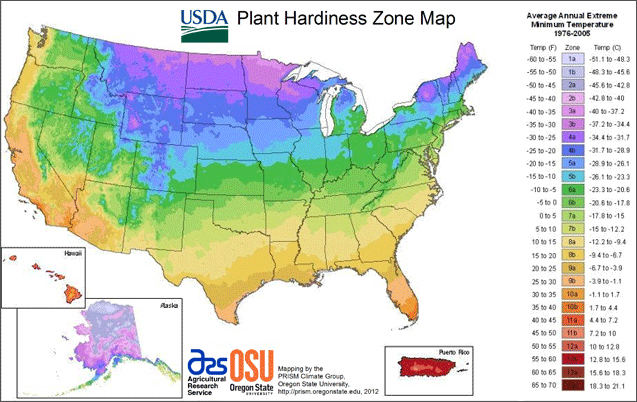

from PRISM Climate Group, Oregon Sate University

2. No single visualization can, perhaps, adequately come to terms with the unprecedented aridity of the recent years. For no visualization can fully capture the cascading and magnified effects of declining water and soil health, and their effects on ecosystems, as much as on livestock or irrigated crops: the distance from reduced irrigation and new climate specters demands an intensified map. But the terrifying nature of the intense aridity of western states in part lies in how we have seem to forgot the semi-arid nature of the region. The deeper effects of a drying out atmosphere were evident in the huge deficit in water vapor in the past decade during the “fire season” from August to September, dramatically unlike how fire fighters navigated the same terrain in previous decades, when many fire containment strategies were developed and many active firefighters had trained. The map is one that should raise immediate fears of the loss of a landscape of future irrigation, and the need for tightening agricultural belts and shifting our conceptions of food supply and water budgets–as well as the same landscape’s increased combustability and inability to manage or control by an old playbook.

The previous month has brought an even more pronounced record of drought across the Upper Basin of the Colorado on which so much hydropower relies, as do other schemes of water diversion.

The revelation of a new intensity of exceptional drought in many pockets of the Upper Basin of the Colorado River presses the bounds of how we imagine dryness, aridity, and their consequences, even as we rely on older methods of fire-fighting, and fire-prevention, and outdated models of water diversion and energy resources.

The historical denial of what John Wesley Powell had already called the “Arid Region” west of the hundredth meridian, has become a snare for ecological disaster translating into a process of the drying out of long-irrigated zones, with consequences that the nation has not been able to comprehend–and demand a New Deal of their own to replace the diversion of water and generation of energy in the Hoover Dam. Or have we forgotten the intensity of a differential of climate, soil moisture, and increased aridity that Powell long ago mapped in order to illustrate the new regime of government its unique atmospheric conditions it would require, using his uniquely designed palette to hint at the best way to organize the region of water scarcity according to the units that its drainage districts–rather than the state lines surveyed by latitude and longitude?

Powell had explored the canyons, rivers, and plains, as he addressed the Senate Select Committee on the Reclamation of Arid Lands in 1890, he crafted an eloquent seven-color map of rich earth-tones to impress readers with the sensitivity of the region’s texture and urge restraint for expanding the westward flow of homesteaders with hopes to make the desert bloom. Indeed, by circumscribing areas for which sufficient water in this “Arid Region” would be able to providently allow future settlement, Powell neatly divided areas for settlement in a region by hydrographic basins collecting sufficient rainfall for farming. Whereas rainfall maps of previous years mapped a blank spot of water scarcity, Powell hoped to direct attention by a devising a map of the region’s subdivisions that called attention to its soil quality and decreased moisture, focussing on its distinctly variegated terrain in ways foreign to Senators in Washington. Powell hoped to convince who were removed from the region to acknowledge the commanding constraints created by these drainage districts for all future agricultural development and settlement–an unpopular position that ran against the notion of allocating free land in an age of expansive homesteading. If the image of a “drainage district” was foreign to existing state lines, Powell’s image of an “arid region” long haunted the geography of the American West–and contributed in no small part to the subsequent reengineering of the waters of the Colorado River.

In light of the dramatically increased aridity now endemic to the western states, Powell’s map gains terrifying relevance as western states enter severe drought, placing the breaks on once-expanding developments across western states. Powell’s map articulated a historical vision of the limited infrastructure of water in the American west. While the technologies of irrigation that allowed such a massive project of damming and canalization only later developed, did his map inspire the need for a project of such scale as a better model of land management? The intensified aridity that afflicts the western states responds not only to low levels of rainfall. We continue to hope groundwater depletion that afflicts the lower basin won’t extend to the Upper Basin of the Colorado River that has captured water on which so many farmers rely–and thirty-five million north of the border and three million living in Mexico depend, across its Lower Basin. The escalating megadrought has created pressures across the overpopulated west that the water-sharing model Powell proposed for drainage districts cannot resolve, but the distinct forms of water management he advocated have been forgotten, as the declining water level on the Colorado River seems a time bomb as its waters have fallen so far below capacity that while the waters that drain from the Upper Colorado into Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the western states, are only 37% full, and Lake Powell stands at 34% capacity. As less and less water enters the river system of a drying-out west, the future of the river on which so many rely for irrigation and energy is all but uncertain.

Demand for water in the upper basin and older technologies have meant far less water reaches the lower basin, but what does has been redistributed across western states–absolutely none reaches the ocean at the river’s old delta. Supplies of surface water and groundwater barely provide for the border region, as the overdraft of the basin’s aquifers have made trans-border water management a crisis often overlooked in favor of water management north of the border. As unprecedented soil aridity currently seems to run off the rails, after three summers of no rainfall have depleted soil moisture, may remind us how we have missed the lesson of Powell’s map of instilling new set attitudes toward the land, as the volume of riverflow consistently dropped as it crosses the Mexico border since the filling of the Glen Canyon Dam.

Does selective amnesia underlie how we map the drying out of the west? Most data vis of rising temperatures and low rainfall across the western states is already magnifying and escalating the effects of unprecedented heat over twenty years in a deeply melancholic vein, daunted by the scale of dryness across such an interstate expanse, and passive before an absence of atmospheric moisture that seems a modern casualty of global over-heating. If we were already “living in the future” in California’s frequent and increasingly extreme fire regimes, the multi-hued data visualizations electrify the landscape–and not with power or hydro-energy, but by the all-too familiar color ramp of the extremes of climate change we have been trying hard not to normalize. These images chart a landscape that has gotten away from us, outside seasonality changes, making the American West a cautionary case study for global climate change inspires melancholy.

The additive logic and graphic syntax of maps, long before the separate map-“layers” that accommodate information from GPS, provided a basis to define the fungibility of water and the emergence of “rights” to water across the Arid Region, enabling the idea of governing the transference of water and water “rights” across the region, that separated water from the landscape and environment. The flow of water had long been understood and reconstrued in the west by a logic of irrigation needs–and the “rights” to unpolluted water for livestock raising, pasturage, and agricultural needs of land owners–that was removed from conserving groundwater needs. The increased nature of the fungibility of water as able to be transacted across basins, state lines, and counties reflects the legal fiction of considering water as a “good” tied to the needs of property owners, that, long before global warming, had already sanctioned the removing water from the ground.

If we use metaphors rooted in temporality that try to come to scale with the new era of global warming that cut down and perhaps minimize the era of water scarcity. in which we are entering–“heat waves,” for example, that broke records in states from Washington to Idaho in June and July, breaking or matching records of hot temperatures, the levels of aridity that have allowed the ground to grow arid and degrade have not only led to a spate of western wildfires, but have changed the levels of soil moisture over the long term in ways we have difficulty to map in the scale of our weather maps, or even the maps of the U.S. Drought Monitor, as the cascading influence of such unprecedentedly dry conditions–where stresses on river water create extraction of groundwater that stresses aquifers and groundwater supplies–can be scarcely imagined, or confined to the conventions and color ramps of weather maps.

We have struggled for decades to process the cascading effects of waves of unprecedented heat that over time have produced a drying out of soil and reservoirs over the past twenty years, resulting in an expanded and far more destructive fire season and parched lands whose effects we cannot fully come to terms or comprehend, as we have not seen or experienced the extent of dryness of subsoil, soil, and low rainfall which the US Drought Monitor seems to have mapped, as drought expanded not across the entire Pacific Northwest, from Oregon to Idaho, or 86% of Idaho–by the land’s combustibility, impossible to read without premonitions of lost forests–including old growth forests–melancholic fears more than tinged by an acute sense of a lack of agency.

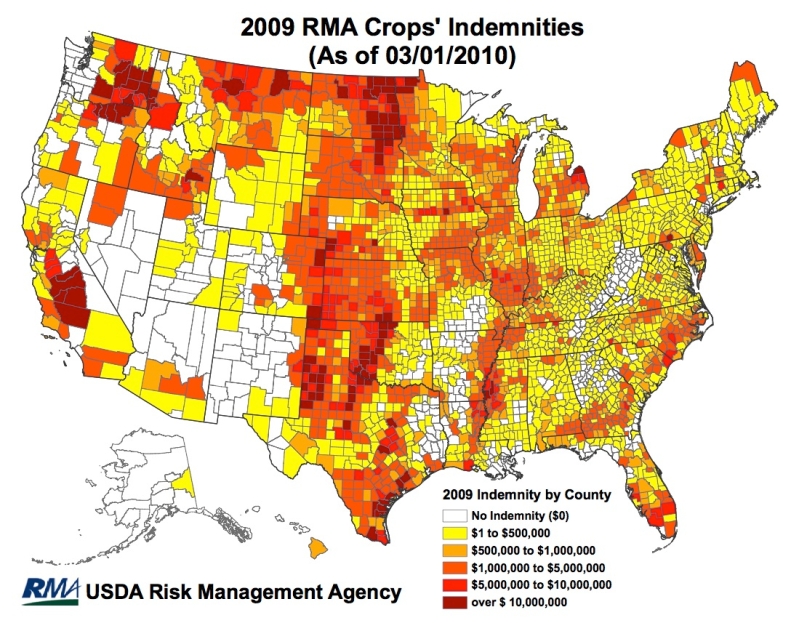

The sense of struggle with an absence of agency–at the same time as an almost moral urgency–reflects the difficult to process such absence of water as a landscape we have inherited from the rapidly accelerating dynamics of climate change. The history of the increased aridity is all the more poignant as a source of melancholy not only because exceptional drought was the standard before President Trump, and a national emergency before his Presidency. We have failed to register this national emergency with the same immediacy, even as the theater of the border was magnified in disproportionate ways in public discourse on migration. The sense of melancholy is compounded as the map seems haunted, if only tacitly, and perhaps without acknowledgment, by the fact that the head of the USGS in 1890 admonishingly illustrated virtually the same basins now suffering severe and moderate drought as distinguished by semi-aridity–if the current levels are nothing like those faced over a century ago, when the transition of public to private lands. We have recently mapped the substantial threat of increased aridity to the Great Plains–less than a tenth of whose croplands are irrigated–where farmers depend entirely on rainfall to grow soybeans, sunflowers, cotton, and winter wheat, the fear of greater “dry spells” as anthropogenic emissions drive decreasing rainfall and groundwater reserves–a term that tries to convince us they are not permanent–led red flags to be drawn in broad brushstrokes in those states, where extreme and exceptional ‘drought’ .

NOAA

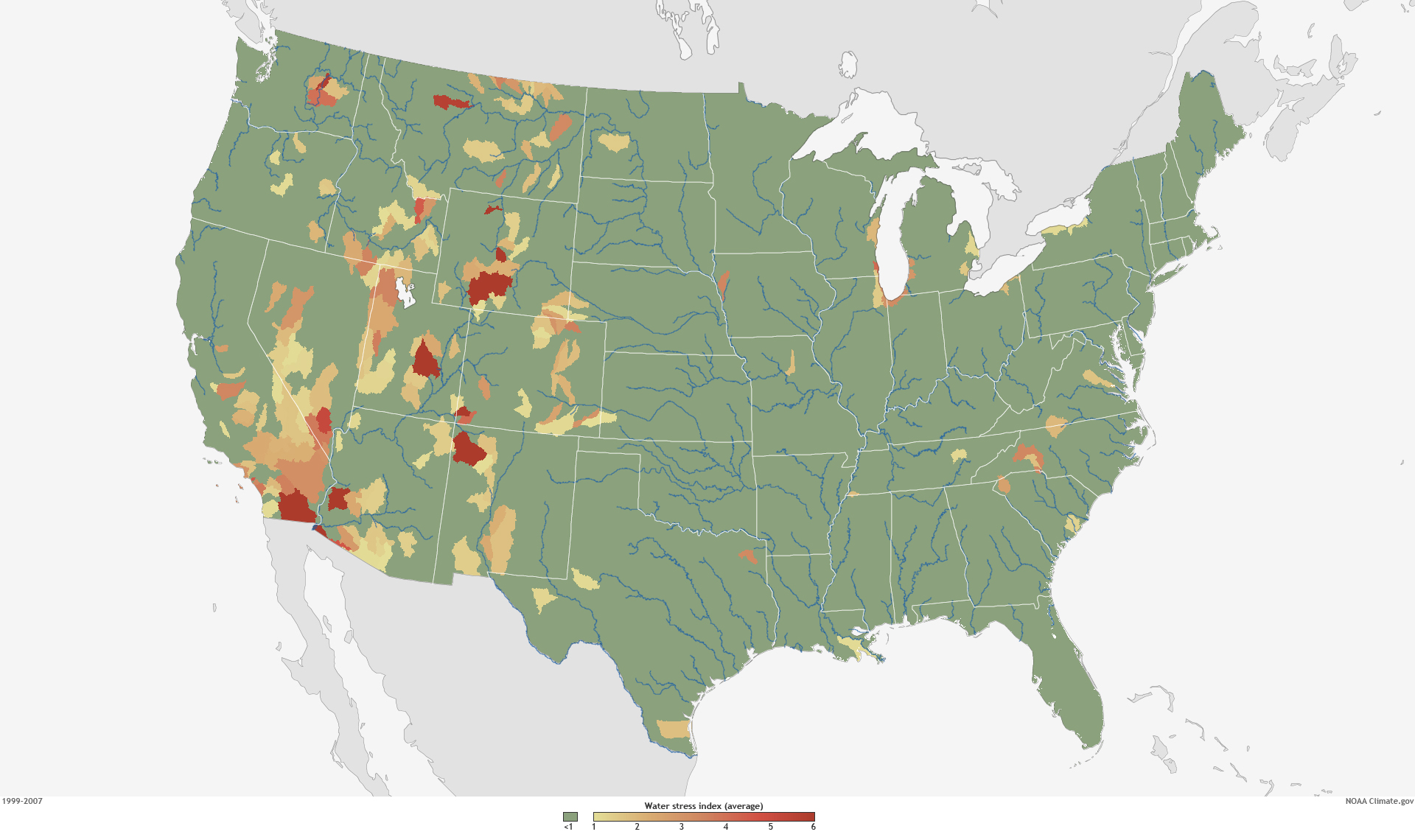

But climate change has created a new concept of “water stress”–stresses best be pictured not by the isotherms of weather maps, but the watersheds and drainage districts that were the basis of Powell’s revolutionary map, and matching the very region of the Arid Zone where the soil scientist Powell turned viewers’ attention to the crucial index of ground and soil moisture, the true determinant of the future of agrarian settlement and the future of food. The regions determined of greatest future stress were the very basins that Powell mapped, and suggest the relevance of his map, as well as his caution of the difficulties of governance in an area of severe water stress-stress being understood and indexed as a relation between supply and demand, as well as rainfall, in national watersheds.

3. The “Arid Region” of the Untied States had been austerely and admonishingly described by John Wesley Powell as a geologist to caution against the administration of its future settlement with a level of clarity that reveals his Methodist upbringing. It is hard to know how clearly we can ever parse aridity, in an age when rising temperatures have unremittingly drained soil of water. As if informed by a deep respect for the map as a clarity of record, possessing the power to reorient readers to the world by preaching a new relation to the land, Powell had placed a premium on cartographic form as a tool to re-envision local governance–and prepared his striking eight-color map of the limited rainwater that arrives west of the hundredth meridian, the eastern border of what he baptized as the Arid Region, an almost zonal construction akin to a torrid zone.

The imposing title of this reclassification of the interior of the United States revealed Powell’s own keen sense of the map as a visual record of the territory, whose transparency as a record of the quality of the land would be a basis for all discussion of settlement. Powell parlayed his own deep study of the geography of the Colorado Basin to query the value of parsing the administration of water rights by state lines in 1890, convinced of the need to oversee later apportionment outside the jurisdiction of the arbitrary boundaries of western states, but joined them to his sense of duty of preparing a legible map of striking colors to convey the constraints and difficulties for its future settlement– not only by the scarcity of the threads of rivers curled against its topography, but the few watersheds.

Powell trusted the map might mark the opening of the “Great American Desert” in order to alert the US Congress that the dry lands west of the hundredth meridian was a divide. Even if the meridian no longer marking as clear a divide of reduced rainfall, as we confront the growth with unprecedented degree of global warming of a parched west–both in terms of reduced rainfall and declining soil quality–it may serve as a model for the map we need for the future governance and administration of already contested water rights. Powell’s place in the long story of soil quality reflects how neatly the American west as a microcosm of global warming is rooted in the conversion of public lands to private ownership, into which warming has thrown such a significant wrench.

For the Arid Region’s aridity has since been unremittingly magnified, producing a region more arid than we have ever experienced and struggle to find an adequate color ramp adequate. But we would do well to try to map the forgetfulness of that arid region, even as we confront the quandary of the stubborn continuity of sustained dryness of a megadrought enduring multiple years, compounding the aridity of the soil, and multiplying fire dangers–and the conditions of combustibility of the region–far beyond what the west has ever known or Powell imagined possible. If aridity of soils and poor land quality has spiraled out of control due to “global warming,” raising questions about the future of farms and livestock, the absence of groundwater and surface water alike, global warming demand we shift from national lenses of water shortage to beyond American territory,–but also to discuss the warping nature of national lenses on the remaking of the sediment of the west–and Colorado Basin.

The difficulties of parsing river-flow by “states” as helpful political aggregations for future settlement was rebutted by the map, which sought to direct attention to the aridity of the ground’s soils to orient its administration in a region where water was destined to remain front and center on settlers’ and residents minds for the foreseeable future. The subsequent attempt to jerry-rig the question of scarcity of water by entitlements that rely on re-apportioning unused water escaped the constraints Powell located in the basic common denominator of groundwater.

As much as the region needs to be mapped outside a national context–despite the national nature of climate tracking–the hope of revealing imbalances of the drought indeed exist across borders, and impact water-sharing agreements, much as the smoke from recent northwest fires has traveled across the Pacific northwest. National territory is as meaningless an analytic category for global warming, or water scarcity, which, this blogpost argues, exists in a global contest of migration, as the migration or transborder transit of fires’ smoke.

4. The conditions of aridity that Powell described in the Colorado Basin and its neighbors offer an oddly productive image of the dryness of the ground, in an era before irrigation, that may be useful for how we can come to terms with the fear of a suspension of irrigation across western states. But it is as if the very definition of aridity was forgotten, as infrastructures of irrigation have re-mapped the region that John Wesley Powell in 1890 mapped as an area of difficult agrarian settlement, as farmlands of agrarian fertility and wealth. Powell proposed to view the “arid region” of the United States east of the Rockies with a clarity approaching scripture in a powerful eight-color map to instructively show how limited water constrained settlement of the region after surveying the Colorado Basin.

Powell probably imagined his map in somewhat revisionary as much as rebarbative, reorienting attention to the dry nature of the soil of the semi-arid region of the Colorado Basin by parsing it in areas by which the availability of water constrainted the settlement of the “open” government lands of the west, obscuring that they were seized from indigenous, to correct the mythic geography propounded by official state-sponsored geologists. Unlike Powell, most state geologists had boosterishly endorsed a site for future pasturage, to be enriched by unknown artesian springs, and ripe for settlement by homesteaders, and Powell’s map posed a more tempered image of resettlement that would obey the laws of the availability of water in the Colorado plateaux and other regions he knew so well, cautioning against the encouragement of settlement and sale to prospective farmers in ways that have improbably made the map something of an icon of conservationist thought. Against promise of prospective bucolic lands of pasture, the dry colors chasten viewers by communicating scarcity of water of drainage basins.

The arid region that Powell correctively propounded was long inscribed in the psycho-geography of the United States to be forgotten, but the arrival of irrigation infrastructure allowing irrigation of western states continues to inform, even in our own era of global warming, the return of the boosterist slogan “where water flows, food grows,” that is still raised in Northern California’s San Joaquin Valley, to protest “cuts to farmwater” in the recent order of an “emergency curtailment” across rivers of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta watershed — essentially the entire Central Valley. The recourse to an engineering “miracle” of making water flow uphill and redistributing more water from reservoirs contest calls for conservation–and only demand the further construction of dams, reservoirs, and water storage for better irrigation. The very promises that the flow of the Colorado River would irrigate lands, that made good on the promises made to homesteaders by describing the region to settlers as a New Canaan, where the growth of future streamflow and even rainfall that had never been documented, would make it suitable for the expansion of animal pasturing and farming, suggests a mythic geography of timeless bounty has replaced its actual conditions.

The mythic geography led to a rewriting of America’s irrigation infrastructure that in itself may be one of those pieces of infrastructure just no longer adaptable to extreme climate change. And as we face the scale of the national emergency of water shortages about to be triggered by falling reservoir levels, the crisis of using and recycling water, and the inefficiency of desalination plants of riverwater and groundwater, on which the world currently relies–and were predicted by the US Bureau of Reclamation back in 2003 to provide a “sustainable” solution to the dwindling water provided by the Colorado River, which had allowed the unexpected expansion of the settlement of western states. While desalination plants currently generate worldwide over 3.5 billion gallons daily, with 50 million gallons produced daily in Carlsbad, CA alone, desalination plants in one hundred and twenty counties, only half using sea-water, its energy expense justified as Colorado River decreased, promoted as a “sustainable and drought-proof water supply in Southern California” in an era of climate change, as if to calm our concerns at the dramatically decreased groundwater of western states.

Reclamation scientists assured the nation in 2016 of future recharge in the Upper Colorado Basin would offset temperature increases in their modeling scenarios through 2099, projecting basin-wide precipitation, the fears of the persistence of a mega-drought of extreme aridity with little recharge that may last decades has left fifty-sevens million living in drought conditions across the west according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, that has brought a new era of mega-fires. The thin blue line of the Colorado River is but a crack or thread coursing through a combustible landscape in this recent map of the expansion of unprecedented extreme drought in western states from National Geographic:

For all the disturbing and disquieting elegant if terrifying spread of deep red isotherms in Riley D. Champine’s map, the consequences of such exceptionally below-average levels of precipitation and aridity are difficult to comprehend as cumulative and deep in our nation’s history, as well as the effect of man-made climate change.

from PRISM Climate Group, Oregon Sate University

The utter saturation of this data vis of growing dryness of a region where rain far below previous norms fell forces the viewer to process an undue range of measures of aridity that they must struggle to process-if the deep orange and reds approaching emergency warning to suggest that surely a climate emergency is at hand. The absence of text in the visualization invites viewers to acknowledge they stand an eery remove of familiarity with an irrevocably landscape, posing unspoken if also unanswered questions about hydrological infrastructure in the Colorado basin, and greater west, that all but erases the geopolitical formation of this landscape–interruption of a rich color ramp at the southwestern border compartmentalize the large-scale decline in precipitation apart from national categories; but the danger lies in its focus on the economically developed north, more than the global south, as if it lacked adequate resources to prudently respond to groundwater shortages, but as an emergency for the developed world.

The focus of the climate emergency is on a large scale, daunting the possibility of individual response, but focussing on prudence at a local level, even if its scale is not defined, questions whether state politics can even resolve the intensity of the dilemma of declining rainfall levels below a thirty-year norm, a deviation on so broad a scale to be impossible to process save in local terms, but that omits the way the basin has been engineered as a site where groundwater now all but fails to accumulate, increasing the basin’s deep aridity more than the color ramp reveals.

The trust that Powell placed in his maps stand in sharp contrast to the “purple” coloration of regions of extreme heat introduced across western states to suggest so many “red-flag” warnings of excessive heat. In a year already tied with 2017 for receiving “excessive heat” warnings from the National Weather Service, already in early summer at a rate that is increasingly alarming, purple designates the need for caution when leaving air-conditioned environments, and suggests the booming of electric cooling across the west: the metric of a prediction of temperatures reaching 105°F for a two-hour stretch has paralleled the debate in Washington on infrastructure spending that suggest a similar disconnect that Powell confronted when he tried to describe the need for constraints on planning settlement west of the hundredth meridian in 1890.

Four Excessive Heat Warnings issued from late May 2021 have introduced yet a new color to prominence in National Weather Service maps, the new deep purple was introduced in weather maps in 1997 as a venture of the NWS into health alerts; rarely used in other weather maps, which in recent years have shifted from urban areas to large stretches of the nation, shifting from a use of red to designate high temperatures to purple to designate risk of triple-digit temperatures, especially in man-made surfaces like asphalt (able to rise to 170°-180° Fahrenheit–territory of third-degree burns–or cars which can rise thirty degrees above air temperature.

During the decade before 2003, the water-level of Lake Mead had begun to decline precipitously, inaugurating a historical decline that led it to fall to but 35% of its storage abilities. While the decline was not more precipitous than the two earlier declines in its water-levels in the reservoir from the mid-1950’s and mid-1960’s, the current decline in storage capacity of what is the largest reservoir of water in the United States has raised the unthinkable and unimaginable arrival of water cutbacks, as Arizona’s share of the Colorado River’s waters will be reduced by 7%, and Mexico–where the Colorado runs–will lose 5% of its share, in a scenario never foreseen in the dam’s history, but that reflects the increased aridity of the watershed from which the Colorado River draws. The decline to 1,075 feet in the reservoir’s depth that triggered the Tier 1 reductions in flow may only be a harbinger of the arrival of future Tier 2 reductions, should Lake Mead drop to 1,065 feet, as is expected in 2023, and raises the fear of a Tear 3 reduction, should the lake level fall below 1,025 feet, reducing the water allocated to western cities. In ways that the infrastructure of irrigating the Arid District of the United States could never have foreseen, the arrival of the driest period that the basin has ever experienced in 1200 years has brought longer periods of drier weather without rainfall that have reduced the riverwater that fills the reservoir.

The declining level of Lake Mead plunged below average lake elevation of 1173 feet, by 2003, in ways that should have sent alarms across the west, were we not consumed by a war against terror. The Bush administration’s attacks on global warming grew, questioning the science of global warming and the dangers of increasing aridity. But the disconnect between the expectation for irrigation by the farming industry and farming states was dismissed, with global warming and climate change, as temporary shifts that wouldn’t alter the landscape of irrigation or river flow.

Arid Region of the United States (1890); detail

Arid Region of the United States (1890); detail

![The back of this 1964 photograph reads, "Unvailing [sic] of new gas signs on I-89." An exhibit at the Vermont History Museum features historic photos from before, during and after the construction of the state's interstate highway.](https://www.vpr.org/sites/vpr/files/styles/medium/public/201311/interstate-signs-2.jpg)