Donald Trump’s most astounding victory–predating and perhaps enabling his astounding electoral victory as President–was to remap the mental imagination of Americans, and reconfigure proximity of the United States to its southwestern border in the public imaginary. The goal of this insistence is no less than a remapping of civil liberties, based on his insistence of the need for border security and constructing a Border Wall, and preferably doing so in all caps.

Condemning “obstructionist Democrats” are the party of “open borders,” and obstructing the work of law and order agencies such as ICE–the Immigration and Customs Enforcement–agents or his beloved Border Patrol, and for filling the national need for border security, and the project of building “the wall,” a super-border structure that would both prevent cross-border migration deemed ‘illegal.’ The construction of border psychosis is evident in the large number of Republican governors of states that have been elected two years into the Trump Presidency–

–as the question of “governing” states most all the southwestern border–save California–has created a new “block of red” that has been generalized to much of the nation, rallying behind the America First cry to defend borders, build prisons for immigrants deemed illegal, and work with federal agencies to apprehend such immigrants, denying their lawful place or rights to work in the United States. For much of this map of governors, now that the Republican party is increasingly the Party of Trump, reveal the uncertain terrain of the undocumented immigrant, and the massive circumscription or reduction of human and civil rights, as well as a fear of failure to manage immigration. Although current findings of sixty-nine competitive districts in the 2018 election include many border states–sixty-three districts of the total are held by Republicans before the election, a considerable number of the “battleground states” lying near or adjacent to the planned Border Wall, according to a Washington Post-Schar School survey—

–where calls for wall-building originated. The magnification of the border in the electorate’s collective consciousness was a gambit of electoral politics and staple of the Trump campaign for the Presidency, and it conjured the unprecedented idea that a single President–or any office-holder–might be able to shift the borders of the nation, or guarantee their impermeability to foreign entrance. The striking appeal of the border was not seen as a question of border protection but rather the construction of a wall, evident in the expansion quasi-tribal collective rhythmic changes at rallies, now repeated as if in a non-stop campaign. Although the focus of most buildup of the border has been to update existing fencing, the calls for fix-it-all border protection plans gained sufficient appeal to suggest a potential shift in the nation’s political terrain. Even though Donald J. Trump was, for practical purposes, a quite parochial perspective based in New York and Manhattan, and perhaps because Trump’s own expertise in national building projects was as limited as with working within the law, the project was first floated by the candidate as if from the sidelines of national politics, treating the project as akin to protecting a two-mile southbound side of the Henry Hudson Parkway in Manhattan, beside his pet real estate project, Trump Place, at 220 Riverside Drive, through an Adopt-A-Highway Project, and that the border wall was essentially the same need of securing . (Although the prominent sign was itself quickly vandalized to read “STOP TRUMP” as Trump won the Presidency, needing to be replaced, the return of the defaced sign promising the riverfront side’s maintenance was far less an act of good citizenship than a vanity act.)

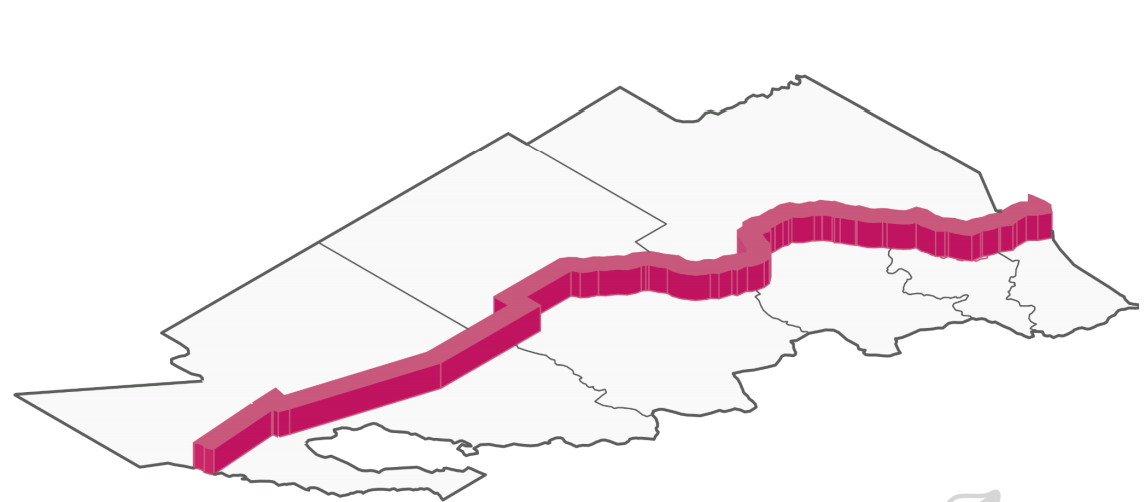

New York City limits the Adopt-a-Highway program to individuals, companies or organizations, rather than to political candidates and campaigns seeking publicity, but since the Trump Organization maintained the section since 2007 or earlier, it gained an exemption–and a tax write-off for its contributions to maintenance. And when he spoke to residents of the territory currently known as “America,” Trump seems to have treated the proposed Border Wall as an almost similar project of beautification, and a project of protecting what was his, in a proprietorial way that seemed to conflate his own identity and person with the country, as the current sign conflates his name with the Trump Organization, as his recommendations have contained as little familiarity with the site, scope of the project, or terrain, as many have noted, treating the construction of a continuous border wall as a detail designed to beautify the country, even though the border includes 1,288 miles currently without any pedestrian or vehicular fencing, gate or protection.

It almost seems that the proposed border wall had not been “mapped” per se, so much as it was a rhetorical promise for the sort of project Trump would like a President to do–and a project whose magnitude appealed to his sense of personal vanity. He praised the benefits of the construction of the wall as a need to “get it done” and imperative that responds to a state of emergency–a national emergency that sanctioned the suspension of existing laws. The emergency, as Trump saw it, was created by crime, gang violence by MS-13 members, who he has called “animals,” and a source for a loss of low-wage jobs. The acknowledgment of the need for the wall is virtually a form of patriotism in itself; recognition of the need for the country has become a way to participate in a new nationalism of strong borders–a nationalist sense of belonging that was opposed to the agenda of those unnamed Liberals without clear purchase on the geopolitical dangers and a failure to put America First. President Trump has argued that the “larger context of border security” necessitates the wall. Trump has come to repeatedly proclaims in his continued rallying cry stake out a new vision and map of American sovereignty, and indeed of territorial administration. Evoking a new tribalism in openly partisan terms, Trump even promoted with impunity the false belief that Democrats have united behind an “Open Borders Bill,” written by Dianne Feinstein–distorting the #EndFamilyDetemtion protests and “open borders movement” with an actual legislative bill. More to the point, perhaps,

The very crude geography and mental mapping that animates this argument is repeatedly a staple of Trumpian rhetoric. As if thick red ruled line could be drawn atop a map, Donald J. Trump has become the outsider political voice able, as a builder of vain monuments, to claim the ability to build a new structure able to replace existing border fences, and provide a continuous monument at endless concealed costs, without any acknowledgement of the people who have long moved across the border on the ground. The transposition of this tribalism of border separation into a partisan dichotomy has promoted and provoked an apparently Manichean opposition between political parties around the defense of the US-Mexico border, and the building of a Border Wall, in an attempt to define the differences between Democrats and Republicans around the issue of the defense of national safety.

President Trump has not only made immigration into a platform for his campaign and for his party: the stubbornly intransigent logic of Trump’s oppositional rhetoric has not only remapped the nation in mind-numbing ways. The fixation on the fixity of the border as a means to “Make America Great Again” erases the historical instability of borderlands in the United States, in its place projecting the image of fixed boundaries: the exact shift in the image of national territoriality seems a not only shift on the border, but a decisive replacement of an inclusive state. And even as Trump’s recent rallies are–as of September–still interrupted by “Build that wall!” tribal chants, leaving Trump to lie openly by claiming “The wall is under construction,” he reminds us of his need to evoke an inexistent barrier for which such intense desire has developed among his supporters that it is indeed a talisman by which America will, indeed, be able to be Made Great Again.

Continually crying about the urgent need for “building the wall,” even if it would be in violation of international law, is cast as a state of emergency which would reduce crime, the illegal presence of gangs, and existential dangers, and a promise made without acknowledgement of any who live outside America’s national borders, or any foundation in civil law. The promise to finish “building the wall” is cast as a simple question of volition, in almost pleading tones, that can be addressed to the entire nation as an ability to cathect and commune with the nation in simple concrete terms, no matter the distance at which they live to the actual border. It is an exercise in the geographic imaginary, in short, and a nearly ritualized deceit which Trump labors to sustain–as if a Border Wall could be conjured into existence as a leap of faith.

Identifying the dangers to the nation as lying external to it, the discourse of the wall have created a subtle remapping of sovereignty, on an almost emotional level. It focusses on the border, as an imagined line, rather than on people who move across it, laws or citizenship–placing demonized dangers as lying beyond the border and outside of the nation-state. The disproportionate focus that has been directed to the border–a distortion of attention that is epitomized and focussed on the desire for a continuous “border wall”–functions as a deeply dehumanizing way of remaking the nation, and remapping national priorities, around a fiction and a distinctly new discourse on nationhood, that is mapped by vigilance to the border, rather than to the course of law or to individual rights and liberties.

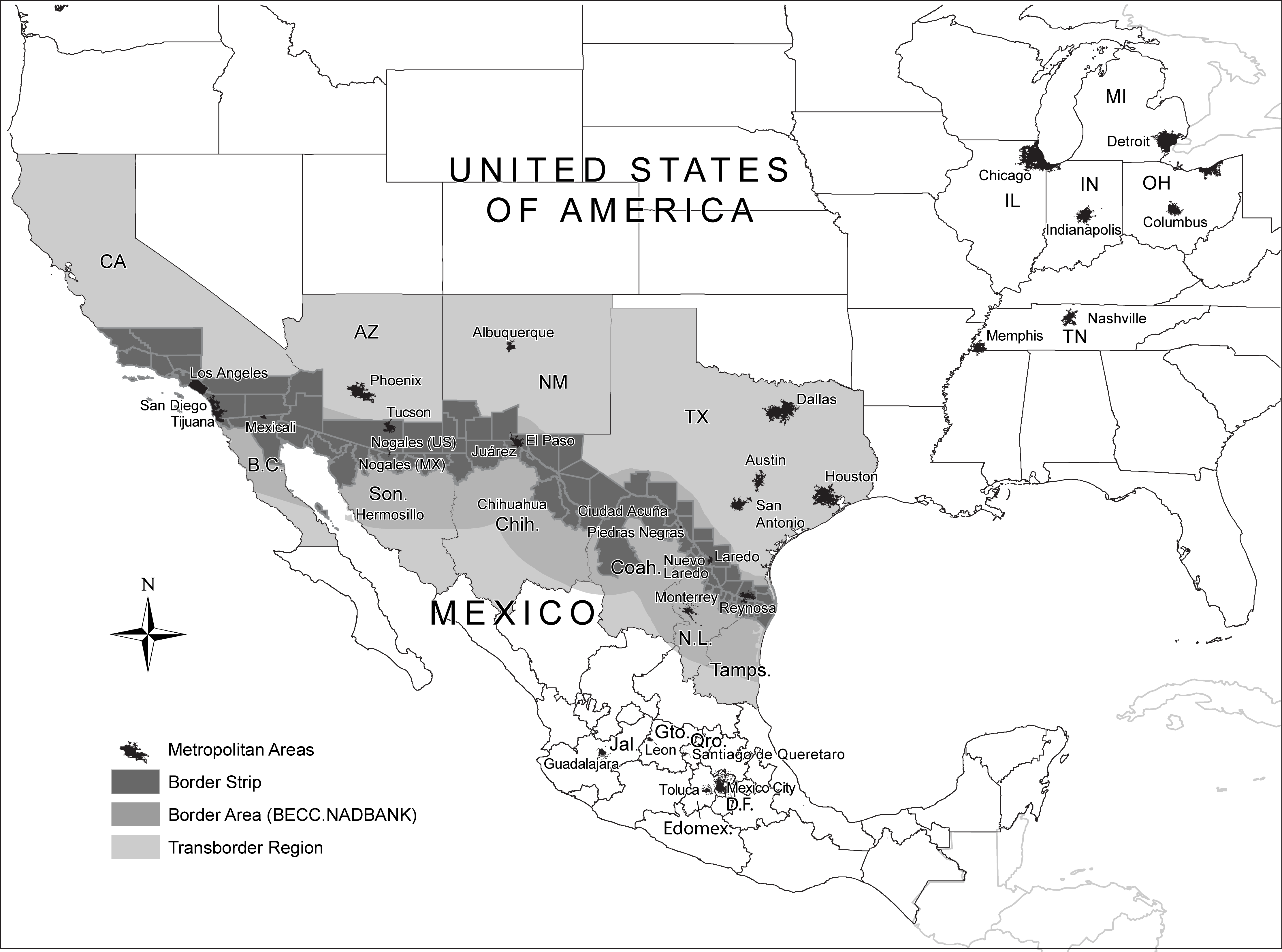

If maps provided tools for defining and symbolizing nationality, the conceit of the need for a border wall symbolized and also creates a notion of nationhood based less on ties of belonging than on boundaries of sovereignty that exclusion people from the state. Mapping is long based on ties of exclusion. But the focus of intense attention on stopping border-crossing and transborder permeability as replaced a logic of maintaining protections on equality or access to the law in the interior, shifting the attention of the nation of spectators by a deeply cruel trick of remapping the nation’s priorities. For the political rhetoric of creating a fixed border has effectively magnified the borderlands, through the terribly exaggerated violent pen-stroke of an Executive Order casting the border as a vital key to national security, and increase the proximity of the nation to the southwestern border in the political spatial imaginary.

Is it any coincidence that the same government to elevate the symbolic mapping of a wall on the southwestern boundary of the United States has reduced the number of refugees that it agrees to admit from war-torn lands, already reduced by half through executive orders from the number of refugees accepted in 2016, a limit of 45,000, to a new ceiling of “up to 30,000 refugees” beyond “processing more than 280,000 asylum seekers,” in line with the current 2018 count of barely over 20,900 by mid-September, but now for the first time less than the number accepted by other nations. Turning a cold shoulder to the crisis in global refugees is ostensibly rooted in a responsibility to guard its own borders, and “responsibility to vet applicants [for citizenship] to prevent the entry of those who might do harm to our country” and reducing grounds for asylum–even as the numbers of global refugees dramatically escalate dramatically world-wide–as if intentionally setting up obstacles for travel, and setting policy to openly prosecute any cross-border travel that was not previously authorized, and actively separating many asylum seekers from their families to deter them from pursuing asylum.

New York Times

Such false magnification of problems of “border management” has defined a disturbing and false relation to a deeply distorted image of globalism, of fuzzy borders, and not only apparent but intentional distortion–

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

–predicated on a false sense of national vulnerability, the urgency of greater border security, and the definition and elevation of national interests above global needs.

The rejection of refugees and closing of borders in the United States in the Age of Trump seems endemic: if the country resettled some three million people since 1980, when modern refugee policy began, this year, the United States for the first time fewer resettled refugees than the rest of the world–less than half as many as the rest of the world. The shuttering of borders is echoed in some 800,000 cases for asylum awaiting review, revealing a distorted view of the global situation that is mirrored by the blurred map behind Mike Pompeo’s head, and may suggest a global irresponsibility and deliberate disentanglement from world affairs. But it also suggests a deep remapping of the place of the nation in the world, not limited to the State Department or Mike Pompeo, of imagining the greater proximity of the borderline to the mental imaginary, and a privileging of so-called sovereign rights over pathways of human flow.

The promised wall planned for the border of unscalable height is a bit of a blank canvas designed to project fears of apprehension onto those who would confront it, a barrier to prevent motion across the border by unilaterally asserting the lack of agency or ability to cross a line that was long far more fluid, in a sort of sacred earth policy of protecting the nation’s territory along its frontiers–and refusing the extend rights or recognition to those who remain on its other side. Trump’s signing of grandiose Executive Orders as statements of sovereignty stand to reverberate endlessly in our spatial imaginary of the nation–while hardly warranted as a form of national defense, the border wall serves as a phatic act of sovereignty that redefines the function of national bounds. Indeed, in a country whose history was defined by the negotiation of borderlands, the assertion of the long unstable border as an impermeable barrier seems a form of willed historical amnesia, as well as the fabrication of a non-existent threat. The repeated indication of the southwestern border seems to seek to restore it to prominence in our national consciousness–and to see its security as being linked to the health of our nation–as if to make the current project of re-bordering an improvement of our national security–a process of re-bordering that is a performance of sovereignty, simultaneously symbolic, functional, and geopolitical in nature.

The symbolic of sovereignty is far more insistent than the functional, and the symbolic register is the heart of its political meaning, if the structural need is promoted as a response to geopolitical actuality.

For the Trump train, the wall is a “smart” redefinition of the nation, rooted less in the accordance of civil rights or guaranteeing of human rights, than the subsuming of law to protection of a nation that we imagine as under assault. If globalization has been understood as a process of “re-bordering,” where the lines between countries are neither so fixed or so relevant to political action on the ground, the border wall maps a defense against globalization in its rejection of open borders. The proposed construction sets a precedent as an act of unilateral border-drawing, or willful resistance to re-bordering, by asserting a new geographical reality to anyone who listens, and by cutting off the voices of those powerless to confront it. The deeply dehumanizing conceit of the border wall that was modeled in several prototypes deny the possibility of writing on their surface.

In ways that mirror the inflation of the executive over reality or the rule of law, the border wall serves to reinstate an opposition over a reality of cross-border migration. And Trump seems particularly well-suited and most at home at this notion of reordering, which he has made his own as a construction project of sorts, where he gets to perform the role of the chief executive as a builder, as much as a politician or leader of a state, and where he gets to fashion a sense of sovereign linked to building and construction, to a degree that the builder turned political seems to be intensely personally invested and tied. Although Trump has been keen to treat the notion of a border wall as a form of statecraft, the proposed border wall is all too aptly described as a an archaic solution to a twenty-first century problem–for it projects an antiquated notion of boundary drawing on a globalized world in terrifyingly retrograde ways. For while the construction of the border wall between Mexico and the United States was mistakenly accepted as a piece of statecraft that would restore national integrity and define the project and promise of the Trump presidency to restore American ‘greatness’ rooted in an illusory idea of privilege, but focusses on the privilege of entering the sovereign bounds of the nation alone.

The proposed wall maps a dramatic expansion of the state and the executive that continues the unchecked growth of monitoring our boundaries to foster insecurity, but creates a dangerously uneven legal topography for all inhabitants of the United States. For Trump and the members of his administration have worked hard to craft a deeply misleading sense of crisis on the border that created a stage for ht border wall, and given it a semantic value as a need for an immigration “crack-down” and “zero tolerance policy” that seem equivalent in their heavy-handedness to a ban, but have gained a new site and soundstage that seems to justify their performance.

While it is cast as a form of statecraft, the only promise of the proposed border wall is to exclude the stateless from entering the supposedly United States, and to create legal grounds for elevating the specter of deportation over the country. For the author of the Art of the Deal used his aura to of pressing negotiations to unprecedentedly increase the imagined proximity of the entire nation to the border–by emphasizing its transactional nature in bizarrely in appropriate ways. The result has undermined distorted our geographical and political imaginary, with the ends of curtailing equal access to due process, legal assistance, and individual freedoms. Acceptance of the deeply transactional nature of the promise of a border wall during the 2016 Presidential election as a tribalist cry of collectivism–“Build the Wall!”–as an abstract imperative, removed from any logic argument, but rooted in a defense of the land. The purely phatic statement of national identity was removed form principles of law, but offered what seemed a meaningful demand of collective action that transcended the law, either civil law, to affirm an imaginary collectivity of Americans without immigrants–and an image of a White America.

The imperative exhortations that animated Trumpism, as it gave rise to multiple other inarticulate cries repeated on Twitter and at rallies, based on lies and false promises or premises–“Lock her up!”; “America First!”–fulfilled a need for membership and belonging at the expense of others, in ways that subtracted popular opinion–and a false populism of the Trump campaign–from the law. By isolating the artifact of the wall as a sort of grail and site of redemption and religion of the nation, the tribalist cry “Build the Wall!” offered a false imperative that replaces reasoned discourse. Trump sees fit to treat as a basis for shutting down the government, accordingly, and indeed as a logic for a brand of governing that doesn’t follow the “terrible laws” of his predecessors. If the budgeting of a border was was earlier taken as a grounds to actually shutter the government, in 2017, the rehearsal of the threat to willfully “‘shut down’ government if the Democrats do not give us the votes [for] the Wall” once more unnecessarily equated the need for the border wall as a basis and rationale for government. The Manichean vision of politics of a pro- and anti-border party has been determining in creating a vision of the United States where sovereignty is defined at the border, irrespective of responsibility for the stewardship of the country: we built walls, impose tariffs, and end treaties, rather than acting in a statesmanslike fashion, and evacuate the promise of the state.

Much as Trump earlier called for “a good border shutdown” in the Spring of 2017 cast the wall as a part of his notion of governance, the new threat treats the as a bargaining chip able to equate with an act of governance–even if the wall as it is described seems less about governance at all. Trump rails against the passing of spending bills that do not foreground or grant a prominent place to the proposed border wall that he sees as a point of orientation needed for his constituents and that he still cherishes and his own introduction into national debate: attacking legislative packages about spending bills that don’t include special stipulations for border security or the construction of a border wall, threatening on Twitter to suspend governmental functions altogether without knowing “where the is the money for Border Security and the WALL in this reicidulous Spending Billaon the eve of the arrival of an apporopriations bill to the White House in the Fall of 2018, as his executive functions seem as imperilled as his grasp on the Executive Branch, of government: but the border wall retains centrality as the central promise he has made to the nation.

For the unwarranted and ungrounded promise to prevent the imagined threats of organized criminals, gangs, rapists, and drug dealers from entering the country–not that we lack many who are home-grown–through the border wall is a governance of exclusion, racial defamation, and promotion, which has little to do with governing at all. The apt characterization of the border wall as being an inefficient and irrational fourteenth century solution to a twenty-first century problem by Texas U.S. Representative Henry Cuellar-D of San Antonio–riffing on the suggestion of U.S. Representative Will Hurd-R of San Antonio as a third century solution to a twenty-first century problem ineffective to secure cross-border migration, and gesturing to the new tribalism that the project affirms. The imperative of the border wall is an insistence of tribalism over civil society, and a reflection of the increased tribalism we feel and see, but mostly feel and fear. Indeed, it allows these fears to be mapped against cross-border traffic.

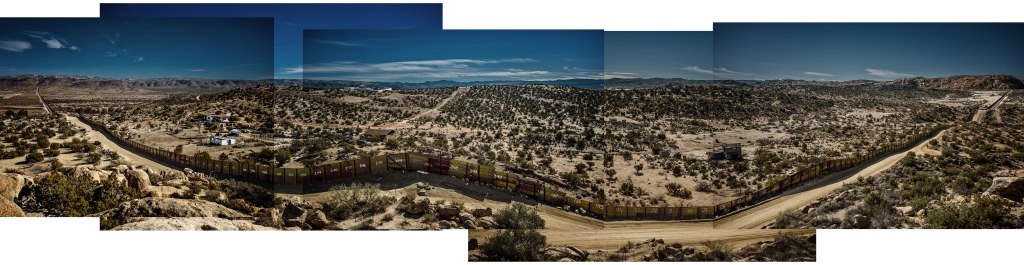

The imperative distorted and magnified what a border is and should be that shows little understanding of effective governance, and reclaims an old idea of the border–a fantasy, at root–that rejects the permeable nature of borders in an era of globalism, by rather affirming an imagined collectivity from which dangers–unspecified, but ranging from gangs to drugs to child trafficking–must be kept out. Although an underlying problem is POTUS’ spectacular lack of understanding of how government works, or of the law, which he has spent most of his life reinterpreting, it reveals his conviction construction contains crisis in essentially fascistic terms, building a structure that has little contextual meaning, but seems to impress, as a negative monument to the the state that is located in a borderland of apparent statelessness, but which Trump seems more and more frustrated at his actual inability to change what still looks more like a rusting twelve-foot tall Richard Serra sculpture than the imposing frontier promised America–

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (New York City, Federal Plaza, 1981-89)

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (New York City, Federal Plaza, 1981-89)

–but whose offensiveness disturbs, upsets and angers the viewer in a truly visceral way. Resting on the edges of our own borders as the basis for a larger “border complex” that seems to steadily expand, the border complex is not only a unilateral dictation of border policies, but a relinquishing of any responsibility of governance of the inhabitants of the nation, treating the definition of citizen/non-citizen as a primary duality never explicitly adopted as central in American politics and history, but assigning this division a centrality rarely so clearly geographically expressed as a question of national territory.

Even though the wall is a practical separation between territories, and an assertion of exclusive territorial identity, the imperative of the border wall that is repeatedly cast in urgent, existential terms, has presented itself in discursive terms both as a promise to the nation, in terms analogous to the Contract with America, that separated Americans from others, but which promised to strengthen Americans’ relation to the rest of the world. The increased proximity of the nation’s inhabitants to the border and border wall was asserted in the Trump campaign: the transactional status of the wall grew as a means to prevent multiple forces from endangering “our communities’ safety” as the border wall became a narrative plug-in for something like a promise of redemption from higher wages, untold economic dreams, and an acceptance of police security, as if a border can radically change the status quo of the American economy and local family safety. The proposal of the border wall continues to exist in a deeply transactional sense for Americans, as geographic relations to the actual border has been erased so thoroughly for the border, under the guise of “immigration,” to become a national platform of a political party, and a new model to define and remap America’s relation to the world.

1. The growth of global insecurity echoes profound anxiety at the realization that the lines of control of states cannot be so legibly or clearly mapped in the present moment, an anxiety it reflects by proposing to inscribe the border onto the landscape to make it visible to all and permanently fixed. The false promise of the border wall has been able to gain meaning on an individual level, allowing each to invest it with meaning and feel proximity to, independent of their own actual geographic proximity–even if the result is to silence the violence that the proposition of such a border wall does to the rule of law. If the long and energetic tradition of public mural painting that had origins in the Mexico of the 1930s provided a movement of energetic and energized monumental painting on open air surfaces in projects of humanity and considerable color. But the elevation of their pictorial formal power moreover asserted a new public identity of the nation for observers. In contrast, the artlessness of the empty screen of the border wall is an evacuation and denial of subjectivity: the defining characteristic as a concrete surface of the proposed border wall is itss inexpressive surface, its denial of common humanity, and its assault on the collective narratives that were the subject celebrated in muralism.

The wall stands as a sort of rebuttal to a muralist tradition of inclusiveness–embracing varied styles from Rivera to Siquieros to Orozco–through the assertions of a new artistic idiom by which to involve viewers in a revitalized broad civic life. The border wall is less an illustration of human will, than an image of the assertion of the reason of the state, understood less by legal principles than a tortured logic of exclusion. For while the extant border was a site of recuperation of muralist public art, the new border wall serves to impose the fixity of the border as a site that offers no place to the individual refugee, migrant, or legal immigrant, but a blank canvas that symbolizes the absence of individual autonomy or subjectivity to cross the transborder space. Indeed, rather than a collectivist statement of unity, whose monumental forms suggest a human struggle of collective identity and work, the construction of the wall is presented as a testimony of the need for an obstruction of the passage across the border to protect the nation, based on the knowledge and experiences of border communities, presented as a need to ensure and defend safety, national integrity, and economic power. Like the symbolic language of muralism offered a replacement for the common iconography of sacred art, in its assertion of public identity, the border wall presents itself as nothing less than a new religion of the state. While the comparison of the proposed border wall to the public panting of collective art muralism intended as an call to collective national consciousness and unity in post-revolutionary Mexico is a provocative comparison to the elevation of sovereign authority over the border by building a wall, the magnification of the border by the project and prospect of building a border wall has served to elevate a perilous image of nationhood, based less on ties of commonality, collective identity, or a rich historical legacy of individual involvement that muralists proposed than an unhealthy focus on the border as a site of danger, a frontier needed to be vigilantly guarded, and a threshold whose guarding substitutes for the defense of civil laws.

For in claiming to protect and secure the nation, the border wall becomes a performative exercise of the religion of the state, as much as it serves as a defense of political sovereignty. The authority of the US-Mexico border wall, in unintentionally, seems to stand as an open rebuke and rebuttal to the hopeful ideals and huge figures in images of dynamic abundance such as the monumental Allegory of California (1931) by which Diego Rivera depicted the rich bestowal of gifts on of a heroic mother earth figure of California, in San Francisco, whose monumentalism addressed individual viewers by an almost tangible allegory of local abundance —

–which set a basis, in one of the first large projects of the painter in the United States, set a basis for a new tradition of public moralism in western states. The interchange between active labor, earth, and a united countryside, if not a united narrative of nation, offered an optimistic personification of a monumental Gaia-like state, who, her resources liberated by workers, grants “gold and fruit and grain for all” of its residents, the revolutionary art of Siqueiros that heroized his country, or the twined histories of the Americas that José Clemente Orozco organized of tragic but truly epic historical scope of the Ancient Migration and the Migration of the Human Spirit, extending the collectivist spirit of revolutionary nation. Affirming a discourse of white privilege, indeed, rather than inclusion, the border wall is an imperative of religion of the nation that girds the border as a sight of defense, mapping the other as outsider in relation to the needs of the state, rather than celebrate the human subject as a force that is part of nature or culture. Rather, the proposed border wall seems to exist outside culture or nature, as an imperative to an endangered and threatened civility of the status quo.

The border wall erases the spirit of the migrant as it prevents migration, alleging compelling reasons of state and the new logic of the religion of the nation that replaces the law and any appeal to the law in its urgency. Rather than portray a giving sense of the heroism of migration, indeed, the wall interrupts any freedom of migration and transborder or transnational citizenship, reducing citizenship to a notion of territoriality and land, by bounding the terrain of citizenship and affirming a new ordering of space, and a political theology about the boundaries of the state, and the subtraction of citizenship or rights from the “enforcement zone,” “border zone” or denial of the rights of political representation or legal status for all transnational migrants in the “dead zone” of the borderlands. The absence in this zone of rights of the subject–the refugee, migrant, or itinerant subject–is paramountly defined by their statelessness and inability to fit between strict categories of sovereignty, rather than motion across states being celebrated as a point of access to the bounty of the land, or of the migration of the spirit as a celebration of the recuperation of a modern individual political identity. By demonizing the practice of migratory mobility, as if by a principle of “earth-first” binding of the nation, the border inverts the celebration of the human spirit

Jose Orozco, Migration of the Modern Spirit (panels 1 and 21) (Dartmouth University)

Jose Orozco, Migration of the Modern Spirit (panels 1 and 21) (Dartmouth University)

There was a resurgence of the discursive practice of the political messages contained in muralism as a form of public art in the resistance to decorating the border with monitory signs. Is the Border Wall not only a map, but also a rebuttal to this tradition, and indeed to the painting of public rebuttals to the wall through paintings and commemorations in the past? The absolute absence of any affect or visual address within the intentionally blank, sterile and almost industrial character of the wall seems in hidden dialogue or rebuke of an aesthetic of direct involvement of the viewer through its mute surface and corresponding evacuation or denial of individual human rights.

1. The triumph of industry, of rich historical cultures, or even of cultural conquest and revolutionary violence is compellingly replaced by the absence of any trace of human making or creation–or individual subjectivity–within the surface of the proposed border wall, which rather stands to deny individual liberty: in place of an aesthetics of broad political involvement, the denial of the presence of those on the other side of the border wall stand as a vicious act of disenfranchisement, and even a denial of human subjectivity. Indeed, if the heroic or epic narratives of monumental figures engage viewers in a pedagogic manner in muralist traditions by illustrating a narrative of nation, the proposed wall suggests a blunt lack of any national narrative, save the denial of the subjectivity of those on the other side.

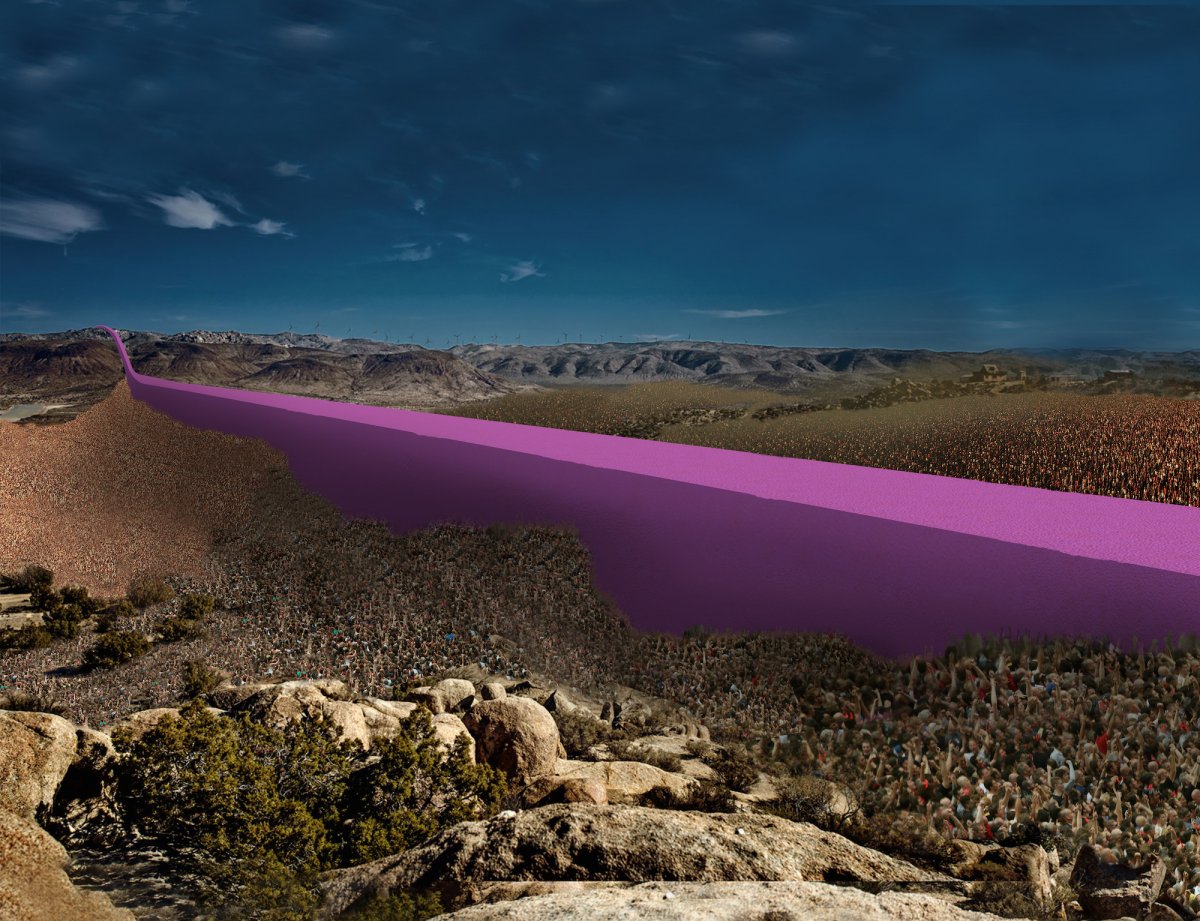

The talismanic nature of these “prototypes”–mock ups slightly removed the border–was meant to evoke the prominent place of the border wall, and to restore or reinforce in the psychological and mental imaginary of our new national space. Repeated throughout the Presidential campaign as if a mantra, evocation of “the promised wall on the southwestern border” has redefined a relation to the nation–and indeed been presented as a form of love for the nation–by the master builder who would be US President. And although the request for a “solid, Concrete Border Wall” in March, 2017–described as the President’s building medium of choice–became a secret state project, as “too sensitive” to be released by a Freedom of Information Act, by the Department of Homeland Security, designed to meet demands to be impossible to tunnel under, and impenetrable to sledgehammers or other battery-operated electric tools for at least an hour, seem something of a simulacrum of the state that is both all too obstructive for actual migrants and cherished by many Americans, and prevents the transformation of previous parts of the border wall to public sites of commemoration–remembering the suffering of those who attempted safe passage, or indeed of mural-art that has attempted to assert the fluidity of cross-border transit.

Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images/Palm Beach Post

Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images/Palm Beach Post

–or that try to imagine the perspective that the future of the border wall will create for the migrant subject who is excluded from hopes of cross-border transit.

Even as the proposed US-Mexico border wall is presented as girding the nation against multiple dangers, the new bounding of the nation that prevents any intervention or artistic transformation of the wall, by stating its own absolute authority as a re-writing of the nation. The permanence of the models of the wall seem not so tacitly or subliminally suggested by the physics form of one of the mock-ups, which references the form of a flag, as if to suggest its similar permanence as can image and record of the nation, and proof of the nation’s continued existence, as if the nation could not exist without it: indeed, the flag-like proportions in mock-ups suggests a new flag for the nation. As the promise of the border wall has allowed such a range of audiences to cathect to the national boundary–a sense that was perhaps predicted in the repainting of a section of the existing border wall of welded metal and steel near San Diego–the very site where a caravan of Central American migrants would arrive where they were taken by President Trump as an illustration of the fear of the dangers of cross-border immigration–the wall suggested a sort of surrogate for the purification of the country, restoration of the economy, and an elevation of the minimum wage, wrapped into a poisoned promise of poured concrete.

It was no surprise that a group of Mexican-American veterans chose to paint a segment of the older wall near Tijuana in 2013 as if a mural that mirrored the use of the inverted flag to stage a signal of distress to the nation: indeed, the deported former navy who chose the wall as a site for a cry of emergency and national belonging: teerily prescient of the flag-like nature of the mock-ups, sections of which uncannily resemble a vertically hoisted flag, the wall sections painted by disabled veteran Amos Gregory, a resident San Francisco resident, who completed the painting with twenty deported veterans, recuperated the tradition of moralism to create a new story of the wall, where crosses of dead migrants replaced the stars of the stars and stripes, as if to appropriate the wall to a public narrative of nationhood.

The inverted flag that a group of U.S to paint the flag, but expressed shocked at charges of using an iconography “hostile toward the United States of America,” and chose the inverted flag as a distress signal–to show honor to the flag, and to “mean no disrespect” to the nation, but to raise alarm at its policies. His dismay when asked to remove the mural by US Border Patrol sent a message of censorship as an attack on freedom of expression; Gregory incorporated crosses to commemorate on the wall the migrants who died seeking to enter the United States for better lives and livelihoods, undermining the ideals of freedom he cherished. By placing their memory on the wall, he sough not to dishonor the flag, but to use it as a symbol of extreme gravity that respects its ideals–and the etiquette of flag display, in the manner future protests at the marginalization of migrants seeking asylum as they enter the United States at its border zone.

The current mock-ups suggest, if unconsciously, an actual evacuation of patriotic ideals. The MAGA President might have been conscious of how several of the so-called prototypes suggested a flag turned on its end, as if in a new emblem of national strength–

–as if to offer them a new symbol of the nationalism of a new nation. The segment of this prototype recalls the flag suspended vertically, as on a wall or over a door, above the border that has become a prominent character in the current President’s Twitter feed, and evokes the ties between terrorism and immigration that Trump has long proposed the government recognize and acknowledge, despite having few proofs of these connections, acting as an assertion of the implied criminality of all immigrants who do not cross border check points by legal protocol, no matter their actual offense.

1. The compact about the construction of the border wall has, against all probability, become the latest in faux populist promises since the Contract with America to pose fictive contracts of illusionary responsibility and reciprocity to the democratic process, and have provided new tools of assent. At the deepest level, the wall exists in this discourse of urgency not as a proposition, but as an actuality that need only be built, and cannot–or need not–be mapped, less the practicalities of consequences of its construction by acknowledged. The border wall, viewed in its prototypes, is somehow an expression of the unmappability and existential quality of the border wall that Trump wants; alien from its surroundings, and existing as an obstacle to entrance, it is a redefinition of the border from a site of passage to an obstruction. The affirmation of the border as a “real border”–which Trump repeatedly ties to the status of the United States as a “real country”–seems to mean an impassible border, which lacks any negotiation, but is recognized as an element of the nation that needs to spatial location but acts to strip all outsiders of their their rights. All attempts to map the border as a spatially situated place seem to stand as a challenge to undo the imperative of the wall’s construction.

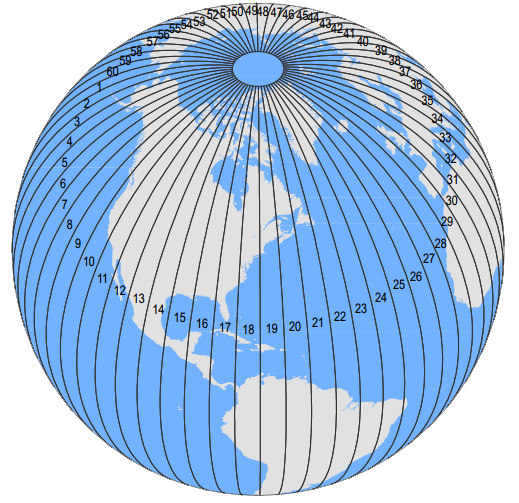

The faux consensual ties with the electorate perpetuate a fiction that a democracy runs on the contractual obligations between a government and populace, but have early been so focussed on geographically specific terms. But in an age of anti-government sentiment, the icon of the wall has become an effective icon of describing the ineffectiveness of prior administrations, and an iconology embodying the new role of the executive in the age of Trump: in an age of global mapping that seems to disrespect and ignore borders, we imagine migrants moving across them with the aid of GPS, or Google Maps, empowered by the location of border check-points on their cross-border transit,–

Google Maps

Google Maps

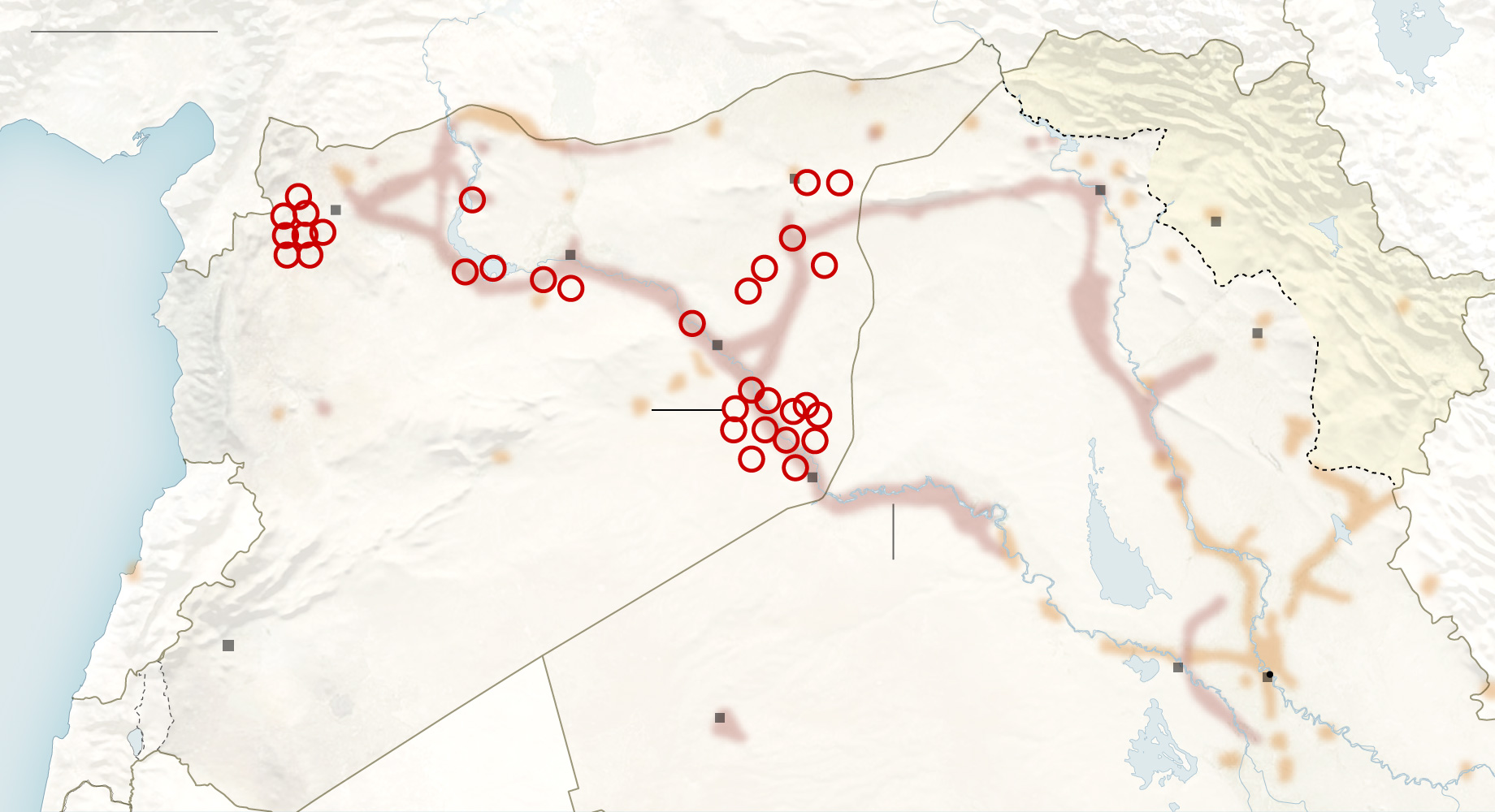

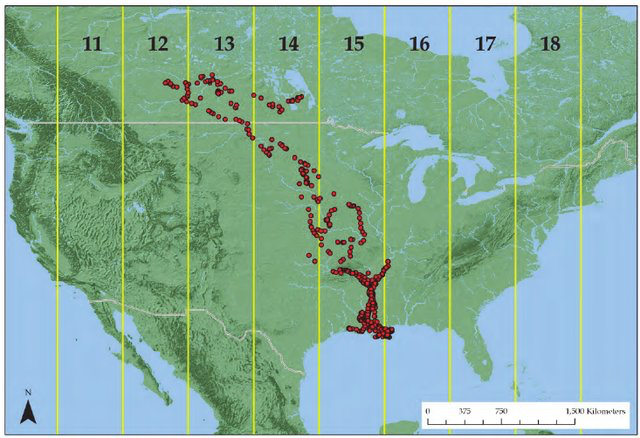

In a rejoinder to these fears, the proposed border wall would map a continuity among the stations in different sectors administered by the US Border Patrol, already strikingly dense, and apparently easy to connect by a solid wall–

from

from

Armed Conflict Survey, 2015

Armed Conflict Survey, 2015

November 1, 2016/

November 1, 2016/

Wikipedia

Wikipedia