Before a barrage of bombs began to fall on Ukrainian cities from Kyiv to Kharkiv, newspapers of record predicted that “Days of whiplash developments made unmistakable the volatility of a crisis that American officials fear could lead to an assault by one of the world’s most powerful militaries against Ukraine, Europe’s second-biggest country,” as artillery exchanges grew in the Eastern provinces. Fears of Russia staging a unilateral invasion of the nation grew as “a development that Europeans never thought they would see,” alerted the New York Times, challenging if not undermining Europe’s–and NATO’s–expansion of geo-strategic alliances in recent years. But the nominal accusations of an expansion of NATO has blurred, to be sure, with the accusations of the persecution of ethnically Russian populations in eastern Ukraine in the current charges of waging a war of “de-Nazification.” They nationalistic cry rallied faith in a Russian homeland that seem to be a reaction to the processes of globalization against which Putin’s right wing allies–from LePen to Donald Trump–have recently railed against.

If rooted in fears of preserving a lost Russian empire, an ethno-state eroded by the breaking away of Soviets, the recasting of Donetsk and Luhansk as “People’s Republics” in eastern Ukraine hearkens back to the soviet history in which Putin and Co. were molded, a reaction to by military formations in the ear of the Trump Presidency, as pincers around eastern Ukraine, long before the current invasion of Ukraine began–a show of force of tanks, artillery, and rocket systems poised to illustrate the porous nature of any nominal borders when it came to the old Soviet Union. For as if in refusal to let the post-1989 territory emerge as a liberal state–or a separate state–the resurgent ethno-nationalism of “preserving” or “protecting” Russian speakers from allegations of Genocide offered an Orwellian Newspeak by a totalitarian state George Orwell saw as critical tools to rationalize ongoing war, death, and cast as “subversive” the very concept of free will.

The dramatic massing of Russian soldiers on Ukraine’s border in the Spring of 2022 seems to have been engineered to question that border’s status as a guarantee of sovereignty. As if to mirror but were unlike the erosion of borders in globalism, however, the massing of troops was a display of Great Powers doctrine on the part of Moscow, echoing the emphasis on the expanded range of supersonic bombs that Vladimir Putin had foregrounded in his announcement of the range of nuclear bombs in 2018 when he announced to the world a new arsenal of “invincible” nuclear weapons before a video graphic that imagined warheads hitting the United States. The trumpeting of the apparent invincibility of Russian armaments that Putin suggested in a dramatic tableaux of Russian military dominance–

The bombast was reprised in reduced form at a local level as Russian troops massed an unprecedented show of force on Ukraine’s border in the postwar period. Their congregation seemed to firm up Russian power after Putin had dismayingly, misleadingly and perhaps self-servingly asserted was an existential threat to Russia more than an expansion of a defensive alliance. And if Putin later, after the invasion began, argued with duplicity “What is happening in Ukraine is a tragedy–they just didn’t leave us a choice. There was no choice“–the invasion that sought to reunify the old soviet that had become a breeding ground for liberal reforms was not really about the expansion of NATO, but the consecration of the boundaries of the old USSR, and the absence of “true boundaries” for Russia in the old Soviet bloc.

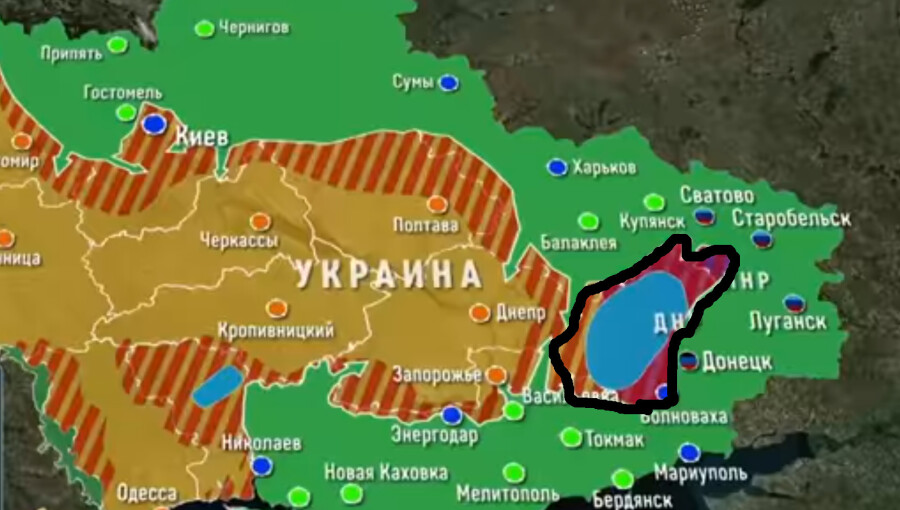

The border was already being denied in the massive show of force that massed in the Republic of Belarus, that old Soviet, in the larges mobilization of troops in postwar Europe. As 90,000 troop joined an assembly of 100,000, equipped with tanks, anti-aircraft guns, fighter jets, and armor on the area where the borders of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, the show of force seemed to erase any sovereign border or notion of independent sovereignty. The apparent focus of Ukraine’s forces in the west, was oddly paired with the positioning of Russian troops in the vey same positions they used to confront potential defensive strikes against NATO, as if the missile launchers and military planes by Ukraine’s borders were posed to move against a nation that had been hoping to join NATO, if with some American encouragement, and the readiness to gloss that idea as a tactical aggression that merited an immediate military strike. The fears of a move outside of Russian military and geopolitical influence fed a specter of mobilizing these troops again. This map, from almost a decade ago, suggests the long-standing tenuousness of these borders, and the readiness Moscow had long felt to remove their pretense.

March 1, 2014

The robust show of force that established its theater of influence and refused to be hemmed in by borders of sovereignty. Whether they reflected Vladimir Putin’s beliefs, or, far more likely, offered an excuse for military mobilization of such unprecedented scale against a country with few natural or geostrategic defenses, global media disinformation were filled, at the same time, with the fake news, amplified on Russian news and RT, calling NATO and Ukraine as threats to Russian sovereignty, even as Ukraine’s sovereignty was effectively bracketed and taken off the table, a pretext for Russian escalation whose size recalls imperial wars of the nineteenth century. The refusal of Viktor Orbán of Hungary to let military aid flow to Ukraine through Hungary, a reflection of his nation’s considerable dependence on Russian natural gas, and Budapest’s invitation of for the Moscow-based International Investment Bank, or IIB, whose founding ten member states of 1970 reflected the political geography of the Cold War–was relocated to Budapest in 2019, was long a conduit for Russian intelligence, and is led by the son of a KGB official formerly stationed in Budapest. As Central European states from the Czech Republic to Romania accelerated their exits from in response to the invasion of Ukraine, Orbán threatened Russia’s aggression would overflow far beyond Ukraine and charged opponents had designs to “drag Hungary into this war” and “make Hungary a military target” to his political advantage in a recent electoral campaign.

The vivid reassertion of a Cold War political geography haunts Central Europe today. Aggressive military moves one-upped the seizure of the Crimean peninsula and eastern Ukraine, but the massing of military presence outside Ukraine’s borders ramped up the abilities for invasions that would create a potential impromptu blitzkrieg that would leave, Russia hoped, a stunning memory of Ukraine’s limited sovereignty. Indeed, the clarity with which Volodymyr Zelensky has urgently asked the world to recognize Russia’s hopes to “break our nationhood” is evident in the way Putin’s ally, Belarusian President Lukashenko, addressed the Parliament as a schoolteacher, informing them of the splitting of Ukraine into four theaters of operational command, and several arrows that showed the planned movement of troops into Ukraine,–

as if the nation that borders Belarus were not really secure, and the plans to use Belarus as a platform for staging an invasion was indeed already underway. The map used as a basis to lecture Parialiament displayed on state television was a “misunderstanding,” authorities claimed, but the pink arrows that staked out the routes by which Russian troops would invade Ukraine already affirmed the absence of Ukraine’s defensible borders; the pointer he used as a school-teacher to describe the impending display of Russian power as if to replace the actual Belarus President-elect, since 2020, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the former English teacher in Minsk who replaced her husband, Serghey, leader of an opposition Lukashenko had jailed. While Tsikahanouskaya has long left Vilnius, but resists the Russian-based orthography “Svetlana Tikhanovskaya” and Lukhashenko and his security forces relied on Putin for power, Tsikahnouskaya is a government-in-exile who long pinned her hopes to Joe Biden’s victory.

The threat of a cross-border movement of military troops were part of a theater of power and destabilization that had been central to Russian hopes to consolidate an old bloc. Beyond its hopes to affirm its presence in Crimea and around eastern Ukraine, now used as launching pads for an invasion in the above map, beyond countering an expansion of NATO, the hope was to drive fear into the old bloc and gain support from nominally democratically elected allies, from Viktor Orban in Hungary . Russian air force had flown nuclear bombers with missiles of expanded range over Poland’s borders, in November 2021, and in the airspace of Belarus, contesting the ability of NATO forces to move to the east and protecting what it saw as its crucial sovereignty over energy transport to central European states from Hungary to Poland, once part of the old “Soviet bloc.”

As Orbán posed with Hungarian generals and tarred his opposition with trying to drag the nation into war with Russia, Russian television news by March, 2022 remapped a nation in Cyrillic whose eastern half seemed to have collapsed, after Russia taken control of the airspace, with cruise missile strikes on airfields, fuel depots and infrastructure, even if the capitol had not fallen–hoping Ukraine’s inhabitants might decide to accept Russian suzerainty rather than continue war. Perhaps the capture of “territory” in the Russian imaginary that extends through the Dnieper River would provide the symbolic imaginary that Putin seeks to hold, although the ability to “hold” the lands that Russian forces have terrorized and flattened will be steep, even in the steppe lands of Ukraine’s Trans-Dniepr where about a dozen brigades–some 60,000 men–of Ukraine’s best troops are located. The image of Russian control of the Trans-Dnieper symbolically “restored” to Russian suzerainty ethnic Russians, promoting the illiberal logic of an ethno-state reducing Ukraine to a rump and cast Kiev as a border town, wiping Ukraine’s old border off the map.

The result would be to reduce the sovereignty of any Ukrainian “state” to a permeable polygon.

The initial mobilization of increased materiel that the Russian government had invested from hypersonic missiles to potential nuclear torpedos, eager to be installed in the Black sea and stationed in increased proximity to much of Europe, whose energy independence was already steeply compromised by their acquisition of and dependence on Russian oil and gas.

Ukraine became a “red line” to which Russia wanted to gesture, and indeed prominently fix on the map, as visibly as the US-Mexico Border Wall, as the Kremlin repeatedly warned the “red lines” on its maps could not be ignored by any “broadening NATO of infrastructure on Ukrainian territory”–as if the defensive alliance were intended to provide a challenge to Russian sovereign authority.

To be sure, the challenge of Ukraine’s hopes for its own sovereignty were already unprecedentedly threatened by massing from 2020 of military to the east within Russia–

Ukrinform, July, 2020

–far, far beyond the occupation forces that were already located in occupied eastern regions of Ukraine, and which completed a possible pincer operation simultaneously invading Ukraine from multiple borders and sides, as it tacitly pointed fingers at Washington, D.C. for encouraging Ukraine as an upstart by a growing escalation of force.

If Moscow shifted troops to Ukraine’s border to prevent Ukraine from becoming European, or, more accurately, to prevent its development as a democratic liberal state, the demonization of an imagined “expansion” of NATO eastward was imagined as an invasive virus, and a threat to an imagined Great Power status not of Russia, but the Soviet Union, and indeed Russian empire. Yet one can only understand the violence of the massive attacks that were to be unleashed against Ukraine as a last gasp of empire, an in a late imperial rationality of defending the imagined sovereignty across borders, boundaries, and ethnic identity, at a time when Ukraine was a part of the USSR, as much as a satellite states, and “satellite states” were not mapped by GPS satellites but rigid lines and shades of red, whose borders were more nominal than meaningful.

We risk presenting the struggle for Ukrainian independence in the narrative of great powers, however, overlooking the deep threats of the denial of Ukraine’s architecture as a nation-state. The great-power narrative unhelpfully Vladimir Putin as a chess grandmaster whose strategic planning were not thuggish and indecorous land-grabs of illegality. By annexing Crimea, provoking uprisings in the eastern Ukrainian provinces of Donbas–Donetsk and Luzhansk, or carving out a “confederation” made of breakaway “republics” of the evocative name Novorossiya, Putin had made Ukraine less a state than a mythic geography, conjuring it as part of a Greater Russia of Romantic cast. If WInston Churchill suggested with despair that Russia so opaque to be was a riddle, wrapped in mystery, wrapped in an enigma, a belittling metaphor of evoking the Beriozka doll, the alleged anger at Ukraine joining NATO mapped by an imperial imaginary of Russia tied to Ukraine, and to the seat of the historical Kievan Rus’, long sacred to the Orthodox church, wrapped in the historical Warsaw Pact, wrapped in the hopes for a future petrostate, but haunted by the fear of any recognition for a neighboring liberal state and its political autonomy

Putin seemed to have abandoned Novorossiya as a stillborn project by 214, but continued to meet with cronies in Gazprom over maps. We cast Ukraine as a chessboard, not a nation, but the Russian hostility to the NATO membership of Ukraine openly ignores the fear of recognizing Ukraine as an independent state. Ukraine’s reduction to an ethnic battleground in a Cold War geopolitical landscape led the imagined “Union of People’s Republics” to force Ukraine back into a new rebirth of the old USSR where Vladimir Putin was a lieutenant colonel, the “New Russia” foreign to any maps returns Ukraine to a Russian “sphere of influence” more nostalgic than actual, but with its own secure lines of transporting natural gas into the old Eastern bloc, and deep ancestral ties to the old empire whose imaginary remains stubbornly slow to fade. While Russian negotiators told Americans that they didn’t plan to invade Ukraine at all–“There is no reason to fear some sort of escalatory scenario” rebuffed Sergei Ryabkov, Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister in early January–demands not to allow Ukraine into NATO were an apparent denial of its sovereign status, long before bombs rained indiscriminately on civilians, including hospitals where doctors were forced to heal wounded Russian soldiers at gun point.

And despite

Despite notoriously low participation in the Crimea’s “referendum” on rejoining Russia–a vote estimated by Russian President’s Human Rights Council, per a leaked report, at a measly 30%–the annexation of the region was accepted, rather than risking open conflict, despite military presence of Russian soldiers in the Crimean peninsula. The deep danger for viewing Russian aims in Ukraine in a “Great Powers” lens grows almost a decade later, imagining the division of Ukraine into sectors that resonate with a Cold War paradigm, is that it ignores the largest fear of a liberal state on Russia’s borders.

Ukraine was compromised as a nation-state, long before its borders were threatened with troops. Divided not by a Civil War so much as by Russia militarily occupying Crimea and significant parts of its east where Russian language remained dominant. The Russian government had recently fast-tracked nearly 800,000 passports, as part of a policy of “passport proliferation” that seemed to have aimed to restore a reduced Warsaw Pact by issuing a slew of some five to ten million passports to the diaspora of Russians from Georgia’s South Ossetia, Moldava’s Transnistria, and Ukraine’s Crimea and Donbas–a sort of “buffer” of peoples that Russia decided it would decree to expand the boundaries of state security, and even military intervention–both to address a growing demographic crisis by 2019, and to cement an ethno-linguistic identity as a regional foreign policy for annexing Crimea and Donbas by 2014–

effectively exploiting the division between “Russian” and Ukrainian language to undermine the hopes of a nation-state. While the intense violence since directed to Ukraine may have no logic, its undermining of Ukraine’s borders is an undermining of a project of sovereign status in favor of the idea of a “Russky Mir,” or a “Russian World” that reassembled a mythic Russian collective that denies the existence of Ukraine as a nation unable to be wracked by civil war.

As the government of Russia has responded to the threat of the expansion of NATO by a policy of increasingly ‘passporting’ former subjects of formerly Soviet territories, time past was folded into time present and the future, and time future projected as present in time past, and all of time eternally present in the invasion of Ukraine, in a historical pastiche of postmodern proportions. T.S. Eliot references aside, the burning of Kyiv and many wonder if Russia’s end was not lying in its historical beginnings, as the fixation on the political identity of Ukraine suggests Putin’s plans to affirm his historical legacy as reversing the dissolution of the Soviet spheres of influence by recuperation of the mythic imaginary of the historically Russian areas of the Kievan Rus’ beyond the early restructuring of Crimea. And if Putin had already commissioned a new global atlas of the world that will adjust the possibly problematic names of cities from Ukrainian to Russian toponymy, so that the resulting product will better rerlect “historical and geographic truth” by ensuring, as he quite aspirationally told the Geographical Society of Russia, and “preserve Russia’s contribution to the study of the sciences and the planet, lest they vanish from the map from the South Pole to Crimea, pushing back on how some nine hundred Ukrainian cities and towns shed previously imposed commemorative place-names since 1990, once honoring Marx, Engles, Lenin, or the leader of Russian Secret Police, Felix Dzerzhinsky, under auspices of Ukraine’s Institute for National Memory, a Gorbachev-era forum dedicated to “decommunization” and reckoning with the Soviet past: 946 towns and cities were slotted for renaming by 2016.

Yet if such linguistic maps are argued to be an explanation of civil strife or sovereign combustability of Ukraine, in ways that justify the intervention of Russia in Ukrainian territory on ethnic grounds, the ethno-national logic of Putin’s justification of meddling in Ukraine’s bounds and sovereignty rests on the deep commitment to “moral values rooted in Christianity and other world religions” that Putin has argued the “Euro-Atlantic states have taken the way which they deny or reject,” linking the Russian Orthodox church to Russian government and moral values, extolling the icon in early modern ways. Even as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church metropolitan Epiphanius I has likened Putin to the Anti-Christ or that the “spirit of the Anti-Christ operates in the leader of Russia,” the invocation of orthodoxy as a basis to justify Russian expansion plays on ethno-nationalist grounds akin to the proliferation of passports to discredit the West in Eastern Europe in ways that have only grown since the possibility of NATO’s expansion eastward: if only in 2018 did the Ukrainian Orthodox Church split from the Patriarchate of Moscow, to which it had remained subservient since 1686, the religious split reveals deep tensions in redrawing the map.

While the European Union had offered the possibility of membership to Ukraine and Georgia back in what seems the other world of 2008, dangling the prospect of “Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO” of both states as an opportunity that was on the table. The promise presumed eastward expansion of a North Atlantic Treaty Organization beyond Poland and Hungary, to Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, as well as Slovakia and Romania able to pick up the peaces of the disbanded Warsaw Pact. Russian reaction to Ukraine the affirmation “these countries will become members of NATO,” was perhaps far less a “whiplash” than the culmination of Putin’s immediate warning of “most serious consequences of European security” would provoked an unprecedented “direct threat” of almost existential terms, that would make Ukraine not a “border” of Russia–it gained its name as a “borderland” of the Kievan Rus’–but, in ways by which Putin seems to have become increasingly haunted, with its own identity as a nation-state.

The concerns of processing the presence of some twenty Russian or Russian-allied military forces around the nation’s border forced us to try to an intractable geographical impasse of Ukraine’s place in Europe, or, as Russia insists, the periphery of Russian sovereignty–if not the sovereignty of the borders of Ukraine. As Ukraine tried to shift its status as a borderland in Cold War maps of old, and the new security structure of a European Union, the world confronted the emergence of a New Cold War, haunted by the division of separate spheres of dominance.

1. The public perception of an “inflection point” of the eastward expansion of NATO resuscitated a Cold War geography: yet can the fixity of these old spheres of influence fully explain the massing of troops on Ukraine’s borders? To be sure, right-wing American commentariat, obsessed over the dangers of NATO expansion and eager to see American disentanglement from Europe, openly argued that NATO expansion was the precipitating reason for broad military invasion that would kill civilians and destroy hospitals, schools, monasteries, and villages. But the illegality of the invasion that only led Russian state news to recycle Tucker Carlson’s buoyant defense that the Russian invasion is “only protecting its interest and security,” was as popular among Russian government as his asking viewers “how would the United States behave if such a situation [of placing military bases] developed in neighboring Mexico and Canada?”, evoking a Cuban missile crisis playbook of the past. Carlson’s isolationist pro-Putin rhetoric imitates Russian government in subsuming “Ukraine” as a nation in the long memory of spheres of national influence, in which eastward expansion of NATO boded a redrawing of a global map–and ignored the range of missiles, radar systems, and missile interceptors that have already been deployed in the European theater by an expanded NATO since 2019–all exclusively purchased from American contractors and weapons systems manufacturers, long imagined as a “missile shield” over Europe.

The demand for “security guarantees” Russia had demanded from Western powers as NATO and the United States since before December has lead, however, to the placement of the Ukraine conflict in a Great Power narrative, as if this were at all informative. Yet the expansion of military defense systems across Central Europe belies the continued finger-wagging of right-wing political scientists like John Mearsheimer long wagged their fingers at NATO expansion in the face of a great power geography.

The Times found Russia’s unprecedented massing of troops along the northern border of Ukraine risked “Reigniting the Cold War Despite its Risks” (January 20, 2022), describing a global power struggle as as if Ukraine’s independent sovereignty was not a crucial puzzle piece in the dilemma. The headline trumpets fears of a new Cold War in Europe, over thirty years after the original Cold War had ceased as the primary lens for geopolitical security, triggered fears of a familiar tinderbox on the borders of Russia, as its leader invoked a narrative of border security and national vulnerability to invade a separate sovereign country. Indeed, the possible rejoining of a Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which the United States abandoned in 2019, accusing Russia of long violating the terms of a treaty signed thirty years ago, in the Cold War world. If these missiles were long seen as a basis for European security, Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces, missile deployment is a smokescreen for deep fears of an open democracy.

Even if Ukraine, once in the Warsaw Pact, shares a border of over 2,000 km–about the span of the United States’ frontier with Canada on the 49th parallel from Washington to Minnesota, or, alternatively from New York to Chicago. But the border was less the point, or even its length, than the pipelines that allow the petroleum state to reach other members of the old Warsaw Pact, leaving them dependent on Russia for gas.

As much as the expansion of NATO, however, the possible of claiming Ukrainian sovereignty of its borders was denied by the troops clustered along Ukraine’s borders who menace crossing into its territory on world view. The massive stationing of Russian and pro-Russian troops on the border seemed something of a performance piece, and something of a threat to end Ukrainian’s European aspirations.

Global conflicts along borders have long been dominating the national news, but all of sudden the edges of borders are up for debate as a debate that contrasts national identity to spheres of influence inherited from the Cold War. The presence of some 190,000 assorted troops of the Russian Federation on or near to Ukraine’s borders is a power play, committed to wrench the region from NATO, if by asserting, as Vladimir Putin has claimed, Ukraine is not in fact a state. Fears of the destabilization of a Cold War geography seem to lie far more deeply rooted in the calculus of Vladimir Putin, who had entered politics after over a decade as a Cold War spook, two years before the declaration.

The characterization of Putin the intellectual image of the “chess player” looking at long-term national strategy seemed less in evidence than attachment to the borders of the Cold War bent against the formation of a liberal state. Putin’s preposterous claim that Ukraine was only born as a state as a geostrategic part of the USSR is not only preposterous, but deeply haunted, one might speculate, by a lost geography of the Kievan Rus’, and a sense of preserving the former Soviet Union from the autonomy that its individual states, or soviets, were allowed–and indeed the danger of according such privileges to regions as Georgia and Ukraine, each of which had been offered a partial promise back in 2008 by NATO that they might join the security organization, after Putin had already refused to allow Ukraine to gain such a degree of independence or sovereignty as a state.

The survival of that promise by December 2021 was deeply troubling to Putin as he began to open dialogue with Joe Biden about the military architecture of Europe, and feared the increased unity of Europe and NATO as an alliance. As NATO secretary stressed these plans had not changed, Putin dismissed the “right of every nation to chose its path [and] . . . what kind of security arrangements it wants to be part of” by denying the rights of Ukraine as a nation. And as he claimed Ukraine to be a creation of the USSR, as if it were its property, “entirely created by Russia,” he denied any sovereignty as a state, as if a new Cold War might begin by reassembling the Russian diaspora from an earlier, mythic imaginary, not rooted in a map of nation-states, alliances among states, or national security but indulging a deeper ethnic identity.

Perhaps, in this sense, any paradigm of earlier treaties are not the point, from the Cold War to the Warsaw Pact, even if Putin saw the prospect of NATO membership as an aggressive act that ignored his ultimatum. There may be much in Fiona Hill’s fearsome observation that the maps that Putin is reasoning from are not at all from the Cold War–“I also worry about it in all seriousness,” she confessed, that in the pandemic, as we pondered global biorisks, “Putin’s been down in the archives of the Kremlin during Covid looking through old maps and treaties and all the different borders that Russia has had over the centuries,” obsessing with how the borders of Russia and Europe have changed and how Russia might be reconstituted in Europe, and magnifying the consequences of Russians in Ukraine joining NATO. More than believing Putin intends to wipe Ukraine from the map, it was as a state that “it doesn’t belong on his map of the ‘Russian world'” and its borders or the borders of Europe were provisory on all maps: if NATO seems to think that it can dignify the state’s place in a security structure, Hill sees Putin as denying its sovereignty to affirm the notion of “Novorossiya”–a ‘new Russia’–that in 2014 he imagined as a republic from Odessa to Karkhiv, whose own borders interrupted Ukraine from a map; if the hypothetical confederacy was abandoned by the republics of Luhansk and Donetsk, following high level meetings of the United States and Russia, it had gained an independent flag and conceptual momentum bolstered by the decision of Russia and Bielorussia to withdraw from the International Criminal Court as it considered the criminality of actions of annexing Crimea–as it recognized the “armed conflict between Russia and Crimea” as claiming nearly 10,000 lives since men in military uniforms siezed control of the Crimean parliament, appointed a new prime minister who was a shadowy businessman nicknamed “the Goblin,” as the police-men who have been placed puppet leaders in Donetsk and Luhansk, with less practiced in politics than policing.

And as the emergence of Donetsk and Luhansk agains as “break-away” republics conjure a map of Russian transnational sovereignty that trumps Ukraine’s sovereign independence is often cast by Moscow as engaged in a “Civil War,” the proposed partitioned gained little traction or public support–and indeed invited such opposition to be classified as terrorist organizations: the mythic republic condemned for undermining any sense of self-determination were again recognized as states by Moscow in February, 2022, precipitating the invasion of Ukraine.

Continue reading