“Our jobs are being sucked out of our economy by the deal her husband signed,” bellowed Trump pompously during the final Presidential Debate of 2016. If he didn’t provide much evidence for the departed jobs that he conjured to suggest his opponent had encouraged the decline of the American economy, he conjured fear from the audience with apparent desparation. Despite prominently referencing the bad trade deals made by the United States government from the 1990s, Trump wanted to lay blame at the feet of Hillary Clinton for a treaty that has become quite a symbol of the danger open borders pose to the conservative media as well as to Trump supporters. Trump evoked NAFTA in a terrifyingly effective way, even if the sort of association Trump was trying to make ignored the benefits of NAFTA brought to both states–but he linked the signing of the treaty to an “open borders” policy as if it were pegged to a narrative of national economic decline. Calling NAFTA “the worst trade deal ever signed” was no mean feat of exaggeration, but conjured a geographic imaginary of fear more effectively than might be realized–given its quite unfirm grounding in fact–only less than a month before the Presidential election.

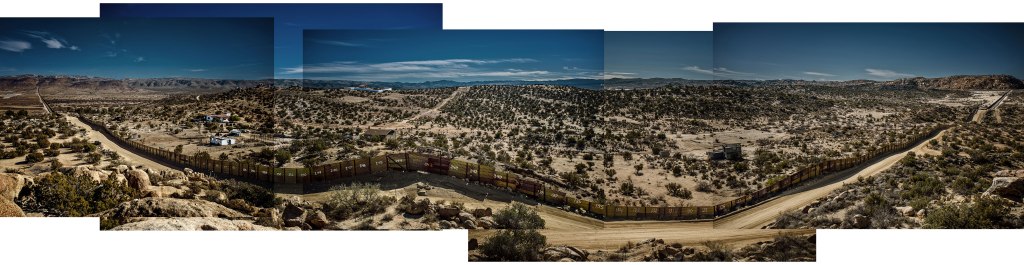

Trump’s rhetoric rehabilitated the call a fence along the Mexico-United States border proposed by Pat Buchanan of the Reform Party. The Donald, in Trumpian fashion, amplified the fantasy of an expansive 2,000 mile fence, into a “beautiful wall,” towering forty to fifty feet height, rather than the six-eight foot tall pyramids of rolled barbed wire long ago favored by Buchanan and conservative Sir John Templeton. Trump imagined the structure designed to “control our borders,” at over ten billion dollars, as a promise to the electorate of which NAFTA was something of an inversion. For the spectacle of wall-building transcended questions of policy, transforming a slogan and a promise to take action on the image of departing jobs into a geographical imaginary, able to do triple duty by responding to departing jobs, rising crime, and being left behind by the currents of global trade.

Karl Marx long ago prophesied consumer goods would move seamlessly across borders in the mid-nineteenth century, the fears of jobs moving across the border and Mexicans entering the country played well to the electorate, even possibly including Latinos, over a third of whom supported the candidate in the 2016 Presidential race, against all predictions.

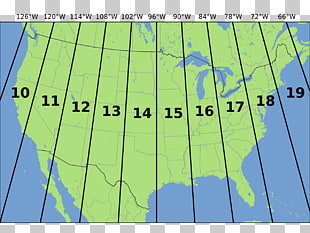

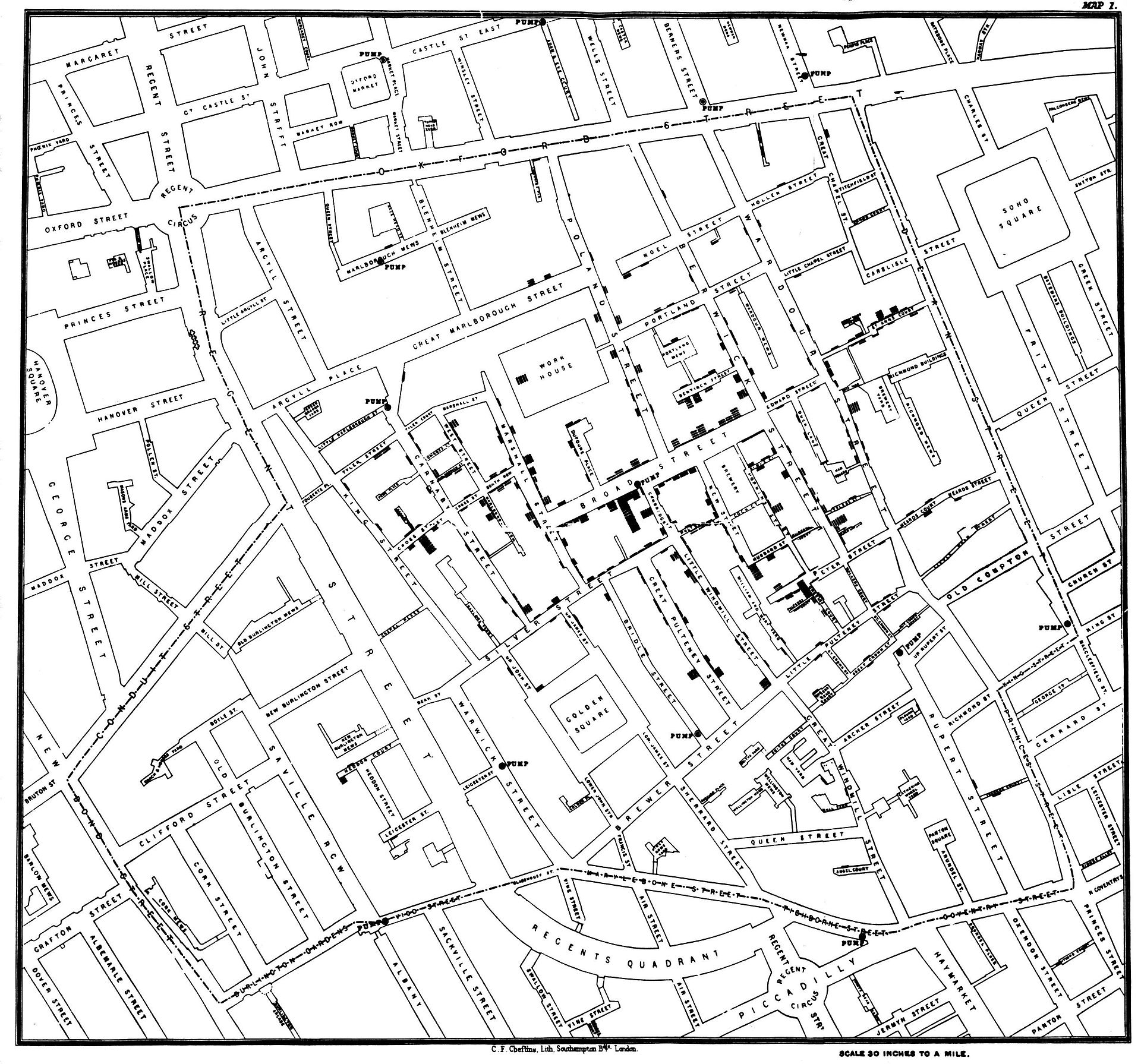

Trump’s ominous evocation of NAFTA was a figure of speech similar to his promise to build the border wall, signifying a staunching of impending economic deflation. For by blaming NAFTA for breaching the boundaries of the nation, exposing it to the rages of globalism in ways Trump promised to exorcise, NAFTA decidedly resonated with his voting base: after all, the map in this header shows imagined corridors of trade that move from the lower forty-eight states to the light turquoise land of Mexico. But the spatial imaginary of NAFTA that he sought to communicate to television audiences during the final Presidential debate of 2016 was of an undue burden on our economy, destined to prevent true economic growth, and a terrible deal inflicted on the United States from which he presented himself as able to liberate the nation. Opposition to NAFTA provided a talisman of Trump’s commitment America First commitment, and his unwavering defense of the danger of leaving national borders open. If the idea that border security led the notion of a “giant wall across our borders” to be something of a fetish for far-right groups as WeNeedaFence.com, which tied its necessity to terrorist threats, the image of NAFTA is something like the negative of such an expansion of border patrol, meant to evoke feared gaps in our national borders.

For the fear of NAFTA seems to have haunted the election in ways that Trump sought to perpetuate. Karl Marx so famously argued that capital rendered national frontiers artifacts of the past, swept away by the flow of trade move across national borders rendered antiquated artifacts , as industrial products are consumed across the globe across borders: yet the fears of NAFTA seems to haunt the current Presidential election with a vigor Marx could never have imagined. For if the circulation of goods may have rendered border lines obsolete, trade protectionism and advocacy of punitive tariffs have helped to resurrect the specter of NAFTA that has continued to haunt the current Presidential election, and has become a mantra that has infected Trump rallies–to the point where, dislodged of any actual truth, it has come to signify among supporters a point that cannot be disputed. Yet as the place of the treaty in Trump’s campaign rhetoric went virtually unchallenged by Clinton’s campaign, and its place in the spatial geography of Trump voters only grew.

To nourish our economy, runs this line of thought, we must reinstitute border lines to prevent “our” jobs leaching, factories relocating, and trade imbalances growing–yet treaties threaten the local economy in what Trump has painted as if it were only a zero-sum game, predicting that the same harm would be the result of the TPP. Marx argued that the “instability of life” of the bourgeoisie meant that “the need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe . . . [and expanding markets] must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.” As if deeply uncomfortable with that image, Trump argued repealing the treaty would keep commodities and jobs in the United States.

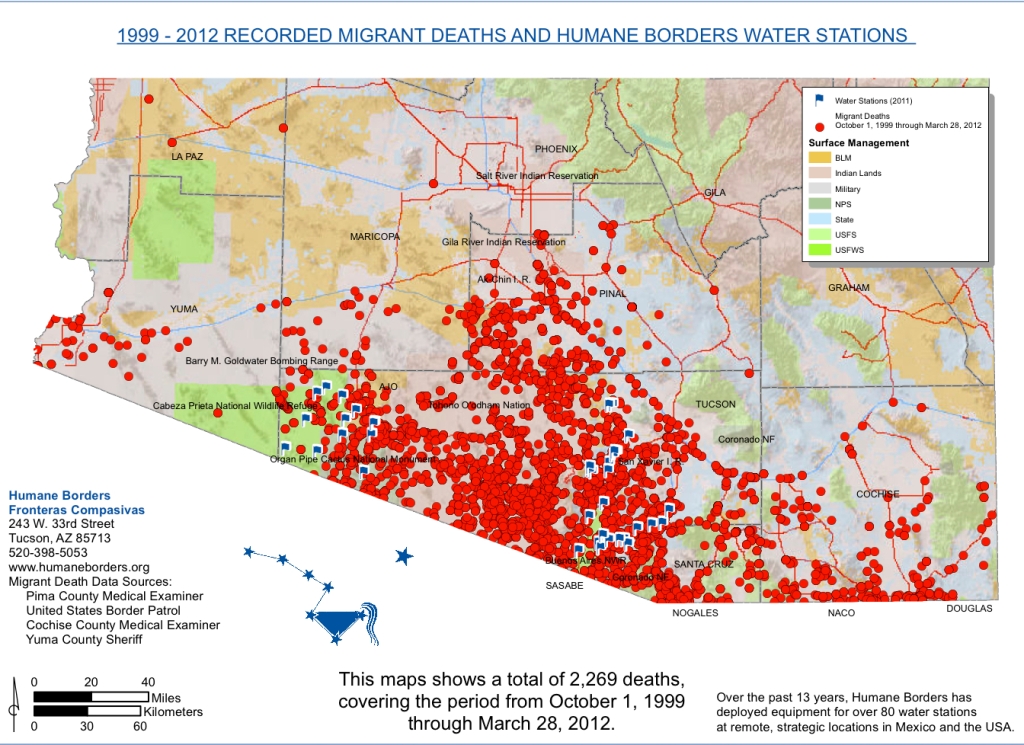

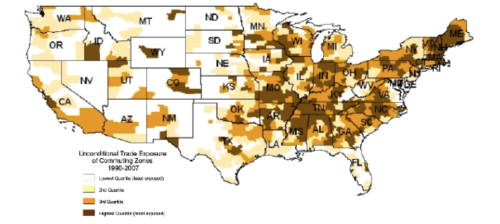

Trump pointed evoked NAFTA for the benefit of his audience, in ways that recalled the construction of a border boundary wall–a wall that already exists for Mexican migrants–as a talisman of his protection of this frontier, by describing NAFTA as a treaty that pushed capital and jobs south of the border, or as if by a vacuum sucked them south of the border. Indeed, Trump may have performed a crucial pivot to gain appeal across many midwestern states by presenting NAFTA as “the worst thing that ever happened,” he takes “the worst trade deal signed anywhere” as if it were a synecdoche for the globalization that has actually seemed to suck jobs out of the United States. Trump has represented the trade treaty as a way to explain the economic shocks of the new dominance of China–and Chinese imports–in the manufacturing industries, according to the recent study by David Dorn of MIT and Gordon Hanson of UCSD, which mapped regional vulnerability of job markets in manufactures to the growth of Chinese imports to the United States from 1990 to 2007–changes that occurred long before Obama’s Presidency, but are still deeply felt and cast a shadow over the nation from Wisconsin and Iowa to Texas and New Mexico.

The specter of economic deflation is again haunting our Presidential debates, thanks to Trump, who re-introduced it into the 2016 election as a way to redraw the constituency he might best assemble beyond the Republican party–even if this means pivoting from Republican dogma on Free Trade.

Despite Trump’s very limited sense of national geography, the image of NAFTA created a blueprint for something like a national policy. The liposuction-like prospect of jobs being sucked out of the country was coined by Ross Perot back in 1992, when he contributed a memorable metaphorical onomatopoeia to the political lexicon in a Presidential debate with Bill Clinton and George Bush, leaving the legacy of a much-viewed meme Trump has resurrected and made his own. Without mentioning the legacy of the claim from the late Reform Party, Trump has used it as a convenient shorthand for impending economic ruin, and a rudimentary spatial imaginary that sounded something like an executive function.

When Trump evoked fears of another unwanted breaching of borders, he adopted Perot’s inimitable evocation of a “giant sucking sound” to conjure factories and jobs shifting en masse south of the border when he ran for president against Bill Clinton and George Bush. For Perot, the sound of vacuuming presented the cross-border migration of jobs to Mexico as inevitable–if in ways that evoked the scenario of a low-budget horror film as much as macroeconomic theory–and the image of loosing economic vitality across the border was long recycled in Trump’s 2016 Presidential campaign. But Trump’s suggestion that the similar inevitability of a breaching of founds of an economic frontiers as a form of national betrayal lies, eliminating national tariffs–one of Trump’s own most favored economic punitive policies of retaliation–seemed like an instance of Clintons caving on leverage in trade imbalances, but also a betrayal of workers, adopting the charge voiced by the AFL-CIO to assume a populist mantle. (When Pat Buchanan took the Reform Party torch, he also argued that such surrender of border tariffs was a surrender of Congressional authority on trade.)

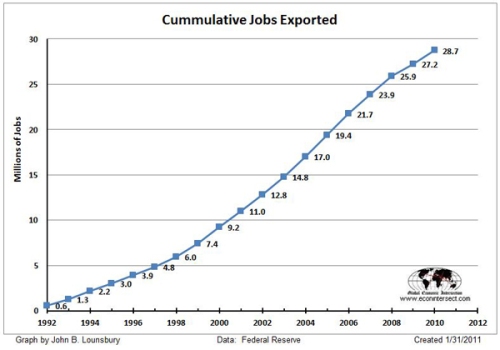

Trump’s accusation of intentionally exposing the American economy to job-deflation resurrected a lost or largely forgotten charge of national betrayal that he wants to lay at the feet of the Clinton family. The fears of losing jobs are proven to resonate, but has this occurred? NAFTA has helped expand a third of our trade exports. The numbers of jobs exported to plants in Mexico since 1992 does seem cumulatively significant to many. Indeed, the increase in jobs moving south of the border seems as if it might provide new evidence Ross Perot was right about the inevitability that that “giant sucking sound” of jobs going south, drawn by cheap labor markets in Mexico, altering the American economy forever–

Yet NAFTA has also led to a growth in corporate profits, with many of the jobs moving to Mexico being for American-owned factories. And the departure of manufacturing jobs is difficult to lay at NAFTA’s door: in comparison to the enormous trade deficits with China and the European Union, rising trade deficits with Mexico since NAFTA are miniscule–and most “trade deficits” with Mexico include goods produced by American firms relocated to Mexico–roughly 3,000 factories have drawn jobs just barely across the border, but outside the American workforce, that have grown the American GDP. NAFTA’s passage created significant growth of GDP, as growth in exports to Mexico rose 218%, helping manufacturing–improving GDP all around for all three countries, if not producing the “level playing field” Bill Clinton had once earnestly guaranteed.

NAFTA has produced, it can actually be argued, an expansion of American manufacturing and trade in ways that have helped not only US manufactures, but allowed an economic decentralization in Mexico that led to a tripling of trade between US and Mexico, and the creation of a North American economic behemoth that expanded possibilities of economic competition south of the border and changed the political dynamic of that country in important ways.

And yet, the metaphorical power of NAFTA has created a very deep fear of national compromise, as many see NAFTA as embodying a fundamental erosion of national protections and identity, locating an abandonment of American jobs and a compromise of American independence in the NAFTA flag–often imaged as a threatening compromise not only as of American economic independence, but of national sovereignty for the alt-right, who saw the treaty as concealing a far-flung plan from multiple governments to destroy American liberties in an integrated North American Union, about which Ron Paul had already warned an increasingly credulous electorate back in 2006.

The same slippery borders that whose dissolution and departure Marx had prophecied as a natureal result of capitalist markets became cast as a loss of national integrity, evidenced symbolically in fears of the abondonment of the stars and stripes.

The metaphorical power of NAFTA grew in ways less easily measured in charts than in the geographical imaginaries that fed and nourished fears of economic decline, in ways no data visualization can adequately reveal. The fears haunt the minds of Trump’s constituents and haunt his oratory, linked to right-wing conspiracy theories that long evoked NAFTA as a question of national betrayal far, far beyond issues of trade–and ignoring the five million new jobs NAFTA has created in America or that jobs the treaty with Mexico has created increased revenues by billions of dollars in all of the fifty states.

NaftaMexico/Segretaria de Economia/@MxUSTrade (September, 2016)

Trump has rather relentlessly portrayed “jobs are being sucked out of our [national] economy” as a violation of an almost embodied integrity in order to evoke fears of a loss of sovereign power, and the belief of a national catastrophe that NAFTA has perpetrated on the United States economy, echoing Trump’s assertion that American industries “packed up and left en masse” since NAFTA was approved. The longstanding fear of weakening America, launched with increasing eagerness by opposition parties but reaching a crescendo in the Age of Obama, has shifted from wrong-headedness to deliberate perpetration in ways that suggest that the map is being destabilized, as it has migrated from the AFL-CIO to an issue of national integrity to become a pillar of the Reform Party platform.

Shortly before the NAFTA treaty negotiated by then-President George Bush went into effect, Reform Party candidate Ross Perot conjured the unwanted effects that would be the result of the as-yet unsigned treaty as one of “jobs being sucked out of the United States“ back in 1992, inviting viewers of the 1992 Presidential Debates to imagine the effects on their pocket books of the trade treaty in strikingly concrete terms as a “giant sucking sound going south” whereby jobs funneled south of the border as a mass migration–a cartoonish sound. The auditory effects were no doubt intended to be commensurate with the massive migration of as much as 5.9 million American jobs–as factory owners were compelled by lower wages. While his appearance on television reduced his popularity, Perot launched an early memes of the early age of digital memory–officially transcribed as “job-sucking sound“–in a haunting spatial imaginary driven by fears of unwanted inexorable economic deflation, and Trump couldn’t let it go.

If Perot’s figure of speech went viral, as many were left scratching their heads at an expression somewhat ill-suited to describe job displacement or to concretely render economic fears, the ugly onomatopoeic simile conjured a departure of jobs in effective ways. The sound-bite was meant to distinguish Perot from either candidate from the two major parties against which he ran–Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush. Although the expression mostly struck audiences as funny because of Perot’s largely dry delivery of the line, it lingered in political discourse with a long afterlife, and was repeated by Pat Buchanan during his subsequent run for President, has reappeared as a rhetorical figure of speech in discourse on free trade in the European Union, and was used often to express the departure of jobs from wealthier nations before being adopted by Donald Trump as a rallying cry of economic protectionism.

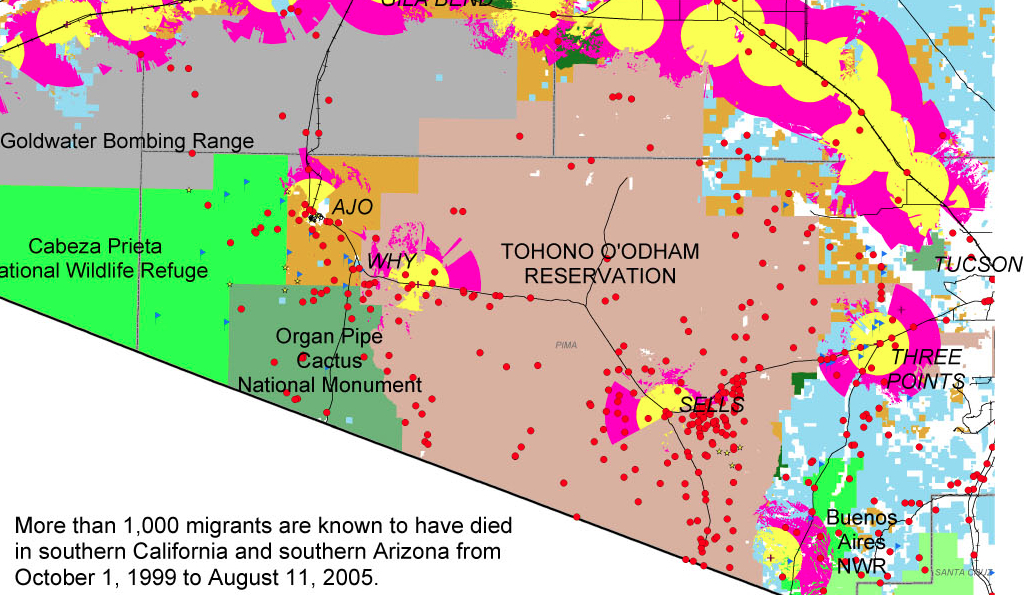

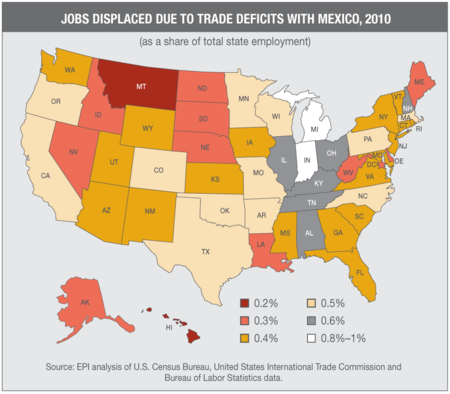

The sense of suction mapped economic fears of geographic displacement in many ways, but the fear was embodied in new ways as it was used by Trump to evoke a national betrayal in ways that were inflected by paranoia of the far right. Indeed, the departure of jobs has not occurred as they shifted south of the border, despite the broad economic displacement in manufactures as a result of globalization. The migration of jobs was not mapped by Trump by the maquiladora industry that thrives on the border-region, but as a massive movement of industry. NAFTA stood for a growing fear of jobs being reassigned to Mexican workers, especially in the auto industry–with Mexico slated to be building a quarter of North American vehicles by 2020, according to the Detroit Free Press–

World Socialist Website (2015)

World Socialist Website (2015)

Mexico’s Auto Plants/Detroit Free Press

Mexico’s Auto Plants/Detroit Free Press

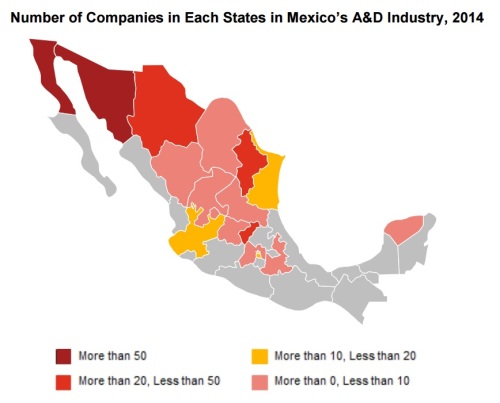

–and the aerospace and defense industries located in Mexico located close to the border:

This is particularly impressive over a longue durée: from but four automobile assembly plants located in Mexico in 1980, the blossoming post-NAFTA of an “auto alley” of light vehicle production, aided by low production costs that compensate for the costs of export, have encouraged the expansion of assembly plants in Mexico, even if the sites of parts suppliers are clearly centered in North America–and indeed, the spatial distribution of parts production is clearly centered around Detroit, also a center for assemblers, although some assembly plants of electronics parts that are most labor intensive were pulled south of the border to maquiladora plants just inside Mexico’s northern frontier.

Thomas Klier and Jim Rubenstein

Thomas Klier and Jim Rubenstein

Assembly of car radios in Matamadoros, just south of the Mexican border/World Socialist Website

Assembly of car radios in Matamadoros, just south of the Mexican border/World Socialist Website

Trump mapped his adoption of a vaguely onomatopoeic description of job displacement onto a narrative of national decline with a decidedly new twist, in the sense that it promised a return to a never quite existent past and a basis to work against globalization. For Trump co-opted the image of suction to bemoan the impending deflation of our national economy, and suggest his hopes for returning to a status quo ante that is not likely within reach. For Trump seems to have sought to remind constituents of his promises to protect “our” borders and “our” jobs he used shorthand for globalization, claiming to protect our interests within a transformational process transcending national frontiers.

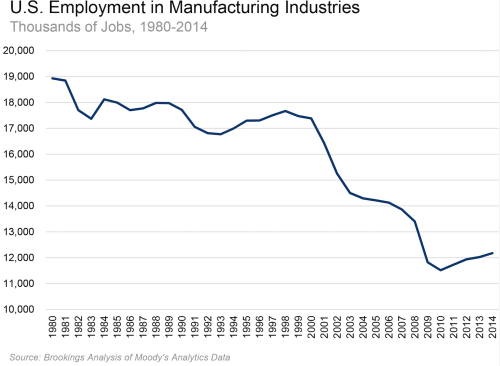

The trade deficit with Mexico has indeed grown: it has quintupled to $107 billion from 1992 to 2004. But US exports elsewhere also declined at the same time by two percent. The decline of manufacturing jobs in America in broad terms during the first decade of the new millennium don’t suggest a clearly determining link to the signing of NAFTA–if it does suggest a measure of “voter anger” that might be placed at the doorstep of broader trends of offshoring, globalization, and automation since 1980 that have in tandem led the US economy to shed 7 million manufacturing jobs over just twenty-four years, with a rapidity that was more impacted by more far-reaching changes than can be mapped onto NAFTA–however compelling NAFTA appears as a target that might be in our control, and a basis to turn back the tide of globalization within a President’s control.

Candidate Trump evoked NAFTA as a basis for geographical over-generalization, as a somewhat clumsy synecdoche for globalization: by presenting the treaty as a part of a whole, he mapped the state of the economy to embody the notion of a departure, localizing fears of a funneling of jobs at one site as a focus for orienting audiences’ attention to globalization: whereas institutions as the World Bank might be more properly as a synecdoche for global finance, which in turn might be taken to stand in for the world economic system, NAFTA is located in the sense that it stands as a synecdoche for globalization from an American perspective: rather than disembodied, it is a sound of trans-border movement of capital, jobs, and employment, emptying out a closed system of economic goods and benefits, and mapping the downside of globalization for Americans, and manages to label that on actors who are allegedly working against American interests.

This is most probably not consciously done. But Candidate Trump presents NAFTA as a symptom of a government committed to a logic of globalization rather than American interests, raising a specter of national betrayal long cultivated by the Alt Right, and to which he tries as hard as he can to oppose himself and to which he presents an imagined alternative: Trump’s conflation of an economic treaty with globalization, and suggests his ability to work, single-handedly, to achieve a Deal that will resist globalization and undo its wrongs. When Trump invoked the old sucking sound, without acknowledging its role in the Reform Party, he used it to raise fears of a spatial imaginary of jobs going south. Trump wanted to lend currency and concreteness to the image of involuntary deflation to conjure fears by casting Hillary Clinton as a job-slayer, and link the deflationary trade accord to Bill Clinton, who signed the treaty–if he of course did not negotiate it–by treating “[Hillary’s] husband” as red meat for red states.

Although NAFTA was a product of George H.W. Bush’s presidency and in 1992 was no longer really on the table, Bill Clinton had celebrated its arrival after it went into effect on January 1, 1994. But NAFTA stood as bogeyman and surrogate for the greater evil of “globalization,” loosely defined as the system of worldwide integration by which goods, capital, and labor travel frictionlessly across national border-lines, and the consequent ceding of control over the paths of global capital, and a consequent decline in state sovereignty–even if Mexico is not “offshore” of the continent, it seems visually emblematic of a permeability of cross-border traffic that Trump believes it lies within the power of the President to re-negotiate, largely as he sees the office as an expansion of that of the CEO, and understands all treaties as open to more advantageous renegotiation to recoup national interests.

Donald J. Trump for President Ad, “Deals” (October 18, 2016)

Donald J. Trump for President Ad, “Deals” (October 18, 2016)

For NAFTA has become emblematic of the fear of erasing borders haunts much of the spatial imaginary of the alt-Right, and presented as a decline of manufacturing that seems something of an undercurrent to how American needs to be Made Great again, or what it once was–even if the net effect of the treaty has been widely judged negligible, despite the growing trade deficit. (After all, NAFTA remains hard to disentangle from the overall rise in employment in the United States.) Yet “open borders” are so linked to illegal immigrants in his mind, and “amnesty,” as well as to the danger of open borders that failed to keep out all those “bad hombres,” themselves in turn linked to accusing Hillary Clinton of welcoming into our borders the “ISIS-aligned” Syrian refugees.

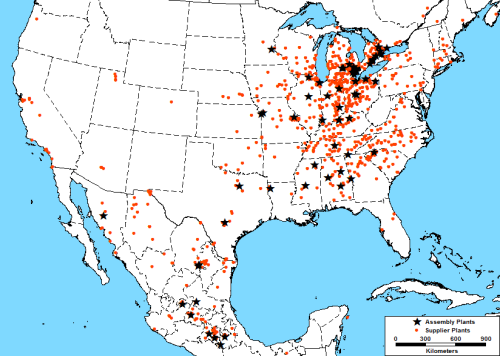

Trump casts all as targets of his wrath and threats to the nation, in a Mad Libs style of debating usually works, even when it is ad-libbed, although he soon strayed into the realm of free association. “Building a wall against Free Trade” has almost become a platform of Trump’s candidacy, as if safety lies in disaggregation–to repurpose an older cartoon poking fun at Canadian national claims–

Patrick Corrigan, Toronto Star (10/28/2009)

Patrick Corrigan, Toronto Star (10/28/2009)

or a more recent one that suggests the security that Trump argues the wall would bring to civil society–and it indeed seems the only concrete proposal that Trump has offered to increase safety, save the scary policies of mass-deportation of migrant workers:

The peculiar after-life of Ross Perot’s unlikely figure of speech had been transformed by a world where borders and border walls seem symbols meant to staunch the flow of jobs in a globalized world seems like a new mercantilist project, lest they be sucked out as Perot, and later Pat Buchanan, sought to make the electorate increasingly fear. But real wages have steadily grown in all three countries, and few jobs have migrated to Mexico, and if the US employment rate started to rise by 2008, the predicted inevitable giant sucking sound was never heard, despite a trade deficit, as imports markedly did as well, jobs grew, and free trade also raised living standards across both borders, despite Trump’s claim of having personally visited sites in recently on his campaign, including Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Florida–badly concealed shout-outs to the residents of swing states, cast as mapping sites from which “jobs have fled” across the border, promising that the author of The Art of the Deal could renegotiate the deal or “terminate” it in favor of making new “great” trade deals–both echoing his earlier promises to auto workers to “break NAFTA” and the image of Trump’s Reality TV successor in the wings on The Apprentice, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Current memory of Perot’s sound bite may be somewhat dim, and the genealogy of Trump’s language in the Reform Party faded, but the echo of the party of which Trump once aspired to be Presidential candidate, before he discovered Reality TV, stuck in some heads, even as Trump packed his sentence with claims to repatriate jobs and money, even if Hillary Clinton didn’t start smiling until Mike Wallace cut him off. Trump almost created a new meme of his own about NAFTA’s proposed termination, but evoked the suction of jobs “out of our economy” as if a feared deflation had already occurred. The fear of suction extracting jobs from the southern border was resurrected in all its onomatopoeic glory to promote a deflation of the economy that fit the themes of deflation to which Trump has returned repeatedly when banging his drum about the dire state of the nation, if with a post-Perot twist: the loss of jobs unveiled a new campaign strategy, aired soon after the third Presidential Debate in the Trump campaign’s “Deals” ad, asserting that the Clintons collectively have been involved in “every bad trade deal over the last twenty plus years” with the promise to “renegotiate every bad Clinton trade deal in order to put American workers first,” as if to rally midwestern states behind his candidacy.

Donald J. Trump for President Ad, “Deals” (October 18, 2016)

Donald J. Trump for President Ad, “Deals” (October 18, 2016)

The Donald’s demonizing of “The Clintons” is rooted in labelling NAFTA a Bad Trade Deal–evidence of the involvement of “The Clintons [as having] Influenced Every Bad Trade Deal Over the Past 20+ Years,” in an economic fear-mongering intended to make folks wary of potential economic losses, while Trump boasts his ability to “Renegotiate NAFTA” as a response to Clinton’s arrogance in “shipping our jobs offshore,” wherever that is, forgetting that “our economy once dominated the world” and borders were more hermetically sealed: the renegotiation of the weakness as the border seems to be at attempt to find new focus for a flailing campaign.

“Deals,” October 18, 2016

“Deals,” October 18, 2016

Although free trade was long considered the best benefit to a nation’s economy, the renewed insularity evident in Trump’s open embrace of America First as his slogan and doctrine, and the spatial imaginary he has promoted. Trump has actively cultivated fears of the danger of movement of manufacturing from our shores and beyond our national borders; images of corporate relocation seem the most pernicious ways government is doing bad to its people, and promoting an economic weakening against national interests: the absence of sealed borders seem to be a way to cast the United States, a huge beneficiary of economic growth brought by globalization, as in fact afflicted by its ill–rather than developing economies who are most likely suffer from the costs of the frictionless circulation of global capital, and a global economy that increasingly immobilizes cheap labor in foreign manufacturing centers.

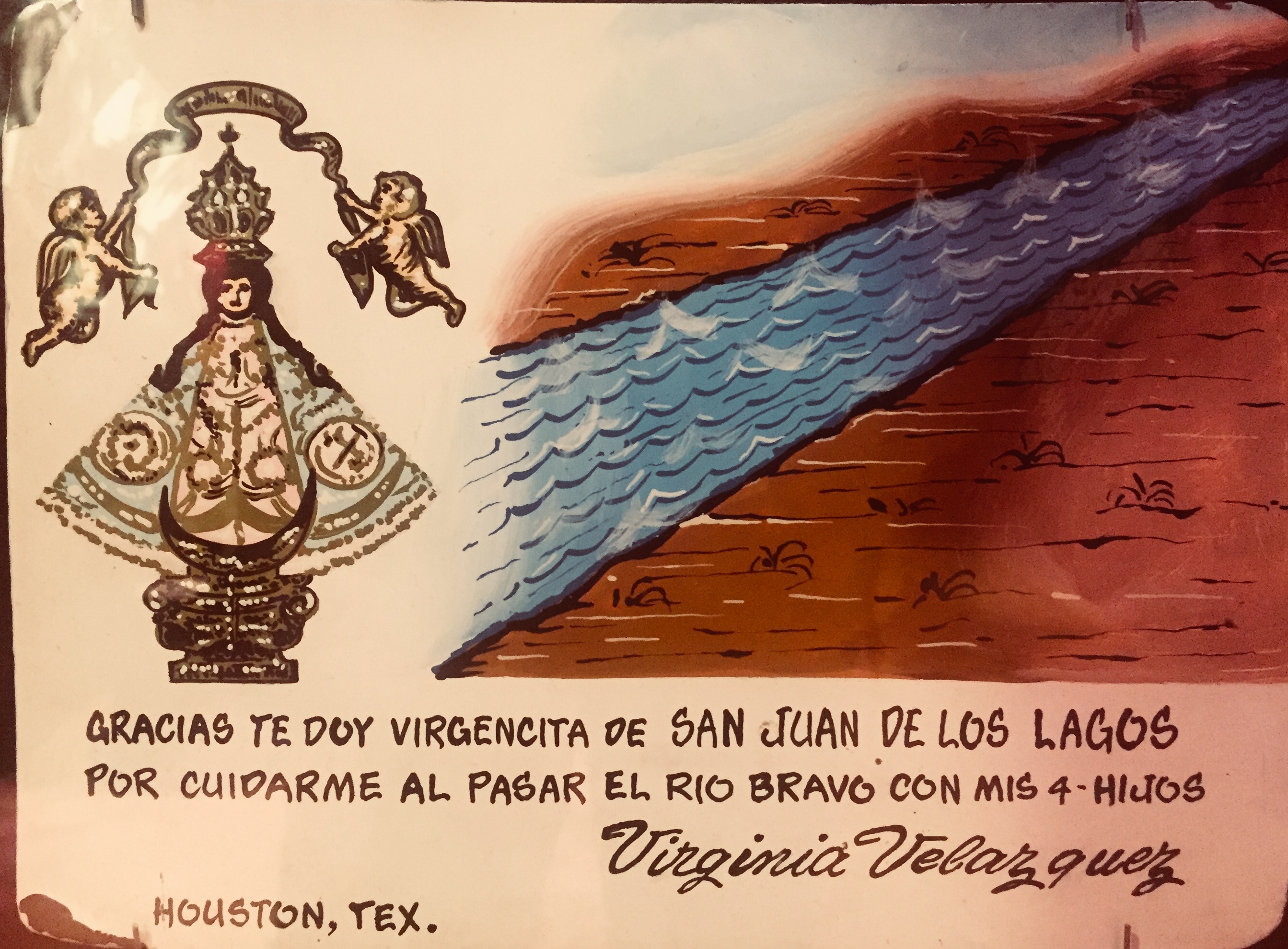

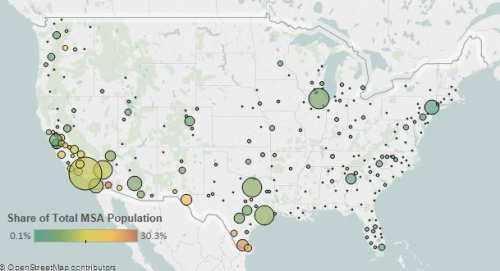

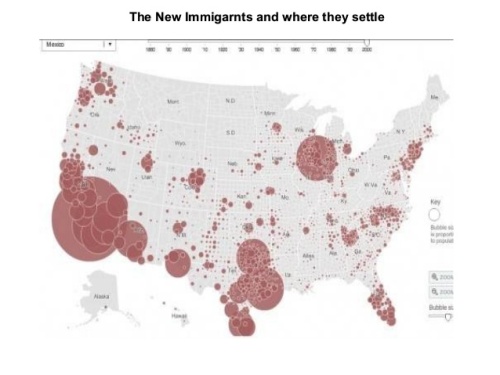

Economic integration have provoked a new economic protectionism, reconstitution the frontier, echoed by the actual “crises” of globalization, as a symbolic front of defense to protect local economies, fed by streamed images of refugees moving across borders in search of work, as the relations of stronger developed countries to developing countries are comparably understood as biologically inflected invasions of outsiders–which “we” no longer can unilaterally prevent or contain. The notion of jobs going south of the border is laughable–the presence of Mexican migrants have a large place in the US urban economy, most concentrated in the nation’s south, but the contribution of Mexican immigrants to the American economy is all but erased, and all too conveniently so.

Moreover, the mutual benefits of NAFTA considerable–and not clearly linked in any way to the symbolic magnification of the border as a site of illegal immigration–an image of cross-border permeability that Trump has perpetuated and rendered as a terrifying object of national concern.

New York Times

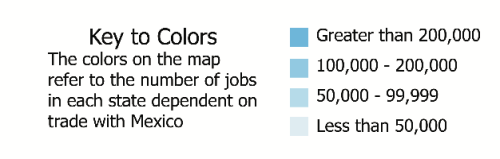

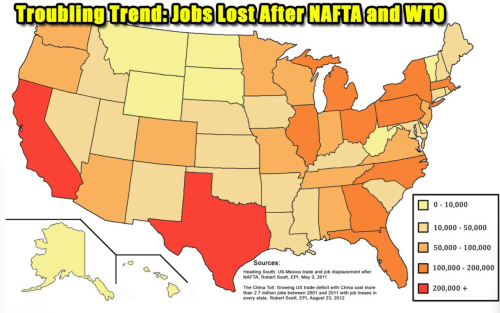

Fears of NAFTA were recently inflated by Democrat Bernie Sanders, if reducing the loss of jobs south of the border to 800,000, and “tens of thousands” in the Midwest, where he was when he spoke, in Michigan, labelling it a disastrous trade agreement for corporate America, boosting the trade deficit, although the analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, although others differ, and the greatest change seems to have undeniably been the normalization of trade with China–and the expansion of auto making in Asia. In comparison, the notion of job losses tied to NAFTA seem exaggerated at best, even if AFL-CIO calls NAFTA’s “job killing” trade accord the basis for displacing some 700.000 jobs–although maps this in a way that is deeply out of skew with its color-choices–

–and a more grim image that Trump meant to evoke was more like the following, grim totaling of jobs that seem difficult to identify as “NAFTA-related” with any precision, but creates a wonderfully gloomy image of the national economy at the same time as it has in fact grown.

Yet is the alleged displacement of jobs related to NAFTA alone, or its consequence?

Yet the loss of jobs aren’t clearly tied to NAFTA, as much as it seems to make tacit sense that they are, in comparison to the expansion of trade deficits with China, and the WTO, which create a data visualization that tells quite a different sort of story, expanding to a broad level of jobs lost in many eastern and midwestern states, if the mapping of such losses date roughly to the start of Obama’s first presidency, or the economy he inherited from George W. Bush.

The question phrased in micro-economic rather than macro-economic terms may, however, play to some states well–and may indeed describe the Trump/Clinton divide. For the factories making cars moving south of the border aren’t Ford, Chevrolet, or General Motors, but Toyota, BMW, Audi and KIA, who weren’t driven there by NAFTA, but by globalization writ large: foreign automobile companies have invested some $13.3 billion in Mexico since 2010, and few American car makers have voiced plans to relocate–Ford’s assembly plant is the only one of the $23.4 billion in passenger cars Americans buy that are built in Mexico exceeds the entire $42.2 billion US-Mexico trade deficit.

In fact, Mexico’s low tariffs with most South American countries and Europe encourages the deal, not the microeconomics of wages, despite Mexico’s car-manufacturing workforce growing to 675,000 and rising employment by car makers in the United States, whose presence in the United Stats largely depends on the ability to shift ‘low-paying jobs’ to Mexico over the last two decades, essentially protecting the 800,000 jobs of car making that remained in the United States, including engineers. There may be some difficulty, however, as well as little comfort, for those out of work to thinking in macroeconomic terms among the very audience that the current Republican party considers the base which it most wants to get out to vote or that it considers its most dependable rallying cry.

The recurrent Republican demand to shore up our borders and boundaries to keep jobs at home is an illusion in a globalized world, where jobs are lost to sites far further overseas. Along the northern border, the renewed fear of border-breaching has created one of the weirdest manifestations of a surveillance state to our northern borders, with the clearing of trees on the US-Canada border, known locally and colloquially as the “Border Slash.”

US-Canada Border Slash/Google Map Data © 2016–Creative Commons

US-Canada Border Slash/Google Map Data © 2016–Creative Commons

As the border barrier that Donald Trump has proposed, but already underway, the “Border Slash” would materialize the boundary through 1349 miles of forested land in the forest along the 5525-mile border between the Canada and the United States, in part running along the 45th Parallel, and plans to extend from Houlton, Maine, to Arctic Village, Alaska–to leave no one unsure of a boundary line that exists only on a map, even if its existence on maps since 1783 has been rarely altered, and was better defined in 1872-4.

Fear of jobs fleeing to Canada are not yet articulated, but creating an area for potential surveillance and apprehension that may have started out of concern for forgetting overgrown monuments on the border needing to be cleared has blossomed into the performance of the boundary line is an odd exercise is isolationism. The Slash, running ten feet into US territory and three meters into Canadian territory, created by the International Boundary Commission, concretized a cartographical divide quite similarly to how Trump has proposed “beautiful” barrier on the US-Mexico border, if markedly less obstructive in its appearance or design.

Carolyn Cuskey/Creative Commons

Carolyn Cuskey/Creative Commons

Perhaps the lack of clear borderlines mirrors the suspicion of the actuality that mapped borders continue to have, as pressures of economic migration have combined with state security apparatuses to refashion the border as a site of national interest. The fear of border-leaching jobs has grown in a world where walls seem designed to keep out job-seekers has led to the expansion of so many multiple projects of national self-definition that the notion of protecting jobs by “terminating” NAFTA seems to make sense. The mounting attacks on free trade, presented as the prime obstruction to economic growth in the US in this most recent Presidential campaign, has been incarnated in a variety of maps that fly in the face of accepted economic consensus that free trade benefits jobs by increasing trade, and cultivate ungrounded if existing fears of the breaching of economic border-lines as an act of national danger.

But the specter raised in cartographical imbalances that have been described as the unexpected if inevitable by-products of trade agreements waged by a political class who took their eye off the interests of the country suggest the monstrosities of free trade has created range from widespread unemployment to a trade deficit of untold proportions that have leached the nation’s virility and emptied its future hopes. Current maps of trade corridors, presented as leaked documents worthy of Wikileaks or the Panama Papers that are to be perpetrated on an unknowing nation, have been widely re-presented as evidence of the hopes to drain the country of jobs, by a measure of deceit almost analogous to the Protocols of Zion, as if jobs ran south with the pull of the gravity exerted by lower wages south of the border, echoing old fears that images of trade corridors were in fact intended as superhighways, begun as a reporter at Fox News described “NAFTA Superhighways” as if similar violations of the national integrity of our economy.

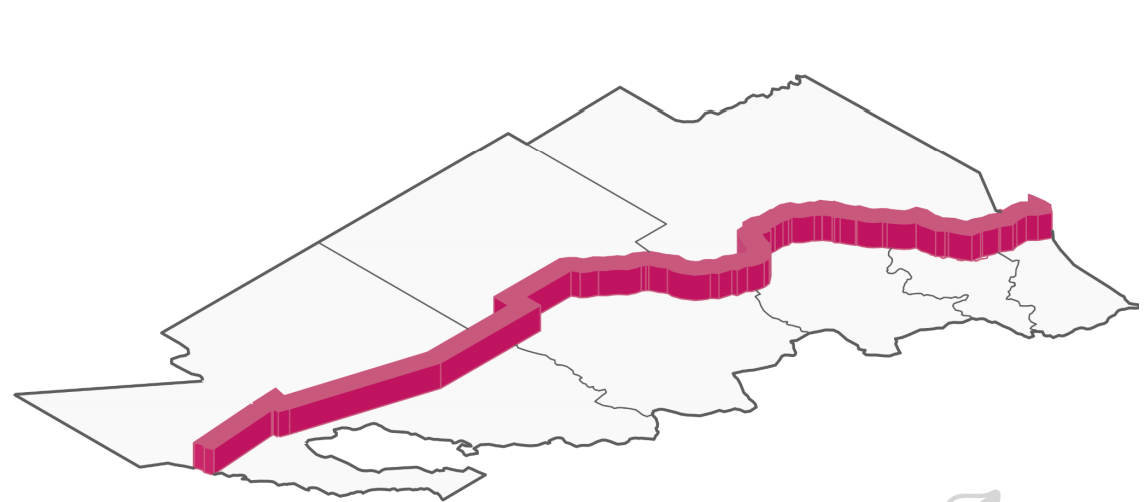

The globalism fears of the introduction to the national highways of a secret “NAFTA Superhighway” has been widely described online as a scam perpetrated by George Bush to dismantle the nation, and create a North American Union, with the maps provided to prove plans for public-private partnerships the would use Texas as the grounds to lease the highways out to toll highways whose funds would be exported from the United States, allowing Chinese goods to be distributed from the “inland port” of Winnipeg, combining three nations into a transport web for a North American Union which would be but a step toward global government, conjuring the geography of a secret highway system as the infrastructure of a network of corridors of transport replete with inland ports and systems of water redistribution, even if they might also as easily recall oil pipelines, and conceal an attempt to convert the United States into a North American Union that will betray the nation’s constitutional ideals:

Although the corridors of trade may provide a basis for the interconnected economies of North America, they suggest a breaching of the interior–and a potential erasure of economic dominance for those who see our future as in manufacturing jobs: for presented in slightly different terms, the corridors suggest an “offshoring” of industry that mirrors a relocation of factories outside of our territorial bounds, and outside our jurisdiction.

June 2006 NASCO website image of I-35 Corridor

June 2006 NASCO website image of I-35 Corridor

The affirmation of effective transport routes runs against the image of national Autarky–the flawed economic ideal of nations who suspected banks and big business–in favor of dangerously open trade flows, which seem to overwhelm the symbolic uniqueness of American exceptionalism, effectively re-dimensioning the nation in a global context and signaling an active eroding of national integrity.

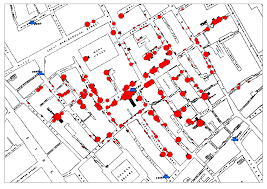

Striking at the heart of the American economy, others connected the “NAFTA land-grab” to the closure of Wal-Marts, as if it offered evidence of the destruction of local jobs in small towns as a result of the growing “NAFTA super-highway” by lowering property values through the closings of War-Marts and K-Marts on which small towns depend, from Wal-Mart Express stores (blue icons) to Wall-Mart stores (red), Supercenter stores (purple), and Neighborhood Market stores (green) suspiciously mapping onto “red states”: the bizarre paranoia that seems to have begun from mapping the closure of a string of 154 Wall-Marts–affecting 10, 000 workers, but giving rise to a bizarre conspiracy theories mapping closed stores onto Red and Blue states or secret government plans that takes the distribution of store closures as revealing foreboding patterns of potential political import from planned conversions to FEMA training grounds or underground military tunnels.

If the distribution of War-Mart closures was tied to hidden NAFTA plans, the expansion of fears quickly found cartographical grounding for a range of deep-set economic unease, that necessitates a new sense of security which economic policies alone can’t provide, and that only a “wall” blocking transnational movement is able to provide reassurance.

The alleged uncovering of the globalist conspiracy of a “Port-to-Plains” corridor was demonized as prefacing a dismantling of the integrity of the nation, and heralding an inter-continental union that would in fact lead to the re-writing of the Constitution, as the map is presented as if it provided a crazed confirmation of American identity under renewed attack.

Dots can be easily connected to the worsening of the local economy and disappearance of jobs as factories head south of the border and the trade deficit starts expands, reducing employment in those very areas where corridors of trade seem to exist–after we had gotten comfortable with billions of trade surpluses, which steadily shrunk from $5 billion in 1960 to just $607 million in 1969. Those days are long over, but the institution of reciprocity brought with it record numbers of job displacement, on the heals of growing trade deficits: the image of “jobs displaced” called for a recipe for their repatriation that has provided a significant source of steam to the Trump train, even if it now seems more likely to crash. Indeed, the image of jobs “displaced” since NAFTA seems to have led to the notion of a motion of jobs to Mexico, even if more have been shifted to India and China than remained in this hemisphere.

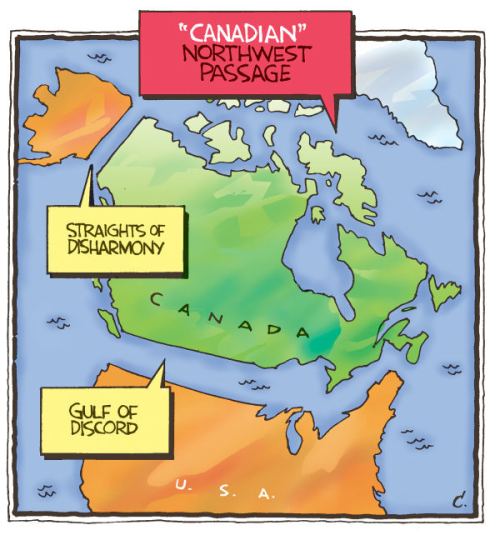

The result, for Melanie Taub, is a state-by-state emptying of the workforce by shifts in employment that confirms that the national government was just not provident when it signed those trade accords, exposing the US to a rush of outsourcing by the very same companies–NABISCO; Ford; Pfizer; even Wal-Mart–that Trump claims led “millions and millions of jobs, thousands and thousands and thousands of plants,” in somewhat inexact economics, to depart the nation that once nurtured them as 680,000 job displacements occurred across the country by 2010. Blaming many of the displaced jobs on trade deficits that “decimated” the American workforce and led “good jobs” to vanish ignores a record expansion of deficits, before NAFTA encouraged a small if significant trade surplus:

Melanie Taub, Investigative Reporting Workshop

Melanie Taub, Investigative Reporting Workshop

Encouraging fears of the outsourcing of American labor, as well as the fearsome byproduct of globalization, threaten to cut at the source of American ingenuity and capital, and are depicted as poised to threaten to eviscerate American wealth and economic resourcefulness: jobs have crossed borders to unprecedented degrees, and trade deficits expand to the incalculable of $400 to $500 billion that seem impossible to sustain. But the attempts to forestall their departure–Chris Christie and Donald J. Trump forego Oreos, for one, until Nabisco brings back its cookie factories to the continental United States. For the jobs that we need to create in the country are not jobs in cookie plants, although any and all jobs are to be valued, but more highly paying jobs for trained workers.

While numbers of guest-workers in America, often not documented, have surely risen steadily in recent years–

NAFTA trade corridors will increase the traffic of goods between both countries in undeniably productive ways, significantly helpful for the infrastructures of both countries.

For Trump, the sound remains one of some sort of unsightly evacuation, or just a painful blood-letting, that the spectacle of a wall–as if one doesn’t already exist–conjures an onomatopoeic simile seen as likely to be staved off, ominously indicating an impending deflation of absolute economic value. By the end of the debate, he somewhat fittingly seemed most spent, the energy sucked out of his face as he was able only to assemble some vague closing remarks of recycled triumphalism after gloating that he would “keep us in suspense” about his intentions to respect the election’s outcome–the response he seemed happiest to deliver all night, remembering how he had started the campaign “very strongly,” before descending into conjuring fears of folks disrespect, inner cities that are a disaster, and words for people with “no education and no jobs,” before pivoting to the specter of four more years of Barak Obama and the concluding and not that rousing the ad feminam taunt of final and utter exasperation, “that’s what you get when you get her.”