In place of topographic local detail, a pastel-hued tiles of psychopharmaceutical pills reveal the extent to which antidepressants have swamped the inhabitants of the United States. The psychopharmaceutical Pharmakon has provided a new figure of reliance of particular resilience: Stanford Kay’s graphic registers a flattening of psychic territory, as much as the dramatic increase in the widespread availability of antidepressants across the country. In this post, I want to drill down into the local topography of dependency, and the reasons for such a broad availability of addictive anti-anxiety medications, in order to create a more detailed–and perhaps just as arresting–image of the circulation of psychopharmaceuticals, and of why we should care.

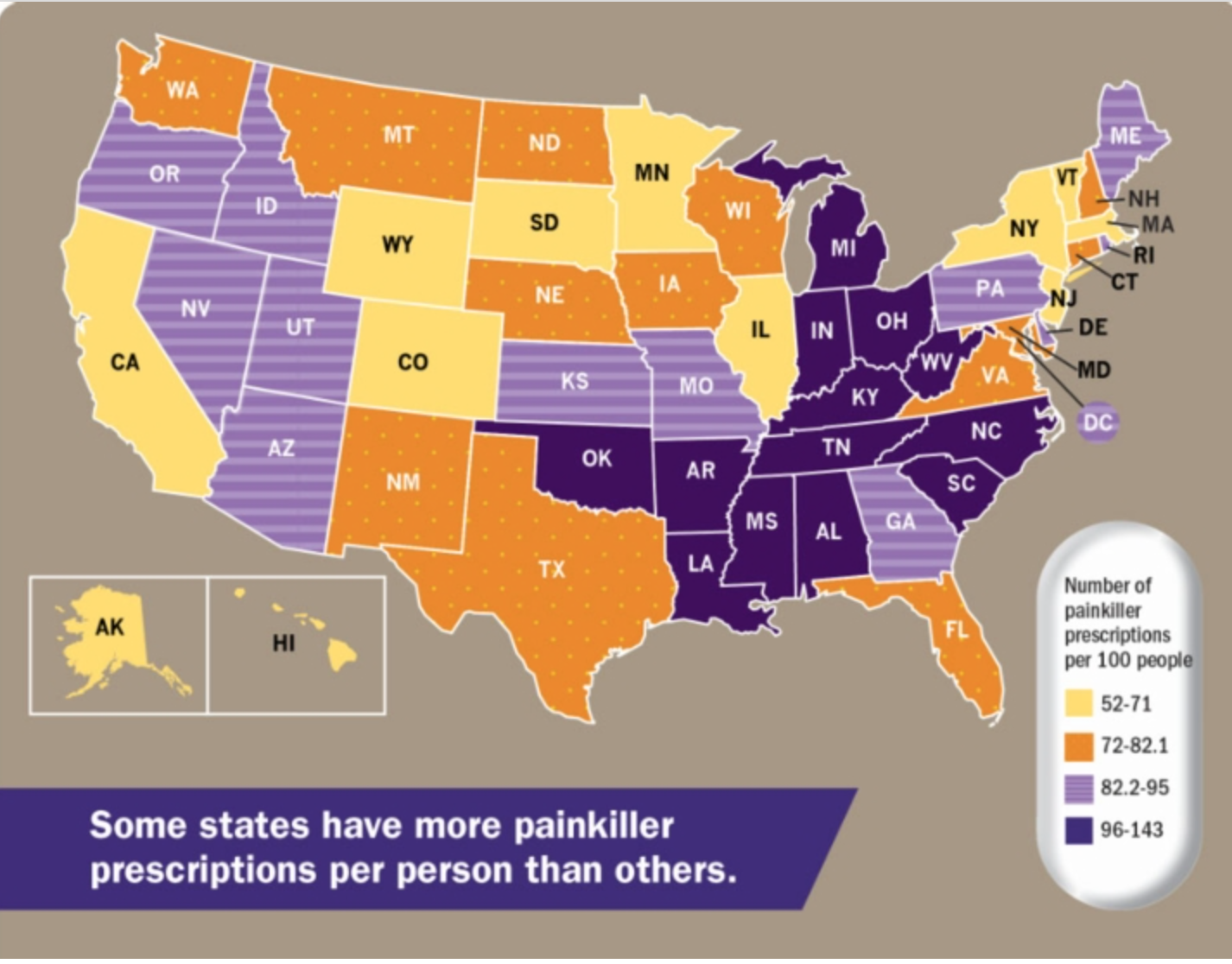

The distribution of opioids across the United States had a startling concentration in specific areas identified with underemployment, focussed as their spread was in states like West Virginia. The decisive concentration of opioid use in rural areas–seemingly surprisingly–was a decisive strategy to gain currency for the bottom-line drugs of coping, as the multiplication of prescription drugs to deal with pain, from oxocodone to hydrocodone, and by 2006 there had been a pronounced rise in the deaths from opioids in rural communities–Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia–that switched the geography of overdoses from urban centers to the bleeding periphery–death rates, reveal newly released government documents, led to an entirely unbalanced share of the 76 billion hydrocodone and oxycodone pills in rural communities.

We can map the disproportionate flooding of these regions that boosted the death rate in these regions by eightfold the national average of 4.6 per thousand, even if those regions were relatively far less inhabited–

–and created a terrifying concentration of deaths by 2006 focussed in rural areas, where companies like SpecGx, a subsidiary of Mallinckrodt, Actavis Pharma, and Par Pharmaceutical, a subsidiary of Endo Pharmaceuticals, created drugs that were so terrifyingly concentrated. By 2006, deaths by overdose were focussed in rural areas, where companies disproportionately concentrated distribution. From 2006-12, the cumulative deaths as a result from Opioids had created a rural epidemic, creating an epidemic like distribution of high rates of death in disadvantaged areas of underemployment, at the same time as the high volume of pills traded on the prescription drug market led to an increase of companies value of 51%, from 8.4 billion in 2006 to 12.6 billion in 2012.

The stealth distribution of opioids with willing knowledge of pharmaceutical corporations was a stealth attack on the nation, from which we may not recover–exploiting the highly addictive and available availability of drugs in an actual belt across the nation from West Virginia to Oklahoma to Utah to Nevada to Northern California, across ninety counties where the death rate from opioids continued to be 4.5 times the national average, often corresponding to areas that were poorly served by doctors, and including some counties where the death rate for opioid overdoses grew to eighteen times the national rate–and opioids were actively shipped to provide over three hundred and sixty pills per person in just a single year.

The “overdose belt” that pharmaceutical corporations created had by 2012 led to an epidemic of 76 billion pills being shipped across the nation’s rural regions–places like Kentucky, South Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia and northern California–where they found large audiences of consumers, who contributed to the consequent rise of uses of heroin and synthetic opioids as fentanyl, as prescription painkillers became less available–hitting areas that had few resources or abilities to contain or act against an unexpected rise of drug overdose deaths that had radically changed the landscape of drug use in America: the flood of addictive drugs had created a new landscape of rural America, increasingly dependent on drugs to assuage difficulties of underemployment that were unable to be otherwise resolved, and all too easy to medicalize in a regime of pain-killers and anti-depressants, without any attention to their increasingly addictive natures: the country became the region of drug addiction, and felt increasingly removed and disconnected to any sense of economic or other benefits, and all too ready to recognize deep difficulties in the status quo, even if they didn’t totally understand or grasp what across the American interior found six companies dominating the distribution of drugs–large starts like McKesson Corp., Walgreens, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen, CVS and Walmart–according to a federal database of all pain pills sold in the United States–who provided legal paths to “pain pills” that fed the opioid epidemic. The concentration of pills/person in a national map from 2006-12 cannot be considered an actual response to therapeutic need–but an orchestrated attack on certain areas of the nation–

–tat ratcfhed up in intensity, as in a controlled experiment conducted on the nation, by 2012–

–and resulted in something like a flash-flood of pain killers that circulated in the bloodstreams of many unsuspecting who died of opioid deaths, which unsurprisingly reflect an eerily identical digtribution.

In rendering a land whose bounds and contours have become increasingly difficult to navigate, awash with psychic stimulants designed to depress the Central Nervous System, Kay uses the prettiness of pills to paint a sad picture of the spread of increased drug dependency. For more than anything else, the massive deregulation of drugs and psychopharmaceuticals from the 1990s has led market forces to shape the availability and dosages of medical regimens to regulate nervous chemistry. Indeed, the shift to market-based models of caring for oneself reflect a triumph of free market forces not only over individual well-being, but the medical pharmakon.

The expansive prescription of psychopharmaceutical drugs maps onto shifting notions of leisure time. Before his death, the Australian sinologist Simon Leys found it an “ironical paradox of our age” that most classes devote little time to leisure who, as most economic elites, have willingly accepted the “slavery of endless working hours,” and the category has been consigned to the “enforced leisure of demoralizing and permanent unemployment.” With the conversion of the professional classes into “senseless” money-making machines, Leys worried, leisure has become the destiny of a lumpenproletariat; if Leys bemoaned the tragic loss of a historically cultivated ideal without reference to America, he described decisively shifted in attitudes to work and time he described parallel the deregulation of markets that go under the expansion of free markets in globalization, and the increasingly forced ties between choice and consumption: we do not choose leisure activities, but consume them; leisure, separated from work, is primarily oriented toward consumption.

Pierre Ryckmans, who wrote under the name Simon Leys, might well have linked globalization to how leisure had become increasingly relegated to the out of work–an unstructured “leisure” time haunted by being unemployed against one’s will, rather than linked to questions of individual choice. The expansion of time without work has led leisure to fill time in new ways. Although Ryckmans made no specific reference to America, but offered an abbreviated genealogy lamented the decline in the reconsideration of ‘leisure’ as removed from either gainful activity or worthy pursuit. To recover a nobler lineage of leisure, Leys rehearsed the long survival of the concept from Chinese literati he studied–“The leisure from learning should be devoted to politics and the leisure from politics should be devoted to learning,” Confucius counseled–through ancient Greeks’ value of scholê as time dedicated to thought, to Nietzsche’s dismay at the “erosion of leisure” he feared an American cultural infection which had communicated the same relentless compulsion to work to Europe.

Much as Nietzsche worried about the infection of a compulsion to work from America that threatened to stigmatize the vita contemplativa, that bedrock refuge of philosophy, by casting it as an altogether shameful fact, Simon Leys sensed the enforced leisure of the underemployed as a deep change, melancholically regarding Don Quixote as the embodiment of leisure past, albeit beset by the combination of too much leisure and few funds that lead him to squander all economic possessions. The taxing and rather toxic task of filling time removed from reading or reflection seems to define the enforced leisure of underemployment as a terminal condition rather than a choice, in ways that signal either a deep failure of the collective imagination in the valuing of work as a productive activity or conflating choice and consumption–for leisure is essentially defined as a choice in habits of consumption, rather than dedicated to as a pursuit or lifestyle.

This emphasis on work as the sole activity of productivity places such undue stress this places on the individual who, out of work, faces the existential quagmire of the value of leisure time. The flattening of the topography of America, pictured in the header of this post, as flooded by a free market of prescribed drugs reveals not only a change in the sense of the individual, but the emphasis on the consumption of prescriptions as a form of life. The recent medicalization of individual psychic and physical experience of pain, itself a correlative of the free-market of pharmaceutical cures, has increased the power of prescription drugs far beyond their earlier clientele. Embodied in the promise of Big Pharma to provide drugs to reduce “moderate” pain through prescribing opioids, the expansion of prescription drugs has more than anything else encourage the four-fold expansion of opioid drug overdoses across the United States in the past two decades.

Suffering from pain was long tied to work, and accidents of work–for which opioids as Oxycontin were first prescribed, as well as being designed for cancer relief. The redefinition of “pain” less as an experience but as a topic and subject for medical attention introduced opioids from Percocet to Oxycontin to roadside retail pharmacies as a condition that is able to be treated in the growth of overdoses of prescribed opioids since 1999, and the tragically decisive distribution of drug poisonings by opioid analgesics in 2006.

CDC

In an odd corollary of the transformation of work, the medicalization of the depression and desperation of the out of work, as a members of a market for the latest innovations of Big Pharma creates a new topography of drug dependence that unsurprisingly partly mirrors that of the out of work. For as unemployment intersects with the pain of depression to be best alleviated by a virtual pharmakon of prescription drugs, one can see an uptick in the dependency on opioids. Such a spread does not only follow a tendency of addiction, but the new availability of potent prescriptions of opioid analgesics from the mid-1990s responded to changes in the labor market across the United States–and if the steady in opioid overdoses is statistically but a subset of drug overdoses, it demands greater examination as a geographic distribution than has been the case.

For even though we have amazingly accurate data on addiction and opioid overdoses for the last twenty years, the actual distribution of both the availability and consumption of prescription drugs reveals deep geographical specificities in relation to concepts of work has not been fully appreciated or examined.

The topography of prescription drug overdoses using painkillers is far more uneven than it is uniform, and the four-fold increase in the distribution of deaths from opioid overdose reveals quite deeply weighted spatial concentrations. Even after the relatively recent celebrated crackdown on pill mills and pain clinics in America, the culture of pain treatment based on the dissemination of opioid drugs to retail pharmacies across the nation has left an aftertaste of the medicalization the condition of continued underemployment. The basis for the marketing of painkillers is deeply tied to the growth of dependence on the illegal trade of analgesic opiates, as desensitization masks as a vaguely medical response. The deepest failure seems to have been the foregoing of pain as an individual project, perhaps, and the topographies of an easy cure that intersected in tragic ways with the decline of the economy after the Great Recession. For the intensive promotion and marketing of opioids as a highly prescribed drug with little need of oversight or monitoring from 1996, the year OxyContin entered the landscape of public health, in a roll-out that led to almost $1.1 billion in sales by 2000, proved so intensely popular that by the year 2004, or from the Recession of 2001 to the Great Recession, despite a wide array of illicit recreational drugs, it became the number one form of drug abuse across the United States, reaching new markets for drug abuse that had rarely existed, and in so doing utterly changed the national landscape of public health.

1. It is tempting to try to map what the range of habits of work and nature of leisure time across urban and rural America. Although the construction of such a relational database of leisure–and ideas of it–are compelling to map, the category of enforced leisure resists clear metrics, and is not clearly present in any single relational database. Yet what Simon Leys described as something akin to a collective devaluation of leisure as a pursuit has its underside in the expansion of pain–and the difficulty to manage the pain that comes from work, or from lack thereof. The drive to reduce “pain” precipitated by anxiety, stress, and depression–and the uneasy relation of pain as a category of attention bridging psychic and bodily pain–has helped promote the popularity of prescription painkillers as a tool to change pain perception and relieve both moderate and severe pain alike.

The demand to do so, and to remedy the spectrum of sense-based pain and anguish, or sensory and affective pain, provided a basis for pharmaceutical companies to promote OxyContin and other opioids to all willing to listen to the possibilities for easing suffering from the mid-1990s. The recent maps of a hidden topography of pain that the geographic distribution of the prescriptions of painkillers and the addiction to such synthesized opioids that has come to plague much of the country–manifested in the deadly effects of addiction to painkillers across much of rural America–maps onto a massive shift not only in ways of spending time but of the expansion of those out-of-work and indeed the pain of those underemployed, whose result may be linked to the terribly shocking visualization prepared by the CDC of the topography of drug-poisoning across much of rural America.

What sort of topography both of pain and of drug abuse does this data visualization reveal?

If the rise of drug poisoning in much of America seems clearly tied to the flooding of much of America with easily procurable and widely prescribed painkillers, promoted across America since the mid-1990s, the morass of the effects of the wide availability of analgesic opiates has created a crisis of public health we are only beginning to confront, as well as an economic crisis of how those afflicted with addiction to painkillers have lost control over how to manage their own time. The plague of analgesic opiates in American that Big Pharma, eager to expand the market for painkillers, has broadly disseminated to patients, downplayed the risks of their addictiveness, and drastically underplayed its risks–or the inevitable possibilities for its abuse–in ways that constituted a true public health tragedy by promoting a regimen for diminishing pain as without risk. The promise of reducing–or absenting oneself from pain–has created the promise of a life free from pain, removed from the subject, unlike the sort of indices that Dr. Ronald Melzack used to allow patients to map pain in the body by the pathways along with pain travelled in the Central Nervous System and “body-self neuromatrix” as measured in the McGill Pain Questionnaire, parsing sense-based (one through ten) to affective (eleven to twenty) pain.

Melzack’s McGill Pain Questionnaire

Unlike the “Gate Control Theory of Pain,” opioids were marketed as a means to pre-empt pain’s sensation that blurred the distinction between sense-based pain afflicted in work and the psychic affective pain that was newly burdened on the out-of-work; the prescription of painkillers designed to be prescribed for chronic pain to alleviate individual suffering blurring. Did this quite different remapping of pain shift coincide with a shift in the landscape of public health costs?

Based on a range of new data–from rates of addiction, prescriptions of painkillers, prescription drug poisoning, overdoses of first-time users of opioids, and methadone treatment centers across the country–a topography of addiction and overdose emerges that seems to have paralleled the increased availability of “pain relief” in retail pharmacies across America. The arrival of cheap and widely prescribed opioid drugs–opioids easily available with largely unmonitored prescriptions–have created deep social and medical costs we have yet fully to ken. The mapping of increased drug-poisoning from overdoses matches the increased circulation and abuse of cheaper opiates in rural areas rarely affected by illicit drugs in previous years, and a rash of first-time users have all been tied to painkillers, whose specific causal relations to one another demand further analysis. For the flooding of the market with low-cost opioid analgesics effectively promoted a self-induced regimen of desensitization that has huge costs on people’s lives and well-being, and of which many are still seeking to gain control.

Rather than pursue a model of pain management, the offering of an option of prescription-strength analgesics as a cure for pain provoked a rash of addiction that suggests a huge tragedy of public health–and reveal a geography of painkillers that cannot purely map suffering or pain. From an apparent high in which some one in twenty adults regularly used prescription painkillers for non-medical reasons, in 2010, the epidemic of painkillers is only beginning to be controlled–although the networks or drug addiction it created have grown entrenched, as they have provided both a gateway drug to tar heroin, and increased the geography of a demand for drugs of mental desensitization that seems closely tied to the spread of the terminal out of work: for the “pain portrait” that such a pharmakon of drugs provide is not a detailed or sharply chiseled portrait of palliative care, but marketing a promise of wiping pain out–rather than addressing suffering.

So much is evident in the new topography of drug abuse and addiction across America. While opiates were synthesized for cancer-induced pain and acute injuries, the dramatically sudden dispensation of new levels of analgesics lacked clear overview, but were aggressively marketed for “non-malignant pain” that bridged psychic and physical pain, and its risks for addiction downplayed. Yet an increasing range of areas of the country are currently struggling with the range of narcotics abuse, seeking to contain the costs of over-prescribed opiates from OxyContin to Vicodin, advocated as non-addictive cures for pain, Narcotics Anonymous has grown across the country that reflect an expanded topography of suffering, rivaling twelve-step self-help programs as Alcoholic Anonymous, as if to testify to a need to remedy addictions.

The growth of the program intersects in interesting ways with states with the greatest prescriptions for painkillers, reflecting not only the skewed demands for prescription painkillers in America, but topographies of addiction. High rates of prescription opioids and self-help groups for narcotics appear particularly pronounced where poverty, unemployment and job losses are particularly acute at the start of the new millennium, which is the subject of this post.

2. Can one use data visualizations of opioid abuse to read the costs of an absence of dedicated leisure time? The growing demand to assuage the psychic pains effected by a lack of work almost reflect a declining ability to order time.

Simon Leys clearly voiced concerns that the “enforced leisure” of the early twenty-first century was the other side of the slavery of work–so unlike the concealment of work by leisured early modern nobility or aristocracy–and a decline of the liberal arts. To be sure, the drastically diminished attention to the pursuit of idleness as is linked to the rise of new networks of opioid addiction that painkillers across America, so unlike the pursuit of recreational drugs among the upper or middle classes in earlier eras. The paradoxical expansion of the use of opioid analgesics designed to reduce suffering have created new networks of addiction as pain-relievers and dependence across rural areas, tied to the past dependence on painkillers, that has necessitated new methadone treatment centers as the number of deaths from opioid abuse has decisively risen in the twenty-first century: despite actual suffering from chronic pain, over-prescription of such easily addictive and abusable drugs have diminished well-being with rapidly expanding social costs that are difficult to foresee, as the daily toll of death from overdoses of prescription painkillers has grown to almost forty-five in recent years. Total fatal overdoses in such addictive prescription opioids tripled from 2000 to 2010, as drugs of such elegantly different neologistic marketing trademarks–Opana, OxyContin, Vicodin or methadone–have come to claim lives in ways never foreseen.

For medical interpretations of the range of mental trauma that afflict the underemployed and out-of-work are deeply tied, in the United States, to how diagnoses that cast depression or anxiety as a form of pain to be alleviated by prescribed pills of pain relief–opioid analgesics that are increasingly recognized as having a darkly addictive side, whose costs are difficult to map in objective fashion. While consumed to induce desensitization or produce periods of euphoria, the rash and resale of prescription painkillers that are inhaled, injected, or smoked in different forms has created a public health epidemic of growing proportions of addiction and drug overdose that has spread to many of the nation’s rural areas–even as law enforcement has persistently focussed policing efforts on poorer urban slums. Even if the DEA found in 2010 that ninety of the top one hundred doctors prescribing oxycodone were located in Florida, the far broader geography of overdose and death is increasingly distributed nationwide, if with a clear clustering in areas of deepest addiction in the oldest manufacturing states. Is this a coincidence?

Although the CDC and other government agencies can measure the increase in prescriptions of powerful pain-killers, the drug-induced deaths caused by such addictive narcotics, and the increase of deaths from first-time use of heroin, the dangers of opioids both to individual health and as gateway drugs create complex networks of dependence whose social costs are difficult to measure or objectively view. The spread of such addictive opiates is fueled by increased tolerance of opiates, but also by the effective social acceptance of such self-induced desensitization by the massive marketing of painkillers as forms of relief, despite their evident costs and consequences, costs bound to increase in future years in ways difficult if not impossible to map in their complete range of consequences–and the cascading spiral of addiction and dependence on painkillers, heroin, and other high-grade opiates, which are simultaneously entering the country in increasingly cheap form. Increasing social and health costs are in part reflected in growing archipelagos of addiction clinics promising rehab across the country, but also in the deep difficulties of addicts to regain control over their lives and their health, given the steep costs of addiction and the inroads of illicit drug markets that the ready availability of OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, and other opioids create–and the spread of methadone clinics across the country.

The rapid retail marketing of painkillers across America from the 1990s first fostered a dangerous of network of addiction across rural America has much to do with the absence of employment. Recourse to painkillers and anti-anxiety medication have brought a course of self-induced desensitization to the doldrums of demoralization for those enforced to spend life in the leisure of unstructured time. For painkillers come to constitute a poisoned remedy for the depressed, injured, and out-of-work, which encouraged or contributed to a recent epidemic of heroin in much of rural America, where painkillers were neither tightly controlled, closely supervised, or adequately overseen. While the Belgian-Australian translator of Confucius bemoaned the metamorphosis of “leisure” to a condition of the out-of-work, growing costs of depression and anxiety reveals a spread of addiction quite unlike the market for recreational drugs, particularly prominent in those areas of the country marked by the disappearance of manufacturing jobs and repeated waves of recession, and the clearer topography created by expansion of those out-of-work in specific areas of the country, among whom the resale of relatively cheap opiates is particularly pernicious, and deeply tied to the increased dependence on what Olga Khazan has called “a cheaper, more accessible high” that sadly reflects the promotion and provision of painkillers to the same demographic in often unsupervised and unmonitored fashion.

It is tempting to look for echoes of the new economics of addiction by their eery intersection with the spread of the out-of-work during the same decade as the Great Recession:

The growing costs of the increasingly pharmacological response to anxiety, depression and physical pain is evident in the current epidemic of the devastatingly widespread abuse of over-prescribed analgesic opiates in specific, because these drugs have been unleashed in unmonitored and uncontrolled ways as a cheap high whose addictive nature encourages both tolerance and abuse. Many abuse painkillers to seek temporary euphoria, but with the often unintended consequences creating a chemical tolerance of opioids and dependence on them that has meant that networks of addiction and illicit sales, once a phenomenon purely urban in scope, have expanded to rural areas, as have unintended overdoses.

While we cannot clearly map such networks with the requisite objectivity of a map, an archeology of the growing consequences of the dissemination of opioids across America in retail stores provides perspectives on the pathways of addiction and networks of dependence in which we are submerged–networks which data visualizations may claim they objectively represent, but which Americans are increasingly immersed in so many ways, and that a single point of view or gaze isn’t able to dominate or comprehend: from the rise of geographic spread of drug-induced death and overdose to the dramatic geographic expansion of first-time heroin users, and the rise of rehab clinics, the social costs of such addiction can barely be measured.

3. Or do painkillers’ wide over-prescription suggest a deadly pharmakon of cures promoted as bridging both psychic and bodily pain, but whose squelching of pain provides an entrance into quagmires far greater than we are able to map?

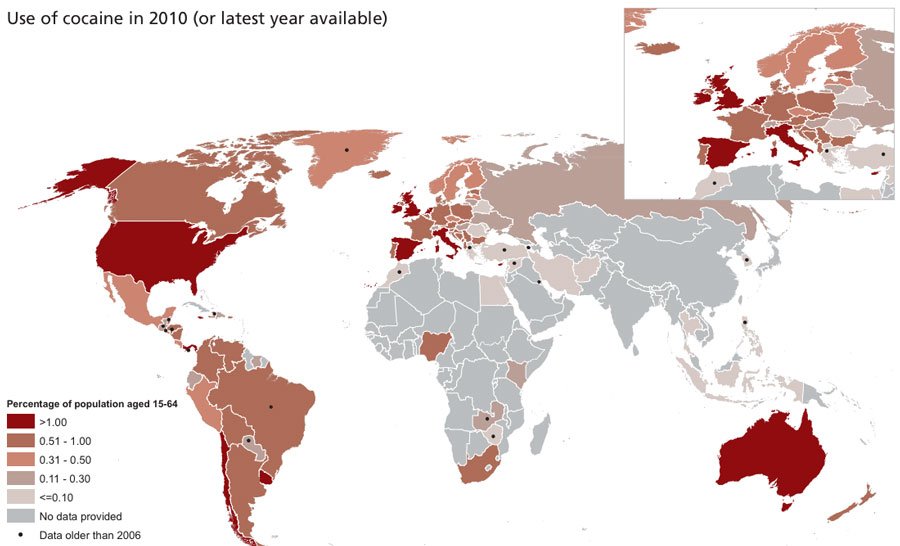

Whereas Plato contrasted philosophy to other occupations as providing a pharmakon of greater riches to its practitioners, the absence of work has been tied to a deadly pharmakon of painkillers in the United States. The often largely unreflective promotion of such poisonous remedies as an alternative to the despair of those with few hopes for stable work, promoting a palliative transportation to an alternate state of mind, particularly disquieting given the deep economic disequilibrium in our society. Despite the false dichotomies drug companies persist in duplicitously drawing between legal painkillers/illicit drugs, non-addictive/addictive drugs, prescription sales/narcotics, Oxycontin/heroin, or Big Pharma/cartels, the ballooning of prescription sales has caused each of these binaries to very quickly collapse. Rather than map onto urban centers of reflection, or onto points of drugs’ arrival in the United States, as, say, the opium dens of leisure that quickly emerged from San Francisco to Victoria to Vancouver after the arrival of Chinese immigrants in the 1880s, in ways that created sudden panics mapped as threats to civil society, the epidemic of opiates in America is less widely mapped, or even seen as the threat to civil society that it increasingly constitutes, perhaps because it constitutes such a mirror of the steep inequalities of economic life and work in many regions of the United States. The strong ties between addictive painkillers and new networks of purchasing and selling heroin indicated in a recent New York Times editorial, that noted the otherwise inexplicable tripling of heroin overdoses over the past three years. Opioid overdoses have claimed over 8,000 in the US in ways hard to process apart from the rise of a market for opioids larger than in either Canada or Mexico.

The chilling statistics of such offers a sort of mirror of the spread of addictive opiates that entered much of the United States as prescription drugs in retail pharmacies, and that must be clearly separated from the traffic in recreational drugs in the pathways of their diffusion and toxic combinations found in the bloodstreams of those who have died from overdoses. The new geography of addiction is, in fact, a particularly scary mirror to hold up to ourselves or our economy. The geographic distribution of the plague of overdoses and addiction to opiates mirrors a demoralizing and incapacitating “enforced leisure” seems bolstered by the inability of adequate resources to respond to an endemic unease and anxiety among the out-of-work. The spread of opiates to rural areas where they are often dispensed or prescribed as a pain relief is far from akin to a leisure activity or pattern of recreation drug use, but suggests a trap of addiction that sneaks up on its users, and arrives as easily from ready-to-fill prescriptions obtained from “pain clinics” or from referrals, and the ubiquity of brand-name drugs that are heavily marketed to all Americans. The striking demographic roots of the rise of prescription opiates across the country demand to be mapping in ways quite distinct from the pathways for the arrival and transmission of drugs into the country when we chart the increasing illegal transport of heroin to rural and non-urban areas along a network of transportation routes that run along the infrastructure of highways–

Strategic Forecasting Inc.

–the routes of heroin transportation mapped above reflect the increased demand for the narcotic opioid across non-urban America.

We have often examined such a map’s primary routes of transportation by the overland transport routes of criminal cartels across the border, and overseas shipping routes from Colombia, Venezuela, or Brazil. But the rise in demand for drugs of deeper degrees of desensitization must be more carefully compared to the rapid rise of opiates across America–as much as the permeability of our borders.

Strategic Forecasting Inc.

The sources for the relatively recent growing demand for narcotic opioids might be better grasped by the new geography of addiction and overdose that the pathways of cartels, urban gangs, or airports associated with urban clearing houses. It is striking that unlike recreational drug use patterns of past years, addiction to medical opiates that were so widely prescribed across the United States have grown in many regions of America not previously marked by drug use–and not as leisure drugs, but as drugs foster by opiates’ deep addictiveness. But if we all continue to focus on cartels as the source of the heroin that enters America, and especially of the stronger strains that of tar heroin particularly plaguing rural areas because of their relative cheapness and availability, we inadequately measure the demand for the greater degrees of desensitization it provides, or to adequately forecast the new patterns for its future growth. The past decade alone has seen a 60% growth in first-time heroin users in America, that cannot be blamed only on its ease of entrance into America. The unassuming Vermont Governor Pete Shumlin to call attention to the 770% rise of heroin use in his state since 2000 as an “epidemic” in the entire State-of-the-State address entirely dedicated to heroin addiction–and speculating on the weekly expenditure of some $2 million in his state alone on heroin, at huge local cost to state residents. It is profoundly striking that unlike recreational drug use patterns of past years, addiction to medical opiates that were so widely prescribed across the United States have grown in many regions of America not previously marked by drug use–and not as leisure drugs, but as drugs foster by opiates’ deeply nature.

It is striking that the addictive dependency on opioid painkillers indeed expanded in the recessions of the early 2000s in unforeseen ways, coinciding with the large number of jobs shed among less-educated workers in the 1990s, before the Recession of 2001, or the job-losses suffered since–estimated from 2.4 to 2.6 million–in the very areas of the country where workers entered waves of unemployment that sent shocks through the country’s core. The pronounced patterns of job loss seem starkly evident as a new topography of the economy in the grim grey maps that offer data visualizations of job loss from the Economic Populist to the Economic Policy Institute—

–where declines in the daily wages seem especially evident in those counties associated with manufacturing–deriving a quarter of employee earnings from manufacturing as of 2000, according to the 2004 ERS County Typology–based overwhelmingly in Southeastern and Midwestern states, which have suffered marked losses of earnings:

The very areas of sudden shedding of jobs during the economic downturn provide a screen on which the subaltern routes of the transportation of heroin and addiction can be projected. The turn to opioid-based drugs might be grasped in part in the shifting economic structures of much of middle America, that seem to respond the new networks that rise of the use of prescribed opioids created–from oxycodones from OxyContin to Percocet, and Percodan, or of hydrocodone, and hyper-analgesics as Vicodin, Lorco and Nortab. Data on the recent spread of opioid prescriptions and sales, and of the addiction to increasingly available opioids clearly coincides with the new geography of the out-of-work across America, and seems closely tied to a widespread trend to the medicalization of alleviating psychic pain. The mapping of such prescriptions and overdoses from their abuse suggest a topography of social costs that demand to be better mapped.

The enforced leisure of long-term underemployment and ensuing anxiety dovetail eerily with the diagnoses of “moderate to severe pain” as suitable for painkillers and the marketing of opioids at most retail pharmacies–drugs of considerable potency, often earlier associated only with acute pain, and the growth of prescription and non-prescription opioid abuse, are marketed as able to remedy an expanding varieties of ‘pain’ at most retail pharmacies. Mostly marketed under familiar brand-names, and widely available at retail pharmacies, such narcotics often distributed through prescriptions increasingly long-term, in ways that further invite abuse, as is reflected in the expansion of painkiller addiction during the last fifteen years in the United States. The availability of opioids suggest not only an easy fix across the United States, but the increasing tolerance of opioids, and pathways of mental addiction they create, suggest a gateway drug has introduced and created a new topography of addiction that poses substantial health costs, even as the prescription of such psychopharmaceuticals was developed as a way to alleviate psychic pain. That the Great Recession facilitated the expanded illegal and legal circulation of powerful painkillers in an unsupervised fashion cannot be denied. The plague of unnecessary prescriptions issued with increasing abandon since the late 1990s, in ways that have created one of the worst and most serious drug epidemic in US history because of their intensely addictive character, whose topography is particularly striking, as are the rash of fatal overdoses opioid addiction has apparently caused in much of middle America.

Simon Leys’ observation may strike one as overly strident in its elitist tone, and is almost openly dismissive of the lumpenproletariat of the long-term unemployed and the mass-marketed “leisure” to which they seem consigned. But it reflects on the debasement of leisure, rather than the class-system that it describes. The grimness of this “enforced leisure” is reflected in the range of psychic pain being out-of-work has provoked among the long-term unemployed, lying far beyond either a Kierkegaardian angst–an inability to enjoy nature and life–or even a Knausgaardian time-stopping despair, perhaps tied to the inherited tendency to alcohol abuse. If Karl Ove Knausgaard is known for tracing a trajectory from possible promise to an intense experience of the ineluctable passing of time in ways that the author’s mind is almost unable to process fully, lengthy meditation is less the scope of such addiction to opioids than the starving for a stronger sort of fix, sadly tied to a desperation of often undetected repercussions and consequences.

The costs of such desperation and the failure to address the psychic pain it creates are increasingly tragically evident in the spread of painkillers across America. The epidemic of addiction across much of the middle of the country–the southeast and midwest–undeniably dovetail with the effects of the Great Recession, during which access to opioids has become something of a terminal activity across areas of America that one would not characterize as likely sites of an epidemic of drug overdoses, where the promises of relieving pain have created black markets that have fueled new markets for illicit drugs able to provide a stronger high. The dangers of painkillers are particularly pronounced not only in their sheer addictiveness, but the rising rise of overdose that they provoke in combination, known or unknown, with the anti-anxiety medications now so widely prescribed that similarly depress the Central Nervous System (CNS) of individuals and which are further depressed to dangerous levels by opioids: of the 6.8 million Americans who filled prescriptions for opioid painkillers in America between 2009 and 2013, some 60% took them in possibly fatal combination with counter-indicated drugs that further depressed the Central Nervous System to fatal levels, inviting a new geography of drug overdose.

The geography of overdosing in America, once confined to urban areas, has so grown during the first decade of the twenty-first century to numb the mind, as many areas of middle America where such fatal overdoses were almost absent have become part of a new national landscape, in which, according to the authors of a CDC study of age-adjusted death rates related from prescription drug poisoning across America, some 90 percent of which were tied to prescription drugs, of which opioids were tied to 21% of drug poisoning deaths in 1999, but 42% by 2009–or over 15,000 individual deaths:

The crippling county-by-county spread of deaths by overdose that was mapped by Lauren M. Rossen, Diba Khan and Margaret Warner for the CDC in a small-area distribution featured some time ago on City Lab showcase a dangerous national trend. For the deeply addictive nature of painkillers is a potentially crippling in public health costs. If this created a shift in policy of the Office of National Drug Council’s policy on anti-overdose drugs, New Mexico–which led in the number of overdose opioid-caused deaths–was quickest to act on revisiting its own policies. Will the nation need to revisit its policies as a whole?

Although it is rarely linked to the economic downturn, it suggests the new pharmacopoeia of the long-term out-of-work or underemployed. Addiction creates an alteration in brain chemistry, and the addictive nature of opioid painkillers themselves rises both on account of the notorious rise in tolerance of painkillers, and the intensity of the addictive demand for opioids. The spread of this poisonous pharmakon has created, moreover, an increasing demand for heroin across America among those in search for a greater fix, forging both networks of sales and pathways of popularity in regions of the country where drug abuse was rarely known in ways only beginning to be mapped, or examined as new networks of pharmaceutical dependence.

Mapping the meanings of the availability and outcomes of opioids across America is particularly important in tracking the costs of the broad dissemination of easily obtained and over-prescribed palliatives at a time when anti-anxiety drugs (designed to reduce depression) are already widely prescribed to the out-of-work, and the adoption of a regimen of pain relief increasingly undertaken, if quite misguidedly, as a viable long-term treatment. The popularity of prescription painkillers during the last two decades arrived in retail pharmacies just before recurrent threats of recession in the early 2000s and in late 2007, coincided with an expanded pharmacopeia that came to reflect our uneasy economic divides with particularly dangerous consequences: for not only are these heavily addictive opioids often characterized as gateway drugs for further forms of depressing the Central Nervous System, but their combination with anti-anxiety meds creates a potent cocktail of psychopharmaceuticals more apt to lead to fatal drug overdoses than most illicit drugs–and open opportunities for fatal drug overdoses across much of rural America. The combination created a startling postcard in 2010 of drug overdoses in America that maps terrifyingly onto the greatest sites of opioid sales, which made deep inroads into the central midwestern and southeastern states that don’t seem only associated with recreational drug use.

Drug Poisonings involving Opioid Analgesics in America, 2006

2010 Age-Adjusted Death Rates for Drug Poisonings

CDC

4. In ways that oddly parallel the shifting topography of the recent recession, the rising use of opioid analgesics, based on promises of pharmaceutical industries to reduce pain, has created an expectation of its alleviation and network of the reliance on opiate analgesics which poses huge economic and social costs, as the Venn diagram indicating the intersection between those taking prescription painkillers as well as antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications has rapidly and perilously grown with ten-fold increase of pain medications since 1990, when Big Pharma marketed a medical culture able to control pain, and to contain “moderate pain” as if it were a form of anxiety–a promise that seems more linked to marketing than diagnostic skill. Indeed, their combination–as the combination of opiates and alcohol–has led to expanded numbers of fatal overdoses.

The rapidly altered landscape of prescribed anti-anxiety medications from 2009 is famous, if not notorious, as shifting the lay of the medical land. And the intersection between opioids and anti-anxiety CNS depressants a train wreck waiting to occur of tremendous health care and social costs, whose costs rarely mapped. Stanford Kay‘s map of the regional patterns of the dominant psychiatric drugs in the country in 2009 indicate the birth of a nation increasingly dependent on the over-prescription of antidepressants, ready to prescribe pills for anxiety disorders, bipolar conditions, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders, panic or post-traumatic stress, with one pill indicating a million prescriptions, from the figurative west coast of Xanax to the east coast of Valium encompasses the zones of Prozac, Zoloft, and the plains of Ativan, it only remains to determine at what point the number of psychiatric prescriptions surpassed the number of people in America.

Most-Prescribed Psychiatric Drugs by Generic and Brand Name in America (2009); Stanford Kay/GOOD

OxyContin–a painkiller claiming more lives in the United States than heroin and cocaine combined by 2012/Getty Images

Despite the diffusion of pain diagnoses and prescriptions, the costs of such opiates are not that widely appreciated. Dr. Nora Volkow of the National Institute of Drug Abuse has begun to draw public attention to these social and psychic costs; she has estimated some 2.1 million in the United States suffering from substance abuse disorders in 2012, and many die from the abuse of prescribed opioid analgesics, in ways that demand to be mapped, remapped, analyzed and unpacked. Although but a fraction of the circa 30 million abusing opioids worldwide are in America, there are huge social costs of such poor medical oversight, as opioid analgesics flood a free market in what seems a market-driven flood.

The expansion of opioid prescriptions form the late 1990s may have helped to create the quadrupling of overdose rates seen in the US since 1999, greater health care costs in rehab and recovery clinics, and costs in crimes, and in lives, and created a new culture of the provision of medical care for pain in readily available form that was widely unmonitored and easily abused–many of which were overly-prescribed and widely diverted for “non-medical” uses as extended-release tablets are ground up, snorted, smoked or injected for recreational use. The public health impact of opioids and heroin are seen as joined by the Office of National Drug Control Policy, and not because of differences in data, even as the number of overdose deaths from opioids has jumped over 20% during 2006-2010, when death from opioid overdoses jumped to 16,661 and overdoses from heroin declined to close to 4,000.

The inappropriate use and abuse of prescription drugs has grown dramatically, despite a recent 2012 citizens’ petition urging stricter labelling of opiates, and their designation for “severe pain,” the costs of opioid addiction and overdose have not been as closely tied–and mapped–to the despair and anxiety of rural underemployment as one might expect. Although Physicians for a Responsible Opioid Prescribing has called attention to the failure of the FDA and US Government to monitor their use, and act to curb the epidemic of OxyContin, the economic origins for the recourse to a poisonous pharmakon of addictive painkillers have been glossed over and not been addressed. Opioid painkillers have become the most prescribed drugs, leading to public editorials to beyond recommendations for their curbing; but the relations between high rates of prescription to the increased economic disparities of job loss are less often unexamined, however striking the distribution of prescription drugs in areas of greatest job-losses.

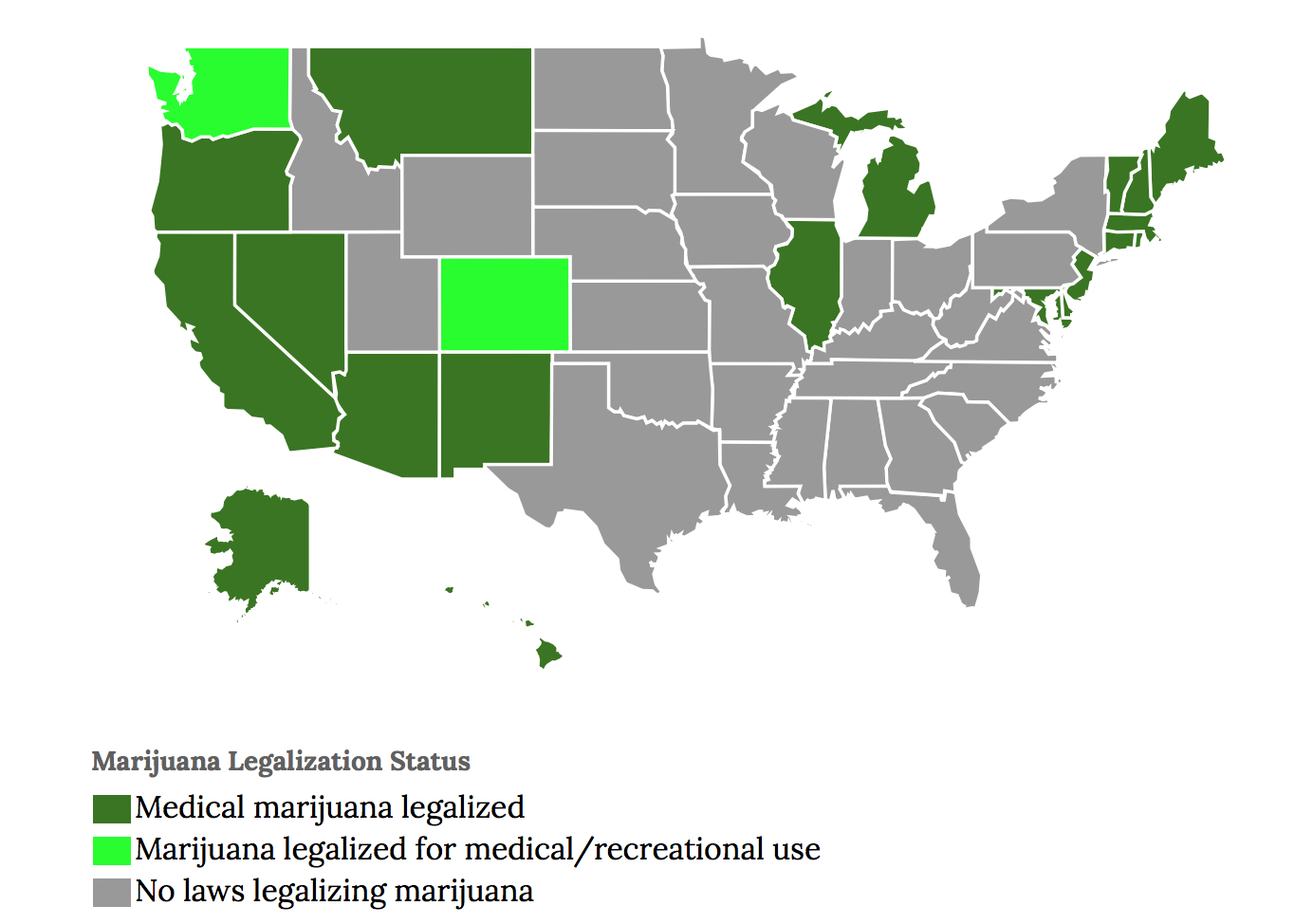

Rates of Painkiller Prescriptions in America, 2012 (USAToday)

The relatively rapid rise of opioid addiction conceals the fact that most rural counties in middle America, so affected by addictive analgesics, still lack treatment centers for their abuse. Their addictive properties, apparent in Oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin, similar in its chemical structure to heroine, create similar depression of the central nervous system particularly perilous to patients. Such addictive analgesics can commonly potentially create quite fatal cocktails paired with widely prescribed anti-anxiety medications that also act to depress the Central Nervous System, inviting unmonitored psychopharmaceutical experiments self-administered by unknowing patients–whose growing tolerance may encourage them to search for potent ways to diminish their pain. (Abuses of Oxy have also been convincingly argued to create a gateway to the consumption of increasingly cheaper heroin often of far greater strength, after it was found in 2012 that abuse of heroin tar among first-time users had grown nation-wide by 60%, as users searched for a similar overwhelming of neural pathways.)

The danger of the distribution of an addiction to opioids mirrors the rise of psychopharmaceuticals for anxiety and anti depression across much of America. Can the anxiety of economic downturn of 2006 have spurred the spread of prescription abuse, or did the consumption of opiates that are branded for regular sale–Vicodin; Percocet; etc.–and created an environment of availability of prescription medicine in the US to alleviate and reveal suffering at such significant costs?

The deep social costs of such desensitization to pain were felt not only by insurance companies–although pain relievers costs insurers companies some $72.5 billion annually in health-care costs[1], but contribute to deep health costs of the growing illegal trade in addictive opioids–whose tolerance, as their effect on the brain’s own natural opioid system grows less responsive to them over time, increases their abuse and possibilities of their overdose.[2] The flooding of markets with such CNS depressants that flood the system with dopamine has fostered their abuse, and revealed a failure to resolve deeper problems–and has created a culture of abuse, encouraged by the increased tolerance of opioids among patients, necessitating higher dosages, often without clear monitoring or supervision to deal with chronic pain–placing them at risk of addiction and transitioning to heroin or other drugs: the death-certificates issued for the overdose of opiate analgesics have been more common than for either heroin or cocaine.

The broad dissemination of painkillers means that members of any demographic might become an addict, and most anyone might die of a drug overdose–and indeed anyone can be subject to disrupting their own neural networks–especially when combined with antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications like Xanax and Ativan that are so widely prescribed and which slow down the Central Nervous System (CNS)–and for which most who held prescriptions for opioids also had a prescription, greatly increasing their risk of death–during 2013, some 60% of those taking opioids legally were hazardously combining them with other medications, and one third taking anti-anxiety medications, creating a climate of neuropsychopharmaceutical experimentation on patients done without their knowledge, putting them at risk of an unintentional deadly overdose. (Just below a third raised similar risks by combining different opioids in an unsupervised manner.)

The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who also wrote under a pseudonym, famously saw the torments of anxiety and depression as a potential stage of transition in life. He described angst not as a medicalized condition–and rather as a possibility for learning to be anxious “in the right way” to gain individual freedom–but his discussion of “anxiety” as an existential condition may have contributed to its adoption as a term of medical diagnosis and identification as a condition medicine could relieve: the expectation for such a cure may have contributed to the currency of anxiety as a state of mind that could be cured. But sales of addictive painkillers at retail pharmacies across America, if by no means confined to being a palliative for anxiety, foreclose much opportunity for individual reflection–and indeed interact with anxiety and depression medications in ways that seem to run experiments with brain chemistry, to create some of the most toxic combinations of greatest risk. The unsupervised spread of opioid prescriptions suggests more of an abandonment to the world. Kierkegaard saw deep danger in the very ease of an ability for “losing one’s self” in the turmoil of the world, even as he prized the potential benefits of such a withdrawal from the world as offering an opportunity to learn true humility.

Rather than offering a cure, all too often the quenching of suffering by painkillers in concert with alcohol or anti-anxiety medications that have also become so widely prescribed suggests far less positive outcomes, and openly courts both accidental overdose and death. Far more bitter than a perception of life’s nauseating air, the growing addiction to painkillers is unlike and lies far beyond the Knaussgardian abandon of confronting and monumentalizing seemingly squalid personal details and emotional impoverishment: if Karl Ove Knaussgard excavated the seeds of deep discomfort approaching alienation to his father’s alcoholism or alcoholic abandon, the addictiveness of opioids presents an invitation to deeper discomfort as well as a possibly fatal gateway drug. The topography of reliance on painkillers paints a picture of a country of sufferers without time for expansive introspection, but paints a picture in which, if Knaussgard described the quotidian detail of a struggle anyone could face, most anyone could die by overdose.

5. We’ve much more concentrated on policing the entry of drugs across national borders–much as the panic that surrounded the historical arrival of opium from China–by mapping the routes of the illegal transport of alien substances as if they run into our lands along smuggling routes and hidden corridors rooted in urban markets and clearing houses. Preoccupied by the sites of entrance of drug traffickers linked to sites lying exclusively outside of our borders, we’ve projected risks outside our borders and less closely scrutinized the mechanics and networks of the illicit dissemination of prescriptions drugs, and the accidental and unmonitored combination of psychotropic substances–and the network of providing opiates not only at pharmacies but pain clinics across America. But the extent of demand for painkillers and opiates is home-grown–as much as they depend on cross-border smuggling, or cartels whose routes permeate borders’ safeguards, the networks that provide a spur to drug consumption are all too often dictated not by leisure drug-use, but by new patterns of job loss.

It is, after all, a bit of a truism that the United States is the largest market for illegal drugs, as one of the most profitable in the world, with heroin and marijuana entering the country since the 1970s across its Southwest border, as heroin spreads from distribution hub in New York City, rerouting heroin from Southeast and Southwest Asia, while Ecstasy (MDMA) entered from European and Israeli drug-trafficking syndicates, border-crossing corridors of trade are only a partial map of the expanding network of market for illicit drugs within our borders. For the rising availability of pharmaceutical opioids in much of middle America has not only grown such border crossing, but fed a growing demand for painkillers in areas where no or few earlier networks for drug sales earlier existed, and created an almost reflexive recourse to pill-popping or tar heroine as overpowering palliatives.

Yet despite the fact that the traffic in drugs does cross borders, smuggled on boats, airlines, cruise ships, and package carriers, a growing demand for opioids fed by the rise of a regimen painkillers, that did much more to attract other opioids into United States markets that never–or rarely–existed before, effectively manufacturing a deep demand for pills and narcotics where none existed before. To map the growing networks of addiction and the dangers of personal and public health that they reveal, we might move beyond the cartels, gangs, or foreign dealers that are often portrayed as purveyors of narcotics to unloosing an unhealthy regimen in much of the country. The acceptance of an addictive regimen of opiates that have become dispensed in drastically different proportions across America, suggest a division of the country only recently examined, but suggests a difficulty of coping with pain of suffering, and something like a readiness of newly emboldened pharmaceutical companies to minister to a broadly diffused geography of suffering, and the desperation that such readiness creates. Although pain-related health issues don’t themselves vary much by region, reliance on and over-prescription of such addictive painkillers creates a geography of social detachment not elected by its victims–but whose increasingly reflexive recourse to prescription drugs creates a growing health risk. Indeed, the networks of providing painkillers to much of rural America–and especially throughout the Deep South–has fueled a shifting topography of addiction that would not be recognizable in earlier decades.

The rash of overdosing from painkillers and illicit drugs that seem provoked by such a now-diffuse diagnosis seem a sign, as Knausgaard may have meant to imply in the title to his book, that anyone can become an addict that has rapidly altered the geography of drug overdoses in the United States–and has the corollary that increasing numbers are dying from drug overdoses or with opiates in the blood. The all-too-nauseating air of such enforced leisure reveals its darkest side in the tragic expanding geography of a newly toxic pharmakon of drugs across the United States, evident in the pronounced pockets of mortality in the new age-adjusted rate of death by drug-poisoning by opioids or heroin across the lower forty-eight, released by the CDC for 2006-10, revealing unexpectedly concentrations of high mortality rates from drug overdoses in states such as Washington, Arizona, Florida, New Mexico, Utah, Oklahoma, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maine–as well as northern California, across demographic groups and rural and urban areas:

Drug Poisoning by Heroin or Opioids in US counties, 2006-2010: #DrugPolicyReform/data from CDC

The broad dissemination of narcotics into discrete pockets in Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and Utah is by no means limited to the urban slums where folks might imagine themselves starving for a midnight fix. Rather than lying in the urban streets where one might be starving for a cheap fix, the dissemination of opiates is fostered by an expanding network from CVS to Walgreens, which facilitate the surprisingly varied topography of their consumption and sale in select areas at ten per 100,000.

6. The growing network providing opiates nourishes an annual market now valued at $60 billion that is rapidly growing each year. For each of the past fifteen years, and pretty much since the last recession of the late 1990s, a startlingly increasing incidence of death from pharmaceutical overdose have mushroomed across the US; at the same time as addictive narcotics are marketed as remedies to depression or psychological isolation–but whose interaction with antidepressants is extremely dangerous, and tantamount to running an uncontrolled experiment on the brain chemistry of many Americans. The all too dramatic diffusion of prescription painkillers in America provoked a parallel increase in recent years in deaths due to overdoses from opioid analgesics, whose numbers had risen 16,000 by 2012, between 1999 and 2010, increased at astronomical rates of 265% among men and 400% among women that demand to be explained. (At their greatest growth, or between 1999 and 2006, perhaps in parallel to a pronounced economic downturn, they expanded expanded by 16% every year.) The landscape of painkillers and pill mills created along highways, in non-urban areas, and even mini-malls–often using regional dealers, more than wholesalers–has not only expanded access to opioids, but a network for encouraging and proselytizing painkillers as a cure-all drug for all with minimal supervision of their addictiveness. The spread of age-adjusted death rates for drug poisoning, including opioids as Oxycontin and heroin, dramatically grew between 1999 to 2009 in ways that reveal a strikingly changing complexion of the country as a whole over only a decade.

The total sales of prescription opioids, if $3 billion was spent on Oxycodone in 2009, grew to $9 billion in 2012. With growing sales of such synthesized drugs including Oxycodone, the highly addictive main active ingredient in Percocet, OxyContin, and Percodan, or hydrocodone in Vicodin, Lorco and Nortab, across America, they have brought increased numbers and waves of overdose deaths. Indeed, the most pronounced rates of growth nation-wide in sales and addiction have brought a huge rise in health-risk, as well in addiction-associated crime in the first decade of the new century, changing the topography of opioid consumption in ways difficult to imagine or comprehend; one can also unpack its consequences one can examine in detail by scrolling across its interactive map:

The starkly shifting geography created by growth in sales of painkillers marketed as legitimate relief suggest the networks of dependence that have grown up around their use. For the wide marketing of such painkillers has concealed their addictive dangers, and the relatively small timeframe in which such different rates of painkillers’ consumption were established–and the patterns of dependence that they have come to create.

Perhaps the acceptance of such enforced leisure is not far removed from the dependence on the desensitization painkillers promise–encouraged by medical advocacy of treating chronic pain by opioid painkiller prescriptions advocated during the mid-1990s. After the return of vets from Iraq and Afghanistan in the new century, the diagnosis was prevalent for veterans, as well as the unemployed, or out-of-work, creating a problematic topography for painkiller prescriptions throughout the United States. Strikingly uneven practices of painkiller prescriptions have been made with an abandon some reckon sufficient to provide every inhabitant of the country with a bottle of pills in the first decade of the new millennia, and by 2012, the contrasting topography of dispensing painkillers created a clearly defined zone in the United States that eerily mirrors what one might call a “rust” belt of a decline of manufacturing, but spread to much of the southern and midwestern states, as well as the western states–and come to outnumber the population.

Some rural areas where painkiller prescriptions are so popular outnumber the state’s population. Indeed, the numbers of prescriptions suggest that addicts may hold several. And these are also often some of the same states without easy access to opioid abuse therapy–which some 53% of the counties in the nation lacked in 2012, despite their overwhelmingly disproportionate affliction by painkiller addiction. Access to needed Opioid Relief Therapies (ORT) are, for example, conspicuously absent for prisoners in many of southern states where they are most sorely needed, from Kentucky and North Carolina to Georgia to Nebraska and to New Jersey:

When Bloomberg News prepared a brittle visualization of a similar time period for sales of opioids, they not inadvertently highlighted the predominantly rural zones of the most intense painkiller sales across the country’s least urban areas. In such regions, easily accessible opioids provided the cheapest pain relief: blue marks the index not of pain, but of the circulation of prescribed painkillers to paying customers–a record not only of “where it hurts,” but of where we are most hurt by the networks of opioid sales across America, where addiction is apt to feed a further demand for harder drugs, particularly as the snorting, injecting, and inhaling of pulverized pills creates a level of tolerance creates a mental demand for greater highs, creating a deeper hurt than the providing of such opioid analgesics may have been intended to respond!

Such data visualizations inescapably map a topographies of deep despair–of desperate searches for painkillers that doctors will not supply, of the resale of prescribed drugs, and of the deception of over-the-counter sales–despite their clear absence of qualitative information.

Multiple stories ran that year, based on similar data, announcing with amazement the emergence of rural West Virginia, Broward County, Tennessee or Missouri, as alternate epicenters of pill-popping, beside Orange County or Staten Island–where Oxycodone sales surged 1200% from 2000-2010–to frustrate law enforcement oversight. Ten of the most opiate-prescribing states were located in the South by 2014. The potential possibilities of empathy are not often evident in data visualizations or maps, whose format often obscures individual cases: the data visualization is difficult to process for its opacity and absence of qualitative details. The distribution of the demand for painkillers as palliatives seems a tragic mirror of the growth of underemployment and unemployment across rural and exurban counties for a random month in 2009–

and broadly echo the decline of manufacturing across the old industrial belt:

Deeply analogous disparities emerged in the disproportionate distribution of prescriptions for painkillers in 2012, a decade after the rise of pill hills, which uncannily reflect drastic losses of jobs exurban areas during the previous five years:

Such data maps of economic divides in America should be compared directly to the mapping of increasingly evident coincidence of opioid sales in 2010 and fatal drug overdoses released by Dr. Ileana Arias, of the CDC:

The juxtaposition of the layers of these datasets again dramatically illuminates a deeply poignant distribution of despair. If it cannot in any way definitively suggest the geographical basis for networks of demand for painkillers across the country, it raises questions about the abuse of painkillers, and the culture of pain relief that grows with increased recourse to retail pharmaceutical stores as outlets for relief. Whereas maps once offered ways to imagine lands on which viewers had never set foot, but the data visualizations of addiction to painkillers offer someone of a truly terrifying mirror in which to contemplate the state of the country. Increased pharmaceutical dependence make the US the largest consumer by far of opiate pain killers in the world, and the painkiller industry particularly conspicuous as a network of health. CDC Director Tom Frieden acknowledges that “opioid overdoses tend to be highest where opioids get the highest use,” lamenting the potential abuse of medications “can be an important tool for doctors to use … but … not the answer every time someone has pain.” The tacit acceptance of opioids across America–concretized in the spread of almost unregulated “pill mills”–has created a virtual free market for narcotics that all but invited abuse.

7. What and where are these new networks of addiction? Whereas cities have been long seen as the hubs for foreign drug cartels, the new networks of prescription drugs from pharmacies or pain centers created a network of drug consumption and a demand for opioids located far outside of urban areas often lying in rural and exurban areas across new networks of consumption. Indeed, the recent migration of outlets for the dissemination of prescription painkillers to such online sales outlets as Pharmacy4Pills, based in the Bahamas, and rogue pharmacies for OxyContin, methadone, and Vicodin have in a sense confirmed the ubiquitous availability cultivated over the past ten years for painkillers that expanded a growing market for deeply addictive substances across the country. Indeed, one such network lies in the increased availability of painkillers at Veteran Affairs hospitals across America.

The curious coincidence reveals a temporary tolerance of opiate-based pain-medication–and encouragement of a network of painkiller provisions–able to be mapped in somewhat terrifying manner by the widespread provision of painkillers by VA hospitals in the US that have wrought increased addiction among returning vets in an all too bitter resolution for their calls of duty in roughly. The expansion of prescriptions of painkillers across roughly the same timeframe follows an almost identical topography, as if a culture of pain medication–or a culture of mistreatment–existed in regions of the country. The disproportionate demand for pain medications may suggest a distinct market for prescription drugs–rather than disproportionate bodily suffering–as was recently mapped as a prescription epidemic by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Center for Investigative Reporting

There should be no surprise that this network of painkiller providers feeding Veterans’ addictions maps so clearly onto a network of addiction–and indeed a network of illicit opiate drugs. The network has created ties among painkillers’ illegal resale and the resale of prescriptions that raise complicated questions about the intersections between a poor economy and painkillers’ prescription. For the consumption of painkillers has so grown across the country in the past fifteen to twenty years that areas which saw low rates of drug overdose facilities in the midwest and southwest transform into regions faced with widespread death by overdose–as prescription painkillers from Vicodin, OxyContin, or methadone are prescribed in the millions, often taken in dangerous doses, frequently illegally sold–to meet diagnoses of PTSD, depression, anxiety, brain injuries, or guilt–with the result of often overloading opiates on PTSD victims with a particular intensity. Such an overloading oddly persists despite the actual possibility of increasing their chances of suicide: VA hospitals over-prescribed painkillers to those suffering from PTSD, despite the possibility that their depression and devastation can lead far more easily to overdoses: indeed, twice as many veterans were found dead from prescription drug overdoses in 2010 as the national average. Such conspicuous variations in the rates of prescription for opiates present a painfully grim picture that fails explanation through any variations in health, health care, or the diagnosis of acute pain.

8. Despite fairly uniform levels of pain in individual states, inadequate assessment of dangers of addiction has created a startlingly differentiated topography in the market for painkillers in relief: the spatial differences in the dispensation of opiates reflects an increased reliance on pain medicine that ranges from prescribed to un-prescribed and illicit drugs that derive from opium that are equally addictive, if more powerful, from heroin to codeine.

The recent legalization of medical marijuana–now expanded to twenty-three states–may provide some relief, as medical marijuana sales of $1.7 billion in 2011 are poised to rise above over $8.9 billion by 2016. Despite clear dangers of long-term use that legalization of medical marijuana may provoke, the turn to medical marijuana is, in many ways, a search for the legalization of potential palliatives–an expansion of the pharmakon of remedies for ongoing pain–to ones that may offer less of a poisoned remedy, but a remedy nonetheless with its own distinct set of risks–if ones we hope more diminished from the opioids so widely available during earlier decades.

Yet are the dark spots in the below map, where painkiller prescriptions are so widely sold to be able to provide the nation’s population, symptomatic of the increased introduction of opioids for a range of symptoms, or the over-prescription of drugs whose true danger was not readily ascertained? Even though many of such pain clinics or fairly satanic “pill mills“–which require no medical records, and exchange cash for pain medication–have been shuttered in severe cases of this national drug abuse epidemic, leading deaths from Oxycodone to plummet, there is strong resistance to creating a database to monitor drug prescriptions–or to insist that the problem does not exist.

The varying density across the nation reveals a stark topography of addiction that reflects the increased circulation not only of illegal drugs, but the availability of prescription opiates across the country. The density of addiction levels maps precisely onto those areas where there is documented use of illicit drugs other than marijuana among those over age twelve–and reveals a strikingly surprising network of addiction across much of the south, southwest and northwest.

Such admittedly schematic and somewhat superficial visualizations force us to ask what sort of pharmakon exists in America. Did the availability of painkillers come to constitute a poisoned remedy for the depressed, injured, and out-of-work, which encouraged or contributed to a recent epidemic of heroin in many rural states, as painkillers were more tightly controlled? Whereas the ancient philosopher Plato contrasted philosophy to other occupations as providing a pharmakon of greater riches to its practitioners, have patterns of unemployment unreflectively promoted poisonous remedies as an alternative to the despair of those with few hopes for stable work, and promoted self-administered substances and self-induced withdrawal to promote a palliative transportation to an alternate state of mind?

Despite the false dichotomies drug companies continue to duplicitously draw between legal painkillers/illicit drugs, non-addictive/addictive drugs, prescription sales/narcotics, Oxycontin/heroin, or Big Pharma/cartels, the ballooning of prescription sales has largely itself caused each of these binaries to collapse. The increased slippage and play between such binaries is indeed hard to deny in the booming of Oxycontin sales. The increased degree of play between these binaries seems most pronounced in areas nicely mapped in the indelibly dark data visualization below of the boom in prescription sales 2000-2010–despite the data visualization’s lack of qualitative detail, and focus on sheer growth of Oxycodone sales per capita alone.

Statistics: DEA; AP analysis–Phil Holm and Michelle Markoff

The visualization mirrors a geography of death by overdose from prescription drugs–a stubbornly grizzly distribution indeed. The data visualization begs not only for correlation with the economics of the out of work, as the increasing money spent on drugs begs for correlation with the contracting availability of jobs. A visualization of such sky-high rates of the prescription of painkillers in the decade from 2000-2010 is an indictment of a medical culture of diagnosis and the provision of drugs, the widespread acceptance of painkillers as a strategy of coping suggests a drastically diminished creativity and resourcefulness in public health options that is almost bound to have high future costs. The overly blind promotion of desensitization to pain through often unsupervised self-administered pharmaceutical dosing undeniably encourages recourse to pain killing drugs.

Is it a coincidence that the increased promotion of opiates for pain reduction dovetailed both with the renewed recession of the early 2000s, and the pain-killers prescriptions provided to veterans returning from war and tours of duty. It bears investigation whether combat fatigue led Americans to consume a whopping 80% of opiate painkillers produced globally by 2012, or what was the role of the economy. But the combination no doubt set the stage for the telling expansion of an economy of pain medicine that dispensed some 110 tons of addictive substances from Oxycontin to harsher drugs as codeine, long a preferred drug across the US. With some 92 Oxicodone-based medications on the market and another 218 containing hydrocodone, the possibilities of addiction are not only endless, but generated by an expanding market for opioids of different brands.

The complex choropleth map of the increasing consumption of painkillers in America is rapidly expanding, even as billions are spent on the fight against drugs in foreign countries, and some fifty billion has been spent on patrolling the nation’s borders, or police patrols’ almost exclusive focus on poorer urban slums–as if addiction were still an urban phenomenon alone, without clear understanding of the new topography of addictive prescription drugs. The health care costs and social consequences of addiction to opioids are bound to increase in future years, with sharply escalating mortality rates by opiate overdose in many parts of the country that are rarely on the map–the growing rates of deaths from overdoses of opioid pain relievers has grown sharply among women since 1999 and 2010 at a five-fold rate of increase, versus by a factor of 3.6 among men, in large part because of unmonitored dosages, but also because of the rapid rise in illicit drug sales.

While for many years, the majority of OxyContin consumption was located in Florida, For the expansion of cheap tar heroin sales in the US that have exploded over the past ten years with a rapidity that has created a public health epidemic of increasing proportions–generated in large part by the pharmaceutical industries. Such advocacy of self-induced desensitization, rather than offering an illuminating perspective on life, has created a cheaper fix than anti-anxiety meds, often themselves offered across the midwest and much of America to ease the depression of unemployed–creating a rush on heroin, it has been argued, as access to Oxycontin was restricted. One saw between 2004-8 a 66% increase in heroin-related treatments in Ohio among suburban caucasians, as demand for black tar heroin first led Ohio to become an entrepôt in its illicit trade. The effects are cast into relief in a map comparing overdose fatalities to traffic deaths from 2008–a year when the majority of such drug-induced deaths in the state of Ohio were in fact due not to heroin but to Oxycontin. Although the DEA found that in 2010, ninety of the top one hundred doctors disseminating Oxycodone were based in Florida, a shifting geography of overdose and death was in fact widely distributed nationwide:

It is instructive to compare the distribution of painkiller sales in the United States, shown here in 2010, by which time admission to treatment clinics had quadrupled nationwide, and review it in comparison to the geography of jobs in America pictured above–both to the loss of jobs after the 2007 Recession in rural and exurban areas, and to a reverse map of those cities where the most jobs were advertised in the last quarter of 2014, if only to suggest in broad strokes that the prescription of painkillers is increasingly tied to questions of our economy. The focus on a loss of jobs in rural or non-urban areas, rather than urban or ex-urban areas, reflects both the greater loss of jobs in those areas, and the unique topography of opiate addiction and use that has emerged across much of the country.