Although we’ve been repeatedly entreated to fear Syrian immigrants as existential threats to our national safety, as if they held sleeper cells of terrorists, we might due well to nurture more sympathy of refugees as people in need. Bills intending to block states from funding refugee resettlement have been introduced or are under consideration in Missouri and South Carolina; programs of federal resettlement of Syrian refugees were challenged in Tennessee, Kansas, Mississippi, and Arizona. The fearsome specter of terrorists seems to surpass the humanitarian needs and obligations of the United States. Compelled by an ultimatum that our national borders needed securing–a false geography of two dimensions, as it were, and of a fixed border that must be maintained–we bracket off the circulation of arms in the broader world. It may be that we’d have more success thwarting terrorism by curtailing arms in circulation that enter terrorist hands, rather than tarring with such broad strokes “terrorist threats.” For the recent evocation of a terrifying specter of terrorist threats that arrive from afar–posing as refugees–hints at the profiling of Muslims suspected as terrorists, for Donald Trump, and deflects attention from the unprecedented scale of the circulation of small arms within our borders–as well as from outside of them.

Indeed, few Americans seem to be conscious of the expanding traffic and sales of firearms worldwide, from the trusted Kalashnikov pictured in the header to the increased guns that have entered circulation–and the problem of encompassing their traffic and its effects pose steep cognitive challenges.

The heightened availability of guns and the expansion of the national gun trade, however, seems more deeply dangerous to our safety than anything arriving from outside of our frontiers. Indeed, in pointing to the dangers of terrorist threats, we may fail to take account for the scope of the growing traffic in guns–and indeed the trafficking and “migration’ of guns world-wide, lest they fail to be more clearly mapped.

It seems easier to fear a refugee, after all, than the firearms whose open circulation ever expands. The purported threat of sleeper cells entering the country’s allegedly increasingly fragile borders is both a casualty of a toxic Presidential race and a crisis in global geography, in which eyes are easily drawn to red flags raised on nations’ borders, while expanding trading zones of firearms or munitions are rarely mapped with any attention to detail. The impossibility to map or foresee threatened firearms attacks are in fact imagined at a remove from the global routes of migration that firearms regularly take in their global sales across boundaries of jurisdiction.

For we repeatedly re-map the scope of the global refugee crisis in hopes to indicate its seemingly unprecedented scope, and increasingly pronounced local reactions to the increased number of Syrian refugees, but fail to map the ever-expanding market for rapid-fire guns–including that most “democratic” of all weapons, the streamlined Kalashnikov. But as we do so, we ignore threats of an expanding free market in firearms which has grown so rapidly to be difficult to map, let alone tally. Although firearms and guns that are the tragic means to perpetrate recent attacks that have cost increased numbers of lives as well as bodily and psychic casualties, the expansion of licit and illicit trading zones of small firearms has occurred in recent years that make discussions of declining violent crime in the nation, the astounding number of over 30,000 deaths from firearms this year–arriving at a rate 130,000 people shot each month–so surpass abilities for easy comprehension to take the eye off of the increased number of firearms in open circulation. And so, when we point to the dangers of refugees, we find a target that displaces attention from maps of shootings in our own neighborhoods,

the lack of decline of firearm-related deaths in the country, the persistently growing number of firearms-related incidents, or the number of mass shootings since Sandy Hook, and, of course, from the circulation of increasing numbers of firearms. And we do not even know how these guns move–although, according to work of Everytown Research, the expansion of unlicensed gun sales over the internet, social media, and site such as armslist.com have been tied to increased gun violence; such sites indeed attract buyers with criminal records–mostly including domestic violence and felon records that would prohibit them from legal gun sales–as a way to circumvent background checks, but provide an increasing means to transport guns in need of legal oversight.

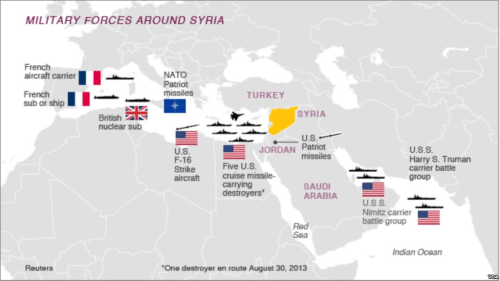

There is, after all, considerable quantifiable satisfaction in indicating numbers and routes of immigrants from the Middle East that can be clearly mapped–as if they contained the sleeper cells of Jihadist threats–but a failure to map the expanding circulation of guns that are the means for such disruptive violence or even to comprehend the scale and stakes of the global gun trade. For it places one at a somewhat myopic remove from understanding the nature of terrorist threats. Perhaps we’re blinded to it, in part, given how much more common gun ownership remains in the US than in other countries.

The growing circulation of firearms and automatic rifles across countries is not a reason for, so much as a consequence of terrorist activity. But it is the chosen and highest impact route for orchestrating attempts at violently and suddenly destabilizing a state and civil society. The Kalashnikov, indeed, looks like a somewhat remote and less grizzly reminder of the spate of gun violence we have increasingly seen in recent years, often through automatic guns outfitted with much more rapid-fire magazines. But the suggestion of foreign agents who might perpetrate gun violence raises more curiosity than obfuscation. And so, when several governors in the United States took to identify points of vulnerability in groups of Islamic immigrants, they openly demonized the foreign provenance of a population of refugees–by metaphors of disease. The readiness with which state governors took it upon themselves to try to ease panic by directing attention to refugees’ entry into the country–even as some questioned whether “states have the authority to decide whether or not we can take refugees”–suggests a dangerous degree of myopia.

Their show of bravado not only undermined human rights accords, but almost directs attention from the growing danger of multiplying markets of guns among those “engaging in the business,” legally or illegally, of selling guns. For the problems of understanding the expanding paths by which ever-increasing numbers of guns circulate–path far less easily tracked, but also challenging collective comprehension. The construction of the United States as a closed universe–all too easily visualized as a hermetically sealed land of local governance–seems a particularly perilous premise in a landscape of the international flows of firearm trading, however helpful it is to indicate the stances each governor took. The constellation of quasi-autonomous political entities seems unrealistically impervious to the undercurrents that lap its shores.

National Public Radio (November 15, 2015)

National Public Radio (November 15, 2015)

By trumpeting such fake fears, the lack of orientation to the scale alone of guns’ sale is obfuscated, since it is so hard to articulate compared to fears of terror attacks by sleeper cells. (Insisting on the need to ensure our borders, they ignore that many Syrian refugees referred for refugee status in the US are children under 12 years in age.) The proposed protective closure of state boundaries distract us from the broad dimensions with which guns have come to circulate at large–and indeed the disorienting nature that the circulation of guns has within most things we can actually measure. If Justin Peters found, based on data six years old, approximately 310 million firearms to exist in the United States–a count broken down into 114 million handguns, 110 million rifles, and 86 million shotguns–but the numbers are not complete. A $489 million domestic market for non-military assault-style rifles Smith & Wesson reported in 2011 has grown, according to the Freedom Group, at a compound annual rate of 3 percent and for assault-style rifles at almost 30%; the NRA reported at least 1,626,525 AR-15-style semi-automatic rifles sold in domestically from 1986 to 2007, whose numbers have since grown far beyond 2.5 million; including foreign-made rifles, the count of assault-style rifles alone surpasses 3.5 million.

Meanwhile the United States continues to shatter records in surging exports of global arms sales, exceeding the 66 billion dollar record high of 2011, far beyond the $31 billion record of 2009, and totaling the $67.3 billion exports of armaments sold in 1994-96 in a single year: another $7 billion worth of excess surplus arms it exported at free or deeply discounted arms rates from 1990-95. And as the US government continues to shatter records in global arms sales, it sets something of a message for the growing traffic in arms worldwide. The collective growth of a global traffic in arms goes scarily unmapped, as we have lost a sense of how many guns in fact circulate world-wide. It conceals a deep ignorance of the actual vectors or pathways of global violence in the traffic of guns and assault weapons whose numbers have not only increased but so dramatically grown in the United States alone that we have no actual idea how many firearms are actually in circulation–if those entering circulation has risen dramatically, as revealed in the number of monthly background checks over ten years–and almost inexorably so since 2008.

NRA/Institute or Legislative Action

NRA/Institute or Legislative Action

1. The solemn insistence by governors to refuse to admit refugees for public safety obscures the almost four-fold growth in the number of guns in circulation in the US from 2000. We not only just don’t know how many hundreds of millions of guns are in circulation, since the self-reported number is rarely willingly disclosed with true accuracy–“especially if [gun-owners] are concerned that there may be future restrictions on gun possession or if they acquired their firearms illegally,” as the Pew Research Center concluded in 2013. We don’t know how many guns circulate in the nation. And this was before 2015 brought more background checks than any year in American history–even if such checks are only required in but fourteen states. To be sure, the conjuring of terrorist threats migrating in concealment diverts attention from how the circulation firearms provide tools to perpetrate such deadly attacks.

As if in concert with accusations of national weakness and the need to secure frontiers, the expansive global currency in light firearms and assault weapons may indeed puncture The increasing ease of purchasing and accumulating assault weapons defines terrorism as nothing else: acts of terror reflect expanding of a “free” legal and illegal market of firearms, which permits the sort of domestic stockpiling of arsenals by individuals, as much as the indoctrination of terrorists over the internet by indoctrinating videos. Amedy Coulibaly famously kept an array of AK-47s and ammunition stacked in a hamper in his home. And the firearms legally purchased firearms as the AR-15’s used in the San Bernardino mass shooting, bought at a local retail chain, Turner’s Outdoorsman, and later modified with larger capacity magazines–raising questions of whether the arms should be sold without clearer background checks, even as other voices remain firm that concealed weapons could have prevented the deadly attacks Tafsheen Malik staged with with AR15s, before fleeing in a black Ford Explorer with more than 1600 bullets in the car. The stockpiling of arms by the Pakistani Malik and her husband Syed Farook, who she joined in the United States from June 2013, after being subject to background checks, was enabled by the wide availability of arms in the United States.

Despite demands to create better surveillance and management of bullet sales, fears of government encroaching on gun ownership led the AFT to openly withdraw the proposals.

It is not any secret that the proportions of the growing global traffic of arms has escalated in particularly dizzying ways. Providing a better mapping of the scale and circulation of the transaction of such assault rifles may not be a measure against their later use. But better mapping their density and volumes of scale seems increasingly important when illegal gun trafficking is increasingly incumbent in a thriving underground and above-ground gun trade. Is defense of permissive attitudes to gun sales really an excuse for not mapping the migration of guns in actual inter-connected webs of human exchange?

The increased fetishization of ‘open carry’ in America seems something like a terrifying public pronouncement of one’s ability to exist in a world without clear purchase on the increasing numbers of guns that have come to be regularly exchanged–and even carried openly in public in times of peace.

Bill Pugliano–Getty Images

Bill Pugliano–Getty Images

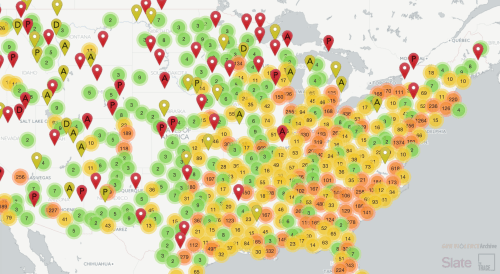

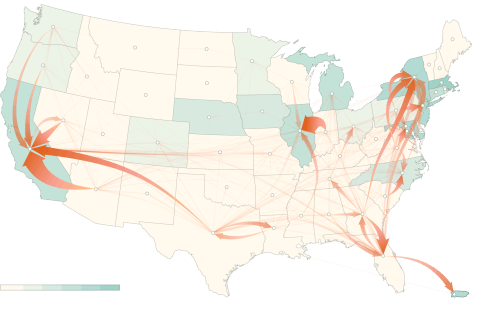

Assault weapons are not only purchased at gun shows or sporting good stores, but are in need of better mapping nationwide. About 50,000 yearly cross state lines on underground networks of interstate traffickers, often subverting one state’s gun laws by arriving on highways, by FedEx, or from states with markedly different gun laws, often under the eyes of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. While admittedly based on the guns that arrived in cities from other states that were confiscated by police, the pathway of underground sales to urban areas are particularly striking, and dangerously remove gun sales from any official monitoring or oversight. Although it often repeated that “guns don’t kill people, people do,” the arrival of guns under the noses of authority suggests not only an evasion of laws, but thriving illegal markets for guns, some foreign.

New York Times, based on data of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

New York Times, based on data of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

If gun trafficking is a major inter-state offense, a significant number of the trafficking cases for guns involve international illegal trafficking of firearms across borders, mostly with obliterated serial numbers, making it difficult to identify exact numbers of guns or ammunition that reach foreign countries with certainty–in postal shipments or by underground routes of gun trafficking.

We can understand the basis for such traffic from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri and Florida through the uneven geography of enforcing background checks at gun shows reluctant to admit that they “engage in” firearm sales.

Governing, from Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence

More clearly mapping the increased pathways of travel taken by firearms seems a far more opportune response to terrorism, as tracing the multiple pathways assault weapons take provides a basis to better to comprehend the growing dangers of assault. And despite President Obama’s decision to not harp on the need to map guns better in his State of the Union address, only a better mapping of the traffic and movement of guns can present a better image of gun sales–and indeed suggests cultivation of an individual bond to guns.

The ease of access to assault rifles in the United States and diminished checks to their purchase or policing have had limited attention until recent months. Despite deep fears exploited in suspicions about the hidden infiltration of the country by terrorist threats, far less attention has focussed on the needed tracking of the illegal transit of firearms across borders: in an age when we are apt to concentrate on social media as a tool of indoctrination of subversive and on mass-migrations as hidden vectors enabling flexible geographical mobility of terror networks, it’s perhaps overly retro to focus on the itineraries of the transport of mundane material things like guns. Tracking the physical movement of small guns, rifles and other firearms, and the transport of assault weapons such as the popular Kalashnikov reveals the deeper social relations encouraged by the greater circulation of firearms–and indeed an increasingly global sense of cathecting to guns. The paths by which guns reach the hands of their users isn’t as interesting, perhaps, as the uses made of them, but demands to be far more closely tracked.

Attention to firearms’ rapidly increasing availability in the United States is relatively recent–partly in light of the limited oversight of hobbyists “engaged” in selling guns–but also is a microcosm of the growth of a global market for firearms. Indeed, increased sales of arms as well as applications for concealed weapons permits suggest an increasingly vicious circle between escalation of sales in response to announcements of gun control policies, leading gun salesmen to crow that “Obama is our best salesperson,” and gun sales to double over his administration; mass shootings have not only accelerated sales, but created new currents of gun transports, as well as growing numbers of first-time applications for concealed handgun permits with mass shootings, as well as a growing geography of places accepting open carrying of handguns in reactions to fears of gun violence, and agitation from pro-gun groups to change laws to allow open carry and conceal carry as a right to self-defense in a country whose residents seem increasingly desperate to seek safety.

Increased number of mass shootings have partly prompted gun sales in ways from which manufacturers such as Smith & Wesson have been able to consciously profit–whose sales channel further funds to the NRA–and the webs of gun sales both in the country and on an international scale demand to be mapped. More detailed mapping of the growing global exchange of military materiel–tracing where guns go–however raise tantalizing questions about networks of global firearm exchanges as the dark side of globalism in what might be called Pynchonian proportions.

The novelist Thomas Pynchon has returned with what seems quite considerable prescience if not obsessiveness to the motifs of the circulation of rockets, rifles, grenades, or small bombs–often encoded with cyphers–as the telling modern talismans of global exchange; mapping the trade in arms, one of the historical items of global trade, reveals eery global networks in the post-Cold War world that demand to be more broadly mapped through the routes that guns are increasingly disseminated across channels of illicit as well as public exchange. More than ever, the hydra headed illicit trafficking of arms–as well as the “legal” arms trade–seems an emblem of globalism.

But the routes of the licit and illicit transportation of guns indicates increasing cultivation of firearms as powerful forms of human-object relations–a relationship which oddly links such terrorism to mass shootings, though the two threats are quite distinct. And the transport of firearms have also so intensified globally to demand to be better mapped, as much as the question of what it means to be “engaged in the business” of selling firearms demands to be better clarified. (In the span of a single recent year, over 644,700 ads for guns from those without licenses to sell were tallied by Everytown Research in the single online marketplace Armslist.com, most not selling only individual firearms.) Visualizing the global context of the local pathways exchange of small firearms provides a way to consider global changes in firearm exchange on a local level that is particularly illuminating–and to identify global markets of small arms exchange for mobile arms of considerable force, including automatic assault rifles such as the Kalashnikov pictured in the header to this post, one of the most popular and most widely produced of firearms.

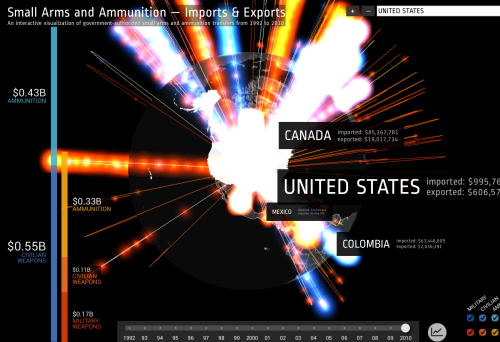

2. Exposing the global markets of small guns was the ostensible subject of Google‘s 2012 day-glo interactive “Chrome Experiment” that maps global arms trafficking–a big data visualization limited per force to legal trade of small arms alone, using public data from the Small Arms Survey. Nonetheless, the interactive 3D maps offer a cool tool to investigate what globalization looks like, in a sort of weather map of the arms trade that occurs above-board and in the open. The “experiment” offers a sort of landscape of small arms markets for ready scanning, letting one to rotate the globe interactively to create the best vantage point on aggregated data from reported imports and exports, or the above board “over-the-counter” gun sales.

The gloriously color-saturated interactive Globe allows viewers to rotate the globe in different manners to chart the global traffic of firearm imports and exports in surprising fashion. The exports and imports are mapped from individual countries, while parallel bars break the official numbers down into ammunition and small firearms, allowing one to parse the massive flows of armaments that proceed from larger mega-states like the USA to the world. The weirdly aestheticized images will make viewers oscillate between wonder, stupefied awe, and depression. It’s a strikingly powerful visualization of major arms providers, like the United States, as it illuminates their traffic, and in scanning the globe that we can turn interactively, we can compare the somehow huge exports of ammunition the US manufacturers send to the world–the huge importation and exportation of firearms in the US compare to the incredible 85 plus million imported in Canada (where guns and ammunition are less often manufactured) or far smaller number imported in Mexico, where few guns are allowed in personal possession, unlike the US.

One can visualize the global dispersion of imports (blue) and exports (red) moving around the globe in animated vectors, coursing with an intensity of white-hot fashion:

Interactive Globe: Small Arms and Ammunition-Imports and Exports

Interactive Globe: Small Arms and Ammunition-Imports and Exports

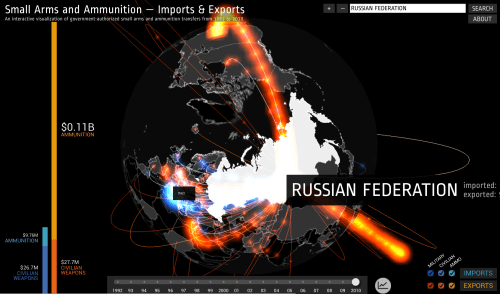

The interactive map is a sort of GL 3D experiment, and foregrounds the rotatability of the globe to seek the best angle by which to visualize each country’s collective import-export business of arms and ammunition. For larger arms exporters like, say, the Russian Federation, the results are spectacular–the RF streams over 140 and a half millions of dollars worth of small exports (mostly to client states) and imports another 36 million worth, here shown coursing the globe in pulsating red and orange neon arcs; the thin blue streams of imports contrast to major rivers of exports to Russian client states. The global format has clear advantages for visualizing major arms providers–although the maps eerily disembody and almost naturalize the arms trade. The graphic rendering of the small arms trade can’t help but seem–even if this is not its primary intent–somehow celebratory about its explosive energy, so that one can forget what the sort of small arms and firearms traded actually are, segregated as they are from any mortal consequences:

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

The impact is similarly stunning, if less grandiosely global, for smaller states in hot spots as Serbia, as it allows one to look at the globalization of arms, struck by the relatively few bright blue lines of arms importation, and the flow of $28 million of legally exported arms from the small country that chart the remapping of its global significance circa 2010 with a similarly sinister white-hot glow, revealing the surprising scale of its huge exportation of arms worldwide:

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

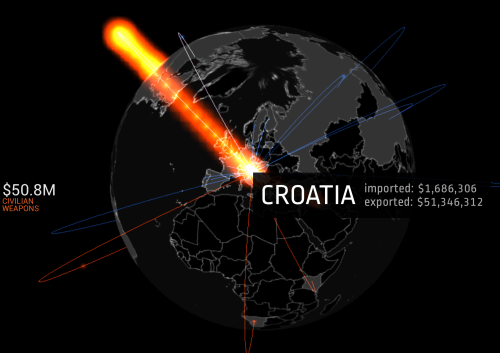

There is a similar odd balance between local and global in the collective arms trade from neighboring Croatia, a major exporter of materiel and transatlantic provider of arms:

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

or examine the glow of flows of exports and imports to and from Hungary-

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

and the local importer of arts, its Balkan neighbor Montenegro, which seems to import a considerable amount of arms indeed–

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

Google Interactive Globe: Small Arms Imports & Exports

3. Such enticingly glittering global networks leave us in awe at the massive amount of arms trafficked, as if what passes under the radar would be insignificant in comparison. But it makes us thirst for better local knowledge. Small is beautiful in mapping local knowledge of the mechanics of the hidden paths guns travel, as well as their licit sales, which prove far more multi-causal and serpentine than the broad brushstrokes afforded by “where the world buys its weapons”–and it reveals the patterns of illicit gun transport, accumulation and sales. But, most disturbingly, they are utterly removed from human agency, as if such geopolitically inflected macroeconomic flows are actually alienated from paths of traffic on planet earth.

Indeed, local pathways are perhaps more illuminating when it comes to arms traffic–especially, of course, of illicit trade in arms not revealed in such global macroeconomic images. For few of the actual arms we want to track circulate stratospherically along the aeronautical routes the Google rendering suggests. Despite the benefits of Google’s glossy macroeconomic global view, what would it mean to make this mapping more local, more closely focussing on local transport of individual arms by itineraries, or to try to track hidden on-the-ground routes of firearms supplies? The big data maps almost make you want to wonder what went on to the individual materiality of arms themselves, which vanish into so many brilliantly coursing data streams.

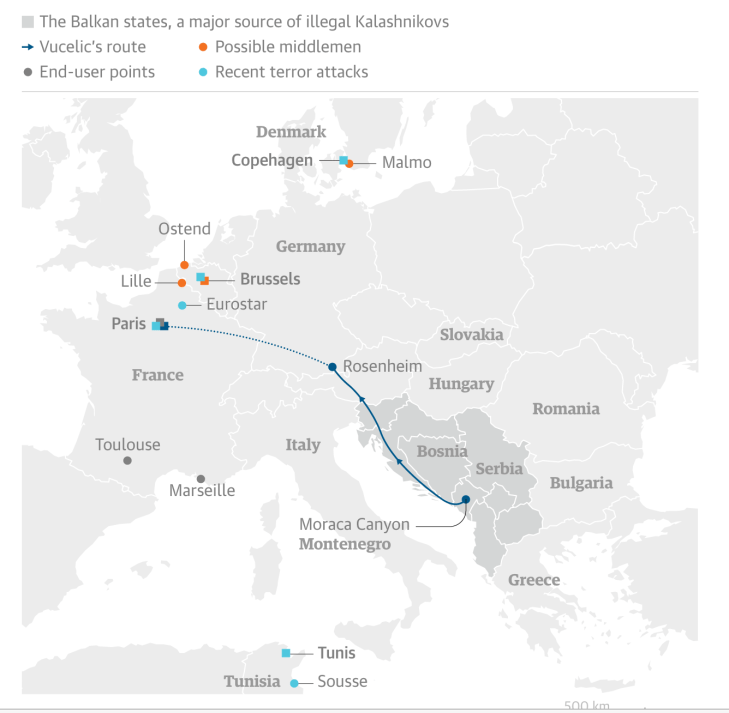

Mapping local routes of arms travels, if less glamorous or flashy, seems increasingly timely, if less interactive or dynamic in form. But together with varied maps of the same regions, they provide another way to visualize networks of violence, civil war, or terror. The basis for the transport of Kalashnikovs lies in large part in regions in the Balkans, as Montenegro, which provide pathways by which they are carried to Schengen lands.

The Guardian

The uncontrolled smuggling of arms in the Balkans, recently a veritable hub for the illicit arms trade, led the United Nations Development Program to give a mandate to the Pynchonian entity of the South Eastern and Eastern European Clearing House for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons, acronymized as SEESAC; uncontrolled weapons trafficking in the region increased its chronic instability and fueled local crime, with a arms exports in the western Balkans amassing $1.6 billion between 2007-13, and little data available on illegal trade arms trade that is increasingly a problem of global proportions. Of course, it parallels the primary route for the burgeoning business of routes to smuggle asylum across the western Balkans, for which some €16 billion was payed to middlemen since 2000–

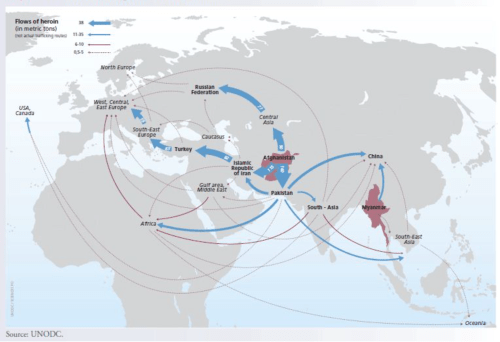

–following routes that almost directly mirror the popular pathway for the also lucrative heroin trade from Afghanistan, onto which it might well be superimposed:

UNODC

UNODC

and global routes of a metric tons of heroin carried on a modern and more mechanized Silk Road moving across Asia to European markets:

UNODC

UNODC

But the trajectories of assault rifles across the Balkans have allowed amateur armories to be assembled by folks like Amedy Coulibaly and Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, who planned and executed attacks at the office of Charlie Hebdo, including multiple AK-47s, Scorpions, handguns and semiautomatic rifles, van loads of arms, often of Soviet production, from the 7.62-mm Tokarev rifle to the AK-47 with which Coulibaly infamously decided to pose beside in the curated message he would stream to the world after he had killed four innocents at a Kosher Deli in Paris. (Coulibaly neatly stacked those AK-47’s and their ammunition in a laundry hamper in his home.)

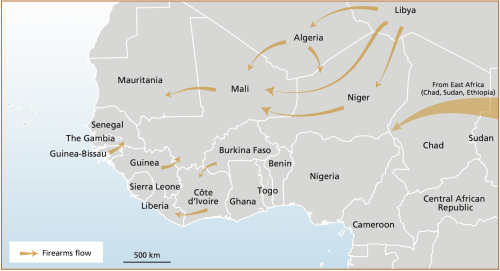

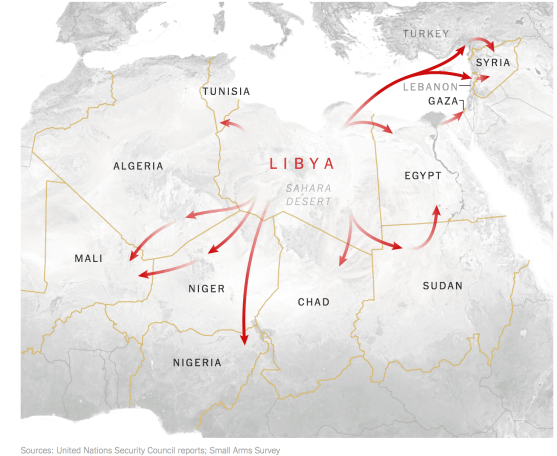

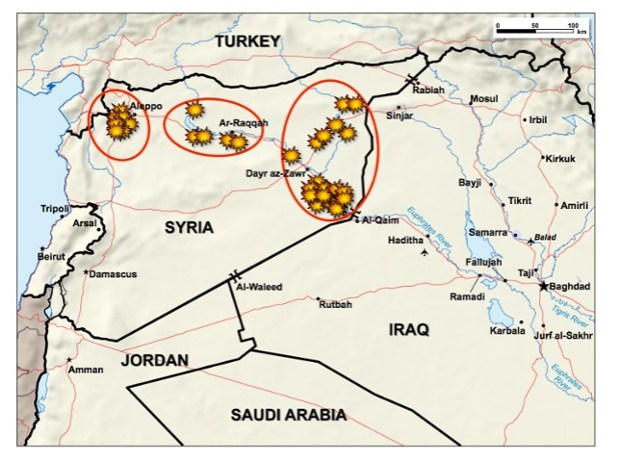

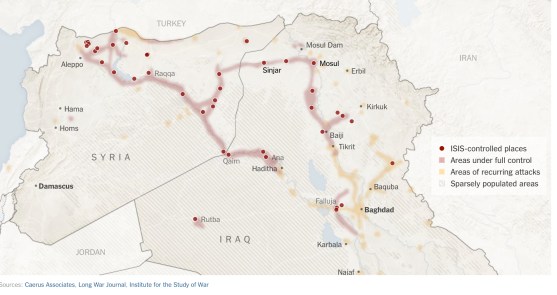

The broad range of arms available to ISIS was dramatically increased through the proliferation of war-torn areas across the world, as the Balkans, as well as the collapse of strong-armed power-hungry states–as Syria or as Libya–who had long stockpiled small arms within their national armories. Indeed, the collapse of Libya prompted a struggle to contain Kalashnikovs, and struggle with the possibilities of instituting anything like a buy-back program in the country, given the clear value of arms in a society that seemed poised to descend into chaos, and growing advantages of owning arms in most all of north Africa. As a garrison storing 20,000 surface-to-air missiles simply collapsed in Libya, as previously guarded hidden arms caches throughout the country that constituted the huge arsenal assembled by Col. Muamar el-Qaddafi entered the black market quickly, and spread from Libya, according to the Small Arms Survey, through much of the Middle East, reaching Syria as well as Mali and Sudan, even as US-sponsored “covert” actions to arm rebels funneled still more arms into the country as it approached the brink of civil war–and many rebels, desperate for cash, sold the arms with which they were supplied.

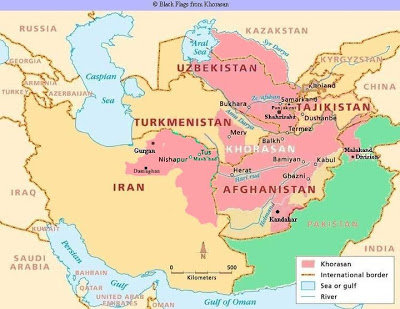

4. Perhaps the pietas of commemorations for the eponymous designer of the assault rifle of which all others are epigones, Lieutenant-General Mikhail Timofeyevich Kalashnikov, who designed multiple rifles in his post within the Chief Directorate of the Red Army, suggests a growing migration of the gun particularly fitting in light of their newfound mobility–particularly the migration of the Avtomat Kalashnikova model 1947, or AK-47, designed in prototype for a 1946 design competition to defend Mother Russia, and which has proved one of the most easily transportable assault weapons of the twentieth century.

Avtomat Kalashnikova model 1947 (type 2)

The arrival in 2011 of the renowned Kalashnikov assault rifle in London’s Design Museum, in homage to the curved grooves of the machined geometry of its magazine, as well as in an opportune expansion of museum audiences by gesturing to current questions of terror, may reflect the prominence of the objection modern life. Its display surely mirrors the central place of the gun the Kalashnikov’s very own eponymous museum in Russia, which also features inviting exhibits like “Let’s recall Afghanistan!”, an anniversary special to commemorate withdrawal from that land–the museum opening was actually attended by its designer, the recently deceased lieutenant-general for the Red Army who designed the assault rifle as an effective arm to “defend the mother country” during World War II.

Far from being a purely historical relic, however, the arm that was designed by Mikhail Kalashnikov, here carrying a copy of the arm he both built and designed together with a group of weapons’ engineers, was intended for arctic combat. But the assault rifle enjoyed huge staying power, or legs: about 100 million of which are currently in circulation globally and some million more are built annually for a growing clientage.

Михаи́л Тимофе́евич

Михаи́л Тимофе́евич

At almost the same time as its designer’s death, the rifle entered the London’s Design Museum, in an attempt to enlarge its “classics” that marks the migration of the Soviet Union’s old Kalashnikov AK-47 assault rifle, now the world’s most popular assault weapon, to the territory of esthetics and museum docents. Whether it belongs in an exhibition in a e Design museum apart, the translation of the automatic assault rifle from the Arctic (where it had been developed) to the battlefield, and from illegal arms markets all the way into a modern exhibition space.

Even if the AK-47 assault rifle is removed from our own tragic familiarity with rifles in the United States, the widespread currency that it has gained as a rapid-fire weapon from central Africa to Indonesia suggests the heinous crimes with which it can be tied–as well, perhaps, of the far greater proximity of the firearm in question to London’s Design Museum than, say, the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York or to MoMA.

Much of this has to do with regional geography. The collapse of the Soviet Union and military famously led such gun-entrepreneurs as Viktor Bout to trade AK 47’s that were Cold War surplus during the 1990s to the armories of African warlords, including those in Rwanda, as he also supplied them to UN peace-keepers there–all from an office he incorporated in Delaware. Using a fleet of retired Antonov and Ilyushin military fighter jets to ferry firearms to Angola, Liberia–where he helped Charles Taylor destabilize the country of Sierra Leone–and Nigeria, helping to saturate the continent with firearms, as well as introduce them with rapidity into the Ukraine. Despite the arms embargo imposed on Somalia, private militias and warlords continued to stock old, unused AK47s.

Viktor Bout

5. To be sure, the trade in firearms is anything but new, and tends to blossom in the aftermath of wars, as materiel is traded privately in what were once war fields to willing buyers. If there was something romantic in how Dutch colonists and traders introduced 300,000 carbines to the Gold Coast during the mid- to late nineteenth century that were marketed by clever munitions suppliers and manufacturers for global export–

An increasingly broad trade in obsolete French and Belgium weapons emerged in Ethiopia in the post-war period that prefaced a new theater of international weapons trading, as arms exporters, revealed by this image of an apparently innocent arms manufacturer who instructs his prospective clients on how a rifle worked. Italian munitions manufacturers soon shipped Remingtons, as Jonathan Grant noted, to Ethiopia as well, setting the stage for global arms exports over the twentieth century that so rapidly accelerated after the end of World War One marked an attempt to contain the growing arms market worldwide–emblematized by the full ceramic sculpture that adorned a Belgian arms factory specialized in the export of arms openly vaunts the circulation of arms it promotes in new markets as part of a civilizing process of instructing locals to develop their relation to firearms.

Lambert Sevart weapons factory in Liege, Belgium, ceramic inlay

Lambert Sevart weapons factory in Liege, Belgium, ceramic inlay

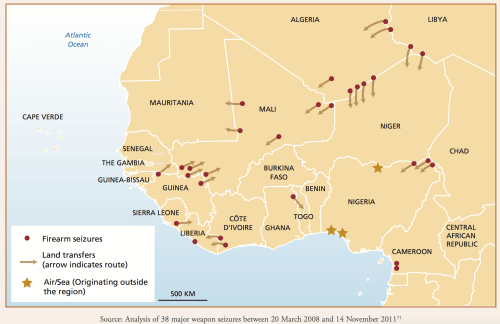

Post-WWII surplus allowed the market to expand wildly, and weapons surplus was recycled and resold in the Americas, with Samuel Cumming’s emergence as a licensed arms dealer, largely stored in Manchester, England and Alexandria, Virginia, in parallel to country-to-country sales of weaponry in the Cold War, when the AK-47 came to dominate the international light arms trade, even as American withdrawal from Vietnam made it heir to two million M16s and 150,000 tons of rifle ammunition that became the basic currency of barter Communist Vietnam circulated to trading allies. As Third World countries devoted $258 Billion to arms between 1978-58, the United Nations Development Program estimates a trade of 8 million light arms and weapons in West Africa alone–a legacy of the many firearms that reached the continent after the Cold War that have continued to circulate to non-state actors (in Mali or the Maghreb) or secessionist movements to use in armed conflicts (as Boko Haram in Niger), or in coups, providing “legacy firearms”–of which assault rifles still prove the largest group, most of which are Kalashnikovs.

Although the flows of firearms are not consistent, UNODC has suggested broad patterns of sale to local buyers, including from Libya’s large stock of conventional firearms.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Report on Firearms–Firearms Flows

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Report on Firearms–Firearms Flows

Based on thirty recent gun seizures between 2008 and 2011, traffic in arms in Africa remained high, fueling warlords, nations and wars alike–

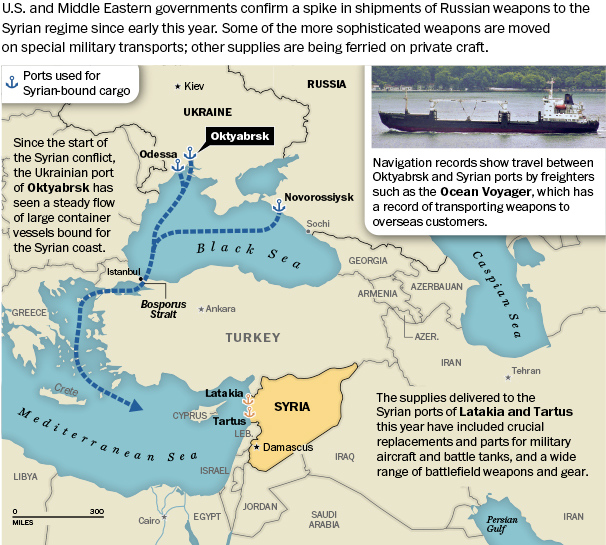

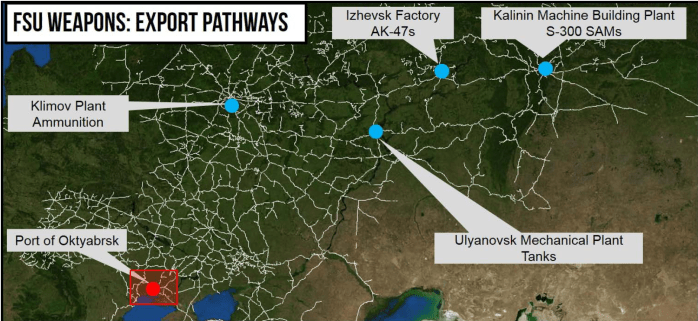

The transport of Russian war materiel on conventional means as ships has allowed a brisk trade in Kh-55 Cruise Missiles with Iran and surface-to-air missiles to Ethiopia from St Petersburg that continued through 2014, and was later replaced by the increasing value of seaports in Ukraine’s Oktyabrsk port as points of departure for arms to Assad’s failing Syrian regime at a considerable swifter arrival time:

The spiking shipments from Odessa and Oktaybrsk remained a vital basis of sending further arms in container ships through the Bosphorus strait–across which refugees still try to move–to Damascus, in a stream of replacement parts for battlefield weapons in the continuing civil war that effectively assures the desperate flow of refugees from their land.

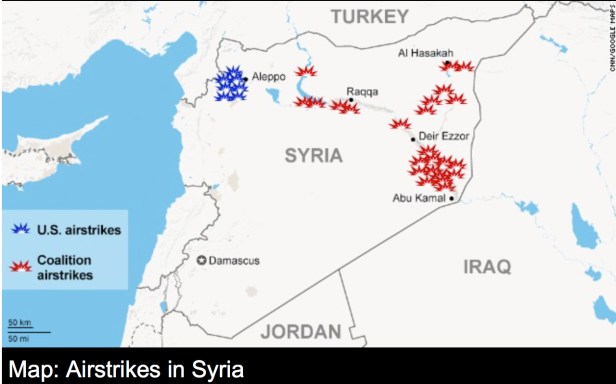

The continued export of global weaponry and related gear that leaves Ukraine to Syrian ports such as Latakia and Tartus constitute a broad geopolitical tactical game, of course, partly hidden, in which Russia is not at all alone–and one that is often engaged through hidden channels, as conventional weapons are disseminated from the US, Russia, Germany, and France to a growing number of client-countries at the start of the second millennium echoes lines drawn during the Cold War.

But the rise of such webs of weapons transport from Ukrainian ports may have been overlooked in calculating the region’s geopolitical value as a transport-hub for the delivery of a range of wartime materiel from tanks, ammunition, SAMs, to automatic rifles like AK-47s to the Middle East, facilitated by a rail network connecting arms plants across a region Cold Warriors know as the “FSU” (Former Soviet Union)–including the Izhevsk factory where Kalashnikov long worked–so that such weapons factories from the Cold War could continue to fill standing orders for shipments from Oktyabrsk. The geopolitical capital of Ukraine as a region may rest in good part in allowing the ongoing transport of war material to a broader range of the region Russia considers its sphere of influence for Bashar al-Assad and others, as well as oil pipelines and the global significance of the region as being a nexus of energy transport.

The networks by which firearms continue to move, and the ease with which they do, suggest something like a chapter in what Tomas Pynchon described as the networks of firearms in the “inexorably rising tide of World Anarchism” in Against the Day, a 2006 historical novel set in the turn of the century, whose global transit of firearms from Mexico to Buffalo to Europe mapped a premonition of the current globalization of multiplying networks of firearms. One thinks back to that fictional seventeenth-century Dutch colonist, newly arrived in Mauritius with his arquebus, Frans Van Der Groov, who stalks the island compulsively in Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, compulsively and systematically eliminating dodo birds to extinction “for reasons he could not explain.”

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

Targeting of Syrian Capital on April 14, 2018/Hassan Ammar/API

Targeting of Syrian Capital on April 14, 2018/Hassan Ammar/API