Can we sustain an argument that the freedom to own guns truly makes us safe? Mapping the question of ownership–and indeed even trying to visualize the terrible frequency of mass shootings in the last forty years–makes any consideration of their violent punctuation of public life question the value of construing gun ownership as a freedom.

The frequency with which mass shootings that clot a timeline of the last four decades is hard to comprehend, save for the very difficulty of how such truly terrible episodes have come punctuate our sense of time. The diminished intervals marking time between mass shootings make the above timeline hard to process or digest–and it frustrates comprehension, but maps an apparent onslaught of apparently unpredictable succession which have so troublingly occurred with increased rapidity in the United States: each mass shooting named once seemed to violently punctuate public space, and set a thresholds for public violence, but in retrospect have almost seemed to collapse as their occurrence and repetition has come to know few bounds in public space–occurring in schools, military bases, public service buildings, or movie theaters–even as few believe that the next mass-shooting would ever occur in the area in which they live. It suggests that the troubling succession of mass-shootings is in itself a crime of human right sand public consequence, far more than they have ever been portrayed.

The timeline is not spatial in orientation, but arranges place names in a disturbing map of America difficult to come to terms with or recognize–it cannot help but raise questions about how we reconcile increased individual access to firearms and individual rights. It’s hard to process raises pressing questions of the ways in which our national landscape is increasingly defined by gun violence, dotted by once-memorable place-names of Columbine, Virginia Tech, Ft. Hood, Aurora, Newtown, or, more recently, San Bernardino–each of which has come to destabilize the way that previous mass-killings once loomed so large in the present, and in our thoughts about gun control. Although it makes one want to bore more deeply into the data, it registers a national landscape marked by gun violence with new urgency. Even as contentious debates are staked about how individual access to guns defines the nation, the simple timeline poses complicated questions about a public arena mapped that seems increasingly mapped by mass shootings. It describes the prominence of gun violence across a national landscape–even though it only lists but thirteen places by name. If chronologies were once used to supplement to maps in the middle ages, to sort the settlement of the inhabited world, the shrinking distances between multiple mass shootings on the over-crowded chronology indeed seem to map a growing public arena of gun use that appear increasingly difficult to physically or mentally inhabit. Yet it is a question all too often marginalized from public debate, and allowed to continue as a truly sick status quo.

Mother Jones/Analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

Mother Jones/Analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

The punctuation of time by mass shootings turns to a terrible continuum in recent years overpowers the viewer in ways that make that landscape difficult to process. Rather than offer a way to mark time, the frequency of what were once treated as discreet events is overwhelmed, as shootings in public spaces that left four dead have ceased to meaningfully mark time, and suggest a geography of shooting guns in public space. From occurrences at clearly marked intervals, the pace of mass shootings suggest a surreal information overload in their bunched crowding that challenges legibility, and even remembrance. For even when distributed on a map, it’s hard to find any coherence in how the clustering of such senseless premeditated tragedies have relentless occurred. Can one even map their social impact or human cost?

Few maps can register their deep costs than the oddly disembodied timeline. As one tries to consider shooting, the pace of shootings across the United States is cognitively difficult to process. The timeline challenges one to comprehend both the toll of the rash of deadly assaults on public space. There is little consensus about “mass shootings”; the timeline charts shootings in public space that left four or more dead. But it suggests how, at a time when gun-related violence has recently declined, the recurrence of mass shootings suggests a landscape we need to collectively confront–and to map against the pernicious diffusion of beliefs that gun ownership are a form of freedom guaranteed by Second Amendment rights–although the frantic pace of mass shootings, illustrating the tortured narratives of shooters, to be sure, but also the problems of examining distinct differences between mass shootings, mass murder, and mass killings in relation to the increased access to firearms.

While some would portray the awful repetition of these tragedies as the cost of liberties, the timeline tracks the truly terrible ease of widespread recourse rapid-fire firearms. Indeed, the horror at the occurrence of mass shootings seems due not only to their horror, but their deep confusion of a militarized and civil space. The dramatically unique scale of gun violence in the United States has led it to be increasingly accepted as a natural fact, to be sure, as many, including City Lab, have noted, leading Zara Matheson to create a brilliant visualization comparing urban gun violence in America to that of other countries:

Zara Matheson/City Lab/Martin Prosperity Institute

The amazing scale of gun violence itself has encouraged the expansion of open carry laws and gun rights protests in America, that have resulted in a similar deep confusion between civil and militarized space. But nothing evidences such a profound and deeply dangerous confusion as specifically or dramatically as mass shootings. And as the profusion of arms in public space grows at a rapid pace, doesn’t the assertion of gun ownership as a right suggest a deep and problematic confusion of civil and militarized space in the deeply disquieting and increasingly public assertion of Second Amendment rights?

Gun Activists Marching with AR-15s at UT-Austin/Getty Images

Gun Activists Marching with AR-15s at UT-Austin/Getty Images

<!––nextpage––>

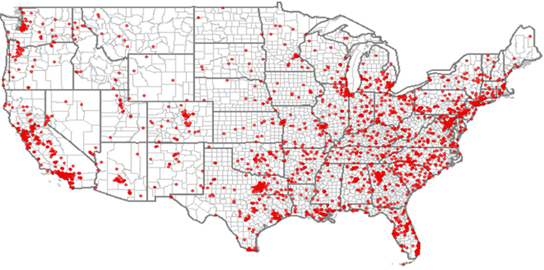

1. It’s not possible to fully comprehend the density of shootings in public places or their especially increased frequency during the past decade–and especially difficult to process their relentlessness across the timeline, which suggests we are in danger of losing count. They suggest a dangerous landscape of public violence that doesn’t seem likely to change. Traumatic shootings which once seemed watersheds of public violence, once viewed in aggregation, reveal a relentlessness impossible to process save as a changed state of events. And while the government has not tracked the rise of mass shootings, or mapped the prevalence of guns in relation to deadly shootings, on-line aggregations of mass shootings and tallying victims confirm a change in public space–closely tied to the ongoing advocacy of gun sales by gun manufacturers who fund the NRA: indeed, the laissez-faire attitude to gun sales are increasingly masqueraded in the United States as a form of liberty in ways that pose an increased danger to public health–that might be more aptly likened to a contagious disease. Mappings of the rash of mass shootings by active shooters in the past three years embody violence in ways that resemble nothing so much as disease maps.

data from Shooting Tracker

data from Shooting Tracker

But the aggregation of mass shootings in the United States seems tragically tied to the flooding of markets with firearms and guns, not only causally, but in terms of the vociferous defense of individual rights to bear and carry arms in public space–as the recent exaggerated expansion of the Second Amendment defense of individual rights–long agitated for by the NRA–suggests.

Getty Images

In ways raw data speaks more than cartographical forms can embody. But only by parsing the rise of such mass shootings from gun homicides and firearm use can we begin to understand the deep confusion and distortion mass shootings have made between militarized and public space, and address or process them by more than shock–or start examine reasons for the considerably greater fear of terrorism, despite the 10,000-fold magnitude between the number of gun deaths and deaths from terrorist attacks, and the wildly disproportionate fatalities from mass shootings since 9/111 than home-grown terrorism. Treating the San Bernardino mass shootings as terrorism is only not recognizing the prevalence of mass shootings in the American landscape, and makes it increasingly important to clarify the presuppositions of mapping mass shootings.

If the extreme gun violence of mass shootings are parsed since Sandy Hook, or since 9/11, or since the threat of terrorist violence on U.S. soil, the collective growth is striking. Gun violence is perhaps not possible to measure abstractly, let alone to aggregate. But the crowding of individual events in a chronology is difficult to process in a timeline that rather than keeping time almost undermine its legibility as a distribution–the very frequency with which mass shootings have come to occur offers pause for reflection. In aggregation, the timeline is hard to get one’s mind around, as if it challenges the viewer. In ways that almost undermines its value as a timeline, the clustering of dates when mass shootings occurred suggests the difficulty to process or clearly map their frequency: public shootings or four victims or more increased in the aftermath of the terrible shooting of kindergarten children in Newtown, PA–guns killed 90,000 since, some 555 children. Rather than constituting watersheds of public violence or tipping points, the Newton massacre and the shootings of Columbine, Aurora, and Virginia Tech suggest way stations of increased violence in an embodiment of collective violence.

The aggregated timeline poses questions as to whether we are watching a pattern of collective behavior in schools, a geography of anger, or an epidemic of public health, and charts a widespread and growing confusion between civilian and military arenas in an era of globalized battlefields–in which the range of “perceived enemies” has expanded off of the map. Aggregates of shootings of four or more dead or injured by guns suggest a similar cognitive overload of data of the dead or injured that we are similarly unable to process in any meaningful way:

Total Gun Deaths of Four or More, based on data of ShootingTracker.com

Sized in relation to local population, a somewhat more legible distribution appears:

But distinguishing gang-related violence from other records on mass shootings a broad national problem of guns:

If we turn to maps to create coherence from the successive mass shootings that increasingly afflict the country, the timeline reminds us most disturbingly of the remove of such events from our own personal responsibility–their relation as traumas remains difficult to start to comprehend, let alone map meaningfully, since they seem so likely to recur and not removed in time. The distribution of mass shootings suggest an undeniable underside, indeed, to the increased insistence on individual rights to carry guns in public space, despite the deep dangers that they continue to pose. For the approximation of continuity in the multiplication of mass shootings approximate a sense of helplessness parallel to the terrifying 350 counted shootings of multiple victims over the past year–even if they are not all mass shootings by any definition.

The intense anger and helplessness behind shooting of multiple unknown victims suggests a striking recourse to guns, however, which currently seems bound to increase with the continued easy availability of firearms. Despite the danger of over-aggregation in light of San Bernardino and Columbia shooting and their mourning, which has almost become its own internet meme, parallel to the sudden rise of training exercises to respond to them, suggest a dangerous desperation to comprehend the scope of gun violence in America by affirming the personal possession of guns–sessions that include the very same sinister design of a public poster devised for a wide morale-boosting campaign by Britain’s Ministry of Information, the government agency charged to design morale-boosting posters during World War II. The emblem, adopted to suggest the difficulty sustaining attacks and civil space in mass shootings, almost mirror the confusion of civil and militarized space in such shootings. Its inclusion recalls a tendency to discourses on mass shootings to migrate to terrains of preparation, as much as prevention: if the original posters were printed in 2.5 million copies, they were largely “held in reserve, intended for use only in times of crisis, or invasion”–and only later rediscovered by a Northumberland used bookstore.

No matter how much we seek to map their incidence, to create some sort of clarity in danger or fear we might better grasp, the bunching of mass shootings–killings where a single shooter open fires ammunition to leave four dead–suggests a shattering of public peace, and civil space. While the rise of mass shootings are called a creation of the news cycle, although their incidence have overwhelmed the airwaves– “And now we turn to this. Here we go. Again.”, the frequency with which incidence of public mass shootings in America have multiplied with the relentlessness of streaming banner news headlines on cable television suggests a violation of human rights. The increasing pace with which shootings of unknown victims occurred in public space seems impossible to clearly compartmentalize, or continue to report, as their frequency over the past two years enters a terrifying continuity particularly difficult to objectify since they assault humanity. Although these shootings constitute but a small share of gun violence, the deeply troubling landscape of mass shootings troublingly parallels increasingly strident assertions defense of firearm possession as a right not able to be legally regulated.

2. Even removed from a coherent geographical form, the sequence of isolated place-names of shooting sites challenge one to confront the landscape of mass shootings in the United States in disquieting ways. The expansion of such shootings illuminate a shifting landscape of guns in public life–even as fewer than a twentieth of Americans regard gun control laws as a problem confronting Americans, and Congress only recently recognized “mass killings” in 2013 as demanding attention from the Attorney General. Even in the light of rejecting restrictions on gun laws or an assault weapons ban, the late identification of such premeditated if unpredicted shootings of unknown victims reveal an increasing accumulation of fatalities, not suggested in the timeline, that . The picture of mass shootings since 1982 indeed suggest a terrifyingly broad distribution across the United States and suggests a failure to responsibly manage firearms in public space.

ABC News/Mother Jones

The increasing occurrence of mass shootings challenges viewers to join several apparently incidents whose totality difficult to cognitively process, moving events seared in our personal memories as if they watersheds in a quick succession whose near-continuum strains understanding as a status quo, and raises questions about how to find meaning in their rapid onslaught.

The crowding of the chronology of mass shootings links dramas that unfolded in different parts of the country in a metaphor of the difficulty to grasp the rate of mass shootings in public spaces: dots designating individual events are difficult to process or parse. Rather than seem individual aberrations, the unpredictable arrival of such mass shootings, grouped collectively, ask us to find coherence in the repetition of mass shootings across America, and to ask why the growing frequency of such shootings is still doubted as specific to our political culture, and relentlessly called into question, rather than addressed, even as tallies of gun deaths have broadly dropped by 30 percent from the early 1990s: the recent surge of mass shootings are not only due to increased media attention to their senseless randomness, but as a threat to human rights.

The reopening of debates about how gun control laws could stop or hinder the geography of gun deaths or scrutiny of shifting gun laws and their effectiveness suggest the lack of clear voice about guns. The variation among regulations about carrying guns in public–and transporting firearms–are even cast by advocates of the individual rights to firearm possession as a jumble of intrusive edicts on transporting loaded guns, ammunition, and storing such weapons by local attorney generals, aircraft carriers, TSA officials, and, yes, national parks and wildlife refuges, as so many “regulatory schemes” curtailing the allegedly protected freedom to own and carry guns.

NRA-Institute for Legislative Action

NRA-Institute for Legislative Action

Rather than consider mass shootings in terms of criminality or individual deviance, the prevalence of mass shootings across America demand to be recognized as a register of the unregulated liberties to carry guns in public space. The timeline in the header to this post is disorienting in how it aggregates such shootings, and poses multiple much-debated questions about understanding their rapid pace over time. Yet the picture of giving coherence to the range of mass shootings across the land is in a sense the reflection of the paranoia of gun protection. Ordering the relative frequency of mass shootings by lone gunmen is itself a challenge to map–and get one’s mind around–because it lacks without any apparent clarity in its growing spread. We often turn to maps to try to find some coherence, but find ourselves similarly frustrated by attempts to find coherence in the growing landscape of mass shootings and not offense. For the pace of mass shootings, once so terrifying in their individuality, has accelerated both since Columbine and since Sandy Hook to make it difficult to not view within a broad change in the use of guns in public settings, conflating militaristic violence and public life, in ways that demand mapping if not to the increased availability of guns, to the ways mass murders might be measured.

The timeline renders it impossible to regard what were once seen as possible turning or tipping points in public violence outside of a context of their collective increase. However much some pundits repeat the conclusions of criminologists about the constant levels of gun violence in America–distorting the distribution of their frequency by including family violence and gang-related fights that constitute a large share of firearm homicides–the increased occurrence of mass shootings on unknown victims reveal disturbing conflations of guns and public space. Even to measure gun violence alone deeply distorts the unique problem of mass shootings, as they are premised on lumping such public shootings with a broad epidemic of gun violence, rather than confronting and visualizing the growing conviction of the legitimacy of firing firearms randomly into crowds without restraint.

Although mass shootings in public spaces are by nature unpredictable, the aggregation of mass shootings offers a way to analyze and recognize the problems of But although the violent level of gun shootings in America have grown, as violence cannot be universally quantified, mass shootings prove difficult to classify or define with uniformity. For mass shootings reveal a unique sort of violence in public. Even when not counting the shootings of family members–the majority of group homicides from firearms, with one in four victims being close family members and over half family members or intimate partner–the increase of public “mass” shootings aimed at unknown victims suggest a confusion of militarized and civil space–and an irresponsible intrusion of firearms into public life, all too eerily mirrored in the attempted seizure of public lands.

The increased anonymity of mass society finds an eery underside in the relentless expansion of mass shootings at unknown human targets in civic space, as if they suggest the fragility of civil society. The numbers shot or killed by high-capacity magazines have defined and will define the country by their very frequency of mass shootings occur in the United States–however vociferously contested is the claim President Obama’s claim that “this just doesn’t happen elsewhere”, the expansion of such shootings reflects an increased absence of regulation of firearms. While it’s not entirely true that only “high capacity magazines put the ‘mass’ in mass shootings”, given the range of gun violence, the peculiarity of gun violence in America lies in the frequency of adopting firearms to wound or murder unknown victims, and the need to better chart the level of violence on For the anonymity of gun violence in America reflects the far greater access to guns in the country, and a broader presence of guns in public spaces of assembly. The expansion of mass shootings illuminate the shifting landscape of gun violence–even as fewer than a twentieth of Americans regard gun control laws as a problem confronting Americans, and Congress took until 2013 to recognize the “mass killings” as demanding attention from the Attorney General, after it rejected to enact restrictions on gun laws or extend an assault weapons ban.

Mother Jones/Analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

The recent proliferation of such mass shootings, rather than raise thresholds for processing public violence, raise questions about reasons for increased recourse to guns, as well as about the perpetrators of crimes. For the striking relentlessness of the multiplication of premeditated crime in public space is truly difficult to comprehend as they approach a deeply disquieting continuity. The term “mass shootings”–only slightly removed form “mass-killings” or “mass murder” that evoke wartime–have no place in liberal society as bizarre conflations of military-style violence, so disturbingly are they removed from a society of laws. Even if exceedingly rare in comparison to gun-related deaths, mass killings by guns have however multiplied in three-fold fashion over the past three years to almost cease to be able to be seen as discrete events as they were once considered to be, as shootings in public spaces by “active shooters” have skyrocketed, as the times between their occurrence declined sharply.

The rise of such shootings has no clear precedent. Although such killings have a clear history and precedent, at times dated as far back as 1891 or even to 1984, the term “mass shooting” first gained currency around 2012, in reaction to the expansion of public shootings, and the classification introduced by the FBI was soon adopted by CNN, who expanded the bar for fatalities in a mass shooting to four, but also excluded events where the victims were related. Only after that did the U.S. Congress in 2013 officially qualify “mass shootings” as single incidents leaving three dead in the Investigative Assistance for Violent Crimes Act, taking responsibility to define the term as part of America–even while refusing to maintain a public registry of such shootings, or adopt this as the sole definition. The relative frequency of their occurrence suggests a deep confusion between civilian and military space that demands to be unraveled, even if the lack of a public registry of such public shootings may soon change, as well as the introduction of greater checks on the purchase of guns. But there is an abdication of responsibility has led to an unchecked expansion of the defense of individual rights of gun ownership–and a dislodging of attention from shootings to the danger of compromising gun rights.

The sense of virtual continuity that approaches in the above timelines are so disordered that it is tempting to find coherence for these unpredictable events in a map. But the collective mapping of such extreme violence is truly difficult to comprehend as they approach a deeply disquieting continuity. Individual stories of mass shootings such as the terrible tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, PA cannot help but bring tears to one’s eyes, as to President Obama’s, as they will continue to do. But the intense the pace of shooting multiple victims–evident in the shrinking intervals between black circles that mark mass shootings–represents a terrible sort of information overload. For it sketches a landscape of mass shootings we’ve been slow to confront, and evokes a sense of powerlessness to interrupt the staccato of their onslaught. Although shootings has, incredibly, relentlessly accelerated since the Newtown, PA attacks, the same event provoked increased attention to mapping and quantifying mass shootings, in an attempt to understand that increased frequency. In spite of the absence of national databases on mass shootings, the rise of crowd-sourced or open-sourced maps since then provide a better dataset of their occurrence–forcing us to confront the increased numbers of people shot or killed by high-capacity magazines, the older demographic of their perpetrators, almost exclusively male, and the greater share children such mass shootings killed, to force us to better examine their occurrence outside the landscape of mourning which has also recurred with increased frequency.

We mine data in hopes to try to impose coherence on the terrifying frequency with which public “mass shootings” doubled after 2007, and tripled by 2011. But such documentation fails to process the landscape of increased recourse to automatic guns. The succession of individual mass shootings fail tell a satisfying narrative about their increasing occurrence. For the collective aggregation of such apparently random acts of violence, the timeline of mass shootings grouped with apparent objectivity, embodies a story that lacks apparent spatial coherence. Although we use maps to process their relation to one another, and to gain a better picture of the proliferation of public violence, the expansion of mass shootings maps a story that eerily parallels the increased availability of guns and assertion of an individual “right” to firearms irrespective of individual rights or public safety.

Similarly, the government has focussed on mass shootings though an optic of criminal investigation, rather than through their victims. Although the government, in an abdication of public responsibility, has resisted tabulating the occurrence of such crimes, and only defined “mass killings”in 2013 as a subject worthy of investigation by the Attorney General, collective tabulation often rested in amassing local police records of ‘active shooter incidents’ as problems of law enforcement, rather than within a landscape of gun violence lasting two to five minutes. The problems of mapping where such premeditated crimes continue to inflict violent injury or death reflects increased access to firearms, parallel to the decrease in urban gun violence. But their senselessness remains difficult to commemorate or get one’s mind around or even to individually mourn.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

The spread of new venues for shooting, however, and the greater availability of guns promotes a particularly dangerous confusion between public space and shooting space, embodied perhaps in the Right to Carry movement, are troublingly apparent in the growth of gun ranges as sanctioned spaces for using deadly weapons, attracting those who want to use firearms–People come in and say, “Oh, I never knew this [sort of] place existed!”–which rent visitors firearms from a Ruger to a and provide practice venues, so popular that websites exist dedicated to where the nearest ranges are to your address. Several perpetrators of mass shootings have not only practiced at such ranges, but they allow targets with images of Obama–as a worker at one range remembered patrons had once used targets showing President Clinton.

<!––nextpage––>

3. The tabulation of such terrible incidents of gun violence where a single shooter left four or more dead from a single shooter–a standard defined in FBI data but not adopted universally–have consistently occurred with increased frequency over the past twenty-five years. The definition introduced by the FBI and taken up by CNN may however, it is widely noted, minimize the scale of these shootings and mask the lack of clear consensus of what constitutes mass shootings–from whether the category reflects fatalities, wounded, or indeed the weapon used. The refusal to tally mass killings, even if they comprise only 1% of all murders, is inadequate to visualize events that shouldn’t even be happening. The gun violence enabled by high-capacity magazines that create a potential of shooting multiple victims have led to a spate of mass shootings perpetrated almost entirely (94% of suspects are male) by white men, mostly between 20 and 45 years old, have alarmingly accelerated since 2005. The difficulty in parsing the changing landscape rests in defining “mass shooting,” quantifying gun violence by its victims, and of understanding the rapid sequence of such truly terrible premeditated crimes.

The multiplication of mass shootings have a fairly uniform spatial distribution, but a geography of anger that invites increasingly military-style assaults on public space. For if they are not clearly tied to globalism, or economic change, the rise of mass shootings in America are all too tellingly linked to a persistent confusion of militarized actions and public space, aptly characterized by Arjun Appadurai as a geography of anger in an age of globalization. Interrogating what invites such a confusion of public and militarized space might generate a clearer geography of mass shootings, lest they seem only random or chaotic scatterplot.

Mother Jones; data analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

Mother Jones; data analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

In part, the overcrowded timeline remains difficult to process adequately because of the very density with which marks that note individual events of gun violence overlap with one another, effacing their own legibility, and the difficulty of giving meaning to violent outbursts in a clear context. The difficulty to discern the individuality among “mass shootings” makes it hard to process the meaning of their frequent repetition. In part, the abdication of definitional categories by the government, and failure of Congress to define “mass shootings” until after the 2012 Newtown, Connecticut shooting opened debate about the proliferation of such violent events, suggest an abdication of responsibility–the government has not only left the media without a clear definition to track their occurrence; we have failed to control the rash of shootings in public space. Although the Newtown shootings led to a number of attempts to aggregate mass shootings–from the Stanford Mass Shootings of America to Shooting Tracker–that placed renewed responsibility and focus on gun violence, and its victims, the absence of focussing on the specific gun violence of mass shootings and how to tabulate its violence outside of a language of criminality has provided an unclear image of its proliferation or its expanse. President Obama, not only acting as Consoler-in-Chief, increasingly adopted the term “mass shootings” in public statements during 2015. We cannot afford to let the disarming pattern of their recurrence remain so very difficult to wrap one’s head around.

And so we turn to maps to try to impose some purchase or coherence on the rage of gun violence, which seems to stand between individual actions and some macabre sort of collective agency. Only ten public shootings in the timeline are identified by place in the timeline above. But the landscape of shootings reveals a violent interruption of public space, difficult to explain or comprehend–both in terms of the increased frequency of mass shootings since events like the Columbine shootings, or the Newtown Shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary, just three years ago, or the subsequent multiplication of mass shootings whose frequency almost seems not to permit time for processing the memory of the dead. Even in an age of growing global violence, because it is so hard to get one’s mind around a landscape where public mass shootings have continued to multiply across the land, and their danger goes unaddressed. The renewed popularity of trainings to survive mass shootings continues to affirm the individual right to possessing firearms as a solution to contain violence–rather than recognize the pathology of gun violence that confuses military-style shootings and public space.

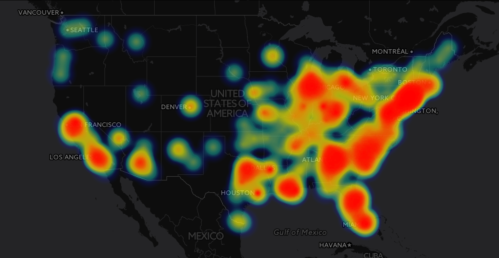

Yet the frequency of the recurrence of mass shootings is difficult to process in part because of the lack of a clear database for either the crimes and weapons with which they were perpetrated–resulting in a deeply troubling longstanding blind spot in processing the landscape of recourse to guns. The troubling reluctance to tally mass shootings–or to associate them with guns–has been clouded by a reluctance to identify the violence particular to gun crimes. Yet increased numbers of crowd-sourced or vetted counts of mass shootings illustrate a landscape of a terrifying proliferation of violence difficult to get one’s head around, in which the late 1990s constituted something like a watershed, but by the last ten years proliferated in increasingly troubling ways, in a geography of anger that a time-lapse visualization reveals, compressing monthly tallies over fifty years that increasingly stained the nation by blotches of bright red.

https://tbridges.cartodb.com/viz/bce76468-21ae-11e5-89f4-0e4fddd5de28/public_map

This count is an underestimation that does not include mass-shootings involving family members, which amount to a quarter of the victims of mass-shootings, and the majority of such shootings are family-related. Interrogating what invites such a confusion of public and militarized space might generate a clearer geography of mass shootings, in Appadurai’s terms, might however gain better purchase on their occurrence and indeed the fear of further mass shootings in America.

The proliferation of such premeditated public gun violence across the nation was enacted with complete lack of empathy and arrogant privilege. Although the recurrence of mass murders in America may have created changing thresholds of public gun violence in the country, particularly since the Columbine massacre in 1999. When the sociologist Ralph Larkin suggested the emergence of a “cultural script”–a model for shootings inspired by the violence of earlier killers–the suggestion paralleled vigorous public debates as to the ethics of continued identification of perpetrators on television news and the coverage of their manifestos. But the ethics of tallying the geography of this spate of mass shootings and the landscape it presents is not only as important for the image of the nation that it presents, but for the difficulty of finding any coherence in episodes of public gun violence, at one time rare, but now extending from sites of public congregation from movie theaters to schools to public clinics to on-air news shows.

The problem of tallying mass shootings, after all, is a problem of confronting the extent of gun violence in the country by visualizing the ways that mass shootings, if a small percentage of gun-related deaths, compromise public safety in unacceptable ways with increasing frequency. So much is revealed in the increased prominence of the number of mass shootings staged in schools since Newtown alone–

School Shootings in the United States since 2013/Every town Research

or the predominance of children among victims of mass shootings–

Mass shootings are increasingly publicly staged as a perverse taking of justice into one’s own hands, not only as increasing guns have entered circulation, but as the diffusion of firearms equipped with high-capacity magazines has changed the landscape of gun violence. Despite a partial slowing of their occurrence after passage of the Assault Weapons Ban, in place until 2004, most public shootings occurred with legally purchased guns–80%. If many perpetrators betrayed signs of mental health problems,this did not obstruct the legal purchase of guns with high-capacity magazines whose rapid-fire capacities that the black dots marking shrinking intervals almost emulates in its chronology of violent crime, whose staccato approached near continuity at several times ov re the past ten years. If such violence parallels a growing global violence, the painful punctuation of time with public mass shootings, tabulated as a single gunman leaving at least four dead, suggest more than a cultural script, but a geography of extreme rage it is important to try to confront.

Mother Jones; data analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

Mother Jones; data analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

The increasingly crowded chronology reveal an increase in episodes of public gun violence with multiple victims, whose occurrences become difficult to individuate form one another their repetition is so dense. Yet a clear consequence of such mass shootings is in the geography of fear: on the heals of individual mass–shootings, surges in the sales of firearms have arose–recent sales have increased across Southern California in the aftermath of the San Bernardino shootings, in the manner that gun-dealers were quick to report increased requests for weapons after earlier mass shootings as Sandy Hook to two million guns a month. And once more, firearm purchases have surged.

<!––nextpage––>

4. If we are apt to interpret the increased spate of shootings as a sort of crowd psychology of negative role models, the tacit dialectic between mass–shootings and gun sales demands mapping as an intersection of a spatial imaginary rooted in the defense of rights to possess firearms and the expansion of further firearm sales–a landscape not of increased gun ownership, but of an expansion of the misunderstood “right” to bear arms. We are more ready to accept workshops for training in behavior during mass shootings, as if to accept them as a new normal, than to enact laws designed to staunch the sales and circulation of firearms.

For the expansion of mass shootings in America has grown in the face of a lack of official government counting of their occurrence, and a blind spot and self-imposed reluctance to monitor or disturb the alleged “right” to bear arms. Although there is unclear evidence that the ban on assault weapons limited the growth of gun violence or murders before it expired in 2004, despite reported reduction of guns in circulation at shows and gun sales, the promise and hope to reinstate the plan led to a defense of gun rights consolidated in 2008 by the Roberts court. The Court’s somewhat surprising defense of gun possession as a personal right paved to an increase in circulation of guns in America that mushroomed first to one per citizen, and approximately 310,000,000 million firearms as of 2012–114 million handguns, 110 million rifles, and 86 million shotguns–or more than the number of Americans. At the same time, the expansion of AR-15’s in American hands beyond 3,750,000 by late 2012–with sixteen million new guns circulating in America by 2013, as detailed in the tenth (and almost self-standing) section of this post. Industry analysts of gun and ammunition manufacturers–who donate part of their profits to the NRA, mean that the panic-buying after each mass shooting regularly accelerated and “went vertical,” driving new monies to the NRA.

The full-throated defense of gun-ownership as a right, long asserted by many pro-gun groups, was endorsed that parallel the expansion of a landscape of illegal gun shootings and the multiplication of mass-shootings over 2015–in what President Obama recognized as “a pattern . . . of mass shooting in this country that has no parallel anywhere else in the world.” Rather than the chronology of mass shootings only reflect an inexorable rise of anger or a disembodied landscape of emulation of bad role models, this post suggests the need to embody that landscape in the dramatically increased right to protect individual ownership of guns. that provide a background for the four-fold expansion, by one count, of mass shootings in America from 2008 to 2014: the expansion of gun sales triggered by Obama’s 2008 election encouraged shops to restock firearms anticipating Obama’s re-election, which indeed spiked sharply after Newtown, when a surge in the circulation of firearms occurred which demands to be mapped.

Have the costs of such a resurgence of guns in America already born costs?

The extraordinary expansion of such newly identified events as “mass shootings” suggest a failure to map a landscape of gun violence. The increasing frequency of such murders renders it almost impossible individuate these terrifyingly militaristic event as discrete; their aggregation overwhelms its own very symbology, as if echoing the deep difficulty to interpret their troubled narratives with any coherence. The frequency of public mass shootings in America offers a mirror particularly difficult to confront. We search of more coherent answers in maps–but are frustrated at the meaning of the apparent proliferation of mass shootings since Sandy Hook attacks directed public attention to attempts to contain future gun violence while respecting Second Amendment rights–

–and inspired the public record-keeping that had long lacked to provide a clearer image of the expanse of gun violence across the country that has led President Obama to act with a “sense of urgency” to enact gun control measures in ways consistent with Second Amendment rights–even as his opponents return to possible impeding of Second Amendment liberties as a nefarious design needing to be met by their active protection.

4. Have we have allowed a clear popular distortion of individual rights to possess guns that obscure the multiplication of mass shootings, and landscape of gun violence, distorting the rights of gun ownership as a constitutional liberty, leading to a refusal to monitor or control access to assault rifles or handguns? By failing to register the relation of rapid-fire guns to crimes, curtailing background checks, and invalidating any bans on the restriction or ownership of handguns, the founders’ call for a “well-regulated [state] Militia” was re-interpreted as an individual prerogative to have unrestricted access to firearms, irrespective of the growing threat to public safety.

Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence

The timeline at the header to this post challenges us to map memories of individual shootings in schools, movie theaters, public buildings, or auditoriums in an abstract form–and process the reasons for their collective acceleration over time. Each episode of violence suggests less a fixed ‘place’, of course, than the extent to which extreme gun-violence intersects with the nation; the collective list challenges viewers to process the collective impact of a new landscape of gun violence in public space, almost 80% of which involved legally purchased guns with high-capacity magazines, and to explain the reasons for the distribution of an undeniable epidemic of public shootings in civic space. Much as the extension of railroad lines earlier placed locations “on the map” which were earlier unknown, the occurrence of mass shootings–by no means consistently defined in the United States, and based on an old FBI classification since abandoned–puts a town at the intersection between a near-epidemic of violence and civil space.

The sites where mass shootings occurred have entered public memory, even if no clear consensus has emerged on the notion of mass shootings. Although its value for registering gun violence in America has been questioned, the terrifying prominence of the increase in such public performances of violence has led to increased interrogations of what has allowed (or facilitated) such explosive violence that have been relentless over the last few years. While we have watched a procession of deer-in-the-headlights photos of perpetrators or examined the eyes of Facebook portraits for clues, the aggregate acts of such violent aggression can’t be seen as an aberration. The overlap between public instances of gun violence that left four dead is difficult to process both as a loss of individual lives, and epidemic of violence for which no clear end seems in sight: the telling contraction between shootings in which four or more were killed have come to overlap with one another to make them illegible and impossible to process as a whole–the crowded timeline of violent outbursts overwhelms in ways difficult to process or understand, in part because it removes the increase of mass shootings from a broader context of refuting local restrictions on the possession of guns in 2008 and 2010, as the widespread reluctance to revisit the lax regulation of gun ownership encouraged a belief in the “right” to own guns.

Mother Jones; data analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

Mother Jones; data analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

Tabulated by mass shootings/month, a terrifyingly clustered repetition–if less clearly as a visual metaphor for the difficulty to grasp the frequency of public shootings’ occurrence–returns. There has never been a break for more than three months in a public shooting that left four dead over six years–breaks that only occurred two times. Although the shootings cluster, and little coherent pattern exists among the rampages,

their occurrence raises questions about the increasing intersection of gun violence and public life. Even though “mass shootings” comprise quite a slim percentage of gun violence, to be sure–

–the persistence of mass shootings with terrifying regularity raise inevitable questions about their future role in the country’s public space, and hint at a future of violence in places where violence previously had little place. Is there something like a tipping point about the diffusion of mass shootings in America, or are we powerless before their spread?

Although mass media has returned to the dramatic setting of public mass shootings as tragic losses of life, we fail to process them as fragments of a national storyline, since their narrative coherence is poorly understood–what coherence can be imposed or read in their distribution remains unclear. The unpredictable sequence of such heinous crimes staged by individual shooters have only come to be collectively defined, and given coherence by being mapped in ways other than numbers of killed. Though the mass shooting was not included in the FBI’s Crime Records Reports, the mass shooting has come to resonate with a topography of fear in an age of the perceived rise of terror; if questions have been raised about whether mass media reporting may have increased copycat crimes, the crowded landscape of sites of public gun violence paints a frightening image of America, at the nexus of law enforcement and legal rights of gun ownership, but creates a landscape of its own.

The resonance with which each place-name appears on the crowded timeline suggests the growing difficulty to process the seventy-three of such identified events over the past thirty years, and rapidity with which have arrived in sharply decreasing intervals; as much as a landscape of increased violence across the nation, the mass shooting has become a way of marking time of increased fear–whose crowding as a collective chronology above, reprinted from Mother Jones, based on three decades of data and research from the Harvard School of Public Health on shootings in public space, suggests a random reputation of lives lost. We turn to maps to try to process them. But the increased frequency of mass shootings intersects with public space in these data visualizations, made and remade in attempts to understand whatever coherence they might have or invest coherence in their occurrence fails to reveal clear meanings–even against our intensely fractured political climate. And after each shooting since Sandy Hook, gun retailers celebrated a “real surge” in sales that was widely championed by gun manufacturers.

The distribution of mass shootings blankets America whether measured by their occurrence or the number killed by such public violence, in ways that define the country in curious ways but they hold a mirror to the country we do not like to recognize.

Stanford Mass Shooting Archive/Open Street Map/CartoDB

5. Even the recognition of the phenomenon has been deemed too contentious to adopt, we use crowd-sourced web-based tabulations and open-source aggregations from non-profits like Shooting Tracker or Gun Violence Archive to track their occurrence and geographic distribution in the country. Both websites have tabulated their incidence less with reference to an “active shooter” who is “actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people” in public space determined by the FBI to describe “mass murders,” as if to hesitated to link them to a weapon of choice. The tally of mass shootings has been only recently construed less in terms of the incidence of deaths–as tabulated by news agencies as CNN or the FBI–but includes those injured, rather than only those killed. The timeline however exclusively marks public shootings that left four or more dead, excluding the gunman. But multiple different definitions about what constitutes a mass killing can however lead any tally to vary and arrive at radically different results; the ongoing lack of consensus in the term as an analytic tool makes it difficult to agree on how this data, and make us depend on non-profits for accurate counts beyond that of news agencies. (Does a ‘mass shooting’ reflect the number shot in quick sequence (as it does for Shooting Tracker), four or more killed, or only multiple shootings? Should the category exclude robberies, gang-related violence or domestic violence?)

The results can be so radically different to suggest radically different landscapes of public violence, and rely on different triangulations between perpetrator, victims, and gun, which reflect contentious debates about relations of gun control and such shootings. But all try to visualize the undeniably growing intersection between such apparently random outbreaks of gun violence and public space, to try to create meaning from such tragic and not-so-sporadic outbreaks of public violence. The significant difficulty of cognitively processing the growing frequency of public mass shootings occurring at one time and site–let’s say only killings of four or more unrelated individuals at one site–so overwhelms as an information overload alone, to demand careful consideration. In part, the events seem too traumatic, most still seared in our personal memories, to be able to be distanced with clarity. Even when stripped of geographic location, each place-name invites us to place our personal recollections of what seemed altering shootings in a collective context that lacks clear coherence.

Although the timeline in the header is not at all an actual map, per se, each place-name triggers indelible if temporary ruptures of civil society, asking us to try to abstract them as a coherent whole; rather than seem discreet moments, they assume a collective resonance that’s terribly challenging to process–the relation between the distribution of mass shootings to our sense of the space civil society is pressing, but quite difficult to define, even as mass shootings have undeniably multiplied to 375 over the last year, including four or more killed or wounded, in a combination of imitation and increasing violence over a year which at its close was dubbed “year of the mass shootings.” And only a small number of such events had there been concern about the mental health of their perpetrators expressed to medical practitioners, school officials, or legal authorities–and if concerns were expressed about just over one tenth of perpetrators, fewer than 1% were actually legally barred from buying guns.

The quick succession of mass shootings in the timeline of course forces us to ask their relation to one another, and expresses the cognitive challenges of getting one’s mind around them–and questions whether a map is even the best medium to track the spate of violence of mass shootings, even as it makes us turn to a map to locate them in space. The difficulties of visualizing mass shootings lies only in part in the limits of reporting or classifying outbreaks of gun violence occurring at a single site as “mass shootings” by fatalities versus the number of wounded or shot–as if to count as an event that is newsworthy, an individual must die–but in making sense or coherence of the rash of these explosions of violent gunfire across the land. The chronology lists mass shootings that left four dead but also evokes the very extent to which this past year’s onslaught of mass shootings in ways cognitively challenging to grasp, as their ever shrinking temporal separation approach near-continuity. If each dot indicates a shooting without reference to space, their accumulated density maps a geography of anger. For much as the place-names clustered with such density on the timeline, they are cumulatively less and less easy to grasp as singular events: mass shootings punctuated the last two decades with an intensity difficult to process such occurrences better–making one turn to a map to endow coherence to the unpredictable outbreaks of indiscriminate shootings across the country with little end in sight.

The aggregation of public gun violence suggest not only a geography of fear–and an undeniable overlooking of anger–but reveal a particularly insidious misinterpretation of gun ownership as a right in legal discourse, as much as the tally of mass shootings is filtered through debates on gun control. The disembodied dots that dizzyingly crowd the timeline mimic the rapid-fire of bullets delivered by assault weapons’ replaceable magazines. Despite continued unresolved debates in political discourse about how to gloss the spread of mass shootings in a country where it is so easy to procure guns, the contested interpretation of the map may betray a deep reluctance to confront their pervasive occurrence, and ask what sort of story their increased incidence, perpetrated almost entirely by young, white men–94% of suspects are male–suggests.

For the spread of mass shootings as a category eerily parallels a crisis, suggested by Dorothy Samuels, in American legal discourse as to the right of individuals to “bear arms” as a right without government oversight. While many perpetrators, to be sure, displayed signs of significant mental health problems, the multiplication of mass shootings has been facilitated by legal sanctioning of individual “rights” to own guns since 2008. The defense of such “rights” not only actually encouraged the proliferation of millions of guns in the United States, but generated a political discourse, long-planned by the NRA, about gun ownership that made reinstatement of either research on gun violence or curtailing of gun sales anathema.

Even without focusing on perpetrators and their weapons, the landscape of gun violence poses questions as to what the aggregation of “mass shootings” reveals. For even when excluding shootings that result from domestic violence in the home–perhaps unconscionably, given that a quarter of victims of multiple murders are family members and the majority of group-killings stem from family violence– the distribution of the data is terrifying as a rewriting of the use of guns in public space. We are used to watching zones of war in television films, video games, and movies, but such mass shootings of four or more are difficult to process because they have occurred in spaces of public life: health centers, schools, auditoria, film theaters, medical clinics, public buildings, or even the television news–as if to openly attack sites of public assembly.

News stories about mass shootings have remained prominent since 2011, ranking in the top five stories in repeated years, lending familiarity to the term before it was defined by Congress in January, 2013 lowered the threshold for identifying “mass shootings” to three victims. Data visualizations that “map” the accumulation and relative density of mass shootings present a landscape that we are just starting to learn to measure. Although”mass killings” were first defined by the FBI, the adoption of “mass shootings” by news agencies as CNN or ABC left unclear consensus in how they are counted or conceived. Indeed, while deeply disturbing, the ethics of a CartoDB heat map, which blur shootings to obscure individuality, are unclear, if terrifying; their distribution here approximates a disease map, but one particularly challenging to process–as if a miasma removed from the nation.

–and aggregates data to suggest their wide distribution in populated areas, without any meaningful clarity. The rise of such public displays of mass violence, if constituting only less than 1% of all gun violence, can’t help but suggest a deep instability within the nation–irrespective of place. The aggregation of mass killings raises questions about attributing mass killings to a failure of mental health providers or shifting thresholds of violence of mass behavior–and, indeed, the thresholds that the country is able to process. But the distributions with which mass shootings have occurred in America increasingly seem to define questions of the possible intersections between the site of the mass shooting and public life that are barely touching, but always in danger of overlapping.

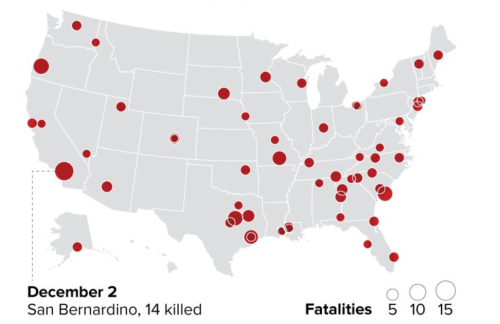

6. The national timeline presents an image of the nation hard to ignore, as if a creepy causal network of mass behavior. The difficulty in mapping such violent outbreaks seems due to the reminder that they offer of how difficult mass shootings are to prevent, and how ubiquitous they have become, as revealed in this map tallying victims of mass shootings over the past year alone, but whose legibility is also obscured by the failure to count wounded and fatalities of four or more to tally the multiplication of mass-shootings over the past year of 2015–“a pattern . . . of mass shooting in this country that has no parallel anywhere else in the world.”

or sized by shootings with three or more fatalities–

The year was so grim, and so tragic, in the series of shootings that we are still trying to get our minds around and to process, as shootings occurred almost daily over 2015, that we may be near a tipping point in processing their immensity.

A chronologically collapsed aggregation of the wounded and dead in mass shootings that occurred since the Newtown shootings of 2012 make it impossible not to acknowledge their prevalence across America–in ways not limited to a tally of four dead, but that includes all dead or wounded:

The profusion of such violent events with guns contrasts to the twenty-eight states which had not seen a mass shooting incidents from 1984 to 2012–a number that in 2015 shrank to but five, making this earlier landscape look far removed from the nation’s current state:

Citizens Crime Commission, “Mass Shooting Incidents 1984-2012”

Citizens Crime Commission, “Mass Shooting Incidents 1984-2012”

The pronounced expansion of mass shootings across both space and time suggests a boiling over of rage across America that such aggregations only force us to start to process. While such killing sprees were initially termed “rampages” or “mass murders”, the increased currency of the very term “mass shootings”–only slightly removed form “mass-killings” (preferred by USA TODAY, who include killings of family members) or “mass murder” (which cannot help but evoke wartime settings)–suggests a disquieting difficulty to place such conflation of military-style violence and public space in a liberal society– and the troubling sense that this is approaching a new normal. Even though the polarized nature of political discourse about gun control make it increasingly difficult to resolve.

7. There at first seems little coherence offered in such maps, and a powerlessness that any action might soon slow their future occurrence–the maps overwhelm one with a feeling of impotence, as if “this was a terrible tragedy but somethings these things just happen and there’s nothing anyone can do to stop them”. Rather than only create an image of a blood-splattered segment of a continental mass, or a record of psychic disturbances or mass behavior, the images might suggest the spaces that have been opened for mass shootings across the United States which increasingly pose undeniable challenges to human rights. The shootings are deeply misunderstood as individual cases of psychic disturbance, even if they demand to be understood more clearly as a crisis of public health.

Individual attachment to guns may, insidiously, enable this rash of violent subtractions of self from a social compact. For the challenge to visualize such violent shootings in public space collectively–and the deep threat and instabilities mass shootings continue to pose–resonate not because they are a large proportion of homicides (fewer than 1%) or gun violence (fewer than 5%), but because of the deep shock they pose to civil society. Even if the attention to the number of mass killings may distract attention from the real danger of guns, including “slightly modified combat rifles” enough to be “red herrings” in the debate on gun control. USA Today stokes fears by reporting that mass killings in fact “happen far more often [my italics] than the government reports,” even if shootings in public spaces account for about one-sixth of mass shootings, the events are so disturbing because they blur the boundaries between military action and public space too common in today’s world.

The relation between the space of mass shootings and the inhabited world is in a sense the subject of all maps of mass shootings. There has been a dizzying crescendo of shooting sprees in the over the twenty years since the concerted defunding of the CDC’s study of gun violence in America in 1996, believed to “advocate or promote gun control” or defamed of doing so, and the silencing of research on gun violence. Since the decision to direct the 2.6 million that the CDC invested in studying gun violence to the less-contentious research in traumatic brain injury, the rise of open-source mapping of the mass shootings in America reveal widespread proliferation of military-style gun violence across the national landscape, as if to direct increased attention to the problems of processing a problem from which government funding disappeared. This is a victory of crowd-sourced mapping.

The onslaught of gun rampages that cause multiple murders and injuries overwhelm, and the clustering of mass shootings in the past ten years to make it impossible to see them as only discrete events: the virtual continuity that they assumed, as space shrunk between shootings, raises questions of the future and they can be meaningfully processed in a map. Even as we turn to map their occurrence to find some explanation and meaning from such senseless and only apparently unrelated events. For although unclear commonalities emerge in their place, their targets, or their scope, they suggest an increased ability to view the level and site of collective instability in the nation. The distribution of mass shootings over time hence provides a disquieting image of increasing instability of civil society, and demand to be mapped against not only against gun ownership, but against the defense of rights to own guns. For even although the legality of gun ownership is recognized by courts, nothing is more disturbingly removed from a society of laws than mass shootings.

The term “mass shootings” was only recognized by Congress as they qualified “public mass shootings” as leaving four dead, the FBI had recognized the rapid pace at which public mass shootings in America doubled after 2007, and tripled by 2011. While a small proportion of gunshot deaths, or the 51,ooo incidents of gun violence over the past year, mass shootings assume particular prominence within the national consciousness from such events–if they undeniably follow the same general distribution with other geographically weighted concentrations of gun violence.

Stanford Mass Shootings in America (SMA), courtesy Stanford Geospatial Center and Stanford Libraries, as of October, 2015

Even as gun violence has overall declined, the spread of mass shootings suggests a changing picture of America that is still being more clearly processed. In part, this is because the term “mass shooting” has been defined by the media–both CNN and other television networks–although it was first developed by the FBI to tally criminal acts of murder. In recent years, it has been diffused and developed via the mass media, and specifically the ever-multiplying banner headlines of cable news, whose counts are directed to define them by the number of those killed–four or more dead defines the “mass shooting.” The attention to those dead, omitting those victims who were injured or escaped violence, both reduces their appearance on a data map, rather than, say, numbers of those killed or injured or the number of bullets that were shot, diluting the aggregations that such shootings map and making them mortality counts , rather than gaining perspective on them episodes of gun violence. And it distorts how the geography of mass violence and that of civil society overlap.

Reference to “mass shootings” as term of news reporting by CNN (who excluded events where the victims were related to each other) quickly followed, but the time to required for the term to gain currency raises questions about the difficulty to process the new thresholds of such extremely disturbing public acts of violence–USA Today prefers to use “mass killings” instead. As mass shootings recur with a rapidity to mimic the banner cable news headlines on CNN, where they were frequently announced, one is challenged to process their totality and staccato occurrence alike, given their actual broad geographic distribution. Because of the prominent suggestion of serious mental health problems of many perpetrators, we often fall back on diagnoses of individual instability to explain each tragedy that registers in the national consciousness, the huge spike in aggregate mass shootings after 2000 which jumped again from 2013 can’t be diagnosed by individual disturbances or the categories of the mental health profession–so long as gun ownership remains recognized as an individual right. And yet the mass shooting suggests a deep assault on human rights.

A recent study of the thirty most violent mass shootings since 1945 found more than half occurred in the last decade, and their proliferation seems to have alarmingly grown in recent years We turn to maps to struggle with the difficulty of comprehending events of terrible particularity in the aggregate. Despite the terrifying nature of each place-name, which evokes a specific time and tragedy, as if a series of battles, aggregation offers the possibility of drilling down into their occurrence underneath the accumulation of horrific individual stories. Yet we struggle, since even a map of mass shootings including four or more killed or wounded during the past year poses similar cognitive difficulty to process:

Is this an accurate reflection of the country, and what does it tell us about its laws and legal discourse on gun ownership and possession? Although the mass shooting is still an anomaly, it is also part of a difficult to confront part of our nation. For the right of personal possession of guns is so difficult to remove or qualify in the United States, and so difficult to prevent rights to gun ownership to be so tragically misconstrued; if most of the guns purchased for these public shootings were done so legally, the lawlessness of the events is not able to be correlated only with guns, even if the changing landscape of the broad availability of guns seems to have created a space where individuals are all to ready to conflate civil space with a space of violence. Part of the difficulty to process these ‘events’ surely is that we focus attention on their perpetrators, as much as their victims, reducing the dead to a statistic, and not comprehending their violence:

<!––nextpage––>

The prominence of mass shootings illustrates a confusion of public spaces with military-style gun violence in disturbing ways. For the spread of individuals who have not only subtracted themselves from civil society, but turned to gun violence as a public performance, suggests not only aberrations; the aggregation of such shootings reveals the increased prominence of military-style violence staged within public space, and forces us to view their dizzying repetition within the national landscape. The geography of mass shootings still remain poorly understood by most: although about a third of the victims were near their homes when the shootings occurred, fewer than a quarter of Americans believe that there is reason to fear a mass shooting in their neighborhoods, and a fewer than a twentieth see gun control laws as a problem confronting Americans. Indeed, if Congress only recently recognized the mass shootings in 2012, as increasing numbers of lawmakers forced to confront their occurrence in their home districts, but many affirm the rights to own guns. And in 2015, only five states were spared mass shooting sprees–“the bloody, perpetual series of mass shootings in the country this year,” as ABC News put it, no doubt reflecting mass-opinion, and the sense that this steady accumulation may have reached something of a tipping point.

8. Even disembodied from a geographical form, the sequence of haunting place-names captures the degree to which mass shootings are cognitively difficult to process in their totality, and the complex shifting landscape of mass shootings they create. For the spectacular violence of each event is encouraged by the deep and abiding sense that the exceptionalism of America that is increasingly rooted, for a small if vocal minority, in its ownership of guns. The timeline forces us to confront the increased crowding of mass murders over twenty years not as aberrations, but through the inability to continue to segregate them as inexplicable tragedies apart from a larger picture of the nation. If we turn to maps in attempts to create a more coherent image of their coherence, since the frequency of mass shootings seem without any clearly recognizable patterns in such unimaginable violent aggression against four or more, as if civil society seems no longer able to contain its members.

For the aggregation of mass shootings presents an image of the United States we have difficulty recognizing as holding a mirror to the present, when amassed in their collectivity, and to search for answers for acts that so sharply run against the very fabric of civil society. We have repeatedly turned to terms like “disturbed“, “delusional“, “psychotic“, “sociopath“, or “undiagnosed schizophrenic” that continue to be bandied about in the wake of successive shootings–as if a diagnosis could prevent such events. But in offering clinical explanations for the violent tendencies so dramatically exhibited by their perpetrators, rather than explain the sequence of mass shootings which dramatically grew after 2000, and after 2013 rose so dramatically that over a thousand mass shootings occurred in the two years since Sandy Hook, with little change in background checks, to demand a collective mapping that a focus on mental illness denies. The array of weapons used in such killings raises pressing questions about their perpetrators’ access to assault rifles, but similarly fails to map reasons for this anguished performance of public violence against lives–

If poignant stories of the mental instability of those who committed rampages since 1984 force us to revisit possible counterfactuals, mass shootings may be less easily collectively diagnosed than mapped against legal discourse of gun ownership and freedom to own guns. For recent and widely reposted data from Mother Jones suggests that most of the guns used in mass shootings over the past thirty years were legally purchased, raising questions about their contingency. The rights of gun ownership on which our laws insist are embodied in conceal-and-carry permits, the rhetoric of gun ownership, and growing defense of rights to gun ownership as individual rights protected by the Bill of Rights and US Constitution–which have discouraged a public recognition and accounting of gun deaths. Although many of mass shootings occur in places not known for violence, the continued championing of assault rifles behind the empty slogan that “the only way to stop a bad guy is a good guy with a gun” valorize the weapon in ways that exculpate public entities or gun salesmen–protected by the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act--from responsibility of mass shootings’ occurrence: the shifting of responsibility too easily comes to fall into the domain of mental health, without looking at the dangerous opening created by an immobile legal discourse on gun ownership and firearm use.

Can the rise of mass killings be mapped within the access to guns that current laws permit, and the rhetoric of gun ownership that they unknowingly promote? It truly is unconscionable to see “firearms” as identical, despite the quite different uses to which they can be put?

Although the sequence of mass shootings tallied in the header to this post follows no predictable pattern (save to rapidly increase) and geographical distribution seems happenstance, the growth and unpredictable nature of mass killings demands to be mapped other than psychiatric labeling and armchair diagnosis. For black-boxing the spread of mass killings in questions of individual mental illness neglects to map against a changing discourse on the ownership and personal possession of guns and abnegates collective responsibility for the density of the clustering of these violent episodes increasingly part of day-to-day life.

Mother Jones/Data Analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

Mother Jones/Data Analysis by Harvard School of Public Health

For “mass shootings” have so rapidly and dramatically accelerated during the past decade to overwhelm understanding. Indeed, the turn to map their occurrence provides a basis to distance oneself from the terrible occurrence and find some purchase on what seems less a Hobbesian state of nature without government, but a conscious remove of shooters from civil society. The rise of mass shootings in public places, although but a small fraction of all gun-killings, makes us want to map them to make sense of their inexplicable violence, to give some coherence to the sites of such deeply shocking events, as well as gain perspective on them. For although fewer than a quarter of Americans fear that they live in a neighborhood where a mass shooting might occur, the landscape of mass shooting has become an image of America. And if ShootingTracker.com and Gun Violence Archive have crowd-sourced statistics on all gun violence since 2012, to create a picture of the country, the image of mass shootings are both more complex and difficult to assess, partly because of their removal from and far deeper shock to civil society.

The more apt coloration of such data from KQED may better suggest the haunting by the dark spectre of mass shootings overwhelming the land:

Rather than being chaotic disruptions, the increasing chronological clustering of individual mass shootings suddenly appear as a connected group of events, whose quick succession both challenges the integrity of their remembrance, but seem cognitively challenging to grasp or gain clear bearings on. Even as the pace of gun-violence has decreased, the prominence in national news and consciousness of the mass shootings, and the prominent display of murderous violence that parallels their prominence in the national consciousness has created a new landscape of American violence and fear. Such apparent singularities have grown in the shadows of a country overly preoccupied with attacks of foreign terrorists or extremists, despite the greater than thousand-fold likelihood that between being killed by guns than a jihadist attack on American soil.

Is it possible we have decided not to look for the best ways to map and understand such violence as it has spread? Or is the confusion of civic and military categories part of the difficulty of comprehending the logic or pattern of mass killings in the United States? For the landscape of mass-shootings suggests another way of looking at America that may illuminate the gap between the rhetoric of gun ownership and civil society. The very density with which mass shootings appear on the timeline, blending with one another, reflects the deep difficulties of processing their occurrence, but also the manner in which mass shootings have come to represent the nation to an uncomfortable degree. Despite the specificity and unique nature of each occurence, the public violence of mass shootings demands to be mapped in relation not only to guns, but a rejection of civil society.

In its totality, the timeline raises questions about the aggregation of such deeply terrifying tragic events and the limits of comprehension save as an irregular quickening of public violence. While they surely offer a picture of the nation whose exceptionalism is evident in its rights to own guns and growing frequency of mass shootings–and they just don’t happened elsewhere–the script of such deeply tragic mass shootings recently has become recognizable event. The translation of the compilation of data, which first appeared at Stanford University’s Geospatial Center as an interactive map of Mass Shootings in America, has been translated into a range of new visualizations to grasp the increased frequency of their daily occurrence, if not, rather terrifyingly, a way in itself of experiencing time.

USA Today/Gannett–Mass Shootings in America until Dec 24, 2015

USA Today/Gannett–Mass Shootings in America until Dec 24, 2015