As we face an age when the norms of legal conduct in the United States stand to be shredded, we have been suggested to benefit from looking, both for perspective and solace, if only for relief, to fantasy literature as we await what is promised to be a return to normalcy at some future date. If Trump’s unforeseen (if perhaps utterly expectable) victory has brought a sudden boom in sales of dystopian fiction, as new generations turn en masse to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale or Aldous Huxley and Arthur Koestler for guidance in dark times. The search for points of orientation on a disorienting present is of course nothing new: much as maps of rising rates of mortality from COVID-19 brought a surge in popularity of Albert Camus’ The Plague (1947), an incredible sales spike of over 1000%, alternative worlds gained new purchase in the present. But we look to maps for guidances and the stories of time travel and alternative worlds were suddenly on the front burner. For the surprise election of Donald J. Trump that may have been no surprise at all prompted a cartographic introspection of questionable value, poring over data visualizations of voting blocks and states to determine how victory of the electoral college permitted the trumping of the popular vote; hoping to find the alternative future where this would not happen, the victory of Trump in 2024 provoked a look into the possible role of time travel in a chance to create alternative results about the stories that the nation told itself of legitimacy, legal rights, and national threats.

We had turned to fiction to understand new worlds during the pandemic. The allegory of a war mirrored the global war against the virus–and provided needed perspective to orient oneself before charts of rising deaths, infections, and co-morbidities in the press. Camus became a comfort to curl up with in dark times, to help us confront and imagine the unimaginable as Camus’ text gained newfound existential comfort. A friend insisted on ministering stronger medicine by an audiobook narration of “Remarkable occurrences, as well Publick as Private” in Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (1665), mirroring our own helplessness in spite of modern science, putting the seemingly unprecedented topography of disease in another perspective. London, that global capital which seemed mistaken for the world to many, was transformed as it lost a good share of its population–an unprecedented 68,596 recorded deaths is an underestimate–as the spread of bubonic plague spread brought by rats created the greatest loss of life since the Black Death, permeating urban landscapes with what must have been omnipresent burials, funeral processions, grave-digging, and failed attempts to hill or quarantine the infected–as if it were a land apart, sanctified and ceremonialized to confront death in suitable ways. But t he public trust that had been seemingly shattered by the pandemic–trust in health authorities government oversight, and expertise, led us to turn to past realities as some mode of exit from the grim present.

Mapping Mortality in the 1665-6 Plague/National Archives

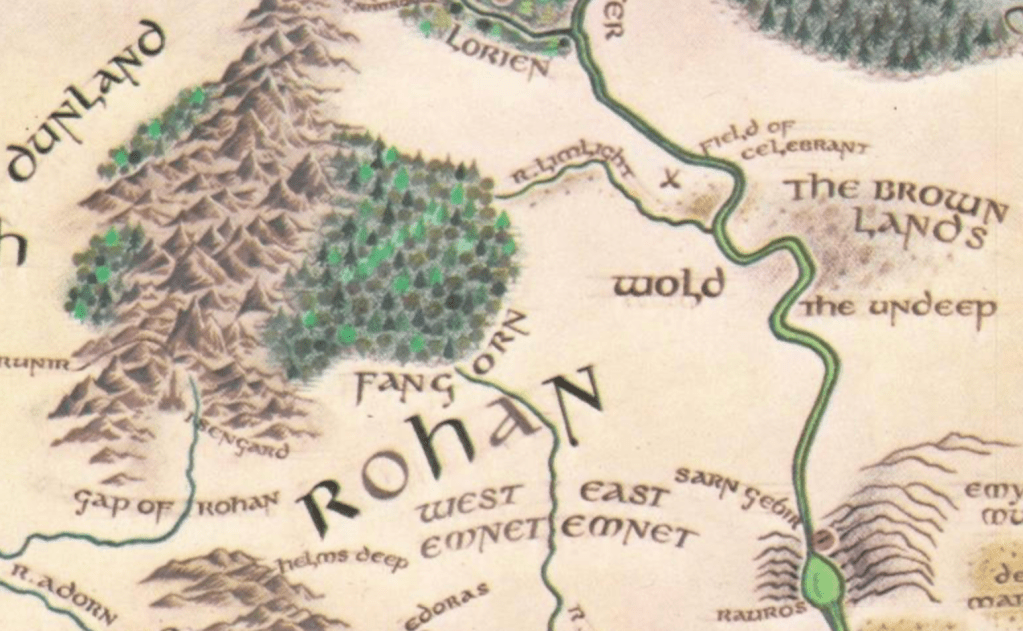

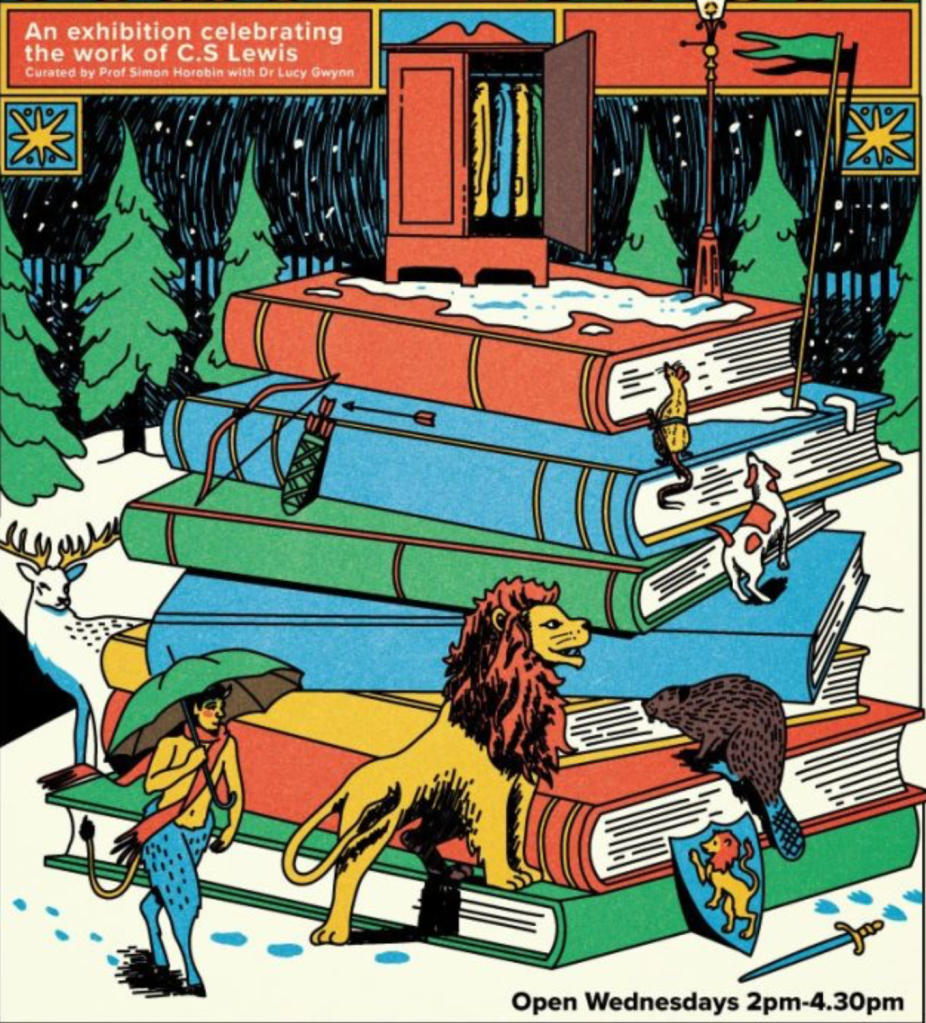

As we seek reading with new urgency as alternative means of intellectual engagement, the fantasy literature that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in Oxford, as members of the Inklings, a society meeting regularly in a pub, if not Merton College, sought to create such durable architectures of alternative life to explore. If both writers’ works have been studied as a rejection of modernist poetics, rehabilitating old genres and rooted in premodern poetic visions, the centrality of the maps accompanying each have perhaps been less interrogated as a source for their deeply enduring immersive qualities–and indeed for the durability of the alternative maps to the imaginary that both offered. In recent weeks, a wide array of fantasy books reaching bookstores beside apocalyptic fiction in ways that seem made to order, offering refuges from the present as forms of needed self-care; immersive fantasy books and apocalyptic fiction may be the most frequented sections of surviving bookstores that survive, sought out for self-help in an era of few psychic cures. And it is no coincidence that we also turn to the carefully constructed cartographies of these alternative worlds with newfound interest, immersing ourselves–not for reasons far from those their authors intended–in the mythic cartographies that might be familiar as sources of comfort, that it might make sense to examine the context in which the carefully wrought and designed cartographies of Middle Earth that were conceived by J..R.R. Tolkien and imagined world of Narnia were designed, as an alternative to the new cartographies of wartime that imposed a geospatial grid, in place of a world of known paths and well-trod roads of an earlier world. For the shift in the world that World War II created spurred Tolkien and Lewis to craft alternative worlds of resistance, in hopes for a future that might be made better, not only in a Manichaean struggle between good and evil they watched from Oxford, but to struggle with the future effects of mapping systems that seemed to drain or empty the concept of the enchanted world of the past–the literary “Faery” they loved–and replace it with a Brave New World of a uniformly mapped terrestrial coordinates that risked othering the wonder of the living world. But we anticipate.

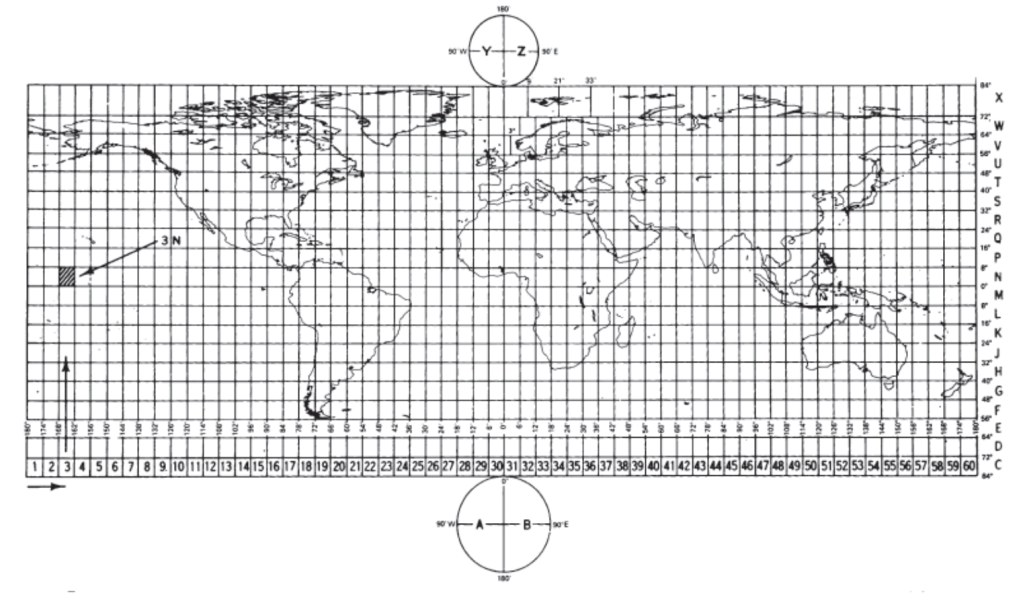

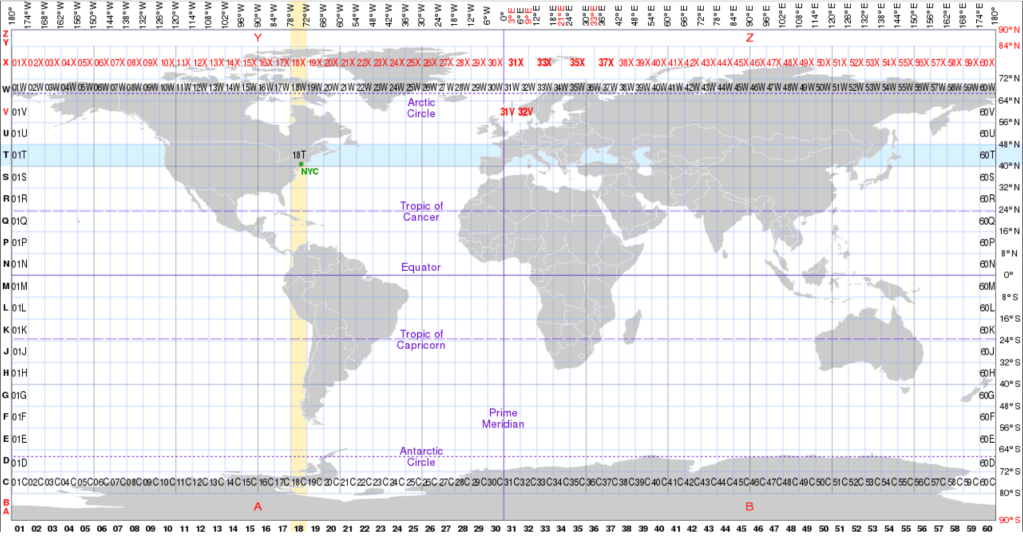

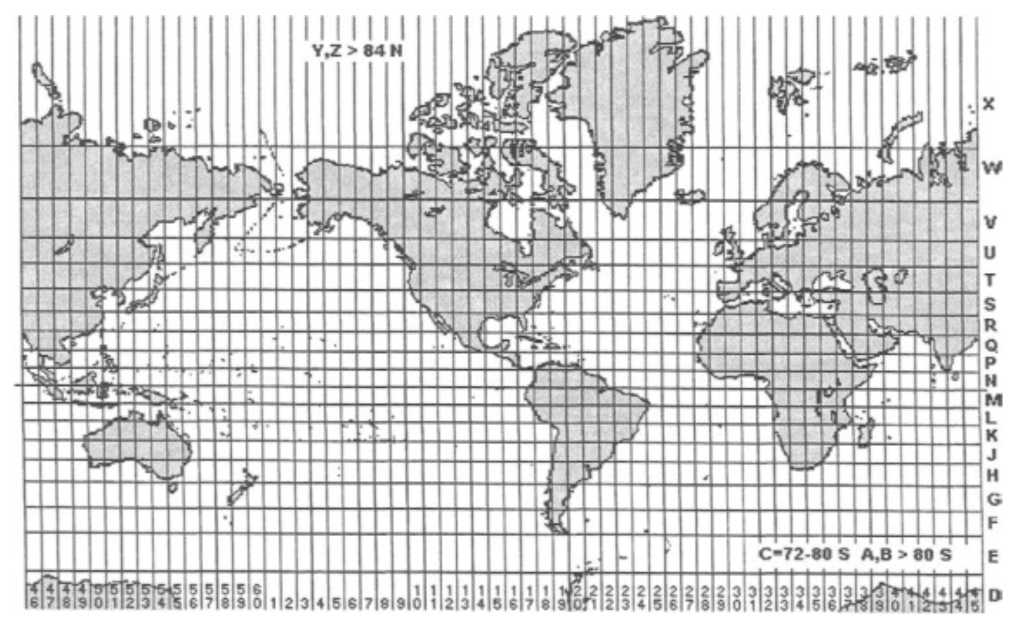

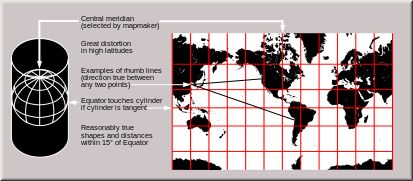

In short, we all seem to agree, the newspaper of record found a bit of a silver lining the day before Election Day, fearing the election’s outcome, offering the consolatory message of reassurance there are “few pleasures as delicious” as the ability to transport us “far from our present realm.” Yet the role of illustration in mapping of alternate worlds has perhaps been insufficiently appreciated. And while Narnia and Middle Earth are both seen as a predominantly mythic construction of worlds, removed from the orientation to actual locations, or to the power of transportation to a purely mythic realm, the pragmatic mapping of mythical spaces were alternative universes, modeled on mapping an expansive reality on the national borders of an actually remapped world that privileged the actuality of place, continuity, and contiguity in a mapping of location and position of precision without any precedent in geodetic mapping systems of the Universal Transverse Mercator maps advocated by the British and American military, and increasingly relied upon by the German military in the Battle of Britain.

The meeting of these two eminent architects of the fantasy worlds of the twentieth century–C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien–whose colorful literary works opened new portals for generations have been linked with richly detailed cartographic corpora of persuasive power to redefine fantasy fciton–are tempting to be seen as the consequence of some passionate creative synergy of defining paradigmatic models of escape. At the same time as two veterans of the Great War joined forces in hopes for curricular reform after the war in Oxford University by expanding the medieval readings undergraduates might be assigned, in hopes to expand a consciousness of myths and legends in the texts suited for postwar life, the skills of remapping mythic landscapes in response to the Great War depended on a deep bonds to a cartographer appreciative of the losses and absences of geodetic maps, and eager to help them draft the shores and contours of the “escapist” worlds of fiction that both Oxford tutor would start to draft that set new standards for children’s books and fantasy literature for the twentieth century, that demand exploration as an energetic writing of a counter-map to the new authority of geodetic grids of a uniform space, that focussed attention on the suspending of beliefs by the liminal spaces of the shore, the mountain ranges, and the living landscapes that the smooth continuity of the geodetic grid could not describe or reliably capture. As much as the two dons indulged in the creative power and shared love of William Morris, adventures of Lord Dunsany, and Norse legends, both deeply relied on the illustrations realized with the need for the actual cartographic skill of their common illustrator. For their versions of the literature of quest, Pauline Baynes effectively served as a needed midwife blending cartography and art by to render the palpable landscapes of shores still in need of defense.

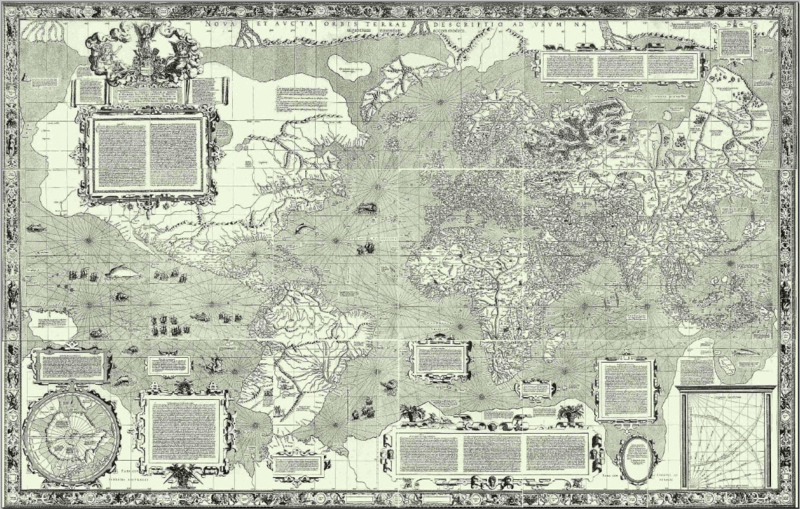

Both men acutely realized the need for a good illustrator for their projects of fantasy fiction, able to engage younger audiences that they had little practice in addressing, but whose interest they sought to attract. The prominent work on detailed maps for both books not only reached toward a demand to invest new mythic landscapes with concrete presence for their readers, but to create a new map of the world: to restore an older map of the countryside, to be sure, and forests that were still enchanted with meaning for their readers, but to map the countryside in new ways, rooted not in dots and points but in the continuity of the land. If Karen Wynn Fonstad, a recently departed cartographer of Tolkien’s Middle Earth, confessed missing a sense of proximity to Tolkien’s “tremendously vivid descriptions” in reading after a few weeks, the landscape of the terrain of Middle Earth persuasively offered a counter-world for many, lodged deep within our minds, as well as an escape from wartime when Tolkien composed their initial versions. The transportation powers of the text is real, and its exacting coherence demands a more adequate map than the new military maps of the global space defined during the Second World War, offering a basis to restore the lost sense of wonder that a point-based map elided, in order to provide the detailed landscape of a new form of meaningful quest, and to cast the novels as an opening up of new worlds in a world that seemed, inevitably, to be increasingly comprehensively mapped. These maps offered new spaces of exploration and proving that were outside the increasingly authoritative printed map.

The one-way ticket fiction offers may be deeply under-rated, but the map is critical to immersion in another reality. The Grey Lady of the New York Times indeed ominously but perhaps aptly marked the recent Presidential election’s results by offering orientation in this abundant field, providing signposts to a smattering of new fantasy books, as a response to the national exhaustion or real premonitions of fear. We rightly feel we are without precedent unwarrantedly–we’re confronting a loss of agency that seems unprecedented before the cocktail of environmental dangers of climate change, global heating, and an unprecedented circumscription of individual human rights, reading promotes a sense of agency, as does exploring landscapes outside of the present. If we feel alienated from the country that has again elected Donald Trump as President, to turn from blue and red states to maps of possible worlds form the past–we will need maps, as well as written narratives.

These worlds are however rooted in maps–maps of testing, maps of exploration, maps of selfhood, and maps of futures that are deeply lodged in our imaginations. They are not properly “possible worlds” but instead alternative ones, rendered by maps as regions that can be navigated along new orientational guides, attending to what is overlooked in other maps–maps of the nation, or of the world–by restoring or revealing overlooked orientational signs. If many emerged maps of new scales, dimensions, and resolution emerged in opposition to cartographic practices, the ways that Oxford–site of the Oxford movement, but a time capsule of religious devotion and royalist retreat from the present–became a site where the world was remapped in the interwar years, at the same time as the streets and urban fabric defining Oxford were facing new pressures, a layout bolstered by the archives of unbuilt architecture of urban planners’ dreams, and by the multiple patrons of college architects, among whom nurtured a neo-medieval architecture on fifteenth-century foundations of hammer beams, baroque screens, vaults, spans, and fans in a time-spanning style embodied by the perpendicular gothic in which were set carved gargoyles, plasterwork ceilings, and spires. The Palladian facades fantasias and architectural follies of Christopher Wren or Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) define a place apart, at an angle to the world, of expansive gardens, pathways among ruins of earlier times.

The poetic vision of a light able to pierce Mordor’s darkness and inspire a valiant quest for freedom was born in the neomedieval poem of distinctly Morrissian poetics conjured a counter world in wartime, as German troops invaded France, of a mariner whose course above the earth’s surface sought to preserve the last surviving shards of Edenic light. The complex backstory that he ably mapped for the poem bore the imprint of the earlier war, but crafted to an epic scale. If they recuperate old paths, fed by an Oxonian taste for re-imagining legends on anti-modern maps, drawn by illustrations and a stock of neo-romantic classicism, it was bolstered by an expansive philological apparatus Tolkien modestly called a consequence of being the “meticulous sort of bloke” not given to fantasy. Its maps opened powerful alternatives to the bloodshed and terror of the actual wars of the twentieth century as much as an Oxonian architectural fantasy.

The worlds of C.S. Lewis, Tolkien and others blur the imagined architecture of Oxford and romantic poetics of Morris served as “stock” to imagine an angle on the world, as a terrain that might be explored, and where a quest might still exist. Tolkien was hardly a utopian–and had little interest in “how worlds ought to be—as I don’t believe there is any one recipe at any one time” he described the invention of alternative worlds as that of a “sub-creator”–as much as seeing the author as a creators working with a large scale plan into which his readers were increasingly drawn. The appeal of these maps as invitations to alternative worlds has long been compared to the earlier traditions of cartography–cartographic conventions that formed part of the “stock” on which Tolkien claimed to have drawn in his work. Yet Tolkien’s skill as of illustration has proved to be quite a counterpoint to data visualizations, and indeed to the claims of comprehensive coverage of the world from satellite maps, or global projections, by offering the local detail of a conflict between good an evil that they lack.

In contrast to cartograms that have distanced viewers from the nation, or which suggest a nation grown increasingly remote in purely partisan terms, they allow us to inhabit those worlds in a refreshingly distanced manner, providing immersive senses of reality, as well as a needed perspective on the present. In the same years, Camus himself worried about the lacking landscape of moral imagination in the notebooks of 1938 that were the basis for The Plague,–feeling France could hardly contain Nazi Germany with honor, if it was not seen as a plague: in looking at geographic maps of frontiers, France was “lacking in imagination . . . [in its using maps of territory that ] don’t think on the right scale for plagues.” Thinking on the right scale reminds us of the current need for better maps of the imagination: we need counter-cartographies to the present as much as written works, of commensurate scale, involvement, and attention, as well as preserving a map of future possible worlds,–maps of superior orientation, fine grain, and moral weight to the current world. As much as rejecting the poverty they perceived in modern poetics, each constituted new maps of a world in need of adequate mapping tools.

Their “green worlds” are not pure fantasy; fantasy is a pharmakon for readers. The imaginative space of the written work opened up new absences of political space. In Camus’ prewar novel, Rieux, comes to fear the state’s role in spreading the plague coursing through in Algeria, Americans of diverging politics grew angry at the state policies for COVID-19 they blamed for the pandemic, lacking maps to describe where we were. While widely suspected that Donald Trump himself does not read books–Tony Schwarz doubted he felt inclined to read a book through as an adult not about himself in 2016, and Trump waffled about having a favorite book, citing a high school standard and explaining “I read passages, I read areas, I’ll read chapters—I don’t have the time” among his businesses–perhaps the act of reading is also one of resistance. This absence of any readiness to read may be a failure of the imagination, but also indicates an almost existential focus on the strategic role of deal-making in the present, managing a calculus of variables rather than people, accommodating to evils, and to sacrifice, more than empathy or the aspiration to human connection. The imagination of the moral theologian and philosopher C.S. Lewis to indulge in a children story, even without his own children, began from the domestic acceptance of actual children in his Oxford home from wartime London, it’s well known, when he penned the proposal for a new sort of story, not science fiction or serving more abstract theological morals, rooted in the adventures that he was able to imagine far more clearly of the displaced Londoners he housed–“four children whose names were Ann, Martin, Rose and Peter . . . [who] all had to go away from London suddenly because of air raids, and because father, who was in the army, had gone off to the war and mother was doing some kind of war work”–left to find new models of orientation to an enchanting Oxford countryside with little help from their host, “a very old professor who lived all by himself in the country,” who recedes to the background as a minor character as they are enchanted by their new surroundings. If Tolkien was a far more careful cartographer–far more perfectionist and academic in structuring another world–the alternative cartographies both constructed, this post argues, were midwifed by the illustrator both shared, who used her own cartographic skills to design their immersive worlds.

Creating viable worlds of otherness is an old art, but rapidly grew a far more complicated proposition in the years after World War II, a postwar period that was relentlessly dominated by new mapping tools. The demand for more expansive maps of the imagination paralleled the birth of Narnia and Middle Earth, expansive immersive worlds mapped in Oxford the respond to the claims of cartographic objectivity whose authority both authors whole-heartedly rejected in creating expansive atlases of purposefully anti-modernist form. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien imagined expansive green worlds in multi-volume fantasy books by Lewis or Tolkien as a new atlas paralleling the objectivity of the coordinate grids as the Universal Transverse Mercator, first widely adopted in the post-war period, as their works offered testing grounds for virtue removed from battle or transnational war: the green words of Middle Earth or Narnia may be tied to the success Henry David Thoreau’s bucolic Walden of a life apart won among World War I veterans, years after its publication in Oxford World Classics; but the expansive worlds one encounters in Narnia oriented readers not only to a new cosmography but an expansive atlas of fictional territory. Beyond anything William Morris had drawn or written, the influence of Morris on its writers–and on the woman who provided the romance of their different quests–acquired new scale, dimensions, coherence, and topographic density, orienting readers to landmarks that grew lodged in readers’ consciousnesses so that they seemed the transmission or recovery of previously unknown worlds.

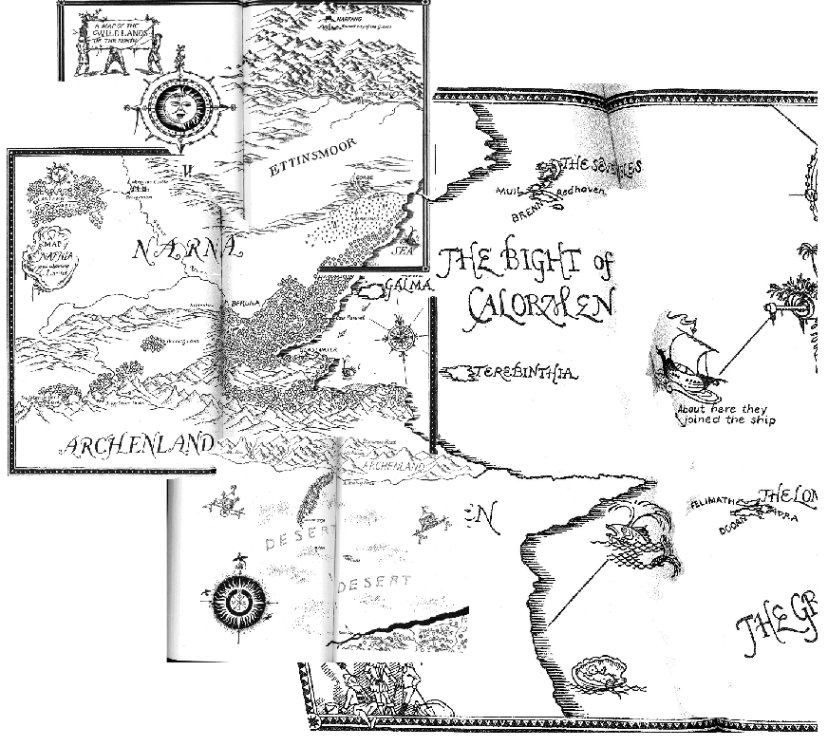

The maps of an archeological recovery of a Medieval landscape of good and evil became immersive counter-worlds because they existed at a distinct angle to the authority of current mapping tools. Indeed, the expanse of Narnia, poised between Archenland and Ettinsmoor, defined not by natural geomorphological borders of mountain ranges, marshes, and desert rather than by abstract lines, without lines of longitude and latitude, grooves a uniquely suited testing ground for honor, duty, and valor of a timeless and mythic nature, suited for testing bravery and aptitude for a preteen; it is an atlas that unfolds in the sequence of books–here assembled from several volumes–that maps a world that was lost with the rise of maps of geodetically determined borders mapped by a grid to coordinate military engagement, logistics, and the coordination of ground and air travel. Its maps are dominated, appropriately but the faces of a sun that peers out from the mariner’s compass rose–and by the natural worlds of forests we are in danger of overlooking, not as so many lost green worlds but as living landscapes.

Narnia Maps by Pauline Baynes, assembled from the Endpapers of Volumes in Chronicles of Narnia, 1950-1956

Despite our immediate needs to fill the absence of a vision of the future before current quandaries, it is helpful to recall the counter-cartographies have existed throughout the twentieth century. While unfortunately less rarely examined as maps, so much as texts, maps are needed to create new worlds. Those hyper-nationalist maps of MAGA are deeply disturbing with their insistence on firm borders, and may well compel spatialities of refuge–not only sanctuary cities, or safe spaces, but real safe spaces over the long term. In such a search, the mapping impulse is liberating in ensuring our imaginations. Some of the greatest fictional lands–preeminently, Narnia or Middle Earth, to take two contemporarily mapped worlds–if for children–were made to order for dark times of the Blitz as bombing raids on English cities intensified beyond strikes on port towns, targeting of populated areas of the country’s main industrial centers, and providing a grim setting for which both authors offered a new topography from Oxford, challenged by the grim memories of World War I but seeking a new spatialities to orient oneself, not only by a distracting quest for nobility or valor, but a counterspace that existed as the spatialities of the Universal Transverse Mercator gained a hegemony in one mind, and indeed offered new geometric coordinates to understand space, not as lived but as tactical, coordinating earth, air and sky in a new sensibility that privileged pin-point accuracy and offered hope to avoid the strike of missiles as the V1 or V2.

Some, as Orwell, insisted on staying in urban settings to acquit themselves with valor, navigating a city with areas “roped off because of unexploded bombs” with a sense of adventure and meeting challenges to “write in this infernal rackets” as failed electricity forced him to write by candle-light –as if even if he was not able to fight in the army, remaining in bombarded London was a means of suffering with urban inhabitants targeted by bombs as a war zone whose apartment buildings might soon be transpired into “good machine-gun nests” of combat. If the experience provided him with a geography of fear that informed 1984, others needed spaces more comforting, with forests, mountains, streams, waterfalls, natural sites and calm oceans to steady their fears. (Orwell enjoyed visiting the estimated 200,000 seekingshelter form bombs in the Underground, visiting “tube shelterers” and open air meetings to agitate for war in Trafalgar Square, as he hoped to join the Home Guard and worked in broadcasting, taking pride in typing in rooms as V2s fell on London in the distance that would provide the basis for rockets falling on Oceania in Nineteen eighty-four.)

The maps of Narnia and Middle Earth remain amazingly compelling and entrancing as alternate landscapes that are imprinted in our minds, long lodged as alternate mental imaginaries we oriented ourselves to which we might always retreat. They offered important places of retreat when created. Tolkien’s characters are rather two-dimensional, but live in a vivid map of dangers and purposeful nature of the quest as an immersive relationship to space–and danger–that ends with an affirming spin. The maps that these books offer, as much as their characters, the characters and storylines are inseparable form the detail with which they map other spaces, even if more rooted in fantasy than possible, preserving alternative spatialities in a time of need, which we are able to explore with a sense of discovery before grim realities–as if to nourish them–and which gained a newfound popularity in the 1960s as such, during the neocolonial Vietnam War, long before they became cinematic worlds.

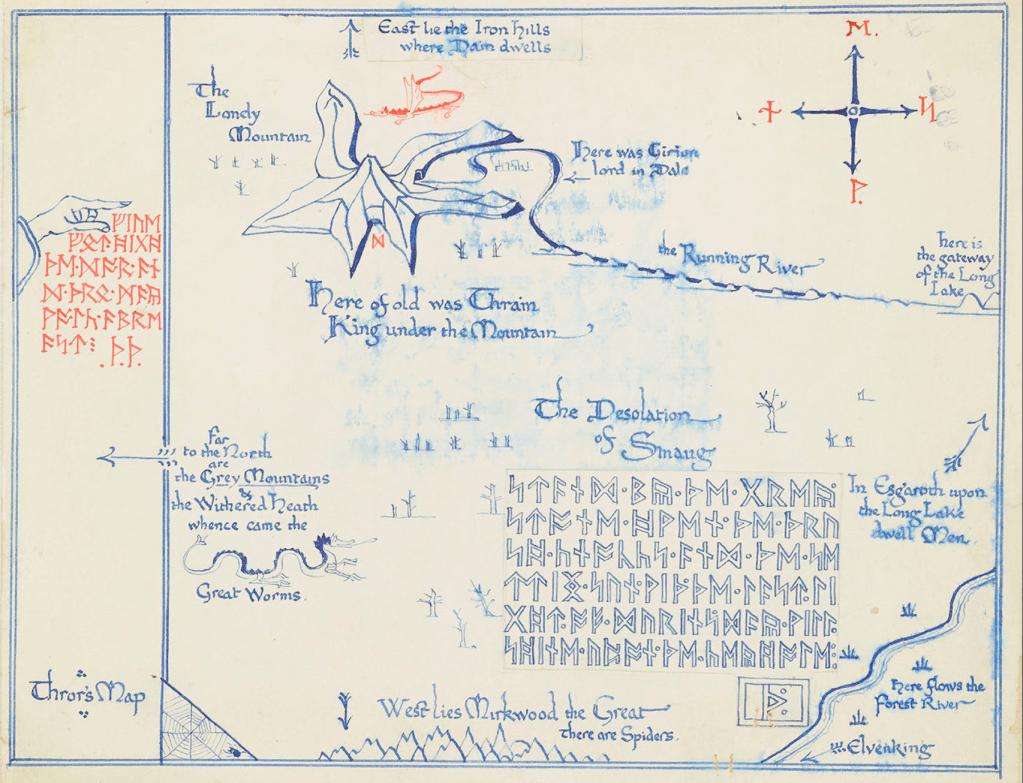

Many have continued to look longingly at their maps as alternate worlds. This blogpost may be overly demanding–it pushed new ground, and was written as I lived in Oxford–it seeks to situate the creation of such engaging alternative worlds not only as responses to war. For the illustrator who both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis engaged offered new tools of mapping for navigating spaces as if she were the midwife for the spatialities both Oxford authors devised. I hoped to place the vivid worlds as compelling counter-cartographies many twentieth-century readers have continued to return, and indeed to travel in and inhabit, at a remove from entanglement in political spaces–and from the abstract tools of mapping that emerged as authoritative in wartime, and indeed the geodetic grids that gained authority in the National Grid during the late 1930s, before World War II. The maps designed of Middle Earth and Narnia, plotted not only by the authors of both books penned largely in Oxford, but illustrated in such compellingly immersive manner with exact topographic detail by Pauline Baynes,–herself a skilled illustrator trained in Bath’s Hydrographic Office in wartime, with special ability to render shorelines and terrain. For Baynes mapped an augmented Middle Earth, beyond the wilderness maps Tolkien drafted for The Hobbit (1937) in which readers plot Bilbo Baggins’ quest to Smaug’s lair, that made her far more than an illustrator, even if C.S. Lewis wanted only an illustrator to address young readers: the far greater scale and expansive terrain served as setting to define individual prowess, daring, and dedication that Tolkien viewed as lacking in the modern world–and in danger of lacking outside military combat.

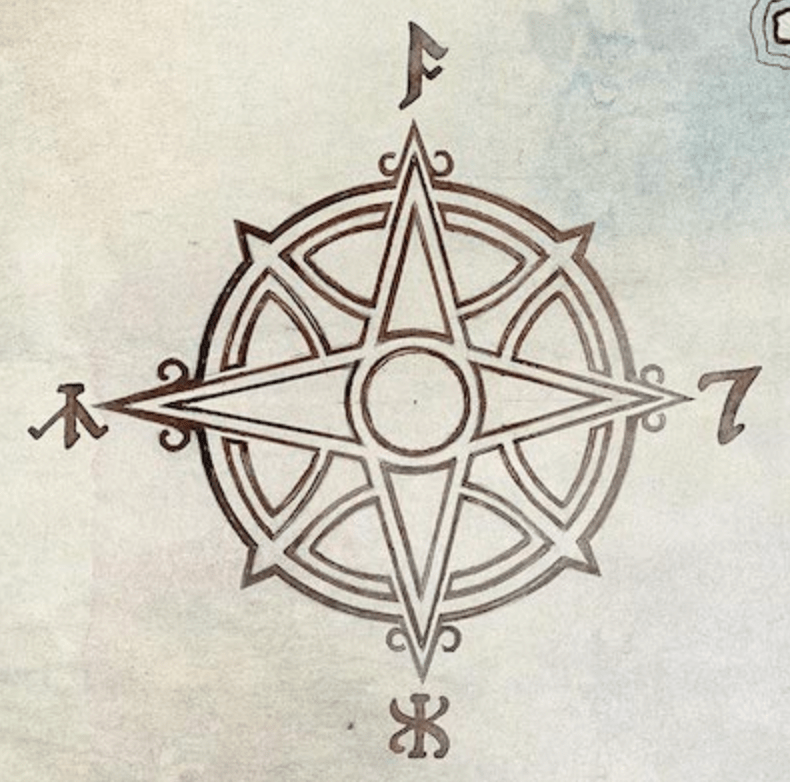

Her maps expand the ecumene, and a cosmos far greater than previously thought. The compass rose that orients readers to the questing voyages of the hobbits on such an expansive scale, far greater than in the narrative of The Hobbit, not a sign of moral security to navigate the expansive literature of the quest? Famously, British-American poet W.H. Auden quite extravagantly praised The Hobbit “one of the best children’s story of this century.” He relished its reading before leaving England on September1, 1939, embracing his faith but “uncertain and afraid/As . . . Waves of anger and fear circulate over the bright and darkened lands of earth.” Committed to the quest as an old genre that retained redemptive value, Auden openly praised the scope and scale of The Fellowship of the Ring as a part of the “genre to which it belongs, the Heroic Quest,”–even if it was “the imaginary history of the imaginary world,” non “a subjective experience of existence as historical.”

The imaginary history was more real, in many ways, than the historic, and demands to be compared to it or at least drawn in closer dialogue to one another. We may rightly cringe at Amazon Prime’s appropriation of a corrupt version of the Tengwar compass rose of Eärendil the Mariner and of Gondor’s riddle that “not all who wander ar lost” as a crass manipulation for purely commercial reasons–promising to offer secure guidance to web-crawlers whose online shopping induced their brain fog!–as the search engine pretended it had only its customers’ best interests in mind–

Amazon Prime Video logo, 2019

–even if it occasioned little sense of the valor or bravery that Tolkien had taken the version of the medieval compass rose to demand. But the logo that was featured on Facebook and Twitter seems to persuade customers feeling disorientation online that they hadn’t in any ways stopped training their senses to danger shopping or were at danger of placing their soul in mortal jeopardy.

The abundance of merchandise Amazon offered featured faux pen-and-ink panorama of Middle Earth, overlayed with calligraphic toponyms in neo-medieval script heralded streaming the 2012 film of Bilbo’s quest with thirteen dwarves to reclaim the Kingdom of Erebor,–or the 2014 sequel of saving the Lonely Mountain from the Prince of Darkness; it was featured on Twitter and Facebook only to energize new generations of subscribers. And it also reassured its customers that Amazon offered the guidance for consumers worthy of the riddle of the King of Gondor, a riddle shamelessly paired with incorrectly transcribed ordinal directions in Tengwar, as if it was worthy to adopt the icon of vigilance in a world without clear guidance, lest the peril of an absence of direction lead to evil’s victory. To return to Baynes, however, it is no surprise that although maps did not appear in the full set of Narnia Chronicles until its third published book of the sprawling seven-part sequence, Baynes and offered us the ability as readers to navigate the new and fearful landscape of Narnia in Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe–a book which established a need to triangulate space out of the day to day life of wartime–in ways that overlapped in curious ways with an actual wartime landscape, perilous in its pathways, unprecedented, and terrifying, as we navigated its massive snowdrifts with a fawn beneath an umbrella in ways that offered a huge assist in accompanying Lewis’ able prose–

Pauline Baynes, Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

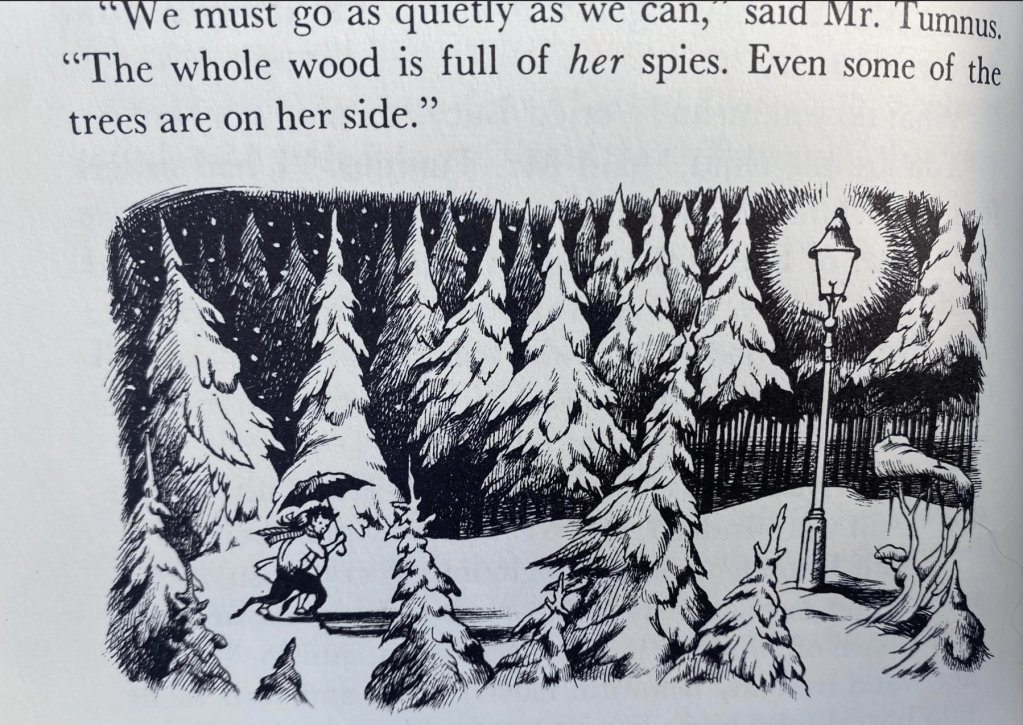

–whose pairings of text with image offered a new landscape for readers’ eyes and minds. Entering the woods of Narnia we must walk “as quietly as we can,” Lucy was alerted by the faun Mr. Tumnus, the first of its all so civil inhabitants she encounters, as the “whole wood is full of her spies–even some of the trees!,” that overlap with the fearful uncertainties of wartime, its home front filled with actual enemy spies–maybe even hidden in trees. The line drawings of Pauline Baynes invite the readers into this new world, by new points of orientation, as if they wanted to defer the inclusion of a transcendent view of the region before it was explored in several volumes–and indeed the only map that was provided in the third volume was when the course of the Dawn Treader entered the Narnian Seas, demanding a neomedieval map of its shores and the situation of the children’s travel.

Are we not exploring and surveying this landscape as readers, with the help of Baynes’ detailed drawings of its tall trees and snowy fields, finding only the beacon of the lamppost to lead us through its dark pathways, and then only fortunate to find a guid to its woods? We navigate its landscape keen to orient ourselves in this world, in Baynes’ first line-drawn illustrations, surveyed a world of forests and rivers and shores she later so decisively set in compelling cartographic form. We are guided by those first footsteps in the snow a local informant immediately after gaining his trust to move along its pathways, in another world than familiar to Daughters of Eve–

Pauline Baynes illustration, Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

–as Mr. Tumnus guides her in the Narnian snow at an entrance point to another world she entered trough the portal of the eponymous wardrobe.

We gain. orientation only by illustrations as readers, one of a Manichaeans struggle of good and evil, that might mirror World War II or the hellish warfront of World War I Tolkien experienced at first hand, that broke with the “world of grown-ups.” Led by a growing cast of native informants to understand the stakes of their struggles, we gaini a clear sense of the scale of its landscape over time, and the hills and castles they must survey to learn the lay of its otherworldly green land. Baynes’ drawings assisted in the necessary task of navigation–and not only the deep shadows cast by its evil Witch–in the sense of an unknown world which it is time for us to navigate and learn to inhabit as we read Lewis’ prose, rather than “waste” time “with a crowd of strange grown-ups!”

Pauline Baynes illustration, Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe (1951)

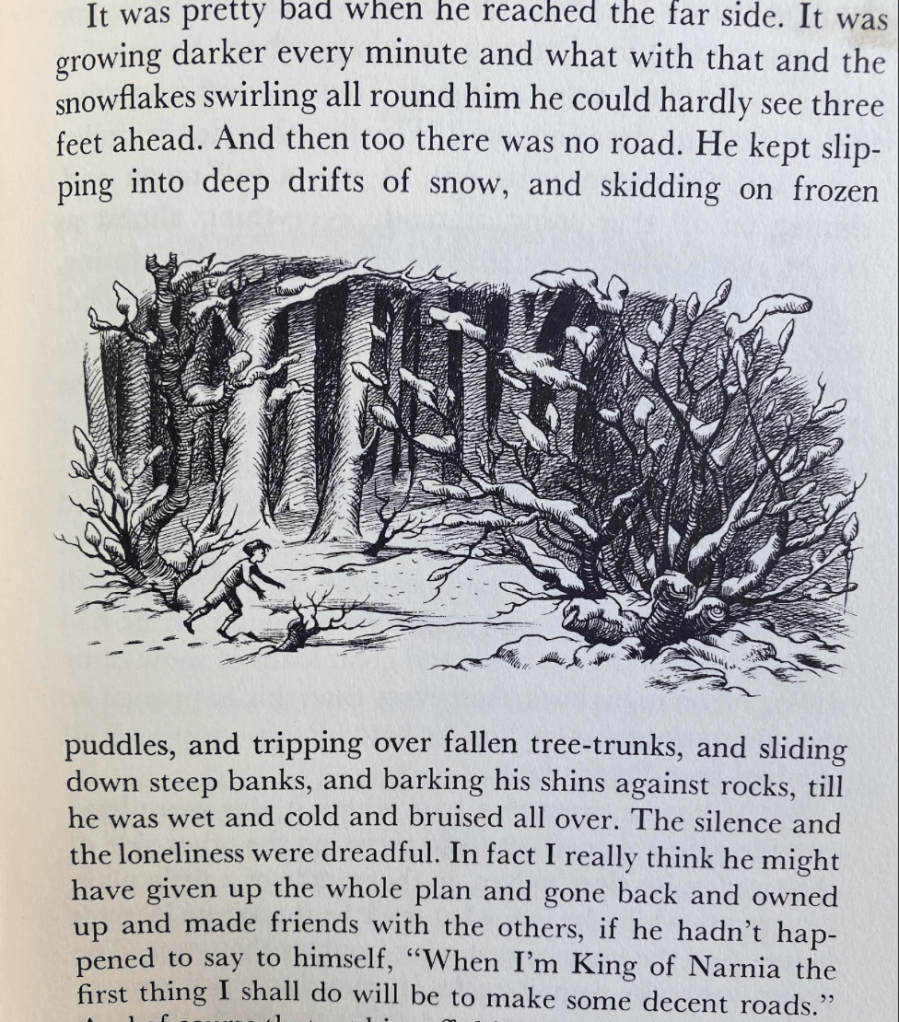

It is a landscape as treacherous as a bucolic, without good roads or modern infrastructure –if one understands that is a huge part of its enticing attraction. Baynes captures this lack of roads, amidst the falling snowflakes that mask what is ahead of oneself, as Edmund is left slipping into snowdrifts and skidding perilously on puddles–and imagines transforming, horrifically, to paved roads.

Pauline Baynes ilustration, Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

–and slipping into vainglorious thoughts, even as the landscape he trudges, reduced to a state of slavery to the Witch he is enthralled, suddenly starts to turn green, its drifts of snow clearing under an open and inviting blue sky where wonderful things might well improve, even for him, as he is being hurried along by a dwarf brandishing a whip, and a Witch who keeps yelling “Faster! Faster!”

Pauline Baynes illustration, Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

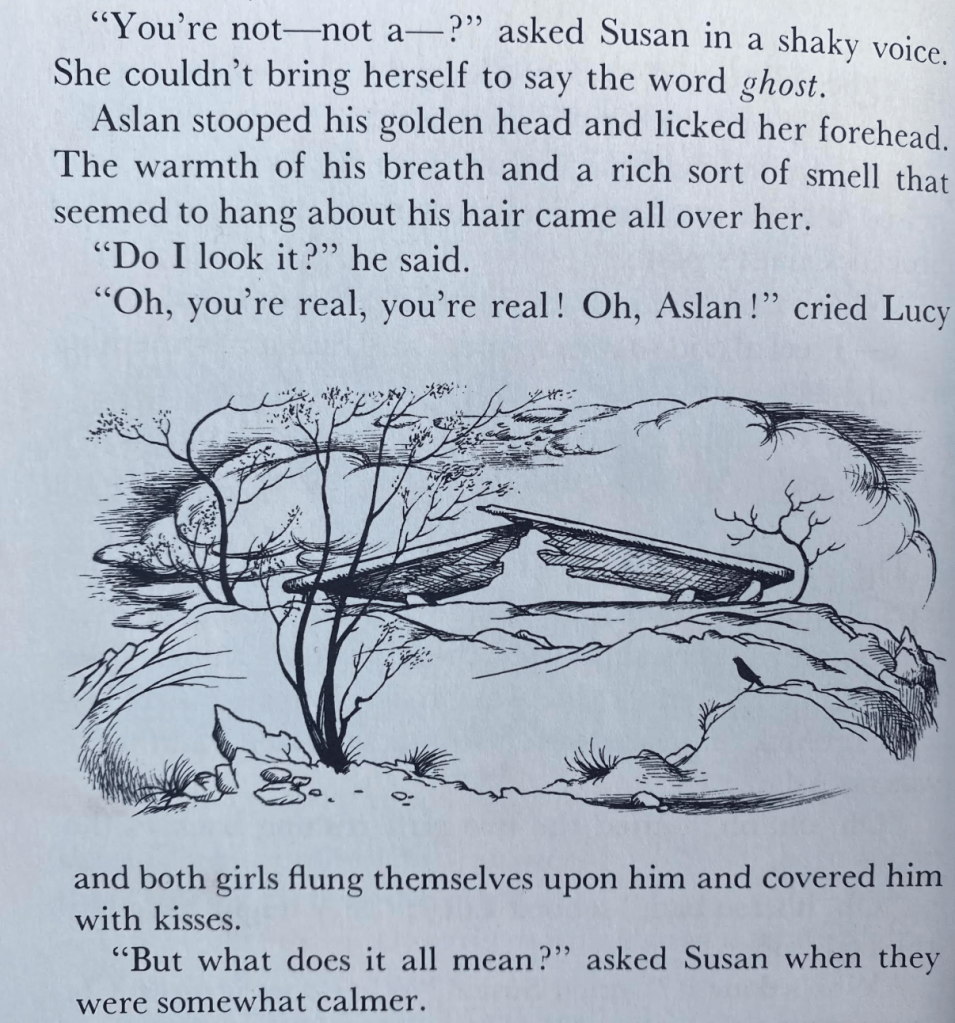

The culmination of the discovery of the Stone Table is also the site of remembering that this landscape is quite deeply real–not at all fantasy or illusion–as present to us as any, no matter what our instincts or rational tendencies might say. And the marker of the broken stone table, under the skies of Narnia, is likely to be lodged in our heads, no matter what it means to Lucy and Susan, as they are able to help restore Aslan to life, and allow this entire world to leave the Witch’s spell.

Pauline Baynes, Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe (1951)

If these were not true maps–and indeed the map of Narnia only appeared in the third volume, as its topography became overly complex, not arriving at a transcendent view of the forests and seas of Narnia were perhaps the point of the earlier volumes; they forced the reader to try to negotiate footpaths through the forests of this alternate world to explore it. The absence of a transcendent view was not a lacuna, but an admission and insistence that this world is navigated by footsteps–there was no need for the map, as we learned the right path to orient ourselves, even as we are so overwhelmed were by the abundantly illustrated worlds open before our eyes–realizing the limits of our knowledge of its moral order as we approach the coast of Narnia at the first novel’s end.

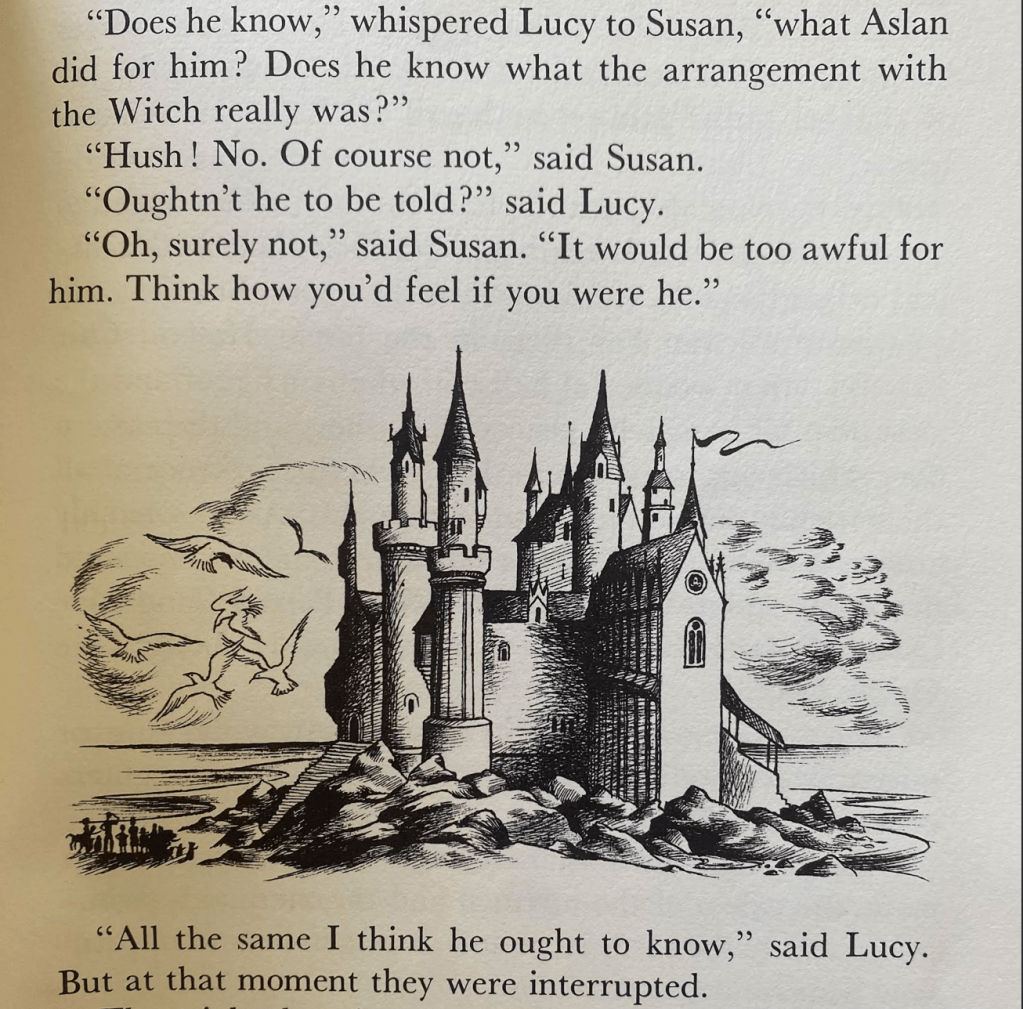

Pauline Baynes’ illustration of Cair Paravel on Narnia’s Shore, Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

The placement of these illustrations on the page with text offer the path that the children must learn to negotiate in Narnia: as much as denying readers a transcendent view, the footprints in the snowy forest reveal the radically older paths of virtue Lucy and her siblings learn to take in Narnia, after entering the land through the old wooden wardrobe’s walls, as a way to re-enchant a changed world. The extent of wartime shift in spatialities of mapping in an England besieged by arial bombs demanded the resurrection of older, earlier forms of mapping–a resurgence of older mapping forms that the works of Lewis and Tolkien offers and quite intentionally evoked through Baynes’ distinctive craft and abilities of line-illustration, creating a sense of quest in line-illustrations that served as a critical counterpart of mapping worlds that each attempted to render in written form.

Perhaps the extensive shift in orientation was best evoked by the German emigré novelist Thomas Mann, who charted the compromises of bargains with the devil in modernity in his wartime novel Dr Faustus. If the novel is about the fictional composer Adrian Leverkühn, it celebrated as god-given the arrival of a new range of precision targeting of England by bombs by the V-2 rockets guided by x and y axes in radio space as a “sacred necessity” that seemed to engineer a necessary turning point in the war of attrition. The bombing developed by the “prowess of German engineering” seems by a divine bargain–or a diabolic one–to render targets in the English cities and countryside vulnerable to precision bombing tools. If the arrival of the V2 heralded and a new space of victory, by literally opening the “appearance in the western theater of war” in maps by which the”new retaliatory weapon” might strike, even the “Führer frequently alluded in advance with genuine elation, . . . the robot bomb, such an admirable piece of ordnance that only sacred necessity can have inspired the genius who invented it.” That landscape, we might remember, was not only engineered, but imagined, and was met on the ground by a response from the imagination.

This bomb–a truly pure distillation of a Faustian bargain with fate–opened the war on Britain to the rocket strikes of the Blitz in which Tolkien and Lewis wrote, as “countless numbers of these unmanned, winged messengers of destruction were fired from the coast of France and fell exploding over southern England,” in a massive attack intended to forestall further German military losses and change the wartime map–and threatening to erase the most recognized and eternal monuments of sacred space of religious worship and public devotion. In response to the fears of how “the destruction of our cities from the air has long since turned Germany into an arena for war; and yet we find it inconceivable, impermissible, to think that Germany could ever. become such an arena in the true sense,” as “our sacred German soil . . . would be some grisly atrocity,”–the decision to bomb London and the southlands in the Blitz promised to deliver a geography of devastation, destabilizing in its landscape of precision strikes in Britain, engineered by rocket technologies and demoralizing the British to shift the warfront onto the enemys’ home ground.

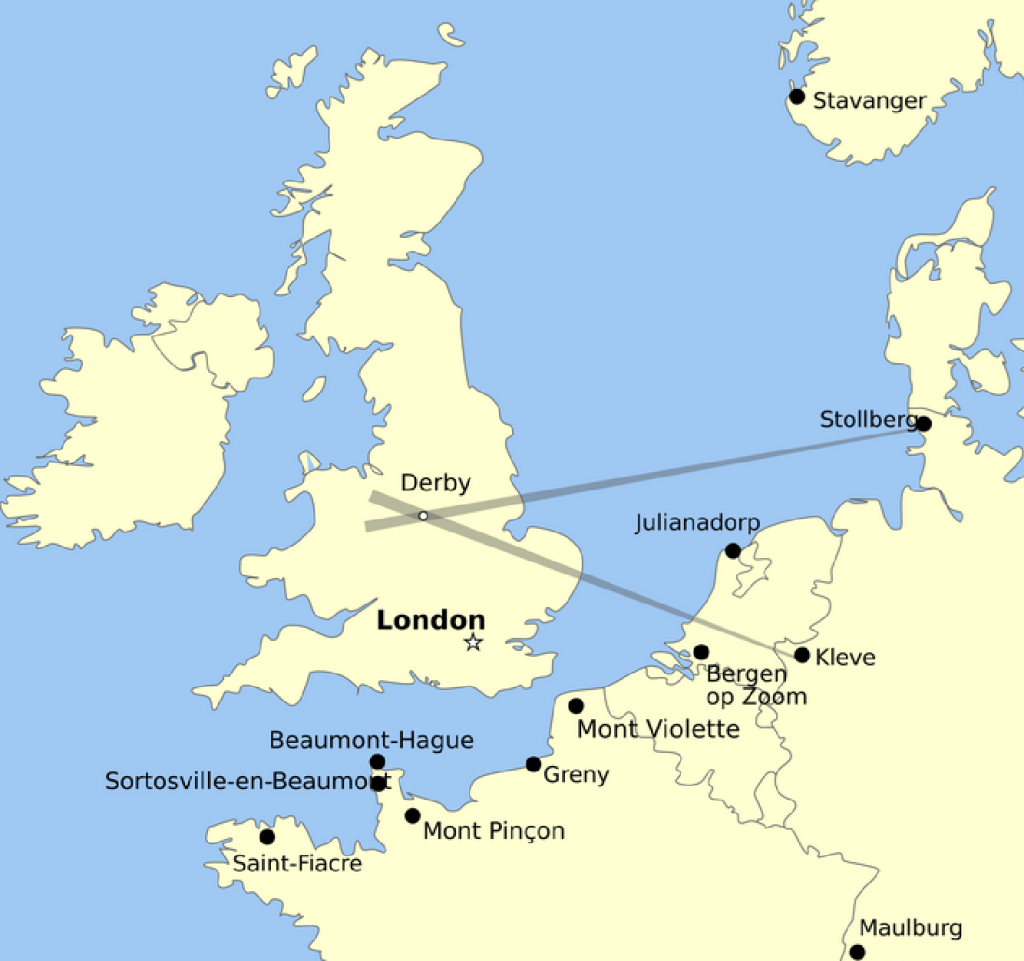

St. Pauls Destroyed in London During Blitz

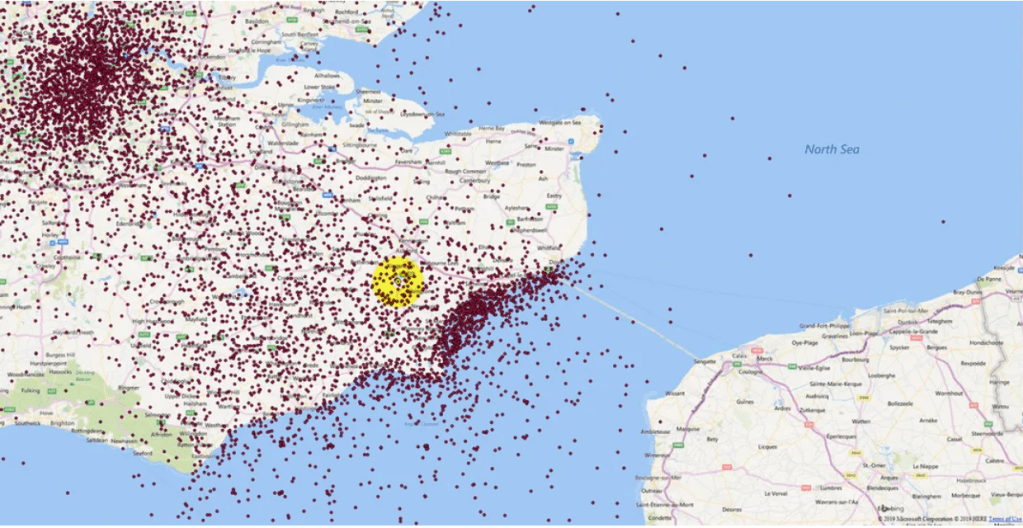

This marked the arrival of the deeply disturbing geography of destabilization and risk, a risk more pressing and more existential in roots than anything that had been encountered at sea, or in the more dangerous voyages of exploration or unknown lands. It was more terrifying as it was local and known, but about saying goodby the past in a seemingly definitive ways. The absence of guidance or recognized landmarks was responded to with the literature of the quest. Auden had hoped something quite similar, asking “What parting gift could give that friend protection,/So orientated his salvation needs/The Bad Lands and the sinister direction?” and pursuing the theme of impending isolation in his own offering of modernized Anglo-Saxon verse, The Age of Anxiety (1944-1947), and the need for moral orientation was especially important in a new era of mapping tools, in which maps of the national borders and military strategy were increasingly removed from first-hand apprehension of the lay of the land, as the arrival of V-1 and then V-2 bombs punctured any sense of the continuity of the landscape and increased the precocity of any spatial position as they crashed into the countryside, often before reaching London, spurring the German engineers to devise a more precise way of equipping rockets with fuel to guide to targets across the channel–a range of danger and uncertainly recently mapped by amateur archeologists from downed bombs.

V-1 Bombs that Crashed Before Reaching London in Kent County and London Bomb Strikes

This was a landscape where sacred and secular realigned in new ways, and the realignment was a common work of many in the English countryside, outside of Oxfordshire, as well as within. But it defined the horizon of expectations for the very audience for which both Tolkien and Lewis wrote. This was a setting risk where, to quote a mechanic who lived through it, “You just prayed that they wouldn’t cut out and they wouldn’t fall on you. It was a horrible feeling but you prayed, ‘Please let them go further and fall on somebody else…’ ” While we separate the domain of children’s literature from the actual world, Tolkien and Lewis both rewrote the quest for modernity, and offered what now seem echanted landcsapes to readers who might have no longer access to these old worlds, preserved and cultivated to an extent in the Oxonian towers in which both lived. But both were extensions of the Oxonian preserve to the entire world, a sort of rethinking of the good v. evil struggle of the actual world from the point of Oxford to the world, a counter-mapping of the global projections of world war. It was a map of virtue, if one delivered with far different levels of writing, and immersive detail, that seemed to ward off the geodetic spaces opened during global war and the advance of Nazi V-2 rockets in the air space of Werner von Braun. Serenus Zeitblom may have kept serenity in his writing of his friend the composer Adrian Leverkühn who had sold his soul to the Devil, watching Satan from close at hand, slightly intrigued, as the “unmanned, winged messengers of destruction were fired from the coast of France and fell exploding over southern England, and, if we are not totally deceived, will soon have proved to be a veritable calamity for our foes.” This was the landscape of war in which the veritable calamity seemed palpable, and all to in reach, and in need of symbolic as well as real refuge in other, older maps.

The differences in each writer’s style of landscape can be seen indeed in tactical terms as responses to the fears of a new landscape of wrenching dissonance and absent moral values, a new training ground of spatial orientation if the apparently palpable fears of the old one might lack in the near future. Tolkien’s quests are more closely aligned with the poet’s own love of the quest than Wystan Hugh acknolwedged, or fully expressed, even if he praised them as a new moral center that might be restored while one was under their spell, far removed form the world of radar. Auden’s wartime fears of receding individual self-understanding filled an “ordered world of planned pleasures and passport control;” in 1944, he bemoaned “of the wearily historic, the dingily geographic, the dully dreary sensible” as unavoidable in modern life free from “any miraculous suspension.” The victory of the sensible–the “dreary sensible”–is a sort of surrogate for modernity that is the essence of a remapping of space, on the outsides of consciousness but uniformly adopted as a less enchanted world threatened to impose itself circa 1940. The fear of an uprooting of worlds by the prospect of a “decisive military defeat” the overturned one’s intact sense of self and one’s relation to one’s world, “despite the universalist hue that Catholic tradition casts over [it]” suggest a fear of impending loss of vanishingMann’s surrogate narrator, Dr. Serenus Zeitblom, expressed to seek distance or refuge from the dangers of an impending loss of state.

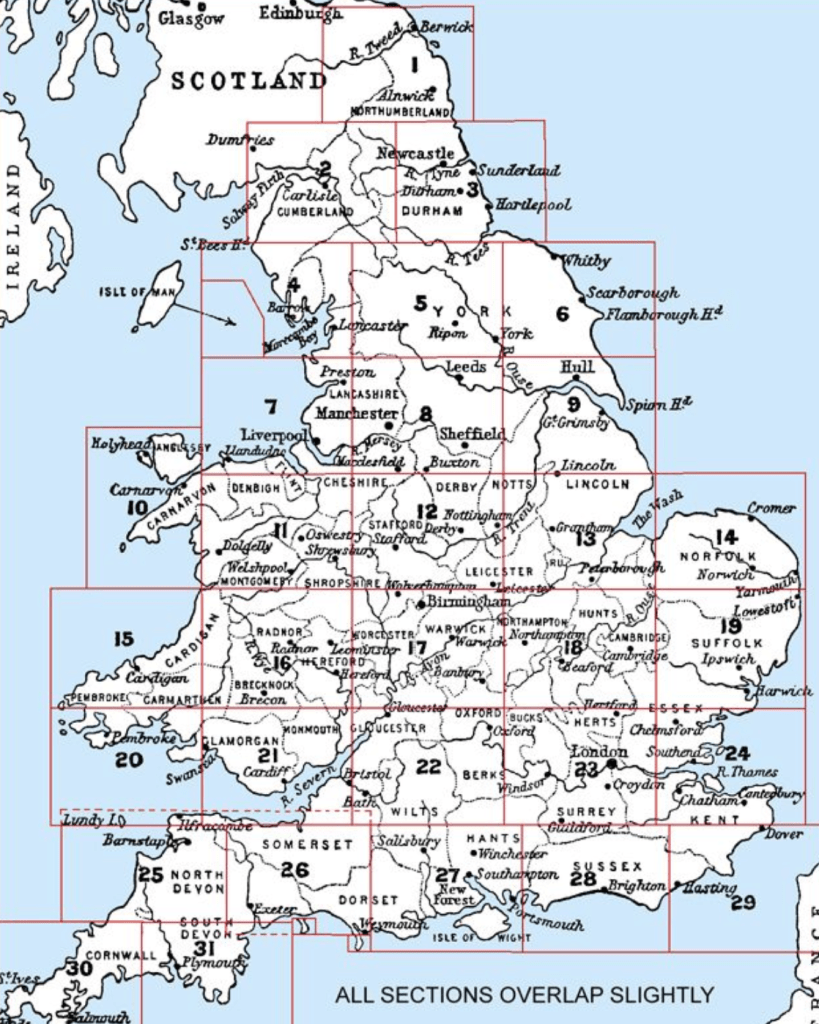

The figure of Zeitblom may be to some extent a humanist parody, but the sheltering worlds of Middle Earth and Narnia are a fantasy of a stateless world, born roughly at the same period in time as the United Nations, as a struggle to imagine a space other than a national space, outside of the bourgeois space of the nation that seemed destined to be replaced. In contrast to an increasingly atomized individual, or lonely crowd, Tolkien’s quest was reassuringly collective, without moral suspensions. Both authors, Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, had indeed forged durable maps of morality (and mortality!) before the increasing fragility in the rapidly remapped wartime world, landscapes that seemed to freeze with fear. For Tolkien and Lewis vividly imagined and powerfully delineated unknown wilds–forests and wilds, bogs and rivers, talking trees and dramatic coasts–whose presence were being erased by anthropogenic change, and excluded from maps. Their compelling cartographic escapism to realms lay at an uncanny angle to geodetic drafting of England’s first National Grid, OSGB36, a eference system of terrestrial coordinates and new datum that presented a gridded space without spiritual center, or preserve the landscape both experienced at first hand.

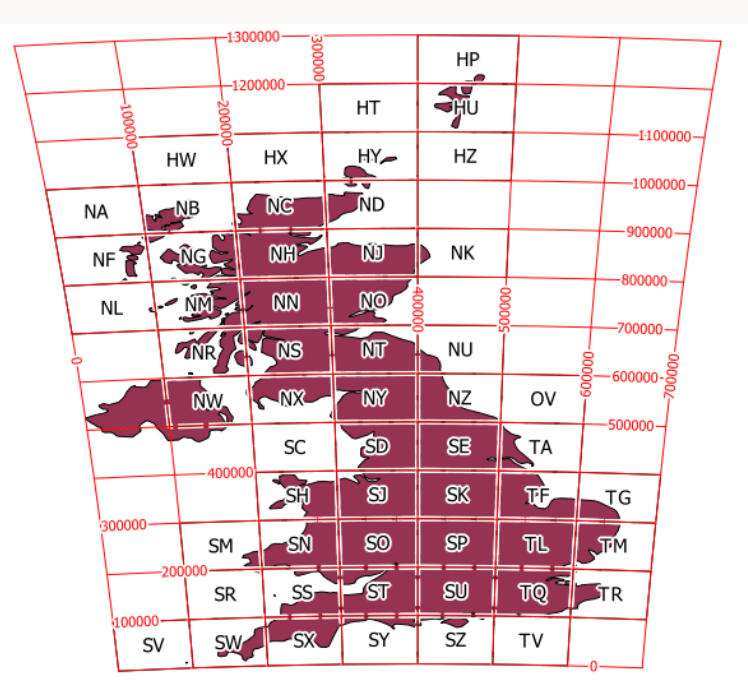

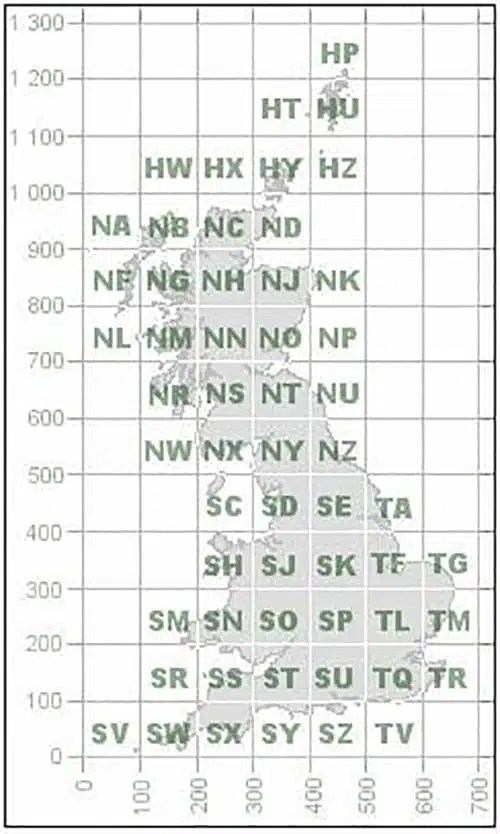

The smooth surfaces of these maps, for Catholics as C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien–or even Auden–beg questions of any moral centering, indeed, so fundamental to their fictions and fictional worlds. Despite the centering of England’s National Grid from 1936–a major remapping of the nation along coordinates of a disembodied grid. The National Grid is oriented on a zero meridian through center of England, parallel to the transverse Mercator grid, allowed a map of national space that mapped England, Northern Island, and Wales as a continuous surface of positive coordinates. But despite the allowances it afforded for the electrical engineering, surveying, and national infrastructure, the National Grid was also a zero-point for fictional cartographies of fantasy for each writer, whose fictions reflect steep concerns for the abstract nature of space it rendered. By flattening land and sea and erasing all landmark, and establishing an arbitrary origin point for a zero meridian of a smooth undifferentiated surface of newfound authority–rather than the mountains, shores, coastal edges and lush forested landscapes of the fictional maps so compelling in their fictional worlds.

Terrestrial Curvature in the OSGB36 Grid, 1936 Ordnance Survey

–that must have inspired increased anxiety as an undifferentiated space of the nation, alienated from its past. We rarely interrogate the appeal of travel in fantasy worlds as mapping an escape from other presents, and other imminent threats. But they were. As much as finding solace, there is perhaps some historical balance in remembering that, from the disruptions of the Blitz and bleak hopes of the British future to darker times of the present, but the charting of these travels, from beginning to entropy, demanded new maps, and signs of spatial orientation. Did the need for new maps for a new age not inspire the traumatic shift to a new world of mapping in which both Tolkien and Lewis wrote in Oxford, and that inspired the experimental adventures both began in the 1930s of writing works for children?

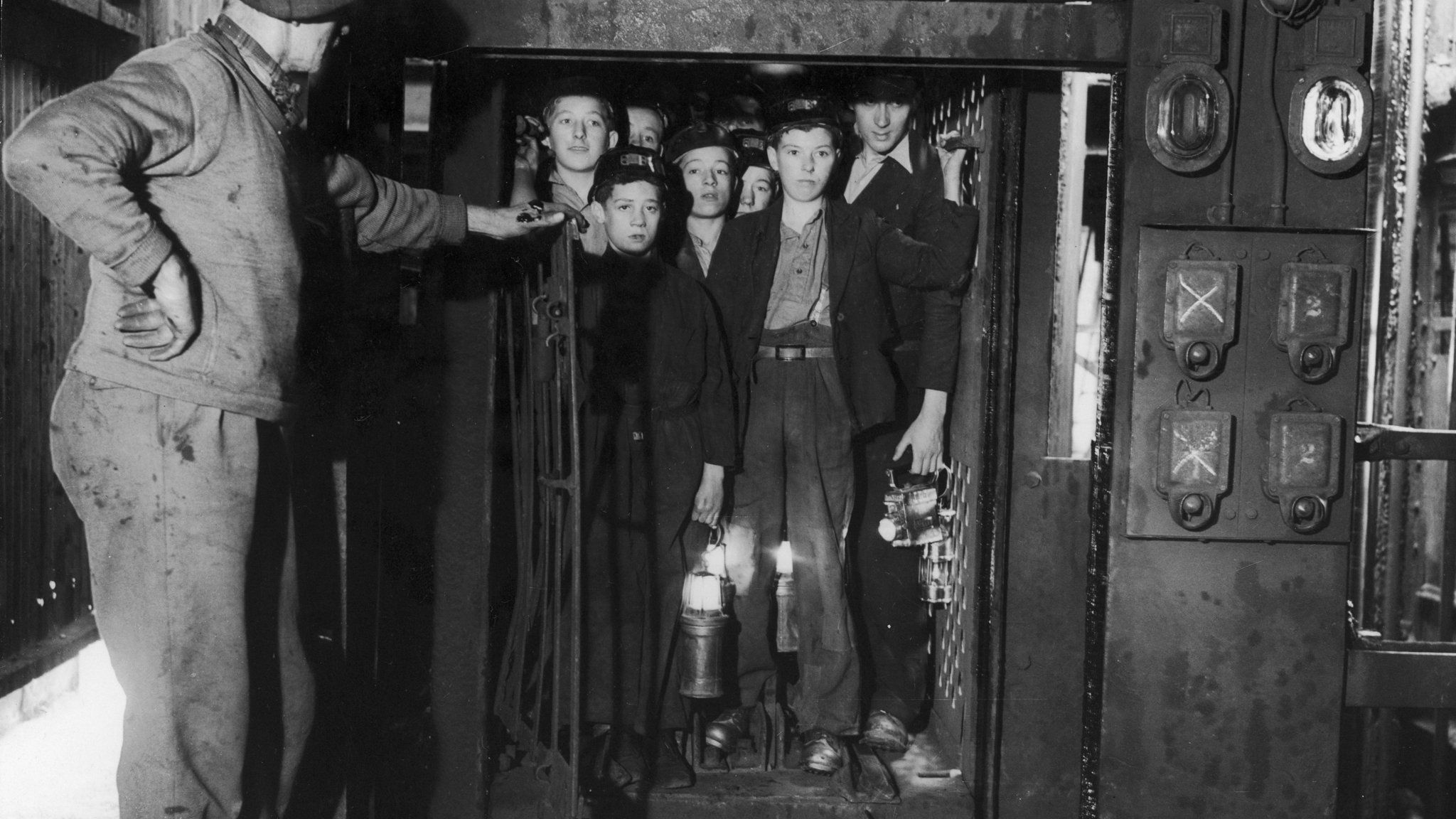

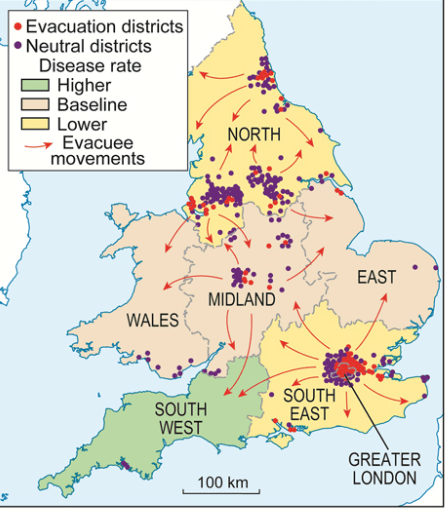

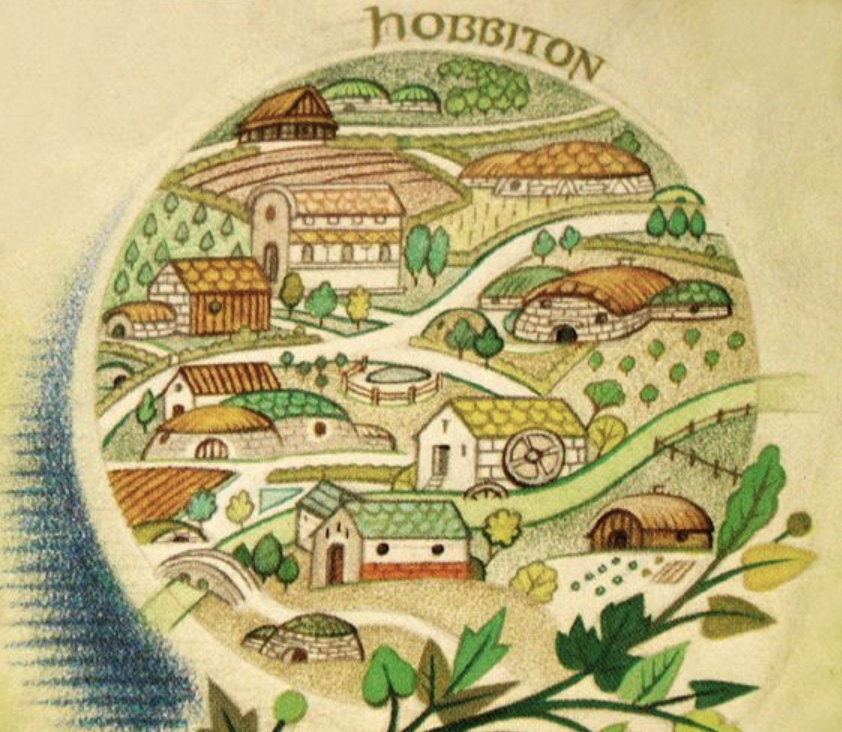

1. The mass-movement transfer of children out of cities September, 1939 to 1945 was a backdrop for the creation of fantasy worlds of a far richer sort, less tied to railways, speeding past countrysides, with gas mask boxes and without their parents, the largest migration in British history,–and definitely in the twentieth century, that sent over 1.5 million children to uncertain destinations, and along relatively uncertain maps. Children living in designated “Evacuation Areas” like Greater London, Birmingham, Bristol, Glasgow, and were transported by Operation Pied Piper to billets in more rural areas as Whales, East Anglia, or Kent–if they were not conscripted to work in mines for national service after 1940. But the entrancing maps that Tolkien drafted of the Shire, and later sketched of the greater canvas of Middle Earth, offered alternative modes of spatial literacy whose geography would have been intensely appealing–if not therapeutic–for the billeted children.

British War Museum

Girls at Paddington Station Departing London, 1939

The Pevensie children were of course, one classic example, packed off in the boxcars that evacuated so many children from London in the dangerous days of the German bombing of the Blitz, for voyages to places that were in part so truly terrifying because they lacked a clear maps. The urgency to maintain calm on the rail cars on which young children were “sent away from London during the Air-Raids” to “the heart of the country” were indeed a forced migration,–transported from the terror of air raids that fractured London’s landscape for safety and the nation’s future. To be sure, Lewis’ deep friend J.R.R. Tolkien had taken part in major offensives in trench war–and perhaps turned to mythology in part as a release under shell-fire, as well as in tents and dugouts. But his mapping of the world of his novels has offered a compellingly immersive landscape both by its texts and in amazingly detailed cartographic terms. Tolkien would never see his work as a novel–he preferred “historical romance,” its transporting of readers far from the battlefield repays analysis and contextualization as mapping a new world, mapped very differently than the sectors of safety–and leading children from London, Glasgow and Birmingham to arrive in the Southwest.

Hopes of offering a new map for children in dark times animated the composition of two of the most famously illustrated fantasy books of the twentieth century, C.S. Lewis’ much-loved Chronicles of Narnia and J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Both have continued to transport readers through some of the darker days of the twentieth century, enjoying renewed interest across the twentieth century’s dark spells. While Tolkien’s visionary inspirations are often tied to his first-hand experience of wartime as a signal officer who arrived to at the end of the Battle of the Somme and lost many of his friends on the Western Front, whose dark landscapes were displaced into fantastic lands. Tolkien confessed to having created to process his experiences by “escapism,’ . . . really transforming experiences into another form and symbol,” of a battle between good and evil, if not process the trauma of a war that left all but one of my close friends dead,” shaped by “coming under the shadow of war to fully feel its oppression.” But the landscapes in which the war was displaced far from Europe’s battlefields held out a sense of hope in ways their authors had intended. The addition of the cartographic apparatus of both books was an integral part of the landscapes they open for readers, and demands to be analyzed and examined not only as illustrations, but an integral part of the new worlds that the books created at a time when both authors felt the absence of adequate cartographic tools able to engage them in the present day.

The cohort of Pevensie children werelucky in their fortunes as they stuck together as a team, but, of course left London to enter Narnia’s world–which we enter, as readers, with them–even if they did so without maps: they get to be Kings and Queens, of course, to restore normalcy to another world they hadn’t noticed existed or known, for which they don’t need many cartographic tools. That world was rather revealed to them by a sort of grace, which the printed book offers a portal, if they used either a wardrobe whose timbers are able to transport them, we only later learn, to Narnia’s alternate universe, as they were built from seeds of a magic tree, or the clever device of poetic transport of a picture frame. But although we treasure the work of who we regard as fantasy writers from Oxford, as C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien, who wrote to create enchanted lands as maps for the future for the grim wartime years, we are less aware or conscious of how both works benefitted immeasurably from new cartographic skills that their authors urgently sought out. Their mutual cartographer, a refugee of sorts from nautical mapping teams who deserves to be remembered for her considerable graphic skill, Pauline Baynes, who devised the valuable and enchanting–if not essential–cartographic apparatus for their written works.

But we needed and to an extent relished being provided with actual maps. The enchanting nature of these media–good wood, perhaps, and stolid furniture, not factory-made but cut and planed by hand in a way no Pevensies had perhaps encountered in London childhoods–is a refuge from modernity. But the their entry to a world that stands at an angle to our own is a pure escape. Only in a world at an angle to the postwar Europe were both authors able to communicate the sense of nature as a screen whose removal might unveil the harmony of man, nature, and the divine in new way; the sense of the other world was, to be sure, inherited for a generation of Oxonians enamored by William Morris, nurturing hopes of finding the place of the divine–and inviting young readers to map the place for themselves–emerged in the rather specific place war-torn world both Lewis and his colleague J.R.R. Tolkien wrote and lived, as well as drank, walked, and wandered. And its remove took its spin from the sense that such a world might exist in Oxford, not only an old university town, but a town of a sacred center, and a sense of the older England of the past, which, from the perspective of postwar England, was akin to a pleasant land once more trying to peek in, and was convincingly mapped, or remapped, in full dimensionality, in he these two powerful fantasy worlds.

As dedicated Ramblers, Tolkien and Lewis were both deeply dedicated pioneers of open space. Lewis, of course, was the author of Pilgrim’s Regress, that deeply autobiographical homage to Bunyan that is a pilgrimage across his own philosophical imagination, an odyssey in hopes for spiritual satisfaction, to the island paradise he aspired. Oxford, in the same, also fell off the modern map. As the continuity of modern space was defined by grids, and the creation of a continuity of air-travel, flight paths and radio space, Oxford remained a curiously earth-bound city, removed from the gridded space of the postwar world. Oxford had long been a place of paths, walkways, bicycles and pedestrians, of cobblestones and medieval towers and churches more than impermeable surfaces and of towpaths beside canals, more than roadways like the A40 or A34.

While the hum of cars could often be heard from the Thamespath, the sense of a respite form the modernization of English space in the postwar period nourished the novels of Lewis and Tolkien, as sites of resistance to the flattening of lived space, that offered the opening for the creation of imaginary worlds at a curious angle to the present. The important contributions of mapping these openings of fantasy spaces demanded new sorts of cartographic skills and tools that were desired for the postwar generation, which Baynes’ maps were extremely important, and if often aesthetically valued, her rather understated contribution may be undervalued in offering a cartographic tools, as well as apparatus, born not only from storied traditions of book illustration but from the skill with which she offered her mapping expertise to map the shorelines of new worlds that lay off the grid, providing something like treasured icons of imagined worlds that have had an amazing durability in the twentieth century, far more than their authors ever anticipated.

2. Even as the rural midlands area of Oxford was suddenly changing, the thrills of Morris’ Thames and its roughness a thing of the past, and the walking paths of the past slipping from memory, muted with urban expansion of a redoubt of timelessness, the city seemed chock with repositories of a deeply local knowledge. The acute danger of its timeless present slipping away in the rising tide of postwar globalization was newly acute. The flights over Oxfordshire that, as the remapping of military space–and global strategy–threatened fears of the disappearance of the local and of local knowledges that had structured the early modern and medieval worlds. This was a task that called for more than narrative invention. The fading away of a past image of an almost vanished place–

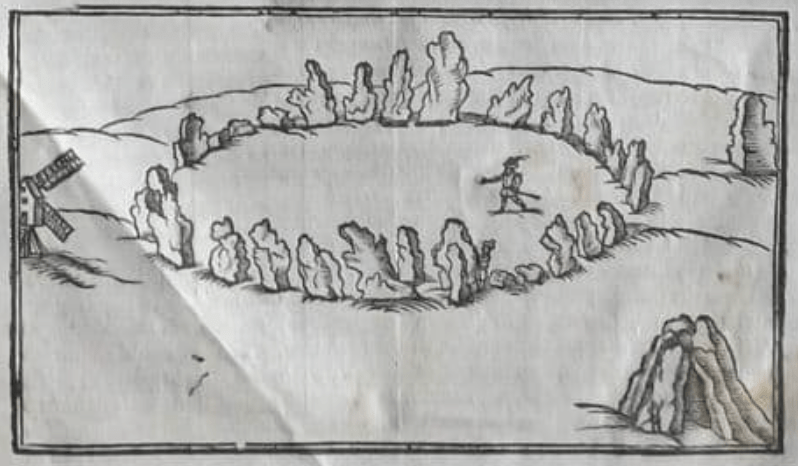

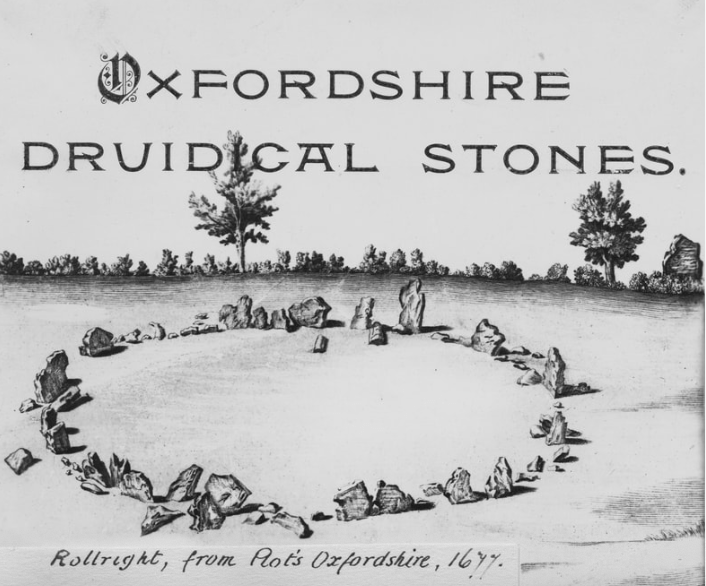

–was a scenic view of barges, thatched roof cottages, and river meanders, village roads lined with shops, pubs, and even druidical stone circles of rough-hewn upright sarsen stones, that themselves seemed like witnesses of an earlier lost time. The materiality of the past, fast-vanishing in actuality as much as in maps, created a lure of the fading that many of the myths of the world of Lewis and Tolkien has treated as a question of words and worlds,–rather than re-mapped worlds, diminishing the powers of maps in fashioning alternate worlds. The prestige of both encourages regarding their fantasy stories as verbal creations of evocative wizardry, rather than responses to the many portals of the past scattered across Oxfordshire, from the chapels of colleges that appear a manuscript out of the riches of the Bodleian library to the stone circles at Chipping Norton,–a neolithic monument that won newfound value during with the mapping of England in the wake of World War II, as a new scale of destruction must have created a new demand for the enchanted landscapes of a timeless past. Tolkien vowed or protested n 1956, after publishing Lord of the Rings, “there is hardly any reference in The Lord of the Rings to things that do not actually exist, on its own plane (of secondary or sub-creational reality)” as if protesting the imaginary nature of Middle Earth, and the relations of place to fantasy world have been widely noted–as for the work of C.S. Lewis–almost in a sense of urgency to bring the ideal or intense tranquility of both worlds closer to our own, or discover the plane or angle at which the realm of Middle Earth might be imagined.

As much as the compelling edifice of their fictional worlds rest on inventions and artistic genius, Oxfordshire offered an open archive for both writers to elaborate sacred centers for their readers–centers of moral weight and compelling drama that demanded heightened points of orientation. If Lewis incorporated a richly cartographic sense of heavenly spheres from Dante, much of Narnia reflected the ancient landscapes around Oxfordshire. The excavation of the standing stones capped by a large quartz capstone suggested the stone table on which Aslan suffered in the version of the passion Lewis transported to postwar England, the prehistoric burial site now thought to date from 3700 BC Arthur’s Tomb was among the ruins imagined s druidical monuments in the rural countryside; that are echoed in Narnia, by Aslan’s Stone Table, of sacrifice; the neolithic burial site recalls a table fractured down its middle in two, taken as evidence from a past power or visitation in Herefordshire. The ruins were celebratory excavated by English Heritage as riches–as one of the country’s most significant Stone Age monuments, whose relationships to neolithic landscape monuments of the increasingly remote period 4000-2500 BC, which is still being excavated today are an uncanny echo of the Stone Table may have offered a basis to imagine the topography of the Stone Table where the world of Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe dramatically concludes . . . .

Arthur’s Stone, c. 3700 BCE/University of Manchester

The ruins recalling the Stone Table upon which Aslan dies is a site of Deep Magic in the fantastical world, but is modeled after a Stone Table that lies not far from Oxfordshire. If the monument of Arthur’s Stone is acknowledged as “one of the country’s most significant Stone Age monuments,” less well-known in Lewis’ lifetime, and far less well-preserved, it offered a fictional prompt to romanticize the past of quests in an era of airline flights and landscapes overlays at a distance from the bearings of a lived terrain, by the psycho-geographic excavation of a hidden landscape of primeval presence, a map encountered in new ways on the printed page. For sites as the Rollright Stones, long imagined as an ancient burial of mystical significance in the landscape, the ‘druidical stones’ were venerated as points of access to a pagan past by many, and evidence of the deeply indigenous cults of English burial, preceding the conversion to Christianity, of a deep moral interest. Yet if the human-size prehistoric stone circles may appear in new guise in Middle Earth, as the Barrow-Downs, the resting place of the dead, among the elements of the Cotswalds that is transposed to the fantastical world, and is echoed by the stone circles in Narnia, often associated with the other Neolithic megalithic monument, the ring go “hanging stones,” at Stonehenge.

Rollright Stones, Oxfordshire, twenty years after they were described in Thomas Browne’s Urne-Buriall (1658)

These “druidical stones” were evidence of a lost landscape of the past, able to be accessed by those with proper directions and, perhaps moreover, proper orientation to place. English Heritage had been materialized and sought in Lewis’ (and Tolkien’s) texts in ways that remedied the disappearance of a fast-receding past, hoping to enchant younger readers even if an older audience of readers had seemed, back then, to be less accessible or indeed lost, but might be revivified. There was a sense that the discovery of ancient sites of burial of an earlier mystical if not medieval age is revisited in the fiction of Tolkien and Lewis as a way of investing landscapes with magical meaning in a dark era of the present. The mysticism of sepulchral settings as portals to other worlds was animatedly tied to myth by the Warburgian Edgar Wind, the erudite emigré art historian who inspired both by his arguments of the modern relevance of pagan images of allegory and mysticism, who saw the blurred nature of Christian and pagan symbolism within a “language of mysteries” combining ritual, figurative, and magical senses in Renaissance art in postwar England in particularly influential ways–tempting to link to the sites of initiation in both works. Such sites evoked a precautional map of sacred meaning, even if pre-Christian burials.

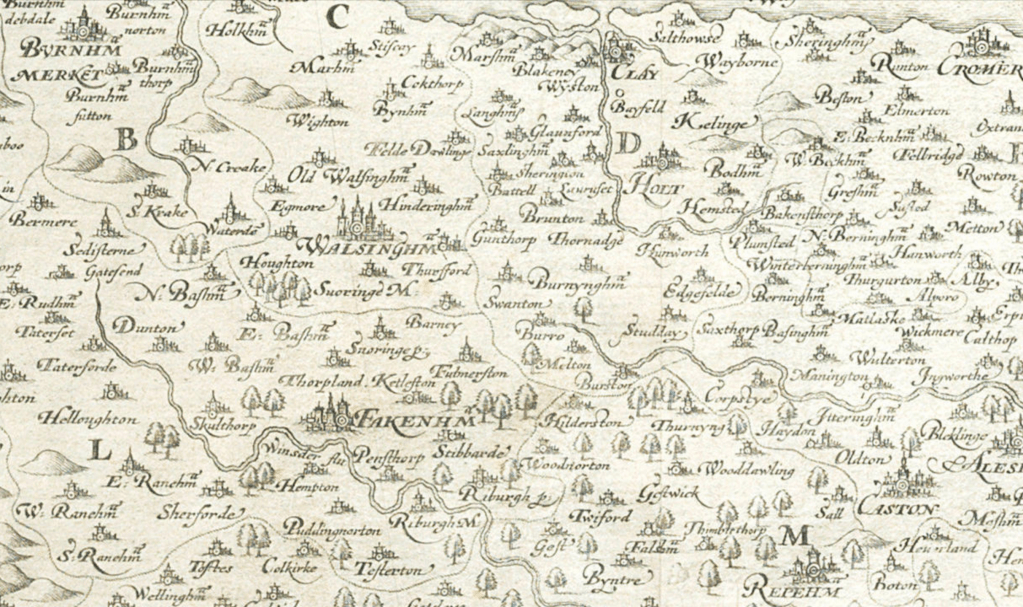

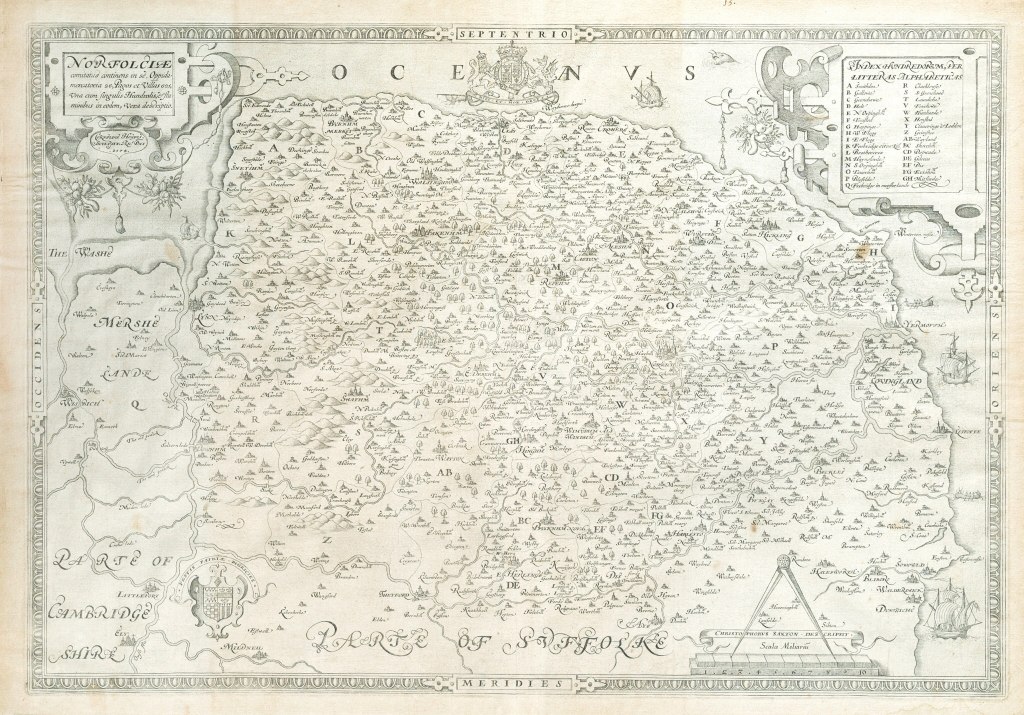

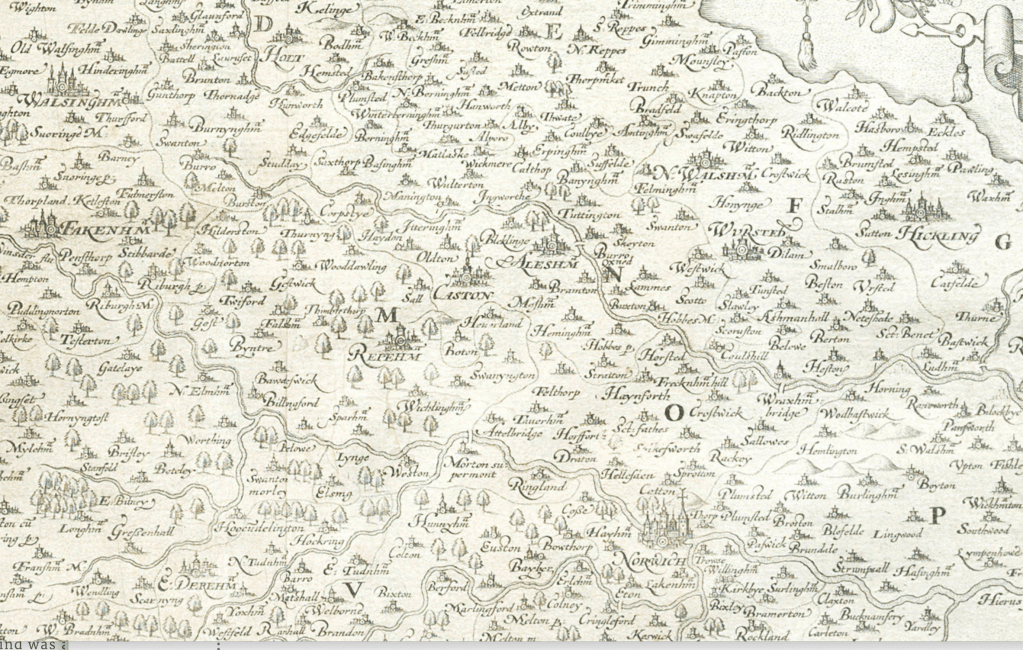

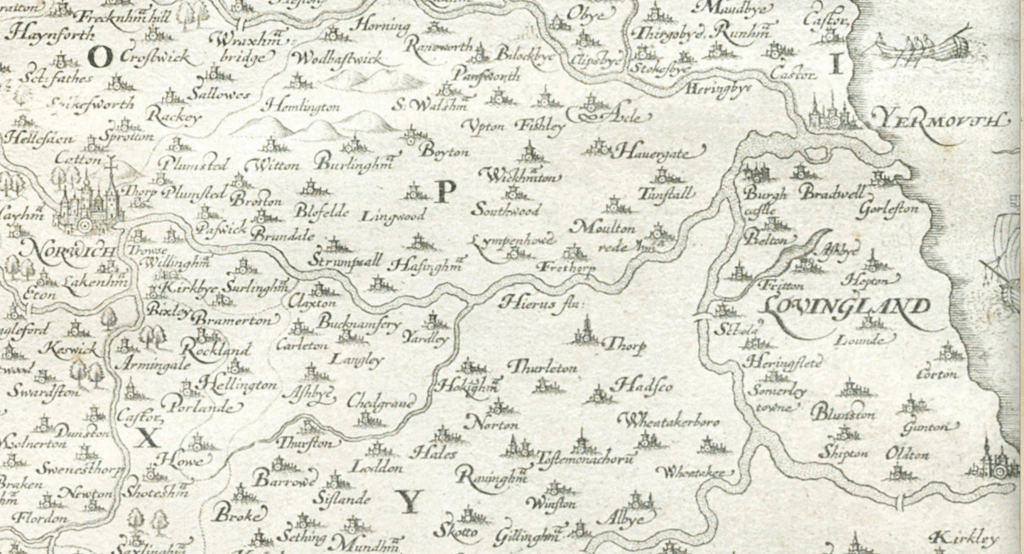

Such neolithic sites long carried the promise of transport to a mystical or pagan past of deep spiritual meaning, as a refuge from the present or hallowed ground. The discovery of the “Sepulchral Monuments” of as the “rurall interrments” of the forty to fifty Urns containing bones that were found in the fields of Walsingham in Norfolk’s dry and sandy soil, of uncertain date, that Browne speculated might be antiquities of Roman origin, not noted on printed regional maps. The urns offered a sense of portals to a consideration of the afterlife, and a sense of a haunting of the landscape with a sppiritual realm Browne was perhaps prompted but the limited content even of the detailed maps of nearby shires in Christopher Saxton’s detailed wall maps of twenty English counties, detailing not only the the coast but also roads, merchant cities, and villages of “all the shires of the realm,” removed from the adjudication of government or property lines. Saxton, “the father of English geography, was granted license to survey in the mid-sixteenth century including Norfolk, in hopes to rival the detail and accuracy of the Ortelian Altas in twenty large engravings–

–as a legible map of English lands reprinted through the mid-seventeenth century, when they were replaced by increased noting of antiquities, coins, and ruins. If Saxton focussed on royal lands, the large cartographic record of the surface was complemented by Browne’s excavation of burial sites, tracing burial urns in his meditation on how “men have been most fantastical in the singular contrivances of their corporall dissolution,” attending as a learned physician to the topics of mortality and the dissolution of body and soul. The Renaissance polymath set the recent discovery of urns “to preserve the living, and make the dead to live, to keep men out of their Urnes, and discourse of humane fragments in them” to offer a care for the living on a deeply scholarly plane. His writings addressed the “need [for] artificial memento’s, or coffins by our bedside, to mind us of our graves” in deeply moral ways, and transcend morality, chastising the vanity of attempts to “hope for immortality or any patent from oblivion, in-reservations below the Moon” in a world wheres “there is nothing strictly immortal, but immortality,” despite the long-lasting hope of many prechristians to “subsist in lasting Monuments,”–but offered a compelling map that might repay attention far beyond Saxton’s terrestrial record of Norfolk, Norwich, Yarmouth, or Walsingham–and indeed a moral guide to the attention to the soul, of special relevance to the Oxonians.

Norfolk with Norwich, Yarmouth, and Walsingham

“We present not these as any strange sight or spectacle unknown to your eyes,” wrote Browne, as –one fancies–Tolkien and Lewis aimed to write for their readers, “drawn into discourses of Antiquities, who have scarce time before us to comprehend new things, or make out learned Novelties,” as “the most industrious heads do finde no easie work to erect a new Britannia,” as he situates the Urnes containing bones that were resting in a field among the burial monuments of Roman Britain, Rome, and burial customs of the world. The discussion of “carnal internment or burying” traced the burieal, viewing Norwich urns and of internment from a global lends across many nations an over time, a reflection on mortality and antiquity of lost Roman Britain, and “old East-Angle Monarchy [on which] tradition and history are silent,”least of all Saxton’s engraved wall maps. If the maps are often read as reflecting a desire for coastal fortification, Saxton’s comprehensive cartographic record presented a model of geographic contemplation Browne would have been conscious, and, this post argues, one might do worse than to examine the works of Lewis and his friend Tolkien as writing in response to the dangers of a cartographic revolution of the mid-twentieth century of mapping not nations, but global position, removed from the landmarks or lay of the land, and the spiritual problems that the absences of attention they felt such maps posed.

Saxton Map of Norfolk, Norfolciae Comitatus Description Continens in se Oppida Mercatoria XXVI , c. 1573 (reprinted 1641)

Was the Urne-Buriall not a new form of map, meant o be read against Saxton’s elegant wall maps of English counties, detailing the towns, roads, and markets in “all the shires of this realm”? The authority of Saxton’s survey of Norfolk changed by the seventeenth century with the increasing inclusion of coins and antiquities in English maps, as the twenty engraved wall maps of Britain’s shores and counties in a scientific manner was filled with increased antiquarian detail. If Saxton displayed counties as aesthetic unities, beyond administration or local border disputes, as sites of princely pride and patriotism, Browne returned to the “perfect geographical description of the several shires and counties within this realm” in a written map of a deep history of humanity and learning, written “not to intrude upon the Antiquary.” The forty to fifty urns discovered in a field in Norfolk provide the pretext to map of global burial customs in an expansive perspective on mortality, ranging far from the coast of royal lands of Norfolk, Oxfordshire or Buckinghamshire. Browne acknowledged the past population of Roman Britain–and antiquarian discovery of Roman swords, houses, urns or copper and silver coins in nearby market towns of Thetford, Yarmouth and evenLondon, but their survey goes beyond judging the burial grounds, customs and rites far beyond Norfolk’s shires of Norwich; Yarmouth; Burghcastle; and Brancaster–in a historical survey beyond written records, comparing Christians care for “enterrment” against obsequies and ancient burial monuments from the vainglory of pyramids, arches, or urnall interments Christians despised.

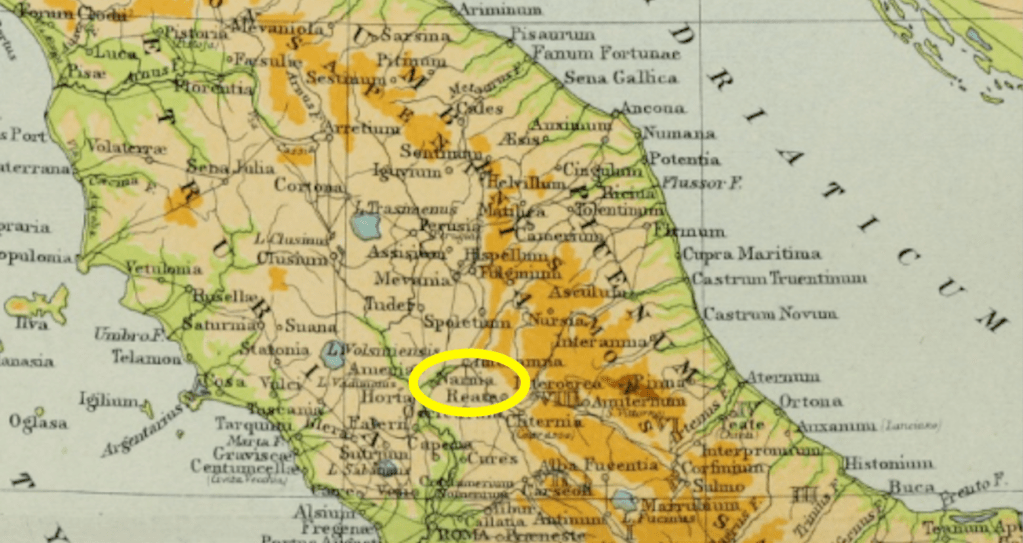

While Lewis demanded to seek a map far beyond the nation, and in less dour coloration than black ink, the burial points were entrances into a map outside the nation, and to a realm of far more and unbounded interest and greater harmony than this world–and indeed as saturated with colors as when the spell of everlasting winter is broken in Narnia, and that the color saturated maps of Baynes later work reflect as a parallel universe. The animals peopling the Narnian landscapes did reflect Lewis’ own love of landscapes of his native Ulster, to be sure, childhood memories of “which under a particular light made me feel that at any moment a giant might raise his head over the next ridge” in private letters, but the unbounded harmony, as much as recalling the County Antrim seaside where he spent summers in childhood, was famously discovered in a printed map–so struck by the Etrurian hillside town of Narni on the road from Rome to Assisi, in Murray’s Small Classical Atlas, famously, so struck by the name to underline it soon before being mobilized for war service.

Murray’s Small Classical Atlas (1904), detail of Italy Highlighting “Narnia” (circled in yellow)

“Between Rome and Assisi” may be a way of describing C.S. Lewis’ spirituality, if not the Narnian landscape from which it was born: in Murray’s atlas, it was identified not as “Narni,” but “Narnia.” Perhaps the bucolic toponym in Murray’s Classical Atlas struck him as a land apart from sectarian violence, even not knowing the green Umbrian hills, or that this was the land of the success of the first Franciscans, removed from Rome’s authority the land of the merchant’s son who took vows of poverty and preached to pigeons before befriending and forming a treaty with a wolf threatening the nearby town of Gubbio, entering the wolf’s territory to speak with the species long terrifying the village, and that still terrify Umbrian farmers’ fields and their domesticated animals. The idea of a land free of sectarian violence was well chosen for the fantastic realm of rolling hills and and forested mountains and great rivers, north of mountains and south of ruined cities’ barren plains.

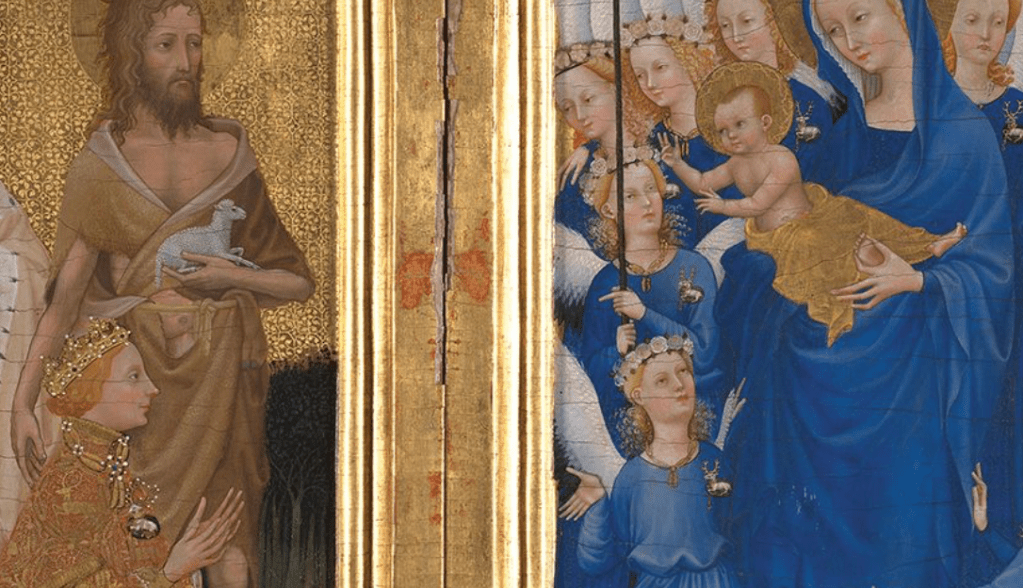

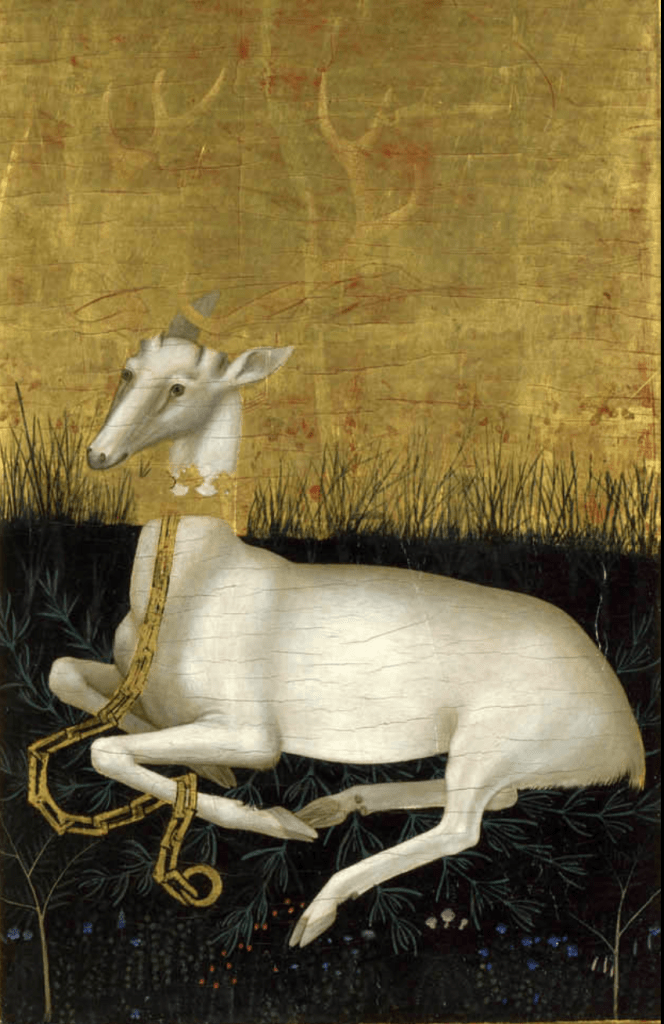

The bright landscape of Narnia was mapped by enriched colors,–akin to the ultramarine lavished on the field of gold that may make the diptych so spellbinding and entrancing in the rare sacred English medieval paintings that it was spared destruction. The reproduction hung in Lewis’ rooms in Oxford was, after all, an image of a redeemed England, by a monarch intercessor, who had redeemed England and the created world featured the courtly emblem of hart the king mandated to be worn by members of his court. If the image of freeing the world form faults recast what was vilified as Richard II’s distribution of badges to his favorites as a sumptuary extravagance upsetting social rank, now sported by an attendant angelic choir over their hearts, and the hart lying on its obverse in flowered fields; the sinless white animal was an emblem of how Richard II placed himself and England under protection of the Virgin, perhaps echoed in the White Stag who protects Narnia.

Wilton Diptych of Richard II (English or French, 1395-9)/National Gallery

Wilton Diptych, by unknown painter of international Gothic style; details and Obverse

Tolkien and Lewis adopted actual local monuments of the region to access unmapped realms with a form of magic realism that lies far “off the grid” of gridded maps. Do not the itineraries of Middle Earth and Narnia mark a changed subjectivity before a new regime of mapping open a grid, as much as escapism into other worlds? The combination of medievalism and Christianity in a map of personal reflection for a young audience is in a sense a modernization of the relics of uncertain origin and antiquity that offer Browne a model to reflect on mortality. As Browne excavated burial customs from Norfolk, and burial sites as Oxfordshire’s neolithic Rollright Stones, celebrated as a site of burial that haunted the works of Lewis and Tolkien, as well as Browne, the two fantasists remapped ancient sites for readers at a remove from their current world, mapping itineraries at a remove from the world to recover new orientation. If long seen as sites of mystical meaning and prompts to the imagination, Tolkien and Lewis regarded such neolithic monuments as entrance points to other more fantastic landscapes of enchantment or narrative way-stations as they wove alternative maps around the ancient remains of the landscape as prompts to their writing, but as if they were entrance points or portals to weave storylines that haunt the imaginary so much that the shock of recognition at their discovery seems a rediscovery of a vaguely known world.

If the stone circles of the Neolithic or Bronze Age were remembered as sites where knights were transformed to stone pillars by witchcraft, the monuments “not perished by the injuries of time” in popular guidebooks of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries of pre-Roman Britain provided points of entry in the middle of the twentieth century to expansive landscape not present in maps. Ancient objects catalogued by antiquarians as William Camden’s Brittania belonged to Browne’s “deep discovery of the Subterranean world, a shallow part would satisfie some inquirers,” some “scarce below the roots of some vegetables” and others deep below the British landscape, others above, as the stone circle, if not always evident in the “thin-fill’d Mappes we find the Name of Walsingham.”

Rollright Stones inWilliam Camden, Britannia (1695, originally 1586)

The ample ways in which Lewis and his friend Tolkien drew on Oxfordshire as an archive of sorts reflects their interest in the combination of pagan with Christian symbologies, a mixture that one might indeed trace to their shared fascination with the wildly popular lectures of emigré art historian Edgar Wind, who lectured in the Ashmolean Museum on pagan antiquity and its recovery that convinced Lewis, himself a medieval literary scholar, that “the writers on art have hopelessly outstripped the writers on literature of our period”–citing Wind, Gombrich, and Szenec–insisting that many paintings of the Renaissance resisted saced or profane character. His interest in shaping a non-conventional view of Christian values .led to his interest in Renaissance paintings of mystic value and symbols, and the symbolic landscapes of sacred sites in Oxfordshire overlap in fascinating intentional ways with the symbolic centers of Narnia as well as Middle Earth.

Both Lewis and Tolkien used such monuments to romance enchanted itineraries unable to be found in the abstractly gridded maps of England of the 1930s, that led to the postwar authority of the global Universal Transverse Mercator by organizing an undifferentiated bearings of global position. Both turned or returned to a romance of the travel narrative and quest along guideposts that promised a needed roadmap based on the timeless ancient landmarks of the country, or a sense of landmarks that existed, as the weather-worn Rollright Stones, a stone circle in the Cotswolds Browne was not alone in seeing as an ancient burial chamber to access a remote druidical past not evident in maps. (If Browne ends by considers the “superannuated peece of folly . . . . to extend our memories by Monuments . . . and whose duration we cannot hope,” the ring of weathered stones about interred bodies seemed outside the nation, or national map, as sites of contact with a remote past.). The new maps that were drawn for both series in fact opened landscapes that were populated by talking animals and people, forest people and talking organisms, who would be less likely seen in a purely manmade landscape of the present, or on the coordinates of a OSGB36 map, where the grid took prominence over the countryside, and indeed the ancient monuments of mortality of the past.

Did both not demand a new cartographer to render the monuments and topography in compelling terms? The written worlds of enchantment they created demand to be examined not only as an alternative Oxford–if the spires echoed in resonant ways with both works’ alternate worlds. As such, they have long continuing to attract tourists and encourage exploring the river walks the two took, the pubs they shared literary hopes, or the green fields about which they conjured medieval forests–including first and foremost the gigantic branches of a towering black pine, planted in the mid-1830s, in Oxford’s Botanical Garden, that Tolkien visited since a student at Exeter, and whose expansive branches were not only a basis for tree-like Ents of Middle Earth, became transmuted to a muse, a point of orientation as much as aesthetic reflection–he named the tree Laocoon, the ancient sculpture of a man entwined with snakes. (While its towering limbs were recently felled, Tolkien felt it a preferred site for aesthetic reflection served as a model for the old Ent, the aged Treebeard, singled out by the wizard Gandalf as “the oldest living thing that still walks beneath the sun on this Middle-Earth,” in in Two Towers. The pine tree he had placed in the depths of Fangorn Forest and other monuments conjured an ancient past worthy of William Morris’ Icelandic landscape.

The tree, transported by force of the imagination from Oxford’s Botanical Garden to Middle Earth’s ancient and densely wooded Fanghorn Forest, whose name derives from the Elvish term for “Black Forest,” in reference to the fearful nature of its dark shade, offers a connection to deep time, as one of those “real reference points” of magical worlds–akin to the stone table, the lamppost, or for C.S. Lewis or Rollright Stones for Tolkien–and landscape of Oxfordshire and Wales Tolkien felt of such extreme import any illustrator of his books be well-versed and personally acquainted before he would hire them as illustrators. Tolkien may have regretted the limited maps he included in the trilogy, in April 1956, a year and a half after thee first volume, Fellowship of the Ring, appeared. As any “‘research students’ always discover, however long their are allowed, and careful their work and notes, there is always a rush at the end when the last date suddenly approaches on which their thesis must be presented,” he wrote in retrospect, “and so it was with this book and the maps . . . ”

Christopher and J.R.R., Tolkien, Fangorn Forest (above) and Pauline Baynes’ Rendering of Middle Earth Map

The cartographic apparatus critically added to both works demanded the authors have assistance of a more detailed cartographic canvas, that their common illustrator, Pauline Baynes, would help provide. The forest featured at the center of the Tolkien map of Middle Earth and the map drafted by Baynes in 1969, the most authoritative source of learning about the topography of Middle Earth. If Tolkien had imagined a more complete cartographic canvas for readers, he famously insisted the place-names in the romance be preserved in translation, and “be left entirely unchanged in any language used in translation,” save in their final plural letters, as demanded by the language to which they were translated, using the toponymy he had carefully crafted and devised, over the years he wrote the series, 194=37-49, restarting chapters that Tolkien sent to his son in a serial form from 1944 from the military front where he was stationed in France’s Somme Valley.