This deeply sovereigntist argument is a denial of existing laws, and as imaginary as true. The announcement in mid-April offers grounds to deny sanctuary to refugees, ramped up the denial of birthright citizenship as a misinterpretation, as not meant to include birth to parents not legally present in the country, or on a temporary work permit, first promised in 2018. The end of birthright citizenship–an international law common to most nations in North and South America–and pillar of constitutional law was promised to prevent an estimated 4.7 million from gaining citizenship by 2050, by the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute, the idea of citizenship as a legal loophole allowing immigration has led anti-immigration groups to argue citizenship should not be extended to those not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States as citizens of a foreign nation, policing them outside American jurisdiction. One need only listen to the terrifying threats of the anti-immigration federal advertisement miscast during newscasts: after Secretary Noem expressed collective thanks to President Trump for “security our border and putting America first” in an ad released just a month after he took office, she personalizing the obligation of the nation to Donald Trump, marking the end of “wide open” borders due to “weak politicians; more than cite the law, she targets migrants as if animals, not individuals with rights or families.

Blurred borders are central to the Trump regime, and even to the New World Order that grants no real limits to America–and indeed erodes the system of nations to promote American greatness. The blurring of national borders in the Trump 2.0 regime begins with a sense that the border is controlled unilaterally by the United States. The broadcast warning message articulates a new sovereign map not based on rights in a menacing deadpan voice without a hint of emotion: “Don’t even think about it. If you come here and break our laws, we will hunt you down.” Final shots pan over the border wall, flashing police sirens apprehending immigrants, and concertina wire incongruously intercut with peaceful law-abiding men placing flags on homes, teaching children to ride their bicycle, and close on the strongman signing executive orders and waving from the White House before ending at four stern visages at Mt. Rushmore Trump is waiting to join for delivering on a promise that “Criminals are not welcome in the United States.” The terrifying message is that there is no safe space–no restraints would exist on immigration agents from entering educational, public assistance or religious sites previously deemed“sensitive” locations, in a broad decay of our civil protections across the nation. The ceiling television advertisement celebrating sovereign independence that the advertisement praises as as an “imperative to renewing America,” and a sure way to create crises in social services, public health, education, and life of immense social costs, as well as considerable economic chaos.

Trump proudly channeled Musk in a call to colonize Mars in his inaugural as part of a heroic defense of the country that fit his expansionist ideals–and set the tone for its triumphalism. The aim is perhaps best understood as a an exaggerated reflection of a desire to expand sovereign space to outer space, a staking of outsized ambitions and maximalist goals that rival Musk’s long promised goal, and reflects a belief that perhaps the budget of the United States can finance the hope rooted in early science fiction of investment of public monies on a poorly defined and framed ideal. The pet project of Musk was a reach for bombastic patriotism, but indulgent metaphor of the redirecting of funds to extra planetary exploration under a patriotic banner was misguided, without any vision or budgetary allocations, but exploited to get attention.

Trump seeks to curtail the space project by eviscerating astrophysics, earth sciences, and telescopic programs that would be crucial to any mission: shearing $5 billion from the program shifts its focus to engineering space travel in isolation–a tactical omission. But inflating a vision of technical management on a global map magnifies American technocratic expertise to expand the image of executive power. But it is also a wild overstepping of sovereign limits that suggests the improvised and ungrounded nature of such claims as if they were acs of sovereign power. Elon Musk’s SpaceX has similarly focussed on the problem of manned missions to Mars, as if the voyage was the end in itself, the absence of any plans for establishing a station or base on Mars, or providing needed oxygen and food for settlers,–beyond any guidance system and fuel for such travels–illustrating blindspots in the engineering perspective on space travel, rather than scientific knowledge or actual expertise for projects of extra planetary travel or extraterrestrial colonization. While he has cast himself as a new rocket man for a new era, if Musk has supposedly “faded” from the current administration, the premium on technological engineering of a manned voyage to Mars seems to remain a staple for the Trump Presidency, seen as a hallmark of “restoring” America on a global map–and making it Great Again.

Proponents of Mars travel argue Columbus had a similarly unclear a sense of the New World in 1491, ignoring Columbus’ fortune to encounter a biosphere and rich vegetational life, maintained by the indigenous inhabitants of North America’s plentiful atmosphere. There is no analogy at all. But the transhistorical comparison of technologies of mapping and exploration furthers a patriotic gloss on extraterrestrial travel in ways that further the ambitions of the Trump 2.0 administration, and to suggest an image of a nation that knows no frontiers: if the space project was born in the Cold War as a stepchild of Wernher von Braun’s public relations expertise as much as his science, which took a decade to launch Americans into space but led the super booster Saturn V rocket to land Apollo 11 on the moon, just a decade after the first space satellite, Explorer 1, Musk’s genius at public relations seeks to engineer a new rocket technology to expand von Braun’s practiced PR machine. If Musk has won Trump’s ear to cement a rebooted space program–if one that may sacrifice lunar landings in the end–for new patriotic ends, the synergy between the sharpie and the rocket suggest a new style of governance without borders, or a patriotic re-bordering, based in old mapping tools indeed–suggesting to this blogger’s eye a recycling of old iconography for new ends.

The power of the pen is poised to be elided with a new power of mapping, among other functions of clarifying blurred lines. The unerring nature of such apparent fixations as a slogan of rebrand his political identity in uncanny ways, both providing energy and channeling convictions around a mega-project whose very scale provided a way to expand and inflate his ambitions. The synergy of Trump’s crackdown on the ordering of the nation and the pushing of billions into SpaceX to devise a new program of extraterrestrial colonization suggests an insane boondoggle for the nation based on a rhetoric of transcending frontiers that sets legal norms to the side, perhaps finding a new way to see the nation as able to unilaterally occupy space.

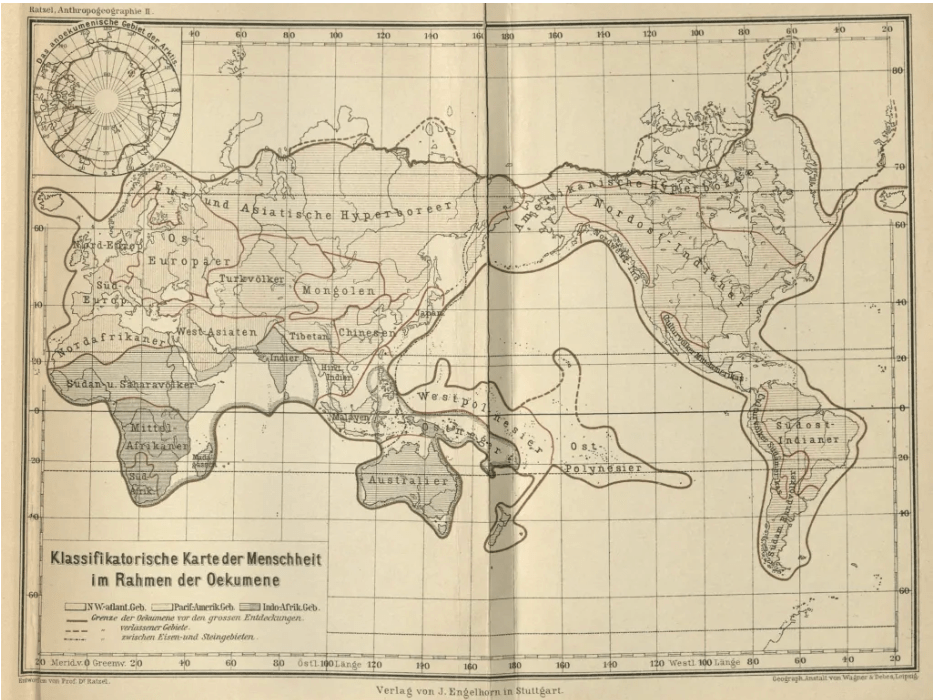

Amidst the recent raft of Executive Actions, programs announced with an onslaught but expectantly drafted by lawyers in previous years, the range of declarations that truly test the limits of authoritarian power are not only those restoring “biological truth” to federal government but those intended to restore what political geographer Friedrich Ratzel might call “geographical truth”–the global geopolitical order that cast globalism as yet another manifestation of an eternal struggle of nations for space that was defined not any nations, but by continents–an essentialization of geographic thought at the heart of National Socialist concepts of geopolitics and the demand for lebensraum–a concept that Ratzel had conceived and developed in 1901, long before it was adopted as a National Socialist dogma, in the disinterested language of political theory rooted in the social sciences as a “biogeographical term” of national expansion for national survival.

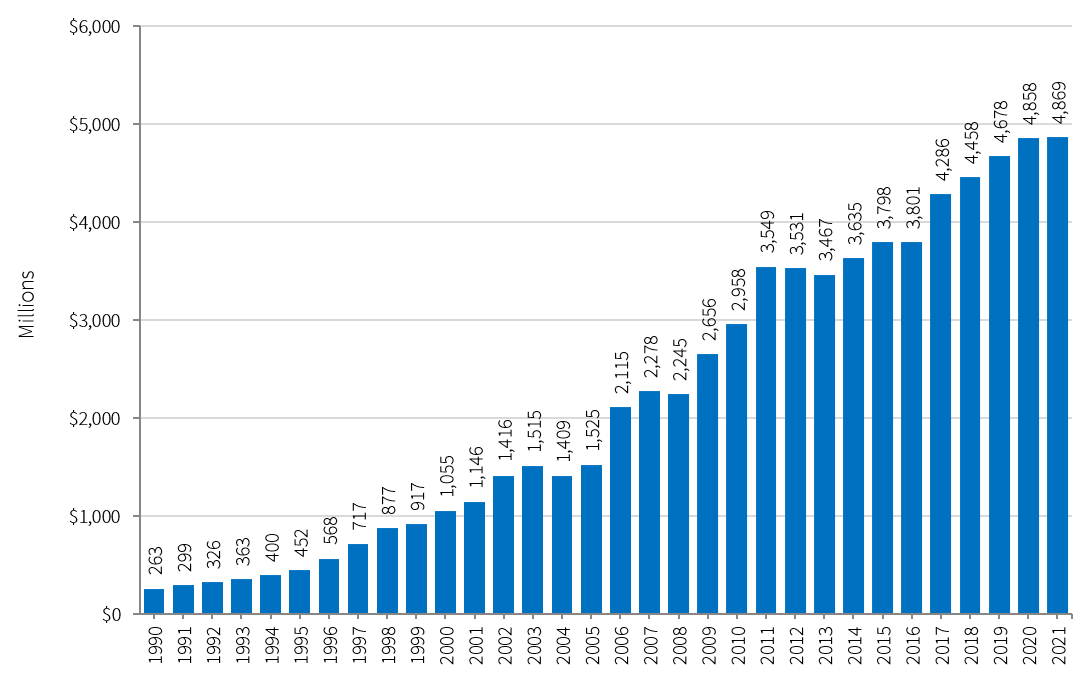

The concepts of border enforcement by military was expanded, as tools of surveillance expanded scrutiny enforcement by the precedents of 9/11 terrorist surveillance: the expansion of border security across the country as invasive tech curtailed civil liberties and degraded legal protection of undocumented immigrants far from the border, elevating border security a national priority–and offering ICE unfettered access to local databases centralize nation surveillance capacities of data harvesting of taxes, health data, social security, and other benefits, making the tax-paying immigrants subject to deportation by an Immigration Lifecycle Operating System (ImmigrationOS) purchasing airplane passenger data, personal credit history, car registration, and utility data, by expanding the surveillance networks of the enhanced counterterrorism operations permitted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. If ICE had already devoted $2.8 billion of the government budget to data collection services from 2008-21, per the Center on Data Privacy and Technology at Georgetown, the involvement of private sector in managing Immigrant Violator Files (IVF’s)from the Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act of 1996 set up a data-driven paradigm for deputizing local police and law enforcement with national tracking of “illegal immigrants” that offered a force multiplier of surveillance powers that will demand Congress to authorize billions to enforce.

US Border Patrol Budget, FY 1990-2021

While it may seem not only perverse but even a sort of vain consolation to try to excavate the intellectual origins of Trumpism by locating it in an intellectual genealogy–political scientists and theorists went wild in Trump 1, pointing to Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt as a through-line for the concepts of sovereignty. They found the fingerprints of the evil genius’ friend/enemy distinction to explain the angle Trump’s strategists took on global politics of the early twenty-first century as a New World Order; they seemed poised on cue to interpret Trump’s vision (if it can be called that) of American Exceptionalism rather than pure egoism in Nazi theorists’ thumbing of their nose at international collaboration as a way of welding political power, the expansive ways he introduced pushing the frontiers of America beyond their sovereign limits, and indeed into space to the orbit of Mars, If some political scientists seek to identify Trump as a proponent of Schmittian ideals, seeking to establish a new geopolitical sense of Grossräumen of regional hegemons in a global order. To be sure, the Trump regime has gotten rid of norms, and indeed demonized the emptiness of norms of a liberal order. He seem draw on the fashioning of a new global map in its place, and in place of the laws and norms of nations, or any legal or scientific consensus. The exploration of Mars championed by aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin, who claims credit for having preserved government funding for Mars rovers, and of having convinced Musk of its importance–even if he questioned the seriousness of Trump’s interest in the mission, he hoped Musk might redirect attention to the human exploration of the red planet based on the preposterous premise “nations grow when they challenge themselves and stagnate when they do not” out of Schmitt’s world.

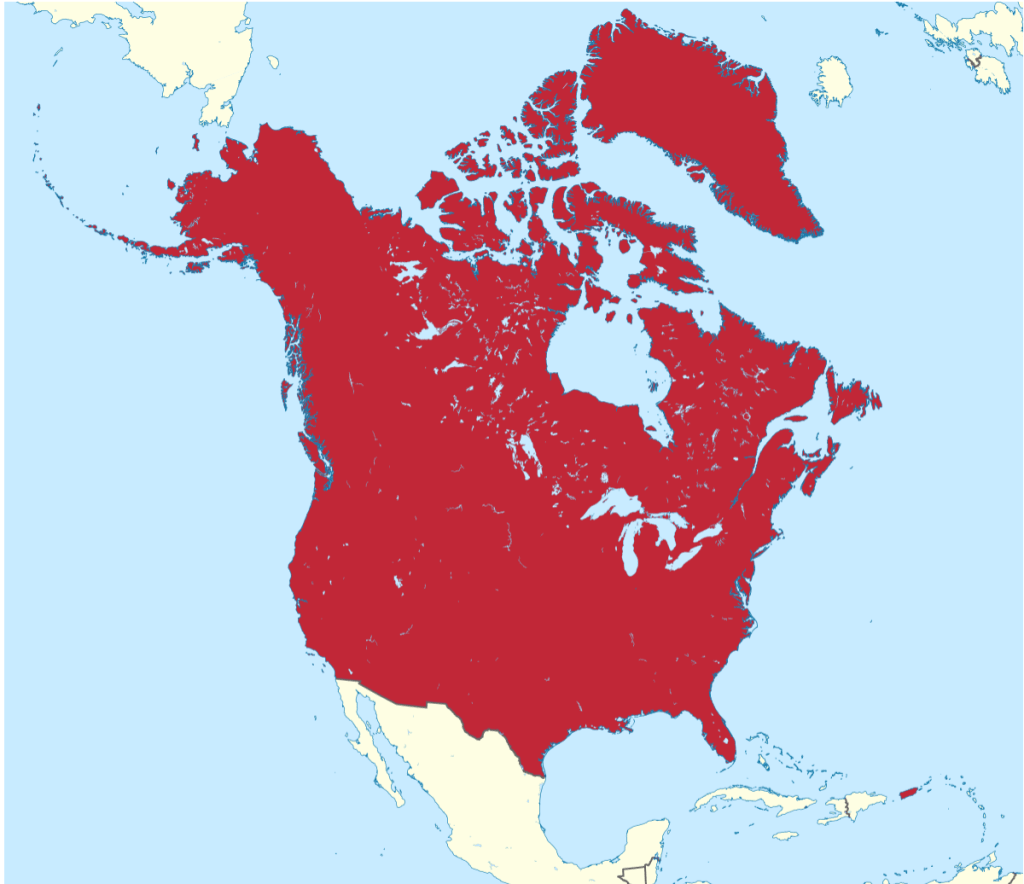

Yet as much as being a real advocate of hegemony, Trump seems to deny the institutions of global consensus or international order as a tool to take advantage of the United States, appealing to a sense of resentment more than humanity, justice, and progress but an order whose Great Spaces exist for wealth, security, and for untold commercial gain–a global order of economic resentment, perhaps, more than illiberal democracy, and resentment so ready to be remedied to be prepared to swap out laws with a recognition of resentment. Trump offer a possibility to envision global politics in an age after hegemony, where markets make up for political power or domination, and tariffs form the notion of nations: if Carl Schmitt envisioned global politics as defined by securing of Grossraum, Great Space, and the world’s future as lying in a constellation of Grossräume, more than spheres of influence, homogeneously organized around an empire or regional hegemony, the authority of the sphere of influence in the Trump world of a “Gulf of America,” remapping of Canada as a fifty-first state, and annexing of Greenland as a frontier in the northern Atlantic and Arctic, is imagined as “a friendly geographic expansion” to solve a global puzzle Trump as if there had been no groundwork for global alliances of democracies: the annexing of Greenland offers the unilateral leverage Trump needs by transforming the United States to a nation that borders Russia, and might gain the concessions for peace in Ukraine, appease Russian expansion,–

Greater United States/Nagihuin, Wikipedia

–perhaps by manipulating a vote for a shift in sovereignty from Denmark to America, weakening Canada’s economy sufficiently by escalating tariffs to force that nation into a Greater United States.

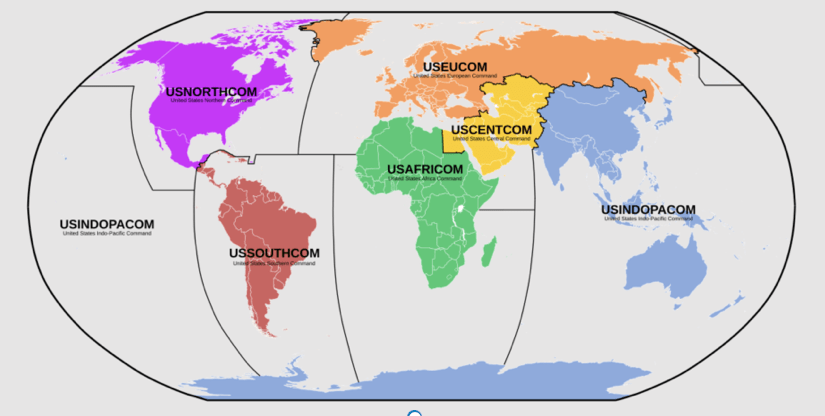

The recent hope to expand the nation by incorporating a comprehensive “Northern Command”–wrestling Greenland out of the European Union by incorporating it to an American sphere of influence that seems to suggest the new borders of truly reordered world. USNORTHCOM already lies at the coasts of Greenland’s shores, and the project for an effective Golden Dome may in part lie in placing sensors not only in orbit, but within what are currently mapped as Greenland’s borders. “We need Greenland very badly . . . we need that for international security.” Just look at the new map . . .

United States Unified Command Map

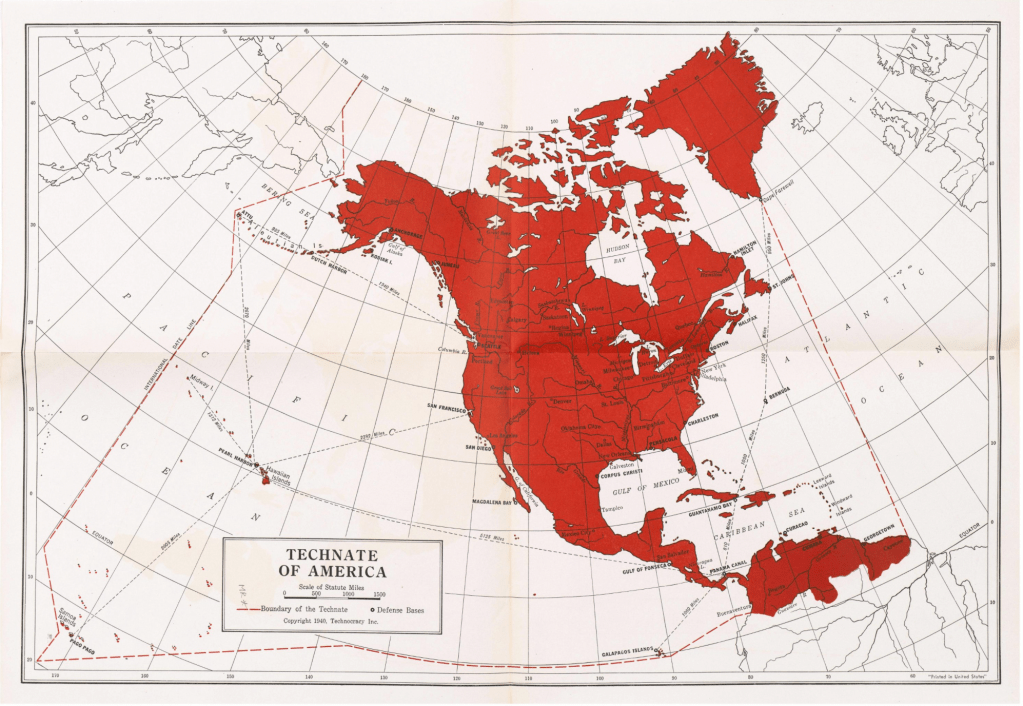

It is hardly a surprise to see a precursor or precedent in the entirely fictional North American Technate. The power of this fictional precedent in the current designs for an actual geopolitical project is terrifyingly similar to the image of a Greater United States–and possession or annexation of offshore waters of a newly calculated Extended Continental Shelf. The new bordering of a global map are hardly globalist, but refuse globalization, replacing that fear world with robust plans for a project of global isolationism, puffed up as if they were really a rational future path forward.

Unlike many National Socialists, however, the Freidrich Ratzel shaped many ideas on geopolitics in a visit to the United States after the Civil War–where he arrived not as a natural scientist or student of geopolitics but amateur ethnographer for the Kölnische Zeitung. In expansive journeys to the new political space, he was intrigued by mapping the status of races in America, dedicated to exploring slavery in the American south, Mexico and Cuba, alternately enthralled by the “spacious thinking” [Weiträumiges Denken] of American politicians that seemed so foreign to Germany he saw embodied byFrederick Jackson Turner’s notion of the Frontier which seemed to cast the state as organism. For Ratzel, America’s westward expansion was less imperial than natural self-sacrifice for an “energetic” and “youthful” population. He felt technocratic, white elites confronted the ways “racial conflict” [Rassenkampf] impeded political development in the former confederacy, whose black subjects were “too difficult to integrate” in political society, even suspecting political needs mandated repatriating blacks to the West Indies, Central America, or Africa, questioning the whether legislative emancipation or enfranchisement might mask the low level of their intelligence or Mexican civilization; Ratzle wrote a Habilitation on problems integrating Chinese migrants to California, reminding us of the global origins of Nazi ideology.

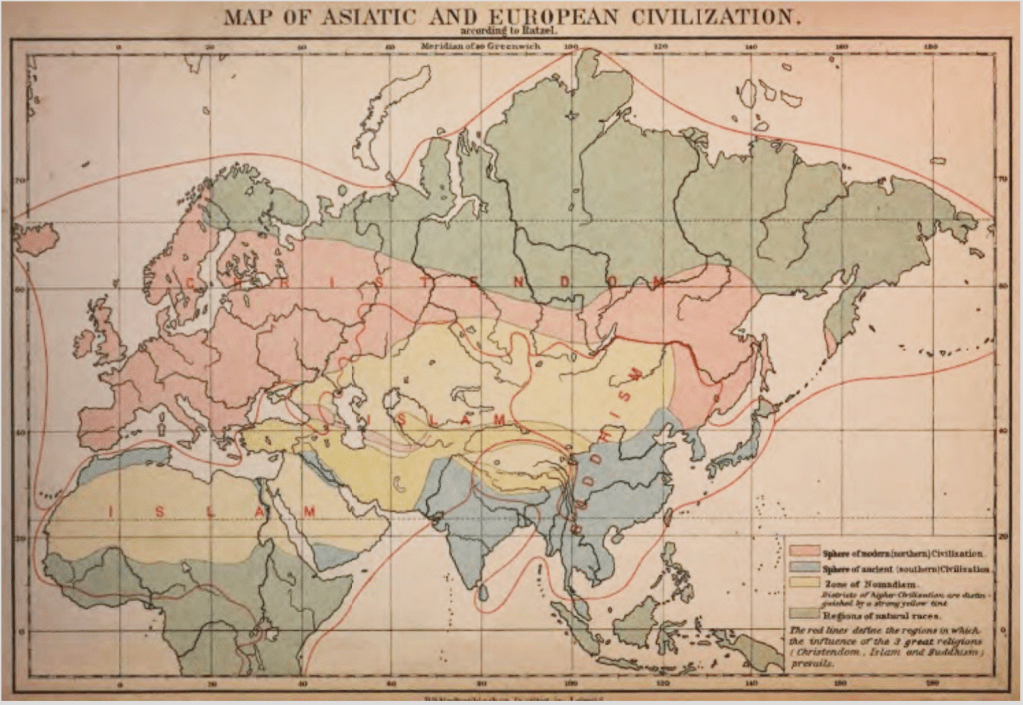

But the anthropogeography he believed the basis for all political geography was rooted in a global classification of political orders, using maps to define the diversity of human culture across axes of space and time to confront “the great problem of the classification of mankind,” in which maps documented permeable borders but also recorded deepest tensions among “the separated parts of humanity” defined the possibilities of the global projections for geographically modeling the possibilities of political territoriality.

Friedrich Ratzel, Anthropogeographie (Stuttgart, 1899) , v. II: “Classificatory Map of Humanity in Oecumene”

While Ratzel was, of course, thinking a bit about the ways the linguistic origins of place and law in a global context. The unsung evil twin of Prussian legal theorist jurist Carl Schmitt, whose political theology justified the Nazi regime’s ideology, Ratzel was the step-father of its political geography; his “organic state theory” offered a lens to justify the territorial organization of states, in rational manners, if, unlike Schmitt, his travels to the United States helped to develop his ideas of man and environment in the United States’ western states, and a meta-geography cast the boundaries of the United States in what Carl Sauer has called the “cultural hearths”–but developed his notions of divides of European and Asia Civilizations from his time in North America. Lebensraum was tied for Ratzel to the geomorphological notion of race, born in the United States, of all places, where the great “telluric force” offers a planetary law–a globalist thinking, indeed, that led him to adopt many notions of racial classification and difference that were developed in the United States, as James Q. Whitman so convincingly recently shown. But if the migration of American notions of racism to the multi-ethnic populations of central Europe is increasingly appreciated, the reiteration of notions of lebensraum across the Canadian frontier has been preserved in the technocratic image that survived across later generations.

Ratzel melded racialism with continental barriers. The very fierce that leads but one type of mint occurs in the Alpine meadows of the Carinthian mountains became the very logic by which one tribe of Pygmy in a region of the African jungle, each rooted in an ongoing “battle for annihilation (Vernichtungskampf),” offering an imperial anthropology of exploitation and extraction, that he was ready to project backwards to understand what had led Spanish early modern colonizers to adapt to the “tropical Lebensraum” of Latin America, the Caribbean and Philippines. The logic inherent in a Kamp um Raum or Struggle for Space that animated his view of world history. As an misanthropic geogapher, Ratzel was always talking in a sense about the modeling of the German state on either the religions or linguistic groups of the continent, if the German language suggested the cultural expansiveness of a nation and the resistance of the multiple if not infinite maps against which any map of the German nation, whose boundaries were notoriously fluid, might be stabilized and fixed–if the clear sense was the need of states to define their borders for survival, terms that Trump echoes eerily in asserting that a nation without borders will cease to be a nation, as it rather becomes only “a vast international territory between Canada and Mexico,” and Securing Our Borders mandated that after having “endured a large-scale invasion at an unprecedented level,” the unsecured border must be defended as “a nation without borders is not a nation” and without taking “complete operational control over the borders of the United States” it will not exist. The Technate was indeed not a nation, properly, but a heuristic silencing of national space, that expanded the idea of the nation beyond its borders against its enemies.

Terrifying words indeed, and almost a logical mise en abyme. While we identify the Ratzelian concept of Lebensraum with Germany today, it was born in America, if Lebensraum only appeared in the second edition of his Politsche Geographie der Vereinigten Staaten von America (1903) and earlier in his Anthropogeographie (1882). Ratzel began interest in mapping as a zoologist, more than political geographer, using the term to map zoological habitat, as much as political territory by slippery synonyms from Lebensphäre to Lebensreich to map a “realm of life.” He tacitly opposed vitality to the continual threat of biological extinction and a struggle for the finitude of natural resources that collapsed space and time and human and animal, however. Continents were cast as vessels of civilization locked in struggle with one another–evident in his acceptance of the extinction of indigenous peoples of Australia or North America as a consequence of a broader struggle of life-forms of a piece with his Darwin’s notion of natural selection as a “struggle for survival.” Ratzel help remap nations as organic entities in a science of political geography–

Asiatic and European Civilization

–as a transcendent view of the world clarified as relatively clearly color-coded blocks.

The iconic power the border wall may have faded from public language as an urgent creation for national survival that was conjured as a central fiction and figure in 2015. But what Ratzel saw as the borders of continents were always central to nation-building. And the concept of America’s borders had expanded in surprising ways in the maps of sovereignty Trump promoted and purveyed by the time of the 2025 inaugural this blogger seeks to subject to detailed examination–faced by the rather terrifying notion of anyone advocating the emergence of a new maxi-nation would be a disruption actually be good for anyone, rather than only setting off alarms worldwide.

The energy that was dedicated to the Border Wall seems subsumed in Trump’s political rhetoric by new geographic ambitions, in almost uncanny ways, as if a new map has provided the paradigm for envisioning and indeed representing the nation. Trump’s recent bombastic inaugural address may seem fantasist, but became a basis for the President of a country bordering the Gulf of Mexico to inform the world that, henceforth, they belonged to a different reality: declaring the “area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico has long been an integral asset to our once burgeoning Nation and has remained an indelible part of America,” to fit a national program “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness”–code promoting an amnesiac relation to the past, in its evocation of an imperial past, rather than one of struggle–to recast not only American history, but urge the United States “once again consider itself a growing nation” whose growth “increases our wealth, expands our territory, . . . and carries our flag into new and beautiful horizons” as we “pursue our manifest destiny into the stars . . . to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars” as a new epoch of transcendental thought.

If Manifest Destiny was modulated in Muskian terms, the greatest applause line of the inaugural was a call to “act with courage, vigor, and the vitality of history’s greatest civilization . . . to lift it to new heights of victory and success” by extraterrestrial travel, combining the enthusiastic national goal of space travel with a trumpeting of evidence of a state of undefined borders. As much as going with his gut, the new icon of invincibility and of the engineering of the nation beyond the border wall was hardly impulsive, but based on zombie ideas long nourished by the Musk family as a lost opportunity of technocratic governance. If the border wall has fallen from the primary scope and logic of governance in Trump 2.0, after being resurrected as a wall against the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the continental barriers of Trump 2.0 were on display in the inaugural–and the new aspirations to reconfiguring North America in an era that is not about regional hegemony but an imperial vision of supremacy that knows no legal boundaries and respects no other states. The science fiction model of the Mars mission and praise of American technology and invention was tied to the metaphor of the reduction of all knowledge to a device that fits in one’s palm–the cel phone–as if the knowledge had been miraculously contracted to an infinitely condensable circuit, was not about human relationships, and had no reference to society, but was a project that depended on endurance, confidence, and daring that previous governments had failed to show.

“We will not be deterred” from a new project of sovereignty in the solar system, far beyond the orbital pathways about the planet, to a space piloted by AI. The urgency was recycled, but effectively countered a mounting global sense of insecurity that Trump exploited to become a credible political candidate, despite his unpopularity. Indeed, violating the status quo–or because of the unguarded ways in which they brazenly violate it–upending trade agreements that he drew up, as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) negotiated and signed during Trump’s first term; such alliances would be broken up to the greater imperial project of helping Musk colonize Mars with federal funding. “Manifest Destiny” was born to add messianic inevitability to plans to annex Texas and California in the mid-nineteenth century. If arguments of sovereignties were long plausible in Canada, the trumpeting of this new expansionism may lead Canadian voters to restrain their own sovereigntist impulses to protect their economy from the sovereigntist ideology below the border.

All were gained imperial inflection in the bold announcement of a unilateral declarations of expanding the continent–beyond annexing Texas but purchasing Alaska. As if to make up for the lack of any credible statement of global hegemony in a world that no longer is defined by spheres of influence, Trump’s plans for an enlarged western hemisphere under American dominance concealed the decline of a world power most of all by the outlandish goals of planetary colonization worthy of Isaac Asimov, as if space exploration provided the key to global peace–so argued the novelist–not by communications satellites but a future world of interplanetary travel, starting from the romance of a manned mission starting colonizing Mars–as if this recycled proposal might indeed render the nation obsolete.

The final Asimovian phrase caused Elon Musk to raise two fists in joy as it heralded the prospect of “launching American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars”–a SpaceX mission of raising a flag on Mars. Asimov himself, when asked for a single statement to include in an inaugural in 1988, advocated a call to address global problems from climate to the environment by cancelling military appropriations from the federal budget.

Trump’s new expansionist turn seemed the source of a newfound energy–not only to lay claims, as this blogger has hinted, to an augmented Sovereign Wealth Fund based on offshore underseas oil reserves, but an annexation of nations before the threat of huge economic tariffs, that might redefine pride in an American Empire. When Trump energetically exclaimed, “We’re going to be changing the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the “Gulf of America” with a finality of apparent defiance, he issued a preview of a desire to take over Canada, annex Greenland, reabsorb the Panama Canal, and redraw the Expanded Continental Shelf. The barrage of creative cartography was not only self indulgent–it followed a logic of “restoration” of truth by executive fiat, in ways that seem to render national borders and frontier irrelevant when it comes to declaring the largest body of water in North America the Gulf of America. And if it is not surprising that Trump took Mars as the applause line of his second inaugural–was this a way of redeeming our inner natures, even if we were going to deport all those undocumented refugees, by turning our higher natures to the star?

Jill Lepore has noted the cult-like status Haldeman had in Musk’s childhood, and eery continuities between the Trump proposals and a zombie blueprint that Musk may well offered Trump as he courted him in a charm offensive to land him in a new ambitions of government, the origins of this new image of governing seems so removed from the laws–and from a framework of legal precedent–that its old maps demand examination, to suggest the depths of reconfiguring the nation that we seem to be headed–in order to explore what is hardly uncharted territory, even if it seems like it. One has to wonder whether Musk had channeled his beloved grandfather Joshua Haldeman’s love of a post-national mapping of North America as an aspirational symbol of political power, as he hoped to burnish his credentials to fashion his identity as a “special government employee” able to engineer government, if lacking government experience. Did Haldeman’s blueprint provide something like a suspect if compelling proof to act as an adjutant to the expansive Unitary Executive? This would be an executive focussed on the expansion of the boundaries of the United States, but following rational precepts rather than laws or norms.

The sense of a retreat behind borders of safety were a central platform of Technocracy to resist an earlier wave of globalism that was arriving in the dark days of economic depression before World War II. It surely suggested the strategy of retreating behind borders at the same time as expanding the footprint of a national maps. The map makes a case for his governmental role, placed beside his proved skills of being able to purge the federal workforce, consolidate expenditures, and trim “excessive” waste–curtailing the very notion of government, as a technician did best. Trump’s “special government employee” seems ever so slyly to recuperate exactly the role of the technician that Joshua Haldeman had imagined, from Technocracy, Inc, as a notion of social engineering. And even if the Technocrats’ vision had effectively migrated, after around 1945, to science fiction, that was a domain that weirdly left Musk ready to lap up the rest. For in the sadly futuristic visions of Asimov and Heinlein of technocratic men, Musk unquestionably internalized many of its percepts, preserving his memories of Haldeman’s vivid slide shows of his own past hopes for a Technate of America–was it not almost a substrate for what Trump meant by Making America Great Again? Does the sort of cowering behind borders, and imagining the possibility of national self-sufficiency in an age of global war, born in convincing cartographic form circa 1941, offer a model for focussing on the Moon Shot and Mars Launch, at the same time as disengaging from global crises?

The Technate of America (1941)/Technocracy, Inc.

The weirdly modernist map of a North American Technate, an alteration of the Universal Transverse Mercator that was used in wartime for coordinating airplanes and land attacks, rejiggered from a deeply isolationist perspective, has recently made rounds on social media quite a bit, and in some of the speculation of American historians such as Jill Lepore–as well as many avid map fans on reddit! It has come back to haunt us all, in other words, as underlying the weird geopolitical aspirations of alleged strategic relevance to annex Canada, take Greenland, seize a large chunk of the Gulf of Mexico that can be called the Gulf of America for boosterism, and retake the Panama Canal.

Engineering a new world order was presented as an alternative to involvement in a war in Europe. The old hope of being able to redefine its boundary as an economic unity of autarkic ends, bound by a red dotted line connecting military stations to contain a region of self-sufficient energy resources, seems weirdly alive, as if it were not consigned to a past fantasy world, but weirdly undead. The sense of a regional dominance within clearly marked boundaries seems launched as a new template for the nation in Trump 2.0, as if it was cooked up out of nowhere, but is a goal that the first hundred days of Trump’s second presidency is advancing to stake, without any precedent.

Pingback: Appeals Court Blocks Trump's Wartime Law on Venezuelan Immigrants - Writ of Mandamus Lawyer in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut & Washington D.C.

Pingback: Judicial Review and Mandamus in California’s Fight Against Federal Immigration Overreach - Criminal Immigration Law Firm in New York, New Jersey

I think it speaks volumes that as Trump seeks to leave a global imprint he was denied in his first term, that he turned to a man like Musk, whose sense of global politics is so limited and skewed. This is a case of the inexpert leading the inexperienced, clamoring for authority with little priorities than their own self-aggrandizement.