The proliferation of maps tracking the diverted flight path of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 repeatedly re-enact an exercise of mapping the unknown: if the early proliferation of possible maps of its flight path matched the shock of its disappearance, the continued frenzy of the search for signs of the fate of the airplane and its 238 passengers, as if trying to help get our minds around the implausible nature of its disappearance on a rather routine commuter flight. The rapid proliferation of hypothetical maps of plausible diversions hang on the turning points in the trajectory of the vanished plane from its last point of contact and observation all seem to be seeking to explain what happen with something like the surety we expect from maps: in the absence of any information that is clear, we turn to the map as a way to ground what we know, and to try to find meaning in it.

But the multiplication of these maps almost seem to respond to a lack of real information, or conceal the absence of any clear leads as to what happened. For each map includes an abundance of bathymetric contour lines, shorelines of islands, point of take off and the place of the satellite had last contact with the flight are all included in these maps, which obscure the sadly open-ended nature of the tragic narrative that exists around it. While none presents the individual narratives of the passengers or pilots on the flight, by necessity, and may even represent the frustration of our remove from whatever happened on board the flight after it left the airport, the multiplication of news maps and digital reconstructions capture desperation at not knowing what sorts of events or potential diversions occurred.

At the same time, the underlying narratives of all accounts is often left unstated and go unexpressed: that of how the flight path of an airplane managed not to be tracked. The proliferation of news stories seem driven by the continued technological attempts to produce a comprehensive detailed account of what happened on the plan in its final moments–or of the location of potential wreckage –as we openly worry about the controlled nature of our international airspace, and the extent to which it can ever be fully mapped. The inflection of this story, which is in a sense the parallel story that has been driving the story of the search for a narrative to describe the tragic events of the flight that left 239 passengers in the flight and its crew missing and presumably dead. The assurances of international authorities on the International Investigation Team (ITT) that the search for fragments of the inexplicably vanished aircraft in the Indian Ocean will continue over a search area of nearly 50,000 square miles–aafer the perfunctory issuance of death certificates for all passengers by the Malaysian government–creates a puzzle about both our mapping abilities as tools of surveillance and effective control, and sustain a continued wish to compensate for such concerns by repeatedly illustrating the abilities to map, remap, and map again the area and the plane’s flight path, producing maps that might provide a narrative structure to events that seem dangerously incoherent. For the map offers uniquely reassuring coherence on an event whose narratives have literally gone out of control.

Existing maps largely proceed from reconstructions of plausibly altered itineraries the airplane may have taken after it veered dramatically off-course in the course of an otherwise routine flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing. The underlying questions to which they appear to respond is how technology and ramped up security could prevent us from losing another plane, and how we can, as Tony Tyler, head of the International Air Transport Association, Tony Tyler, calls for the need “track aircraft wherever they happen to be, even if they go outside normal traffic coverage . . . in the most effective way.” After the intentional closure of the transponder during the flight, the increased suspense of any air travel–and the anguish of the families with members on the Air Malaysia flight, increased attention has been directed to border control, as minimal information seems provided by attempts to map–or digitally reconstruct–the diverted flight.

The map of flight-paths is often combined with maps of search missions and sites of possible wreckage in news maps and online media, as if to condense the slight information we encounter in a single map. Chances of discovering or locating whatever is left of the lost plane–the ostensible goal of the search mission–seem remote, like a needle in a haystack, despite the lack of an appropriately marine metaphor. The insistent and repeated mapping of the Boeing 777’s flight path and its contact with ground control is not only an artifact of the news cycle; it is an incomplete narrative we keep on trying to resolve or find resolution for: the story of the interrupted flight path has left audiences world-wide wondering whether the storyline will ever be resolved, how the intervention in flight path was made that caused it to shift its planned itinerary, and why our apparently refined abilities of mapping can’t complete the narrative we all want to bring completion to. There is a commanding logic in matching the search area to the possible diversion of the plane’s in-flight trajectory, but everything is complicated by trying to balance a narrative of the flight’s tragically diverted course with the mute azure surface, without landmarks or points of orientation, of oceanic expanse over which jets travel on search missions and boats patrol.

In ways that have gripped viewers but also raise frustrating questions of how to best search international waters, as well as unfamiliar perspectives on mapped space, all eyes were for a time directed to the South Seas with an intensity that oddly echoed eighteenth-century speculators. For after we have watched a cycle of maps of the flight paths, we have found them substituted by the maps of the dangerous search conditions of the area, and the stories that they tell of the challenges of searching in the South Seas, at the same time as a fairly constant drumbeat of the maps of potentially sighted objects–things that can at least be mapped, unlike the plane itself–in the hope to locate something that might close the rather terrifying narrative of another potential diversion of a passenger jet’s flight path. (That fragment of the story–an entrance into the cockpit or pilot’s cabin; the diversion of the path of a preprogrammed flight–is so powerful to summon nightmarish scenarios, and to search for any sign of resolution.) That “other map” that has increasingly dominated news-shows and newspapers of potential fragments of the lost Boeing 777-200’s wreckage in the Southern Indian Ocean, Gulf of Thailand or even the Mediterranean has taken over, spinning the search mission into something like a cartographical myse en abyme, which lacks the possibility of clear resolution of perspective in mapping the shifting sites of searches that are super-imposed into maps of the flight path.

For fragments are repeatedly being reported in the ever-expanding and shifting search area for the tragic and still as of yet inexplicable disappearance of an airline with 239 passengers aboard: in ways that have driven comparisons to black holes into which the jet mysteriously disappeared have created an almost near-impossibility of locating what one thought were the most trackable of flight paths, if only given the broad area of the radius of 2,500 miles which the fuel tank of Flight 370 might have allowed it to have gone after its last contact with radar. The open seas that provided the only places to be less carefully tracked, as it left Malaysian for Thai airspace, seem a rare region removed from land-surveillance, as well, as we have since discovered, the sort of windswept area of fast-moving currents that have sufficiently flummoxed the densely concentrated and often multi-national surveillance systems that have mobilized around the area.

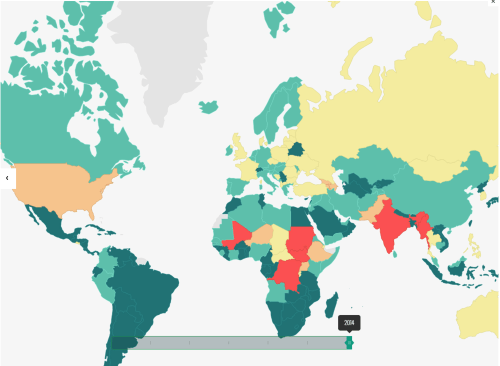

The mid-March findings that the airplane took a planned sharp turn westward, most likely programmed by someone inside the cockpit contributed grounds for fears of hijacking by someone on board, bolstered by the swerve of flight path toward the Strait of Malacca that the Royal Thai Air Force observed, traveling back out to the Indian Ocean, rather than its planned course to China, and the search has progressed along the lines that Flight 370 headed in another direction than was first believed, costing significant delays in time for the search for the missing plane, but not reducing the search area beyond 2.97 million square miles. But how does something like a plane fall out of contact with civilian radar or satellite? Where, simply put, could it go, and how did it get there? As the story has circulated in the major news outlets, a sort of popular response to the inability to map its course has surfaced or emerged. The disappearance of the American-made airplane has recently provoked the existence of something like—you guessed it—a Bermuda Triangle, that often evoked conceit of the 1970s, or provoked (in less responsible news outlets) the existence of a “greater force” that just gobbled it up, in ways that explain (in comparable ways) the sudden disappearance of aircraft from civilian radar monitors or satellite reception. The notion of a “Bermuda Triangle”-like theory matches the odd absence of clear territoriality over the open seas in the region from the Gulf of Thailand or Strait of Malacca to the Indian Ocean, whose rapidly expanding search area that has involved the Chinese, American, Australian, Malaysian, British, New Zealand, and Thai governments, and evoked potential dangers from Uighur separatists, as much as Al Qaeda. (Or might it be, as was recently suggested by a Canadian-based economist with ties to the petroleum industry, that the United States was involved in targeting MH370?)

The notion that no government is prepared or able to adequately chart the waters of the wild South Seas suggests an absence of governmental supervision that somehow links the plane to separatist groups–even if no one seems to dare to claim responsibility for diverting the flight. The difficulty in stopping the search starts not only from the tragic disappearance of a jet with some 260 people aboard. The compulsion evident in the maps of air traffic controllers to the sighting of debris seems almost to derive from the fact that something managed to evade the system of worldwide surveillance somehow managed to escape being tracked, despite its size–or, more probably, the fear that we are not being surveilled and mapped as well as we had all hoped. The latter not only opens the door to invite a further future opportunity for terrorist acts that we might all of course want to avoid, but lifts the veil on the surveillance industry itself. The images distributed by the Malaysian Prime Minister’s office, no doubt in response to how frustration made the government an early target for the inquiry, seemed to suggest an eery possibility of a middle-eastern connection, now doubt familiar to American ears–even though this expanded search area suggests little basis for such fears. How, a concern runs across the media, did it ever disappear from radar coverage and surveillance?

But the very vagueness of potential trajectories Based on the amount of fuel within the jet’s tanks, the possible position of the flight when it was last heard from satellite suggested only that it lay along one of the red arcs of potential diversion of the aircraft’s flight path from Kuala Lumpur in the 7 1/2 hours after its 12:41 take-off, tracing some 2.97 million square miles in which to conduct the search for the areas to which it was originally delimited and confined:

New York Times

New York Times

Although the area the arcs encompass approach the expanse of the continental United States, the arc to the Caspian Sea or Kazakhstan seem to have received far more initial attention: it would, one supposes, be confirmation of the tentacles of Al Qaeda rearing their head. The far smaller areas in which the plane had first been searched, defined by white rectangles, suggested in this map, made a week after the airplane had disappeared, as well as the difficulty of tracking what had been assumed to be so readily confined to the Gulf of Thailand, but which now has expanded to cover much of the South Seas. But the fact that even those flying the most up-to-date jets of American Navy surveillance like the P-8A Poseidon have been peering out of glass airplane windows and not looking at their electronic screens to spot the potentially downed craft, relying on the human eye to scan the open waters, and only spotting such objects as orange rope, white balls, or blue-green plastic reminds us of how much ocean-borne garbage might create distracting signs to frustrate the search. And the reports of a low-flying plane sighted March 8 near the Maldives might potentially refocus attention in other areas that might well be mapped.

New York Times

New York Times

It’s a bit shocking that in over three weeks, no sign of the airplane’s disappearance has been noted, despite numerous potential sightings that have in the end proved red herrings. The oddness of plotting an opening of an escape from surveillance and tracking that are the basis of the concept of modern airspace find reflections in the repeated maps of loss of contact with controllers, exit from tracking systems, and potential paths of flight, all concealing the absence of surety in being able to verify what happened to the unfortunate passengers on Malaysia Jet 370 more than the results of an ongoing inquiry with little sign of any clues in the transcript of exchanges between the flight and controllers for the seven and a half hours after it took off, and little indication of the expected tussle that would be associated with a diversion of flight paths. The potential sites of wreckage that have been found are something like the catalogue of a junkyard–including some 122 pieces of unknown floating objects in the Indian Ocean; seventy-eight foot debris off Australia’s coast; white balls, orange string or other junk–in ways that have led to an explosion of articles on potential sightings that seems without end, each announced as potentially “credible” as the last. So many potentially distracting objects that bear no demand for further scrutiny seem to exist that the Australian military took it upon themselves to include a list of those objects worthy of follow-up, including “debris, distress beacon, fire, flares, life jackets, life raft/dinghy, marker dye, mirror signals, movements, oil slick, person in water, smoke, wreckage.”

The demand for news maps suggest the shifting areas of the search and the aporia of inquiries that reinforce how difficult it is to believe that anything like an airplane would be so difficult to map. The Australian government assembled a colorful collage of spots already examined, indicating the intensity of their daily attempts, which have shifted as time progressed and new theories emerged:

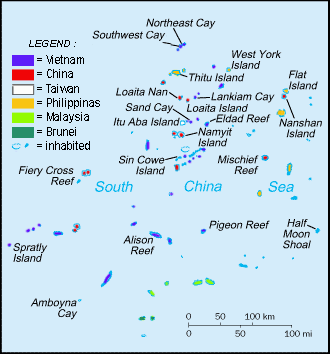

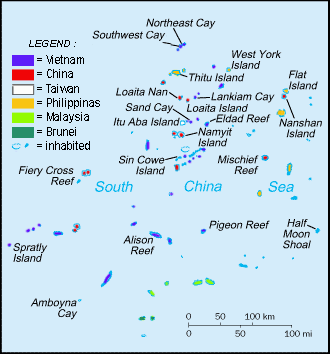

The Chinese government sought to provide ocular proof and exact coordinates of what looked like aircraft, 74 feet long and thirty feet wide, as if to reassert their claims to be monitoring the airspace by satellite, and staking claim to a region of particularly intensely disputed nautical boundaries–but so far finding little confirmation of the wreckage by boats:

Are we just discovering how much garbage is in the ocean? Or are we staking a claim to rights of sovereignty over maritime lanes, when maritime sovereignty still seems particularly difficult to define–raising questions of what sort of waters the craft may have been lost in, and whose right it is to retrieve whatever of the plane is left, but also pushing the search out to international waters, to avoid fraught questions of contested maritime sovereignty. The oddly international complexion of the search parties that have been engaged so far has all too often muted the deeper salient question of the complex contestation of conflicting lines of maritime jurisdiction in the very region of the seas over which the plane flew. (While few would want to suggest that the search has progressed in reaction to disagreements about jurisdiction, the difficulty of mapping jurisdiction in these waters has received far less press coverage than one might expect.)

In a field of disputes of maritime boundary lines, the search for the place is filtered through the actually contested sovereignty on multiple fronts, in ways that greatly complicate questions of responsibility for searching for the aircraft and its presumably dead passengers:

Indeed, the territorial complexion of many of the uninhabited islands of the South Seas resembles the random bright coloration of the multiple islands of medieval and early modern isolari, or books of islands, even if the colors are no meant to denote sovereign claims:

The larger picture is even, of course, both a bit more complex, and carries deep conflicts of how one can best understand maritime bounds, in ways that raise but a corner on the difficulties of resolving maritime boundary lines:

For most Americans, of course, oblivious to contrasting claims of sovereignty over water in a globalized world, and amused by the idea of contesting the sovereignty of maps, the questions might turn around the simpler incredulity at what has happened to our satellites or systems of radar. The amount of ink spilled over the absence of indications of a major airline’s flightpath leaves viewers aghast at not being able to interpret the map that results. The pleasure that commentators on ‘The Ed Show’ or ‘Bill O’Reilly’ take in evoking and imitating authoritative maps that show potential arcs of air travel provide a scary shock-tactic of disorienting observers to an over-observed world, and suggests the discomfort not only at the potential for future skyjackings or dangers of flying aboard airplanes–but that we’re just not being watched as well as we all wanted to be, as if that was what we wanted. Or is it that the mapping of the results of post-9/11 surveillance have let us lapse, reassured, into a false sense that we need not worry about the dangers of the diversions of commercial flights, or that all is indeed under control? Yet the hunt has now turned to the southern Indian Ocean, based on scattered new evidence of active flight diversion, after being centered in the Gulf of Thailand or South China Sea, with concern arising from the fact that the batteries on flight data and voice recorders–the main hope of finding the plane’s location–are due to die, and with them much potential evidence of what transpired in the cockpit, as pings emitted to facilitate their geolocation are due to die, after which the hopes to find evidence of what occurred would be drastically reduced.

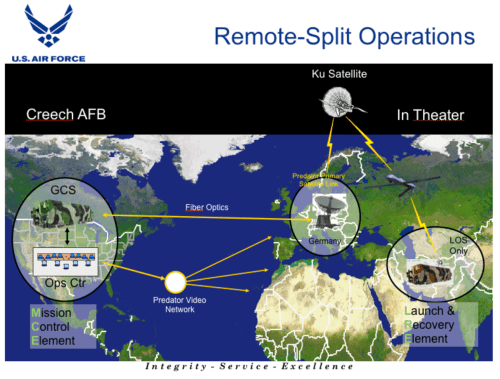

The search for the information is being collected in the need to affirm the continued safety of airspace, not to mention confidence in the air travel industry. Does it also serve to conceal the huge costs that the US government is ready to spend on the search, already having allocated 2.5 million for the participation of US ships and aircraft to this mission, presumably in the hopes to find clues to the disruption of monitored airspace. (The flight of an search of the average high-tech surveillance navy jet of the sort equipped with the requisite surveillance cameras lasts two hours, deploying the most cutting edge example of surveillance of the “sea state”: the theater for remapping the waters by planes such as the P-8A Poseidon suggests a rehearsal of the gamut of equipment that the Navy has assembled and huge costs to use must be balanced with the eagerness of being able to deploy our latest surveillance toys.)

(from The New York Times)

(from The New York Times)

The frames of geographic reference somehow seem part of the dramatic narratives spun about the disappeared plane, whose possible paths not only inspire limited confidence in the accurate measurements or tracking capacities but oddly orient viewers to the South Seas from a strikingly new orientation on landmasses and marine space, in which the dramatically open areas frame the aerial search along a diverted flight path far from land, in an area that is moreover swept by winds that often exceed 100 miles per hour, and rough seas:

New York Times

New York Times

The deployment of all this technology to map the region by weather charts or debris-sightings seem designed to bolster confidence that this area, if blocked by cloud cover and rain and tremendously powerful waves, and deep waters, is still being mapped with relative accuracy. Yet what is one to make of the mapping of potential sightings? What significance does their clustering in the Indian Ocean mean save the intensity of searchlights turned to that direction, and the new horizon of expectations that results–even if the idea that pings from the airline’s data system, ACARS, dating from the period of four to five hours after the last transponder signal, and transmitted to satellites, indicate its arrival in the Indian ocean. But why map potential sightings if they are not confirmed, except to try to restore some confidence in a search that might be akin to searching for sightings of Elvis or Christ? In the meantime, the proliferation of alternative theories continue, from the plane being attacked by extraterrestrials, captured by folks who’ve shrouded it in an “invisibility cloak” or the locally generated theory that the disappearance of the plane is part of a an ambitious life-insurance scam, and not a terrorist plot–floated by Malaysian police chief Khalid Abu Bakar. Over the month since the airplane’s disappearance, the biggest winner has no doubt been CNN, whose 24-7 coverage has stoked continued interest in the story; CNN President Jeff Zucker boasted how the new ratings showing reveal “a record-setting month for CNN’s digital platforms, including record-high page views, video streams and mobile traffic,” as if he was addressing shareholders, as it continued to describe and map objects floating in the Indian Ocean, without any sense of whether they were related in any way to the flight–so long as they were located along “possible flight paths.” Is the technology of mapping a legitimation here for the absence of any actual detection of the flight path?

New York Times; source Australian Maritime Safety Authority

New York Times; source Australian Maritime Safety Authority

It’s hard to follow the logic of those who are organizing the Australian search teams, even thought the New York Times does its best to keep us in touch with the latest, but the recent relocation of the search by some 700 miles to the northeast suggest the hunt is a grab-bag of guesswork, and reveals the intense feelings of desperation at the narrative spinning out of control.

New York Times; source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

New York Times; source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

But to generate more information about the “unfolding story” of what CNN has continued to call the “airline mystery,” given the fact that no resolution of this mystery is in sight, and no indications that the plane crashed have emerged, nothing does the trick like a map to link the event to a number of alternate narratives and abstractions.

And as it has emerged after almost three months that the unending search is the most costliest episode of recovery of a jet in human history, the devotion of such emergency apparatuses to locating a lost jet must be assessed: at the cost of millions of dollars per day, and over three and a half million dollars just to deploy an underwater detector of potential pings over the past weekend, it might be time to return attention to what is the end of the search, save seeking closure on a traumatic disruption of any illusion of totalsurveillance of airways such as that which the United States government wants desperately to be able to sustain?

What else occasioned the repeated search for the ruins of the jet without any sense of limits of cost, and indeed the devotion of a recently developed technology of surveillance to the detection of potential signs of the lost plane and its passengers? At the same time, the rescue mission seems a sort of dress-rehearsal for surveillance of submarines on the high seas, the narrative of locating fragments of wreckage of the plane’s fuselage or wings fits into a sense we need to find closure in a sense that something happened while we all thought we were being watched: this notion that the incident of Malaysia Airlines 370 suddenly disrupted and shattered that sense of an achieved limited peace, even in a time of ongoing contained military engagement in several theaters of the world. It is hard to get used to the fact that we are not, and cannot be, safe in air travel. (But at least, perhaps, we have generated these detailed maps, which seem to be reassuring of a sense of monitoring an unfolding story, even if it is one that seems to have not gone very far after all.)

The sense that we’re somehow being less well-watched than we once were seems to have driven the constant stream of news stories—unconscionably, never edited or diminished on airline flights, but almost increased in an attempt to keep passengers more relaxed and on their toes, the jet has increased critical thinking to the extent that it has provoked calls for the re-introduction of “reliable psychics” (in a return to the Nancy Reagan White House). Where the plane went is less the concern of these maps, it seems, than the fact that draw as many maps as we want, not much turns up on them. The courses of potential flight paths after the pilots lost contact with the airport in Malaysia from which they first took off on that tragic day seems less directed to the protection of our own frontiers—or even airlines—than the notion that we cannot map a map of that path, even with all our satellite coverage and technologies that we’ve devoted, in the wake of 9/11, to monitoring maps of all movements along flight paths across the inhabited world. One problem may be that 9/11 opened a narrative, or saw one forced on us, so haunting that we don’t know how to bring to an end, or cannot see an end of, so deeply unsettling is it all.