In the year 2025, a seven year old girl looks up at stars against the “deep, black” night-time sky, remembering that her stepmother as a child could once not see their “cool, pale, glinting light.“ Octavia Butler sets the scene for her cautionary tale, Parable of the Sower (1993), a novel which glosses the spiritual journey of the believer by cautioning against the indiscriminate sewing of seeds in infertile ground. The abundance of light in this possible world is an increasing reality. The girls’s stepmother used two words–“‘city lights‘”–to come to terms with the radical changes of nocturnal luminescence wrought: stars grew so feint in the night sky they lost visibility in her own memory. “‘Lights, progress, growth, all those things we’re too hot and too poor to bother with anymore,’” is all she was able to explain, in a post-apocalyptic tenor increasingly haunting today’s world, as the absence of darkness seems to have rendered starlight invisible in most of an over-illuminated earth.

The memory, and public remembering of an era of over-illumination haunted many works of the era with good reason, as the world of darkness has receded into the past. Novelist Russell Hoban imagined the absence of all government in a post-cataclysmic world drowned in darkness in Riddley Walker (1980), set in 2437 O.C. (Our Count, dating from an atomic blast) but haunted by fragments of the scientific language that are shard-like memories of a world lost to “counting cleverness,” which by “straining all the time with counting” eliminated of night–“‘What good is nite its only dark time it aint no good for nothing only them as want to sly and sneak and take our party a way'”–who “los out of membement who nite wer” as “they jus want day time all the time.” Echoing current environmental concern for the ozone hole, Riddley bemoans the “harms what done in poisoning the lan or when they made a goal in what they callout the O Zoan . . . you can’t see it but its there its holding in the air we brave.” The difficulty of remembering or registering the scale of global loss, and the possibility of an absence of terms to ever know the geography of stellar visibility or dark. If the reparation of “memberment” tries to keep together a world where all government is reduced to the performance of Punch & Judy puppet shows, the elimination of night is cast as a precursor to atomic apocalypse.

Are we in the midst of a current era of the lack of remembering an era that not so over-illuminated by artificial gas or electric light? The apocalyptic nature of a loss of the darkness of the night is increasingly upon us, and long before the year 4347 when Riddley Walker appears set. For the many reliant on round-the-clock work, any border between day and night is increasingly obscured. All-night work across the world have fashioned glowing landscapes of increasingly illuminated night skies, over inhabited spaces in over-illuminated lands may redefine an uncanny materiality of maps for the new millennium, evident in composite satellite images of an electrically illuminated world.

Nasa Earth Observatory/Composite Image of the Night from the Godard Space Flight Center

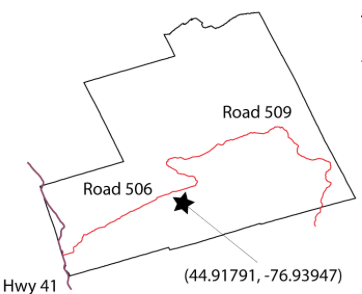

The notion of a “star-gazing station” that pops up along the highway may seem an improbability today. But driving an hour and a half north from Toronto, just north of Napanee, one passes a Dark Sky Viewing Area, that offers the chance for volunteer-led star-gazing, where knowledge about viewing night skies are eagerly passed down, as if out of Fahrenheit 451, offering opportunities for amateur astronomical observation of geminoid meteor showers at the “most southerly dark sky site in Ontario,” where increased stellar visibility confirms that one has moved sufficiently away from the hyper-luminescent United States to “natural brightness” to view the Milky Way in all its glory. The designation of “natural brightness”–or darkness–suggests a growing need to reckon with the geographical limits of night-time illumination. North Frontenac, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada assures, offers surroundings suitably dark in fifteen km in all directions to be designated a “Dark Sky Preserve Status” for viewing night-time skies as they once looked. The Star Gazing Pad invites all with telescopes in what seems a throwback to the popular astronomical observations of Victorian England. But it reflects growing anxieties and fears of the unprecedented skyglow and the augmented illumination of night time skies, where viewing stations are removed from major population centers. Astronomical observation in “dark sky viewing areas” exist outside of cities, near national parks, offering the possibility of respite from over illuminated skies.

Lennox & Addington County Dark Sky Viewing Area

Lennox & Addington County Dark Sky Viewing Area

Driving north from the border today, one arrives on the 401 in “dark sky country,” as if a definitive passing of the border, north of Kingston and Lake Ontario, removed from the nocturnal glow of city lights, which promises to provide the “night sky experience very similar to what was available more than 100 years ago,” promising visitors the chance to “witness–perhaps for the first time [in their lives]–how the night sky is meant to be seen.”

North Frontenac Dark Sky Preserve

Again, the question of the geographical boundaries of “natural brightness” and “natural light” are called into question by sites of such “Dark Sky Viewing Stations,” which have grown rapidly in Canada as preserves to “save the stars from light pollution.” The United States was the foremost model for Butler’s cautionary tale of a post-apocalyptic future, when stellar visibility had only just returned, but only did after the decline of a world in which increasing artificial luminosity had long removed the stars from increasing portions of mankind.

The vignette helped situate readers in a time just after a global collapse, where villages and cities are walled from roving gangs of drug-crazed marauders, and any semblance of security or infrastructure is gone from memory, and has faded into a past that few save the old can recall. Lauren protests to her stepmother “there are city lights now” which don’t “hide the stars,” but the older woman is only able to shake her head in response, trying to summon earlier skyscape, and describe the changes that set the scene for the dystopia they now inhabit: “There aren’t anywhere near as many as there were. Kids have no idea what a blaze of lights cities used to be–and not long ago.” Lauren tries to recuperate an even earlier sill of reading the stars by an astronomy book that once belonged to her grandmother that allows her to decipher constellations she is now able to trace, and are newly visible in the night-time sky, using its maps as the sole means to be able to glimpse the stellar order seen in the night-time skies of bygone eras. Gas lighting was a memory of the past.

Henry David Thoreau pegged the confusion of night and day to the railroad’s expansion in mid-nineteenth century America, and to the expansion of the railroad outside of Concord. Amidst the spread of electricity, even in the unfrequented woods on the confines of town, traveling in th “electrifying atmosphere” “at some brilliant station-house in town or city,” Thoreau described the passage of trains as a new environment in their train of clouds and piercing whistle and defiant snort, acting as a giant plow amidst the countryside, registering the surprise with which even “in the darkest night dart these bright saloons without the knowledge of their inhabitants” as new environments. If this pollutes our language as “to do things ‘railroad fashion’ is now the byword,” the energetic coursing of the trains pollute his own senses not only by introducing light to the dark night where he is at peace: only after the train departs does he hear again the calls of whip-poor wills, hooting or screeching of owls, crying geese, or croaks of aldermanic bullfrogs of Walden, as if reacquainting himself with a natural sensorium of a living evening habitat that the train obscured. They return only after the retreat of any automated “path to the civilized world.” Far from the gas lighting that Thoreau had created a residence with “no path to the civilized world” in Walden Pond, even if it was with such a “deficiency of domestic sounds” that “an old-fashioned man would have lost his sensors or died of ennui” at the relative silence save squirrels on his roof, blue jays screeching, or a rabid or woodchuck beneath the house, finding privacy in a solitary life on a few square miles of forest, reclaimed from Nature, with “my own sun and moon and stars,” finding that even rare guests from the village “soon retreated, usually with light baskets [flashlights], and left ‘the world to darkness and to me,'” in an ideal of no light pollution that seems to have rapidly receded ever far away in time.

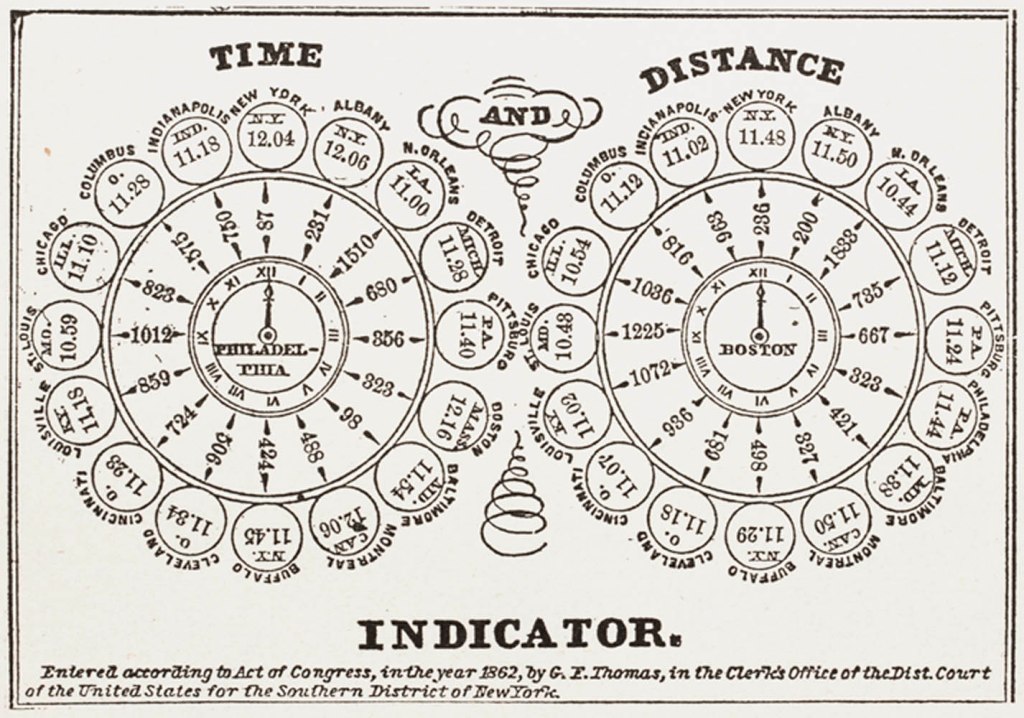

The night-time illumination of regions was tied to the introduction of the train. An animal of artificial invention, the train was a mechanical horse, snorting and creating a new environment of nature. Running across the countryside as a “fire-steed that flies all over the country,” a “cloud-compeller” that remakes its own habitat, stopping at “some brilliant station-house in town or city,” concealing the sun and leaving his own bucolic home cast into shade in its progress and he was awakened by its “defiant snort” in the middle of the night, erasing the division of day and night as it “penetrates my woods summer and winter. The progress of the train was, Thoreau suggested, to be weighted and considered a danger for the distancing of the world from nature, more than afford a support for civilization in the ability it offered to carry goods from all over the world to new locations, and provide odors carried with goods from “foreign parts, of coral reefs, and Indian oceans, and tropical climes, and the extent of the globe,” an effective precursor to the smooth surface of the transit of goods and open markets we tie to globalization. Concerned that there was “something electrifying in the atmosphere” of the train depot, where men “talk and think faster,” Thoreau invited readers to balance the improvements in punctuality the train provides even to farmers and the new compass lines it create perhaps obscure the path of fate in the air “full of invisible bolts,” as the individual is tethered to the relations of time and distance the train instilled.

The rise of Railway Time by Greenwich Mean Time helped illuminate the landscape have accelerated to the premium on unelectrified unlit spaces of the present. In ways that give a new sense to “dark data,” techniques for mapping of the absence of light from an increasing share of the world suggest a new understanding of “place” that commands attention in multiple ways. The Bay Area where I live can already be seen from the sky from the International Space Station, as photographed by astronaut Randy Bresnick photographed it in one of his final trips about the planet, that bear shocking witness to the expanse of populated lands that illuminate the growth of streetlights in the Bay Area, where intense luminosity stretches from San Jose to the Carquinez Bridge:

Randy Bresnick/@AstroKomrade

Randy Bresnick/@AstroKomrade

The experience of the extreme intensity of urban blazing is echoed in the quite timely appearance of an atlas of night-time space. The use of satellite maps to chart the extent to which artificial light has come to compromise the night-time sky over the past fifteen years. For it reveals the global scale at which the growing impact of light pollution on the diminished darkness of the night-time sky not only around once sacred areas, like Stonehenge, but stands to change our sensitivity to the perception of starlight, and experience of a non-illuminated world. At one time, the definition of astrological constellations provided a basis to organize time, space, and prognostication, they offered natural guideposts for maritime navigation–as the girl in Parable of the Sower seems to suspect, even as she struggles with the absence of many clear keys for their interpretation. If Butler suggested the dark future of no stars in an alternate world of the future sometime shortly before 2024, by which time the dark sky has returned, we see little point of turning back in the maps of the over-illuminated world presented in the first-ever global atlas of light pollution atlas.

The atlas suggests we won’t so easily return to an unlit world–or at least won’t return save after a similar apocalyptic massive destruction of the over-industrialized world. The recession of stellar visibility is only beginning to be fully mapped in full, but the ever-narrowing window of night-time perception of stellar visibility seems quite timely. The global spread of man-made light pollution is the direct consequence of living in what historian Mathew Beaumont first described as “post-circadian capitalism” back in 2005– a condition where work-time is no longer governed by a clock, or biological rhythms of sleep, but both flexible employment and 24-7 economies have effectively expanded the working day to a continuous job, often enabled by continuous illumination. If Beaumont, following Jonathan Crary, has seen the sleep-deprived working worlds of the globalized world that denies the value of rest–or allows one to deny it–the attempt to process the global absence of darkness demands to be grasped as evocatively as Butler began. And one is pusehd to do so by a recent collection of the diminished global levels of starlight and stellar visibility, which invites us to try to survey what a sky without stars would be.

Continue reading