Emigration of Italians alone did not “bring” pizza to America, so much as the Italian-American presence helped to diffuse a new range of pizza toppings, and new styles of pizza making, that grafted onto markets of food distribution and preparation that were soo to globalize. The geographic outmigration of Italians was large, but the inheritance of the pizza as we know it globally grew by grafting the food as a commodity onto different and unknown networks of food production and distribution, that encouraged a hybridization of cheeses–and a base of “low-moisture” mozzarella, often with additions of copious vegetable fat, that collectively transformed the meaning of the food from the 1950s and 1960s. In my life, the nature of the slices sold to kids along the east coast by the 1970s, and the major shift, after 2010, if resting on the dominance of independent pizzerie in coastal communities, metamorphosed as it grew national, as global chains injected a momentum for global expansion that cannot be described by the imperial metaphor of conquest, boosted by a parallel growth of frozen pizzas from 2009 that was soon global in scale,–promoted in no part by online ordering, but matched by the global markets for food.

The “pizza” was not robbed from a locality per se, but reinvented in a new one, to reach the world refracted through an American prism of food technologies, cheese processing, and caloric expansion, that made pizza one of the most expansive ingredients in global consumption of calories worldwide. And pizza perhaps became a popular part of the diet as even with occasional overeating, and caloric indulgence, the consumption of pizza by otherwise healthy young men showed them maintaining a balanced range of nutrients in their bloodstream not loosing metabolic control, even in an excess of consuming over 3— kcal–in one and a half large pizzas at all-you-can-eat events. If food scarcity brought the expansion of the satisfaction that one and a half large pies might bring, by the twenty-first century, the globalization of pizza distanced the pie from its ingredients to a global market removed from Naples–

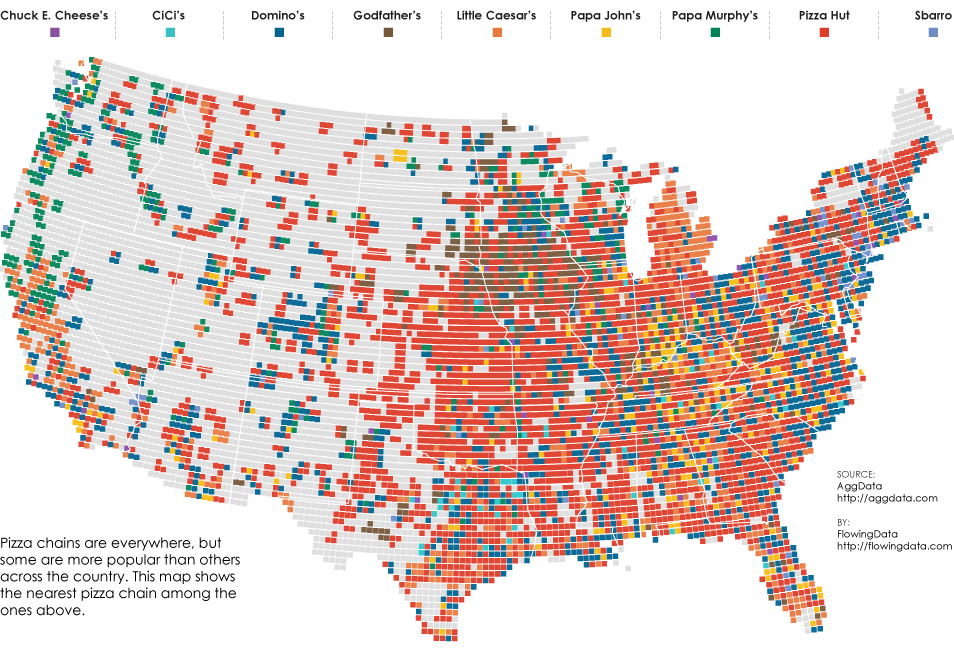

–suggests a deracination of the pizza’s sourcing from an individual countryside or landscape: the addition of smoked beef sausage “pepperoni” is a staple of Italian-American pizza has been traced to a German tradition of sausage making, perhaps rooted in the midwest, but entered the canon of sliced pizza across the United States’ east coast, despite its unfamiliarity in Naples. More than transatlantic migration, the global circulation of pizza in the current “age of chaos” of pizza-making takes its spin from proliferating patenting of processed cheeses, engineered for stretchiness and pull, fueling the near-ubiquity of global pizza consumption, that the art of pizza demands to be re-contextualized, reframed and recognized as a need for culinary centering amidst pressures of globalization. More than outmigration of deracinated Italians, the process of pizza-making has become deracinated as a huge profit motive expanded the global spread of frictionless delivery of frozen pizzas, distanced from craft, feed more per capita in Scandinavia and reach “breakout markets” in Russia by quadcopter pizza delivery service featuring drones by 2014 and in China over a thousand Pizza Huts by 2019, as Papa John’s and Domino’s franchises expand.

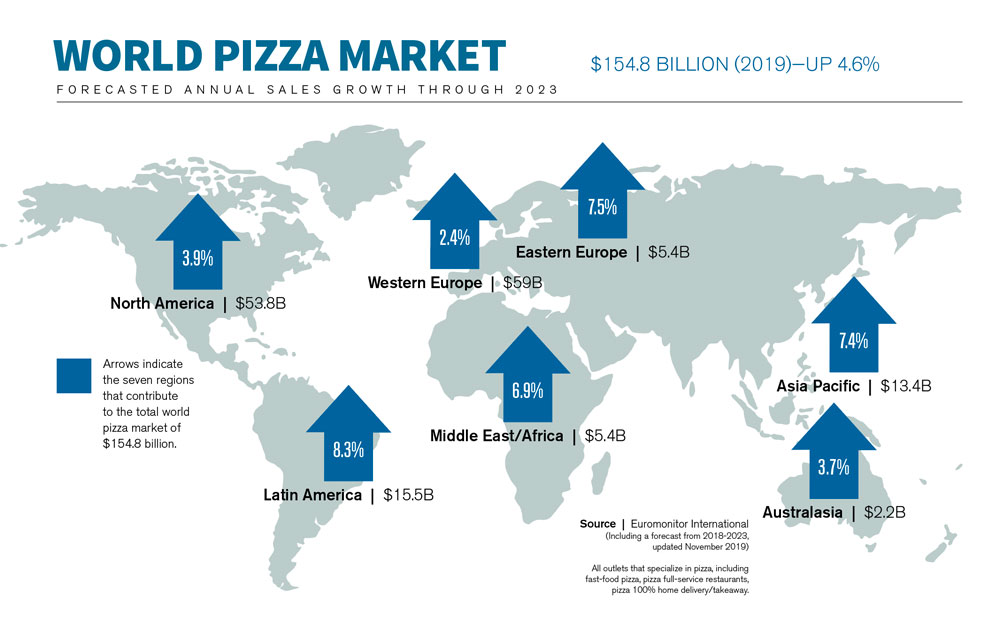

The global scale of pizza markets produces regular forecasts of global futures, charted in gross consumption of billions of dollars, no doubt boosted by the pandemic from the projections of 2019, but pointing to increased eagerness of eating pizza, by now considered the world’s comfort food.

Pizza Market Report, 2018/Pizza Power Report, 2019

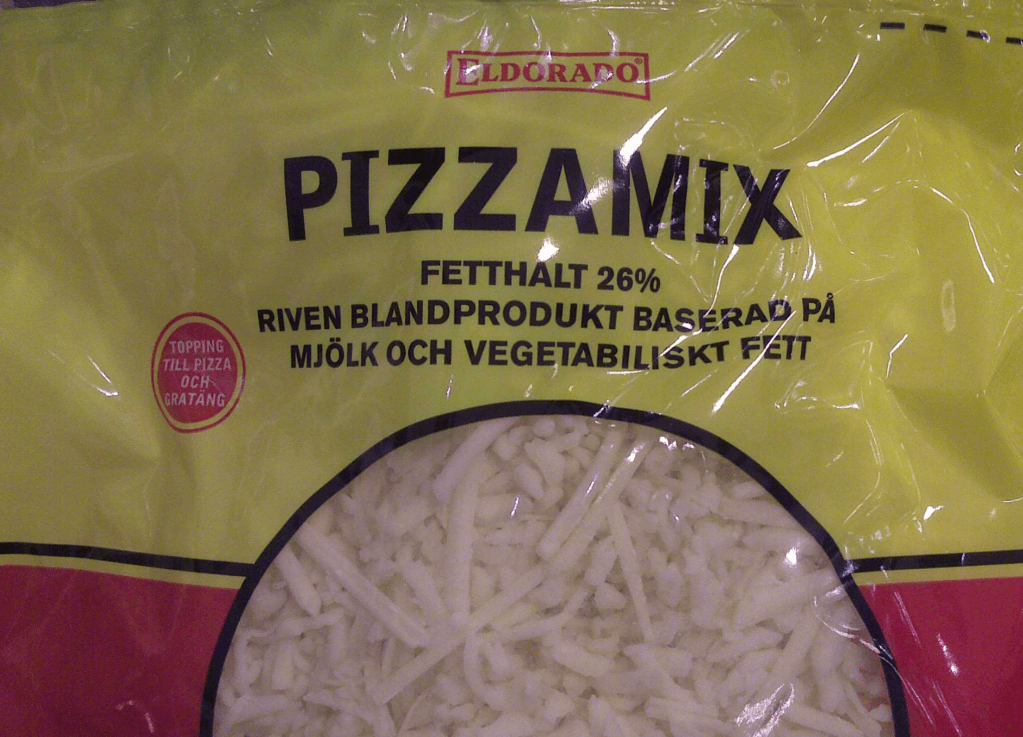

Is such smooth delivery of “pizza” for a global market even able to be considered the same food? One would do well to excavate the origins for the provision of “Pizza Mix” in Scandinavia from milk and vegetable fat to the metamorphosis of pizza with food distribution networks and to-go delivery in the metamorphosis of the pizza as a meal for a mobile on the road market in the United States, and indeed as a support to compensate for stresses of globalization in the past: the world indeed seems covered by the pull and stretch of streaming threads of vegetable oil coated processed cheese.

The introduction of oil may accelerate the global promise of the possibility of a truly frictionless delivery to all, a global spread assuring the ease of consumption of what is now a quasi-meal, conceals a tension between the local preparation of pizza on industrial scale, that still promises to deliver “fresh-baked.” Demand for pizza production in Italy has grown to such unprecedented scale to necessitate fabricating buffalo mozzarella on industrialized scale for five million pizza baked daily, many for discriminating tastes, of an estimated 1.6 billion consumed annually.

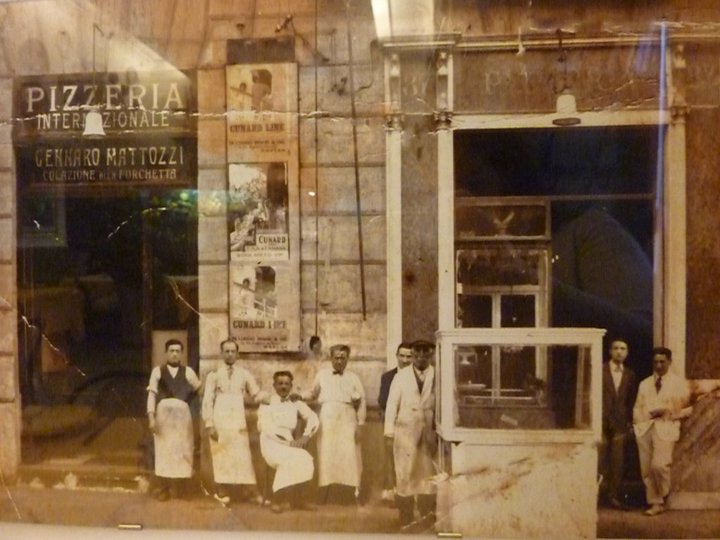

There is a keen keen sense, in the persisting primacy of Italy as a center for frozen pizza export, of the persistence of place in a globalized optic. But we await a true material history of the twentieth-century artifact of pizza, whose late twentieth century revival has ranged from the Occupy movement to the possible indulgences of sheltering in place during the pandemic. Indeed, the proliferation of birthplaces of pizza and declaration of its paternity has emerged as an almost political issue, as well as a point of pride, since display of plaques of foundational tropes that proclaim the “first pizza restaurant in America” and rightly celebrate pizza as a uniquely Italian-American food, perhaps competing with the historical 1989 marble plaque in Naples solemnly declaring to all who sought what was billed as an authentic pizza experience, “qui cento’anni fa nacque la pizza” [pizza was born here a hundred years ago].

The locality of the pizza has created a large export industry of frozen pies–able to flourish at the same time as the more restricted preparation of pizza whose superfine dough has been prepared and allowed to rise. The insistence of a birth site of the pizza not only creates a humanized legacy to countermand its global marketplace, but also to propel claims of authenticity by which it is underwritten; Naples still provides mozzarella to a broad range of purveyors, even if the shipping would hardly allow “fresh” cheese to melt on Portugese, Norwegian, and Bulgarian pizzas, or at the Isle of Lewis and Harris in the Hebrides-where a market for sourced mozzarella must exist.

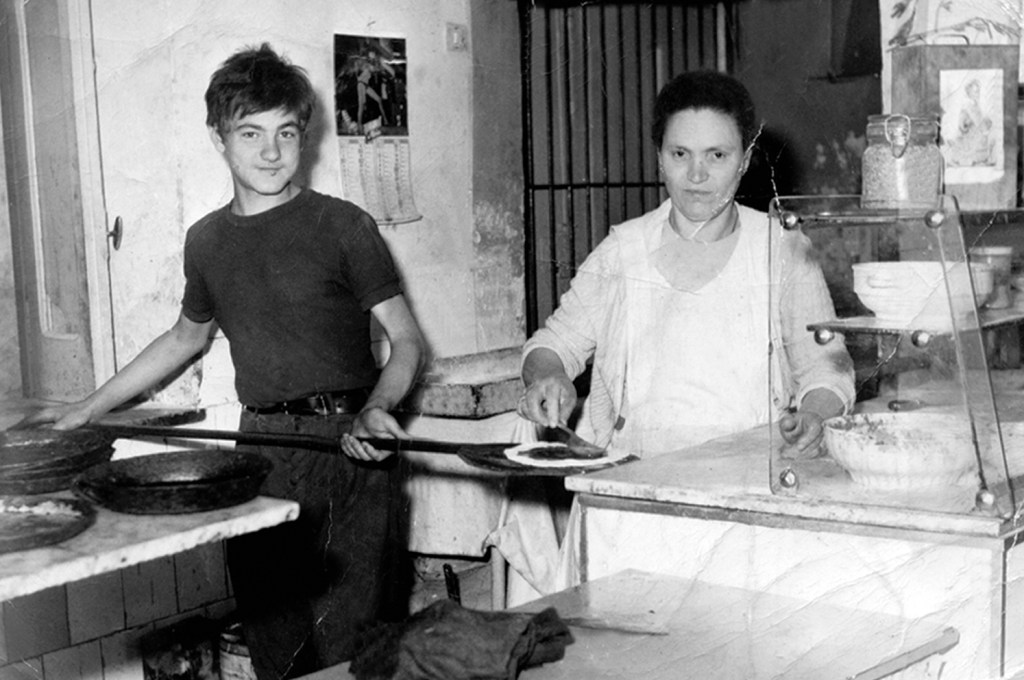

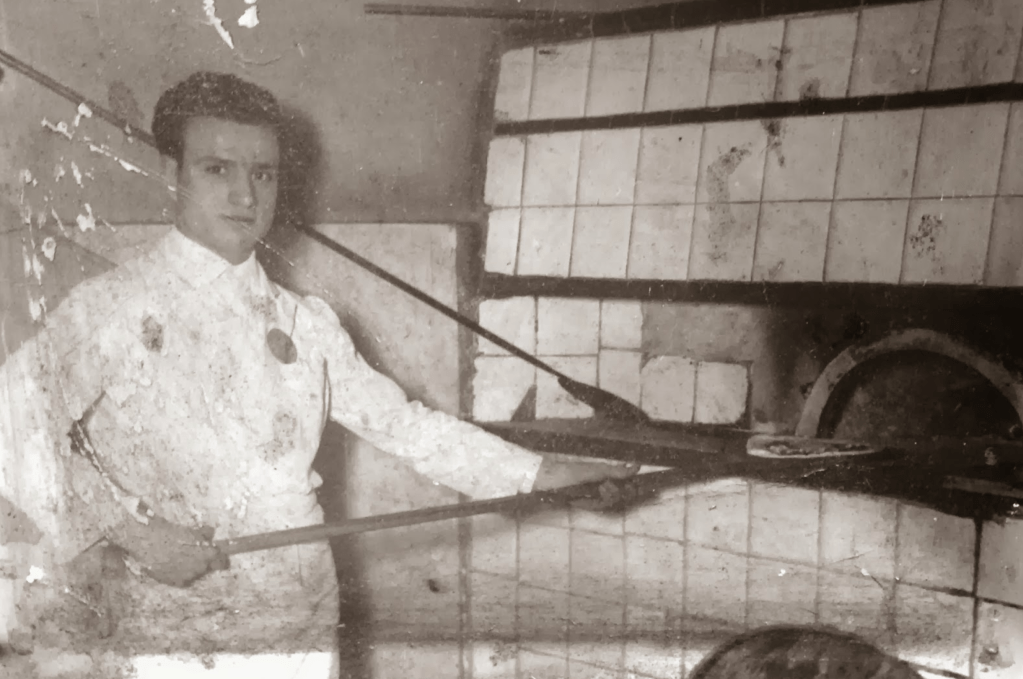

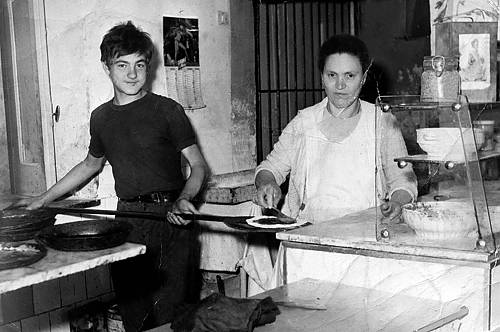

The transformation of the Italian-American pizza underwent sharp changes in the “Age of Chaos” difficult to capture. The steep difficulties that the transportation of midwestern mozzarella faced from the 1930s, expanding the cheese products’ shelf life by the expanding the shelf life of low-moisture varieties, by shifting the bacterial ratio, drying the cheese that wouldn’t compromise its ability to melt: the new bacterial ratio was almost akin to pasteurizing the final product curdled a cheese in one day alone, prefiguring shipments of processed cheese, mozzarella substitutes combining provolone, cheddar, and swiss, with vetch for stretchiness, and oil for uniform melting of cheese that melds into a glistening surface. It would be quite far from whatever the togaed Roman would see emerging from this oven of increased fat content, and shredded cheeses in sealable plastic bags followed, even if he seems to map onto the iconic image of the pizzaiuolo who uses his wooden peel to place a set of six pizzas in his brick oven above.

As much as the story of pizza is transatlantic, it is hardly a clear story of out-migration–one pegged to the migration of Neapolitans or Italians–the story of pizza is one of global imbalances, and the intersection of global economies and the economics of food with scarce resources, and, often, the pizza won currency as attempt to assuage if not to rectify an imbalance in trade. Polarization about the profit margin or value of pizza slices may place the expansion of Italian-American pizza in America the proliferation of local pizza styles, meeting a demand for fast food in the face of scarcity or the limits of disposable cash–removing the growth of the “taste” of pizza from any origins story abroad.

The local ties to different pizza recipes born and transmitted in different food markets, as much as among different communities, not always of Italian-American origin, were of unclear authorship. One might well take time to distinguish the geography of the “Italian-American,” from the flat pan Detroit style crust of flour, allegedly first cooked in the gasoline pan, the deep-dish pie of Chicago, born in the pre-war years, expanding as a taste for think mozzarella slices nestled, melting, in a sea of sauce of pelati, or the Missouri pizza showcasing processed “Provel,” or the melding of shredded mozzarella in New York thin-crust. So much was the New York pizza adopted as a native form of food that when I babysat for a teenager just returned from Italy whose elegant mother urged him to tell me about his recent year in Rome, the poor kid could barely articulate the poor quality of pizza in Italy, repeating as if to himself “it was so terrible!,” as if at a loss at how the expectations long stoked by his parents for his favorite food at Sal’s Pizzeria wasn’t at all like what was on offer across the Atlantic or anywhere on the Mediterranean. Without any modifiers able to characterize this problematic incommensurability of crust, toppings, or cheese that he had probably tried as hard as he could to not reject, the grandson of a great Italian cultural historian realized how pizza was tied to place, but his was reinvented on the Upper West Side from Sal’s, and could barely stomach the stuff abroad.

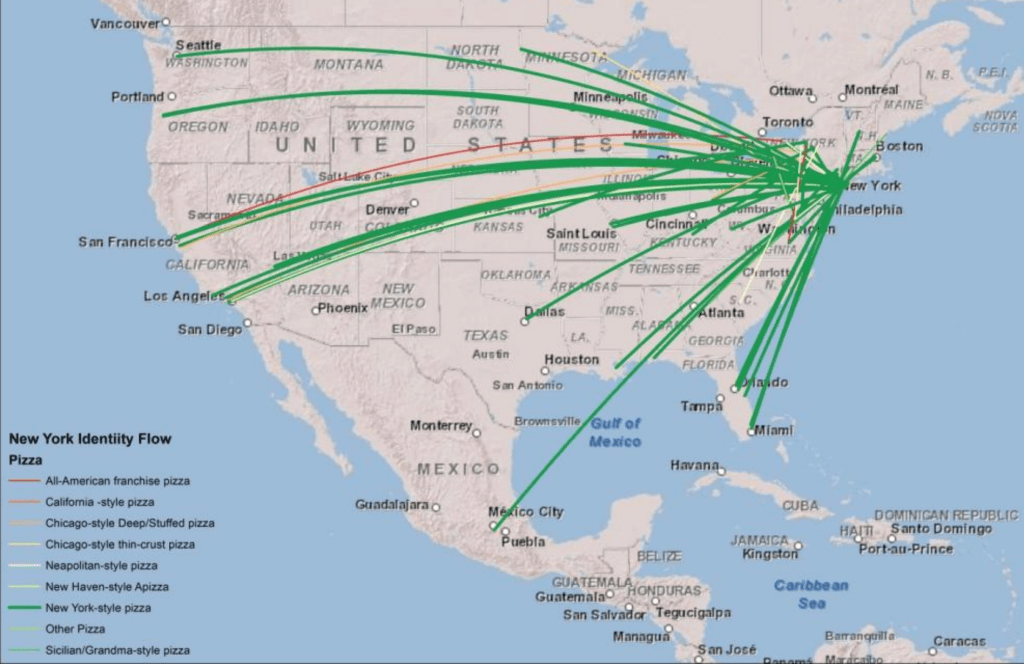

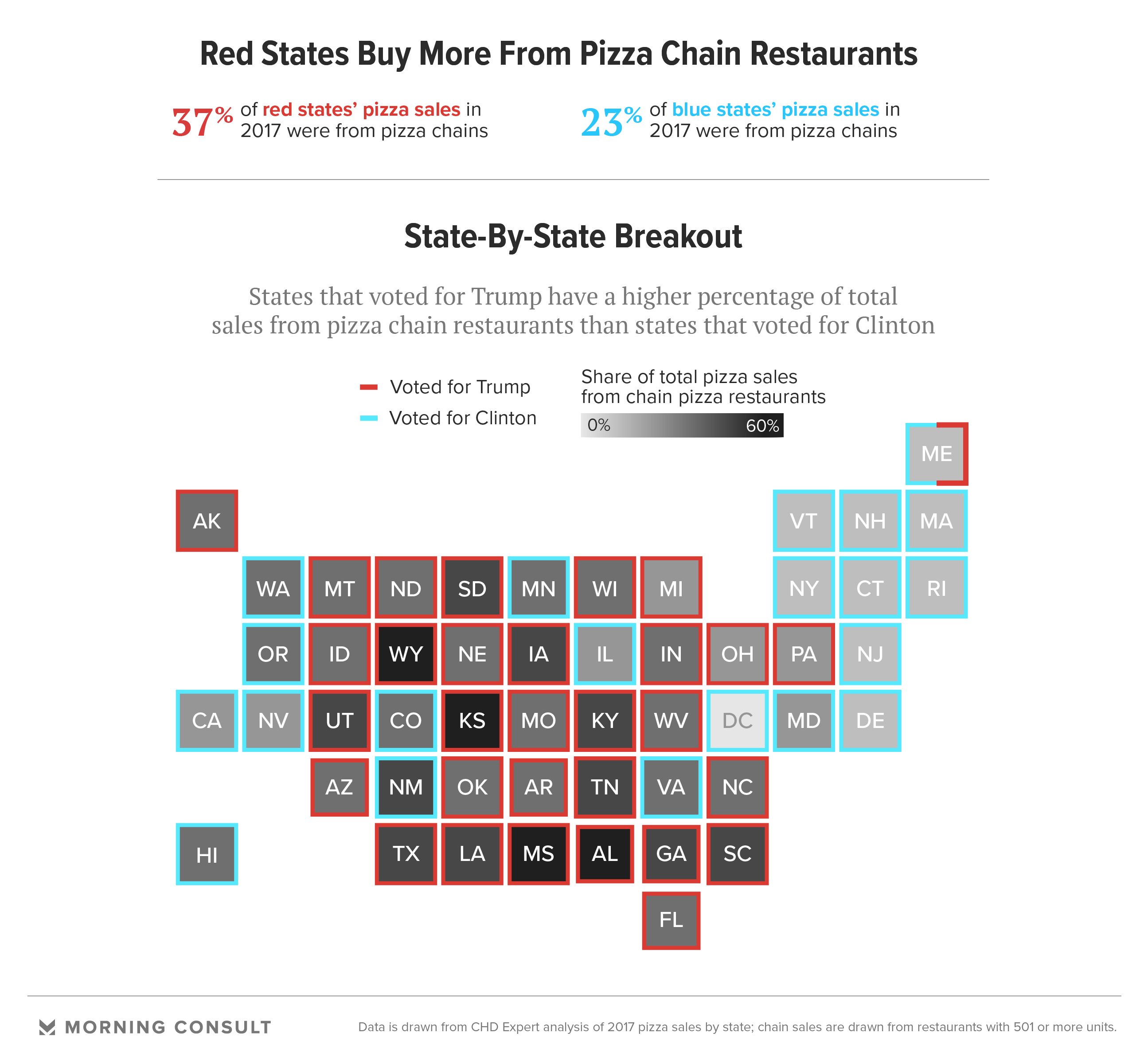

Might one map pizza preference with accuracy, to get a sense of the many countries of pizza that exist, for example, in the United States? While conditioned by the market, to be sure, and the cheapness of cheese, the ties to pizza slices are indeed as habitual as set in stone. The sense of locality of pizza defined on tastebuds lay far deeper than a variety of toppings in local styles of baking pies, each boasting lineages of authenticity in ways that served as as a friendly reminder just how local varieties of pizza remained. Each set of details–rich tomato sauce; thin crust; the interlacing of cheese and sauce–sustained deep allegiance. And while based on a small crowd-sourced study, Mark F. Turgeon in 2013 revealed the tug of regional pizza preferences among a hundred plus New Yorkers. Excitement at crowd-sourced data led Turgeon to sample friends trace trans-continental arcs to depict the nature of a “radial identity map” among “displaced” New Yorkers; Chicago-style (thin or thick) and franchise pizzas remained outliers, but also exercise a clear pull on preferences, even as pizza has globalized, whether due to a sense loyalty or the identification of pizza and home. New York slices may vary considerably from store to store, as a variety of quality, dough, and ratio of cheese to sauce–qualitative research of an intensive sort, that led to sampling 464 slices over eight years of intensive “fieldwork”–

As a New Yorker, I can relate to @thepizzzamap–it is impossible to not include reference to my own past pizza parlors at the end of this post–but find the radial map of personal preferences less “regional” than a reflection of the blurred space of airline routes. Can it be that we fetishize pizza as the memory of locality, tenaciously idealizing the quality of a slice in our memory as a personal madeleine of a lost sense of social cohesion? Is it a clear preference, or an affection for a mental tie to home, or to youth, and some undeniable nostalgia for the pizzas of the past?

Mark F. Turgeon, “Radial Map of Preferences among New Yorkers” (2013)

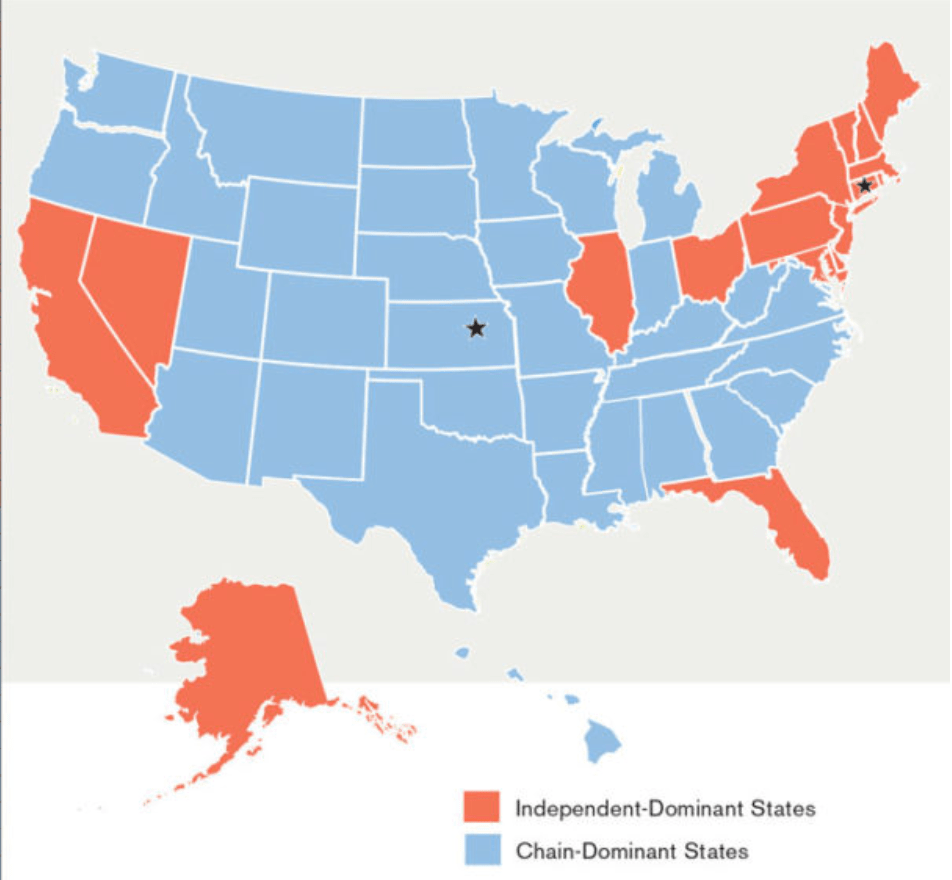

But the global dominance of chains, no doubt increased by the pandemic, makes us long to find local identity in an age of the increased homogenization of sorts of sauce.

The pizza seems to simple to map as a line of passionate ties to one place, in a world of increased mobility, when the “big picture” of pizza is too easily reduced to being pinned to one place in specific, without really ever asking how that local pie evolved–and whether it existed as an ideal type, pace @thepizzamap. The fact is that local and global are conflated in new ways in the pie, which despite its circular form, exists at the crossroads of the local and global that perhaps can never be truly mapped.

2. Neapolitan jurist, historian and philospher Giambattista Vico emphasized the import of tracking tangible changes in the making and remaking of meaning in words, long before the remaking of pizza by pre-ordering toppings acquired in the immigrant communities of Italians abroad, that featured slice toppings like pepperoni. Americans who seek them abroad will be dismayed. If flatbreads were long baked on slabs of stone of differing geometric forms, the pizza was a “daily bread” not needing to be broken, but easily cut. If pizza provided a stable among urban audiences that were demanding to be quickly served, the mobility of the pizza–a mobile food in the first place, as a historic street food!–made it a perfect fit with a society in motion. If cheese-making is not an instant process, the instant presence of pizza from melted cheese was the definition of the quick fix. If bread was long accepted as a form of hospitality for all who joined the table, pizza was as mobile as food markets where cheese and bread existed in good supply, ready to be cooked in a melded symbiosis.

The pizza was a source of reassurance of in a troubled time, and especially among the calorically deprived. For Dante, in the Convivio, affirmed that “blessed are the few who sit at the table where the bread of the angels is eaten,” the pizza was popular far from the table. if as an exile he felt the absence of bread, the quick identification of content that the taste of pizza promised to reconstitute a sense of belonging even for those not seated at the table in urban settings, seeking a swift caloric fix even if they were hardly starving in the streets.

Tracking a corso and ricorso of pizza making from the first local fabrication of pizzas to the remaking of a pie with not fresh but processed cheeses, would reveal how it was punctuated by deep ruptures, recasting the transformation of pizza and pizza-making solely in transatlantic terms. The cyclical transformation of pizza making suggests that pizza has not conquered the world but that the world been conquered by it, as the pizza that has expanded globally in unprecedented terms was altered as a to-go food for ready fabrication and easy consumption for food markets far beyond the local, and by sourcing ingredients: and yet we continue to acknowledge that we are afflicted by an increasing glut of pizza, globally. The result of fast food explosion may have made the United States among the most saturated markets of pizza in the world in recent years–

Add title

Global Saturation of Pizza, 2018 (c) Aaron Allen

–the nearly global saturation of pizza (still greater, if not by much, in Canada, despite all that uninhabited territory), Australia, and, especially, Brazil and the UK, the spread of pizza seems attracted by markets of the greatest disposable cash on hand

Has pizza surreptitiously come to be emblematic, ironically for a fresh baked food, emblematic of the distance of the food producers from the calories of food consumers eat?

Neapolitan pizzaiuolo Enzo Coccia celebrated the certification as a moral victory, late in arriving if long deserved–well-deserved if only “after 250 years of waiting.” Although it would not dent or shift the $150 billion market for the global comfort food. But if pizza were officially repatriated, we await a true material history of the mobility of pizza as a material good or artifact, long before late twentieth century expansion of chain “standard” pizza offered consolation by pandemic deliveries. The global story of the pizza may find a precursor in the itinerary of the tomato–an “original globe-trotter” Haissam Hussein mapped in his ” Food Chains map” of 2011, and the current expansion of tomato as a fully globalized crop, even as the Association of Authentic Pizzaiuoli of Naples defend the exclusivity of pizza using San Marzano grown beneath Mt Vesuvius to localize its landscape.

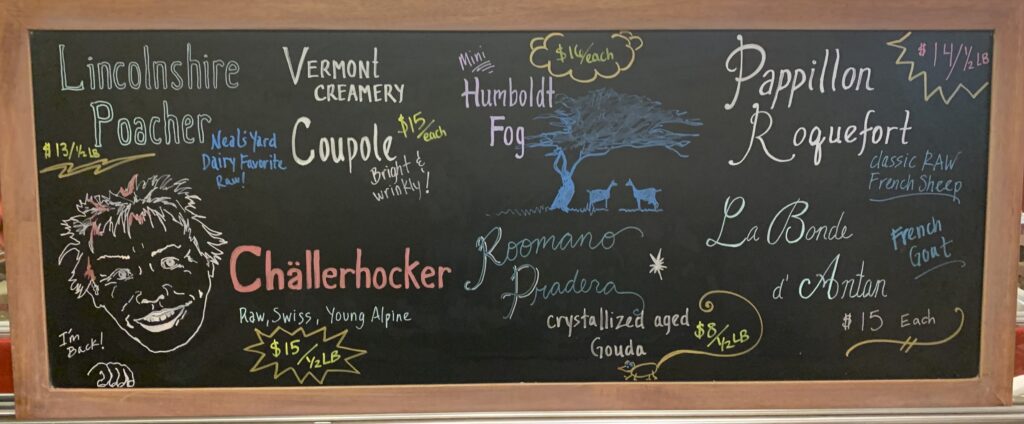

The authenticity of the pizza now emulates the DOC certification of wines, themselves oriented around Mt. Vesuvius. The sourcing of ingredients of local pizzas by quality San Marzano tomatoes from the volcanic ash that also enriches agricultural asserts a local tradition that pierces through the dangerous declension of the art of pizza-making on a global scale. If pizza might be made in the 1900s in America to offer some sense of stability at a time of increased global movement and geographic nostalgia, the sourcing of pizza is increasingly linked to a region’s local terroir–if not matched to a wine other than Chianti that echoes the provenance of grapes denominazione di origine controllata or di origine controllata e garantita–as a guarantee to the pizza’s own relative purity, even if the classificatory boundaries promising authenticity are a bit fluid for different map-makers.

While the growth of pizza has been long associated with immigration, and romanticizing of place on pizza boxes that were delivered to residences, in a vernacular cartography that promoted fantasies of importation produced by maps, and the romance of the “Italian American” import that arrived easily from overseas.

Tomato sauce seemed to derive, in the wonderful menu above, from between the volcanic ash of Mt. Vesuvius and Mt. Etna, whose minerality had created a new terrain for tomato cultivation and red sauce in the Old World–the two most prominent natural markers in the iconic buildings–the alternating spires and arches of Milan’s cathedral; the Vatican; Pisa’s Leaning Tower; Bari’s Cathedral; Florence’s domed Duomo.–that defined the built landscape of the peninsula But if the language of restaurant menus, placemats, and those delivery boxes that promised to orient you to a new form of culinary delight delivered not from the local pizzeria, but the mythic historical origins that pizza claimed, the maps concealed the actual geography in which Italian-American pizza has become a model for something of a flat earth society of its own, long before Kyrie Irving announced he was listening to “both sides” of “debate” in what was either a stunt, extended joke about global geography or a sign of the real problem that “no real picture of the [spherical] Earth” existed as photos are flat. The brouhaha might have been a stunt, but no better image of the flat earth existed as the world of pizza became as flat as the pie itself, as pizza-making so quickly grew global to challenge the its ability to survive as a local art, only increasing demand for a birth certificate.

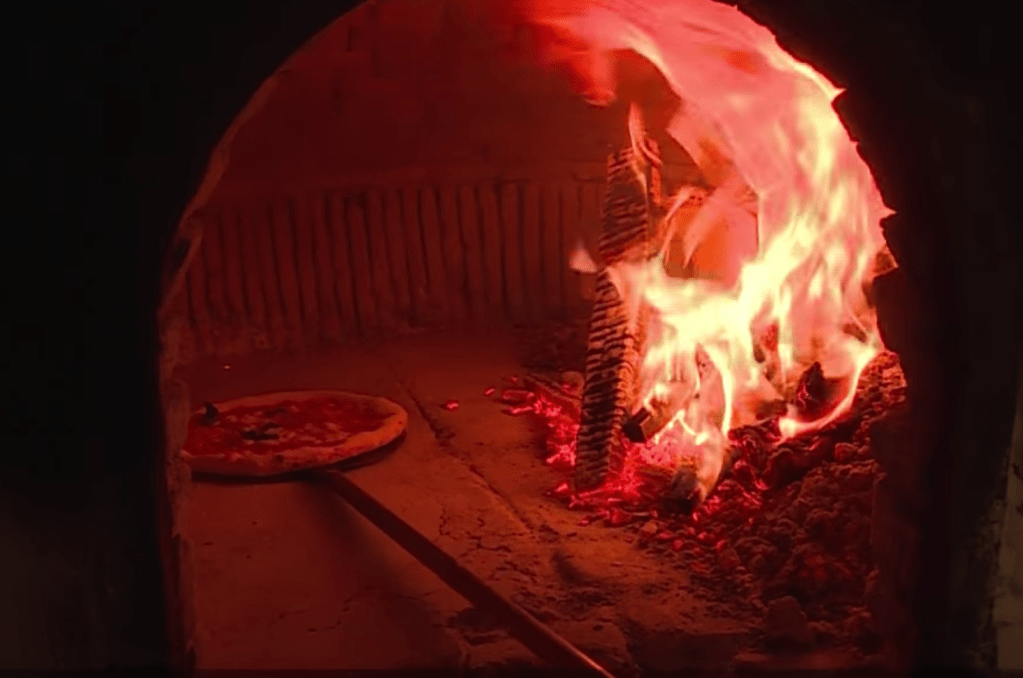

The quality of the pizza as a made form has been deeply compromised by the multinationals who had deracinated the pizza–crust, cheese, and fresh tomatoes–from the wood-burning ovens of its birth. In the face of the fears of pizza’s globalization with its remove to an assembly line of food production, and indeed a global export of increasing popularity world wide, the affirmation of the birthplace of its art and making was a sublimation of locating the globally circulated and oft commodified good as a site of making and a from of meaning-making, linked to a territory, if not affirming exclusive ownership over pizza in ways that openly privileged its authenticity. While the most popular pizzas on Yelp often place pizza beside other sites of carbo-loading, topped with penne alla vodka and chicken parmesan–is such a concoction truly even a pizza?

The history and geography of pizza seems declensionist in tenor in quite decisive ways, even while it abstained from making any explicit point about quality, in an era when multinationals have the upper hand. Acknowledgement of the pinpointing of the careful custody of pizza-making, proofing of dough, and selection of sauces and bufala mozzarella, fired in a searing oven to crisp its outer crust, seemed to rescue the craft from how the food industry had transformed by mechanical reproduction and an economics of Taylorization to saturate the world with “pizza” drowned in an overabundance of pre-shredded cheese.

The expansion of the “monster pizza” have made the pizza a figure of excessive caloric indulgence, and overeating, as if we are seeking caloric comfort, has dispersed a pizza globally that is far from the high-temperatures pizza demanded–blistering crusts at 700°-900° Fahrenheit–in Neapolitan ovens. The unmooring of pizza from place expanded with both the production of frozen pizza as a global commodity–and the spread globally of pizza styles, in ways that have prompted a sort of “pizza tourism” showcasing the styles of pizza making in different nations or the heritages of “old style” pizza in New York city, the remove of pizza making from the movement of populations is striking, as pizza has spread both globally and along class lines as a food of comfort and reassurance in a world of less time, and more demand for calories.

[

Such flared transoceanic arrows are tokens of globalization that recall nothing so much as a flight path map. Is the map of the “global traveller” of the tomato, black pepper, or coffee is a global story, evidence of globalizations past across state lines. But exulting in transoceanic leaps and smooth itineraries are uncannily akin to a modern global citizen. How misleading is the graphic symbolism, or is the story map being knowingly coy? The map oddly elides human agency, but it sets the stage for the global pizza, where the global shifts of population created the sense of primacy and authenticity in the pizza as large population movements occurred,–embracing the pizza as a culinary pleasure outside prepared meals and formally sanctioned culinary recipe books. The red arc of the tomato glides smoothly across the Atlantic ocean, ostensibly arrived from Peru as a small cherry-like fruit,–akin to the “golden apple” perhaps but not the cherry tomato we know today. The tree tomato better known as the tamarillo is a fast-growing nightshade growing with little water that is prized in arid Peruvian highlands–as it is now in Australia, too–whose tanginess is culinarily removed from the larger tomato that became a garden fruit, whose true global descendant is pizza sauce,–even if we have several growing in our garden. If a case can be made ketchup may be the true global citizen, and the product of bottling and preservation, pizza, for its often round edges, is a compelling example and emblem of the reinvention of boundary crossing, and the difficulties of smooth travel that are far more characteristic of globalism, if globalism is also often fatalistically fed by modern appetites and tastes.

If the tree tomato, a nightshade, is widely grown in elevated areas of Peru as a farmed crop, the mobility of the tomato as a cultivar accelerated across the Mediterranean, far from a modern “cherry tomato,” if as egg-shaped hanging fruit it is still confused with the fruit that Mayans had carefully bred for sweetness and pulp. And if we owe the tomato sauce we know to Mayan agronomists who terracing slopes rich with volcanic ash, perfect for tomatoes, as well as for corn, squash, pumpkins, and chile, as well as cacao. The stage was entirely set for conquistadors like Cortes to so appreciate tomatoes at an Aztec market before bringing seeds and cultivars to Spain that arrived, changing the course of world history, by extension at the Viceroy of Naples to grow in the warm sunlight of southern Italy and the mineral rich earth of Mt Vesuvius that long defined pizza’s pedigree.

While cultivated by Mayans and Incas 3,000 years ago, presentist encyclopedias channel vaguely anti-immigrant sentiments by linking the spread of pizza to the arrival of Italian immigrants in America, in pseudo-causalities that peg the pie to the emigration of 26 Italians seeking work worldwide from 1870 to 1970, as “Pizza became as popular as it did in part because of the sheer number of Italian immigrants.” The integration of the tomato in local cuisines is a hidden from map of the tomato’s global travels–even if it is striking that save on the region of Campania around Naples, and Sicily, pasta was not made with tomato sauce until the 1830; pizza was unknown outside Naples, featuring famously in Neapolitan street scenes of Gaetano Dura and others that feature mobile “venditori di pizze.” Zachary Nowak’s documentary search for any basis in the mythic origins of Pizza Margherita casts some shade on the legend was prepared, as the Brandi Pizzeria boasts, that the dish was transported to the Regina Margherita in the Capodimonte Palace in 1889, but the legend helpslink the dish that had struck Belle Epoque visitors as a locally improvised meal that seemed as if it derived from the gutter, a literal “street food” of questionable desirability to a national dish. The improbable transformation of the food to one fit for a monarch habituated to a francophone menu of the elegant house of Savoy-seems an apt myth destined to describe how the local became global, if it hardly captures the shift from the outmigration of Neapolitans to the global reach of pizza.

Precisely the global ubiquity and reinvented nature of pizza as a comfort food par excellence that demands dropping a pin the exact site, a la Google Maps, where pizza was first fabricated–either in New York, seeing the pizza as invented by the first immigrants in America, as a food that found its new audience in the American metropole, or the “best” pizza is found in Chicago (deep dish!), Detroit, Boston, or as reinvented in Berkeley CA. If the eighteenth-century “seller of pizzas” sold triangular slices out of the back door of a bakery circa 1825 in Naples, the pizza has been reclaimed as a site of the local community at the same time, in an almost surprisingly territorial manner, as if a search for community as a panacea for an age of globalization. The popular lithograph from a series of Neapolitan professions that seemed characteristic of local food and habits, the striking distance between pizza’s production and consumption would be a terrifying map, especially in relation to the projected expansion of global pizza sales, and a divide of unbridgeable sorts with the sea of canned tomatoes blanketing melted gobs of mozzarella in the deep dish.

The tenacity of this definition of the artisanal is of course rooted in the premium on making that has developed in different micro-heritages of pizza-making, developed in markets, there is a cunning contradiction, never confronted head on, between the sensual immediacy of the pizza that is present for the pleasure of the consumer, the foundational moment of the first pizza as a remote moment that is repeated in each current slice’s pleasure, and the sense of the pizza as something on offer everywhere, and always able to be delivered. The roots of the pizza that emerges from the oven may be deep in the first ovens of the first to third century AD, in Roman ovens, the presence of the slices as an index of satisfaction always on offer threaten to uproot the pizza from any context of making at all.

If the third century mosaic of baking bread in a hearth seems to root the gesture of pizza-making in the past, pizza is always denying its own origins, or the history of its making, re-presenting itself as on offer for ready consumption and consolation in a world of scarce resources and resourcefulness.

4. The art of pizza making obscured with the sense of plenty and at low prices, pizza has been removed from the place of growing, its availability at any place claimed by consumers as their own, so that the historic hearth of the pizza oven is rapidly receding in the mirror of global memory, a receding of a once savory palpable past. For global consumption has transformed pizza-making as an art; while pizza is questionably able to inculcate moral virtue, the virtue of preserving the traditions of pizza making as an art was what UNESCO affirmed: not the ingredients but transmission of a pie made by the “hands, heart and soul of the pizzaiuolo,” in the words of one Neapolitan, as an alchemical stretching and turning of dough as much as its garnishing with cheese, a tradition that arose from the humble beginnings of feeding those from the warmth of an oven to satisfying a demand for the readiness whose reach, feed by food delivery apps during the global pandemic, have only further displaced it from its geographic origins or the locally produced foods it once expressed.

The demand to identify pizza as a [[patrimony of humanity responded to the remaking of pizza, long after the food’s outmigration from the Campagna or region of Naples, to affirm the artisanal traditions of pizza-making as a local tradition. The acknowledgement of pizza-making as a local craft that belonged to humanity–rather than a globalized food able to gain meaning as it moved, frictionlessly, across the globe, on networks of food-distribution by -engineering–claimed a sense of meaning as if pizza demanded reclaiming as a form of Intellectual Property, as if this would boost the lagging economy of the mezzogiorno, and canonically affirm the patrimony of pizza as a local good now that it had gained global popularity as able to be discovered anywhere on the map. The range of comments that tourists of Anglophone persuasions now bring to Neapolitan pizzas even as they make pilgrimages of quasi-spiritual zeal–“You can’t pick really it up”; “Can’t they just make it crisper?”–provokes frequent back-and forth from the locals who don’t understand the reluctance of visitors to use silverware, or to order a personal pie, but the entitled ownership of the pizza as American–or a recognized version of what was an Italian-American food–has become almost a cultural tussle over expectations about what is called a pizza, and what one wants to find in a pie: a meal, or a rush of super-refined flour coated with a dispersion of cheese and healthy toppings, often assembled in industrial terms en masse. ]]

The practice of making pizza was affirmed as a sort of good and an “intellectual property” even if an intangible one, a formal acknowledgement of the authorship of the artisan baker–mirroring the global use of duplicitous terms as “traditional,” “artisanal,” or “authentic” to sell processed cheese and pureed tomatoes as “natural,” maintaining the global availability of mass-produced frozen pizzas that are fabricated without any oversight in factories of food preparation, and elevating the intense familiarity with pizza-making belonging to a cultural patrimony of all humanity, more than the pizza-making assembly line.

Does the increased distribution of processed tomatoes–each nation color-coded by the hue of the fruit–provides a sense of its ready global availability? The smoothness of delivery to any place in the world to which we are increasingly accustomed has deracinated the pizza from place.

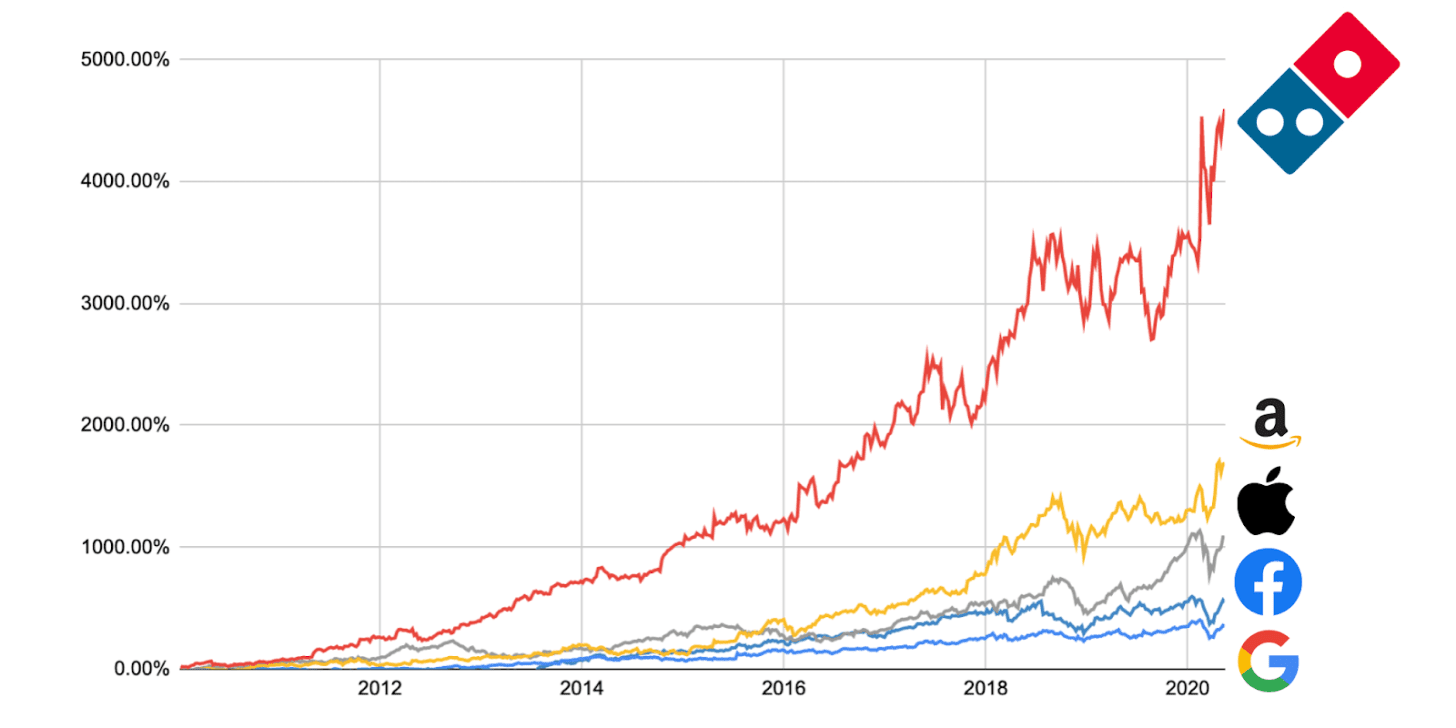

The profits of pizza-making grew, first in parallel to the first alarms for food scarcity after 2012, stubbornly persistent since the Recession and enduring past 2012, in ways that have created an astronomic rise in the stock of Domino’s as its global plans expanded, and the careful planning of its “cloud kitchen” have led to a remarkable if also probably unsustainable rise of over 4000% riding on the bond with consumers Domino’s created as a cheap dine-in option, probably forged by the familiarity of the Pizza Tracker mobile ordering app, since widely developed by restaurants, as well as independents’ innovative introduction of the Slice app allowing access to menus of quality local independents. Long before the COVID-19 pandemic found so many ordering in, the global growth of volume of pizza sales made Domino’s stock to rise faster than even than Amazon, Facebook, or tech stocks.

5. There’s a case to be made that the pizza was always global, even if the local production of pizza was once a fundamental part of the pizza–the promise of a freshly baked pie. If the craft of pizza-making was once local, the archeology of pizza-making suggests stages of globalization in which its meaning changed–and evolved by leaps. The first age of this global story might begin with the arrival of a round bread in the periphery of the Byzantine Empire in Naples, “pita,” often eaten with feta cheese, extending to the importation of the tomato as a crop, after the first British sighting c. 1700 in North Carolina; the second stretching from Vico and the first documented preference sailors at Naples’ port had for pizza marinara in 1738, through the emergence of the pizzaiolo around 1750 ad sale of pizzas from the backdoors of Naples bakeries c. 1825; the third age marked by the mythic royal acknowledgement of tomato, mozzarella and basil pizza as her preferred dish, despite her sophisticated palate, c. 1880; before the transition, long after Italian out-migration, to a fourth age of Italian-American re-invention, beginning circa 1938, that expanded in the postwar era an arrival emblematized by the placement of pepperoni on pizza slices and delivery or “to-go” eating styles in the age of fast food, where pizza delivery as indeed extended across the increasingly frictionless smooth surface of the globe.

To be sure, the ever-expanding trade in frozen pizzas has changed the global currency of the pizza since the 1980s, when local pizzerie first seem to have spread across the East Coast of the United States. Accelerated by recent abilities to engineer”individual quick frozen” pizzas by nitrogen to lock in “freshness” in 200 seconds, the designation tries to moor the ubiquity of the pleasure food, and affirm the “local” meaning of an almost paradigmatic globalized food, moving across global space in almost frictionless terms. The UNESCO identification was sought by Neapolitan pizza makers in an attempt to pin monetary value by such certification recast the pizza as a form of IP, assigned it a cultural valuation as an intangible good–leading to the presence of the Minister of Culture and Agriculture to attend the ceremonial event marking the placement of Neapolitan pizza on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity–even if pizza must rank among the most likely intangibles to trigger a vagal nerve. And even if the declaration insists on not making “any reference to exclusive ownership over intangible cultural heritage” as a Heritage of Humanity, the designation of the globally circulating good is rooted in the botteghe and bakeries of Naples, and in their wood-fired ovens, at last respectfully acknowledged the local provenance of a global good, cooked and hawked on the streets of Naples, where it was born in the exchanges of th eurban fabric, long before the invention of anything like processed cheese that make the dominant global export almost foreign to Italy.

4. The certification by UNESCO didn’t really affirm pizza as of Italian origin in nationalistic terms, but preserved the transmission of hand-thrown pizzas as a local tradition–the petition for recognition from the Association of Authentic Neapolitan Pizza-Makers had requested the making of pizza and the local transmission of tacit knowledge as tied to the local earth of Mt. Vesuvius that fed local San Marzano tomatoes and to regionally produced cheese. The recognition was a late acknowledgement, perhaps, of the extraction of wealth from the long compromised mezzogiorno, whose agrarian economy has for so long been dominated by feudal landlords to almost make it part of a global south. Perhaps the recognition of pizza as a form of IP was to much of the world risible given the prominence of the pizza on the global marketplace. But if Franceschini gloried that afternoon in seeing it as late in coming to remedy a deep national indignity, even if it raised eyebrows online and in global press.

At the ceremonial relighting of the “first pizza oven” in Naples off of via Chiaia, the nation’s Minister of Culture, Dario Franceschini, described with some horror that the certification won that year for pizza-making as a local art would help stay “studies” demonstrating many who enjoy the dish are ignorant of pizza’s Italian origins–even if the creation of pizza is prominently recognized by Italians as nestled in the products of Campania, and the tomatoes nourished in the volcanic ash of Mt. Vesuvius, that foreboding presence on the Neapolitan horizon, as a storied contribution to a national cuisine: and if the arrival of the tomato from its global itinerary took new directions toward a table food as it was fed by nutrients of Mt. Vesuvius’ volcanic ash and with the minerality of the sedimentary soils of the pre-Apennine hills, and olive oil, the addition to pizza gave it a distinctly global spin, difficult if not impossible to localize in Campania–and nourished in global food markets.

The Campanian origins of pizza might be better put in the political divisions of the peninsula into small states and principalities, but food certification has become almost a means to validate and reinforce Italy’s frontiers in an age of globalization–as national boundary lines are increasingly crossed with apparent ease–defining a national patrimony of the peninsula as a table of a bottega laden with signifiers of artisanal foods promising an experiential immersion in gustatory well-being–raising the question of how to “map” Italian food–beyond the outmigration that forged pizza as a cultural good defined al’estero that prepared the way for a global food readily consumed on the fly.

The sourcing of organic flour, locally sourced olive oil, and fresh mozzarella challenged the remaking of pizza in a food distribution network that promises its ready delivery on a global scale, remaking the relation of local and global that globalization had begun. Andy yet–not only in terms of the global migration of the tomato to the peninsula, arriving not with Aeneas but long after the Columbian discoveries, and locally cultivated for food in the 1700s, centuries after its landfall in Seville c. 1540, as preserving of tomatoes of the nineteenth century gave global legs to allow its sauce to bring solace among globally displaced.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62589522/la_gatta.0.0.jpg)

It is hardly a notable debate that the pizza is a globalized food. And in responde, a demand for a story map that reassuringly pins pizza to a precise place if not a founding father, to one restaurant or city, affirming a birth certificate is an origins story as pizza is even an emblem of globalization, even if it claims benediction and recognition by one of Italy’s first–also one of its last–queens, Regina Margherita, wife of Umberto I, who allegedly in 1889 (or 1880), wanted to “eat like the poor people,” and birthed the food in the city where she had earlier given birth to a royal heir.

For most, of course, pizza had in fact so become part of a global patrimony of consumption, easily available and readily delivered–and the joy of a pizza party was recognizably Neapolitan, it was hard not to note that the very pizzeria that celebrated localism had franchise in New York–and prominently placed that location before Naples on its own marquee?

The pizza is located in many ways between an early modern global imaginary–marked by the arrival and assimilation of the tomato–to the space of globalization itself, in which Naples seems to have acted as a culinary hinge of cultural transmission. Neapolitans are entrepreneurs who “make a product that has conquered the world,” claimed Sorbillo, fresh back from opening the New York branch of his store I once sampled, describing the pizza as an enduring monument that “started in Naples and survived the centuries, despite all the difficulties, the earthquakes, Vesuvius, the war, the wars,” casting the pie an enduring monument in time that survived due to the assiduity and care of pizzaiuoli in their dedication to their art. Few doubt pizza’s Italian origins or provenance as a creation, but the transformation of pizza making as a food able to move smoothly over the globe, to provide customers with ready satisfaction. Although strands of vegetable-oil coated cheese seem today to wrap the increasingly smooth surface of the globe, feeding appetite of those on the go or strapped for time with pies that pops into an oven to updates the pizza as “easy-bake”–all too often a sort of plate for with fat-rich toppings, boasting a cornucopia of bounty whose range of toppings may be a cultural forest that has almost entirely obscured the slices of wood-fired Neapolitan pies.

Yet the above pizza was baked in Tokyo, and off Travel Advisor. And try as we can to map its origins, the pizza is a product in many ways of globalization, from its status as a consolation for displacement and those on the go to the current global glut of pizza in an age of food scarcity that the world does seem to more broadly regard pizza as provided by multinationals, more than a dedicated craft.

5. The notion of historical ages of pizza-making may seem romantic. It is of curse a bow, as much as a nod, to the cultural historian’s sense of historical trajectories in which to situate the pedestrian art of pizza lies in its making, akin to the methodologies by which the great historical philologist studied the laws. Writing in Naples circa 1720, Vico, whose Scienza nuova printed in 1725 omits any reference to pizza-making in its search for the social origins of truth, but may offer a better key to its mapping that can do more justice to the migration of the local custom than any plaque. While Vico was addressing rhetoricians, and not pizzaioli, the verum-factum principle that celebrates the human making of truths may offer a guide to placing pizza within the unearthing of ancient wisdom from Italians.

The overstretching cheese of a pizza is perhaps a good sign as any of liquid modernity. But the “making” of pizza was by its very nature long liquid, by 1858, years before the mythic presentation of a pie that so pleased the tastebuds of the Queen of Italy, Margherita, consort of Umberto I, Italy’s first king, she a pizzaiuolo for pizza prepared in the kitchen of Capodimonte, the former Bourbon palace and named her favorite, causing the pizzaiuolo Raffaele to rechristen his craft or at least to market it by a new name. The story of origins has served, morover, to bond cultural integration of the tomato-rich dish of pizza from the world of Naples within the national consciousness of Italians.

But the myth of the preparation of the first pizza in 1889 persists, perpetuated perhaps by the fraudulent royal certificate posted in a Neapolitan pizzeria that purports the craft of one Neapolitan pizzaiuolo, Raffaelle, was recognized by Queen Margherita as a maestro of pizza, to be balanced with the claim circa 1880 that the queen was claimed to have “wanted to eat like poor people.” While it is probably wrong to see Margherita’s pleasure at one of several pizzas prepared for her a prelude to the current expansion of pizza as a pleasurable food globally, it is nice to imagine the elevated origins of the pleasure of pizza. One might better examine the making of pizza.

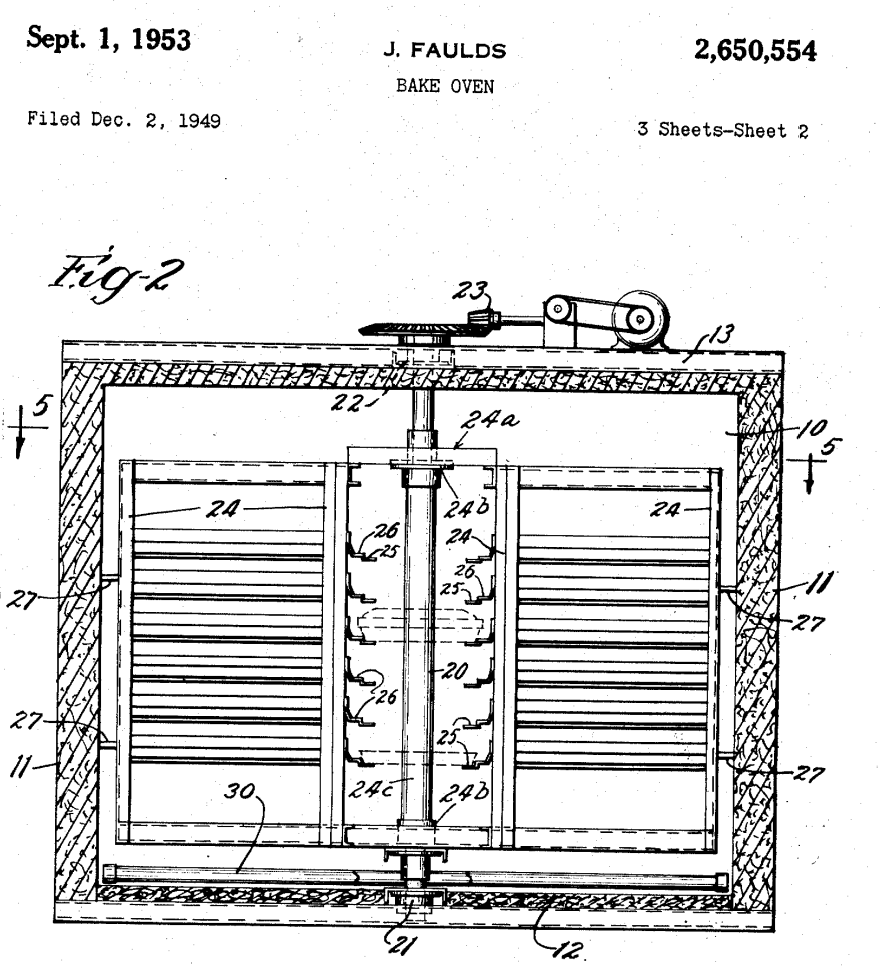

But the wood-burning hearths of high temperature remained a center of the pizzerie, defining a Neapolitan style that shifted in America with the rise of gas-burning ovens, and rotating shelve gas ovens of the mid-1950s that heated a distinctly drier and differently flavored sort of pie long transmitted in local memory as an early “slow food.”

Neapolitan pizzaiuoli are digging in their feet in resistance to the awesome scale of the globalization of pizza. The growing non-profit Verace Pizza Napoletana, the Authentic Pizza Association of Naples, Italy, have anointed themselves cultural custodians since 1988, a hundred years after the alleged crafting of a pizza by a local master of the art of pizza spinning for the Queen of Italy, who had preferred it so much out of the three forms of pizzas she had selected from a list, that it was bequeathed her name: since 2013 a museum of pizza spinning has already preserved the intangible patrimony practiced by about 3,000 practicing pizzaiuoli in Naples no doubt increased demand to recognize the craft: the cultural transmission spinning pies by the trained hands of a pizzaiolo in the bottega, exclusively from local foodstuffs–San Marzano tomatoes grown at the foot of Mt. Vesuvius, mozzarella cheese of water buffalo from Campanian marshlands, and local flour–that cemented the local provenance of the food to region, in an age when pizzas are made by multinationals form mass produced shredded cheese and sausages. Though they compromise for pizzaioli baking pies in gas ovens, electric ovens, or wood-fired ovens–the traditional forno a legno–to merit the seal of approval, a steaming volcano championing the local but taking its authority from the tricolore, echoed in the imprimatur that seems a monitory flag raised against the ersatz pizza emerging globally.

6. But can one map authenticity in the mosaic of tastes in a pizza, or pin pizza’s invention (or reinvention) to place? Perhaps the local claims on the global pizza that were made are better seen as a reflection of the processes of flattening of globalization itself.

The association of pizza as sign of normalcy made delivery so popular in the pandemic to be an almost necessary service, growing demand, heightened by periods of sheltering in place, of disentangling the nearly melted geography that led this global food to be so readily desired to be the quick meal readily at hand and consumed over 21,000 slices per minute–where over one quarter American households eating over eight pizza pies a month.

The morphing of pizza to meet demand for to-go orders and delivery is a declensionist history, often by now long removed from the story of migration, or abstracted from the movement of populations. For pizza was defined by its availability and ubiquity, tied to webs of travel and mobility, from chains of productions to market reach, and consumed on the go. These webs were stretched in a broad net of production extending beyond the stretch of wisps of melted cheese that distinguished global appetite, and is extended by the brand evolution that the spread of frozen pizza has brought to its global consumption of a fully globalized good that lost any sense of locality: Australians eat an ounce of pizza a day, often topped by prawns, barbecue sauce, and pineapple, in an antipodal variation of kangaroo meat, and Indian pizzas include paneer and chicken tikka, Turkey adding lamb and Sweden oddly shaped meatballs, the eclipse of pizza-making as an art using in local oil and fresh oregano is eclipsed on a global marketplace as it has become a flexible vehicle for caloric consumption that could be delivered by drone, as Dodo.

If pizza-making was an intangible, the crisp crust produced by the intense heat of a wood-burning oven, for UNESCO, without processed cheeses, and certainly not frozen–even if the exports of frozen pizzas from Italy nearly doubled in the previous decade, leading multinationals to create frozen pizza factories outside of Naples, hoping to boast the arrival to global markets of a once local food of a similar degree of authenticity. As Nestlé and other multinationals enter into a market for frozen pizza boasting local qualities, and pizza has become a global signifier, the globalization of the pizza has culminated in a privileged metaphor for globalism’s favorite cartographic toolbox. The pizza as frame of reference intimated not only the inventive and pleasing nature of the GIS map, but its ability to link global and local in provocative ways to convey the interconnectivity of independent layers of any data visualization that “work like the way tomato sauce interacts with cheese nearly meld in the oven while remaining separate” in a GIS framework that functions as a pizza box to “deliver the goods” by correlating data from federal, national, and local portals’ vetted reliable data on anything from algal blooms to fender bender locations, even if the instantaneous generation of maps for ready consumption echoes the global availability of the pizza’s toppings, as if they were open data. If the analogy of making is quite non-arbitrary to me, the toppings are indeed purchased at the supermarket and precut, perhaps prepared in refrigerated shrink-wrapped vats a la Pizza Hut, and with minimal fantasy. The “pizza” as a figure of the GIS layers or an ARC map takes the oven as analogous to the cold silicon chip of computer circuitry, undercutting pizza making as an art of supervising an intense eight minutes of baking in the temperature of a true pizza oven as an art–more than a Taylorist process. If data should meld to a map like the cheese on a pizza, describing data as precut “toppings” assembled on the base layer of a crust minimizes the mapmaker’s art, of course, as well; the global availability of GIS masks its rootedness in a historical time, of course. The quite clever rhetorical metaphor may persuade us of the ease of access to GIS tools–and the pleasure of their consumption, as if they were organic and both familiar and friendly to the cartographer-to-be.

–even if the current boom of the “sourced” ingredients of imported pizzas has led to an explosion of terroir-toppings in supermarket aisles, from Buffala mozzarella, prosciutto di Parma, fresh basil, and grana, melding the promises of a Neapolitan tradition as if it is able to survive nourished by industrial-scale mass production and shipping processes, feeding Europe frozen pizzas and from 2008-2019 all but doubling the volume of frozen pizza produced in Italy, meeting the pizza market in an odd hybrid blurring local and global that is the essence of globalization, and allowing any spot in the world to “enjoy” pizza of quality “sourced” ingredients, allegedly “raising the qualitative standards of this typical Italian dish” [sic], as Vittorio Gagliardi, President of the Italian Society for Frozen Foods, recently claimed, as if he were presiding over the global diffusion of national food.

The expansion of frozen pizzas perpetuate in supermarket freezer bins the fantasy of “handmade” frozen pizza of sourced ingredients, imported directly from Italy, as attested by a tin of fresh olive oil, ripe tomatoes, and dense blocks of parmesan or grana promising an “Italian taste” imported from the source, and fetishizing the local–even if its crust often tastes like cardboard, and cheese is quite arguably processed, or tastes like it may well be. The attempt to persuade customers of the “local” nature of “Trader Giotto’s” pizza as “handmade.” Four signifiers of signifiers of freshness–unrefined flour; olive oil; fresh cheese; vine grown cherry tomatoes; a sprig of parsley–offer abundant signifiers in a bit of a cunning illusion to persuade consumers of the freshness of store-bought food that is increasingly inscribed in our national terrain and increased online traffic by which we voice preferences and identity. The national landscape of Google Searches remains broadly dominated by “pizza,” although such searches only barely keep up in some sites with the popularity of gun shops and strip clubs, per Floating Sheep: the dominance might not be a sign or measure of social health; indeed, Floating Sheep in 2008 saw some danger in the emergence unique lines of social fracturing–but suggest deep dedication to pizza as a desired local destination.

7. If the tension and deep connection of local to global is the consequence and deepest symptom of globalization, surely the pizza is a prime case for being shaped by globalization’s devious processes. The near-global ubiquity of pizza implicates the dive to link it to one place of birth in space, even if the addition of cheese, oil, pine-nuts, and pepper on a flat round piece of bread features in the first century De re coquinaria, and thermopolia in Pompeii, near Naples, served fresh baked spelt-wheat cakes with olive paste and oil, raising questions of what makes pizza, or how much depends on tomato-based sauce, at times omitted in pizze served hot in modern Italy, or to go–perhaps claims of priority of any American city must be asterisked if not queried. In invention tied to pita, pizza is almost an extension of one’s daily bread, a para-meal or quasi-meal, not born in a restaurant, embellished with anchovies, cured meats, or softer cheeses, treated as a warming sandwich but seems tied to the adoption of tomatoes in the area of Naples and Sicily long before they reached a broader European palate. Who can blame Neapolitans who have long practiced their trade in pizze from looking mournfully into the rear-view mirror of globalization processes, and lament the diffusion of their craft on unexpected global multinational networks? While tangible memories of the improvised art are rare, the premium on place of its making seems a rebuttal of global distribution networks and a restoration of the art of pizza to a cultural patrimony of the past.

The theatrical rekindling of an identified “first pizza oven in Naples in 2017 served to mark it as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The intangible heritage was, at the lighting of the oven, made tangible: if Vico traced the manmade origins in philology, UNESCO affirmed the tacit knowledge of throwing the pizza, and seasoning it with acidic tomatoes and oregano, as well as fresh mozzarella, as an Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity, spontaneously provoked raucous cheers, “viva la pizza Napoletana!” as celebratory slices were distributed in the street. The ceremonial re-kindling of the fire of a pizza oven in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius might be claimed to be analogous to rekindling of the Olympic torch, re-igniting of a transmission of tradition, if not marking the invention a new Olympic torch–as the transmission of the the altar to Hestia at her sanctuary on Mt. Olympus, devised by German philologists for the 1936 Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, after an employee of electric utility company of Amsterdam had lit the flame for the 1928 Summer Olympics. The invention of the transmission of a torch now ignited by concentrating sunlight off a parabolic dish at Olympia’s temple of Hera occurs in time for its relay to the opening ceremony, before it is brought to the site of the global games in an invented tradition of symbolic continuity. If the invention of the torch was an attempt at recreating global harmony after World War I, the re-igniting of the pizza oven in Naples seemed determined to remap global consumption of pizzas with hopes to pin it at its local root.

The confirmation of the intangibility of the heritage of making pizza, the most material of foods, raised eyebrows if not strained credibility, but provoked global smiles. For the preservation of its craft as able to “foster social gatherings and inter-generational exchange” that the Association of Authentic Neapolitan Pizzaiuoli had petitioned, sensing the acute precarity of their craft, not only to promote their claim to train folks in the art of pizza spinning. Stressing pizza as a legacy, more than only a comfort food, argued a local anthropologist, acknowledged the need for pride at the democracy and sustainability (and affordability) of a food prep “invented by multitasking people to survive in a difficult city like Naples, before technology helped us multitask.” Did Neapolitan anthropologist Marino Niola, of the Social Anthropology Laboratory of Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, unintentionally cast Naples as a precursor of globalization in marginal work, suggesting that pizza’s success in ways that fit globalized lifestyles, more than to celebrate the authenticity of the pizza that the Neapolitan Pizzaiuoli had sought to celebrate?

Niola’s words tied pizza to the pressures of globalized work, but was meant to root it in pressures of work. The need of multi-tasking while eating is a scary justification for eating pizza–one hand on one’s phone. Something else was at work in this ceremonial declaration. Requesting UNESCO certify an oven acclaimed as the site of pizza’s birth asserted a point of civic pride, affirming dignity after New York’s “little Italy” posted a plaque claiming pizza’s ‘invention’–the specificity of the local dialect–pizzaiuolo–affirmed the longstanding local legitimacy the global food of pizza had long enjoyed. Although few pizza makers are of Italian heritage in a globalized world, lighting this oven was as primal as the flame of a Statue of Liberty, affirming a local legacy as a contribution to nation, and to the globe: the flame of the local wood-fired pizza oven is where the magical alchemical transformation of the flour, mozzarella, and tomato, in fact began.

The Neapolitan pizza oven where dough bakes for a few minutes at 700-900º F is a quasi-sacred site exclusively built from Neapolitan earth out of brick, at a temperature to allow the rapid ritual scarification of dough.

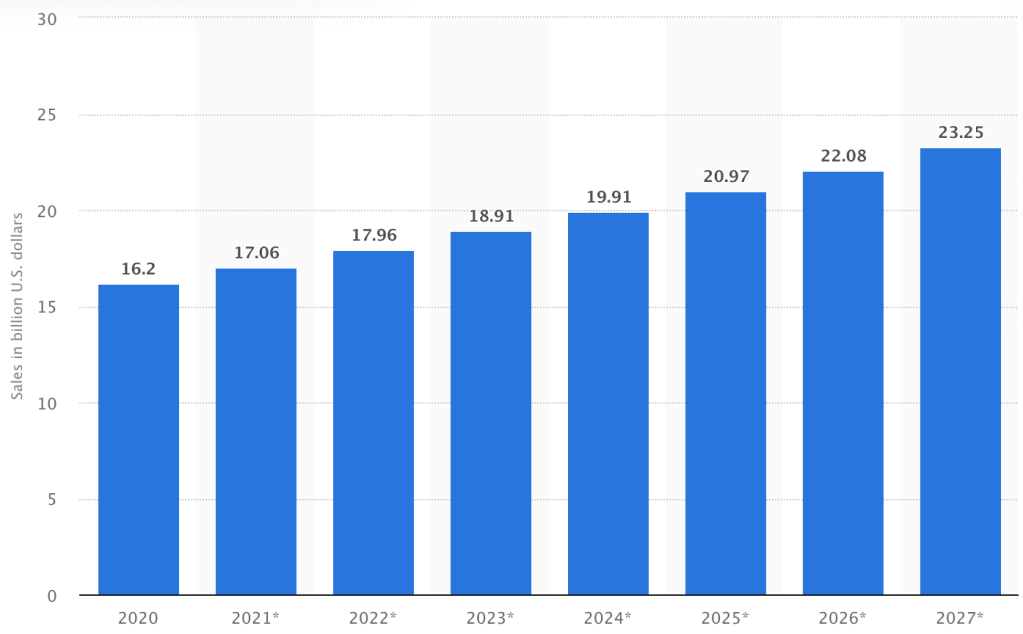

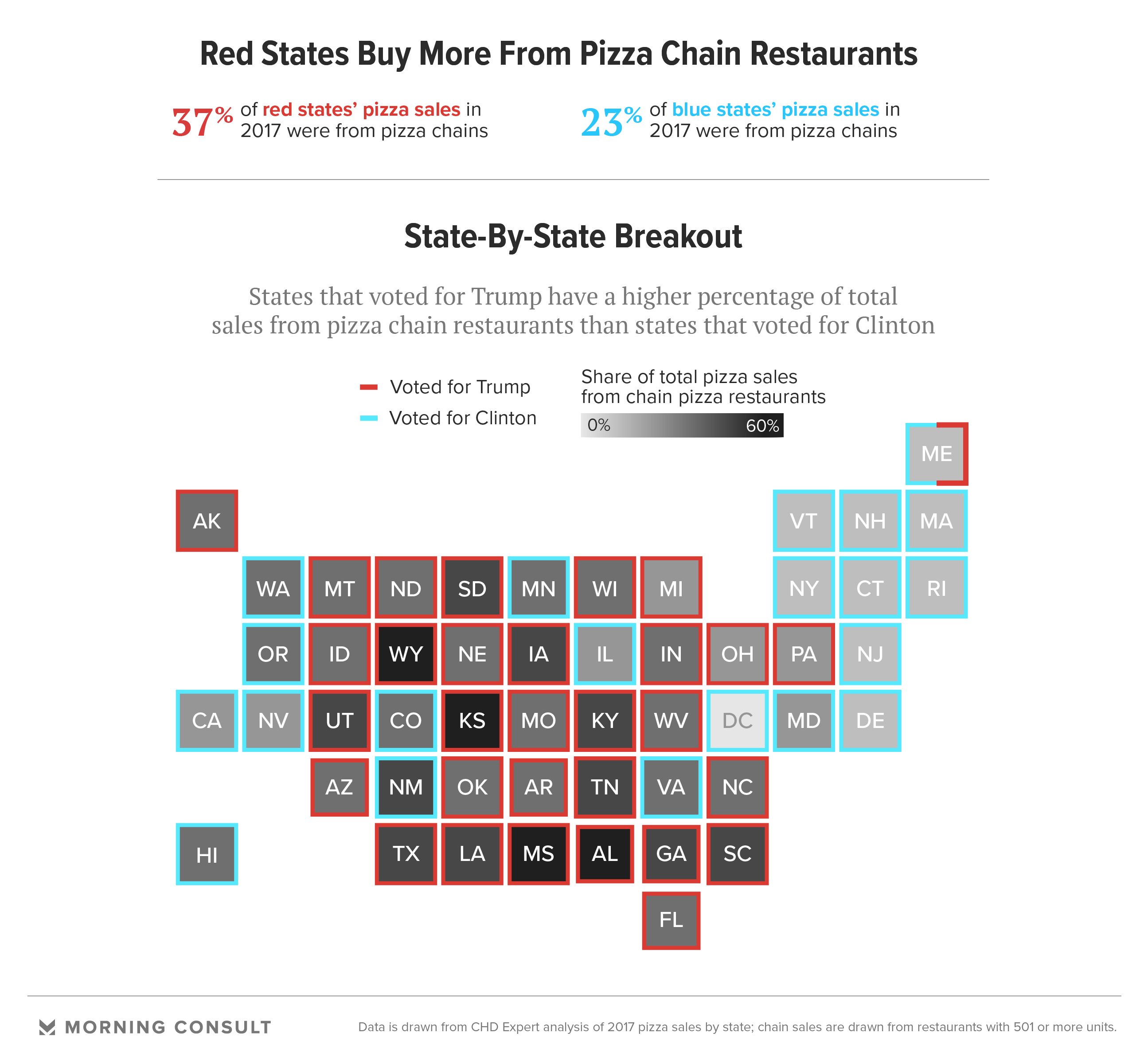

We await a true material history of the twentieth-century artifact of pizza, whose late twentieth century revival has extended from the consolation of the Occupy movement to the pandemic deliveries. The rise of pizza as a global food is mirrored in the dominance that Europe retained in the global pizza industry, narrowly larger than the United States, who together held 70% of pizza sales, with France contributing a large share; the rise of “fast casual” chains in the United States challenged the traditional pizzaiuolo, and barely made a dent in the growth of pizza as a fast food, as independent pizzerias suffered a shrinking market from around 2015, suggesting a new wrinkle in the globalization of pizza as a prepared food and growth of thin crust frozen pizza for a global market, dominated by North America–prompting much investment by multinationals in the development of frozen pizza. North America and Europe dominate the global pizza box market, online food delivery has expanded worldwide, saturating the globe largely courtesy pizza chains, which have displaced independents. The problem of the recent regional saturation of pizza markets on a global scale finds Italy to be quite saturated, to be sure, at 1,500/pizzeria, with Domino’s, Pizza Hut, and Little Caesars and Papa Johns claiming 79% of the top pizza chains, with arguably the worst–Pizza Hut–claiming half the sales of chains, raising fears lest pizza tastes be forgotten its cultural heritage indeed merits protection. And if the lions share of consumers are preteens, or twice the national average, the greater pizza sales from chains globally suggests that most of that pizza is not made fresh.

8. The ages of the pizza’s making metamorphosed through the expansion of chains in east coast states, from 1970–around the very time that new standards on processed cheese were introduced in America–merit an archeology across space and time, along transatlantic arcs, until the new recognition of present anointing of pizza-making as a patrimony as much as a craft. By the 1980s, the survival of independent pizzerias and deliveries was boosted by the growth of national chains like Domino’s and Pizza Hut, leading to the acquisition of Tombstone by Kraft Foods, and also high end frozen pies: high sales in Milwaukee, Chicago and New York in the 1990s led to a proliferation of brands. 1990 saw a need for a guide to the go-to family meal, and as “consumption” of sausage and peppers, pepperoni, and cheese pizza became a food for kids to “cook” in kitchen ovens, Americans ate a pie every six weeks. Able to be warmed in gas ovens at 375 or microwaves, consumed with the addition of additional toppings, the flooding of supermarkets with frozen pizzas occasioned a high-end guide to their discrimination, in an almost comic connoisseurship; Florence Fabricant ranked fifteen options from diet to high-end pizza, advertising “real cheese” outliers: many were bland or but decent, some distinguished by savory herbs or tomato, others only by soggy crust.

Is it really the same mozzarella, crust, and tomato sauce? Two years after Fabricant had ranked the quality frozen pizza, illustrator Ed Koren riffed on the ubiquity of frozen pizza’s dubious popularity in an alternative fairy tale for the time: “Once upon a time, there was a frozen pizza, and inside that frozen pizza some very bad monsters lived . . .” Was the worst offender not processed cheese, reconstituted tomato, or refined flour, but pepperoni?

7. Has pizza come to be emblematic, ironically for a fresh baked food, emblematic of the distance of the food producers from the calories of food consumers eat?

Fed by fury of food tourism and the media frenzy that frames history as a genealogy running on clear lines of descent and inheritance, rather than reinvention, that leads to the hopes of spatially pinning pizza’s site of invention. But the figure of authenticity seems a sign of the need for pinning down the global saturation of the pizza market on a map, or a symptom of the hope to pin a site of primacy in a sea of tastes, to claim a privileged place in an ever expanding market for what is now a decidedly global food–despite the flourishing in some coastal American cities of private pizza stores. The growth of global sales, dominated by pizza chains, has led to a global ubiquity of the pie, slice, and over the local, tied to urban growth, which has led us to look in rear-view mirror at the origins of pizza, or hope for the perseverance of the local, where sales are dominated by proliferating pizza chains, volume of sales largest for Domino’s, Pizza Hut, Little Caesar’s and Papal John’s makes many yearn for local varieties of cheese, not to mention seasonal additions–fresh tomatoes or arugula–enhanced by anything from sprigs of basil, exotic truffles or sparing amounts of quality freshly-pressed grassy olive oil that place the pizza on a genealogy of farm-to-table freshness. And as the pizza market rises, as Derek Thompson has found, perhaps more surprisingly, those who are eating pizza tend to rely on them for about a quarter of their share of their calories–on days they order or consume them. As pizza becomes a more and more readily accessible source of energy, even if kids younger than twenty–Thompson found that more than a full quarter of boys between ages 9 and 16 are eating pizza each day in the United States–the caloric heft of the pizza is pretty evenly distributed among its consumers.

9. If pizza has become the favored to go food globally, in correlation in a global economy, it was long tied to low overheads, long before abundant cheap pre-shredded cheese and canned tomatoes, and the postwar rise of disposable income as much as currents of migration.

To be sure, Neapolitans have since asserted transformation of their long-appreciated food as Italian food as an echo of the national tricolor. The much recited myth, which I first heard at a pizza table outside Munich, and is often repeated in oral culture, offers the celebrates the symbolic tricolore of Pizza Margherita as a creation at a precise date, 1889, when a local pizzaiuolo ascended to at the command of the new King of Italy, Umberto I, and his bride, Regina Margherita, to present them with pizzas of his own design: if the legend celebrated the pizza in a narrative of national memory, it made the Savoian monarch, formerly Umberto IV of Savoy, and his consort to a true King of Italy, recognizing the primacy of pizza to French tastes. If pizza pies were ‘postwar’ in America, the elevation of the pizza to a myth of national foundation suggests a conjuring of national belonging that elevated the art: American travelers could not contain revolt at Neapolitan street food in 1831 at “the most nauseating cake … covered over with slices of pomodoro or tomatoes, and sprinkled with little fish and black pepper” which “looks like a piece of bread that has been taken reeking out of the sewer.” The popular pie was elevated to something “Italian” when, legend had it, a local fabricator of pizza–the pizzaiuolo Raffaele Esposito, summoned from his pizzeria on via Chiaia–and the frog was kissed by the princess who ate it with gusto and pleasure. Esposito, legend has it, in a moment of sprezzatura presented three distinct varieties of the street food to the visiting monarchs–one with lard and cheese curds; one with sardines; one tomato, mozzarella, and basil sprigs–the least heavy of which quite appealed to northerners long habituated to French food.

The delicate three-color now known on pizza boxes’ graphic design is a slightly more elegant–and lighter–version of pizza, allegedly invented for Savoiard monarchs visiting a region they were loathe to reform, but at this point eager to impose a systematic campaign of Risanamento as they had arrived to initiate a program of broadening Naples’ streets by a demolition of older buildings in hopes to mitigate and contain an infestation of cholera in poorer neighborhoods of the city, spreading (or thought to be spreading) in stagnant water in the city’s open sewers, as well as showing sympathy by visiting hospitals and clinics. Did not appreciation of the pizza that this pizzaiolo presented present evidence affirming the northerners’ deep local affective ties to the south? Perhaps pizza brought some marginal satisfaction while trying to control the epidemic’s contagion, or to appease local incomprehension of the program of urban destruction that the monarchs arrived to promote. It certainly seemed to consolidate Naples’ ties to Italy as an idea.

The legend of royal recognition Regina Margherita bestowed on the lower class bread, legend has it, led the pizza to spread to America–“Interestingly, if the queen didn’t venture to try this “peasant bread,” then pizza may never have spread to become the global phenomenon it is today” runs the myth diffused online. The choice of the pizza is given a foundational status as a royal choice and mandate, akin to historical paintings theatrically glorify the encounter of Umberto I and Garibaldi at Teanno as marking the integration of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies into a Kingdom of Italy–often twinned to the legend akin to that during the American and French occupation of Italy during World War II by the global appeal of pizza was set in motion.

was embellished, as it happens, after news of the success of Neapolitan pizzaiuoli enjoyed in America grew, the royal recognition of Pizza Margherita but provided a nice spin to affirm the primacy of pizza-making as an eminently local tradition as it was being reinvented across the Atlantic, by the 1930s.

The mythical elevation of the name of the pizza alla mozzarella to pizza Margherita was akin to new recognition of national unity. It conjured imagined lineages of distinction for the pizza pie of the trecolore, a food notably absent from Artusi’s guide to eating well; it served as a Neapolitan contribution to the project of “making Italians” compensating for the limited involvement of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the Risorgimento: as the menus printed for meals of the house of Savoy continued to be printed in French until 1908, it is unlikely arrival of a local pizza prompted Umberto I and Margherita to celebrate a popular dish absent from formal cookbooks, eaten in the poorest of Neapolitan neighborhoods, “a dense dough that burns but does not cook, and is covered with almost-raw tomatoes, with garlic, with oregano, with pepper” previously sold as street food, as Matilde Serao dubiously described in 1884 as often covered with flies. To be sure, the lack of a recipe for pizza lay in secrets contained in the skill of throwing and spinning out of the dough–flour and water, before laying acidic tomatoes and cheese on its surface; if the absent recipe indeed allowed considerable future mobility of pizza-making, it might be a reason for the poor definition of IP or credit for a pizza whose provenance was long undefined–tif it was long the food preferred food of food scarcity. It is the most likely reason for the injustice, perceived by the Neapolitan anthropologist Niola, of a loss of local “rights” even after having “invented one of the best comfort foods of history,” a global wrong.

The need to consolidate the relation of the royal family to the nation was a serious issue, and perhaps pizza had filled in as a lingua franca for a court that did not speak Italian–Victor Emmanuel II entered Rome in 1870, preferred French; declared Padre della Patria, the public visibility of the monarch and his family worked to create a symbolic relation to the nation by deploying various national myths. Among them, it is not clear what sort of place is occupied by the expansion of the rich tradition of Italian local histories to date fabrication of the first Pizza Margherita in Naples to 1889, when a solely sauce and fresh basil leaves held pride of place among the three varieties hand-crafted for the visit of King Umberto I and his Savoian consort Margherita, on their visit to a Naples afflicted by a violent epidemic of cholera. The arrival of a local pizzaiolo, the mythic hero Raffaele Esposito, is credited with designing three pizzas delivered to Capodimonte that prompted the recognition scene: Queen Margherita abandoned the culinary pretense of the House of Savoy by embracing the pleasure of southern Italian tomato sauce, as if to acknowledge her truly national palate with gusto. While the mythic 1889 visit may be a falsification–the letter that claims to have given royal blessings to the pizza shop of Esposito, now Brandi, is datable to circa 1935, as Nowak has conclusively demonstrated–the rumor of a Queen who had already in 1880 had allegedly “deeply desired to eat like the poor people” raises questions of how she negotiated pizza with her renowned jewelry and pearls.

The considerable appeal of pizza as a passport to transcend class divides that cemented the nation cannot be denied, nor of pizza as a type of royal obeisance. The legends of promoting popolano food of the city slums he was remaking has led historians to posit that the recognition of pizza was a political ploy–a royal sign of contact with a populace of which Umberto I was uncertain of loyalty or affection,–“a purely political initiative” in a city where ten years ago he survived stabbing by an anarchist, whose neighborhoods he was destroying. But the sense of the moment that Raffaele Esposito already petitioned to rename his pizzeria as the “Pizzeria della Regina d’Italia” (“Pizzeria of the Queen of Italy”) in 1883, before the royal visit, is described in local police records as operating “under the sign of ‘Pizzeria of the Queen of Italy’”–he was a purveyor of wines to the royal house, whose father in law provided pizza in 1880 to Margherita. But the very three-color pizza he is argued to have improvised for the occasion is described without special comment in 1853; in the service to the nation, Gentilcore speculates, the “invented tradition” was re-invented as one that Italianized local street food by investing a popular food a noble pedigree, that fit even the elevated tastes of Piedmontese accustomed French cuisine.

There is a pleasure in celebrating the sprezzatura of a mythic pizzaiolo, Raffaelle Esposito, whose spinning and fantasy found favor with the Savoyard palate after he presented King and Queen with three pizzas in the Capodimonte palace. As much as seeing pizza as a social passport to a scala mobile for immigrants, it is lovely to imagine pizza as a social lubricator, able to bridge the Savoyard tastes for fondues, raclettes, sea bass with cream sauce, boned roast quail stuffed with truffles and fois gras, using exclusively white truffles from their estates, and veal and asparagus; it is hard to know how she would have tasted the pizza with no cheese, if it seemed elegant enough for a discriminating French palate on her alleged 1889 visit. There is considerable appeal of seeing the pizza as a form of social ascension on the scala mobile unthinkable in earlier times–perhaps a mythic precursor to the elevation of pizza as a food now prominent in recipe books and restaurants worldwide–but it is more likely that Margherita was conscious of her dominant duties of making the royal house popular throughout the peninsula.

The myth is potent. The invention of Margherita’s pleasure for the populist pizza confirmed the unity of Italy, or perhaps it defined a food that won success abroad as in fact Italian al the time–if perhaps the true contribution of Naples and Sicily to Italianità was the tomato sauce added to grano duro pasta first by Neapolitans–and Sicilians–from the 1830s. Perhaps the myth of tasting three pizza pies in Capodimonte Palace is telling: that royal palace had been quite strategically chosen as the site where the queen had given birth to Umberto I’s successor in 1869 as symbolic of the unity of the country. We have no real evidence that the queen ever summoned a pizzaiolo to the palace to provide her some reassurance during the infestation of a cholera epidemic that wracked the city in 1883, the date noted on the forged seal attached to a purported royal thank you note the Queen sent, still surviving on the wall in a Neapolitan pizzeria to this day, that claims to be descended Raffaello’s pizza store on via Chiaia–an inspired forgery from the economic downturn of the 1930s. While we have continued to cherish the legend of Margherita’s love of the tricolor pizza with mozzarella, tomato sauce, and basil, the letter was devised not by descendants who had inherited the Pizzeria Brandi in order to boost business at what they had already named the “Pizzeria della Regina d’Italia,” elevating the status of the popolano food. (Around the same time, Carmine Caputo had returned from America to Naples to found the mill of “traditional” “00” four that would distinguish Neapolitan pizza.) Is it possible that the competition of the emigrated Neapolitans as celebrated pizza-makers in America in fact inspired the affixing of the fraudulent certificate claiming a Neapolitan pizza was the “site” of pizza’s classic preparation?

By the time the letter was forged, indeed, it might have helped that Margherita’s son, Victor Emmanuel III, complicit with fascism, named Mussolini Prime Minister after the 1922 March on Rome, making the legend of the queen’s taste for pizza an appealingly patriotic figure to promote to the nation and National Fascist Party, Victor Emmanuel III depicted on all coins and bills of the new currency paired with an sheaf of wheat–and ears of wheat were bound as a fasces that were ceremonially held by famers, as lectors, affixed with a photograph of the Duce Mussolini.

Is there a hidden episode of the championing of the popular food as a royal selection in the dating of the forgery to the era of Fascist Italy, and the newfound celebration of the grano duro as a tie to the land?

Was the canonization of the pizza Margherita imagined to be the favorite of the mother of the current King of Italy, later Emperor of Ethiopia and King of the Albanians, a way to distinguish the imagined ties the pizzeria that by 1883 already assumed the tile of “Pizzeria of the Queen of Italy”? The tastes of the House of Savoy were less important than the special nature of the dish. In the aftermath of out-migration, did Neapolitan pizzaiuoli seek to affirm the symbolic primacy of their city as the nerve center of the transmission of pizza-making traditions by displaying the alleged royal benediction, to suggest the city’s contribution to the birth of the nation?

9. While the promotion of pizza in the fascist era is unclear, the outmigration was a consequence of global appetite during the postwar, fueled by the American Agriculture Act of 1949 that helped subsidize cheese production in the United States, expanding cheese production by the 1950s–and the rise of shredded cheeses with the foundation of the largest cheese processing plants by the 1960s, and their expansion from the 1970s in America’s old dairy lands. If Wisconsin’s cheese production skyrocketed to 561 million pounds by 1950, in a foretaste of the current use by Pizza Hut of 300 million pounds of cheese for the pizza it sells in the United States. If pizza grew in Italian-American communities as an emigre food in Boston, New York, Trenton, and New Haven, the result was a new meaning of pie.

Born or reborn in America as a food readily tied to car culture, disposable income, and their ease of assembly, pizzerias exploded across the Northeast after the 1970s, they were rarely in restaurants. Most relied on steel ovens, and to go cartons, as a cheap meal on the run, emulating the Neapolitan street food in a classier manner. But perhaps we have focussed entirely too much on the authenticity of the sauce, and San Marzano, as Jacques Derrida–fond to take his philosophy seminars out for a pizza–might remind us, while neglecting the toppings, whose addition as much as adding spice promised the very sort of cheap novelties gave the pizza global legs: the addition in Italian American butcher shops or pizza stores of pepperoni, that supremely Italo-American invention, the pizza slice has emerged as a to-go food made in gas ovens and cut into triangular slices whose vegetable oil coating lent an unforgettable glisten to how shredded cheese evenly spread as it melted in webs across the surfaces of the slice.

The relative ease and the mobile ingredients of pizza-making gave it legs, however, that, in the land of food delivery, disposable income, rotary ovens and shredded cheese gained legs able to obscure awareness of its Italian origins. The pizza pie was defined by it ties to its terrain or audience, be they royal or local, but might morph in identity and spread in place and across space, its surface welcoming pancetta and pineapple, in the modern “rotating ovens” first patented as wider ovens of rotating shelves, for baking in the 1936, perfected postwar, when a 1953 patent transformed the pizza by removing baking from the earlier art that had long relied on a burst of intense heat–if not at first designed for pizza, in 1949, that a Chicago oven maker won after his death in 1953–Patent No. 2,650,554—that would in short order change the course of pizza history, just a decade before \Kenner Products in Cincinnati, Ohio introduced their Easy-Bake Oven heated at home by two 100-watt incandescent bulbs.