American President Donald Trump claimed that his attempt to prevent visitors from seven countries entering the United States preserved Americans’ safety against what was crudely mapped as “Islamic terror” to “keep our country safe.” Trump has made no bones as a candidate in calling for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims” as among his most important priorities if elected President. The map the he has asked the nation to draw about who can enter the country–purportedly because they are “terrorist-prone” nations–a bizarre shorthand for countries unable to protect the United States from terrorism–as if this would guarantee greater safety within the United States. For as the Department of Homeland Security affirmed a need to thwart terrorist or criminal infiltration by foreign nationals, citing the porous borders of a country possessing “the world’s most generous immigration system” that has been “repeatedly exploited by malicious actors,” and located the dangers of terror threats from outside the country as a subject for national concern, provoking anxiety by its demonization of other states as national threats. And even though the eagerly anticipated “ban” lacks “any credible national security rationale” as governmental policy, given the problem of linking the radicalization of any foreign-born terrorist or extremists were only radicalized or identified as terrorists after having become Americans, country of citizenship seems an extremely poor prognostic or indicator of who is to be considered a national danger.

Such eager mapping of threats from lands unable to police emigration to the United States oddly recall Cold War fears of “globally coordinated propaganda program” Communist Parties posing “unremitting use of propaganda as an instrument for the propagation of Marxist-Leninist ideology” once affirmed with omniscience in works as Worldwide Communist Propaganda Activities. Much as such works invited fears for the scale and scope of Communist propaganda “in all parts of the world,” however, the executive order focusses on our own borders and the borders of selective countries in the new “Middle East” of the post-9/11 era. The imagined mandate to guard our borders in the new administration has created a new eagerness to map danger definitively, out of deep frustration at the difficulty with which non-state actors could be mapped. While allegedly targeting nations whose citizens are mostly of Muslim faith, the ban conceals its lack of foundations and unsubstantiated half-truths.

The renewal of the ban against all citizens of six countries–altered slightly from the first version of the ban in hopes it would successfully pass judicial review, claims to prevent “foreign terrorist entry” without necessary proof of the links. The ban seems intended to inspire fear in a far more broad geography, as much as it provides a refined tool based on separate knowledge. Most importantly, perhaps, it is rigidly two-dimensional, ignoring the fact that terrorist organizations no longer respect national frontiers, and misconstruing the threat of non-state actors. How could such a map of fixed frontiers come to be presented a plausible or considered response to a terrorist threats from non-state actors?

1. The travel ba focus on “Islamic majority states” was raised immediately after it was unveiled and discourse on the ban and its legality dominated the television broadcasting and online news. The suspicions opened by the arrival from Wall Street Journal editor-in-chief Gerard Baker that his writers drop the term “‘seven majority-Muslim countries'” due to its “very loaded” nature prompted a quick evaluation of the relation of religion to the ban that the Trump administration chose at its opening salvo in redirecting the United States presidency in the Trump era. Baker’s requested his paper’s editors to acknowledge the limited value of the phrase as grounds to drop “exclusive use” of the phrase to refer to the executive order on immigration, as if to whitewash the clear manner in which it mapped terrorist threats; Baker soon claimed he allegedly intended “no ban on the phrase ‘Muslim-majority country’” before considerable opposition among his staff writers–but rather only to question its descriptive value. Yet given evidence that Trump sought a legal basis for implementing a ‘Muslim Ban’ and the assertion of Trump’s adviser Stephen Miller that the revised language of the ban might achieve the “same basic policy outcome” of excluding Muslim immigrants from entering the country. But curtailing of the macro “Muslim majority” concealed the blatant targeting of Muslims by the ban, which incriminated the citizens of seven countries by association, without evidence of ties to known terror groups.

The devaluation of the language of religious targeting in Baker’s bald-faced plea–“Can we stop saying ‘seven majority Muslim countries’? It’s very loaded”–seemed design to disguise a lack of appreciation for national religious diversity in the United States. “The reason they’ve been chosen is not because they’re majority Muslim but because they’re on the list of countRies [sic] Obama identified as countries of concern,” Baker opined, hoping it would be “less loaded to say ‘seven countries the US has designated as being states that pose significant or elevated risks of terrorism,'” but obscuring the targeting and replicating Trump’s own justification of the ban–even as other news media characterized the order as a “Muslim ban,” and as directed to all residents of Muslim-Majority countries. The reluctance to clarify the scope of the executive order on immigration seems to have disguised the United States’ government’s reluctance to recognize the nation’s religious plurality, and unconstitutionality of grouping one faith, race, creed, or other group as possessing lesser rights.

It is necessary to excavate the sort of oppositions used to justify this imagined geography and the very steep claims about who can enter and cross our national frontiers. To understand the dangers that this two-dimensional map propugns, it is important to examine the doctrines that it seeks to vindicate. For irrespective of its alleged origins, the map that intended to ban entrance of those nations accused without proof of being terrorists or from “terror-prone” nations. The “Executive Order Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” defended as a legal extension of the President’s “rightful authority to keep our people safe,” purported to respond to a crisis in national security. The recent expansion of this mandate to “keep our people safe” against alleged immanent threats has focused on the right to bring laptops on planes without storing them in their baggage, forcing visitors form some nations to buy a computer from a Best Buy vending machine of the sort located in airport kiosks from Dubai to Abu Dhabi, on the grounds that this would lend greater security to the nation.

2. Its sense of urgency should not obscure the ability to excavate the simplified binaries that justify its imagined geography. For the ban uses broad brushstrokes to define who can enter and cross our national frontiers that seek to control discourse on terrorist danger as only a map is able to do. To understand the dangers that this two-dimensional map proposes, one must begin from examining the unstated doctrines that it seeks to vindicate: irrespective of its alleged origins, the map that intended to ban entrance of those nations accused without proof of being terrorists or from “terror-prone” nations. The “Executive Order Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” defended as a legal extension of the President’s “rightful authority to keep our people safe,” purported to respond to a crisis in national security. The recent expansion of this mandate to “keep our people safe” against alleged immanent threats has focused on the right to bring laptops on planes without storing them in their baggage, on the largeely unsubstantiated grounds that this would lend greater security to the nation.

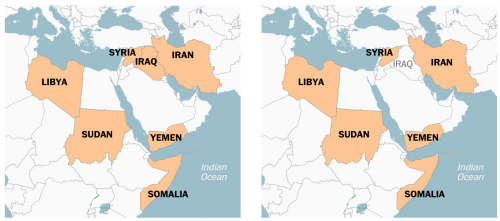

The lack of compunction to attend to the religious plurality of the United States citizens bizarrely date such a purported Ban, which reveals a spatial imaginary that run against Constitutional norms. In ways that recall exclusionary laws based on race or national origin from the early twentieth century legal system, or racial quotas Congress enacted in 1965, the ban raises constitutional questions with a moral outrage compounded as many of the nations cited–Syria; Sudan; Somalia; Iran–are sites from refugees fleeing Westward or transit countries, according to Human Rights Watch, or transit sites, as Libya. The addition to that list of a nation, Yemen, whose citizens were intensively bombed by the United States Navy Seals and United States Marine drones in a blitz of greater intensity than recent years suggests particular recklessness in bringing instability to a region’s citizens while banning its refugees. Even in a continued war against non-state actors as al Qaeda or AQAP–al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula–the map of Trump’s long-promised “Islamic Ban” holds sovereign boundaries trump human rights or humanitarian needs.

The ban as it is mapped defines “terror-prone regions” identified by the United States will only feed and recycle narratives of western persecution that can only perpetuate the urgency of calls for Jihad. Insisting national responsibility preventing admission of national citizens of these beleaguered nations placed a premium on protecting United States sovereignty and creates a mental map that removes the United States for responsibility of military actions, unproductively and unwarrantedly demonizing the nations as a seat of terrorist activity, and over-riding pressing issues of human rights tied to a global refugee crisis. But the mapping of a ban on “Foreign Terrorist Entry” into the United States seems to be something of a dramaturgical device to allege an imagined geography of where the “bad guys” live–even a retrograde 2-D map, hopelessly antiquated in an age of data maps of flows, trafficking, and population growth, provides a reductive way to imagine averting an impending threat of terror–and not to contain a foreign threat of non-state actors who don’t live in clearly defined bounds or have citizenship. Despite an absolute lack of proof or evidence of exclusion save probable religion–or insufficient vetting practices in foreign countries–seems to make a threat real to the United States and to magnify that threat for an audience, oblivious to its real effects.

For whereas once threats of terror were imagined as residing within the United States from radicalized regions where anti-war protests had occurred, focussed on Northern California, Los Angeles, Chicago, and the northeastern seaboard and elite universities–and a geography of home-grown guerrilla acts undermining governmental authority and destabilizing the state by local actions designed to inspire a revolutionary “state of mind,” which the map both reduced to the nation’s margins of politicized enclaves, but presented as an indigenous danger of cumulatively destabilizing society, inspired by the proposition of entirely homegrown agitation against the status quo:

Unlike the notion of terrorism as a tactic in campaigns of subversion and interference modeled after a revolutionary movement within the nation, the executive order located demons of terror outside the United States, if lying in terrifying proximity to its borders. The external threats call for ensuring that “those entering this country will not harm the American people after entering, and that they do not bear malicious intent toward the United States and its people” fabricate magnified dangers by mapping its location abroad.

2. The Trump administration has asserted a need for immediate protection of the nation, although none were ever provided in the executive order. The arrogance of the travel ban appears to make due on heatrical campaign promises for “a complete and total ban” on Muslims entering the United States without justification on any legitimate objective grounds. Such a map of “foreign terrorists” was most probably made for Trump’s supporters, without much thought about its international consequences or audience, incredible as this might sound, to create a sense of identity and have the appearance of taking clear action against America’s enemies. The assertion that “we only want to admit people into our country who will support our country, and love–deeply–our people” suggested not only a logic of America First, but seemed to speak only to his home base, and talking less as a Presidential leader than an ideologue who sought to defend the security of national boundaries for Americans as if they were under attack. Such a verbal and conceptual map in other words does immense work in asserting the right of the state to separate friends from enemies, and demonize the members of nations that it asserts to be tied to or unable to vet the arrival of terrorists.

The map sent many scrambling to find a basis in geographical logic, and indeed to remap the effects of the ban, if only to process its effects better.

But the broad scope of the ban which seems as if it will have the greatest effect in alienating other nations and undermining our foreign policy, as it perpetuates a belief in an opposition between Islam and the United States that is both alarming and disorienting. The defense was made without justifying the claims that he made for the links of their citizens to terror–save the quite cryptic warning that “our enemies often use our own freedoms and generosity against us”–presumes that the greatest risks not only come from outside our nation, but are rooted in foreign Islamic states, even as we have been engaged for the past decade in a struggle against non-state actors. In contrast to such ungratefulness, Trump had repeatedly promised in his campaign to end definitively all “immigration from terror-prone regions, where vetting cannot safely occur,” after he had been criticized for calling during the election for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” until they could “figure out what is going on.”

But the targeted audience was always there, and few of his supporters were likely to have forgotten the earlier claims–and the origins of this geographical classification of national enemies terrifying that offers such a clear dichotomy along national lines. While pushed to its logical conclusion, the ban on travel could be extended to the range of seventy-odd nations that include a ban against nations associated with terrorism or extremist activity–

–but there is a danger in attributing any sense of logical coherence to Trump’s executive order in its claims or even in its intent. The President’s increasing insistence on his ability to instate an “extreme vetting” process–which we do not yet fully understand–seems a bravado mapping of danger, with less eye to the consequences on the world or on how America will be seen by Middle Eastern nations, or in a court of law. The map is more of a gesture, a provocation, and an assertion of American privilege that oddly ignores the proven pathways of the spread of terrorism or its sociological study.

But by using a broad generalization of foreign nations as not trustworthy in their ability to protect American interests to contain “foreign terrorists”–a coded generalization if there ever was one–Trump remapped the relation of the United States to much of the world in ways that will be difficult to change. For in vastly expanding the category “foreign terrorists” to the citizens of a group of Muslim-majority nations, he conceals that few living in those countries are indeed terrorists–and suggests that he hardly cares. The executive order claims to map a range of dangers present to our state not previously recognized in sufficient or honest ways, but maps those states in need as sites of national danger–an actual crisis in national security he has somehow detected in his status as President–that conceal the very sort of non-state actors–from ISIS to al-Qaeda–that have targeted the United States in recent years. By enacting a promised “complete and total ban” on the entry of Muslims from entering the nation sets a very dangerous precedent for excluding people from our shores. The targeting of six nations almost exemplifies a form of retributive justice against nations exploited as seats of terrorist organizations, to foment a Manichean animosity between majority Muslim states and the United States–“you’re either with us, or you’re against us”–that hardly passes as a foreign policy map.

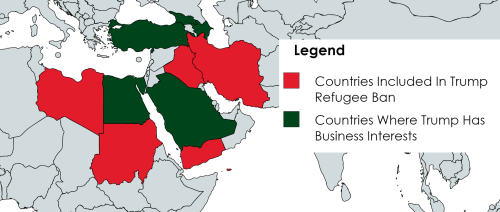

Rather than respecting or prioritizing human rights, the identification of Islam with terrorist organizations seems the basis for excluding citizens and nationals of seven nations who might allow “foreign terrorist entry.” The ban was quickly noted that the list of nations pointedly excluded those where Trump did or pursued business as a businessman and hotelier. But while not acknowledging this distinction, it promotes a difference between “friend” and “enemy” as a remapping of threats to the nation along national lines, targeting nations not only as suspicious sites of radicalization, but by collectively prohibiting their residents and nationals from entry to the nation. While it is striking that President Jimmy Carter had targeted similar states identified as the nations that “have repeatedly provided support for acts of international terrorism” back in 1980–President Carter cited the long-unstable nations of Iraq, Libya, South Yemen, and Syria, following then-recent legislation indicating their abilities “support acts of international terrorism.” The near-identical mapping of terror does not exemplify an egregious instance of “mission creep,” but by blanketing of such foreign nationals as “inadmissible aliens” without evidence save “protecting the homeland” suggests an unimaginable level of xenophobia–toxic to foreign relations, and to anyone interested in defending national security. It may Israeli or Middle Eastern intelligence poorly mapped the spread of growing dangers.

But it echoes strikingly similar historical claims to defend national security interests have long disguised the targeting of groups, and have deep Cold War origins, long tied to preventing entrance of aliens with dangerous opinions, associations or beliefs. It’s telling that attorneys generals in Hawai’i and California first challenged the revised executive order–where memories survives of notorious Presidential executive order 9006, which so divisively relocated over 110,000 Japanese Americans to remote areas, the Asian Exclusion Act, and late nineteenth-century Chinese Exclusion Act, which limited immigration, as the Act similarly selectively targets select Americans by blocking in unduly onerous ways overseas families of co-nationals from entering the country, and establishes a precedent for open intolerance of the targeting the Muslims as “foreign terrorists” in the absence of any proof.

The “map” by which Trump insists that “malevolent actors” in nations with problems of terrorism be kept out for reasons of national security mismaps terrorism, and posits a false distinction among nation states, but projects a terrorist identity onto states which Trump’s supporters can take satisfaction in recognizing, and delivers on the promise that Trump had long ago made–in his very first televised advertisements to air on television–to his constituents.

from Donald Trump’s First Campaign Ad (2016)

from Donald Trump’s First Campaign Ad (2016)

Such claims have been transmuted, to members of a religion in ways that suggest a new twist on a geography of terror around Islam, and the Trump’s bogeyman of “Islamic terror.” Although high courts have rescinded the first version of the bill, the obstinance of Trump’s attempt to map dangers to America suggests a mindset frozen in an altogether antiquated notion of national enemies. Much in the way that Cold War governments prevented Americans from travel abroad for reasons of “national security,” the rationale for allowing groups advocating or engaging in terrorist acts–including citizens of the countries mapped in red, as if to highlight their danger, below–extend to a menace of international terrorism now linked in extremely broad-brushed terms to the religion of Islam–albeit with the notable exceptions of those nations with which the Trump family has conducted business.

The targeting of such nations is almost an example of retributive justice for having been used as seats of terrorist organizations, but almost seek to foment a Manichean animosity between majority Muslim states and the United States, and identify Islam with terror– “you’re either with us, or you’re against us“–that hardly passes as a foreign policy map. The map of the ban offers an argument from sovereignty that overrides one of human rights.

3. It should escape no one that the Executive Order on Immigration parallels a contraction of the provision of information from intelligence officials to the President that assigns filtering roles of new heights to Presidential advisors to create or fashion narratives: for as advisers are charged to distill global conflicts to the dimensions of a page, double-spaced and with all relevant figures, such briefings at the President’s request give special prominence to reducing conflicts to the dimensions of a single map. Distilled Daily Briefings are by no means fixed, and evolve to fit situations, varying in length considerably in recent years accordance to administrations’ styles. But one might rightly worry about the shortened length by which recent PDB’s provide a means for the intelligence community to adequately inform a sitting President: Trump’s President’s Daily Briefing reduce security threats around the entire globe to one page, including charts, assigning a prominent place to maps likely to distort images of the dangers of Islam and perpetuated preconceptions, as those which provide guidelines for Border Control.

In an increasingly illiberal state, where the government is seen less as a defender of rights than as protecting American interests, maps offer powerful roles of asserting the integrity of the nation-state against foreign dangers, even if the terrorist organizations that the United States has tired to contain are transnational in nature and character. For maps offer particularly sensitive registers of preoccupations, and effective ways to embody fears. They offer the power to create an immediate sense of territorial presence within a map serves well accentuate divides. And the provision of a map to define how the Muslim Ban provides a from seven–or from six–countries is presented as a tool to “protect the American people” and “protecting the nation from foreign terrorist entry into the United States” offers an image targeting countries who allegedly pose dangers to the United States, in ways that embody the notion. “The majority of people convicted in our courts for terrorism-related offenses came from abroad,” the nation was seemed to capitalize on their poor notions of geography, as the President provided map of nations from which terrorists originate, strikingly targeting Muslim-majority nations “to protect the American people.”

Yet is the current ban, even if exempting visa holders from these nations, offers no means of considering rights of entry to the United States, classifying all foreigners from these nations as potential “foreign terrorists” free from any actual proof.

Is such an open expenditure of the capital of memories of some fifteen years past of 9/11 still enough to enforce this executive order on the nebulous grounds of national safety? Even if Iraqi officials seem to have breathed a sigh of relief at being removed from Muslim Ban 2.0, the Manichean tendencies that underly both executive orders are feared to foster opposition to the United States in a politically unstable region, and deeply ignores the multi-national nature of terrorist groups that Trump seems to refuse to see as non-state actors, and omits the dangers posed by other countries known to house active terrorist cells. In ways that aim to take our eyes off of the refugee crisis that is so prominently afflicting the world, Trump’s ban indeed turns attention from the stateless to the citizens of predominantly Muslim nation, limiting attention to displaced persons or refugees from countries whose social fabric is torn by civil wars, in the name of national self-interest, in an open attempt to remap the place of the United States in the world by protecting it from external chaos.

The map covered the absence of any clear basis for its geographical concentration, asserting that these nations have “lost control” over battles against terrorism and force the United States to provide a “responsible . . . screening” of since people admitted from such countries “may belong to terrorist groups. ” Attorney General Jeff Sessions struggled to rationalize its indiscriminate range, as the nations “lost control” over terrorist groups or sponsored them. The map made to describe the seven Muslim-majority nations whose citizens will be vetted before entering the United States. As the original Ban immediately conjured a map by targeting seven nations, in ways that made its assertions a pressing reality, the insistence on the six-nation ban as a lawful and responsible extension of executive authority as a decision of national security, but asked the public only to trust the extensive information that the President has had access to before the decree, but listed to real reasons for its map. The maps were employed, in a circular sort of logic, to offer evidence for the imperative to recognize the dangers that their citizens might pose to our national security as a way to keep our own borders safe. The justification of the second iteration of the Ban that “each of these countries is a state sponsor of terrorism, has been significantly compromised by terrorist organizations, or contains active conflict zones” stays conveniently silent about the broad range of ongoing global conflicts in the same regions–

Armed Conflict Survey, 2015

Armed Conflict Survey, 2015

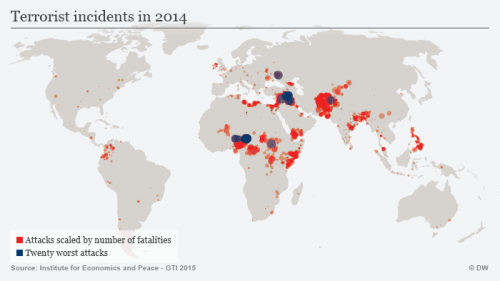

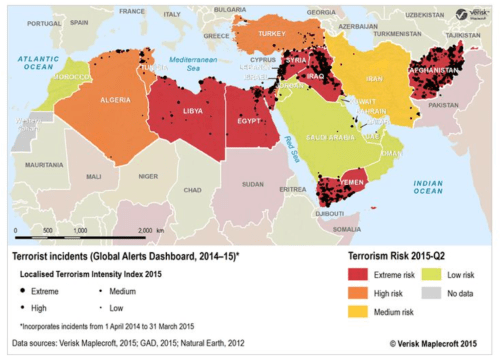

–or the real index of terrorist threats, according to the Global Terrorism Index (GTI), compiled by the Institute for Economics and Peace—

Institute for Economics and Peace

Institute for Economics and Peace

–but give a comforting notion that we can in fact “map” terrorism in a responsible way, and that the previous administration failed to do so in a responsible way. With instability only bound to increase in 2017, especially in the Middle East and north Africa, the focus on seven or six countries whose populace is predominantly Muslim seems a distraction from the range of recent terrorist attacks across a broad range of nations, many of which are theaters of war that have been bombed by the United States.

The notion of “keeping our borders safe from terrorism” was the subtext of the map, which was itself a means to make the nation safe as “threats to our security evolve and change,” and the need to “keep terrorists from entering our country.” For its argument foregrounds sovereignty and obscures human rights, leading us to ban refugees from the very same lands–Yemen–that we also bomb.

For the map in the header to this post focus attention on the dangers posed by populations of seven predominantly Muslim nations declared to pose to our nation’s safety that echo Trump’s own harping on “radical Islamic terrorist activities” in the course of the Presidential campaign. By linking states with “terrorist groups” such as ISIS (Syria; Libya), al-Qaeda (Iran; Somalia), Hezbollah (Sudan; Syria), and AQAP (Yemen), that have “porous borders”–a term applied to both Libya, Sudan and Yemen, but also applies to Syria and Iran, whose governments are cast as “state sponsors” of terrorism–the executive orders reminds readers of our own borders, and their dangers of infiltration, as if terrorism is an entity outside of our nation. That the states mentioned in the “ban” are among the poorest and most isolated in the region is hardly something for which to punish their citizens, or to use to create greater regional stability. (The citation in Trump’s new executive order of the example of a “native of Somalia who had been brought to the United States as a child refugee and later became a naturalized United States citizen sentenced to thirty years [for] . . . attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction as part of a plot to detonate a bomb at a crowded Christmas-tree-lighting ceremony” emphasizes the religious nature of this threats that warrant such a 90-day suspension of these nationals whose entrance could be judged “detrimental to the interests of the United States.”)

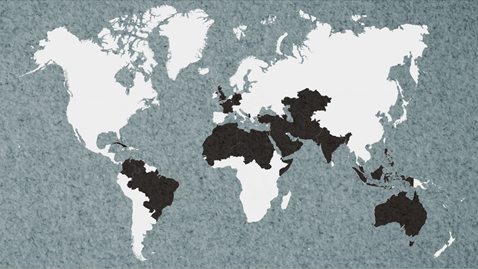

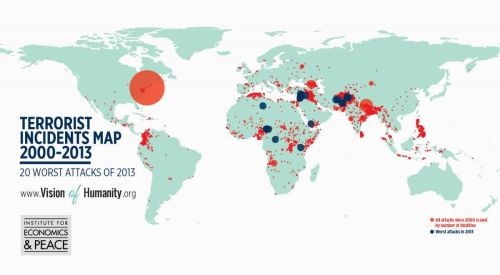

4. It’s not coincidental that soon after we quite suddenly learned about President Trump’s decision to ban citizens or refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries before the executive order on immigration and refugees would released, or could be read, maps appeared on the nightly news–notably, on both FOX and CNN–that described the ban as a fait accompli, as if to deny the possibility of resistance to a travel prohibition that had been devised by members of the executive without consultation of law makers, Trump’s own Department of State, or the judiciary. The map affirmed a spatial divide removed from judicial review. Indeed, framing the Muslim Ban in a map not that tacitly reminds us of the borders of our own nation, their protection, and the deep-lying threat of border control. Although, of course, the collective mapping of nations whose citizens are classified en masse as threats to our national safety offers an illusion of national security, removed from the actual paths terrorists have taken in attacks plotted in the years since 9/11–

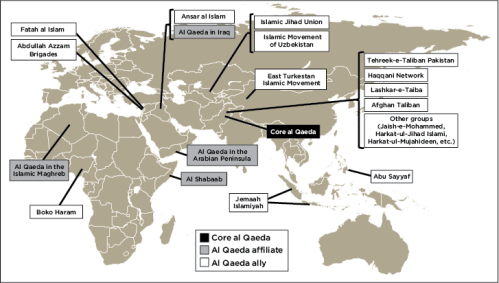

–or the removal of the prime theater of terrorist attacks from the United States since 9/11. The specter of terror haunting the nation ignores the actual distribution of Al Qaeda affiliates cells or of ISIS, let alone the broad dissemination of terrorist causes on social media.

For in creating a false sense of containment, the Ban performs of a reassuring cartography of danger for Trump’s constituents, resting on an image of collective safety–rather than actual dangers. The Ban rests on a conception of executive privilege nurtured in Trump’s cabinet that derived from an expanded sense of the scope of executive powers, but it may however provide an unprecedented remapping the international relations of the United States in the post-9/11 era; it immediately located dangers to the Republic outside its borders in what it maps as the Islamic world, that may draw more of its validity as much from the geopolitical vision of the American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington as it reflects current reality, and it offers an unclear map of where terror threats exist. In the manner that many early modern printed maps placed monsters at what were seen as the borders of the inhabited world, the Islamic Ban maps “enemies of the state” on the borders of Western Civilization–and on what it sees as the most unstable borders of the larger “Muslim world”–

–as much as those nations with ISIL affiliates, who have spread far beyond any country.

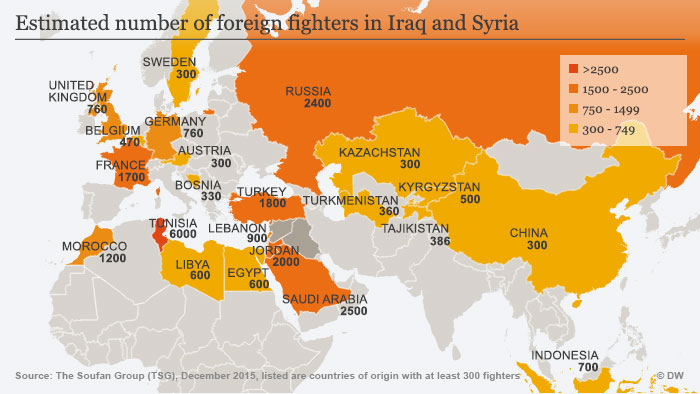

But by playing the issue as one of nations that are responsible for maintaining their own borders, Trump has cast the issue of terrorism as one of border security, in ways perhaps close to his liking, and which plays to his constituency’s ideas of defending America, but far removed from any sense of the international networks of terror, or of the communications among them. Indeed, the six- or seven-nation map that has been proposed in the Muslim Ban and its lightly reworked second version, Ban 2.0, suggest that terrorism is an easily identifiable export, that respect state lines, while the range of fighters present in Syria and Iraq suggest the unprecedented global breadth that these conflicts have won, extending to Indonesia and Malaysia, through the wide-ranging propaganda machine of the Islamic State, which makes it irresponsibly outdated to think about sovereign divisions and lines as a way for “defending the nation.”

Trump rolled out the proposal with a flourish in his visit to the Pentagon, no doubt relishing the photo op at a podium in the center of military power on which he had set his eyes. No doubt this was intentended. For Trump regards the Ban as a “border security” issue, based on an idea of criminalizing border crossing that he sees as an act of defending national safety, as a promise made to the American people during his Presidential campaign. As much as undertake to protect the nation from an actual threat, it created an image of danger that confirmed the deepest hunches of Trump, Bannon, and Miller. For in ways that set the stage for deporting illegal immigrants by thousands of newly-hired border agents, the massive remapping of who was legally allowed to enter the United States–together with the suspension of the rights of those applying for visas as tourists or workers, or for refugee status–eliminated the concept of according any rights for immigrants or refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries on the basis of the danger that they allegedly collectively constituted to the United States. The rubric of “enhancing public safety within the interior United States” is based on a new way of mapping the power of government to collectively stigmatize and deny rights to a large section of the world, and separate the United States from previous human rights accords.

It has escaped the notice of few that the extra-governmental channels of communication Trump preferred as a candidate and is privileging in his attacks on the media indicates his preference for operating outside established channels–in ways which dangerously to appeal to the nation to explain the imminent vulnerabilities to the nation from afar. Trump has regularly claimed to undertake “the most substantial border security measures in a generation to keep our nation and our tax dollars safe” in a speech made “directly to the American people,” as if outside a governmental apparatus or legislative review. And while claiming to have begun “the most substantial border security measures in a generation to keep our nation and our tax dollars safe” in speeches made “directly to the american people with the media present, . . . because many of our reporters . . . will not tell you the truth,” he seems to relish the declaration of an expansion of policies to police entrance to the country, treating the nation as if an expensive nightclub or exclusive resort, where he can determine access by policies outside a governmental apparatus or legislative review. Even after the unanimous questioning by an appellate court of the constitutionality of the executive order issued to bar both refugees and citizens of seven Muslim-majority nations, Trump insists he is still “keeping every option open“ and on the verge this coming week of “just filing a brand new order“ designed to leave more families in legal limbo and refugees safely outside of the United States. The result has been to send waves of fear among refugees already in the Untied States about their future security, and among refugees in camps across the Middle East. The new order–which exempts visa holders from the nations, as well as green card holders, and does not target Syrian refugees when processing visas–nonetheless is directed to the identical seven countries, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan and Libya, while retaining a policy of or capping the number of refugees granted citizenship or immigrant status, taking advantage of a linguistic slippage between the recognition of their refugee status and the designation as refugees of those fleeing their home countries.

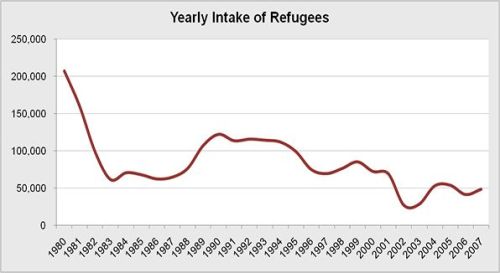

While the revised Executive Order seems to restore the proposed ceiling of 50,000 refugees chosen in 1980 for those fleeing political chaos with “well-founded fears of persecution,” the new policy, unlike the Refugee Act of 1980, makes no attempt to provide a flexible mechanism to take account of growing global refugee problems even as it greatly exaggerates the dangers refugees admitted to America pose, and inspires fear in an increasingly vulnerable population of displaced peoples.

For Trump’s original Executive Order on Immigration rather openly blocks entry to the country in ways that reorient the relation of the United States to the world. It disturbingly remaps our national policy of international humanitarianism, placing a premium on our relation to terrorist organizations: at a stroke, and without consultation with our allies, it closes our borders to foreign entry to all visa holders or refugees in something more tantamount to a quarantine of the sort that Donald Trump advocated in response to the eruption of infections from Ebola than to a credible security measure. The fear of attack is underscored in the order.

5. The mapping of danger to the country is rooted in a promise to “keep you safe” that of course provokes fears and anxieties of dangers, as much as it responds to an actual cause. And despite the stay on restraints of immigrations for those arriving from the seven countries whose residents are being denied visas by executive fiat, the drawing of borders under the guise of “extreme vetting,” and placing the dangers of future terrorist attacks on the “Homeland” in seven countries far removed from our shores, as if to give the nation a feeling of protection, even if our nation was never actually challenged by these nations or members of any nation state.

The result has already inspired fear and panic among many stranded overseas, and increase fear at home of alleged future attacks, that can only bolster executive authority in unneeded ways.

The genealogy of executive prerogatives to defend the borders and bounds of the nation demands to be examined. Even while insisting on the need for speed, security, and unnamed dangers, the Trump administration continues to accuse the courts of having made an undue “political decision” in ways that ignore constitutional due process by asserting executive prerogative to redraw the map of respecting human rights and mapping the long unmapped terrorist threats to the nation to make them appear concrete. For while the dangers of terrorist attack were never mapped with any clear precision for the the past fifteen years since the attacks of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, coordinated by members of the Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda, Trump has misleadingly promised a clear remapping of the dangers that the nation faces, which he insists hat the nation and his supporters were long entitled to have, as if meeting the demand to remap the place of terrorism in an increasingly dangerous world.

The specter of civil rights violations of a ban on Muslims entering the United States had been similarly quite abruptly re-mapped the actual relation of the United States to the world, in ways that evoke the PATRIOT act, by preventing the entry of all non-US residents from these nations. Much as the PATRIOT act led to the detention of Arab and Muslim suspects, even without evidence, the executive order that Trump issued banned all residents of these seven Muslim-majority nations. The above map, which was quickly shown on both FOX and CNN alike to describe the regions identified as sites of potential Jihadi danger immediately oriented Americans to the danger of immigrants as if placing the country on a state of yellow alert. There is some irony hile terrorist networks have rarely been mapped with precision–and are difficult to target even by drone strikes, the executive order goes far beyond the powers granted to immigration authorities to allow the “territoritorial integrity of the United States,” even as the territory of the United States is of course not actually under attack.

What sort of world do Trump and his close circle of advisors live–or imagine that they live? “It is about keeping bad people (with bad intentions) out of the country,” Trump tried to clarify on February 1, as the weekend ended. We’re all too often reminded that it was all about “preventing foreign terrorists from entering the United States,” as Trump insists, oblivious to the bluntness of a blanket targeting of everyone with a visa or citizenship from seven nations of Muslim majority–a blunt criteria indeed–often not associated with specific terrorist threats, and far fewer than Muslim-majority nations worldwide. Of course, the pressing issue of the need to enact the ban seem to do a psychological jiu jitsu of placing terrorist threats abroad–rooting them in Islamic communities in foreign lands–despite a lack of attention to the radicalization of many citizens in the United States, making their vetting upon entry or reentry into the country difficult–confirmed by the recent conclusion that, in fact, “country of citizenship [alone] is unlikely to be a reliable indicator of potential terrorist activity.” So what use is the map?

As much as focussing on the “bad apples” among all nations with a predominance of Muslim members–

–it may reflect the tendency of the Trump administration to rely on crude maps to try to understand and represent complex problems of global crises and events, for a President whose staff seems to be facing quite a steep on-the-job learning curve, adjusting their expectations and vitriol to policy making with some difficulty. The recent revelation of Trump’s own preference for declarative maps within his daily intelligence briefings–a “single page, with lots of graphics and maps” according to one official familiar with his daily intelligence briefings–not only indicate the possibility that executive order may have indeed developed after consulting maps, but underscore the need to examine the silences that surround its blunt mapping of terrorism. PDB’s provide distillations of diplomatic, intelligence, and military information, and could include interactive maps or video when President Obama received PDB’s on his iPad, even encouraging differing or dissenting opinions. They demand disciplined attention as a medium, lest one is distracted by uncorroborated information or raw intelligence—or untrained in discriminating voices from different areas of expertise.