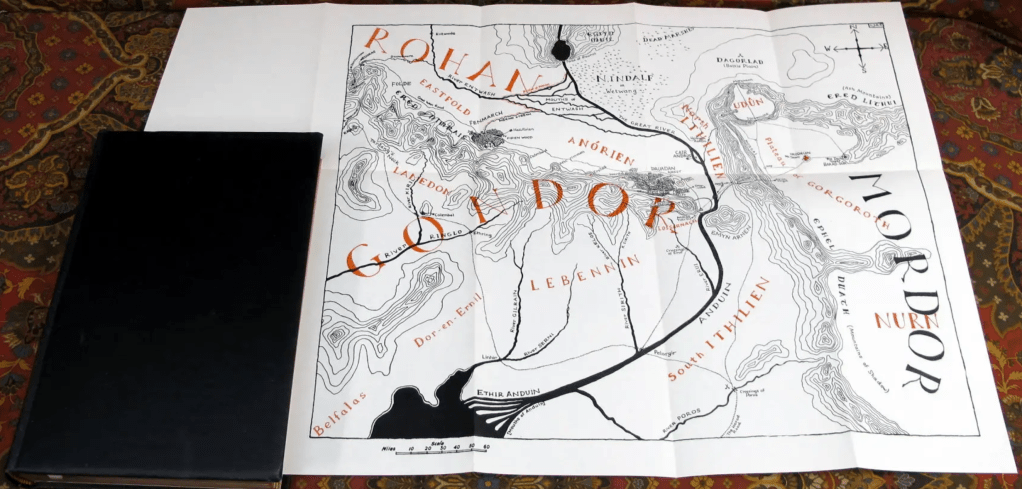

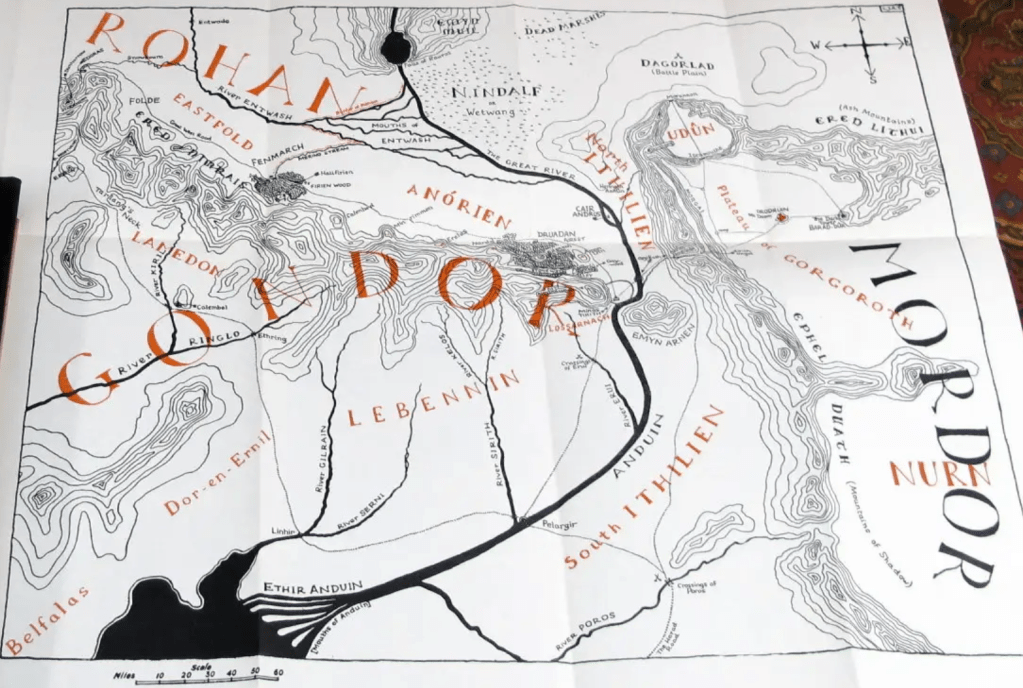

The young Ursula Le Guin had quickly and energetically immersed herself in the three volumes of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings after she sought the trilogy out soon after they appeared, reading them in three days in 1956 so intensively that “she hardly spoke during the three days.” She emerged only to praise the greatness of their scope and vision to her father, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, educated in Columbia and born to German exiles, a linguist of Indigenous languages. If the script of Elvish and runes on its cover would have made it likely to appeal to her father, the noted anthropologist of Indigenous Peoples in California, not for its multiple languages alone–Kroeber nourished a keen dedication to preserving Native American languages he feared may not survive, examining and preserving the speech of Yurok and other tribes in North America as well as Zuni and Peruvian archeology, in ways that probably attuned Ursula to the runic scripts in Tolkien’s work. If her family recited creation stories learned form Native American tribes, perpetuating oral traditions to participate if vicariously in them, Le Guin avidly read books benefitting from the fold-out cartographic apparatus Tolkien had himself drawn with his son Christopher. If the counters were not Baynes’ they were almost obsessively plotted the landscape of the story by mapping Gondor, Mordor and, of course, Hobbiton–located on the same latitude as Oxford! These were the maps Tolkien later had Baynes elaborate, but the detailed mountain ranges, rivers, and inland seas in the “general small-scale map of the whole field of action” would have impressed Le Guin as she read its first printing–did she obtain the copy from Kroeber?–with such fascination and absorption.

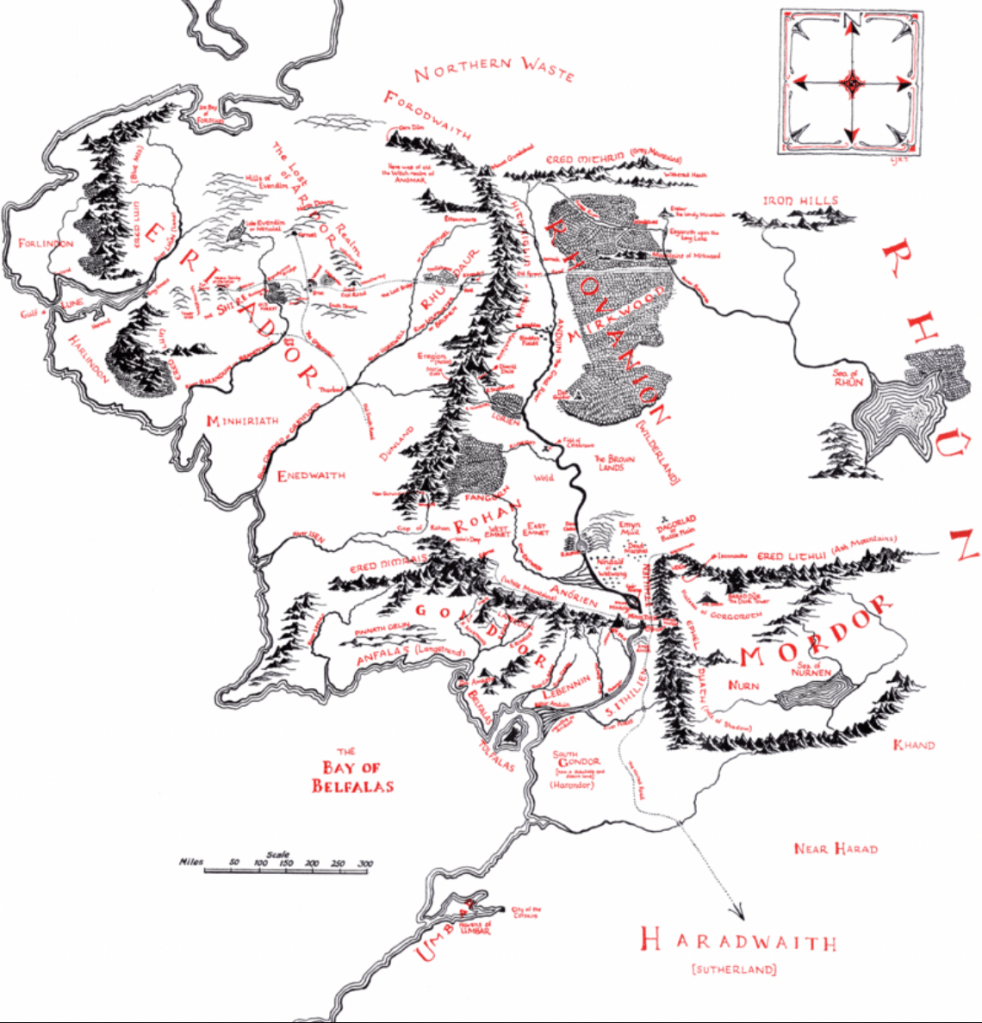

Christopher Tolkien, General Map of Middle Earth (1953)

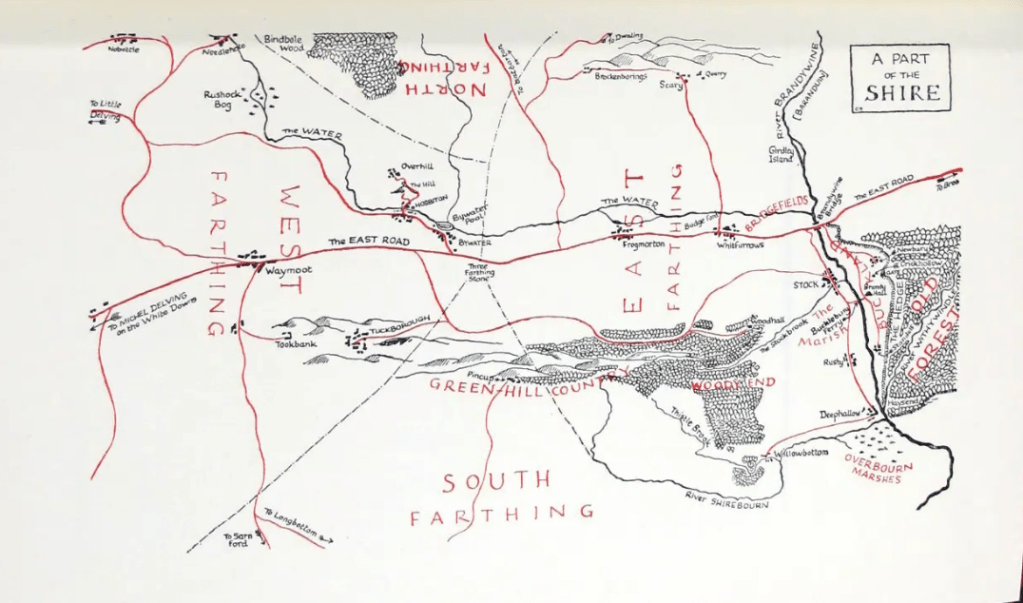

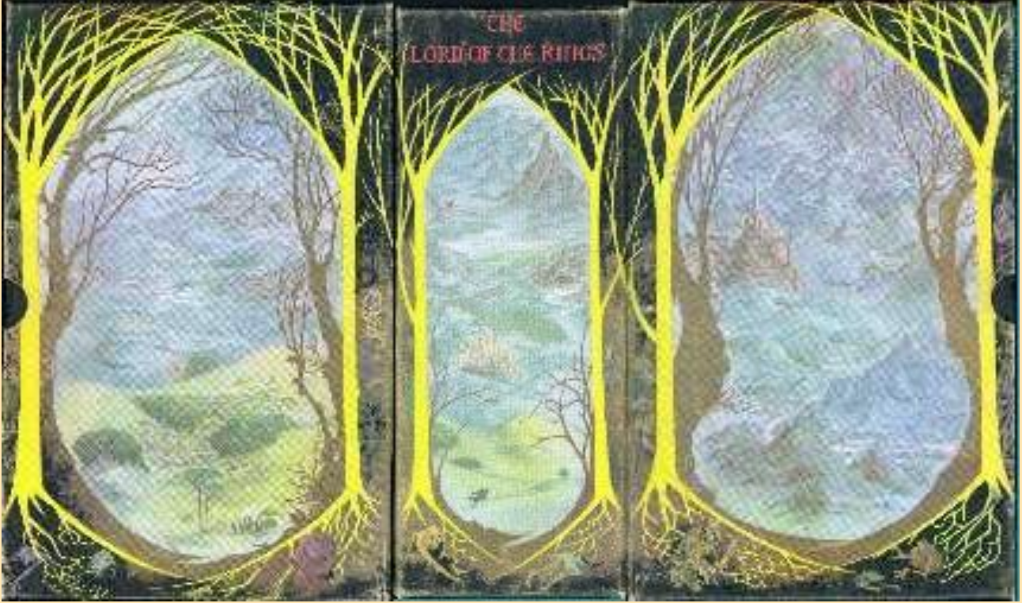

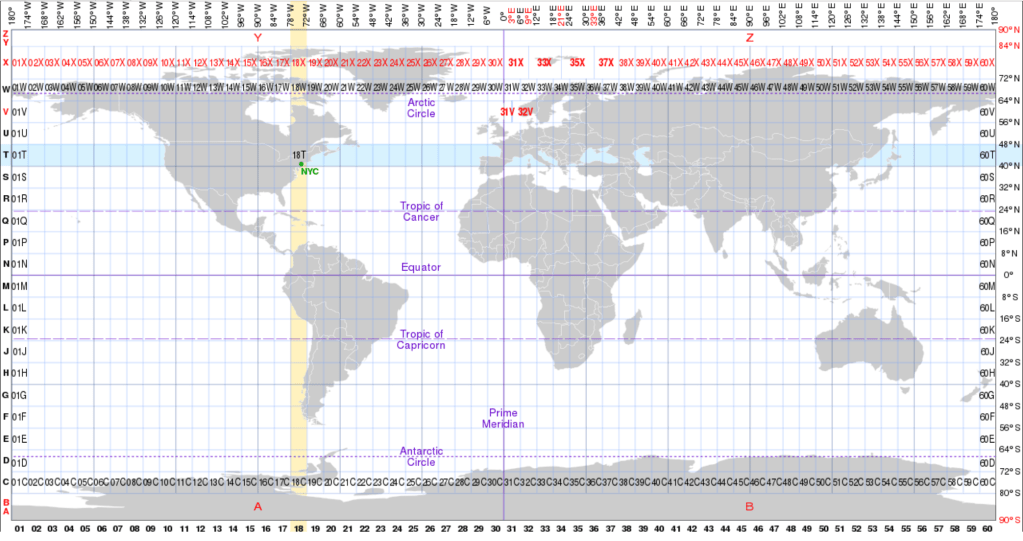

While Baynes may have never read the entire corpus of the Lord of the Rings–and relied on the map that Tolkien provided, as well as the summary that her sister, who also trained at Slade, executed of the main characters and locations, the maps Baynes executed for the 1963 three-volume edition of Lord of the Rings, printing in the early 1960s, that gave Tolkien’s world such truly transatlantic appeal. Ursula K. LeGuin was enraptured by the maps in the three volume edition of 1954-55, that LeGuin had devoured in three days, whose enticing slipcover of the entry into a world led to a series of maps that suggested rendering the expansive setting, and indeed doing so at different scales–integrating the maps that the Tolkien had provided of Middle Earth–even asking Borden Military Camp’s cartography department for assistance in uniting them to a uniform scale of rendering. But the map that was in the 1954 edition suggested the small-scale rendering of the community Bilbo lived that would later expanded in the narrative to the larger canvas of Middle Earth, which Baynes was eventually charged to execute in the more artistic and compelling images we know today. While the books are often taken for younger readers, their expansive scale and detailed topography offered a dense sense of place, starting from a Shire that seemed akin to a mythical rural village in Oxfordshire, a village community, undisturbed by modernity, where the quest of the hobbits began across a landscape dotted by familiar toponyms of an English past, and offering a refuge from the uniformly mapped sense of space of the postwar Universal Transverse Mercator projection that had been developed in wartime, but sought to transcend the national map across borders and frontiers.

Tolkien placed a map immediately after the Prologue to orient readers to the history of Hobbits and the shire of as a local map of place contrasting with the massive quest narrated in the trilogy to seek the “ring” and War of the Ring. If the book was an alternative military landscape of a mythical land, the history and migration to the shire, its bucolic nature suggested a tenuous moment of calm before the story that would unfold, across resonant place names as the “lost realm” of Eriador, near the Blue Mountains, and travel along the roads that crossed forests. the map cast reading as a need to acquaint oneself with the cardinal and ordinal directions that most Hobbits would be utterly unfamiliar, as they undertook their quest across hills and forested lands.

J.R.R. Tolkien, “A Part of the Shire” (1954)

The map offered evidence of the scale and fully-realized nature of the worlds Tolkien had so eloquently and immersively described,–far more successfully, she eagerly if not almost rapturously wrote her father, praising it to Kroeber as more engaging than the fictional worlds of Lord Dunsany, –which disavowed the drawing of clear borders –whose writings she had long loved provided the only fictional comparison of a work of such scale. Dunsay began life as a committed Unionist if he ended his life advocating Home Rule, wrote evocatively of lands without borders. (Lord Dunsany is far less well-known than those of Tolkien and Lewis, Le Guin had been hooked on literature from the evocative first lines of”lands whose sentinels upon their borders do not behold the sea,” bounded to the south by magic and to the west by a mountain–the work, she wrote, had “opened up to me the whole range and realm of fantasy literature — imagined countries, invented histories. I beheld that vast landscape not only as a reader, but as a writer. I could not only go there with Dunsany, I could go exploring on my own.” While never mapping his worlds, Lord Dunsany wrote before and during World War I; the lack of borders were the point. Le Guin would herself pen the hand-drawn faux manuscript form mapping in the craggy mountain range in the detailed maps she later designed with cartographers of Earthsea, the hemispheres of Gethen, and Goat, replete with inlets and coastlines, riverine paths, and oceanic expanse, possibly emulating Baynes’ fine line–plotting the deeply imagined worlds as much as providing a needed cartographic as much as artistic scaffolding for readers.

The hand-drawn maps inseparable from the writing of other planets and other worlds, using maps to register the spatial awareness of its characters as much as to orient us to their travel. Tolkien’s own maps and Lewis’ as well lack borders, or borderlands, unlike the front lines of World War I, but revealed a Neo-medieval world where the lay of the land reflected the character of their topography. (Tolkien had famously begun to conceive of Middle Earth on the front lines of the Great War, if he strongly rebuffed any influence of World War II on the fantasy series. Yet there is the danger of a bit of psychological reductionism that takes our eyes off the staying power of those maps: biographers have noted that the image of Middle Earth may have arrived in the “trench fever” developed as he fought in the trenches of northwestern France, near the front lines of the Somme, which Tolkien quite acutely suffered in the aftermath of the Battle of the Somme–a bitter engagment. The author was the first to acknowledge that the horrible landscapes of Mordor as “The Dead Marshes” and the approaches to the Morannon “owe[d] something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme.” But that the series was a way of “responding to the crisis of Western Civilization, 1914-1945,” in the words of Tom Shippey, demands some unpacking and clearer exploration. For the afterlife of the powerful books was not only haunted by personal trauma.

It is hard to deny the contribution of cartographic relation to the landscape that lacked orientation led Lewis and Tolkien to address different audiences in the postwar era–and the power of the transfigurement of the battle-lines of the western front of 1915 to the palpable landscape. The power of these landscapes as expansive areas of redemption, as much as they’re being haunted by terrifying “wanton destruction” of shattered forests in wartime or maps of devastating military engagement of fallen regiments and monstrous orcs. The sense of a landscape of redemption was keenly felt in later fantasy literature, but perhaps codified by Lewis’ and Tolkien’s works. Indeed, the delineation of these expansive maps of fantasy worlds informed the even greater expansive universe of Ursula K. LeGuin’s many immersive fictional worlds, from Earthsea.

Whether LeGuin was haunted by the inadequacy of her father’s rather notorious 1955 map of borders of Indigenous languages that rendered Native American language groups by clear and distinct boundaries in California and the west, his map dates from the very years that Ursula read Lord of the Rings three volumes, whose dust jacket included the exquisitely colored and detailed map of the travels of Bilbo and Frodo Baggins in their quest for the three rings, the landscape as if viewed enticingly from beneath the arched branches of Middle Earth–an expansive image of the expanded content of the trilogy that folded out from the boxed set undoubtedly impressed her, and its detailed topographic rendering of the mountains of Gondor and the paths by which the quest to Mordor continued suggested the expansively detailed landscapes which she would later write.

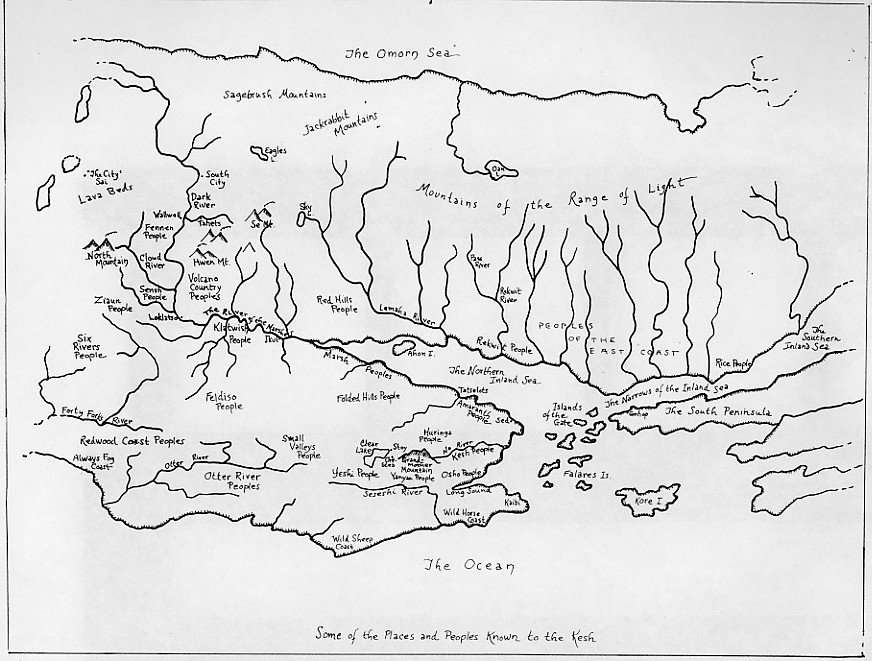

LeGuin’s own maps of a land without borders offered a strong contrast, as if indebted to Baynes’ skill, communicate on-the-ground knowledge of inhabitants who lived and occupied an inland sea, fed by multiple rivers leading to an inland sea, bound by mountains, that provided a testimony of a future world in her final books. If seen as more than an echo of Northern California’s Bay Area–a peaceful land, of a world that showed Northern California after cataclysmic experiences of wartime and sea-level rise due to climate change. (Kesh, pictured below, was known from the field reports of an anthropologist or ethnographer who seems a rather thinly disguised version of LeGuin’s late father, who had for so long dedicated himself to the preservation of Indigenous languages. )

While written among her later works, after Kroeber’s passing, in the 1980s, it registered the first appreciation and fear of climate change and sea-level rise. The novels were written in old age about a futuristic world of post-apocalyptic tenor, that was still littered with the ruins of the institutions of modern society had collapsed but left it littered with the consequences of anthropogenic disaster: an imagined account of the world of earth, the book seemed her version of a protest launched against the excesses of contemporary society, littered with styrofoam and a vast if now-unused computer networks, afflicted by the flooding from sea level rise.) The importance of the shore at the edge of the risen ocean suggests a detail that the consequences of sea-level rise for Northern California are defined, if its recognized landscape was transfigured to create new networks of islands and archipelagos, whose East Coast borders an inland sea, fed by numerous rivers that descend from the Mountains of Light. Is not there a transatlantic echo of Bayne’s work in the futuristic shoreline where the Kesh dwell?

Ursula LeGuin, Places and Peoples Known to the Kesh

The origins of the hand-drawn map does not begin with Pauline Baynes, but maps that Baynes had added to conjure these fully realized fantasy worlds was created in an era of instability felt not only by both authors, but by their common illustrator as well. When C.S. Lewis hired Baynes as illustrator for his set of children’s books, he had little sense of what images but accompanied a book for children. But it may well have attracted him that she had recently worked in Bath for the British Admiralty taking a wartime break from her chosen career of book illustration, during wartime. Her work on ocean charts before illustrating Tolkien’s 1937 verses, Farmer Giles of Ham (1948), lead to an extensive post-war collaborations with both authors’ works of fantasy that seem to naturalize a world that had increasingly disappeared in the continuous surfaces of most postwar maps of space, increasingly separated from the topographic rendering of space.

4. But if we are too eager, perhaps, to tie Oxford’s architectural transport as keys to the worlds of Tolkien and Lewis fashioned, we may do so to search for mythic keys to works that neglect the wartime settings in which they wrote, a time when the making of new worlds gained a new sort of urgency, an urgency that was reflected in the need for new maps of a greener world than the present allowed–or that most of our maps of time-zones, flight-paths, or follow, removed as they are from landmarks or terror–maps that allowed us to pioneer many of the anthropogenic innovations from underseas drilling, deepwater extraction, or map-enabled global transportation networks of oil tankers, container ships, and indeed banking sites in the shadowy “offshore” worlds, lying beyond and outside of Exclusive Economic Zones.

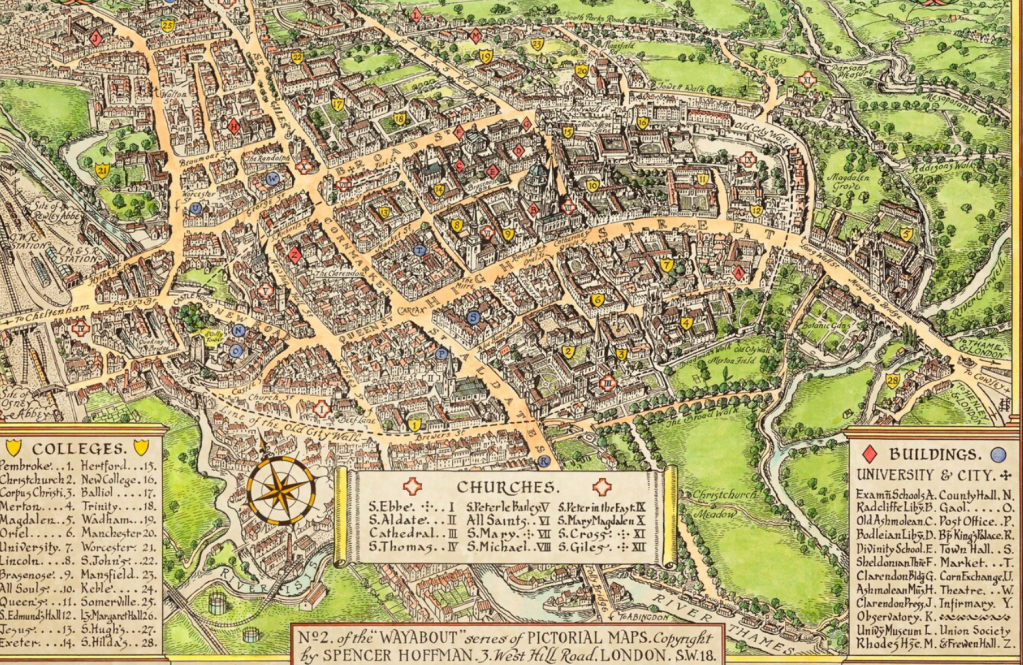

But as much as Oxford’s built structures, enchanting as the spires of its medieval and Neo-medieval monuments are, the greens capes around the Cherwell and Thames that Lewis knew well provided the invitation to explore the Morris-ian “green world” not far from Kenilworth, as the pathway by the canals (unfortunately overeagerly colored in green in this second edition of the popular panorama of the Thames River that traces its course from Cirencester wound down along the region of Oxfordshire, toward London, swerving through the once-verdant English countryside–

Tombleson’s Panoramic Map of the Thames and Medway (1840), Third Edition/Rumsey Institute

–provided a setting where Lewis and Tolkien enjoyed their walks, past Port Meadow and on to Wolvercote to enjoy a pint. Morris had evoked as much–“Forget six counties overhung with smoke,/ Forget the snorting steam and piston stroke/Forget the spreading of the hideous town;/Think rather of . . . The clear Thames bordered by its gardens green/ . . . A nameless city in a distant sea . . . ” as a land of Faërie, whose Gods are akin to those of the ancient nations that bordered the Aegean, setting sail for an Earthly Paradise, with visions of Asgard in their pilot’s sight, conjuring how “o’er the mountains other lands there lay” to seek on a “tumbling sea,” “not losing sight of the shore,” and seeking, after being “entrapped into a fearful sea,/And carried by a current furiously/Aways from shore, . . . /That for a while we deemed ourselves but lost/Amid those tumbling waves,” leaving “the sight of land” to arrive on shores to seek the forest folk. Even if they did not travel over the northern seas much themselves, Tolkien and Lewis, more familiar with the Thames, traveled on the “ocean wide,/Far out of site of land” only anchoring on the long horns of sandy bays in Morris’ Norwegian fantasia to start on our imaginary journeys. Have we forgotten, perhaps, that Port Meadow, even as Tolkien and Lewis walked there, had been transformed in the wartime era to a landing field filled with anti-aircraft obstacles, to prevent the fears of an enemy landing? Danger was close at hand, even as the topography of escape had suddenly shrunk.

The open greenspace of Oxford’s rural past may have offered a setting to meditate on the themes of duty, sacrifice, and destiny that became, as if a modern retelling of Aeneas, intertwine with the updated Faerie Queene, a new topography which Lewis and Tolkien sought to design in the postwar period. For the new maps that the war brought, a cartographic evacuation of God, to some extent, in the triumphs of uniting air, land and sea in geodetic form of a grid, that recall the steep demand that existed to preserve an image of Oxford as a shire, in the pictorial decorative map of the region of 1936, which were suddenly to be drained of their green splendor in the war,–

Decorative Pictorial Map of Oxford (1936), detail

–pushed back on the new reality of a city attacked in the sites of bombing raids that had jerked the region into a mid-century military cartography. Even Port Meadow, which Tolkien and Lewis passed on their way to weekly visits to the Trout in Wolvercote, far from being designated as a Site of Nature Conservation Interest as it is today, but was converted from a Home Front Aerodrome to an anti-invasion defense crowded with poles to prevent German warplanes from landing.

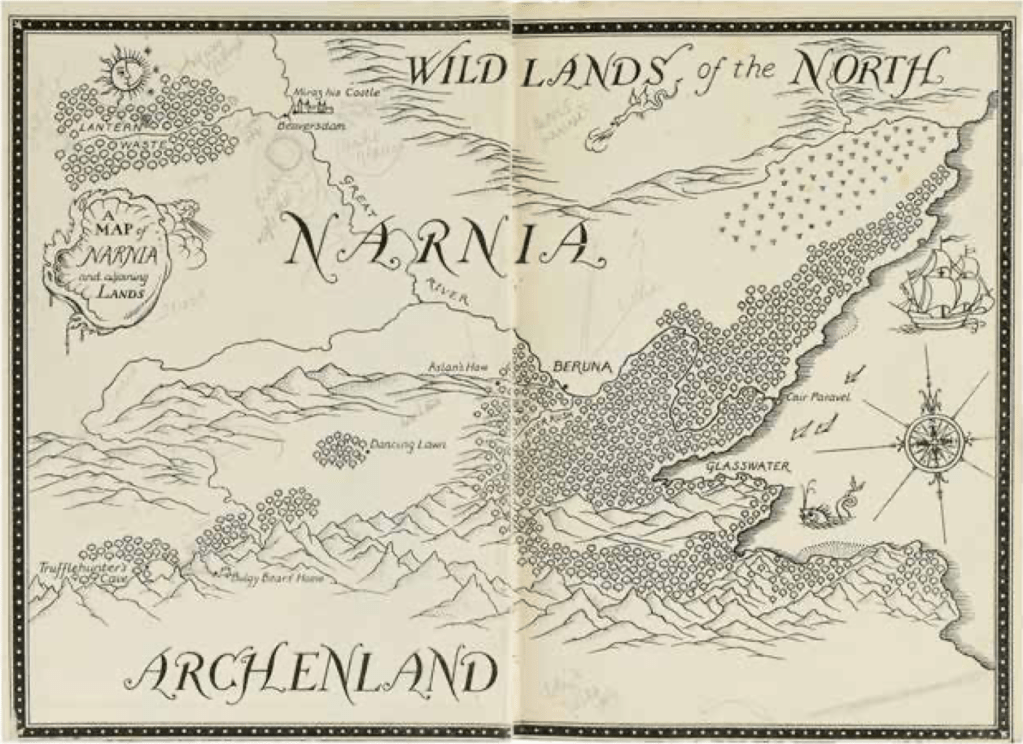

Did the dream of a green world where moral obedience replaced a world where Lewis worried about the erosion of morality in the face of the manipulation of information by a global elite orchestrated by the sinister National Institute for Coordinated Experiments determined to expunge the world from all other living creatures in the name of rationality–and even conquer death. The plot of his fantasy trilogy in outer space was illustrated by Baynes, imagining Venus as covered by a sweet-water ocean which is dotted with floating rafts of vegetation later echoed for children in Narnia, but the new world of Narnia sought a different moral compass in a parallel universe to earth. Pauline Baynes’ work is often seen as a mere question of translation of the author’s maps, but her skill at directing attention to these other worlds is a unique skill for transporting readers of both texts.

What is less well understood, or analyzed, as how much the maps of Middle Earth and Narnia are as well forms of refuge from new mapping regimes, offering us a way of inhabiting enchanted worlds and an enchanted world that is feared to be lost–or to be in the process of rapid disappearance. Do the maps not only concretize these landscapes as past bucolic zones, but pique our curiosity in ways that extend the literature that they were designed to accompany? They surely pique our attention far more than the narrative alone of good and evil which he had previously cast at the center of the three-volume science fiction narrative. That book, “A Modern Fairy Tale for Grown-Ups,” was written in wartime, created a new mythology of a planet controlled in its communication and politics by “The Bent One,” a version of the evil Irish deity, the “Bent-Headed One” (Crom Cruach) or Devil, in hopes to restore cosmic alignment and ties to other planets as the surface of ours has become uninhabitable. He wrote that before he gained confidence to write his own fairy tale for children–if unsure of what would, and eager to show the manuscript of Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe to Tolkien, who had earlier shown friends, probably including Lewis, the images Baynes had drawn for Tolkien’s comic poem may have led him to commission the map “Narnia and Adjoining Lands” to be prepared for the second volume of the series, to attract audiences of children,–

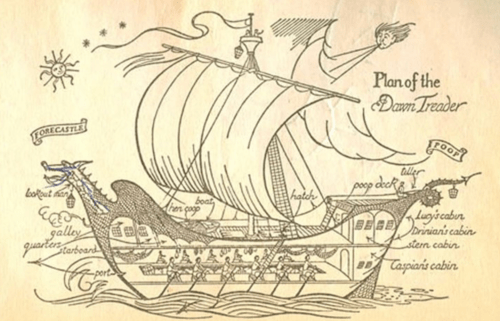

First Map of Narnia, Endpaper to Prince Caspian (1951)

–including a telling ship off of its coasts, that anticipates the third volume already in preparation, famously prominently featuring maritime voyages on a drinkable sea populated by sea serpents off Narnia’s eastern ocean that encourage the children’s curiosity perhaps more than was wise–the entrance of their ship in the previously unmapped ocean between Burnt and Deathwater Island that threatened to destroy the ship that it encircles, but leaves with only the coiled decorative stern that the children successfully fool it to leave after wrapping its immense scaled body around.

The feared ruptures between good and evil which the illustrator of both works of fantasy helped each to navigate, by the cartographic apparatus able to allow them to depart,–or to run against the current of geodetic modernity, removed from place, or perhaps morality. The lack of local color in mapped space in old walking O/S maps of the region were increasingly drained of qualitative detail in the geodetic mapping of routes that had so significantly changed mapped space of the postwar period. The map that served as the famous endpaper for the Dawn Treader in 1950, echoing the maps that Baynes had drawn from 1942 for the Admiralty Hydrographic Department in Bath in its detail, in a canvas that she decorated with medieval iconography as a one-woman Kelmscott Press. (If the images of the Kelmscott books that William Morris had printed sought to reintroduce the hand-drawn landscape of a manuscript that rescued print as a medium for the author, without needing to violate the copyright of the Kelmscott Chaucer that offered a working model for Morris’ press.). The map of the Dawn Treader’s voyage includes the prominent calligraphic lettering of oceanic expanse off of Narnia’s shaded coastlines–“The Bight of Calormen” and “The Great Eastern Ocean”–not yet included in the book’s narrative, but adding a sense of oceanic expanse Baynes was skilled rendering in maps for the Hydrographic Office, and contributed to the sense of the book’s adventures, in the front endpaper that described “The first part of the VOYAGE,” evoking pirate maps of Robert Louis Stevenson of a nautical quest off Narnia’s fabled shores.

The topography of Middle Earth and Narnia are examined as landscapes born from their authors’ heads, as Minerva, as much as they are enhanced by maps. But the woman who mapped Narnia’s shores–and forests–and drafted the actual maps that were preserved in both books, are crucial aspects of their power, yet rarely examined as creative contributions to the written texts that they accompany–and a field of reading that are inseparable enhancements of their literary power. Although Baynes is graciously remembered by readers, her relation to the commitment of both authors to create new maps for readers–and indeed to attract the children readers that both aspired, but had never written for–demands examination beyond the crediting of Lewis or Tolkien as the sole author of their fantasy series, helping us to return to read, and indeed be captivated by the landscapes that she mapped. Although Baynes kept her business dealings rather separate from both–she rarely met either, in part because of Lewis’ quite austere discomfort before her, and corresponded only n perfunctory manner, the correspondence she had with Tolkien on maps of his own design seem to have reinforced the impression of Baynes as an amanuensis and assistant, more than as giving birth to the worlds for readers, and as shifting the experience of reading either series. The images were seen as adornments, rather than integral to, the texts, and the maps that Tolkien made have been regarded as a sort of Holy Grail of Middle of Earth, the underpinnings of her efforts, but have stimulated many readers to take the cartographic rendering of Middle Earth into their own hands. Yet Lewis was particularly relieved “seemed happy to leave everything in my completely inexperienced hands!” and valued Baynes for her drawings of the enchanted lands he sought to offer children, in no small part for the cartographic aids she offered for a world that he had not yet mapped. Baynes’ contribution to the series served as a one-woman Kelmscott Press of mass market paperbacks, as well as for the hardcover editions featuring her maps as endpapers.

In examining the relation of literature and cartography, we might think twice about the relation of Baynes’ maps to her own wartime expertise, and the constraints and limitations that both authors would have felt to the mapping services as the 1936 British Ordnance Survey that suggested the first abstracted reaction to the land, a sort of disenchantment of the landscape that both authors saw their works as tools and agents for working against. The maps demand to be situate3d in a global cartographic revolution of the prewar and postwar period, as much as both works have been usefully situated in relation to the authors’ experiences in World War I. If Tolkien might have argued that World War II bore little relation to the construction of Middle Earth, the pressing invitation to explore quests, and indeed animated scenery, haunted in animistic as well as almost biological ways, encouraged the role of myth in exploring and understanding landscapes, serving as a counter-agent of the increasingly abstracted definition of place in the technologies of mapping global continuity on a fixed grid, separately from the lay of the land on which it was imposed.

Very eager to read this post—looks delicious! Can’t wait to finish it!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!