Geodesy has long increased the number of claims by extractive industries through remote sensing, and especially over indigenous lands. Yet crowd-sourced tools of geolocation have also enabled a range of counter-maps of indigenous native land claims that have pushed back on how industries that have increased access to the resources buried beneath the very lands to which indigenous groups have ancestral claims. Indeed, powerfully innovative webmaps like NativeLands provide not only a new standard for cartographic literary, but to achieve epistemic change. They offer an opportunity for ethical redress of the lost of lands indigenous have roundly suffered from the uninvited Anglo settlers of North America, a counter-mapping that is alive and well on web maps.

They reflect a deep legal search to redraw the bounds of indigenous maps, long rooted less along exclusive claims of property–or property laws of fixed ownership. They rather reflect a history of the long and tortured history of the session of land by native peoples, often signed under duress, without clear understanding of the consequences of treaties that ended precedents for land claims. But they stand, it seems, in contrast to–and perhaps in needed dialogue with–the earliest maps of the presence of indigenous across North America, a presence marginalized from the 1830s, with the legal appropriation of indigenous lands sanctioned by the Indian Removal Act (1830). Thoreau’s sought traces of indigenous inhabitation of New England–through the adoption and compilation of place-names and sites that he found of special significance to the nation–pushed back against that Act, and seems to have sought to reclaim or restore an exemplary sort of awareness of that past, imagining that it might be intuited from Champlain’s 1612 “Carte Geographique de la Nouvelle France,” idealized as capturing a moment of contact where natives were not yet mapped off a new national map. Thoreau imagined a remapping of national land-claims, in an area of settlement before contact, if Champlain in 1608-11 only encountered the tribe he knew as the Armouchiquois as he explored the St. Lawrence River and Maine coast. Yet the map resonated with him as a deep tie to the land, leading Thoreau to retrace its contours to capture that primeval moment of real contact.

Clear designation of the past presence is oddly evident in notations of early modern maps, albeit outside of clear boundaries. Indeed, on the surfaces of many early modern maps, the capital letters of early colonial states commingle with the tribal presence of Shuman, usually mapped near the Rio Grande; Natchitoches, a Caddo-speaking people now located at the borders of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana; the Cododaquio or Great Caddo on the Red River; Chicachas or Chickasaw of the southeastern woodlands, whose forced migration west of the Mississippi lost their ancestral lands in 1832; or Tchatas or Choctaw who once dwelled across what be came Alabama and Mississippi–or the Alabamans or Alibamu tribe, tied closely to the Coushattas, belonging to the Creek confederacy. These names, and others, legible on the map, as evident in the 1764 Atlas petit marine, were preserved in maps prior to American independence and sovereignty, can be seen as stylistic ancestors of the alternative forms of noting ancestral claims on web-based maps.

The growth of consciousness of ancestral land claims has promoted a need to accommodate property claims that had promoted a mapping of jurisdiction along clearly demarcated lines, ending or eroding indigenous land claims, and parallel the search for a new legal framework to acknowledge and recognize past claims of historical habitation that had been eroded by a treaties, land cessions from claims of collective possession, and fit a new legal language of ancestral lands often excluded from property law. After all, back in the famous if not canonic account of the Plymouth Plantation that the Puritan William Bradford wrote, the sites of Europeans were already firmly set back in 1650 on the “vast and unpeopled countries of America, which are fruitful and fit for habitation, being devoid of all civil inhabitants, where there are only savage and brutish men which range up and down, little otherwise than the wild beasts of the same,” perpetuating a quite distasteful image among Puritans–who saw the inhabitants as satanic in ways that are difficult to acknowledge–of lacking ‘civil’ grounds of inhabiting the selfsame lands, as well as being “cruel, barbarous, and indeed treacherous, . . . merciless [in their] delight to torment men in the most bloody manner.” The hateful image Bradford painted meant that hey not only lacked license to inhabit the lands by property rights, but constituted a civil danger for those settlers who colonized them–or arrived to set up commerce and trade on them. Bradford, who wrote the Plymouth Plantation history in the immediate aftermath of the Peace of Westphalia, inscribed the New World as an anti-Westphalian order of no boundaries, akin to a state of nature, but also left open the possibility of inscribing the landscape in a post-Westphalian order, an imaginary of boundedness that was divided by frontiers and mapped indigenous outside boundaries around exclusion, an imaginary of space that has continued to inform the cartographic imaginaries of indigenous from early anthropologists as Alfred Kroeber’s maps of languages to today–not imagining the indigenous societies of the world to exist outside of and in relation to a bounded state or miniature mini-states.

Alfred Kroeber, “Indigenous Languages of California,” University of California, Dept. of Anthropology (1922)

The difficulty of mapping the inhabitation of the continent outside of a Westphalian optic of fixed boundaries, and European concepts of territoriality and land possession, has created problems of a deeply cartographic sort for indigenous maps. If the cessions of land and territory, and the removal of land rights, have been able to be defined in this Westphalian optic, the networks of migration, trade, and sacrality or social spaces of the indigenous socieities–and their relation to entities like rivers, lakes, or mountains, has been difficult to translate into a syntax of polygons and bounded edges, even if these are the edges by which property and parklands are increasingly understood. How can the multidimensional relation to space among indigenous be figured or mapped?

The problem of the plurality of land recognitions that NativeLands documents in its mobile maps across America document the complexity of native land claims in its web maps as a bounteous flowering of a multitude of local claims that seek not only to evoke the ancestral lands, but to show the wealth of inhabitants who, far from wandering, regard their claims to land as historical, and indeed were compelled to historically compelled to cede them. By the mapping of actual cessions and land claims, the wealth of material the mapping engine assembles offers a radically different nature of continental inhabitation–inhabitation that long antedated the Puritans’ arrival.

The rich range of pastel colors in these webmaps suggests the range of claims that we must, moving forward, be compelled to entertain and would do well to celebrate. Modern Canada constitutionally only explicitly recognizes three groups of aboriginal or indigenous–the Inuit, Métis, and generic “First Nations”–the multi-color blocks of native lands and historic “cessions” of tribal lands suggested a new understanding of how Canada had long celebrated its multiculturalism as a “mosaic” and not a “melting pot”–but showed the divisions of the land claims of a plurality of indigenous groups never recognized by Canadian law–and still quite problematically recognized in public acknowledgements of respect for land long inhabited by indigenous or “autchothones” proclaimed with piety by national airlines whose flight paths criss cross endangered boreal forests that tribes have long inhabited.

Air Canada went to pains the national company took at presenting a land acknowledgment in the form of a public announcement to all passengers, as if a remediation of the incursion of their airspace. But the video quickly turns to promote the airline as a platform for personal advancement that actual indigenous elders–if not leaders–embraced, affirming the cultural mosaic called into question if not challenged by the shard-like divisions staked on NativeLands, and its maps of historical land sessions. The flight over land seems to acknowledge indigenous claims to regions of pure waters and lands of a boreal forest, that maps an odd acknowledgement of indigenous presence from the air–paired with testimonials from Air Canada workers of native parentage attesting to longstanding fascination with the planes flying above over native lands and in airspace that was never properly defined–and the company’s commitment to secure these rights, as the major national company of state-run transportation.

–that suggest a respect traditions from the perspective of the modernity of air flight–as First Nations asserted data sovereignty over the lands they inhabit by a system of automated drones from 2016, to build a transportation infrastructure available to communities often isolated from infrastructure roads–and the notable fact that Canadian indigenous constitute the fastest-growing population in Canada, a notable fact of increased political significance, raising questions of the integration of their communities that could be reconciled with the historical transfer of land in the numbered treaties, 1871-1012, to transfer tracts of lands to the crown for promises that were rarely kept.

The odd status of indigenous lands in the nation puts the national airline of Canada at a unique relation to indigenous territories in recent years: while Canada’s divided system of federal sovereignty has begun to affirm aboriginal title in legal terms, and recognize autonomy of regions of indigenous settlement within Canadian sovereignty of the entire nation, the status of First Nation’s title are like islands of federal supervision in provinces, leaving national agencies like Air Canada, which reserves Parliament’s legislative jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians,” in an outdated legal formulation, a unique and privileged ties to lands of aboriginal title: the title of the nation is understood as parallel to and not in conflict with historical title of First Nations, which are incorporated into the nation as islands of federal sovereignty which still exists over the regions of the Numbered Treaties, which have never been legally dissolved.

Numbered Treaties and Land Cessions with Indigenous First Peoples, 1871-1921

Is Air Canada, the national airline service, not acting as a proxy of the federal government in acknowledging the continued land claims of Native Peoples hold to old growth boreal forests below routes the airline often flies? The question of indigenous properties and indigenous autonomy is in a sense bracketed over areas Canada acquired from Great Britain in 1867 and purchased from the Hudson’s Bay Company three years later? The increasingly pressing question of how to acknowledge native sovereignty is hoped to be accommodated to the Canadian image of a “cultural mosaic” of sorts, and the NativeLands offers what might be best seen as a response to that mosaic–not an image of interlocking shining cultures of sparkling individuality, but the overlapping rights of possession not rooted in firm boundary lines, but in forests, rivers, and streams, not as a generic bucolic region out of cities or accessible infrastructure, but a new form of mapping, rooted in notions of neighboring places, and acting as a neighbor to places–and inhabiting spaces–that is distinct from an Anglo-American system of property rights.

“To Learn More about the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, Click the ‘About Us’ Onscreen Tab”

For although the maps of Anglo settlers–attracted by the shifting global markets for goods, from cotton, to gold, to petroleum, all claimed without consent from their longtime inhabitants–erased or omitted local claims to land by those seen as nomadic, and of an earlier historical developmental stage, with a cutting logic of relegating their very presence to the past, the reframing of collective memories to inhabiting lands and regions offers a plastic and particularly valuable cartographic resource for remediating the future. The change parallels the first assertion of reversionary practices to land title, marked by. the Nisga’a Land Title act of 2000, which guaranteed title to lands outside of a historic chain of property deeds, allowing the determination of titles dependent on competing interests, by which the state can ensure ownership that incorporate traditional ways of recording property interests, outside of a property system of deeds: the new legal authority of the state may as well have inspired, this post suggests, a new form of mapping, in a webmap able to register mutually competing interests in compatible ways, rather than privileging historical titles of written form. In this sense, the growth of webmaps offer a new form of an open repository for competing claims, not linked to a legal system that has long favored colonial or settler claims.

The problem of a project of decolonization of course was greater than a map could achieve–but the relentless colonization of indigenous spaces and places needed a public document or touchstone to return. The presence of native tribes was never in question during the colonization of the continent–if one can only ponder the notion of the Library of Congress, Daniel Boorstin, who commemorated the approach of European and native cultures as so culturally fruitful for American culture, rather than one of loss. But how to take stock of the scale of loss? Northern California has been recently a site of active indigenous resistance to a legacy of colonization, the cartographic unearthing of land claims offers a new appreciation of increasing pluralistic possibilities of occupying the land.

Webmaps offer the possibility of stripping away existing boundaries, in cartographically creative ways, by interrogating the occupation of what was always indigenously occupied in new ways. Henry David Thoreau was plaintive as he voyaged down the Concord River, realizing how native lands had been not only usurped by the introduction of European grasses and trees, not only leading the apple tree to bloom beside the Juniper, but brought with them the bee that stung its original settlers; pushing downriver and “yearning toward all wilderness,” he asked readers, “Penacooks and Mowhawks! Ubique gentium sunt?” The signs of longstanding presence are not erased, but present on the map. And although lack of fixed boundaries on native lands have long provided an excuse to stake claims that exclude inhabitants who are seen as nomadic, or not settled in one place, and laying claim or title to it, and “without maps,” the blurred boundaries of NativeLands re-places longtime residents on the map, wrestling with the long-term absence of indigenous on the map.

It is, perhaps, not a surprise that the crowd-sourced interactive website Native Land Digital that was the brainchild of Victor Temprano, in the midst of the heady environment, CEO of Mapster who worked on a pipeline-related project, circa 2016. The sourcing of maps for indigenous land claims was pushed by his own anti-pipeline activity that involved remapping the place of planned lines of transport of crude oil from the boreal forest south to New Orleans on the KXL project and to Northwest ports Victoria threatened native lands and the ecological environments exposed to threats by drilling and clearcutting and risks of leaks. The current live charting at a live API offers total coverage of the globe, as may be increasingly important not only at a time of increasing unrestrained mineral extraction to produce energy but the retreat of ice in global melting that will alter animal migration routes, thawing permafrost, and sudden drainages of inland lakes that might call attention to new practices of land preservation.

The rich API provides a reorientation to the global map promising a powerful new form of orientation. Temprano, an agile mapmaker, political activist and marketer, framed the question of a more permanent digital repository of a global database of indigenous geography, that put the question of indigenous map front and center on the internet globally. The product, that led to an ambitious open source non-profit, sidestepped the different conceptions of space, time, and distance among indigenous communities, or the blurriness of fluid bounds, and opted the benefits outweighed the costs of an imagined the collection of maps of ancestral lands in term by the GIS tools of boundaries, layers, and vector files, as a rich counter-map to settler claims, able to collate lands, language and treaty boundaries on a global scale. The dynamically interactive open-source interactive project, known for its muted pastel colors, rather than the harsh five-color cartography that reify sovereign lines that posits divide as tacit primary categories of knowledge, is subtly compelling in its alternative non-linear format, that invests knowledge in sensitivity to the contributions of each of its viewers: dynamic, and administered by a non-profit with native voices on its board.

It is, inventively, able to maintain the dual display of a site where one could easily navigate between native and Canadian place-names and explore “indigenous territory,” as if it might be mapped by mapping space onto time in the broadly used cartographic conventions that have developed and flourished in online mapping ecosystems–and offered the benefit of creating layers able to be toggled among to layers of treaties by which land was legally ceded, overlapping language groups, and a decolonized space that was particularly sensitive in Canada, where the ability to engage outside colonial boundaries had been placed on the front burner by extractive industries. There is a sense, in the crowd-sourced optimism that recalls the early days of OpenStreetMap and HOT OSM, of the rewriting of maps and the opening of often erased land claims that crashed like so many ruins that accumulate like a catastrophe as wreckage that has piled at the feat of an Angel of History who is violently propelled by the winds to the future, so she is unable to ever make the multiple claims and counter-claims in the wreckage at her feet whole, and the pile of ruins constituted our sense of the progress of the present, even as it grows toward the sky. Was this a new take on the cultural mosaic of Canada, now revised as a problem of staking claims to the visions of property that the land cessions of the Native Treatise of Canada erased.

The website was the direct reaction to the active search for possibilities of extracting underground petrochemical reserves on indigenous lands in Canada. The growth of the website north of the border however has resonated globally, underscoring the deep cultural difficulties of recognizing title to lands that was long occupied by earlier settlers. If many of the claims to petroleum and mineral extraction in indigenous land is cast as economic–and for the greatest good–the petrochemical claims are rooted in an aggressive military invasion, and are remembered on NativeLands.Ca as the result of abrogated treaties and land cessions that must be acknowledged as outright theft.

The history of a legacy of removing land claims and seizing lands where Anglos found value has led many to realize the tortured legacy–and the unsteady grounds on which to stand to address the remapping of native lands. General Wesley Clark, Jr. acknowledged at Standing Rock, asking forgiveness in 2016, almost searching for words–“Many of us are from the units that have hurt you over the many years. We came. We fought you. We took your land. We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents onto your sacred mountain. . . . We didn’t respect you, we polluted your Earth, we’ve hurt you in so many ways, but we’ve come to say that we are sorry.” Crowd-sourced maps of claims on NativeLands offer an attempt at remediation, although a remediation that might echo, as Chief Leonard Crow Dog responded at Standing Rock, “we do not own the land–the land owns us.”

The sacred lands that had long reserved sacred lands in ancestral territory to indigenous tribes were indeed themselves contested at Standing Rock in 2015-6, when the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie that assigned Sioux territory east of the Missouri River and including the water that runs through these ancestral lands as including the water, but the protection of these waters as within ancestral lands was not only challenged but denied by the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline, even if the water runs through Sioux territory, as it long had, leading the Sioux Nation to bring suit against the US Army Corps of Engineers for having planned the pipeline through their ancestral lands, and attracting support of military veterans who objected to the continued use of Army Engineers to route the pipeline through historical and cultural sites of the Upper Sioux that ran against the lands reserved fort he Sioux nation.

The challenge or undermining of ancestral claims to land by the DAPL offered a basis for accounting or tallying of the respect of previous treaties and land claims. In the rise of the webmaps Native Lands, a new and unexpected use was made of the very cartographic tools that facilitate international petrochemical corporations–and indeed military forces–to target lands valued for mineral production with unprecedented precision have helped to stake a claims for the land’s value that undercut local claims to sovereignty. The website offers a way to preserve claims that were never staked earlier so clearly, and to do so in dialogue with broken treaties as a counter-map taking stock of the extent of indigenous lands. It is as if, within the specters of extractive industries’ deep desire to possess the targeted energy reserves, and at the end of a history of dispossession and destruction, the indigenous that were systematically killed and removed from their lands over the nineteenth century, at whose close 90-99% were killed, in a massive and unprecedented theft of land, forcing them from migratory habits to receive religious instruction and live on bound lands to which they were confined. In Canada, where NativeLands grew, displacement of land rights began from clearing herds of bison herds from Prairies to begin construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the principle commercial artery to the West, that had by 1869 shifted indigenous resources to rations that rarely arrived, to be replaced by cattle on lands settled by European farmers and style of agriculture. The melancholy history Plenty Coups framed of the extinction of Crow sovereignty went beyond land rights: “when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift hem up again: after this, nothing happened.”

Time stopped because the imposition of new modes of agrarian regime recast native lands as terra nullius to be settled by Anglo and European farmers, a surrender of land title from 1871-1921 that nullified local land claims. The cartographer and framer of the U.S. Census, newly appointed to what would be the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Francis Amasa Walker conducted the first review of 300,000 Native American in the United States of 1874, trying to sort out the theft of land over four hundred treaties. Walker’s agency was not clear, but if he bemoaned theft of ancestral lands fertile and rich with game, confined in land that could not support them and dependent on rations, there is some sort of redress in how the NativeLands maps invites us to retrace the sessions of lands that undermined these tribal claims, and erased these nations, not deemed fit to have place or stake belonging in American made maps that Walker helped to codify, placing the loss of land that Plenty Coups did so much to try to protect and retain, against all odds, in making trips to Washington DC to allow Crow claims to survive in this new White Man’s world. Even if the claims that he preserved were less than they had been originally allotted–just 80%–he forestalled desires to claim land for gold prospecting and mineral extraction that are effectively on the cutting block once again today.

By 1892, the Territories of the five civilized “Indian” tribes, west of the Mississippi, confined in fixed frontiers after the forced migration in a process of Indian Removal of indigenous east of the Mississippi, later forced to resettle in the early 1820s into the area adjoining modern Oklahoma, where indigenous already lived, renamed “Indian Territory” but within newly fixed bounds. What was a rich area of hunting and without permanent settlement was long understood as their own lands, but were absent from maps until the relocation of “civilized tribes” into the boundaries of Indian Territory, imposing a new notion of territoriality on Indian Lands that delegitimized nomadic presence in earlier native lands–tribes whose presence was “civilized” as they had gained governments and legal traditions modeled on America.

While we see these maps as pinpointing mineral claims with precision that might allow extraction of underground reserves, it would be better to learn to regard the map of claims as akin to an ecological haunting of North America, disrupting not only settled modern treaties with indigenous peoples in Canada, but disrupting the longstanding claims of historical inhabitation of lands by those who long conserved them, a conflict of two geographies that, globally, is steaming to a head in the twentieth century, as global claims risk obscuring the local claims of the custody and preservation of historic claims: an entanglement of overturned treaties, renegotiated sites of mining and mineral extraction, and actively negotiated land claims, the map is not a record of spatial knowledge, but also something of a historically determined palimpsest, if urgency of locating energy reserves for collective good risk flattening the rich historical record in the search for petrodollars–the dominant global currency of the day to which ancestral lands are compelled to accommodate.

This post seeks to address ongoing questions of land use decisions that are of increasing importance in an era of shifting ecological niches and ecosystems by pollution. While the lines of indigenous territory were long discounted and seen as less easily translated into terms of territoriality–the roaming or spatial dispersion of households of indigenous bands over a vast area were seen as not having a fixed perimeter, or a “map-like representation” of territory and a communitarian notion of land-use–whose “use” of a territory was foreign to concepts of a nation, or able to be compared to the bounded territoriality settler communities understood their own worlds., or territorial demarcations and partitioning, and foreign to “true land ownership”–their maps did not indicate lines of property ownership.

Before such a map of the recent land claims that seem to grasp smattered mineral deposits for extractive possibilities, it seems counterintuitive that the modern tools of geolocation have provided a new basis to affirm indigenous claims to the land–as if the two maps are departing from one another, red splotches revalued and excised from established treaties.

The abrogation of treaties is nothing new to the history of indigenous claims from the nineteenth century to ancestral lands, but the heightening of debates in recent years accompanies the expanded scale of destruction of mining and the logic of geolocation of mineral deposits from remote sensing, leading to a growing number of claims removed from treaties that were intended to preserve a site–see the range of claims eagerly made on land in Bears Ears!–in a mad scramble to unlock mineral resources buried under the land.

But if the patchwork of red dots denoting mineral claims seem located with a terrible certainty in historical and modern settled treatises, tools of mapping have opened indigenous perspective on land claims as a form of private property and ancestral lands that descend from the Enlightenment defense of how states secure private property rights John Locke most clearly articulated as the right taking into possession of the lands of indigenous who had failed to cultivate or farm lands, or, in modern terms, extract their resources. While Locke developed ideas of property while working for the Secretary for the Royal Council on Trade and Plantations in the Carolinas, eager to settle areas of “New World” to benefit Atlantic trade, crafting a constitution for the Carolinas, based on the cultivation of those lands that indigenous “failed” to cultivate, the export of the current underground resources lying in land claims currently being renegotiated is based on a terrifyingly similar logic.

It is in the context of the proliferation of mineral claims that the creation of new online maps of ancestral lands have been developed, as a counter-mapping of land claims that have long been insufficiently preserved in treaties or recognized. They seek to pose questions of the long unresolved questions of possessions, raising deep ethical questions of the limits of ownership, and artfully articulate the need to formulate forms of acknowledgment of the expropriation of indigenous rights. The collective nature of the crowd-sourced response to the erosion fixed lines of property long posed to indigenous lands, forested or unploughed, offers a provocative cartographic riposte to the toxic multiplication of claims of mineral resources that upset modern treaties, swept aside with historical treaties that seem to fall as if at the feet of the Angel of History, blown backwards by time, as if so many ruins of the past.

As we try to calculate the depth of historical obligations of nations to native peoples and indigenous land claims, the crisis of extraction may provide more than healthy starting point. While the probability of gas reserves may be more difficult to pinpoint above the Arctic Circle, as exploratory studies are less rarely authorized, and since their discovery in 2008 were newly classified as “potentially recoverable”–although as arctic ice sheets melt, that story is potentially beginning to change: but if the chromatic variation in geolocated gas reserves north of the Arctic Circle seem suitably drained of color, the apparent absence of any land claims on the map seems almost strategic. Is the absence of any indication of ancestral lands in the circumpolar stereographic projection not privileging advantageous opportunities for oil extraction, rather than recognizing longstanding land rights, or sites of residence?

Yet the naming of the land, or its recoloration by the likelihood of extracting mineral profit, irrespective of the environment, is a dramatic remapping of value in the land, in ways not seen by its inhabitants, and a triangulation of human relations to the land, and the demand for oil, as much as a reorientation of objective record of geographic space.

Maps presented something like vestiges of the indigenous past of places past–“Ye say that they all have pass’d away/That noble race and brave;/That their light canoes have vanish’d,/From off the crested wave/ . . .But their name is on your water,/Ye may not wash it out,” wrote Lydia Sigourney in Indian Names; Whitman described “the strange charm of aboriginal names” that “all fit” the places, rivers, coasts and islands that they describe as adequately as onomatopoeia–“Mississippi!-the word winds with chutes–it rolls a stream three thousand miles long,” yet most names of “Indian” origin, if avoided by early settlers, to be absorbed y American tongues as they grew emptied of indigenous title. Yet the removal or blanching of indigenous geographies suggests a new relation to extracted spaces, under the ground, unanimated and sensed, remotely, for a commodity value cast as objective in its blueness, as if to convert space to a calculus of market values that exists less objectively than as a grounds for its extraction and universal needs of energy consumption, as if the probability of access to products provides the universal index of meaning indicated by shades of blue.

This relation to space, if akin to John Locke’s classic description of the value of cultivated and enclosed land that Anglo settlers are able to create in “America”, gaining value by cultivation that they would otherwise lack among indigenous, is a classic move of appropriation by means of revaluation, stated as so self-evident that it seems not an act of revaluation, but recognition of opening the “fruited soil” or “petroleum reserves” to global markets–whether markets of a global Atlantic trade for sugar, cotton, and that reveal their intrinsic value in ways not apparent to their previous occupants, by a re-designation that will elevate the land’s value of lands as the demand and need for products washes over them, to benefit “all” mankind.

A similar logic haunted how Henry David Thoreau described the benefits of displacing indigenous inhabitants, in 1861, as a historical logic that might be found in the land. For Thoreau transitioned from how “the civilized nations–Greece, Rome, England–have been sustained by the primitive forests, which anciently rooted where they stand” reasoning that it was evident that such nations “survive as long as the soil is not exhausted,” and as nations are “compelled to make manure of the bones of its fathers,” prevailing wisdom agrees “It is said to be the task of the American ‘to work the virgin soil,’ and that ‘agriculture here already assumes proportions unknown everywhere else” in its exorbitant wealth.

The American story is a dialectic process of agricultural transformation of landscape by which “the farmer displaces the Indian even because he redeems the meadow, and so makes himself stronger and in some respects more natural” as fields were transformed by plough, hoe, and spade. And while we often see these claims as “modern” in their reliance of using maps to claim lands for a global energy market–if it is only the latest commodity to secure unchallenged status as a public good of global consensus. The reservations on which most indigenous were confined as deemed less valuable or desired land, in a process of geographic displacement and forced migration that began after the Gold Rush in California but could be traced to the arrival of planters in the southeast coast of the colonies, but was suddenly creating a run on property claims in the Sierra foothills to which the world’s eyes seemed to turn, as emigration to the Gold Country set a new standard for mapping the global ties to the Gold Country long before the accurate geodetic determination for extracting a universally acknowledge good.

Important Directions to Persons Emigrating to California

The periplus-like legend that was paired with the composite hemispheric and regional map of Upper or New California offered guides for enterprising travelers to set eyes on the newly mapped western state, the accompanying legend acknowledging the lodestone, as “gold mines of California . . . known to have existed in the sixteenth century, for as early as 1578, about the time Sir Francis Drake made voyage to the coast,” Jesuits had gained possession of “certain tracts which they knew of more than ordinary value,” whose value they depreciated by false reports: but now the map delivered this valuable insider knowledge that never commanded attention of the Spanish court, but was now safely in the hands of whoever owned the map to allow global emigration to the “fertile and picturesque dependent country, [distinguished by the] mildness and salubrity of its climate” that is with a “latitudinal position that of Lisbon” whose global geographic position makes it one of the most desirable “point of commerce, in this or any continent,. . . destined to be one of the greatest disbursing depots in the world.”

The global circulation of goods were spectacularly invoked to displace native land claims in wyas that didn’t even require geodesists, as a spectacular conjuncture of capital displacing land claims. For the 1879 mapping of global routes to the Gold country, the year that the coutnry adopted the Gold standard, oriented audiences ready to get rich quick the necessary “important directions” for orienting themselves to claims in the Gold Country of California–the same years at which “Indian” reservations were effectively marginalized outside the state, when Francis Amasa Walker remapped the western states to cast white populations in mauve apart from the indigenous hunting grounds or reservations set off in bright orange in official maps drafted as Commissioner for Indian Affairs, modeled on the maps on rainfall and natural resources he had compiled for inclusion within the decennial U.S. Census of 1870.

If these rigorously bounded reservations and hunting grounds are clear lines of jurisdiction determined by latitude and longitude, preserving tribal names situated in a clearly if gratuitously demarcated “Indian Territory,” the surveyed bounds confirmed a broad displacement of indigenous across western states.

The map placed the Gold Country in national if not global visibility, before GPS, or geodesy, centered on placing the valued commodity of the day in easy reach. The topically colored region–tinted in ways that hinted the riches bound to be seen underground–was suddenly in access of all, advertised as able to be reached by boat via Panama or Cape Horn or the midwest, invoking an early globalization to erase and displace local land claims. The “gold regions” were in fact long inhabited Indian lands. The map shows the region as if mapped anew, soon after the first massacres of indigenous in a spate of “Gold Country” maps confirmed the voiding of all title tribes might have had, with little trace or reminder the historic presence of the peoples who once lived in the region save by the historic resonance of evocative place names, Longfellow style. It was shown ready for resettlement–or “settlement”–in growth small towns as Sacramento, later the state capital, without reminder of the migrant tribes resettled on confined inland land, far from the coast or the fertile Central Valley. One can only sense a whiff in almost mythical regions (as Yuba and Yola) or the aptly named “El Dorado” attracted eyes to rolling hills where riches were to be made: regions today best known not for gold but fires, the over-settled Wildlands-Urban Interface.

The currency gold gained as a universal standard in the first years of the gold standard adopted that very year treated gold as a universal logic of land claims for areas effectively prepared to be rendered as open to settlement, having been purged of inhabitants, and erased from the maps that were sold of “the mining district” in increasing numbers, that can be cast as a growing cartographic literacy purging California as a multi-ethnic state.

from Jackson’s Map Of The Mining Districts Of California 1851

Courtesy David Rumsey Map Library, Stanford University

The relatively rapid shift in title to the land from 1848 that would be all but accomplished within thirty years, as by 1879, the American Genocide all but completed some years earlier, two decades after Anglo newspapers opened an unofficial “war of extermination . . . until the last redskin of these tribes has been killed” to take the gold-rich lands as their own, and gold the national standard invested it with global currency and a logic of land seizure.

Lands opened for prospecting were not marked as being cleared by permanent displacement, a massive resettlement effort that prefigured the displacements of the twentieth century, but focussed on the lustrous gold arrowhead hand-tinted in an 1879 map as a destination promising the bounty of extractable wealth from its rivers, mountains, and valleys ready for the taking by all able to pay costs of passage as a near-universal “right” of access to this map that shows California as if island, shown at larger scale in an odd frame situated in the Pacific, as a new land where new rules applied, but where all could access by shipping channels from other continents, drawn to this one site by the lure of the glowing gold ready to be pried from being lodged in the region of California inland from the coast. west off the Great Interior Basin, as the world must have been suddenly heading and focussing attention on the mecca of the newly affirmed universal standard of financial currency in a globally contracted world.

Ensigns & Thayer. New York: 1849, courtesy Donald Rumsey Map Center, Stanford University Library

The long tradition in such maps was to exclude an indigenous perspective. But what might it be like to map from the other side, as it were, less in terms of land claims of property than inviting a greater negotiation of the land use with the longstanding use of land that indigenous communities have often long used?

This question, long pressing but rarely recognized as pressing to address, was subsumed by the logic of capital and the demands for extraction, either in the maps of oil extraction in the header to this post, or the Gold Country maps, placing less emphasis on boundaries than the ability to target, access, and export to a market whose demand trumps the local customs of the inhabitants of the place–far from the Far Utah Indians living far inland, or “Utah Indians,” but offering a separate plot that immediately attracts the viewer’s eye to rest on this region of “Upper or New California” newly open to all who sought all that glitters, as if it were a land of luxury, an island generating huge wealth for the taking, even if it wasn’t an island at all.

But California wasn’t at all an island for practices of forced displacement or territorial claims,–more like a workshop or staging zone for practices of extermination and land seizure of the twenty and twenty-first century. That maps might preserve the memory in which indigenous not only live, but long inhabited, could recast the lands as part and parcel of a sense of self, long obliterated or erased from earlier maps, whose content we would do well to interrogate and examine in terms of the erasure of the very idea of the existence or collective memory of earlier land claims.

And as Thanksgiving comes as an opportune time to seek deeper truths than are evident in the map of acknowledged tribal lands, or the violence of the longstanding aims of eliminating the presence of indigenous from the map, this post took a deep dive, as it were, in musing about the possibly preserving native claims in maps. For many indigenous in North America, indeed, Thanksgiving is better known in indigenous communities as a National Day of Mourning, the displacement of indigenous land claims from the current maps of nations has offered little space to negotiate land rights.

The new opportunity to map a persuasive representation of past land use has provided a new cartography akin to a pharmakon, remedying the erasure of indigenous presence in crowd-sourced remapping platforms, whose overlapping boundaries of tribal space may derive part of its compelling power and increased impetus from the erosion of “boundaries” in the mapping of the nation state,–if not of the integrity of the nation state as a semantic unit of clear bounds. Might the platform that promotes a sense of the blurred nature of indigenous space on TribalLand.ca be more than a purely virtual representation of an affective relation to the lost title to lands, but eventually be effective in giving rise to something new in the shifting structure of the nation state, where the place and space of indigenous inhabitation deserves increased prominence than it has long had? Such are the questions posed as the longstanding inequities of dispossession of lands, heightened perhaps by recognition of the failures of custodianship of environmental health, but providing increasingly undeniable dilemmas not only of the naming of place, but the ghosts in the closet of our civil society.

As the nation wrestles with its troubled pasts, and the ethics as well as objectivity of mapping space, as well as the danger of environmental devastation on several fronts, the resource of NativeLands opens new questions of how we understand our relation to the land, and the place of engaging indigenous inhabitants in collective decisions of land use, from the leasing of mineral rights to the potential devastation of oil pipelines and energy transport, or underground fracking and petroleum prospecting. It might be a way of using the very tools of geodetic mapping that extractive energy has profited so much to create a new forum for interrogating land use, and empowering indigenous communities as stake-holders to questions of property from which they were long excluded.

The attempts to crowd source a layer of the boundaries of indigenous land claims on TribalLands.com, noteworthy as suggesting a new ethics of mapping, both with a clear historical online apparatus that serves as a dynamic legend, and the refreshing colors of a distinct cartographic palette of light lavender, green, violent, and yellow that broadens the divides of territorial claims sharply-edged cartography of the past. The oddly open space in these maps are not legally binding–or rooted in law–but offer a poignant and indeed healing cartographic pharmakon of ghost-like claims we are currently learning to negotiate with the lines of jurisdiction or sovereignty inherited from the past. While the web map is finally turned to only in §8-14 of this post–perhaps a section that deserves to be its own post!–the time-laden nature of obscuring native or indigenous claims are examined as a cognitive problem and historical project in earlier sections, turning to the complex place of indigenous in California’s formation as a state, before the Native Land maps are examined as a productive undoing of the historical violence worked by the marginalization of native land claims–effectively a cartographic distortion and omission that has deep logic and cunning roots.

For mapping, and all mapping, fascinates as an ethical project of knowing, as much as for its accuracy and persuasive form. If all mapping is time-bound, this remapping of land claims is not based on erasure of settler sovereignty, but an opportunity for deeper dialogue with the past–and with the relation of maps to remembering–that might offer a way to produce a responsible acknowledgement of the difficulties of the notion of sovereignty, and indeed. a new way of negotiating the fraught history of the past maps predicated on a logic of displacing native or indigenous inhabitants, and eradicating indigenous land claims.

1. The recent emergence of web-based tools and maps attempt to counter increased dangers of encroaching upon ancestral claims, by offering tools that might effectively empower indigenous claims if not to legally binding records of sovereign space, of the inhabitation of lands that property maps often elide. The many treaties of land–and history of land cessions–that have reduced North American indigenous land claims have found a powerful response to try to address, if not to meet the devastating precision with which remote sensing and geolocation tools have provided indices for extracting minerals, mining, and drilling for petroleum, if not in a legally recognized form, by providing powerful set of tools for asserting and envisioning the deep historical value of lands increasingly at risk of irreversible ecological and environmental damage.

If land has been allocated or reallocated for energy extraction in recent years, the definition of mineral reserves echo the “doctrine of discovery” that defined the boundaries and ownership of land long occupied by naive or indigenous inhabitants has posed questions of the existence of proofs to prior claims–the basis for staking indigenous claims. The very existence of large numbers of oil and mineral deposits across the Canadian north coincide most problematically with marginalizing indigenous knowledge claims, raising questions, as Global Forest Watch has helped us visualize, of the conflict between resolved treatises and expanding land claims being negotiated to access mineral deposits, most of which lie in areas covered by abrogated historical treaties. While the language and logic of extraction depends on the localization of mineral deposits on isolated points, boundaries, and edges, the blurring of maps of ancestral lands first in Canada, and now globally, posses a shift in perspective on the bounding of appropriated space that upsets the logic abstracting property claims from a historical context.

Indeed, the tabulation and mapping of Reserves, First Nation Settlement Lands, Inuit Owned Lands, Tlicho Lands, Inuvialuit Lands, Gwich’in Lands, and Sahtu Lands offers a dynamic mapping of “aboriginal lands” absorbed into the commonwealth at an earlier era–local land claims challenged and intact landscapes challenged by the globalization conundrum of the corporate and often national elevation of “global” over local needs.

The increased demand to reconcile nationally recognized indigenous land claims and ancestral lands poses something of an epistemic and a political challenge for the twenty-first century, unable to be recognized by purely cartographic terms, but which cartographic contrast promoted by indigenous-led claims for local governance and land-use have put into relief as an ongoing engagement. The parallel existence of these different geographies suggest a coming crisis in the need to resolve limited recognition of federally recognized claims with the existence of an increasingly visible collective call for recognizing ancestral lands, now crowd sourced on the vibrant webmaps of Tribal Lands, maps that suggest the far greater haunting of nations by the seizure of indigenous lands on which they were founded.

If the allegedly limited scope of lands federally recognized in Canada–while far more expansive than in the United States, a mere .2% of the territory of the expansive nation to the north–

–the spectral nature of indigenous nations that has been mapped on NativeLands.ca demands to be seen as haunting the nation on the day of American Thanksgiving, and provides an entree of sources to turning to some serious introspection on the territorial configuration of the

Indeed, as we move to living in a globalized economy that places a premium on logics of extraction, recorded and determined by remote sensing form satellite space, maps of mineral resources threatens to alienate traditional knowledge claims across a global setting.

The pressing crisis of mapping indigenous lands seeks to balance the claims mad in maps privileging “discovery” of and extraction in the petroleum industry’s identification of oil deposits over and above local land claims that has threatened the erosion of ecosystems in huge swaths of formerly forested lands swiftly reduced native land claims in Canada to a mere .2% of the nation, as we come to terms with the destructive role maps occupied in vacating native claims to land-ownership by voiding all memorial value of indigenous land-use.

The story did not begin in any way with the global demand for energy extraction that is all too often phrased in gilded terms as “energy independence,” even if this “independence” is primarily for the wealthy extractive industries. Maps help sell plans for energy extraction to the public in suitably patriotic terns as a “freedom” from global energy markets, confirming the recognition of the rich “basins” of sediment at home and offshore, as if it awaited the bravery of a scratch-‘n’-sniff scraping of their color-coded surfaces might easily reveal its oily petroleum odors that would cascade to a populist demand for cheaper prices at the pump.

Although the map below shows the extent to which mineral claims lie in the boundaries of Canada’s boreal forest, the conflicting claims of property rights that appeared long settled in historical or modern treaties seem punctured by the speckling of claims that suggest an intense competition for legal recognition of mineral claims. It might understood as imposing a distinct logics to understand space, one covered by ceded land, and one covered by a sharp-edged rationality of geolocation, rooted in a geography of extraction that takes global markets as its common denominator. As we balance the collision of such conflicting cartographic rationalities, the claims of ownership of ancestral indigenous lands may yet gain new purchase and new currency, as the contestation to access to newly valued lands that have emerged as properties–and cast as properties of the “common good”–has become increasingly intense.

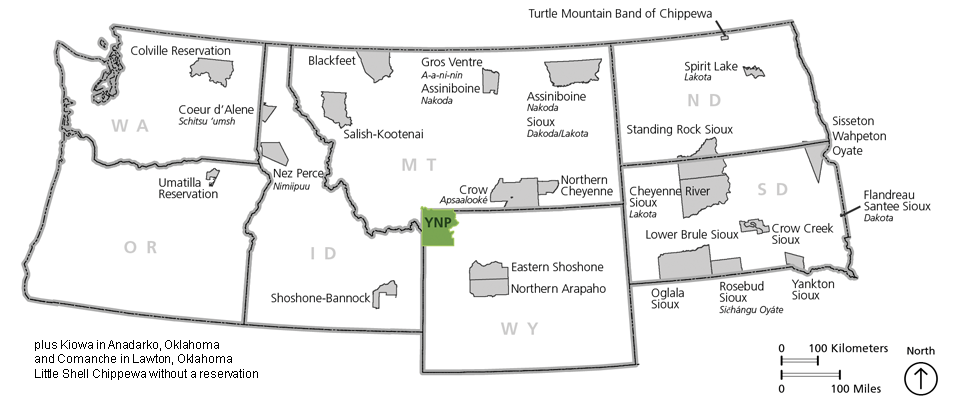

The permutations of the “common good” as a logic for land seizure is not unfamiliar, as much as it has been intensified by the renegotiation of past treaties with indigenous or aboriginal communities, whose very name seems to acknowledge their remove from the global market with more than a conspiratorial wink: it recalls the expropriation of longstanding land claims across the western United States of lands under the guise of the benefit of the “public good” from the Gold Rush land leases to the “wilderness” area of National Parks, both in Canada and the United States, as public lands; one thinks not only of Yosemite but Yellowstone, as “public” lands that not only rested on expropriation, but as areas areas where contested land claims were erased or subsumed in a “public good” first and foremost in “parks” where the ostensible “sharing” of landscapes identified as wildlife were able to essentially void claims to sovereign status by being affirmed as “wilderness” areas indigenous and settlers might equitably share.

This historical dialectic of displacement will bring us to the Harvest feast. FOX commentator Laura Trump, latest defender of the Trump political brand, has grown into the part by calling out the designs of those to “take away our traditions” seeking to “chip away” at America by those who “don’t want us to any shared traditions like Thanksgiving” who seek to disrupt the traditional holiday by allowing the price of the festive meal to rise by inflation. The turkey is perhaps the atavistic bird of the wild–if modern turkeys are farmed–but the Trump in-law begged viewers to grasp the extent of the failure of government in the failure to protect turkey prices from rising a few dollars as an existential threat of “turning this country inside-out;” higher prices of turkey, warned the former President’s daughter in-law, as a way of “fundamentally transforming this country, . . . to make sure you have no commonality whatsoever,” or “common ground.” Indeed, “I guess we’re lucky they’re letting us have Thanksgiving this year,” she put herself in the disadvantaged minority, alerting viewers that even if the “shared traditions” being threatened at the register “might seem a little funny and ridiculous,” pointing to how inflation might eclipse Thanksgiving festivities and leave many resigned to skip tables laden with bounty in the past given the rising costs of the bird as a sinister plot to disrupt the Harvest Feast–“‘Oh, don’t have a turkey, then people won’t come over’”–as if intending to rob the Thanksgiving table of the entitled harvest feast–even if the “wild” turkey consumed on Thanksgiving is hardly the most popular of the carb-indulgent foods most anticipated in America. Pace Laura Trump, if on most Thanksgiving tables turkey may be a dramatic center, performatively carved, we anticipate preferred side dishes on the table like mashed potatoes, stuffing, mac & cheese, cream corn, deviled eggs and biscuits.

The turkey remains an atavistic reminder of the semi-wild nature the meal once had, as the slaughter of the massive birds offer a metonym for the cultivations of fields for holiday bounty beside squash, root vegetables, or the cranberries once harvested from New England bogs. The filling of plates is a reminder of the taking possession of the land by transporting the wild turkey to the crowded dining room celebrated as a harvest offering had become recast in Trumpland as evidence of dispossession of settler privilege.

The meal that enacted a domestication of the land had peacefully appropriated New World foods for the public good in a settler ritual, recalling the role of the harvest and planting of crops central to John Locke’s discussion of settler’s rights to property claims in the New World. If Thanksgiving is an offering up the fruits of the land, the pleasure in the planted harvest is a confirmation of sorts of the voiding of indigenous title and land claims. To discuss the scale of such disenfranchisement with John Locke’s notion of a civil contract may seem pedantry–if not heavy-handed pedantry–Locke had elevated the role of property in several stages of the Two Treatises as a beneficial introduction to the indigenous people of the Americas who had no concept. In framing the settlement of the Carolinas, Locke consulted maps in Shaftesbury’s library that show no evidence of indigenous habitation or cultivation–among them, the Blaue atlases of America’s coast from the mid seventeenth century, whihc suggested lands that were almost uninhabited, waiting to be farmed for produce.

Land in Future Carolinas/University of North Carolina

The displacement of indigenous provided a logic of the expansion of the nation state even to infertile lands, by the late nineteenth century. and odd words to privilege to describe the theft of native lands, the defender of land speculation in the swampy Carolinas, newly mapped in the New World. In defending land speculation in land of the swampy Carolinas for his patron the Earl of Shaftesbury, the enlightenment thinker John Locke may well have studied the newly mapped lands in the New World, finding clear and considerable benefits of converting unused lands that had not been farmed for Atlantic commerce, growing a “public good” and allowing readers to find remove public benefit from the indigenous land claims. Locke’s presence in the post-1619 years might well remind us of the global economy of which he was a resident, and a contemporary of Haitian separatist Toussaint Loverture as well as Thomas Jefferson.

For Locke quite clearly perceived the necessity of justifying displacement of indigenous by settlers as inherent in the definition of property. Locke seems to have briefly struggled–and helped his readers as they struggled–with the displacement of indigenous inhabitants in a logic of settlement, but Locke succeeded in explaining how the introduction of property claims effectively affirmed the public good and would be worth accepting to further it. Far from the famous image of the fort of Jamestown that predated the first arrival of enslaved Africans in 1619, of settlers in a fortified compound as an outpost in a land ruled by Powhatan, chief of the indigenous Tsenocommacha tribe, in this anonymous map of 1609, of a fort on the River James, the land was surveyed as ready for open settlement.

The national parks movement itself effectively functioned to subsume native claims in the prioritizing of public claims of access to lands on the edges of inhabited space, fit for the “wild” or savage lifestyle of the indigenous and edifying visitation of lands by those with need for relief from the pressures of urban space. The traces of indigenous people’s historical residency were obliterated and vacated, as the longstanding presence of former sacred spaces, sites of hunting, fishing, or community were blended into the new “wilderness” areas protected by the state, rather than regarded as sites of residence, filled by longstanding traditions of a relations of custodianship of the land.

The twentieth century creation of “wildlife” spaces in national parks vacated spaces of sovereignty and ignored indigenous land claims, in the guise of setting them apart from modernity, as spaces the long marginalized experience of the indigenous might co-exist. This was tre in the largest parks, as Yellowstone, from the 1878 Bannock War, the result of a string of disrespected treaties, through the Sheepeater War in 1890 ended indigenous presence in Yellowstone; former battlegrounds with Shoshone, Crow, Blackfeet Umitilla and Bannocks were nationalized in the first “national park,” converting lands fought over with the Nez Percé, Bannock, and from homelands to “public lands.”

Bannock with Chief Tendoy in Ancestral Lands Converted to Yellowstone National Park/Wikimedia

The occupation of lands remembered by song, dance, and other narrative forms did not stake clear edges of territorial boundaries, but if their traditions were at times placed outside of history in ways we are only slowly coming to recognize, ways of occupying forests offered little common ground with settler demands for many years. Is it any surprise that the drilling for petroleum in Iqaluit, in the province of Nunavut, since this early October has contaminated tanks of treated drinking water supplies with diesel fuel to render it unsafe for consumption either boiled or filtered; Canada’s government felt it was safe for bathing or washing dishes, but as temperatures fell, leaving 8,000 the residents left without potable water haunted by diesel fuel smells permeating their tap water, as health advisories urged pregnant and elderly to avoid washing–and the only accessible river water of the Grinnell River starts to freeze.

The conversion of public lands in the American West paralleled the aestheticization of national parks, famously aestheticized by Ansel Adams and Carleton Watkins as open wilderness, was concealed as a monumental loss of land as it was cast as wilderness, rather than lands from which settlers pushed historical inhabitants. Can these land claims be excavated and remembered, let alone recognized and preserved, by contemporary cartographic tools? These issues are not only academic: if National Park System director Jonathan Jarvis was dedicated to rebuild relations to Indigenous who used lands in the national park system, from allowing recognized nations to gather plants or visit sites within the park grounds, from the Navajo whose ancestral lands were included in the Canyon de Chelly national monument to the Umatilla who have advocated recognition of “tribal perspective” of “taking care of the land, so the land can take care of you,”the place of tribal nations within the national parks” will be re-judicated during the Biden administration for the first time since Jarvis left his post in 2017. The inheritance of these lands are complicated, however, coming one hundred and fifty years after National Parks were systematically built on ancestral lands dispossessed from Indigenous communities.

2. It is not by chance that Locke found, in the First Treatise on Government, a foundational document for the nation, to find the clearest illustration of the value of the role of labor in extracting “products of the earth useful to the life of man” in how “several nations of the Americans . . . are rich in land and poor in all the comforts of life,” furnished by Nature “as liberally as any other people with the materials of plenty–i.e., a fruitful soil, apt to produce in abundance what might serve for food, raiment, and delight, yet, for want of improving it by labour,” without “a hundredth part of the conveniences we enjoy,” so that their king himself is “clad worse than a day laborer in England.”

Lockes concept of “several nations” becomes a cartographic plurality on the NativeLands website. The notion of several nations is reinscribed in the NativeLands maps in ways that actThe relentless economic logic of extraction and global markets was present when Locke explained to readers that the “benefit mankind” received from the cultivation of whose land “natural, intrinsic value . . [is] possibly not worth a penny” not only will always be greater, Locke argued, but that if “the profit an Indian received from it were to be valued and sold here, at least I may truly say, [is worth] not one thousandth” (I: 43). Claims for the absent of indigenous apprehension of the commercial value and of property runs deep: Ralph Waldo Emerson, no less, lamented in April, 1862, that indigenous “have not learned the white man’s work” by the late nineteenth century; this defender of liberties lamented that “the Indians have not learned the white man’s work” that is a sign of compelling and redeeming virtue, but must arise in the tribe itself; instead, “the Indian [becomes] gloomy and distressed, when urged to depart from his habits and traditions,” argued this abolitionist, “overpowered by the gaze of the white, and his eye sinks,” without a leader with “the sympathy, language, and gods of those he would inform,” able to impart the true contentment of a stable residence–not property but real estate, “the effect of a framed or stone house is immense on the tranquillity, power, and refinement of the builder,” foreign to the “nomad [who] will die with no more estate than the wolf or the horse leaves,” so foreign is a sense of property to them.

John Locke evaded the paradox in claiming lands in the Americas, by casting the act of taking possession as rooted in the master-paradigm of the institution of private property. For no “clearer demonstration” existed of how labor added value to acres than an acre “planted with tobacco or sugar, sown with wheat or barley, and an acre of the same land lying in common without any husbandry upon it.” Locke wrote proponent of the plantation system in the Carolinas in need of defense for the project of colonization, the Earl of Shaftesbury, as his patron was Secretary in the Royal Council on Trade and Plantations in the Carolinas, advocated expanding plantation system in the Carolinas, arguing in 1673-5 that peopling “New World” by settling overseas possessions in plantations would benefit Atlantic trade. Locke planned the constitutions of the Carolinas, he consulted maps in Shaftesbury’s library that show no evidence of indigenous habitation or cultivation–among them, the Blaue atlases of America’s coast from the mid seventeenth century.

Not only the study of maps compel us to examine Locke in a perspective of Atlantic history that the Blaue atlasses might offer help contextualized the land grants that Charles II, returned to the throne, south of Virginia to Spanish Florida–between thirty one to thirty six degrees north latitude, from Atlantic to Pacific Oceans, renamed in honor of Charles I, “Carolana.” The region was to develop as a residence for the many royalists living in the Barbados, rich off the cultivation of sugar plants imported to the island in the 1640s, to emigrate; it provided needed grounds as they sought to remake themselves as planters on its arable land. They soon petitioned in the 1660s the monarch secure a thousand acres they might purchase for cultivation and the transatlantic trading of goods from lands that had earlier gone unfarmed in a systematic manner to increase their usufruct.

When the Earl of Shaftesbury opened his library to Locke as he desired to advocate expanding the plantation system to grow England’s trade through settlement and large-scale programs of cultivation. The logic of Locke’s argument on the origins of property of course supported settling, tilling, and cultivating the land among a new generation of English planters as a project of increasing the value of the land. And although this post on indigenous lands may seem to defer to the enemy, the very claims that corporations–and the governments who have allied agendas of energy extraction with the public good–not only reiterate the Doctrine of Discovery, now based on the discovery of oil and gas deposits that remote sensing has allowed, but from how Locke affirmed the greater benefit that the public good derived from cultivation by taking title of land ownership in the areas indigenous once dwelled, tilling and cultivating the lands where indigenous had quite differently mapped–but with no acknowledgement of those maps, drawn not on sharp lines of enclosure, but that he defined as Secretary of the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations and private secretary of the Lords Proprietors, by an absence of industry, ownership, or property when he drafted the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina (1669), some twenty years before writing the Two Treatises (1689), that granted settlers the status of “absolute Lords and proprietors” of the region as he sought to attract planters to cultivate productive plantations in the swampy Carolinas, a distinctly boosterish attitude to the future patent holders, notoriously boasting that “every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves.”

Locke promised such a scale of dominion years before the massive expansion of moving human cargo by the Royal African Company from Africa to the New World led him to condemn enslavement outright. But in his speculation of the emergence of man from the state of nature, the Americas and Carolinas continued to provide a powerful model for the production of value in political society. Locke argued this benefit began not only from husbandry, but the introduction of property in a political compact, an introduction that would allow value to be extracted from the land. Locke turned to America as a figure of speech to designate the “state of nature” out of which civil government emerged that was most on everyone’s minds as a sight of the absence of money or fungible goods: “In the beginning, all the world was America,” he explained to readers, more; “for no such thing as money was anywhere known.” We smile at the conceit of the Americas occupied in readers’ geographic imaginary as a place foreign to private property, or where only political authority might introduce the security of property to inhabitants living in a State of Nature, removed in Locke’s eyes form civil society. But Locke’s affirmation a security of property–that might be mapped in clear lines of property, he omitted to say, yet left tacit–resulted from civil society, secure from “continual dangers” faced in the state of nature, in Two Treatises of Civil Government (II, 9:123-24). If not, claims to property would be always wanting protection.

The logic of land settlement would continue to justify legal patenting land claims in California from 1851.

3. We once smiled at how Locke regarded America as an archetype of the accelerated civilizing process property might perform for Locke, as if indigenous were incidental to his argument. But his rationalization for seizing property was the clearest basis for the “doctrine of discovery” that is so often cited as fons et origo for the preservation of title to land claims of California settlers, itself able to boost racist claims. It offered a noble justification to preserve title without the consent of those indigenous who lived on the land by 1851, which cast indigenous inhabitants as so many “dependent nations” not yet able to claim rights of property on their own and not yet in a political society–affirming over two hundred existing “land grants” that has been argued to have propelled the development of California to what has recently become the largest economy in the world–whose acknowledgment of private land claims follow the outline of Spanish land grants, to be sure.

They reveal the rapidity by which the state patented private claims from the mid-nineteenth century. They offered title to lands not only around San Fransisco and Los Angeles that from 1861 had rapidly devolved land ownership, and the new geography of smaller agrarian plots to the north and larger land claims to the south in private claims patented 1876-80 and later.

“California’s Land Claims,” Hornbeck, 1979

The expansion of ranchos in California demand to be told as a story of accelerated dispossession. Even if Locke had to consider if conquest “convey’d a right of Possession” including “Right and Title to their Possessions,” he effectively vacated claims of indigenous he placed in the State of Nature, and might affirm the erasure of indigenous claims on the maps he consulted in London: “there being more Land, than the inhabitants possess, and make us of, any one has liberty to make use of the waste,” he proclaimed with apparent delight at resolving an apparent contradiction in II:16 of the Treatises on Civil Government, offering what Barbara Arneil has aptly termed an “economic defense” of colonialism which later colonialists cited in arguing that indigenous land claims would cede before evidence of settlers’ cultivation of lands–the enclosure and active cultivation of lands were tied to their settlement and fully possession by the state, in a huge transfer of property that remade the topography of the state to the benefit of Anglo settlers by disadvantaging indigenous pushed inland and to higher and drier ground.

from Hornbeck and Fuller, California Land Patents /digitalcommons.csumb.edu/

The expansion of ranchos across most of California’s most fertile lands created clipped boundaries of property lines in the patents for ranchos that demands to be viewed from the topography of the raised Sierras where most native populations were driven–a “high country” later naturalized in film–far from ancestral lands, but provided the historical backdrop for future attempts to remap indigenous presence in the state, and indeed to excavate the lost geography of indigenous inhabitation land grants erased.

And although indigenous systems of government and property may be in fact beneficial alternatives, they are absent from maps of the open land of the Carolinas that seems to await cultivation in the open spaces mapped in Blaue atlases as inviting canvasses without any stable or fixed property lines.

It is difficult to call Locke a disinterested observer, after all: he was an investor in slave trade, and a proponent of the expansion of plantations in the Carolinas as he affirmed the right of property in civil society in Two Treatises on Government. Locke argued that the origin of property lay in the enclosure and taking possession of common lands for private gain as a process of natural evolution of land claims, in which “As Much Land as a Man Tills, Plants, Improves, Cultivates, and can Use the Product of, so much is his Property“–the very property rights that were the natural law by which English planters would bring the unsettled Carolinas.

The expansion of colonization to the Carolinas offered an illustration of “submitting to the Government of a Commonwealth, under whose Jurisdiction they would be subject” as an archetypal civilizing act of the common good. Locke claimed this was not to occur by means of injuring or disadvantaging “another in his Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions,” but the argument helped indigenous peoples were seen by Planters as not having taken advantage of the land that was “unsettled” or not cleared was not taking possessions away from those who had continued to live in a state of nature–even if doing so had no moral counsel. Only by consent to enter into a government is to consent to lose the ability “right to regulate the right of property.”

John Locke’s advocacy of the plantation system that the Earl of Shaftesbury advocated was able to accommodate enslavement, as much as Locke assumes the owner of property to practice Christian charity, but offered a logic of possession on a scale that Locke was unable to foresee–even if he saw America as a vast and unsettled expanse free from the cultivation in which English planters might offer to apply. The duly embarrassed acknowledgment and gradual recognition of how Locke’s philosophy of liberal society in fact actively accommodate enslavement in a foundational theory of liberal rights stands, retrospectively, as a sort of reckoning of the late 1980s, stemming from investigation into his involvement in the Carolinas. Despite a Fleur-de-Lis on the region, French had plainly failed to cultivate the land as property, and one might “plough, sow, and reap” to take possession of uncultivated regions that remained in the state of nature: it was more than evident by the 1660s “the French . . . have made no considerable progress in planting” to which the English would be particularly suited.

detail showing the “Apalatcy Montes auriferi” and rich fields for Planters

If Blaue’s map located mineral wealth in the “gold-rich Appalachian mountains” that might be mined in the New World, Locke seems to have reacted to the open fields nourished by rivers that ran up to them as fit for transformation by cultivation to the planters. One might almost imagine a similar point of view for those on the galley shown arriving in the Carolinas as it anchored offshore. The lands seemed mapped as without inhabitants and open for settlement–able to be taken possession of by planters if already mis-mapped as land of a French domain. The absence of all acknowledgement of lines of property or land ownership suggests an absence of transformation to a public good, or any recognition, in Blaue’s map, of Dominion over the land, notwithstanding the Fleur de Lis, that only acknowledges the failure of the French to have enclosed or cultivated the same lands. If Locke asserted that value of land derived from labor, he omitted that claims to land derive from force, asserting that the appropriation of land rights are justified by redistributing the goods benefit society–even if he was forced to note with some reservation that dominion is among the “first . . . of the vicious habits” that must be curbed.

Perhaps looking at Blaue’s map provided a basis for the natural process Locke described of those who will “make themselves Members of some Politick Society,” and leave that State of Nature, and in leaving that state of nature departure “give us Property [but] also bound that Property.” The proximity of the three-masted ship to the coast of the Carolinas look out at the rivers that nourish the Carolina plains, as if to suggest the imminent possibilities of bounding the rich region they observed as property, transforming it from the state of nature in which goods and resources remained common property, and but by submitting to a commonwealth to protect and preserve property.

Having finally disposed of the metonymous turkey, am digesting this (unmediated) feast of historical greed and epic hypocrisy, notably in California and the Carolinas.