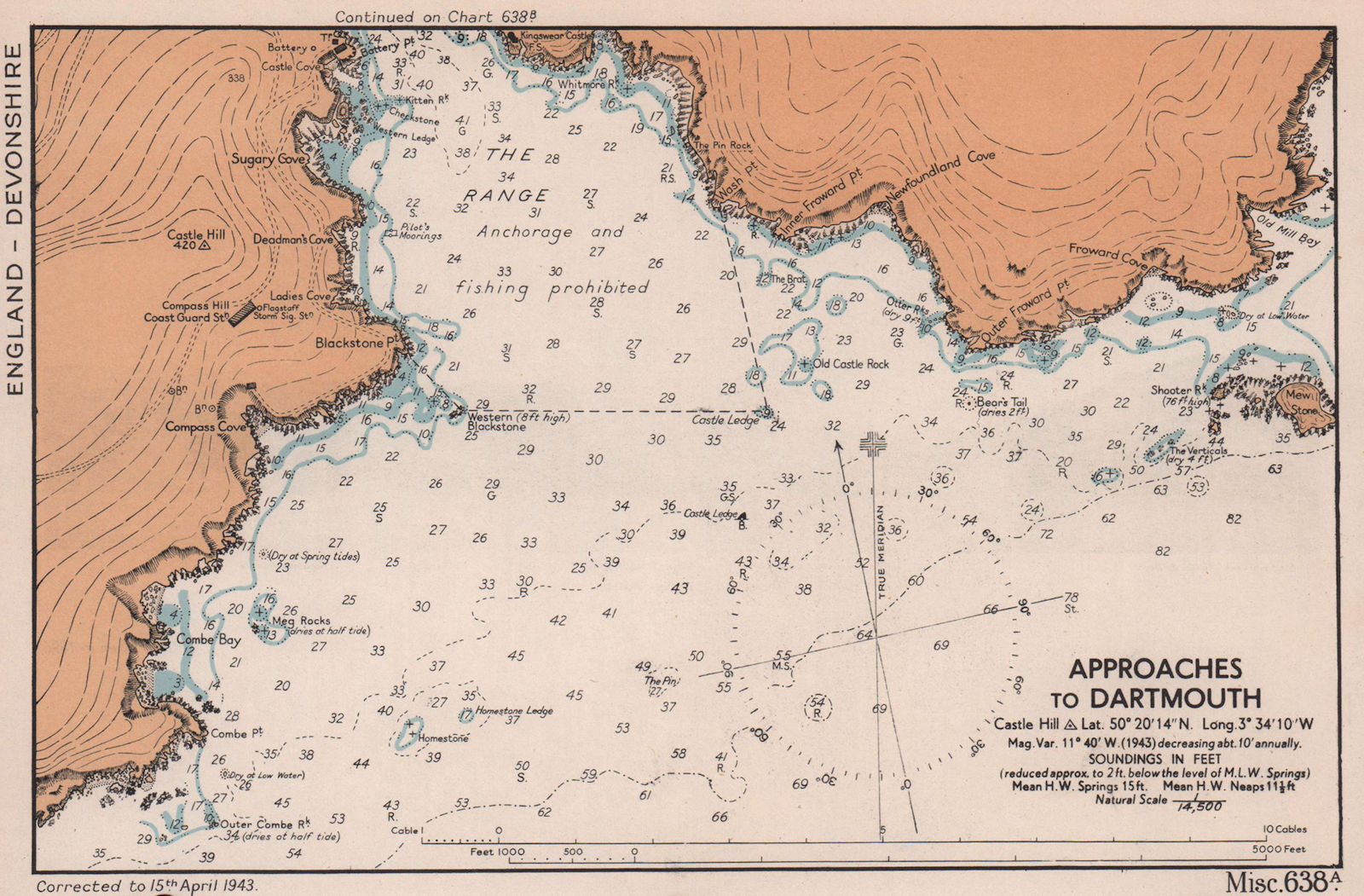

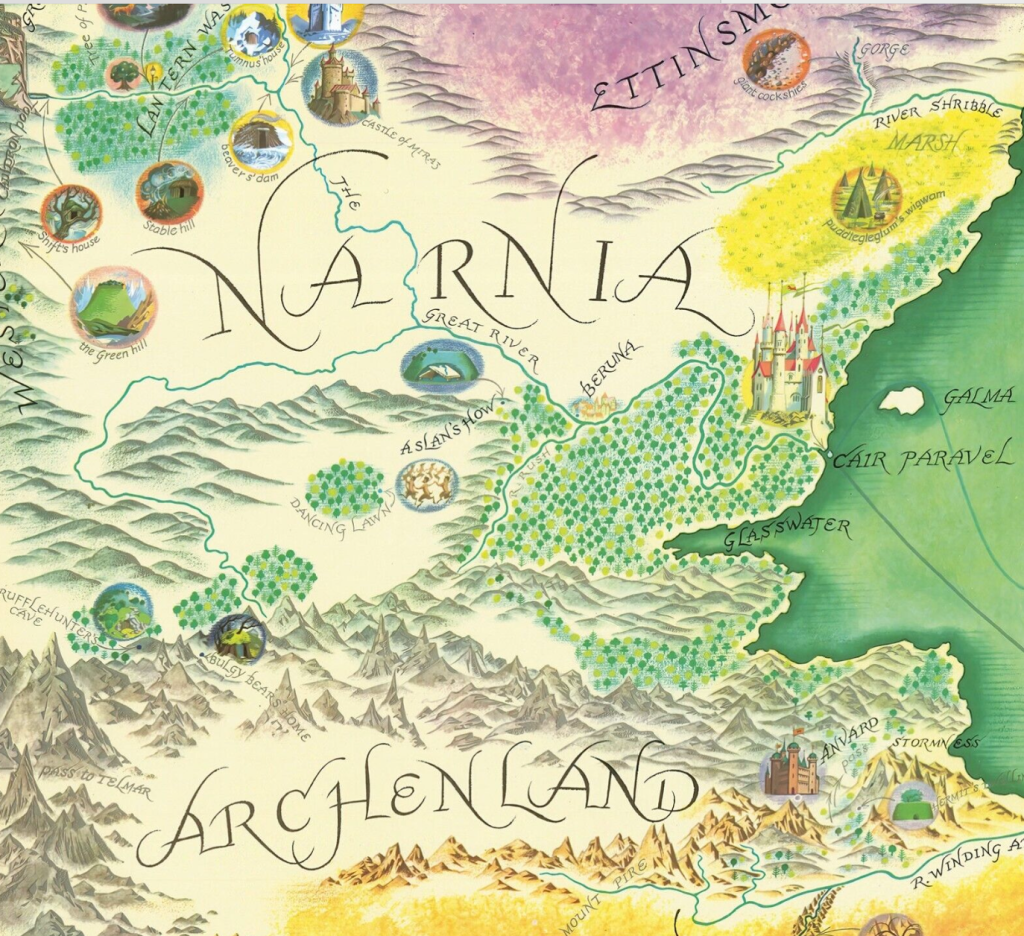

4. As much as the creation of the authors’ themselves, we may under-rate the designer of their maps. The designer of the hugely popular maps not only midwifed the northern shores that Morris evoked in both men’s minds, but gave depth and breadth to the mountainsides and fearsome tumbling seas Morris had evoked to frame the forests crossed or dread mountains clambered across to reach Earthly Paradise “to find a across the sea/A land where we shall gain felicity”–if fain to take “restless road” of the “landless ocean.” Smooth seas, winds, ridgy seas, tumbling seas, and helplessly sailing on a “watery desert” are prominent parts of the Morrissian topography, and the sagas of Iceland and Norway that is insured it, if Oxford lay far from sea, and would play a large role in the voyages of their fantasy worlds–from the sea serpents inviting young viewers’ curiosity in Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the intended end of an imagined trilogy, if seen as the fifth book of the Narnia series– the one written most explicitly as a “spiritual journey” for Lewis, and perhaps the first written with Baynes, who he met after having completed Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe in 1949, but not Dawn Treader when he had invited her to a luncheon party at Magdalen by 1950–“When I had done The Voyage [of the Dawn Treader], I felt quite sure it would be the last. But I found I was wrong.” As a trained illustrator who conscripted to work at the famously conservative Admiralty Office at Bath in wartime from 1942, Baynes would have been relieved to shift from the abstract iconography of sea charts and appalled at innovations as the UTM flattening of land, air and sea.

While Pauline Baynes is considered and trained as an illustrator of books in classical style, her professional experience probably made her quite eager to help both authors to create moralized maps of new worlds–a pleasurable sort of mapping, whose legends often adopted from anonymous medieval maps, and the arts and crafts handbooks emphasizing craft over ornament, as Ruskin and Morris, that would have been a welcome shift from in sounded coastlines of Admiralty Charts, even if she appreciated the strategic importance of delineating avenues of approach as of pressing urgency–from the British coast at Dartmouth to this North American chart from 1944–

British Admiralty Chart, Approaches to Dartmouth (1943)

British Admiralty Chart of North American Coast, from Cape Breton to Delaware Bay, 1944 (1946)

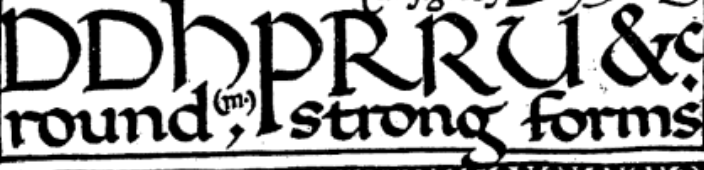

–for the expedience of adjusting writing to th content of the map, intimately associating text and page in a readable surface that tied lettering to principles of design emulating calligraphic precepts following “correct forms of the eleventh century” that recuperated the script lombardic, uncials and half uncials of which Tolkien was so fond, in place of abstract standards of gridded space, preserving the “best pen-forms” as “arch-types” that belied their presence on a printed page as distinctively “pen-made letters” that recuperated the marriage of craft and style in a scriptorium.

Edward Johnston, Writing & Illuminating & Lettering (Lettering, Calligraphy, Typography), 1906, rep. 1939

Tolkien adopted the typeface from such Morrissian model books to suggest the removed time in which he wrote, and indeed the entrance into another world. Did a shared dissatisfaction with the privileging of abstract informative content over a moralized record of travel, leave Baynes, also an eager student of the very same Arts & Crafts tradition, eager to collaborate on illustrating the two fantasy books to which she was so eager, dedicated, if perhaps underusing contributor, in ways that shaped the permanence of their vision? Tolkien had perhaps nervously urged Baynes to avoid imitating Arthur Rackham, who the publisher may have cited as one of the models of her training in decorative arts at the Slade, with Gustave Doré, when she undertook illustrate to his comic verse, Farmer Giles of Ham, a cautiousness that led him to circulate the illustrations to friends, no doubt including Lewis, for advice, finding himself “not well acquainted with pictorial art” without false modesty. If the images were claimed so successful to reduce his own narrative to a commentary, the decorative style that may not have stood her in good stead with Lewis. Tolkien insisted the Norse halls and animal imagery derived from Morris, but Baynes so elegantly channeled qualitative local detail that must have been a liberation from the constrained style of drafting hydrographic charts, and fit Lewis’ demand to find an immersive alternative world to involve child readers, an audience he seems to have found himself with far less confidence than Tolkien to try to address–as well as to return to Oxford.

Did her skill influence Voyage, perhaps the first of his book Lewis wrote knowing Baynes would illustrate? He completed two of what would be seven volumes books quickly, with a rough map–Lewis met Baynes in a year-end luncheon after he invited her expressly to Magdalen College for lunch on December 31 1949, ten days after Tolkien finalized her to illustrate what would be Lord of the Rings, if he was delighted six months earlier at the quality of her illustrations of a mock-epic, and knew her work from publisher George Allen in 1948–just after she published her book, Victoria and the Golden Bird, took its heroine a global voyage spanning continents from Africa to the North Pole, distastefully pedaling or perpetuating rather dated racial stereotypes in its pages for readers, in a quite different style that seemed to have embraced scenic illustration in place of mapping.

Yet the dichotomous sense of a battle between good and evil that Lewis set out to render for children in the volumes of Narnia seemed to concretize a story of human weakness and corruption that did not rely on supernatural aids but a cosmos that one entered through a wardrobe–

–which Byanes was suited to draw. While Lewis saw himself as an heir to Morris, TheOr did Baynes, a fan of Arthur Rackham and Gustave Doré, whose work of illustration was influenced by Morris, not find a common touchstone or model in Morris, that led Tolkien to praise her agency as an illustrator in 1949 for reducing his own text to a commentary on her images? Baynes’ attraction to the fantasists’ work as a comparably lush landscape would echo the release she seems to have found illustrating remote scenes with a specificity of place foreign to the Admiralty charts. The forests and shorelines of the powerful maps of both fantasy books were rendered by Pauline Baynes, whose work for the Admiralty Hydrographic Office would have helped imagine the shores that defined each realm–and one thinks of the strategic role of shore maps of considerable sophistication–and, as much as her illustrations, probably attracted both men to .restoring an enchantment of place and a sene of the expanse of mythic rough seas. The military mapping of nautical approaches that were quite sophisticated, of course, dense with topical information,

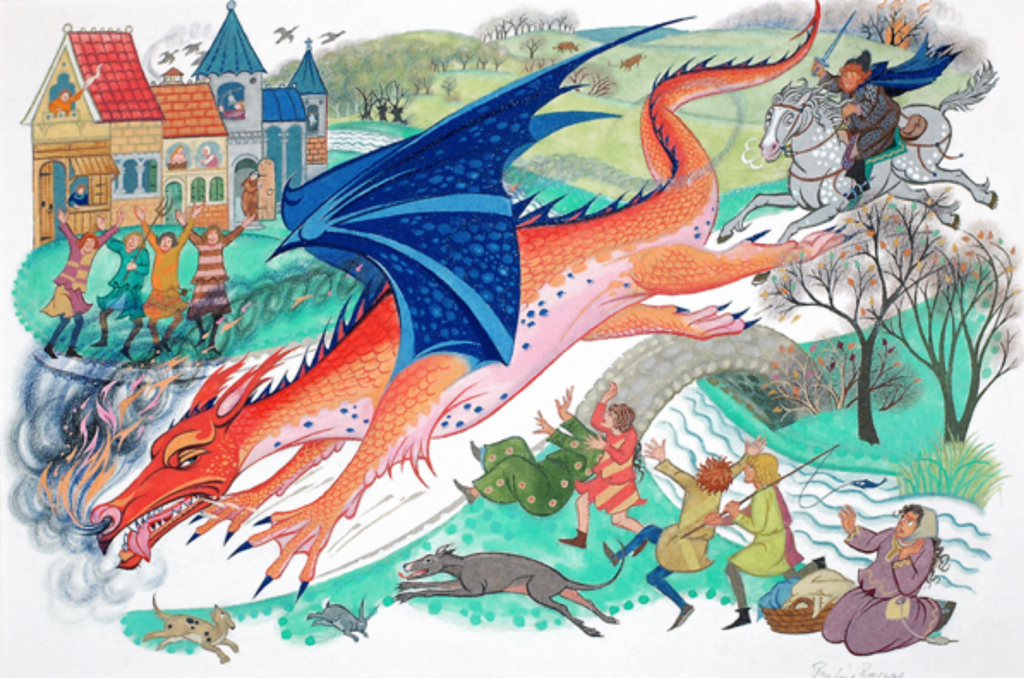

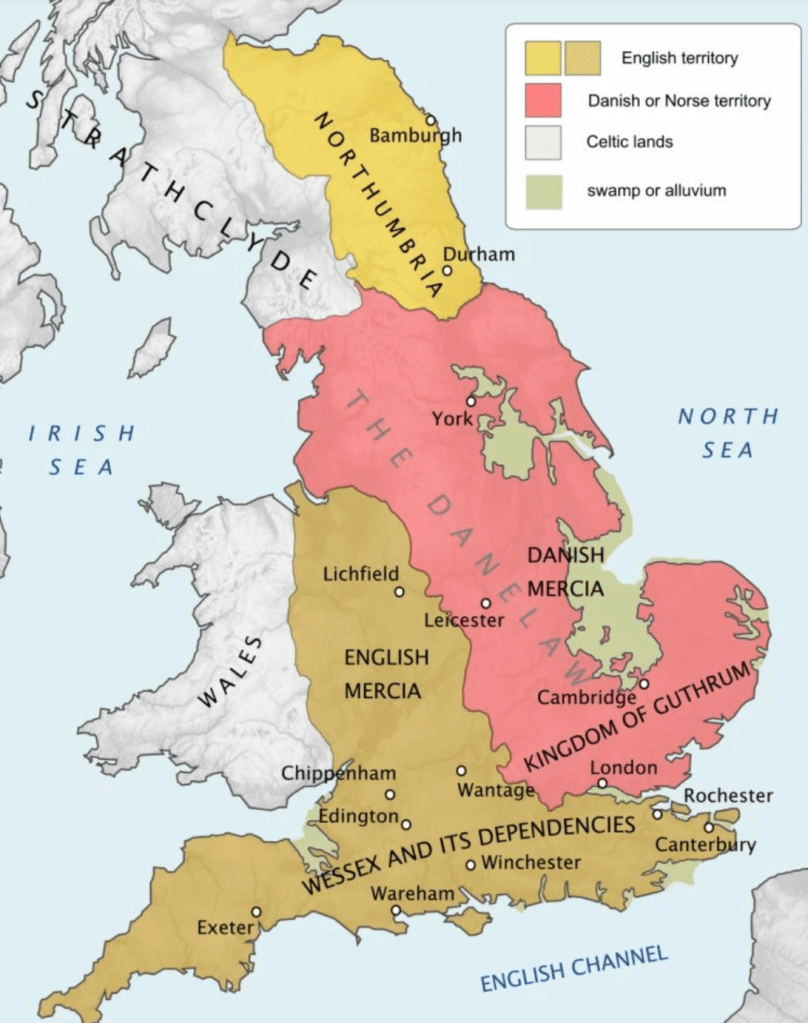

5. If Tolkien’s first book was set in the Midlands where he grew up, or Mercia, and whose dialect he had studied and later used as the dialect of Rohan in the Lord of the Rings, the sense of a “Greater Mercia” that the medievalist had long cultivated in the comedic poem written in wartime was no doubt expressed by Baynes’ sense of style–he praised her images, or embellishments, as credited on the title-page, as being far “more than illustrations, they are a collateral theme” in their Neo-medieval images of storks, owls, pigeons, doves, squirrels, ducks and eagles, birds, in the adventures of “Julii Agricole de Hammo, Domino de Domito . . .Regni Minima Regis et Basilei” or, Tolkien obligingly translated, Farmer Giles, King of the Little Kingdom. Baynes’ images offered entrance-points to the neo-medieval Mercian world in which a man-eating gold-seeking dragon intruded, but Giles single-handedly dispatched from the Middle Kingdom bye his tail-eating sword, Caudimordax. The countryside rendered in glorious pastels was an expanse though which Giles banished the dragon from the land as he chased it across the page–

–mapping the escapade over a river’s stone bridge across which the dragon fled from Arcadian hills.

The protection of the shire of the Middle Kingdom Giles fought off with his trusty Tailbiter sword was a story Tolkien told an audience convened by the former Librarian of Worcester College, Cyril Hackett Wilkinson, who had solicited a “paper ‘on’ fairy stories” after the success of The Hobbit. The occasion provided the occasion for the future Don to revisit the Shire, but even more to invite the service of the future illustrator of the works of Token and C.S. Lewis alike, Pauline Baynes, whose work Tolkien quickly said reduced his own verse to a commentary on its images. Without plans for publication, the philologist created a faux translation evoking the liberatory struggles of reluctant hero to save a seemingly English town from an invading rapacious dragon for its literary club in wartime years.

Baynes generously expanded Tolkien’s comic poem in 1947 with images that mapped Middle Kingdom–a thinly-disguised play on Mercia as a “borderland” or Midlands–that he claimed was not affected by the war; but his romanticization of a longstanding attraction to Mercia, a Kingdom that converted to Christianity that he long identified, and was later absorbed into the Kingdom of England after suffering Viking invasions–vanquished the menacing dragon that had been an existential threat to the Middle Kingdom the suggested an ebullience of the postwar period, buoyed form the circumstances of a devastated countryside by a sense of survival. (If Tolkien presented the nearly 10,000 manuscript pages of Lord of the Rings to publishers in 1949, he had detailed a rich topography of Middle Earth in the immediate post-war period, revisiting the green country that the ridges and forests of the Midlands provided to explore as an animistic, vitally alive other world.)

–illustrated by Baynes quite elegant neo-medieval style.

The sword served as a clever a rebus punning Wilkinson’s surname as the critical point of narrative fulcrum, mythologizing the college Dean whose name echoed the respectable London sword manufacturer who had only renamed “The Wilkinson Sword Company” in 1877 to reflect its new specializations in razors, including electric, as well as nail clippers, pruning shears, and ice skates,–

–the craft origins of the company’s founder in rapiers kept to denote the high quality of its Long Life Hollow Ground blades–the Empire Version of which was made by appointment to George V–

–had a rather royalist mythological hue of evoking a lost past of the English soul. Was there even not an echo of nostalgia or unabashed royalism in the rapier by which a farmer liberated the Middle Kingdom from the greedy Dragon who had eaten the Middle Kingdom’s residents?

Baynes’ inventively adopted marginalia from Medieval Psalters, if her inspirations Arthur Rackham and Gustave Doré, for a proposal that led publishers to put her in contact the Oxford medievalist whose comic novella purported to translate a poem that seemed a Mercian version of Beowulf.

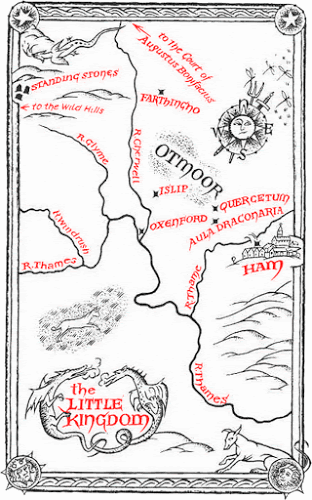

Tolkien long resisted the idea that “the main idea of the story was a war-product” but the story about a Dark Lord he completed provided a welcome relief for Baynes’ recent work for the British Admiralty Service in a pre-Arthurian “Little Kingdom” coyly described as difficult to locate due to a paucity of evidence, but that echoed a fictionalized Thames Valley, in its swamps of Ottmoor–actual swamps that lie just out Oxford, that attract many birdwatchers to what is now a protected Royal Bird Observatory–and Standing Stones of Avebury sarsens–were executed by Baynes as a model for Tolkien’s later maps.

The map suggested, if Lewis only saw Baynes’ colorful images in proof form, but fully grasped the benefits of illustrating a book that proposed travels to alternative possible worlds. Lewis had already nourished designing possible worlds in science fiction, but, more than any of his ambitious earlier novels, sought to craft an escapism clearly born of an ecstatic withdrawal from an Oxford of the air raids of World War II–raids to which Oxford was particularly vulnerable. But it was a world that one could, even in Oxford, or especially there, allow oneself to adopt as a vantage point to view in a different way, exchanging the modernity of Wilkinson’s razors for the swordplay one could imagine in the kingdoms which the individual might opt to affiliate themselves, even if it was a landscape removed in time and perhaps remote to most.

If the “Little Kingdom” was for Tolkien a deeply “Mercian” landscape, perhaps responding to his own anxiety of influence, to the Wessex that Thomas Hardy had mapped from the English Channel to Cornwall (“Off Wessex”) and northward as far as Oxford itself (“Christminster”), first mapped by a young Scottish illustrator, Henry Macbeth-Raeburn (1840-1947), after the old Anglo-Saxon Kingdom. As if to devise a new topography to test his won fantastic stories for new audiences, Tolkien had resurrected an imagined Middle Kingdom for an imagined lost heroic poem whose marshes and rural White Horse Baynes so elegantly mapped as a world apart, more Mercian than Saxon, and more decidedly north–and touched by Viking traces in its tenth century burhs.

If one takes “ecstatic” from the Greek as literally a standing “apart,” Narnia became a place apart, a withdrawal from the bombed-out landscape he wrote, and a hope to offer security to the children he had hosted in Oxfordshire. The very notion of “standing apart” from a wartime world–and standing part in a forested world that derived from “foris,” or outside, demanded to be illustrated and mapped pictorially in all its otherness, in the catechism-like books offering hope to seek the rational grounds for hope in religion that was perhaps itself developed at Oxford in the Oxford movement. The ecstatic otherness of Narnia met a desperate hope for help in a very much darker world, moreover, that may account for much of its survival in the postwar era, and especially, when it donned new covers in Colliers paperbacks, the Vietnam War.

5. Paradoxically, readers may begin the book with little ken of the map, although the map that will open in the course of Narnia has come to define escapism and fantasy worlds in later years, especially in America. But the map that first appeared only in the third volume of the fantasy series is inseparable from the series of seven books, and provide a durable symbol of the imaginary world so many readers wish they might inhabit. And while Lewis was far much less of an inveterate mapper of his alternate world than his colleague and friend J.R.R. Tolkien, who had introduced Lewis to his future illustrator, if he had been reluctant to encourage Lewis’ work on Narnia after reading the first chapters of Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. If he was slow to locate an illustrator for the first volume of the seven-book series that would prove incredibly popular, Lewis was practiced at world-building, perhaps inspired by H.G. Wells and popularizers of science, the allegorical arc of Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) fed readers’ imaginations by a quite majestic fantasy map with spatial concreteness due to the images Baynes added, illustrations now so inseparable, that were not planned before they were drawn. After seeing Baynes’ illustrations for Farmer Giles in “unreduced form,” or before proofs, Tolkien conspiratorially told his illustrator in a Christmas card she would soon be contacted by Lewis to illustrate a work as yet neither illustrated or clearly mapped–and hoped that “two (large) books of mythical legendary ” of his own were in the completion for which “I hope that some illustration or decoration will be part of the programme.“

But the “programme” that came to map fantasy worlds in a formative way for the twentieth century seem to have developed from the encounter with Tolkien’s illustrator, herself a rather wayward cartographer who had specialized in adding quite critical qualitative detail to maritime maps increasingly abstracted from their terrain. The logic of mapping, in short, became a critical counterpart to the theological intent, jousting uneasily with it, perhaps, in many readers’ minds. Did C.S. Lewis ever imagine the intense engagement with which Baynes would elaborate detailed maps of each fantasy work? Baynes in fact only included a map in the third volume of Lewis’ Narnia chronicles, perhaps as she gained some sense of her authoritative contribution to what he intended as purely a trilogy. While Lewis was eager to include a map in the final book of a trilogy–he was a fan of Richard Wagner’s operas, unlike Tolkien, as well as the fantastic landscape of Icelandic saga–Baynes delineated provided the fullest revelation of Narnian topography in the popular series of books. The detailed pictorial canvas became a symbol and almost a surrogate for Lewis’ art.

The role of many unsung women cartographers and map-makers is increasingly reappraised in a field in which few (if any) women appear as agents of modernization or modernity, as if cartography was indeed a separate preserve of male experts, trained in mathematics to construct a male preserve of rigor, exactitude, and hard-edged learning. So compelling has the map been for future readers of the eight-volume series that the pictorial map Baynes only completed in pastels by 1972–after C.S. Lewis’ passing, but as the series won increased audiences both abroad and in the UK, offered a palpable space to inhabit, translating the author’s more nebulous discussion of the portals to the enchanted lands as a topography present to the reader, complete with coasts, a four-color differentiation of regions, a complex hydrography, and forested expanse–

–is almost able to dwarf the theological allegory animating Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe of which Baynes had been by her own admission slow to grasp. But perhaps the intense coloration of the allegorical landscape was an homage to the genius of Lewis’ works and the interests they tapped, if they lie at an interesting angle to the rather unspecific narrative, by offering a palpable sense of a landscape of clearly jagged coasts and Morris-ian mountains,–a distinct terrain of green forests and rich hydrographic rives running to the oceans at Glassware and Cair Paravel, that long fascinated readers, making it an almost surrogate text a trigger to the memories of the imaginary land. The toponymy that unfolded like an illustrated manuscript of medieval origins of its own, proclaiming its expansive artifice as much as the detail of its spatial construction for readers, was a sort of homage to the medieval aesthetic Lewis sought to nourish, if he had limited graphic skill to craft. Indeed, many of the evocative place-names that were included in the Narnia maps but did not appear in the books themselves seem added by Baynes to meet C.S. Lewis’ clear intent for a map that was atmospherically appropriate to describe the voyage of the Dawn Treader–“The Great Eastern Ocean” and “The Bight of Calormen” off the coast of Narnia–a critical contribution for which Baynes, who sold the illustrations in bulk to the author, never received full credit.

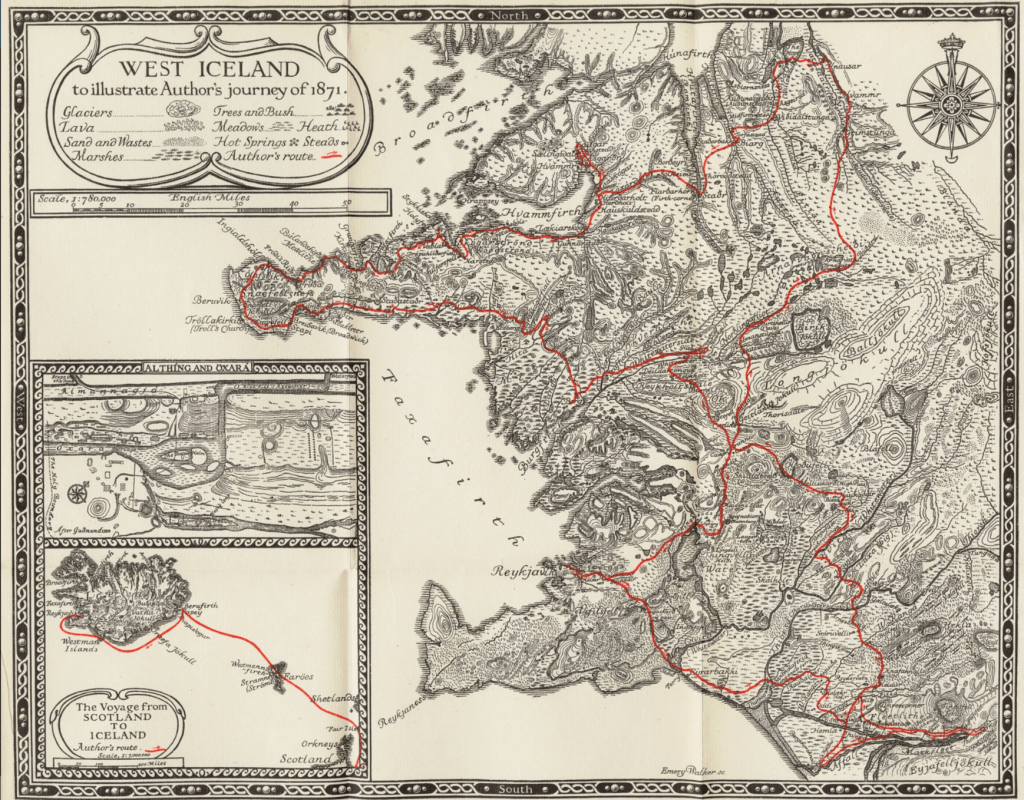

Both medievalists, as Lewis would later note, were “raised on Morris,” both his 1867 Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niglungs, and epic poem Earthly Paradise (1868-70), whose lasting effect on Lewis would led him to distinguish how while “other stories have scenery; his have geography.” Lewis elevated Morris’ genius in constructing f”fresh and spacious” worlds for readers “as tangible, as resonant and three-dimensional as that of Scott and Homer,” whose secret skill was to “tell you the lie of the land, and then you paint the landscape yourselves.” Morris’ Earthly Paradise, a poetic volumes described wanderers in search of a deathless kingdom across memorable landscapes, offered readers “pleasures so inexhaustible that after twenty or even fifty years years of reading they find [his landscapes] worked so deeply into their emotions as to defy analysis;” C. S. Lewis was adamant that “no mountains in literature are as far away or as distant mountains in Morris.” Tolkien had famously bought Volsung with prize money in 1914; Lewis treasured the complete works of Morris that he delighted obtaining in 1930. Morris had himself discovered medieval literature at Exeter College–reading Chaucer and Mallory with eagerness, but the Norse legends in Thope’s Norse Mytho0logy that Burns-Jones shared with him encourage the explorations of the Edda, Grisla Saga, Viga Glums Saga and Norse geography that he sought to recreate in his fiction, mediated in no small part by an Icelander who arrive din Britain form Reykjavik to supervise printing an Icelandic New Testament but became a proselytizer of old Norse who opened a northern new world, translating Viking saga in a library that Morris lovingly emended into models of prose romance.

Both Oxford medievalists aspired to Morris’ skill in reanimating a similar neo-medieval world with mythology and folklore; Tolkien lifted toponyms as “Mirkwood” directly from Morris, as well as the “Dead Marshes,” relying on their evocative power. But to illustrate alternate worlds, both appreciated Pauline Baynes’ acuity integrating the pictorial landscape in a welcoming and engaging iconography of actual topographic detail. Morris was by no means the central origin of this sense of an alternative world–Lewis would enlarge the canon of alternate worlds to many authors who used maps liberally, as writers of what he called romantics, in the sense of courting the ‘marvelous,’ and codes of honor, from Ariosto, who consulted maps, Spencer, Tasso, Mallory, Coleridge, or Mary Shelley–as well as William Morris–Morris provided a rich toponymic repository that Tolkien dipped into rather liberally, in imagining his own forested woods. The geographic expanse of many of the ‘romantic’ authors Lewis so liberally cited often drew on maps–but the place of maps in his own fiction depended on the cartographic abilities of his illustrator (who was also Tolkien’s) to help execute, in ways often belied to a great extent by the focus on their own cartographic creations.

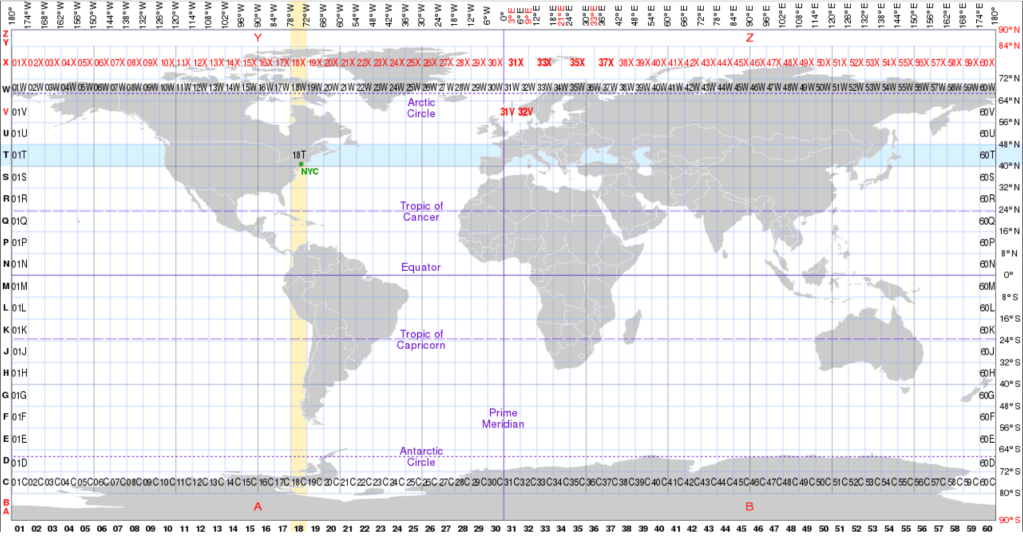

Baynes’ maps demand to be examined as the message and Baynes the messenger of the story of the plot that traced the discovery of the Narnian kingdoms by the Pevensies over eight books that appeared in the immediate postwar years. For her maps, made with intense admiration of Lewis, provided a durable fantasy space that mirror the wars of the twentieth century. The growth of the appeal of Narnia in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s may be tied to the anti-war movement, in part, and the search for values during the Vietnam war, but their global appeal might be more profitably considered as a compelling alternative to the dominance of military mapping of the geodesic maps, that served as a death-knell of sorts to the pictorial map, and how Narnia offered a terrain as a counter-mapping of an alternate world that ran against postwar models of creating a continuity of land, air, and sea that smoothed the world’s surface by a network of gridded lines and coordinates.

In the narrative of post-war mapping, which we associate with the Universal Transverse Mercator, developed by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1940s in response to wartime needs of knitting a world of coordinates to coordinate air, land and sea for a global war, but mirrored in German Wehrmacht’s attempts to construct a similarly uniform geodetic space around a prime meridian, in which radio space trumped lived space and a landscape of physical geographic markers, the work of Pauline Baynes demands attention for its counter-mapping of particular powerful fantasy worlds of two men who were moved to create alternative worlds to how gridded maps, moved to create compellingly vivid alternative worlds–pushing against the smooth planimetric surfaces of grids, and reintegrating the immersive interest in place, path, and route that made way-finding far less mechanical, and less continuous without national divides.

World Map of Nations in Universal Transverse Mercator Grid

Tolkien separated his work on Lord of the Rings from his wartime experiences in public–he began the trilogy years before World War II broke out, he allowed his experience in the Great War of “the Dead Marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme” he encountered as a member of the Lancashire Fusiliers, arriving on the battlefield after the first week, but working behind the front lines in communications. But if his literary descriptions of mountains were informed by Morris’ evocations of unspoiled wilds, Pauline Baynes’ hand on the wildlands that adjoin Narnia’s enchanted shores. For the cartographic skills Baynes gained in wartime offered a distinctly palpable locus of attention that has attracted readers to the classic that has helped root them in many of our minds as a physical places–and a geography we paint ourselves and indeed help to animate. The sense of wild forests and an alternate green world was rich with Renaissance poetics, to be sure, but gained new value as a counter-cartography of enhanced presence that allowed moral orientation absent in the abstraction of gridded space.

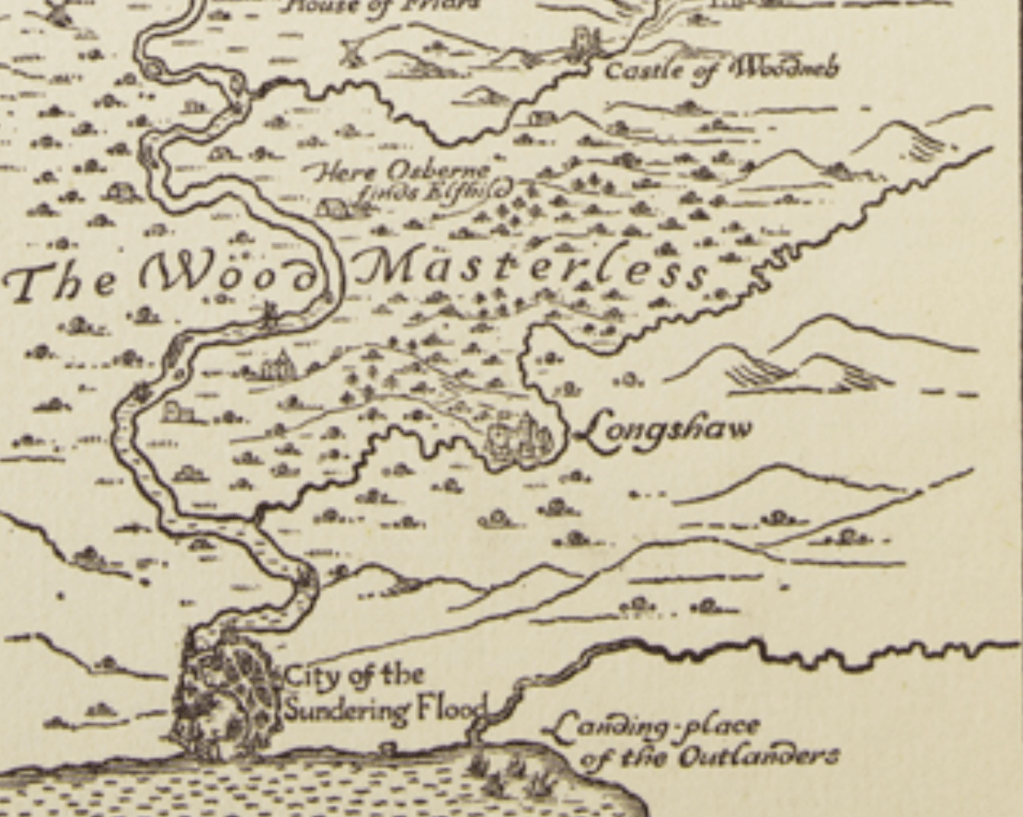

Unlike the remapping of Europe along gridded zones, smoothing national divides in a homogenously measured coordinates, Baynes helped the two major fantasists of possible worlds, J.R.R. Tolkien’s tracing the arc of a voyage “there and back again,” and his friend C.S. Lewis’ forested world of Narnia. C.S. Lewis’ earlier fiction imagined possible worlds to pose a thought question of what it would be like to imagine a world without original sin, a theological thought experiment, but to realize the terrain to encourage readers’ consider the meaning of redemption in the world of Narnia, he sought an illustrator–although he knew little of illustrated books–in hopes to make the world his work appeal to younger audiences, aiming to reanimating nature as Morris. If Morris began his neo-medieval epic in reaction to modern evolutionary thought in the 1860s, Lewis reacted to the mapping of an increasingly smoothened surface of the world. While the maps of both worlds recall the enchanted world Morris helped craft at the Kelmscott Press, in the hydrography and forests of his late Sundering Flood (1897)–the first fantasy map to be printed in a book–inviting readers to visit each of places in a compelling cartographic canvas–formulated a sort of meta-language on the operations of Morris’ poetic fiction, situating readers in the mouth of the river where the group of Wanderers had arrived in their search.

The Sundering Flood, Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press (1897)

The map might one seen as ideal of an enchanted world, as well as an archetype for Tolkien’s and Lewis’ fictions, enchanting readers it invited to visit its forested landscapes as an ideal ‘outdoor’ space, a Paradise analogous to the realm of Narnia, ruled by its four Kings and Queens, the Pevensie children, whose rule inaugurated a Golden Age, offering evidence of an other-earthly paradise. In inviting the viewer to investigate a world that does not exist, the map invites them to investigate a fantasy landscape that it affirms as an actual landscape, using the map’s coded signs as a meta-poetic fiction, like The Earthly Paradise, leaving the industrialized landscape of England, or the new English countryside, to immerse oneself in a dream world, far from modern grime and noise, that he alone could lead us as to a new Jerusalem.

Morris felt the need for mapping his neo-medieval epic as healing remediate what he rued as the ruination of industrialized England. He called the Volsunga Saga “the great Story of the North, which should be to all our race what the Tale of Troy was to the Greeks,” but oriented readers to the landscape Sundering Flood as an even more grandiose form search for earthly paradise across vivid landscapes, a quest trough ancient forests with a magical sword that recalled a native epic. Morris’ northern worlds, became a basis for Tolkien to defend the genre of “fairy stories” as located in the realm of Faerien, as a parallel, but not secondary world; the Highlands of Narnia, dense with mountains and high hills, treeless and desolate health and moors, deep and narrow ravines, and the richly imagined landscape of Narnia, through which the reader moves between wasteland and abundance, seem a fictional landscape on the border of a purely linguistic art.

Morris’ work was rooted in his imagination of the north, but he depended and drew for the mountainous ridges and valleys of his evocation of landscapes in the four volumes of verse of The Earthly Paradise reflected his travel to actual northern landscapes. At a moment of crisis in his life, provoked as his wife and muse, Jane Burden, left their marriage, or seemed to, for his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Morris for the first time toured western Iceland–immediately struck by fissures, grassy peaks, and rivers of the mid-Atlantic island straddling tectonic plates he traveled in the summer of 1871, in the company of the Icelandic scholar Eiríkir Magnusson, who had assisted his translations of Icelandic saga; if Iceland is often claimed to inspire Tolkien’s Middle Earth, his flight from Kelmscott Manor, as his wife had taken up with his guest and friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti, led to immersing himself in the landscapes as an escape, on extensive itineraries in barren wilderness, fjords, active volcanoes and waterfalls of spectacular height–

–where he found a sort of healing bond between man and nature, echoing the unity he sought between God, man and nature that Lewis aspired. The trip to Iceland led Morris to refashion himself after older heroes, visiting interior mountain ranges on pony, “fiery and green sunsets,” and lava-rimmed volcanoes reflected in oral traditions, offering landscapes he mined in later poems and his translation of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs, offering a rich toponymic register for Tolkien–who readily pillaged Morris for place-names and the name of his sorcerer Gandalf. If Lewis celebrated his acquisition of Morris’ complete works by 1930, Tolkien bought his first Morris book in 1914, and imbued himself in Morris’ laying down of harmonious precepts of book design. Was non Narnia, if the production of a common press, Allen & Unwin, and later many paperbacks, a version of Kelmscott for a mass market reading audience of children? To make it work, he needed suitably enchanted and enchanting maps, to be a powerful counter-mapping of the post-war era.

Very eager to read this post—looks delicious! Can’t wait to finish it!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!