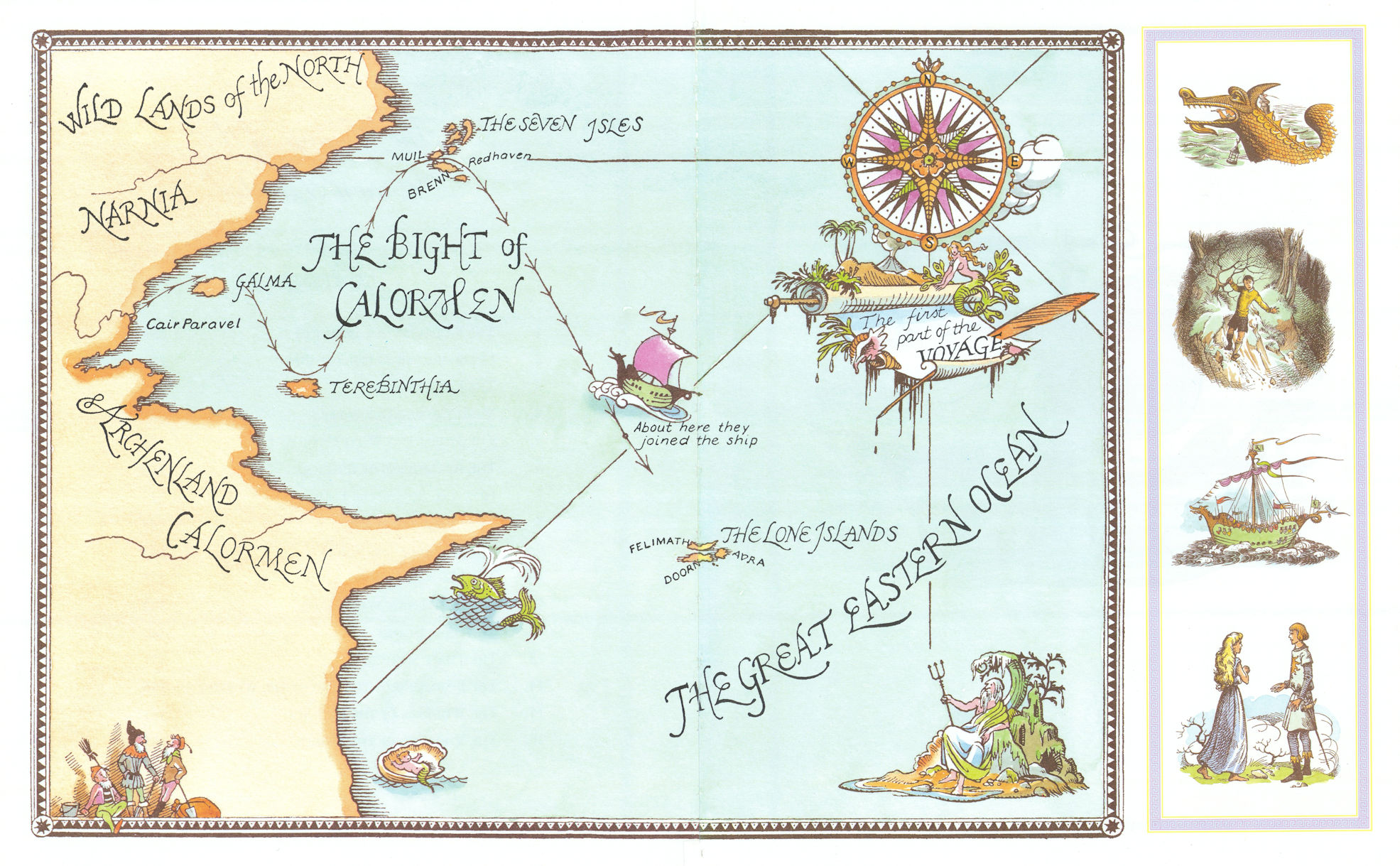

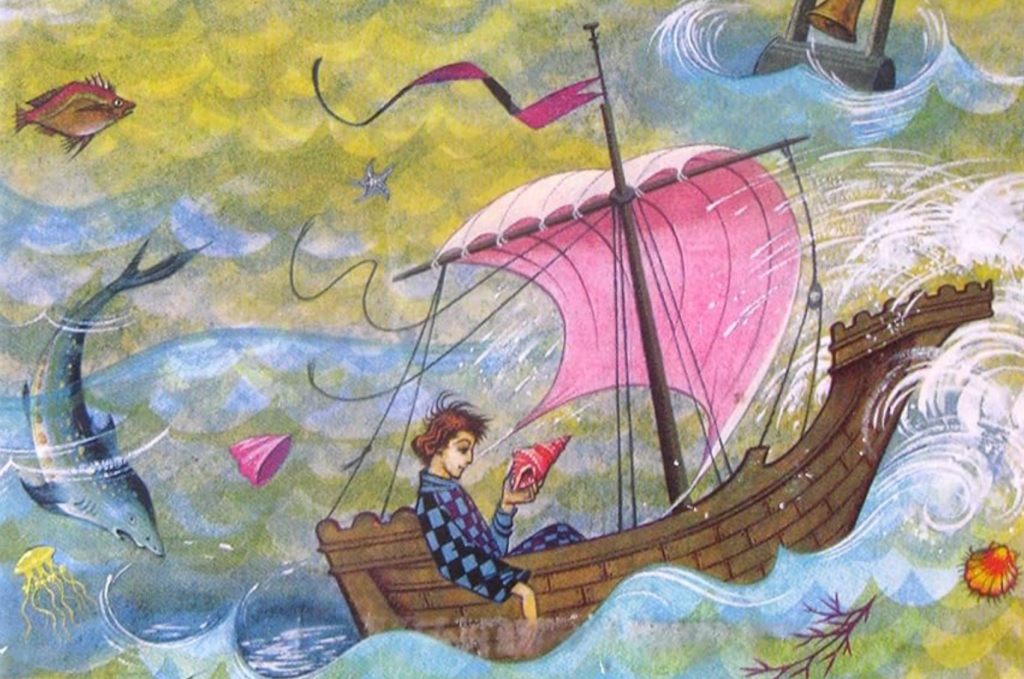

While the map of Narnia only appeared in the third volume of the series–the only one that included a long discussion of shorelines, a periplus that follows at sea the three the Pevensies too young to enlist in the royal navy, on a rescue mission of Seven Lords of Narnia, that concludes on a mysterious shore. If the book leaves the children so overwhelmed by memories of the “wild, briny smell” as the only available evidence that might convince them of the reality of their travels, the map materialized their travels more clearly than Lewis demanded from his earlier books of science fiction might provide–and seems to have been happy to task Baynes in doing exactly that, offering several of the maps she provided as endpapers to the Bles editions of his expanded work. The map appeared in the very volume of the Narnia series where Lewis seems finally to broach or come clean about the hemispheric construction of the enchanted world, Dawn Treader: he situated Narnia within a set of spheres of the sky and the stars, and Aslan’s world, that mirror the medieval image of the cosmos–that “discarded image” whose loss he had come to mourn as if to regret its loss from the mental horizons of a new global culture of postwar Europe that privileged the secular, in the name of science. (Clive Staples was far more familiar with Ptolemy’s astronomical handbook the Almagest, which he delighted to cite, than the more richly illustrated Geography.)

The big “reveal” of the cosmographic situation of Narnia in spheres of air and stars occurs at the final moment of what was the third–again, intended to be final–volume of Narnia Chronicles gave evidence, if one needed it, that Aslan had arrived from heaven to earth–even if the geographic situation of Narnia is less clearly defined than its shorelines. (Reminding us that all cosmographic mapping is also local, the thirty-foot high watery wall of water at the world’s edge the kids and their martial mouse Reepicheep finally encountered in the final scene of Dawn Treader, “a wave endlessly fixed in one place as you see at the edge of a waterfall” behind which a glimpse of Aslan’s country is revealed as the sun rises, lying just beyond the sun, so overwhelming Lucy, Eustace and Edmund to leave them speechless echoes the smaller waterfall under Little Godstow Bridge rushed down a weir beside one of Lewis’ preferred pubs, The Trout, praised for how a “clear stream, as yet unharmed by the pollution of towns”rushed “under the ancient bridge” in 1885–what Peter Laslett, the clergyman’s son whose historical work traced a historical rift between a preindustrial and postindustrial society, called the “world we have lost.” Lewis, more than his friend Tolkien, was shaped by the tractarian aesthetics of the Oxford movement–the indirect treatment of allegory to deploy veiled allusions to Christianity: John Keble impressed his followers in the Oxford movement to cultivate a “habit of looking at things with a view to something beyond their qualities merely sensible,” unlike the seductive fictions of the popular press; Lewis almost shunned the sensible world in his work in favor of wonder, even puzzling many readers who tried to find for mechanic explanations by alluding to the importance of wonder in work bordering on the ecstatic.

Baynes’ cartographic expertise would lend far greater materiality to his possible world. While Lewis’ possible worlds were often intensely cerebral in his earlier work, imagining possible worlds free from sin, he needed Baynes, if he did not recognize it fully or articulate it to her in the course of their collaboration, to provide a more material orientation to the wonderful worlds that he described. C.S. Lewis recognized the power of maps to engage readers’ imaginations in immersive reality, he must have acknowledged Baynes’ ability to draft that world. He effectively depended on Baynes to map the nautical itinerary young readers may struggle to follow. Her map has provided a successful a spatialization of written narrative able to preserve Narnia’s existence as a world apart

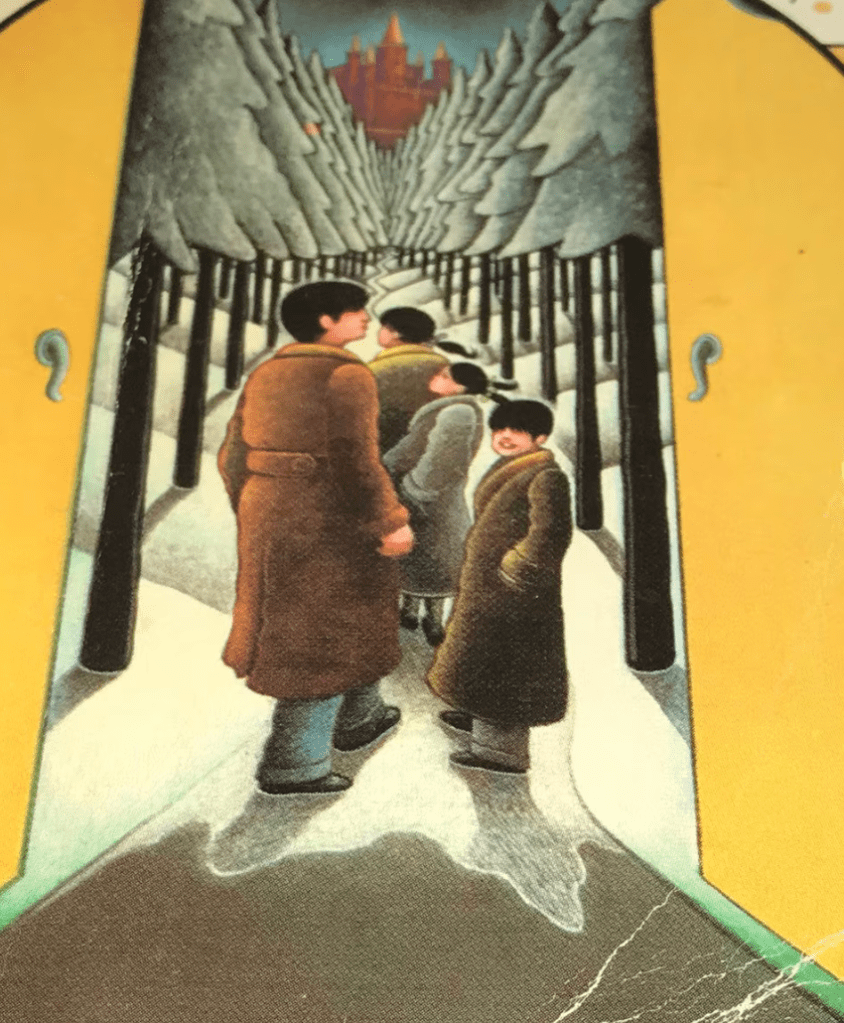

Pauline Baynes, Map of Narnia (1952)

The shorelines Baynes added to the map of the Great Eastern Ocean oriented readers to Lewis’ almost ecstatic description of the “open sea” and into the “Silver Sea” of whiteness shot with gold to the huge stationary foam-crested wave, a full thirty feet high, the shores of Narnia and Archenland lend decisive solidity to the maritime story.

The elegant neo-medieval cosmography of the spheres that divide Narnia from Aslan’s world and the spheres of water and air and of the stars remain mystified recycling of medieval cosmographic topoi, rather than clearly mapped, but the discussion of the voyage of the sea craft where the water changes from saline to sweet as they approach the Silver Sea may have also encouraged Baynes to apply her own drafting skills learned while she made maps during wartime years for the British Admiralty.

8. The set of books that began to appear to acclaim from 1950 as a “story for children” opened up a canvas for an increasingly paved post-war Britain, from an entry point to an old-new forested world blanketed by snow. The only apparently escapist fantasy endured through the 1970s as a compelling invitation to an adult world that children were enticed to expand their minds, as the geographic poetics of the expansive world the Pevensie children were tasked to explore offered a basis to explore the actual world. The Pevensies’ voyage began in a happenstance way, after they entered it through what seems the false back of the wardrobe in a country house in a fictional alternate version of Oxford. But they entered a landscape of possibility their illustrator Pauline Baynes had been tasked with helping him to map.

If the Pevensie children sported mop-tops by the 1970s that made them seem alternate Beatles vintage Yellow Submarine, entering like fantasy land of forest floors blanketed by deep snows, the maps expand the magical entry point to an. actual cosmography, from the third volume, seemingly expand in readers’ minds, opening the onion-like layers of an alternative world that Lewis compressed to the early twentieth century, but holding timeless mythic archetypes that orient a new audience of readers to the world, as the four children enter the Lantern Waste in a thinly disguised parable on their way to discover the thrones that they will occupy in Cair Paravel.

Cover Illustration of Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe, 1970s edition (Signet Paperback)

The crafting of this new world with deep familiarity to the fast-receding Old England crafted by two aging white men in Oxford is an odd paradox in how their conservatism opened new landscapes for readers. C. S. Lewis and his close friend J.R.R. Tolkien had intended to write a new myth for a modern age in their words, but the cartographic apparatus of both works of fantasy has long stood as an emblem of the alternate world they crafted by providing an actually concrete terrain. It is perhaps more than a coincidence that the devout medievalist Tolkien had inspired Lewis, who was himself born into the Anglican Church of Ireland but left the faith as a schoolchild, to rediscover his Christian faith at Oxford university, where he reluctantly, “kicking, struggling, resentful” to his own surprise and chagrin finally “admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.” Was there a degree of providing a parable of the faith for schoolchildren of a tender age, or at least a map to morals, that animated his decision to abandon or delay his efforts at science fiction, inspired by H.G. Wells and recent science, to turn his attention to the alternate world of Narnia?

C.S. Lewis had designed his own moral map in his earlier attempt at a novel, The Pilgrim’s Regress (1930), after Bunyan–and after Nathaniel Hawthorne’s own satire of Bunyan and modernity, whose hero, is forced to abandon the cities of Thrill or Eschropolis and wary of Mr. Enlightenment, as he encounters three pale figures p[osing as guides to modern wisdom–Mr. Sensible; Mr. Neo-Angular; and Mr. Humanist–figures of Idealism, Marxism, or Hegelianism–to learn to seek grace, by better guide, as he travels along a map that mashes up the moral maps as the medieval Mappa Mundi long residing in Hereford’s Cathedral with a mor modern train map; the moral guide C.S. Lewis intended to offer readers conflating modernity and the route modern pilgrims must chose within emulating Bunyan’s allegorical structure, as Hawthorne’s first-person account of his voyage to the Celestial City with the railroad whose conductor Mr. Smooth-it-away in The Celestial Railroad (1843). ”Claptrap,” “Suberbia,” and “Sodom” were all places to avoid, if one hewed to the moral course, seeking Wisdom and Sensible, and the Broad; Zeitgeist, Aesthetics, Hegel, Theosophy and Dialectics were Shires to avoid if one had any hope to reach Wisdom, in the allegory map.

For Lewis, the project was deeply tied to the “discarded image” of a past world, more dependent on texts, of the long Middle Ages, which he wanted to bridge into the present. While the catechistic structure was condensed in the Narnia series, the far more narratively jerky conceit of a visions of an alternate dreamscape of a refugee from the land of Puritania who encounters Enlightenment figures as Mr. Sensible, who proclaims the benefits of scientific reason, and the flaws of religion, and his wayward son, Sigismondo, who argues for the dominancy of wish-fulfillment in our lives, that he encounters after entering the woods in hopes to arrive at a far-off island he has glimpsed through a wall, offer an occasion of meditating on the existence of faith and religion.

As Lewis’ series sketched a cosmic unity, it grew to a full seven volumes, revealing a cosmos that invited readers to realize the greener region he invited child readers to inhabit, hoping–if without giving it much practical consideration–Baynes’ own graphic stylus might offer access and enrich.

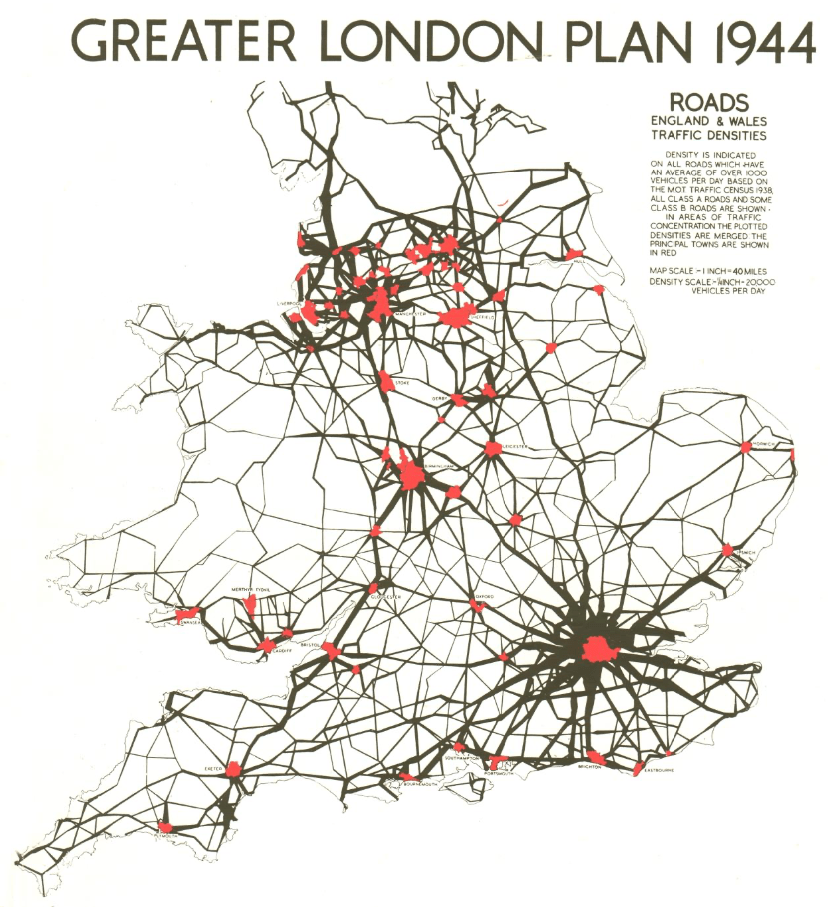

The “restless road of the ocean” was an alternative to the well-mapped street network that had redefined much of southern England, indeed, as an extension of London, and a premonition of future networks of travel, imagining the nation–even in wartime–as in terms of the traffic flows on paved roads that all but erased the forests of the past., that led so many to want to look back to the lost landscape of royal forests in an England whose topography was rapidly being relegated to a remote if not fictional past.

9. But if Oxford might seem removed form the remapping of England, and of the world, the recent expansion of English roads was never far from the consciousness of the authors of both books.

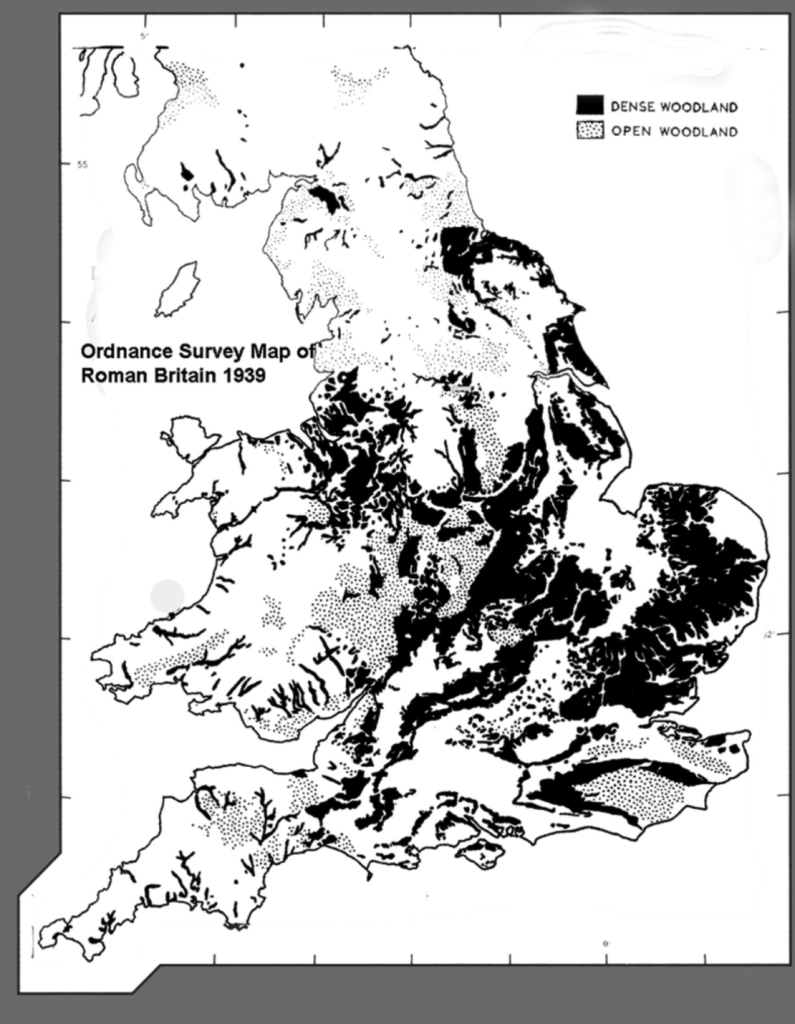

The engineering of the new Britain was, to be sure, not already calling attention to the environmental history of the the loss of those older moorland landscapes transformed by industrialization, afforestation and agrarian changes in land management that have led historians as I.G. Simmons to become increasingly conscious of the lost landscapes of the past, or others to bemoan the haunted nature of the increasingly denatured landscape of the present, where royal forests might be best imaged in the wooded areas in the 1939 OS maps of England–which presented a radical different image of the nation, and indeed a different image of locating and accessing its classical past.

Densely Forested Woodlands and Open Woodland in OS Map of Roman Britain (1939)

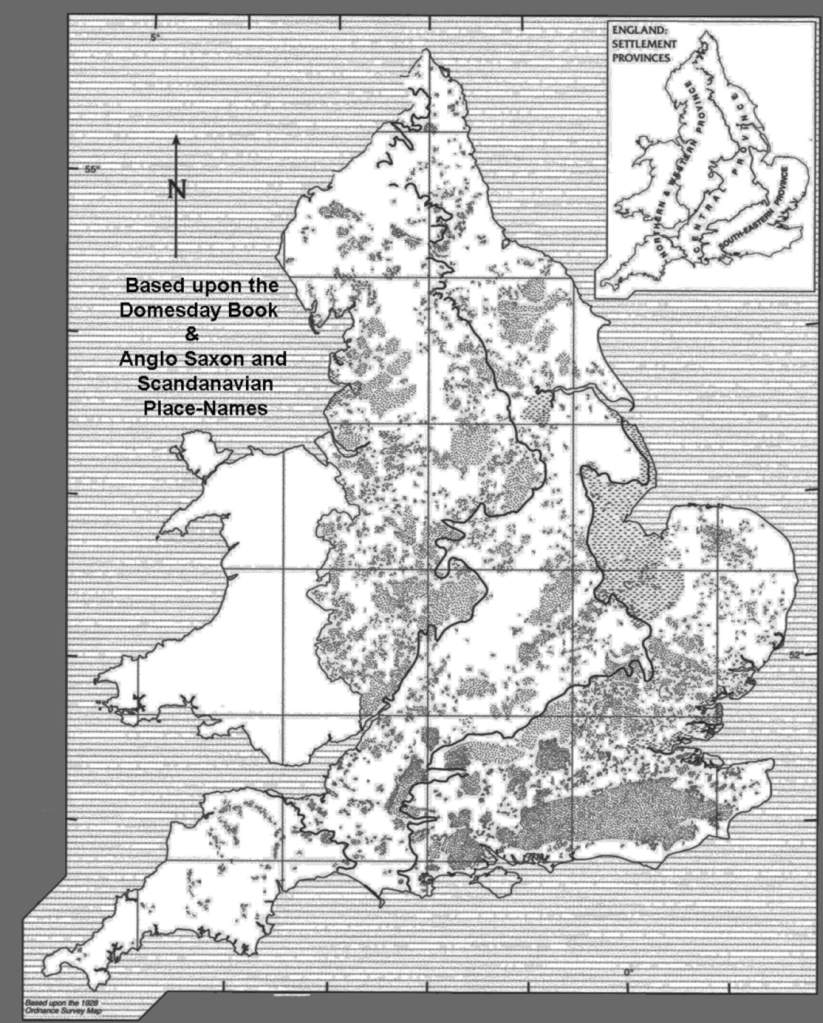

Given we are discussing Tolkien, the OS maps offered a very different orientation to the forested lands in the verbal maps of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian verse–

Woodlands of England Based on Place-Names of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian Origin/

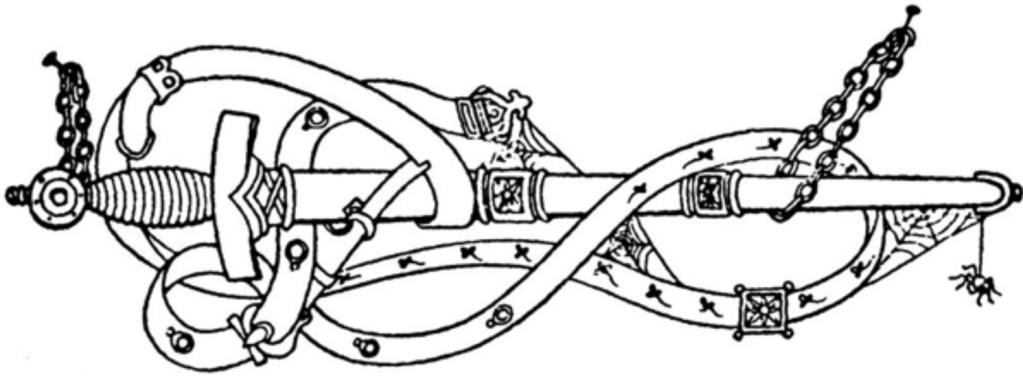

Were not the role of these swords and military arms of medieval times a search for more virtuous instruments of struggle, guided by faith, as much as Enlightened ends of government? Without reaching for any added metaphorical significance, either Freudian phallic symbol that was a symptom of repressed desire–if sometimes a sword was merely a sword, it was elevated to a symbol of “compromise formation” whose associations might well derive from the Nibelung Saga–or Blakean ecstatic inspiration (“Give me my sword of shining gold/give me my chariot of fire“) of renewing a sacred realm. For the sword Baynes illustrated as wrapped in neo-medieval girdle entered a land of magical enchantment, waiting to be taken up as a instrument of valiance from the chains on which it was suspended to liberate the Middle Kingdom. This is not the Wagnerian sword, for example, with which Sigurd sleeps so that he keep distance from Brunhilda, or a talismanic charm against temptation, that compensatorily stood in for a phallus, but for a lost world. Echoing the sword of the Christ Church War Memorial Garden, to those who died in the First World War, below a quotation from Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, the gilded sword of Farmer Giles recalled the virtues of the sword in an age of guns.

There was considerable luck for both in finding as their common illustrator the quite talented Baynes, a practiced cartographer by trade who had worked on hydrographic maps and charts at a time the Adrmy increasingly depended on cartographic accuracy and precision, to illustrate their works in ways that are difficult to separate from their texts. It helped not only that cartographic standards were changing from a pictorial to a geodetic surface by mid-century, but that Baynes had gained cartographic training to design map that met a clear cartographic commission to defend territorial waters, and stage cross-border attacks, the commission to create a newly vibrant cartographic canvas must have seemed a welcome application of the proficiency she developed, with other women who retrained at the Admiralty Office for the war effort. Few technical drawers had parallel careers illustrating children’s books, or were as committed to enchanting possibilities of inviting reading increasingly associated by the 1950s by maps. The outsized dominance text had enjoyed in medieval charts and maps–the legends, toponymy, and drawn landscapes marginalized or absent in modern military maps. It’s no secret that the anti-modernism that we associate with Tolkien and the Inklings, who disdained the imagery of T.S. Eliot, the sex of D.H. Lawrence, or found the language of Joyce frivolous steam, without purpose or clear moral intent, was also anti-modern in its rejection of modern mapping tools, but the scale of mapping adventure and quest in both books were rooted in forms of mapping, as much as of writing, politics, or Christianity, as much as a forms of writing rooted in the rejection of nations for Christian values.

If Lewis was not entirely pleased with the illustrations that his collaborator on the series, Pauline Baynes, made for the series, the maps that she added have survived in a curious afterlife of the book, offering a basis to investigate the maps’ enduring power as a reminder of the fictional land of Narnia and relationship between cartography and art. If Lewis’ reading of The Hobbit led him to remark he was not so much “making it up but merely describing the same world into which all three of us have the entry,”–despite expressing reservations in 1933 about “whether it will succeed with modern children,” the illustrator that C.S. Lewis was so desperate to seek for Narnia had led him to ask bookstore clerks rather cluelessly if they would have any recommendations on a person to illustrate his work. While he had his publisher ask the illustrator of one of Tolkien’s earlier works, in the end, for his own attempt at the “fairy tale we all sort to write (or read) in 1916,” or after World War I–a grim time needing enchantment. Long before Tolkien had tried to imagine the heroic roles children might adopt of comradely and loyalty to one another, he praised the precocious virtues of Beowulf 6 in 191as, notwithstanding its ivory horns, named swords, and beards, modern, and “tried to imagine myself an old Saxon thane sitting in my hall of a winter’s night, with wolves & storm outside and the old fellow singing his story,” immersing himself indulgently in the “different world” of the Anglo-Saxon prose romance he felt closely tied to the Christian world,–writing nostalgically of he “horror of the old barbarous days when half of the land was all forests and you thought that’s demon might come to your house any night & carry you off.”

When Lewis wrote to Tolkien of their mutual ties to a need for enchantment by 1933, excited by the existential drama of the old epic that would both challenge and enrich the idea of a Christian book. When he imagined the need for such a fairy tale back in 1933, after the grim postwar years but long before he had even set pen to paper about Narnia or the later Blitz. When seeking illustrations for a work he hoped would interest a reading market he had little idea of how to address or cultivate, it was rather karmic he located an illustrator whose proficiency in mapping and taste for fashioning her own versions of a medieval manuscript map provided a welcome inversion of the global maps that state mapping agencies had introduced in World War II on geodetic grids. Baynes’ maps have long been noted for their innovative use of coastlines, but also suggested new shores on which the imaginations of readers would land, that echoed less out of sympathy than shared or aligned mutual aesthetic tastes for a text in which readers might immerse themselves. Indeed, if the suit that Demetrious Polychron brought to contest the originality of his fanfiction, War of the Rings, despite his claims it was “pitch-perfect sequel” was ruled as an infringement of copyright by being set in Middle Earth–a claim that the Tolkien Estate has held from at least 2007, several years after Peter Jackson finished the sequence of three films set in Middle Earth and ten years before Polychron gifted a wrapped edition of his sequel to Tolkien’s grandson and executor, Simon–ordering Polychron, who had sought to “stick as close to canon as I could,” destroy both physical and digital editions of his seven-volume homage, Lord of the Kings, for duplication of the settings and use of Middle Earth, some twenty years before they enter the public domain.

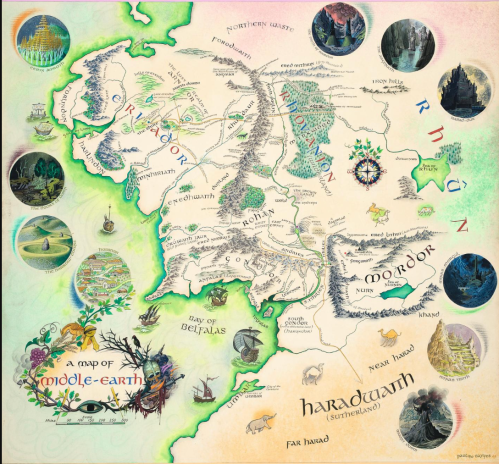

Those glowing coastlines of Middle Earth had provided a concrete purchase on the pastures and lush grasslands of Rohan, and the coasts of Eriador, between the Blue Mountains and Misty Mountains to the East–

Pauline Baynes, Middle Earth (1969-70)

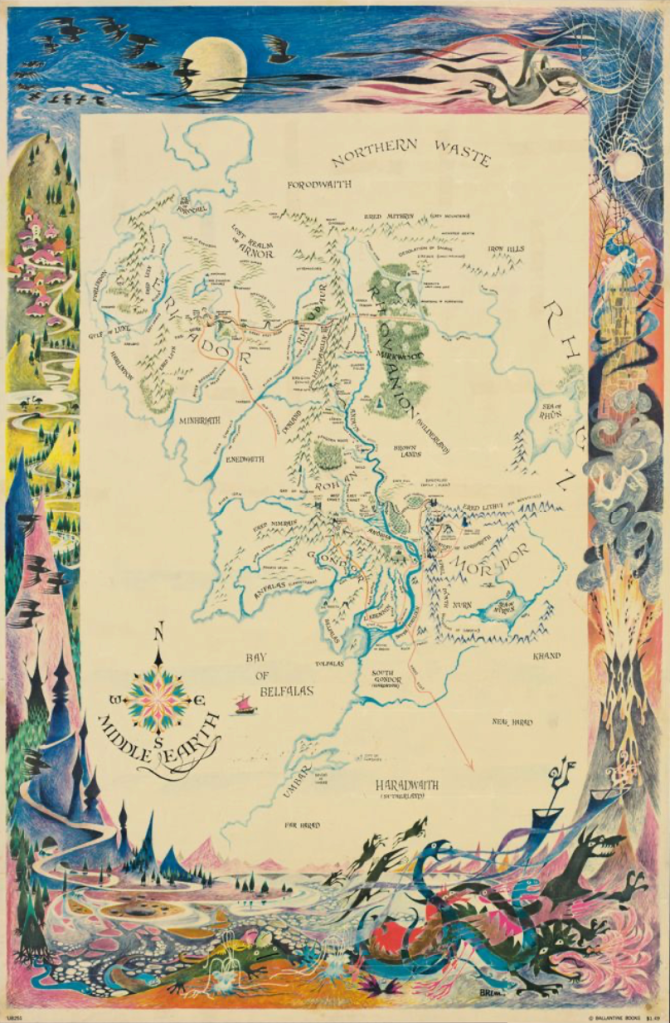

–that the topography was fixed in the. minds of fans, and in most posters of readers of Middle Earth. Middle Earth’s maps were not cited specifically as lying under copyright–the elegant interactive geospatial maps of Middle Earth are widely available from the LOTR project, keyed to Tolkien’s original plot, is an invitation to fan fiction–Baynes was the only artist Tolkien collaborated with on a map, enriching the toponymy and riverine course on the elegant map Baynes painted developed from 1969, which Tolkien praised as a “masterpiece.” One might, indeed, compare them to the maps drawn for the American Ballantine edition in 1969, otherwise popular to readers, of the American illustrator Barbara Remington, to Tolkien’s surprise, One might, indeed, compare them to the maps drawn for the American Ballantine edition in 1969, otherwise popular to readers, of the American illustrator Barbara Remington, if popular among his readers, and quite evocative of mood–and was the map by which I first navigated Middle Earth when I read the series.

Middle Earth by Barbara Remington (Ballantine Books), 1969/Osher Map Library

The colorful map that invites viewers to inhabit a distinct space of Middle Earth, colorful if muted shading of green shorelines seems a particularly cunning piece of Baynes’ cartographic invention, as the ships that lie off the shores of the Bay of Befalls, is not only stunning. It was the culmination of collaborating in the immediate postwar years 1948-9, when Tolkien wrote Baynes to “prevail on you to glance at” the manuscript for The Hobbit finally being typed–and continued to the commissioning of a new map for The Hobbit in late 1969 of Bilbo’s journey, “There and Back Again,” of which Tolkien was quite pleased. (He later retained her for his poemsTom Bombadill, that echoed the Tolkien conceit of translations of a lost chronicle from Middle Earth, the Red Book whose diction and style resembled Beowulf–some of whose names won him praise from none other than W.H. Auden, Oxford professor of poetry, which he confessed “really made me wag my tail” indeed.

Pauline Baynes, Tom Bombadill (1962)

Cartographic creation is separated from the literary work of both authors; this post argues that the cartographic context in which both books were written wa not only collaborative with mapping practices, but can be best understood in relation to contemporary cartographic contexts rather than as fantasy worlds. Both worlds were mapped at a conjecture of cartographic practices in which grids increasingly grew separate from territory, mapping reader’s attention in these fantasy landscapes may be quite difficult to separate from the changes in contemporary cartographic practices; the invention of the fantastic worlds Lewis and Tolkien so carefully fashioned is difficult to separate from the increasing absence of landscapes from maps.

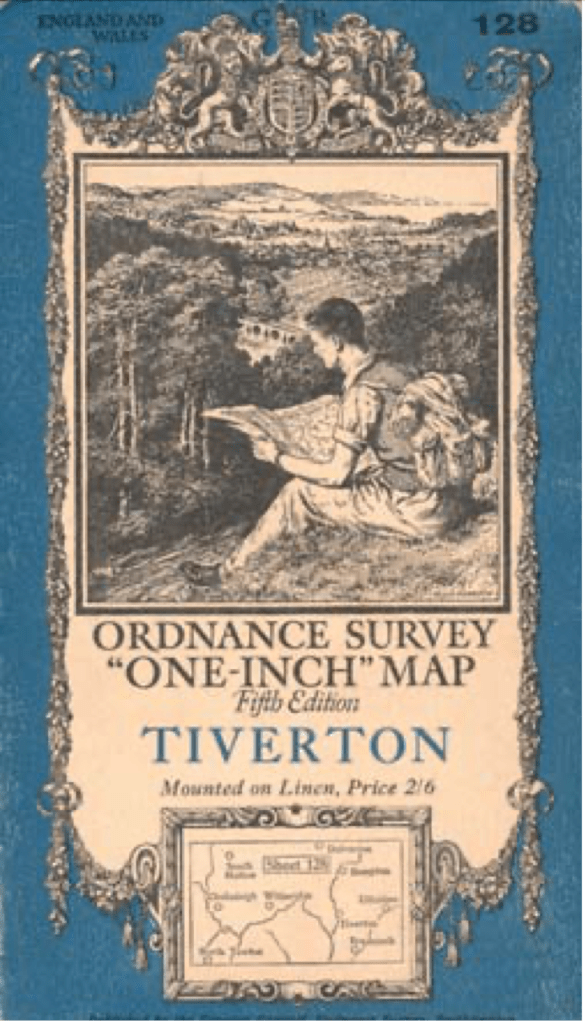

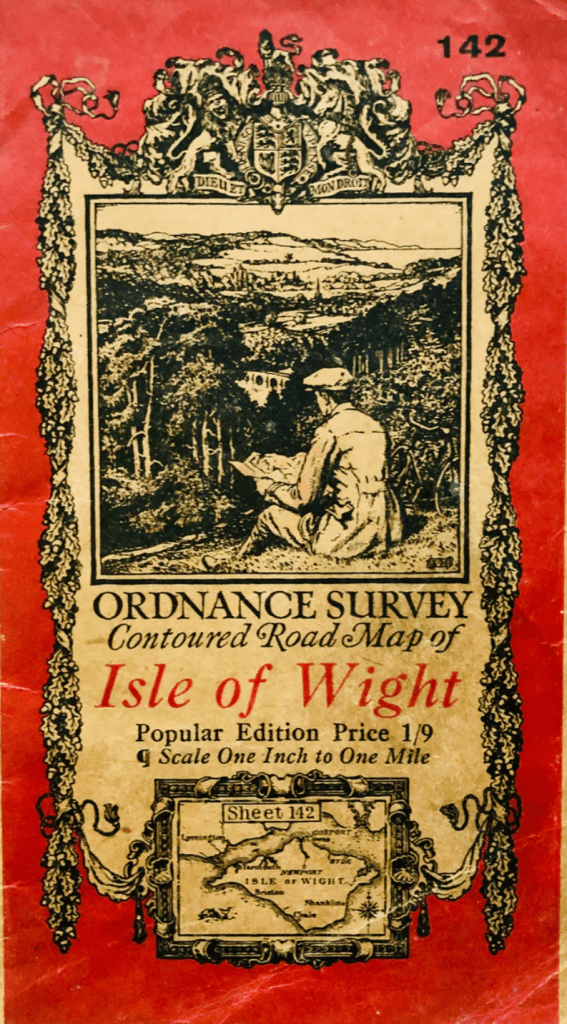

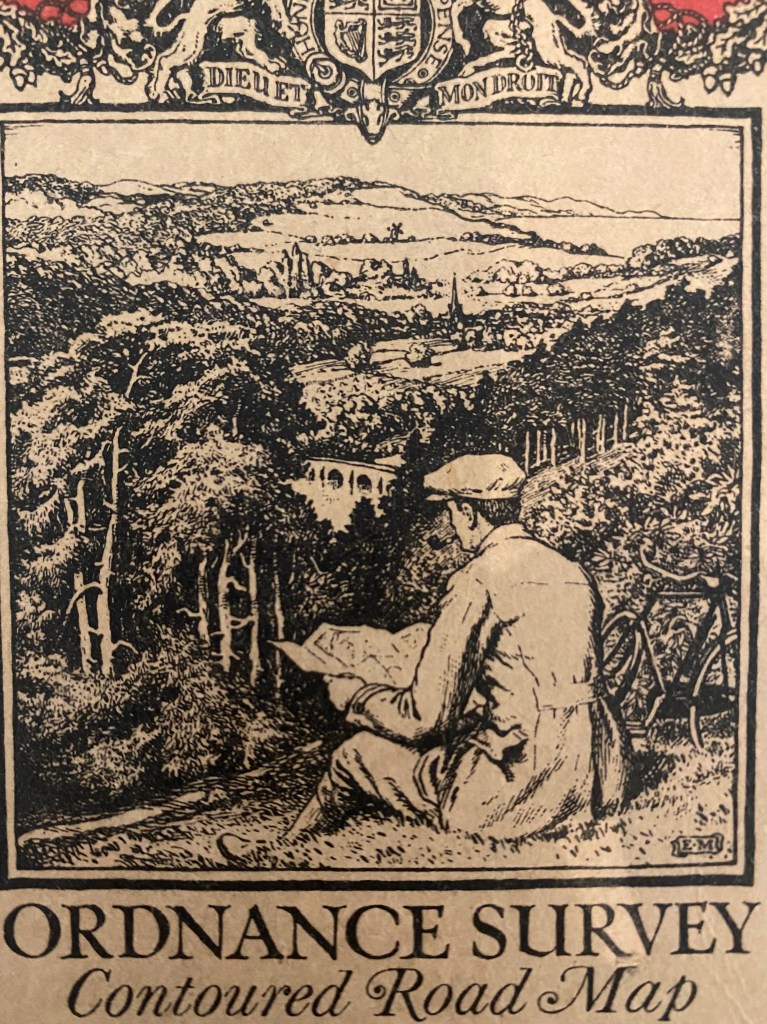

10. Both Tolkien and Lewis, on a more immediate person level, wrote from an age of the remapping of English roads, and the loss of the world of the popular one-inch one-mile popular Ordnance Survey guides destined for civilian audiences after the war, in guides of hiking or outdoors life. Did they not aspire to create a green alternate possible world they allowed readers to access once again? They uncovered hidden paths and roadways of a fast-changing English countryside–even as it was transformed to a motorists’ space foreign to “one-inch” maps for travel and tourism.

Indeed, the dominance of the contoured rad maps as providing the “right to roam” that contemporary popular maps promised to navigate, cycle, or drive around the bucolic words of the English countryside, in a new post-war popularity of the OS maps of military origin provided a way to orient oneself to the landscapes of England–and generalize royal privileges of lion and unicorn to a readership of rural explorers equipped with these navigational tools of road maps–

–that suggested a new purchase on the countryside. At the same time as aerial photography of the Oxfordshire area was exposing a lost landscape of burrows, crop circles, and revealed by Simmons Aerofilms, of a lost landscape of Historic England, after World War I, and producing by 1929 over 5,000 photos a year of aerial imagery, before merging with photographic interpreters of the Air Ministry in 1940, during wartime, as an intelligence unit, the ancient landscapes they revealed of neolithic land structures seemed to be receding from the map. Indeed, the intentional medievalism of the maps of Tolkien’s and Lewis’ fantasy books, as much as depending on a Mortician ideal of craft for their cartographic power, seem dependent on a unique sort of counter-cartography, rooted in pleasure, perhaps, but also on the normalization and recuperation of a lost landscape that seemed itself to be vanishing in times of war with the dominance of the abstract surfaces of geodetic maps.

Very eager to read this post—looks delicious! Can’t wait to finish it!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!