11. Both Lewis and Tolkien would have had inklings of the scale of this transformation of public lands. They recognized one another on shared walks along the Thames Valley besides kingfishers having grown up in the worlds depicted by William Morris–perhaps their ideal type of an illustrator–adorned with curving vegetation and great vines. But if the aesthetic vision led them in different directions, the ways that Baynes came to approximate a Morris-ian aesthetic were surprising, but not difficult to grasp given the broad influence of Morris’ work on illustrators and craft–and the importance he derived from northern myths . The detailed fantasy maps Baynes compiled were mportant precursors for board games, but their close tie to the production of maps drafted on uniform grids in wartime is rarely explored. Baynes’ wartime career is under-appreciated not only in cartographic drafting but in the eagerness to provide–which she shared with Tolkien and Lewis–a counter-geography to geolocated maps of England’s coasts.

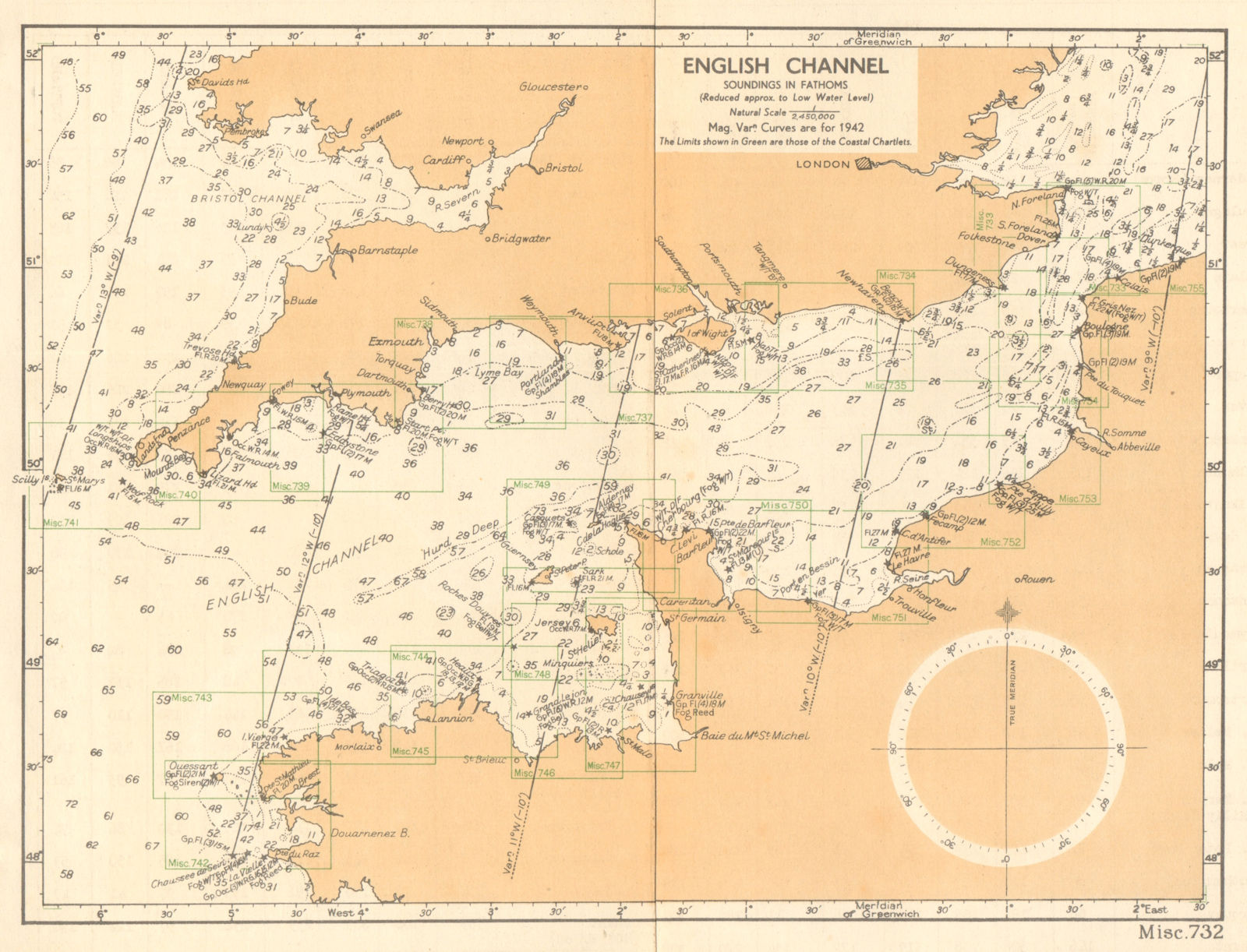

English Channel.from The English Channel Handbook fathoms to scale 1/2,450,000/The British Admiralty; Corrected 15 April 1943

Baynes’ work for Lewis was informed by her years at the Admiralty. Her cartographic skills made her not only a quite skilled drafter of maps for both Tolkien’s and Lewis’ epics, but attracted to a new cartographic idiom. Her clear line mirrored their shared fascination with vital sagas, and morality, a deep commitment to creating a moral vision of a future in a world seemed to risk the absence of morals–or of wonder, The woman whose maps met this desire was able to piqued and sustained that wonder so intensely that they gained an afterlife in college dormitories and apartments in future decades. Her maps conjured green worlds not only of the Malverns, with which both authors, as Morris himself, were particularly familiar–but realize an anti-modern refuge readers inhabited–approximating the “fine solitary moments” in a mystical wood inhabited by living sympathetic animals–through a subtle cartographic response to the sort of mapping tools that Baynes was eager to revisit and refashion in surprisingly durable terms.

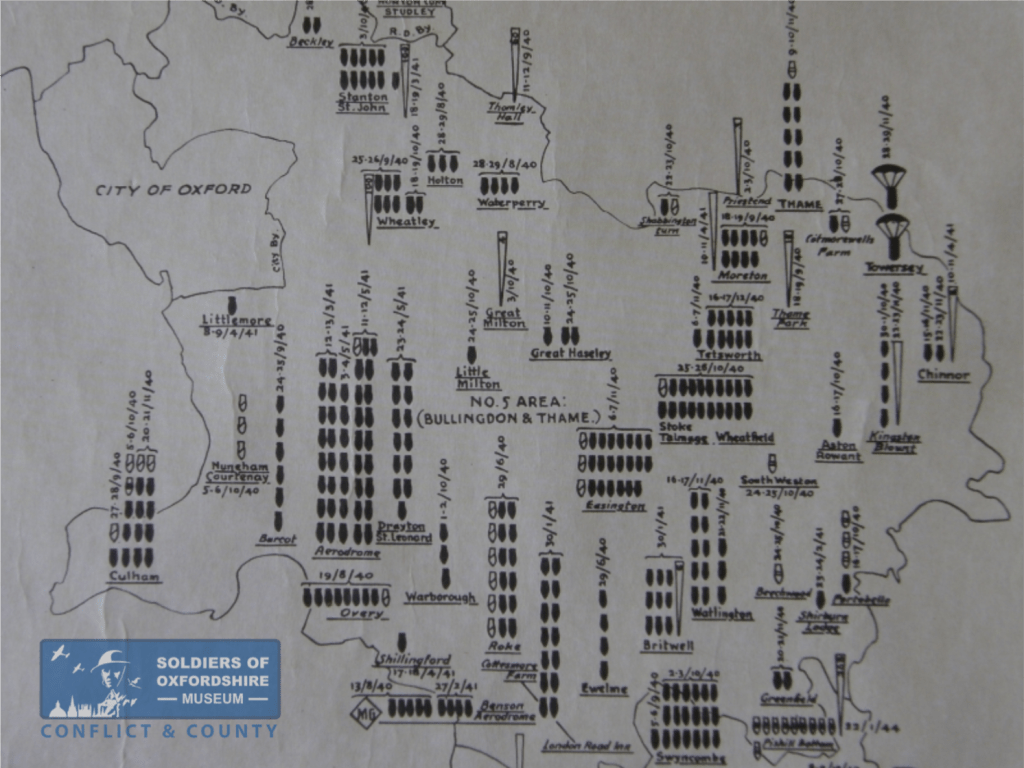

We see the creation of Narnia or Middle Earth as isolated creations of men of genius, cutting against the grain of modernity, perhaps after Lewis’ own figures of magicians who so resemble isolated eccentric professors possessing magical rings, with fantastic powers. Lewis and Tolkien may be better read in parallel the rise of a mapping revolution of state-mapping agencies, however, from the Army Map Service in the United States and Serial Map Service and British Admiralty’s Operational Intelligence Centre–and the new premium on cartographic intelligence during wars. The agencies that produced a range of official charts of global space, often created by women mappers by aerial photographs, charting strategic locations of churches, docks, beaches, schools, roads, contours, and bodies of water, if predating satellite maps, created spatialities across national enemy lines, but provide a context for basis for making and mapping far friendlier fantasy worlds.

Were their own mapping of worlds not paralleling the worlds that illustrated to provide fantastic worlds to escape? While we often treat Lewis and Token as if they wrote as isolated geniuses, visiting the pubs they frequented as sites of pilgrimage or shared destinations where their worlds were first fashioned, we might well benefit from situating their work each within the rise of wartime mapping agencies. For each ewer working to make worlds not only in reaction but as moral maps able not to re-enchant a war-torn world but to provide a more durable and needed moral map to allow us to map a new relation to the world. If Lewis was particularly fond of shocking audience by urging the salutary modesty of the medieval text of the ancient astronomer Ptolemy arguing ‘the earth, in relation to the distance of the fixed stars, has no appreciable size and must be treated as a mathematical point!’ Opening up of a sense of awe in space, even when recognizing the threat of its inhabitation by the awesome presence of evil, was a necessary moral map.

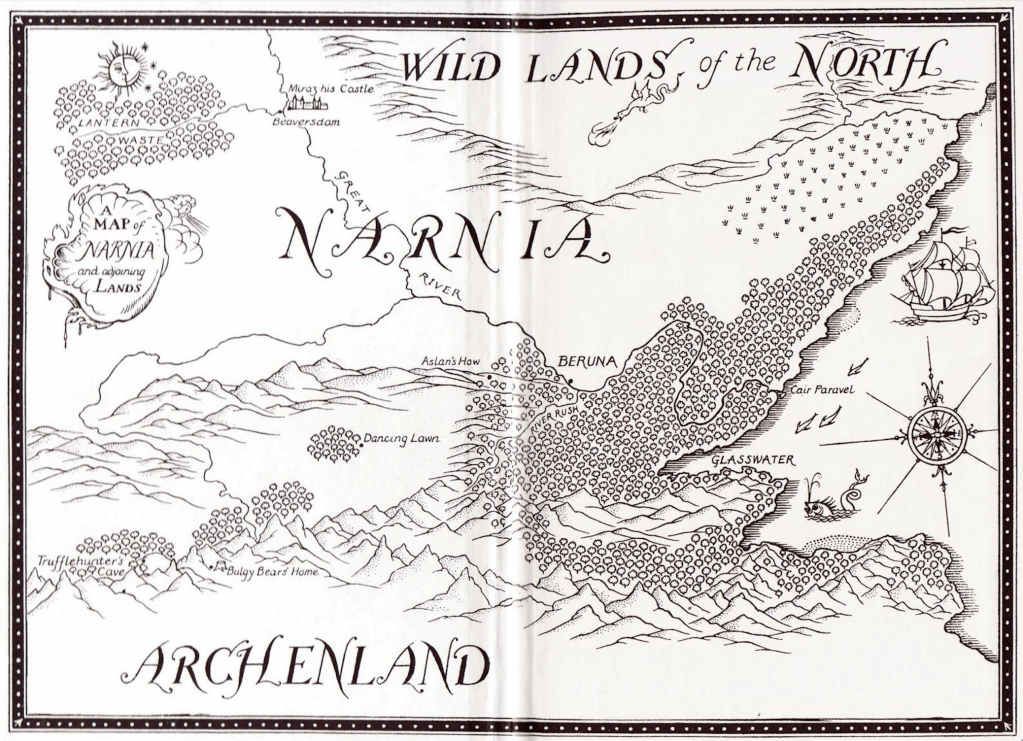

As one moves from one small wood in that Kingdom to a new global map combined a growing sense of a map by which a child forms mapping concepts to orient themselves to the world, a crucial cognitive skill for Jean Piaget, and the unfolding of a parallel existence of a safe and welcoming map to take secure refuge–a danger lurks, to be sure, in the White Witch, but in as a palpably secure safe space. Maps later included in the Narnia series become inseparable additions to later editions to plot an unfolding of dramatic action in the postwar period–a sequence readers feel compelled to reorder in a chronological timeline to better orient themselves to their insights of the history of Narnia and indeed the mechanics of how Lewis’ alternate world-making occurs, which if it opens from the discovery of Narnia, meeting the faun holding the umbrella who leads Lucy Pevensie into his cave for tea, revealing an alternate world of good and evil that is negotiated mostly by talking animals, a green world which the four siblings cannot resist exploring to resolve an inevitable battle between Good and Evil, turns out to be founded by the first King and Queen, a London cabbie and his wife, as Narnia proves to be the great social mobility escalator as well as a land of fantasy–born circa 1900, its existence was compressed, indeed, between the massive world wars that parallel or created a new battery of global mapping tools we might call one infrastructure of globalization.

While the readers of the novels were treated to successive volumes in the first half of the 1950s, the withdrawal into a wardrobe during the wartime evacuation somewhere in the English countryside offered a respite from wartime travails and post-war shortages, where they might be able to ascend to the thrones of Cair Paravel as Peter the Magnificent, Susan the Gentle, Edmund the Just and Lucy Valiant, they are far from the blitz indeed. The novels that Lewis began shortly after three schoolgirls from London let London in Sept., 1939 to his home east of Headington, beyond Oxford’s Ring Road, was an actual escape of sorts–if it lay near to where a six-year-old evacuee from the London Blitz in fact died as an RAF bomb fell by accident during training.

]But the map to the shadow land of Narnia was engaging as a hero’s journey, and endured as story of discovery, and of discovering allies in a struggle over Narnia’s future, as much as an allegory of meta-liberation as they are guided by the God-like leonine figure of Aslan. For C.S. Lewis clearly grew determined to craft the series as a map of discovery during the war years, even if it meant crafting a large landscape that seemed difficult for readers to navigate. “I don’t see at all,” he mused to his friend Dorothy Sayers, as he was contemplating the novels that became the Narnia Chronicles, in the rather glum year of 1949, “does the best fantastic lit. come form happy periods & the grimmest realism from ours?” By that time, he’d completed Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe–finished in draft by late May, 1949, and started looking for a publisher that summer, even if the addition of a map for the series was only planned as it appeared in 1951, two years after he first expressed excitement children would immediately “love the wealth of expressive detail” of Baynes’ drawings, and not only to convince the illustrator of her craft. While he felt his storyline needed images for its audience, he was a bit apprehensive about what sort of illustrator to involve, and eventually was famously filled with reservations on the liveliness of animals or animation of his heroes’ faces, if he warmed to her depiction of the execution of Aslan, or perhaps of their necessity to the believability of the Narnian world, or indeed its reality as an actual place.

Lewis, to be sure, possessed a deep visual imagination, that seems to blend a spell by an epiphany, beginning from imagining “a picture of a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood” at age sixteen. But it became a means of Baynes’ work to learn to navigate that space on foot–no doubt a mode of transport Lewis had long intended to preserve a needed orientation to the world as it was being dramatically remapped. if he had a rather brilliant ability to render images and mis en scenes of memorable form, the work that the maps of the series offer is to help us grasp the canvas on which the larger battle in Narnia can be contained–a parallel battle, to be sure, but one which demands an old, and not a new, sense of maps.

If all maps create a sense of place–as well as of space–seeing the relation of places on maps were always particularly important to my reading of the books,–as if the author seemed to strain to encompass a mythography to encompass the expansive scale and scope of the world described in their chapters, as much as a reading guide. They also mapped a new landscape, albeit of fantasy, that responded to the author’s sense of an absence of adequate points of orientation to the world. The difference of these maps from the contemporary wartime maps of military invasions across borders may be harder to discern: for they plot a voyage of as much as the trusting bonds of the characters in a and of talking animals which if war-torn, moon-lit and shadow-drenched, its characters explore and returned to it through the portal of the wardrobe–or collectively drawn into the bounds of a painting of a ship buffeted on its seas. Baynes’ keen appreciation of this lack, I’d argue, led to her rendering of the scale of the new world of Narnia to which the children were drawn by an ineluctable sense of its enchantment, a parallel world existing at an angle to our own, where maps had, in a sense, ineluctably changed to a projection that was removed from the ground.

Pauline Baynes, from Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952)

12. The mythic world was entirely Lewis’ own creation. But Lewis did not clearly map the country of Narnia in the books. His skillful illustrator offered a map that aimed to approximate the Narnian topography–even if he despaired of her knowledge or familiarity with what he felt were the basics of animal anatomy with great dismay, even offering to take her to the zoo. Baynes shared Lewis’ deep hope to summon a moral global order in his fiction–not advocating monarchical restoration, but to restore a sense of harmony in a sharply divided world whose spiritual dimensions might well be considered a therapeutic way. (One user of an Oxford well-being center on a farm called it “Narnia without the White Witch.”) The Narnian landscape was invested with with a local enchantment lay in part in the maps allowing it to inhabited and explored that served to counteract the transformation of the built environment in postwar England. If England now suffers from less tree-cover than most all of Europe–with just 13% of the nation with tree cover–and half of those non-native trees—wooded areas outside Oxford have been preserved since the years Lewis and Tolkien wrote, as the local architecture of Oxford,–a redoubt of architectural elegance even in times of war–fast growing into surrounding countryside and transforming, as the eighteenth century canal system, where narrowboats were once drawn by horses along seventy five miles of canal across forty six locks faced closure in the 1950s as the commercial traffic of narrowboats declined and wharves were closed.

If canals would soon be called the soul of Oxford were protected as heritage site, Lewis was less intent to create a world at odds with modernity, than a shadow-world which emerged as a refuge at the same time as modernity, dated from the creation of the London Underground, and a refuge from it. Almost as much as his fellow Oxford tutor Tolkien, Lewis was a passionate admirer of the antique, and antagonist of the modern; if he did not share Tolkien’s hatred of industrialization, or indulge in a romantic philological apparatus Tolkien provided for his legendarium, the cartographic inventions of their illustrator, Pauline Baynes, offers a crucial benefit to readers who have long fetishized the maps. If the image by which Baynes mapped Narnia was fleshed out and colored in later years, in ways that have been fetishized in poster sales, the leash on which Lewis kept her belie her cartographic abilities and the power of her maps she so convincingly embellished in DawnTreader, a narrative of island travel, that the maps placed in a broad canvas enchantingly uniting Lewis’ episodic writing. Indeed, her map, unlike his own draft, provided the power of clear coastlines of Narnia and seductive mountain ranges in its truly enchanting topography–perhaps a parallel for detailed fantasy board games–

–and a font that seemed to conjure the magic of the place. If the map was based on Lewis’ original, the cartographic insights she offers for a complex land. Did Lewis provide the map in draft from to Baynes, or did she sense that the map of ocean voyages effectively communicated a counterpart to the region whose font indicated its ideal nature to my eyes; Lewis, in contrast, focussed more on ensuring Narnia provided a truly green world for readers who, recently surrounded by the sounds of war, lived in regions where the bombing raids were still visible–as they still were in the London of the 1950s and 1960s, ensuring the survival among a generation of young readers of the so decidedly green lands surrounding the Lantern Waste, Miraz’ Castle, or the Irish-sounding castle Cair Paravel, across the daunting expanse of the Wild Lands of the North.

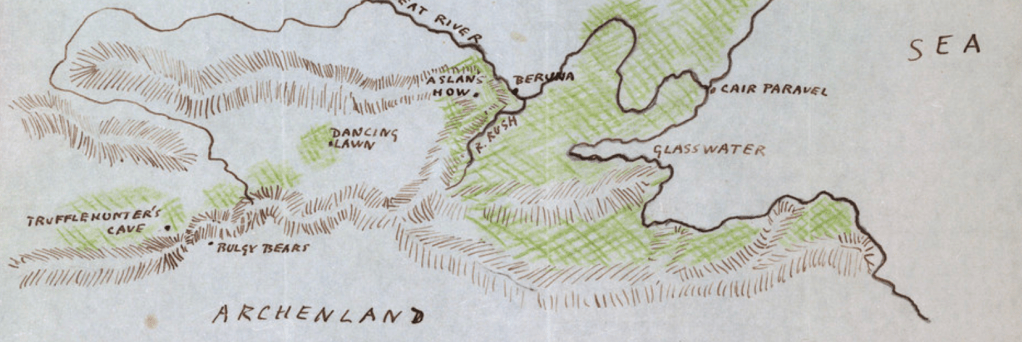

C.S. Lewis, Draft Map sent to Ms. Pauline Baynes/Ms. Eng. lett. c. 220/1, fol. 160r/Bodleian Library

The cartographic missive now housed in the “Bod” is preserved as sort of Holy Grail of Lewis’ creation of Narnia’s fictional topography, and his invention of its map, but the championing of its creation a evidence of Lewis’ authorship may minimize Baynes’ especially contributions as additions of local pictorial landscape. If the towers of Oxford may have inspired Cair Paravel, to judge form a lovely Christmas card his friend Tolkien penned of the university spires as a background for Santa’s sleigh–

J.R.R. Tolkien, Christmas Card of 1932/© The Tolkien Estate Ltd, 1976

–Baynes’ detailed cartographic canvases afforded expansive surfaces for readers to plot each of these decidedly English (if not British) authors. For she penned and kenned a canvas that has been entered psychically by readers, if both books are described as powerful psychic landscapes of their authors–of Lewis’ deep tied to Ireland’s coast, which he visited often as a child at Ballymore and County Clare, or Tolkien’s childhood memories of South Africa, limited to his his first four years in Bloemfontein but featuring an encounter with a tarantula, and vacations the mountainous Swiss Alps he long romanticized as settings. The other worlds that each of their works provided for readers endured a dark twentieth century whose maps were haunted by not only nuclear Holocausts, and amidst the sharpening of national borders in the Cold War, helped sustain an enduring alternative vision of possible worlds against the rising psychic tensions of territoriality. (If the bite Tolkien received as a child from a king baboon spider in the Orange Free State may haunt the man-eating spiders in Middle Earth, the vision is hardly imperial, but maps a foreign space, as did the idyllic coastal visions of the castle at Ballymore or rocky landscapes of County Clare.) The convictions of another world each of these authors in other possible worlds provided enduring psychological relief in an era of the increased psychic strain on the nation-state.

But to create tangible cartographic canvases, each demanded its own illustrator. the map that he provided served as a way to reorient not only the three schoolgirls to the local interest of Oxfordshire as they boarded with him, but a map that countered the uniformity of how mapping agencies had conspired to remap space in radical ways as a consequence of wartime needs. And it was perhaps karmic that Lewis not only encountered the three schoolgirls whose needs he took seriously, despite his rather conservative ideas of gender the led Philip Pullman, who had long read the stories to his classes of schoolchildren, as “monumentally disparaging of women,” her. Lewis was famously disparaging of the artistic skills and aptitude of the woman who provided illustrations for his work–the trained artist and cartographer Pauline Baynes–the line her work drew, or navigated, between cartography and art was, he had to recognize, central to the appeal of his own work, and the critical decision to set much of the most compelling action in his seven novellas off and on what might be called the Narnian shores. Baynes, a deeply religious Christian if with mythical proclivities, was attracted to make these maps as a sort of relitious mission, it seems, concretizing the idealized worlds that both men imagined and wrote.

For Baynes had honed her own line of work–at the same time as she pursued her aim to be a children’s book illustrator–by upholding the line of drawn cartography at the same time as the rise of the Universal Transverse Mercator grew as a tool of mapping cross-border wars. The complimentary tools of marine mapping that Baynes was immersed in the Admiralty Hydrography Office from 1942-45 provided a unique wartime experience that Smith be seen as meeting C.S. Lewis’ own desire to map experience against the grain of war, for the girls who stayed at his home in Oxford, and indeed to recenter a global map from Oxfordshire–rather than from the frontiers of a war that was redefined by bombing raids. As much as using a map to quantify the stakes of bombs in the region where Lewis lived through the war, in Oxfordshire, the qualitative shift in spaces of Oxfordship were best communicated by the shock of Paul Nash’s modernist canvasses of the new landscape of the University town during war, from the fields of Luftwaffe plains he captured as a new land apart, in “Frozen Sea,” and the increasingly surreal sense of this space.

Paul Nash (1892-1946),Totes Meer (Dead Sea) (1940-41), oil on canvas, 101.6 x 152.4 cm. The Tate Britain

The juxtapositions of a new sense of the picture plane, and of the conflicts between new landscapes. lead him to abandon his surrealism, or discover a new sense of meaning of surrealism as a war artist for the Royal Air Force, for whom the dump of wrecked aircraft was a new maritime sea, created not by a shift in the weather, or but a “great, inundating sea [in which] nothing moves, it is not water or even ice, [but] it is something static and dead,” a new cartographic space that was unable to encompass the level and scope of death and mortality of the war. The juxtaposition of these incongruously contrasting landscapes encountered as he moved to Oxford, where he had arrived in 1939, led him to try to balance the inconsistency of the Oxford he knew with its militarization, a new space of overlapping spaces between landscape maps of the countryside and the brute maps of airspace and war, unnatural spaces, a contrast that he captured in the delicate watercolors that seemed to remediate the distortions of overlapping spaces with strong parallels to Lewis’ work, and almost suggest the disconnect of military spaces and the past bucolic space of Oxfordshire.

Paul Nash, “Oxford during the War” (1942), detail. Worcester College, Oxford University. The Atheneum

The two spaces increasingly collided with a poetic poignancy surreal as they did not cohere, even if they did in his gently detailed watercolors and grim oil paintings that increasingly approached despair. While living in Oxfordshire but with access to the private lives and experiences of aircrew, and indeed of military sites that remained intentionally off the map but unavoidably compelling to process and to try to document for posterity–even as the violence of these Oxfordshire scenes pushed the idiom of landscape into new surreal spaces, even as they gained biblical proportions.

The complex balancing act of this aircraft wreckage Oxfordshire, where Lewis lived during the war, was by no means a peaceable enclave, if far from the Blitz; the arrival of four thousand bombs dropped on local airfields and civilian homes made it an aerial war-field, causing twenty deaths and sixty casualties, and the imagining of a peaceable kingdom gained a new premium during wartime years–a project that was real, but also that demanded a new set of tools to map. The arrival of missiles in Oxford, however, in Chipping Norton and Weston-on-the-Green, ensured jarring proximity of a war front, if anyone doubted it, in Oxfordsire’s countryside. The power of uncovering and narrating another Green World for readers was a powerful form of world-making, especially at the beginning of its writing, as a needed moral refuge from a grim wartime landscape.

Other worlds were increasingly mapped in Oxfordshire, of course–from Sir Arthur Evans who from 1900 through his 1941 death had excavated the ‘Throne Room’ and Minoan palace complex at Knossos, which he had promoted by journalistic skills, fashioning a modern image of an ancient empire in Crete, perhaps as a bulwark against the Ottoman Empire, describing Minoan civilization world of priest-kings invaded by the Mycenaeans, the “Achaean Vikings,” in 1450 BC, at the center of an epic history from 3100 BC to 1000 BC, uncovering corridors, coins, seals, and figures–many of which were transported to Oxford’s Ashmolean Library, of which he was the Keeper, meeting an eager audience of antiquarians, creating a durable image of an ancient empire that contrasted to Mycenae as a center of civilization with its own writing (Linear A and Linear B) and numeric system, and including a richly colored restored images of Minoan painting. (Lewis was well aware of the excitement of their discovery: he included a woman with “skin the color of honey [wearing] a dress with her breasts exposed, the dress of a Minoan priestess,” calling Evans’ Snake Goddess a priestess in That Hideous Strength, and describing “Minoan cultures” in 1945.

If the world of Minoans Evans excavated was a new past kingdom no one in Oxford could ignore, and provoked a rage for an archaic imagery of a past world removed–

The racily liberated outré bustier was strikingly created by Evans’ Swiss restorers, but Lewis must have sensed a more terrifying ecstatic ritual, when he recast Evans’ Snake Goddess as a pagan priestess.

As much as he was terrified by the pagan past that Evans was claiming to reveal as he excavated the Knossos Palace, how much more easily would he have been able to look for the opening outside of Oxford of other worlds on that marker of the Mercian countryside, at Huffington and the chalk-engraving of the White Horse carved in trenches of white chalk, removed from battle lines. Lewis was not as tied to toponymy as Tolkien, who was quite attached to the manufacture of place-names of Lord of the Rings from the Mercian countryside, that lost Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of the midlands, whose landscape a sort of resource on which Tolkien drew, as if to restore a lost collective memory, the White Horse but the neolithic burial sites on the Ridgeway, England’s oldest road, whose path, if not echoing the ridge of Aslan’s How, echo its forms.

13. The geographic course of the Ridgeway do not follow or resemble the ridges that cross Narnia laterally, but the prehistoric burial sites along the Ridgeway, as stone barrows at Wayland’s Smithy provide a template for the paralleled Aslan’s How–that “huge mound which Narnians raised in very ancient times over a magical place, where there stood, and perhaps still stands, a very magical Stone.” Akin to the Ridgeways’ neolithic barrow, “Wayland’s Smithy,” a home of the Saxon god of metal-working, echoed in the Stone Table Aslan is sacrificed is on a ridged elevation. The path “the others cannot, or will not see,” echoes the pathway of circa 3460-3400 BC.

Lewis may have been inspired by the Iron Age mountain route from the Chilterns to the Salisbury Plain, as a walker–his rambles parallel the rise of Ramblers’ Associations that lead to the formation of a Countryside Code, begun fom the Ramblers’ Association in the 1940s, leading to affirmation of the Right to Roam whoseprecepts of “Go Carefully on Country Roads” and “Respect the Life of the Countryside” were codified two years after the 1949 Access to the Countryside Act, that parallel Lewis’ imaginary creation of the Narnian countryside and J.R.R. Tolkien’s mapping of the Shire. The hiking and walking maps suggested an ideal of exploration without maps by ramblers.

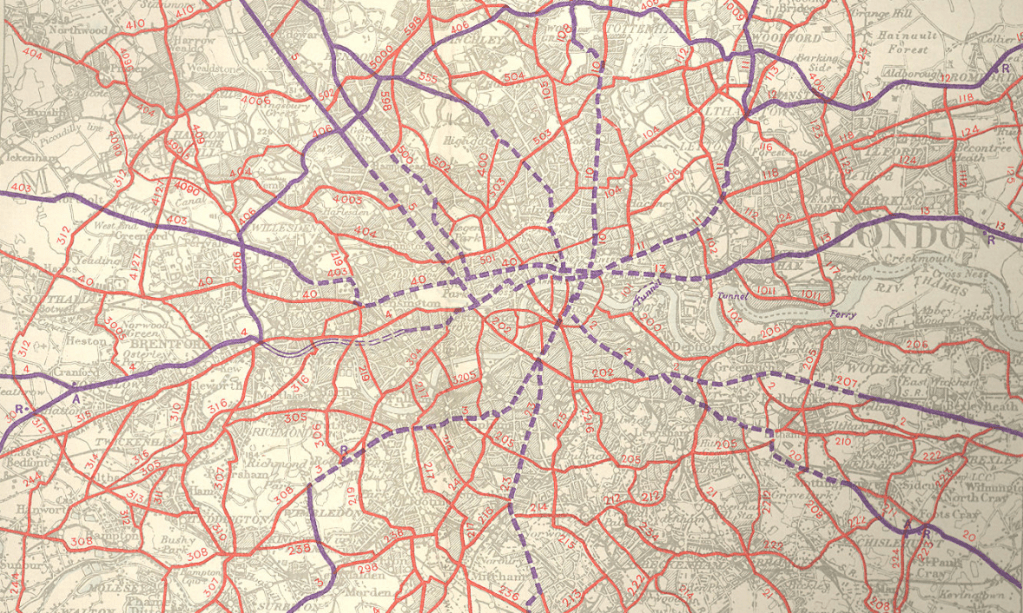

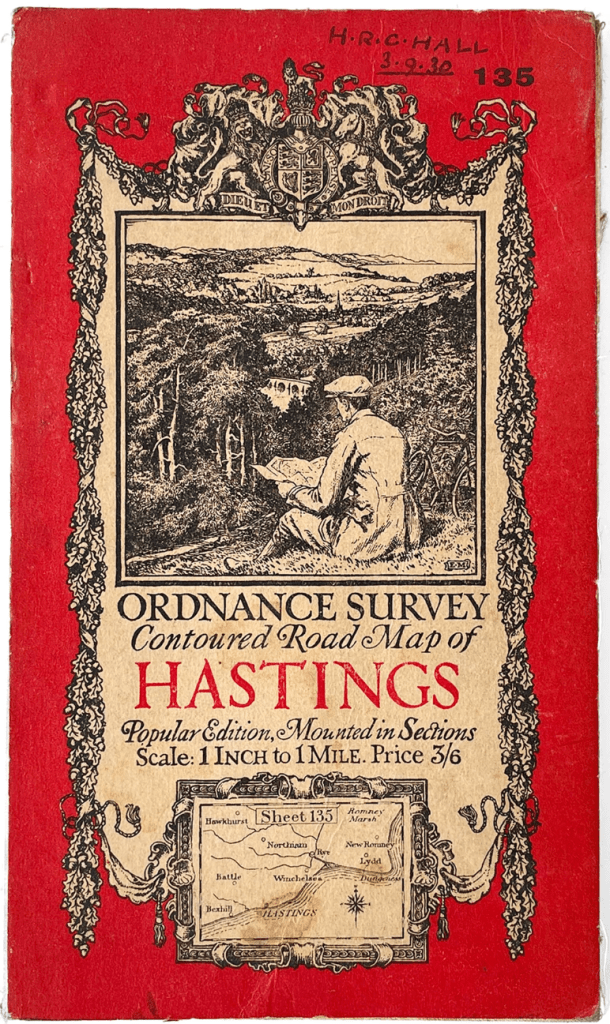

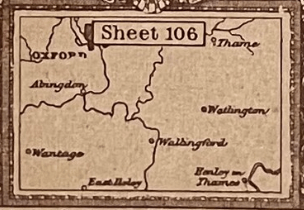

Is there not some justification for seeing C.S. Lewis as a prophet of the Anthropocene? Fearful of the disappearance of green open spaces in England during his life, Lewis may have seen the transformation of the landscape evidenced in the dominance of roadways, rather than topography and terrain, in the OS maps of the Ordnance Survey, which rather than focusing, from the 1930s, on hikers or artist-mapmakers, contrasted to the increasing prominence from the 1950s on the experience of the driver, focussed on roadways and highways, and indeed the world seen from a driving car, in place of the walkability of the English countryside he sought to preserve, even in fiction–akin to the images on covers of the “one-inch” pocket maps below of 1932 and respectively. While the first postwar 1919 OS popular editions had so prominently included, in the case of Oxford, which Lewis would have known best at first hand, for example, an image that integrated rivers like the Thames and the wooded areas of the region along walkable routes of varied topography,–

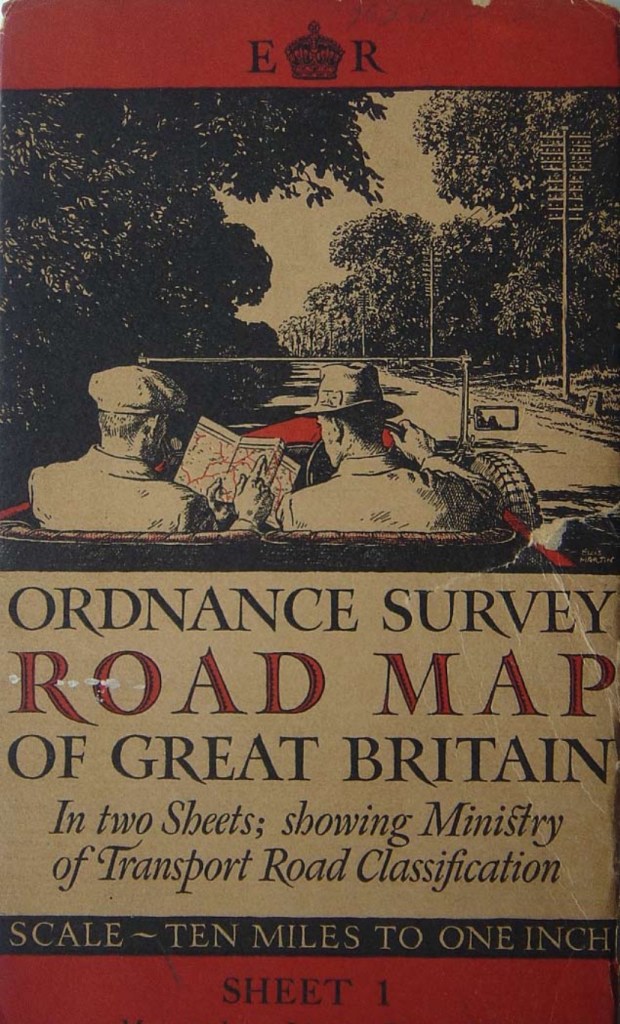

–colors of terrain and forests were replaced by visually distinguishing first-class (red) and second-class (green) roadways by quality of transit according to the Ministry of Transport’s ranking for ease of immediate consultation from 1923. The change reflected the audiences of motorists to which the maps addressed, apart from users from 1919, the first years of peacetime, when OS sought to attract a range of leisure outdoorsmen in its “one-inch” map booklets, repurposing the map agency’s military ends to tourism, hiking, bicycling, and hiking in rural areas. Orienting users to a paved landscape increasingly glimpsed largely from cars met new skills of route-finding–maps were read by keen-eyed motorists navigating countryside with clear know-how as they passed road signs by the 1930s, looking ahead with a bravery akin to a Brave New World of paved space.

Not by coincidence, Oxford University began environmental monitoring of the woodland of the 426 hectares combining grassland and woodland habitat from 1947, monitoring tree, badger, and bird as well as butterfly data and bats, registering environmental change in the local woods’ “natural beauty” for the first time, in an area Lewis and Tolkien themselves often strolled. Was Lewis’ sense of a “discarded image” not only cosmographic, but rooted in such the cartographic choices walking maps of the English countryside adopted in “one-inch” maps as those of Surrey and Hastings?

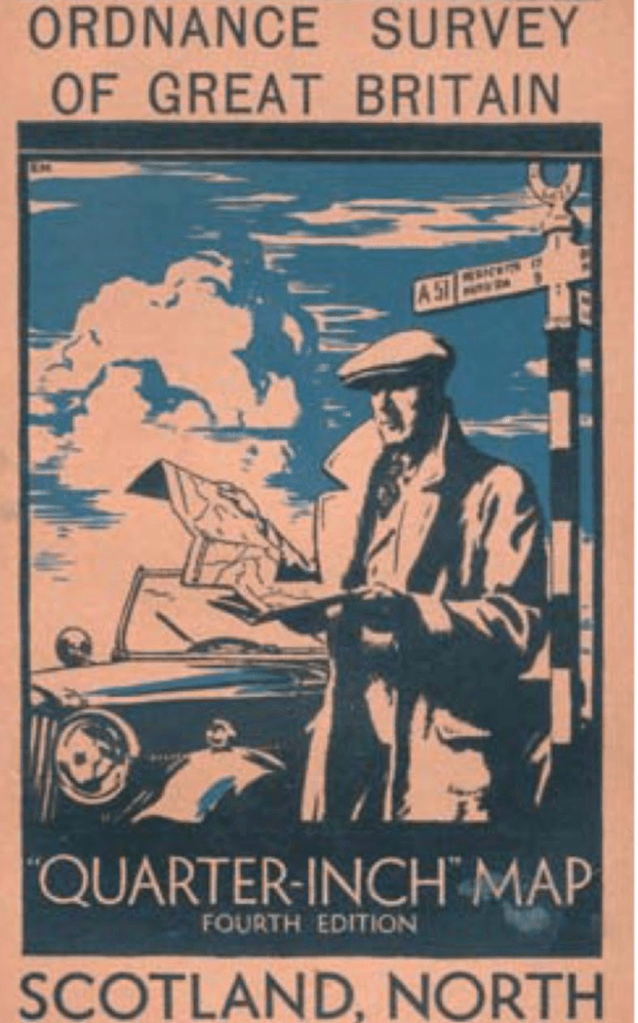

In contrast to the Ordnance Survey maps for military use, the maps of an inch to a mile designed for hikers, motorists, and bicyclists, as well as hikers, rather foregrounded grades of motor roads, reflecting the need for inexpensive editions for a large audience of driving maps. Unlike the map covers Ellis Martin, a draftsman for magazines, had designed in the postwar period, that preserve imagined uses of maps that had encompassing audiences of, say, cyclists, hikers, beside motorists–

–the newly mapped Anthropocene world was one that Lewis, never a dedicated motorist if he enjoyed riding in boxcars, but a dedicated walker, was forced to have negotiated, and undoubtedly would have increasingly bemoaned.

Ellis’ elegant covers had not yet come to registered an increasingly rebuilt relation to the world of the 1950s. But we might situate Lewis in a very immediate way in new audiences of map use, which might make mourn an earlier relation to the admiration and wonder at a depicted space, a “discarded image” in itself–literally, a discarded image. Unlike the older Ordnance Survey, later popular maps abandon pictorial illusion, foregrounding color-coded roadways of an increasingly paved nation of roadways and roundabouts, in place of color-coded terrain that indicated wooded areas by tint: in contrast to the contoured road maps to meet consumers beyond the army and navy. Martin, who addressed these audiences of hikers and outdoorsmen, had begun his career as a field artist for able to map difficult mountainous terrain on the front lines of combat, he became known for his ability to present surveys to popular audiences–most entirely male–consulting maps before landscape views for cycling and motoring, that codified an new image of map users from 1919, in sharp contrast to the military and naval maps that had been created for a nation at war.

If the earlier maps for hikers were meant to suggest a sort of recuperation of the countryside as a land of exploration, the image of a lost landscape was to appear even farther away in time with the Second World War, as roadways dominated the landscape, and military space overlaid the landscape once known and explored by foot in a grid that prioritized road quality.

Ordnance Survey Contoured Road Map, Popular Edition, “One Inch to One Mile” (1919)

Ordnance Survey “One-Inch” Map, 1925

1925 Ordnance Survey Map Booklet, Popular Edition

By 1932, topography receded below road quality, as it were, both in the OS maps made for motorists foregrounded classified roads, mirroring Ministry of Transport maps with an eye to route planning, which were reprinted every year in the 1930s.

Road maps were increasingly produced for a market of motorists, foregrounding networks of paved roads, to be kept in “glove compartments,” privileging an anthropogenic space of built roadways. And already by 1927, the focus on roadways and the measurement of distance on roads as the A31 contrasted to the fields that surrounded Barmouth and Aberystwyth, as if the user was displacing one form of navigation of the countryside with another, more efficient, rooted in the shrinking of space that the maps actually performed in shrinking ten miles to an inch to but half an inch–evident in how London now stood, trunk roads in purple, by 1948, or after the professionalization of mapping systems on coordinates with a new level of abstraction far less demanding pictorial naturalization prominent in the early road maps of the Ministry of Transport, as they sought to acculturate audiences reading roadmaps to find the most suitable routes for automobile travel.

Ordnance Survey, “Ten Miles to One-Inch” Popular Edition/1930s Style Transportation Roads Classification

Ordnance Survey, Quarter-Inch map, c. 1929 (Fourth Edition, 1933)

The expanding demand for maps and surveys had led to an effloresce of pocket maps in demand, as cartographic literacy was eclipsed by motorists’ maps, foregrounding well-paved highway roads, that eclipsed in place of country roads in ten-mile road maps, reflecting classifications of paved roadways from 1932 through 1962, suggesting a landscape of routes that were most often paved: the prominence of London at a network of trunk roads seemed to be superimpose a new spatial network atop the landscape, in the 1948 “quarter-inch-to-mile” OS Ten Mile Road Map of Great Britain.

Roads were foregrounded in the maps themselves in contrast to terrain, topography, or contour lines, providing the primary tools in maps increasingly made to be kept in cars, as the glorious “one-inch” survey maps were consigned to a cartographic past. When Lewis aimed to craft a more enchanted world of a green world, removed from the roadways of built space. In contrast, he offered a clear moral cosmography to a Midgard, akin to Tolkien’s Middle Earth, providing a durable moralized universe as well as one that was decidedly off the road–and off the beaten path, as he felt that the actual world risked losing moral orientation beyond the perspective of motorists–and the range of different maps that were required for open rural space.

Quarter-Inch Motorist and Signpost (1934; 1941); Touring Motorists (1920); Hiker at Stile (1932)

Narnia was perhaps not early provided with an adequate cartographic apparatus, and didn’t gain one until its third (planned to be its final) volume. The moral map of panoramic scope it unfolded for readers was graphically amplified by Baynes to accompany a Spencerian cosmography in parvo, a Faerie Queene for children of similar dimensions, inhabited by a large cast of mostly talking animals, inhabiting another green world, able to hold sorcerers, magicians, hermits, lions, and battles he brought to life as an allegory of “undeserued wrong,” whose temporal expanse extended by the Witch Jadis, but transpired in but a handful of decades of earth time. But it was also a new countryside, a forested green expanse that existed, when the moral conditions aligned, at the same time as England’s countryside and rural life was disappearing before Lewis’ eyes, even in Oxford.

Lewis famously failed an unprecedented seventeen driving tests before throwing in the towel,–despite acknowledging the undeniable utility of driving from the grounds of Magdalene College to his home in the Kilns, bragged “I number it among my blessings that my father had no car, while yet most of my friends had, and sometimes took me for a drive,” as if it were central to his distinctive preparation for theological study; it was quite literally a blessing, in his mind, and he hardly used the term lightly: he privileged the innate map of one walking afoot, proud to”measure distances by the standard of man, man walking on his two feet, not by the standard of the internal combustion engine.” If “one-inch” maps addressed outdoorsmen, he was seeking a new nature of a compelling map to help audiences conftont far steeper moral stakes.

C.S. Lewis became strident on the subject: he got on his high horse in roundly condemning driving and automobile touring as risking cognitive deficits, and the spaces opened by automobile touring that the OS maps of driving roads imagined as a loss. One might indeed trace these losses within the one-inch maps printed for map users from 1919 to 1931, that promoted a driving “tourism” he saw as compromised. Lewis asked we examine the very claim that “modern transport ‘annihilates space'” literally as a liability, eroding “one of the most glorious gifts we have been given” of an interior compass. He might have meant a moral compass–recalling the enjoyment took in calls of swallow, songthrush, geese, or even swans on long river-walks in the Thames Valley with Tolkien, chatting over the ambient calls of a seemingly vanishing rural world on the Oxford periphery, hardly recorded and indeed erased in maps.

The replacement by the map of place with roadways that were ranked by the Ministry of Transportation’s ranking of roadways as red (first class) or green (secondary) created a new model of navigation that was dangerously removed, Lewis felt, from the experience of the hiker or walker or cyclist in maps that reduce the world to ribbons of red and green, as if this ‘new world picture’ might have a moral and ethical counterweight in the maps of Narnia, among an audience privileged who had not yet learned to drive.

Perhaps nothing more than the image of two gents consulting a map, pondering the alternative roadways by which to traverse the countryside, so popular in the 1930s, created a model of judging distances that lacked any integrated sensory contact with the external world, and a new relation to nature. Lewis worried subtraction of ambient sound in automative transport might leave children deprived, bereft of the sensory contact with a natural world. If he only expressed his concern by terse apprehension, bemoaning the inevitability of a diminished appreciation of the “value of distance” its impact on children’s lives existed on moral grounds.

For the diminution of distance that driving promised, he worried, risked a generation with a diminished “sense of liberation and pilgrimage and adventure than his grandfather got from traveling ten.” Our aural perception create a uniquely embodied sense of “auditory space,” Lewis felt, beyond the visual world that enter the eyes, by which we learn to construct a world that is “extending in all directions around the observer,” a form of spatial thinking of cognitive depth, impoverishing those aware a relation to the divine might, paradoxically, be “simultaneously . . . of closest proximity and infinite distance.”

Very eager to read this post—looks delicious! Can’t wait to finish it!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!