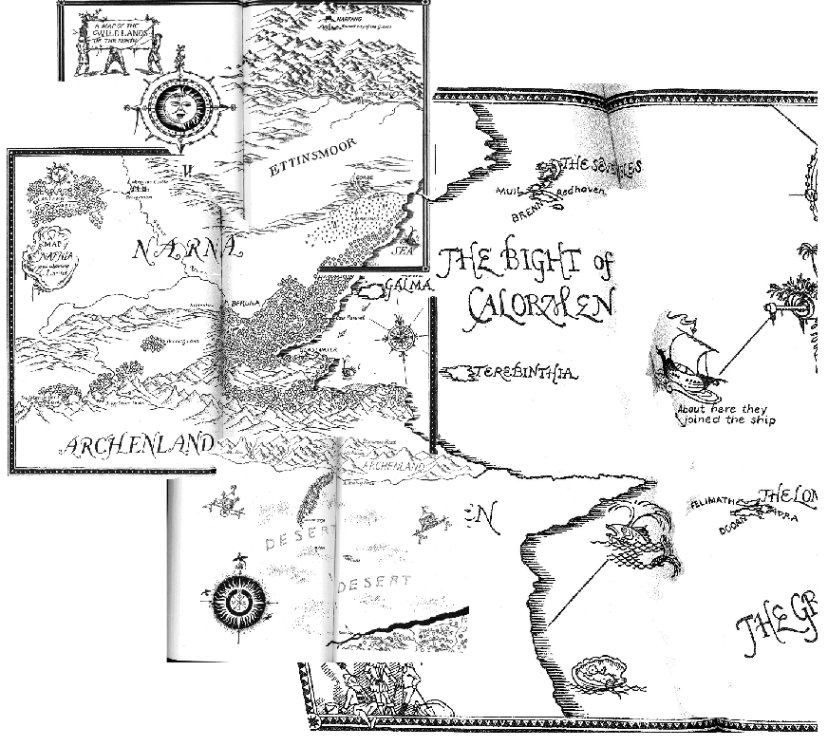

14. This is the sense of readership that Lewis tried to create in Narnia, and which perhaps gave Baynes’ illustrations particular power as they were so successful to achieve. Can one perhaps detect in their collaboration a sort of division of labor, Lewis’ work elaborating the cosmography that he had begun in Wardrobe as a poetics of world-making, if at times over-wrought, but with fixed gender roles, while as illustrator Baynes added the crucial cartographic detail to the maps that brought the book to life? Her expansive view of the Narnian countryside that Lewis had conjured in his text was created in the expansive images of the coastal mountain ranges as the children were carried aloft on the flying steed Fledge, to preserve the green earth of Narnia–that left the indelible vision of Narnia’s Edenic green hills in generations of readers’ minds, adding to the fascination with the immensity of this other green world that existed as a shadow world only accessed in the back of wardrobes made from the wood of a primal apple tree, or a painting’s frame. Inviting seashores, forests, mountains, and lakes provided a visual refuge that Lewis was almost conspiring in the pleasure that as removed from any pollution, paved roadways, buildings, or extra-urban growth.

Pauline Baynes, 1963

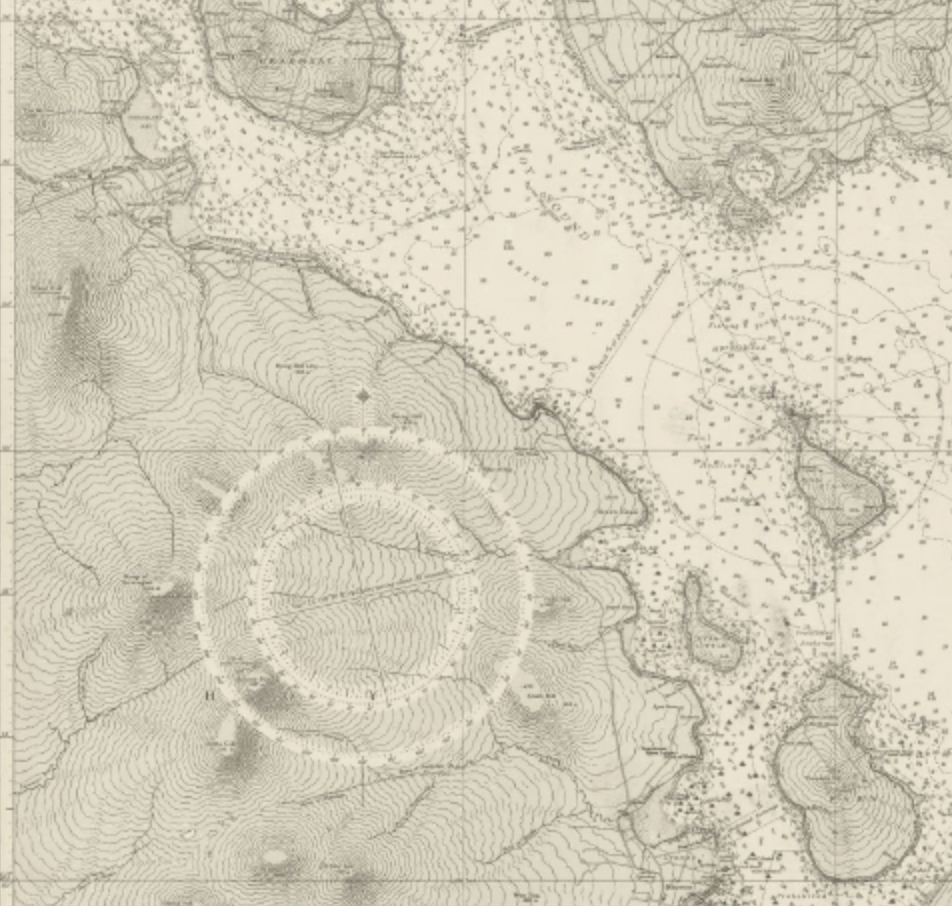

The addition of not only painted panorama but of surprisingly detailed shorelines increased the realism of the maps at their borders. Their addition is likely to be specific to Baynes’ artistic skills. At the same time as road maps had become the dominant means of navigating the English countryside for many motorists, Baynes’ training in rendering the hydrography and coastlines of marine charts as she worked at the the Admiralty Hydrography office detailing marine maps at Bath from 1942-45 were a significant chunk of her wartime life; this work is often noted, but offers a rewarding avenue to examine the intersections between art and cartography, and the functions of the graphic detail of coastlines in fantasy maps. For there is a sense of the love for the execution of detailed coastlines that fills her work, which this post will try to examine, and offer some initial orientation, that suggests how the deeply practiced execution of coastlines of fantasy maps reflects skills she gained in the informative demands of admiralty maps in time of war, an area where visual precision gained a new premium to concretize a physical relation to space, in an era of the abstraction of cartographic signs from place.

But the mapping of Narnia that its illustrator, Pauline Baynes, had been an illustrator who worked in wartime at the The mental achievement of assembling the map of Narnia and its regions is akin to an act of global expansion, interrupting the fear of air raids and incendiaries by the safety of the open countryside that opens before the children so invitingly one learns to assemble the broader picture of the expansive regions to which the books literally open, allowing them to fill out the fictional landscape with a familiarity not present on other maps. And while Lewis walked into an Oxford bookshop, asking an assistant if they knew anyone who might “draw children and animals” for the books he was writing, the books would be lacking their expansive cartographic canvass.

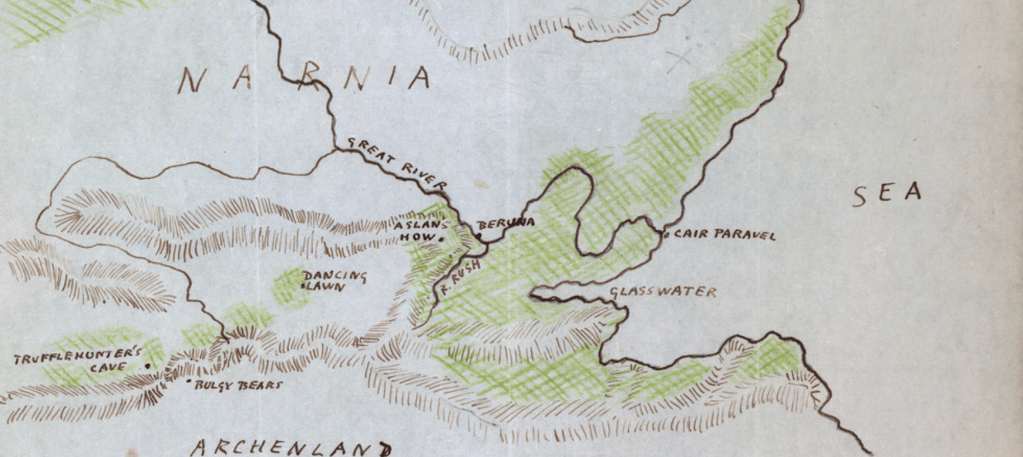

To be sure, Lewis himself stipulated that he wanted a map for the books. He sent her a copy of a mockup in January 1951, early in the series, stipulating that its maps “should be more like a medieval map than an Ordnance Survey–mountains and castles drawn–perhaps winds blowing at the corners–and a few heraldic-looking ships, whales and dolphins in a sea” followed upon completing Caspian and Voyage of the Dawn Treader; he knew that part of the canvas was to be marine. By that time, he’d already completed three of the six books. He allowed “I love . . . the really excellent drawings” of Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, hoping “children will love too [the] wealth of vigorous detail,” but rarely singled out the maps for much attention. Baynes’ exhaustive cartographic contribution would however become quite central to the published text for readers–and to its memory– Lewis, not J.R.R. Tolkien, might have commented justifiably to Baynes that her images “reduced my text to a commentary on the drawings,” months before Lewis met Baynes.

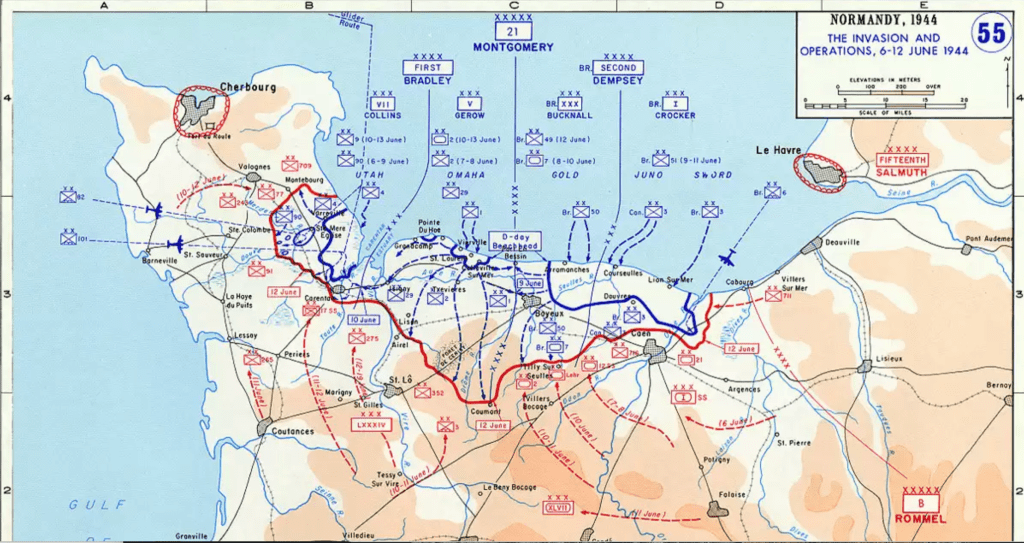

Although it is correct that the tactile value of Baynes’ maps suggested less of a neo-medieval flavor than a materiality of the bird’s-eye view, the perspectival recession of space that allowed Narnia to be so widely emulated in later board games gave it an immersive reality that was absent from the battle map or the maps of airplane travel that were made in wartime, and presented the fronts of combat in news maps. The Universal Transverse Mercator powerfully united mapping systems for army, navy, and air across national lines, and were adopted as a popular legible way of remapping the safety of wartime Europe, and indeed staging the Invasion of Normandy–a masterful cartographic operations of uniting land, air, and sea from five beaches and air support–from a variety of vessels that depended on mapping and sharing the position of German troops on land–

–pioneering in how took the beach front as a front of war and several beachheads as strategic sites of landing, as the Juno, Gold, Omaha, and Utah sectors were staging pads for amphibious assault. Baynes’ work in hydrographic charts did not directly involve D-Day, of course, but the othering image of a military map that allowed military to attack and capture some 200,000 German troops was a massive success as a military operation, not only in entering Europe by doing so by surprise, staging naval bombardment, aerial surveillance, sweeping onland for mines, and securing beachhead that was occupied by German troops stationed at what they believed were strongpoints along the shore.

Shores were in the news as edges of military territory for tactical grounds, and the warmer shores of fantasy books that Baynes designed recalled a homey sense of the coasts that readers came to love. If Baynes was working in wartime on charts for the Admiralty Hydrographic Department in Bath while illustrating childrens’ books, the introduction to Tolkien in 1948 that led her to work of C.S. Lewis’ works as its six volumes were published annually from 1950-66, as a sort of palliative against the wartime experience from the Oxford Don. To be sure, as Jonathan Crowe notes, the decline of the pictorial map tradition in the postwar period meant that far fewer hand-drawn maps–or “illustrated” maps–were drawn, in part as the new syntax of exact mapping on a grid gained such preeminence that the pictorial maps that were made embellished the geodetic gird, iconically used as a symbolic coverage of airline travel, but converted it into a truly panoramic pictorial form.

The panorama of Narnia were quite distinct. And if the conversion of C.S. Lewis to Christianity may predate the war, the enchanting nature of the Narnian maps were decisively drawn after the war, as the post-war publication of the series seemed to re-enchant a world where war ruins were still dotting the landscape immediately outside of Oxford–one might think of Coventry, indeed, whose ruins not only persist, but whose ruins, devastated by aerial incendiary bombing when the Luftwaffe decided to bomb the city as it was the center of manufacturing munitions and airplanes, rather than to bomb a civilian space, was a reminder of the continued wartime ruins that surrounded London, dating from the Blitz, and the English countryside.

The continued presence of war, and indeed the continued presence of the ruins–a new Cathedral was not built in Coventry until the early 1960s, when its soaring modernist architecture was opened as a symbol of postwar progress and economic resilience, featuring woks commissioned form postwar artists and a mass from England’s preeminent composer, Benjamin Britten, as well as sculptor Jacob Epstein. But the ruins continue to haunt the Oxfordshire region, if they also were an icon of British survival. And as much these state-commissioned works aspired to transcendence, affirming the place of England on the global map and affirming its centrality and buoyancy of its economy after the bombing raids– even if sections of London remained unbuilt–Baynes’ maps of Narnia and Midle Earth endured as the preeminent forms of transcendence for generations, providing the most engaging and enduring cultural forms and icons of navigating an actual world–even if they were fantasy.

The ruins of Coventry, long so central in national memory, are perhaps less upbeat, but continue to provide a sort of portal to time travel in science fiction like Connie Will’s To Say Nothing of the Dog,in which an Oxford student of 2057 is found returning to the earlier era of 1940 and the Blitz, to help Oxford’s History Dept. after an American donor has offered to rebuild the Cathedral exactly as it was–as, presumably, the staying power that the Cathedral’s ruins were imagined to always hold have lost their power, or symbolize the new ability to restore objects through time. Yet Coventry has faded as a site of memory, one might argue, while the memory of Narnia has only grown. The fantastic landscapes offered for both childrens’ books was not only more seemingly human, but existed on a scale that resurrected a departed cartographic idiom in new countries of escapism, that have formed a renewed interest in fantastic geography in later years. The staying power of these places was to be sure due partly to Lewis’ and Tolkien’s own crafting of neo-medieval narratives.

16. But the shadowy territories of both fans of Icelandic saga were animated by the discovery of a distinctly different cartographic illustration by Baynes’ steady line, making them more recognized and more palpable as places of a lost past–if they perhaps echoed the prehistorical paths of the Iron Age settlements on Oxfordshire’s historic Ridgeway, perhaps a site of religious activities and temple, in its large burrows of likely ritual use. If Lewis loved the forests–and was a huge fan, not surprisingly, of Wagner, who adamantly protested or scoffed at Ian Watt’s theory Rheingold be seen as a myth for modern capitalism, updating the view of George Bernard Shaw, not a myth, was quite committed to shaping a world that allowed readers to love the “jagg’d skylines and deep rallies of a mountainous country” that he loved in Derbyshire and the East Midlands. As Lewis worried in 1935 that by the time he grew old there “will hardly be any real country left in the South of England,” Narnia’s green valleys were a way of hedging his bet that they would remain in some reader’s mind. If Lewis loved to walk above the Iffley locks just outside of Oxford, in the flat fields by the Thames near where the old Norman church–one of the finest unaltered Norman churches in all England, built circa 1170–who carved stone doorway ringed by beakhead carvings is echoed in the God’s eye oculus that reconstructed a Norman style–his imagination ranged far more widely as he talked, as he walked there, about the possibilities of exploring the central Brazil sailing 1500 miles up the Amazon River, revealing a longstaning hunger for exploring a larger range of expansive landscapes.

C.S. Lewis, Draft Map of Narnia for Pauline Baynes (1951)

Perhaps the Ridgeway in the Mlaverns provided a nearby basis to imagine Aslan’s How or mountain ranges around Cair Paravel and around Berunda, the shores were quite deftly concretized because of Baynes’ considerable cartographic skills. Baynes lovingly and attentively crafted the canvas of Narnia not only as a prospective views–opening up before the children near the Eastern Sea at the end of the Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe–to offer a standard for fantasy maps by their communication of spaciousness. The sense of spaciousness may be a childhood memory of place from Lewis’ own memories of the Antrim Coast of Northern Ireland, where Flora Lewis took her sons, Clive and Warnie, on holiday, and remembered a not yet two-years-old Clive declaring he was “not going home” at Ballycastle as his mother planned their return to Belfast. Lewis never sufficiently praised Baynes for the maps, beyond admiring their “vigorous detail,” but betrayed a deep dissatisfaction. He chided her by asking asked if she didn’t “realize how hideous I had made the children” and even invited her to study animal anatomy; Baynes, for her part, missed any Christian reference in the story, even if confessing “while I was drawing Aslan going through all the awfulnesses, when he was being tortured, I was crying all the time.” Did Lewis not bother to share what thoughts motivated his work, or did, more likely, he understand the drawings as just entertainment for young readers?

But the map of Narnia that appeared in the Dawn Treader provided a powerful reminder of the very experience of immersion in Lewis’ Narnian landscapes, while reading the books and even after their reading was complete. The memorable episode in which Lewis comes to describing his intent for his readers is Lucy Pevensie’s reaction to reading in a three-page story in a magician’s book, in Dawn Treader, where she is overcome by enchantment as its illustrations become few, leading her to be so immersed in its text to forget “that she was reading at all;” at that moment of pleasure, “she was living in the story as if it were real, and all the pictures were real to,” Baynes’ maps preserve what many remember as their first experiences of reading, and return to, agreeing with Lucy “‘That is the loveliest story I’ve ever read or shall ever read in my whole life,'” as they wish to return to read and re-read the book for the rest of their lives, even if the books could not be turned back to be read, and as its final page so frustratingly became blank–leaving only what Lucy remembered in her mind, and asking her to fill it with its details, as she could only exclaim in disappointment, “‘Oh, what a shame! . . . I did so want to read it again. Well, at least I must remember it. Let’s see … it was about … about … oh dear, it’s all fading away again.'”

17. Least it fade away, we need to return to the maps. The expansive landscape of Narnia is often tied to the verbal map that unfolding before the eyes of young readers, and in their minds. It unfolded, biographers have argued, in ways that might well mirror Lewis’ own recollections of childhood memories of the Irish Sea coast. The long-expected visit to the castle of Cair Paravel that is the book’s conclusion described as an operatic set the appearance of a “little hill towered up above . . . the sands, with rocks and little pools of salt water, and seaweed, and the smell of the sea and long miles of bluish-green waves breaking for ever and ever on the beach” with the sound of seagulls may have been a childhood memory in itself–“And oh, the cry of the seagulls! Have you ever heard it? Can you remember?“–but the opening up of the maps that concluded each volume of the series from 1950-58 was a landscape that seems to stand, as a surrogate, in many readers’ memories. In ways that seem to hew to the authenticity of the maps in the printed books–rather than the large canvas that Baynes made on the hundredth anniversary of Lewis’ birth–as if they were authoritative, suggests the broadening mental cartographic canvas that unfolds for readers of the seven books.

But the maps provide a deeper reading of the permanent and present action that we encounter on ever-expanding canvases in the successive volumes, trying to hold together as a coherent whole, like an updated version of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex maps, perhaps, if far removed from Oxfordshire.

While these maps were drawn, for the most part, for books written in the 1950s, they were haunted by a landscape of World War II, and offered her an opportunity to revisit many of the skills Royal Engineers’ Camouflage Development and Training Centre in Bath.

If Lewis met the future illustrator of his books in 1949, but if he had considerable questions about her drawing of human expressions and animal anatomy, the “wealth of vigorous detail” in the maps are in large part what intrigues the eye. Lewis was a bit spiky when he summoned Baynes to his weekday chambers at Magdalen College, up toward Headington Hill, picking out nuts, ever the aesthete, from the airy towers–themselves often seen as models of Narnian landscapes, as the deer that live in Magdalen’s grounds in a dedicated enclosed Grove–

–when, rather than directly engaging a woman he had a hard time repressing his attraction, and was perhaps a bit put off by, that must have reminded Baynes of a bird, who deflected her attempts to engage him picking at nuts. In public comments that he felt Baynes lacking in abilities of fitting suitably graphic expression of his heroic characters’ emotions, asking if their “rather plain” faces might be in the “interest of realism, but do you think you could possible pretty them up a little?” Perhaps Lewis was more accustomed to the deer of The Grove as a land that he wanted to inspire wonder for readers, but the images of children were perhaps less crucial to evoke awe than the magnitude of expanse in Baynes’ effective maps.

The blank faces, however, do sort of work: we imagine them as blank slates, but are sucked into the maps that C.S. Lewis seems to have understood well, when he responded to a congratulatory telephone call after the series won a prestigious Carnegie medal, led him to respond warmly, “Is it not rather “our” medal?” He had complemented her early on for her use of “vigorous detail,” she long worried that her “drawings were very far from perfect or even, possibly, far from what he had in mind,” perhaps worrying that she had not done the justice to his text he later affirmed. But the crispness of the characters were less important than the animals, in many ways, and their simplicity served to mirror the chromatic variations of a deep sense of light and shadows into which all the creatures that rejected Aslan had sunk into his shadow, doomed to destruction, as the grisaille windows of the Magdalen Chapel suggest a world of moral shadows and light, in its monochrome stained glass version of Michelangelo’s Last Judgmement—

Richard Greenery (circa 1630, restored 1793), West Wall of Magdalen College Chapel

–the rich lines of the spatial map of the Narnian world preserved its considerable holding power– even after the books ended, and even if “our own world, England and all, is but a shadow or copy of something in Aslan’s world. The book had in fact described as Narnia as but a shadow of the “real Narnia, which has always been here and always will be here.” Amidst the allegories, puzzled blank faces seemed to endure. They allowed readers to project themselves into the adventures,–even if they didn’t emotionally identify with the trauma of Father Christmas being banished from the Narnian world. For all the spiritual elevation of shadows in Lewis’ work, the lines of good and evil that were heightened in the realization that the White Witch grows stronger in dark magic, and even “as Adam’s race has done the harm,” in Aslan’s words, “Adam’s race shall help to heal it,” the temptation to evil is always, always present, and Narnia always at risk of being invaded by dark forces–Telmarines or outlaws from Archenland. The very dark was accentuated in the witch Jadis, who completed the darkest edge of the deeply moral geography Lewis opened for readers to scan.

It was not an unproblematic image of moral agency, placed in a foreign landscape that was parallel to the human world, a true shadow world honing a moral self. The role of gender role among the children was not, to put it mildly, that diverse in this ponderous moral universe. As we’ve been reminded by Philip Pullman, who used to read the series to his classes he taught, as my elementary school teacher did, that Lewis perpetuated what are now dangerously stereotypical gender division among the four children an enshrined an image of the everyman as white, middle-class, and male in pernicious ways. Pullman’s critique may respond to how his own work was taken to task as “semi-satanic” for depicting a cosmos as ruled by a senile deity–far from the Lewisian project of creating a Republic of Heaven–his detection of the Christian conservative undercurrents of the fantasy world Lewis fashioned may have benefit from blank nature of those faces helped, whose division of traditional gender roles is outdated. Pullman is quite earnest about the importance of creating a place for belief in a world affected by despair, suffering from a failure to create a sympathetic connection with the universe, that the panacea of the order instilled by a Christ-like lion may seem out of date–if the figures of a moralized world of animals among human frailty are deep.

Yet from writing in his own preserve in Magdalene, Lewis was a bit of an observer apart, with his own unprocessed emotional life, at the very time that he was constructing his alternate cosmographies. While he was entrenched in his ways, perhaps not surviving well with time, the uncertain attitude he had to women, and his won flustered encounters with Baynes, who he seems to have never confronted directly, but never ceased to intimate his dissatisfaction with hurt the woman who worked so well for him. (Did Lewis’ sense of the propriety of gender stereotypes and difficulty interacting with Baynes lead his projected series to suffer in ways that Baynes’ work could well have remedied? Perhaps they did in unavoidable ways.) But the Baynes’ maps offer a needed grounding for the shadowed landscapes Lewis used to such great effect in Narnia–and the dramatic contrasts between darker shadows and light in Lord of the Rings–as shadows of morality are given a greater tethering by Pauline Baynes’ elegantly clear line.

Very eager to read this post—looks delicious! Can’t wait to finish it!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!