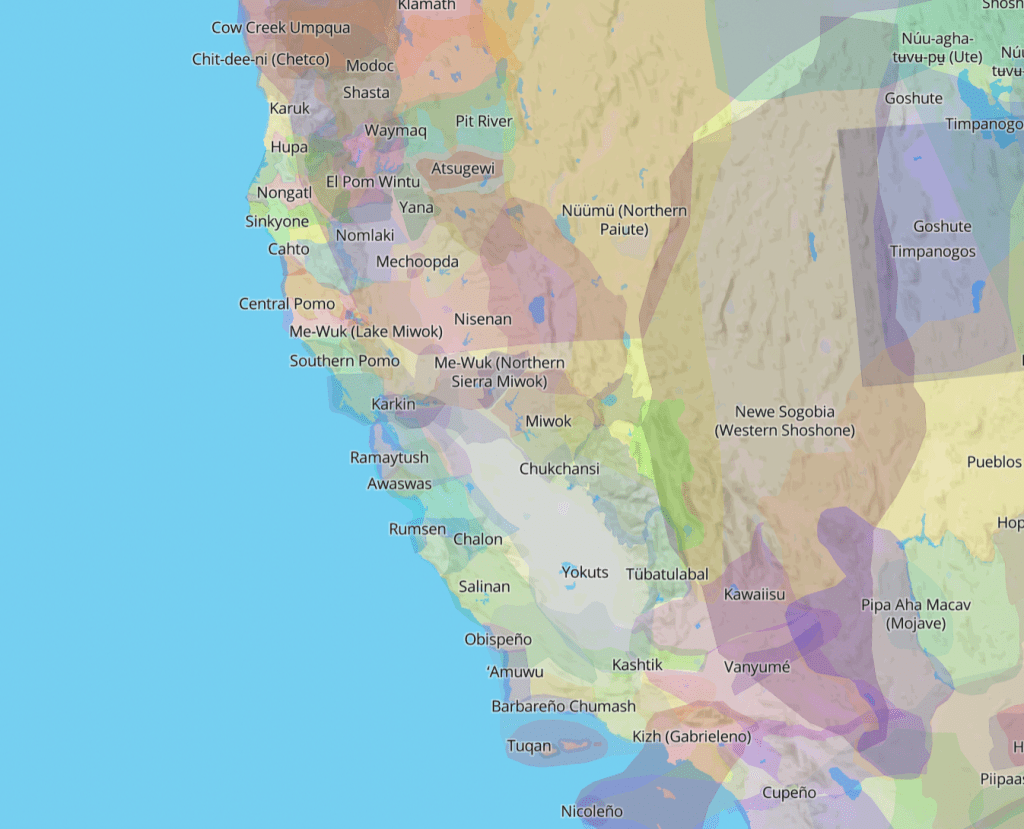

The shift of the coastline as a starting point for describing the land’s settlement and inhabitation promised quite productive pedagogic tool even for fourth grade California history courses that the state mandates–shifting a sense of their relation to place, and the history of the earliest inhabited area in northern California and the Bay Area, and the many tribal territories and villages of hunting and gathering groups in the regions for centuries before the arrival of Spanish conquerors who displaced them, all but demonizing their lifestyle and quite productive sedentary ways of life.

California’s Indigenous Peoples and Settlements/Native-Land.ca

Kroeber had admittedly offered new sense to the boundaries of indigenous lands that would alter and rock the existence of fixed preset regional boundaries of land-governance by counties and municipalities, back in 1922, and that were reaffirmed as “new boundaries” of native lands, back in 1955, that had in that epoch challenged, surely if only implicitly, the Cold War definition of sovereign lands and sovereignty as Eastern Europe had by then solidified into clear bounds of zones of influence, and the lines between North and South Korea that led to the DMZ would be negotiated in ways that imposed the sense of strict boundary lines across most all the world. Such categories were the categories, even more problematically, of the Bureau of Land Management, and indeed of the Bureau of Indian Affairs that had confined the indigenous peoples to set bounds, and used the toolbox of boundary-drawing to confine a wandering sedentary peoples to a fixed black of bounded space. T o be sure, Kroeber’s mapping of native burial sites and encouraged the exploration and pillaging of such sites, by amateur collectors, in ways that had done a huge disservice to the very cultures he was mapping, as the collections of the UC Berkeley’s Robert H. Lowie Museum of archeological artifacts had perhaps encouraged.

Kroeber’s pioneering 1922 map of the indigenous settlement of California’s expanse was a replication of the state’s boundaries, to be sure, an active cartographical re-bordering and rebounding of areas of indigenous settlement that mirrored the reservations, if it expanded them to cover the continuous area of the state. In making the question of indigenous inhabitation a state question, he was reflecting his work at the University of California’s Dept. of Anthropology, where he had begun as a mere Temporary Professor in 1901, hoping to found a department of a new discipline in the museum that Phoebe Appleton Hearst would fund, hoping to construct it as “another lasting monument to you and your devotion to the university and your desire to advance knowledge and to encourage the higher culture of the people . . . ” back in 1904. The earlier ethnographic map was a sort of summa of that legacy, an advancing of knowledge of native habitation of the state for higher culture, if the spate of renaming and erasure o the memory of enslavers, racists, colonizers, and settlers had caught up Kroeber in its net, as Kroeber’s values and conceptions of the indigenous were unrooted as violating ideals of inclusiveness. Kroeber’s map was premised on the mapping of linguistic groups–the negative of actual territorial land claims–that removed the indigenous tribes and triplets from the possibility of land ownership, or rather divorced the inhabitation of regions of the state from autonomous governance.

Map of Indigenous California in Alfred L. Kroeber’s Handbook of the Indians of California (1925)

After all, what Thoreau had in his account of the river-voyage The Week on the Concord and Merrimack bemoaned the eradication of native grasses, plowing up old graves, and transformation of former hunting grounds as the result of building towns with “ancient Saxon, Norman, and Celtic names strewn up and down this river,” there might be a way to undo the erasure of the resettlement of the state able to reverse if not remediate the displacing and distancing former indigenous inhabitants from its map. What we must see as Malcolm’s final project was in part of a continuation of Thoreau’s poetic project of the river to restore a reparative relation to this past, hoping to restore a reparative relation to this past, imagining to be reclaimed as the existence of wrongs that might be righted. He was seeking to offer an ability to front the place of native peoples in the entire state, and invite us all to front the frontiers into which indigenous habitation of California had been effectively contained. It didn’t help that Kroeber himself had quite publicly dedicated himself to rectify “the rights and wrongs” toward California Indians following the genocidal wars following the American Gold Rush,” as he told San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club in October, 1909, while preparing a map to direct Californians’ consciousness to the inhabitants of the land whose earlier inhabitants they had, know it or not, rather unceremoniously displaced.

Even the Dept. of Anthropology in the end voted to accept or sacrifice A. L. Kroeber and his work as worthy of commemoration, and indeed to offer his memory up as a sacrificial lamb of sorts. A new generation of the Anthropology Dept.–the elders of the Department, Laura Nader, Paul Rabinow, Nancy Scheper-Hughes, and Alan Dundes respectfully if vigorously dissenting–endorsed the name change that was boosted by local reporting and accepted or rubber-stamped by a large supermajority of 85% of votes of community members and University of California faculty that the Building Name Review Committee accepted. In copious local reporting of the renaming, Alfred Kroeber was slandered and wrongly remembered for actively promoting a genocidal movement completed forty years before he arrived in the state, but whose logic was argued to survive in his work. And the first to be sacrificed was the totem of the Kroeber map, an artifact to be unceremoniously purged from memory as if in a collective rite of purging collective wrongs.

The purging of collective “guilt” paralleled growing concern of the recent wave of deportations of eleven million immigrants in California–and the parents of 1.55 million children in California living with an undocumented parent–in what was to be a rehearsal or dry run for the massive shifts to immigration policy in the nation’s history in Donald Trump’s second term, and the rapid and unceremonious undoing restriction created in 2021 on policies prioritizing deportation of migrants profiled as threats to public safety, border security, or national security finalized in September 2021. Did demonization of Alfred L. Kroeber for what were deemed objectionable and indeed reprehensible practices of research help ward off those deep threats to civil society?

The denial of citizenship that was extended to increased numbers of migrants was perhaps thought to be expatiated by denying the denaming of the Anthropology Dept. as if to eradicate the prominent founder of anthropology at U.C. Berkeley from entanglement in the stripping of rights of all indigenous Americans at a time when indigenous were not included in the Census, which first made a concerted effort to train census enumerators to include native populations in 1890, if the Superintendent of the US Census made efforts to tally indigenous populations in 1850, and by 1860 included an effort to tally those who had renounced their tribal affiliations and moved to cities–as if they had integrated within civil society–but used special schedules to tally Native Americans in 1910, when Kroeber first mapped the groups of indigenous Americans in his textbook. The U.S. Census included a rather dramatic instance of an enumerator on horseback confronting an indigenous also on horseback in 1990, before a rudimentary house of concrete blocks, in order to suggest the far-reaching jobs of census enumerators to tabulate the nation.

U.S. Census Enumerator Meets Indian-American in New Mexico, 1990

Was not the final energetic project of Malcom Margolin an ambition to remap California from an indigenous perspective rather than as a state, an undoing of the stale nebbishes of Kroeber’s map? Malcolm was eager to make a map able to lead to a new state recognition of indigenous land names beyond title, and the recognition of the expansive coastal lands settled by Miwok and Costanoan settlements before the Gold Rush, and indeed the survival of indigenous names for more than casinos? This was a way of rewriting at some necessary historical distance the iconic map of Kroeber had introduced, and had become an object of such scorn, derision, and self-righteous objection by the early twenty-first century. Malcolm took his energy, and channeled it, from such projects designed to shift attention to alternative avenues of perspective-altering thought, able to send out a shockwave in the immediate environment from his ground zero, akin to the huge thunderclaps one found in the Sierras that offer all the phenomenological and perceptual evidence one needed of the Great Spirit, as antiquatedly orientalized that indigenous inheritance might be.

Removing Official Name from Kroeber Hall, Dept. of Anthropology, UC Berkeley, January 27, 2020/ Berkeley CA

At the same time as the renaming of Berkeley’s Kroeber Hall, this would have been a mighty mission for Malcolm and an unseating of the Kroeber map indeed, one that might be yet another thorn in the side of the academy he was antagonistic if a beneficiary of in securing the place of his press as an alternative site for education and indigenous knowledge over the years at Heyday Press, publishing the important scholarly work of Greg Sarris, Tony Platt, and others, showing, respectively the vitality of local native indigenous histories and historians, and the counter-history of the land grabs of native lands that allowed the land-grant universities to flourish, and indeed for federal funds to exist that enabled the State of California to establish its first mining, agriculture, and mechanical arts school that definitively displaced native knowledges in The Scandal of Cal–using the Berkeley-trained tools of Jurisprudence and Social Policy to attack the underpinnings never yet fully contemplated of the origins of the university in the erasure of those old place-names from the state map. Malcolm was perhaps a university gadfly, but had used his perch beside the ample collections of UC Berkeley’s Dept. of Anthropology, begun by Kroeber and his wife, to unbox the collection of indigenous remains kept for future study, and reassess the possibility of a restoration of artifacts and objects to a larger public than the university had ever been able to address.

Could there be a more effective writing of indigenous presence in the map of the state than Kroeber had provided? Or were we wrong to incriminate the mapmaker for designing a map that had effectively marginalized the indigenous relation to the land, and indeed only objectified that presence as an object of study, and indeed demonized for his collection of sacred remains within the Anthropology Museum as if they were objects of study, not indigenous possessions, without any consent and in degrading ways? Could the ability of such renaming extend to the renaming of lakes that heroized individual indigenous male tribal leaders in wars that settlers waged, from Tuolomne to Tenaya, be challenged if not displaced from the maps of federal lands, as preserving a limited idea of indigenous heroism? Those storied meetings of Margolin with these elders may have not acknowledged their work in the formation of his hugely influential introduction to indigenous patterns of life. If he was without academic training, Margolin’s hope and aim to preserve these lost memories didn’t follow citation practices or attribution of sources, which may have elided the voices which he was the medium: Malcolm, born to a Lithuanian immigrant in Boston, where he was raised in an Orthodox home, reminded me of no one more than my grandmother, who gathered recipes from the Galician immigrant women in Queens after her marriage to preserve the cooking of which she had no clear guides for her new life.

There was a sense of a needed if willful recreation of a community she had left, but could piece together through cooking practices she was either too young to have learned or, without a mother, missing a piece of the transmission of living memory she assembled on the spot as needed in the right place, even far away from home. Malcolm was a medium for a generation without any indigenous voices on hand, and the towering nature of his inspirational vision made up for that lack. (And he never ate pork, if he never held or honored any religious beliefs.). This was, moreover, a form of ethnography at its best and most proper sense, of a writing that was able to rediscover an ethnos where it had for so long been obscured, hoping to animate it again as a resource that we needed in the poverty of a cash economy. His eyes regained a conspiratorial glint remembering visiting Leonard Cohen when he was living on the Greek island of Hydra, locals claiming to be the children of shepherds came repeatedly to the house he thought he had bought outright, demanding payment for an ancestral home that Cohen always obliged them rnot slamming the door shut, but stoically wondering how many times he’d have to purchase it again, as if this were a parable of reincarnation more than a scam two middle aged North American Jews entertained themselves by nourishing, in on the game but willing to play along with the local for the beauty of being part of a pastoral economy far from home.

Malcolm’s favored dismissive adjective to describe or deride those who were less curious or less rigorous of the respect of local cultures–nebbish–described the less effectual, the pitiable, meek, nebekh that never matched the appreciation of the entire culture Ohlone Way sought to describe. I’d been especially interested in the naming of coasts and shorelines, fishing rights and access to shore, and the farming of coastal oceans for seaweed and seagrass, that seemed a cool project in itself. When I told Malcolm of my interest in shorelines and indigenous coasts, at the mention of open water swimming in the Bay, he immediately lit up, describing, in short order, his own swimming off Hydra on visits to Leonard Cohen. The animation of his eye when he was living in Piedmont Gardens was itself transporting. If Malcolm was a bit ashamed of the sort of food he received there, missing, more than ever, the martini his doctors would never allow him again, the worst indignity old age had presented, we had a nice evening in the dining room, rather than eating in bed, and he created an imagined community of former residents of note, creating a new end of life community, if, sadly, he seemed hardly able to bring himself to talk to other residents, and more eager to bask in the glow of discussing old times in Berkeley, and predicting the revolution that was soon to arrive in the Trump’s second presidency and there street protests he was expecting would once more be provoked across the Bay Area and America.

There was great appreciation of having a special dinner in the dining room, approached with a sense of relish that made me glad to have visited him after he contacted me from the home. After an extended bedside chat, I picked up a prepared meal to join him and listen to his stories. (A man who contained so many multitudes can be excused for regaling his visitor he had invited, on a day when he was mostly confined to bed, who I left after three hours still with a twinkle in his eye, concealing embarrassment with the urgent assurance, “Next time we’ll talk about you,” as if I hope he knew he had a lot on his mind and few audiences that day) As I left his room, he slouched down a bit in his bed, I felt some comfort in that I’d been his audience, and realized how importance the audience was not to be nebbish, but to be effective in his work and strivings for expression. I felt a bit elated, glad that I made the visit, even if I don’t know if his rhapsodic imaginations of swimming off the Greek island and drinking retsina with Leonard Cohen were pulling my leg–according to AI, the two never met–but it was a good story, and I actually prefer to believe in the deep kinship felt by these two Lithuanian Jews of the 1960s, floating in the Aegean in pastel trunks.

Being active and effective was central to Malcolm’s mission, and encouraged his energetic promotion of local festivals, consciousness raising, and publication of like-minded writers. Priding himself in his ability to network and bring together people, indigenous and not, and encouraging effective ways of preserving land claims and historical realities increasingly lost to the present, the map would have been a major memory-work for the state in his final years. Overturning preconceptions of Spaniard colonists that dismissed the indigenous culture and beliefs not as landholders, but as stake-holders whose presence time and the poverty of written memory had all but erased, but which he would nourish. Could an API provide a revolutionary way of understanding the custody of each as sovereignty over land, waters, rivers, and shores were increasingly threatened and looking for new forms of legal articulation in an age of climate change?

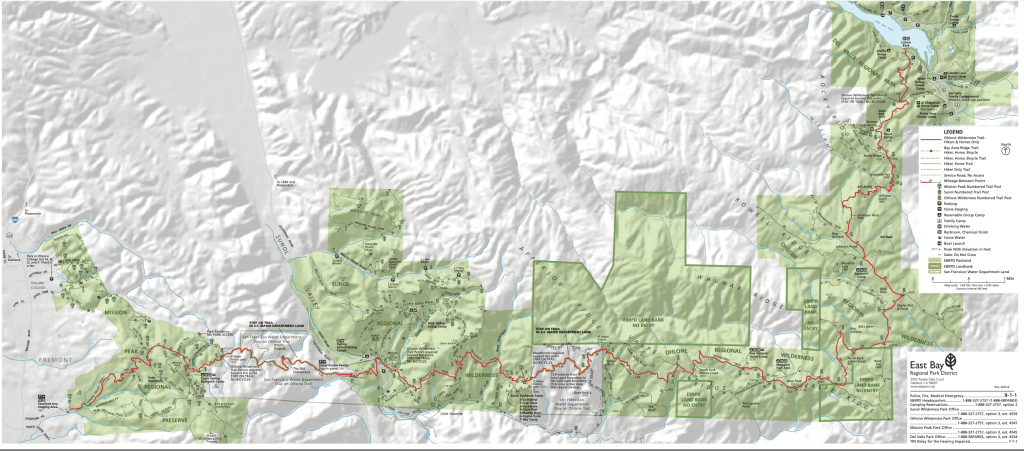

Malcolm perhaps cannot be blamed that multiple indigenous in the region self-identified as Ohlone after the success of his 1978 survey of indigenous cultural, lifestyles, family and historical patterns of settlement long before the Gold Rush. For Margolin’s work, begun in a heyday of interest in the older ways of the Bay Area, lead to preservation of historical trails along the Sausal Creek and other Bay Area creeks-if the Ohlone language group did not acknowledge Chochenyo, Costanoan, Ramaytush, Rumsen, and Tamyen cultures. Finding Malcolm on his walks around the Bay Shore trail, as if in his natural habitat. The official naming of the Ohlone Trail by the East Bay Regional Parks was a re-remembering of the indigenous who long inhabited the region from the shoreline of the bay to an undefined boundary of a ridge in the East Bay Hills from the modern Alameda County line, northward past the Alameda Creek on San Francisco Bay’s east shore, clearing the paths, as it were, for future generations lest they not be forgotten. May his memory be a blessing, and a cudgel too. We need those paths. And we need them to be kept and swept clean, not to stop forest fires, but to be open trails that can best orient ourselves to our open space. The trail survives him, and is a trail that can be walked on today, in our national parks, and doing so will preserve the memories of those who actively walked it and cleared it in the past.

Ohlone Trail, East Bay Regional Parks

.From his bed in Piedmont Gardens, Malcolm seemed to have the excitement of a child again, an aspect which he’d never lost, animated by the fascination that he had with the coming revival of a politics of the street and reclaiming of civil society that the Trump era had to bring. The Era of the Gilded Staircase had to crash beneath its false promises and to end in a wave of popular resistance he told me was coming, and would be a truly beautiful thing, I wanted to share his enthusiasm, but miss him as I had trouble doing so, and wanted so much to have him to provide a sense of optimistic reassurance, even if I don’t know if his optimism would weather the expansion of a Homeland that excludes the indigenous, as if old images of Apaches in Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, holding Winchester carbines and Springfield carbines, might resist the recuperation of genocidal aesthetics,

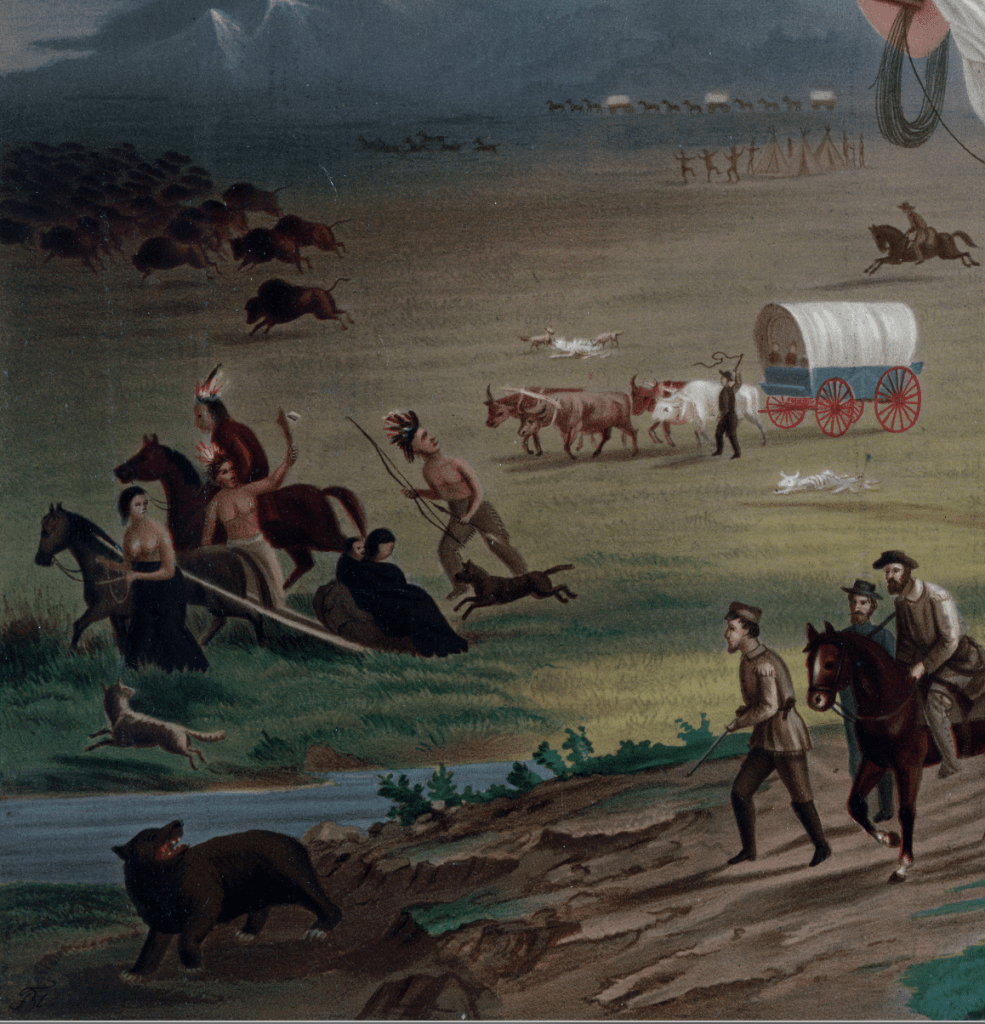

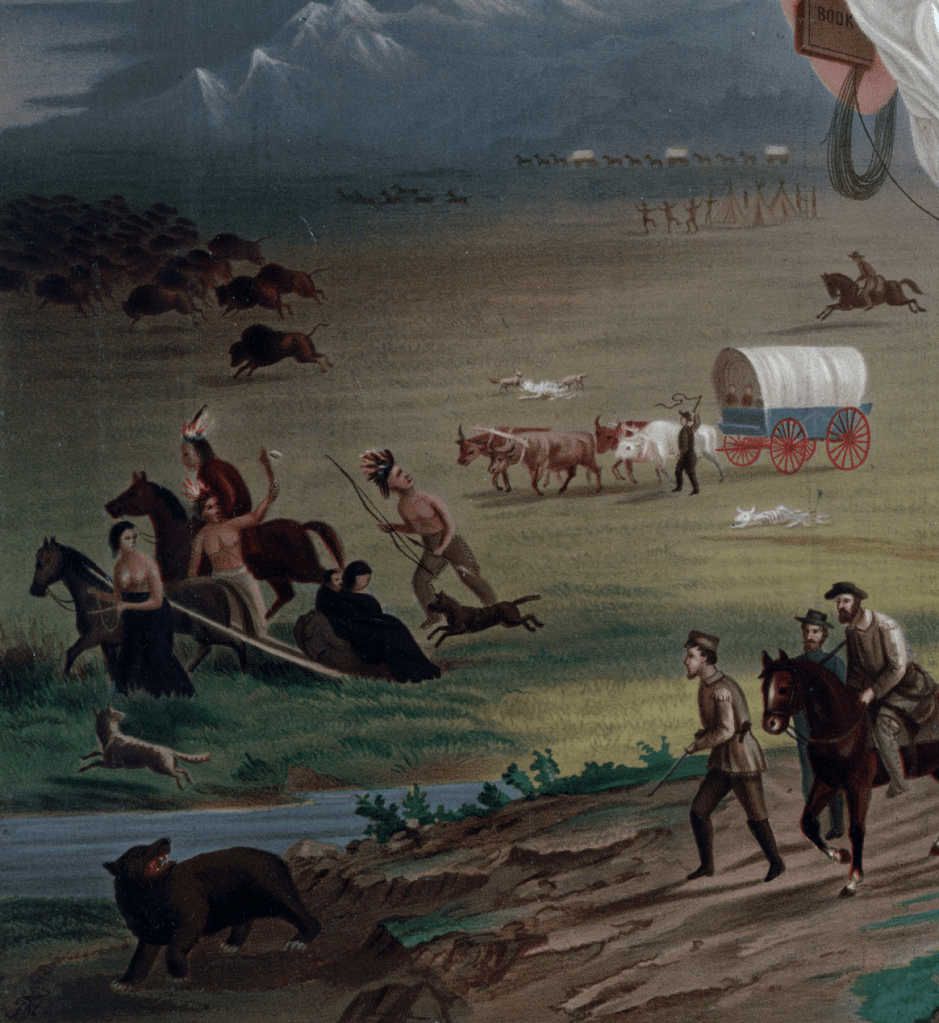

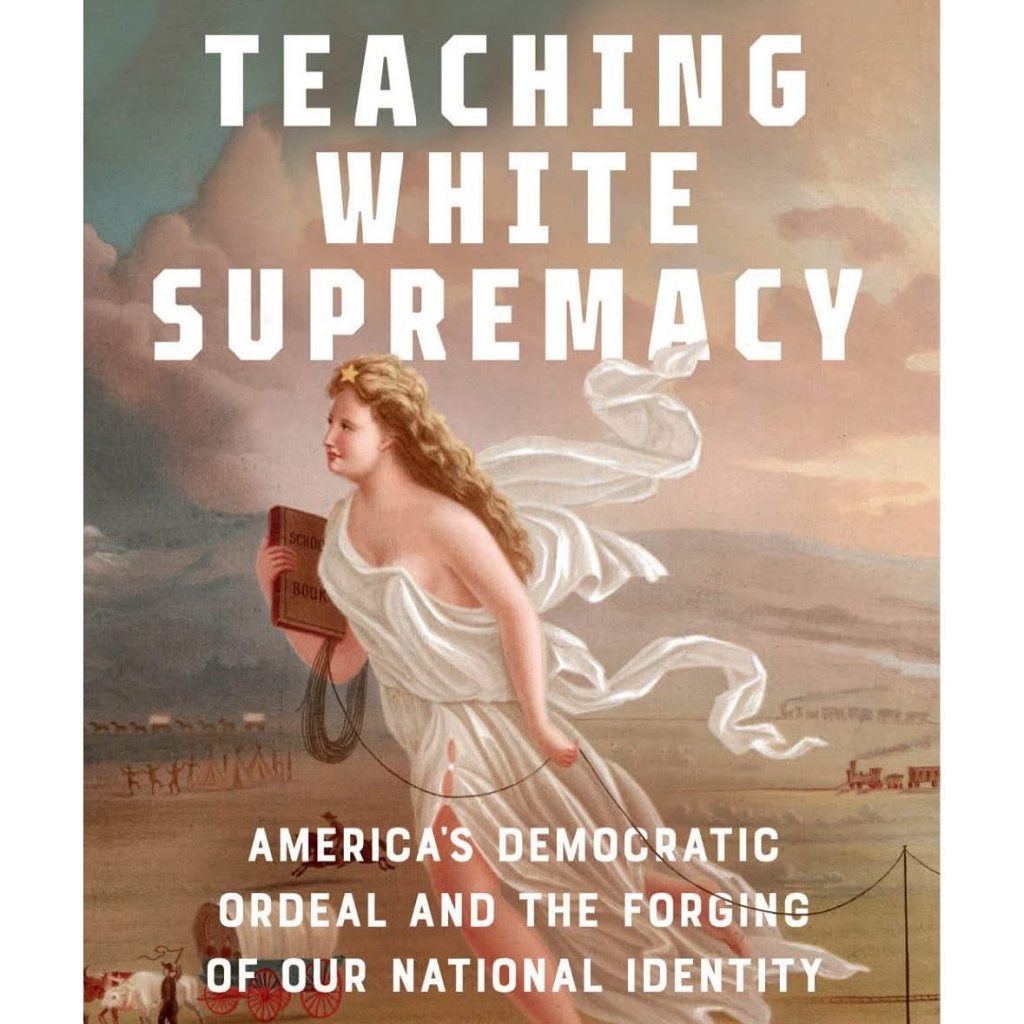

–as the defense of a Homeland promoted by the ethereal floating image of a virginal figure in white robes enlightening the nation by a schoolbook and a wire holding current or telegraph is published on social media without any irony allegory of triumphant expansion over the untamed land as the image of “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending” pushing indigenous fleeing the white man’s advance to its margins, as if they’d never rightly held lands west of the Mississippi–

John Gast, “American Progress” (1872)

–the lower left hand of which foregrounds several indigenous literally being pushed toward their exit, running away from the rather grim settlers advancing on horseback to claim the seemingly open lands waiting to be settled, farmed, and built upon–the ghostly images of teepees as stick figures–the Lakota word that was first used in the English language in the 1740s–

–traced as already vanishing from the land, atavistic remnants beside the electric telegraph wire that doubles as a lasso or whip in the hands of the advancing figure of Columbia, an allegorical personification of the United States, but one who seems to strike terror into the faces of the native inhabitants or indigenous who freeze as they look up in surprise at this large fair-skinned god of the west, bearing on her forehead the Star of Empire. She bears array of technologies of transcontinental transportation impossible to read outside of the glorification of the frontier as an edge of American settlement in American historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 “Significance of the Frontier in American History,”–the towering America standing tall as if embodying the promise of Manifest Destiny that led to the genocide of the indigenous Californians in the coming half-century.

Removed from the land, with no place else to go, they are effectively being cleansed from the map, as the herds of buffalo from the prairies, departing with the bear, wild horses, and previous historical age from the new dawn of Manifest Destiny. This allegoric image of westward expansion, widely reproduced in chromolithograph as a celebration of the expansion of the nation, was a white-washing and justification of the genocidal extermination of indigenous that had occurred in California over the previous fifty years;

the post by the United StatesDepartment of Homeland Security–“A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending. American Progress“–channeled the explicitly racist messaging of over a century and a half ago, featured in 2022 on the cover of Donald Yacovone’ white supremacist textbook, Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity (2022) to amplify a white-dominant narrative in American schools.

America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity

The Gast painting provided a handy shorthand, in other words, of the sense that “our” national identity was univocal, uniform, and singular, embodied by a virginal white-skinned woman whose robe was falling off her bosom. David Yacovone’s tracing of the “arc of America’s white supremacy” is an odious book, marketed as a response to Black Lives Matter–with which the “arc” closes–offering a vision for the future of the nation that the current government seems to subscribe on its official social media accounts. Luckily, the vision that Malcolm Margolin held and cherished focussed on what was truly beautiful, and always sought to “rise beyond the constraints of commercial culture,” holding fast and strong to a differently grounded vision of cultural renewal. It was not univocal, not a single national identity, but existed as a local fabric with a deep history he held close to his heart, and urged we continued to do so as well.

This post was researched and written on unneeded ancestral lands of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone people.