As we face an age when the norms of legal conduct in the United States stand to be shredded, we have been suggested to benefit from looking, both for perspective and solace, if only for relief, to fantasy literature as we await what is promised to be a return to normalcy at some future date. If Trump’s unforeseen (if perhaps utterly expectable) victory has brought a sudden boom in sales of dystopian fiction, as new generations turn en masse to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale or Aldous Huxley and Arthur Koestler for guidance in dark times. The search for points of orientation on a disorienting present is of course nothing new: much as maps of rising rates of mortality from COVID-19 brought a surge in popularity of Albert Camus’ The Plague (1947), an incredible sales spike of over 1000%, alternative worlds gained new purchase in the present. But we look to maps for guidances and the stories of time travel and alternative worlds were suddenly on the front burner. For the surprise election of Donald J. Trump that may have been no surprise at all prompted a cartographic introspection of questionable value, poring over data visualizations of voting blocks and states to determine how victory of the electoral college permitted the trumping of the popular vote; hoping to find the alternative future where this would not happen, the victory of Trump in 2024 provoked a look into the possible role of time travel in a chance to create alternative results about the stories that the nation told itself of legitimacy, legal rights, and national threats.

We had turned to fiction to understand new worlds during the pandemic. The allegory of a war mirrored the global war against the virus–and provided needed perspective to orient oneself before charts of rising deaths, infections, and co-morbidities in the press. Camus became a comfort to curl up with in dark times, to help us confront and imagine the unimaginable as Camus’ text gained newfound existential comfort. A friend insisted on ministering stronger medicine by an audiobook narration of “Remarkable occurrences, as well Publick as Private” in Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (1665), mirroring our own helplessness in spite of modern science, putting the seemingly unprecedented topography of disease in another perspective. London, that global capital which seemed mistaken for the world to many, was transformed as it lost a good share of its population–an unprecedented 68,596 recorded deaths is an underestimate–as the spread of bubonic plague spread brought by rats created the greatest loss of life since the Black Death, permeating urban landscapes with what must have been omnipresent burials, funeral processions, grave-digging, and failed attempts to hill or quarantine the infected–as if it were a land apart, sanctified and ceremonialized to confront death in suitable ways. But t he public trust that had been seemingly shattered by the pandemic–trust in health authorities government oversight, and expertise, led us to turn to past realities as some mode of exit from the grim present.

Mapping Mortality in the 1665-6 Plague/National Archives

As we seek reading with new urgency as alternative means of intellectual engagement, the fantasy literature that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in Oxford, as members of the Inklings, a society meeting regularly in a pub, if not Merton College, sought to create such durable architectures of alternative life to explore. If both writers’ works have been studied as a rejection of modernist poetics, rehabilitating old genres and rooted in premodern poetic visions, the centrality of the maps accompanying each have perhaps been less interrogated as a source for their deeply enduring immersive qualities–and indeed for the durability of the alternative maps to the imaginary that both offered. In recent weeks, a wide array of fantasy books reaching bookstores beside apocalyptic fiction in ways that seem made to order, offering refuges from the present as forms of needed self-care; immersive fantasy books and apocalyptic fiction may be the most frequented sections of surviving bookstores that survive, sought out for self-help in an era of few psychic cures. And it is no coincidence that we also turn to the carefully constructed cartographies of these alternative worlds with newfound interest, immersing ourselves–not for reasons far from those their authors intended–in the mythic cartographies that might be familiar as sources of comfort, that it might make sense to examine the context in which the carefully wrought and designed cartographies of Middle Earth that were conceived by J..R.R. Tolkien and imagined world of Narnia were designed, as an alternative to the new cartographies of wartime that imposed a geospatial grid, in place of a world of known paths and well-trod roads of an earlier world. For the shift in the world that World War II created spurred Tolkien and Lewis to craft alternative worlds of resistance, in hopes for a future that might be made better, not only in a Manichaean struggle between good and evil they watched from Oxford, but to struggle with the future effects of mapping systems that seemed to drain or empty the concept of the enchanted world of the past–the literary “Faery” they loved–and replace it with a Brave New World of a uniformly mapped terrestrial coordinates that risked othering the wonder of the living world. But we anticipate.

In short, we all seem to agree, the newspaper of record found a bit of a silver lining the day before Election Day, fearing the election’s outcome, offering the consolatory message of reassurance there are “few pleasures as delicious” as the ability to transport us “far from our present realm.” Yet the role of illustration in mapping of alternate worlds has perhaps been insufficiently appreciated. And while Narnia and Middle Earth are both seen as a predominantly mythic construction of worlds, removed from the orientation to actual locations, or to the power of transportation to a purely mythic realm, the pragmatic mapping of mythical spaces were alternative universes, modeled on mapping an expansive reality on the national borders of an actually remapped world that privileged the actuality of place, continuity, and contiguity in a mapping of location and position of precision without any precedent in geodetic mapping systems of the Universal Transverse Mercator maps advocated by the British and American military, and increasingly relied upon by the German military in the Battle of Britain.

The meeting of these two eminent architects of the fantasy worlds of the twentieth century–C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien–whose colorful literary works opened new portals for generations have been linked with richly detailed cartographic corpora of persuasive power to redefine fantasy fciton–are tempting to be seen as the consequence of some passionate creative synergy of defining paradigmatic models of escape. At the same time as two veterans of the Great War joined forces in hopes for curricular reform after the war in Oxford University by expanding the medieval readings undergraduates might be assigned, in hopes to expand a consciousness of myths and legends in the texts suited for postwar life, the skills of remapping mythic landscapes in response to the Great War depended on a deep bonds to a cartographer appreciative of the losses and absences of geodetic maps, and eager to help them draft the shores and contours of the “escapist” worlds of fiction that both Oxford tutor would start to draft that set new standards for children’s books and fantasy literature for the twentieth century, that demand exploration as an energetic writing of a counter-map to the new authority of geodetic grids of a uniform space, that focussed attention on the suspending of beliefs by the liminal spaces of the shore, the mountain ranges, and the living landscapes that the smooth continuity of the geodetic grid could not describe or reliably capture. As much as the two dons indulged in the creative power and shared love of William Morris, adventures of Lord Dunsany, and Norse legends, both deeply relied on the illustrations realized with the need for the actual cartographic skill of their common illustrator. For their versions of the literature of quest, Pauline Baynes effectively served as a needed midwife blending cartography and art by to render the palpable landscapes of shores still in need of defense.

Both men acutely realized the need for a good illustrator for their projects of fantasy fiction, able to engage younger audiences that they had little practice in addressing, but whose interest they sought to attract. The prominent work on detailed maps for both books not only reached toward a demand to invest new mythic landscapes with concrete presence for their readers, but to create a new map of the world: to restore an older map of the countryside, to be sure, and forests that were still enchanted with meaning for their readers, but to map the countryside in new ways, rooted not in dots and points but in the continuity of the land. If Karen Wynn Fonstad, a recently departed cartographer of Tolkien’s Middle Earth, confessed missing a sense of proximity to Tolkien’s “tremendously vivid descriptions” in reading after a few weeks, the landscape of the terrain of Middle Earth persuasively offered a counter-world for many, lodged deep within our minds, as well as an escape from wartime when Tolkien composed their initial versions. The transportation powers of the text is real, and its exacting coherence demands a more adequate map than the new military maps of the global space defined during the Second World War, offering a basis to restore the lost sense of wonder that a point-based map elided, in order to provide the detailed landscape of a new form of meaningful quest, and to cast the novels as an opening up of new worlds in a world that seemed, inevitably, to be increasingly comprehensively mapped. These maps offered new spaces of exploration and proving that were outside the increasingly authoritative printed map.

The one-way ticket fiction offers may be deeply under-rated, but the map is critical to immersion in another reality. The Grey Lady of the New York Times indeed ominously but perhaps aptly marked the recent Presidential election’s results by offering orientation in this abundant field, providing signposts to a smattering of new fantasy books, as a response to the national exhaustion or real premonitions of fear. We rightly feel we are without precedent unwarrantedly–we’re confronting a loss of agency that seems unprecedented before the cocktail of environmental dangers of climate change, global heating, and an unprecedented circumscription of individual human rights, reading promotes a sense of agency, as does exploring landscapes outside of the present. If we feel alienated from the country that has again elected Donald Trump as President, to turn from blue and red states to maps of possible worlds form the past–we will need maps, as well as written narratives.

These worlds are however rooted in maps–maps of testing, maps of exploration, maps of selfhood, and maps of futures that are deeply lodged in our imaginations. They are not properly “possible worlds” but instead alternative ones, rendered by maps as regions that can be navigated along new orientational guides, attending to what is overlooked in other maps–maps of the nation, or of the world–by restoring or revealing overlooked orientational signs. If many emerged maps of new scales, dimensions, and resolution emerged in opposition to cartographic practices, the ways that Oxford–site of the Oxford movement, but a time capsule of religious devotion and royalist retreat from the present–became a site where the world was remapped in the interwar years, at the same time as the streets and urban fabric defining Oxford were facing new pressures, a layout bolstered by the archives of unbuilt architecture of urban planners’ dreams, and by the multiple patrons of college architects, among whom nurtured a neo-medieval architecture on fifteenth-century foundations of hammer beams, baroque screens, vaults, spans, and fans in a time-spanning style embodied by the perpendicular gothic in which were set carved gargoyles, plasterwork ceilings, and spires. The Palladian facades fantasias and architectural follies of Christopher Wren or Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) define a place apart, at an angle to the world, of expansive gardens, pathways among ruins of earlier times.

The poetic vision of a light able to pierce Mordor’s darkness and inspire a valiant quest for freedom was born in the neomedieval poem of distinctly Morrissian poetics conjured a counter world in wartime, as German troops invaded France, of a mariner whose course above the earth’s surface sought to preserve the last surviving shards of Edenic light. The complex backstory that he ably mapped for the poem bore the imprint of the earlier war, but crafted to an epic scale. If they recuperate old paths, fed by an Oxonian taste for re-imagining legends on anti-modern maps, drawn by illustrations and a stock of neo-romantic classicism, it was bolstered by an expansive philological apparatus Tolkien modestly called a consequence of being the “meticulous sort of bloke” not given to fantasy. Its maps opened powerful alternatives to the bloodshed and terror of the actual wars of the twentieth century as much as an Oxonian architectural fantasy.

The worlds of C.S. Lewis, Tolkien and others blur the imagined architecture of Oxford and romantic poetics of Morris served as “stock” to imagine an angle on the world, as a terrain that might be explored, and where a quest might still exist. Tolkien was hardly a utopian–and had little interest in “how worlds ought to be—as I don’t believe there is any one recipe at any one time” he described the invention of alternative worlds as that of a “sub-creator”–as much as seeing the author as a creators working with a large scale plan into which his readers were increasingly drawn. The appeal of these maps as invitations to alternative worlds has long been compared to the earlier traditions of cartography–cartographic conventions that formed part of the “stock” on which Tolkien claimed to have drawn in his work. Yet Tolkien’s skill as of illustration has proved to be quite a counterpoint to data visualizations, and indeed to the claims of comprehensive coverage of the world from satellite maps, or global projections, by offering the local detail of a conflict between good an evil that they lack.

In contrast to cartograms that have distanced viewers from the nation, or which suggest a nation grown increasingly remote in purely partisan terms, they allow us to inhabit those worlds in a refreshingly distanced manner, providing immersive senses of reality, as well as a needed perspective on the present. In the same years, Camus himself worried about the lacking landscape of moral imagination in the notebooks of 1938 that were the basis for The Plague,–feeling France could hardly contain Nazi Germany with honor, if it was not seen as a plague: in looking at geographic maps of frontiers, France was “lacking in imagination . . . [in its using maps of territory that ] don’t think on the right scale for plagues.” Thinking on the right scale reminds us of the current need for better maps of the imagination: we need counter-cartographies to the present as much as written works, of commensurate scale, involvement, and attention, as well as preserving a map of future possible worlds,–maps of superior orientation, fine grain, and moral weight to the current world. As much as rejecting the poverty they perceived in modern poetics, each constituted new maps of a world in need of adequate mapping tools.

Their “green worlds” are not pure fantasy; fantasy is a pharmakon for readers. The imaginative space of the written work opened up new absences of political space. In Camus’ prewar novel, Rieux, comes to fear the state’s role in spreading the plague coursing through in Algeria, Americans of diverging politics grew angry at the state policies for COVID-19 they blamed for the pandemic, lacking maps to describe where we were. While widely suspected that Donald Trump himself does not read books–Tony Schwarz doubted he felt inclined to read a book through as an adult not about himself in 2016, and Trump waffled about having a favorite book, citing a high school standard and explaining “I read passages, I read areas, I’ll read chapters—I don’t have the time” among his businesses–perhaps the act of reading is also one of resistance. This absence of any readiness to read may be a failure of the imagination, but also indicates an almost existential focus on the strategic role of deal-making in the present, managing a calculus of variables rather than people, accommodating to evils, and to sacrifice, more than empathy or the aspiration to human connection. The imagination of the moral theologian and philosopher C.S. Lewis to indulge in a children story, even without his own children, began from the domestic acceptance of actual children in his Oxford home from wartime London, it’s well known, when he penned the proposal for a new sort of story, not science fiction or serving more abstract theological morals, rooted in the adventures that he was able to imagine far more clearly of the displaced Londoners he housed–“four children whose names were Ann, Martin, Rose and Peter . . . [who] all had to go away from London suddenly because of air raids, and because father, who was in the army, had gone off to the war and mother was doing some kind of war work”–left to find new models of orientation to an enchanting Oxford countryside with little help from their host, “a very old professor who lived all by himself in the country,” who recedes to the background as a minor character as they are enchanted by their new surroundings. If Tolkien was a far more careful cartographer–far more perfectionist and academic in structuring another world–the alternative cartographies both constructed, this post argues, were midwifed by the illustrator both shared, who used her own cartographic skills to design their immersive worlds.

Creating viable worlds of otherness is an old art, but rapidly grew a far more complicated proposition in the years after World War II, a postwar period that was relentlessly dominated by new mapping tools. The demand for more expansive maps of the imagination paralleled the birth of Narnia and Middle Earth, expansive immersive worlds mapped in Oxford the respond to the claims of cartographic objectivity whose authority both authors whole-heartedly rejected in creating expansive atlases of purposefully anti-modernist form. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien imagined expansive green worlds in multi-volume fantasy books by Lewis or Tolkien as a new atlas paralleling the objectivity of the coordinate grids as the Universal Transverse Mercator, first widely adopted in the post-war period, as their works offered testing grounds for virtue removed from battle or transnational war: the green words of Middle Earth or Narnia may be tied to the success Henry David Thoreau’s bucolic Walden of a life apart won among World War I veterans, years after its publication in Oxford World Classics; but the expansive worlds one encounters in Narnia oriented readers not only to a new cosmography but an expansive atlas of fictional territory. Beyond anything William Morris had drawn or written, the influence of Morris on its writers–and on the woman who provided the romance of their different quests–acquired new scale, dimensions, coherence, and topographic density, orienting readers to landmarks that grew lodged in readers’ consciousnesses so that they seemed the transmission or recovery of previously unknown worlds.

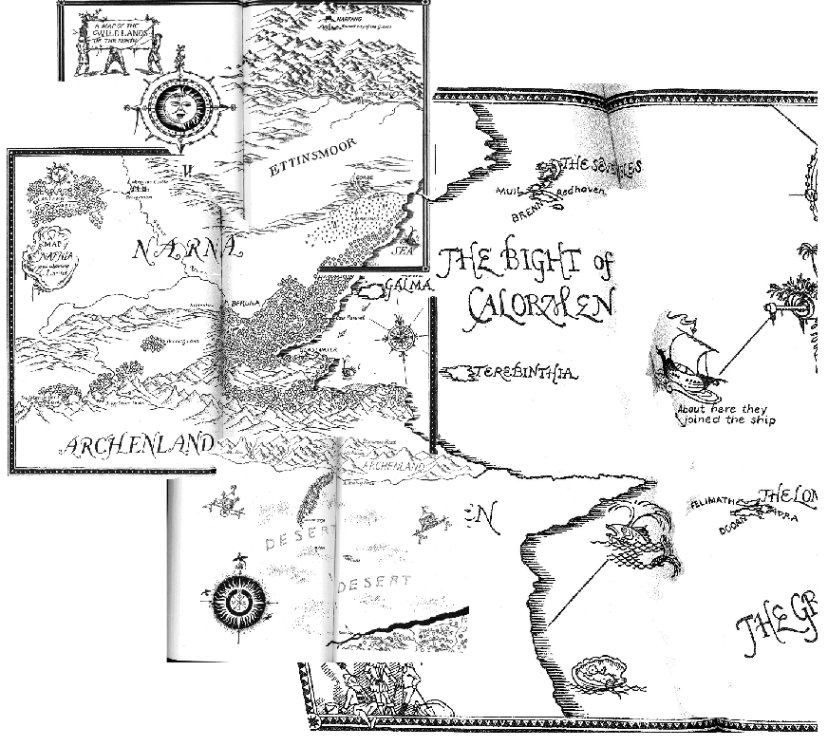

The maps of an archeological recovery of a Medieval landscape of good and evil became immersive counter-worlds because they existed at a distinct angle to the authority of current mapping tools. Indeed, the expanse of Narnia, poised between Archenland and Ettinsmoor, defined not by natural geomorphological borders of mountain ranges, marshes, and desert rather than by abstract lines, without lines of longitude and latitude, grooves a uniquely suited testing ground for honor, duty, and valor of a timeless and mythic nature, suited for testing bravery and aptitude for a preteen; it is an atlas that unfolds in the sequence of books–here assembled from several volumes–that maps a world that was lost with the rise of maps of geodetically determined borders mapped by a grid to coordinate military engagement, logistics, and the coordination of ground and air travel. Its maps are dominated, appropriately but the faces of a sun that peers out from the mariner’s compass rose–and by the natural worlds of forests we are in danger of overlooking, not as so many lost green worlds but as living landscapes.

Narnia Maps by Pauline Baynes, assembled from the Endpapers of Volumes in Chronicles of Narnia, 1950-1956

Continue reading