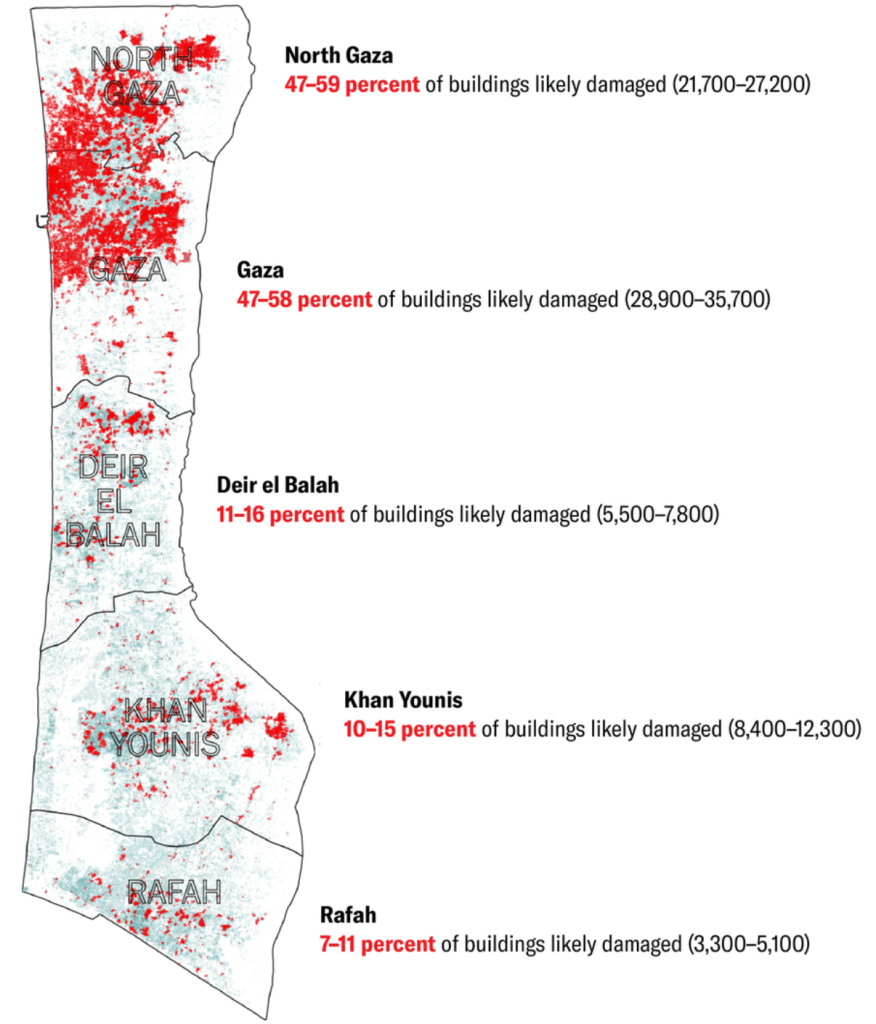

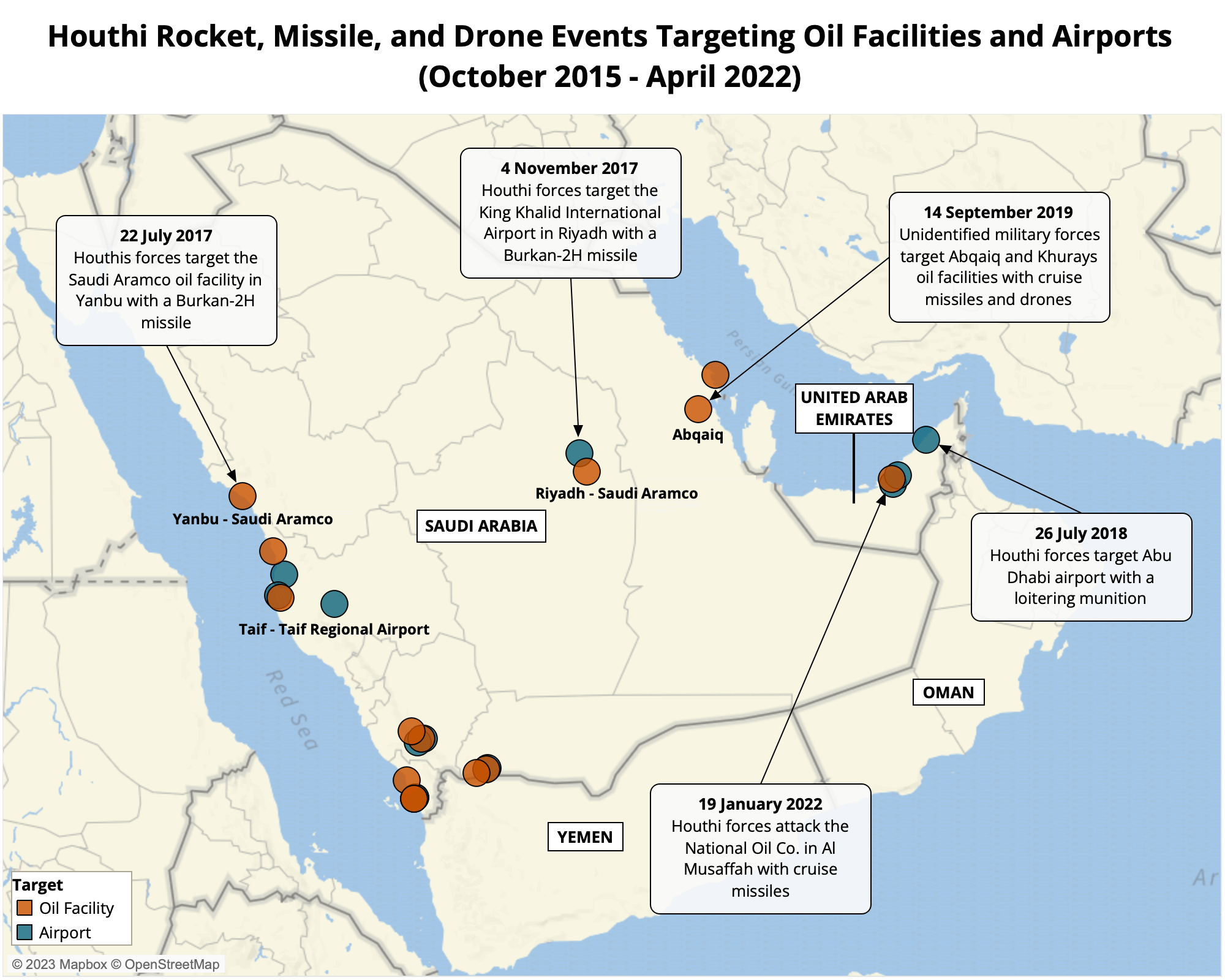

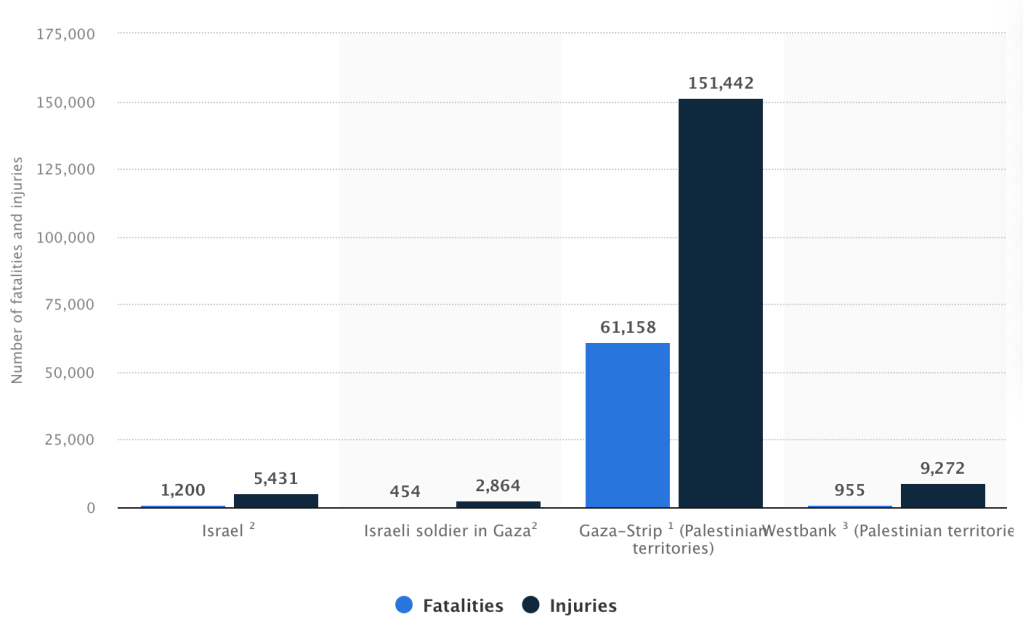

Plenty of blame has been going round this election cycle on the Democratic Party for having given material assistance–if not tacitly supported–in the bombing of Palestinian settlements in Gaza by Israeli Defense Forces. The drumbeat of disquiet about the Democratic President for lending apparently unfettered support to Israeli bombs and air force in destroying the Gaza Strip is not only a cause for pronounced disquiet. The destruction may be a determinant factor in an election cycle that could open floodgates to untold ramifications of both foreign policy and domestic inequality. But as the world focussed its eyes on Gaza, we have taken our eyes off Trump’s promotion of a deeply symbolic if imaginary tie to Israel, and Israeli claims over Palestinian lands.

This tie is not only tied to imperial legacies or geopolitics, but stands to gain a new zeal, melding the early Zionist idea of a “greater Israel” with American expansionism and a Christian Zionism of peculiarly Trumpian stamp. Many believed that Netanyahu, confident in the hopes of Trump’s future victory offering a basis to enter the once and future President’s good graces, and led Thomas Friedman to argue that Netanyahu only suggested to be interested in a ceasefire in Gaza in order to achieve “total victory” of hoping to occupy both the West Bank and Gaza in the near future by escalating the war in Gaza before Election Day, in order to proclaim his ability to work toward “peace” after a Trump victory, having established the transactional value of reoccupying Gaza, while helping to return Trump to the White House again.

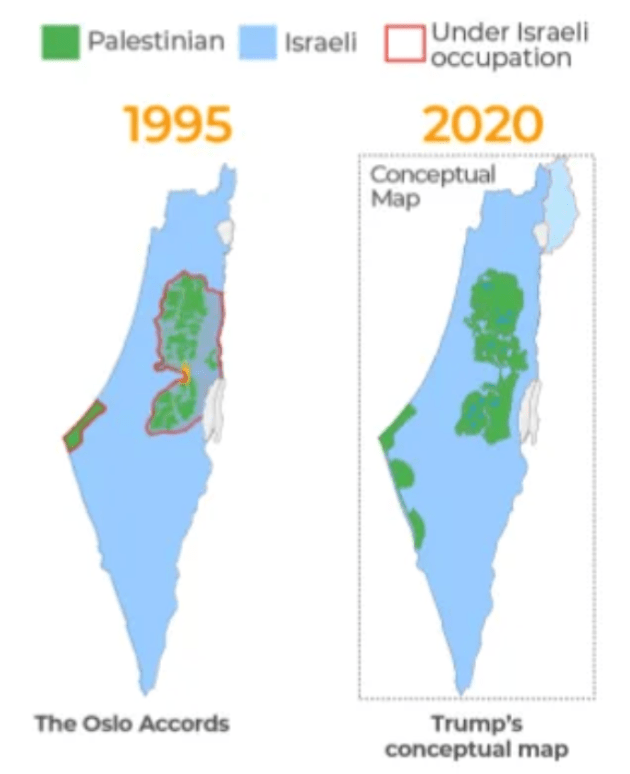

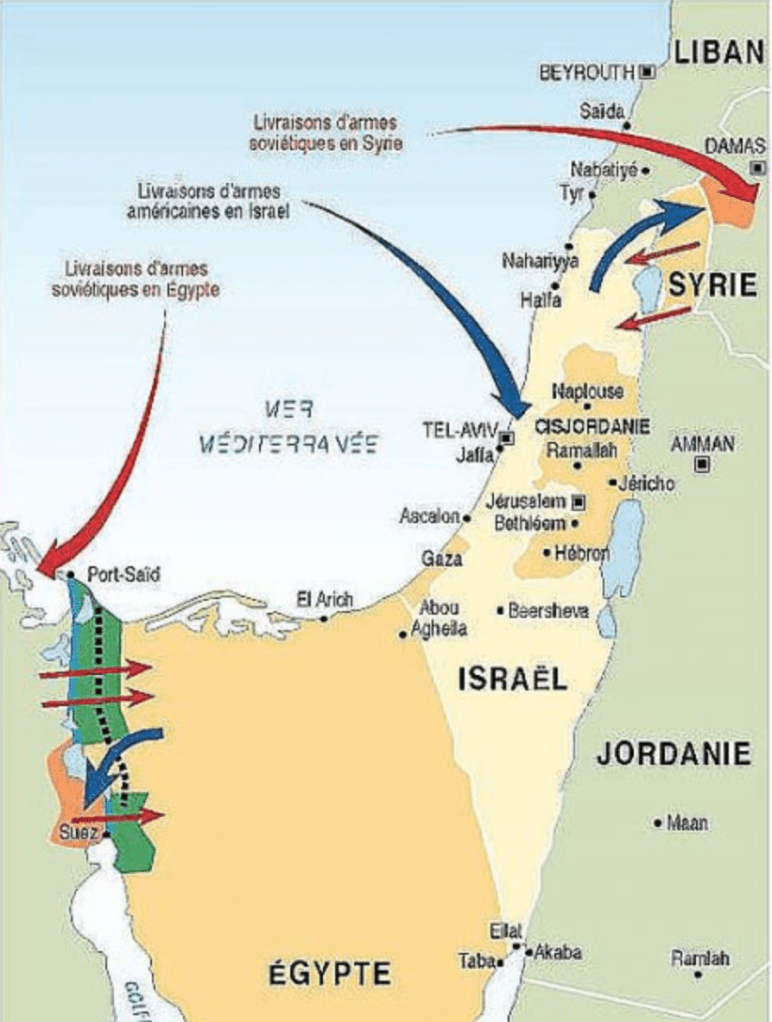

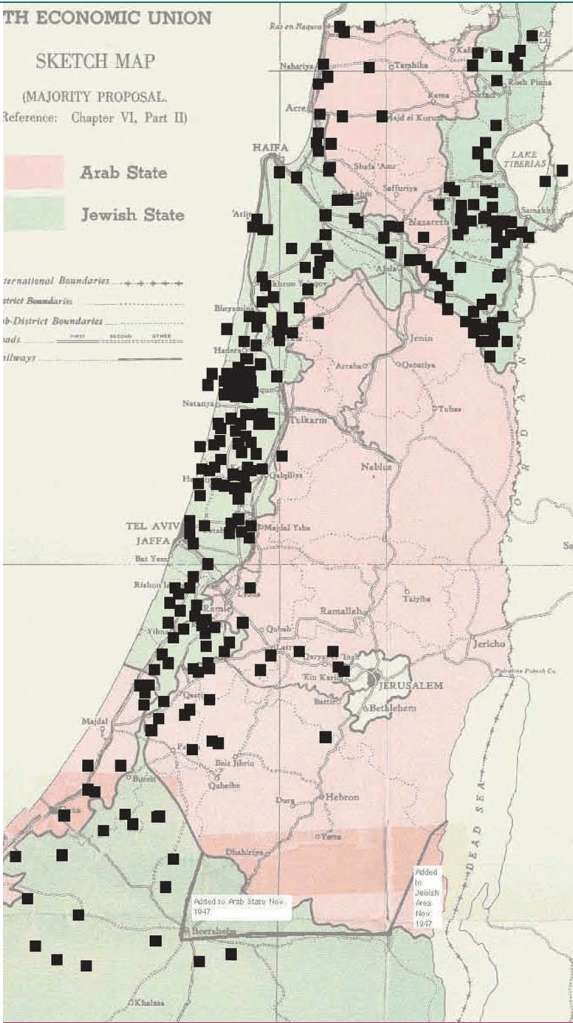

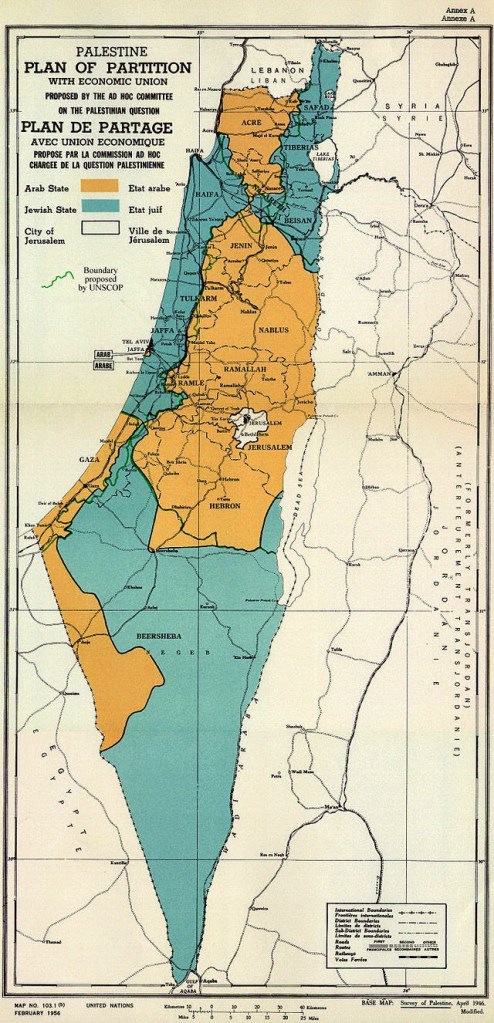

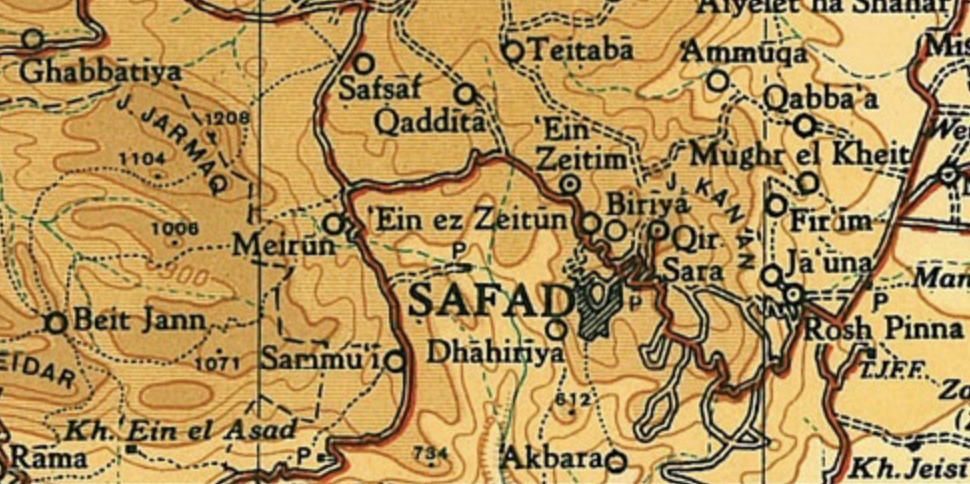

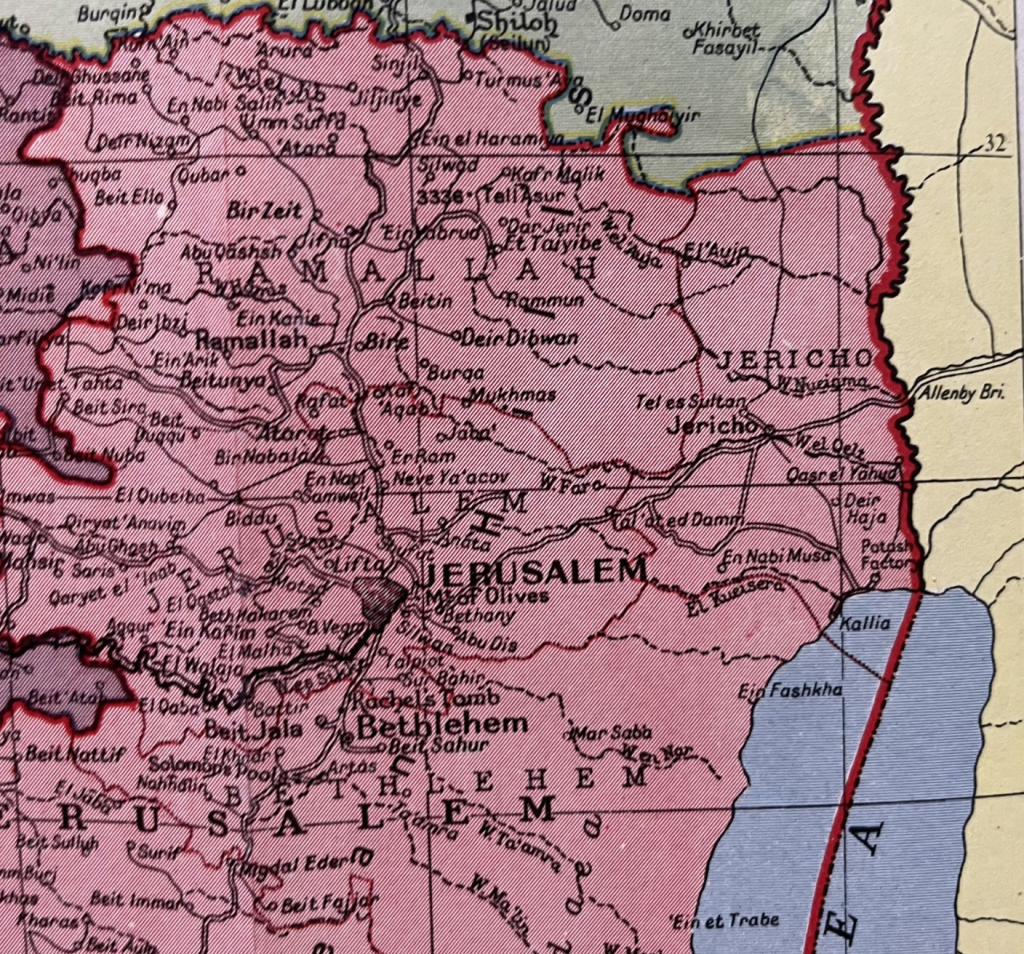

Despite the global revulsion at the killing of civilians, forced migrations, and violent atrocities, it is so difficult to process for the violence of suffering we may forget the tactical role maps of supposed peace “solutions” played preceding these struggles–and indeed how “remapping” the Middle East to defuse its conflict only served to sanction or endorse an unprecedented explosion of violence. Did the maps that the Trump White House created, assisted by the Office of the Geographer in the U.S. State Department, help to sanction a ground plan to drivePalestinians from Israel’s borders?The cartographic framework that President Trump deceptively promoted in his first Presidential term as a “Deal of the Century” was boasted to be a gift to the Middle East remade the borders and normalized the rebordering of Israel in quite violent ways. The consolidation of expansive borders was done quite aggressively-by invoking far-right Israeli ideas of territoriality of scriptural precedent removed from the ground, rooted in myth more than precedent. Trump bombastically magnified a “deal” that was of course both one-sided and deceptive, not a treaty or process of negotiation, and perhaps never really or truly on the table; it demanded few sacrifices if any from Israel even as it promised it was an end of sectarian violence.

The rather crude maps not based on GPS and drawn on paper napkins that came out of the Trump White House however became a basis for a “deal” in the Middle East gained a tactical role as Trump positioned himself as master of the “art of the deal” able to bring peace to the Middle East, born of a transactional logic of personal negotiations. The improbable prominence of Jared Kushner as alleged architect of a new “peace plan” long elusive to previous American administrations balanced a promised port, access to the River Jordan, and a cut-out boundaries as a viable future for the State of Israel, constraining Palestinians to islands of green. The “Plan,” as it was known, was never taken that seriously, if promoted as a once-in-a-lifetime “Deal of the Century, was drafted with no input from Palestinians, and ignoring all stated desires, but offering several carrots in mistaken hopes to end diplomatic stalemate to restrict Palestinians to a reduced presence in the new State of Israel. If President Trump is best known perhaps for his dictum that a state without clear boundaries is not a state, the Palestinian population would not be in defensible boundaries, or any boundaries, but linked by a set of bridges, tunnels, roads, and islands, without coherence in this “visionary” plan.

President Trump remained oblivious he hadn’t addressed the situation in a meaningful way: “All prior [American] administrations have failed from President Lyndon Johnson,” he said beside Netanyahu in 2020, “but I was not elected to do small things or shy away from big problems.” Netanyahu was overjoyed at a man he praised as “the first world leader to recognize Israel’s sovereignty over areas that are vital to our security and central to our heritage”–obfuscating words about the protection of a barrier of security in Israel’s bordering with Palestinian populations, and offering no “right of return” for Palestinians expelled from ancestral homes in Israeli territory, and offering Israel “access roads” across and between Palestinian enclaves.

The hope that if extending Israeli sovereignty “to Judea and Samaria” would anger the Palestinians, all bets were that the Palestinian Authority would in the end “maintain a certain level of security cooperation with Israel to prevent the strengthening of Hamas–as if the calculation of according Israeli sovereignty would be a step toward “peace” ensuring “dignity, self-security, and national pride,” offering a prosperity that could be fashioned out of whole cloth and promises of independent economic wealth.

“Trump” Peace Plan for Middle East, 2020

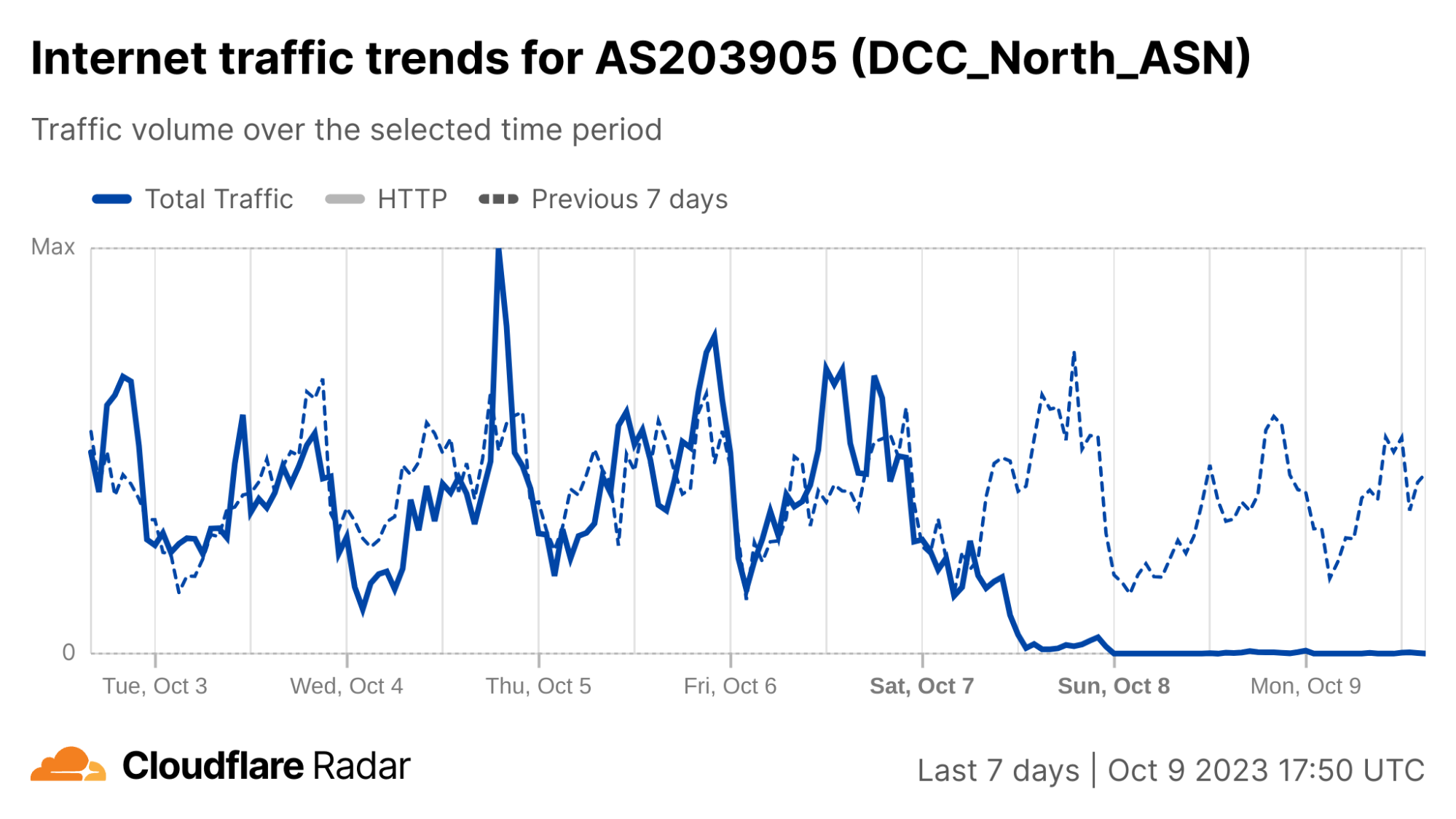

Since then, despite–or perhaps because of–the incomprehensible scale of tragedy and violence in Gaza and much of the Middle East, we have continued to consume our information by infographics and maps by territorial maps that foreground borders, as if this was a geopolitical dispute about territory, in ways that ignore how these are a new war of bordering–and often mythic borders, as much borders that can be mapped or reflect the situation on the ground, as if legal precedents–and how far we have come from a war that new borders might resolve. The very maps we use to help process attacks that are cut as border-fighting often destabilize the viewer’s perspective on the Middle East, distrusting Israeli politics, and the tactical goals of the Israeli army–and rightly so.

And although Kamala Harris has refused to distance herself from the War in Gaza, and affirmed the policy of providing support for Israel, even as the United States has little apparent leverage to shape Israeli aggression, despite her empathy for Palestinians, the endorsement of robust military action of Israel to defend its borders, and to attack trans-border threats, not only to vilify and condemn all anti-war protest with antisemitism, as part of a transnational “Hamas Support Network,” by the President who authorized annexation of the West Bank, endorse the annexation of the Golan Heights, and relocate the United States embassy to Jerusalem–the strident pro-Israel branch of the Republicans Overseas promise to secure a remade the map of the Middle East with the active contribution of a new Republican President who proclaims himself “Israel’s Best Friend” will be far more ready to supply Netanyahu with arms to defend borders and offensive weapons rather than stop their flow. If globalization ensures every point in the world can be more immediately connected to any other than ever before, a President promising to encourage Israel defend its borders and “finish the job” of extermination in Gaza blurs America’s borders with the defense of Israel’s borders and a license for far more escalated violence. The readiness with which Netanyahu has praised Trump as a “savior” for Israel, amidst the increased violence on three fronts of war.

Tel Aviv, October 30, 2024/Avshalom Sassoni

Donald Trump’s vaunted promise to “make America great” was more closely tied to the role of the United States in Middle Eastern politics than has been acknowledged. Trump’s “Deal” replaced true negotiation with a set of illusory promises of economic benefits, investments, and technical know how. The offering of this “deal” was presented in patronizing terms, economic advantages and promises was all Trump offered to the Palestinians, a carrot of future investments. Could it be that the death of any two-state solution lay in the ultranationalist ideologies of Trump and Netanyahu, whose respective ultranationalist ideologies, for all their differences, invoked state boundaries with massive blind spots to the situation on the ground?

The promotion of the rights of an army of settles to expand a protective buffer or envelope for Israel, the hundred mile envelope Customs and Border Protection and the Border Patrol conducted warrantless searches from any “external boundary” of the United States strips innocent people of constitutional rights–limiting constitutional rights along the entire coastlines as well as southern border, allow new technologies of surveillance in a range of technologies as a militarization of the border. If the battery of surveillance technology lack geographical limits, the border zone expanded by settlers long militarized an expansive boundary of the Israeli state, in powerful cartographic genealogy of the demands for a “Greater Israel”–a concept that found surprising acceptance and endorsement from the very individuals Donald Trump would come to nominate for key roles in his cabinet upon winning the 2024 Presidential election, Pete Hegseth for the Department of Defense, who was proposed as a key negotiator in any future military deals with Israel, and Mike Huckabee, the former Arkansas Governor and Baptist minister reborn as political commentator as the next U.S. Ambassador to Israel, who has been long committed to establish Israeli sovereignty over Gaza, impressed by the “overwhelming spiritual reality of understanding that this is the land that God as given to the Jews” while hosting tours of srael hundreds of times since the 1980s–and arguing that the very concept of Palestinian Identity is not a valid concept of governance, but invoked only as “a political tool to try and force land away from Israel.” All this is well-known. But the circulation of this sentiment among American Baptists and evangelicals across the Atlantic to reinforce or grant currency to resurrect a zombie idea of Greater Israel in the current Middle East is beyond imperial, but is a symptom of globalization, if not a symptom of the “shallow state” enabled by drafting lines of polygons in crude overlays, as if toponymic tropes of biblical tropes respond to current crises.

The conceit of a Greater Israel, at the start of the twenty-first century, is a symptom of the confused legacies that were promoted by Donald Trump and Co. to give license to the expansion of military might over Gaza, as much as the alleged failure of the United States to intervene. Would the idea of intervention even seem possible, once the entertainment of the permission to expand Israel to the West Bank and the Mediterranean was floated in the first Trump Presidency in the maps that the Office of the Geographer at the U.S. Dept of State had given their imprimatur? The maps that were made by the United States, as much as displayed by Benjamin Netanyahu to the U.N. General Assembly, suggest the deep origins of the expansion of Israeli territory in perhaps the shallowest corner of the first Trump era, where the boundaries of Israel were tacitly expanded and the two-state solution taken off the table as a desideratum. The pro-settlement ideology Huckabee has openly espoused and literally preached rests on the belief that expulsion of all self-identified Palestinians from the biblical bounds of Israel is part of a preordained divine plan for Christ’s return, opposing any two-state solution–at least, “not on the same piece of real estate.” The old conceit of “sovereignty over Judea and Samaria,” regions that did not exist on earlier maps of the Middle East, is presented as a decision “for Israel to make,” even if they were not named in any recent maps of the region, as the future Ambassador described himself as “very pleased that [Donald Trump’s] policies have been the most pro-Israel policies of any President in my lifetime.”

President Trump Announcing Comprehensive Settlement Between Israel and the Palestinian People, January 29, 2020

The genealogy of these “pro-Israel” ideas rests on a reconstruction of a longtime US-Israel alliance in the optics of the rise of apocalyptic rhetoric far different from the afterlife that the Cold War granted Imperialist ideas. (The central crux of an oxymoronic credo of “Christian Zionism” denies blame or agency for the killing of Palestinians in the Gaza War, and whitewashing of Likud regime policy with Christian millennialism.). It is also less of a “vision forward” than resting on the recycling of some of the most toxic concepts of nationhood that demand to be fully examined to be understood. Although Huckabee has claimed that Trump will assemble a “pro-Israel dream team” to ensure that nothing like the bloody massacres of civilians in the invasion of Israel on October 7, 2023 will ever occur, the notion of turning the page on October 7 seems designed to demonize the Palestinian slogan, “From the River to the Sea” to an excuse to obliterator the legacy of Palestinian presence from the map–and to assert, as Huckabee claims, that the legitimacy of biblical terms “like ‘Promised Land,’ and ‘Judea and Samaria'” hold the significance “that live from time immemorial,” a nomenclature that the United States has had no small part in perpetuating.

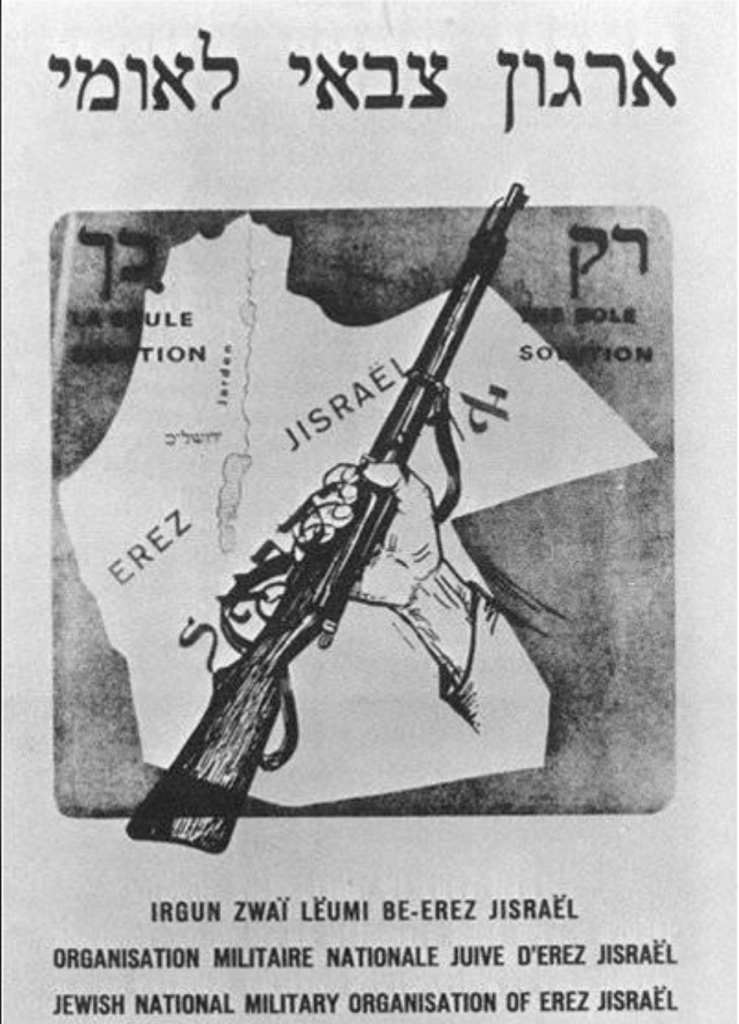

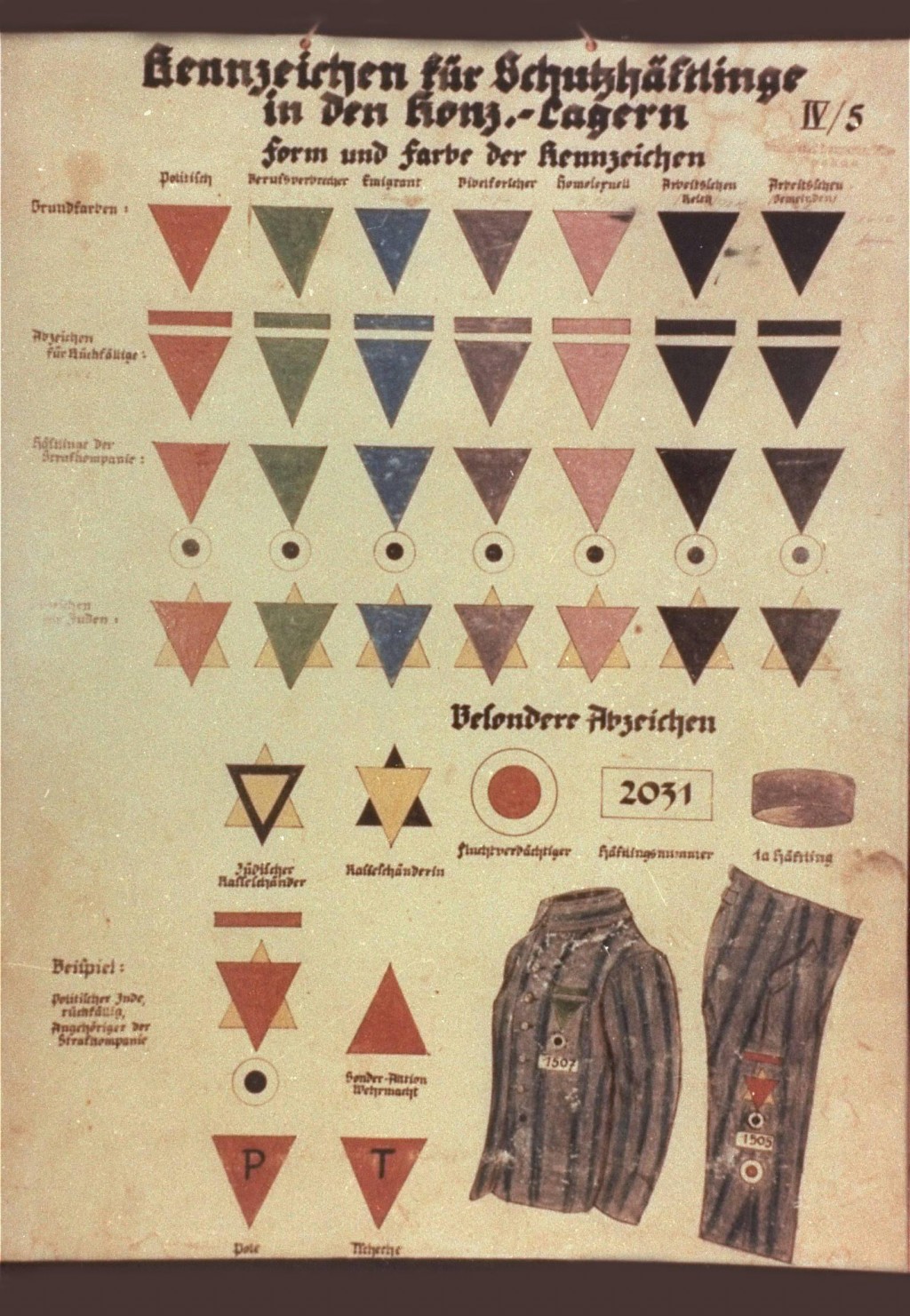

The castrophic events foretold in the Book of Revelations were not close to the ideas of right-wing Zionists who affirmed the boundaries of a “Greater Israel” as the historic borders of a sovereign state. Promoting expansionist vision of territorial maximalism of a Jewish state beyond the boundaries of a Palestinian Mandate, and across the River Jordan, of biblical derivation, was first championed by the Right Wing Zionism before the state of Israel was founded, informing the current demands to annex lands beyond mapped borders, if they now neatly dovetail with demands for security and with evangelist eschatology. Expanding the current boundaries of Israel in the ultranationalist vision of a greater Eretz Yisrael beyond ends of security, power, and reflected in the affirming state boundaries in Israel? The ultra-nationalist vision of far-right supporters of a fixed protective barrier securing a frontier meshed with the resurrection of the map of an expansive Greateer Israel advertised “The Only Solution”–the sole solution–years after the Final Solution imagined the idea of a world without Jews set sights on a Greater Israel–

Irgun Poster from the Military Organization of Eretz Israel, beyond Palestine Mandate

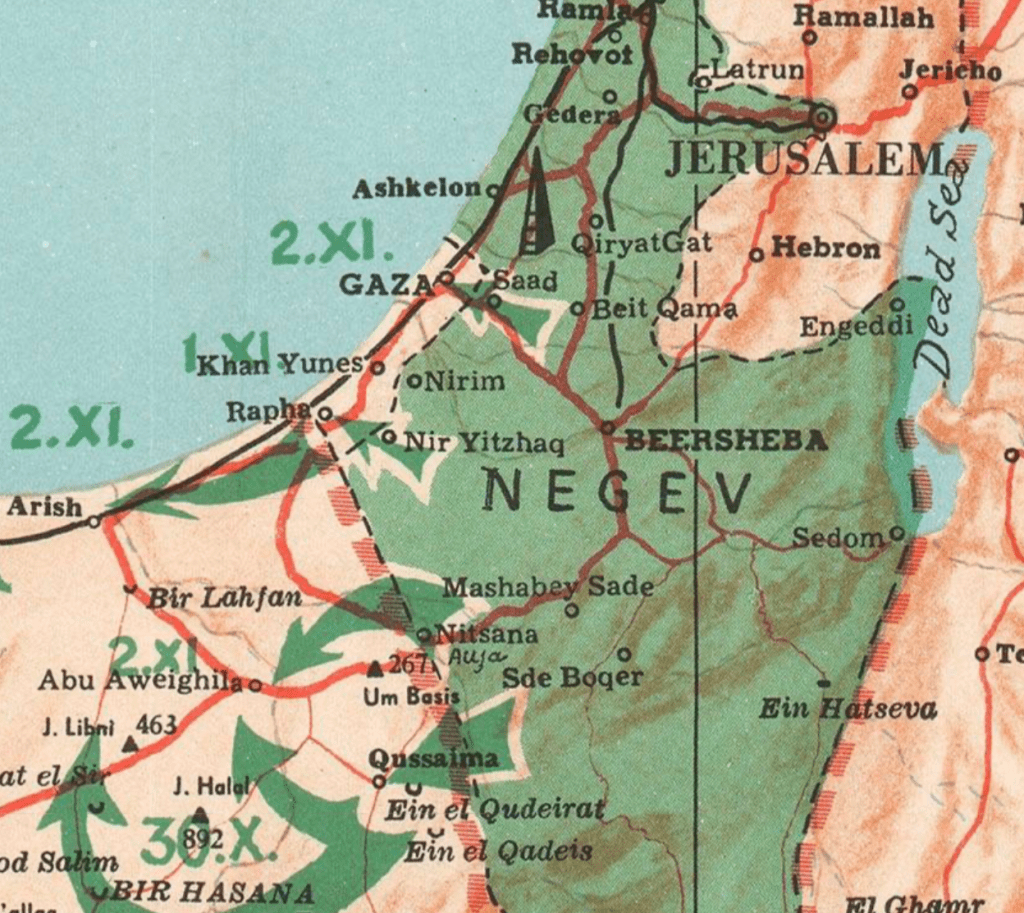

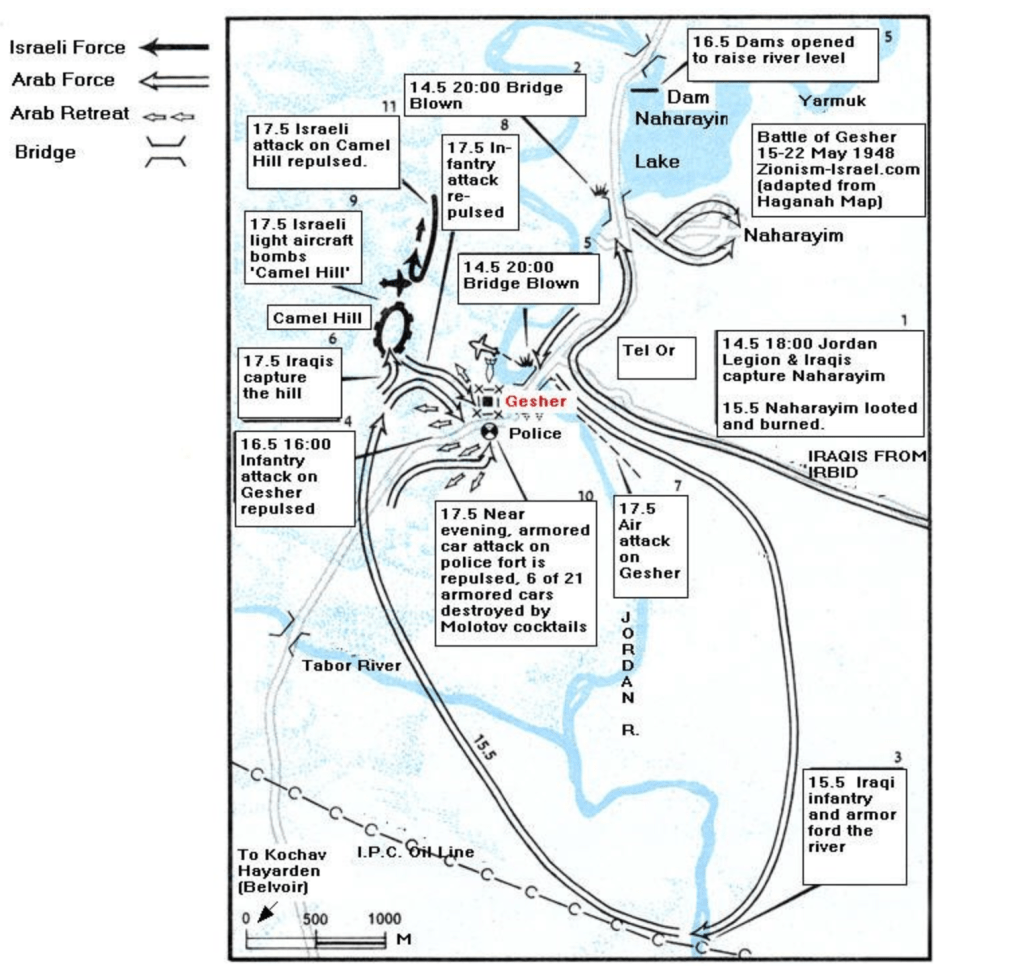

–whose decisiveness underlay the cartographic genealogies of ultranationalist thought from the time former Irgun like Menachem Begin entered Israel’s government, advancing advancing gradual annexation by settlers of “lost” lands. The map produced in Central Europe in the post-war period of the 1940s set a territorial goal. If the constitutional silence on territorial borders in Israel’s constitution is invoked as berth preserving the vision of “Greater Israel” in Israeli politics, the ultranationalist ideology of America First ideology invokes an expansive border as a site for federal law enforcement of a “virtual border fence” of Border Patrol’s federal mandate has compromised individual liberties in Donald Trump’s vision of the United States in the Trump era, Likud nourished outwardly expansive borders, as if resurrecting a zombie idea from the dead, but one of deep biblical resonance with the land granted Abraham’s children “from the brook of Egypt to the Euphrates,” accomodating the territorial given to the children of Abraham and Israel over generations to the new language of nations.

For this map–that places Palestine beyond the borders of Israel, in Lebanon, Jordan, and an “Arab Palestine” to the south of “Eretz Israel” of bright blue hue, that encompasses in its midst the biblical territory of Jerusalem, and the Jordan River, and assumes an almost cloak-like form, in a land map recalls modernist abstract expressionism argues that lands promised to the children of Israel when they left Egypt in Exodus or Deuteronomy offers a template to a modern Israeli state–“two banks the [River] Jordan has./One belongs to us; the other does as well,” read lyrics at its base, redrawing state borders already being negotiated in interwar years.

Greater Israeli from the Nile to the Euphrates, 1947

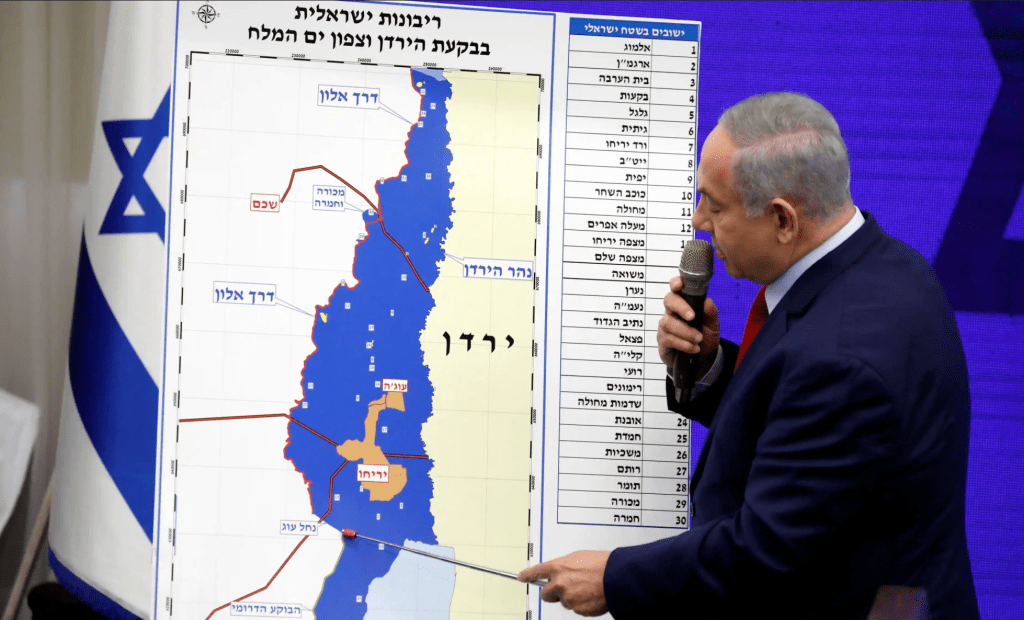

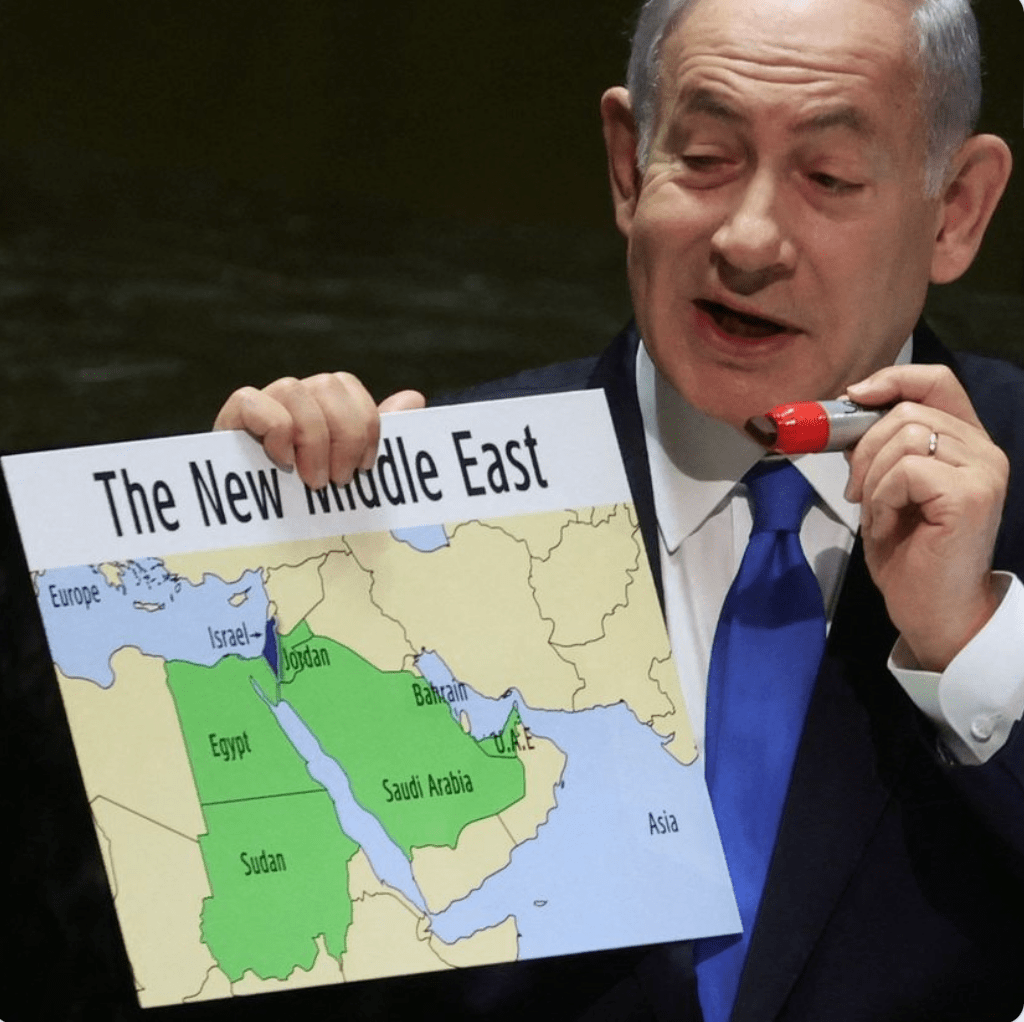

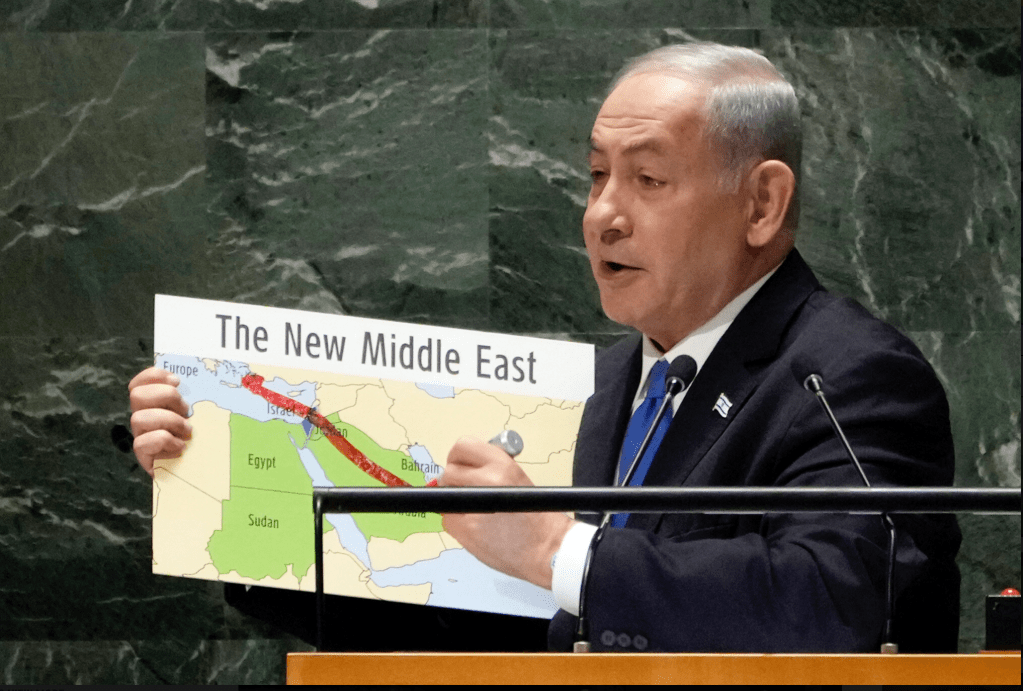

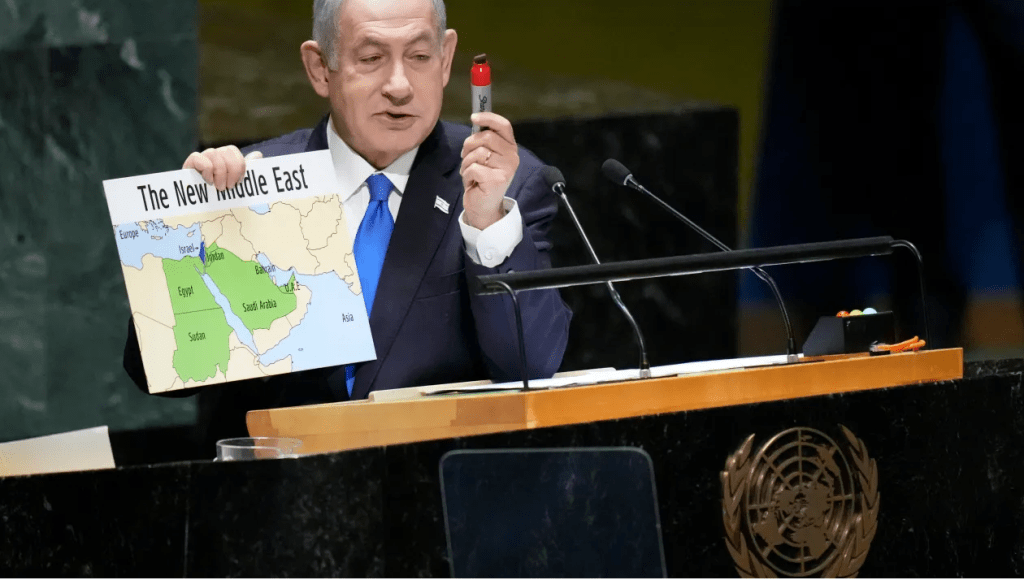

Which returns us to the telling erasure of a Palestine on the River Jordan’s left bank in the map that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Begin’s heir, brought to the United Nations’ General Assembly to make his case While the Democratic presidency is faulted for pursuing a “deal” rather than supporting the future rights of a Palestinian state to exist, there is a stunning amnesia of the promotion of the language of a “deal” in the maps designed and issued in the architect of the Art of the Deal, who set the terms for a “deal” that would given Palestinian territoriality, delimit Palestinian rights, and offer an upper hand to the Israeli state. President Trump’s vaunted “Deal of the Century“ has perhaps been overshadowed by the violence of war, but is a “deal” for which we can find ample fingerprints–and indeed a famous scrawled signature!–among paper maps not only props of statecraft, but frameworks with power to re-shape Middle Eastern politics on the ground. These are maps that echo ultranationalist demands, and echo the forms of ultranationalism that became platforms he articulated in his first Presidential campaign.

As props, these maps–in tiresome ways–demand to be traced as symptoms of the personalization of the political, and indeed the entrenchment of the United States in projects of remapping the Middle East, as much as personalized as a “love affair” between Netanyahu and maps, as Middle East Eye has with accuracy recently observed, noting the “history of using controversial maps” in public presentations to international bodies and the Israeli press, while not fully underlining the personal sanction that the cartographic gifts from President Trump provided Israel’s Prime Minister both to promote his vision of Israel to the world, but a platform to rehabilitate Netanyahu’s political career.

The oddly vivd green-hued map all but eliminated Palestine from the Middle East. The blue island of Israel placed “Palestine” in vivid green nations mapped as Palestinians’ actual homes: “Egypt,” where potentially over 270,000 Palestinians live, Jordan, home to 3.24 million Palestinians, and Saudi Arabia, home to a community of 750,000, and quite vocal as to Palestinian sovereignty–as well s Bahrain, where pro-Palestinian advocacy has been intense among its pluralistic population and Sunni Arabs among the most influential groups–and Sudan, where many Palestinians reside.

The color scheme of the political lay of the land erases Palestinians, perhaps, in a bright blue Israel which lies like a mosaic amidst the clear borders of nations. But the coloration of the political lay of the land is slippery. Such vivid green, long a color symbolizing allegiance to the cousin of the Great Prophet, Ali, gained status since the prophet’s lifetime as a the important color in Islam and the green spirit, Al Khader, and a sign of the vitality of Islam alive from the rich cultural Fatimid era up until the arrival of western crusaders. Netanyahu rose to political prominence, by no coincidence, amidst this improvised patriotic flag-waving in the occupied territories when flying the flag’s colors was forbidden in Gaza, the West Bank, or Golan Heights by Israeli law–provoking the improvised creative display of its colors in laundry hanging outside windows of private residences. If the same flag led the watermelon to become a symbol of resistance, combining the four colors of the flag, the red marker that Netanyahu used before the United Nations to draw a “trade corridor” across an Israel straddling the Mediterranean Sea to River Jordan “map” Palestine outside of Israel’s borders.

Netanayu and ‘The New Middle East’ at 78th session of United Nations General Assembly/September 22 2023 AP/Richard Drew

The vivid light green color of “The New Middle East” that Netanyahu crossed with a red marker was no longer needed to be a theater of war, but could be transformed to one of economic vitality, as if coopting the “green fields” in Safi al-Din al-Hali’s verses Arab nationalists first coopted in the early twentieth century and by 1947 Ba’athists and members of the Arab League took as the national flag of Palestinian people–“White are our deeds, black are our battles,/Green are our fields, red are our swords.” Netanyahu wanted to place these fields securely behind the borders of Jordan, Bahrain, Egypt, and Sudan, not in Israel that lay on a channel of trade to Europe. This quite rebarbative map–as others that Netanyahu brought to the General Assembly of the United Nations from around 2018, and the maps he continued to display through 2023, as if to make the case Israel demanded to be seen as a “normal nation” among nations. But increasingly it may indeed seem to conceal it is not–indeed, Palestinian residents in Israel are not deserving of any clear political role in the New Middle East.

Netanyahu Addresses General Assembly from UNGA Lectern September 22, 2023/AP/Mary Altaffer

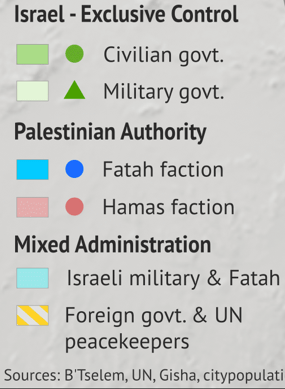

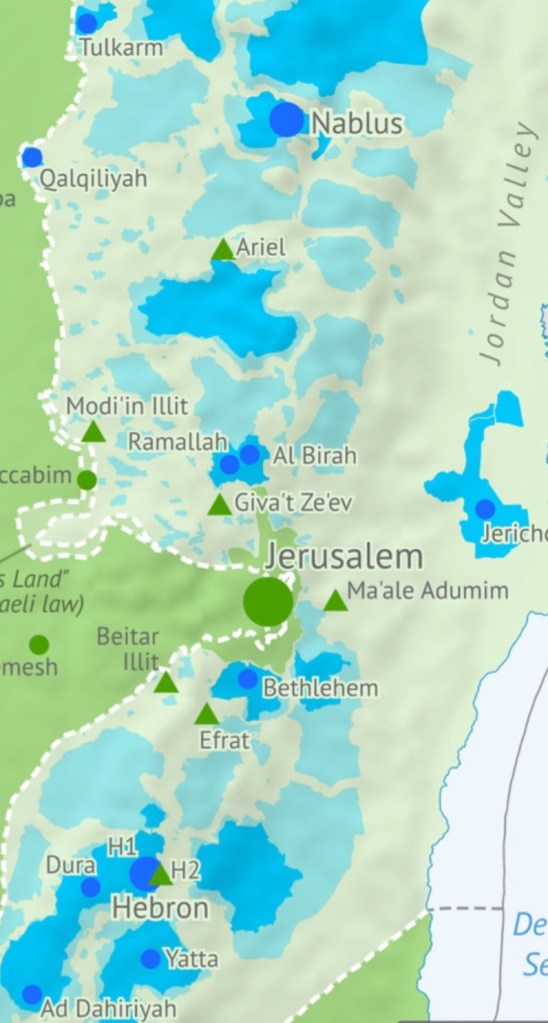

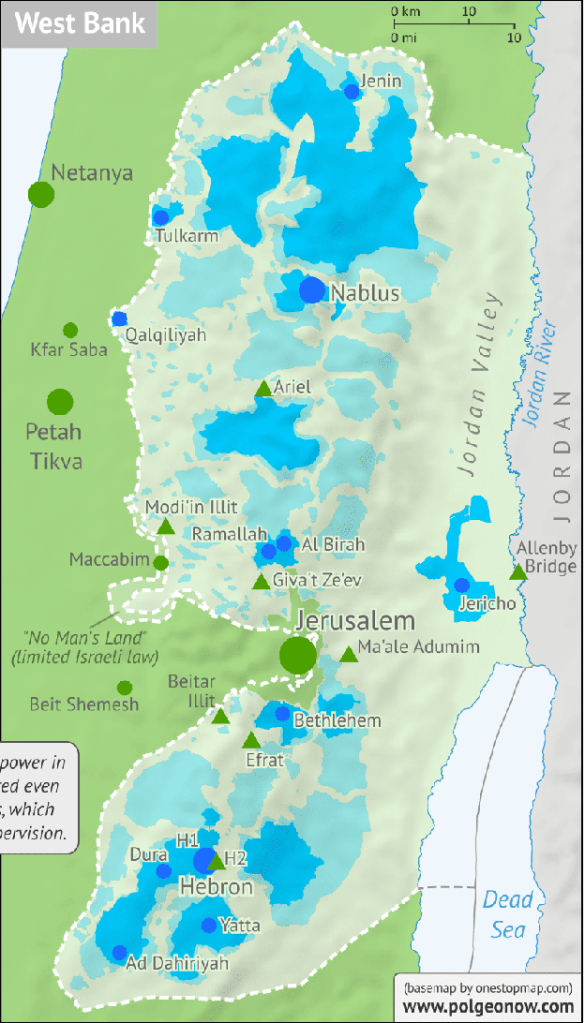

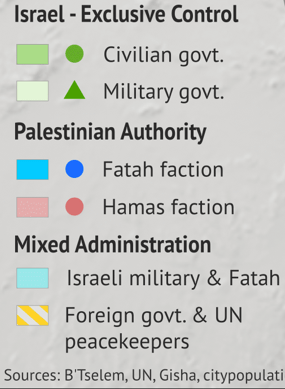

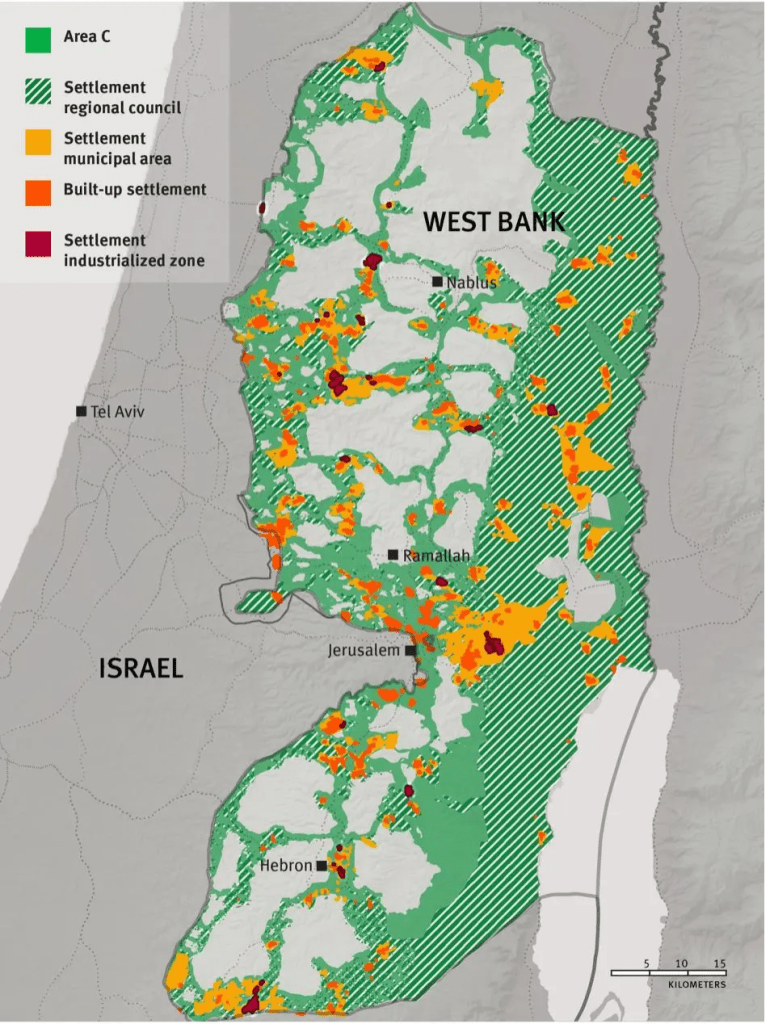

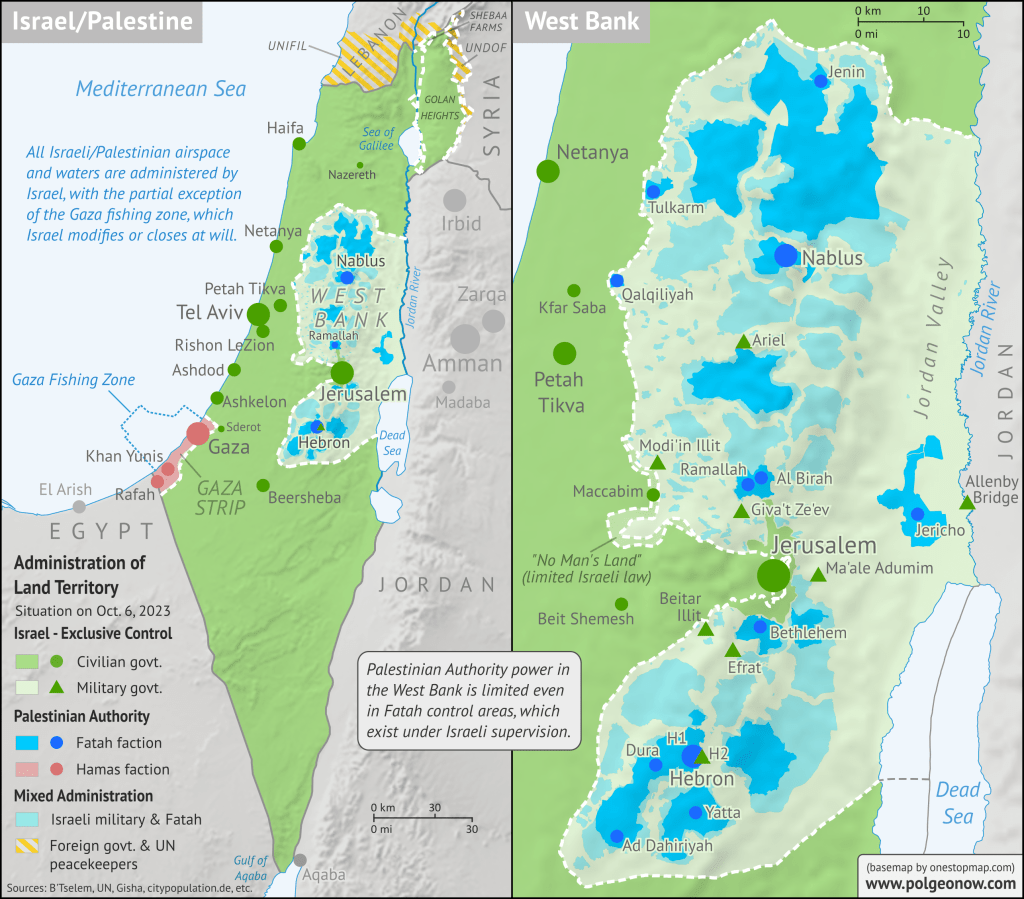

The geopolitical situation as he spoke was extremely complex, but the presence of Palestine was masked in mapping Israel by a blue island by the River Jordan held before the General Assembly, in ways oddly incongruous with the image of global peace on the lectern from which he spoke. The map clearly showed a West Bank and Gaza under Israeli control, even though the situation on the ground as he spoke was one of fragmentary political control by both Hamas in Gaza and Fatah in the Jordan Valley, largely subject to the “supervision” of Israel’s government. The complex administration of the areas of Fatah control in the West Bank and Jordan Valley contrast to muted blue areas jointly administered by Fatah and the Israeli military, and a light green sea of Israeli military control surrounding the lands of settlers in the Jordan Valley If the blue regions were subject to joint administration by Fatah and the Israeli army, light green showing areas of Israeli military control, rather than administration by a civil government, the airspace of the entire region was administered by Israel, but the entire region not controlled by any means by an Israeli state.

Evan Centanni, Administration of Land October 6, 2023,/reproduced by permission of Political Geography Now. Sources: B’Tselem, UN, Gisha, city population.de

Why was such a mixed administration around areas of Fatah control masked before the General Assembly? Was this intended to normalize the Israeli control over a mythic “Greater Israel” or was it just a map? The map Netanyahu held proudly of The New Middle East as if teaching a class without familiarity with world affairs. It was a sort of magic trick as much as informative, and masked actual bounds. It successfully concealed the violence of apartheid relations, on the one hand, and erased historical Palestinian demands, simplifying history immediately raised eyebrows by rendering a “New Middle East.” The map that the Prime Minister brought to New York while his generals planned the invasion of Lebanon was reflecting back at Americans a recognizable coinage of then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who in late July 2006 had vouched during an earlier invasion of Lebanon with American arms–and just before the United States invasion of Iraq–the bombing campaign focussed on freeing Lebanon of Hezbollah that targeted terrorists with unprecedented force marked “the birth pangs of a New Middle East” able to accelerate a “freedom and democracy agenda,” rather than one of dislocation and destabilization. Secretary Rice had promised a “domino democratization” across the Middle East would result from assisting these “birth pangs” by “pushing forward to the new Middle East, not going back to the old one.”

Secretary Rice invoked the groundless discredited rhetoric of “dominoes,” not as about to fall to communism but as an extension of a “green revolution” in Arab states that would alter the geopolitics of the Middle East in definitive ways to the benefits of Americans. Armed with these persuasive tools, Rice cast extirpating Hezbollah not as violence but as a “moment of opportunity,” advocating the chance to intervene decisively to remap the geopolitical center in the Middle East among Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia during the war between Israel and Hezbollah–in place of the “old Arab center,” and leaving the question of the future of Palestine off of the political map, remapping the Middle East from afar for American eyes. Indeed, the affirmation of Jerusalem, a divided city with a large Palestinian presence in the East, which Israel considers critical to its territorial integrity as a capital, was surrounded by light green territory under Israeli military jurisdiction, beside a mosaic of light blue regions jointly administered by the army and Fatah.

Territorial Administration around Jerusalem, August 2023/Evan Centanni, detail of above

In ways that obscured this complex balance of shared authority and jurisdiction, the map of “the New Middle East” Netanyahu presented was not a return to the rhetoric of George W. Bush, but refracted through the hardball politics of redrawing of boundaries encouraged by Donald Trump. Was not the map of Jordan, Bahrain, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia but an updated version of that hope? Netanyahu may have implicitly told the United Nations that Israel, extending from the Mediterranean waters to the River Jordan, was already surrounded by states of Palestinian populations–that Palestinians, in other words, who often designated themselves by light green, had “their” states already. The Palestinian flag of white, green, and red, prominently included green to designate the survival of nationhood of which medieval poet Safi al-Din al-H’ly rendered an icon of three colors–“White are our deeds, black the fields of battle, our pastures are green, but our swords are red with the blood of our enemy.”

The tricolor was proscribed from flying in Palestinian lands– Gaza, the West Bank, and Golan Heights–for the generation,1967-1993, as Netanyahu rose to political power in Likud; the cartographic symbology seemed coopted in the map Netanyahu conspicuously displayed at the United Nations, placing Palestinian pastures beyond Israel’s borders. In the “New Middle East,” Israel possessed the Golan Heights and lands of the West Bank, the reduced Greater Israel is far more limited scope than Jabotinsky’s vision, but integrated in a community of nations–imagining a new “security envelope” that expanded Israel’s territoriality to the West Bank.

Map of “The New Middle East” Netanyahu Prominently Displayed to Address General Assembly Sept. 22, 2023/ Spencer Platt/AP

The Israeli Prime Minister was using the map to demonstrate a world view, more than a regional map. No map is all-seeing, objective, or all-knowing, but maps shape reality as knowledge-making systems: the powerful map green seemed to illustrate an Israeli state surrounded by the Palestinians with which Israel could live. The security of such secure bounds was a creation of the Trump presidency, but we may have forgot how keenly Trump fed that new map of the Middle East to Netanyahu in transactional exchanges to maintain his political survival, navigate a future with far right-wing allies, and win a second term. A sort of “Dance of Death” had indeed emerged between this remapping and remaking of the Middle East in the Trump Presidency, that used maps to redefine reality, and indeed maps to redesign political boundaries from an increased removed from the ground. Yet the situation was quite different, PolGeo reminds us, on the ground.

Administration of West Bank October 6, 2023, Evan Centanni/used with kind permission of Political Geography

The map of a Greater Israel became a sacred icon for the new hardball politics of the Middle East parallel how Trump employed crude maps of the US-Mexico border maps to advance the populist politics of a nationalist movement. In the map Netanyahu used to address a mostly empty halls of the General Assembly in late September 2023, Lebanon was notably not marked as a nation. As the map showing the boundaries of Israel after the first Arab-Israeli War in 1948 Netanyahu displayed incorporated the West Bank, as if to erase history, the “New Middle East” resuscitated the ultranationalist vision of an Eretz Yisrael— a “Greater Israel” including the West Bank and Golan Heights. The “map” was in fact less a nation than a concept of a nation, but the ultra-nationalist older right wing Zionist conceit quashed any idea of negotiating about a Palestinian state.

The expanded territory of Israel symbolically expelled the 1.7 million Palestinian residents of Gaza–before the October 7 invasion, retaking the ancient “territories” of Judea and Samaria, west of Jerusalem, to use the scriptural place-names of ancient biblical Kingdoms–as if those were the true territories the nation of Israel was historically destined to include. Entrusting an army of settlers to annex over future generations lands claimed as lying within Israeli territory seems to naturalize a territoriality by a map of transhistorical verities, rather than of political process or human rights.

“The New Middle East” Netanyahu Displayed at U.N. General Assembly on September 22, 2023, detail

Netanyahu’s notorious use of maps noting “military control” of Gaza’s borders by Israeli forces, like the these maps that extended Israeli territory to the West Bank, make offensive arguments of silence by erasure. They offer templates for failing to recognize Palestinian presence. If Zionist groups had earlier at times claimed the Transjordan, or historical Mandate, to imagine an expansive ‘Greater Israel”, the Likud Party set its sights on settling the West Bank, and even resettling a Greater Israel that included the Gaza Strip and Golan Heights–a far right conceit that extended beyond Israeli borders to the Transjordan and Sinai Peninsula, its capital in an undivided Jerusalem. As much as geopolitical intentions were ascribed to Israel of territorial ambitions to settle the region from the Nile to Euphrates, little different from how the Israeli flag was allegedly interpreted by leaders of Hamas as the “map” of a region extending from the Nile to Euphrates that included Jerusalem at its center, as claiming territory from the Mediterranean to the Jordan.

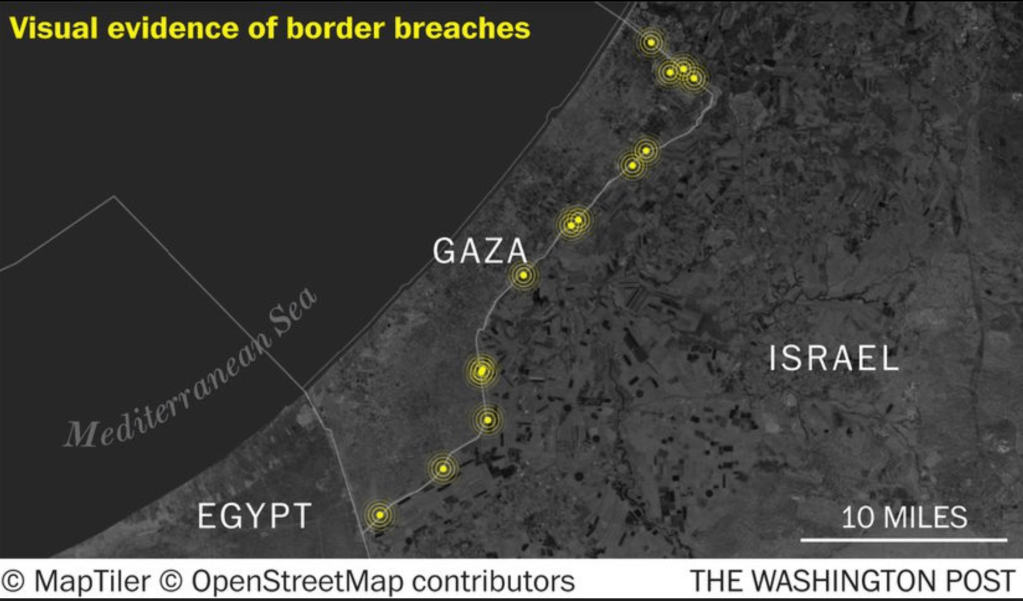

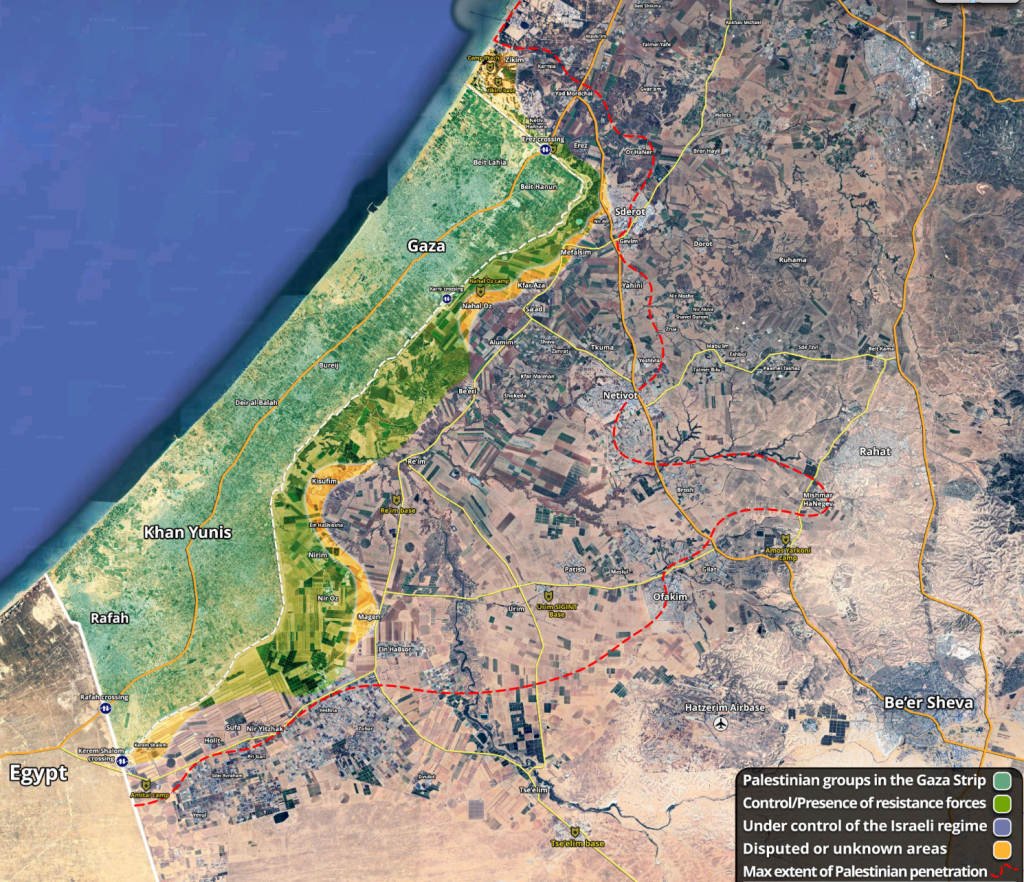

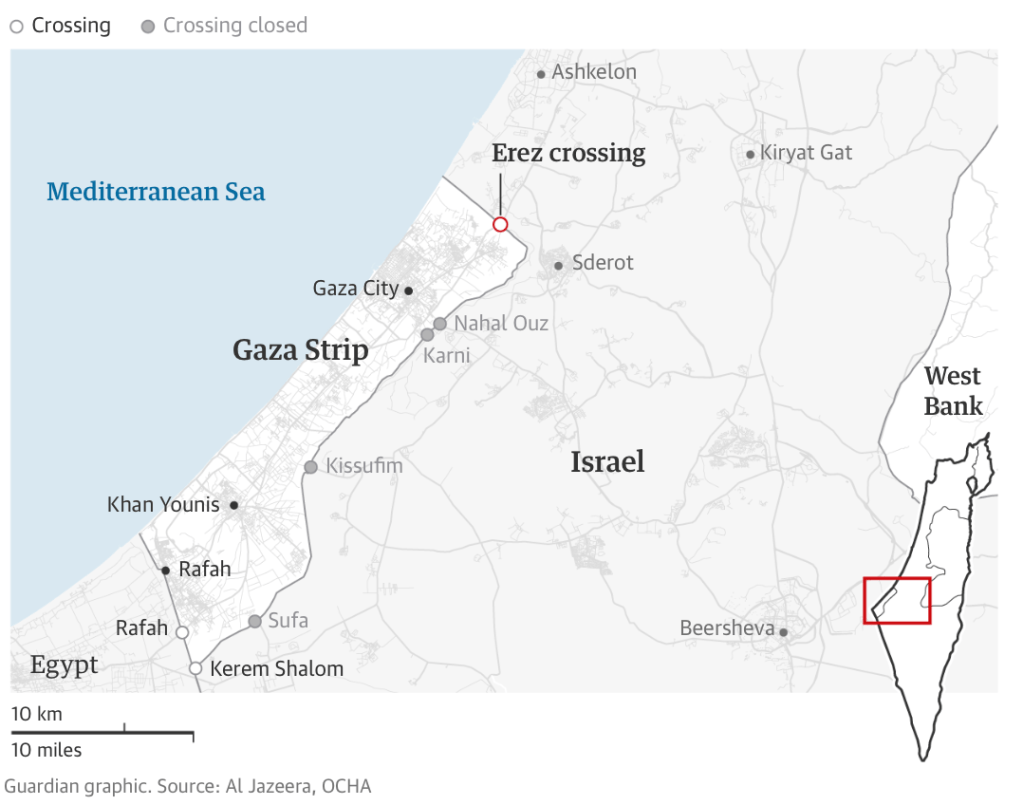

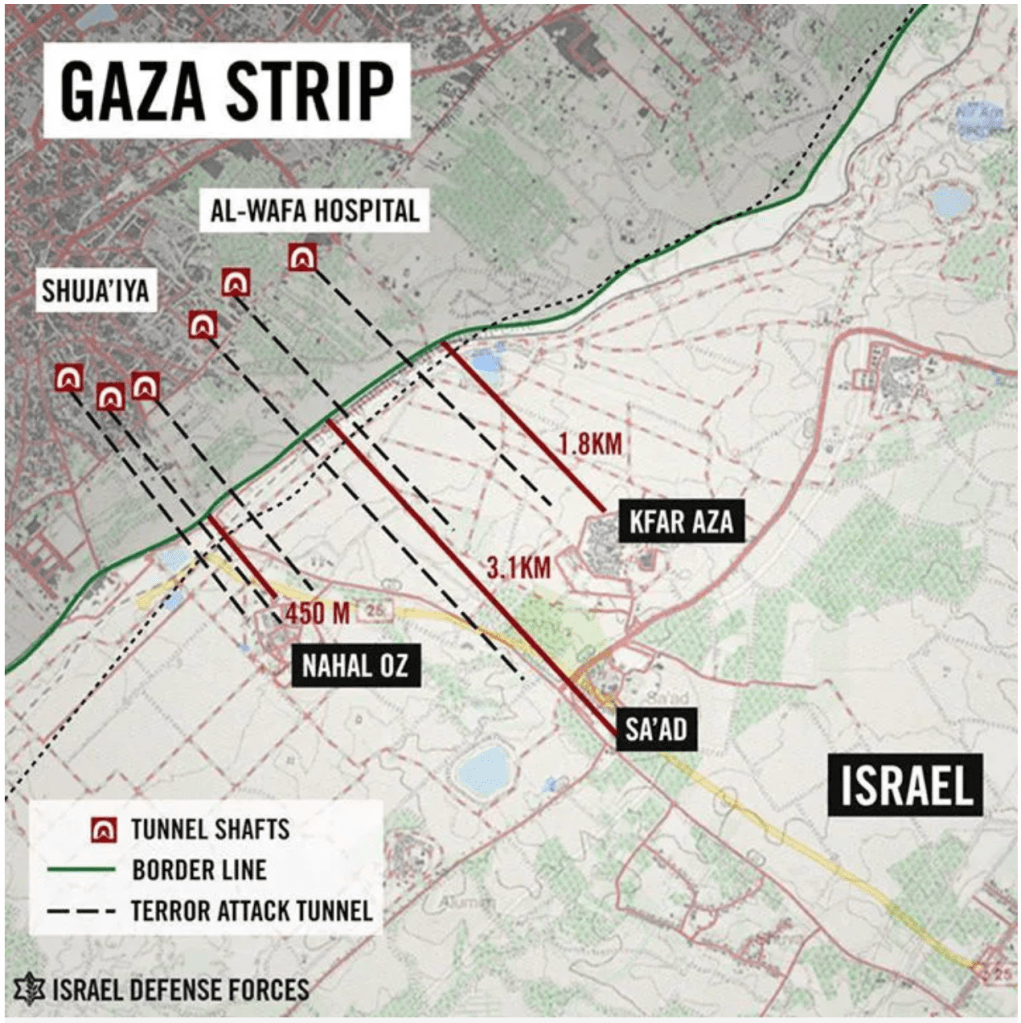

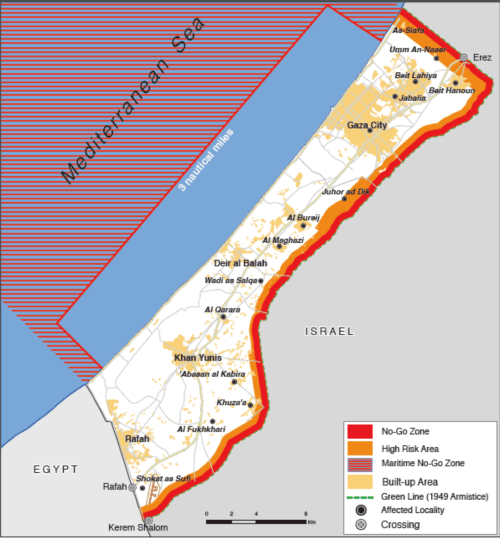

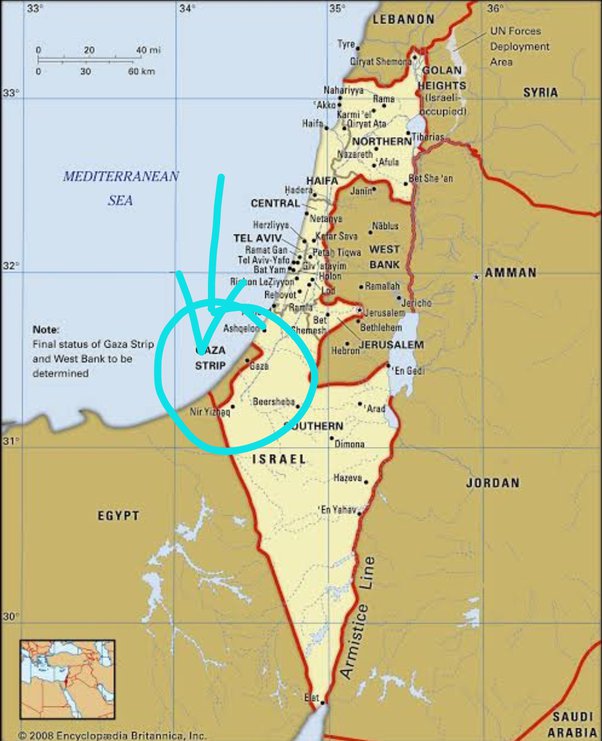

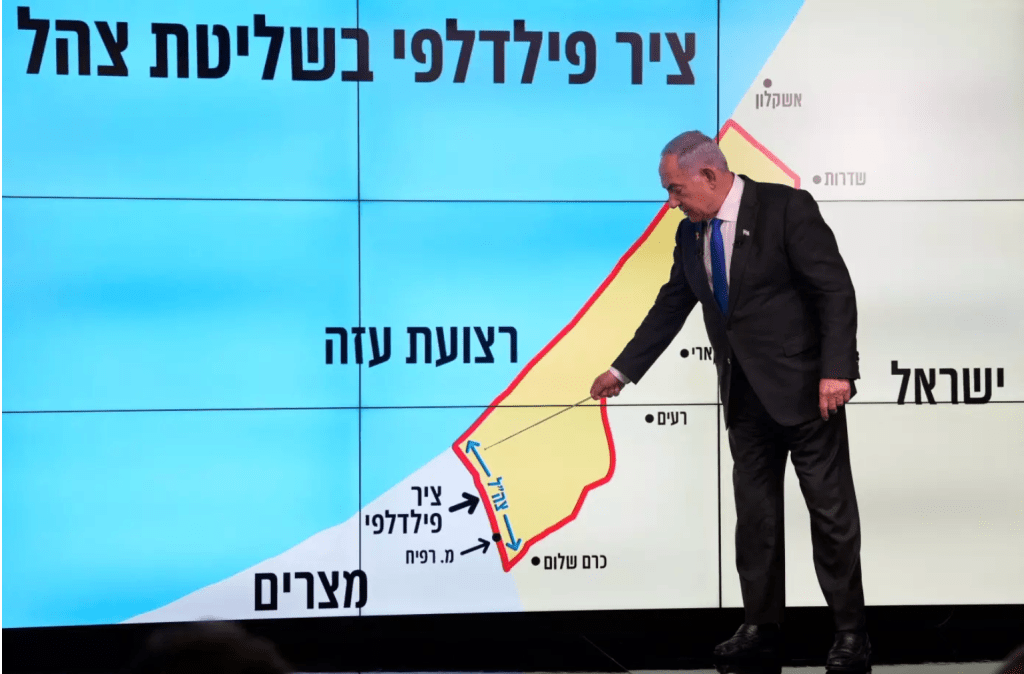

The actual proposals for securitized corridors around Gaza bounded Palestinians outside Greater Israel, after the armed reprisals for Hamas’ invasion of Israel, dismantling Hamas’ presence in the region and policing the boundary between Egypt and the Gaza Strip under Israeli control in future years, so that it is residents are entirely bordered and contained by Israeli military authorities. The demand to block what Israel treats as a dangerously transnational space–the very route by which arms, weapons, and bombs entered along the only remaining corridor of Gaza to the outside world–is cast as an objective of the Gaza War, demanding control of a narrow space lest it continue to provide “oxygen” for Hamas in the Gaza Strip., as if the border crossing Israelis have held since May provides a sort of tourniquet and security envelope for the future. Is the image of protective corridors not a Trumpist vision of space of a militarized border zone?

“Philadelphi Corridor under Israeli Military Control”/Ohad Zwigenberg (AP)/September 2, 2024

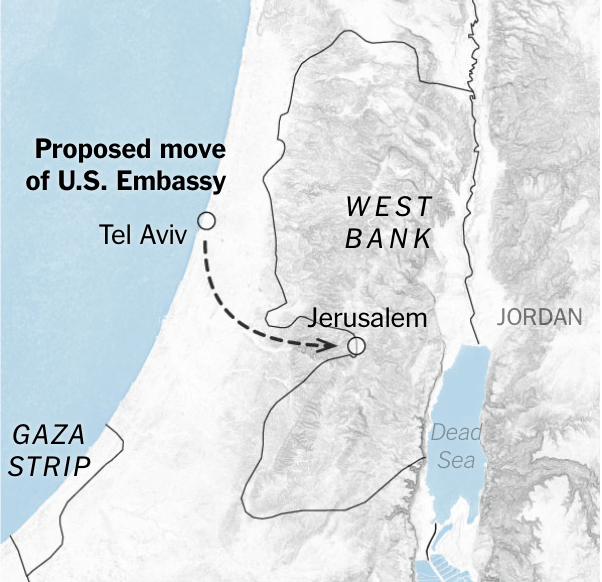

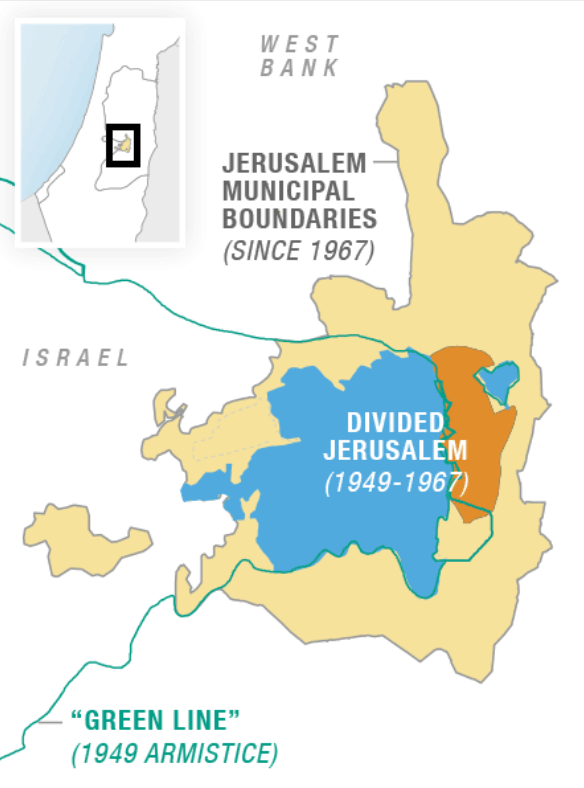

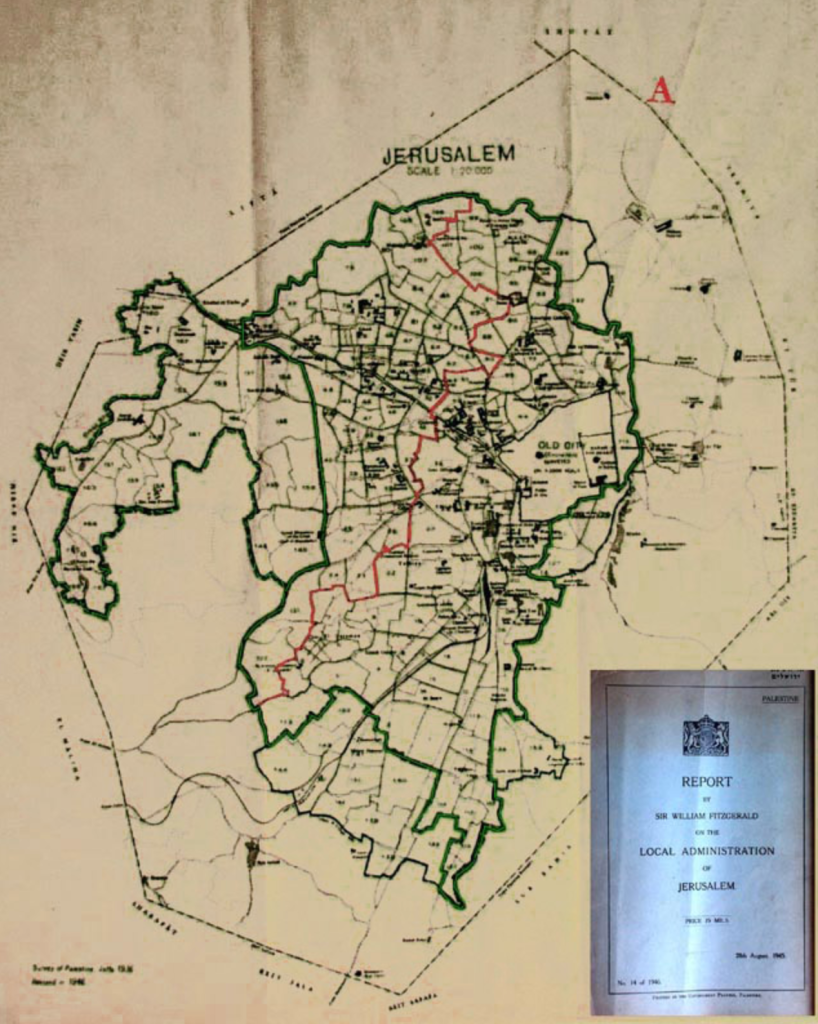

But the use of these maps to normalize aggression–perhaps even raising questions of a future Israeli settlement of Gaza that has recently emerged as a far-right agenda–provoke and enrage only since October 7, 2023. The truly mythic geography that placed Jerusalem at the center of a “Greater Israel” could not but include the mythic, biblical kingdoms of Judea and Samaria–not on any actual political maps, but nourished in ultra right-wing Zionist political rhetoric and increasingly close to platforms of Likud. The recognition of Jerusalem as a capital of Israel early in Trump’s presidency responded to an old demand that the divided city be recognized as a national capitol. In announcing a decision to place the American Embassy in Jerusalem from he White House had sent shock waves around the Middle East. For he seemed consciously to recognize and proclaim a new order of American foreign relations in 2017, by announcing in a news conference “Today we finally acknowledge the obvious: that Jerusalem is Israel’s capital” as “nothing more or less than a recognition of a reality.” But no map, of course, is ever merely a reflection; as much as a recognition, maps offer a shaping of reality.

The map that officially designated Jerusalem as Israel’s capital–long a demand of the Israeli state that American governments resisted–was an affront to allies across the Middle East, and remaking of decades of rather delicate foreign policy, opening fault lines between Palestinians and Israelis, and making the United States an outlier among nations–even as Trump deceptively cast it as “a long overdue step to advance the Peace Process,”– even as he recognized having rocked the international boat while appealing to “calm, . . . moderation, and for the voices of tolerance to prevail over the purveyors of hate.” By November 17, the United Nations, over American opposition, declared void any action by Israel to impose its laws, jurisdiction, and governance over Jerusalem as “illegal and therefore null,” invalidating all authority of the “occupying power” and demanding withdrawal from Occupied Territories. Netanyahu responded by the bluntly drawn borders of a counter-map.

American Shift of U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem, Lending Recognition to Israel’s Declared Capital City/NY Times

Who were the “purveyors of hate” but the Palestinian people? The maps that were provided by the Office of the Geographer of the United States of the future “State of Israel” in the Middle East curtail hopes for a Palestinian state, if not provide grounds for the disarming arrogance with which Israeli right-wing forces seem to have adopted an open policy refuting the right of Palestinian settlements or states as it situated the U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem, only recognized as the Israeli capital as President Trump single-handedly issued a Presidential proclamation in 2017, shortly after his election, ordering relocating the embassy be situated in Jerusalem, to the glee of Prime Minister Netanyahu, who won a sort of prize from the United States in official placement of a five-pointed star designating a capital in a city that sparked such sudden protests across the Middle East in early December, 2017, the United Nations Security Council immediately condemned the proclamation as destabilizing of any peace process in early December 2017.

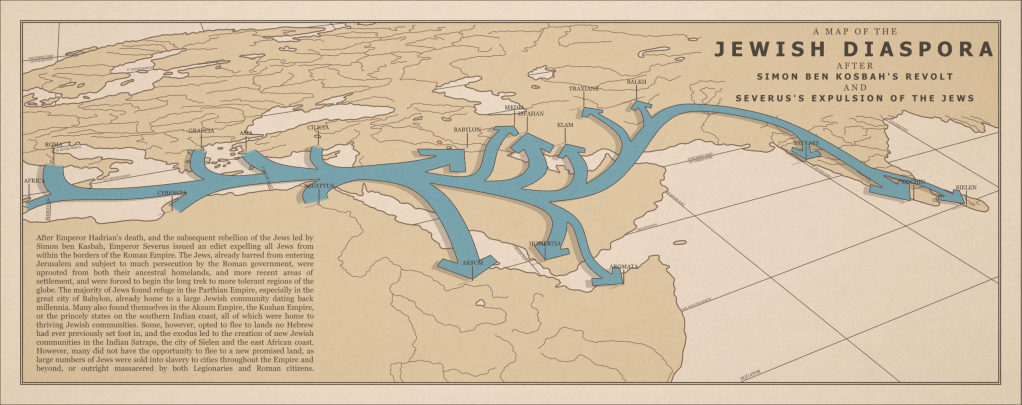

Trump saw the early declaration of a new site for the embassy as purely “transactional” more than political or ideological–“today, I am delivering!”— fulfilling a campaign promise he long ago made the late Jewish American financier Sheldon Adelson, who with his Israeli-born wife made it a hobby of vanity to meddle in Israeli politics and media. Trump wanted to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, he argued, before the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was resolved, echoing Sheldon and Miriam Adelson’s intense opposition to a two-state solution from 2017. The opposition grew into an agenda for the Israeli-American Council political lobbying group, arguing against history “the Palestinians are an invented people” to promote the right of return of diasporic Jews to Israel–promoting the Birthright Foundation with a half a billion dollars of their fortune to take Jews from across the world to visit the Holy Land to strengthen ties to Israel. By inverting Jews’ historic expulsion from the Roman Empire’s borders forbade Jews led to settle the expanded boundaries: whereas Romans forbade Jews to settle in Jerusalem or Palestine, the call of return inverted the wrongful diaspora created after wrongful blame for Hadrian’s death, the expulsion from the Empire’s borders ca. 133, effecting a “return” from the Empire’s edges in Egypt, Babylon, Italy, Spain, Eastern Africa or India.

Imagined Trauma of c. 130 AD Jewish Diaspora from Severus’ Expulsion of the Jews from the Roman Empire/ Radioactive_Bee/r/imaginarymaps

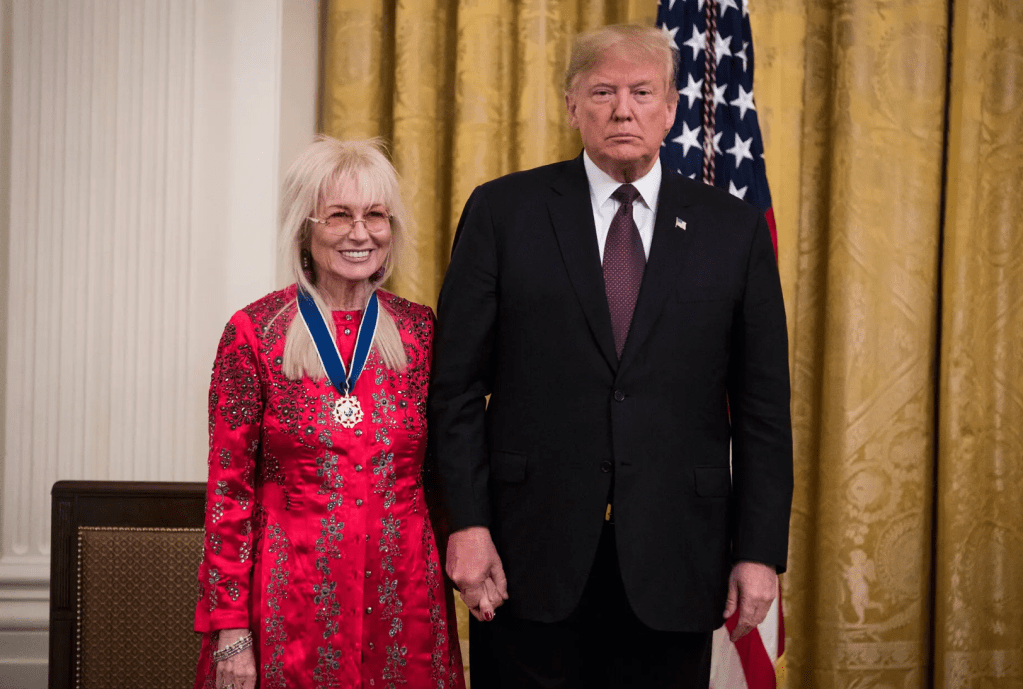

Miriam Adelson, a megadonor to Trump’s 2024 Presidential campaign, donated a sum second only to Timothy Mellon and Elon Musk, over $106.8 million, five times what her husband contributed in 2016, and has courted billionaires to support Trump’s White House bid. Her award of the Medal of Freedom in 2018 confirmed her role as a kingmaker of sorts, and she attracted a hundred donors to her own SuperPAC to swamp the airwaves of battleground states, convincing WhatsApp founder Jan Koum to add a five million dollar contribution. Her auditions of Republican candidates in Las Vegas became a litmus test that fed Trump’sinitial expectation that Trump she was good for $250 million in 2024–she aimed to drum up the support as Trump made it clear he demanded from mega donors to appreciate the strings he could pull after his return to office, reminding them repeatedly how much they had to be grateful for for tax reductionss, militaRY support and defense of Israel’s expansive boundaries, even after the Gaza War, alternating assurances over cozy candlelight dinners at Mar-a-Lago and text messages angrily demands donations to his campaign through Election Day to expand his support for moving the American consulate to Jerusalem, for which the late Sheldon Adelson had long mobilized support, provoking Miriam Adelson to demand Trump support an official annexation of the West Bank and deny all possibility of a Palestinian state. Critics of the Israeli counter-offensive in Gaza “are dead to us,” Adelson ominously warned; Adelson promoted not only Micke Huckabee for ambassador and Elise Stefaniak at the United Nations.

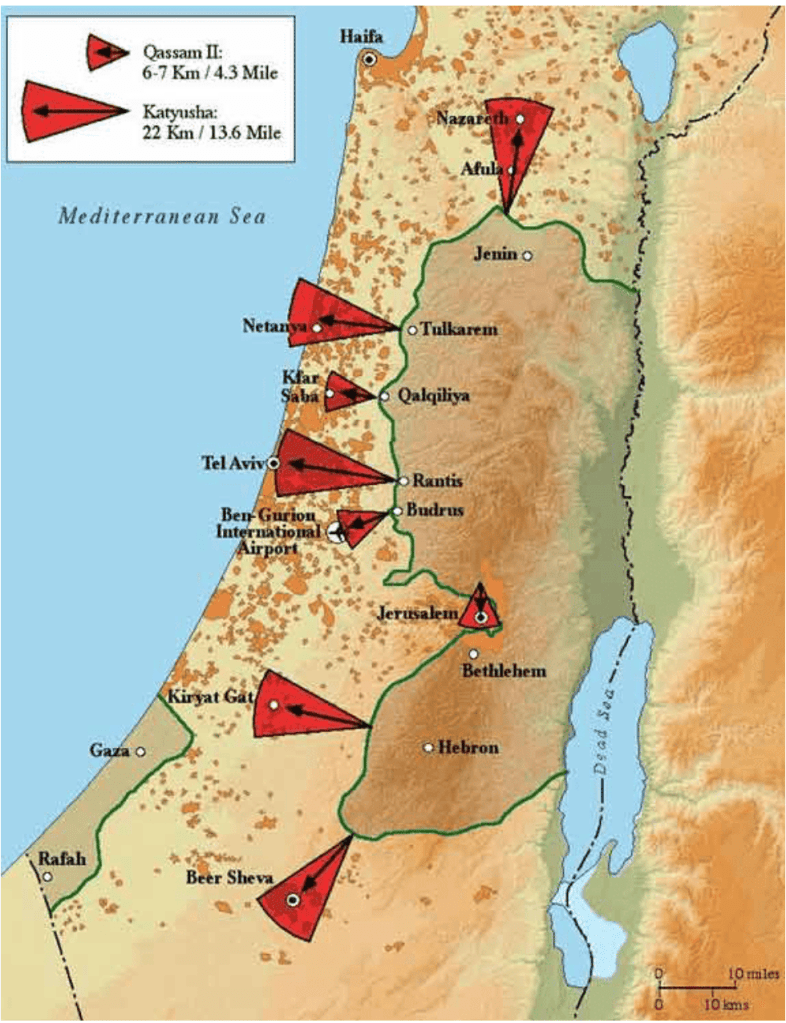

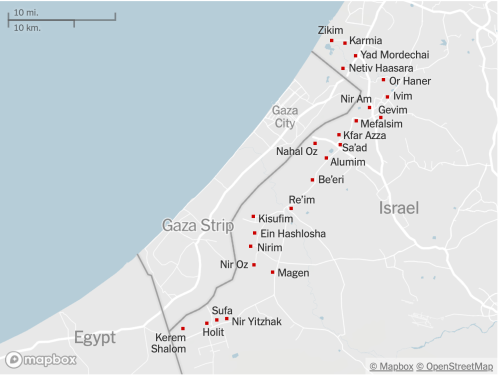

The myth of expulsion was mapped in the didactic style of an old schoolbook is fictional despite its authoritative arrows, the infographic attracted attention on reddit; it might be an icon of a diasporic imagination. Tracing the imagined consequences of a ban from the Roman empire’s borders after the Bar Kochba revolt, it embodis the mythic diaspora that Zionism seeks to reverse–a reversal invoked in the mythic geography as a basis to demand that Israeli law be applied to the fictional regions of Judea and Samaria–regions Israeli settlers have increasingly occupied, demanding military protection, that led to Likud demands to reject international law designating ‘Judea’ and ‘Samaria’ as “occupied territory.” This wanton elision of international law was basis for a roll-out of the “Trump Deal,” expanding a “Greater Israel” outside Israeli borders, a flouting of international agreements that must be placed in the chronology of current understandings of the Gaza War. The erasure of international law that was adopted in the Likud platform included a “right of settlement,” that continues to animate the current calls of right-wing ministers to “settle Gaza” and encourage Palestinian migration as a restoration of a “Land of Israel” as if it could be imagined as “the most ethical” solution to the currently devastating war, mirroring calls to settle the West Bank. The fears of actual threats of “rocket strikes” from Judea and Samaria have mobilized fears about the regions–the presence of settlers argued to prevent rocket strikes on Israel’s unsecured borders, as Israeli withdrawal from Gaza led Palestinians to fire Katuyusha rockets to Israel.

Map of the Rocket Threat from Judea & Samaria to Israel (2020)/Endowment of Middle East Truth

The fear of transforming Judea and Samaria to a grounds for staging a terrorist attacks on Jerusalem, Nazareth, Beer Sheva, and Tel Aviv makes the “green lines” of this map of rocket threats leap to prominence, and demand the protection of settlers’ de facto annexation of the West Bank.

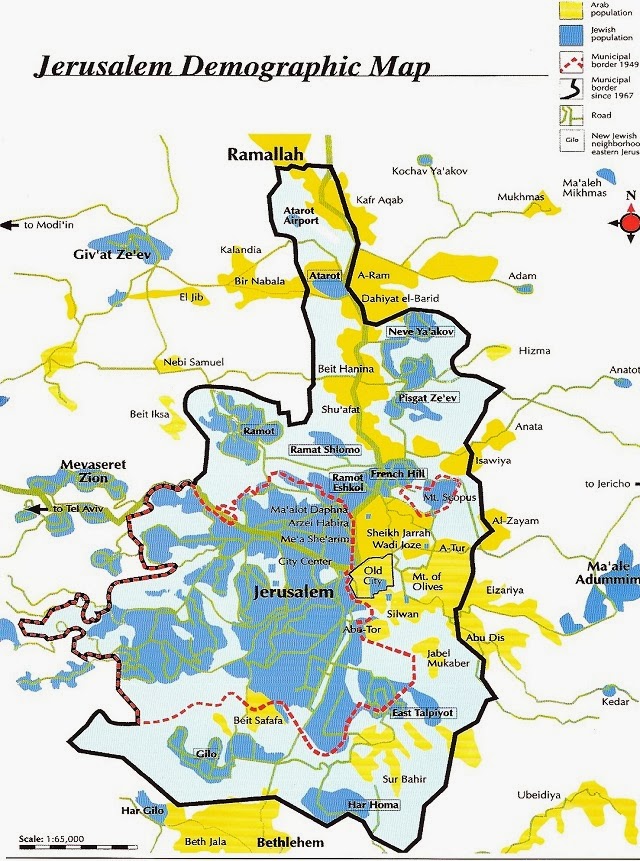

The securing of a “Greater Israel” is impossible to separate from the designation of Jerusalem as the capital. Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as a capital was an insult to hopes to secure East Jerusalem as the capital of a Palestinian State were placed on ice, even if Trump’s Texan Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, sought some conciliation in statements that the move “did not indicate any final status of Jerusalem” and “that the final status, including the borders, would be left to the two parties to negotiate and decide.” Despite such ample acknowledgement of some form of future agency, apparently betraying a lack of attention to details as actual borders, the interest in determining new borders–and defensible borders–were promoted in the “deals” to animate a promised “peace plan” resolve longstanding Palestinian-Israeli conflict, entrusted to the 38- year old apprentice, Jared Kushner, the son of the wealth realtor and son-in-law of the President, promising varied economic plans and proposals and touring six capitals, in a week-long trip of Middle Eastern countries, even after the Palestinian Authority preemptively had rejected any United States proposal after the affront of relocating the embassy to Jerusalem–long the center claims and counterclaims to the sacred center of any two-state solution, and the site of the division since Israel’s founding in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, long sectored by different temporal authority,–

— but unilaterally annexed since 1980, when Israel declared its capital, even if Palestinians make up close to 40% of its current population, and the city is divided in East and West, and bisected by a complicated curving wall, check-points, and gates manned by soldiers, increasingly to protect enclaves of Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem.

![[Chart]](https://apps.npr.org/dailygraphics/graphics/map-jerusalem-current-20180511/assets/desktop.png)

Boundaries featured, unsurpisingly, fashioned in simplistic, arrogant, and insulting terms in the different iterations of the Trump Plan, hardly led clarity to the islands of Palestinian population, but created a “green entity” linked by roads, and tied to the River Jordan, while offering Israel control over the West Bank, and being presented as a concession that allowed the fiction of an Israel that stretched from “The River to The Sea,” if one accepted the map’s general design. If the kingdom of Judea existed in the 9th Century BCE, to one side of the Jordan from the Ammonites and the Moabites, the historical populations of an ancient Kingdom of Israel was able to be mobilized, as the ancient Temple Mount in the Old City remained very much at the center of territorial dispute.

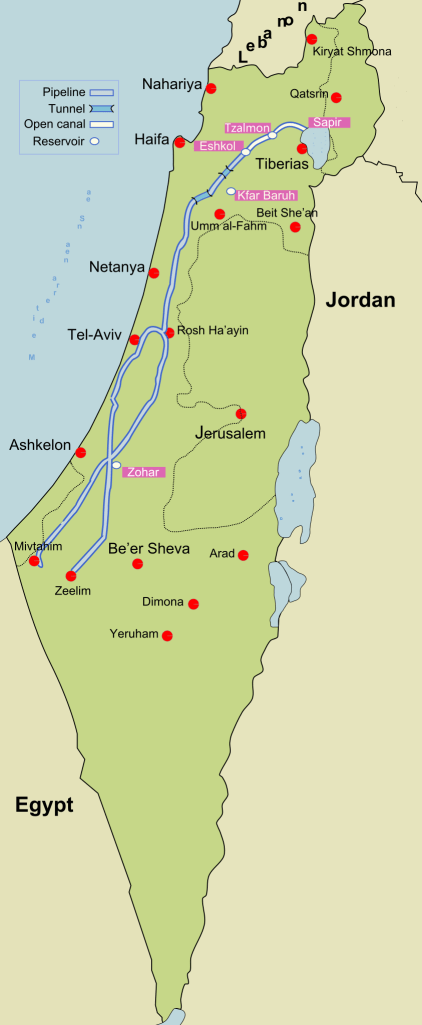

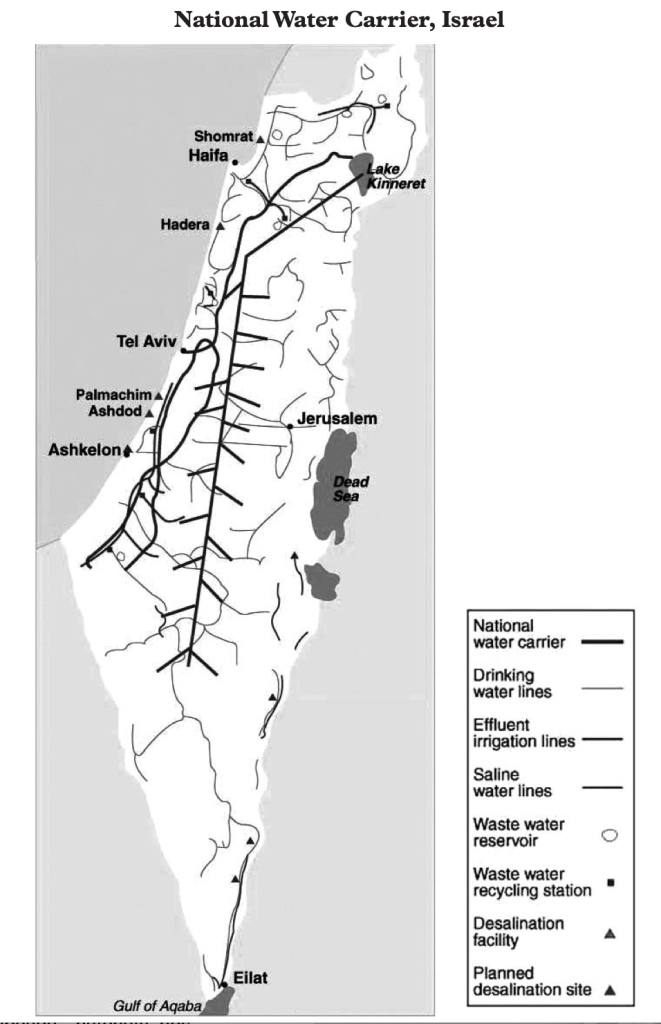

The Trump Plan proclaimed a resolution of Israeli-Palestinian differences with bluster as the first “plan” to be put on the table and have multiple signatories–save Palestinians, that is, whose arms were seeming to be twisted to gain approval through a broader international consensus and economic carrots to promote the far bleak futures of impoverished residents in a Gaza Strip, but required no Israeli concessions. The map granted single isolated port city for Palestinians, was premised on drilling an underground Gaza-West Bank Tunnel (!) linking Gaza to the Palestinian enclaves lying at a remove west of the River Jordan, suggested a massive remaking of Israeli state’s position of strength in the Middle East, and victory of absolute recognition of Israel’s right to exist from Palestinians–the map was a map that would guarantee recognition of Israeli boundaries, rather than a Palestinian land.

The promises that the Palestinian economy might be boosted by planned residential, agricultural, and industrial communities way to the south of Rafah, if an acknowledgement that few fertile lands would be in the reduced Gaza Strip, would be oddly placed at a remove in the Negev, linked by thin roads or causeways along the border with Egypt, fragmenting the Palestinian presence.

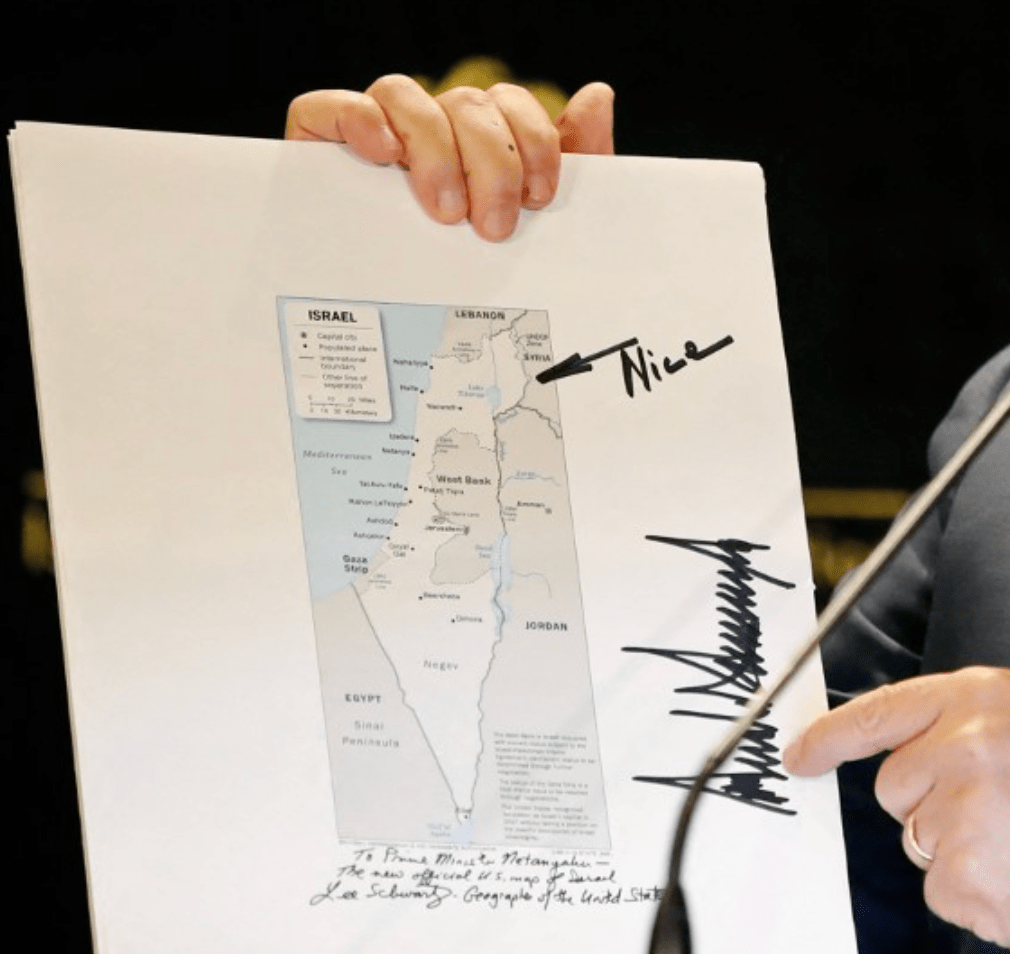

But the closest appearance of Trump’s figurer prints lay on “the new official U.S. map of Israel” that Trump personally allowed Kushner to give to Prime Minister Netanyahu, as a promise to be in his court, in his February 2019 trip by the apprentice Kushner, the thirty-eight year old son-in-law Trump had placed in charge of the deal he called a “peace process’ that at last recognized the Golan Heights–a site of the current war between Hezbollah and Israel–as Israeli territory. This map set a powerful precedent of similar international precedence essentially recognizing lands occupied since 1967, and annexed to Israeli territory in 1981, removing what the rest of the world recognized as Syrian territory that the Israeli army had occupied, as part of Israel’s sovereign grounds. Indeed, the “plan” registered a severe and unidirectional loss of Palestinian lands that Al Jazeera was quick to note, removing lands form Palestinian sovereignty to make the Oslo Accords look like the good old days, shrinking land under Palestinian control away from the West Bank and limiting jurisdictions.

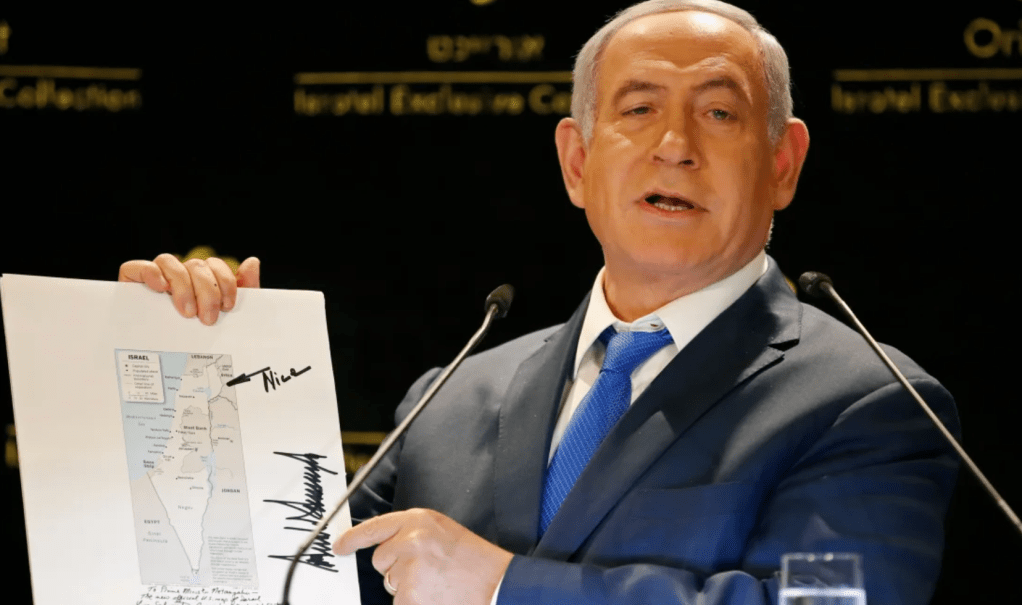

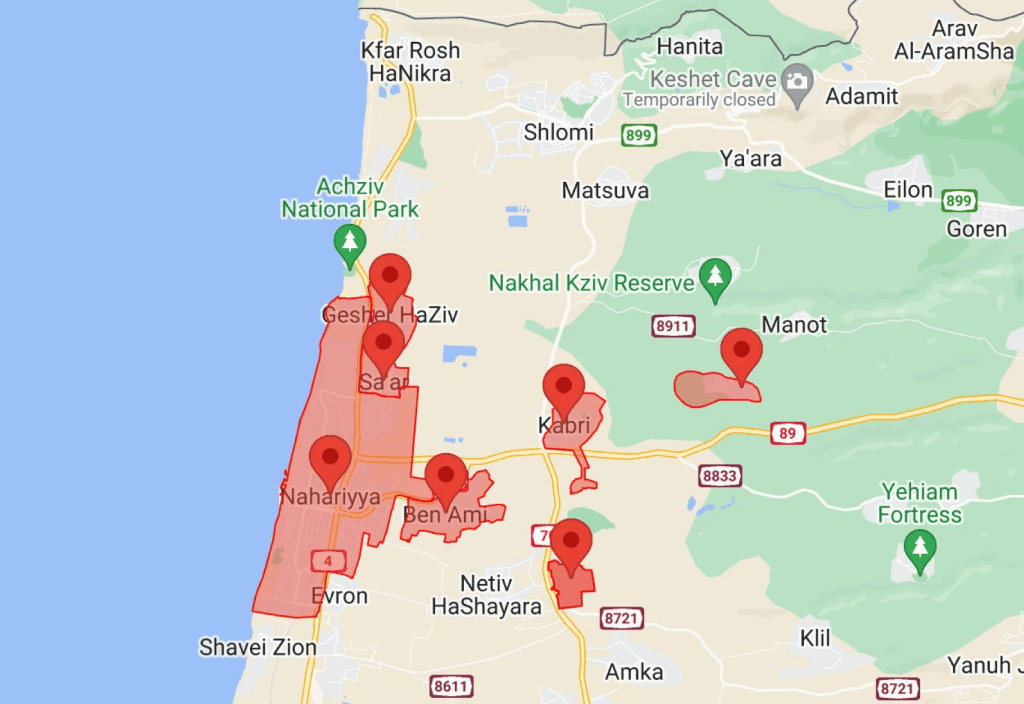

If the firing of many Hezbollah rockets into “Israel” were target at the Golan Heights in recent months, the unusual map presented Netanyahu two weeks before what would be his reelection became a slap on the back and endorsement, labeling Israel’s annexation “Nice!“ Recognizing the reality of what were deeply contested boundaries as straight lines, Trump took to what was then Twitter to tweet he was “hoping things will work out with Israel’s coalition formation and Bibi and I can continue to make the alliance between America and Israel stronger than ever. A lot more to do!” The recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights had been formally recognized on the visit of Netanyahu to the White House in an earlier proclamation of March 25 confirming Israel’s ability to “protect itself from Syria and other regional threats” in defending the Golan Heights–a move of chess of fundamental import in the current war against Hezbollah and invasion of Southern Lebanon by the Israeli army. The arrival of Kushner with the map in April, just before the Israeli elections, led him in May to showcase the “update[d]” map as the basis for the Trump ‘Peace’ Plan.

The proclamation asserted a deep commitment of the United States to the acknowledgment “any future peace agreement in the region must account for Israel’s need to protect itself from Syria and other regional threats,” not naming non-state actors but giving backing and carte blanche to the Israeli leader to defend enhanced boundaries of the state. When the map was displayed by Netanyahu at t press conference, he crowed “Here is the signature of Trump, and he writes ‘nice.’ I say, ‘very nice!'”–as if delighted with the new objective truth and framework the map set forth.

The sentiments were reprised in Kushner’s late May public statement stating “The security of Israel is something that’s critical to the relations between America and Israel, and also very important to the President, and we appreciate all your efforts to strengthen the relationship between our two countries;” Prime Minister Netanuyahu happily stated Israel’s relation with America had “never been stronger, and we’re very excited about all the potential that lies ahead . . . for the future.” The powers of prognostication were in a sense supported and formalized but he

May 30, 2019Thomas Coex/AFP

The election of April, 2019 was hardly a massive victory for Netanyahu, if it meant a fifth term. His political party won a mere 35 of 120 parliamentary seats, but it placed him in a new alliance with the far-right parties that had been engineered by the cartographic gifts that Trump had provided the Prime Minister became props for a new form of political theater with which Netanyahu was particularly taken. The map was a gift that kept on giving, a new knowledge system to deploy the firmed up boundaries of the Israeli nation that no other nations would recognize save the United States. Even if it was not a recognition of “reality,” the flouting of international consensus offered Netanyahu a needed shot, a show of support for the defense of current expansive borders, and even support of the arrogance of drawing borders,–as if the “Geographer of the United States,” Lee Schwartz might take up a larger role in the State Department, where his office was in fact located.

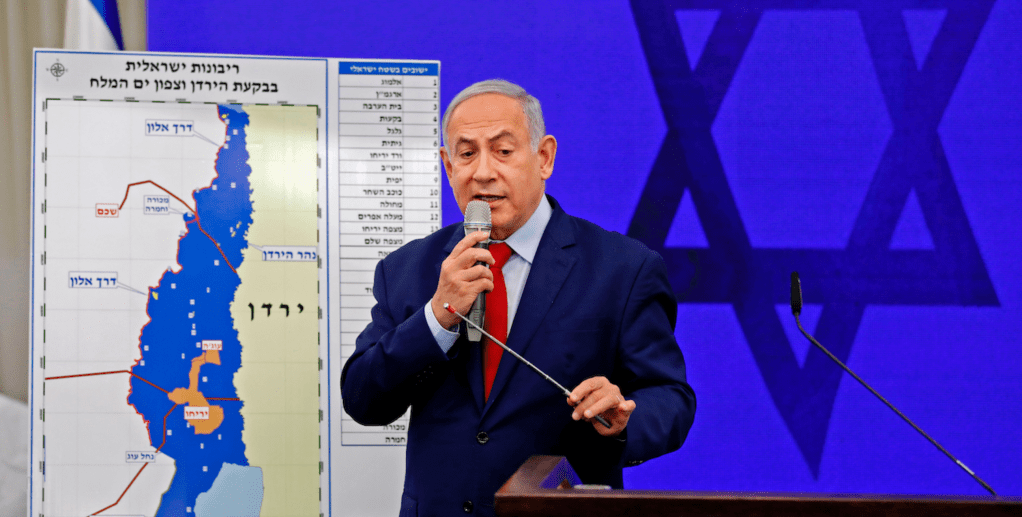

This map was the gift that kept on giving, a showpiece of sorts that preceded the many maps that Netanyahu quite triumphantly brought to the United Nations, maps that set the precedents for the maps Netanyahu brought to the United Nations General Assembly to lecture the world on the possibilities for peace in a New Middle East, in which Israel controlled the full West Bank–a map he had displayed before the April election on Israeli national television, and the map where Gaza was shown to be part of Israel, absorbed in an attempt to focus on the international alliances that Israel was announcing, the small details of Palestinians’s hopes for territoriality were dwarfed by the fantasy of a new community of nations–that led to campaign promises to incorporate the West Bank to affirm an expanded Jerusalem at the center of the Israeli nation, reaffirming in “blue” the territory of a united Jerusalem that was nestled right up to Jordan in the 2019 election. The map was a political promise to expand Israeli territory in the West Bank he insinuated the Trump Plan would allow him to annex in the Jordan Valley, due to his close relation to the American President.

The speech before the 2019 elections promised “Peace and Security” as if citing Revelations 19:20, at time when the contents of the Trump Plan were not yet fully known, and the power of suggesting a major remapping of the relation of Israel to the West Bank might be persuasively made. The map, whose logic seems to underlie the claims of the map of the “New Middle East” Netanyahu would use before the General Assembly, on September 23, 2023, just weeks before the October 7 invasion. Indeed, the image of an annexed West Bank suggests a negative image of the invasion of Gaza, or make Jericho, as Youse Munayyer, the Director of the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights put it quite succinctly, leave Palestinian residents of Jericho dependent on Israeli authority to enter and exit what would be a “new Gaza, another open-air prison Israel can lock down as it pleases.” The desired transformation of almost a quarter of the West Bank by the wave of a magic wand into an area of Israeli control area would disenfranchise Palestinian residents who would lack all voting rights or citizenship, but live in a system of limited autonomy might be better called apartheid, controlled by a minority of Israeli Jews.

Menahem Kahana/AFP

What Netanyahu boasted was a “dramatic” plan and opportunity for fragmenting Palestinian communities within Israel was hardly a “deal” acceptable to Palestinians, and prevent a future Palestine, annexing a quarter of the occupied territories. Describing the option as able to be realized by virtue of his privileged relation to Trump, he openly appealed to far right parties: by calling the Trump Plan “visionary” in scope, he offered the vision of a containment of Palestinian hopes for sovereignty in an Israeli state that was in fact recycled form a 1968 plan for a divided West Bank that annexed rural Jewish settlements to an expanded Israel, while allowing enclaves of Palestinian communities around Jenin, Nablus, Ramallah, and Hebron to formalize ties to Jordan.

Netanyahu’s 2019 Proposed Annexation of West Bank and Confinement of Palestinian Civilian inhabitants

But if Netanyahu spun fantasies of new borders and expanded Israel out of maps, this post is about the fate of the Trump maps. For the presentation of that map–and the map of a peace proposal that demanded no sacrifices of land for Israel–seems the tipping point of sort. The maps played a large role that provided Netanyahu with the credibility of a statesman in Israeli national elections, a gift allowing Netanyahu to claim control over territory that Israel had not won recognition by the rest of the world. When Netanyahu displayed the personally signed map to the nation in a news conference, even if he failed to assemble the coalition needed to gain a second term, the Prime Minister used the maps s prop to affirm his ability to navigate the nation to the future defense of its borders and boundary lines by his personal ties to the United States President, a gift of statecraft that materialized boundaries of a newly expansive sort as if they were a true consensus. Displaying the map helped his foreign policy expertise to be leveraged for a new term. He quite quickly invited Americans to visit the new Israeli town he in northwestern Golan to found in Trump’s name to acknowledge the meaningful nature of geographic recognition of the Golan plateaux under Israeli sovereignty, voyaging to the region to celebrate Passover as part of a “thank you” for the gift of an American president who “recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights forever,” declaring the foundation of a new permanent village be named after the former American President.

Was the gift of the map that Kushner was entrusted not the basis for the forging of a new personal friendship of transactional sorts that Trump was able to present Netanyahu as a promise to stand behind the Israeli Prime Minister’s illusions of protecting Israel’s greater borders, to protect its security? The United States Geographer Lee Schwartz, who signed the map that Trump entrusted Kushner, lists his remit as “defining detailed and advise policy makers on territorial disputes to aid international boundary negotiation may have gone above and beyond his role to offer “guidance” on the ways boundaries are shown on government maps, to adjudicate and resolve international disputes, as Schwartz had in Kosovo and the Baltics, and to guide the Office of the Geographer and Global Issues–a weighty title, not to suggest that folks at the office didn’t also have fun with maps.

Dr. Lee Schwartz with INR/GGI Team at the Office of the Geographer on Global Issues, 2019/Isaac D. Pacheco

The office of Geographer had evolved in a global context after the Cold War to endorse claims of sovereignty and international boundaries to federal agencies became a platform of sorts to curtail the advantage of redrawing boundaries, as well as determining problematic questions of naming, even adjudicating maritime boundaries that addressed “global issues” analytically from an office within the Department of State. Haing taught at American University in Washington, DC, with a background in the Cold War, Schwartz was soon recruited at the State Dept. to work in the office of regional analysis, specializing in refugee affairs.

The drawing of boundary lines recognized by the U.S. Office of the Geographer were trusted as “holding up in court cases.” The Office used s “compelling evidence” to map states in the Balkans, that were seen as far more compelling than satellite views. But the maps of Israel’s expanded sovereign bounds launched a missile at the heart of Hezbollah and of Palestinian claims to the region, providing “legal” validation of Israeli territoriality anticipating Israel’s legal rights to territory above any other nation, offering legal validation of the expansion of Israel’s frontier outside the United Nations or international community. Which makes the speeches Netanyahu delivered all the more frustrating. For his cajoling of the United Nations General Assembly to “go along” with new maps in future years played fast and loose with the shifting toponymy of a country much as Trump’s unilateral shifting of the United States Embassy to Jerusalem. The recognition of Israel’s capital as Jerusalem led to the renaming of a small square in Jerusalem beside the embassy’s new location after the United States President, nominally in recognition for his having the courage to “stand on the side of historical truth and do the right thing”–coopting the phrase in an act of pretty radical historical revisionism, eliding the sacred and the secular and echoing biblical geography for his American fundamentalist audience. Trump may not be personally invested in a Christian Zionist vision; but he has cultivated religion as a critical constituent in the marketplace of ideas as a valuable investment. For Trump, the sacred rhetoric easily bled into the image of a strongman. It was fitting Trump concluded his campaign by arrogantly assuring audiences should God “come down and be the vote-counter for just one day,” Trump would win decisively states with immigrant populations–he singled out my blue state of California–by excluding illegitimate votes.

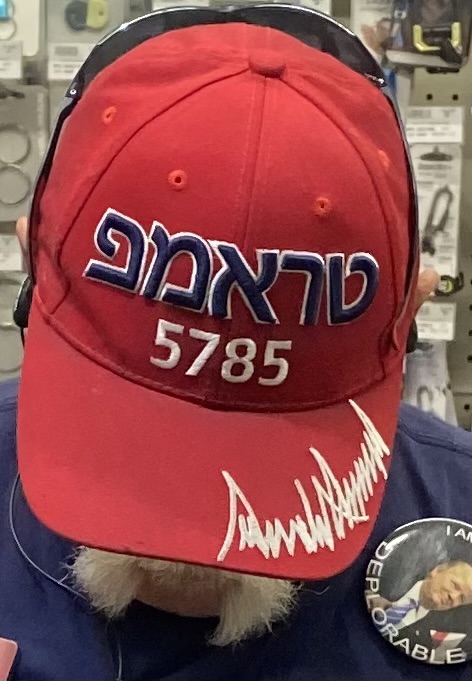

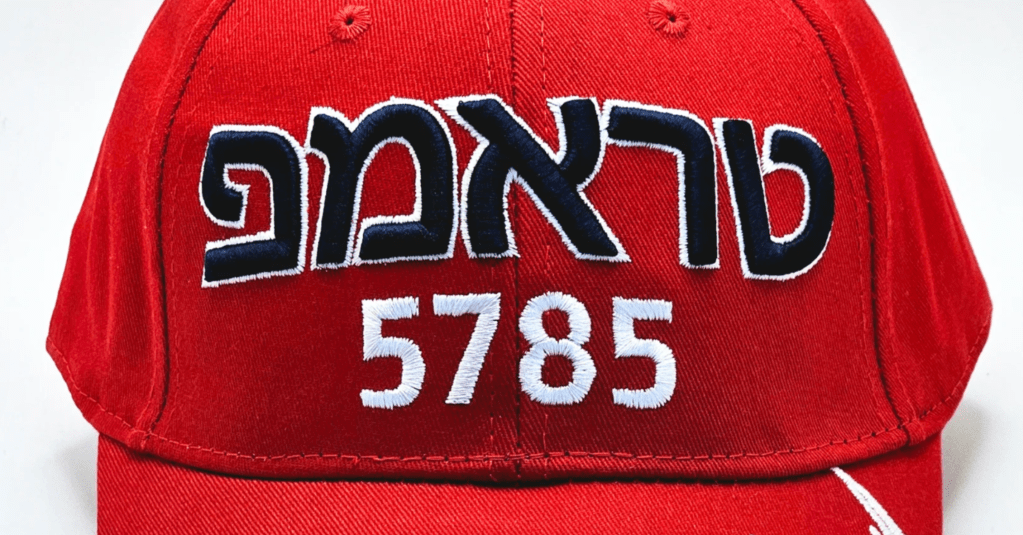

For a strongman who has advantageously coopted agendas, cobbling together religion and apocalypse provided vast reservoirs of hyperbole in Donald Trump’s political imaginary. The survival of a sacred image of Israel has gained an untold and terrifying prominence in the American imagination, not of Puritanism, or of a nation in the wilderness, but of of apocalyptic meaning, as Trump himself assumes a near-biblical prominence as a prophet in the MAGA world who is able to claim a historical destiny not only for Israel, indeed, but, by way of extension into the notion of a sacred nation of America, within the ultranationalist imagination. In this imaginary, territoriality of scriptural sanction bears a close family resemblance to the fundamentalist insistence on borders over rights, and of near-divine sanction, in the promotion of the southern border of the United States as it is promoted with a near-apocalyptic vein and verve. While the same twill cap retails on Etsy for $29.99, it opened a view on a mental geography I was quite surprised to see in the Sierras offered a window into how Christian Zionist imaginary invested the geopolitics of the Middle East with prophetic meaning. Tapping an evangelical strain I associated more with Mike Pence, the cap seemed an artifact of globalization, hardly out of place in Ace hardware store in Nevada stocked with objects made in China. But it provided a vividly sense of the access to Middle Eastern politics the Trump campaign promised that I hadn’t ever appreciated with such sudden and direct impact.

The year 5785 that began at sunset on October 2, 2024 places Trump’s Presidential campaign in a calendar not of the secular world but from creation, by God’s calendar, beyond any political cycle or national calendar. The year end of times destruction may be the conclusion, revealed in the Hebrew letters of Trump’s name on a cap fit for a coming apocalypse, more than any election, seemingly signed by the signature of the very same executive proclamation that recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s national capitol, and cemented Trump’s symbolic ties to a Holy Land. The headgear that was in fact widely available online was no doubt not made in America, but was an ideology whose eschatological implications sent my head spinning as I was preparing to canvass voters who might be eager to support a ticket that was ready to promise it was zealous to acclerate Armageddon, and eager to promote a sense that the proverbial prophetic writing was indeed already on the wall.

Hebrew Hipster ships the RUMP VANCE 24 (2024) in Hebrew Embroidered Baseball Dad Hat from California

Hebrew hipster ships the MAGA kippa, needless to say, as well as MAGA twill caps, for the faithful.

But if the Jewish electorate or “vote” is important, the evangelical may be as critical. For the cap remained me how much the end times teleology of Christian Zionism was apt to link the current election to a date ready to be remembered by the Jewish calendar from creation. The awakening of 5785 suggest a deliverance and spiritual rebirth that is provided only a candidate inspired by the breath of God, no matter what events are occurring in the world: if 2020 was a season marked by a lack of faith, the coming year would bring a final revelation of God’s word, to combat the Moabites, Ammonites, and the proud people of Mt. Seir attacking the nation of Judah, for Israel to occupy the restoration of its full territory in the year when Israel and America will, per Christian Zionism, also recover territory the enemy had wrongly entered as the entire nation will come to repent–and by Psalm 85, in order to restore divine favor to the land–lest abortion, same-sex marriage, trespassing against one’s created identity, and absence of prayer inspire God’s Old Testament wrath. Let us heal our land in the first forty days of the Jewish New Year, lest it be destroyed by his fire.

Ace Hardware, NV

A semiotic decoding of the hat, so overdetermined in its Hebrew lettering and Old Testament associations, is challenging, so cluttered is it with symbolic paraphernalia, accumulated symbolic identities of faith, nation, and masculinity to resist interpretation, subsumed in combination of Old Testament faith and Christian apocalypse, save as an announcement of destiny to prepare for the awaiting of the Rapture. It proclaims that the faith of “proud deplorables” intersect with a vision of Trump-as-biblical-prophet of apocalypse whose time has indeed come in America, even if it may begin in the calendar of Hebrew scripture.

In proselytizing a candidate for the American Presidency in black Hebrew letters date the campaign from the creation of the world, the salesman I met while canvassing was promoting a cult of personality as a prophecy destined to inaugurate a new historical era more than a President. Even in a store selling goods mostly produced overseas, the largest proportion probably in China, the cap reminds us to place Trump’s candidacy in a global context, as much as one of Making America Great Again, transposed from a medieval universal history culminating in the Apocalypse, which resonated strongly with the Fundamentalist origins of placing the capitol of Israel back in Jerusalem. While I was in the state to encourage voting, I didn’t need to reflect much how the prophetic vein was bound to elicit votes far more effectively than an army of door-knocking volunteers. Could it be that in the current United States, apocalyptic rhetoric has become the ultimate strategy of getting out the vote? In affirming right-wing Zionist Israelis hopes to restore God-given borders of sacrosanct nature, mutatis mutandi, the logic of territoriality was doubtless but a reflection in many ways of continuing to defend “our” borders as well, and a restoration of its rightful extent and “legal” boundaries in maps, no matter the situation on the ground.

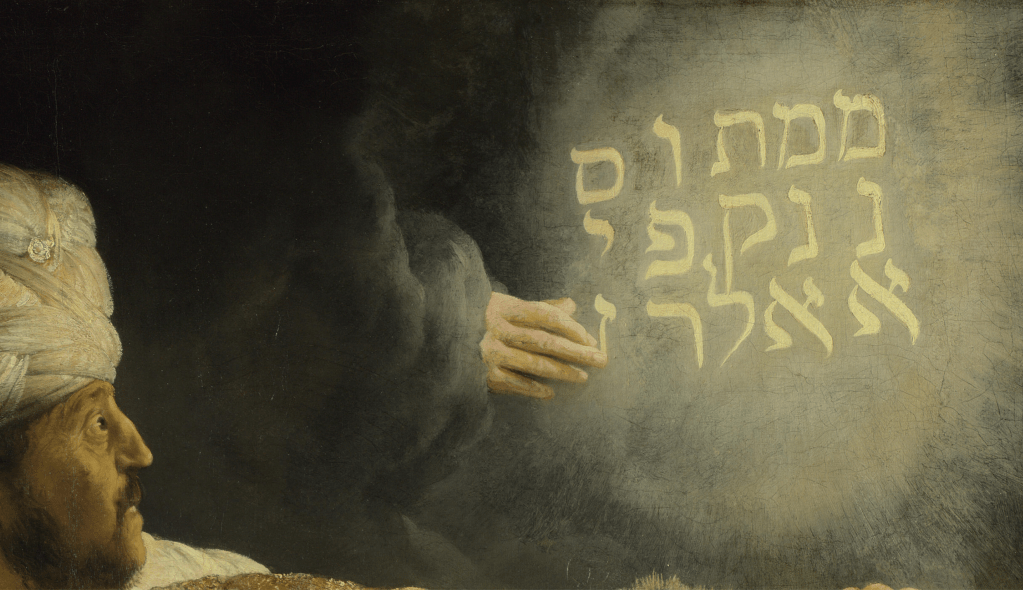

Borders were framed in prophetic ways for 5785, as if created by the force of worship: as if the expectation of the year were an anointing of a monarch, able to set those borders, returning to a new level of reverence for life, and restoring favor to the land; numerologic glosses on this year’s digits, 5 + 7 + 8 + 5 = 25, or two fish and five barley loaves of abundance, affirmed God’s intelligence in providing, and encouraged thanks to God’s demands for a candidate to enact his will, and service in the election to confront those intimidating giants that have threatened the nation as David threw five stones against intimidating giants with the outpouring of spirit and a new battle plan. Despite transposition of loaves and fishes to decipher the prophecy of the year, the gloss demanded believers give freely of what God needs of us–votes for Trump?–to steward of things beyond individual needs. The message emblazoned on the man’s cap burst on the eyes of customers akin to the revelation of the prophetic writing that burst before the eyes of Nebuchadnezzar as he stole the sacred goblets and golden cups from Jerusalem’s Temple, perhaps seen as somewhat akin to the stealing of the vote and White House–as prophetic words of caution and terror, “mene, mene, tekel, upharsin“, letting him know the4 days of his kingdom are indeed numbered. If Svetalana Alpers argued that Rembrandt painted gold objects and clothing to play with the value of the painted work of art, the below painting of Belshazzar’s Feast, far from a foray into the baroque, is an escalation of the rendering of gold of a new level of the divine sublime of perhaps the greatest value–gold letters drawn by the disembodied hand of God, a model far from the glittering if polished mock-gold facades of hotels Donald Trump so delighted to inscribe his own name in capital letters to convince the world of their inestimable value.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Belshazzar’s Feast (1635-1638), National Gallery, London (Daniel 5:1-31)

Only the visionary Daniel can interrupt the mysterious letters–apparently arranged in an acrostic cypher, that evaded the interpretation of any Babylonian wise men, as a prediction of the doom of the king and his dynasty. The failure of the royal astrologers Belshazzar had summoned to read the golden letters were only able to be read by the visionary Daniel, who realized the doom they prophesied was evident to all who read the letters as columns, rather than trying to force meaningful words by reading from right to left. The discovery that God had numbered the days of the kingdom of Belshazzar in the Masoretic text depended on glossing the same verb as both senses of “numbered” and “finished,” the third column as “to weigh” and “find wanting,” and the fourth as both “divide” and “Persia.” In the electoral fantasies of a divided nation, wanting the election of a true leader, the cap had of course provided the illustration of a direct tie of individual to leader, a sartorial proclamation of a direct allegiance to a leader akin to the brown shirts of Nazi storm troopers issued from 1925 or the immediately recognized uniforms of Mussolini’s blackshirts.

If the inscription that Belshazzar witnessed on the Temple walls demanded Daniel’s interpretation to decipher, eluding even the Babylonian wise men, any in the know grasped the meaning of the revelation of Trump’s name in Hebrew–a revelation akin to the inscription traced on the Temple wall. There is nothing wrong transcribing a candidate’s name to Hebrew characters–but the valor into the cap seems to violate a division of church and state, commanding a vote for a candidate as if it was a message from on high, and question of obedience to God. The inscription of Trump’s name in Hebrew characters assume a divine command, as if invoking a scriptural authority in Trump’s support. Rembrandt relied for the top-down columns of his painted Hebrew characters on the learning of a rabbi and printer who lived in Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter, Manasseh ben Israel, despite incorrect transcription of one character–a zayin for a nun–render the luminous prophetic inscription traced by a disembodied hand on the temple wall to the amazement of all present:

Rembrandt van Rijn, Belshazzar’s Feast (1635-38), detail: Inscription on Temple Wall, ( )

)

The difficulty in interpreting the Aramaic chiding that was included in Daniel 5 derived from the encoding of the sacred message in an early form of encryption, a matrix of coded data that demands to be read from top to bottom, rather than right to left, an early form of cypher that was historically accurate, but pushes us to demand the decoding that hat. If the son of Nebuchadnezzar, the conqueror of Jerusalem, had not recognized his own hubris of destroying the Temple and carrying off its sacred vessels to be used as goblets to drink wine at a banquet with his concubines, the cryptic message demanded God be shown reverence as it was dramatically inscribed on the palace wall. If the glitter of gold was a frequent color Rembrandt used in his studio paintings, from helmets to coins to a cuirass, and the artist must have delighted in depicting the abundant wealth of Belshazzar’s Feast by painting the sacred goblets of gold and silver stolen from the Temple.

The set of stolen sacred goblets seem suddenly to fall as God’s hand leaves a shimmering on the palace wall. A shocked Belshazzar sees the inscription with terror as he turns a turbaned head atop which a gold jeweled crown seems to totter; the inscription warns his days of rule are numbered and his dynasty will fall due to failure to honor Israel or the kingship of the God of Israel: the “writing on the wall,” that claims inevitable restoration to a throne of rule by one who honored God in words, Mine, MENE, TEKEL, UPHARSIN, that outshine even his glittering royal gold encrusted cloak.

For the candidate who still reminds audiences of his plans to laud efforts to Stop the Steal, the story of Belshazzar is not only biblical legend. It may even form a natural part of the aura of a God-given inevitability of his return to the United States Presidency. Trump eagerly revealed at a Pennsylvania rally in mid-October how in a “very nice” [telephone] call” he gave Netanyahu his blessing to “finish the job” in Lebanon and Gaza, promising “you do what you have to do” when it came to defending Israel and its border, determined to allow Israel to “ultimately make decisions according to her national interests.” Trump’s affirmations of placing a premium on Israeli interests revealed the far more solid commitment of his relations to Netanyahu than Biden’s; it made him a true confidence man. Trump regaled audiences with how Netanyahu took his call from his private vacation residence in Caesarea after it had been targeted by a drone, reminding supporters of their regular contact, as if to evoke the deep ties a Trump presidency would have to Israel. Trump had, after all, from 2017 transferred the American Embassy to Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, removed the Palestine Liberation Organization from Washington, D.C., stopped referring to Israeli settlements as illegal and ensured the United States State Department no longer called the West Bank “occupied territories.” This was the very map that Netanyahu presented the United Nations.

To flip the metaphor, the writing was indeed on the wall–and on the map!–since Trump removed occupied territories on the West Bank from State Department map. This “new map” was indeed but a model of the Middle East that the Trump Presidency worked hard to map. In the cap I saw as I canvassed in Nevada, Trump’s name seemed to affirm his destiny to win the election, an event of such historical importance fit for counting from the creation of the world. In ways that recall the insidious intermingling of the sacred and secular in the Trump Presidency, the Presidential election of “5785” has become in large part a referendum on Donald Trump’s continued defense of the United States as a sacred nation with boundaries the former President has defended as if it were sacred and worked to sacralize.

The man’s cap was emblazoned with a logo so aggressive to be tantamount to a revelation: it was nothing less than a divine endorsement from on high, on a bright red field that may as well be glittering in gold. It reminds us of an end times philosophy, and a Republican Party exhorting more arms flow to Israel to defend the sanctity of the borders of a Holy Land. It affirms the impending inflection of global history 5785 is destined to bring. Indeed, the date on the cap may gesture to revelation of Ezekiel 47:13-20, sketching “Boundaries of the Land,” a vision of the future boundaries a restored land of Israel, running east to the Jordan, that run near Damascus, unified “into one nation on the mountains of Israel” with a temple at its center.

This vision of reconstituting the State of Israel was of course of meaning among Christian Zionism not as a political affirmation of an apartheid state, but a precondition for the end of time, and return of Jesus; the religious right’s ideology interpret all Middle Eastern politics through the lens of a prophetic of end-time teleology and premillennial belief, more than geopolitical dynamics let alone a demand for human rights. The previous President has nourished if not cultivated an intentional confusion of a vision of geopolitics with one of spiritual authority and territory with a revelation of a scriptural legibility. Even as we continue to insist that the conflict is between nation-states and ideological in nature, and demands to be solved between nations, by shuttle diplomacy and Secretaries of State, the confusion between a sacred map and a map of territoriality of the Middle East has been nourished in that vision of the Middle East for decades, juggling around the pieces as if to find a winning and unable solution. For we continue to insist that the conflict is geopolitical and at base ideological and between nation-states, in ways that blind us to its distinct and deep-seated nature of these claims of territorial possession, as if is between nations among other nations, as if purposefully creating and bequeathing blind spots in our maps.

5785 has been called a year to invest kingly and priestly authority, await divine intercession and kingly rule, a year of righteousness and peace where the Lord will give what is good to yield increase and a year of awakening. If the current Middle Eastern situation has proven to be a time of crisis not only in Gaza and Lebanon, and Israel, but a moment of revealing the lesser role that the United States can play in global affairs and global wars, an apparent lessening of authority and prestige that seems to show the weakness of the Biden administration, and reorient America’s relation to the world, and the apparent erosion of anything approaching a secure grip on global affairs. In the legend of Balshazzar, the hubris of the worldly ruler is punished by the inscription of the legend that the King immediately beholds, with his assembled guests, who dropped the sacred goblets from which they were obliviously drinking wine in shock. “The God who controls your life breath and every move you make–Him you did not glorify! He therefore made the hand appear and caused the writing that is inscribed: Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin . . .” that predicted the doom of the pagan ruler and of his dynasty, from a God who would soon bring both to their ends (Daniel 5:22-25). The writing was, as it were, on the drywall in the Nevada hardware store that I glimpsed the MAGA hat two weeks before the Presidential election. Maybe 5785, I thought, will be a year all plumbing issues will be suddenly resolved, fixtures will be free and lightbulbs easily able to be returned.