When addressing the new Latin American policy in Miami’s Freedom Tower in late 2018, the new National Security Advisor John Bolton targeted Nicaragua and Venezuela in a striking geographic metaphor. He offered a new metaphor for described the dangers of a “triangle of terror stretching from Havana to Caracas to Managua,” in November 1, 2018, demonizing Latin America and the island of Cuba in terms that suggested possible plans for “taking direct action against all three regimes to defend the rule of law, liberty and basic human decency in our region.” As if to displace attention from the Northern Triangle from which so many asylum seekers have fled to the United States in recent years, including unaccompanied minors, and where civil society is overwhelmed by drug trafficking, gang violence, and police corruption, the new triangle Bolton seeks to shift attention is a target.

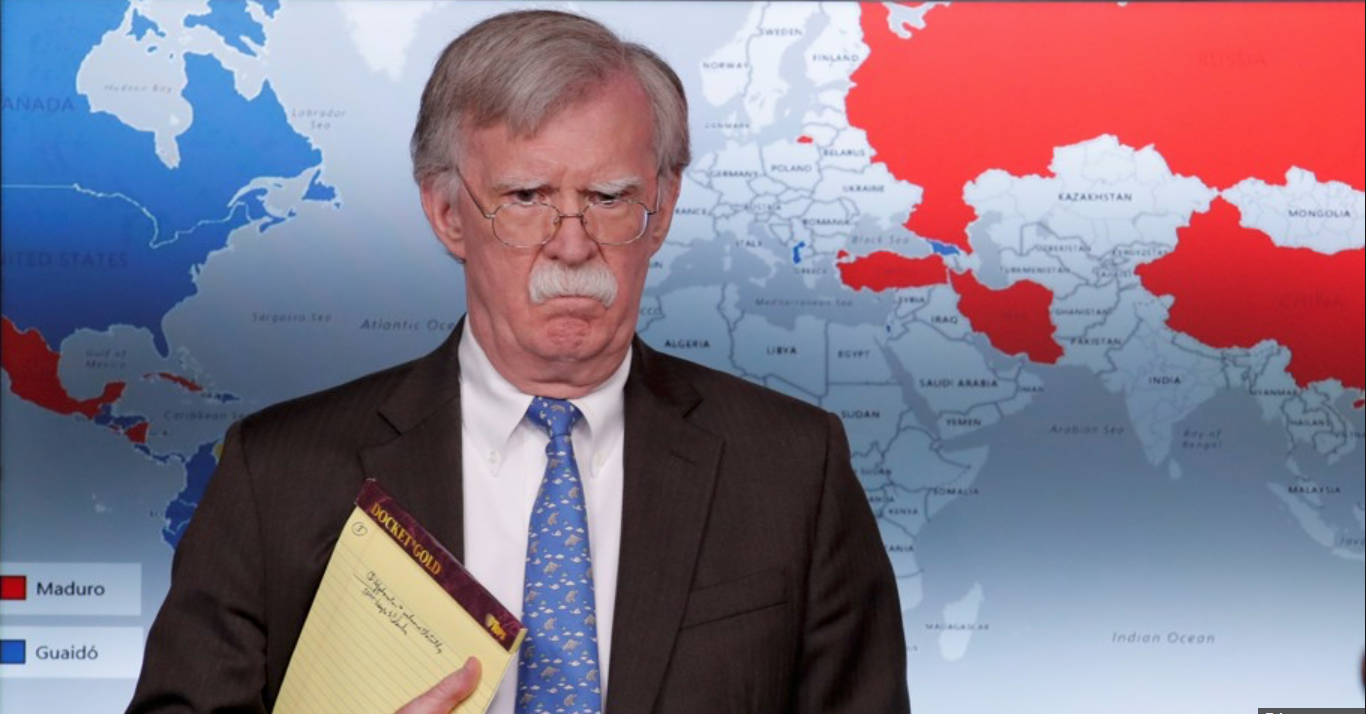

So it may have been no surprise that when attacking the legitimacy of Socialist Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela by imposing expansive sanctions ton Venezuelan oil and gas, Bolton seemed to tip the cards of power. Upping the ante from defining the Socialist regime of Venezuela as an apex in a triangle, in previous saber-rattling that committed the United States to striking a blow at a “triangle of terror” tied to the Socialist heritage of Hugo Chavez and to Raúl Castro, Bolton “appeared to disclose confidential notes written on a yellow pad” to reposition military troops to Venezuela’s border, standing before a global map the divided the globe in no uncertain terms, as if announcing a new configuration of power in his role as National Security Advisor for Donald J. Trump. The “triangle of terror” Bolton warned of in November 2018 seemed to essentialize the fundamentally dangerous notion a Latin American region ripe for instability. But it may have also been sheer coincidence that alliterative force of a rather pointless if powerful polygon was a powerful cartographic conjuring of a strategy of national defense, not located in the Northern Triangle, or the former Triangle of Terror where ISIS cultivated troops, but a new borderless triangle of even allegedly even greater danger–a triangle with a rich political genealogy from the Cold War.

Bolton’s adoption of the rare tired stock term of a triangle seemed to shift attention from the other Triangle of Terror, located when it was most recently in the news on the Afghan-Pakistan border, the very site from which negotiations have been announced to start to withdraw American troops. It may have been sheer coincidence, but Bolton seemed to shift attention from a triangle in the Middle East where American troops had been long stationed and that had been a hide-out of Osama bin Laden and Taliban fighters, as if by the powerful abilities of the friction-free nature of GPS–

–to a triangle that was closer to America’s own sphere of influence from the triangle of Peshawar, Quetta, and Kabul, from which the US was busy extricating itself. Bolton’s November speech was quickly taken, one might remember, as defining the intent of team Trump in relation to focus on a new Axis of Evil, adopting a hard line in Central America as sphere ripe for intervention–“This is not a time to look away. It’s a time to increase pressure, not reduce it,” Bolton announced–and the recent exercise of economic muscle to bolster American refusal to recognize the self-declared electoral victory of Nicolás Maduro, and to declare the legitimacy of Juan Guaidó as President of the nation, demanded a map to concretize the global geopolitical stakes that Bolton and Trump were ready to commit to Venezuela, although the map before with Bolton spoke revealed few of the roots for the focus on this new Triangle, but rooted confrontation with Maduro’s claims to legitimacy in the defense of democratic liberties.

Bolton cast the region as a geopolitical battleground for American interests in stark and rhetorically powerful alliterative terms. He openly opposed the United States to a “Troika of Tyranny”–a term that lexically hinted at a vehicle driven by Russia, but wasn’t the 2016 Presidential election–and almost openly evoked the chills or breezes of a new Cold War, with its division of the world to spheres of recognizing two possible Presidents in Venezuela in ways that expanded an electoral map of one nation to spheres of geopolitical influence–if not alliances–expanding in bizarre terms an electoral map to the world to show that it had global consequences–as if global power dynamics were as simple as an electoral map.

The infographic seems to advertise how much “other countries” had at stake in who was Venezuelan President, keeping mum as to why they did. It helped that Bolton looked the part of an inveterate Cold Warrior. And one could not but recall the openly proprietorial terms of last November, when he announced “Cuban military and intelligence agencies must not disproportionately profit from the United States, its people, its travelers, or its businesses” but pointedly attacked Venezuela by imposing sanctions on its gold, and attacking the “triangle of terror” or “troika of tyranny” perhaps metaphorically tied to a Bermuda Triangle, redolent with weirdly alchemical associations of unknown dangers near islands on the high seas–

–as if one could pretend that the declaration was about the rocky shoals of securing needed democratic reform and less to do with oil revenues and resources, as with the defense of democracy.

The transposition of the polygon of a triangle from Afghanistan to the hemisphere was close to a notion of hemispheric dominance, if it also turned attention from a long war in Afghanistan to a closer, seemingly more surgical, winnable military confrontation. The map affirmed the need for using economic muscle by seizing income from oil as a way to undermined as a Socialist dictator, however, whose socialist government was corrupt and based on cronyism, linked in the global map to authoritarian governments in Turkey, China, Russia, and Iran, and their allies, linking an argument of hemispheric dominance to broad geopolitical warning of the consequences of failing to recognize Guaidó as being Venezuela’s legitimate President in American eyes.

Evan Vucci/AP

Maps often lie, as do infographics: but the international magnification of the lack of legitimacy Bolton had been preparing to declare for some time came not only with trappings of objectivity, but with a not so coded message, that might be the true legend of the global divisions in the infographic, and was the major social media take away: a proposed movement of US troops whose removal from the Syrian and Afghan military theaters was in the process of being negotiated by the Secretary of State: the image, unintentional or not, immediately raised fears and concerns about American military plans and sent a shudder in global media.

While it may have been sheer coincidence that the metaphorical migration of the triangle of terror from one theater of global confrontation to the next was occurring in Bolton’s rhetoric and was mirrored in the imagined frictionless switch in deployment of soldiers in the legal pad Bolton displayed to television cameras–

The mobility of the metaphor and the military seemed to echo the new logic of the Universal Transverse Mercator map, where territorial boundaries and sovereignty have far less prominence than specific sites of dispersed geographic location, and imagined transfers of military power could be a frictionless motion in space.

The infographic provided a sort of parallel world carved up and divided by entrenched political interests but whose alliances helped sovereign boundaries to recede similarly. The global two-color map almost made it difficult to understand that he addressed Venezuela–the topic of his Press Briefing in January, 2019–save by the legend identifying red as “Maduro” and blue as “Guaidó”, elevating each man who had claimed the presidency as holding a global constituency, and dividing the globe to magnifying the geopolitical centrality of the Venezuelan election. In the early February State of the Union, Donald Trump elevated–behind the rubric “Abortion”–the pressing concern of Venezuela immediately after “National Security” and “North Korea,” in ways that similarly monumentalized the question of recognition of the future president of the nation, under the rubric of “never apologize for advancing America’s interest, moved from the Border to “National Security” and withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, a historic arms control accord of forty years in standing–with the commitment to “outspend and out-innovate” all other nations in weaponry–to North Korea and Venezuela, regions that were almost designated as areas of future combat.

Trump’s pledged to the union in a mid-February address to “stand with the Venezuelan people in their quest for freedom” against unspecified enemies, but targeted dictators tinged with Socialism. The gripping evocation of a struggle against “the brutality of the Maduro regime, whose socialist policies have turned that nation . . . into a state of abject poverty” may have foregrounded the prominence of Trump’s interest in targeting Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Occasion-Cortez as Socialists, in order to taint the Democratic party. But it was also a crisis that recalled how John Bolton, his new National Security Advisor, had conjured a new danger for the United States’ geopolitical position, independently of nuclear disarmament treaties, but which evoked our historical need for intermediate-range missiles to protect domestic interests.

The role of Maduro in Venezuela has been disastrous for its citizens, to be sure, and mismanagement of natural resources by the state demands attention: But much as Trump distorted actual policies by targeting the “Socialist regime” of Venezuela in a speech marked by excessive flag-waving, patriotism, and rally-like chants of “USA, USA,” the prominent place of map before which Bolton spoke distorted the situation, by literally taking our eyes off of the ground. The map obscured the flows of refugees from Venezuela and the humanitarian crisis in South America, as well as access to the vast oil reserves lying beneath the Orinoco River basin’s Belt. The extensive reserves to which America has limited access is mapped by USGS, but was left tacit in the American declaration of sanctions, but motivating an abrupt change in returning attention to the Western hemisphere for the National Security Advisor. And the assumption of Venezuela as OPEC Presidency, as much as the defense of democratic principles, made the clear ties of National Security to the preservation of access to and production from the Orinoco Reserves–shown below by PDVSA–and the truly globalized investment in the fields shown below, estimated to include three hundred billion barrels of bitumen–the black, viscous, organic “sludge” that contains petroleum–in what are estimated to be the largest reserve on earth, involving multiple international players–from Statoil of Norway to ExxonMobil to Chevron to BP, but also CNPC of China and TOTAL of France, as well as even if the private ownership in the Orinoco Belt was ended in 2007 by Hugo Chávez, whose Presidency haunts the current crisis. But although nationalized in name, the project of oil extraction are only majority owned by he vast majority of bitumen remains too deeply buried for surface mining–some 88-92%–by Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA)–creating a site that was used by Chávez to finance social reforms and projects, and created revenues of $30 billion annually in 2011, making Venezuela a sort of bit of an economic bubble in a globalized world, tied to international markets for carbon and oil, and making Venezuela a “hidden” global petroleum power, estimated to have hundreds of billions of barrels of oil.

The international ties to projects of extracting bitumen and refining oil in Venezuela–which produced about 2 millions of barrels a day in 2015–estimated to have far more technologically accessible reserves. The decision to amplify the level of rhetoric used to isolate Maduro and acknowledge Guaidó as President surely has close ties to the assumption of increasing attempts of national oil and gas company to reroute its oil supplies to Europe and Asia, as members of the Maduro regime told the Russian news agency Sputnik, not only responded to the sanctions, but undercut the Venezuelan crude that usually flowed to CITGO refineries in Texas, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Illinois which made access to crude that lay in Venezuelan territory a national security question–as Oil Minister Eulogio del Pino tweeted hopes to “continue consolidating strategic alliances between PDVSA and Rosneft” in November, disturbing images of hemispheric dominance, as well as undermining American energy security.

.

Bolton’s–and Trump’s–description of Venezuela as an ideological struggle is all one sees in the two-color division of the globe that almost heralded hopes for a return to a Cold War where maps were understood primarily as a global battleground, recalling the days at which a vertiginous sense of power in postwar Europe led us to map exchanges of nuclear missiles, and imagine apocalyptic scenarios where the world was divided by global war–but a global war that seemed to really be about American interests on access to energy reserves, hiding behind the scrim of a ratcheted up rhetoric of democratic legitimacy.

The economic crisis in Venezuela is both tragic, and an acute crisis of humanitarian scope. But the global map seemed to reduce it into a global confrontation of two blocks, if not a crisis of global consensus about representation and political legitimacy, that seemed to hollow out the term of democracy of its content: despite national sovereign division in South American, the sharp divisions of the blue of North America and most South and Central American nations described inexistent international blocks of consensus. What seemed a legitimate record of global divisions about the crisis the legitimacy of the Venezuelan government to lay claims to Venezuela’s rich reserves of oil. Without acknowledging the political or economic actualities in the South American nation, the map hinted at a global crisis, its stark red v. blue color-scheme reflecting the offers of Russia to restructure the debt of Venezuela’s oil and gas companies, and China to lay claim to a stake in Venezuela’s oil, by asserting the reserves to lie within America’s hemispheric interests, and equating those interests as lying with America’s National Security.

As if to bolster Guaidó’s claim that he is backed by the democracies of the world–in ways that nothing better than an infogram can attest–

(Paul Dobson / Infogram.com/February 6, 2019

The map before which Bolton spoke has become a topic of recurrent interest, as the nature of the global divide has been parsed and examined. The divide, this post argues, was less an informative one–deisgned to generate debate–than to paper over the situation in Venezuela’s political crisis as a question of alternative candidates for President, treating the contest as an election, and using the colors of an electoral map to suggest that the election was conclusive, and the legitimacy of Guaidó reseted on clearly ideological foundations.

Bolton spoke at the White House briefing before a map revealing a broad global divide ostensibly about recognizing Maduro’s legitimacy as Venezuela’s President but that hauntingly recalled the geopolitical divide that was firmer than many since the Cold War. It provided an image of the Cold War as it was seen from Washington, in some way, as if ideological divides that are clearcut still maintain legitimacy in a globalized world. The infographic on two screens seemed to affirm the broad global consensus of questions of the legitimacy of Maduro’s government, as if this justified the decision to block access to all property located in the United States of the national oil and natural gas company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), place its assets in escrow, and prohibit American citizens from paying the company directly for access to unrefined or refined oil assets. But the “press briefing” was also a transformation of the White House into a new newsroom of sorts, that exposed the illegitimacy of the Maduro government through a map that tied the United States to the defense of democratic principles–coded in blue, with other democratic allies, in opposition to “reds” linked to Socialism or Communism–China, and Russia, even if it was not Soviet, but also some questionable allies–that reinstated the for-us or against-us global space to make a point. The disclosure before this map of a threat of sensitive statement that echoed a bespectacled Bolton’s assertion that “all options are on the table” provided a powerful infographic that tied Washington to an image of legitimacy, even if the awfully crude map lacked legitimacy to orient American viewers to global affairs.

The new global imaginary that Bolton promoted as he stood beside U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin painted a global schism as the consequence of Maduro’s declaration of his victory in a second term as President, as a violation of that nation’s constitution–and as standing in violation of the Venezuela’s constitutional elections–but was as much a response to the defense of a restatement of American economic sovereignty in the Western hemisphere, a phrase going back to the turn of the last century, if not the Monroe Doctrine, but which gained new currency in the Cold War as issuing from the Dept. of State, and as a question of national security rather foreign affairs, by tactically magnifying the geostrategic role of the Venezuelan election, rather than offering evidence of a constitutional argument about sovereign legitimacy. The question of sovereignty seemed intentionally blurred, as the Secretary of the U.S. Treasury took questions about sanctions against a foreign state-owned oil company, currently OPEC chair, whose assets were being frozen to promote democratic legitimacy, but in fact to strengthen America’s hemispheric dominance.

This time, the map–whose stark divisions into blue and red blocks suggested a map of American alliances, echoing an imaginary of detente, rather than legal rights–seemed to place the defense of denying the flow of economic goods from American territory as a globalist argument, by reframng the issue of constitutional rights or legality in globalist terms that preserved an image of American dominance within the color scheme that it divided the world.

And National Security Advisor John Bolton, who in less than a year in the Trump administration has become an advocate for military interventions in both Iraq and Iran, used the briefing before a map to raise rather openly the possibility of a military resolution of the crisis over the Venezuelan Presidency, as the Commander of US Southern Command, General Mark Stammer, is set to meet the Ministry of Defense of Venezuela’s neighbor Colombia, and Maduro has conjured fears of a “coup” driven from the United States. But the fear that the invitation of American oil companies to organize the refining and extraction of Venezuela’s abundant crude reserves after the January 23, 1958 Democratic uprising, just before the Cuban revolution, sent shock waves into the United States, pushing the Trump administration rather precipitously into a search for infographics that could substantiate dangers of infringement of its hemispheric interests and geopolitical dominance, and to convince the world of the danger of Maduro’s disenfranchisement of elected members of the Congress, and the lack of legitimacy of a regional vote that supported Maduro’s government against a fractured opposition–and led to the invitation from Russia to restructure the state-owned oil and gas company’s massive debt, recasting the struggle about the government’s legitimacy into new global terms.

The colors on the global map reflect, to be sure, the contested results of elections in Venezuela, where compromised elections had produced the heavily disputed endorsement of Maduro’s Presidency just last May. After an offer from Russia to restructure the massive national debt in November, 2017, Maduro declared new elections in May 2018, which the opposition decided not to recognize, and which polls suggested he wouldn’t win, but in which he was victorious–coincidentally at the same time thatJohn Bolton gains the portfolio as director of the Trump NSA.

Familiar blue v. red electoral maps were used to describe the votes of the Great Patriotic Pole and opposition Coalition for Democratic Unity that were recast suddenly in global terms in late January in Washington. Socialist Maduro affirmed independence in his inauguration, and in rebuke Parliamentary President Guaidó won immediate support from Donald Trump after he declared himself Interim President and leader of the nation and of oil company, precipitating a powerful infographic to be devised in Washington that oriented audiences to an electoral map in global terms. But for Trump–and for Bolton, who cast the election as a question of National Security–the global divisions in globally strategic terms.

Trump’s segue in his February 7 State of the Union from the INF to Venezuela, included a transition about North Korea, but suggested global imbalances that any obscure the question of access to petroleum reserves in Venezuela, and the deep, implicit question of whether the American military should or would be used to guarantee access to Venezuelan oil. In ways that must have crossed Bolton’s radar, but have faded from most public comments, Maduro when he pledged to decouple the pricing of Venezuelan crude from the dollar, use of non-dollar currencies as the Chinese Yen for Venezuelan oil, and seeking to cut oil production to “stabilize” oil prices–and entertaining the cryptocurrency Petro, based on the five billion barrels of oil found in Field No. 1 of the Orinoco Oil Belt–possibly less than a quarter of Veneuela’s considerable total oil and gas reserves, whose accessibility to the American economy has suddenly become increasingly tenuous.

The events tied to the assumption of the Presidency of OPEC led to ‘slow coup’ of January 23–the anniversary of the overthrow of the Jiminez dictatorship by Venezuelans in 1958–as opposition politico Juan Guaido auto-invested himself with the presidency with broad American support, followed by a chorus of right-wing governments in Latin America, including Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro.

The result was to pretend that the elections which the opposition party had boycotted last May could be cast again as an electoral map, this time not involving Venezuelan votes–or the self-determination of the nation–but symbolically recasting the election in terms of a global map. Even as Maduro offered to negotiate, he bristled “The presidential elections in Venezuela took place, and if the imperialists want new elections, let them wait until 2025,” perhaps reacting to the provocative recasting of the national elections, whose legitimacy has been questioned by observers, in ways that led Bolton to take to Twitter to threaten “serious consequences for those who attempt to subvert democracy and harm Guaidó”–as if he were the victor of an election. Bolton had escalated attacks on the “legitimacy” of Maduro from mid-January and the “illegitimate claims to power” of the Venezuelan “dictator” as abrogating the “a government duly elected by the Venezuelan people” and democratic practice. But the stark divide of the global map seemed to resist any discussion of negotiations and affirm the United States’ ability to shift troops from Afghanistan to Venezuela’s border immanently–while preserving something of the illusion that the “blue” votes for Guaidó would be affirmed by American muscle.

The gruff determination and stoniness that registers in Bolton’s face as he sought to communicate the divisions of the world that potentially lay in the failure to affirm America’s recognition of Guaidó bled far beyond the defense of democratic principles, and seems to have threatened to cast more than a shadow over Europe. Bolton’s slightly veiled message of national security seemed, in classic America First style, to cast a shadow over European allies, here symbolized by the actual shadow that his pensive head cast on the United States’ traditional NATO allies.

Was Bolton in the act of forging global divisions of a new Cold War, military detente and hemispheric dominance, sneakingly if all too familiarly tied to defense and affirmation of democratic principles?

Continue reading

Kim Jong-un studying the flight of the Hwasong-12, which reached an altitude of 1,312 feet Reuters/KCNA (May 14, 2017)

Kim Jong-un studying the flight of the Hwasong-12, which reached an altitude of 1,312 feet Reuters/KCNA (May 14, 2017)