But if the mass distribution of deserts helped the demand for pizza float, pizza offered an unattainable promise of freshness, all the more striking as it rarely depended–in the case of Pizza Hut–on fresh ingredients at all. Is there now an almost rapacious relation between increased access to pizza and removal from food? Before pizza became a sort of proof of concept of Thomas Friedman’s realization realization the integration of global supply chains for manufacturing and services meant that the earth was again flat–indeed, as flat as a floating pizza pie.

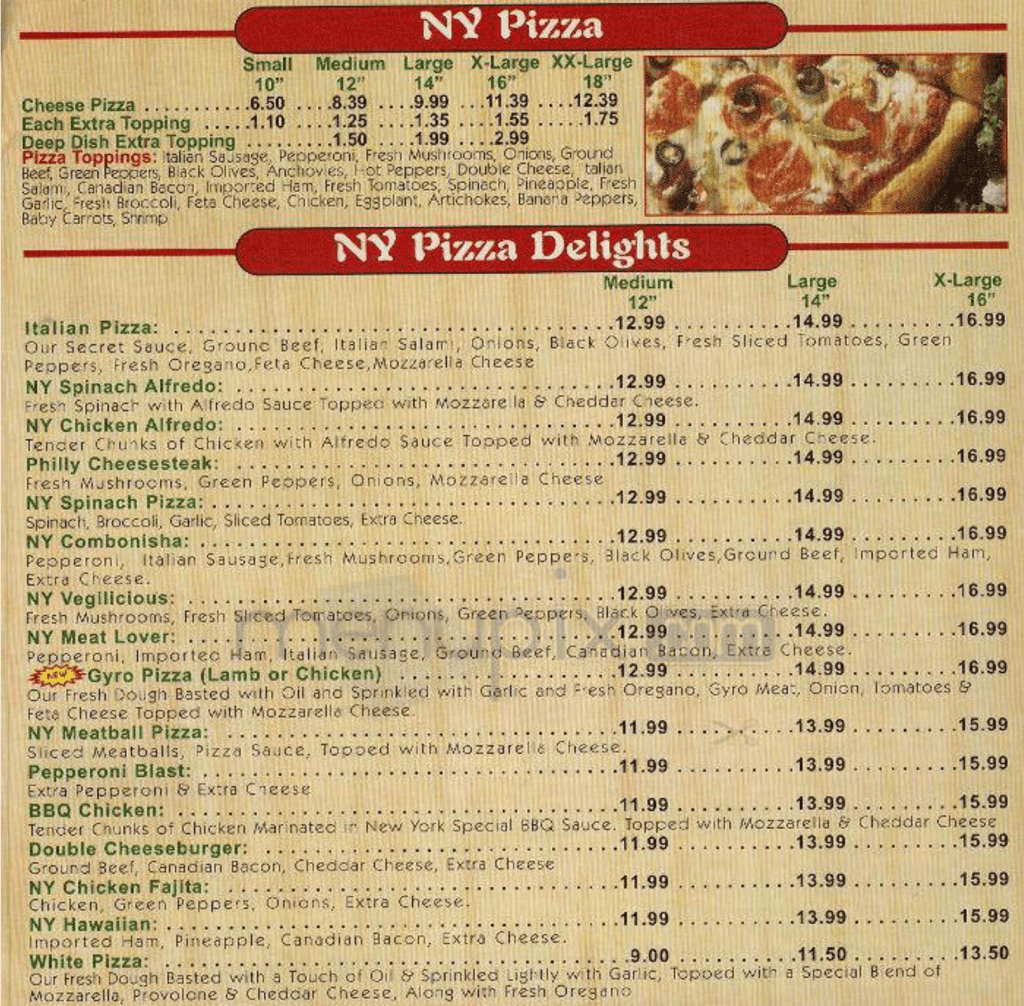

The populism of the pizza still exploited the idea of bonds of social cohesion in simple pleasure, crossing age lines and and even lines of class. There was something quaint in transforming the Italian-American tradition of pizza-making, baked in huge gas ovens worth the initial outlay to turn a heft profit margin with the promise of ready delivery, far from Naples; in Chicago, far from Italian geography save in a romantic identity, captured by the the shop’s tricolor shingle. Was the glue only of shredded mozzarella, or was it in the open indulgence of consuming a pie whose chewiness by freshly spun dough provided a satisfying informal fare at all hours of day? The frequent identification of the southern provenance of pizza making in towns as Chicago suggest a native food, hardly linked to its old place name.

Chicago, Illinois Cragin Spring/Flicker

While once a local art of urban face-to-face exchange, pizza has stretched to become a globalized food. The global and domestic popularity of pizza has been greatly accentuated of course during the recent pandemic and the expansion of order-in foods. But the promotion and absorption of pizza by integrated delivery platforms and food preparation assembly-lines of multi-nationals dilute culinary authorship or proprietary relation to pizza so that the crust–or the “stuffed crust” introduced Domino’s in the 1995–promising delivery within a half hour. Television ads of Donald Trump making a preposterous deal with a pizza man at his door in Trump Tower, as if to prove he was indeed an everyman, have been replaced by unmanned drone delivery of pizza promoted global access to pizza: is this a modern riff on bread and circuses, proof that the market met contentment in a promise of umami satisfaction?

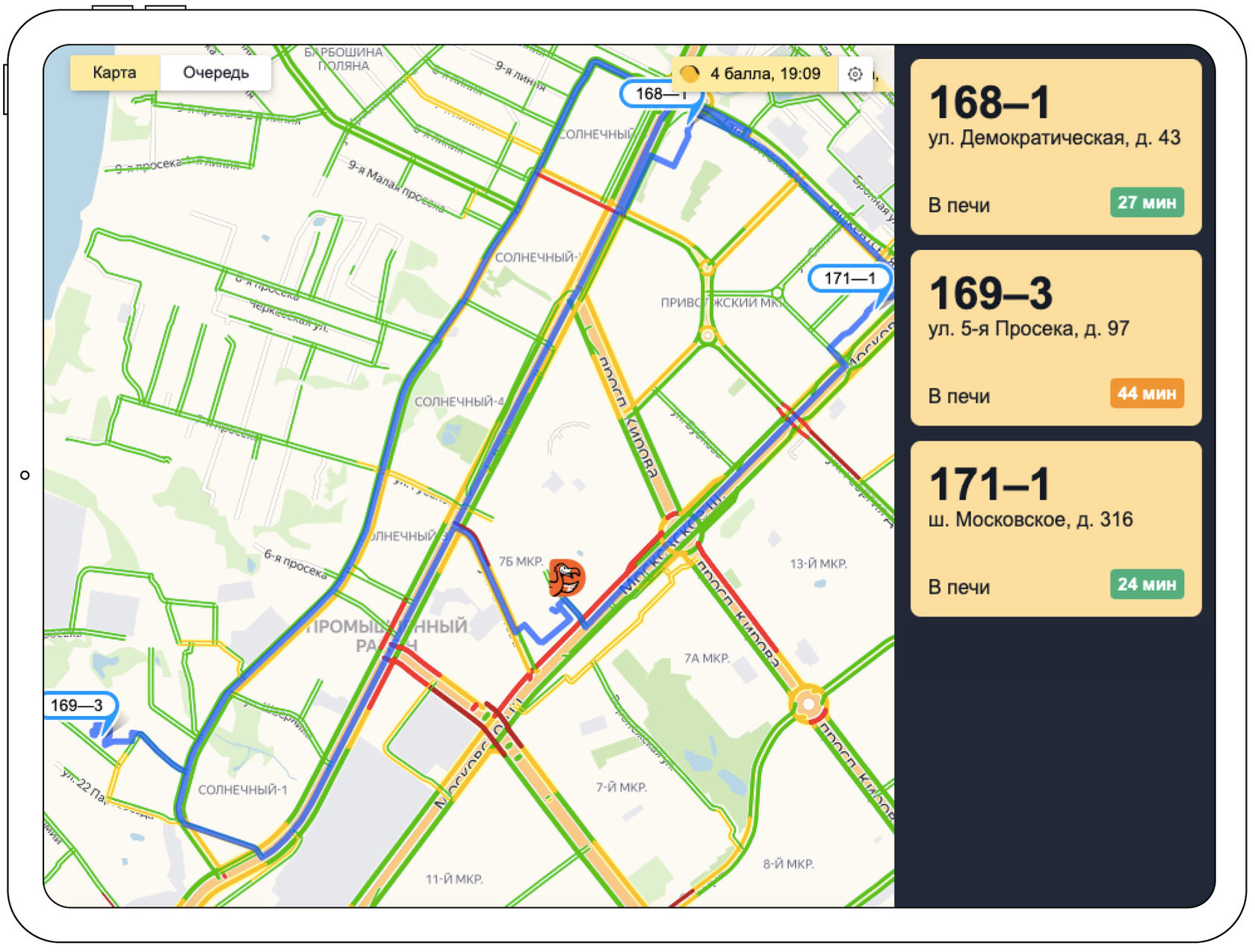

Pizza has morphed from a comfort food so much at the ready that might be delivered, fresh from the oven, anywhere not by a “pizza man” since 2015, but by unmanned drones, leaving Dodo Pizza’s Syktyvkar shop in northwestern Russia, which used delivery drones from four hundred stores to cut delivery time of warm pizza across Eurasia, breaking a frontier of “local” pizza delivery for rapid delivery of customized pies and redefining ‘pie in the sky; pizza offered an apt business model to engineer incentivized IS interfaces for record delivery times of piping hot pizza pies.

Even before drone delivery promoted mass-catering of pizza to “untapped markets” in Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Romania, Slovenia, Lithuania, Estonia and Nigeria to flood airborne pizzas into untapped markets, the success of designing the startup’s proprietary platform for directly franchising pies, the scope of pizza making as it has been metabolized in multinationals’ food distribution networks on a global scale, transforming pizza-making by Taylorist models of an assembly line out of Moscow in the new lingua franca of pizza making of distinctly stateside origins.

The transition to a drone-delivery will not be limited to pizza, but the five-kilo limit of transport promises to expand the frictionless travel of pizza, in what might be called the Flat Earth theory of pizza making across a spatial network designed for the intent of “bringing delight” to much of the old East Europe–Romania, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Latvia–with aims to soon expand to the United States.

It may be a response to the global expansion of “Dodo” reached as a multinational delivery franchise by 2016 may well have so shocked UNESCO to hear with new interest the request Neapolitan pizzaiuoli succeeded to certify pizza-making as an intangible heritage based in Naples by 2017, dropping a pin in the Campania, with visible car not to pronounce judgement on superior quality. The “intangible” nature of a hand-held food ran against the diffusion of pizza as the privileged food of heterotopic spaces–sports stadiums, viewing parties, school board meeting, airports that Enzo Coccia calls non-relational, and not concerned with identity. Yet it was in America that pizza gained its identity as a monument of Italian culture, in no small part as it was remarketed as an American food, able to move smoothly from the category of “ethnic” foods to a family table, accepted as an occasion of caloric indulgence that was good for one anyway, and promised a “fresh” taste, even if its main ingredients were clearly not.

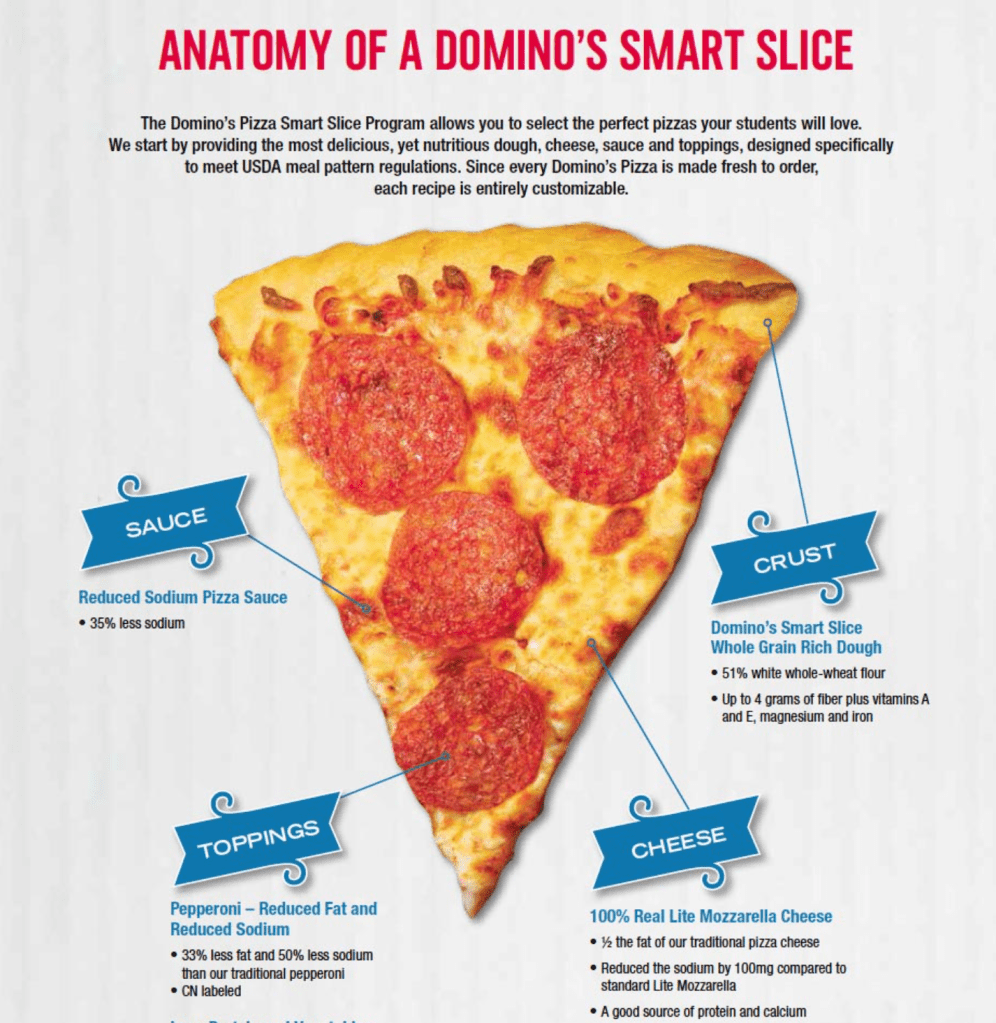

2. The smoothness with which the pizza entered the American table, and indeed the notion of family style foods, accelerated as it became in recent years a way of satisfying consumers and repackaging resources–cheese, in particular–subsidized for a large market, where multinational agribusiness ConAgra won protections to limit the amount of tomato paste needed for pizza in school lunches, after winning the approval of fries in healthy school lunches. The image of pizza as a fresh food–or the remaking of pizza as a vegetable, and as a viable balanced meal for a growing child, wether in the somewhat healthier form of fortified and vitamin enhanced English Muffins for mini pizzas, disguising their nature as caloric bombs. The friendlinessServed an easy go-to at all hours, pizza has been treated as a school lunch, used as a release from the requirements of serving or eating vegetables, anticipated as rite of “pizza Thursdays” as well as the most mobile good possible, delivered to campaign offices and businesses after hours round the clock, promising a level of freshness late into the night. The global availability of pizza increased offering of a deliverable food not only eminently mobile, but able to be had at hand wherever one wants?

A growing demand for home delivery of pizza had long preceded the Coronavirus pandemic, but by offering “hand-tossed” pizza on an unprecedented global scale, the pizza pie grew in popularity as it provided a warm balm for displacement to dull its discomfort, and globalized as we were conquered by the need for readily available inexpensive food, that remade the local art of pizza making for global availability, while all but eliminating overhead. Raised on the carnivalesque release from vegetables promised most American school-children in “pizza Wednesdays” and “pizza Fridays,” a long hallowed rite of school lunch; confusing pizza with a flat earth might well take spin from the category confusion of a false formal analogies, beyond classification of ketchup as a vegetable. Soon after Pizza Hut promoted the pizza as “healthy” food–and the U.S. Government food agency, and provided pizza identified as compliant with all USDA guidelines from the 1980s, about when Ronald Reagan insisted ketchup was a vegetable–and, since 2010, got a boost from Dairy Management to introduce pizzas with 40 percent more cheese for school lunches through a $12 million marketing campaign that augmented its cheesiness for dubitable ends in an era when Americans eat more cheese than ever–33 pounds a year, nearly triple the 1970 rate–furnishing more saturated fat than any food. But as much as we laugh at the idea the USDA would recognize ketchup or other condiments as vegetables in the School Lunch Act of 1981 as a classic budgetary overreach that turned nutrition standards to run against common sense, as legislation on childhood nutrition that set two tablespoons of tomato paste to guarantee pizza as a vegetable gained limited notice in a nation convinced pizza was a balanced meal.

The image of the satiety of pizza fit an economy. ofcutting corners, and indeed of expanding the percentage of processed foods in American diets, and addicting them to the processed cheese and refined flours of pizza as a readily made and protected food. Does not the promise of plenty not exist as the flip side of scarcity? Although the tomato is technically an import–deriving from the New World and originally South America–the force of pizza-making combines local and global, in ways that, aided by the complex geography of food production and the engineering from the 1940’s of “pizza cheese,” has almost created a new of local and global, increasingly difficult to disentangle either in space or in time. Yet the flat disk of processed pizza is almost the perfect image of the flat-earth theory of globalization, or the heightened flattening of what was once a globe that “requires us all to run faster in order to stay in place” that has allowed the explosion of lopsided wealth differences as a byproduct of global supply chains of manufacturing and food services that conscripted the leaders of the world’s largest economies into the success of a growing flattening of frictionless globalized economic exchange. globalization.

Is it coincidence that pizza is the metaphor of choice for preparing GIS layers in maps? Pizza seems an apt universal analogy for the layering datasets, metadata, legends, fonts, colors and for the ready consumption, the GIS-as-pizza metaphor accommodates a degree of personalization. Pizza’s very diversity or “variety” has not only mirrored but furthered its globalization, breeding the sort of cross-fertilization by its engineering local arrangements of toppings, to make pizza such a powerful but non-arbitrary metaphor as a “personal and global favorite.” At the risk of belaboring, the place of borders is all but erased in this image of the trans-national pizza, as brand subsumes place erasing the local–and local knowledge–and the place of place the rooted nature of pizza-making as an art.

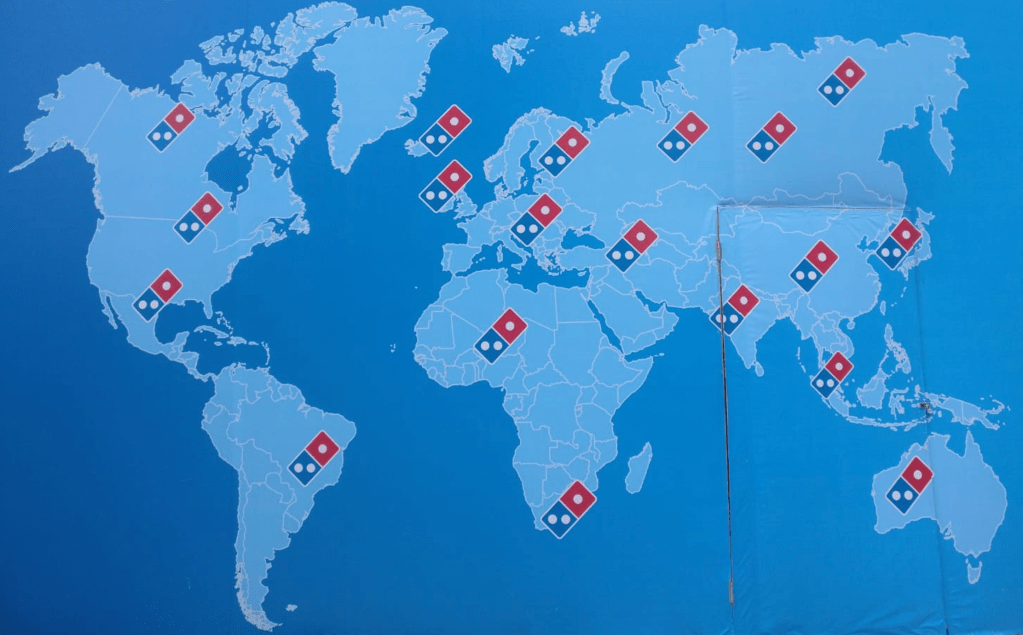

Map Painted to Celebrate Domino’s 200th Store in China in Shenzhen Province–its 10,000th globally (2019/r/mapporn)

Perhaps the map was preaching global satisfaction in an easily prepared food, If Dominos posted a bad map to trump the opening of their two hundredth store in mainland China–and 10,000th globally–maybe that was the point. The poor projection the multinational chose lacked clear correlation to a base-map and readily sacrifices global curvature or cartographic iconography to a flat earth blanketed by logos, whose color scheme echoes its corporate palette and asks the viewer recognize an image of global dominance. Without bothering to chart locations of stores, it boosts the “global growth momentum [generated] by opening new stores every day . . . bringing the best carry-out and delivery experience.” So preened the Executive Vice-President of Domino’s International in an unabashed display of unchecked corporate pride, far less concerned with a relation to space, than an ubiquity of brand, treating the superceeding of place as a corporate milestone.

The karmic convergence of world and pizza-making dispensed with actual locations–that would be incredibly busy, if presumably available from their own corporate data–but affixed a logo atop nation-states where their pizza was present, as if members of a club, in an encomia of the brand’s “global dominance” that celebrates its permeation of eighty five markets as their global sales volume surpassed that of any other pizza company, by 2018 beyond $13.5 billion, more than make a case for their pizza’s popularity, demonstrating the global appeal of the uniform pizza pie. The wallpaper effect of the painted map celebrating “market dominance” didn’t demand spatial specificity, or a respect of global borders: the brand bridged borders, its logo intentionally placed across national borders, bridging Mexico and the United States, or the Canada-United States border, trumpeting the trans-nationality of the multi-national. If pizza once claimed to be local, or wedded to independent stores, the story map of pizza is definitely global, and conveys the overwhelming of stores of independents across America and in the globe.

Is it a coincidence that the map recalls an almost missionary zeal for baked pizza or online ordering? If the painted map implies a sort of missionary zeal, perhaps informed by the zeal of Domino’s owner, Thomas Monaghan, after selling over a billion dollars worth of pizza in the 1980s, and opening three stores a day by 1985, sold the chain, and, viewing the pizza earnings as “God’s money,” used it not only to build Catholic cathedrals to advance the Catholic faith, but even founded a religious university, Ave Maria, more traditional as an exponent of faith than Notre Dame and American Catholic universities, that was dedicated “to explicate the truths of faith” of Roman Catholic Catholicism in Naples FL,–a toponymic coincidence?–to combat “evolving societal propositions or practices” like abortion, contraception, same-sex marriage, fetal research, and cloning–and beyond faith-based education, suing the federal government for considering contraception within health care. Domino’s made tossing pies to satisfy customers a basis to convert global pizza sales to a network promoting evangelical causes for a domestic agenda.

Have record levels of pizza sales helped promote the globalization of canned tomatoes? The metastasizing of pizza to a global scale was less tied to transatlantic immigration than to the economy of globalization, suspended between a deep desire for the local recipe or style–creating a thin allegiance enduring across space, in this small sample–despite the increasing ubiquity of pizza and pizza ingredients. The pleasure of pizza is in no small part rooted in its claim as a preeminently reassuring comfort food, more than the authenticity of a a style or recipe. The mobility of the pizza in global markets may suggest the removal of a sense of the local effectively increased customer demand for pizza. The expansion of a desire to plant a taste for Domino’s–and a sense of brand loyalty–by a program of school lunches had depended on the ability to sell government officials on a sense of pizza as a balanced meal, rather than a banal food, of protein and fresh vegetables, “compliant” with the National School Lunch Program for American schools, since the 1980s, but customizable for school lunch offerings.

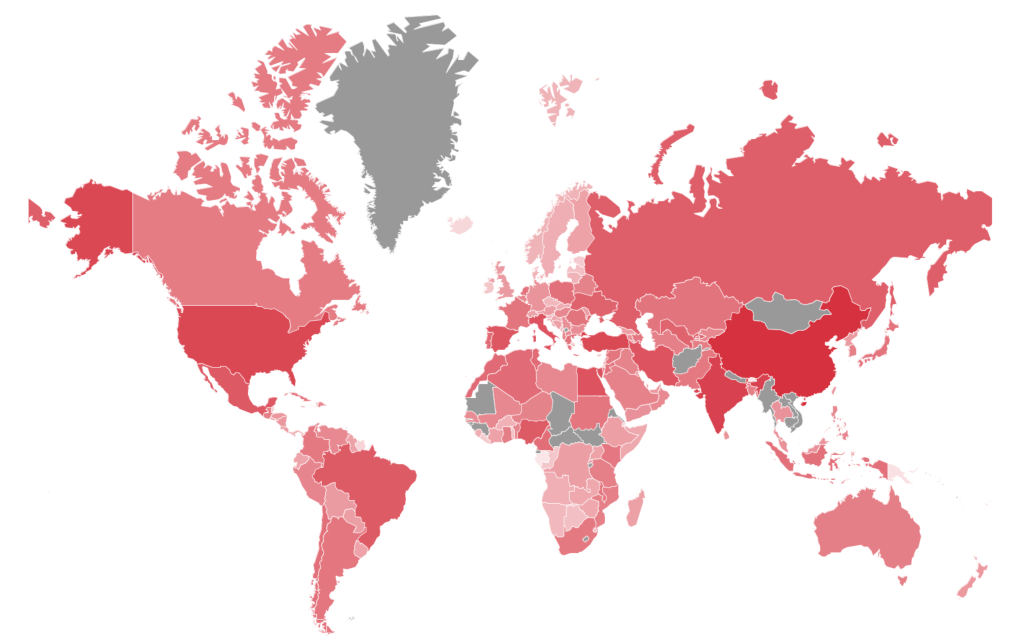

As much processed cheese distanced pizza-making from sourcing agricultural products, the once-local cultivation of the tomato has became global–China’s 60 million tons annually to vie with Italy in tomato production, with Turkey (12 million) and Brazil (4 million) far behind–if Italy continues to dominate tomato derivatives and processed tomatoes–in an atlas of Global Tomato Production of 2020, whose shades of red suggest looking at the world map with a color ramp of tomato juice–

Global Tomato Production, 2020

–plants of tomato processing are perhaps, when it comes to pizza sauce, more suggestive of tastes–

–processing tomatoes for the United States, Europe, and Japan, competing with China just behind the United States in tomato farming, leaving Spain, Turkey, Argentina, and Brazil far behind.

But is the cultivation of tomatoes removed from the minerality of soils able to create the flavor of an actual pizza sauce, or just a watery if red puree? The notion of such a transatlantic migration might be less apt than the spread of a taste for pizza’s distinctive umami, a suitable transnational descriptor for the broad stretching of pizza dough as a platform, able to be enriched by the distinctive smokiness of beef pepperoni, most often manufactured by Hormel, an apparent midwestern concoction of German-American extraction, without any Italian origins, atop the gorgeous glutamates of aged cheese, tomato sauce, and mozzarella, a pairing of flavors compounds enhancing experience, even if it elevates saturated fats and a slice totes over a quarter of your total calorie intake and a third of your total sodium intake. But the addiction of flavor enhancements have give the food global legs–in ways that may not be conducive to global health, and can travel even separately from an actual pie.

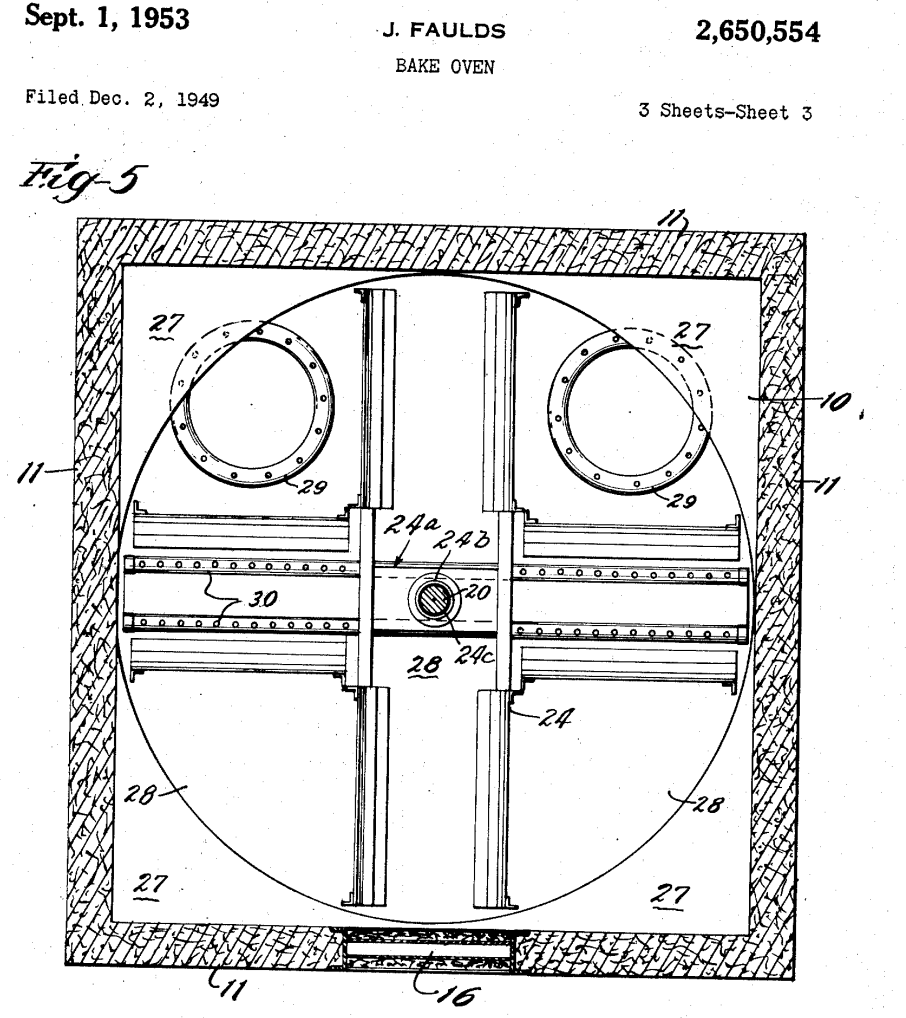

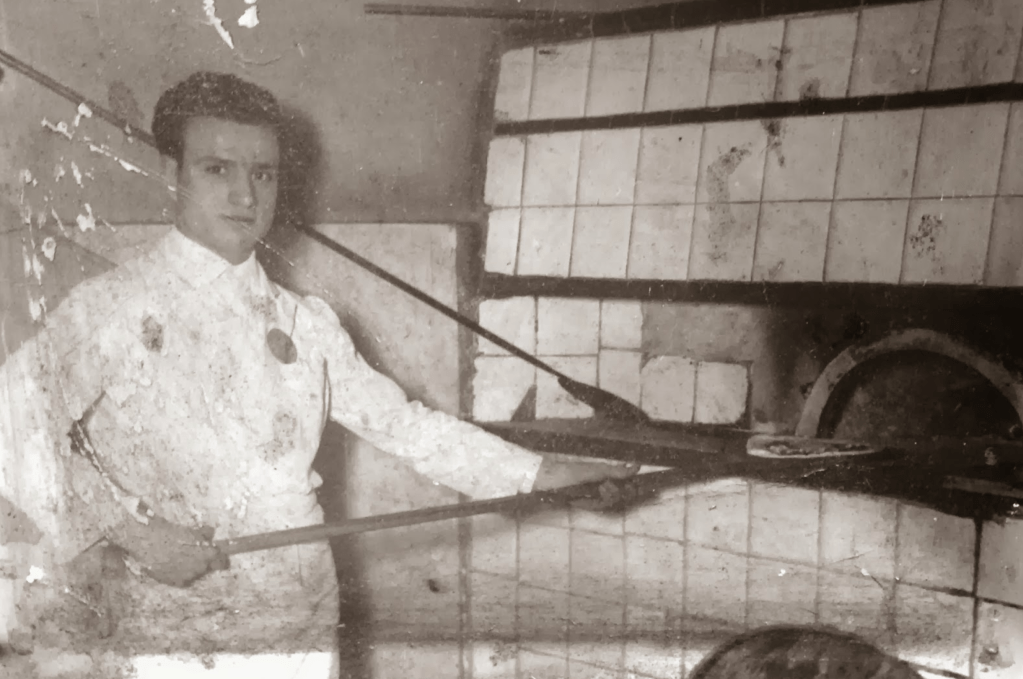

The rise of pizza as a global food on industrial-scale food production of pasteurized cheeses, tomato sauce, and sliced meat or even hamburger, found its final result in the expansion of “pizza-flavored” snacks, few healthy, that dramatically increase the distance between farm to table that claim to sublimate the pizza in chips, crackers, or energy drinks, as flavors distilled by industrial preparation–no matter how far removed they are from the lightness of a crust or the hotness of fresh sauce. Although global breakout of pizza in postwar America depended less on the return of soldiers in the Italian theater of war than the postwar rise of processed cheese, pizza consumption was distanced from the cultivation of tomatoes or fresh cheese–two basic foods to which one had thought pizzas were moored–as subsidized overproduction of cheese encouraged rise of packages of pre-shredded cheese, often coated with vegetable oils. The restaurant industry may not have responded to a “taste” for pizza developed in the theaters of war, but responded to the ease of global export and importation after the war, as some of the founders of the first large importers of San Marzano tomatoes, double concentrate paste, imported from the 1950s with its rich umami; the rise of importers like Cento, got its spin from returning servicemen not in the peninsula, but other military theaters, who took advantage of growing global trade and low tarriffs expanded import lines of tomato sauces and “specialty lines” of Italian imports for chefs in a belief Americans would want them, that changed the offerings of shelves and restaurants in deep ways, preparing a taste for pizza baked in gas ovens, huge ovens not first imagined for pizza but whose in uniformly heated and supplied huge ten foot by ten foot steel walls were so popular among pizzerie from the 1950s and 1960s nationwide and remain treasured for uniformly heating pies on a lazy susans.

Yet it was undoubtedly in the high temperatures of the gas oven whose rotating lazy susan offered all that cheese to melt, and to melt in ways that could be readily reheated, that allowed the easy production of pizza crust as we know it–the defining factor of any pie, bottom line–and that transformed all that cheese to a network of melted shred that offered the pleasurable stretch in its salty strands, and supporting a thin layer of something like oil and tomato paste. patented just postwar, and not at all for pizza, Faulds ovens were the mainstay of the first independent pizza shop, the initial investment that led to a boundy of pizza profits and productions, in which the American pie was forged.

The “taste” for pizza was reborn in the postwar, recent years have seen such increased ease of global distribution and food storage to exploiting umami baked into pies or slices warmed and reheated in rotating ovens for ready consumption to give the taste currency of its own. Dislodged from the material artifact in the market for food tastes, the pavlovian status pizza gained removed it from any recipe or preparation, in global commodities used by a range of multinationals–ConAgra ($11 billion global revenue), General Mills, Kraft Heinz, Nestle and California Pizza Kitchen–a brand conflating local and global, boasting a “California twist on global flavors” and multiple pizza-surrogates that hAve flooded food markets with more and (rarely) less saturated fats from food engineers.

But the global deracination of a longing for pizza from even the preparation of the pie, not always at considerable caloric costs, exploited a longing for taste entirely removed from place, or indeed the art of pizza-making. And it was against the emergence of a global “pizza market” plied by multinationals at global scale, that the local nature of pizza was celebrated. It was a poitn as much about the relation of place to space as about pizza quality–or taste. For the preparation of a dish long purveyed as alchemically transformed cheese and tomato in an oven, served with local olive oil was a site in need of preservation, in danger of being swept by the smooth surface of the global demand for the immediate satisfaction of generic pizza pies–even as they continued to claim a lineage evoking to classic heritages of oven-baked bread, but only to blur the huge shifts in each epoch or “age” of the making of pizza as local making of bread,–as well as a distancing and redefining of the “hearth” as a form of hospitality to break bread.

3. While the global history of the pizza has not been told in full detail, the origin story affirmed a cultural good, when, just ten yers after UNESCO affirmed the historical monuments that crowd the historical center of Naples in the list of world heritage sites, the intangible of the stages of preparing pizza was affirmed as a monument of its own, a recognition that was only really possible after the global diffusion of pizza–and frozen pizza!–in global food chains and multinationals, from Nestlé to Kraft. If Neapolitan pizza provoked a dissonance for consumers who felt pizza was their own, a sense of unfamilairity boosted by the contrast of a calorically laden pizza dripping oily residues of processed cheese or topped with hamburger, sausage, or bacon bits with bubbly fior di latte on a thin pizza crust, elegantly blackened. Did the “origins” story seeks puncture global purchase on a comfort food in cardboard that affords easily accessible caloric comfort worldwide, growing the revenue of a United States market to above $50 billion–4.1 billion pies, giving each American on average more than a monthly pizza pie on average.or a pie, about 25 pounds of pizza per year–or more than Joe Biden was able to put into COVID-19 vaccinations ($20 billion) and rental and utility assistance ($25 billion) in 2021. (One can only speculate how such caloric indulgence in pizza consumption increases to health care costs, with over one in eight Americans eating pizza on a given day–and pizza outlets, more often chains that independents, if not from frozen brands that have exploited assembly lines.)

As if in response, UNESCO certified the heritage of pizza-making as an art honed on selective simple ingredients–water, flour, salt and yeast–from the produce from the local countryside–as Coccia put it, “the excellent produce from the Campania countryside,” even if it was also bought from scarcity. The late-coming acknowledgement of the city of Naples, Italy as a center for the art of making pizza dough to bake with a coating of locally grown tomatoes and melted mozzarella pushed back lightly against the globalization of pizza–and indeed on the dominance of pizza as a global food. While the distribution of global pizza in food distribution networks, frozen form, and supermarket dinners had began long before the 1980s, when it blossomed stateside, the identification was a deep acknowledgement of the compromised position in which its globalization placed 3,000 pizzaiuoli–pizza spinners, bakers, and oven men–in the global network of pizza’s dominance as a popular food in a world of compromised time, pressed work schedules, and fast food, where comfort is sought in a layer of tomato sauce lying under a virtual blanket of toppings nestled in layers of melted cheese. If the spread of pizza, motivated by high profits and increased needs for ready-made food and pleasure, has spread almost ineluctably across a smooth space, as if the world were truly flat, elevating Neapolitan food as a culture of global importance prompted the certification of the local art of pizza-making as an intangible heritage by UNESCO in 2017.

There’s a serious case to be made that the pizza was always global, even if the local production of pizza was once a fundamental part of the pizza–the promise of a freshly baked pie. If the craft of pizza-making was once local, the archeology of pizza-making suggests stages of globalization in which its meaning changed–and evolved by leaps. The first age of this global story might begin with the arrival of a round bread in the periphery of the Byzantine Empire in Naples, “pita,” often eaten with feta cheese, extending to the importation of the tomato as a crop, after the first British sighting c. 1700 in North Carolina; the second stretching from Vico and the first documented preference sailors at Naples’ port had for pizza marinara in 1738, through the emergence of the pizzaiuolo around 1750 and the sale of pizzas from the backdoors of Naples bakeries c. 1825; the third age marked by the mythic conferral of royal preference by Regina Margherita of tomato, mozzarella and basil pizza as her preferred dish, that, acknowledging her sophisticated palate, bequeathed her name to the minimalist dish, c. 1880; before the transition, long subsequent to Italian out-migration, to a fourth age of Italian-American re-invention, circa 1938 but unprecedentedly growing in postwar America, when the growth of expendable income and a demand to feed to-go eating was emblematized by featuring pepperoni as a pizza topping of a proto-fast food, long prior to pizza delivery extending across an increasingly frictionless smooth globe, whose speedy delivery could be virtually assured from a nearby warm oven.

The Neapolitan habit, perhaps seen in Giambattista Vico’s insistence on the equality of verum and factum, saw the pizza as bound in the conditions of its own making, by a process of corso and ricorso. Any survey of pizza’s global history must begin from that process of remaking of scale: but the disentanglement of the broad conditions and divergence of making must be kept central; the current tendency to try to monumentalize where the global appeal of this dish of daily bread began, must be balanced by the process of remaking of pizza from a local to a ubiquitous food. Bracketing the relation of pizza to public virtue, an archeology of the transformation of the broad temporal arcs of the very word “pizza” under the sign of the Neapolitan philosopher. It may be Vico never sampled pizza, but he wrote in 1725 as the pizza emerged as a popular street food. But Vico offers terms to situate the transformations of making meaning within the story of nations, the conversion of pizza from a “sensus commune” in Naples’ fabric was tied to deep cultural changes of globalism, even if it did not reflect population shifts, as it moved from a sense of the transmission of a local art to a global one across four ages of qualitatively different economies of scale.

But if pizza provided a basic activity of making, pizza-makers did so in ways that were hardly within their own control, even if their incomes depended on it and they sought to maintain pride in their craft. For the art of pizza-making, as much as it can be said to exist, qualitatively shifted from the first spread of the urban trade in the port city to a prewar transatlantic passage of outmigration, to a new national diffusion in the food marketplace that was later globalized.

If the four ages of transmission of pizza has moved from human agency of making that were forced to accommodate increased mobility and food industries, before pizza preparation was mediated in the ‘cloud kitchens’ that enable pizza’s global growth–transforming pizza to a truly global food, as transnationals honed sales models of mobile ordering and Pizza Tracker–affirming the illusion comfort was always at hand, even as in-person dining out ended. Despite the cultivation of rather persistent legend of mapping the pizza to waves of transatlantic immigration, and locating the first stores that sold pizza in Italian-American neighborhoods in the late nineteenth century–at times promoting the hiring of Neapolitan pizzaiuoli–as if they were evidence of the arrival of pizza to American shores as an import that was fully made, born, as Athena, but not from Zeus’ head but the hands of the immigrant working on American soil. Despite the importance of waves of out-migration from southern Italy to the United States–and indeed to the Americas–the development of pizza as we know it was more based on American shores, and may indeed have forged a taste in America that became so closely wedded to the currents of the food industry and the subsidizing of cheese after World War II, to take its spin as a local permutation and re-fabrication of pizza that was born fully separate from Italian food, topped with foods–as pepperoni–that were squarely of Italian-American origins. Yet pizza was rarely on the menu of most restaurants, save specialty shops, in the immediate postwar period, even as “Italian style” foods gained status from bechamel sauces to lasagna to mixed vegetables, Italian style. Pizza had no place at the Plaza, for example, unlike, say, veal scaloppini or escarolle–to be sure, quite different sorts of food.

Despite the image of transport that was once associated with the pizza as a taste that was transatlantically delivered, the local origins of pizza were never closely concealed, even if they were long draped in a romance of immigration and respectability. The link in the 1960s between pizza and the cultural monuments of Italy–the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Venetian gondolier, the street-scene in a hilltop castello–provided a cheap ticket to Italian romance, and the conflation of spaces within the parameters of a tasty pie, imagining gondoliers on Lake Michigan, flavors of Sicily, or Renaissance scenes of love worthy of Romeo and Juliet’s Verona in a hilltop Italian fortified town, in an odd echo of what might be called the first jet age, and echoed the travel posters–as if in a hint of a vacation on the cheap–although no travel posters included pizza quite so prominently. But truth in advertising cannot often be expected, and the Italian-American origins of the pizza pie topped with meats was never really ever in question.

The romance of culinary migration rehearsed on pizza containers across America far beyond the east coast created a mythology of direct migration in the imaginary. But pizza gained legs as a to-go food ready for pick up in cars that became an easy prep dinner with which Americans of most all classes were suddenly familiar–the typical fall back for meals kids cooked themselves, bought in supermarkets to reflect a nation of homebodies. Although tempting to relate the transatlantic migration of the pizza as a migration of pizzaiuoli or of the demand for pizza in Italian communities, the small spread of pizza making outside the first cities with Italian-American populations–New York; Boston; Philadelphia; New Haven–is striking, as its distance from the later transformation of pizza as an almost omnipresent convenience food among the new eating fashions of the post-war period.

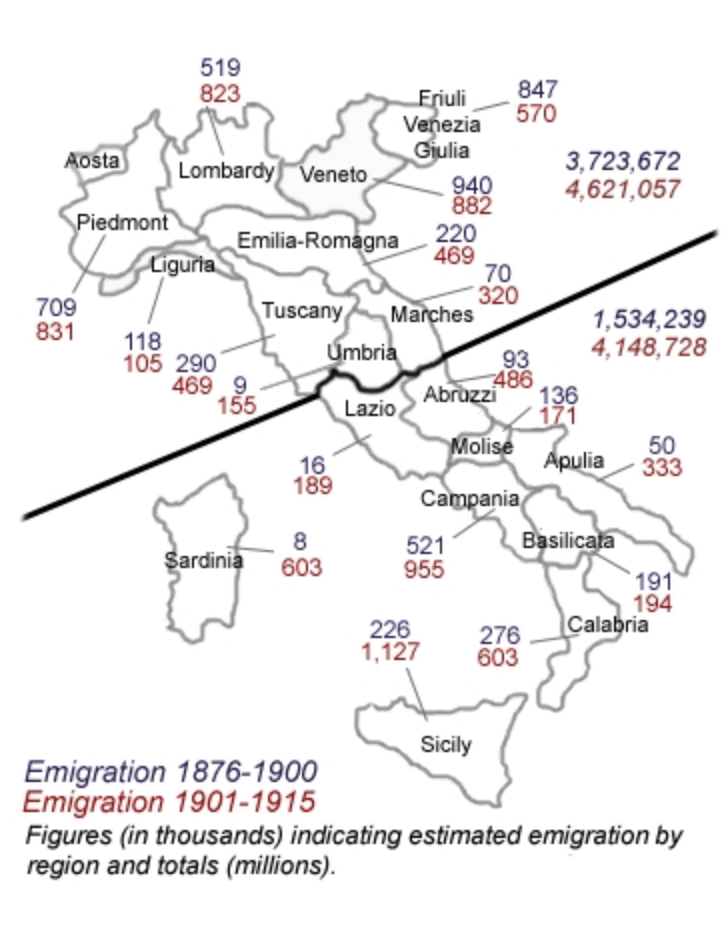

While the outmigration of Italians after unification were mostly to the Americas, the practice of unification–and transferral of concentrations of wealth and capital from Palermo and Naples, largely in the form of gold deposits in Naples to Turin and then to Rome, created a marked acceleration of migration from both Sicily, Calabria, and Campania after 1900–can one really associate the growth of American pizza to this massive transatlantic transfer of population?

Far from being an extraction from a local setting or site of origin, pizza had gained distinct currency in America. It did so both within the American Italian-American community, as a surface that would welcome not only anchovies and tomatoes, but a palette for caloric intake able to field toppings from pepperoni, sausage, bacon, pineapple, to hamburger, a vessel of indulgence that seemed to sanction the ability to eat with abandon at low cost, in an almost cyclical history that transformed the artifact to a good prompted for global preparation and marketing. As much as pizza “conquered the world,” it became a poster child of sorts for global food marketing, less tied to global movement of Italians than the expanding food industries if born in a far-off street life before preorders and pepperoni.

The deep cornucopia of pizza toppings suggest less of an immigration of tastes, than a sanctioning of indulgence, a potlatch of sorts as big as a city or urban environment able to accommodate multiple ethnic foods and absorb them, as a gustatory melting pot, from meatballs to sausage to fajitas to gyros–in a license of abundance that was part of what the “NY Pizza” came to be, able to absorb options from Philly Cheesesteak to Alfredo to Hawaiian, saturating the senses in a moment of edible overkill.