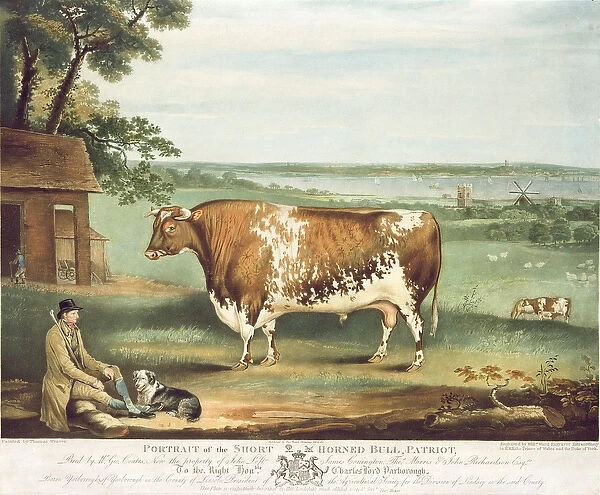

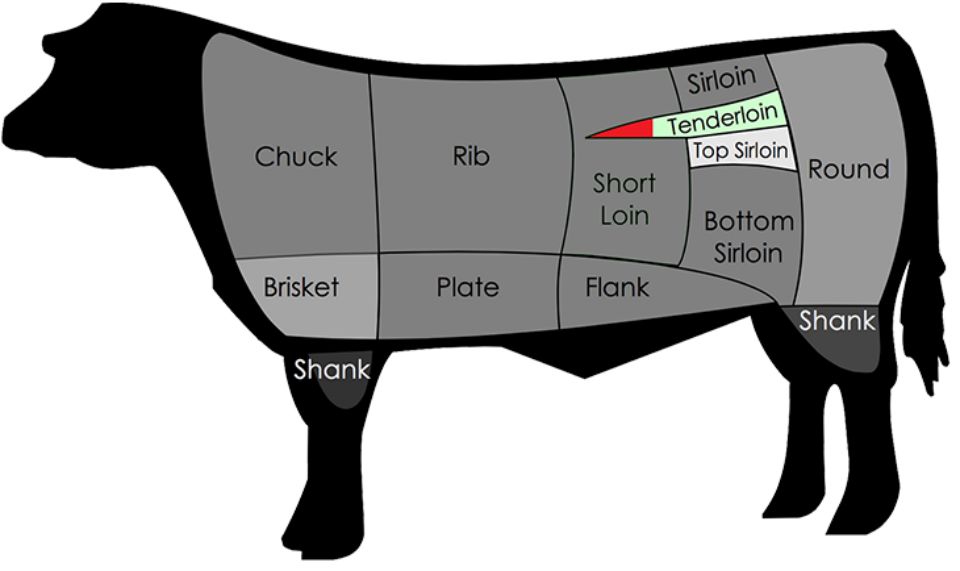

Delineating sectors of an animal’s carcass on the form of a living creature is particularly jarring. It implies a clear category confusion that might be described as either breaching boundaries between the living and the dead, inappropriate, or deeply unheimlich or uncanny. It affirms the double-existence of the cow, and of all farmed animals, for the modern carnivore, perhaps rooted in his new relation to the art of butchery. The neat dotted lines that segmented the bovine suggests it is not a grazing animal, than a diagram of what we are invited to buy at the butchers; its very form invites us to navigate passage from the living to dead animals, performing a doubling of the animal portrayed in its domesticated setting.

For the names by which we map meat serves to socialize our relation to animals through our own increasingly complex relations to the division of the animal carcass. With ever increasing possibilities of refrigeration, the proximity of dining table to slaughterhouse or abbatoir means we map meats in increasingly sophisticated ways,—often flummoxed by meat cuts at a butchers, so that we need a shorthand guide, as a way to distanced ourselves, no doubt, from the increasingly dehumanizing industrial-scale butchery of cows, pig, and sheep. We convert them not only to new terms for our tables and ovens–beef, pork, and lamb, if mutton for older carcasses of sheep–as if seeking the most palatable and polite transformation of the raw to cooked. Gone is the full carcass of the body to be consumed –newly objectified, skinned and suspended before our eyes, to be carved in response to the request of a customer –our meat cuts are prepared for consumption in new parts, to give us an assurance of orientation on the dizzying display of carcasses in the streets sort that one once saw, already on their way to being prepped for your table. While the Paris street is hardly time travel, these hanging pigs invite us to take a long view on the remapping of meat, and consider how we map meat cuts to re-present the parts of animal carcasses that arrive on our table.

Paris Butcher Shop, Barbes

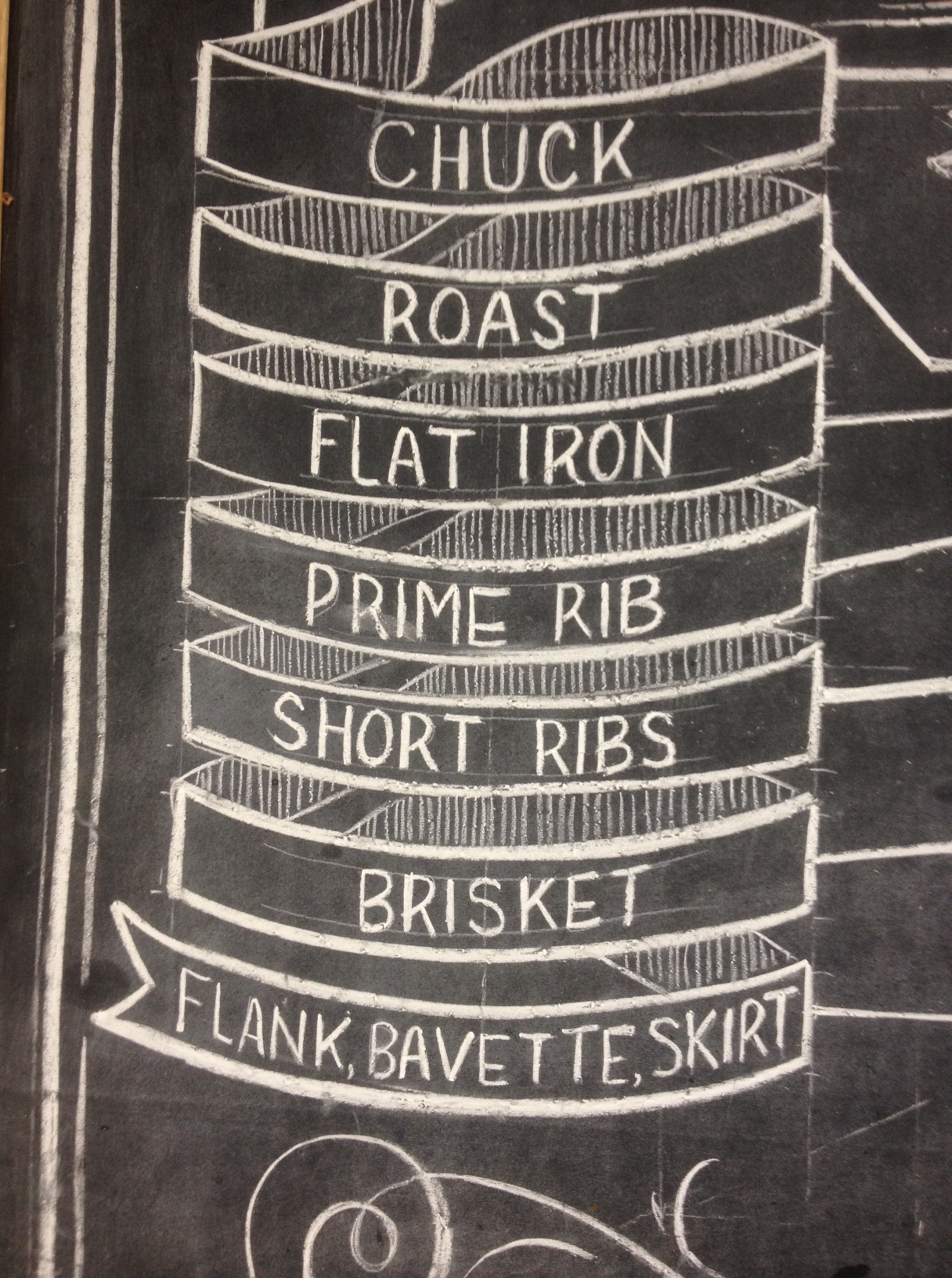

The resurgence of high-end butchery as a sort of urban provisioning has created an often boggling range of select cuts–restoring a concrete relation to the cuts of meat create needed distance from he slaughterhouse in an era of factory farming. If we are as s a nation alienated from the food chain, and from butchery that occurs in meat processing plants across the midwest and souther states, the concealment of how we treat animals, and how we raise and slaughter them, seems closely tied to the return of diagrams that suggest a new intimacy with the animal, at least for the gourmet crowds of urban hipster butchers and their refined clientele, whose familiarity with the division of the carcass has gained a new almost topographic precision, as if they were doing the manly task of wielding the knives above an actual animal.

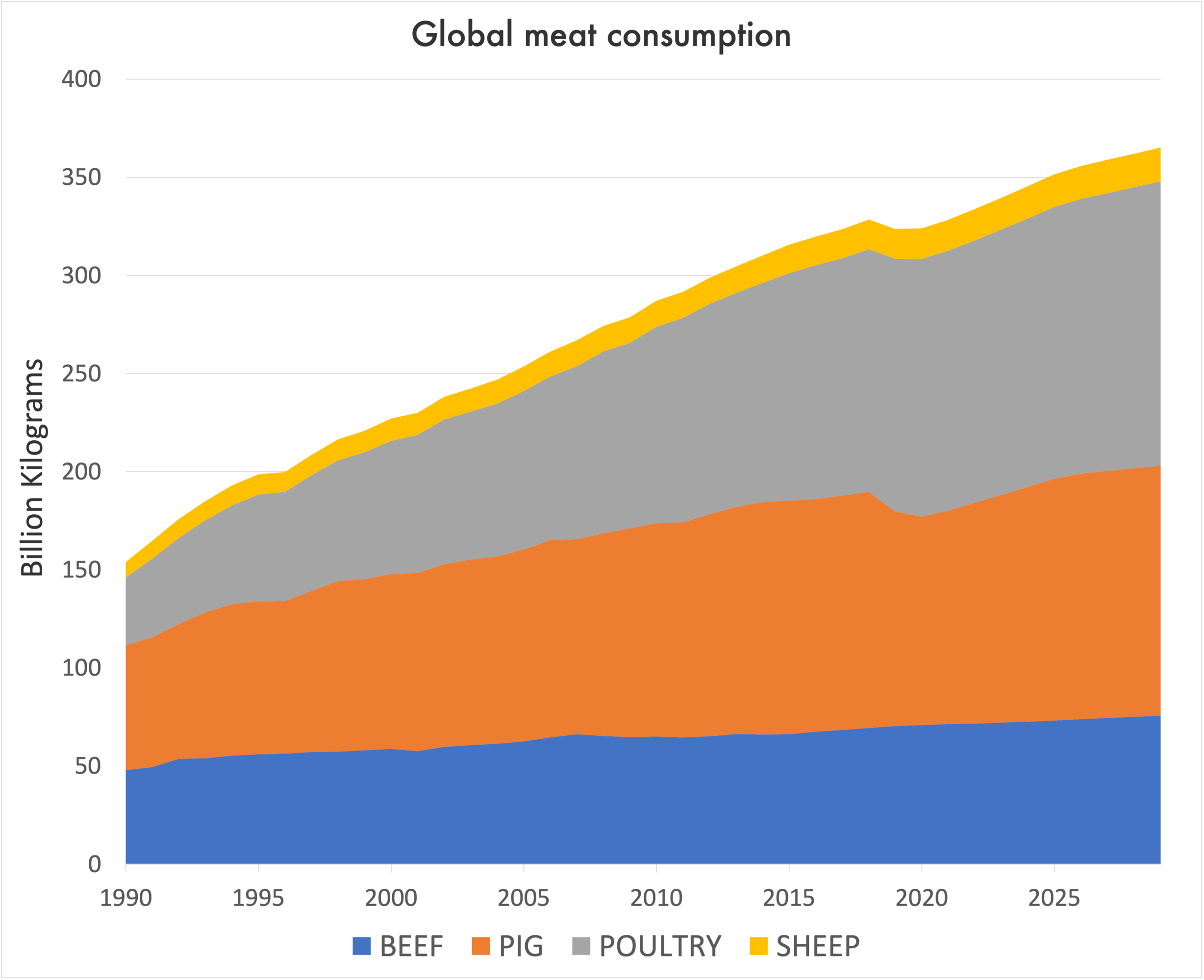

The changes of animal husbandry over the long twentieth century–or the long nineteenth!–have led to a curious distancing of the division of animals, even as we have increased consumption of meat, both in my own life-time–

Tonnes of Global Production of Meat based on Projected Population Growth and FAO Data/2012

and the short term–even if many argue we are approaching the ceiling of record-level consumption of animals meats, even as most in the world take for granted how their meat arrives fully prepared for consumption at the table, in their sandwich meat, or in their take-out cartons.

The increasingly insatiable taste for meat cuts has escalated beyond memory, although in quite unsustainable fashion, based on the fiction of the plenty of livestock for future generations.

The irrational expectations for the ability to meet global meat demand parallels the withdrawal of much familairity with the division of animals, or indeed the division of the famed animal. While long distributed to different social strata by earlier practices of cutting meat to reflect and feed the entire social body–from the elite consumers to the lower classes-

–all familiarity with the division of butchery has fallen by the wayside, save in the sophisticated circles that frequent the recondite demands of artisan butchery. The historical decline of tacit skills of apportionment and carving have been a consequence of the alienation of most menus from animal husbandry–symptomatic of an alienation of animals’ bodies from meat cuts.

When I see signs hanging in my neighborhood butcher shop window that invite new applications for workers with “no experience necessary,” I was tempted to apply to do more research for this post. But it was evidence at first hand of a decline of local knowledge, and a need for providing upper middle class with the best cuts possible. This was not a service economy, but a promise of training to cut animal meat in ways that the growing market for prepared foods had perhaps elided; the temptation that was very real. In fact, my wife reminded me that a neighbor had already recently started working there, and had been well-trained on premises; we surely wanted to keep the worthy business in business, and folks cycle through the non-unionized shop in a fashion that is notably brisk. The expertise in cutting meat, and offering customers meat cuts, had been, one presumed, readily reduced, as if the old art of dividing the carcass to transform dead animals to edible select cuts, still preserved in high-class British butchers, had been reduced, even as the rise of hipster butchery and whole animal cooking suggests it may be on the decisive rebound after a relatively recent if precipitous decline.

Meat arrives at butchers precut, of course, epitomized by the icons of dismembered meat that decorate the high-end precut gourmet pre-butchered meat that arrive in cardboard containers by truck. Such stylized icons resemble the puzzle pieces of a lost art of butchery, unlike the diagrams that once graced butcher’s stores. The packages of cuts arriving in trucks in the northwest and California are not inviting the consumer’s knowledge, but promise to contain butchered meat cuts that are neatly disentangled for culinary preparation.

The maps are no longer a sign of the skill of the butcher’s craft; the elegant cuts of meat cut “survival boxes” seem evidence of a huge surplus economy of meat, even if they promise quality of minimally processed cut of meat for consumption.

Can. one describe how the change in mapping meat both as a shift in knowledge accompanied the shift in styles of food? Akin to the shift in maps from paper registers encoding topography, locality, and landscape for an abstract denotation of place, there seems a decline of specialized knowledge or expertise, which has no doubt led to the rise of hipster butchers, evidenced by the recent closure of a butcher shop long operating in Oxfords’s Covered Market isn the UK, offering top-quality cuts of meat for high-brow customers, by a man who had been butchering since age fourteen. The loss of specialized knowledge seems hard to register, but the handiwork of the butcher Michael Feller is hard to encapsulate in a simple diagram–yet a diagram could be a calling card of the skills of separating cow’s, pig’s, and lamb flesh, as the sale of well-hung local beef, outdoor reared pork, and local lamb that was cut on-site without “cutting corners.”

Oxford, England is, of course, a small city that is surrounded by fields, where the cows roam in open pasture about outlying meadows within the ring road, where smells of manure waftinto the city at unpredictable intervals, creating a strong sense of a bond to animal husbandry where the richness of milk is due to the richness of pasture: it is where farmers can ford cattle across the River, Thames, and cows can ford the river’s expanse at the shallow waters of Oxford’s Port Meadow–

–and ford they do. If the cows that roam the Oxford meadows create a presence of cattle, the familiarity with cattle once prized in game shows and farms as living forms of abundance have been distanced from our imagination, as we have trouble mapping the path from farm to table, and as we have lost a tacit sense of our mapping of cuts of meat.

There seems far les knowledge in the mapping and carving of meat in mass culture or consumer society, but the absence of such images that mark the transition of carcass to meat. The sense of a withdrawal form the proximity to cut meat is already evident in the deep aestheticization of the bovine animal, but had deep roots in the new geography of butchery that was instituted at the new confines of Oxford’s famed Covered Market.

The Covered Market in Oxford opened its doors by 1657 to replace the “Ancient Custome and usage” of butchery stalls in the same area, and at the fining of public slaughtering, dressing up, or cutting up of cattle, calf, sheep, or swine–subject to a hefty fine, if “any Person or Persons shall kill, slaughter, singe, scale, dress, or cut up, any beast, Swine, Calf, Sheep, or other Cattle . . . in any open or public Street, Lane, or Way, within the said University and City . . . or cause to be hung up, any Beast, Swine, Calf, Sheep, or other Cattle, or any Part or Parts thereof, in any of the said Streets or publick Passages.” The bracketing of the arts of butchering to unseen sites was replaced by the hygienic map of the flayed beast, a diagram that would keep consumers of meat at a safe distance from the of meat, and imposing a hefty fine of confiscating any “Swine, Beast, or Cattle, shall be found wandering about the said Streets, Lanes, or Ways [that] it shall and may be lawful to and for any Officer or Officers of the said Commissioners, or any other Person or Persons whomsoever, to impound . . . in either of the common Pounds” of the city.

The transformation at this relatively early date of butchery before the late eighteenth century suggests a revolution in the bracketing of butchered meat that modernity has followed through on and pure, regulating the art of butchery that, while it filled a demand for fresh meat, and profitably pbrisk trade, was judged to “bee a great Annojance to all people that resort to the same” and “very prejudiciall to the health and habitations of the Inhabitants within the said Cittie and Universitie” by 1657 that “Butchers should keepe their Shoppes and Stalls in the High Street at other tymes then as aforesaid,” as the proposals for regulating the sale of butchers’ meat to areas outside the old “Butcher Row [Butcherow]” recently destroyed in a large fire, in hopes of “Regulateing and ordering of yet Butchers in the keepeing of their Shopps and Stalls within the said Cittie” and allow meat to be sold only outside of market days at the Butcher Row, lest “much disorder and disaagreement may happen among the Butchers who ought to keepe their Shoppes in the said Butcherow as aforesaid, And . . . prove a great wrong, prejudice, and oppression to diverse of them who keepe their shopps there, if any particular person or persons should set up any stall or keepe any Shoppe in any other parte of the Cyttie.”

The transformation of meat for the table seems elided in the vanishing of an older style of mapping meat, but one can perhaps detect the revival of artisanal butchery is eager to reclaim, in defining their profession. And it is hard not be struck by the loss of such long-cherished images that mark the transition of carcass to meat, a transformation that in the laws of Kashrut is acknowledged as a transitional moment of theological consequences, to be approached with intention, is seen with blinders akin to those which render horses purblind as they carry passengers. Increasingly, no doubt, we grow far less readily prepared to acknowledge the transformation of meat to meals, or the trajectory of processed meat to our overly hungry mouths. Have we forgotten, in the absence of an appreciation of carving the animal carcass, a consciousness of the mapping of farmed livestock as an animal intentionally prepared for future consumption?

So much hit hope in the recent hybrid images that map prepared meat cuts on the bodies of cattle as the vessels of imagers of prepared meat, as if no active agency of butchery or cutting were required to accompany the skills that are used to transform the raw to the cooked. In these images, the ox looks at our face mutely, as if offering himself for dismemberment, without need of a map.

The late nineteenth-century origins of the farm in question that has taken time to illustrate the cuts it ships in cardboard boxes seem intent on recuperating a relation to the provision of meats in the past, as much as the artisanal legacy of butchery: this is a promise of farm to table, quite literally mapped. Or, at least, it is a promise to be doing the mapping for its customers as a mode of assurance. The historical status of these distinct cuts of meat delivered to urban audiences of west coast cities had a long history of converting the cow into cuts, and remapping meat for consumption and distribution, if not civilizing the very process of eating meat as a form of sociability, often forgotten in the supermarket display cases of shrink-wrapped meat that arrives from factory farms. If the animals pastured are echoed in the astroturf-like green plastic trim some butchers still display, have we forgotten the hidden history of how we came to map meat?

Far from only defining the meat–or the cow–the butchery map defines our place as viewers and as eaters. It does so through the sorts of literacy that it presupposes, embodying the rationality of the butcher shop and the education of the prospective customer, elevating the sectioning of meat from a market or from mess. We are asked to see the cow as it is best divided, not only by the best butcher, but in ways that cast the skill of the butcher as akin to that of the master-cartographer, and invites us to see the preparation of meat as process that is as solidly rooted in learned skill that transforms the cow that stands upright before us on the earthy meadow to a meal that is able to be consumed among the “animals that we eat.”

For we all–at least all who seem to be ready for organizing a barbecue, or just grilling meats, seem to know, so that we yuppies are all but ready to attribute to the truly carnivorous instincts of our pets, replicating the first-hand familiarity with the cut-up carcass of a cow on its way to become beef even to the stuffies we buy for our pets. The division of the cow, sheep, and pig from beef, lamb, and pork is a master mapping of domains of food, rooted in the skillful raising of the animal and culminating in the division of the animal corpse., as if this will sanitize it before it reaches our dining tables. And the sanitizer in chief, who drains the animals of blood and represents them to us as consumers was performed by a top-hatted man in a white spotless apron as his blade separated bone-in beefsteaks and rib-eye cuts that hung behind him for customers.

There is, it is true, an iconic appeal of some animals, whose icons provide arresting signs of their conversion to food on city streets and whose unbuttered outlines are tokens of the foods from which they are processed. But these are the exceptions, which succeed as they suffice to offer signs of the distance of many cuts of meat from the animals from which they were cleaved–and of which they once formed a part. And perhaps the pig is always so standard an early modern sign for butchery–and a familiar animal to be slaughtered for sausage or cold cuts–to be far from the true art of butchery we seem to be staring into in the touristic time-warp tourists still encounter on Parisian streets.

However, the division of the cow seems to have set boundaries in our relations to meat, inn part because of ugh skill of its division for parts, and the greater difficulty in mapping out the sections of the slaughtered beast to convert them to our cooking skills–and to the levels of taste, and economy of meat cuts, that good butchery skills imply. If the low status of some slaughterhouses and cuts of meats is implied in the seedier areas of butchery in many urban zones–the Tenderloin, for example, that wedge of distinctively flat urban land in San Francisco that is historically bounded on the north by Geary Street, on the east by Mason Street, on the south by Market Street in San Francisco, seen not as a meat-selling region but the “soft underbelly” of the city’s urban vice, much as the Tenderloin in New York City, and may suggest the higher wages of policemen in that part of the city–which allowed them to eat better cuts of meat–or the central site of urban graft–it suggests the transposition of meat cuts to class, and the social strata in urban life, analogous to the region of “outcast London” that emerged in the middle to late nineteenth century, so evocatively studded by Gareth Steadman Jones.

The conversion of cuts of meat to social tiers of urban society seems to reflect the social acknowledgement of the art of butchery as setting a new frontier in the domestication of the animal for human consumers. The mapping of meat is a transformation of the animal to social level of the consumer, mapping a way to convert the mammal into cultural categories of human activity, in what may be the ultimate sort of structuralist dream of post-primitive categories, both in farming and the healthy preparation of meat in an age of increasing fears of food-born bacterial contamination of meat cuts that can give rise to the bacterial infection of the gut from either the farm or abbatoir, and view the elegant sectioning of a lamb’s body as a of a piece with its breeding and raising, and a statement of the skillfulness of its preparation for the table, or at least for multiple modes of cooking–roasted or grilled–as the flesh is converted into food that is promised to be easily digested.

The image denies the differences between raw and cooked, and the living and dead, by providing a far more easy way to visualize cuts of meat as if inscribed on the surface of the living body, and indeed “mapping” regions of a territory by set precincts, creating a consensus erases any sense of the subjectivity of the animal, and displays the carcass as it exists for the carnivore, the regions of the living cow separated suddenly from any sense of the messiness of butchery. In ways that echo the current rise of the artisanal nature of butchery that have so widely recuperated similar images of the unflawed carcass of the cows, pigs, or other quadrupeds, the cow is displaced by the craft: for as it appears calm on its grassy meadow, the cow exists to be butchered, and seems not only quiescent but acceptant, prepared to sense no pain at the prospect of being not only divided but seen as it becomes transformed to a set of meat cuts.

As viewers of this fundamentally pleasant image, which invites us to accept the world from the perspective of the sophisticated carnivore, we accept the sectorization of an image of an animal as the surrogate for the actual division of its parts. The fine dotted red lines of that vectorize each region according to its musculature run against the rippling of the individual cow’s skin, and seems a striking way to translate the living animal by an artisanal tradition of apportioning an organism into cuts of meat. While the marginal image of the butchered cadaver of a cow reminds viewers of the eventual division of the animal body for its human consumers, and a microscopic view of coliform bacteria reveal the dangers if the sanitary procedures of such a translation are not carefully followed. The resurgent interest in butchery diagrams reveals not only a renaissance of artisanal butchery, and boutique butchers run by hipsters who cleave and sell meats sourced from local farms, of hormone-free and antibiotic-feed free stock, but use a map to communicate and establish shared consensus on the proportions of bone to fat, and flesh to fat, in distinct cuts of meat that we aim to prepare. While such distinctions elevate their cost, they also draw clear criteria of taste, communicated in diagrams that recall medical textbooks if not just book learning, creating a needed consensus and useful shorthand around tacit levels of knowledge of their relative qualities for butcher, customer, and chef.

The portioning of what appears a living body, but reveals a sort of doubling that the alchemy of maps is particularly suited to perform. For the farm animal that seems to have paused while grazing is transformed for the eye of other images of the same treatise are moe anatomical–re learned viewer into a carcass: the guidelines for portioning the meat of the animal, before its slaughtering, is something of a championing of the dexterity of such division as an art that is akin to the technical skill of drawing maps–even if the art of butchery is, in general, judged far removed from the art or technical skills of drafting accurate maps, the orientation to the culinary arts served as a translation of the living animal to an edible form. The origins of such a tradition of apportioning meat and carving the meat after it is cooked but before it is placed on the table goes back to the Renaissance, but a complex condensation of the civilizing process seems to be projected onto the process of dividing the cow’s meat in preparation for the table, in ways we’re starting to recover. Unlike images from the treatise more anatomical in their copious level of descriptive detail to the sectioning of pork parts–

It is almost as if the doubling of the animal is removed from the objectivity of a medicalized image, but is rather a field that moves from three dimensions of a living animal’s body to a flat surface.

But the skill of dividing farmed animals and of recognizing individual cuts of meats suggest a transformative remapping of meat: the subjects of good animal husbandry are rendered into regular configurations of cuts after they are slaughtered, in a metamorphosis of meat that is almost as important as the distinction between raw and cooked. Indeed, the instruction in accurate cuts of beef was invested with a geometric regularity for Hylas de Puytorac, who would win a certificate of agricultural merit to the state which Jules Ferry had created, used to teach readers of the nature of the parts of animal we eat.

The award of merit de Puytorac won reflected his presentation of butchery as an moral message to instruct readers to eat in the most healthy manner. The diagrams of Hilaire de Puytorac create not only a condensation of the civilizing process, but a confluence of a Cartesian sensibility and bourgeois lifestyle and attitudes toward food–they not only translate between the living and the dead, in an evidence of the uncanny, but effectively bring the cuts of meat from the butcher’s stall to the houses in which meat cuts are served.

De Puytorac artfully imagined the transformation of cow to carcass was a question of domestic economy circa 1920, and prepared the animal by distilling the principals of meat division as if they were naturalized in dotted lines atop the skins of living animals; long before they became suitable art hangings, charming for the endearing way that they represent the meat cuts that entered kitchens or butcher shops, their pedagogic clarity directly translated the bodies of living animals to meat, dividing the living animal to the names of meat cuts without needing to convert it to a carcass.

Hylas de Puytorac’s elegant line is far removed from the gross familiarity with which bovine animals seem to gaze right into the eyes of customers at some urban burger joints, now presented as if emblems of the high quality of meats that they use by virtue, perhaps, of their heft, without any sense of carefully portioning meat cuts as de Puytorac so prized. This is achieved by the life-size dolls now included outside some craft butchers, almost eager now to shock the passerby by their familiarity with meat, labeling one’s arrival at a truly honest butcher shop: the old-time bags from local butchers in New York or Ottawa suggest an intimacy with the bovine carcass they promise to transform for your table, in a modern iteration of de Puytorac’s advertisements, now so popular as posters and printed postcards.

To be sure, there is something unseemly in the lack of drawing a boundary between the cow or farm animal whose carcass is offered to provide markets with meat and food preparation. For de Puytorac, the naturalization of meat cuts followed crystal clear logic, echoed in those crispy defined dotted lines which almost elided the technical skill of slaughtering and butchering by which the sheep was made lamb, and the cow made beef: the subject of each “map” was the translation of animal to meat, and clearly subtitled “the animals that we eat,” but the cuts of butchery were replaced by a sanitized map for public consideration by the educated or informed, as if this domesticated and civilized the very process of describing, cutting, and consuming cuts of meat.

Acts of butchery was the elegant mapping of edible meat were omitted because the map instructed viewers in a new relation to the body of the farm animal, even if they lived far from the farm and probably weren’t yet familiar with the butcher stall or the laboratory of the kitchen.

But the rise of meat portioning, recently returned to artisanal butcher shops as well as marketplaces and abattoirs, has lead to an increased interest in re-mapping the cuts of meat with an aesthetic elegance that the mass-market of food production had long forgotten. With the return of the mapped body of meat at local butcher shops gain an aggressive economic presence in select metropolitan areas where the revisionist of the art of butchery gains a new appeal of reintroducing the varieties of beef, lamb, or pork made edible by the linguistic transformation of the living animal to a carcass, and the mapping of a beings’ edible elements, one detects not only an aesthetics of the ‘whole animal’ movement–

Sanagans Meat Locker, Toronto CA/Letters in Ink

–but the embrace of butchery, cookery and meat-consumption as a valued aesthetic has led to the revival of such once antiquated maps of meat in European visual culture. The recent linguistic fetishization of rediscovered arts of butchery emphasize the value of its learned, transmitted intellectual status of the names of meat cuts that frame the image of animal that looks straight into the customer’s eye at Sanagan’s Meat Locker in Toronto’s Kensington Market, acting as a hand-drawn hipster rebus for first-hand familiarity with meat cuts of Victorian elegance for customers who are looking for specific cuts and are in the know–beyond the nostalgia of traditional arts of butchery outside modern meat markets, where they are portioned for the in the know by hipsters who are often tattooed and wearing newsboy caps.

The cultural transmission of adept skills of meat-carving is found, in other words, not only at the butcher-shop, but on the drafting table: as much as the whole-animal ethos has increased consciousness of artisanal skills of portioning freshly butchered meat among a new generation of hipster butchers, the division of the animal body was defined in increasingly elegant diagrams of butchery echo the skills of discrimination encouraged at the dining tables of courts as well as the domestic dining tables of mid-nineteenth century. New modes of mapping meat were drawn on the forms of living animals, and widely diffused in detailed diagrams that increased admiration in engravings that delineated meat cuts with the objectivity of an anatomical diagram–but that maintained the illusion that steers were divided for the table directly from nature, or from the farm, so that “Le Boeuf” is standing, hopes planted firmly on the ground, gazing duly ahead as the cuts into which his body will be divided are inscribed according to discrete cuts to be distinguished by their ratios of taste, toughness, fat and flesh.

The graphic sectorization of the animal “body” transformed the slaughtered carcass not only to butchered meat, but to a gastronomic culture of increasing and considerable sophistication. The portioning of meat and the cutting of the cooked body maps onto a signifier of socioeconomic class, marking the transformation of the animal body into a recognizable and elegantly edible product. One might continue the metaphor or dine out with it as more than a convenient or apt figure of speech. Much as mapping is a practice of imposing clear configuration on space to codify spatial relations in a recognized form, the mapping of the cooked and the slaughtered carcass transformed the natural boundaries of the well-husbanded steer or other animal into shapes that we invest with meaning and naturalize by their own geometry, and were easily renamed in works of popular education that might be traced back to the efforts of Charles Dressiens’ hopes to ameliorate the lives of Frenchmen by “addressing their stomaches” by codifying “une science de ménage” as precepts of “education ménagère.”

The domestic economy of middle class homes placed a strong emphasis on elegant cutting of cooked meats. “One of the most important acquisitions in the routine of daily life is the ability to carve well,” advised the 1852 Illustrated London Cookery Book somewhat sanctimoniously; even if “the modes now adopted of sending meats, etc. to table are fast banishing the necessity for promiscuous carving from the elegantly served boards of the wealthy,” it continued, “in circles of middle life . . . the utility of a skill in the use of a carving knife is sufficiently obvious.” The accomplished decorum of severing joints, carving birds, and the dexterity of manipulating knife and fork garnered spousal approval and admiration, evidencing an ability to divide meat that designated class differences.

“Carving presents no difficulties; it requires simply knowledge,” Frederick Bishop continued to tell readers. Lack of expertise is simply a question for Bishop of good decorum and tasteful bodily comportment. “All displays of exertion or violence are in very bad taste; for, if not proved an evidence of the want of ability on the part of the carver, they present a very strong testimony of the toughness of a joint or the more than full age of a bird: in both cases they should be avoided. A good knife of moderate size, sufficient length of handle, and very sharp, is requisite; for a lady it should be light, and smaller than that used by gentlemen. Fowls are very easily carved, and joints, such as loins, breasts, fore-quarters, etc, the butcher-should have strict injunctions to separate the joints well.”

The transformation or passage of animal carcass to meat suitable for preparation, and the linguistic conversion of indicating meat cuts distinct from an animal is an ethical question of renaming, but also a deeply cultural process rather than only mapping animal parts. If all mapping is something of a conversion of nature into culture–and a creation of place as a known identity, able to exist as a set of coordinates, as well as recognized in one’s mind–the mapping of meat is more than a transformation of raw to cooked, but once-complex process of rendering meat subject to and fit for human consumption, in a combination of the arts of gastronomy and butchery far more than simply anatomy–if the language of mapping meat hides both the work and presence of the butcher and slaughterer as well as the cook by which the tender morsels are prepared, as clear linear divisions were imposed on the steer that was transformed into beef, ready to arrive into the stewing pots illustrated above the animal, or cut into pieces ready for consumption.

Far from only employing a sophisticated language, the mapping of meat is something like a deeply historical and cultural sedimentation of rites of renaming what was once alive in ways that entered local food cultures and prescribed models for the preparation of food that seem eerily akin to recipes.

But the decorum for separating cuts of meat or meat apportionment has a long if submerged history, and reveals a cultural form of mapping, and the artifice of mapping accurately. I begin with such a polite and decorous image since I’m moving toward some diagrams of sectioning prime cuts that focus on the separation of cattle into meat cuts–maps that similarly separate the division of animals’ bodies by butchers and convert what was a body into portions of edible meat. Although Nicola poetically described on “Edible Geography” “the sculptural discovery of secret shapes within the familiar architecture of an animal,” mapping the carcass is not only a process of unpacking, or of revealing, but a transcription as well as a form of translation of the body of the animal to the provision of cuts of meat–a renaming of body parts as forms of meat. The transcription converts embodied form to table, dismembering the body by preparing of the cow’s carcass into pieces of prime cuts for the eyes of the chef. The process of extracting individual cuts of meat from the body, and renaming them, is the ultimate denaturalization, or repackaging of meat cuts for the market place–as its unwanted head, horns, ears, and hooves are discarded and not destined for consumption. And although the map suggests proximity to the steer, few folks who read the image would have first-hand relations to the carcass, but rather a naming of regular configurations once seen in the butcher shop.

To be sure, the marginalization of butchery from a public act to a hidden practice, located more often in slaughterhouses or behind the scenes, may lead us to marginalize the slaughtering of animals from our current mental maps, as if the “Tenderloin” could refer only to a seedy neighborhood, as well as the cheaper notion of realty that might be named after the cheaper cut of beef in New York, maybe combining the inexpensive living in the neighborhood spanning from 23rd to 57th streets and Seventh and Eighth, but also displayed clear formal similarities to a strip–

–but also have gained new metaphorical legs during the intensive carving up of urban neighborhoods, and indeed molding urban space by sheer force by master planners who sought to carve up the city, as urban activists who treasured neighborhoods bemoaned development as “cleaving” organic districts of life by a brutal force of will, carving up an urban space by its neighborhoods in ways that display striking formal characteristics to the inviting “meatspace” of New York:

Such a cleaving of neighborhoods by what seem–on the city map–small and delicate cuts reflect not only the musculature and distribution of body fat on the animal, but the conversion of lived space to a space of good manners, social etiquette, and culture.

How did this division come to be codified? As much as how we bring the meat to our table, it is a sort of map of how we ingest our meat, and deserves to be examined as such. Rendering cows as canvasses to make maps, and imagining the coat of a European Holstein cow as bearing a “natural” image of the world may universalize the breed, but is a pleasant fantasy, neatly naturalizing a global projection by a clever photoshop.

The photoshopped cow was clearly painted by stencil, but we’ve long mapped the cattle varieties specific to regions–as the Holsteins of France, who seem naturalized by region akin to a map of cheeses or wines, locating different breeds of cattle as if indigenous to different provinces and landscapes of France. But rather than derive from specific regions or terroirs that distinguish the different qualities of wine–perhaps embodied by their local mineralogy, acidity, flavor, and earthiness–the mapping of meat is a more profound conversion of the natural to a cultural product, and indeed an illustration of the mastery over nature of the sort that finds expression in a map.

To be sure, there is considerable defense of the healthful or patriotic properties of “meat” that various nations produce.

Tesco Advertisement

But mapping meat into prime cuts acts more like a practical sort of map of cuts, both by distancing bovine forms by labeling, converting limbs beneath its skin to an ownable set of parts and taking possession by some alchemy of them as cuts, renaming the animal as the edible. The relabelling of the animal indeed turns it into the consumed: and the artistry of the artisan translates the animal into anonymous cuts of meat that can be recognized as discrete. In this butcher diagram–or butchery map–the cow becomes the territory, removed from ts location and subject to division into brightly colored prime cuts with far less specific local knowledge of the neck, cheek, and tongue:

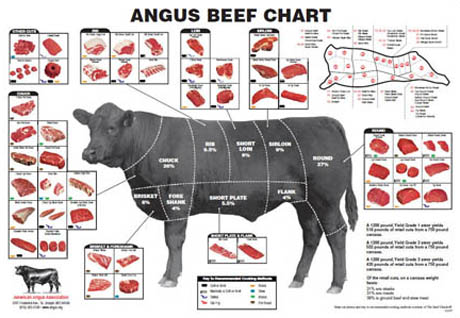

This process of translation, and of unpacking distinct cuts, is familiar already in the below enumeration of prime cuts, respecting a basic division of chuck, rib, loin round, and brisket, plate, flank and shank, and hinting at the deeper cultural division of mapping styles, even if the act of butchering has been separated from the meat shop:

The point is restated in Sanagans, as well as in the Harlem Shambles, by openly distancing butchery from the slaughterhouse:

Is this division not a distancing from the slaughter house? If Freud had discussed the ultimate taboo of the dead body of a person as a cultural universal, the naming of these parts of the slaughtered cow that arrived straight from the Shambles or slaughtering house allowed their parts to be converted to the marketplace, assimilated to recipes, and be on their way to cooked. This is not a mapping of nature, but a cultural relabeling of body parts, a continuation of the logic of the slaughterhouse itself, that peaks into everyday life. For the naming of meat cuts serves as a way of processing the formerly live cow into discrete areas that arrive in the kitchen or chef’s table, or a distinct language by which to name regions in relation to distinct styles of meal preparation and indeed a form that they might be most consumed. The idea is less to better know the topography of the steer’s divisions, by converting a division of the progression of the steer’s body in the slaughterhouse and to a new lexicon as it moves toward the preparation of food. The division of the steer in multiple sectors is not merely about labelling, but a process of mental transforming, about naturalizing the division by which the body of the steer becomes transformed to meat.

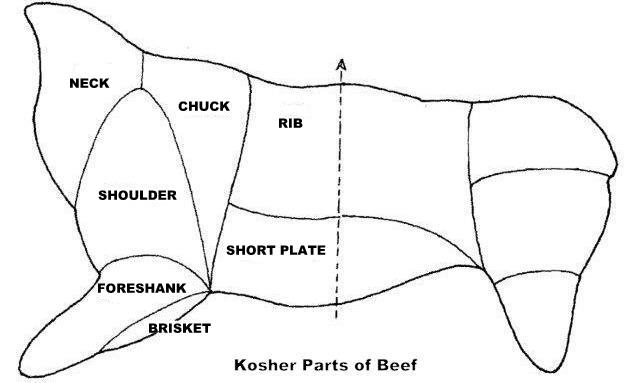

Yet the work of translation in such diagrams follows a distinct set of practices–or so goes the hypothesis of this post–as the steer’s body and musculature meets distinct markets for meat cuts, in ways mediated by technologies of dividing as well as the art of butchery. At one extreme, the very different division of cattle carcass best known is perhaps that mandated by Kosher laws of food preparation through expert division by which animal slaughterers prepare the meat suggest not only follow bodily sectors–despite the limitation of edible meat to the front quarters. As much as a distinct form of meat-preparation, the sanctioned division of the steer seems to reflect a degree politesse in its avoidance of the rear quarters of the animal, as well as meat use–refusing to acknowledge the flank, rump, or sirloin cut, and sanctioning only the central cavity up to the thirteenth rib, or often stopping at the twelfth. (In Israel, the rear leg is considered kasher, and trained slaughterers take the time to remove the sciatic nerve, leading butchers to sell meat from the leg as kosher meat and maximize the amount of meat available–even as they disdain and discard the “non-kosher” nether-quarters of the animal and its head:

The division of the animal results in the celebration of the slow-roasted or braised brisket for the ritual meal. The quite exact mapping of the sanctioned cuts of meat from the twelfth rib are quite distinct from the cuts of meat that are sold by kosher butchers, from Square Roast to French Roast to Ribs and the Deckle, or the fore shank, but all are separate from the cuts sold off for non-kosher consumption–

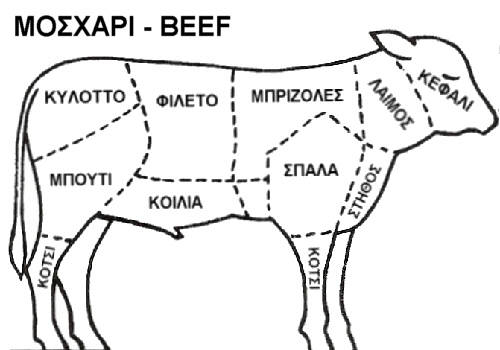

The sectioning an animal does not simply follow the form of the body, however, or the musculature of the steers: different cultural styles of butchery may be geographically distinguished within the variety of ways meat is mapped in established diagrams, a rich subject for research, that reveal cultural division in the preparation of the animal–and sectioning does not only reflect sanctioning.

In Israel, the division of cattle can indeed be utterly more complex, where trained shochets divide the steer’s body not only into brisket, shank, ribs and rump and the like, but also to possess detailed mastery of Talmudic requirements for slaughtering animals. The requirements for ritual slaughtering —shechita–demanded a detailed knowledge of animal anatomy to cut precisely the trachea, esophagus, jugular vein and carotid arteries, that were not confined to the exterior or superficial anatomy: butchers were required to distinguish the dangers of any disease able to be transmitted from animal to man, by inspecting the viscera, lungs, and organs for any malformations, as well as to possess adequately sharpened knives to ensure the absence of all pain for the animal, lest they be made as unfit for consumption as if they were diseased, given that man was only permitted to kill beasts for the sole reason of nourishment. The piety of the shochet was perhaps a mean to access the prized delicate tenderloin, reflecting but preserved a parallel sort of an old-school style of butchery, imported in the diaspora from Europe:

The resulting intimacy with the cuts of meat are something we seem to long in an era of processed meat from factory farms, from which we want to distance our own consumption, surviving in the ethical laws of kashrut and the traditional use of cleavers to slit the through of beasts by one movement alone, often on an animal recumbent, rather than suspended from a hook or having been killed in painful ways.

But butchery provided an orientation to consumption that has only increased in the current marketplace for food from factory farms. Scots butcher-cuts are similarly refined and complex, as if suggesting a professional transmission among artisans or animal slaughterers, emphasizing the neck and cloud, and different cuts around the round, leaving oddly absent and unnamed the often esteemed tenderloin:

There is no doubt similarly complex division of the cow in Mexico suggests a distinctly artisanal culture of meat division, oddly similar to that in Israel in its emphasis on individual specialized cuts, each destined for different preparation, in a considerably complex practice of apportionment and distinction of the specific value of meat cuts:

In Greek meat markets, the culture of a distinct uses for meat cuts animates butchery around an even more comprehensive ‘whole-animal’ culture of meat consumption:

Farmer’s markets wholesale meat sellers have given rise to a new sense of wholesomeness of whole animal consumption, including the pig’s feet and jowl, as well as the “picnic.”

But pride of place in the complexity of artisanal meatcuts must go to the Austrian butchers, whose care of carving carcasses is perhaps a legacy of the Hapsburg court: dividing the steer’s carcass into some 65 distinct cuts from the Rostbraten to the Tafelspitz and Waldschinkin suggests the survival of local ingenuity and refined taste. Rather than informed by a unique whole-animal ethos, the sophisticated division seems oriented to the distinct preparation different parts of the steer are due in the old empire, and perhaps the difficulty any but the best butcher will have in locating the desired filet:

The partitioning of the entire denatured and bisected carcass of the steer that arrives from the slaughtering house is converted to distinct portions, often destined for different dishes, betraying a distinct level of refinement in both traditional techniques of meat preparation and the codification of a high local level of butchery skills:

Of course, the greater simplicity of bisecting the cow’s body and dividing it into quarters is, in many ways, an American invention of which we can be proud: it is a reflection of the rise of industrial butchery, which process multiple carcasses based on sawing the linear saw-lines to create a division and cross-sections–and a consequent decline in the taste for specialized cuts of meat. The shop for buying meat has long migrated from the site of slaughtering–although there’s a been a return in some communities for fresh meats.

The predominant most current divisions of meat preparation have tended towards overtly linear cuts and schematization, mapping cuts readily performed by sawing bovine bodies fresh from the slaughterhouses to showcase “chuck” and “round” as generic qualities of ground meat–as much as cuts–and perhaps made more distinct by gradations of marbling than specific bodily origin:

Or, in an alarmingly denatured schematic image of a side of contemporary “retail beef,” removed from a steer and ready for shrink-wrapped packaging at your local COSTCO– the schematic rendering of the steer seems cut by a cleaver, rather than with attention to recipes, as if the cuts would break apart as so many quadrants of a chocolate bar:

The meat-packing industry has developed its own form of mapping, easily transferred from veal to beef in ways that render the butchered animal ready to eat:

A near identical imagery survives in Costco and in many food service outlets. But the range of meat cuts that one associates with the artisanal has however made quite a comeback in certain niche markets recently, where the elegance of butchery as a form of sectioning has returned, less often perhaps for immediate consumption of prepared meats than the careful preparation of meats in restaurants:

But the disembodied icon of denatured cuts is far less disturbing than the brightly packaged glistening cuts stacked in freezer bins in supermarket meat sections, value packs of USDA Choice that serve as opulent illustrations of plenty for consumers unlikely to ever undertake butchering skills.

–or those recognizable cuts, stacked in rows beside fake plastic grass in butcher windows, fake grass whose presence itself suggests the meat’s remove from the scenes of butchery but oddly conjure the fields where the slaughtered cows presumably once pastured.

There seems to be far less of a lexicon for differentiating meat cuts, as they are increasingly denatured from the animal or steer, and familiar only as varieties of steaks:

Removed from the active division of the steer’s body, such meat cuts appear as if shorn of the animal, in the plastic packaging in which one might meet them in the refrigeration section of a supermarket, or beneath butcher glass.

Yet to remember the distinct interest in distinguishing distinct diverse cuts of meat, take the time to compare the elegant distinctions for dividing beef clarified in a later nineteenth-century image of the range of cuts by which those technically adept can elegantly carve a cow’s carcass, around its neck and shoulders, corresponding to a bull’s musculature, so as to refine desirable neck and chuck meat, that convey the aura of a mustachioed blade-sharpening daintily aproned overweight butcher sipping wine, if not the wisdom they would pass on to good raisers of livestock in the later nineteenth century by that wonderfully didactic gastronomic educator, de Puytorac:

Dividing the animal is the clear precursor to eating one. For Hylas de Puytorac, Chevalier du Mérite agricole, images as”Le Boeuf” were destined more for schoolkids than for butchers; primarily didactic in nature, they sought to preserve an agricultural knowledge in danger of disappearance.

The multiple images he carefully engraved of pigs, cows, and other animals reflect the basic prime cuts suggest a tripartite sectioning of each half of the cow, but are elided with a naturalistic rendering of the bull whose musculature he would have recognized–an appreciation whose embodied animality were not so distant from the art of butchery. Cuts are clearly subdivided by muscle-groups, in ways that recall the deeply artisanal skill set of butchery. The division of the body of cattle is far more refined in this 1852 engraving of the over forty available cuts on the bullock:

A 1928 division of the cow for butchering is similarly detailed; although its portioning is far less refined, it similarly covers the whole animal, dividing the brisket in multiple cuts as well as the shank in ways that suggest a process of repackaging bordering on schematization of an almost Tayloristic fashion:

Much modern meat-portioning may lack so much of a map, even in its more refined images, as they privilege “fine: cuts, sadly, as the division of animals is performed by saws and only rarely is the butchery of the entire animal actually on view:

The generic division into sectors seems far more readily sawed for repackaging, which, disturbingly, somehow acquire their greatest color and tactile proximity only after being segmented:

This occurs in ways that, unhealthily to me, threaten to elide for perpetuity the distinction between cow and beef for customers, and ignoring as inedible a good amount of bones (and meat) that seem too reminiscent of their bovine origins, a transformation that seems elegantly if somehow quite inappropriately elided in this condensation of the remapping of the live cow to a carcass in this oddly ghostly image of meat cuts from the Encyclopedia Britannica, that seems haunted by the older arts of butchery but shows the sites of cuts of meat in a flayed carcasses biomedically, and encased in fat:

It is almost tempting to read it as a cautionary image about our increasing consumption of animal fats.

Another piece de resistance! Query: can you do a musing on what can’t be mapped? In a sense the answer is already built into you posts: maps provide illusions of objectivity, control, and fixity where they don’t or may not exist. What would antimapping or non-mapping correctives, strategies, or alternatives be?

That great question is perhaps to what I should dedicate the rest of my days to: what goes against the grain of maps, and what is so troubling that it just can’t be given the sense of objectivity that mapping wants to promise, might even be what–paradoxically–generates a map! I’ve (broadly) imagined a piece on drones and mapping, and how the drone responds to the universality of mapping in an age of globalism, and paradoxically provides an illusion of power in an era where traditional maps seem to have lost their primacy as tools of war, and global maps provide the sort of comprehensive images to which only drones can respond.

Pingback: How Butchery Maps Turn Cows into Territory – Tho Loves Food