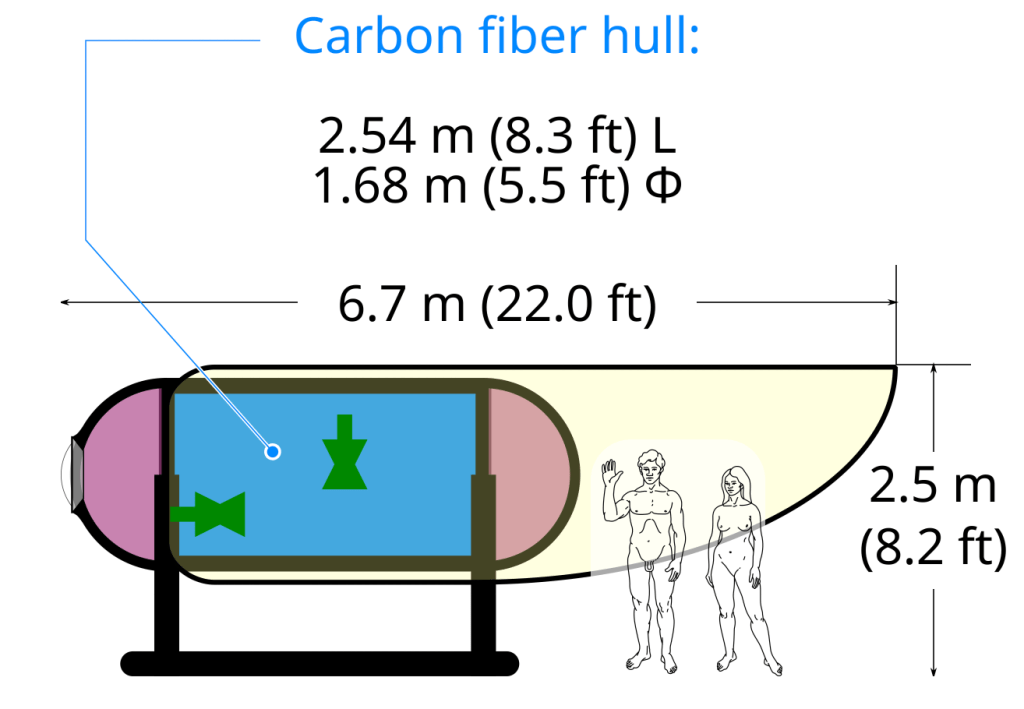

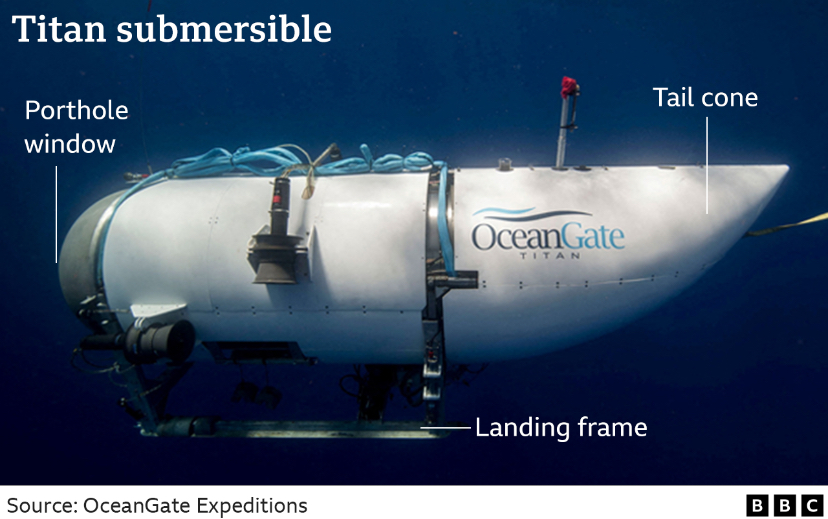

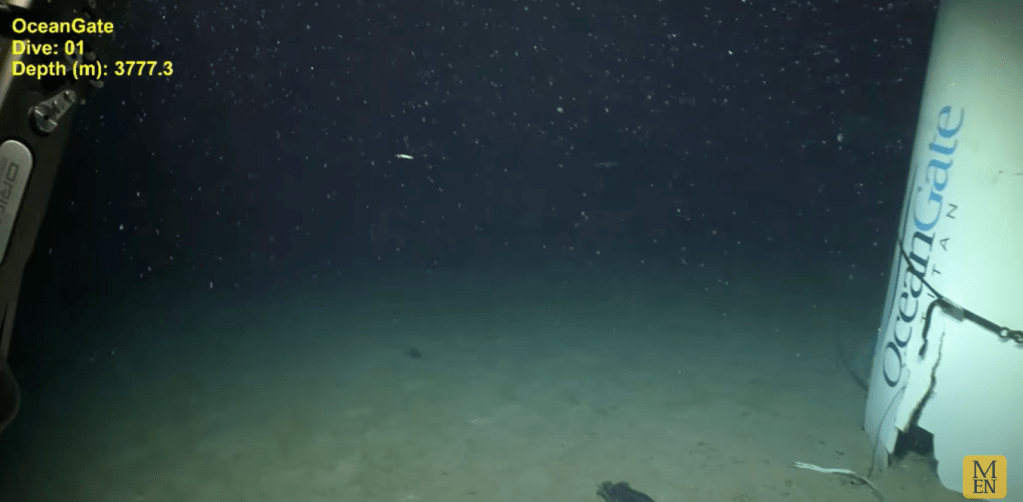

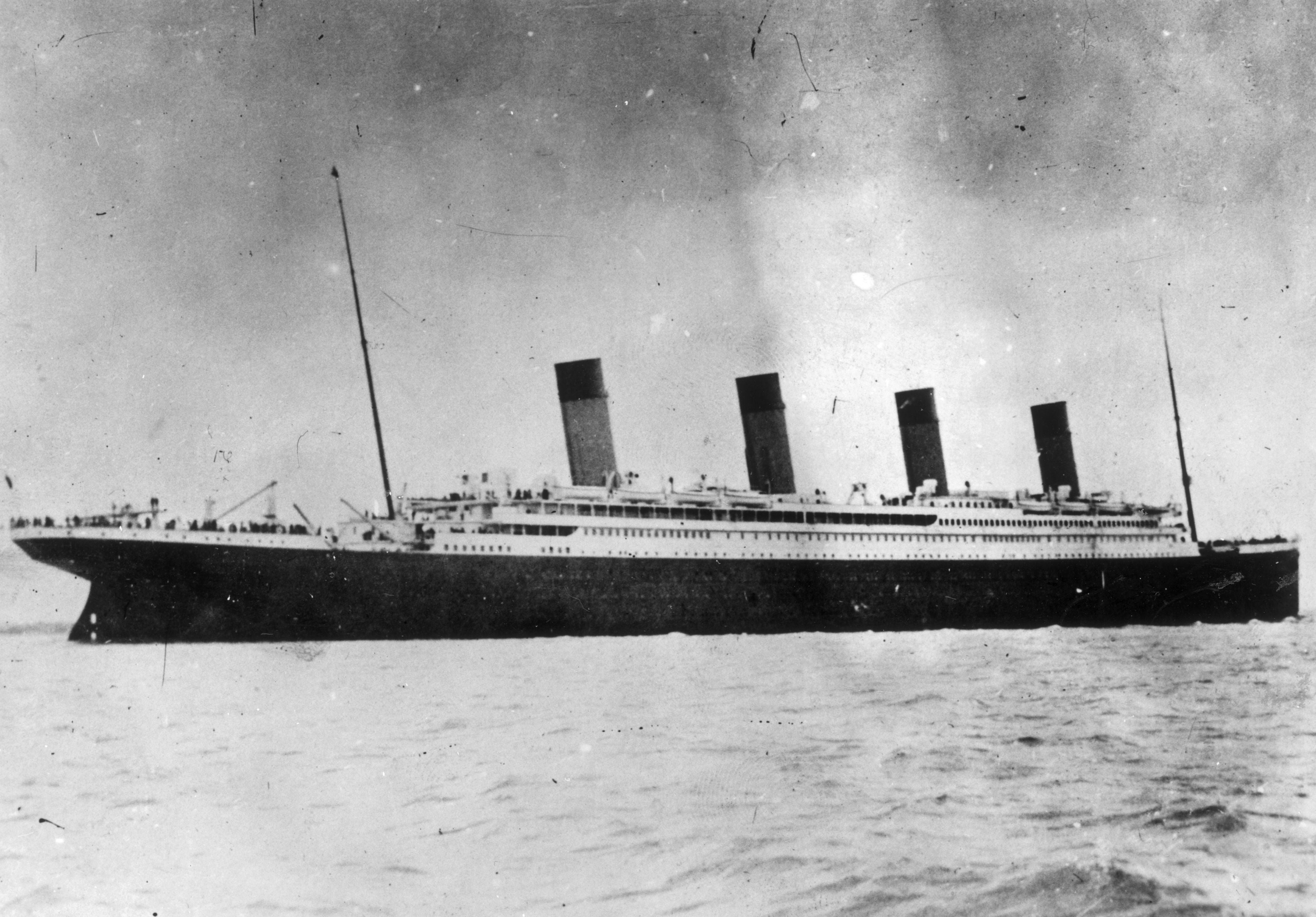

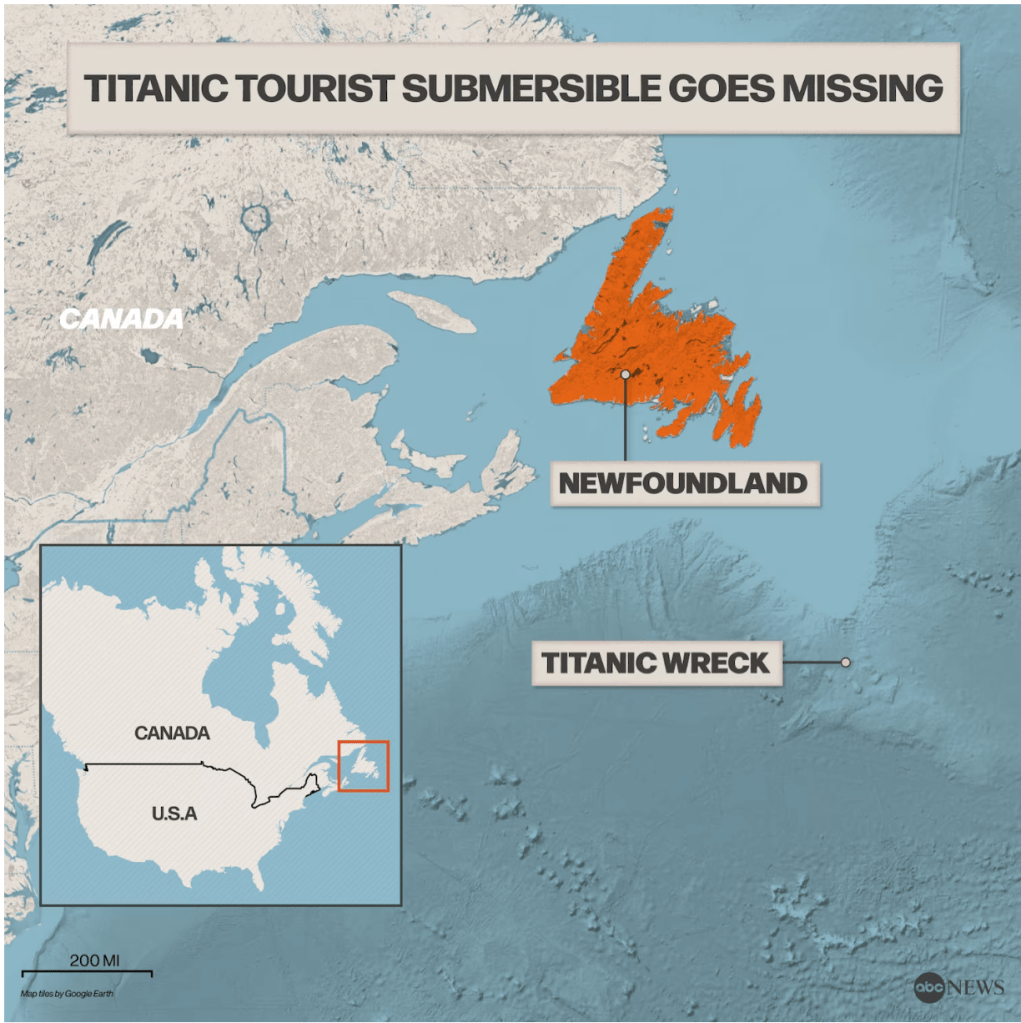

Urgent hopes to discover the five passengers tragically killed in the lost submersible off the shores of Newfoundland spread with compelling urgency across global media after the Titan Submersible lost contact with those on land. The disappearance of the crudely-designed submersible that Stockton Rush had claimed would offer a voyage to the ruins of the great tragedy of the twentieth century had exploded from the undersea pressure it endured as it descended to the wreck of the Titanic. The voyage had tempted fate as a disaster in the making. fell off of the global map, venturing deep, deep underseas. The craft’s tragic disappearance quickly dominated global media with an odd urgency of portentousness fed by the image of a renegade entrepreneur who seemed, despite his worldly wealth, to be courting disaster, in braving a new frontier of an improbably untouched wilderness. Although no bodies or skeletons remain on the Titanic’s undersea ruins, the loss of life that was itself transformed by newspapers into a traumatic site of global mourning and tragedy was eerily replicated. What Rush and his company, OceanGate, had promoted as an ability to transcend a classic icon of death, or at least carry paying observers to see at first hand, was a project he pushed even while making the deep diving sub out of experimental materials, without any third-party oversight, out of the robustt sounding materials as carbon fibre and titanium.

The wreck of the Titanic is an icon of unbearable loss, the scale of whose unexpected destruction is an icon of loss that continues to attract curiosity as it still fails comprehension for many as an epic tragedy. The promise to revisit the unspeakable pain of ruins long lying on the ocean’s floor was perhaps a form of triumphal return. It had been promised to a once-in-a-lifetime underwater voyage, by new technologies, if one with origins in the early twentieth century diving bell. For Rush’s small pod-like vessel several feet in diameter was fitted out as if inversely to a stratospheric balloon, promising take one to depths at which no humans had traveled, as if to a new frontier of utter darkness, removed from terrestrial light. But the hubris of visiting the technological disaster of the Titanic–a primal scene of the mid-twentieth century, which Rush now promoted as a disaster tourism with more than a bit of Jules Verne in it, to the confines of the known, equipped, with the self-assurance that spurred his confidence to try to push limits. Rush had assured his coworkers and subordinates that he would undergo a safety assessment of the craft–he was aboard it, after all, and claimed in board meetings about safety concerns had proclaimed “I have no desire to die,” arguing the deeps dive was “one of the safest things I will ever do,” that suggests a deep self-deception terrific in its determination to escape outside oversight. As much as the name of the Titanic promised to face the “titanic features of the wild” in the manner of the American naturalist Thoreau argued met our “needs to witness our own limits transgressed,” every schoolboy’s dream, and Rush seemed so convinced “I understand this kind of risk.” Yet although the vessel he piloted had made the trip down to the deep-sea ruins some thirteen times before, the degraded state of the hull caused it to implode suddenly at 3,000 feet depth suggested “sustained efforts to misrepresent the Titan as indestructible” animated Rush, driven not only to explore the deep sea ruins, but resist registering the craft to any nation to erase regulatory oversight: the dive in international waters evaded all governmental oversight, suggesting the fault lay not only in a “bad actor” possessed by delusions, but abilities to elude government agencies in a hot market for deep-sea exploration.

Indeed, the picture provided by a whistleblower who was far more trained in underseas missions suggest that the degraded nature of the hull that was not only exposed to deepsea pressures, but to face the winter conditions that could have compromised the composite hull, was prominent tin the number of safety concerns many felt in the submersible community, but which Rush tried to shirk off. While not diabolic or nefarious, a desire to achieve not only the insurmountable dangers of deep-sea exploration, or to “touch death” by visiting the deepsea ruins of the Titanic at first hand were animating Rush’s apparent obliviousness to oversight, and intense silencing of executives and employees to raise concern about the absence of inspectors but insistence to dive to unprecedented depths for financial gain led Rush to silence the experts that he employed, and retain the “experts” h needed for window-dressing to add public luster (rather than real oversight) to the mission.

Over the four days of panic that rescue forces and underseas divers searched to map traces or survivors of the imploded submersible, hoping that the children at least might be living, somehow, trapped in safety compartments beneath the sea, as we wondered how legal parameters on deepsea travel were avoided, we rarely heard from or about whistle-blowers who had long raised questions bout Musk’s overeager plans, trying to alert the very workplace safety regulators–OSHA; –that Donald Trump is, with eager encouragement from the business world–trying to limit and erode. For OceanGate’s quite sturdy Director of Marine Operations, sea-going Glaswegian David Lochbridge, who had worked with a range of submersibles for the Royal Navy and then as a pilot of submersibles in the North Sea, was shut out of the launch of the Titan: he was indeed silenced, and forced to watch the arrival of the titanium caps on the ends of the lost submersible as they returned to shore with everyone else. or if Lochbridge had promptly alerted to the design dangers of the tiny submersible oddly named the Titan,-as if it were the lesser cousin destined to meet the Titanic. The underseas engineer wrote promptly to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration–OSHA–in the United States, who themselves had alerted the U.S. Coast Guard. Yet OceanGate lawyers were set like attack dogs: they insisted that he pay $10,000 for compromising their project, and asked he drop his complaint immediately, charging theft of intellectual property. It got only worse: “From the initial design, to the build, to the operations, people were told a lie,” the expert pilot ruefully remembered. The charge of a theft of Intellectual Property that OceanGate was ready to lodge was, of course, entirely bogus–the IP was nonexistent, as the submersible was not able to endure such high pressure, and the problem was poor engineering rather than theft of trade secrets.

The carbon fibre hull built by the University of Washington Applied Physics from 2019, however for a hull designed for constructing “the shallow-water vessel” called Cyclops 1, made from different entirely materials–steel instead of the carbon fiber as was the case of the hull of the Titan–for diving 500 meters or 1,640 feet, not the 12,500 feet the Titanic lay (“APL-UW expertise involved only shallow water implementation, [and] the Laboratory was not involved in the design, engineering or testing of the TITAN submersible used in the RMS TITANIC expedition,” wrote the executive director of the UW Applied Physics Laboratory in a June 20, 2023 to distance himself from the OceanGate disaster into which he feared his laboratory was implicated, claiming it only offered its services for “shallow water implementation.” Yet Rush was explicit in noting that the college’s broad background in ocean engineering to develop “fixed and mobile ocean systems” for “deep ocean exploration” was always OceanGate’s final goal, and the laboratory claimed experience conducting research on the deep ocean floor that no doubt attracted Rush in the first place, as he sought help for OceanGate to build a submersible that in “the development, construction, launch, recovery, test and analysis of a deep-ocean, manned under-water vehicle.” Rather than rooted in trade secrets that defined the enterprise of deepsea exploration, the carbon fiber hull, designed as if it were indeed a voyage to another planet and inexperienced space, recalls the Carl Sagan image sent to outer space for extraterrestrials, more than the ability to withstand tons of pressure, and multiple flaws in its assembly to withstand the pressures most engineers would quickly realize.

The confidence game that Rush was able to While David Lochbridge and his wife called OSHA every few weeks to alert them to the cracks, pops, and delimitation of the carbon-fibre hull that had been specially built for the submersible’s descent and the glue that bonded it to the titanium rings, by December 2018, Oceangate legal team demanded Lochbridge and his wife drop their complaints and the observations they offered on the plans for descending in the submersible. The legal team successfully delayed investigation of the craft that had never been certified by any third-party organization, as Lloyd’s Register or the American Bureau of Shipping, but was allowed to descend in international waters: the lawyers deflected any investigation by OSHA by charging Lochbridge with appropriating trade secrets, fraud, and theft; he had sought in vain the whistleblower protections from OSHA that never arrived-even as experts at the Marine Technology Society joined the DMO in raising safety concerns about the safety standards for the titanium hubs, evading the industry standards in March, 2018, ways likely to set back the entire industry of underseas exploration by “negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.” While the cute submersible was promoted as able to navigate safely in any aquatic environment–but little intellectual property or “trade secrets” worthy of the name.

The questions that had been raised about its joins of tail cone or porthole and the degradation of the lamination of the carbon-fibre material, not used in arctic conditions, in winter weather of the waters off Newfoundland evaded the regulatory frameworks in place for national or international rates. Did Rush realize that the lack of oversight in international waters off of Newfoundland where the Titanic had previously sunk allowed the escape hatch he needed to press full speed ahead with plans that many doubted would be able to sustain deep-ocean pressures, let alone those on the ocean floor? The Titan, of course, never reached that ocean floor destination, as it had advertised.

Experts Worried the Laminated Carbon Fiber Hull would not Withstand Pressures on Ocean Floor

This was not under the radar. Ocean Governance was evaded as Rush was working without any oversight to fabricate a submersible he claimed was able to withstand underseas pressure based on his own engineering training alone, and his zeal to conduct underseas missions at the ocean floor. By insulating himself with pseudo-experts–from Pierre Nageolet, working outside of deepsea protocols in place for some time in engineering communities, and silencing his whistblower by intimidatory tactics of actual or threatened lawsuits, who he quickly sacked without grounds, And while the U.S. Coast Guard has determined that the almost instantaneous explosion of The Titan, the submersible Rush helped design and whose construction he single-handedly supervised and oversaw resulted from a failure in the glue joining the hull and titanium ring, or the carbon fiber hull’s delimitation as a result of wintering in the north seas, the simulation of how the submersible en route to carry passengers to the ruins of the HMS Titanic after an hour and forty-five minutes may have been a “painless death,” the four days of panic as to its fate conceal the deep dangers of lack of safety oversight or regulations in an almost unregulated search for underseas minerals that seems to have driven Rush’s rather single-minded pursuit of a way to explore underwater canyons on the ocean floor and deepsea territories long hidden to the human observer.

The exploration of the underseas, as much as following Jules Verne’s nineteenth century adventure books, was driven by a growing market for mineral and energy speculation as much as personal glory. If the truly catastrophic implosion of the submersible lasted but milliseconds–too quick of the mind to process, per YouTube sensation Dr. Chris Rayner, who has most recently piggybacked on the global catastrophe, asserts. If the hull collapse may have been preceded by squeaks and pops that inspired panic, the possible site of collapse and structural failure—the viewport, the adhesive seal between the titanium end-caps and the collapse of the cylindrical hull–resulted from evading oversight of nautical regulatory bodies, perhaps steeped in the ethos of American individualism, but driven by a market for offering new platforms of first-hand underseas oil exploration to oil companies and engineers in search of deep sea minerals–the very community of engineers Rush hoped to win over for the benefits of the submersible as a mode of underseas mapping. The need to evade the law of the seas, and situate the site of exploration in international waters, was situated at the ruins of the Titanic to attract worldwide media attention, and pull other outsiders into Rush’s outsider project, evading any regulatory commissions or guidelines on passenger safety. All of Rush’s passengers had of course signed release forms prior to boarding the Titan, and the pressures to which it was exposed that reached 5,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. Carbon fibre was an “unpredictable material” all along for such depths of 3,000 feet, if not an impractical one, raising questions of why Rush was so committed to allowing multiple untested features to remain before performing the dive, advertising the ride to passengers he would take to their deaths as entirely safe.

1. The romance of the underseas exploration was clearly intensified–and made attractive to financial backers–by the nature of its destination: the ruins of the Titanic–and, however paradoxically, the ability to transcend death. The expression of a desire to transcend perceived boundaries was communicated to Stockton Rush as a boy in Walden, or Maine Woods, where Thoreau waxed ecstatic at an almost mythic awareness of something “vast, Titanic, such as man never inhabits”–channeled by the original transatlantic transatlantic voyage that mirrored the telegraph to the Newfoundland coast, before hitting an iceberg, to the search of the steel ruins still lying submerged undersea. Rush sought to break new boundaries of the globalized world by the venture of OceanGate, as if breaching new frontier of exploration, if not an affirmation of personal vitality and renewal by traveling to a space “such as man never inhabits,” where “inhuman Nature has got him alone.” It is impossible to read the ecstatic revery of how Nature moves man and “pilfers him of some of his divine faculty” as an open invitation to descend into the deep of the ruins of the Titanic, to relive the massive tragedy of the first decades of the twentieth century, as attempting to reconquer time.)

Stockton Rush had recuperated a narrative of canasta with deep roots, if one that was promoted in the recent films that had become museum shows and even adventure rids at amusement parks–but this, as if in contrast to studio recreations, was promised as the utmost exhilaration of the real thing. But was it ever reality, so entangled was Rush’s promise with beliefs in transcendence that trained generations of readers of Thoreau to search for sites of transcendence beyond our abilities? Or is the fiction of transcendence that Rush promised to paying customers, and that Thoreau had so memorably inspired, gained new meanings in a world defined by globalization, where the voyage of Stockton Rush into the depth of international waters, outside legal oversight, been tainted by the map of globalization, and indeed inspired by the abilities to transcend our own known limits were newly conflated with the transcendence of legal regimes, and indeed the transcendence of limits of deepwater exploration for energy reserves that oil and gas multinationals hoped to extract from the deep seas, but lacked the requisite technology to survey? For the voyage in the modern diving bell was indeed a trial balloon to industries eager for tools of underseas mapping promising greater precision, that it isn’t unlikely to think Ocean’s Gate was eager to market, for far more money than offering exerting underseas joy rides of disaster tourism. And a very different if related sense of “Titanic’ that Thoreau used in Maine Woods, of something that “was vast, Titanic, and such as man never inhabits” where “Nature has got him at a disadvantage” might better describe the deep seas.

The bravura of descending by a diving bell had been memorably used in the mid-century novel Dr. Faustus by Thomas Mann as an aesthetic experiencetragically tainted by hubris from the start. Mann seeks to express the Faustian goals of his hero, Adrian Leverkühn by the diving bell he travels undresea to witness unknown monsters in perfect submarine darkness, far from humanity, in the diving bell that prefigure the ecstatic aspirations to symphonies he hopes to create. The trips with Dr. Capercale to the underseas world with a fictional scientist, as pushing the limits of human understanding. Leverkühn claims to have experienced new limits when he descended in the waters off Bermuda, only several sea miles from St. George, in the company of a man who claims to “have set a new record for depth” underwater. Mann’s memorable hero descended in a “bullet-shaped diving-bell” that transcended human limits, descending a if in inverse to the stratospheric balloon it resembled, promised to be “absolutely watertight, . . . capable of withstanding the immense pressures and came equipped with plenty of oxygen, a telephone, high-powered searchlights, and quartz windows for viewing on every side.” If ‘anything but comfortable” they were secure in their descent, “by the knowledge of their safety . . . beneath he surface of the ocean” behind four-hundred pound door, as descending to perfect darkness at 2,000 and then 2,500 feet, bearing 500,000 tons of pressure.

Leverkühn somewhat cozily entertained his friends with gusto of the descent to underseas depths, smoking a cigarette. The voyage was a metaphor for the modern Faustian bargain he made with the Devil, sacrificing human love for his skills of composition. For in the descent to the inhuman realm, he described having gained “glimpses afforded onto a world whose silent, alien madness was justified–and explained, so to speak–by its inherent lack of contact with our own” in the descending chamber, in three hours that “passed like a dream, thanks to the . . . glimpses into a world whose soundless, frantic foreignness was explained . . . by its [absolute and] utter lack of contact with our own:” “all around reigned perfect blackness” akin to “darkness of interstellar space.” Diving bells not only provided visits to witness sunken wrecks off Bermuda’s coast on the ocean floor, but conjured a transcendence of the human, in an unmapped region beyond the limits of the known, traveling 3600 feet below the seas surface in a two-and-a-half ton hollow ball for a half an hour, looking through quartz windows “into a blue-blackness hard to describe, . . . eternally still . . . not quite allayed by the feeling science must be allowed to press just as far forwards as the intelligence of scientists is given license to go.”

Else Bostelmann, Dragonfish or “Bathysphere Intact” off Bermuda (1934)

The images Else Bostelmann offered in scientific periodicals captured the fascination of underseas that colonized the imagination; “the incredible oddities that nature and life had managed here, these forms and physiognomies that seemed to bear scarcely any kinship with those on earth above and to belong to some other planet, . . . hidden in eternal darkness.” The deep sea hid “these abstruse creatures of the abyss” that seem “to have no tie to humanity” provided the first ken of the pleasure Leverkühn takes in flaunting familiarity “his experiences in regions monstrously above and beyond us humans,” plunging with diabolic relish and ease among the “deep-sea’s life grottesquely alien life-forms, which did not seem to belong to our planet.” His friend thinks that the indulgence of these memories seemed “a devilish prank” of “the horridities of creation” able spur him to a new form of composition of the “cosmic music, with which he had become preoccupied,” before World War I, in compositions the narrator condemns as a “sardonic lampoon apparently aimed not only at the dreadful clockwork of the universe, but also at the medium in which it is painted . . . at music” of “a nearly thirty-minute orchestral portrait of the world is mockery–a mockery that confirms only too well the opinion I expressed in our conversation that the pursuit of what is immeasurably beyond man can provide no piety or nourishment.”

The sense of an infernal voyage was amplified in the disaster on the way to visit the Titanic’s ruins. For that voyage was akin to the blasphemic nature of what Mann’s narrator calls a” Luciferian travesty” and blasphemy against the elevated medium of music expressed–or mapped?–by artistic ambitions to transcend the human world. For Mann, writing in global war during the 1940s, the desire of Leverkühn seems one of technology and modernity that might be captured by Adorno, whose music criticism he had pillaged in the novel–deeply human problems of alienation that plagued the mid-twentieth century and Nazi period. These musical compositions, after all, confirm Leverkühn’s own diabolic pact, only hinted at or foreshadowed in the book’s earlier chapters. The imagined underseas voyage was a voyage to the unknown depths of the ocean provides the basis for describing his imagined trips to outer space; the orchestral fantasia suggest horror in the ears of his admiring friend, for a Godless vision to dethrone all religious humanism of a search for music able to describe the terrible marvels of outer-space or grotesqueries of the deep.

The Faustian nature of Stockton Rush’s quest was nothing if not a Faust-like underbelly of globalization, this post argues, piggy-backing on Mann’s shoulders for a bit, from the perspective of globalization and deregulation that open up the deep with even more terror. While Mann will be less a focus of the post, I will follow him in examining and descending into the terror opening up of ideas and imaginations of prospecting the ocean’s floor multinational firms of opened by hopes of prospecting. For the huge bonanzas of extraction have opened up new deepwater spaces, as access to the deepwater reserves of energy or rare metals provide secret promises to an eternal ability of extraction, a search for energy sources that is a broader Faustian problem by Big Oil we can only see, but is almost engraved in the desperation on his face as he readies to plunge to the ocean floor.

The Faustian nature of the deepwater voyage within the curved steel walls of a cast iron Bathysphere had been devised to protect the biologist William Bebe and his assistant from the dark, boasted to guarantee against the heightened pressures of ocean depths few had experienced or would survive. The thrill of the deep seas plunge that exposed the vessel to such enormous atmospheric pressure left in the composer the sense of risk in his skin–a “prickly sensation that came with realizing one was exposing to sight what had never been seen, was not to be seen, and had never expected to be seen” whose unavoidable “sense of indiscretion, indeed of sinfulness, could not be fully mitigated and neutralized [even] by the exhilaration of science.” Ocean scientist and engineer Bebe gained nearly global attention for his exploration of deep ocean life behind two fused eight-inch quartz portholes in 1934,–a new horizon on uninhabited worlds electric light was able to reveal to human sight as a technological wonder of observation, a new sort of scope regime. The biologist reported observations be telephone to a nearby boat–for Mann, a bestiary of “mad grotesqueries, organic nature’s secret faces: predatory mouths, shameless teeth, telescopic eyes; paper nautiluses, hatchetfish with goggles aimed upward, heteropods and sea butterflies up to six feet long.” The descriptive relish of revealing this hidden bestiary cannot capture the strangeness Else Bostelmann imagined for National Geographic of the deep sea life illuminated in the Bathysphere she never participated. But thirty-five pioneering dives were conducted, many years after the Titanic sunk in the far colder waters off Newfoundland, its starboard air chambers shattered as they hit an iceberg.

The transport Adrian Leverkühn imagined might be conveyed in Bebe’s ambitions to view “here, under a pressure which, if loosened, would make amorphous tissue of a human being . . . here I was privileged to sit and crystallize something useful.” The sturdy Bathysphere set records descending to 1,200 feet; diving spheres soon plunged to 4,500 ft., if only a third of the way to the 12, 500 feet at which the Titanic had sunk. The deepwater voyages became the subject of a popular film by 1938,–perhaps as popular as the recent blockbuster of Titanic’s sinking–and a spectacle of the revelation of the uncanny creatures of the Deep Sea, capturing the excessive hope that in part animated Stockton Rush in his own fantasia–if it didn’t hint that he wasn’t driven only by science or exploration, but monetary profit, revealing the huge financial benefits of surveying the underseas world in an age of globalization that threatens to expose more and more underseas minerals to hopes of extraction, in a Faustian bargain we have not yet come to contemplate fully but is increasingly waged in maps, and cartographic precision to map sites of extraction underseas.

The absolute alien nature of the darkest reaches of undersea life must have epitomized the Faustian bargain of Leverkühn, eager to court danger of the inhumane for renown. Thomas Mann was in fact describing the underseas as an inevitable attraction for the composer who made a deal with Satan in Dr. Faustus (1946), one imagines akin to the compulsive attraction with which Stockton Rush persued th e deep. The plunge below 4,000 feet was sufficient other-worldly to recall a pact with the devil, as the idea of descending and returning to the underseas graveyard of the Titanic’s ruins.

Yet the attempt to market underseas heroism of tempting fate that Stockton Rush offered the passengers of the submersible he called ‘Titan’ never did reveal “what genuine underseas exploration looks like;” its passengers all met with death. Mann described the eery inhumanity of a descent below 2,400 and 2,500 feet, opening “an interstellar space unvisited for eternities by even the weakest ray of sun,” to be “examined under a brutal artificial beam, . . . brought down from the world above” as a bridging of life and death. Rush’s unwarranted promise of survival in such a transit to the deepsea ruins is however akin to how Leverkühn courting exhilaration before “forms and physiognomies that seemed to bear scarcely any kinship with those on the earth above and to belong to some other planet,” unveiling not “products of concealment . . . hidden in eternal darkness” compared only to “the arrival of a human space-craft on Mars.” But what Rush promised was underwritten and sponsored by a deeper diabolic pact of hoping to sell the submersible to multinationals after its media success for use prospecting oil and precious metals below the sea we are unable to map.

Rush’s voyage, boosted by the James Cameron film Titanic, benefited by being billed as a cinematic fantasy of reaching the inaccessible. Leverkühn’s desires were an overcoming of death–or a desire to terrify his audience by courting death, terrifying them, if this does not have the desired effect. Rush’s motives were driven not only by audacious daring, the bravado of an explorer worthy of his own waspy name. But he must have been attracted, horrible as it is to say for the memory of those who perished with him on what they believed a ride to be remembered, by global pressures of energy markets to define new horizons of energy extraction, as much as to open horizons on the ocean floor for human viewers. For the difficulties faced of mapping and identifying sites meriting investment for offshore energy exploration, more than the vicarious thrill passengers who helped bankroll his initial maiden voyage imagined. The hopes to visit a global destination few had visited personally–in the company of someone who in fact had–was a proof of product to oil companies, who might line up with offers of employing the deep-sea submersible from OceanGate as a means of furthering claims of offshore speculation. Perhaps this made Rush’s project all the more Faustian, if not an image of the Faustian deals of globalization.

Rush promised as much to paying customers, but minimizing the risk dramatically by dressing it in science . Diving bells were used to stage rescue operations of underseas crews had by the 1940s became a thrilling forms of underseas tourism near Bermuda, verging on disaster tourism, offering transport where no one had gone before, effectively promising a trip to the beyond–one that was metaphorical, but provided the eery sensation Mann wanted to capture of to the beyond and back.

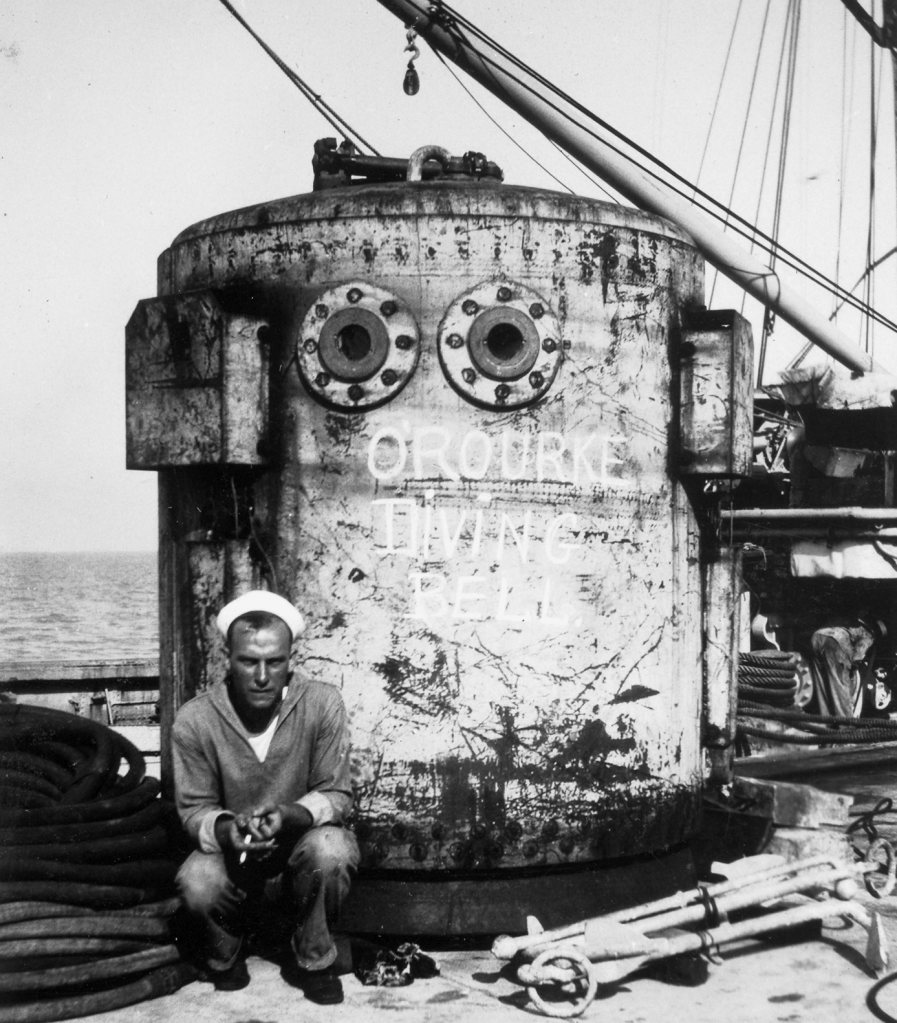

Diving Bell, c. 1939/U.S. Navy

The loss of the Titan submersible could not but seem a tragic echo of the tragic loss of life, a century ago. Staged as a victory over death, or a transcendence of the tragic fate of a historic sunken ocean liner, the site of romantic heroism on which so many passengers perished, the explosion of the Titian became moment of loss that breifly reprised the way that the Titanic’s sinking defined global news as it ran on the headline pages of newspapers worldwide. The sinking of the Titan invited multiple diagnoses of the evasion of regulations by the owner of OceanGate, whose eagerness had led him to boast of breaking rules to pursue innovation: the sinking of the submersible, whose windows were not built to code, may seem dark revenge for a scheme whose hubris extended to charging passengers the rate payed for that fateful transatlantic luxury cruise, just off of the national waters of the United States or Canada–but lying just within the later declared Exclusive Economic Zone where industry was encouraged to explore, but had no ability to map sufficiently.

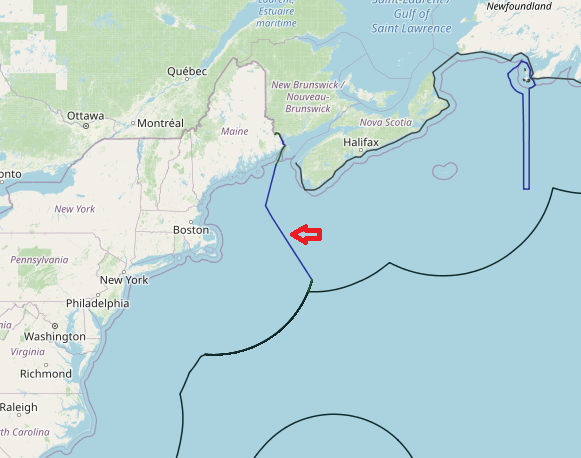

While we see Rush as the victim of his own grandiosity, deviously skirting regulations and seducing wealthy customers with promises of underseas travel that seduced them by his grandiosity, we have yet to place Rush as a victim, in some sense, if a canning con-man who sought to profit from extractive industries by the promoting the spectacle of underseas travel through a submersible he claimed might have multiple business uses, beyond adventure tourism. The proximity and distance of the undersea ruins of the ship–on the edges of national waters, the deepest point in the near offshore, but outside of the national jurisdiction that would have demanded the submersible to follow safety procedures–made it ideal for Rush to conduct his costly experiment to prove the value of OceanGate’s submersible to explore the unknown ocean floor without government oversight–in international waters, not subject to regulations of Laws of the Seas and other norms of maritime law, beyond domestic waters subject to national law, lying just outside sovereign limits and off of the continental shelf, as well as in open waters removed from other ships.

The “offshore” status of Rush’s plan to explore the Titanic at site deep underwater both guaranteed international attention for his endeavor, effectively providing a platform to advertise the expected success of maneuvering on the ocean’s floor at abyssal depths required for mineral prospecting, but cast the mission not as one of discovery or of staking rights to land, that might reveal the true purpose of its technologies, but provide an unmonitored site to gain global attention that might be transferred to the private sector–and even might ignite a bidding war for the tools and technology he developed or imagined might be within reach. Sadly, the submersible’s rapid implosion revealed its shell unable to withstand not the extreme pressure at depths of 12,500 feet underwater where the Titanic’s rusted hull lay, or, perhaps to even approach them. The promise that Rush made to show the world”what visiting the depths of the ocean can–and can’t–tell us” about the value of underwater minerals of industrial value, if cast as a bravado attempt to show the world and television spectators “what genuine underseas exploration looks like” was not successful, even as a model of disaster tourism, let alone for the type of private prospecting he envisioned it to be.

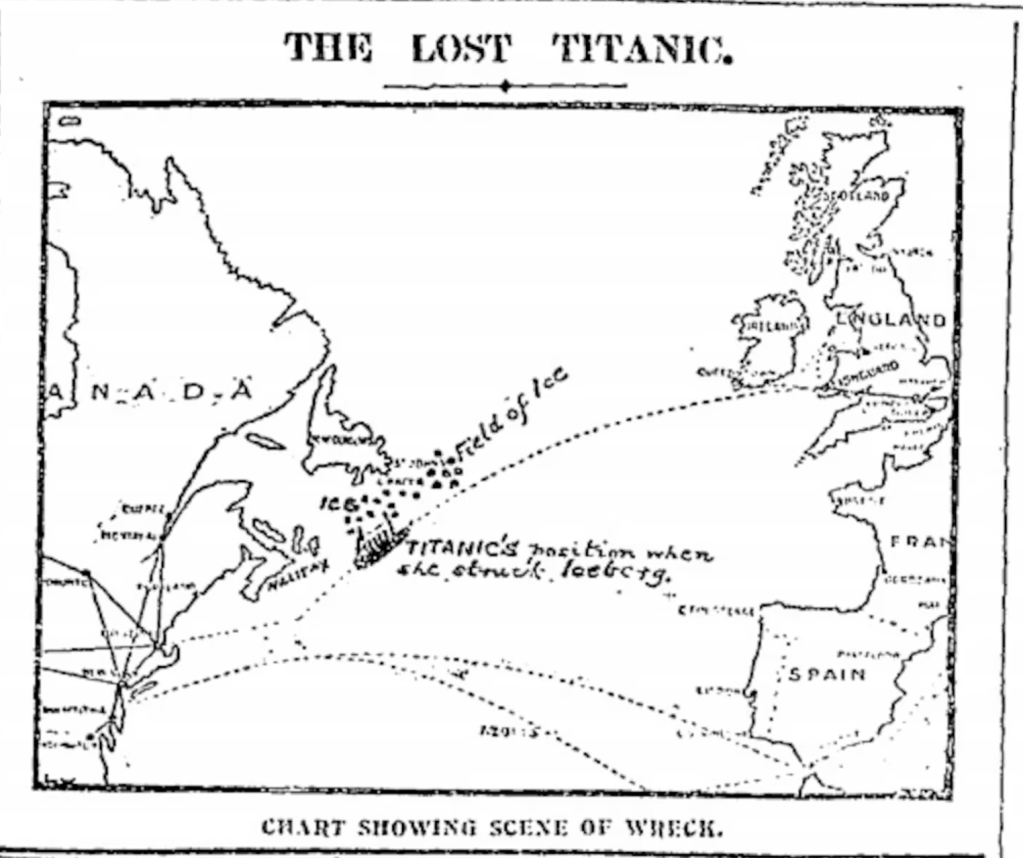

The loss of that earlier ship in the abyssal depth of the waters offered an occasion of global mourning: the location of the wreck of the liner which sunk hours after its hull had hit an iceberg, slicing a hole beneath water-level, tearing openings across five watertight chambers as it traveled at high speed, was an emblem of incomprehension; its sunken geography is an emblem of loss to which we return, if not physically, whose inability to locate and discover. The mystery endured in an era of global mapping, if not became more fascinating, as the drive to map the ocean floor left the ship abandoned and inaccessible–unmapped, even by the logic of bathymetry–lying far deeper than humans could arrive. If the Titanic disaster occurred on the verge of the confidence in imagining the unimaginable–a complete mapping of earth’s surface and its depths–after Sir John Murray and Johan Hijort noted the presence of a mid-oceanic ridge in the mid-Atlantic seafloor, by 1910, describing trenches and mid-ocean ridge, the depths seemed suddenly far more opaque and even removed by the terror of the massive loss of life of the well-to-do passengers who drowned, helpless, deep below the ocean surface’s freezing depths, surviving on row boats available for those able to commandeer them, others waiting in chilly unmapped waters off the Dominion of Canada–,

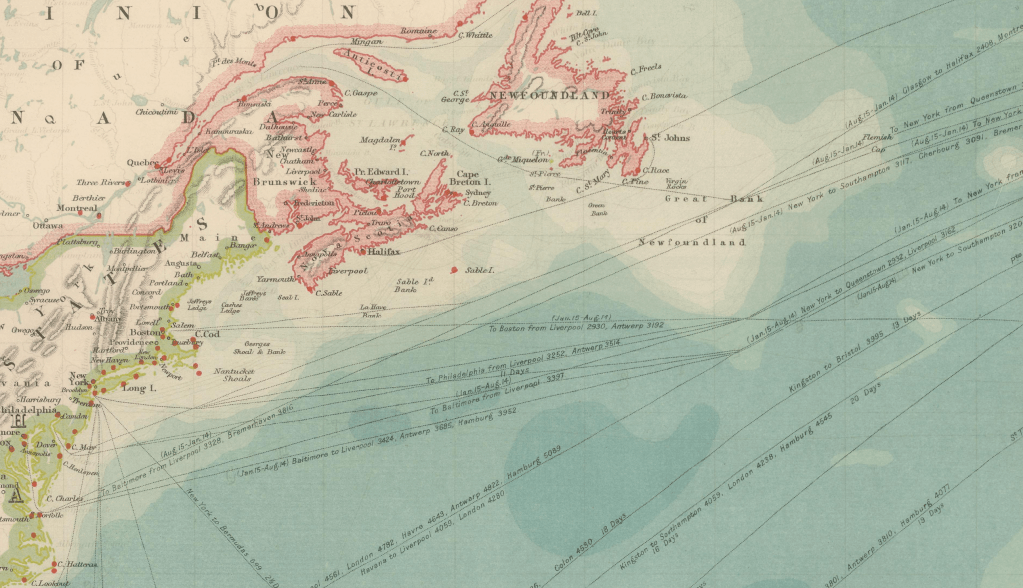

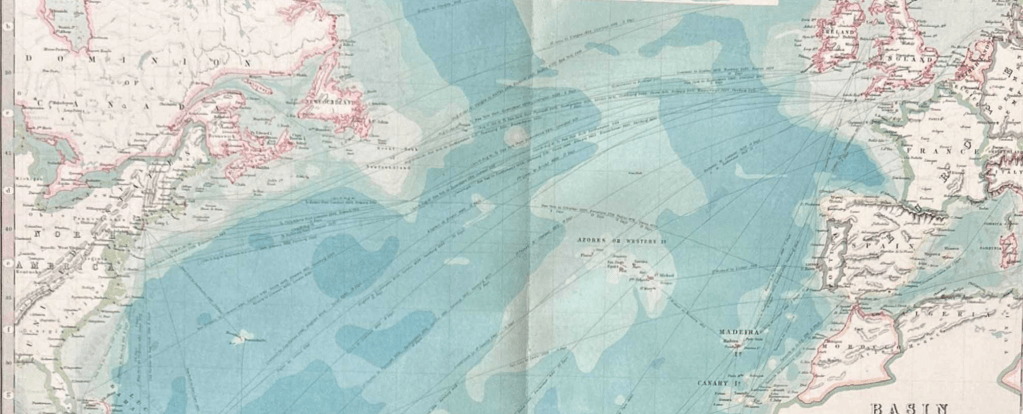

from “North Pacific Basin,” Johnston’s New World Atlas, 1912

having almost completed their traversal of the extent of the North Atlantic passage on an ocean lier whose indestructibility and impermeability was vaunted, before it sunk in the middle of the night.

W. and A.K. Johnston, “Basin of the North Atlantic,” 1910; 1912 publication

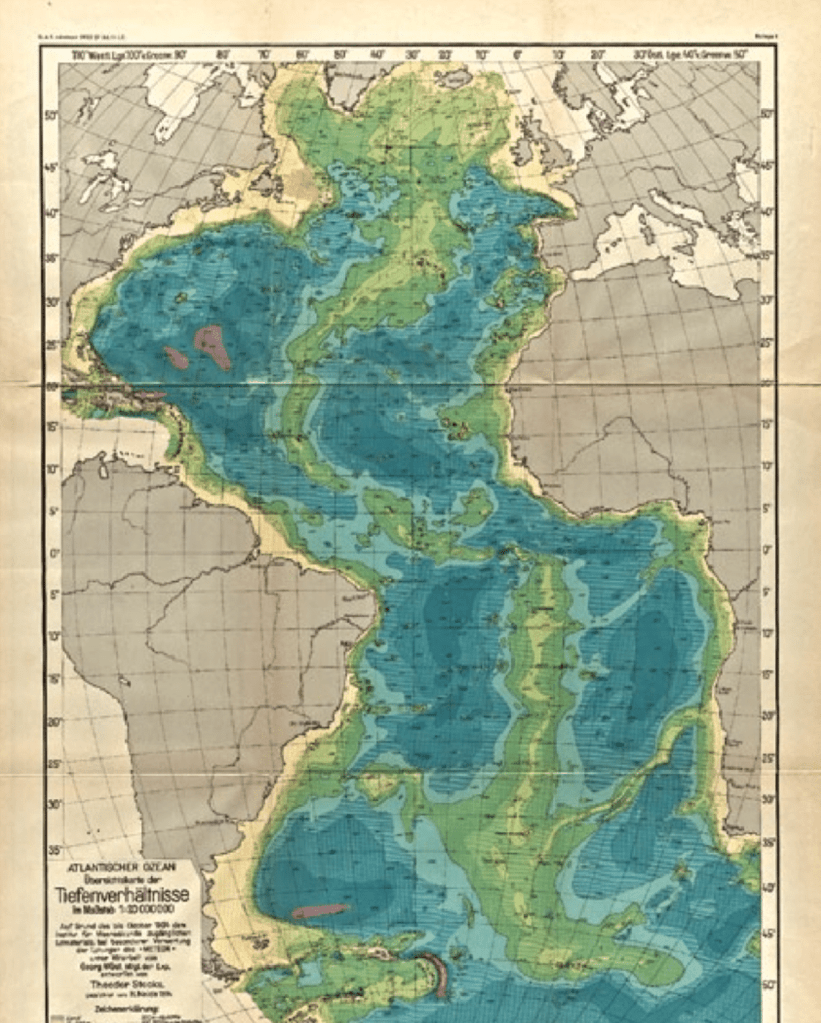

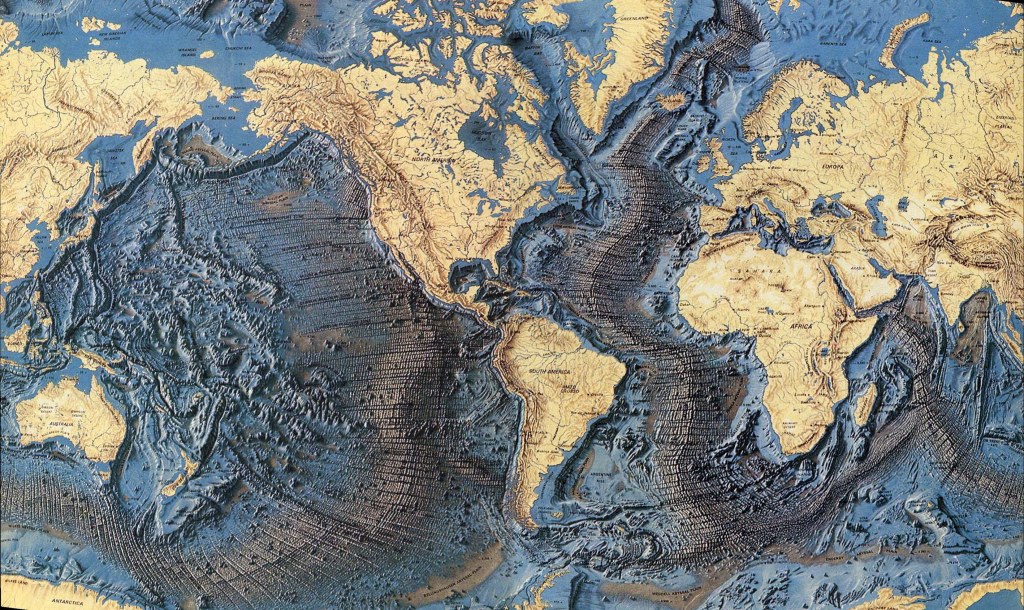

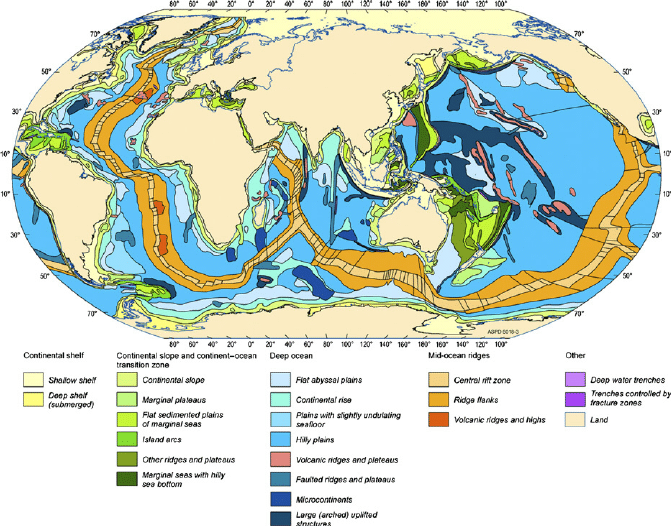

The deepest ocean trenches were discovered and mapped in detail by Heezen and Tharpe by 1977–but the detailing the relief of the oceanic depths that had been notionally mapped from the 1840s by the United States Navy had been begun earlier, before they were announced as fully mapped in the detail we are accustomed to see with such astounding bathymetric clarity.

Heezen and Tharpe, 1977

The first delineation of continental shelves, slopes, and mid-ocean ridges began by soundings of hemp rope, by line and sinker, not acoustic soundings that post-date World War I, but the line and sinker mapping of the ocean floor emerged by the early twentieth century, suggesting a mastery of the ocean, even before mapsrendered palpable the extent of abyssal depth. The maps of ocean currents of the 1840s and 1850s that revealed the depths of the water’s flow were refined in ways that revolutionized perception of ocean bathymetry beyond what Matthew Fontaine Maury begun to map in his rendering of ocean currents by the 1840s, offering early views of the unknown extent of watery depths still not fully mapped–by 1927, oceanic depths appeared in color. The increased mapping of the continental shelf and ocean floor as a goal of prospecting and extraction helped to spur interest, this post argues, of the self-styled “pioneer” Stockton Rush, who sought to grab industry attention of multinationals keen to develop new tools of prospecting the ocean floor–

Mid-Atlantic Ridge Mapped by the Meteor Expedition (1927)

–defining and materializing a new frontier of mapping, even if Rush sold the underwater trip as an adventure in an attempt to bank on the vicarious thrill of discovery. While he diminished risk, the stakes were big for him, as the possibility of such a submersible promised the first hand observation of the ocean floor at unprecedented depths, in an era when we have only mapped a fifth of the ocean floor at high resolution we are accustomed in terrain maps, and the first-hand proximity Rush offered made the voyage of the Titan an experiment and proof of concept for the expanded mapping of possibilities of prospecting for minerals or other products on the ocean floor, allowing visits to be planned to potential sites of drilling, in or outside the Exclusive Economic Zone where mineral rights were able to be bought if they were promising. How to know what were promising sites is a quandary of the auctioning off of areas along the two hundred mile perimeter of the continent in March 10, 1983, by a President eager to expand drilling on the continental shelf, that could suddenly be sold beyond the nation’s seaward boundary, at a perimeter of two hundred nautical miles, but had not been able to be examined in the way the sort of submersibles Rush had been keen to show off to the world–and needed to make a spectacular splash by the visit to the most hidden and famous sites on the ocean floor–a location where the ship had famously disappeared from site after being struck in a field of ice by an iceberg that sent it to the ocean floor.

The master death of the early twentieth century was a failure of technology that new technologies of deep ocean exploration that OceansGate offered were meant to be an improvement, and even a triumph over the previous shock at a sudden loss of life. But while we find tragedy in the velocity with which the liner and submersible both sank to the depths of the ocean floor without warning–exactly what the OceanGate submersible wasn’t supposed to do–the ability to descend and vies the ruins billed as a miracle of modern science, and of modernity, a spectacle of the successful use of deepwater exploration to offer a return trip to the liner’s ruins, and rewrite its tragedy as, if not a comedy, a triumph over the stakes of high-pressure underseas travel below 10,000 feet.

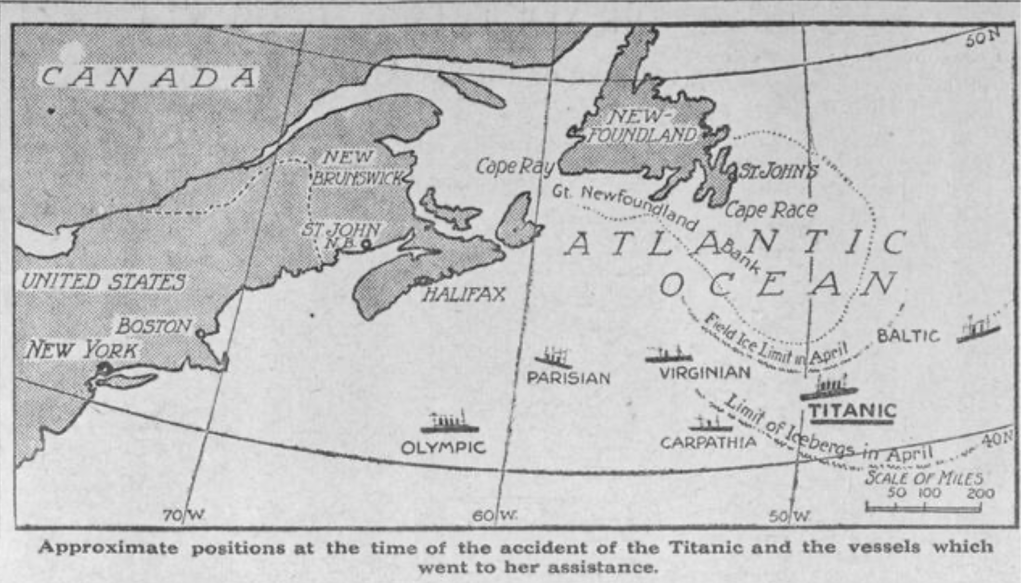

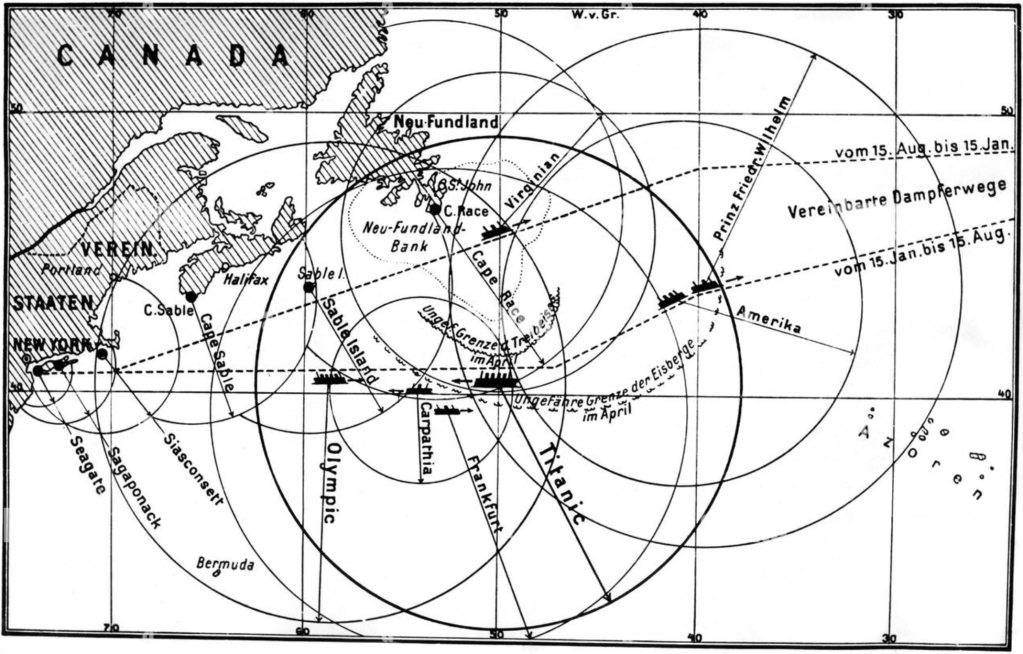

Ships in Range of Titanic’s Course in 1912

The loss of the Titanic to the depths of the seafloor was famously shared over the news and wire services, lost even to later acoustic mappers on the ocean floor just off the continental shelf–beyond the Exclusive Economic Zone of the United States Ronald Reagan opened to underseas prospoecting in 1983. If the declaration of an “Exclusive” Economic Zone sought to promote offshore drilling the Carter administration had warned against, the executive order was unableto materialize a windfall of economic offshore wealth as expected. The sinking of the Titanic remained a tragedy of proportions unabated by the excitement of offshore prospecting in the EEZ, exposing to vision a region of the ocean floor that lay beyond the reach of high resolution mapping tools, and could not be reliably mapped as a surface for prospecting, even if the claim of exclusive rights to prospecting doubled the landmass over which the government had authority on dry ground, opening up a vision of future claims to prospecting that might be eventually mastered.

We were frozen before screens following the submersible’s grim fate after it had disappeared and lost contact with shore. Even as the disappearance of the Titanic made us wonder for years about the ability to lose something of such scale and large dimensions, reduced, by the scale of the oceans themselves. Writing about the loss of the Titanic, and trying to grasp it, had, of course, been a way of coming to terms again, perhaps, and the mission of the Titan may have been showcased as an attempt to come to terms wiith what has been called the “master-death” of the early twentieth century, confronting America with death on new scale a sudden blot on prewar peace. The sinking of the Titanic is blamed due to an absence of planning and preparation, but it was also a nightmare of similar proportions to the romantic fascination with the ocean and its dangers–the fascinating horrors of deaths by iceberg in poetry from Coleridge to William Vaughn Moody, of glaciers that “fling their icebergs” to the ocean, or, after the Titanic disaster, Charles G.D. Roberts, waves hit their base, “lisping with bated breath/A casual expectancy of death.” For the fears of sudden “huge, dreadful, Arctic and Antarctic icebergs” that Whitman evoked were impossible to map, and left the liner not eh ocean floor a ruin that we couldn’t map for years, a huge ship of industrial scale lying on abyssal ocean floor as a death unable to be written, engraved, or mapped–or seen.

This was the invitation, of course, that OceanGate offered to its customers–and warranted the substantial dollar fee to be paid up front–to witness at first hand the tragedy of a sunken geography by the thrill of vicarious spectatorship of the loss of losses, and overcome it, more than to experience it in real life. There was a spectacle on offer, and an ability of secure viewing –or the hope of one–to map the loss of losses by experiencing it at first hand, if one dared, and the founder of OceanGate, Stockton Rush, was an Ivy League educated entrepreneur who radiated excitement of knowing no bounds so enthusiastically to erase the fears of courting tragedy by visiting that sunken geography seen cinematically that must have made the prospect of underseas voyage seem newly possible. We knew the Titanic’s location on the ocean floor, as well as a site of dramatic loss and human tragedy. The thrill Rush communicated of a visit attracted four passengers to copilot to the hidden geography of loss where decaying ruins of the luxury ocean liner lay where the ruins of ocean liner lay moored on a reef. Rush boasted to the passengers that his Titan submersible was able to reach huge depths–13,1223 feet, per OceanGate, a threshold that included but was not much greater than the 12,500 feet below sea level of the reef that was a sunken ship, as if to be able to experience vicariously the scale of destruction lying on the ocean floor from behind thick windows. None anticipated at the cost they paid that they would ever be in danger.

But the underseas disaster became a pressure point of trust in age of anxiety coexisting with hesitation. Did the attraction of the decaying ruins lying on the ocean floor, viewable in video online, but generating a desire to see and experience, an emblem of loss that set new thresholds for the losses of the rest of the twentieth century, still challenges one’s ability to write about, map, or describe. No map is sufficient, nor was any map commensurate with the apparently compulsive repetition of a disaster at long unimaginable bathymetric depths. The incongruence of luxury travel and death in “reality” disaster tourism to a wreck 3,800 meters underwater in international waters challenged narratives, to be sure, but also reveals something about the dangers of the absence of regulation in an open market that results in the increased fraying of trust, and the insecurity of even advantages of extreme wealth, in the search for capturing heightened suffering, to be sure, but to explain the global contradictions of extreme wealth, for super-wealthy who traveled to the site of their death.

The implosion of the unready craft that killed all six of its passengers seemed a tragedy waiting to happen, but the repetition of the tragedy of the transatlantic voyage, combining luxury disaster tourism this time with an actual disaster, leaving its cracked ruins lying on the ocean’s floor, echoed the ship of dreams that once carried philanthropists, capitalists, businessmen, majors, government ministers, lawyers, fashion designers and socialites to their deaths, as circumstances turned its voyage into a tragedy of immeasurable loss, left lying stationary on the ocean floor, as if a tragedy that took place out of sight, outside maps, of heightened drama and unimagined as it was not seen or registered or documented, in ways that have led it to be so compulsively reconstructed–even to be visited by the Titan as a possibility to “step outside everyday life and discovery something truly imaginary” from the shared experience of “a dive to the wreck of the RMS TItanic.”

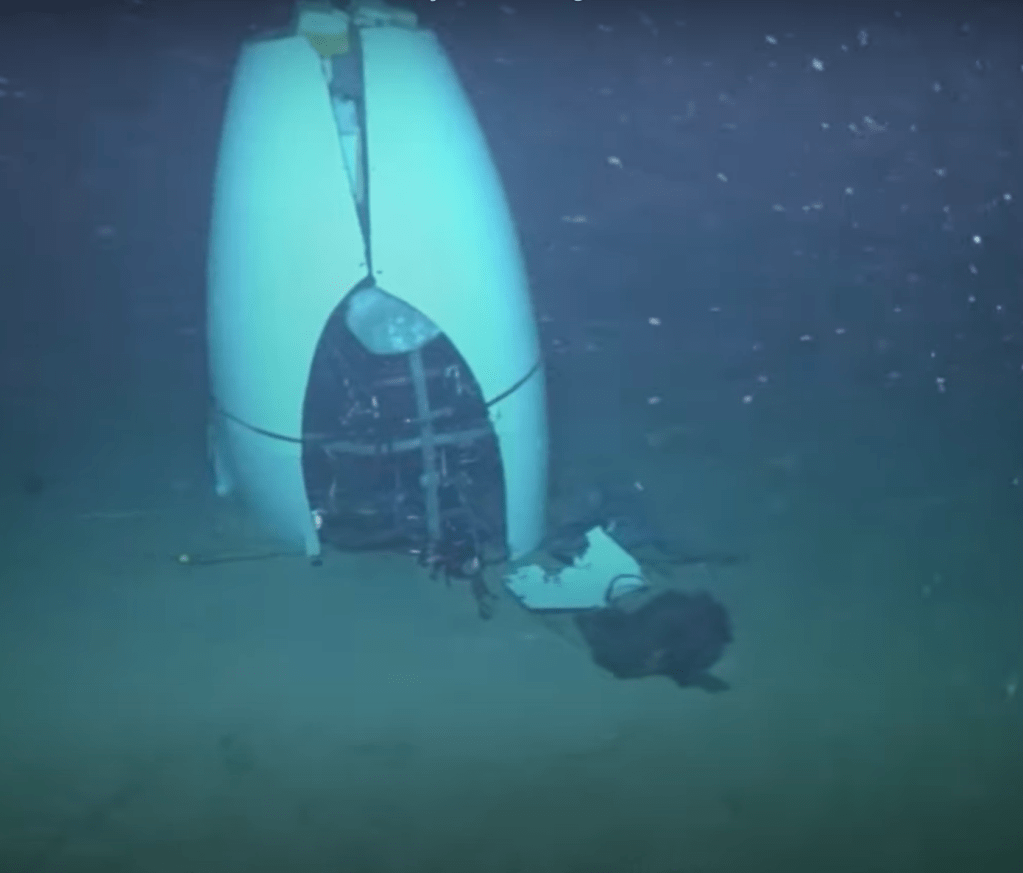

The vast emptiness of the cracked shell of the submersible, destroyed due to its inability to sustain extreme water pressure, suggested something different than the luxury trip of dining, music, and elegance in the end of the Edwardian age,–

–but the terribly cracked fuselage of what seems a plastic vessel that under extreme pressures of abyssal depths imploded quickly, lying in the sand as an emblem of vanity and absence of adequate oversight, and of the dangers an open market of the high seas continued to hold. Even as multiple governments and navies worked to locate the submersible that lay outside American and Canadian waters, outside of the Law of the Seas and off of territorial waters and the continental shelf, the ruins of OceanGate’s Titan suggest an Ozymandian like witness of a venture to reach the ocean’s depths for reasons we have not been able to fully plumb, so easily are we wont to link its poor design to vanity and an absence of convictions, to fail to appreciate the scale of the scam that led to the needless deaths of the gleeful passengers, including that kid who brought his Rubik’s cube and his beaming dad.

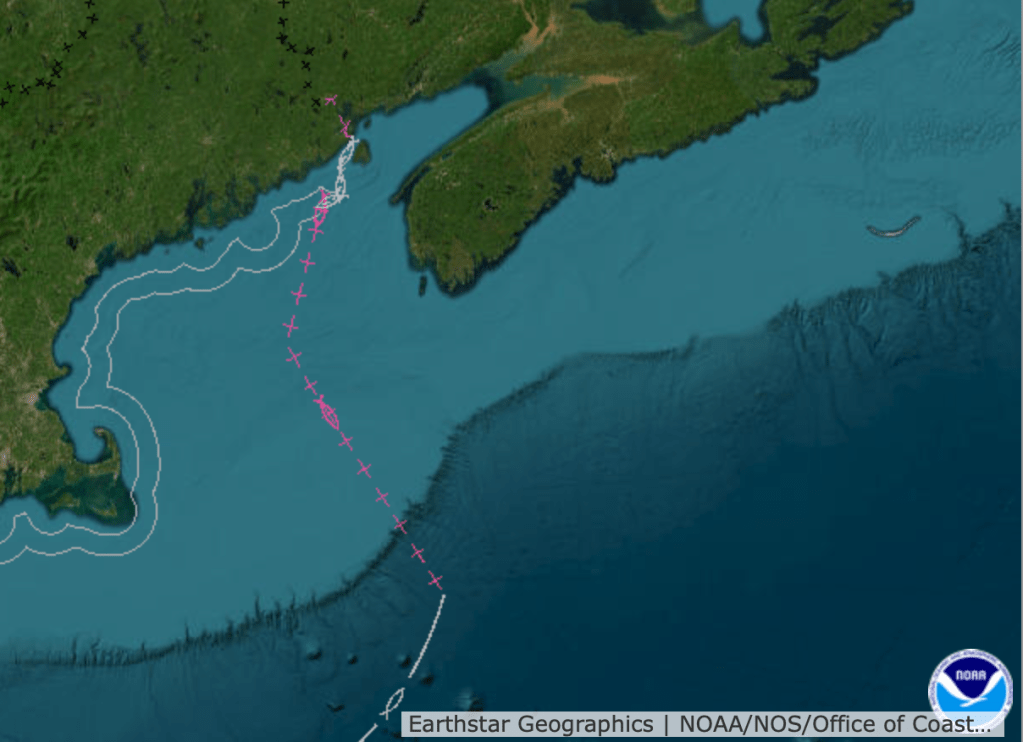

United States Continental Limits and Boundaries/NOAA, Office of the Coast Guard

The global production of maps to try to track its disappearance was, terribly grimly, a tragedy of its own sort–if also, so improbably and devastatingly, a repeat of the trauma of mapping the loss of the ocean liner that sunk over a century ago. For the repetition of a disaster at the site of disaster was so terrible to obscure the interest and intent of the entrepreneur to evade international regulations or the Law of the Sea for the safety of the craft, seeing to development a proof of concept for underseas travel that he sought to innovate, pushing away from precedent with little security or protection for the passengers of his own craft. It may make sense to ask why he did so, and how he sought to prove travels into the depths of international waters, not only in ways that tapped a sense of pathos of the disaster of the Titanic, but the value that he saw in being able to pioneer underseas worlds outside of existing regulated maritime boundaries designed to monitor fisheries and police nearshore extractive industries, in hope to open up a broader map of underseas speculation.

For the sunk wreck of the transatlantic steamship liner has become transformed to an ecosystem teeming with marine life, in the century it has lain underseas, becoming a reef in its own right, but the risks of a visit in an experimental craft assumed a global luster equal to that of the exclusive luxury liner before it sunk in 1912. The Titanic was an unprecedented ship, to be sure–a subject of awesomeness that challenged natural bounds in its own right, attempting rather hubristically to cross the sea without mapping . The ship, whose sunken remains Stockton Rush had hoped to show the paying guests on his submersible, had claimed to offer a sense of the limits of the wild–its name was an echo of the “vast and Titanic features” American naturalist Henry David Thoreau saw as demanding to be explored in order to gain perpetual refreshment in “the sight of inexhaustible vigor, vast and Titanic features”–a scenery that, Thoreau argued, included “the sea-coast with its wrecks,” as if the owners of the ship promised the ability to witness an elusive wild of “inexhaustible vigor,” but without including the wreckage of ships as among the “infinitely wild, unsurveyed, and unfathomed by us because it is unfathomable.” If we are with less exposure than ever before to a “wilderness” that is removed from man-made influence, the sinking of the ocean liner suggested the dangers of the elements–the sinking of the Titanic was a thunderbolt in global news–the renewed capital of the Titanic’s wreckage since James Cameron’s successful (and quite costly, at nearly $300 million) film recast the liner’s ruins as a tourist attraction.

Offshore Maritime Boundaries Resolved between United States and Canada for Fisheries and Continental Shelf

The threshold approached the deepest remotely controlled rescue mission or wreckage retrievals ever undertaken and challenged actual abilities to accurately track or locate. But the submersible sunk, as it happens, lay not only off the edge of territoriality, or national waters that would demand some sort of oversight, and off the continental shelf. As such, the voyage courted the edges of the imaginary of the underwater, and the promise of visiting the sunken ocean liner that was promoted in films, television shows, museums, and amusement park rides,–as well as fantasy beyond what salvagers might find, and the edges of technological capacities.

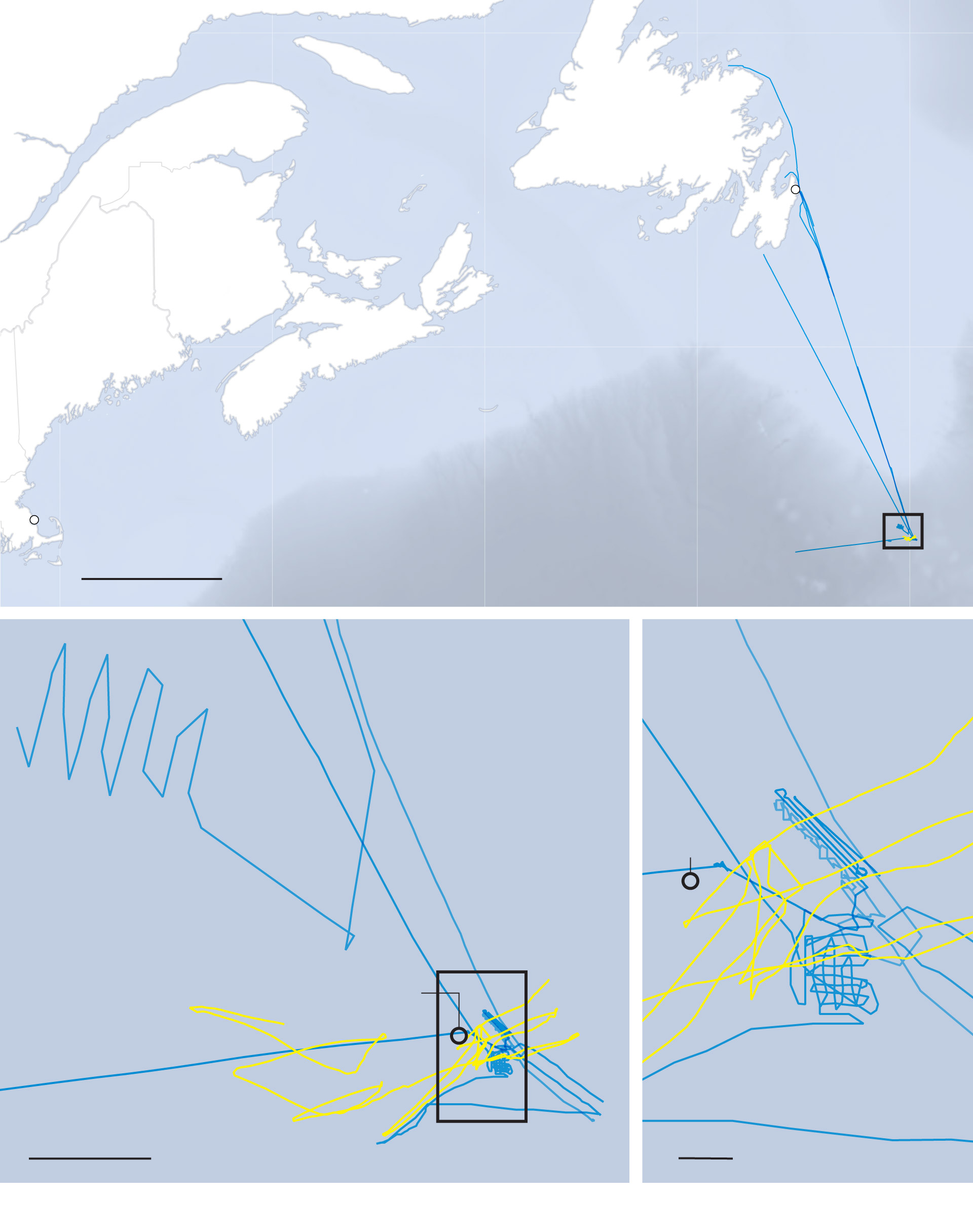

Topographic map of the 2023 Titan submersible incident,

All of which placed it on the edge of national governance, and the edge of legal liabilities, as well as at the ocean floor’s deepest depths, that lead to the terrible and terrifying disappearing act unable to be imagined in an age of mapping submarine floors, but reminds us of the lost triumphalism of the sinking of the liner in 1912, before we ever heard of global wars.

The legal regimes that govern the continental shelf and offshore areas addresss extraction, but the craft that Rush was developing to go to new abyssal depths was not purely for tourism–or luxury travel. It was rather a performance of a travel akin to proof of concept–one that seems to have staked a gamble or hopes on deep-sea prospecting, geared to underseas surveying of minerals lying in areas removed from the continental shelf–as much as it deployed the narrative of the Titanic as to attract passengers who he promised some sense of involvement with the tragedy of massive loss, in hoping to engineer a possibility of ocean floor prospecting for his own future gain. The invisible nature of the Titanic, whose wreck became the teaser and titillation for his luxury underwater trip, hoped to win massive global media attention–indeed, as a technical triumph of the recovery from the unimaginable suffering of the drowned passengers of the luxury liner, to raise hopes of creating a new market not only for underseas exploration, but locating mineral and oil deposits in deep seas.

But a map of the physical location of where the wreckage of the Titanic lies–or the wreckage of the Titan–fails to register the place of both at the intersection of the edges of liability and of fantasy. Its operator was less interested in the questions of safety standards or regulations than the loopholes of the Law of the Seas, and the legal framework that applies to ships, and teh freedom from regulations that exists outside Exclusive Economic Zones, or outside the domestic waters of national states. The “no man’s land” of underseas waters for underwater vehicles placed it in a Wild West outside international law, a setting that Stockton Rush had worked hard to cultivate and was most comfortable working. Why has to do with the ulterior motives for setting a precedent and proof of concept that could provide a showcase for investigating underwater drilling sites, more than expanding underseas tourism, but the passengers tragically caught in his ambitions never realized that–or that the owners of the ocean liner had insulated themselves from legal liability due to mid-nineteenth century maritime laws limiting liability to the post-casualty value of the vessel–even if they were shown aware of the lack of seaworthiness of the craft, removing liability for a craft that was operating in international waters even if it suffered from design flaws.

Stockton Rush, the unlicensed engineer and ambitious entrepreneur, promised paying customers a chance to view the wreck’s remaining ruin in an unprecedented voyage to abyssal depths, even as he flouted safety regulations and the constraints of international law. But the scope of his enterprise recalls that of early settlers of America, who were unable to think of their arrival in Charleston, Virginia but in entrepreneurial terms, as much as Stockton Rush took pains to dress the mission in an aura of science, inviting and adventurer and great ocean diver along of the ride-Hamish Harding and Paul-Henri Nargeolet–to increase the thrill and appeal of the underseas trip he sought to promote on a global stage. The submersible had suddenly vanished with passengers were hardly mapped with accuracy if it exploded near where the liner lay. In an era of global mapping, when the inconceivability of an absence of geolocation frustrated the world, the broad brushstrokes with which the disappeared tourist submersible sunk offshore may well have distracted from the fact that the sunken tourist submersible lay far offshore, in international waters, off the continental shelf. This was a new form of modern agency, of course, to go missing off of a global map, but began, more than has been recently or openly acknowledged, from the promise or business aim to map of offshore areas not for tourism but offshore extraction. If the tourist craft was not a global disaster, it became one–the wealthy passengers who had payed to voyage with Stockton Rush shown to be as vulnerable as refugees or intensive care victims around the world.

The lack of knowledge about its location, paradoxically if under stably inscrutable to underseas maps, in fact only increased the drama and the sense of loss, as if it was a repeat of the struggle between man and nature. There was an urgency with which we hoped that signs of life might be discovered with a weird urgency, even as one felt anger at the risks that the passengers had agreed to submit as they had released the firm that the cocky cowboy-like Stockton Rush ran from all legal liability. The drama of the location of the lost vessel that had hubristically gone searching for the wreck that lay at the bottom of the sea turned a pleasure trip promising to “see” the ruins of the sunken Titanic sent a range of deep sea vessels searching for the missing submersible, in hopes to locate the vessel that lay closest to Newfoundland, per the MarineTraffic and the U.S. Coast Guard.

If the five fatalities are but a fraction of the 1517 passengers and crew lost in the sinking of the Titanic, the submersible that Rush boasted would offer the opportunity to see “at first hand” the ruins that had been featured in the set of the recent IMAX film as well as the award-winning romance directed by James Cameron, and featured in Walt Disney World, meeting an expanding desire for underseas tourism that has whitewashed the actual enterprise which Rusch pioneered.

As we learn more and more about Rush’s marketing of dream voyages to visit the Titanic from 2022, amidst the ink spilled over a global tragedy that snared an international cast of unfortunates–a Pakistani billionaire and son duo celebrating Father’s Day on the doomed dive; a French marine scientist; a British adventurer tycoon who had previously blasted into space–their tragedy, driven by the hopes of glimpsing at first hand the lost ship conjured in a multimillion-dollar film, it is clear the basic map for the journey on which he piloted the experimental craft was that of international waters–an area “offshore,” beyond the lines of national jurisdiction–pushed levels of risk that one should ever be allowed to take passengers to set new thresholds in evading legal responsibility. The risks were, in a master-stroke of sorts, evaded by Rush’s own absorption in the global enthrallment of the Titanic disaster that had made the viewing of its wreckage into “a must-do dive” in an utterly “unknown environment” was a trip that would only be possible with no regulatory oversight.

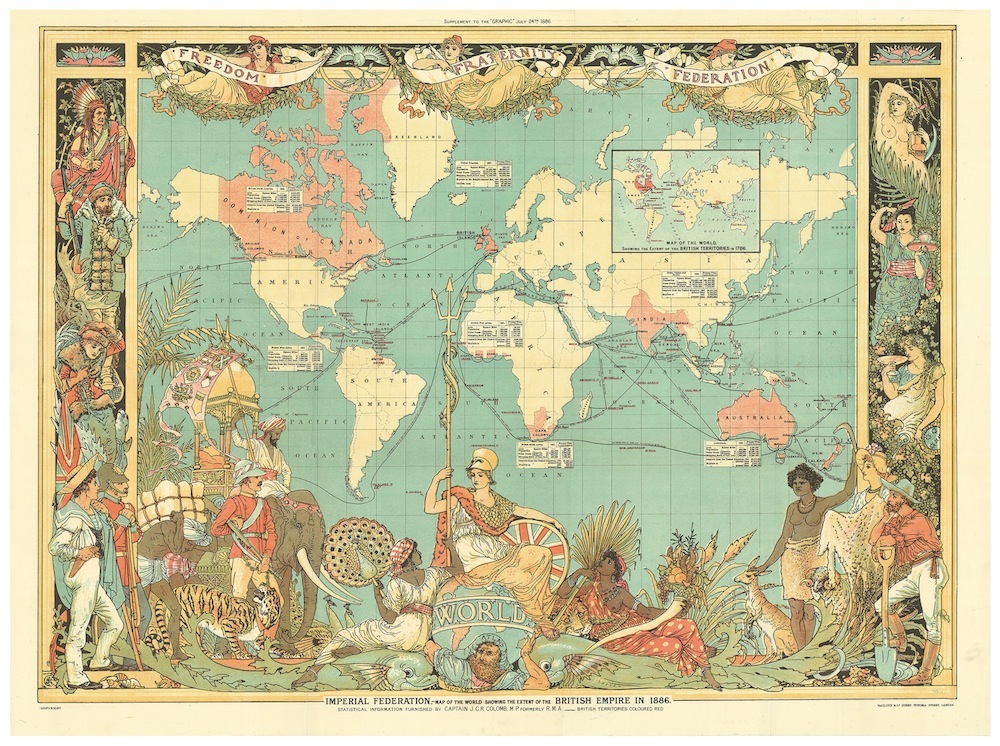

The experimental nature of the “mission”–an attempt to invest it with high-minded associations–remained as opaque as the location of the ruins of the Titanic on an underwater volcanic reef. Yet if the first time was a tragedy of global consequence, the tragedy of recent months is something more than tragic, inflected as it is with the tragic shadow of events of earlier matters global consequence it seemed destined to emulate, even if it hoped to redeem. The similarity in the rapidity with which the search and tragic loss was mediated in global media to the global scale of a tragedy, just before the huger tragedies of global wars, is hinted at in the global consciousness of shipwrecks that James Joyce imagined in the 1920s as set in Dublin barroom in a work emblematic of modernity. If the Ulysses is a novel akin to the ocean, in which the reader sails among its strands, and waters, often watching floating flotsam and jetsam amidst the “writhing weeds lift[ing] languidly and swaying arms” in an upwelling tide, “in whispering waters swaying and upturning coy silver fronds,” the story of the Titanic seems to make an appearance unexpected in a dialogues ostensibly set in 1905. Sailors gathered offshore at the coffee house “fell to woolgathering on the enormous dimensions of the water about the globe” as “a casual glance at the map revealed it covered fully three fourths of [the world] fully realized what it meant to rule the waves” by a notion of distributed sovereignty, a question that was embodied in the imaging of imperial subjects at the base of a map that was mostly light blue.

Imperial Federation: Map Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886/The Graphic, 24 July 1886

A sailor paused his woolgathering before Walter Cranes’ 1886 lithograph of Imperial Federation of the British Empire’s possessions in pink, pondering in Ireland’s capital the promotional map sold and created for the Indian and Colonial Exhibition of 1886. If the Dublin group would have been well aware of how the map whitewashed the violence of colonization in the Dublin saloon, centered on England but posing the problem of global peoples divided by seas paying tribute to England, the colorful keepsake immediately provoked rather grim conversation among the sailors, who seem to discuss, implicitly rather than explicitly, the marine accidents and disasters that occurred offshore in the map centered on Greenwich and Greenwich Mean Time, promising to give pictorial coherence of the freedom and fraternity the mighty be found in imperial federation. If the British Empire might well have been a sticking point of criticism in Dublin saloons, the attention turned to maritime disaster among this marooned lot, as the pair of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus join them in pondering the errant routes that occur along the very same smooth oceanic expanse.

Joyce imagined the discussion turned from “what it meant, to rule the waves” posed by the occasional map, a newspaper insert of propaganda more than statement of sovereignty, meant to celebrate linking far-flung British territories by the arcing lines of maritime routes, measuring their smooth arcs against their own experience in this episode set in the sprawling oceanic expanse of the novel. If Ulysses is a man of many travels, and Dedalus is caught in a labyrinth of Dublin’s streets as well as one that is a labyrinth of the psyche as much as urban geography, as discussion about actual oceans, as much as what it means for an artist to be free of England’s colonial rule, or to leave England in pursuit of one’s art, the sailors discuss the dangers of stormy weather, “others [turn] to talking about accidents at sea, ships lost in a fog, collisions with icebergs, all that sort of thing“–as if risks of collisions with icebergs were a consequence of the hubris of imperial claims to link the seas in “the British family of nations” in ways that ignored intervening oceans. “‘I’m tired of all those rocks in the sea,'” said the “soi-disant sailor,” a sort of surrogate for Odysseus, tired by his travels as the “much-turned man” or “man of many travels”– πολύτροπον, or polytropon, difficult to translate but the first adjective to describe Odysseus, tired before the map of nautical expanse, despite his nautical skill and resourcefulness in navigating its expanse.

IN the cabman’s shelter, discussion turned from mastery of the seas to events of poignant tragedy. From expressing “gratitude also to the harbourmasters and coastguard service who had to man the rigging and push off and out amid the elements whatever the season,” and often “experienced some remarkably choppy, not to say stormy, weather from “woolgathering on the enormous dimensions of water about the globe” discussion turned or rather hit and collided with the question of icebergs, as the Titanic would later indeed hit, amidst the memory of a”superannuated old salt, evidently derelict, seated habitually near the not particularly redolent sea on the wall.” From Sinbad the sailor, and the “splendid proportion of hips, bosom” in antique statues, conversation turned “to talking about accidents at sea, ships lost in a fog, collisions with icebergs, all that sort of thing” [26372-26373], haunting even one who had “doubled the Cape a few times, weathered a monsoon, and navigated the China seas–disrupt the smooth links of British imperial possessions, perhaps haunted by the accidents encountered in historical voyages of Ulysses. Even if classicists declared it was a vain challenge to “engage in the vain attempt to construct eh voyage of Odyssesus upon the actual distribution of the earth’s surface,” the voyage was mapped, even if W.E. Gladstone had his doubts as to its value, rather compulsively by Renaissance humanists, as the voyage of Ulysses became something of a cartographic Holy Grail of mapping the perilous travels around the Mediterranean.

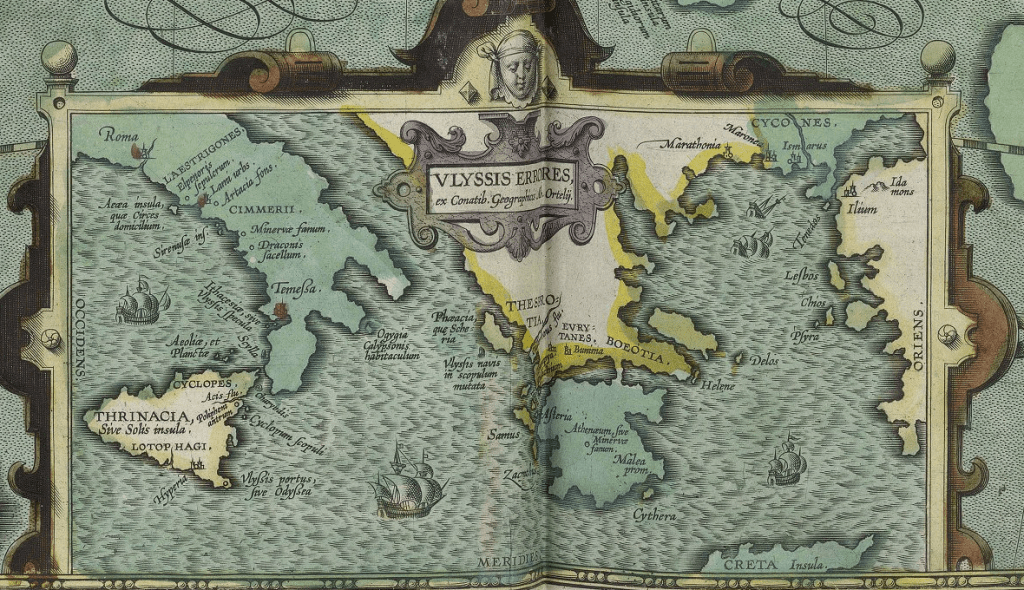

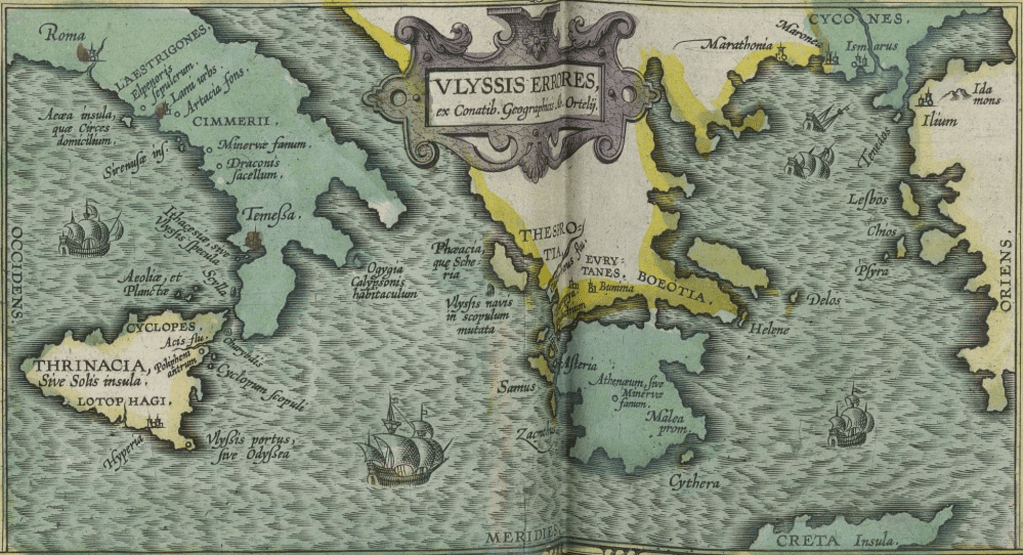

Abraham Ortelius, Map of the Peregrination of Ulyssses [Ulyssis Errores] (1610), Wikimedia

Abraham Ortelius, Peregrinations of Ulysses/Folger Shakespeare Library via Wikimedia Commons

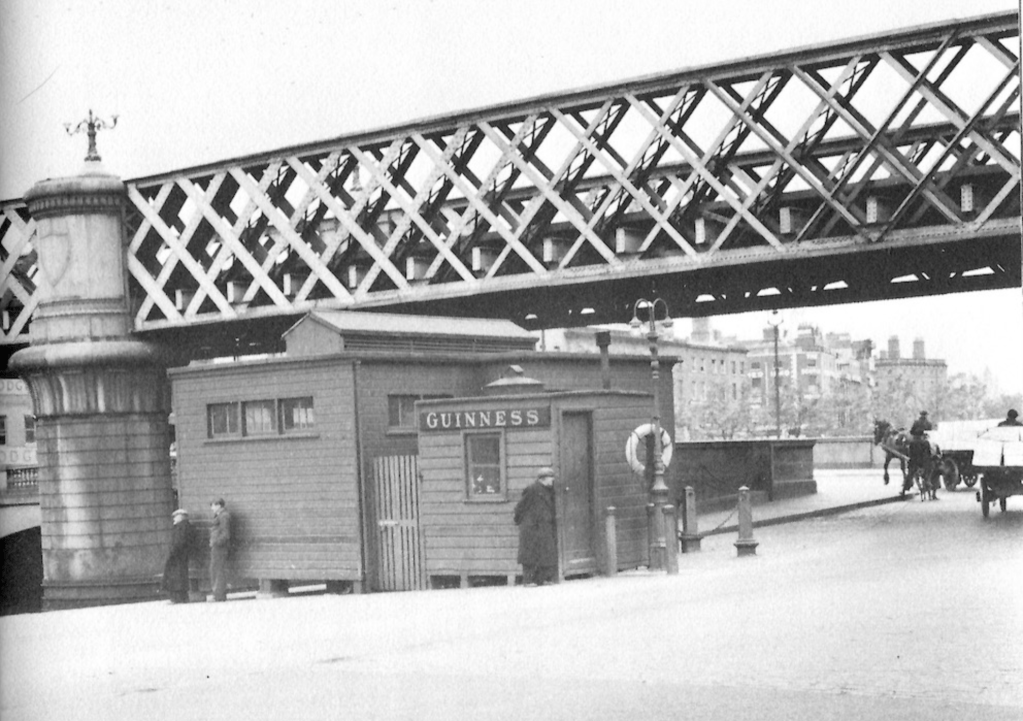

Joyce may have known that Abraham Ortelius mapped a periplus of Ulysses’ peregrinations that had converted the mythic travel that Joyce adopted to divide his novel’s itinerary around Dublin or not, from his men’s encounter with Circe, on Aeaea, where he stay a year, to his return to Ithaca, in a colorful cartographical vignette or not, by 1920s the map of ocean dangers expanded to icebergs. For sailors drinking beer or harboring a coffee in the a Cabman’s Shelter by the River Liffey in 1905, icebergs were already a pressing reality, among other modern maritime disasters: if one cannot easily accuse Joyce of hucksterism, the haunting iceberg that sunk the Titanic as Joyce was writing in Trieste sent a shadow that fell across discussion at the Cabman’s Shelter by the customs house. Joyce was referencing how the Ancient Mariner met roaring winds when “came both mist and snow,/ . . . And ice, mast-high, came floating by,/As green as emerald,” and “ice was all between;” the Ancient Mariner witnessed “the Albatross . . . followeth the ship as it returned northward through fog and floating ice“–but the stories told in the Cabman’s Shelter gained portentousness after the Titanic disaster, the ocean liner disaster was hard not to imagine in the dialogue imagined to turn to icebergs in the “unpretentious” shelter beneath a bridge in Dublin as it had become a modern global myth.

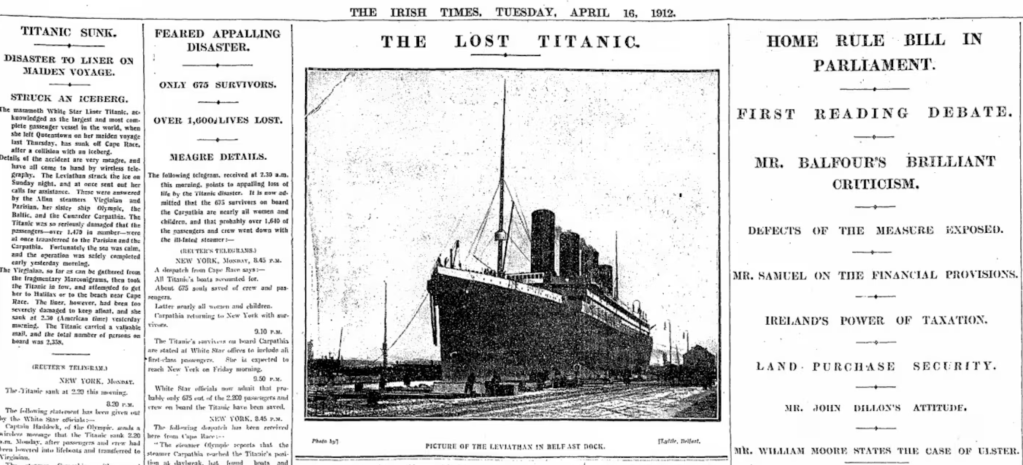

For it inevitably cast an impossibly long shadow even on the disappearance of the Titan in 2023. (The self-styled “adventurer who died near The Titanic’s rusting wreckage–had indeed married the great-granddaughter of Isidore and Ida Straus, among the most illustrious wealthy passengers on the Titanic when it crashed into an iceberg and sunk within three hours.). The image of the collision of the ship that stood for marine dominance on its maiden voyage seems to have haunted Joyce, in some way, as the discussion of Ulysses is haunted by the Theseus paradox of the identity of a ship whose parts are gradually replaced on its voyage. If all ships attempt to brave the seas, or tackle untamed wilds and marine beasts, the thought experiment obsesses Stephen Dedalus, to whom it might have seemed only natural discussion in the Cabman’s Shelter turned to the wrecks off the coast of Ireland, presumably of those who tried to leave the island. For the arrival of the iceberg in the discussion at the Cabman’s Shelter would have served to back-shadow global discussion of the tragedy of The Titanic, sunk by iceberg in 1912, no doubt, even in the book that was serialized from March, 1918, when the widely reported disaster was relayed in print in black and white sent the Anglo-American elite–John Jacob Astor IV; W.T. Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette and founder of the modern tabloid, a Rupert Murdoch of his time; magnate Isidore Strauss and his wife Ida–to the seas, a hundred and ten Irish fatalities among the second class seats.

The ocean liner’s tragedy was announced in Ireland, appearing in daily newspapers framed between issues of Home Rule as “an appalling disaster” that was very local as well as global: “the lost Titanic” included eleven from County Mayo, onboarded in County Cork, and six from Belfast traveling to Spokane in the state of Washington to start new lives in America–and five other Irish lives had been lost in its construction in Belfast. Joyce was inevitably attracted by the topic in discussions with sailors at the Mediterranean port city Trieste, whose company he sought out so soon after arriving with his twenty year old Nora Barnacle in October, 1904, to leave her at the train station as he sought out housing. The Mediterranean port he began Ulysses was where he probably heard boasts of sailors traveling the world’s seas he transposed to the sailors in Italian in Dublin–but he would have been haunted by the “Lost Titanic” prominently bemoaned in the Irish Times. But the global scale of the catastrophe offered a new mythology that provided the modern bookend to the Odyssean perilous that the eighteen chapters or episodes of the novel he wrote spanned.

The maritime disaster was “an extreme tragedy” that newspapers register with incredulity as they went going to press, more obscene as it occurred to a ship”apportioned throughout in a way no modern hotel on solid earth could hope to rival.” The surreal combination of luxury and mortality and wealth and human frailty was something Joyce cleverly back-shadowed, and how could he not? The 1912 disaster fit his novel of fates of modern identity in an impending dissolution of borders. The novel written 1914-21 by an itinerant Irishman written in Paris, Zürich and Trieste fit the scale of his capacious pondering of the global events of travel. For the new mythologies stretched in the novel composed by an itinerant Irishman i1914-21 could not avoid the tragedy of The Titanic, also a pall across the dark side of modernity, in a work he let the world know was written as he traveled far from Dublin to Trieste, Zürich and Paris.

Discussion of menacing icebergs in the shelter near the customs house by the Liffey River may well also refer to the tragic sinking of an Irish vessel that occurred but days previous to the sinking of the Titanic–if not also allude to the figure of icebergs that had romantic allure of Coleridge’s Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner. Joyce’s attraction to the Titanic was not humanitarian. If the linter was built in Belfast, the terror of icebergs met the poetic powers of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, that excavator of the dreamed unconscious, who evoked in Rime of the Ancient Mariner, that other heroic ocean-goer, “ice, mast-high, came floating by.” The iceberg is a ghostly apparition, a spectral vision of a “land of ice . . . where no living thing was to be seen” as “the ice was here, the ice was there,/The ice was all around;/It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,/Like noises in a swound!” The dream-like ocean which “through the drifts/the snowy cliffs/Did send a dismal sheen” was both mystical and ecstatic, and present in the iconography of multiple engravings that haunted Victorian visual culture; Gustave Doré illustrated it as a descent to a unreal world in which the albatross is a sole redemptive guide “to contemplate in the mind, as in a picture, the image of a grander and better world, . . . keeping a sense of proportion so we can tell what is certain from what is uncertain and day from night.”

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Captioned “The Ice Was All Around”

What did it mean to be lost at sea? Among the specters of historic shipwrecks ancient and modern Joyce sprinkled in the episode of Ulysses he had called “Eumaeus,” the iceberg is a powerful back-mirroring of dangers fit a novel that paralleled Odysseus’ return to Ithaca. Among the stories of sea voyages told on land, the prominence of icebergs had grown since the disastrous sinking of The Titanic, if the topic may be decidedly out of step with discussions dated April 15, 1904, decades before the ocean liner actually sunk. Joyce drew from a stash of newspapers he hoarded from his cross-channel return trips back to Dublin from April 15, 1904, date of his first sexual relations with Nora Barnacle, hoarding these newspaper headlines, the headlines of the global disaster of The Titanic that entered the sailors’ discussions indirectly in the Coffee-House is a specter of modernity.