With frozen glaciers disappearing into the oceans at an unprecedented rate, the rise of an ecotourism of glacier viewing is hardly unexpected. The new heights of glacial melt that are feared for much of the arctic this summer–even if the disappearance of sea-ice predicted by late summer won’t be radically different or worse from previous years–suggest cause for environmental alarm as monumental as the burning of dry forests that spew smoke across the nation. The arctic sublime is, perhaps, more deeply rooted in our imagination, as the fascination of the edges and margins of the arctic as a timeless region and place. The contraction of those margins by melting glaciers suggests that our notion of acclimating to a wandering pole seems more time-stamped, in the mode of current maps, than timeless, a warping as well as a melting of time and space.

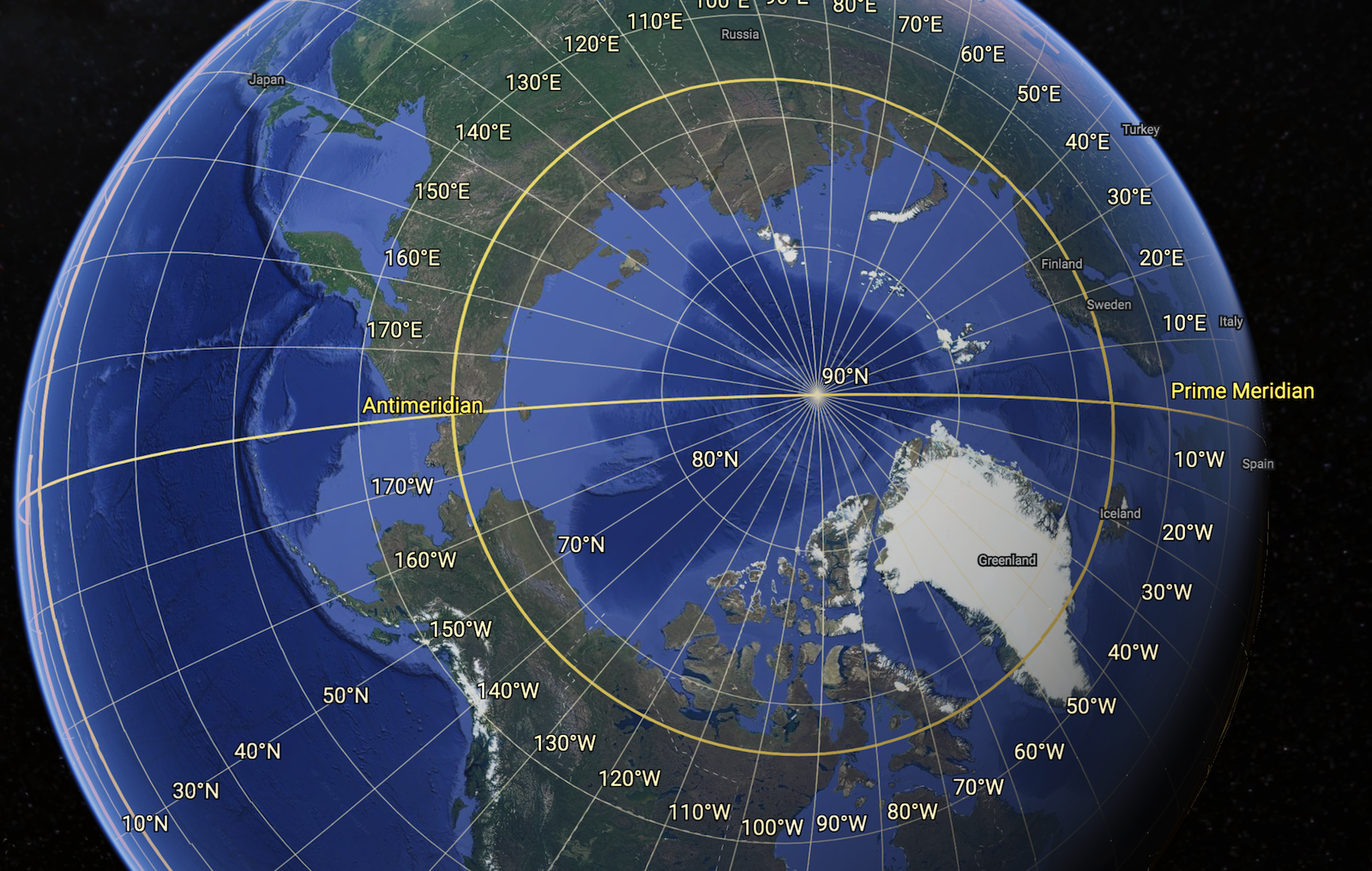

The disappearing glaciers map conflicts between two logics–a globalized world of smooth surfaces of the Anthropocene, and image of a timeless arctic wild, whose purity is frozen and lies preserved just beyond our reach. The blurred boundary of the Arctic Sea is a consequence of the blurring of boundaries wrought by globalization: warming temperatures that have been created by escalating emissions of carbon and other greenhouse gasses are creating an age of global melting–and glacial melting–where icebergs are fewer and harder to see, and the sea-ice in the former Arctic Ocean is far less likely to strand ships. The erosion of an edge of the Arctic circle, already nudged north at a rate of just under fifteen meters a year beyond 66.6° N, is mapped in anticipation of arctic melting, a surface of pristine blue bound by a line–despite questions of the margins of thawing permafrost, meltwater flow, ice-thinning or of sea-ice. Drawing a clear line for the Arctic Circle is the vestigial inheritance of print cartography, whose conceptual authority hinders us from mapping the critical margins in which glacial meltwater moves into the northern oceans and warming northern seas.

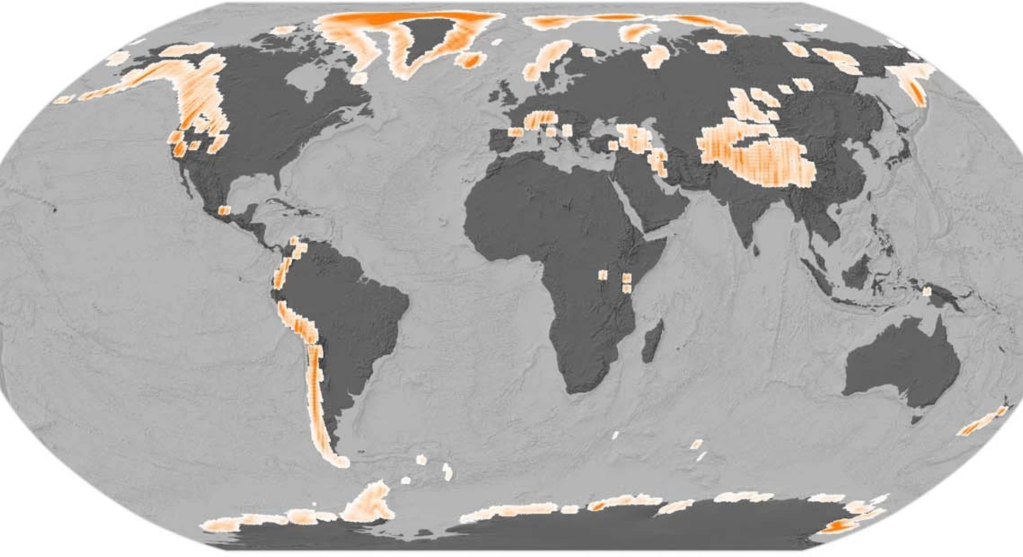

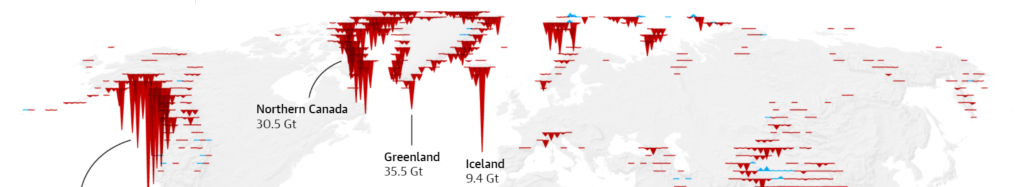

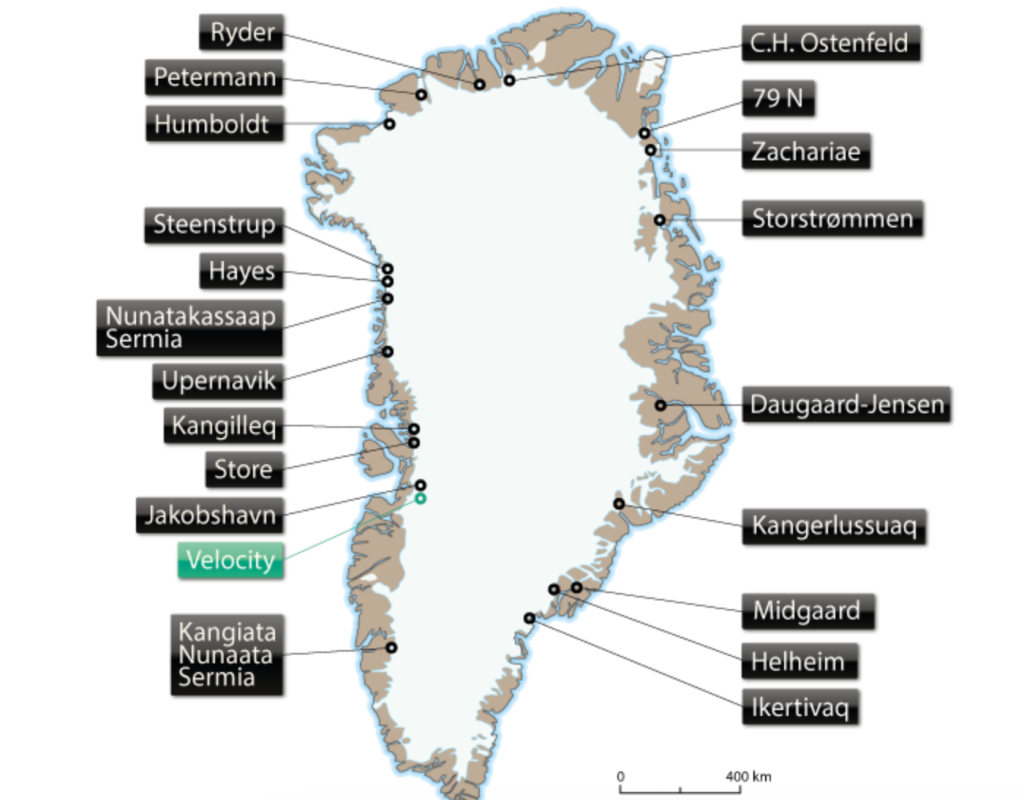

The shrinking mass of the patchwork of glaciers, mapped in part by satellite, reveal rates of disintegration more rapid rates than the ice-sheet of Greenland, in the new millennium, marked by accelerated reduction of mass, of hydrologic consequences that demand local observation. After twenty-five consecutive years of sea-ice los, late season warming created melt conditions for over a third of Greenland’s ice sheet, revealing the new face of global warming of spreading icemelt–as well as surface melt on 36% of the ice-sheet, surface melt at its highest altitudes were fed by surface air temperatures the sixth warmest since 1900. After sustained sense of limited loss of glacial mass in previous decades, among small glaciers over three decades 1961-90, even given the difficulties of accurately mapping time-series for glacier mass before satellite observations, increase loss of ice mass set off alarms. The far lower mass lost by glaciers sharply contrasts to current levels of ice-melt and widespread glacier loss, here alarmingly noted by a cautionary color ramp of orange-red.

Accelerated Global Glacier Mass Loss in the Early Twenty-First Century/Hugonnet, in Nature (2021)

To be sure, the increased interest in preserving a recording of the arctic’s vital signs–the changing soundscape of ice crackling under ships, and glacial waterflow, seek to register the vitality of the glacial landscape to bring the arctic regions to greater prominence, relating to the new scale of anthropogenic disturbance able to be sensed by their own “vital signs”: the Arctic Report Card issued annually by the U.S. National Oceanic and Aeronautic Administration since 2006 offers a rich database virtually accessible of the disturbances of the global arctic,–although the report of 2018 predicted the entrance of the arctic into “uncharted territory” as a lead research scientist of NOAA warned, with an irony firmly based on new data of surface-air temperatures, sea ice decline, wildlife mortality to erosion to ice-melt that had previously long been difficult to access. If we feel the weird weather systems as a local deviation, more than a consequence of arctic melting, they may remind us how rooted our sense of place is in the frozen remoteness of the upper north, whose icepack reflects more than absorbs solar temperatures–as melting stands to end the idea of a frozen timeless purity, as the survival of sea ice more than a few years precipitously declined, even if some fraction of the Arctic Ocean seem to still remain frozen year-round.

How can we chart these uncharted territories in maps, or can we develop the tools for a conjectural cartography as sufficiently orienting even while we face the prospect of a migration of due north–a change as radically unsteadying for mappers as removing the carpet from beneath our feet? The long-term movement of magnetic North toward Siberian islands is indeed on an uncertain course–

–shifting from Thoreau’s time to the Siberian shores, making us rethink arctic margins, and indeed the stability we were long accustomed to associate with magnetic north, a motion partly tied to melting, and which makes us take stock of glacial health, whose vitality has less to do with warmth.

Conceptual artists as Julian Charrière, whose Swiss origins have perhaps left him particularly sensitive to Alpine landscapes and glaciers, have made it an artistic mission to preserve the fragility of ice fields, sea ice, and underseas sounds of the new Arctic, offering a sense-based record of melting in images able to act as repositories of a new visual relation to a fast-melting world in collaboration with scientific explorers of the reduced levels of sea ice and growing glacial melt.

Julien Charrière, Towards No Earthly Pole, 2019 in Erratic (SFMOMA)

The arctic landscape is also made more alive by the sounds of arctic landscapes, all too easily black-boxed from our world in a denial of climate change. The sounds of glacial calving that are so resonant with the catastrophic consequences of polar glacial collapse offer a sonic register of a collapsing arctic world; the multiplication of YouTube videos of glacial calving seem a yearning to make more concrete the awesome spectacle of glacial collapse. Attempts to extract ice cores from glaciers to preserve the evidence of climactic history before it melts has also inspired attempts to record the interior sounds of glacial vitality in sound recordings of the snapping, crackling, and crevassing as evidence of glacial vitality not from the margins but center of the arctic landscape that remains–somewhat akin to how bioacousticians recorded Humpback Whales circa 1970 to preserve vocalizations as ecological affirmations of balene humanism, revealing sonic expressive sequencing and improvisation never before heard by an innovative “hydrophone” in a nature recording so famous to grow consciousness for a global moratorium on whale hunting.

But if the perception of the aesthetic beauty of whale calls were background music for mindfulness, the melting margins of the Arctic are rarely mapped they demand–or mapped at all, as they are so reduced.

Global warming stands to erase the arctic as an extreme frontier, and to change the flow of sea temperatures in ways that will dramatically accelerate sea-level rise. The archetypal romantic Arctic explorer, Robert Walton, marveled at the “beauty and delight” of desolate frozen fields, even as his blood froze in his veins on the Greenland whaling ship he commandeered to reach the North Pole. , marveled at its “beauty and delight.”

Only as Walton’s whaling ship is trapped by floating ice and cannot move did his arctic reveries conclude; before the ice breaks and frees the ship, he spied Victor Frankenstein, the sled on which he pursued the monster who had perhaps duped Frankenstein to follow him to the North Pole, impervious to temperatures his creator could not survive. The novel inspired by ghost stories may invite us to track the monster from a ship that lay at the edges of sea-ice in the Arctic Ocean–

Walton’s Course and the Edge of Average Arctic Ice Edge from March through August in Nordic Sea/ ACSYS Historical Ice Chart Archive, Boulder CO, Frankenstein Atlas by Jason M Kelly

–she was informed by the frustration of numerous polar voyages sponsored by the British Admiralty to the North Pole that were stopped by ice sheets and icebergs beyond the Barents Sea. Mary Shelley seems to have mapped a desolate arctic landscape to conclude Frankenstein’s search for forbidden knowledge, perhaps as she revised the manuscript with grading contributions from Percy in England, and access to the records of the Admiralty. The arctic setting became the fatal conclusion for the “Modern Prometheus,” before the backstory of Frankenstein raising ghosts by alchemical incantations send him to fuse Paracelsianism and natural science that would long haunt histories of science. The very setting of Alpine glaciers where Shelley conceived the story found their conclusion in the arctic, both haunted by accelerated glacier loss. The register of glacial melt is a current register of the Anthropocene, whose own Promethean character is only just beginning to be understood. The northern arctic margins where Frankenstein and Walton crossed paths was still continued to be charted through the mid-nineteenth century, the Polar Sea resistant to staking territorial claims as solid land, the sea-ice unable to be mapped within northern polar seas–

British Admiralty Chart of North Polar Sea (1855, rev 1874) noting Coasts British Explorers Discovered pre-1800 (Dark Blue) and post-1800 (Brown); noting coasts explored by Americans, Germans, Swedes and Austrians 1859-74 in Red Ink

–in ways that we are currently coming to terms with as a mapping of ice-melt and sea-ice melting, in a horror story of its own that has transcended territorial claims.

The current landscape of arctic melting frustrates bounding the arctic by a simple line. Rather, we are challenged to map the rates of glacial retreat and the melting of ice sheets, that stand to erode the sense of the Arctic as a fixed frontier, whose margins are remapped as remote sensing provides data of the increasing rates of melting. While icy breezes refreshed Walton’s senses as he passed to the Arctic, if not overwhelming him with the vision of filling long-nurtured hopes of sea-faring at the edges of a geographic extremity, we lack map signs adequate to register fears of polar melting in our warming world. Niko Kommenda’s 2021 visualization in the header to this post of the increased rates at which global glaciers melt bravely tries to sound the alarm. The schematic projection captures the terror of the impending glacial melting, a flattening of the polar surfaces of the globe, where trans-arctic commercial pathways are finally being imagined and plotted, two hundred years after seeking in vain for a northwest passage across Arctic Seas.

By 2016, as the ice had already retreated from the pole, nine hundred passengers had signed up for spots on a luxury cruise liner, the Crystal Serenity, to sail through the sudden access that low sea ice offered to the lost geographic imaginary of the Northwest Passage, a sea route around the top of North America that had become open to commercial ships, and has since become a route of commercial yachting, if it was only first crossed in 1906 if attempted long earlier. While once passing some 36,000 ice-bound islands, some seven routes have opened for ships today, and innumerable routes by yacht, stopping at the site of the unfortunate 18445 Franklin expedition and recent polar catastrophes,

Jason van Bruggen/Boat Iternational

as well as some pretty spectacular vies of calving glaciers, but demand constant navigation of the shifting sea-ice and floating glaciers by yachtsmen, and super yachts able to cross sea ice who often retrace the popular “Amundsen route” first made in 1906, when sea-ice retreat allows navigation.

Entry to the Northwest Passage in 2022/Jason van Bruggen

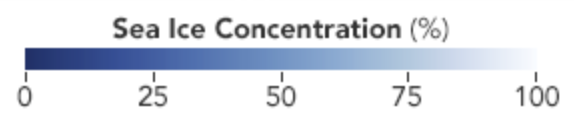

As we anticipate the ice-free arctic, we will brace for a shifting global axis, potentially upsetting our mapping tools, and a rapid rise in global sea-level, if the melting rate of sea ice proceeds at currently revised rates. As the shifts in global mass distribution due to the melting of glaciers and polar ice-sheet seem to have progressed to throw earth off its axis, we are increasingly disoriented not only by raging fires, or torrential rain, but by ice-melt–the sea ice of the arctic is predicted to melt by the summer of 2030, polar archipelagos melting two decades earlier than once projected, when 2050 was projected as a watershed for an ice-free Arctic Ocean, even in low-emissions scenarios. (Observed sea-ice area in the arctic dramatically plunged 1980-2020, but even in the face of such authoritative models, it is difficult to imagine the disappearing act to conclude.)

Although global mapping companies are beset with worries at the possibilities of a wandering and irregularly migrating or wobbly north pole, as extreme melting has sent the arctic regions and magnetic north into uncharted waters, we rightly worry we are headed not only into an era of submerged landscapes, but unstable relation to old orienting points. The “post-glacier” era not only has started to shift stability of the earth’s axis, on account of the readjustment of mass melting of the polar ice-sheet and global glaciers have already caused in the new millennium, but may well be tilting our bearings and sense of being in the world. The unsteady migration of the North Pole in the new millennium is a deep unsteadying, warping our sense of mapping and being in the world, whose strange behavior has accelerated since the nineteenth century in unsteadying ways, moving from Canada toward Russia in a weird consequence of globalized economies that may be accelerating its motion and force necessary geodetic adjustments to our GPS. If the geodetic maps that Henry David Thoreau devised for Walden Pond were seen by some readers as a comic send-up of the mapping of national waters of the U.S. Coastal Survey, magnetic north offered a framework for transcendentalism for Thoreau to map Walden Pond and the adjacent lake country,–tangible and quantitative even if it diverged from the compass, an accurate frame of reference for surveying and an ethical framework and way of life to liberated from social constraints, a firm foundation to a imagine a more ethical world, firmer than the sailors who vainly sought to arrive at the polar cap.

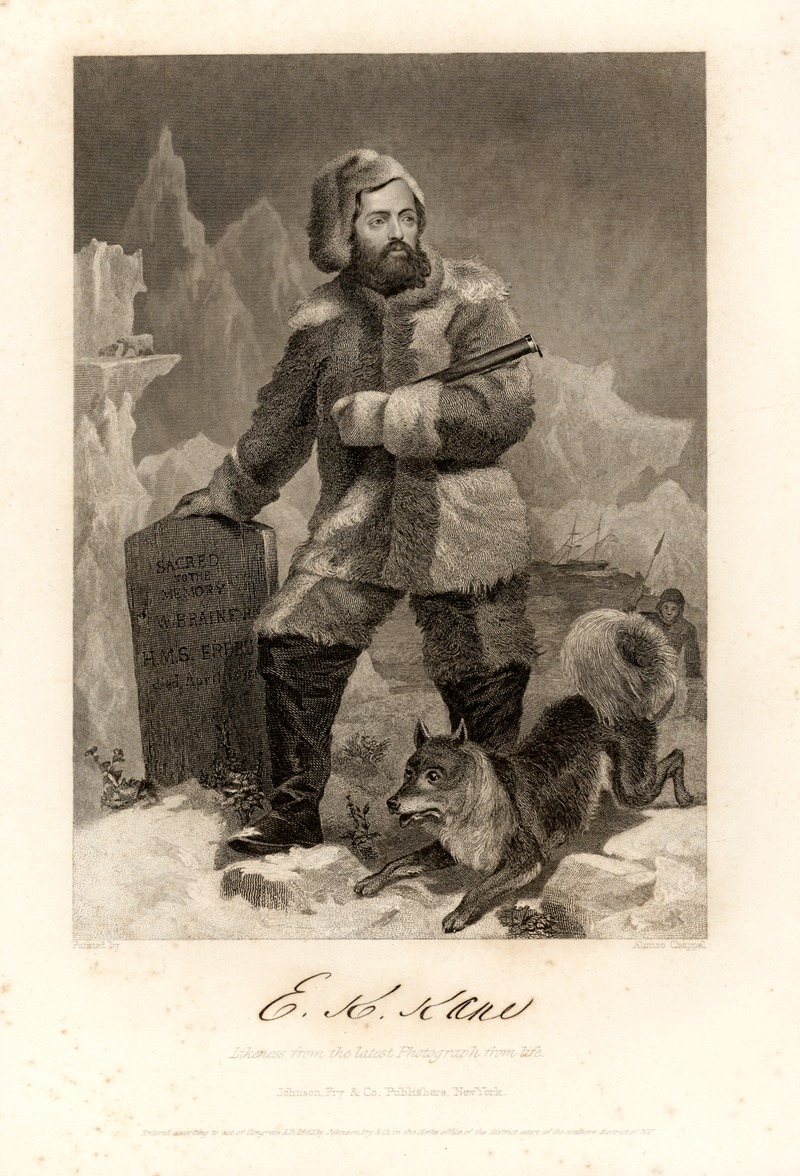

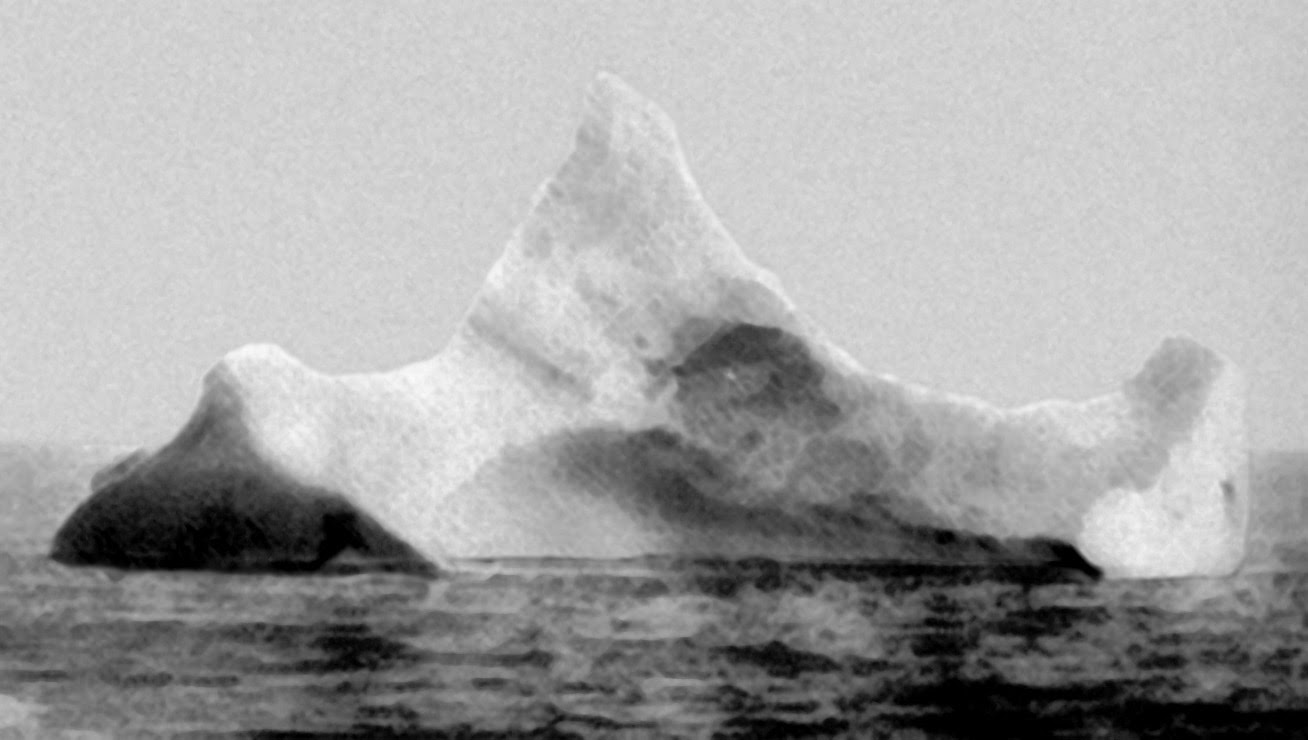

4. The nineteenth-century American explorer Elisha Kent Kane’s accounts of arctic icebergs that had trapped the search vessel on which he was surgeon soon became a media sensation of sorts in the mid-nineteenth century. Indicating the global lines of the arctic that Kane courted vicariously for his audiences in newspaper articles, public speeches, and indeed the watercolors and drawings he displayed on the lecture circuit and Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society, of which his father served as secretary from 1828-48, seems to have engaged the nation’s attention to the arctic in ways that appear destined to parallel the upcoming attention to the glacial retreat by which the quite sudden melting of long-frozen polar ice merits action in an age of global warming. Despite a growth of climate expertise, we are painfully without guides to the disappearance of glacial markers and glacial melt that has already changed the axis on which the earth spins.

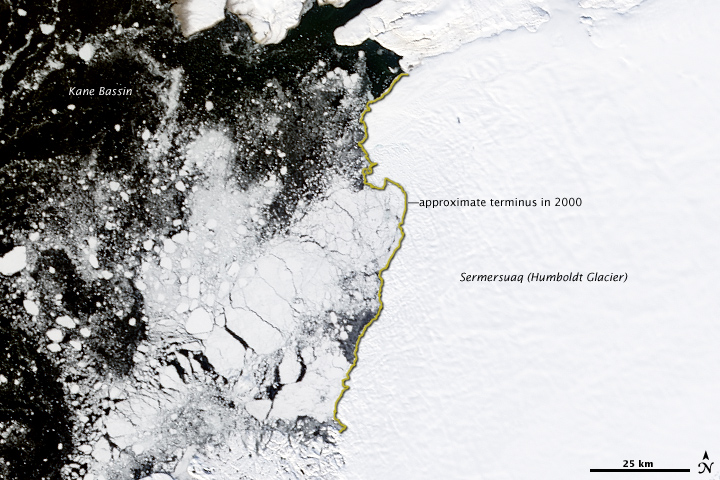

It is disturbing to find a landscape once seen as timeless to be mapped as time-stamped. Can the awe of the arctic landscape still hold awe? Elisha Kent Kane’s audacious account of first-hand contact with the Humboldt Glacier–now the Sermersuaq Glacier–off of Greenland, while now forgotten, was so vivid Henry David Thoreau even felt jealousy, as he doubted polar explorers like Grinell, for all their public celebration, had ever needed to travel to Greenland’s coast. (Thoreau echoed Ralph Waldo Emerson’s doubts in “Self-Reliance” about the value of currents fad for travel abroad, calling the rage for visiting Rome or Greece less a real destination than “a fool’s paradise” that follows from neglect of one’s own backyard: “the soul is no traveller, the wise man stays home;” the rage for ravel as an amusement only leads only to travel away from one’s true self.) The conflict or the terrain for conflict had perhaps been mapped: among the personal papers of the doctor served as senior medical officer in a polar expedition, Bones McCoy to Grinnell’s more elegant Capt. Kirk, except that Kane was chosen to head the attempted polar expedition that followed recent maps of the open polar sea, imagining they might find a northwest passage, before they were trapped by sea ice, and forced to abandon their ship for a long trek south, subsisting in the wild on walruses and having dressed in animal skins amidst the frozen landscape of towering icy peak.

The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin: A Personal Narrative (1853)

Kent Kane had fronted the wild as a scientist-explorer published in a personal narrative of 1853, a year before Thoreau’s condensed narrative of the twenty-six months spent at Walden Pond, based on lectures that had made good on many newspaper accounts he had filed while at sea. In his escape narrative of the arctic, the surgeon rejected scientific jargon to evoke the terror of arctic landscapes of an uninhabited wild. He rendered its uncanny spectacle by watercolors to capture his fronting of the uncanny unknown arctic wilds that escaped the impoverished dimensions even of architectural panorama, placing adiences in a harrowing story barely avoiding shipwreck on massive icebergs that threatened the vessel in arctic seas where the compass itself froze as a romance of confronting the nature of a frozen north, as if the snowy lands were uninhabited, as a Robinson Crusoe of the northern hemisphere, in a melodrama against magnified elements.

Ship Wrecked on an iceberg, from Elisha Kent Kane, Arctic Explorations in the Years 1853, 1854, 1855

Emerson’s maxim about the vanity of travel is often cited proverbially, perhaps imbued with new tones in an age of globalization, apart from the Sage of Concord proviso about the pleasures of solitude that “Our minds travel when our bodies are forced to stay at home.” The range of remote observation that we are able to access about the arctic this warming summer–and warming summers previous–are cause for alarm, as the number of glaciers have declined rather precipitously in recent decades, as the oceans have warmed, and their melting across the northern hemisphere have contributed and stand to contribute more to the rising of sea-level, as well as exhausting one of the largest storehouses of freshwater in frozen form.

Whether or not the heroes of arctic exploration never fully explored their own back yards with due diligence or not, Thoreau framed a prospective from Walden on the world, as he cultivated his perceptual abilities–refining his own study of the local landscape and its morphological characteristics. To be sure, Thoreau appreciated his own backyard as a source of rich meditation informed by his avid reading of Darwin’s discussion of Patagonia, Rev. William Gilpin’s accounts of the depth of Scottish coasts and Lochs, as well as Kane’s spectacular accounts of his approach of Greenland’s glacier, to view icebergs calving from its coast at first hand. The edge of Walden Pond emerged something of a standard by which he was to judge them all, and for each natural history text (from Lyellian geography to historical bird migrations pioneered by Gilbert Whyte’s Selbourne) to measure Walden Pond against. They offered a basis for Thoreau’s mind to travel, while he was rooted on the banks of Walden Pond, and even to imagine, the actual engineering of Walden Pond and the ponds of Sudbury Plain as excavated by glacial retreat, long before the “Hyperborean” workmen (Irish day laborers) came to export its precious if undervalued ice for a global market.

Kane’s sensational voyages to the arctic had made him an American hero, against whose narrative of an arctic picturesque narrative or so, Thoreau might well have sought to define himself against, but in the past sixty years, Thoreau has remained the model of local observation. Recently, as one tries to process the extent of global warming, remote sensing gives some strength to Thoreau’s point–and Emerson’s–given the possibility of considering the world from one place, without braving the elements to risk being trapped by sea-ice and ice floes of the arctic north in the rather sensational manner of Elish Kent Kane, heroized in his time as a public speaker, American hero, and arctic explorer, before Thoreau began to gain popularity on the lecture circuit in Massachusetts. He was a bit of a competitor, and arrived in Boston with the huge drawings he had made of arctic icebergs that his ship had encountered and seen at first hand as an actual arctic sublime.

Arctic Glacier, Melville Bay from US Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin Grinnell (1853)/ American Philosophical Society Library

Thoreau famously prized Walden Pond as a site of purity from which to apply himself to watching the world, perhaps recuperated in the enthusiasm for viewing glaciers today in an era of ever-decreasing contact with the wild, the uneasiness of watching the retreating remaining glaciers in the warming waters of the northern seas is more than tinged with a sense of melancholy, capturing the sight of the few remaining glaciers and icebergs, and summoning what is let of Thoreau’s deep admiration of the wild. Thoreau would indeed be shocked at a shifting North Pole as a surveyor who, Patrick Chura has shown, prided himself on determining magnetic North by a “true meridian” if modest in many ways: accessing the “true meridian” was a more elevated sense of moral purpose and direction, as he navigated at night-time by the North Star that escaped slaves followed to secure their freedom. Thoreau was proud of his exactitude and precision as a surveyor of farms and of the woodlots around Walden Pond, mapped “so extensively and minutely that I now see it mapepd in my mind’s eye,” he wrote in 1858, to plot his motion across lots’ property lines,–as if the exactness of magnetic north was warranted to navigate the woods accurately.

Thoreau prized the ability to detect the undisturbed wilds of America just outside of Concord, Massachusetts, and in his own back yard, cultivating his perceptions of the wilds of the continent that still survived even in the age of the railroad and outdoor lighting, the timeless glaciers–or seemingly timeless iceberg–offer one of the last sites of the wild, a fast disappearing margin of nature, in a warming world and a world of warming oceans. Now, rather than haunted by icebergs, we are more likely to be threatened by prospects of glacial retreat. In an increasingly warming haunted by polar melting and glacial retreat, twenty-eight trillion tons of global ice melted between 1994 and 2017, raising the prospect of melting of the 70% of the earth’s freshwater stored in permafrost, ice-sheets, glaciers, and ice caps. Remote sensing led NASA to say almost elegiacally, “goodbye, glaciers” in 2012, finding almost 60% of ice loss melting in the northern hemisphere, and much in the Americas, northern Canada having lost 67 billion tons of ice in the previous seven years, southern Alaska 46 billion tons, and Patagonia 23 billion tons. The skills of engineering by which Thoreau, who built his own house in rusticated style, recovering the shingles from an Irish worker as Romans might reuse pieces of ancient buildings, fancied the environmental engineering feats by which glacial retreat had sculpted the ponds he boated, swam, drank, and skated in winter. If Kane had been inspired on his expedition by maps of an ice-free open arctic sea, we have trouble not standing in fear of the prospect.

Augustus Heinrich Peterman, 1852

At the same time as Kane set sail in search of Grinnelle, or 1855, Peterman combined the arctic panorama with intense cartographic scrutiny of the islands and icebergs of the frozen landscape, trying to preserve a navigable open arctic, combining art and cartography to tempt travelers to the prospect of Humboltdian voyages to the many islands and archipelagos of a partly frozen north.

Peterman, Karte des Arktischen Archipel’s der Parry Inseln, 1855

1. The scale of global melting is the negative image of globalization, haunted by a hidden story of dizzyingly increasing global icemelt and global melting. As increasingly warmer waters enter the arctic regions it melts more sea ice, allowing more sunlight to enter the arctic ocean, whose contracting margins trigger a feedback loop as more icemelt reduces the margins of arctic sea ice whose effects we are hardly able to process, let alone to confront.

T. Slater et al, (2021), Copernicus

Indeed, we are haunted by the image of glacial melting far more than we might imagine, and wherever we live. For the mapping of glacial melting–suggested by the data vis heading this post–is best understood as something of a negative map, as well as a map of tragic if not irreversable loss. It is a map that we will not need to travel far to see–per NASA, which has been monitoring glacial loss and ice sheets’ weight since 2002, the prospect of all glaciers and ice sheets melting would provoke sea level-rise over sixty meters or 195 feet. The message of the remote sensing GRACE satellites provided from 2002 to 2017, and GRACE-Follow On satellites after 2018, have yet to hit home, Emerson might say, perhaps as even accurate monitoring is only offering provocation to assess the shrinking margins of the arctic on the ensuing loss of habitat, warming ocean currents, that send ever less cold water to the deep ocean to trigger upwellings of nutrients, and indeed land erosion that rising sea-level can provoke.

Despite its persuasive power, this map remains largely negative, as it tracks ice loss, without the more terrifying consequences of a greater degree of icemelt, with significant consequences downstream. We imagine glaciers as if they had edges, but the margins of ice melt are an image globalization and the only recently conceivable prospect of the margins of arctic melting The arctic must be understood by its margin, not a line, whose changing margins–seasonal margins, margins of melting, and margins of glacial coasts–shown as ‘dripping’ in the header to this post, a projection revealing how much the loss of ice due to global warming has accelerated in the north.

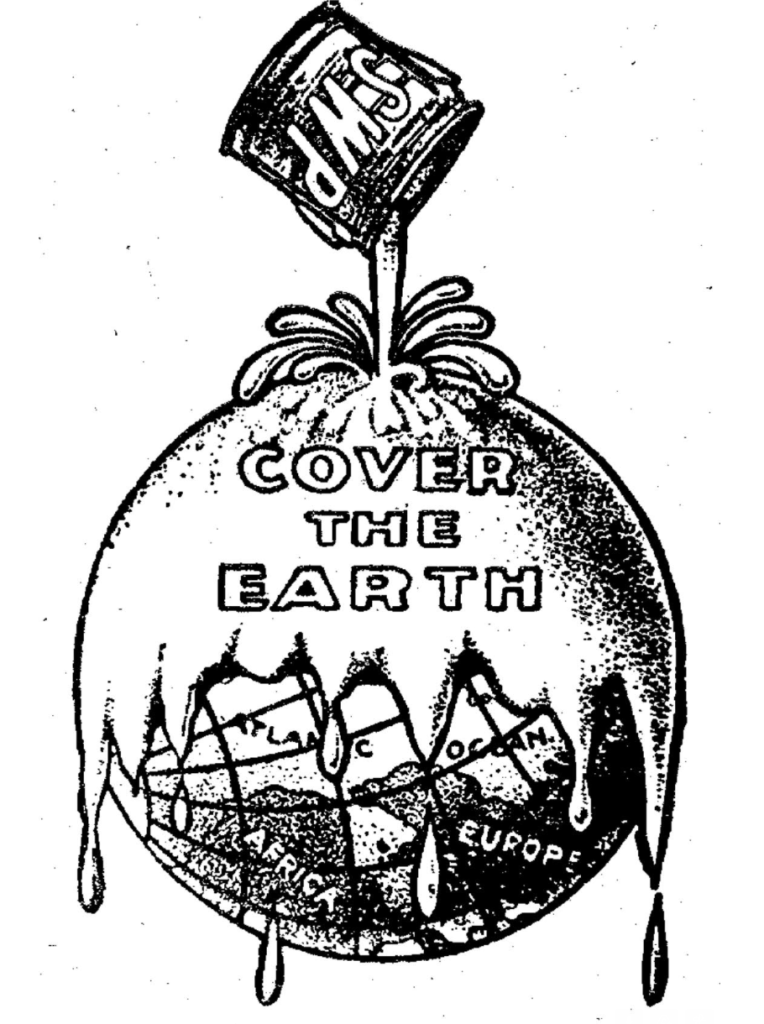

Faced with the burgeoning data of 267 gigatonnes of ice-melt as glaciers and ice caps recede, Niko Kommenda hoped to process remote sensing by statistical data profiles to render the loss of ice at specific as a sequence of spikes at fixed transects. Kommenda long considered possibilities of visualizing glacial melt as a visual projects editor at the Guardian, but the prospect of a recent doubling of rates of ice-melt over the previous two years suggested a need to illustrate the rising rate of flow as a massive shift in the calculus of water flow into global oceans. Recalling the use of spiking red to render rates of mortality of COVID-19 in American cities, if with a downward flow, he mapped a synoptic data vis of global annual change in ice mass. The global continents drip red, in a gripping distribution of the image of ice-loss that almost recall a geo-referenced remix of the classic Sherwin Williams logo, but of a world whose northern hemisphere was dripping with melting ice, as the small rise of several light blue spots suggest rises in ice mass mostly confined to high altitudes.

The map evokes geodetic take on the familiar Sherwin Williams globalism, repurposing the promise to “cover the earth”: in a projection akin to a transverse Mercator project like WGS84, flattens the earth to a single legible surface, haunted by the specter of nearly inevitable sea-level rise.

Henry Sherwin’s logo was, when it appeared after World War I, in 1919, a rebus signifying the victory of American capitalism and enterprise as it expanded to markets to a European theater, across the Atlantic Ocean, in an iconic image of free enterprise that new no national frontiers–

Cover the Earth indeed! The bold totality of Kommenda’s graphic suggests a bold distillation of international mapping tools, a drip drip drip that is almost unstoppable: rising rates of flow from the melting of global glaciers had doubled form the start of the new millennium, sounding an alarm after the first comprehensive studies of ice rivers revealed at high latitudes more meltwater leeched than the ice sheets of Greenland or Antarctica,–putting glacial thinning into prominence as a result of NASA satellite data. Remote sensing may have revealed one of the greatest historical catastrophes of losses of ice in human history, prompted Kommenda to tote up a compelling balance sheet of losses of frozen mass to embody the alarm glaciologist Romain Hugonnet sounded. The work of Kommenda’s mapping continued, as he focussed on the outlines of glaciers and glacial complexes–“The more accurately we can map glacier outlines, the better we can track their melting due to climate change,” Ann Windnagel of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, who has been trying to track the recent reduction of glacial complexes in the Arctic, Iceland, Alaska, Scandinavia, Antarctica, and Central Asia, as well as the Southern Andes, in a global assessment of glacial health–ranking the glaciers’ size and footprints as a long-lasting, enduring flowing mass of ice. To describe the “footprint” of a mobile form may be an unhelpful mixed metaphor, but the inventory of glacial size can map glacial health in relation to glacial fluctuations, ice shelves, ice tongues, ice thickness and ocean temperature, given considerable contribution of glacial melt to sea-level rise–often able to be compared with over 25,000 digitized photographs of glaciers, dating back to the mid-19th century, as a graphic historical reference for glacier extent. By tracking ice bodies and glacial complexes over time, snapshots help appreciate the extent of complexes in different regions.

The awareness of just how much glacial mass had been lost by warming became evident as it set the earth’s axis wobbling off due North in ways that may upset the geodesy on which the global grids we rely in satellite-based mapping rely. The hope to mirror the deep urgency Hugonnet felt to make the remote glaciers more immediate in a multiscalar global water cycle, able to encompass the considerable risks of huge downstream changes in regional hydrology, a fact that Hugonnet appreciates as a long-term resident of the Alps–the fastest melting glaciers offer a microcosm or test case able to contemplate the consequences of a global phenomenon of glacial melting–also known as glacial disintegration, as the over 200,000 global glaciers and glacial complexes have begun quite radically to reduce in their mass and size–releasing a considerable chunk of the world’s freshwater reserves to global oceans.

Although Alpine glaciers are far less thick than their polar counterparts, they risk to by 2050 in current warming scenarios to loose 80-90% of their mass, altering downstream ecosystems by starving them of water, even if not flowing into the open sea. The starving of landscapes from freshwater sources is striking; glacier outlines allow mapping shrinking glacial margins in many regions, including mapping glacier devolution in Alpine areas by a combination of optical imagery and LiDar, as well as old arial photographs, to help to take stock of the loss of about 30% of the volume of forty-eight glaciers in the Austrian Silvretta in Tirol, revealing a rapid recession of glaciers the recent emergency of formerly ice-covered rock face, after gradual glacial retreat, suggesting the loss of a massive repository of frozen freshwater. Zurich’s World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) has already detected a doubling of losses of glacial mass each decade since the 1970s; but the picture of losses at high latitudes and high altitudes needs to be made concrete for those living on near the coasts–despite the North Atlantic anomaly of decelerated mass loss.

Glacial Retreat in Tirol by Digital Elevation Models from 2017 (Black Boundary Lines)

We may lack commensurate memory or metaphors to describe the disastrous consequences of the disappearance of glacial mass, it never having occurred in human history–and any prospect of the growth of glaciers remain quite remote, and if folks continue to feel that “the science is still out on global warming,” the multiple impacts of global thawing will be far more less able to be visualized–or the species that will survive the different possible future scenarios of catastrophic climate change. The scenarios that have been lambasted and demeaned as “theories” but the record-low sea-ice places the survival of glaciers in Antarctica and Greenland that are surrounded by bodies of water at extreme risk of accelerated rates of disintegration that may advance to general collapse by 2050–the record lows of winter sea-ice in Antarctica this June 2023, over a million sq km below the previous record low set just the previous year.

We prefer to view the arctic with awe, and at a move. Or are climactic analogies bound to catch up with us, in inescapable ways?

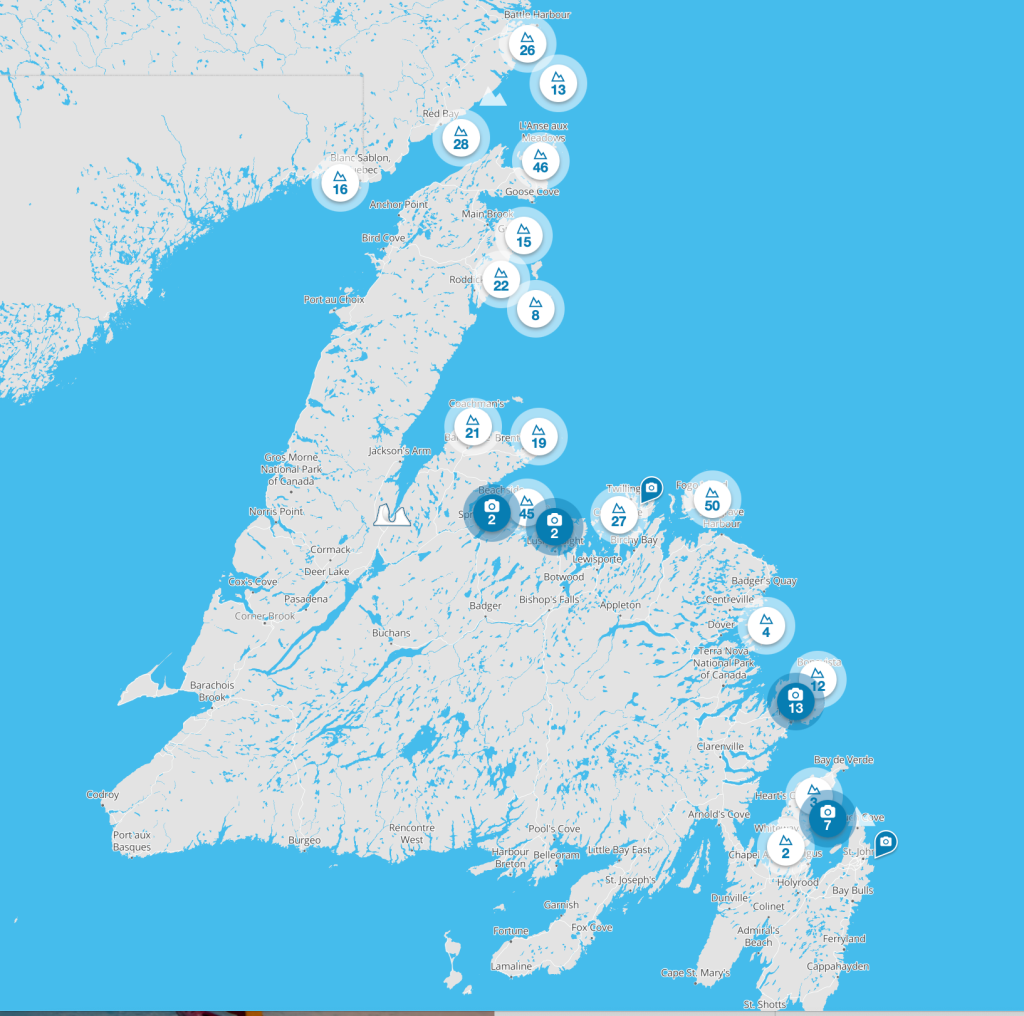

The current burgeoning riverflow as snowpack melts in California, but may well exemplify the potentially catastrophic effects of raging river water throughout the Central Valley. Increased riverflow from the Sierras have not only rendered rivers dangers, but changed habitat, submerging vegetation and prompting fears of erosion on narrowed riverbanks–and indeed the overwhelming of the drainage systems of the state. The changing calculus of icemelt from the Sierras after a boom year of rainfall and snow said to have ended a multi-year drought will challenge the coastal habitats of the state’s rivers, as well as endangering swimmers: surging rivers stand to submerge older habitats, and suggest the need for more local studies of ecosystems and habitat in the face of increasing glacial ice-melt. The stressors are unknown if unimaginable; icebergs suggested to be linked to awe and abundance and timeless abundance, as much as fragility. Alaskan wild lands, coastal ecosystems in Greenland, the Arctic, Labrador and Newfoundland would be threatened in ways impossible to imagine.

2. The glacial landscape is more acessible to those with the means than ever before, who might well imagine themselves as in a Thoreauvian wild. The expansion of polar melting has created, perhaps paradoxically accelerated, a new sort of ecotourism to search of remaining glaciers of solid blue ice. This seems more of a cross, to be sure, between the expeditions of Kent Kane and for purity channeling Thoreau’s attraction to the wilderness and the wild. Thoreau famously realized the glacial origins of Walden’s kettle morraine and glacial origins of Walden Pond’s purity by a glimpse of appreciation of its deep geological time as he stood by its stony shore. While the memorable image of him seeing himself in the snows of the Winter of 1846-7 preceded his epiphany of the glacial drift across New England, he focussed one spring after the pond froze on the almost animate veins and vessels in the patterns snowmelt created on the sandy banks of Walden Pond, more pronounced beneath the recently built railroad track, as the steep banks revealed “foliaceous heaps” whose interpretation he felt might reveal the secret of life, if not “nature in ‘full blast'” that he had so desired to discover in the wild. As he stood before the sandy banks of the Deep Cut beneath the tracks, as if witnessing ancient treasures uncovered by the construction of subway stops in Rome or Naples, he witnessed secrets of seasonal change and revivification of the vital spirits of Walden Pond in the life of inanimate sand, combining his own passion as a self-styled naturalist and interpreter of global history, in ways akin to the glimpses of calving icebergs, or of the epiphanic blue ice of ice ecotourists witness as they paddle off the northern latitudes in search of ecological grandeur of the wildstill able to be accessed or recouped off Newfoundland’s coast.

Thoreau famously found the most opportune moment for mapping the depth of Walden Pond in the midst of the preceding winter months, in January, 1847 when “snow and ice are thick and solid.” That winter, the arrival of over a hundred Irish laborers excavated ice of Walden for Frederic Tudor, the Boston ice-baron, using saws, ploughs, knives, spades, rakes, and pikes to remove some thousand tons of ice a day–and 10,000 tons in one week–that is often contrasted to Thoreau’s contemplation of the local and the infinite value of the priceless purity of the waters of Walden Pond. Tudor exploited the global circulation of ice packed in sawdust by train and ship that fed a global demand booming in the colonies and plantations for ice future cool drinks and ice cream on a far-flung market, in ways that offers an image of an earlier globalism, based on the growth of markets that failed to grasp the priceless value of Walden’s limpid transparency. But if Tudor and Thoreau are often contrasted, the enterprise by which Emerson was relieved to have the prospect of the “increased value” he might gain from his woodlot in Walden Pond by leasing the rights to harvest its ice to the businessman may well have provided Thoreau with a foil Thoreau detected in how Emerson perceived the “prospect” by which his woodlot by Walden Pond might recoup its cost and gain “increased value” to contrast to the thrift and economy by which he cultivated virtue while living in the woodlot quietly–and indeed fashioning a new sort of exemplary life for himself far from his father’s pencil trade or the commerce of Concord or Harvard’s academic halls.

Few sites of purity remain outside the arctic. But Thoreau discovered a method of sustained local observation of ecosystemic change that the melting of arctic glaciers demand. We risk devaluing how fast-disappearing glaciers feed ecosystems and ocean circulation, at the changed margins of arctic landscapes in an age of ocean warming. Indeed, the extent of expanding icemelt triggers not only feedback loops, but habitat loss, coastal erosion, and changing ocean currents that only local observation can track. If the order of neoliberalism dulled our senses to the disappearance of glacial mass, encouraging an era of denial even as arctic ice thinned, before the melting of 2007 trigered a shift in the thickness of sea ice with less ice remaining in the arctic seas from 2005, undermining the structures of glaciers, we are slowly leaving an era of denial in which maps are able to play an important persuasive role–both to rebut climate denialism and to come to terms with the new margins of the arctic, as arctic borderlands long imagined as permanent are poised to erode: by 2010, Greenland’s coast entered into a thin ice regime definitively, with sea-ice thinning in warming waters over the next decade. By 2019, one of the warmest summers in recorded history, Greenland’s ice sheet was losing some 12.5 billion tons of ice a day in the heat of the summer, in one of the largest events of melting since 2012.

Ice Loss in Greenland, 2013-19

If we have to travel ever further north to experience the timelessness of icebergs–“It’s taken them 10,000 years to get here, but you can discover them in just a click with IcebergFinder.com!”–the latest form of ecotourism seeks to celebrate the contact with a fast-disappearing north, whose “very narrow, very thin margins” have become far more narrow in the face of a warming arctic sea, as the surveyor W.V. Maclean told the pianist Glenn Gould, as we watch the ice floes of Hudson Bay. The stoic surveyor, pulling from his pipe, sought, like a modern Virgil, to summon the scarce abundance of the frozen arctic in ways that maps might ignore, for the CBC documentary Gould produced to show the northern reaches of Canada in a modernistic manner by overlapping audio tracks that commensurate with the “lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity” he saw as the role of art. Gathering awe for northern reaches of a nation he saw as generating insufficient awe for many Canadians, Gould clearly channeled his own fascination northward by rail and air, awed by the scarce margins of the northern reaches, the jagged edges of whose the margins of ice, embodied in the pristine barren of ice floes, his documentary reveals as a part of his own conception of art.

Pianist Glen Gould chose as a central subjects of his 1964 CBC Documentary, “The Idea of North,” the cartographer W.V. Maclean, as the surveyor with first-hand expertise of agrarian prospects of northern Canada offered a dry witness to the arctic to invite audiences to the north, far “from the noise of civilization and its discontents,” in an odd use of Freud’s phrase, not as an uncanny, but an the Virgil of unfathomably vast arctic regions entral and on the margins of Canadian identity. The surveyor offered a fitting profundity for the CBC documentary by inviting to reflect on the arctic while hearing a Sibelius symphony, which, despite the thin profit margins, was promoted as a sort of virtue that Canadians had for too long overlooked, daunted by the prospect of extensive rail. despite its thin margins, the arctic was the land of margins, demanding its own poet.

The thinning margins of glaciers and of sea ice are however increasingly hard to convey tranquility. The illusion of the smooth surfaces of global capitalism and markets are perhaps impossible to be reconciled with the jagged edges of arctic ice, or the consequences of the new margins of the arctic, and terrifying realities of the prospect for arctic melting–or global melting, a long neglected component of climate change. If the arctic circle is drifting northward at a rate of 14.5 meters every year, arctic melting accounts for over a third of sea-level rise, and the Antarctic circle shifts south by fifteen meters every year, the warming atmosphere melting long immovable glaciers. Shrinking margins of sea ice have retreated annually, as the Arctic warms four times the rate of the planet, as accelerated Arctic warming in the recent decades–spiking in 1999 and the mid-1980s–suggest that seasonal warming stands to cause massive loss in sea ice that changing arctic margins, and our understandings of the north, challenging earlier simulations and climate modeling.

These are margins that the point-based tools of geospatial technologies are pressed to assess on a local level or “downstream” from the deterioration of the arctic ice-shelf. It is as if we started to loose memories of the past landscape of the north: arctic sea ice has steadily declined since 1979 at the astonishingly rapid rate of 3.5-4.1% per decade. The scarcity of ice in the shifting margins of the north reveals quite different rates of ice melt; warmer waters beside the margins of shores have revealed striking anomalies of ice volume: the levels of sea-ice in May, 2023 were the ninth lowest on record,–considerably below the average of 1979-2022–as the decline of arctic ice elevations, the very age of arctic had precipitously declined by 2016, the “perennial” sea-ice more than two years old now a fraction of what had long been the significant majority of arctic ice.

The consequences felt downstream on local ecosystems, habitat, and coastal health we have yet to map. As impressive as statistical cryosat data on the thickness of ice-sheets across Greenland and arctic regions, we remain fettered by the difficulty of cognitively processing of ice-thickness anomalies, as great as they are, of a pointillistic character–to quote geographer Bill Rankin, whose coining of the term pointillistic cartography may well be steeped in his arctic surveys.

Sea Ice Thickness Anomaly For April 2023, Relative to 1997-2020/CryoSat 2, AWI, v. 2.5I

Only by looking in an iterative, analog fashion at the downstream consequences of habitat and ecological niches can we train our minds to better interpret statistical pixellation of ice-thickness variability, and the consequences of those dark blue pixels that crowd Greenland’s northeastern coast, and much of the Canadian far north on the edges or expanding margins of the once-stable Arctic Circle. Each deep blue dot of a meter and half anomalies in reading the fields of light blue pixels the Interferometric Radar Altimeter notes, where warming waters move north of the arctic circle, driving the rapid rates of ongoing steady shrinking of polar sea ice–and the disappearance of permanent sea ice, to judge by the seasonal retreat of frozen seawater in recent memory from the pole during the past two decades against the 1981-2010 median.

While we isolate this as a northern phenomenon, limited to an “Arctic Sea,” its constitutes nothing less than an undermining of the collective memory of oceans of the flora and fauna who are its residents–perhaps particularly in Alaska and Canada’s north, but also Siberia and Greenland.

Seasonal Extent of Sea-Ice at North Pole against Median (yellow line), September, 1980-2020/ NASA Earth Observatory

The decline of the age of arctic sea ice is a diminution of arctic memory, and a change in the arctic landscape. It was not anticipated however, in ways that may seem to accelerate the fast-changing nature. Despite longstanding convictions of the immunity of Arctic permafrost to global climate change, as if the coldest areas were somehow immunized or inoculated against thawing.

Yet Google Earth Engine datasets have over the last fourteen years indicated a massive increased in arctic landslides triggered by melted ice in the permafrost during the summer months–“thaw slumps” of long frozen matter able to release potent greenhouse gases as methane emissions in the atmosphere and carbon dioxide in the fastest warming areas of the world of the high Arctic are unable to be stopped–reshaping the arctic landscape in ways that may in time lead to the eventual disintegration of the ice sheet. Glacial melting prompts the growth of coastal landslides created by the collapse of rock glaciers long held together by ice–avalanches and landslides grew in 2014-19 across the warming north, catalyzed or triggered by glacial retreat. In the face of such expansive rewriting of the arctic margins, we risk ignoring the more analog, recursive, local observations of wildlife and habitat that Henry David Thoreau, for one, detected at Walden Pond’s margins, preserving tallies of the dates at which irises, lilies and blueberries bloomed around Walden Pond, allowed Charles Davis and Richard Primack to understand and indeed measure the climate change by howh warming’s shifted the dates of flowering of irises and lilie–giving new sense to Thoreau’s stay at Walden as an experiment,–beyond as one of living in nature or refining his own abilities of sense-perception, but providing an experimental baseline to observe the effects of global warming.

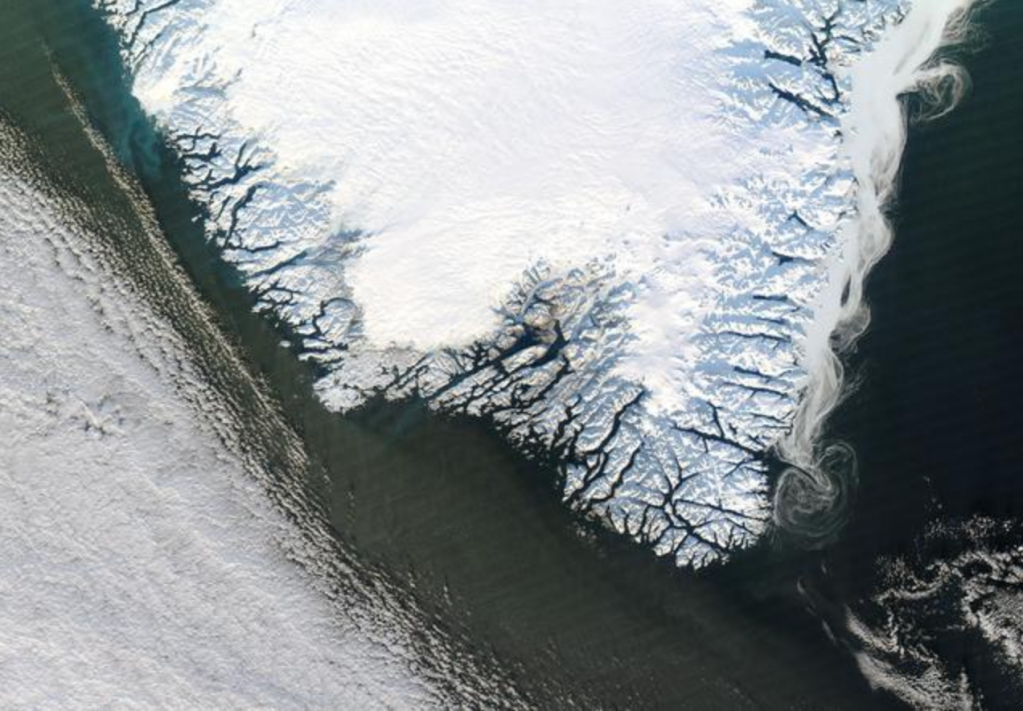

The growing margins of glaciers, including ice tongues form from the flow of ice from many northern glaciers in the northern glaciers of Greenland’s ice sheet and the largest southern glaciers track the migration of long-frozen ice to the arctic sea, increasingly visible in the last twenty years. But can we come to terms with the study of their effects outside of similar analog observations?

Greenland’s Melting Ice Sheet/NASA/GSFC

3. The retreat of glacial ice sheets in Greenland, which is melting in a warming ocean past the point of no return, is already losing 255 gigatons of ice each year, 2003-16, and while its melting is not inevitable, its melting–measurable by elevation loss–would increase as its elevation lowers to an ever warmer atmosphere. And as the coast of Greenland, long a source of iceberg transit, seems to melt, he viewing of icebergs, those last remnants of a frozen Arctic Ocean, are tracked not as sites of self-reliance, are crowd-sourced for tourists, as if testimonies still promising access to a divine,–

-as if to arrive at the Walden-like purity of a blue-tinged spectacle of ice off the shores of Labrador or Newfoundland, while they are still visible, still floating as remants in the warming arctic waters.

IcebergFinder.com/Newfoundland and Labrador

There are many reasons for the relatively sudden scarcity of sea ice in the north, and many signals of the growing disappearance of glacial mass. The proliferation of “glacial tongues” in an ever warming atmosphere offers a spectacle of the melting of glacial mass, in to the ocean or freshwater lakes, appendages of frozen glacial water that arise from rising ocean temperatures off of the coast of arctic regions or from the melting of subsurface glacial ice that form ice terraces. If geodetic mapping is often described as a layer of mapped space that exists as if superimposed upon the earth’s surface, the data of deteriorating glacial mass can be understood as a creative form of tracking the remaining glacial ice, mapping is not only “flattening” of the earth’s pathways of commerce, but a dynamic calculus of mapping elevations, routes of ice-loss, and melting rates.

April 7, 2019/Earth.com

Much concern has been devoted (and ink spilled) on the “slippery slope” arguments as invoking catastrophic consequences in sensationalist news designed to trigger alarmist fears in a polarized era where public messaging creates ideological divides, demands to be heeded more than logical fallacies only designed to provoke alarmist reactions. The ice tongues that are shearing off coastal ice in Antarctica, touching warmer waters it freezes marks a loss of glacial mass that might have never been imagined in earlier centuries. Indeed, warming waters suggest a possibility of ice-melt that seems destined to stack the deck against global climate stability, a psychic shock regardless of optimism or pessimism about climate change.

5. How to come to terms with the massive world historical shift of deteriorating glaciers, the crumbling of the frozen timeless artifact? The question is so vast to be perhaps beyond the charge of most cartographers, but deserves a central place in the scope of a “speculative cartography” of mapping the global impact of glacial retreat. It would be a way of mapping a changing way of being in the world, therapeutic in organizing a fast-shifting reaction of climate and human activities, and charting a prospect of the scope and scale of irreversible alterations of the global atmosphere. The fast-changing nature of the arctic offers a better purchase, nonetheless, on the fate of the planet, which geospatial techniques are perhaps inadequate to fully track, assess, and reveal.

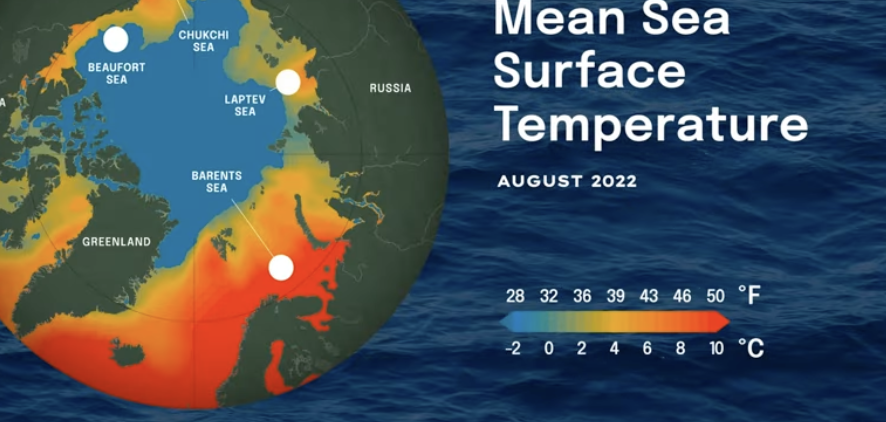

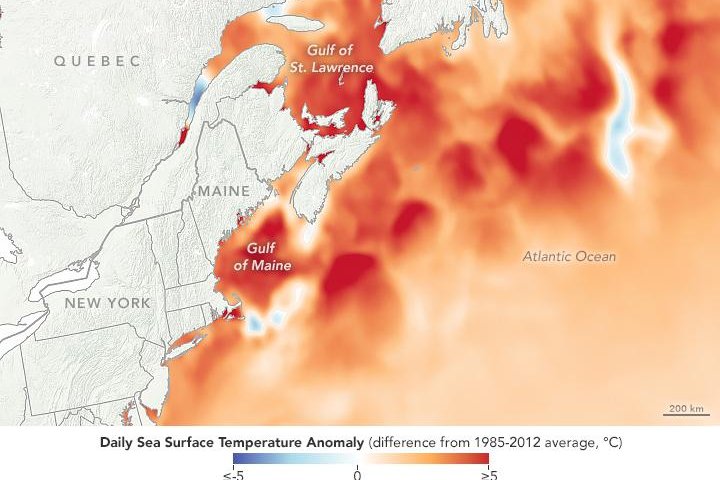

But since 2010, the monitoring of global environmental monitoring has crated an escalation of a visual archive of ecosystems and habitat that map trends and allow one to correlate planetary environmental change to human activities on a local and global scale. The existence from 2010 of a platform of the elevation of arctic and antarctic ice sheet and ice shelves can track the consequences of ocean warming, as northern Atlantic temperatures approach record heights, a full degree centigrade above normal, sea surface temperatures four degrees above average–far beyond the anomalies in the North Atlantic already deemed exceptional a six years back, as coastal waters in the Gulf of Maine alarmingly warmed seven times as fast as the global ocean in August months.

August 1-31, 2018

The warming waters of the northern Atlantic were rendered in a striking palette of the point-based readings of temperatures and islands of colder waters. But the relation of land to water–and of glaciers to warming Atlantic seas–raise question of the artfulness of maps in an age of global warming, and the shifting relations of land to sea. For these relations are perhaps ineffectively represented by the lawyers of sea surface temperatures, or even base maps of sovereign space, as once-fixed northern boundary of continents has begun to retreat, and the land-sea divide blurred by ever-greater glacial retreat. Even as new shipping routes are drawn in anticipation of glacial retreats and the melting of arctic regions–only understood in the abstract back in 2013–the increasingly concrete consequences ready to cascade from the inevitability of polar melting.

Reduced Sea-Ice Thickness and Polar Shipping Routes/New York Times, 2017

If navigation risk has been steadily reduced since the 1980s, the increased expansion of shipping routes around Greenland reveal the near absence of sea-ice from a region where ships were once regularly iced in. But the real danger has flipped-from dangers to shipping routes of coastal trade to a growing awareness of the dangers of the dangers of ice-loss, and erosion, that have mapped to the death of vital habitats, keystone species, and erosion of long resilient coastal communities.

The contested questions of polar sovereignty, raised in observations of ocean waters are increasingly associatively if not reflexively linked to oceanic experiences–hurricanes, flooding, and rising seas–that impinge on terrestrial sovereignty are stretched thin as we approach arctic seas at the poles, which can remain contested spaces of overlapping or contested sovereign divides, as argued in an earlier post in this blog that focussed on sovereign claims and the instability of sovereign spaces in an age of global warming–and the warning signs of a century of rising heat. Yet are color ramps sufficient to communicate the cascading events that melting of glaciers and sea-ice trigger, and the cycles of polar warming they are predicted to trigger?

While glacial melting is associated with a casualty of summer months, the low ice levels in Antarctic winters suggest as great alarms as increased extremities of icemelt in the higher northern latitudes. We can look forward to photographs of ever-receding level of arctic sea-ice–currently about the same as last year, but for scientists at Belgium’s UC Louvain, potential record-lows of just under three million sq km–295 sq km of sea-ice, a current record in the age of satellite observation–even as median projections of 4.54 million sq km lies below the 4.9 million sq km observed in 2022, slightly higher than projected late-summer forecast for the previous three years. The margins of ice calculation, find fragile summer conditions for the ice sheet’s thickness, and different forecasts of the “ice-free” date when arctic ice drops below a threshold of thickness, just a sixth, or 15%.

Sea -Ice Outlookt, June 2023 /Actic Consortium of the United States

–but quite scarily low initial conditions for sea-ice thickness across models (RASM; AWI; GFDL).

The observation of arctic ice may be a way to register global warming hat tarrived just in time, but one realized that it might be too late. Fort eh technology of remote observation of ice thickness reveals a terrifying amount of of Antarctica’s coast fringed by floating ice shelves and sea ice, as we monitor the calving off of icebergs with increased from an ever-deteriorating sheet of arctic ice. There might be nothing better to focus on as we start a new season of summer, when leting rates stand to rise. The appearance and proliferation of the slippery surfaces of “ice tongues” on coastal glaciers sound alarms of the growing dangers of global warming we demand greater artfulness to map. The seasonal ice tongues form from meltwater at the base of glaciers, extending out to the sea in winter months as seawater freezes at their base, as links of glaciers to ocean register of the loss of glacial mass; the margins of glaciers will break either into icebergs or floating sea-ice sheets.

Ice Tongue off of Erebus Glacier at Ross Island, Antarctica

Reflections on ice breatking–and ice melting–suggests a mapping less rooted in data points. Melt rates remain less visible or mappable by points, their seasonal melting registers a dramatic loss of glacial mass, ice flow, and ice sheet loss we are only starting to map or comprehend. The difficulty of getting ones mind around the dimensions of arctic warming and glacial melting, moving across land-sea divides and boundaries, not compellingly rendered by the point-based syntax of most global projections, demands a relation of map to viewer, and modeling to mapping, able to bridge land and sea by melting rates. Polar Portal has tracked the melting of Greenland’s ice sheet by over 255 cubic km annually, increasing the warming of arctic waters to add about a millemeter of sea-level each year, 2003-16, the ocean interface of glaciers may be an increasing focus to discriminate the contributions of surface melting, iceberg melting, and iceberg calving to global sea-level rise.

Have we neglected to pay attention to the changes in the polar landscape, not only available through remote sensing, and the impending and projected prospect of the disappearance of alpine glaciers by the century’s end? The danger of creating future landslides, and global ecosystemic eruptions and disturbances triggered by the rising of ocean waters across the globe, as the nearly nine millions square miles in the northern hemisphere alone stand to thaw–about 15%, triggering massive instability in a large region of continuous permafrost that we have not yet come to terms even as it threatens to destabilize the continuity of our very notions of the nation-state.

The recent loss of ice sheets and mountainous glaciers in the past decade have paralleled the loss of the arctic ice sheet. The largest tidewater glacier of the northern hemisphere is already losing considerable ground to water, as rising ocean temperatures have led it to shed more water into the arctic seas. We are poised at a moment of arctic melting so intense that calls for a more “empathic cartography” Glacial loss has contributed to almost a fifth of sea-level rise, and the thinning of glaciers that lie just off of the ice sheet of arctic peripheries have accelerated two-fold over the last two decades, as the acceleration of ice loss on the edges of ice sheets of Greenland or Antarctica have accelerated far beyond the Greenland or the Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets.

If icebergs had trapped the Grinell expedition in the mid-nineteenth century off Greenland, much as the density of fish trapped the first sailors making landfall at Newfoundland, retreat of icebergs is mapped as opening the arctic seas to new routes of commercial travel. But there are many darker sides of glacial retreat that provide clues and hints about the crumbling of ice-shelves in an age of ocean warming. If this blog discussed ways earth observation affords multiple compelling ways of visualizing the Anthropocene–from the increase of global brightening to environmental pollution and degradation, to the effects of river discharge of fertilizer entering the coastal ocean as challenges of remote observation, we face the danger of flattening the global ecological impact of these changes. For the degrading of both polar ice and land-based glaciers transcend efforts of environmental monitoring, and open questions of the stakes of mapping and coming to terms with glacial loss.

6. For are not maps untapped ways for coming to terms with the potentially devastating cascading processes of anthropogenic change? To map may not mean an ability to reverse-engineer, but offer tools to grasp the extent and increased contingencies of global change, especially by illuminating what are the edges or critical boundaries of climate changes that escape a purely meteorological register or dire predictions of yet another apocalyptic Jeremiad.

We track the deteriorating ice sheet of polar regions, mapping icebergs remotely by satellite as they appear, designating each as they calve into smaller bergs, naming each by the antarctic quadrant they were first sighted, and suffixes identifying icebergs calved from bergs already separated from the ice sheet; May 13, 2023 saw the calving off of A-76A, A-76E, A-76F, A-76-G, A-76H, A-76I, making the Weddell Sea an icy alphabet soup where smaller icebergs multiplied til they became too small to observe. It is tempting to create a time-stop tracking of the fragmenting icebergs of arctic regions, if the scale of icebergs would be impossible to allow them all to be discerned–but the shape of these calved fragments are perhaps poorly mapped as shape files, as their shedding of meltwater into the surrounding oceans will have cascading effects in ocean circulation, sinking less and less cold water into the deep ocean, and the overturning that increases the upwellings and ocean currents that help to provide offers food and needed nutrients to the global oceans at surface level. Rather than being focussed only on the arctic, such a fully three-dimensional map would have to encompass the rates of ice-melt, and the effects of the water shed from calved icebergs in the ocean’s biosphere.

Rather than streams of ice that created vast rivers that took Wordsworth’s breath away, unveiling Mt. Blanc’s “streams of ice” and “array of of might waves” coursing in the Vale of Chamonix, that obliterated all living thoughts, or the serenity that Shelley found in the mountain–gleaming on high, “still snowy, and serene,” in”frozen floods, unfathomable deeps,/blue as the overhanging heaven”–the icemelt entering the global oceans are a tragedy of the accelerated shedding of water that cannot be seen or clearly tracked.

For the greatest difficulty is not only to integrate remote satellite observations beneath cloud cover into stacked map tiles seamlessly, but to imagine the comprehend the cascading impact of shedding water on habitat, and as a form of ecosystem change, as the edges of these polygons contract.

Remote satellite observation allows real-time tracking of iceberg deterioration, compiling an increasingly important form of environmental intelligence, trying better to understand the nature of wave-ice interactions as temperatures rise, with an eye wide open to “downstream” marine conditions, as an increased amounts of icemelt enters global oceans with major consequences for habitat, environmental niches, and water temperatures as well as sea-level rise. Coastal boundaries of the Antarctic ice shelf are constantly shifting, as fragmentation of glaciers needs to be constantly updated, as we try to come to terms with the lack of clear edges of arctic seas and the increasing meltwater that is entering them. If Mt. Blanc famously offered Romantics a landmark of a glacial sublime–“still, snowy and serene” were its “unearthly forms” of ice and rock–melting icebergs suggest the inverse of “frozen floods, . . ./Blue as the overhanging heaven, that spread/And wind among the accumulated steeps,” a hollowing out of the majestic views of the past. The effects of multiplying sea ice fragments, and the less easily registered addition of streams icemelt downstream are far more sobering than solemn or serene and, scarily, still not well understood.

The phenomenon of glacial thinning at the edges of ice sheets affirms the importance of mapping the risk that will be faced by a full two-thirds of global land-based glaciers by the start of the next century, in the most optimistic projections increasing sea-level by perhaps 3.5 to 6.5 inches, and displacing ten million globally, and shrinking global water supplies on which much of the world depends from mountain glaciers. Already, glacial melt has contributes a third of sea-level rise. As glaciers are disappearing in the Alps and Norway, glacial mass loss suggests one of the most compelling reasons for the need for pledges to reduce climate change, however unlikely to occur, and place a on the mapping of glaical mass of the 200,000 land based glaciers on which we need far better datapoints. The fragmentation of the edges of the Greenland’s ice shelf are an illustration of the astounding geographic retreat of some 85% of global glaciers worldwide between 2000 and 2020, a direct response to anthropogenic change–a loss of frozen water whose effects or extent we cannot fathom.

The relation of glaciers to surrounding sea and ice-temperatures create different rates of melting, rates of glacial flow, and thickness, that the open-source engine, Open Global Glacial Model (OGGM) tries to offer long-term modeling of glacial melt less tied to mass. OGGM has since 2020 tried to offer a long-term tools to model glacial melt by a glacier-sensitive model sensitive to local specificity of glaciers–flow-lines, melting rates, directionality, to model parameters of glaciers across the world using observation-based area-elevation, parametrizing width and thickness changes over time, and in relation to sea-water and air temperatures, to grasp the huge losses in glacial footprints in sq km., using the flow lines and directionality of glacial melt to calibrate losses specific to their situation and location, and to the surrounding environment, but also separated by ice-divides in a clearer inventory of glaciers that allow a clearer picture of glacier flow.

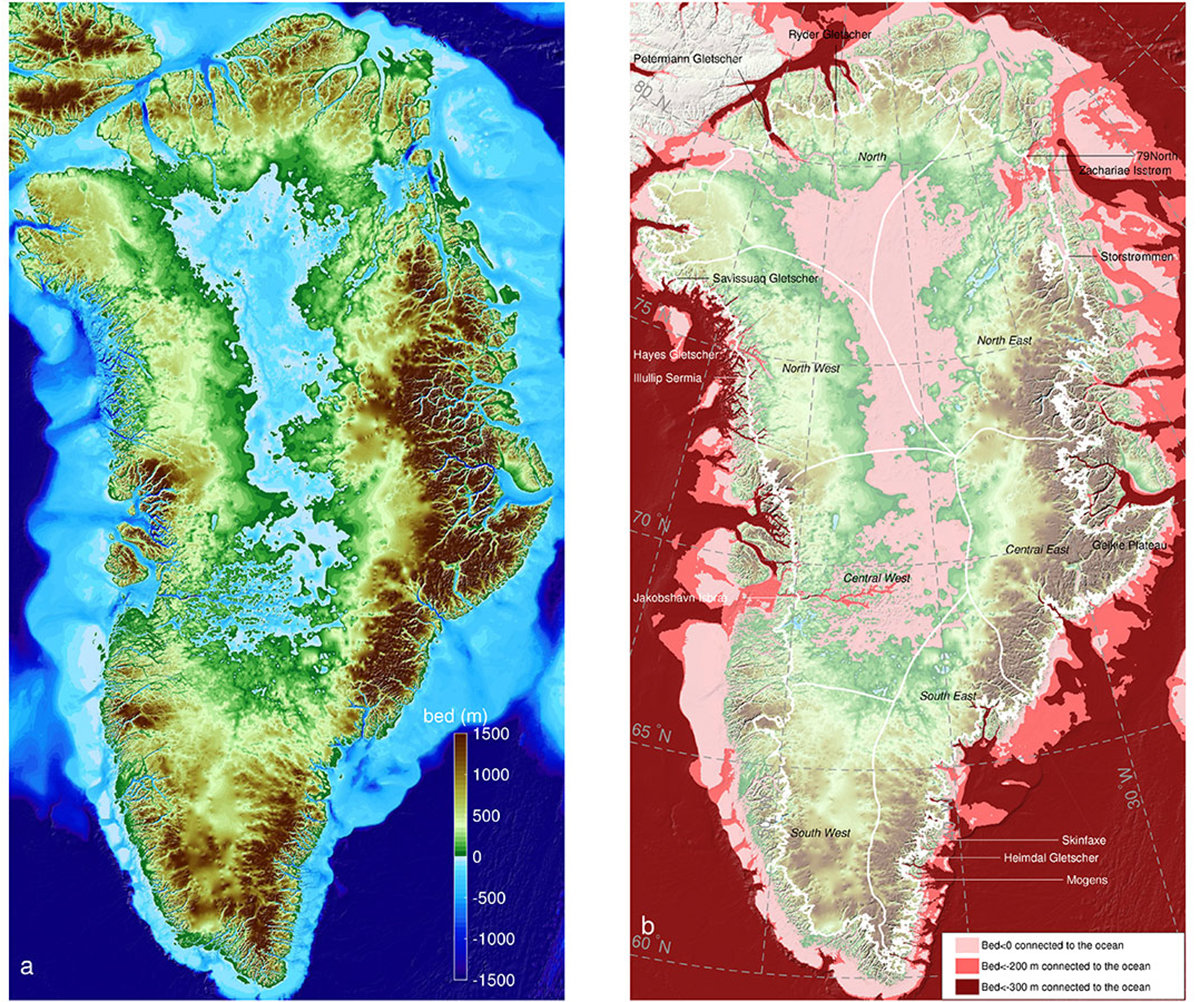

7. The departure of glacial ice from the global landscape is due to warming air and warmer water that washes the edge of the glacier, eroding edges of the ice shelf. The glaciers present in totality terrifying new landscape of impermanence, whose edges seem to shrink before our eyes. While much of the glacial mass of Greenland is indeed not visible to the eye–oceanfront glaciers lie largely below sea-level, bathed by waters from a frigid Arctic Sea, glacial mass below 600 feet seems to be breaking from the ice sheet in ways visible from satellite imagery.

But they fail to reveal the increasing vulnerability of deep glaciers lying underwater to ice melt–

–evident in the retreat of coastal glaciers whose inland retreat of oceanfront glaciers seems to have resulted from resting on melting foundations deeply vulnerable to warming ocean currents.

–in ways that are echoed by the scale of the loss of glacial ice on the edges of the Antarctic ice sheet. The crumbling of the Antarctic ice sheet’s edges offers dramatic evidence of the accelerated ocean warming that bears the brunt of global warming–Antarctica is shedding some 150 gigatons of ice annually between 2002-2020, on average, as Americans fought over the Paris Accords and human-induced Global Warming.

The glacial melting has created sea-level rise at a rate of almost a half a millimeter a year, per NASA climatologists tracking the terrifying scale of glacial losses in the Antarctic Ice Mass, a loss that is particularly pronounced on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. And if this map is dated, the recent shifts of global sea-surface temperatures, recently hitting a new high, presented the greatest anomaly yet on record to the Berkeley Earth Institute, a sudden spiking of the temperatures as sea surface temperatures off of South America some five degrees above the 1971-2000 average and nearly fourteen degrees off the North America’s Atlantic coast, shifting land temperatures: but the rapidly melting sheets of Antarctic ice to meltwater may slow the circulation of global oceans that long regulated global temperatures, soaking up excess heat, in ways that stand to reduce the oceans’ contribution to lowering global temperatures in an age threatened by catastrophic changes created by increased heating.

The record-low levels of ice in the Antarctic sea stand to change global oceans in terrifying ways, creating less hospitable oceans that risk how the ocean remains a habitat. In returning lower quantities of cold, oxygenated water to the deep ocean, the melting of coastal waters of Antarctica stands to slow down the sinking of water to the ocean floor that triggers an “overturning” circulation that sends more nutrients upwelling to oceans’ surface. The lowered circulation stands to allow more heat to increase the ice loss of West Antarctica even more, and increased thinning of Antarctica’s ice shelf far beyond the calving of icebergs for the last decade, as a slightly earlier study by E Rignot revealed pockets of glacial melt rates that exceed the rates of glacial calving (shown in red), suggesting the danger of disruption in stability across the ice sheet’s increasingly delicate edges with effects that cascade far beyond the poles or polar setting.

Mapping Ice-Shelf Melting v. Glacial Calving in Antarctica/E. Rignot et al (2013)

The dramatic loss of glacial ice has sharply accelerated through the election of a candidate who rejected human-caused climate change as a scam devised to increase government regulations. Rather than evidence of a rigged theory, the losses of ice mass suggest the Antarctic and the Arctic seas are so easily compartmentalized and hidden from view that we could become so purblind to the effects of climate change on global oceans? Far better to travel north to chase icebergs at still higher latitudes, in hopes of glimpsing the remaining if far reduced fragmentary bergs that float almost elegiacally off Greenland’s coast and they can still be seen.

Global Warming Leaves Reduced Icebergs Floating off of Kulusuk, Greenland in 2019/Felipe Dana/AP

Is it any surprise that at this rate of loss to the ocean, the viewing of glacial loss suggests a calculus we are not able to really fully grasp from remote sensing alone? Few remotely sensed maps can capture either the underwater glacier, o thick slab of the ice-shelf as its edges are “calving” and breaking into the sea as its underside melts. The massive shelves of Greenland and Antarctica are both quite thick–up to 10,000 feet thick in some places, and even up to 15,000 feet in others–but the calving of ice on their edges before warm air or water can be due to meltwater running down the glacier to bore holes in the ice sheet, and the melting of the sub-ocean shelf, reflecting a loss of mass on the oceanfront glaciers’ edges. The Kane Basin is still a site for viewing the Humboldt Glacier, the largest in the nothern hemisphere, i tabular icebergs that calved off it in Kane Basin are far less majestic ice formations than Kane once saw,–or the 110 km front of Humboldt Glacier itself.

© Nick Cobbing / Greenpeace

© Nick Cobbing / Greenpeace

Elisha Kent Kane, Frontispiece to Arctic Explorations

8. Romanticism spanned a broad geographic revaluation of the “wild,” extending from Mt. Blanc to what Thoreau called Mt. Ktahdn to new northern latitudes, in some eagerness to find arctic mirrors of Mont Blanc. The travels to the North Pole that explorers like Walton, the fictional narrator of Frankenstein, or indeed the actual arctic explorer Elisha Kent Kane, sought landscapes of enduring emotion, in the liminal space of an arctic world. The romantics fascination with visiting glaciers in the Arctic Sea led to a romance of glacial calving off Greenland’s coast as an opportunity to look back through time at the geological formations of glacial drift during the mid-nineteenth century, or as one move into the primeval timeless landscapes of the abundantly glaciated open ocean sea–Kane’s drawings and watercolors were models for an upwelling up of images of the splendor of arctic isolation and magnificinece.

Passage through the Ice, June 16 1818, Lat. 70 44 North

James Hamilton, Watercolor of Arctic Scene After E. Kent Kane, 1856 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Over a century ago, spectacular panoramas of virtual polar tourism presented a major venue for popular fascination in print culture, as explorers of arctic waters presented a polar sublime, of a monumentality akin to visions of Mont Blanc described by the romantic poets, popularizing haunting images of “towering icebergs, approaching each other like promontories . . . with cavernous recesses.” The rhetorical power of reading first-hand accounts of the calving of icebergs in early polar exploration provided a model for marveling at how the breaking off of icebergs from the “ice-locked coast” of Greenland indeed revealed the ability to witness at first-hand the “genesis of icebergs on the face of the globe,” migrating the frozen north to ever higher latitudes, to make manifest or map a center of global fascination for an era of globalism long before globalization.

The ocean travel of the bergs from Greenland’s coast led to a fascination with the parthenogenesis of ice, “calving” off icebergs that travelled the world as icy sentinels. Today, we witness the increased calving of large glacial masses from Antarctica drift into the ocean north, regions the size of Manhattan, Delaware, and Georgia, but have trouble mapping how 4,000 square miles of ice floats out to sea. Cultivating any similarly ecstatic relation to the frozen ice has its counterpart, perhaps, in the modern elegiac echo that is difficult to process, but is transformed, mutatis mutandis, from the sublime to its own, new form of trauma that we can’t come to terms with, far less suggestive of genesis than of apocalypse–and we don’t want to go there yet.

Antarctic Iceberg A688A Floats Out to Sea

As Kent Kane’s senesational explorations of the arctic sea from his safe harbor on the shore of Walden Pond, natural scientist Henry David Thoreau may have taken them as a basis to integrate Walden in a global geography of his own. Thoreau would profess little interest in the Philadelphia physician’s description of these “gigantic monsters” of icebergs calving into the frozen “mysterious sea” off Greenland’s ice-locked coast; if the polar explorations of Grinell had been widely celebrated, Thoreau was committed to a disciplined discovery of transcendence in the local: “Does Mr. Grinell know where he himself is?” he asked readers of Walden, a bit flippantly; “Be rather the . . . Lewis and Clark and Frobisher of your own streams and oceans.” He brought global explorations to Walden, admiring how the landscape he lived as sculpted by the retreat of glaciers, creating deep kettles like Walden Pond. (He may also have harbored considerable jealously about the animals, birds, and plants Kane brought back to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, including a narwhale tusk of considerable fascination that held a prime spot in the Academy’s museum.)

These objects were surrogates for a sensational narrative of travel, creating the image of visiting icebergs in the treacherous frozen waters afforded something like a new global sublime–

Elisha Kent Kane, Arctic Explorations (1856)

–able to be replicated in the sublime Thoreau found at Walden Pond’s pure waters, in the wilds just outside of Concord, with no need to travel beyond the very same longitude and latitude he lived to experience the very sense of primeval grandeur that the plates engraved for Kane’s travel narrative provided audiences of American readers only several years later.

The comparison of Kane’s Arctic Explorations and his own attention to the freezing, melting, and thawing of Walden Pond and the landscape adjoining was not only metaphorical in its evocation of a poetic sublime that both Kane and Thoreau channeled in literary as much as geographic terms. Thoreau intuited Walden as a glacial lake in his Journals, left by an arctic edge across Sudbury plain, “as if the snow and ice of the arctic world, traveling like a glacier, had crept down southward and overwhelmed and buried New England” (March 1852) burying glacial ice in its wake. Thoreau paled before the wonderful purity of Walden Pond’s blue transparent waters “as if the water were just poured into it basin and simply stood so high” (April, 1852) to create an inland sea that offered him safe harbor. Casting Walden Pond as an inland sea one-upped narratives of arctic adventure, as Kane’s own later account; Thoreau imagined “towering icebergs . . . with cavernous recess” in the winter landscape of New England, rather than out at sea. Perhaps reacting to deep snows of 1852, as Thorston has argued, Thoreau clearly conjured an ancient arctic landscape around Walden. But he mediated the purity of the arctic sublime in conjuring a painted image of Winter in which “the icebergs should gradually approach,” echoing the sublime of Massachusetts’ winter landscape.

Thoreau aestheticized glacial loss as leaving a train of pure lakes, as if speculating that the very same local landscape he marveled at appeared shaped by glacial drift–and mapping the very glacial iceberg into the Massachusetts landscape he had mapped. There is something like a literary glacial drift that he took delight in, contrasting to the vision of Mont Blanc, in what he called “his lake country,” and to which he contrasted the sublime of Patagonia. By March 1852, he seems to have placed Walden in a paleo-valley of a lost north-flowing Sudbury River that once ran over the region of lake, and the shoreline of a glacial lake of the Sudbury Plain. Without calling Walden the result of glacial icemelt left to explain the unique transparent purity of its waters, it was a spectacle as worthy of attentive study as the arctic wilds of the icebergs Kane described, as if the “mimic sea” of the ponds waters had the very same purity Kane would have witnessed off Greenland’s coast. While it is hard to note that we now see the disappearance of global ice and arctic warming as a final consequence of the commercial globalization of trade, or that we see the impending disappearance of global ice as a final consequence of industrialization, the awe of glacial observation began as a part of a global narrative. And of visualizing a historical scope able to transcend place.