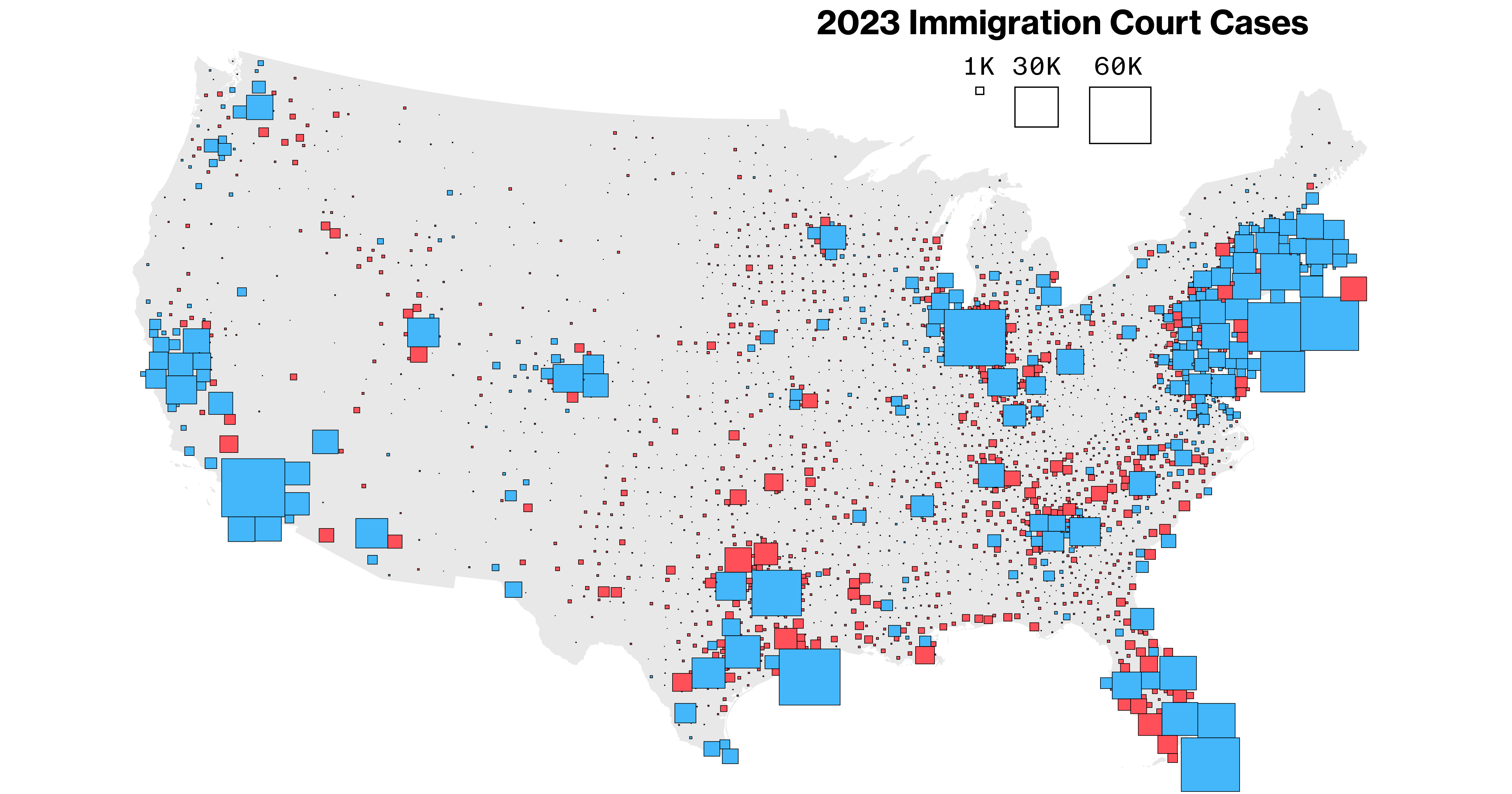

The margins were not great at all, but the dynamics of the electoral college processed them as if they were decisive. Sadly, the shifting margins suggests fears of immigration, and fears of the effects of immigration on the economy, that demand addressing in future elections to pierce through new red walls.

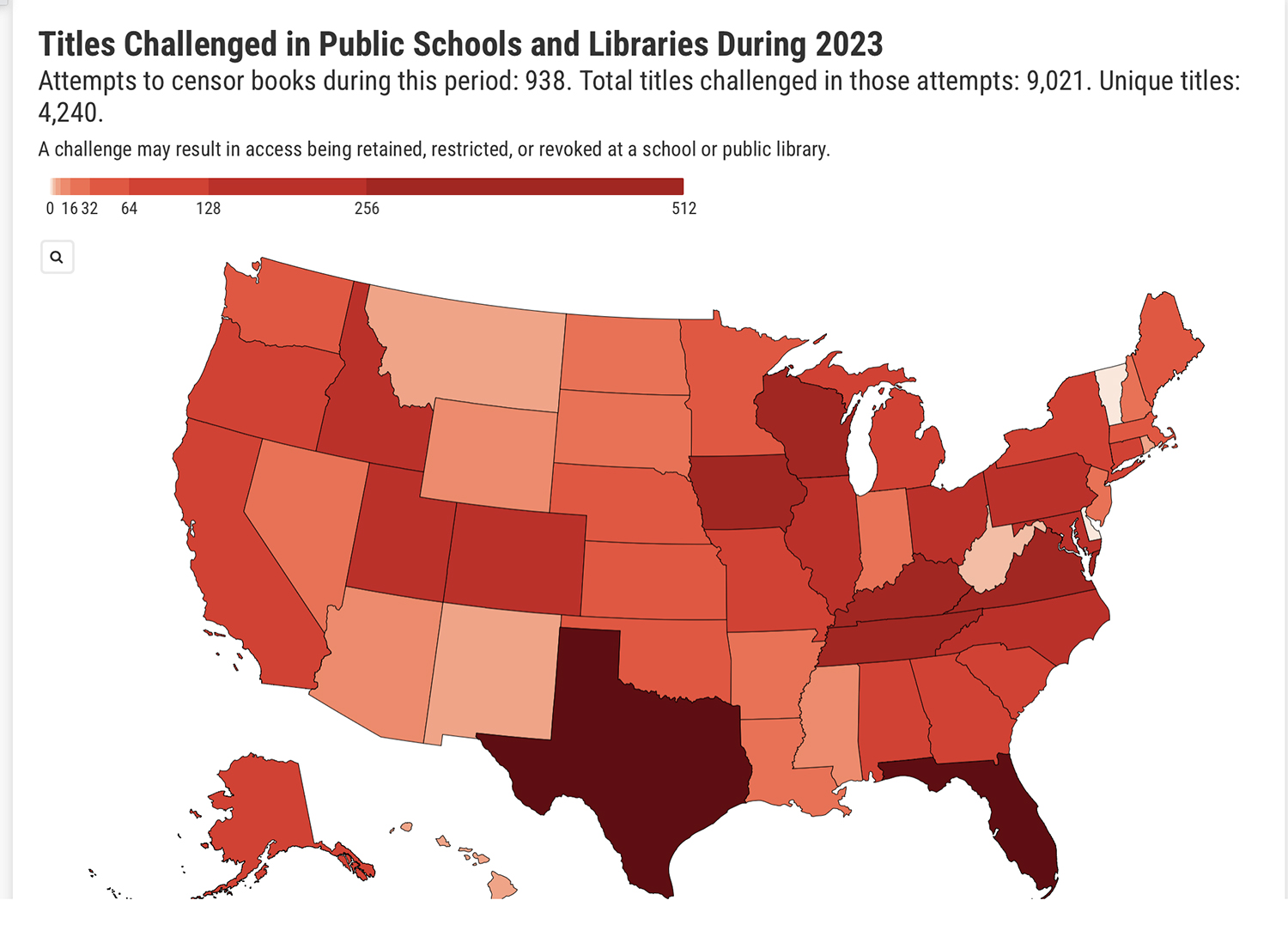

Is it any surprise that in big states like Texas, the conservative Christian movement had advocated a return to “christian values” in public schools, advocating a confusion of church and state typical of “red” states from Oklahoma to Louisiana, as book bans in public schools have been increasingly popular in many swing states–and a quite unprecedented number of efforts to ban books in public schools grew in 2022, making 2023 the “highest levels ever documented” of bans per the American Library Association, many dealing with racial or racist experiences–from To Kill A Mockingbird to The Color Purple to I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings to The Bluest Eye, as “patently offensive” or “obscene,” if not “pornography”–a charge that takes us back to the James Joyce’s great modernist epic, Ulysses–even suing individual teachers a minimum of $10,000, per individual per book, from their own personal finances. The vindictive map of banned books on race made Harris’ race a salient issue in the Presidential race, even if she never articulated it, in many states where bans existed or titles were challenged: indeed if 2023 brought a new threshold in banning books, only in five states–Vermont, California, Massachusetts, and Maryland– were no bills proposed to ban teaching social justice issues in schools in 2023.

The political advert photoshopping Trump’s and Vances’ heads as grinning southern rubes ready for a pleasure ride on rural roads in overalls was an eery nod to one of the earliest whitewashigns of southern mythologies in an upbeat version of racist past, but as theater–not as discrimination or a part of American life. Race, while not an. explicit part of this Presidential campaign, was implicit in attacking “radical infiltration” into the curriculum. If Harris was looking to Chisholm’s campaign as a model, Trump painted Harris as an extremist challenge to patriotism and economic risk, invoked her racial identity as a challenge the orthodoxy of the American social order, and implicitly rejecting school curricula considering slavery central to American identity.

Reactionary elements of racist groups in the United States were unleashed in the Republican Party from the recent backlash to Barack Obama’s presidency, helping to flip control of the House to their party in Obama’s Presidency in 2011, the reminder that Harris’ candidacy posed to using government revenues for health care, and “states’ rights” to nullify federal law on voting protections and restoring voting requirements–echoed in feeding groundless charges illegal voting aided Trump’s opponents, from Hillary Clinton to Joe Biden to Kamala Harris. When Obama endorsed Harris, twenty years after he gave his first speech at the Democratic National Convention, drawing strong similarities between their political aspirations and ideals, the contrast he drew between both and Trump drew a through-line for the world to see, but must have terrified others more than we know. We fear Harris failed to net the demographics Democrats felt were their old constitutencies, workers, or middle class women, but these demographics offer all too easy “straw men” in relation to a failure to appreciate the intense outreach the internet gave conservative values, and the myths that transcended even the best electoral ground game.

If promises of ending taxes on tips and on overtime were the bait, but what about rolling back taxes on the wealthiest Americans, ending social security and Medicare, as well as Obamacare and ending tax policies aimed at combatting climate change? These issues somehow fell to the side, poorly articulated or less evident as being at stakes in the electoral game. We stood paralyzed, after the election, suspended before the colors of the electoral map in ways that had haunted Color theorist Johann Wolfgang Goethe thought it important to indicate the symbolical register of colors in the nineteenth century–if “pure red were assumed to designate majesty, there can be no doubt that this would be admitted to be a just and expressive symbol”–despite consciousness the allegorical implications were far “more of accident and caprice, inasmuch as the meaning of the sign must be first communicated to us before we know what it is to signify.”

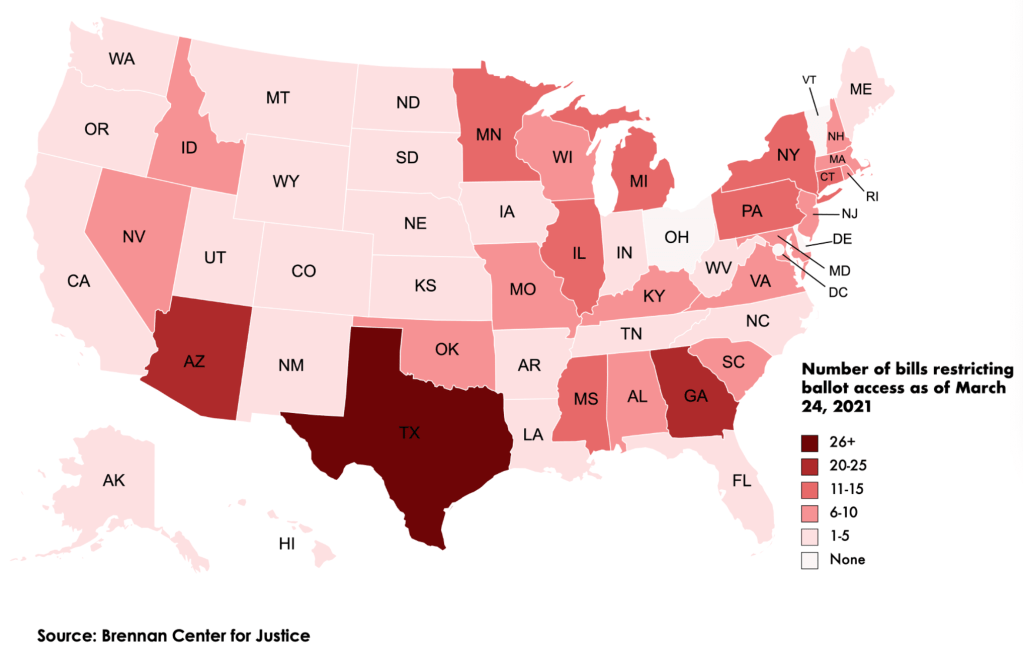

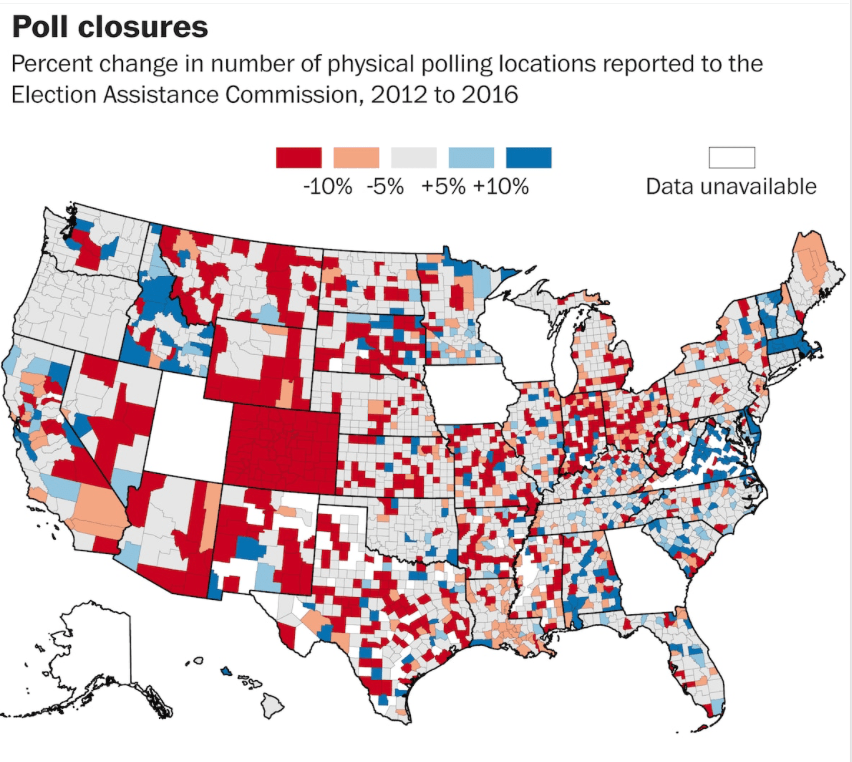

The colors charting electoral gains have in past decades registered the intensity of partisan divides. The 2024 map was more than a partisan divide. Whether we can keep polling places as welcoming, many polling locations were closed in the past two decades. And our political trust stagnates in a time of intense polarization as a consequence. The increased closure of polling places may be roughly bipartisan, but have distanced folks from the ballot box in startling ways, both metaphorically, figuratively, and literally across America,–

Polling Place Closures, 2012-2016, Washington Post based on Election Administration and Voting Surveys

–even as mail ballot applications are ready to be challenged, and ballots with different or questionably different signatures from drivers’ licenses put on hold to be “cured” or destroyed. Is there a real worry about democracy’s preservation, with closure of 866 individual polling stations since 2016, when Shelby County v. Holder opened a surge of voting changes across southern states?

Increase in Poll Closures since 2016/Leadership Conference on Civic and Public Rights

It is striking that a deeper, eery undercurrent of closing polling locations handicapped voters’ access to polls nationwide, long before the Supreme Court decision ended DOJ oversight over election policy in southern states. That didn’t seem so clearly related to Harris’ loss of sixteen electoral votes in Georgia by 120,000 votes (out of 5.24 million), or the large margins Trump won in the southern half of the state, or the 150,000 margin in Nevada, probably picking up eleven more. But Michigan was also a loss of less than 100,000 votes, and, with Ohio, was a state where physical access to the polls expanded in decisive ways, bound to have deep implications for any election. Indeed, the restriction of the vote by such barriers as Voter ID laws, overly restrictive or complex registration laws, or the curtailing of the hours that the polls are open or voter purges from public records of “inactive” voters who had not cast a ballot from 2016–that fateful year–led to the tacit disenfranchisement that the national government has failed to rectify.

Election Day has become less a time for tallying consensus, it almost seems, but as posing “a unique public safety challenge for law enforcement” that involves “keeping voters, election officials, and the public safe while also maintaining a welcoming environment for all voters.” If election workers are facing credible threats across the United States–and the FBI already warned widely of “election-related violence” as it has increased safety measures across the nation demanding boosted safety measures in fears of a growing waves of “attacks on American democracy,” the Dept. of Justice has warned, after two attempts on the life of Donald Trump, about “physical violence against election workers and infrastructure” led to prosecution of about four hundred cases targeting public servants–including death threats against election workers in Phoenix, long ahead of the tallying of votes in Maricopa County. Right-wing groups boasted on Telegram about their readiness to defend the nation, such as it is, do dispute the tallies and legality of votes in Democratic areas, using the logos of militias to recruit poll watchers on social media, seeing to question the election’s credibility by querying “election integrity”–in the increasingly real so-called “battleground states” of Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Michigan. Did folks avoid the ballot box as panic spreads about voting, once a rather peaceful exercise? Were the interruptions of bomb threats in these swing states able to shift the margins of the vote?

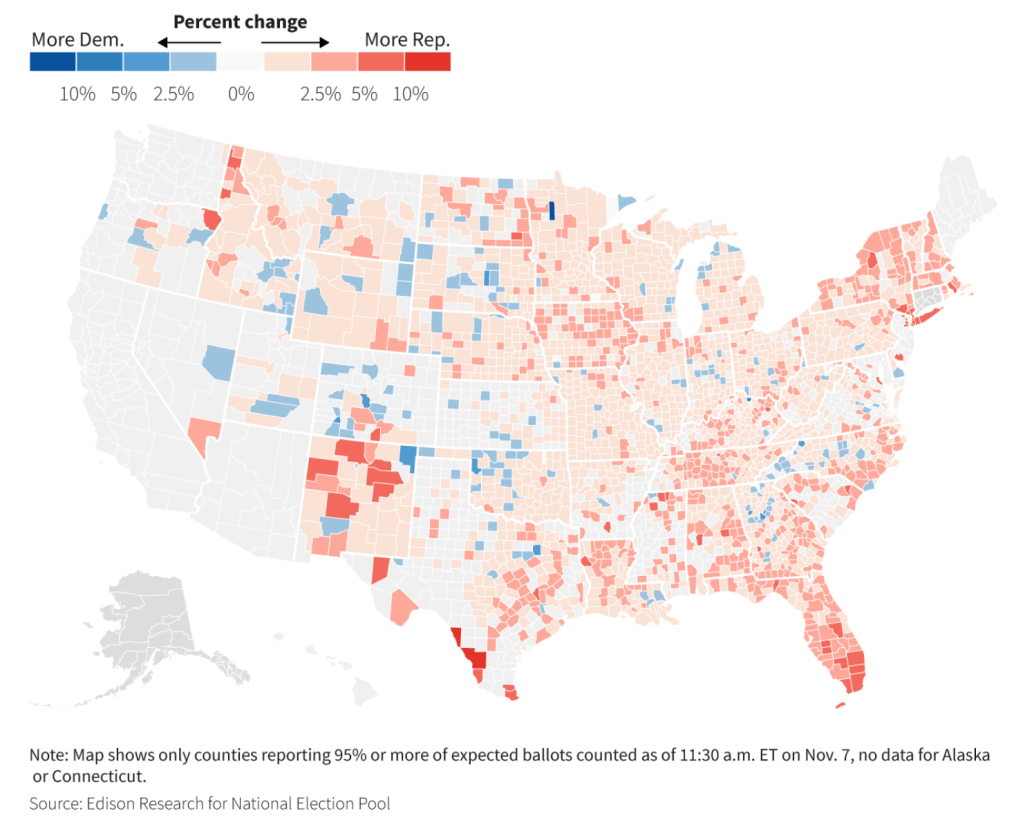

Donald Trump did not get the massive sort of margin of victory this time round to claim a mandate that was definitively calling for a game-changing strategy, or even a rethinking of government. The Democratic victories in many seats of the House suggest that the support for the party remains. But the Harris campaign, and the issues that it raised, failed to connect led to recriminations, especially in the media, has become the favorite introspection of tormented self-hatred granted license was a common come-down after the euphoria of earlier months. The pastime of interrogating how we ever got here didn’t question if news platforms had done the nation justice presenting questions that were truly at stake–despite a last minute end-run by the New York Times probably only read by those voting for Harris. The race to the right the graphic ominously charted didn’t ‘t suggest how little time most media had followed issues, perhaps fathoming the fears of extending abortion rights to discussing the gender gap that reared its head in the success of Trump’s ability to meet a male demographic by boosting male turn out–especially in black and latino men.

There was talk that Harris had somehow neglected these demographic constituencies; the issues that had continued to motivate voters–Gaza; war; real wages; the economy; jobs–dwarfed truly global issues, as the environment, climate change, environmental safety, voting rights, and seem to have put actual issues from Medicare and Social Security and health care to the side. Many seem to have lost sight, in the sense of deep economic dissatisfaction, of increasingly intolerable levels of wealth inequality were tied to deep fears of disenfranchisement and distance from the federal government. The issues of note were that the sources of policy wonk Robert Reich had been observing rather incredulously back in 2016 that “Trump is . . . channeling the fears and resentments of the white working class into hatefulness and violence,” even if the working class was underrepresented in Trump voters of eight years ago, the “fears and resentments” have become amply present among the wealthier, and the resentments may well be to paying taxes. But resentment among the lower middle classes or middle classes is unproductive to peg to a class, and indeed is distracting from the immensity of the constituency lifting all those upwardly tilting red arrows across the land. If support among non-white voters and women did grow from 2020 to 2024, substantially less support for Trump came from voters one could call lower-income in the last election.

Rising Support for Donald Trump from Upper-Income Voters, per Edson Research Exit Polls

We haven’t seen the full numbers, but are worried that voter participation substantially declined for reasons we cannot as of yet drill down. One reason seems to have been boredom or apathy. With Trump winning what seems exactly 50%–not even a real majority of votes–the decisive nature of the shift may be visually exaggerated by the above aggregation. Perhaps access to polling had indeed contracted, with poll closures and the restrictions to legal access to the ballot, as zombie specters of dead voters, illegal immigrant voters, and convicted voters were painted as threats to the Republic. We heard less of restrictions on ballot access that may have existed–more about the poll watchers vigilante groups like the Proud Boys were prepared to provide may have intimidated voters–and less about the restrictions of ballot access and the distance from convictions that a vote would have an impact in the national government’s direction and role in one’s life.

We heard far less about why many formerly Democratic voters may have left the party, this time round, not necessarily abandoning it but having a hard time stomaching a woman who was foregrounding of abortion rights as a call to arms. Did the restrictions and difficulties inform, or must they be taken account into, any reading that we can offer about the seemingly generalized rightward shift in Pennsylvania, Georgia, or Nevada? Or did the shift toward more Republican voters from Montana the the Dakotas to New Mexico–where Harris only narrowly won by 50,000 to New Hampshire, where she won by but 23,000 votes–not a small shift from the Democratic Party?

This was surely the case in Long Island and New Jersey, where she won decisively by 220,000 votes. To be sure, Latino votes went for Trump by large margins in New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas and Florida–but this was not because Harris stopped affirming working class issues. Was this registering a sudden change, or a deep rebound, a rejection of values Kamala Harris championed?

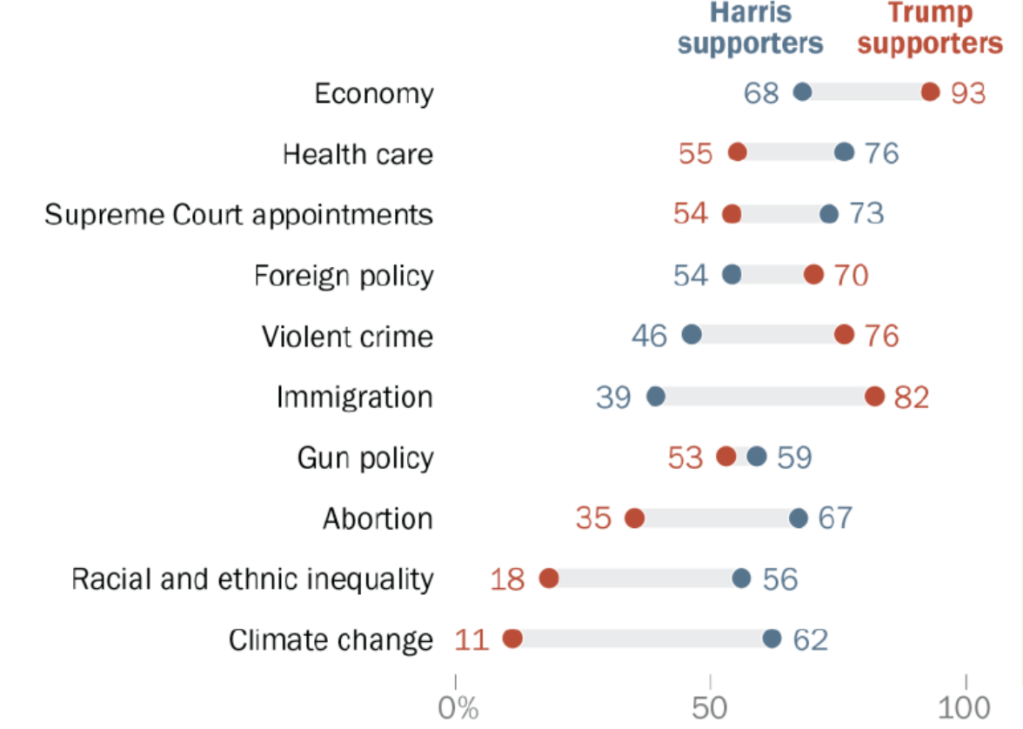

To be sure, the political “issues” were less issues, than alternate perspectives on reality–which perhaps made the election quite unique, and a sign of a polarization not lying only in party registration, but a split in “issues moving your vote” in different perceptions of the nation and indeed the senses of what government–and what a President–might due: the actual ways that government exists in our lives, now including health care, is viewed through a terrifyingly distorted (and distorting) partisan lens.

How Percentages of Registered Voters Supporting Candidates Identify Important Issues/Pew, Sept. ’24

We are so invested in different realities, indeed, it did seem surprising that the very questions of voter access to polls that was so important as it contracted in earlier years was something that we seem now to accept as part of our political landscape–less ready to raise questions of the discarding of ballots and the distances required to polling locations than in the past as we were confident to win a race on the issues, and that the candidate we had identified seemed so competent to compete. Were these even issues that divided the electorate? Our friends at the American Civil Liberties Union have revealed that immigration and public safety were indeed big issues for the electorate in the 2024 Presidential election, but the hard policies both candidates advocated in the home stretch were no longer what voters were looking for in Arizona, California, New Jersey, New York and Ohio–where the study was based--or in Georgia, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, congressional battleground states that they polled. Voters were looking for balanced messaging, more than promises of “toughness” and hoping humane borders preserved immigrant rights–hoping to address the root causes of immigration. not building detention centers, increasing prison sentences or building jails.

The illusion of an intense partisan divisions was in a sense projected onto maps by the commentariat, who appeared delighted with the possibility that our democracy was paralyzed by the possibility of a gridlocked electoral college–what seemed a mathematical possibility. Political overload and general fears led us to spin ink about partisan divides, anticipating the electoral college as the problem that would be rearing its head on Election Day from a distance, the disastrous maps of massive disenfranchisement that might emerge from what seems this year’s round of a roll of the dice, involving so many moving pieces it is hardly able to be seen as a dance.

CNN, August 23, 2024

These divided scenarios were pure conjecture, but the possible projections of dissensus seem in the grain of the hair’s breadth margin of error margins of each candidate in the current election, a result that was forebodingly augured, as if right on cue, by the first tally reported votes in the 2024 election, up at the local redoubt of Dixville Notch, NH where the polls open at midnight, and the first results are drawn on a whiteboard for public view. The six votes for President split evenly, a patriotic result worthy of a rendition of the Star Spangled Banner on a stars’n’stripes accordion to accompany the unveiling of the votes’ tabulation on a white board written in red, white and blue.

The riff on the accordion seemed to introduce the divided electorate of America, split perfectly in two. As the six votes of the apparently white electorate of Dixville, NH split evenly, with no victor, the narrow margins of polls seemed to be confirmed, if we needed confirmation, even if the real divides that partisan polarization have been argued to map may lie, no surprise here, in gender. But if the Dixville votes were close, even if early voting surpassed 2016 and 2012, as votes for the Democrats seemed lower in many of the very swing states Biden had won by the very slimmest of slim margins, often of less than a percentage point (Georgia, Arizona, and Wisconsin),–and often often by less than twenty thousand votes–

Biden’s margin of Victory in Five Swing States, 2020

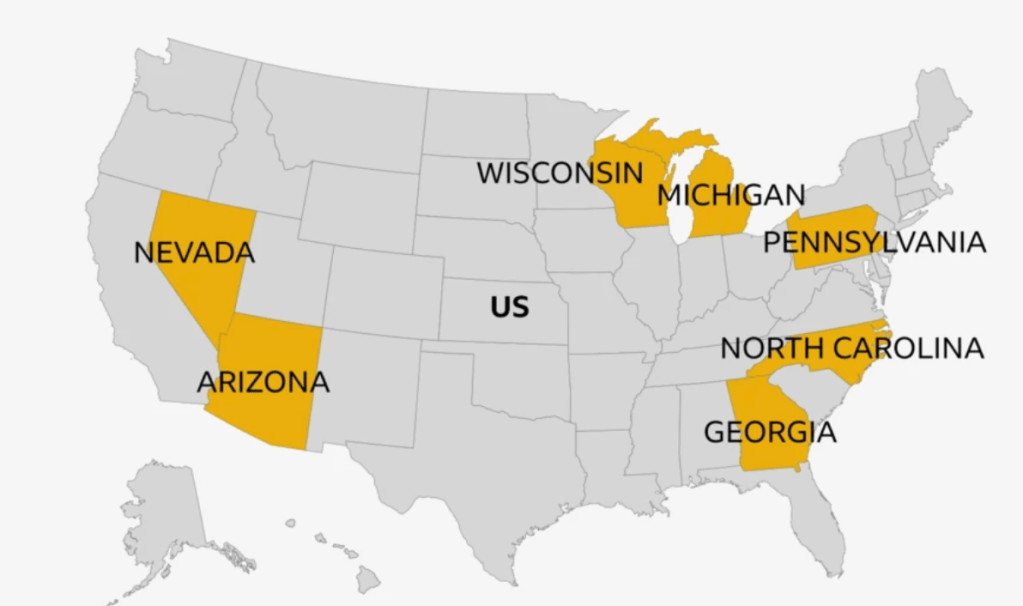

The margins were far from the old blue river of states that ran across the Mississippi–Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, Arizona, Tennessee, Louisiana–a constellation that has long eluded Democrats since two southerners, Bill Clinton and Al Gore, ran in 1996. The swing states are often mapped as if custodians of democracy–the new swing states were far from the Mississippi, but were tagged as the predictors of the 2024 election in whom real confidence for the future was vested.

The new geography of ‘swing states,’ the focal points of the electoral map, were by 2024 mapped as the electoral gold that defined, or would defined, the currency of this Presidential election, as if these seven states alone had replaced the United States as the basis for deciding the election–a master myth of 2024 that, as it turned out, was hardly the case–but was of determining value.

If the loos of all seven swing states by Democrats was a disaster of the election that magnified the sense of Trump’s new margin, the states’ votes were the master myth of 2024. It is no accident that the mythic status of “swing states” held in the 2024 election was bequeathed by the narrow margins of 2020, but promoted by our pollsters in ways we accepted, even if it was inflated by the metrics they used to massage the results. That said, there were deep worries about the “swing states” as they failed to line up with anything resembling advantage to Democratic Party candidates, as the fall set in and chilly winds streamed across the nation as Election Day approached. This was not supposed to happen–if the divides at times always seemed close to or within a margin of error.

Trump Pulls Ahead in Battleground States Katharina Bucholz/Statista

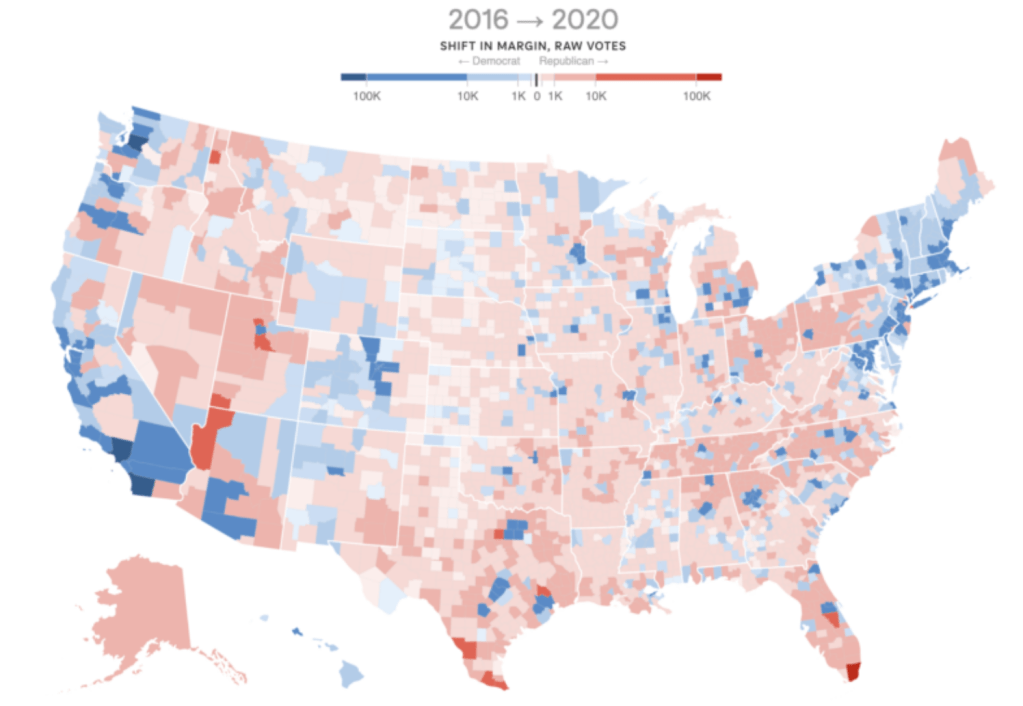

But the uphill nature of the battle was foregrounded by the shift in the votes in swing state battlegrounds, as it were, with a clear redder shift of not the metropoles of the states said to swing the pendulum and decide the future President, as Nevada, much of Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Michigan had already shifted in 2020 to vote for the very same Republican candidate, and parts of Arizona shifted for the orange haired Republican in considerable numbers, in ways that made the ground game hard to know how to organize effectively, difficult not to see as challenging battlegrounds. Part of the shock of the first election that had surprisingly sent Trump to the Oval Office was the deep shift in the very same swing states that had swung suddenly Republican–red–as the counties of the “blue wall” shifted rather alarmingly, and northern Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Nevada shifted Republican by a fifth or over from the previous election!

Voter Study Group/Griffin Texiera/Partisan Margins of 2016 Presidential Election

The next time, the swing states had served to shift the red tide, and we hoped that this would hold sold, and not only Mitt Romney’s Utah would be a pocket of dense blue even brighter than Massachusetts. as a true North Star. As Texas counties held blue, 2020 had firmed up the Democrats in the northeast, along the Eastern seaboard, and in the northwest, offered a new geography of the cartographic containment of that deep red specter of the nation’s central states.

Shift in Voters from 2016 to 2020, Based on Final Certified Election Results by Associated Press (Connie Hanzhang Jin and Daniel Wood/NPR)

Perhaps the partisan divides between red and blue have come to depict as a sort of unraveling of American unity, and of the banner of the Stars and Stripes, despite the trust that each Election Day hopes to somehow renew in the ritual of casting votes, even for an increasingly paralyzed Congress.

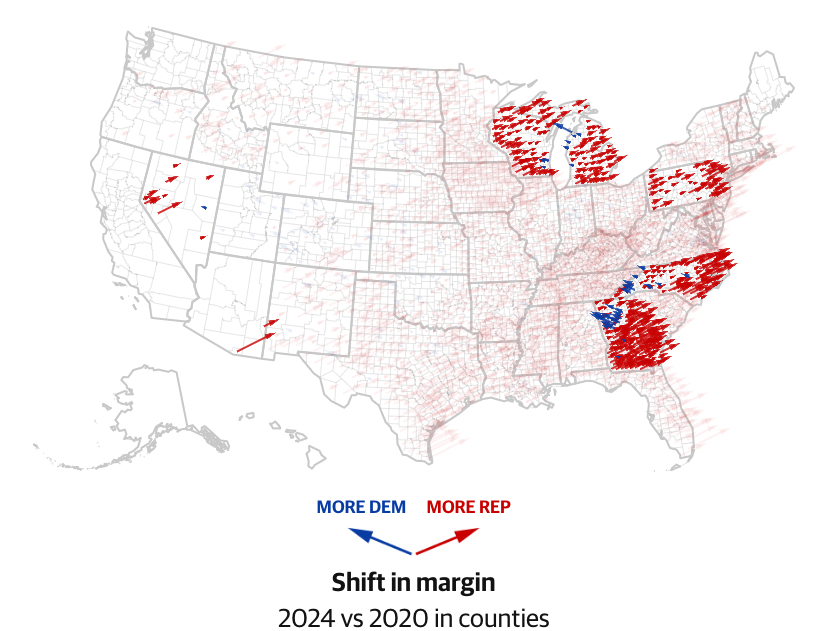

But the battles of battleground states split red, big time. The leap to the Republican Party was pretty large in Wisconsin and Michigan, particularly outside of the cities, which show small burst of blue arrows, very much against the grain of the nation, and the density of the red shift in North Carolina and Georgia and Pennsylvania seem as if they would run against the clear knowledge that the victor of the election would win in “swing” states on whom the pendulum of the election seemed to rest. They swung right, and big time in the case of many districts.

Shift in the Margins of Republican and Democratic Voters per County in Swing States, 2020-2024

In an eery reflection of the targeting of swing states with on-the-ground campaign offices by Harris and the Democrats, the airwaves of social media echoed on election day with a slew of false rumors that seemed to target swing states that bet on the short attention spans of most Americans. Rumors, quickly discredited but with some traction, grew that the Get Out the Vote efforts who had driven some voters to the polls in swing states like Pennsylvania, Georgia and Arizona had indeed prompted party officials to flout the law by colluding with prison officials in each state to bus prisoners to the polls in each state, in search of their precious electoral votes.

The shift to the right continued, despite the similar tactics of the ground game to that used against Trump in 2016. Harris intentionally ran a campaign different from that of Hillary Clinton, but the ground game that “her” campaign inherited and ran followed Hillary Clinton in only this respect: it was based on filling the field of these “battlegrounds” with campaign offices–opening a massive three hundred and fifty eight field offices with 2,500 workers in these battleground states, and knocking on some three million doors of likely Democratic voters to appeal to their political issues.

The electoral map became the basis for an intense ground game that was increasingly waged with passion, intensity, and passionate intensity–but the campaign of campaign offices was dangerously out of date, especially before the immersive reality of many Trump voters, that were ready to see Harris as an existential threat for have “allowed dangerous criminals in” and left Trump in the inherently paradoxical position of “saving religion in this country.” (It was unsaid most of those immigrants tagged as “illegals” were raised as Catholics.).

The “ground game” for the election, even as most consumed their “news” online in Facebook feeds, or from “news” outlets that were surrogates for the Republican Party, was understood by a slew of expensive campaign offices, and actual territory, far into a rural hinterland, seeking to make what were often quite hostile ground into site ready to hear about the Democratic Presidential candidate. And if I had first heard the term “swing state” in 2008, as it was used in San Francisco by a worker for Lawrence Lessig as the key to how California might delivery victory to Barack Obama, the increasingly dismal view most Americans had of politics weakened the mantra of “hope.” The eleven swing states of 2016, when Hillary Clinton faced off with Trump, emerged out of the strength which which Obama had pursued and proven the case where the disaster of 2000 in Florida could be tactically overcome by “the greatest ground game . . . ever put together” across eight states–Virginia, Ohio, Florida, Missouri, North Carolina, Colorado, and Nevada–in ways that the focus on offices on the ground emulated in the Clinton campaign back in 2016 on a more expansive eleven. This was the strategy that Clinton used–if it wasn’t winning–and that the Harris office followed.

.

Dominance of Clinton Campaign Offices across North Carolina, 2016 Election

Yet this year, those swing states were less exciting places, and had contracted to six, and moved into places that the Democratic candidates had long had no problem defending–Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, places once seen as a ‘blue wall.” But the mapping of states as if they had identities able to be mapped by chromatic divides is in a sense undermined by the deep evangelical support behind Trump–and the overwhelming splits of Protestants and Catholics alike as religious groups that bucked the trends of global modernity big time. It was hard to see the map outside of the red state versus blue state optic, but the swing states became parsed with an unheard intensity, outside of a lens of ideological or political debates.

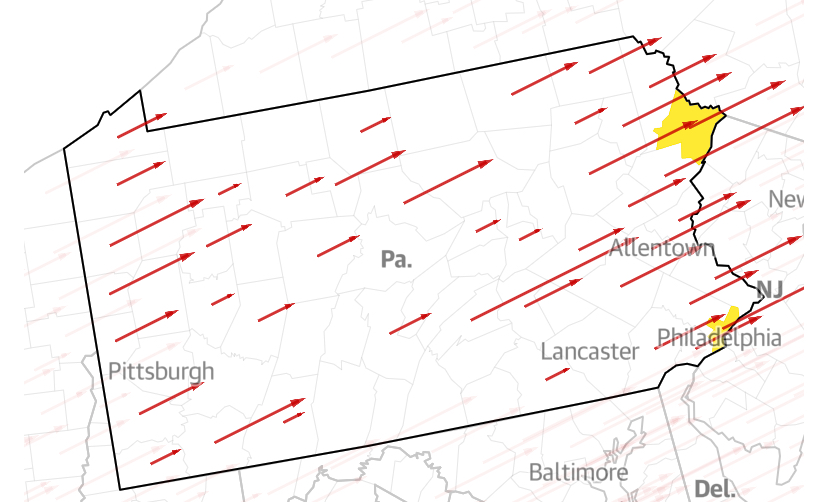

If Joe Biden’s campaign had already set its footprint in the Keystone State with twenty-four offices across the state, including in counties he lost by significant margins in 2020, refusing to cede any ground, the hope to spark grass roots movements even without a clear official ground game created a pro-active prominence statewide, on which Harris only capitalized, that contrasted with Trump’s personal predilection for visits to arenas–the attempted assassination in Butler County proved an unexpected windfall few could predict, as Trump sported bandages of Christic significance at the Republican Convention to a standing ovation, as the bandaged wounded ear grazed or hit by a bullet offered an insidious meme and boosted his turnout in Butler country beyond expectations–and one of the largest shifts to the Republican support among Pennsylvania counties–garnering over two times as many votes in what had not earlier emerged as a Republican-trending county.

By early September, Harris had effectively doubled the number of offices on the ground across Pennsylvania, which now dwarfed the presence of the Trump campaign by Labor Day weekend, running a ground game that seemed bravely bent on refusing to cede terrain–even opening sixteen in deep red rural counties that Trump had previously won by double digits. The hope to “crack” the Trump dominance aimed to push beyond the slim victory that Trump won against Hilary Clinton, and cement a lead greater than the razor margin of Joe Biden’s victory.

But what was imagined and strategized as being an extremely close race to the wire was almost a landslide, as Pennsylvania went for Trump in far greater proportions outside metro areas. The margin of voters by which Trump won was less than 140,000–a sizable difference, to be sure, but raising some tantalizing questions about the intensity of all those GOTV movements, and especially what it would look like if Joe Biden spent more time pounding the streets of scrappy Scranton, which he visited for a small gatherings three days before the general election, when he visited labor leaders and local politicians for two days, hoping to close out a Harris victory. The margin might have shifted in Philadelphia alone, where 703,000 of the city’s 1.12 million registered voters turned up at the polls, or voted absentee, almost 50,000 fewer than 2020, and a 63% turnout led to Harris receiving just under 60,000 fewer votes in the city than Biden-Harris did in 2020 when 66% of registered voters made it to the polls to cast their ballots. And if the Democratic Party boss, Bob Brady, was conscious that it would htake a margin of 500,000 votes in Philadelphia to win, her margin of victory of 412,000–almost 60,000 short of Biden’s large 2020 margin of 471,000, make one wonder why the city so significant to a Democratic success wasn’t targeted for GOTV rallies, even if she closed out the campaign with a massive stop in the city the eve of election night, with Lady Gaga, will.i.am, and Oprah Winfrey, last visiting the city a week earlier with Barack Obama. The problem of turnout didn’t equate with star power, we’ve been assured, but might rallies of more intensity peeled off more turnout or votes?

And even in the states around Butler county, in the deep west of the state, the shifts of analytics in the vote compared to 2020 showed a big jump

Thank you for your efforts to “map” what just happened to America. I have avoided the news since Tuesday evening when I realized what was about to occur. I hope once the dust settles a bit more you have an opportunity to have a followup that portrays the landscape in your unique and compelling fashion.

(‘Acaqun ehicine’) ‘Go in a good way’ as say the Cahuilla Indians.