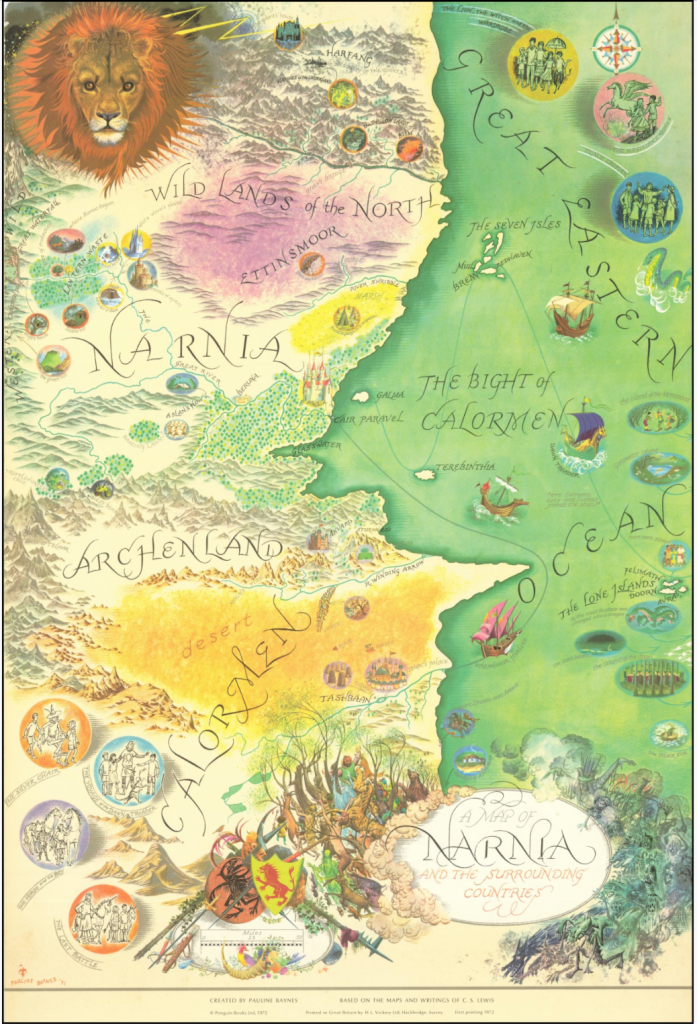

18. The collaboration between Lewis and Baynes was apparently never stable. Perhaps some blame comes from Lewis himself–who seems so flustered before Baynes’ presence in person, distracted by her looks and demeanor as if to be tempted by sin, maintaining limiting their interaction written correspondence, curtailing personal interactions. For Lewis strikingly encouraged their contact and correspondence exited in maps, never expanding the expressive nature of images he blamed all too readily on Baynes’ artistic abilities, in a donnish fashion. . Baynes’ first fantasy collaborator J.R.R. Tolkien was keen to note that “Hobbiton is on the same longitude as Oxford,” Lewis, who had of course primarily exercised his chops of allegory as a science fiction writer, was keen to map an other-worldly sense of Narnia, and to translate its topography to a sense of the palpable polarities of good and evil in a geography many readers have spent time navigating. Lewis presented Baynes with a map he had drawn of Narnia by hand, to be sure, when he met her at his publisher’s New Year’s Day, 1951, but the green cross-hatchings around Cair Paravel, he delighted in her skills of “fantastic-satiric illustration,” “if only you cd.take 6 months off and devote them to anatomy,” ten months later, patronizingly told her, “You have Lenard something about animals in the last few months: where did you do it.” Was he undervaluing her skill, even inviting his publisher take her for the afternoon to the London zoo to examine quadrupeds as he despaired her rending of animals, reserving praise for her “exquisite delicacy” of her line but admitting to have “always had serious reservations” about illustrations of which he was “not enamoured” beyond a skill at the “formal-fantastic level”–even a bit angry at the proficiency she added to Tolkien’s work? He devalued just how much she had improved his map, in harping on the inadequacy of her renderings animals.

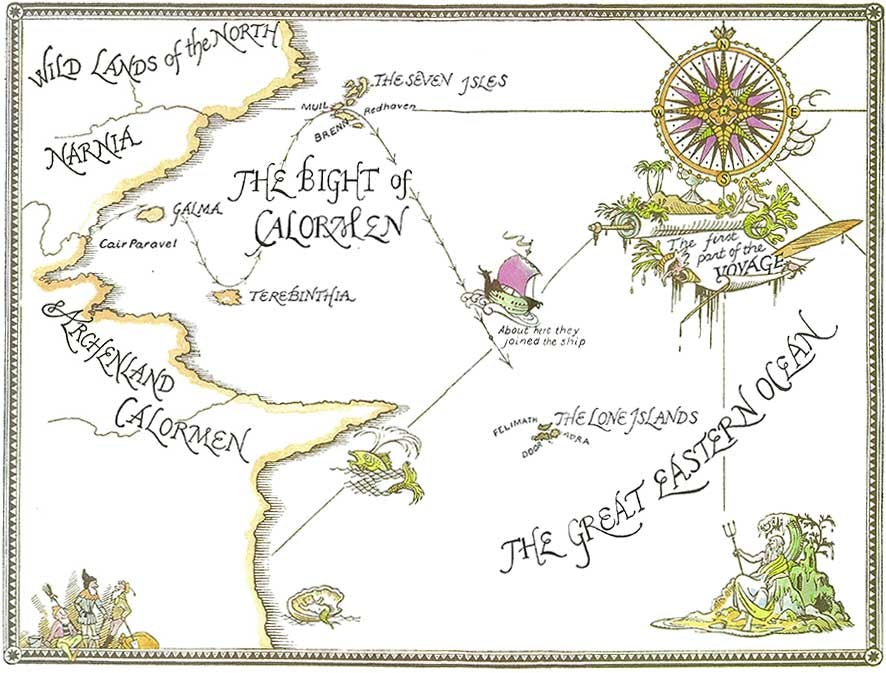

The map that Lewis did provide and that she would add to Prince Caspian and later expand as a broader canvas was itself rather comprehensive, as if he wanted to control the final result:

Ms. Eng. lett. c. 220/1, fol. 160r/Bodleian, c C. S .Lewis Ltd.

A distinctlydonnish taste for over-correction may have helped to conceal deep appreciation beneath his critiques of her many draft illustrations–he had trouble defending her images to his friend Dorothy Sayers’ disapproval, as if the “the main trouble about Pauline B. is . . . her total ignorance of animal anatomy.” He weighed his doubts about her skills with her economic need (“old mother to support, I think“), and returning to her “lovely” botanical drawings, despite her apparent lack of interest in “how boats are rowed.” He defended her after Sayers cattily disparaged her illustrations of Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as “‘effeminate’ . . . because it is boneless and shallow,” as if they might effectively undercutt Lewis’ aims for allegorical profundity. (Lewis defended his reluctance to confront her as she is “so good and beautiful and sensitive,” but if he was taken by her looks, if not distracted by them, she offered increasingly satisfactory images of Aslan; he must have loved the maps she provided for his books even if he agreed with Sayers that “the faces of her children [are indeed rather] empty, expressionless, and too often alike” and that while she never seems to have executed the image he imagined of a heroic Aslan “gazing at the moon,” she seems invested increasing majesty with which she depicted Aslan, his true hero. Was it not also true Lewis was not that able to invest his child hero’s and heroines with much substance?

Lewis did draw a range of preparatory maps for his own manuscripts, probably as guidelines for Baynes, including Ciar Paravel, where Lucy, Edmund, Peter, and Susan, “Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve,” will reign as Kings and Queens, Aslan’s How, where the lion is sacrificed on a the Stone Table, the Narnian town of Beruna, and Miraz’s Castle, among other points of reference, which he must have provided to his illustrator,–and leaving an intentional blank space where future action in the series would occur, where “we must not put in anything inconsistent”–he was most didactic about the situation of the “major woods” he colored Green, and chief sites and the elevation of Aslan’s How–that secret site which lies on “a path the others cannot, or will not, see,” lying above the green plains of Narnia.

–more than create a land that the reader occupies. If this original roughly drawn map clearly informed her work, it allows us to see how she added to its credibility in particularly deft ways that Lewis perhaps never noticed or acknowledged adequately, even if Baynes clearly did. The early preparatory map now among Lewis’ papers in the Bodleian Library is notably lacking in much maritime detail of the sea, even if it provides the needed signposts–and includes the Lantern Waste where the Lantern of Ever Lighted Lamp in which the first volume first enters the Narnian world.

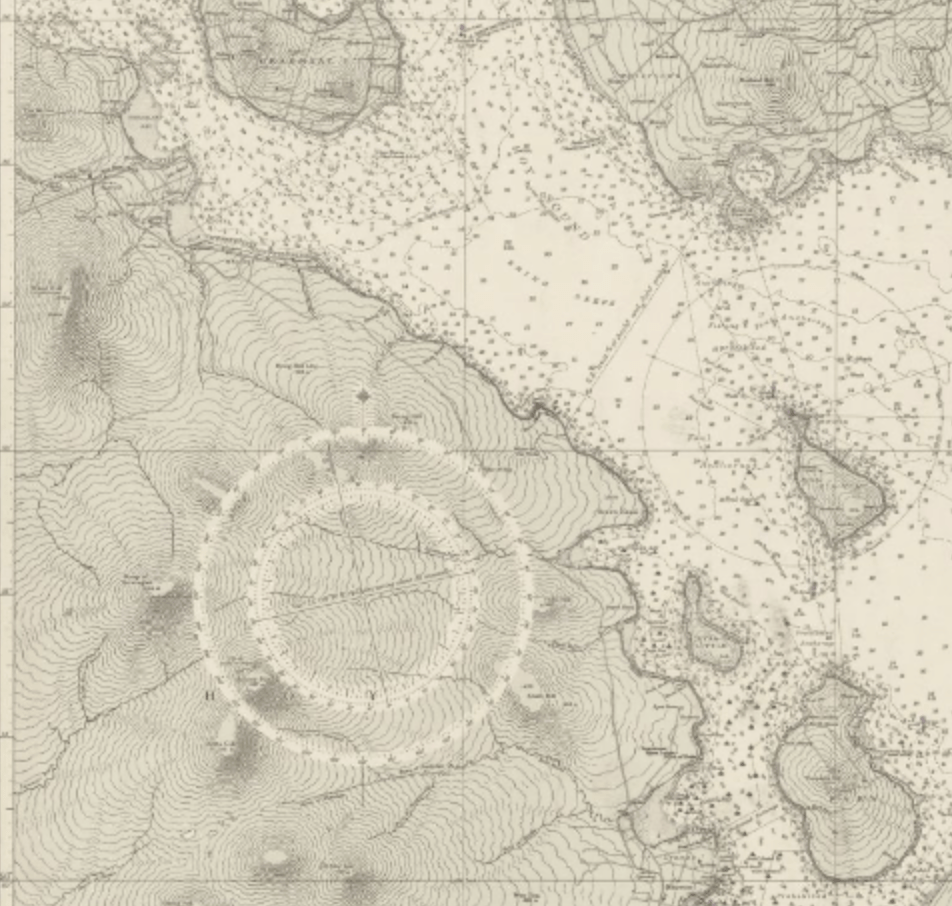

The set of maps that informatively materialized Narnia as a cartographic form was not drafted by its author in the published form that I or other readers first read. Critics have focussed on its neo-medieval style has been long thought to be decidedly informed by Pauline Baynes’ love of medieval manuscripts, and perhaps her attractiveness to Tolkien, as much as Lewis’ rather stock prose; although the value of medieval maps or Neo-Victorian childrens’ book illustration of Arthur Rackham and Gustave Doré may be cited as pronounced, but must be balanced with the marine charts that Baynes made at the Admiralty Hydrographic Department in Bath.

The description of the oceanic expanse fit the expansive views Lewis evoked, in which the “beautiful sight” opened of “the whole country below . . . in the evening light—forest and hills and valleys and, winding away like a silver snake, the lower part of the great river. And beyond all this, miles away, was the sea, and beyond the sea the sky, full of clouds which were just turning rose color with the reflection of the sunset. But just where the land of Narnia met the sea—in fact, at the mouth of the great river—there was something on a little hill, shining.” But the coastal navigations that helped invest Narnia’s world–as Middle Earth’s as well–with such plastic materiality, so that its edges help these fantastic lands pop out in our minds from the pages we read, and pop beyond their prose, reflect Bayne’s proficiency in the symbols of Admiralty charts.

While the expansive views are allowed by the open black and white maps Baynes contributed to the volumes, her contribution seemed to be recognized by Lewis when he offered to share his literary awards, if he professed public doubts about her ability to convey expressions or anatomy; but the maps she created for his book, a sort of hidden counterpart to the hydrographic charts and navy maps made ad the Admiralty in war, were a crucial counterpart to his prose, and perhaps the true artifice of her illustrations–and she did improve in drawing the visage of that majestic heroic lion!

For the drawing of compelling coastlines not only helped her to detail engaging maps for a range of coastlines for worlds that would be refuges from wars, but maps that might be considered counter-maps to the rise of geodetic military maps that gained dominance in a time of global war. Baynes’ own wartime work as a wartime model-maker led her to delight in modeling landscapes after aerial photographs for instructional purposes by quite tactile material products–“sponge (for trees), sawdust (for textured ground), and balsa wood (for buildings)”–before a hydrographic draughtsman on naval charts at Bath, which have been argued to inform the careful shorelines of the shorelines in her fantastic cartographic work of Narnia’s Eastern Ocean, and offer a vivd image of the ocean-going voyages of the Dawn Treader–a more fanciful view of sea, perhaps, but of a marine world that might be inhabited in the 1950s in the manner of the medieval maps she adored. Baynes continued to pursue work as an illustrator of children’s books–her prime gig–as she devoted herself to wartime efforts at the Hydrography Office, but techniques of rendering shores and nautical expanse were transformed with a greater sense of cartography and map coloration as an art: if the shadowy nature of Icelandic mythology may have increased the shadows of both Middle Earth and Narnia–and indeed Narnia is only the shadow of Aslan’s kingdom, as Professor Diggory Kirke put it, Baynes added far crisper edges and a line–as well as clearer coastlines–to the image of Narnia than had existed in Lewis’ allegorical text.

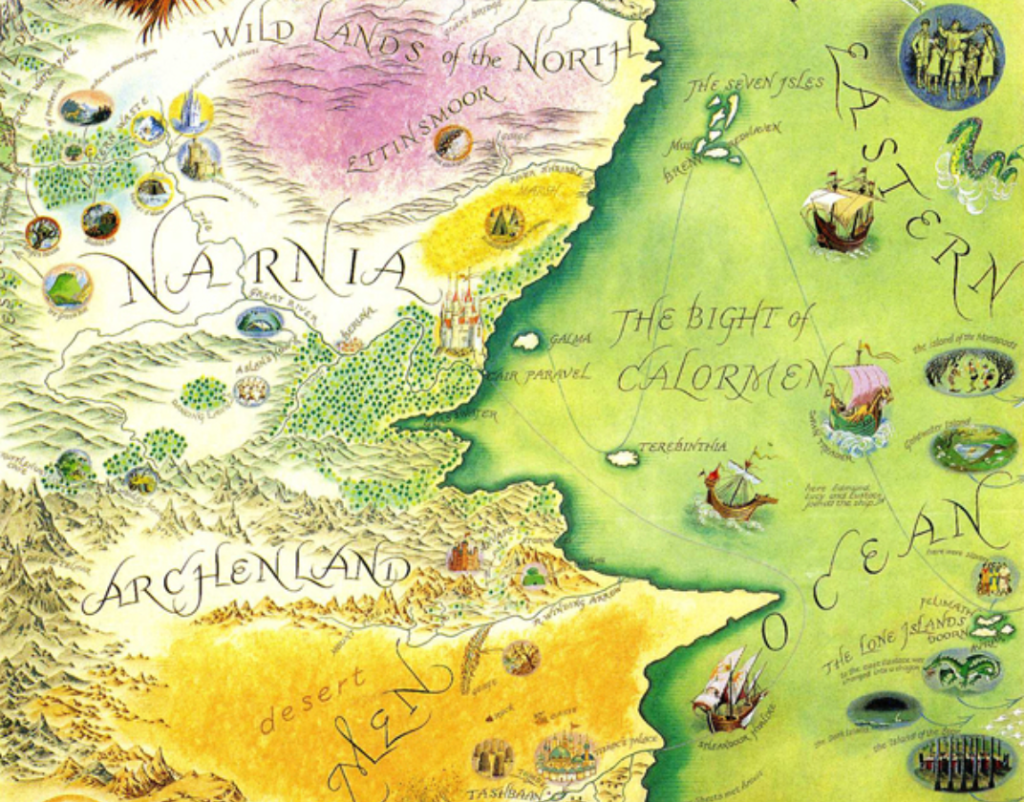

It perhaps helped to nourish some sense of the aptness of medievalisms, to be sure, that Lewis’ narrative was fairly Christocentric, even if Baynes claimed she never got that until completing the illustrations of the final books: the role that Lewis saw of reintroducing the sacred sacrifice into children’s literature after wartime–and after the ravages and destruction of war occupied most children’s minds–meshed with the Neo-medieval localism of the familiar kingdoms, but those maps also challenged readers to assemble an increasingly broad panorama in their minds, that recall the nineteenth-century fashion for expansive panorama as much as the elevated view of one town.

This was a spatiality that might move into a panoramic register after one read about the nautical travels of the ship–recalling the medieval portolan charts, to be sure, as much as a Jerusalem-centered mappamundi, buts a map that one might inhabit.

If the mistress of mapmaking designed worlds more comfortable to imagine–the afterlife of many became posters that filled college dormitory rooms in the 1970s and today–the popular cartography of Middle Earth and Narnia grew as a nostalgic materiality in the area of geodetic maps the palpability of lived landscapes adopting a memorable sensory voyage in which were always included a compass rose, and moral compass, viewed on more than an abstractly mapped terrain.

It may make sense to revisit the symbology of those Admiralty charts as a second skin that Baynes nourished, and adapted to enrich the storytelling abilities of those maps, evident in the attention to coastal shading to fill out the imaginary topography Lewis rightly wanted included as crucial parts of his books, even if the coastal features that the charts include suggested a richer semantic frame of reference than Baynes adopted for the readers of the six book set–the hexology that has itself become a standard for such boxed sets from Harry Potter to Isaac Asimov’s Foundation saga.

There was a tension, indeed, between the pictorial and the austerity of the non-representational, in the coastal charts and hydrographies of those Admiralty Charts that Baynes probably chafed at, to some extent, as expedient, but whose graphic economy of communication of coastlines has a poetics that depart from the abstract spaces maps were reconceived of in purely geodetic terms.

To the considerable delight of readers of her early work on the Narnia Chronicles, Baynes indulged the visual textures in her later expansion of the Narnian topography, almost decade after Lewis had stepped out of the picture. The canvas was not only cinematic–it predated the movies by some time–but for the centenary of Lewis’ birth, but followed on the fame of the expanse map of Middle Earth with which it clearly shares more than stylistic features–it may perhaps have offered the full sense of recognition she never had from the author, if not a way to revisit the trauma of having been so publicly dissed. The popular maps reflected the huge popularity of the series of novels in an environmentally conscious era, when the traditions of seamanship, exploration, and intrepid pilgrimages accompanied by the keen scents of animals, might be appreciated, even before they were translated into technological films. For Baynes not only met a market demand, but seems to have reclaimed the totality of the Narnian landscape by doing it full justice as a region able to be inhabited by the mind’s eye, but inhabited with a luxury of colors readers had rarely earlier had.

Pauline Baynes, A Map of Narnia and Surrounding Countries (1972)

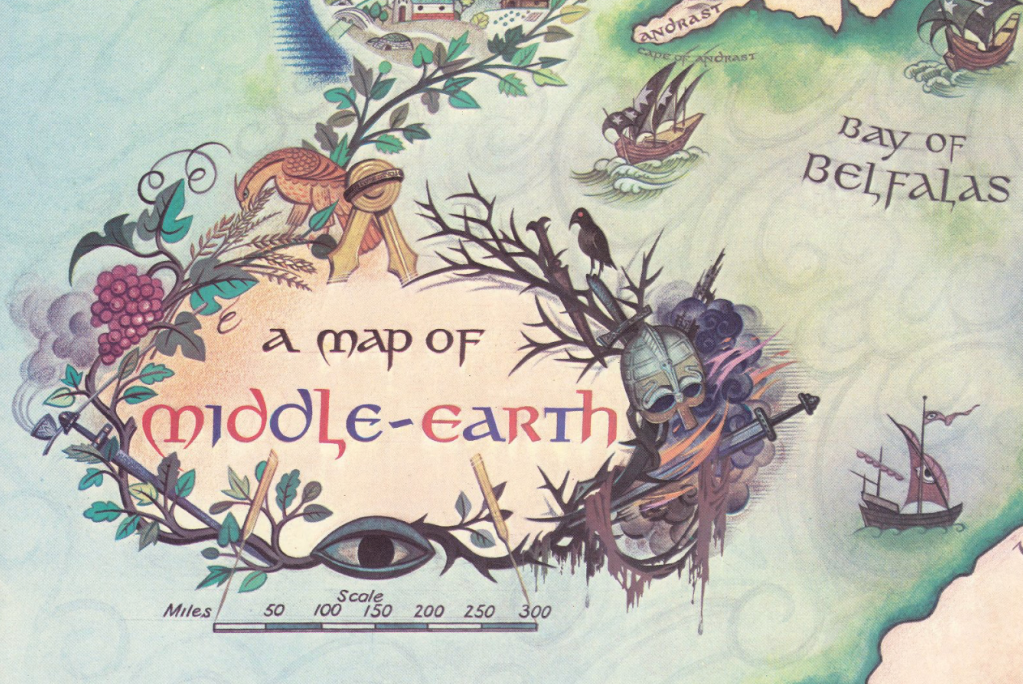

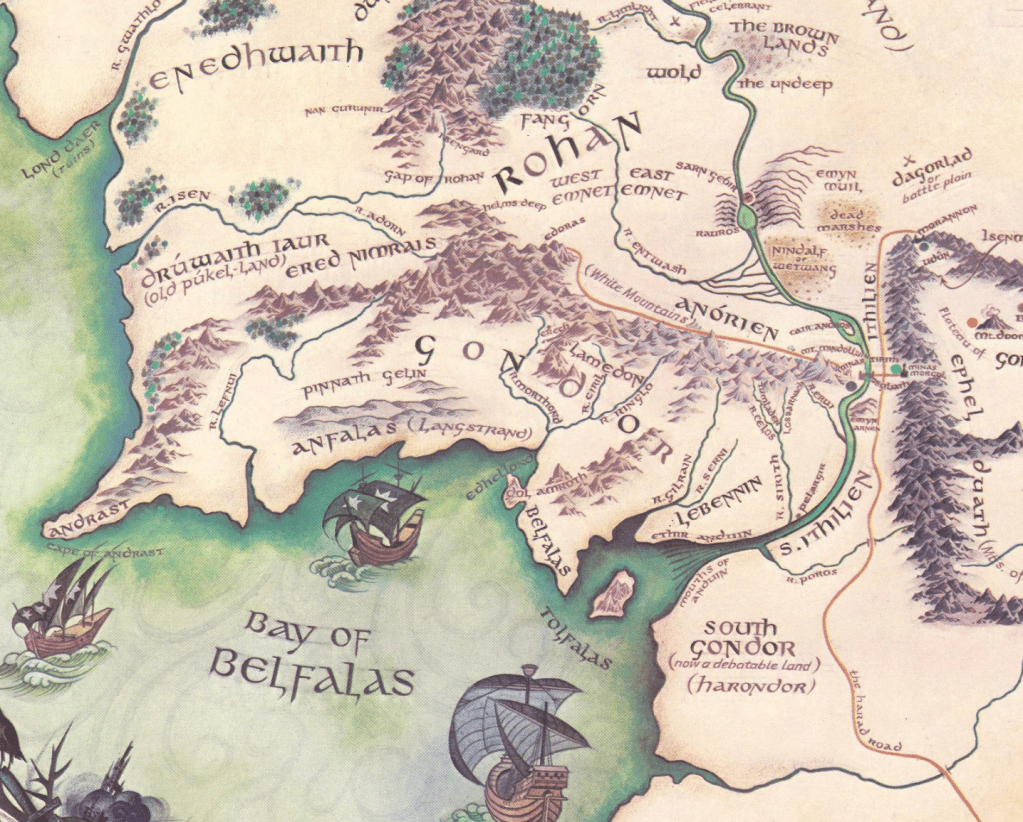

19. Did it not contribute to the majestic panoramic maps that Baynes later drew, and would return to draw, for Tolkien? Christopher Tolkien, with his father, adopted neo-medieval script recalling the Norse epics all the Inklings loved, and their study of Icelandic as a poetic vehicle to gain inklings of salvation in written work. The other-worldliness of these lands was informed by the prominence of majestic mountain ranges and neo-medieval lettering of the maps of Middle Earth, pictorial vignettes nesting among its place-names, allowing readers to follow the immersive action, and to return to the mental imaginary repeatedly–as so many did–to survey the foreign topography on their bedroom walls as a sign not of a remote past, but perhaps more of childhood worlds.

For Tolkien, to be sure, the cartography was deep in its similarity to the landscape around Oxford where he and Lewis regularly walked from Great Meadow to Wolverton; “Hobbiton is assumed to be approx at latitude of Oxford,” he wrote on the side of a map he shared with Baynes, in ways that suggest how the worlds of Oxfordshire and his fictional shire overlapped, if they did not fully merge; “Mines Tirith is about the latitude of Ravenna (but is 900 miles east of Hobbiton more near Belgrade).” If based on the map that Tolkien’s son Christopher drew of the region, to meet his father’s demands, the map provided the basis for their correspondence, him often including the toponymy in the Elvish for which he offered translations, to imbue the map with materiality as a legible surface.

But if Christopher Tolkien’s map is fundamental to Middle Earth’s geography, a labor of love that was an important tie to his father, and set a spin on Christopher’s later life as his father’s exegete, the role of shorelines in concretizing Gondor, for example, or its topography–

–and the fateful travel from the coastline to Mt. Doom–

Pauline Baynes, “Map of Middle Earth” (1970)/Rumsey institute

–becomes a living geography in large part because of how its unique coastal coloration frame a rich hydrography we move from the mountains to the sea, or the sea to the mountainous interior. And the nautical nature of its detailed coastal edge and rich hydrography was paired with an elegant pictorial liberties in legend of the sort Lewis earlier encouraged Baynes to take in his own narrative.

Baynes’ Narnian shores provided a crucial expansion of the series’ rich cartographic content. Ships may seem less prominent in Tolkien’s narrative, but the windrogse above Mordor reminds readers of the perilous if not fatalistic final overland voyage to rescue the Ring, and the provided a palpable canvas on which that voyage can occur, making the dangerousness of the voyage all there present, and perhaps the inviting calmness of the forests of Mirkwood, “the greatest forest of the Northern World” before it had been darkened by the evil forces of Sauron. The allegorical battle was mapped and remapped by Baynes during her long life, investing a cartographic claims of certitude in the maps that had begun from the large multi-sheet sketched maps Tolkien had made of Middle Earth during the World War of the 1940s, fixing it in our imaginations as a tangible surface in ways that suggest her deep dedication to the realization of the topography of the fantasy land’s public form.

In contrast to the densely mapped features of Middle Earth Tolkien penned, the dense fir trees of the forests Bilbo and his dwarfish friends passed in Rohvandion contained many secrets, hidden by the dense clumping of trees that conceal the steep slopes of the dark mountains “Emyn Duir” but the wellspring of the rivers that run through Greenwood the Great were lovingly detailed as a hydrography by Bayne’s cartographic skill to press the boundaries between cartography and art.

Baynes became quite the expert in world-making in the post-war period, an arc one might trace from her work with Tolkien and Lewis and her long term engagement with her hugely appreciative fan, E.H. Shepherd, through Wind in the Willows, and even Watership Down, tracing a map that served to reorient human readers to a mythic landscape not only of allegory, but of what might be called in literary criticism “another green world”–whose scales were not only more comfortable, cognitively and spatially, for many, but provided a crucial point of orientation a disturbingly disruptive global space, one to which many continued to often return through the present.

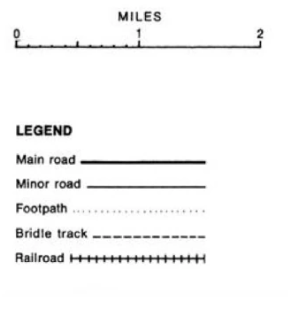

The new scale of the local she used for the rabbit warren in Watership Down (1972)–perhaps not as durable a fctansy world, and one of the more dated, that never achieved the mythic status to which the larger worlds of Lewis and Tolkien aspired in their self-conscious creation of modern myths of safe and dangerous spaces in the postwar years, have proved so durable for almost a century, through their transformation to film. But the rabbit warren in Watership Down, of a far more modest scale fitting many in the ecological turn of the cultivation of the local, underscored by the modest scale bar, if a rich hydrography, recalled the Ordnance Survey, it seems, that Lewis and Tolkien had sought to avoid. Indeed, if Watership Down was rather delightfully mapped at a reduced scale of rabbit warrens, between towns and rivers, the sense of a disappearing intersection of the animal and anthropogenic world is all to apparent in the several miles of rural countryside where rabbits dwell beside farms, in the Down beside the Heath that is rather idyllically preserved, but bound by the roadways that link Whitchurch, Overton and Kingsclere, cut up by ribbons of rail, highway that threaten to disturb the underground warren where the rabbits have long dwelled.

The novel returns to themes of heroism, bravery, and indeed struggle against a disappearing and remapped world, set in Hampshire, were first told by Adams to his two daughters on road trips, and developed in close readings of naturalist Ronald Lockley’s account of the social life of rabbits, based on the vision that arrives to one rabbit of the danger of the destruction of their underground warren, who navigate in a dangerous quest across the countryside, crossing rivers and roadways in hopes to dig a new warren in the nearby hills, taking refuge in farms to dig new warrens to live in peace. And the “maps” of the sites of warrens and the hares’ pilgrimage for a new home in the farmers’ hills suggest a dialogue with Baynes’ image of the soulful eye of the hare on its cover, a landscape that seems to accentuate, however vaguely, the actual curvature of the earth they live.

Pauline Baynes, Cover and Gridded Map from Watership Down (1972)

The reduced scale of the map notwithstanding, the story is of a monumental scale that emphasized the notion of looking at the overlooked: the gridded nature of the map of the warrens among which the rabbits move is relatively small in expanse, about twelve miles in length by six by four miles, but contained a microcosm of world-changing proportions. It is as if the “grid” of space is a context in which the rabbits move from one warren to several others, a massive shift of epoch proportions akin to resounding of a civilization–the resemblance to the Aeneid has been noted widely–in the context of a few square miles of human land: the disjunction of scale between human and animal remains in the mind of the reader, and indeed the equivalence of rabbits and human life has led the book to be banned in some nations, as China.

–The more clear-headed narrative of a life-or-death struggle against the remapping and destruction of the known world in Adams’ novel is perhaps best known for the characterization of a cast of rabbits, some of whom are saved by the intervention of a good-willed girl who is able to protect them from dangerous farm animals that humans have brought into their worlds–the landscape view of the fields in which the rabbits live is perhaps the most iconic of the the three maps she drew for the series, and shows the disjunction between the scale projection and the cosmos of warrens at whose center Watership Down lies, and in which the rabbits’ encounters with Keehar, the bird, who offers them the benefit and insight of his ability to fly, as they cross railroad tracks, and traverse the river at a peat bog, as if challenging readers to visualize the underground warrens.

Pauline Baynes, The World of Watership Down (1972)

But it is the narrative map of the encounters on the ground that the rabbits experience as they flee their warren that is the most aptly symbolized departure from a human bird’s eye view or a gridded map, and deserves to be photographed dire3ctly from the book, as Baynes chose to place the orienting compass in the form of a rabbit’s ears, communicating the importance of the view from the ground that the rabbits of Watership Down themselves experienced in their quest-like travels. The map is a clearly narrative map, keyed to moments of the text, but also able to be understood from a rabbit’s eye view, as it were, at an angle to our own understanding of the world. If C.S. Lewis famously disdained the skill of Bayne’s rendering of animals, her now iconic cover of Watership Down is perhaps her response to his chagrin; the map from an animal’s point of view suggests the invasive disorientation of any map to describe their instinctive reaction to the terrain.

Pauline Baynes, Rabbit’s Eye Map from Watership Down (1972)

The protection of the Watership is a survival of the known world, unmapped in the human farmlands, but to which readers are attuned, and indeed view the invasive humans as interlopers in the world of warrens that the narration primarily turns and focusses on, and are its prime protagonists, who live in a world of rabbit folklore, who guarantee to the underground hares that they will never go extinct if they agree not to overpopulate their world of warrens, that helps to orient us to the underground world that the farmers never observe, but using classical structures of epic poetry to transport us into the ethical world by which the rabbits have lived, filled with seer rabbits, rabbit deities, and social organization of rabbit warrens, which are idealized as s new map, perhaps more perfect, and far, far closer to the ground. Its own map, perhaps a greater appeal in a world of increased consciousness of the dawn of the Anthropocene, was seen as resurrecting the genre of children’s literature when many thought it was dead.

Very eager to read this post—looks delicious! Can’t wait to finish it!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!