The notion of the “offshore” suggests a realm out of reach of the law of the land, existing just off the coast of the regions supervised by regulators and taxmen, but has wildly expanded with the perpetuation of the legal fictions of the offshore as a place that offers an escape from national programs of taxation. Rather than exist only as a region beyond the shoreline or coast, and lie of the known map, the “offshore” is what escapes legal overview–and lies outside of national legal bounds. Arising as a convention to designate “offshore spaces” that lay outside of the recognized sovereign tax codes. But “offshore” regions need not properly be removed far from the mainland, or even from it at all–and are found on most any region or continent, save Antarctica. They are places where money of the superwealthy is invisibly routed, out of sight, not to remain, but to escape regulators’ oversight or the payment of a national tax or subject to national sovereign claims. The map of the offshore is increasingly a map of the unseen paths of where the superwealthy’s funds go.

The growth of the offshore is not a place to locate money, indeed, but through which circuits of international capital travel in a globalized world. For the expansion of the offshore is a not so odd consequence of globalism, and the increasing fluidity of finance to travel smoothly across territorial bounds–an ability to sequester funds just out of site, nestled in offshore accounts that are not subject to state scrutiny or traceable by paper trails. We have recuperate the notion of islands, removed from the shore, as a new way to symbolize and achieve the escape from regulation: the offshore as an entity emerged with the ability to dislocate and remove global capital from any place, and all oversight, as the circulation of global capital among the superwealthy resists being parked or located in a national framework or onshore spaces, but can be invested in sites of excessive demand and overvalued property.

The “offshore” is the ultimate example of the uneven nature of the valuation of space in an age of income disparities, and a fiction to allow these income disparities to be preserved. It is the geographic manifestation of a logic of tax avoidance that has become the exclusive privileged operation of the superwealthy, who feel entitled to subtract their wealth from the community they live, escaping the demands of living in any nation by shifting their wealth–“parking” their luxury cars to secure parking places or garages–that guarantee tax-avoidance, and indeed sanction a geography of tax-avoidance that is the privileged exemption of the superwealthy, those of a guaranteed worth of $30 million for the next twenty years, a coterie of increasingly large size as a bracket, that in 2010 included 62,960 ultra-high-net-worth folks in North America; 54,325 in Europe; and 42,525 in the Asia-Pacific, per Wealth-X, with the latter predicted to leapfrog both by the 2030’s. havens located offshore currently enable the super-wealthy–the richest 0.01%–to evade 25% of owed income taxes, in a global scam that, per Gabriel Zucman and colleagues, effectively conceals over 40% of their personal fortunes, rendering them opaque to any national government, and as a consequence erodes claims to national sovereignty, and indeed the authority of the post-Westphalian state that was defined by its borders. If the map of territorial waters loosened national authority from borders to accommodate a global economic playing field allowing actual offshore mineral extraction–in what were felicitously termed “international waters, free from taxation, and outside the nation-state.

The rise of the “offshore” as an geoepistemic category, or “geoepistemology,” in Bill Rankin’s terms, effectively legitimized by the broad “tax amnesties” granted by multiple governments extended to tax cheats after the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The amnesties from sovereign taxes many–even before the release of the Panama papers–to for the first time try to “to map out the frequency of tax avoidance, by income level” that was long unmapped, first among Scandinavian countries, to start to plot the range of financial subterfuges and conceits that removed the wealth of the super-rich from any actual tax franchise, affirming the existence of a perilously increasing wealth inequality: in America alone, the disappearance of a “tax gap” that only between 2008-10 amounted to a massive $406-billion between what taxpayers owed Uncle Sam and what they actually paid. This removed their wealth from the territory, and indeed from the sovereignty, that create a deep crisis in the form of a time bomb for the sovereign state, making conceits of “tarriffs” and “imports” almost pale as a lower level of financial transactions occuring in real time, or on the books, rather than offshore.

Is there any surprise that no moral authority existed able to compel Donald Trump to reveal his actual tax returns as U.S. President, when a gap of such proportions was the norm in the Obama era? The decreased in likelihood that America’s millionaires would ever find their returns audited have dropped up 80 percent than in 2011, suggesting a tacit acceptance of a gap in wealth that the geography of the offshore perpetuates and enables. Even after the stock market’s boom and bust cycles, returns of the upper 1% jumped in capital gains for mutual funds and financial accounts–measured in trillions of dollars in the last decade–that only solidified wealth inequality as a reality.

New stratospheric wealth levels pushed the collective net worths of the 1% considerably north of a hundred trillion; these rates of return were both not shared by other income groups, and not able to be comprehended by them. And such wealth generation granted rights to park wealth in an exclusively available geography of tax evasion of an expanded offshore constellation of money managers, outside sovereign reach; they would be no longer beholden to sovereign taxation agencies and were without obligation to states. The concentration of a hundred and twenty trillion in the wealth of the upper 1% created new spaces for wealth, apart from sovereign surveillance, where they might accumulate and grow, unable to be tracked in the global projections by which we are used to monitor other global events.

If the notion of the offshore is a relic of the post-colonial era–and began as a legal clarification of the category of offshore jurisdictions or overseas dependencies, removed from the European colonial powers as they enjoyed a liminal connection to formerly colonizing states–but it is perhaps better understood as the hegemony of a new notion of financial empire and wealth inequality. Today’s offshore are an exclusive insider knowledge, not open to many, but accessible to all initiated in schemes of tax avoidance, brokered in a bespoke maner by agencies–as Mossack Fonseca–who exploit loopholes of international law and the financial fictions of the ius mari to enable clients to sequester vast sums from national oversight–lest financial transactions be mapped. The offshore ensures opacity ing financial mapping, or the ability to place vast sums of money off the table, that sanction frictionless cash flows off the map.

In a global economy whose cash flows are more difficult to detect or embody–based less on the face-to-face, and rooted in the borderless fiction of the friction-free, increased integration of markets open multiple loophole for syphoning off national tax franchises, facilitating the sequestering corporate money–as the wealth of super-rich long tolerated to hold accounts described euphoniously as offshore, or, even more opaquely, as overseas, opening up fantastic speculation as to what that might really mean.

As sites for investment and financial regulation, the offshore lies outside legal view, but not off of the map. The entity of the offshore suggest the grey area of the law of the sea, outside sovereign authority or legal bounds, but as something like an apotheosis of the freedom of seas and an ill of globalization. The remove of the “offshore”suggests a growth of what might be called “ocean-like spaces,” open for untamable transactions–or offering tax relief by different measures–that are particularly corrosive to the governments on land, sovereign states from whom revenues regularly vanish: the offshore is afflicted by the very absence of familiar legal categories and of formal tax obligations to which most financial exchanges are normally subject, and, as the newly uncovered Mossack Fonseca records reveal, has its own, hidden geography of preferable locations through which money might be shuffled through shell corporations that are nominally located at offshore sites.

If the growth of oceanic space as a site absent from state authority, juridically neutral, and beyond sovereign reach, outside the apparatus of government, the growth of the “offshore” in recent years as a construct or luxury for the super-rich offered a site for the unmonitored financial transactions, not only a place of trade or ocean routes, but a site for storing monies that could accumulate unseen–even if, as in the case of Switzerland, the “offshore” might exist on land. But the offshore gained new prominence and currency in the frictionless economy of globalization, tolerated as allowing monies to be stored and sequestered tax free, in a region that no one country can possess, but exits for all as a lying outside national control. If many sites of the “offshore” were independent crown dependencies of the colonial age, the continued effervescence of offshore sites increasingly exist for the globalized economy: they are sites where money can be less clearly mapped or embodied, but lies outside of the maps of international capital flows.

The “offshore” most familiarly beckons as an idyllic as a place of respite and luxury, free from the imposition of taxes or the need to surrender money to a government. Removed from the sort of sovereign laws that demand the reporting income, the offshore has become a refuge for the super-rich, and for international corporations who want to disguise profits overseas. But its expansion is increasingly a major security threat for global finances, if not a symptom of the illnesses of economic imbalance that increasingly afflict the globalized world. If Zygmut Bauman aptly described the erosion of individual security and collective or individual commitments as a state of liquid modernity, and the offshore partakes of a similar liquidity: money departs from land governments to seek refuge in accounts not open to public view: the offshore is a microcosm of the erosion of state authority, as funds flow offshore as the place of least resistance, secreted outside the public eye. By locating funds “offshore,” removed from terrestrial land and tax audits, the subtraction of funds from the common good seems sanctioned, and has lead to a huge reduction on spending on infrastructure and social services in developing countries, where they are most needed. Bauman did not link the offshore to liquid modernity, but the remove from conventions and tax protocols, the cartographic essentialiation of schemas of tax evasion, accepted to facilitate the lifstyles of the ultrarich, provided a systematically recognized scam that has helped elevate many in a financial stratosphere, not following the rules to which others are subject, and, in truth, bringing us all down.

Many of the regions designated as “offshore” are not islands, but they are conceptual islands, utopic destinations off the map of financial oversight in what are “havens” for investment that allow many literally offshore economies with limited tax franchise to puff up their importance in a global marketplace; the advantages of being “offshore” in the Marshall Islands, Guam, Palau, Grenada, Barbados, Bermuda, St. Lucia, Trinidad and Tobago, the Maldives, or the Cayman Islands rise to prominence as ways to perpetuate a landscape of increasing financial inequality, an artifact of the globalized world where mainlanders can benefit from laws of exclusion for economic conventions, lying outside of tax policies of territorial waters.

The remove the “offshore” promises from sovereign laws, as if lying international waters just out of reach of economic boundary zones, evokes open spaces of leisure, dominated by yachts or pleasure cruises, as if exits from the pressures of the day-to-day work–yet its expansion is tied to the expansion of globalized markets and friction-free revenues able to traverse borders, and to enable ever-growing income inequalities in a globalized world. As countries such as the British Virgin Islands openly rebuff calls from England’s Prime Minister to reveal the ownership of offshore firms located in overseas territories and crown dependencies, begging time to “assess its impact on the BVI economy” while neglecting its impact on global finance and income inequality. How, one might ask, might the new offshore make the most sense to map?

The increasingly unavoidable place that the “offshore” has come to occupy in global networks has made problems of achieving transparency given the levels of legal anonymity offered in the “offshore.” Such somewhat hidden destinations, as the nation of Nive in the South Pacific, an outcrop atoll with a population below 2,000, was the site where Mossack Fonseca & Co. signed a twenty year “lease” in the mid-1990’s to incorporate offshore entities where they could be officially registered either in Cyrillic or Chinese, for example, bankrolling 80% of the government’s annual budget in exchange–until sufficient numbers of banks blocked money transfers to Nive, leading the government to rescind the offer of exclusivity, forcing it to relocate to Samoa, as it had relocated offices of incorporation from Panama to Anguilla and the British Virgin Islands, in a version of island-hopping that epitomizes the frictionless boundaries of the Offshore. The granting of such anonymous accounts goes hand-in-hand by the new identities the corporations are allowed to gain as they travel into smaller “offshore” dependencies, less reliant on tax reserves, which suggest new landscapes for investment and promise financial anonymity–with far less concern for the public good, which itself drops off the map.

British Virgin Islands

The concealed coffers of the offshore have long existed, although it hasn’t come into prominence. But the sudden possibility of massive data downloads leaked by whistle-blowers with access to accounts at HBSC or Mossack-Fonseca & Co. can help reveal hidden networks of money slipping silently across national borders that has fallen off the radar of government tax agencies and slid off the map into anonymous offshore accounts. The success of such evasion of sites have taxation have encouraged billionaire Peter Theil, among other projects he has deemed worthy of funding, to dedicate millions of dollars to the creation of offshore floating islands, perhaps off of California’s Silicon Valley, that might exist as tax-free refuges that are the free-market apotheosis of fellow entrepreneurs: the founder of PayPal hoped to create a free-floating offshore “libertarian island” by donating to the “Seasteading Institute” in 2008 to allow offshore tax avoidance and perhaps overeas working conditions close to home, in a floating island that would exist lose to land, but resist the confines of the sovereign map. As if the logical conclusion of a transference to most mapping apps online, the expansion beyond sovereign frontiers for Theil and partner Patri Friedman–Uncle Milton’s son–is to imagine a waterborne that exists off of the map as we know it, an “autonomous island” removed from tax authorities, and intrusive government intervention: crowd-funded “sea-floating cities” are the “next frontier” and perhaps the paradigm of a new offshore life–as much as a Utopian project.

The realization of movable offshore, if fanciful, was not uncoincidentally created by the online world, and an incarnation of the frictionless money transfers PayPal facilitates. But it suggests a geographical imaginary where one is at last free of messy national frontiers and state authority. The design of this new, permanent offshore, negotiated with a “host country” off of which the floating island would dock, suggests a mobility of work, life, and research without being hampered by national state authorities or bounds.

Allured by its inviting imagined landscape, the allure of the offshore is the license of border-free indulgence on booze boats for obtaining luxuries on the cheap, and the obfuscation of tax rules: but the emergence and growth of the “offshore” as a place for the tacit acceptance of anonymity possesses a seriously toxic topography insuring income inequality, linking criminals and corporations, keeping vast sums of money effectively off the books whose glitzy imagined geography that conceals multiple transactions.

Pleasure Boats Anchored off of Panama City/Shutterstock

Pleasure Boats Anchored off of Panama City/Shutterstock

Already in 1937, then-US Secretary of the Treasury Robert Morgethau took special care to warn then-President Franklin D Roosevelt how in Bahamas, Panama and Newfoundland, “stock-holders have resorted to all manners of devices to prevent the acquisition of information regarding their companies . . . organized with foreign lawyers with dummy incorporators and dummy directors, so that the names of the real parties in interest do not appear.” Since then, the practices enabling the geography of Offshore offices under the guise of fictive corporations and accounts whose names are able to change suddenly have dramatically grown, providing ways for multiple criminals and drug dealer to hide earnings as multinationals conceal foreign profits in anonymous unreported accounts.

The disturbing geography of black holes into which taxable earnings go “offshore” might be partly suggested by the charts of US corporations located offshore that do report billions of foreign taxable income–

Foreign Taxable Income of US Multinationals; Tax Foundation

Foreign Taxable Income of US Multinationals; Tax Foundation

–and the increasing amount of tax revenues that is tied to offshore companies.

1. The recent unveiling of the secret world of offshore tax havens has revealed a world that was in a sense hiding in plain sight: the network of companies’ bank accounts, “shell” companies and trusts has exposed a hidden labyrinthine world where half of the world’s wealth seems likely to reside. If the offshore exists for legitimate ends, we are told, the growth of secretive accounts and fictive companies have remarkably multiplied in offshore areas with such have allowed the disappearance of increasing amounts of money to suddenly come to light. And although much of the offshore is distributed in post-colonial lands and overseas territories and dependencies–vestiges of the British Empire, not subject to but British constitutional law, and outside its tax codes–that served, as a myriad of private Switzerlands, to create opportunities for secretive bank accounts never reported or accessible to sovereign tax agencies. It is a fiction of the overlooked, and as an overlooked set of transactions, is both important and extremely difficult to map–even if one can mapped as Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, that lie off the radar of the taxman, whose extraterritoriality removes them from sovereign scrutiny.

The level of secrecy and anonymity such sites guarantee is prized in the globalized economy. Globalization and multinationals, often with their main sites in larger countries as the United states, have contributed greatly to the recently explosive growth of the “offshore” as a category and a destination of funds, in ways that are tolerated both actually and tacitly, by the United States. Indeed, the United States is not only one of the largest locations of “offshore” sites–which the above map largely obscures–one building in the Cayman Islands not only houses 12,000 companies based in the United States, but the United States has become a major “offshore” practices of concealment from sovereign taxes. If many offshore sites are located in Delaware, Wyoming, Florida, South Dakota or Nevada, which don’t require the ownership of corporations to be released, anonymous “shell’ companies can be formed with amazing ease without legal identification, without identifying their owner or financial beneficiary. (A single, nondescript building in Wilmington, DE is home to 285,000 businesses–and the state as a whole holds far more corporations and corporate entities (945,326) and it has citizens (897,934), bringing in revenues in taxes of $860 million from absentee corporate residents, but costing other states some $9.5 billion, and mad the United States the number one center of the foundation of anonymous corporations in the world–two million–temporarily placing the state ahead of Switzerland and Luxembourg in the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index, before it recently slipped to fifth place behind Switzerland, British Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands.

Yet more practices for secretly concealing wealth exist or were framed within the United States than elsewhere, and indeed the legal fictions in which law firms in the United States and Canada specialized played a large role in its proliferation, and in the tolerance of such ethical blinders. And so, even as we map the ‘growth’ of the offshore sites from jurisdictions such as Panama to Overseas Territories as the British Virgin Islands to atolls, islands, or archipelagoes that beckon investors with promises of anonymity and tax immunity, the sanctioning of such policies, and indeed their legal architecture, begins in the United States–a major inland site of anonymous companies.

Anonymous Companies in United States–explore interactive version

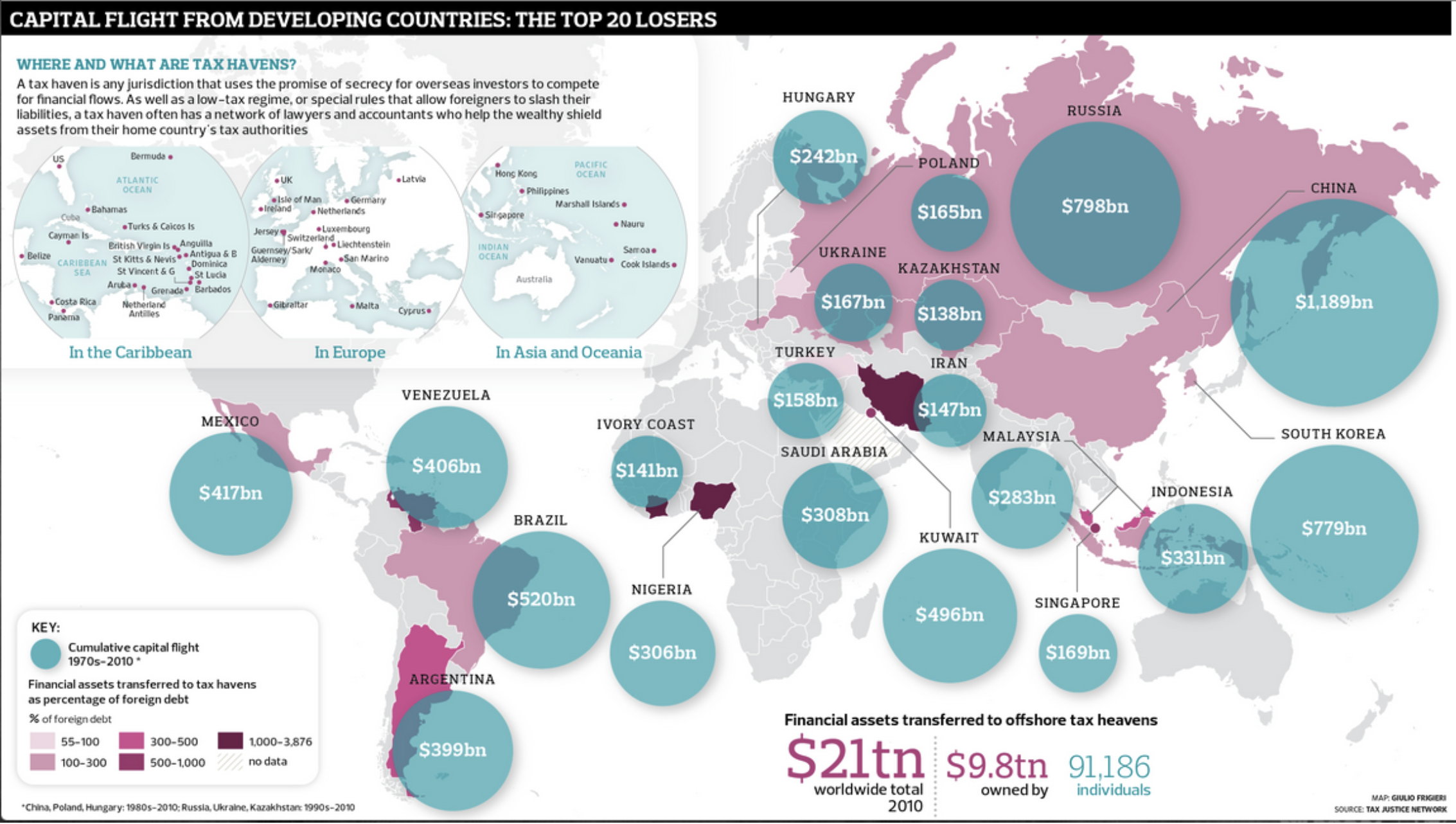

Secrecy is particularly created inland. The United States has come to be a prime site of the “onshore offshore,” although it is spread across the inhabited world. The “offshore” might be more appropriately metaphorically cast and envisioned as subterranean if not super-secretive. Yet “offshore” has emerged as a site for the accumulation of wealth and sequestering it in other sites–as on a desert island, in that favorite metaphor of buried treasure–whose relative liquidity has greatly grown or astronomically multiplied with increasing ease of cross-border financial traffic. The calculation in 201 that at least $21 to $32 trillion lies in “offshore” jurisdictions that allow financial secrecy or, more benignly, “tax neutrality,” suggests a new model for the unrecorded accumulation of wealth. And while many shell corporations are located on atolls, in the Caribbean, or in South East Asia, to escape regulation, the practices for constructing financial secrecy were devised far inland–most frequently by far, in the United States, if formerly in England.

2. Is it only in a time of increased cutbacks in public services, and fiscal constraints, that the regular leeching of local tax revenues that the expansions of the offshore enables that the United States has effectively encouraged has begun to be brought to light? is it a level of disgust at the inequality that they undersrote? or has the number of offshore entities reached a critical mass of the leeching of tax revenues of an estimated $8-32 trillion or upwards of private wealth to some sixty offshore centers, often lured by offshore-based middlemen to enter shady legal fictions, just grown too high? are most now seduced by a hidden architecture of offshore bank accounts and “shell corporations” that finally seems to threaten the very sovereign states that long turned the other eye? More likely, it is that the next revolution will be digitized, and that whistle-blowers now are able to dump the data of these hidden financial networks from a single thumb-drive onto the internet.

The secretive nature of isolated offshore sites offering tax immunity or limited tax liabilities belie the notion of the continuity of the world. It suggests a growing world of big finance, hidden from public view, that allows the multiplication of corporations and places to hide wealth or corporate profits. The creation of such black holes of global finance has grown dramatically, as bearer shares expanded in companies located in “offshore” sites, astronomically after 1990, and after 2000 and in the first ten years of the twenty-first century reached unprecedented heights.

Bearer Shares in Offshore Companies held by Mossack Fonseca/ICJI

If the function of the “offshore” tax havens was to concentrate wealth within the hands of the rich, or within multinational corporations, the growth of the offshore has created a further disparity of wealth. The growth of offshore companies that offered tax shelters to long existed. But from the mid-1980s, when the British Virgin Islands sanctioned the founding of corporations without public disclosure, or “shell companies”, that permitted a new level of money laundering and concealment of profits from taxation. The subsequent growth of offshore areas has been encouraged by the ability to transfer sites of location to different with atolls, islands, and offshore areas to avoid global scrutiny–or national scrutiny of tax authorities. But now, for the first time, there is the possibility, with increased dataleaks, to actually map the hidden world of the offshore, If a huge number of such assets once disappeared into those legendary “Swiss Bank Accounts” as revealed

The expansion of practices of secretive means of tax avoidance of individual and corporate wealth has increasingly enabled a growing gap between super-rich and poor, facilitating the illicit annual outflow of over a trillion of dollars from developing countries, according to Global Financial Integrity. To an extent, that geography was questioned not only by the financial crisis of 2008, but a growing sense since that all should pay their fare share of taxes, leading the papers of Mossack Fonseca to be anonymously leaked to the Süddeutsche Zeitung in late March of 2016. Yet the growth of a geography of sequestering funds free from taxes has allowed the offshore to grow rapidly–and the number of offshore corporations to blossom, allowing an escalating transfer of wealth through offshore regions where they are not taxed. The recent exposure of these findings–and more are promised in the manifesto of John Doe, who leaked the Mossack Fonseca files, “The Revolution Will Be Digitized,” who seeks to demonstrate how tax havens flourished with the knowing oversight of law firms, in ways that warped the global geography of big finance in the globalized world to the benefit of the super-rich.

Already, we had a glimpse of the huge proportions of local fortunes that were funnled from each continent into the leaked client accounts of HBSC, including trillions moving from developing countries in a shameful manner for tax evasion or money laundering: a huge share of the GDP of impoverished lands, subtracted from projects of infrastructure or public helath, might be recouped from such secrecy jurisdictions created by a single bank which effectively subtracted a huge portion of sub-saharan countries tax franchise:

The seqeustering of assets in HBSC bank accounts, here sized as a percentage of GDP, map the perpetuation of global inequalities that confirm an almost paranoid view of obstacles faced within developing countries, as private funds are substracted from the tax franchise.

3. Because such “offshore” sites attract capital flows with promises of secrecy, they cannot be tracked by their very definition–such secretive repositories of money attract tax-free dollars are valued for the silence that they promise. But their increased prominence may be all the more in need of tracking for their elusiveness in an increasingly globalized economy. The offshore has little geographical continuity, since it is a concept that has become increasingly mobile and mutable in a globalized economy, where the conceit of the residence of a company seeks to migrate out of the tax structures, rather than to a destination. Indeed,the term “offshore” reflects remove from sovereign financial oversight of a land-based territory–hence their tax-exempt or -reduced status. As the conceptual and metaphorical remove of the “offshore” spaces suggest their created nature as regions of tax-exemptions, offshore sites exist as prominent constructs only in an age of globalization. If all maps are surrogates for space, the mapping of the offshore–places that emerge on the boundaries or borderlands of states, or at the small states that have refused to enter shared tax-code conventions with other states, as Switzerland, Liechtenstein, San Marino or Luxembourg, lie on the margins of cross-border flows of global capital, by promising tax immunity.

Herman Melville described the most “true places” as those rarely down on any map, and waiting to be discovered: the present-day offshore lies in some of the areas that Melville visited, but are the reverse, and purely fictive sites, whose flows are rarely openly mapped. Was the experience of the “offshore” indeed once far more concretely expressed on many early maps, however, as its unknown nature was wrestled with as a real place. The modern “offshore” is hardly composed of “true” places, but exists in a space of post-modern big finance, far outside the concrete embodiment of mapped space in ways with which we must wrestle. For the offshore is in ways the least real, as it is also the most imagined conceit, existing entirely in so far as it is a recognized extra-territorial entity. The expansion of the offshore suggests the interest of the places remove from financial oversight: it’s unethical not to map places that exist hiding capital; the promise of tax immunity attracts funds to the offshore in ways that demand better mapping for the common good.

Yet the tax shelters of the offshore are almost a utopia within the globalized world. The tax-free places existing to attract investment and the sequestering of profits in secret bank accounts have come, sadly, to be taken as something of a model: in the Sunflower state of Kansas, as land-locked as it gets, the conservative movement’s “blueprint for Utopia” promising massive tax breaks for the wealthy and tax amnesties for 100,000 businesses, as a sort of panacea for an absence of economic investment, has siezed on the utopian nature of the tax-shelter: paired with the tightening of welfare requirements to reduce public expenditures, and cost-cutting by the privatization of the delivery of Medicaid, and multimillion dollar cuts to the state’s education budget, the erasure of infrastructure seems an anti-Utopian movement designed to wreak havoc among the state’s inhabitants and undermine trust in the public good. It is a microcosm of the “new offshore” places sprouting up, in ever-increasing desperate bids to convert actual spaces to the heterotopia of duty-free zones in airports. The American Conservative movement has championed a Blueprint for Utopia to eviscerate the local availability of public benefits and create a living hell for local residents by cutting corporate taxes through unprecedented levels of tax amnesty remote from anything like good government, but imitating the proliferation of the offshore inland–bringing the “offshore” inland in dangerous ways.

For the virtual spaces of capital structure the offshore–rather than trends of habitation, physical geography, or human settlement. But these marginal spaces of limited actual sovereignty have come to constitute particularly fertile spaces of the in-between; the metageographical concept of extraterritoriality is distinct from most mapped space, but holds a crucial place in the global economy. If maps are created to reflect the maintenance of the status quo, the extraterritoriality of offshore regions exist with increasing prominence because of the security and secrecy that they offer financial transactions. The sites of the offshore as such are created by capital, and map a shifting relation of the individuals to global space rich with greater implications than the advantages the ‘offshore’ tax shelters offer the superrich. These are in a sense borderlands that attract currency for investment, lying outside of the rules of governance that are suspended within their bounds, at a sense lying at odds with sovereign states with potentially dire consequences for many of the world’s inhabitants.

Although maps have been long drawn of the spaces of state sovereignty, numerous conceptual questions are raised by the mapping of the offshore–and of the effects of its relatively recent expansion of corporate globalization over the past ten to fifteen years. The expanse of the offshore in the interstices of globalism, and with the growth of multinationals, has come to assume notional autonomy and importance in the global economy as unprecedented as it was largely unforeseen. While the offshore exists as a set of places that are “hidden” from tax authorities, these spaces combine extraterritorial entities that fall outside of actual legal jurisdiction–such as Guernsey or the Isle of Man– that come out of a traditions of feudal law, with the post-colonial spaces which continue to lack independent sovereign authority, whose elites have retained a liminal relation to departed colonizers, such as the British Virgin Islands, Marshall Islands, or Hong Kong, opening up new spaces of extraterritoriality, not maritime but rather partaking neither of land or sea and indeed without recognizable boundaries. The post-colonial places of the offshore have a precedent in feudal law, but a cultural geography that is increasingly separate from offshore/onshore divide, existing as extraterritorial fictions that enable the global circulation of big capital to escape taxation. They include enclaves as Switzerland or Luxembourg, but are rarely found on a map or shown in a map projection.

The increased attention to the offshore as a basis for the globalized economy of recent years may imply a shifting order of the global economy–where refuges from financial oversight are elided with spaces removed from land-based governance, to which most governments effectively agree to turn the other eye. They become the “other spaces” of globalization, less defined by their own inhabitants but their attraction of foreign capital. Historically originating in sites understood as dependencies that were the inheritance of a colonial world, the robust economy of the offshore archipelagos of tax-immunity in places from the Bahamas, Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Samoa, Malta or Antigua and the Barbados have become islands in the minds of tax lawyers, declaring their own tax immunity on paper, and gaining new prominence on a global map as a destination for corporate monies as much as the tax shelters of the wealthy they’ve long served–but are the most prominent islands of the mind of the twenty-first century.

Despite the misleadingly anodyne sound of the increasingly elastic construction of the “offshore,” the concept disguises its danger to the liberal state: the designation of those spaces where the playing field isn’t level, and investments are surrounded by a wall of secrecy impermeable to the IRS or other sovereign tax agencies, gathers the tolerated self-declared spaces of tax-exemption which have less to do with actual shorelines of habitation than their remove from the walls of secrecy about financial transactions–and the pathways of routing financial services and capital on separate streams outside the seas of data to which governments enjoy oversight. For rather than islands being known by their inhabitants, they are islands removed from sovereign authority: and in an age of globalization, where almost all inhabited lands are mapped by GPS, the “offshore” exists as a refuge for financial flows. The flag of the offshore is the status of being tax exempt.

The oddly imprecise entity of the offshore is a space created by a rewriting of global commerce. For it is fostered and encouraged by the finances of multinational firms in a global economy, where corporate entities seek to evade taxation laws with their origin in countries defined by borders, boundaries, and shores. The “offshore” evades spatial sovereignty, in other words, and creates shelters for big finance so that they are free from any national oversight. The offshore exists as an unbounded concept and conceit, no longer bound to actual shorelines but an apparent vestige of the post-colonial world that effectively legitimizes a continued unevenness of global taxation rates.

The rapidity of the multiplication and global proliferation of “offshore” tax shelters in recent years that form part of the offshore world are outgrowths of the globalism of multi-nationals, they suggest new places for evading sovereign laws, as much as new spaces of cartographical colonization. Their proliferation in the microclimates of the South Seas and Central America, as well as the dependencies and small states in Europe, are new spaces in the mind that seem designed to attract the attention of investors: as invitations to consider new spaces of financial transactions, they recall the fantastic cartographical fictions that embellish the edges of medieval and early modern world maps, and are perpetuated in the spatial rhetoric of early modern and late medieval marine charts typified by the offshore spaces that are so enticingly mapped in isolari–brightly painted unknown islands colored in red, gold, or green beckoned the eye and imagination of readers as if with the promise of untold riches, and exercised attention as removed form the landlocked, surrounded by rhumb lines. Of course, rather than be the sites where actual or monstrous inhabitants dwell, the offshore is the preserve of promises to hide financial transactions, subtracted or siphoned from public expenditures, secreted away in anonymous shell companies or personal or commercial bank accounts. They promise not the fantastical inhabitants or riches of foreign lands, but the new fantastic of the unseen.

Modern offshore spaces may not in fact be spatially removed “islands.” They are instead places technically removed from the global financial map–or at least the map of the spaces of sovereign financial oversight. The islands (literally, tax refuges) of the “offshore” are only of course figuratively removed from a shoreline, financial destinations for vast sums of money to be secreted in the sea of big finance, serving as shelters for the super-rich to secrete cash reserves in untaxed form and for companies to tether profits as yachts without any impunity as their income grows. The hidden channels and legal fictions by which the legal construction of the offshore manages to work above-board isn’t so evident to many, but the proliferation of places offering tax immunity seems the ugly underside of a world which lacks shelter for actual refugees, has created a relatively recent a proliferation of refuges for global finance–sums subtracted from tax revenues once secreted in the continued conceit of the “offshore.”

The offshore of the present day is removed from the offshore imagined in earlier periods, but oddly replicate the fictive relation to the offshore as a site of invention and imagination, a site of otherness no longer corresponding to the observations of the inland. But they may, indeed, be filled with as many monsters–and even based on a less tactile sense of the dangers that exist as one ventures metaphoriclaly offshore into the financial unknown. Whereas isolate or the marine charts of sailors depicted far off sites, removed from mainland sovereignty, and ports were often of quite difficult arrival, the point of the “offshore” is the ease by which money arrives to accounts without oversight: if the offshore is removed from the sovereign, it has been domesticated into the global economy, stripped of the dangers of the seas, it bodes far more dangerously for the world.

Detail of Sea Monsters depicted in North Sea, in Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina (Venice, 1539)

Detail of Sea Monsters depicted in North Sea, in Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina (Venice, 1539)

The sites of the shadow economy of the financial offshore are analogous to a travel poster of destinations where money might be stored and subtracted from landlocked regions–even if you don’t ever go there–is recorded in the static map of the foreign secretion of where global capital congregates in offshore demands a far more dynamic interactive chart like that of the anonymous companies. Since the offshore sites serve as sites for businesses and individuals to self-servingly subtract themselves from the tax franchise, they have spawned in the new spaces for anonymous entities, which multiply as if in the financial Petri dishes of globalization on the edges of state borders and of sovereign authority. For in such dependencies that invite anonymous companies, the “laws” of havens essentially invite individuals to place money there, or corporations to base businesses there, to escape tax regulations that other jurisdictions have adopted. The site of the offshore offer sites for basing companies on paper, or routing financial flows, so they are not noticed by other states, whether it is a territory with its own legal system or a dependent territory overseas. But it is misleading to see the proliferation of offshore sites in spatially removed lands–

–as proliferating in accommodating climactic conditions, as in petrie dishes, so much as the symptoms of globalized finance.

4. The growing currency the offshore in global financial markets gained wide traction as a legal fiction corresponds to the growth of tacit consensus allowing the flight from local tax codes, and the secretive reigns. If the notions of utopia, or island refuges, might have existed on the horizon of earlier spatial imaginaries, scattershot tax havens across the South Seas, Mediterranean, or Caribbean suggest a congestion of financial capital that has run offshore from the markets they were generated, increasingly warping the destination of money in the world’s economy and ensuring that the playing field will stay as uneven as possible. Rather than a set region, the sites of the offshore are declared by fiat, through legal conventions and tax laws where local tax revenues are in part foregone–and others invited to store money there without impunity and guarantees of full transparency. This encourages the multiplication of shadow companies, existing as storefronts, but with few employees, and anonymous entities that are more profuse than the actual dwellers who live in the relatively small sites of the offshore, which allowed the offshore to expand as sites of convenience for the wealthy multinationals that are based inland.

One might best place the growth of the offshore in the arrogance of the widely growing anti-tax climate stretches from America to Russia to Africa. Although we tend to see it locally–as made evident in maps such as the Tax Foundation’s Tax Climate Index--a similar world-view has distanced taxation from obligation, and worked to recast, much as has the Tax foundation, variations in tax liability as something as accidental as climate or geography, rather than an intentional planned fraud.

The profusion of tax havens function along something of a similar geographic lie. If since distanced by its mapmakers, the map reveals a deep desire for tax avoidance increasingly conflated with the ability to declare areas as exempt from tax liability. The expansion of the “offshore” as a circumlocution for places promising tax-free investment reflects its transformation from places to tax refuges for the super-rich: noted by red dots clustered in three areas of the globe where they have congregated in the header to this post, clusters of islands–or regions–lying in the European Union, former colonial lands in Central America, or the South Seas has come ashore both literally–they exist not only on islands, but in Amsterdam, Switzerland, Delaware, Miami and Latvia–as they have come a public concern both for tax evasion and with the recent–and still not clearly understood or mapped–leak of the Panama Papers from the firm Mossack Fonseca, who have provided trust services since 1986–and whose shredded papers have been recently seized in the hope to map a clearer trail of their hidden financial services.

The proliferation of such “tax havens” were created to serve specific ends. Indeed, in the crown dependencies and “overseas territories” of the United Kingdom such as the British Virgin Islands and Cayman islands, the number of incorporations of shell companies has spiked as the number of incorporation specialists who promise the creation of sequestering funds from taxes in shell companies in offshore jurisdictions has grown globally. And in an age of globalized finance, where borders mean far less and transfers are easily accomplished within legal conventions, the funneling of monies outside tax responsibilities has grown to new proportions, as sites of offshore finance have grown wherever there appear to be islands.

Although the universe of the Offshore exists more as a hidden network of financial exchange than as sites for setting up shell companies and invisible corporations, the growth of its opaque economy of concealment has spread over the globe in recent years in ways that serve the borderless and frictionless traffic of monies as a direct consequence of globalization–allowing a growth of new shell corporations established in recent years through Mossack Fonseca to sequester monies in the Caribbean so as to avoid taxes.

Such havens don’t properly lie on the map–based largely in small countries, often just off the coastline, they are valued for the peculiarity of their declaration of welcoming anonymous companies that effectively invested them with extraterritorial status. Offshore sites are constructed as sites for individuals or corporations to sequester profits that can be legally “hidden” in shell companies or anonymous corporations to evade taxation. The expansion of these offshore spaces have served to attract capital to what once seemed the edges of the world–although the ease of opening new spaces that circumvent tax policies have increasingly invited the expansion of the category of the “offshore” as a virtual nation in a globalized world, where the friction-free movement of cash encourages countries to declare themselves tax havens hospitable to opening shell companies. Although many of the beneficiaries of the shell companies may reside elsewhere–and multiple shell companies might reside, in some cases, at the same actual address–the “offshore” maps something like a set of portals to a parallel world of global finance, offering tax reductions or tax havens and ready access to funds. To go offshore is to be rendered secret, unseen, and to ensure one’s transactions are opaque.

The relatively recent proliferation of “offshore” sites is not only a dangerous means of siphoning off monies for infrastructure or the public good in many places, by effectively thwarting the taxation of trillions of dollars. It also serves as legal conceit created to allow the perpetuation of income equalities in a globalized world. The growth of the “offshore” seems a reflection of the global nature of big finance, using guarantees of secrecy and ready availability to store monies that are effectively off the map of the sovereign state–and the offshore is a negative space to secrete hidden investment out of sight from onshore authorities that have only started to be assembled in a collective map–precisely because the secretive nature of the “offshore” is their attraction as destinations to concentrate wealth. Although the conventions of terrestrial mapping of the globe are incommensurate with the ties between clients, corporations, and shareholders that have expanded the opaque constellation of an offshore world, clustered to suggests their increasingly lopsided nature in an ever-globalized world. Independently from the places in which shell companies or anonymous corporations are ostensibly located, the proliferation of transactions holding companies allow–anonymous transactions effectively hidden removed from a clear map of global finance in the utter opacity of the offshore networks that each allows–offering a portal to the shadow-world of big finance.

The dramatic expansion of the offshore as a site to which to move monies reflects the new frictionless, borderless economy of a globalized world, where monies can be made invisible to tax authorities with relative ease. The legal fictions about the offshore create the presence of legality to subtracting money from the taxation, by essentially shifting its location from a sovereign state to the non-place of the offshore. While legally registered at these localities by registered agents, even if the bulk of their personnel, products, and even executives are located on a mainland to be named, the fiction of the offshore consists of new networks of legal arrangements that result from the increased portability and mobility of financial capital, and the demand to conceal its flow: not for no reason are blacklisted individuals, from weapons financiers to drug lords to terrorists particularly solicitous of the secret services the offshore offers, in the company of Silicon Valley tycoons and the super-rich, as well as multi-nationals that are ostensibly based in the US. While the tax-free status was tolerated for many in Switzerland or in post-colonial dependencies, the burgeoning use of offshore sites for tax evasion by multinationals or as centers for terrorist activities, nuclear trafficking, and drug lords reflects the expanded invisibility of the traffic of monies in a globalized economy.

Increasingly, the growth of the offshore in sites in the Caribbean–from Panama to the British Virgin Islands to Nevis–have grown in expanse from the demand from the American economy if not industries that are actually based in the United States.

5. While “offshore” locations were inherited as artifacts of the law of the sea, lying outside national jurisdiction in an extraterritorial expanse, the offshore has flourished in the ambiguity of post-colonial spaces long defined as lying outside sovereign tax codes. Indeed, the proliferation of tax havens that were a convenience for the super-rich was embraced by multi-nationals as sites of concealing their earnings and wealth. Pressing the symbolic anthropology of the offshore, might one better trace a conceptual genealogy of the current prominence the offshore has gained in our ever-more globalized world?

The dramatically increased mobility of money has lent new status to the secretive nature of shadow companies in sites from offshore islands in the Caribbean to the South Seas to semi-autonomous principalities form Liechtenstein to the Isle of Man–and the growth of quasi-legal entities, outside the purview of sovereign states, which exist as sites for funneling wealth or capital flows out of the sight of tax codes, into anonymous companies based in one jurisdiction, but owned in trust by someone in another jurisdiction, with trustees in yet a third. As if in a game of three card monte with trillions of dollars, and involving legal agents for sequestering funds under the shells of exotic beaches, the legal fictions of the offshore are created by big finance, seeking havens from the taxman, less as spaces than conceits, with chains that tie them around the globe. Such sites, suitably far removed from office-work, use their bucolic settings as veils under with the opaque routing of capital and transaction of monies to shell companies can legally occur. They are, in a sense, and express, the utmost alienation of money from the workplace.

Ocean maps have long served to organize the viewer’s relation to “offshore” sites lying outside national waters, apart from but in relation to a mainland–the boundaries of the so-called law of the seas–the ancestor of the concept of an extraterritorial mare liberum first theorized by the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius. The absence of a rule of national law in the mare liberum exempted it from national oversight–areas lying outside national control and beyond the continental shelf or mapped outside exclusive economic zones, and so economic sovereignty. But the offshore economies of shadow companies suggest a negative universe of tax evasion, designed to occlude taxable income from sovereign states, and something like a shadow universe of the tax-free, which has only begun to emerge from the legal cloak of secrecy that has created the growth of a range of offshore sites–many situated at a considerable remove from the mainland, as offshore territories, as Cyprus, the Isle of Man or British Virgin Islands, but others flourish deep inland–like Switzerland or Delaware.

The current expansion of a number of “offshore sites” for storing monies in faceless shell companies reflects the growing desire to remove monies from oversight, and effectively make it disappear: the amount of “hidden” money that lies offshore in tax havens which contain accounts estimated from twenty-one to thirty trillion dollars, hidden from the central banks of 139 nations in a shadow financial system that is only beginning to be mapped with increased interest to understand the concealed recesses of the globalized economy. In a world of big data, when transactions stored on hard drives are easily diffused, the offshore constitutes a final frontier of secrecy, and the ostensible sequestering of funds outside of public view, and have grown in ways that makes their tabulation even uncertain–exchanges on the books of the Panamanian firm of Mossack Fonseca in the Panama Papers provide a rare opportunity to glimpse the shadow world of the secret transactions that offshore shell corporations have facilitated and allowed to expand which Alice Brennan of Fusion mapped in a data map linking between clients, shareholders, companies and incorporation agents based on the 2.6 terabytes of data from an allegedly “secure online connection”–a universe in parasitical relation to clients’ money situated in the US, mapped by ties marked in blue lines, designed to evade the Internal Revenue Service, even if the download did not list American names. These cobalt lines–fault lines in the offshore economy–suggest a classical remapping of hidden pathways of exchange, and a network of the offshore. They map the complex archeology of the offshore economy, whose expanse has increasingly grown as a strategy of evasion, a sort of negative space that intersects with areas of extraterritoriality.

Indeed, recent attempts of the government to reign in the offshore–and it’s “not the average family . . . that avoids paying taxes by offshore accounts” or by tax “inversions,” President Obama reminded the nation–reflect the explosion of this offshore universe, and the increasingly evident unfairness of the access that a specific set of clients have to the offshore as ways of not shouldering their tax burden.

The offshore island was once seen as a model to understand oceanic expanse, and marking sea travel. In the earliest forms of mapping: early maps of Indonesia islands, the Marshall Islands, and archipelagic spaces oriented one to space partly by island travel. The meanings attached to islands have encouraged us to think about space and spatial travel, moreover, and suggest a discovery of new spaces, new laws, and new economic practices that open a new geography of sanctioned macroeconomic practices. But the complex virtual archipelago of secretive shell companies established in offshore sites like the British Virgin Islands, a self-governing overseas territory, where some 215,000 companies were established to evade national tax codes by the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, whose newly exposed 2.6 terabytes of files help to delineate how registered agents create a hidden network of clients, shareholders, and beneficiaries.

The expanse of the offshore might be best measured in the amount of monies that are funneled through its sites–as much as their location. For the fungibility of monies in the world of the offshore defines its largely opaque transactions. The economy of the British Virgin Islands is based on the over 950,000 offshore companies incorporated to evade paying taxes on their earnings, as tax shelters set up in other British jurisdictions from Jersey to the Isle of Man to British Anguilla. Since 1977, they have grown as a constellation-like web of shell companies, whose hidden relations are difficult to visualize, if not to map, since they bear such baroque relations to terrestrial space, far beyond the sight of the regulatory agencies of big finance. In an age of the increased proliferation of big data, the release of the Panama Papers hard drives can reveal a data map of the ties between clients and shareholders as a universe of financial ties only waiting to be explored–if whose identities are hidden to protect the clients involved.

The data map showing clients, shareholders, incorporation agents and companies using Mossack Fonseca’s services suggests the extent of the complexity of the offshore as a network of big finance, all to real for its participants, as much as a conventional creation, with limited overlap to actual space. Indeed, the intentionally unclear relations to the sovereign taxation systems they evade, by relations between clients, companies, and beneficiaries benefiting individuals from David Cameron to Vladimir Putin to FIFA boss Gianni Infantino. And if Fusion figured the uncovering of this previously opaque parallel universe of big finance as something like a space of interstellar travel, conjuring the wonder of discovery as if from the perspective of the pilot’s chair in Star Trek’s USS Enterprise, the Mossack Fonseca Universe revealed in 2.6 terabytes suggest a global financial network enabled not as a set of spatial relations but unearth the archeology of networks smoothed by the frictionless transaction of funds across a globalized world.

The expansion of the “offshore” as a conceit has created something of a negative universe, and a new way of locating financial transactions in a globalized economy, promoted in part by multinationals and as conveniences for the super-rich: as capital circulates globally, the range of sites declaring themselves immune to sovereign tax codes offer wrinkles in space for concealing earnings in the cloak of legal secrecy. For the recent growth of the ‘offshore’ exists to offer secrecy and is designed to render invisible the storage of monies as a condition of their existence; the recent release of the Panama Papers offers a rare peek inside this network of financial services otherwise removed from public scrutiny–rarely disclosed–that suggests the expansion of its web of financial services and the intensity of activity of global finance located in the sites of the offshore.

6. The expansion of the offshore as places that lie outside a sovereign taxation code, and in international waters, are often advertised for its circumscription of tax codes. They are often seen as invitations to tax avoidance of one space, as much as a place or space. The offshore seems almost non-place of globalism, existing both on the map but taking its spin from being off the map of taxation, and negatively defined by its autonomy from tax codes. The effective global subtraction of money from tax franchises–and investment in local national infrastructures–suggests a scheme of global injustice and tax evasion of massive proportions, irrationally expanding as the options of offshore ‘investment.’

The increased number of sites for legally sequestering huge sums of money reflect the capabilities of offshore sites to secretly store funds for an array of dubious clients, including foreign oligarchs, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, African dictators, Mexican drug lords, oil sheiks and multinationals, who seek to sequester huge amounts of money and preserving their own anonymity–a global problem, as President Obama observed. The irony is apparent. By offering opportunities for tax minimization, security, and easy access, the offshore persists as a system of “pirate banking,” even as big data makes increasingly evident wealth disparities across the inhabited world that the offshore helps reinforce–even as banks, from HSBC and Credit Suisse, as Mossack Fonseca, deny any wrongdoing in establishing further offshore shell companies to avoid taxes, or the rationale of the expanded role of the offshore in the global economy.

7. But the recent expansion of the concept of “overseas territories” of extraterritoriality to regions or places that can declare and negotiate their own status as offshore sites has occasioned a dramatic expansion of self-designated tax havens impossible to see save as unfortunate artifacts of an increasingly globalized world. For the growth of the offshore as sites that create concordats to evade local tax policies suggest a new relation to mapped space, as well as for the sequestering of capital in overly privileged ways. Although international waters once suggested remove from the law of the land, the increasing currency of offshore sites in an age of the multinationals and big finance have allowed the unprecedented expansion of the category of the offshore for private ends. Now unmoored from geography, the offshore defines preserves of tax amnesty, not subject to sovereign state’s oversight, or less stringent regulation and not even necessarily situated at sea or difficult to navigate. Inviting corporations to have bases at their tax havens, provided that they don’t engage in business with local citizens. As if the mirror-image of growing global crises of refugees that promise to define the twenty-first century, the artificial shrinkages of tax franchises globally is endemic to the globalized world.

The autonomy of the offshore was early mapped in the stick-charts of Micronesia, whose carefully curved pieces of wood or bamboo are laced with fibre, representing the effects of currents and winds on canoes, and including islands as bits of coral or cowrie shells from the ocean, to map place in a mutable nautical space defined by ocean currents, winds, and atolls in order to encode sailing directions for inter-island travel:

British Museum (Nineteenth or early Twentieth Century chart from Marshall Islands)

British Museum (Nineteenth or early Twentieth Century chart from Marshall Islands)

National Library of Australia (Marshall Islands, 1974)

National Library of Australia (Marshall Islands, 1974)

The sense of land that lay offshore was a fascination of the isolari of the medieval Europe, offering works that sated visual and imaginative curiosity that caused them to be widely reproduced, surviving even in an era that saw widespread innovation and expansive of comprehensive terrestrial coverage in global projections. The genre of isolari indeed rapidly expanded during the age of Atlantic discoveries, as they preserved places of recent discovery or unknown status. If we long considered such islands outside of the regions of broadest settlement an emblem of the remote, the offshore has re-emerged with a vengeance in the post-war years as a fiction of locations lying outside taxable lands, areas of extraterritoriality, even if it existed onshore–the new offshore lies at judicial if not spatial remove, where businesses and bank accounts relocate to reduce tax liabilities.

Their expansion in ever-growing numbers reflect the broader currency of reducing tax liabilities in a globalized world. Offshore islands and areas lie outside the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEC’s), and derive from the status of offshore islands from Nevis to Nauru in International Waters subject to the Law of the Seas, the reconstruction of inland sites as actually lying offshore, and as such offering tax immunity to those interested in secreting large sums of monies–or profits from overseas trade–from tax authorities and the obligation of taxation. And in the age of the multinationals and big finance, the winds and currents around an island or the effects of the environment on arrival are less the point than the offshore sites where funds can be deposited, or places have been legally defined as lying outside the economic integrity and tax codes of sovereign states. In an odd victory of the jurisdictional map, the constitution of an extra-territorial offshore is legally redefined as a tax haven, effectively constituting a funnel for global capital to disappear outside of the ecosystem of notions of sovereignty that reign on land.

For the offshore attracts the interests of individuals and of multinational companies–or, rather, the capital an individual or company accumulates, whose monies for practical purposes disappear from the visibility of the rest of the world–rather than individuals alone. In ways that prompt reflection on the characterization of corporations as individuals, this offshore is increasingly only to a few. Whereas overseas territories took advantage of their extraterritoriality–the British Virgin Islands or Cayman Islands–such sites where shadow companies can be based and their profits stored without possibility of taxation have proliferated with globalization. The increased propagation of tax shelters, havens, or mitigations warp not only world finance but exemplify the warping of sovereign taxation of multinational within a globalized world. And the weird promise “going offshore” offers an increasing number of sites who have declared themselves tax havens for multinationals and private assets provides a tragic post-colonial legacy: the expansion of the offshore has led to an increased subtraction of monies otherwise destined to social infrastructure and public services in nations whose super-rich and corporations stow their profits and capital offshore and overseas to evade local taxation laws.

8. The notion of the “offshore” invokes the conceit of a law of the seas, absent from the conventions of those states based ashore, it is based on the convenience of globalized markets and frictionless borders that facilitate money from escaping tax codes. For the offshore defines those places where the conventions of tax regulations don’t exist or are reduced for the shell companies who they attract: while offshore sites were once artifacts of the post-colonial world, actual islands from Delaware to Latvia, Luxembourg to the Cayman Islands and Monaco to the Bahamas, “offshore” places invite commercial secrecy and non-disclosure of income in an age of big data. The provision of financial secrecy–at one time confined to Switzerland–where huge sums of money are able to be sequestered with little eye to the public good, removed from banking regulations or oversight, and invite not only sites for the accumulation of untold individual riches but money laundering for multinationals and the super-rich.

Late capitalism has newly colonized “offshore” spaces that first existed as sites in the post-colonial world as refuges from state authority, whose existence is tacitly tolerated even by the World Bank. (Obama has long sought to recoup funds from offshore sites, despite deep GOP opposition, but his new tax policy to return a share of the $2 trillion invested in hidden sites ‘overseas’ to avoid taxation, suggests a single-tax of overseas profits at a very low 14%, to be followed by future foreign earnings at 19%–a hugely sizable cut from the current statutory rate; this, however, despite stiff Republican objections to any tax assessment that would challenge the current loopholes.) And even as bankruptcies have offered the opportunity to bring about the impositions of restrictions on the self-proclaimed sites of the offshore, from Switzerland to Cyprus, the proliferation of new “offshore spaces” from Latvia to Tibet stand to undermine any gains of the curtailing of wealth in shell companies nominally located in offshore space.

The timeline of the transformation of the “offshore”that lay outside the rules that sovereign states and governments have established, and outside of which they exist, suggest an insufficiently scrutinized genealogy of the cartographical imaginary. For while offshore have long exercised curiosity as destinations of imagined exploration, located on the margins or edges of maps from the middle ages to early modern Europe, the rehabilitation of the offshore in an over-mapped world suggest the rise of evasive practices in an age of near-ubiquitous mapping. Any maps that exist of the current offshore sites would be less understood as actual destinations, of course. Rather, the enticing climates, seashores, and beaches of most offshore sites serve only to help designate sites that seem to suspend regular conventions of the overseen, relaxing the protocols of public oversight as if to legitimize the subtraction of tax scrutiny in suggestive in insidiously harmful ways. In setting their conventions apart from the states, offshore places exist to provide sites for multinationals to evade corporate taxation to which they would otherwise remain subject and alternate architectures for the circulation of profits on a global playing board that is configured as an international confidence game of ever-expanding independently negotiated tax havens–as well as longstanding overseas territories.

In a recent interactive visualization, tax havens are sites rendered as dots superimposed atop the contours of sovereign states, but attracting visual attention as if bright spots on a darkly drawn field that one might associate with the terrain of tax imposition.

The emerging spots noted in purple suggest the migration of tax havens to Africa (Nairobi and Gambia, where online registration of corporations will last but thirty minutes) and Asia (Tibet), but their predominance in Europe and the Caribbean. The ecology of the tax havens across the globe suggest a parasitical growth on the conventions of the postcolonial world, whose expansion bodes poorly for perpetuating economic divides.

9. Offshore islands were of course long beacons of particular curiosity not only for cartographers but for those inland for their alleged difference from the worlds of the landlocked, from which they were long seen as the refuges as well as places of exile. But the extent to which the offshore entities suggest a corporate “Utopia”–no place, literally, or no place on the financial map of tax authorities–might be examined in the notion of the fictions of the offshore in Thomas More’s playful dialogue of 156

The narrative of More’s Utopia hinges on the fiction of the offshore: the traveller Raphael Hythloday offered More and Peter Giles evoked the wonder of an offshore island in the playful dialogue about governance as a possible example of good government readers might entertain. In the age when the description of “New Islands” within the letters of Amerigo Vespucci’s letters voyages to the “novae insulae” had become a bestseller in the first age of printing, More imagined encountering a sailor who witnessed these new islands, of Portuguese descent, and had undertaken further offshore explorations after he was released from service after sailing on all four of the Vespucci’s voyages. The sailor characterized by his travel-worne “sunburnt face” that bore visible record of his nautical travels, encouraged by his aptness at using the compass to explore offshore worlds, revealed him as a new social type of the mariner, and mediator of the offshore that had grown with new appreciation of the removed and in-between.

“There is no man this day living that can tell you of so many strange and unknown peoples and countries as this man,” learned More, as did the reader, and he becomes a conduit for news about foreign economic practices and laws that serve as a mirror to reflect on the partitioning of land, legal custom, care of the poor and the public management of economic wealth as well as to reflect on what constitutes a civilized state–in the senses of both a sovereign and human state. At the end of his voyages with Vespucci, Raphael had “obtained license from Master Amerigo . . to be one of the twenty-four who at the end of the last voyage were left behind” at the farthest point of the final of Vespucci’s four New World voyages–in a fortress in present-day Brazil–and skilled with the compass led him to travel to further offshore regions, from Calcutta to Ceylon, to encounter the island Utopia. That island’s inhabitants served to exemplify the alternatives of economy, social class, justice, and good government in More’s dialogue, as the offshore provided the form of good government that More asked readers to entertain as a criticism to the alternatives to the status quo. While the island of Utopia was a counter-mapping, in a sense, of the race for colonizing the New World, its presence provides a precursor to the dystopia that the current proliferation of the offshore have created as a syphon of public funds from sovereign space. Whereas the imagined geography of Utopia offers a site for reflecting on economics as a custom, and policies not only of the redistribution of wealth but the common use of the land and best customs of justice, the growth of the offshore has, mutatis mutandi, become a negative example, but an example nonetheless, for the institution of tax exemptions that universally subtract from the public good and a global conceit that undermines the authority of the sovereign state–and how states can meet the social needs of their inhabitants in the manner that laws on the island of Utopia allowed.

New offshore spaces of alternative societies and world offered More, famously, as a riff on the discussion of the state. Vespucci has described an expanded offshore in that provided such a fascinating glimpse of “novae insulae” as alternative governments and societies, echoing the lost island of Atlantis. These islands were sites of differently scented flowers and abundant metals, whose native inhabitants went without clothing, and seemed to lack names other than those which the European visitors bestowed on them as new offshore spaces of potential wealth as sites of trade and sites for mining precious metals, but also new spaces for negotiating good government, even if the early practices of the colonialization of offshore valued the forms of good government discovered on these new islands than the best ways of appropriating goods from this new offshore world:

Once clear lines drawn between the inland and offshore, in More’s imagination, defined the different natures of the settled world from the sea for European mapmakers, and transatlantic travel focussed largely on the settled coast. The fascination of the offshore is preserved in cartographical records–that largely focus on the shoreline. Although several Pacific archipelagos formed their own notions of mapping inter-island navigation by winds, currents, and seas, terrestrial mapping was oriented around its shore. In an age of globalization, the newfound prominence of the offshore in the spatial imagination rehabilitates extraterritorial islands and tax asylums as sites that attract capital, as well as tourists, in a particularly disquieting pull of the financial gravity of global finances that has the effect of subtracting social services in inland states; rather than exist for their denizens, the offshore only gains reality as a fiction for the financial circuits of multi-nationals, but trumps whatever curiosity the offshore long held.

10. But in the slipper map of global finance, capital flows are routes removed from the interests local inhabitants; the places of the offshore rarely appear on the map, but create a buzz of capital flows that bend borders or seep across frontiers of the global economy where money escapes from government or from good governance.

Such offshore sites are rarely mapped because of their remove from the monitoring of financial movements and information allows them rarely to be seen in aggregate–because they lack any coherence or continuity of their own, and exist as legal fictions to store and secrete huge monies or funds. The dramatic multiplication of sanctioned sites to preserve a resting place for profits or funds reveal a sense of place that exists in radically different ways. Indeed, the sanctioning of the offshore suggests a bifurcation of conventions for its inhabitants and the investors or shell companies, anonymous corporations and almost fictional banks, that replicate the power structures of a colonial world in a post-colonial present, particularly terrifying for how they attract the wealth of post-colonial elites.

Although offshore sites often have few actual physically present residents, offshore entities are legal fictions whose attraction as places exist on paper, juxtaposing several spaces in a real place that is often always less accessible to their actual inhabitants but exists for multinationals and the super-rich. And as income inequality has emerged as the defining issue of the post-9/11 post-Cold War post-American hegemony world, the unmasking of the offshore as a site of pervasive criminality that goes beyond evading taxes, but a system of bending sovereign laws for criminal and corporate interests, allowing multi-nationals, mafia members, corrupt politicians, drug dealers, and the super-rich to evade national laws in ways that undermine any social confidence in nation states–or in the equality of tax laws. But even as whistle-blowers and activists have opened troves of digital information to expose wrong-doing–as in the Panama Papers, the cool reception whistle-blowers face within the press and from their own countries suggest the deep desire to retain cloaks of secrecy about such hidden dealings that perpetuate deep inequalities of wealth.

If they are the actual ancestors of utopias–places with no real place, save on the map–the heterotopia of the offshore are actual places organized by legal proclamation and consensus, but which don’t exist on the map; they are the remainder of the post-colonial world which serve the interests of the logic of big capital, in-between places removed from the map of tax sovereignty, or territoriality, which enjoy an ambiguous position in relation to spatial continuity. Whereas the islands of the offshore are often seen as endangered spaces, removed and remote often overlooked details on maps–