The territoriality of the Gaza Strip continues to fascinate for its levels of history and to confound for the grounds of its destruction–as destruction seems to erase any claims for actual sovereignty. For while the claims of territoriality and sovereignty are deeply intertwined, the Gaza Strip being occupied by Israel but being destroyed for its claims to territorial autonomy–the Gaza Strip has become the focus of global frustration and a case study of the disproportionate military response. If the invasion of October 7 seemed a case study of the entry of cross-border munitions into an enclave that seemed isolated by naval and ground blockades, the unprecedented scale of airborne attacks seeking to dismantle the organizational networks of terrorist groups who launched the bloody invasion has provoked new questions of mapping–mapping the scale of destruction, the ethical limits of destruction of infrastructure and historical buildings of sacred import, and indeed the Palestinian landscape by which Gaza was defined as a legacy of ancient Palestine of Canaanites and on the southern plains of the Mediterranean, long renowned, paradoxically, for its ability to resist invasion and assault. For, far beyond the maps of bombings, military presence, and fatalities or damaged property can suggest, Gaza exists in a cartography of the covenant, and a map of Abrahamic covenant, in which the given worldly laws and legal territorial boundary lines are moot, and a contract of covenant trumps the variety of temporal laws that have been drawn around it.

In an era of web maps, this post will risk suggesting, we might be expected to be able to discern and be familiar with the variety of layers of a worldly map, in which the covenential contract Abraham won promised a land, even if one which he would not see revealed or mapped in the limits of his life, for his seed, an inheritance whose architect was God, who would no longer “live like a stranger in a foreign country,” but his seed, even if his wife was beyond child-bearing age, was a metaphor for Israel, were indeed “longing for a better country,” where they “had opportunity to return.” The continued occupation of the Occupied Territories could not, in a sense, be rendered by geopolitical maps as an occupation, so much as they reflected an Abrahamic inheritance that affirmed the pious intentions of Abraham “to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance,” and Gaza was a site from which the sovereignty of that inheritance was able to be threatened. The eternal nature of this contract of covenant was a deep cartography of sorts that underlay the phenomenal maps of the destruction of buildings, death of civilians, which are almost epiphenomenal before the deep existential conflict Benjamin Netanyahu imagines between himself and Hamas’ leaders, and a still deeper contractual covenant between Israel and the God of Abraham. Yet how to justify or balance the maps of bomb damage, so destructive even if epiphenomenal in the grand scheme of things, with the conceptual reality of the covenant seems to lie at the base of the ongoing bloody conflict as much as how lines of sovereignty and jurisdiction are to be drawn or redrawn on the map of the Middle East port city of Gaza.

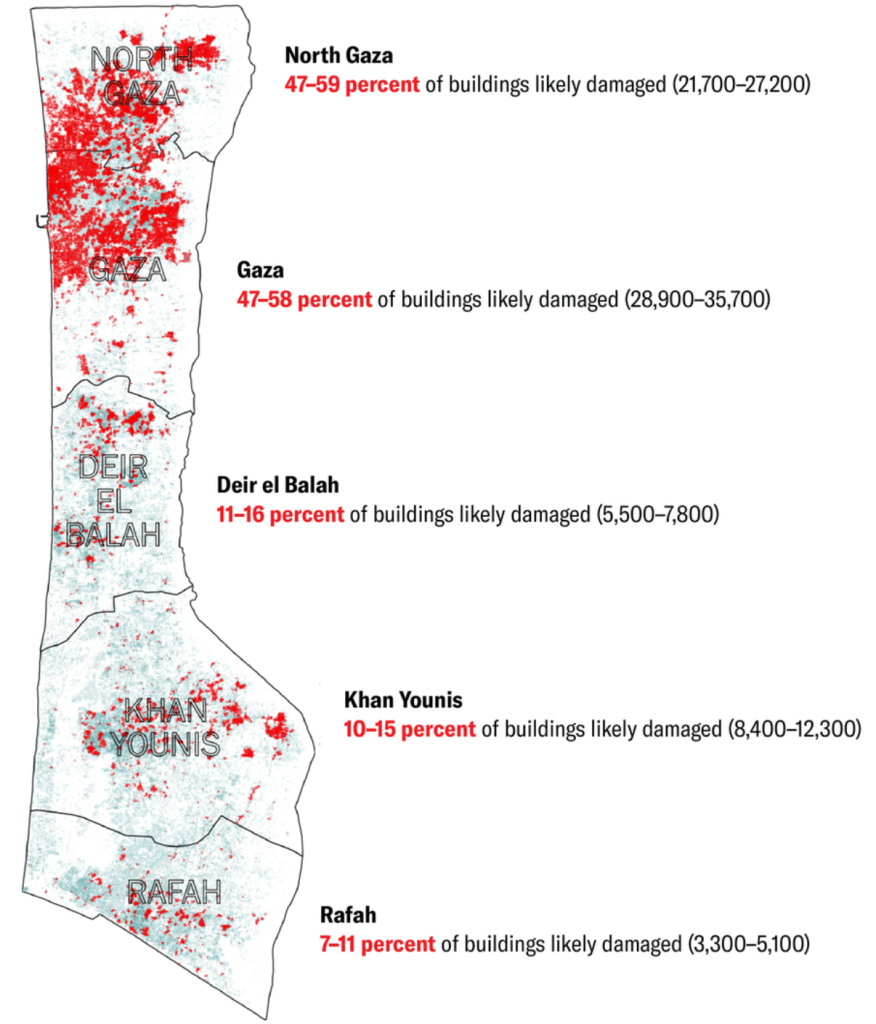

If the boundaries of the Gaza Strip were defined as a Palestinian enclave, it is not clear if it will ever be part of a Palestinian state, and the place of Gaza in the Israeli nation has come to a head as a crisis of sovereignty, and we try to grasp the scale of buildings across the Strip have been destroyed in attempts to destroy and eradicate the terrorist network who invaded settler communities so brutally, relying on satellite data as news coverage is silenced on the ground, as much as we can tell from Decentralizerd Damage Mapping Group, hoping to secure a sense of objectivity and transparency in a region that is riddled with national biases and national news.

Buildings Damaged or Destroyed per Satellite, October 5 to November 22, 2023

By January 5, the destruction of buildings in North Gaza had risen to 70-80%, or up to 40,000 buildings, and 70–80% of the Central Gaza Strip, making one wonder what sort of sovereignty can exist over it, or how the extent of its infrastructure’s destructino has obliterated its territoriality.

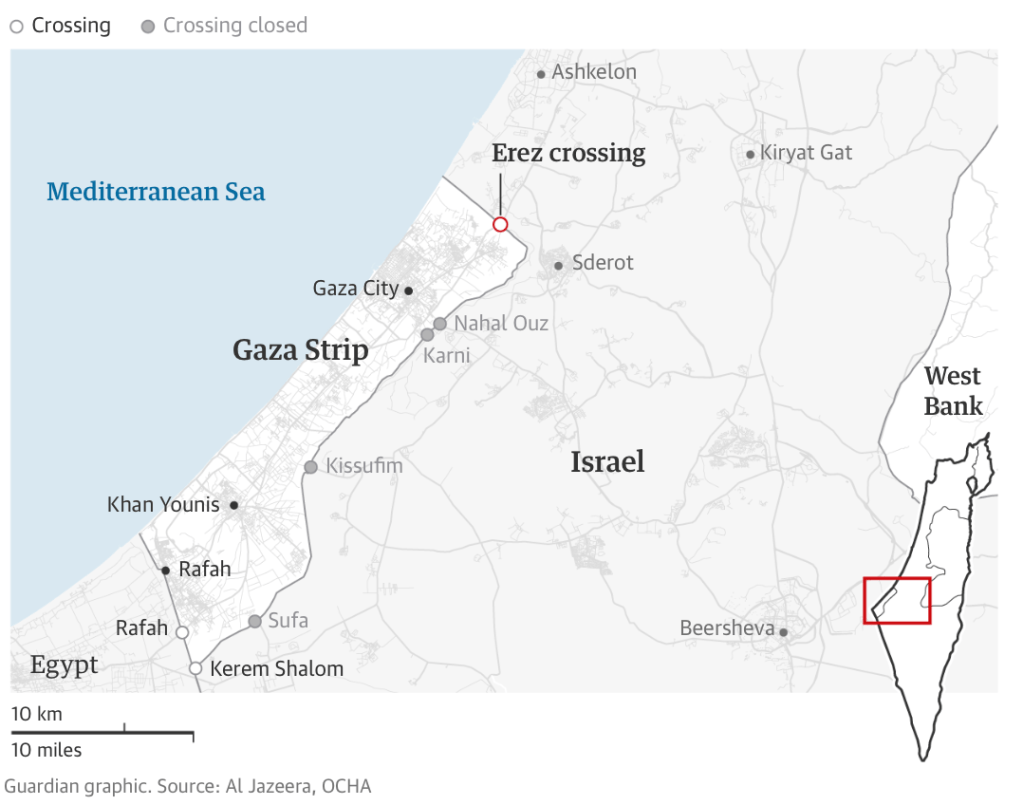

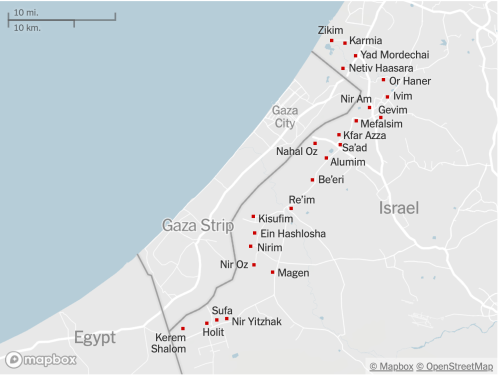

What sovereignty exists over the territory that is at risk of being one of the major humanitarian crises of recent years? The crisis was pressingly stated by the murderous if not barbaric invasion of October 7 that ended the peace Israel has established at great cost in the so-called “Gaza envelope.” And they are at a head in large part due to the asymmetrical relations that have been created by the boundary, constructed at great expense within the state of Israel, at its perimeter–the very area where the incursion of terrorist groups, armed with that led to the ground invasion with grenade launchers, assault rifles, and light machine guns as they entered the Palestinian enclave.

If Gaza is a remainder of Palestinian settlement, amputated from Israel, but a sort of ghetto resulting from the expulsion of Palestinians new state of Israel, it is a twin of the foundation of Israel. Its lack of sovereignty is a negative reflection of Israel’s sovereignty, and has shrunk as the Israeli nation has been defined for the Jewish nation, rather than for Palestinian presence, and has refused to incorporate the future of a Palestinian state. Instead, the Gaza Strip has been set apart, and physically bounded, to illustrate Israel’s longstanding control of this border, around not only the Gaza Strip but the geographic creation of the so-called “Gaza envelope”–the securitized perimeter of Gaza, or עוטף עזה, premised on an absence of sovereignty in relation to Israel.

If Arab-Israeli Wars were admittedly central to the emergence of Israel, it is the denial of political status to its residents–ostensibly still members of the Israeli state, if one can believe it–who are denied sovereign status. The denial of Arab sovereignty is crucial to the Gaza War, which risks foreclosing a hoped for “two-state solution” it may consign to the dustbin of alternative history, but cordons off the perimeter of the state. The layers of the data visualization that cannot suggest the boldness or bloodiness of an invasion that led to the “peace” of Israeli civilian settlers being openly violated, violently raped, killed, or mutilated in what seems a truly orgiastic violence that left 1,200 civilians dead, was more than a push-back against containment within a perimeter.

It was a denial of sovereign rights to possession, and indeed a slow tightening of a grip that refused the importation of gas, water, goods, or indeed medicines into the Gaza “Strip,” a name whose belittling of territory and territoriality is almost itself an insult to the sacred nature of the mosques and shrines that exist on its historical land–only six shrines of a former remaining standing after the pummeling of the Gaza enclave with aerial bombardments of 2016, and over two hundred archeological sites of public memory–ancient churches, mosques, Byzantine architectural monuments–have been destroyed by late December, 2023, per the Gaza Media Office and Middle East Report; by the start of 2024, the Anthedon of Palestine, Byzantine church in Jabalia, shrine of Al-Qadir in the central Gaza Strip, as well as the Greek church of St. Porphyrius have been destroyed. Is this a desire of revenge for the desecration of Jewish synagogues in Gaza City, structures set to fire or exploded by Palestinian residents of Gaza after the October 2005 withdrawal of Jewish settlers left the structures of some thirty synagogues in Gaza City intact that had been built during the occupation period, after removing their ritual books, scrolls, and sacred materials? Arguing that these were not holy structures, but empty buildings without any use, Palestinian Authority decided the assertion of any damage to the buildings would violate Jewish law was derided as a provocation, but their bulldozing was attacked as a “barbaric act by people who have no respect for sacred site,” rather than a reminder of the occupation. The blurred line that led Palestinians to reject their conversion to mosques–a proposal of a Bethlehem rabbi–touched a nerve, as it was feared that doing so would lead to the return of Jews to pray at the al-Aqsa mosque.

The apparent intent of destroying Gaza’s infrastructure has destroyed its public memory as collateral damage. Although raids have revealed a seaside bomb manufacturing site of Islamic Jihad confirm the extent to which Hamas and other groups have used mosques and hospitals as sites for storing weapons and concealing weapons manufacturing sites–the logic of destroying mosques seems a destruction of public memory and preparation that the Israeli Defense Forces have argued since 2014 has only escalated fears inclusion of the Gaza Strip within Israel’s sovereignty, and a need to secure and expand Gaza’s own borders–a longtime delegitimization of the very ability of Hamas or of Palestinians to be protectors of Gaza’s immense cultural and religious patrimony: ”For Hamas, nothing is sacred,” not even the preservation of their historical heritage and legacy.

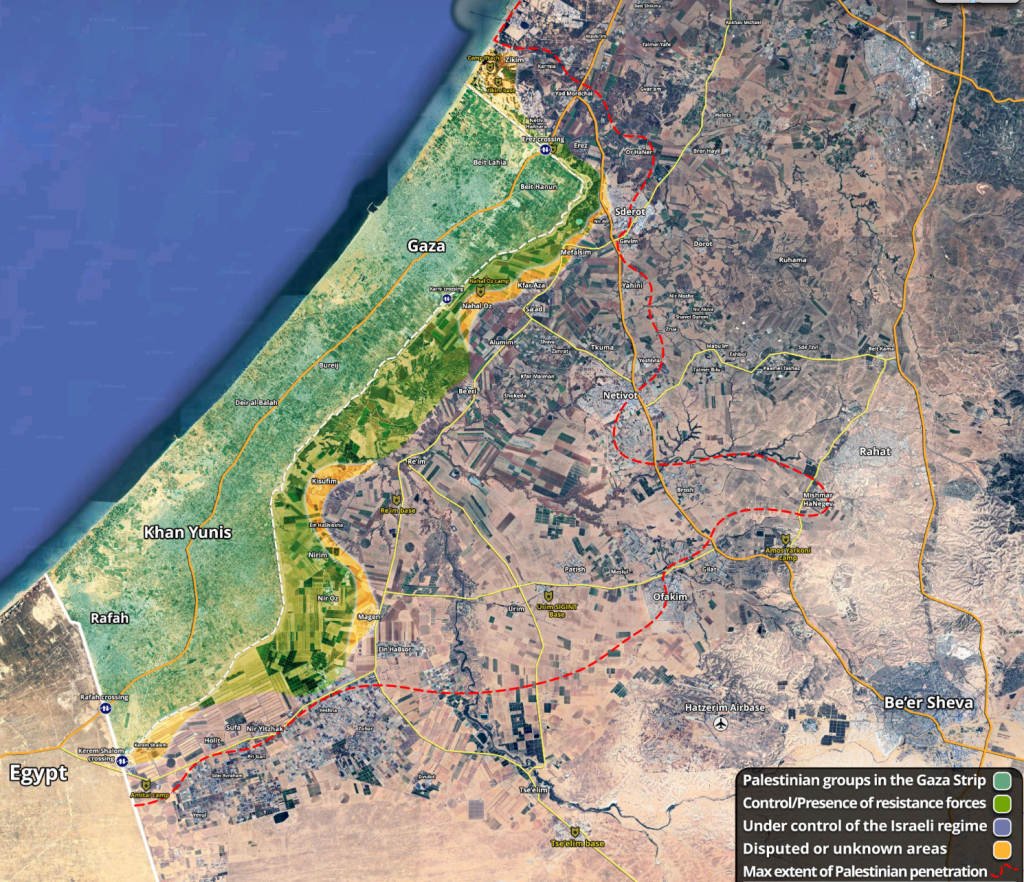

The invasion of the Gaza Strip has advanced a blanket denial of sovereignty to its residents. If Israel has controlled Gaza as an edge of the state, monitoring since the withdrawal of Israeli troops from the region in 2005, almost twenty years ago, its airspace and marine ports, as well as entry and exit to the region, it has pointedly denied the health or well-being of the enclave’s inhabitants. The provocative concerted violation of the boundary barrier around Gaza Strip was intended as a shock attack that was itself a shock, that was even more violent a shock with the murders and hostages that groups allegedly tied to Hamas took, was not only a loss of life. And the scale of that invasion, marked in a ghostly manner in this map of the Israeli Defense Forces invasion of the Gaza Strip’s autonomy as an enclave of Palestinian identity in this intelligence map form Islamic World News, as the blue arrows of Israel’s armed forces entered four crossing points on the Gaza Strip perimeter.

The shocking realization the “envelope”–a military construct, but also a psychic shield–had been so violently pierced, towers of surveillance hit by unmanned drones and the boundary of safety that created over almost twenty years around the Gaza Strip broken, created a tectonic disruption of the strategy of containment from which the Israeli state will be psychically recovering for years, and has offered the unimaginable fictions that terrorist cells peddled to the hostages the they took of Israel’s actual destruction as a state.

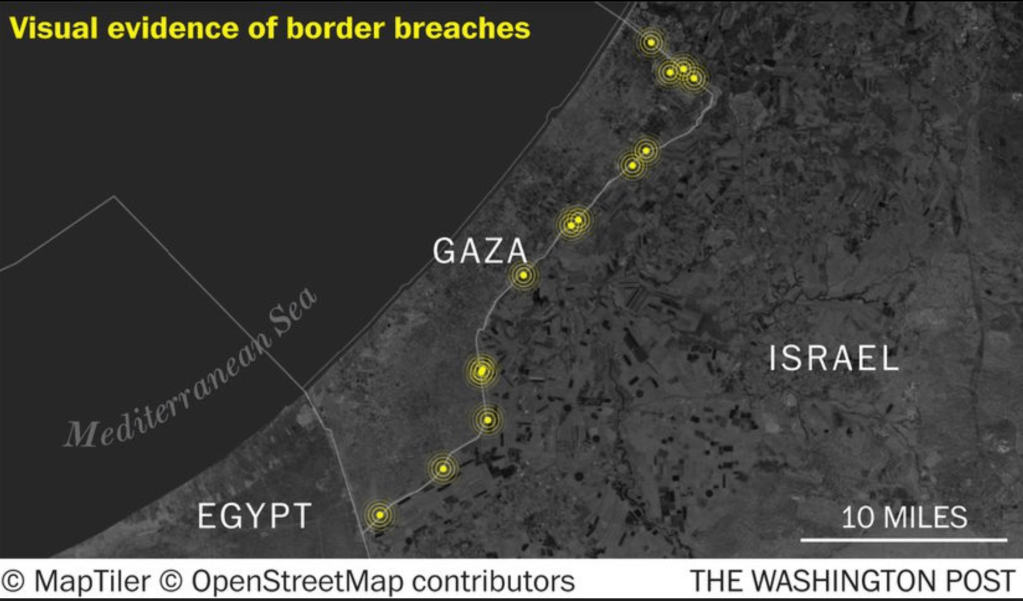

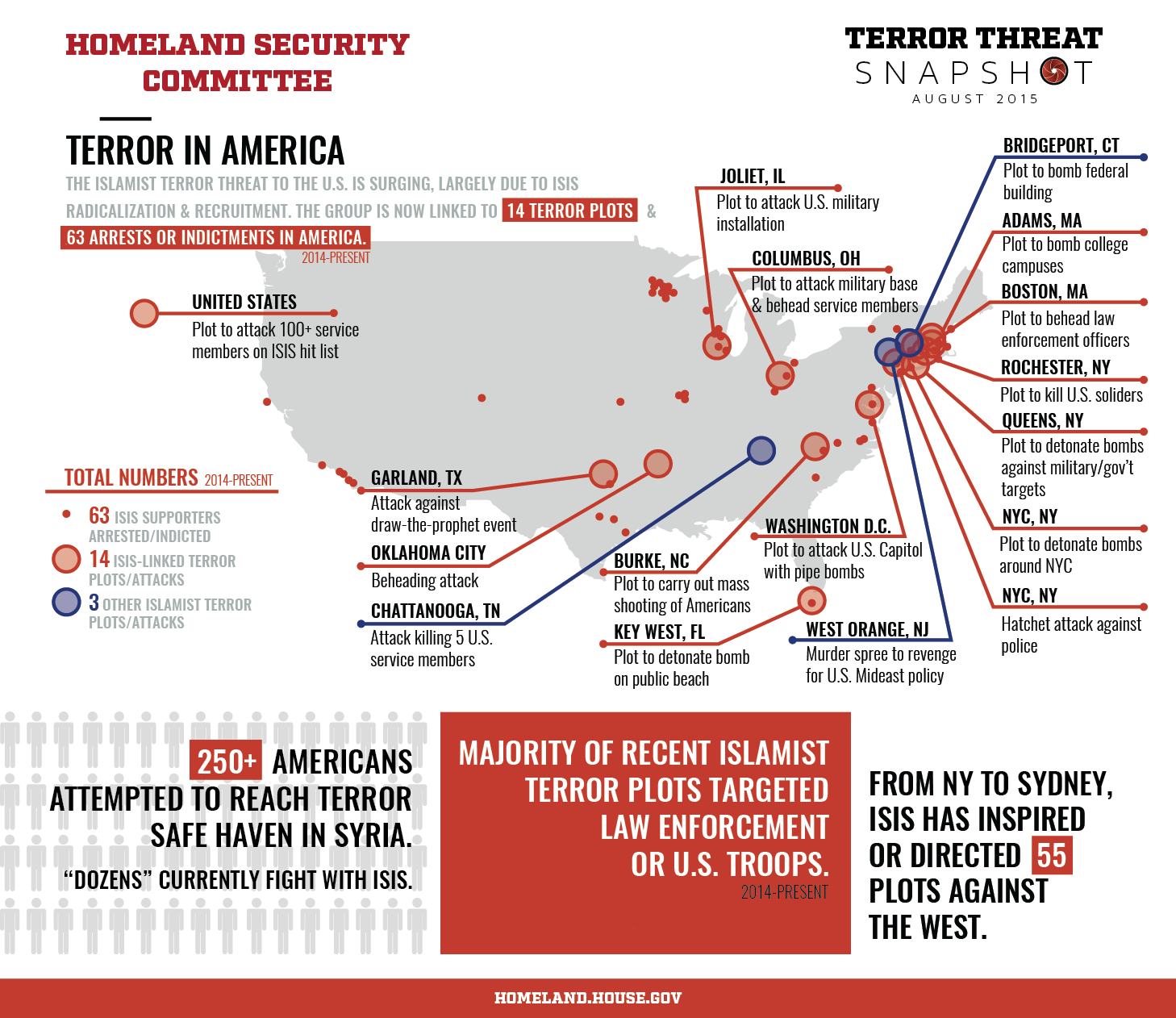

Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu rather darkly jingoistically proclaimed the Gaza War “a second war of Independence” as a rallying cry to unite the nation, telling the nation after massive aerial attacks began that the air offensive was an offensive “only at the beginning.” The elimination of an enemy that had made mosques, hospitals, and private residences as military installations–and insisting, as the platform for his party has declared its role in protecting Israeli sovereignty “Between the Sea and the Jordan,” as if to rehabilitate hard-line scriptural geography of protecting all Israeli settlements in nominally Palestinian territory. In piercing the barrier around Gaza in over thirty sites, the raids overwhelmed border technologies, the beneficiaries of a growing arsenal of cross-border attacks, by no means limited to Hamas or to the Middle East,–even if they are compellingly mapped as a local attack.

But the attacks can only be seen in global terms–both in the arrival of arms to Hamas ferried across underground tunnels, and long stored as they accumulated as a hidden arsenal of attack, and the fuel for a cataclysmic struggle that the al Aqsa Flood promoted itself to Palestinians, as a campaign of vengeance and global destruction that would overwhelm Israel and Jerusalem at an apocalyptic scale. The concerted cross-border attack used a new range of weapons–unmanned arial vehicles (UAV’s) or kamikaze explosive drones to undermine the very technology of monitoring the border that the Israeli government constructed as an impossible border, a structure repeatedly praised as an “iron wall” against terorism that had fostered some quiescence by its high tech appearance.

The conflation of the 2.3 million Palestinians that the IDF had blockaded into Gaza Strip with independence seemed perverse, but the cordoning off of Gaza was tied to Israel’s birth, and it was undertaking a massive ground war against “the enemy”–Hamas denied Israel’s right to exist on the map from its founding charter, committed to Israel’s removal from maps of the Middle East. The extreme violence of the cross-border attack that left 1,400 dead, was enabled, this post argues, by the new nature of cross-border war–the technologies of border warfare that were used to clear any Israeli claims to the land from its 1988 Charter, including to construct a border. The construction of the preventive barrier seemed to amputate Gaza from the well-being of the nation, filling the Likud party’s new Charter rebuffing the Palestinian demands for a recognition of their presence on the map of the Middle East by openly resolving that “Between the sea and the Jordan there will only be Israeli sovereignty.”

This reiteration of a scriptural map rehabilitates hard-line Zionist beliefs to refuse accommodation, imagining Israeli boundaries apart from a Palestine presence. In this geographic imaginary, the separate sovereignty of Gaza and the West Bank do not even merit mapping, but could only be permitted behind an actually impractical and costly architecture of boundary walls.

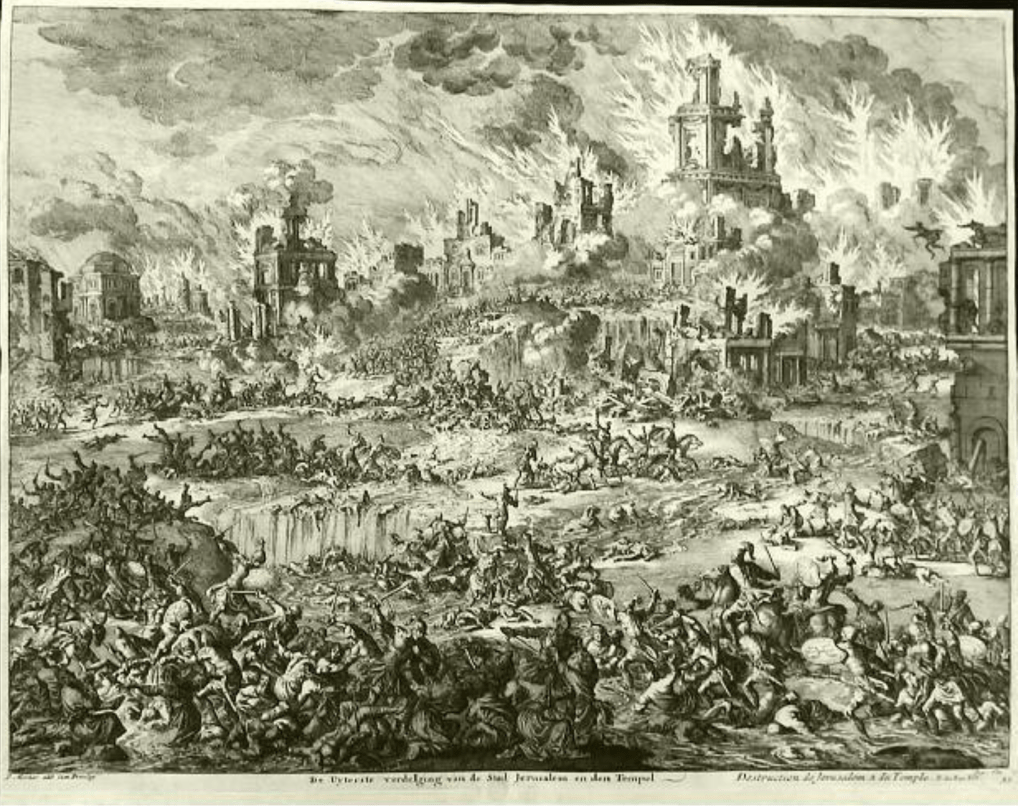

For perhaps the most terrifying aspects of the Gaza War is the juxtaposition of technologies–the barbarity of the murders and the military technologies of death. Those technologies had pierced the perimeter that Israeli Defense Forces had so carefully built, and entered the state of Israel that had been nominally and notionally securitized, a bulwark in the desert. And as much as the death of so many civilians and military shocked, disturbed, enraged and maddened, the nature of the attack that overwhelmed border technologies was a sort of wake-up call that also warned Israelis, in critical ways, of the range of armaments that had indeed entered the Gaza Strip. As the search of the Gaza Strip has confirmed, with its range of anti-tank missiles, the tanks that guard the perimeter of the Gaza Strip are not invincible bulwarks against the Al-Aqsa Flood or the deluge of armed Palestinians; the image of a full-scale destruction of the Israeli city of Jerusalem was less an actual target, perhaps, of rockets, but a motivating cry to urge border-crossers to cross into Israel, armed to the teeth, to unleash a level of violence more unnatural as Hobbesian state of nature.

Their deep success, if it can be called that, in penetrating the Israeli psyche, both by taking hostages and violently killing civilians, in ways somehow were not monitored or guarded against, that a range of weapons had arrived in the small enclave through its tunnel network–bombs, missiles, long-range rockets, and the particularly disturbing innovative cheap tools of attack drones, that allowed the incursion into Israeli territory by the new dotted red frontier of Palestinian advances into the land that seemed “settled” by kibbutz. And it called into question the project of kibbutzim that had devolved or evolved into tools of what might be called frontier settlement.

The desperate coloration of Palestinian presence in the Gaza Strip by bright green to denote presence and resistance of Palestinians in the enclave was mapped onto its topography, in a decisive act of cartographic settlement and naturalization. How did the narrow territory of the Gaza strip, which lacks sovereign status, become conflated with independence of a sovereign state? T

he “envelope” or perimeter around the Gaza Strip was after all a cartographic creation of Israel’s independence, a consequence of the Palestinian Nakba, or removal from Israel. The presence of Gaza at the intersection of tectonic plates moving apart have shaped its borders more than scriptural precedent or sacred archeology. Gaza has become an “edge,” however, of geopolitical contestation, idriven by longstanding and building historical tensions is concretized by the architecture of the border wall that have bound the Gaza Strip. For the border has been engineered both as an architecture constraining movement and its architecture of regional sovereignty.

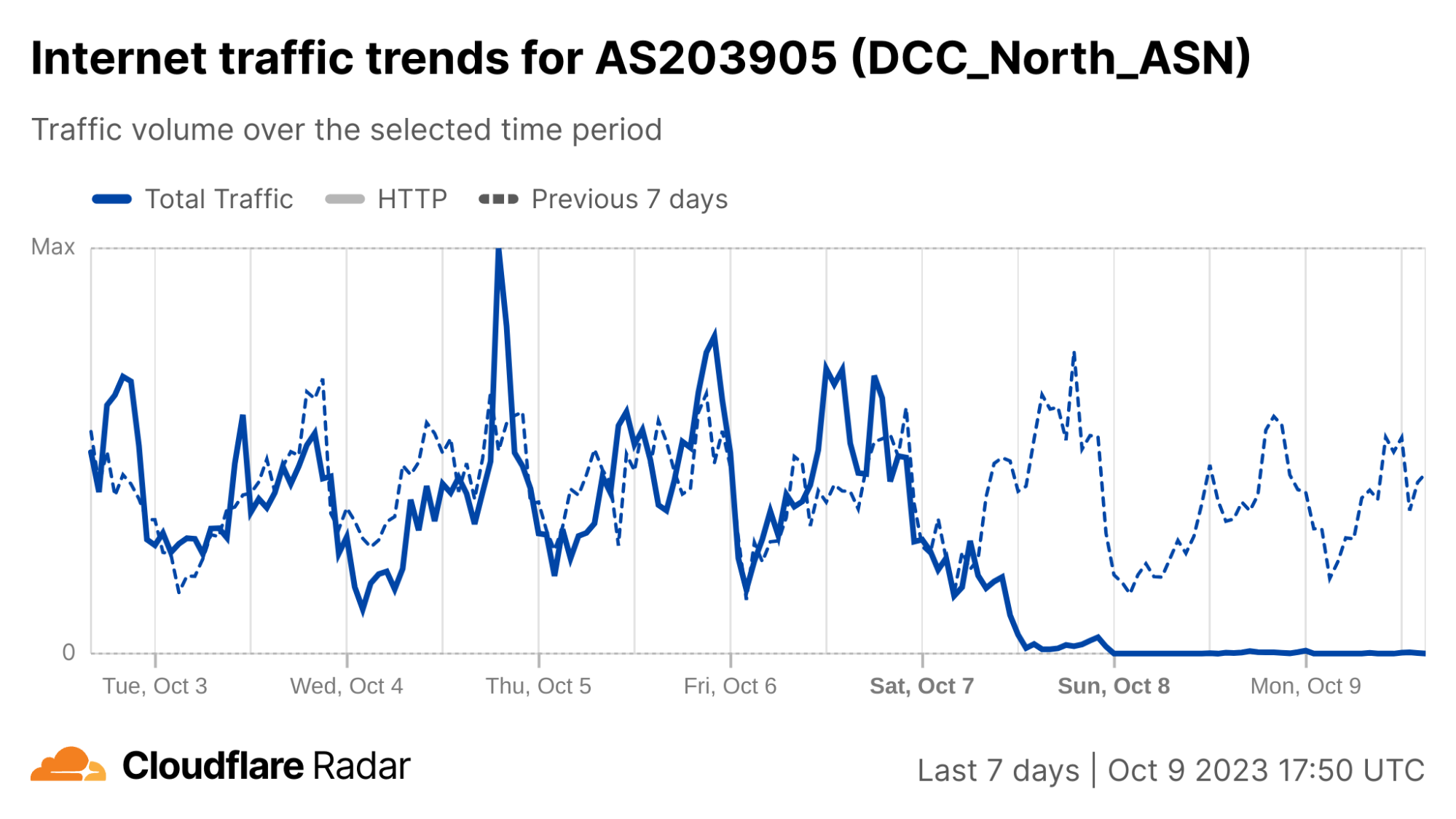

The perimeter technology has been sealed, as a walled-off region. Cut off from electricity, energy (paralyzing hospitals, desalination plants, and business), Gaza is perhaps one of the only regions of the world that is now offline, and off any grid, internet access cut as well as access to ocean fishing, as mobile and IP cell towers are felled, allowing one of the most densely habited areas of the world to become more isolated from the world, as internet traffic flatlined for 2.2 million, before guiding to a halt by late October 27 to make it one of the least active in the world, more like Antarctica or the African desert, rather than one of the most densely populated areas on earth.

The internet shut-downs appeared part of the war of aggression not only as a news black-out, but to cut off Gaza from the world by cutting off its internet connectivity, suddenly ranked “poor,” per the nonprofit Internet Society, a forced impoverishment as punitive as its aerial bombardment. The scale of damage or destruction of over a third of buildings in Northern Gaza suggest an even deeper flatlining of civic life. This is a register, a record, of what life behind the border wall, that may well make use think more about what it meant to stand before the border wall.

Even as Israeli troops attacked the enclave from which Hamas, whose military wing staged many rocket attacks and bombings in Israeli territory since the 1990s, the lack of any sovereignty suggests a troubling para-territoriality of Gaza. As Gaza, a historic region, was reduced to an enclave without sovereign authority, it stands apart from Israel’s nominally pluralistic society. What was once seen as a frontier–and indeed was cast as a frontier of settlement as Israelis settled the southern edge of Gaza–has become monitored by airspace and at sea mapped from its confines at the edge of the state. This edge became a gaping hole in the architecture of border defense.

The audacious border-crossing from Gaza demands attention not as a frontier, as Hamas seemed showed the world that it could cross the sophisticated boundary forces worked so hard to secure, as they dismantled the sophisticated equipment at the border and bases closest to it, shocking the Israeli border control apparatus forced to repair observation towers and to rebuild fences to secure the compromised network of seniors, radar and cameras that make up the border zone.

The surprise attack on Israel were shocking breaches by which the military wing of Gaza affirmed a porous relation to Israel, and defined by brazen violent crossings of its “border,” suddenly not a frontier, but a region that could be openly crossed. Although Gaza is nominally governed by Cogat, the responsible organ of Israel’s military authority that governs Palestinian occupied territories–it exists as only occupied as a frontier, existed for Israel entirely as an edge that was secured by the state, across which any movement of people, goods, energy, water and equipment are restricted: and with 97% of the enclave’s water undrinkable, rolling energy black-outs, and restriction of wifi communication, the marginality of the enclave is becoming normalized more than its presence. When Israel’s new war cabinet declared common ground around a determination to “wipe Hamas off the earth’s map,” they were adamantly responding to the commitment of Hamas “to wipe out Israel” to be sure–“we won’t discuss recognizing Israel, only wiping it out” said Yahya Sinwar.

The global scale of this rhetoric of cartographic cancellation has grown as the fortification of the border has grown, under-written by interests of national security, as Gaza has been supported by Islamic states–and a new range of cross-border missiles and drones, mostly tied to Iran, if with ties to weapons merchants trafficking in arms and unmanned aerial vehicles made in South Korea, and UAV’s made in Tunisia as well as Russia. For the Gaza War has become a global war, rooted in new means of cross-border wars. We cannot reduce the war to a conflict between Israel and the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades. As much as this conflict has been mapped, rooted in the network of tunnels beneath hospitals and refugee camps bombarded by Israeli Defense Forces, to do so ignores the rise of a new nature of cross-border warfare that inspired the conflict, allowed it, and has increased its intensity. The rise of-a rhetoric of cartographic obliteration is rooted in the global triumph of Islam, to be sure, but a new inflection point of geopolitical tensions. (So much is revealed in the distasteful image of a snake, whose skin is of the color scheme an Israeli flag, that wraps itself jealously around the globe, a concretization of a trope of jewish globalism embedded in anti-semitism in the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion, posing as a revelation of secret Jewish rites: the tired tops of Judaism as a globe-devouring snake bent on global conquest was familiar:

Protocols of Elders of Zion (London, 1978)

The Protocols were a forgery, but had unsurprisingly won a second life in the Middle East, the alleged plans for global conquest adopted to attack the attempts to settle what were mapped as Palestinian lands. The false tract that revealed secret agendas was endorsed by Gamal Nasser and Anwar el Sadat of Egypt, and has been adopted from Iranian Revolutionaries to Hamas, as well as Islamic Jihad and Palestinian National Authority who have included it in their own school syllabi–it was even sold on iTunes in 2012! The charge of global domination was any easy and dramatic visual gloss of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and constraints around the Gaza Strip, rather grotesquely repurposed to center a globe encircling snake around its actual geographic location.

Detail of Recent Anti-Israeli Reiteration of Stock Anti-Semitic Trope Distributed Online

The photoshopping is a crude map of the illegality of Israel’s pretensions to include the deserts of the Sinai–or Egypt–in its territorial claims. It is uses a rhetoric of globalism to magnify the affront of a securitized border. But the built boundary perhaps promises to be a blockage of any future movement toward negotiation, as my previous post argued. There is a literal sense in which it is true: for the Hamas invasion of October 7 existed off the map of Israeli sensors, by wiping surveillance systems off the border map that IDF had patrolled, to sew massive disorientation across the nation by disabling security systems.

The Israeli government had for too long removed Hamas from its map of military intel, believing the group to be safely sequestered and confined behind a secure wall, not needing to be mapped. The divergent realities on alternate sides of the border wall. This is no isolated cross-border attack, but a sign of the danger of future attacks: as Hamas officials, even after the bombardment of the Gaza Strip, have predicted future attacks will continue “again and again until Israel is annihilated,” this is a new gambit of cross-border war.

Both, of course, had relinquished hopes of negotiation, and devised strategies to remove the need for ever attending to their neighbors, but that is another story than this post can tackle. To reduce the conflict to a polarity–as if the military organization locked in eternal warfare with Israel, crying, with Samson, “Lord God, remember me, give me strength one more final time to punish these Philistines for tearing out my eyes!” even risking their own death–bears down too closely on the geography of the Gaza Strip, and ignoring the power of what it means to stand before the Gaza Strip’s boundary,–not as a frontier, but as a different reality, that made residents of Gaza so deeply committed to the rhetoric of annihilation, and the liberatory nature of rebordering, an al-Aqsa Flood that claimed Palestinian territory “from the river to the sea” would, as Israelis understood it, activate an image of erasing Israeli sovereignty from the Jordan to the Mediterranean. But if the October 7 invasion of Israel seemed an attempt to advance beyond Beersheva, and unit the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, the polemic charge of the slogan had been festering as Israel governments had claimed their own rights to claim full sovereignty over the same area, as if two overlays on the map were competing with one another, flickering with an intensity to drive the observer insane. The flattening of space3 that

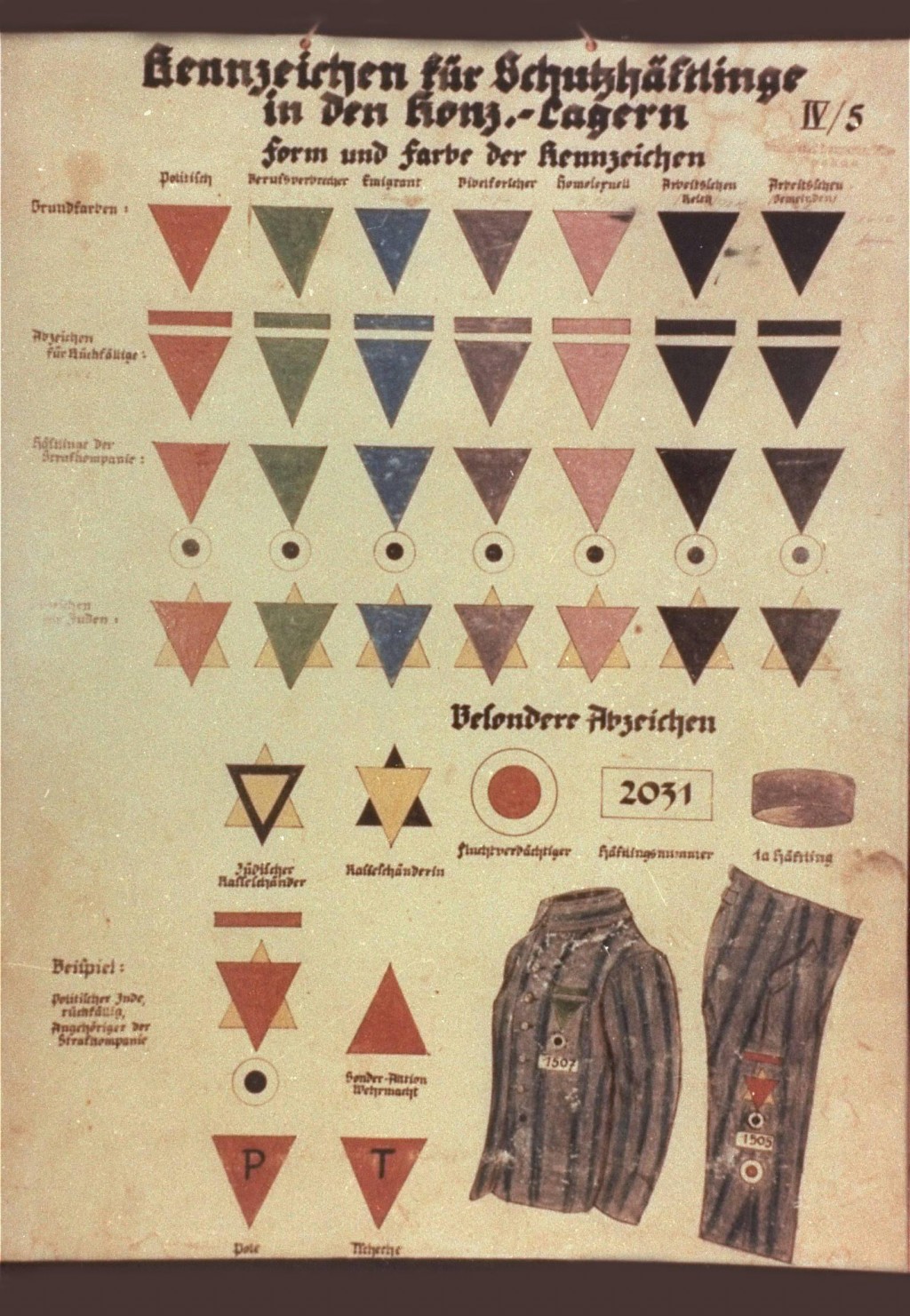

The cartographic flattening of on-the-ground realities in both visions have created an untenable situation, a flattening that was perpetuated in the broad strokes of the accusations of genocide, and the identification, however unwarranted, in the United States, of a president navigating difficulties of the alliance with the Israeli state, to what is best understood as the hashtag of #GenocideJoe, as a way to open eyes about the complicity of the United States within Israel’s invasion of the Gaza Strip, first by American Muslims for Palestine, and then via the Electronic Intifada Podcast, streamed a vision of Zionism = Fascism, and legality as a concept that must blanket immigrants, gay rights, transexual rights, and equal schooling, as if it rested in a uniform colonial mindset that might be mapped around the blood red cartographic sigla of the Israeli State–

Chicago, Illinois

–and blaming “Genocide Joe” and “the Democrats for allowing this genocide to happen”–even if boosting the invasion and bombardment as a genocide risks making a caricature of a deeply evil assault on an entire people, seeking to exterminate them in totality, as much as stage an expanded invasion of the perpetrators of an actual crime. The odd taking of President Biden with an upside down triangle of a political opponent suggest a transposition of categories or categorical confusion.

For the dual bifurcated realities that emerged on each side of the barrier were difficult to sustain. Gaza is not only cordoned off from prosperity, but a region which faces over 40% unemployment–now approaching 50%–and levels of depression and economic stagnation unimaginable in any western country or any developed nation. For many of those with jobs, the onerous task of crossing the very few open border gates to enter the parallel universe that exists nearby, in Israel, that in fact transcends the ability of some to even communicate to their families: they have visited Jerusalem or other cities, have even seen the historic al-Aqsa mosque after which the invasion of the occupying power was named and consciously intended to evoke; their experience of the border is not often in our maps, but they evoke an imagined voyage to Jerusalem in their war of liberation, freeing al-Aqsa and indeed fomenting an uprising called the “al-Aqsa flood,” xعملية طوفان الأقصى, with good reason–conjuring a biblical flood that would rise from the outpost on the Mediterranean, one able to wipe away the stark differences in the divergent realities in which many live as a motivational charge. The cleansing image of the “flood” narrative to return the region to a primordial chaos, able to remake reality for the righteous, and wipe away the violent nature of a painful chastisement that would not “leave upon the land many dweller from among the non-believers” who will be drowned because of their wrongs was an illustration of the need to fear the greatness of Allah in the Quran, remaking the global geography by opening up expansive pathways.

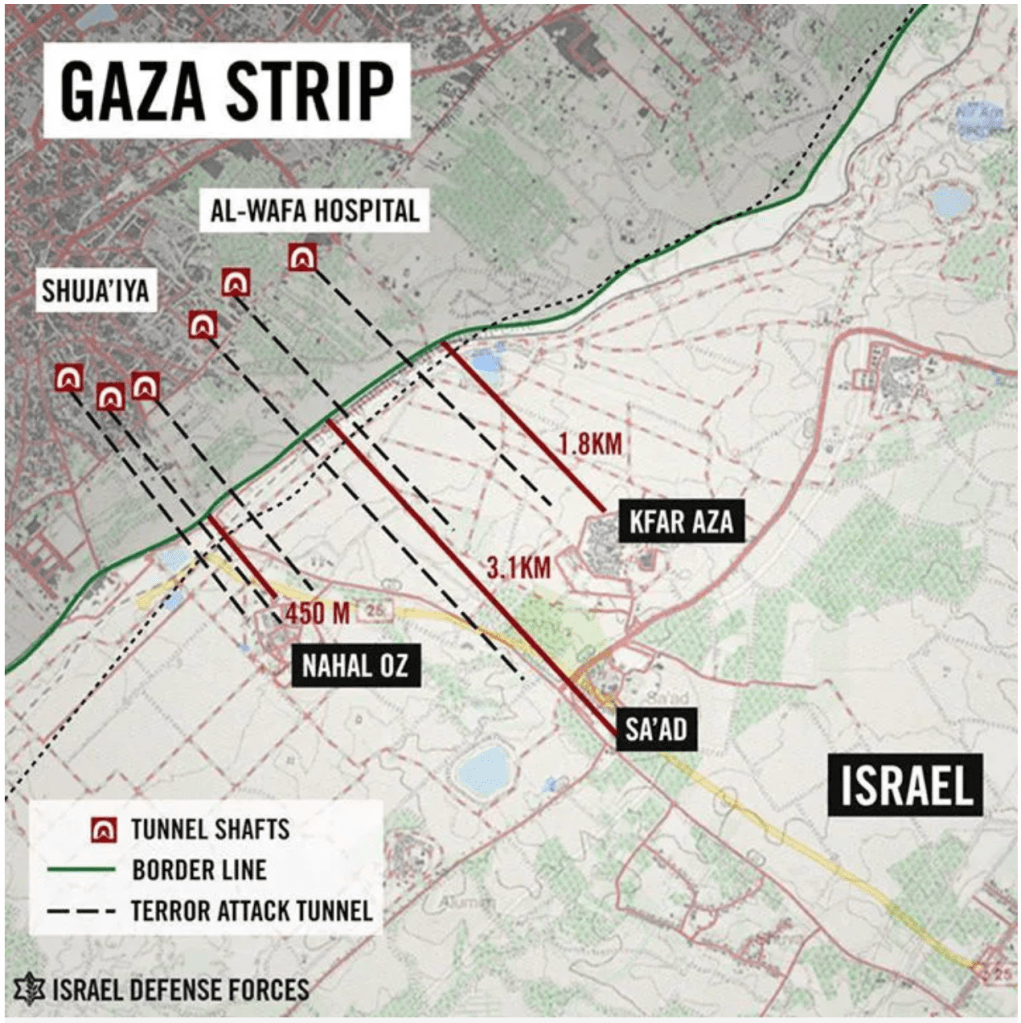

This was far more more than an energizing rallying cry. The opening up of “wide pathways” in a “wide expanse” was a reaction to the absence of connection between Palestinian lands, the enclaves that were once imagined to be linked by underground tunnels, nourished in the labyrinthine structures of a tunnel network that expanded in Gaza built from when Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, outside of the surveillance of Israeli government, some two hundred feet underground, eluding GPS surveillance systems, a site of resistance whose network stretches for miles beneath not only refugee camps, mosques and hospitals but contains rooms, chambers, and passage-ways hostages are held and arms stored. If the apparent carpet bombing of Gaza City was reflected that the groundplan of IDF military offensives in Shijaiya or Beit Lahiya to search for the captured soldier Galid Shalit taken as a hostage in operations that Prime Minister Netanyahu called “necessary to the security of the Israeli nation.” The military’s prioritizing of destroying the tunnel network was reflected in how military spokesperson Eytan Buchman a decade ago explained “all of Gaza is an underground city, and the amount of infrastructure Hamas built up over the years is immense– . . . tunnels, extended bunkers, weapons storage facilities, even within urban areas.”

The massive underground tunnel network–here shown only by those halls that wer mapped by the Israeli Defense Forces–was used as sit a network of tunnels of resistance as the dream of connecting Palestinian enclaves has receded with time as were first proposed to manage the possibility of removed self-governance that Israel could “live with”–including access to two ports–

The Gaza-West Bank Tunnel in the Trump “Plan, “Future State of Palestine” (January, 2020)

–the idea of a “tunnel” not under Gaza, ut linking Gaza to the West Bank, was on the table as a proposal for the “future state of Palestine” even if this waggishly accused as being a “hollow state.”

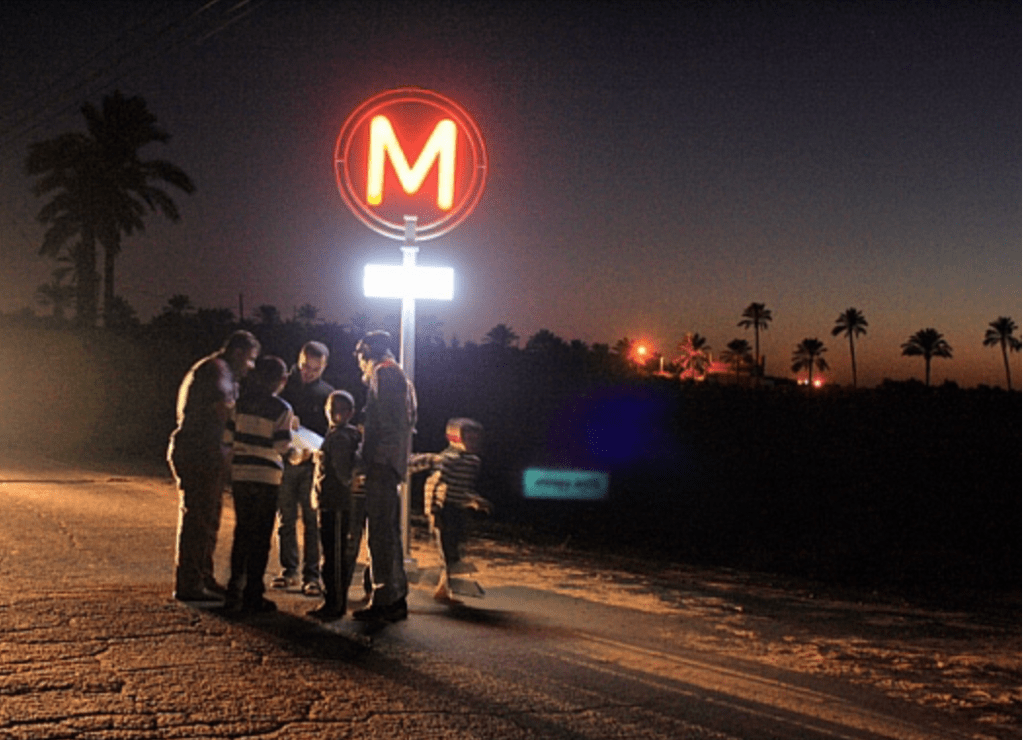

The network of tunnels had been the staging area for attacks on border cities in the past, including Kerem Shalom, the border crossing where Palestinian militants attacked, in the course of the raid seizing soldier Shalit a hostage to abduct to the underground labyrinth in the Gaza Strip. The warren is known as the “Metro” in acknowledgement of the underdeveloped and unmodernized state of Gaza –Shalit was held for four years, to the surprise of Israelis if never of his own family. This is the underground network where the current hostages are probably been secured, and has become a showpiece of engineering and a feat of resistance in itself, extending despite the built boundaries in cleared boded lines that promised an infrastructure for future cross-border attacks.

The Metro became a showpiece, but a site for staging nationalism in summer camps, in the poor state of the Gaza Strip, promoting her heroic ideals of Hamas militants for independence, and fostering the dreams of tranport beyond bored walls of an ever-expanding underground network.

Denoting the narrow underground tunnels as a ‘Metro’ is not only in jest: a decade ago, the artist Muhammad Abu Sal, then 35, decided that the tunnel network demanded to be highlighted as an economic infrastructure of its own for smuggling weapons, goods, and people; as an underground critical part of its economy, he promoted network not as a secret warren but an form of modernity that might in the future provide a network connected Gaza to the West Bank by analogy to Paris! (The ferrying of kalashnikovs were not the original intent of tunnels that linked the Strip to Egypt, border, began as a way to import a variety of necessities that were absent from stores in Gaza’s after the imposition of a 2007 blockade on the enclave, from food to cars to even petroleum fuels.)

The bright and bouncy iconographic modernity of a subway modeled after that in Abu Dhabi, Paris, London, or New York that was staged as a theater piece for the Festival of Cultural Resistance three years ago in 2020 painted in bright bubble-gum colors (If Abu Sal was promoted as a “penetrating artist,” by The Freedom Theater, the network that is now getting newsplay as a net of resistance was an economic necessity, but that were mapped a decade ago as a hidden “world of weapons tunnels penetrating into Israel, creating the possibility of a mega-attack” that demanded to be destroyed for the safety of the Israeli state.

This was by no means created as a network for military use alone, but of survival: many worked in the tunnel, hauling goods to the residents of the enclave who suffered from the blockade Israel had imposed from 2007, hauling goods from Egypt in its confines, pausing only occasionally for a cigarette break deep underground.

Paolo Pellerin (2011)

The network of tunnels is but a part of the cross-border movement that has transformed the Gaza Strip from a border zone to a network that stretches underground. Even as Gaza is cordoned off from the internet, is tied to a larger world by nations who have offered new tools of cross-border violence. The effectiveness of the tools by which the October 7, 2023 invasion is proof of technologies to break border defenses, in a variety of emergent tools of cross-border warfare of which we would be better to take note.

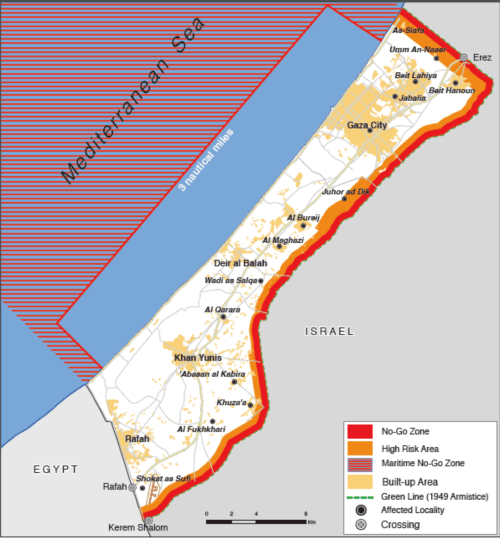

Such new strategic technologies were not only tactical. They ensured the parallel world of the prosperity beyond the border wall, in the land of their occupiers, suddenly was able to access by dismantling the very surveillance apparatus of the border Israel’s government had so confidently invested, secure in the conviction it would not eve have to negotiate with Palestinians,–just confine them by an ever more clever security wall. Massive state investment in technologies of confinement have been felt by residents, as they have cut into farm lands of Gaza’s residents by the expansion of a “No-Go Zone” around its perimeter, to contain risk,–

–pierced as “kamikaze” aerial drone warfare offered a low-cost technology to pierce its confines piercing the border at multiple sites simultaneously on October 7 at daybreak.

Google Earth

The border technologies of risk-management had nourished a false sense of security. But investing in outdated tools of securitization may have led to a nightmarish return of violence in the single greatest day of Israelis killed, despite all that investment in the secure tools of guarding the Gaza boundary. The invasion of those paragliders landing in kibbutzim after they flew across the border suggested the ease of transit once the observation posts were removed, and border surveillance lifted. It reflected as if in a rear view mirror the incursions of 1956 on refugee camps in Gaza, where Israeli troops led by Ariel Sharon, later commander of the Southern Forces, as commander of a paratroopers’ brigade, staged revenge attacks refugee camps–

–an area whose settlement Sharon encouraged, before unilaterally withdrawing troops in 2005 to comply nominally with a “Road Map for Peace”–without relaxing vigilant naval control of ports or of its airspace. The vision of Gaza as a border state, and a frontier, close to the heart of a previous geography of the Middle East from far earlier Arab-Israeli wars, was encouraged by Prime Minister Netanyahu, and have haunted the sense of Gaza as a frontier on which to focus public attention, as a region over which Israel has critical natural self-interest and a right to protect itself. The “Gaza envelope” was however liberalized as regularly spaced observation towers along the border created a monitored boundary, and which Palestinian observation posts monitored by Hamas took note of all movements of the Israeli Defense Forces by land, air and sea, offering a ground surveillance that the October 7 invasion clearly took advantage of. Palestinian military experts argued that such field posts “may be considered defensive and not offensive since . . . Hamas cannot cover the entire border,” leading Israeli forces to target observation stations along the north-south border, the questions of gaps of surveillance on the border either from the sandy hills of Hamas observation posts or observation towers provided a tactical basis for military confrontation.

So much was confirmed by the cross-border attacks of October 7 in more gruesome detail than could ever be imagined, even by the most hard-line defense spokespeople. While many maps registered the shocking incursion of terrorists–communicating the violence of the even that left 1,200 dead–both soldiers and residents of the new frontier of kibbutzim, clustered around Gaza’s border barrier, we may forget how these pioneers who are also acting as colonial farmers in a more explicit policy of taking back the land up to the wall of the Gaza Strip. If hostages were vulnerable children, concert-goers, and elderly who happened to be in the kibbutzim, these outposts are not friendly neighbors to Gaza. These are victims whose names are recited, and rightly added to the prayers, but were spread about Gaza’s barrier, where they seemed most safe. The attacks that were staged in the invasion followed maps to the settlements–

CBSTV

–the incursion of the barrier and breaching of the barrier wall played on American television news, perhaps, in an echo of the movement across other walls–but cannot be mapped disinterestedly, or at a remove from the transnational ties that have redefined the geopolitical plate-tectonics of the region.

Weren’t the settlers who were encouraged to settle just beyond the boundary perimeter, as part of a new “frontier state” of Israel, promised a false sense of security by the securitized barrier wall? We may do well to focus our attention on the experience of those 18,000 Gaza residents who work in Israel, or possess work permits–many now trying in vain to contact their families within the region–and the experience of Gaza’s residents as they were on the border, facing the opportunity to travel to work. And to consider their travel past these villages, that were mapped as targets by the invaders who arrived in paraglider or motorcycles at their destinations, believing that they were achieving a remapping of the Middle East long mapped to their disadvantage.

If all crises are overshadowed by the climate crisis today, the top driver of human suffering, the absence of water in Gaza, were some 97% of water is not drinkable, given a highly contaminated Coastal Aquifer so combined with salt and untreated sewage to be unfit for human consumption, even before the bombing destroyed much of the plumbing infrastructure in urban areas that have provided the main conduits for drinking water to arrive in the enclave that lacks a water grid, the closing of electricity to the region has shuttered desalination plants and local wells. The water available to the residents of these nearby kibbutz, where the farming of the dry desert soils offered a basis for viable agriculture, were a stark contrast of inhumanity, making no geographic or environmental sense, as the engineering of desert farming by tools of drip irrigation–pioneered in the southern Negev, now using recycled wastewater from Tel Aviv!–as well as permaculture, in organic farms removed from the local water table. The isolation of Gaza from drinking water or functional farms has created a water crisis with deep health risk.

The borderline war between Israel and “Gaza” was fought less on borders than hinges on exactly these forms of trans-nationality. The haunting nature of the border as a divide assumed disproportionate presence for Palestinians that cannot be reduced to metaphorical terms, but were able to frame a new world view. The trans-nationality extends to migrant workers who found a new life to work beyond the border walls as service workers in Israel, and glimpsed a sense of another life,–or heard it recounted on iPhone or mobiles from household members who did. Trans-border movement in a global labor market found something of an echo in the tunnels of the underground “metro”–a hidden map, as it were, removed from surveillance and Israeli observers–that connected the terrorists of Gaza to a market for international arms, ferried, one suspects, from North Korea, whose arms were used in Syria and Lebanon, as well as Tunisia, Iran, and Egypt.

These were the arms that overwhelmed the barriers. Though we consider unprepared IDF forces, distracted, perhaps, by the micro-conflicts of West Bank settlers, and maybe some of low morale, but who were looking at the screens that they were provided in boundary monitors,–not at other military intelligence. For the disabling by sniper fire and explosive drones that arrived at the boundary barrier at the early hour of 6:30 am in the morning were an early alarm. IDF guarding the barrier were disoriented by the surprise attack, as gunmen quickly took out observation posts and cameras on the boundary itself and leaving security forces disoriented and disheartened at a systems failure or failure of military intelligence. While the shock of the attack reverberated globally, the unmanned aerial attacks belonged to a new range of arms increasingly stockpiled across the Middle East beneath Gaza City and in the tunnels that constitute the “metro” not only among its military groups, but to the wider arms trade, and the suppliers of new tools of cross-border warfare.

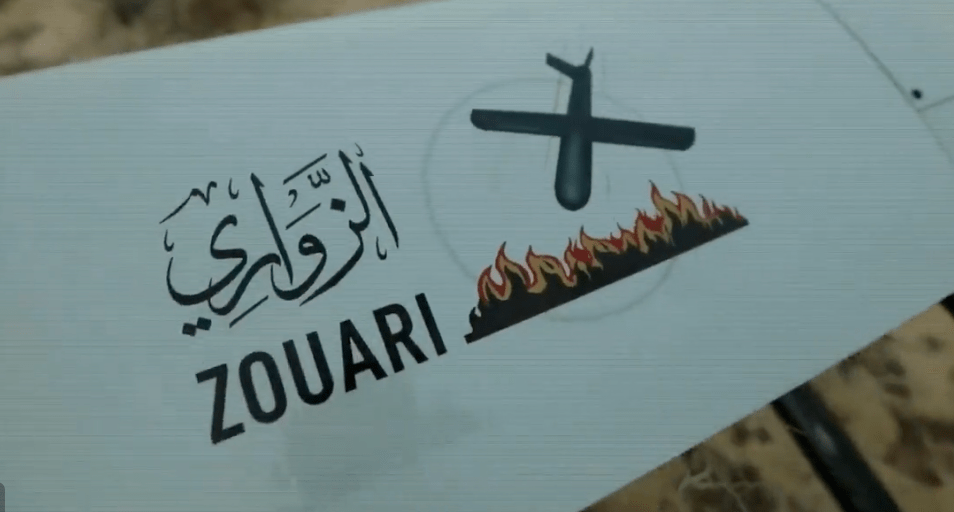

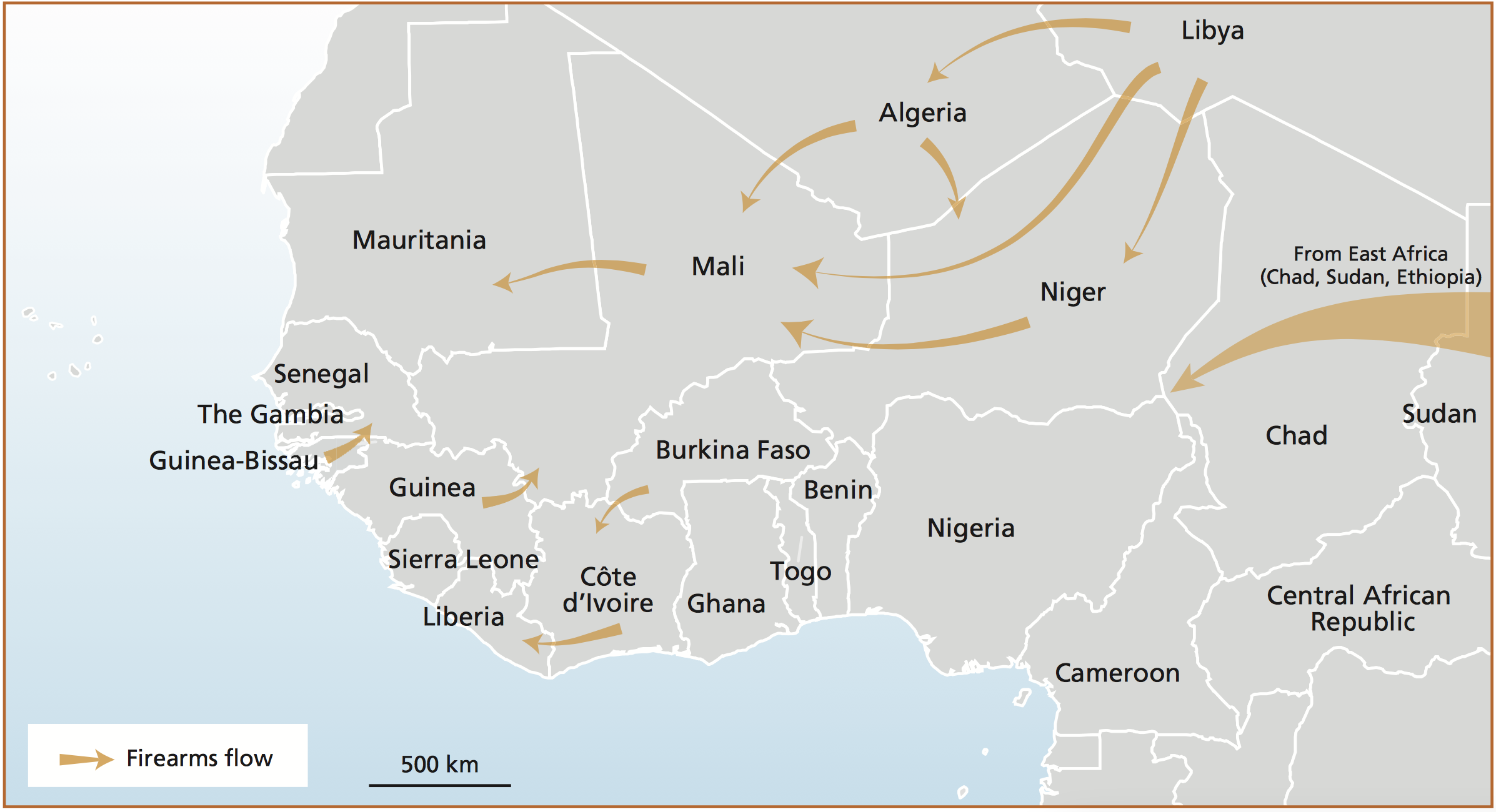

The tunnels passing underneath the very barrier that Israeli contractors built around Gaza after withdrawing troops may have brought a new variety of weapons to the Israel-Gaza frontier, against which the current system of security had no guide. The underground tunnel network that was crudely extended from Gaza’s friable soil far into Israeli territory–or from the occupied territory into the national territory-. The walls became grounds for investing in the critical year 2016 in a border fence, a perimeter state-of-the-art and “smart”–equipped with security cameras, CCTV, and monitors. Yet the persistent trans-nationality of the region was not mapped, as new network of tunnels linked Hamas to arms ferried from Iran, North Korea, and Egypt– conduits of the very border-bursting shoulder-fired F-7 rocket-propelled grenades that are used against armored vehicles, or the thirty-five “al-Zawari” kamikaze drones–named after the Tunisian engineer Mohammad Zouari, killed by Mossad agents in 2021 for designing UAVs–took out many observation towers. The arms that flowed into Libya, as much as from Egypt or Tunisia, may include shipments of Turkish weapons that have flooded Qatar, Tunisia, and Ukraine since 2020.

The cross-border technologies that developed in the very years we assumed the world gone silent before COVID-19, and Turkish Bayraktar drones flooded the Middle East to further Turkish interests, a shuteye also flooded the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and helped Azerbaijan’s battlefield success, even in the face of a large army of Armenian tanks. And the drones designed by the Tunisian engineer who had learned techniques of drone-making in Iraq suggest a new level of combat, and “borderless war,” once tied to the counter-terrorism techniques of targeted killings, that were–perhaps terrifyingly–critical to the cross-border attack on the border barrier.

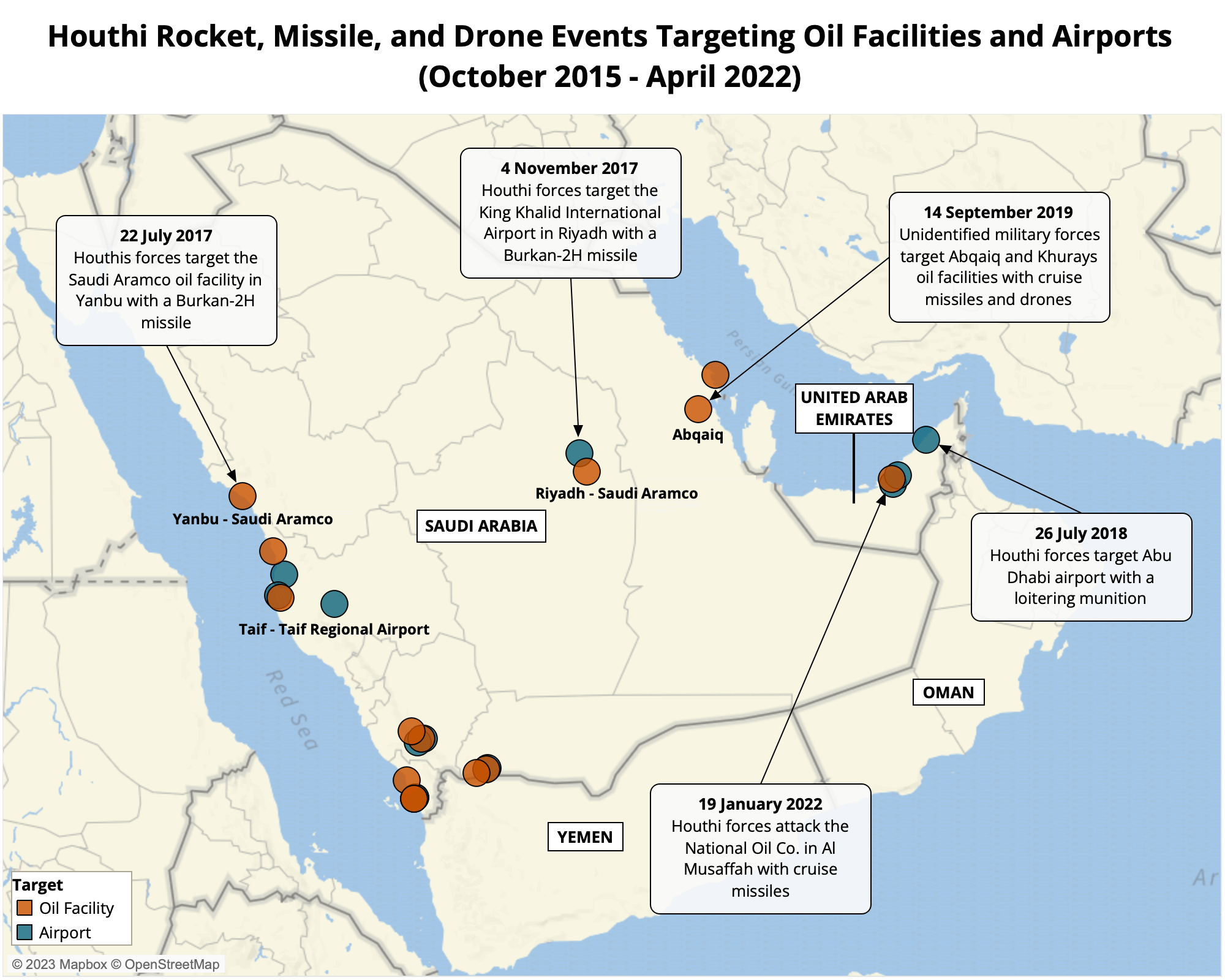

These cross-border weapons allowed military stability to be destabilized with disorienting rapidity, upsetting the balance of guarded frontiers, creating gaping holes of security in American-made defenses, or developing extended-range missiles able to target energy infrastructure and oil refineries in an aerial war. In an eery echo of the barrage of V1 and V2 rockets the Nazi air force fired on gyroscopic guidance systems to target populated areas of England in World War II, the GPS-equipped drones may have helped to hatch a project of targeting the observation towers that were the teeth of Gaza’s boundary barrier. The very sort of explosive “kamikaze” Shahed-136 drones of Iranian make whose small fuel pods, as the V2 rockets, directed their explosive warheads at targets in Kiev to swarm defenses with efficacy in 2022 seem, indeed, to have been tested out in an earlier border war. And if the Iranian drones whose 80 lb warheads exploded on contact were described as the “poor man’s cruise missile” by their manufacturers had been used in attacks on American forces in Iraq and Syria, as well as the UAE; swarms of drones fired up by the fifty horsepower engines of the Iranian drones are increasingly been used to eliminate expensive surveillance and anti-aircraft systems, puncturing border surveillance, as it were, opening borders that were heavily fortified. (A recent drone attack on American forces stationed in the Ain al Assad base in Iraq were hit by a suicide drone in the midst of the bombardment of Gaza, claimed fired by the Islamic Resistance in Iraq, and five separate attacks on American bases in northern Iraq were reported, as fears of the war spilling over borders grew.). The use of “loitering munitions” and drones by Houthi fighting in Saudi Arabia have absorbed the large supply of rockets inherited from a Yemeni stockpile of unmanned aerial vehicles, perhaps tied to Iranian weapons technologies.

The result is already shifting the front of war to prolonged missile, drone, and rocket attacks. Technological developments in aerial warfare date from around 2018, often to win withdrawal from occupied or disputed territories in the Middle East, as in Yemen, if they have never been launched against so securitized a border as in October 7 shock attack of the IDF’s observation towers. From 2019 the use of high-precision aerial drones developed new fronts of Houthi cross-border aerial warfare as tools of direct military engagement of expanded military targets, readily including civilian targets that were off the military map, including the targeting of oil facilities, airports, increasingly targeted since 2018, and ending only as a UN truce was brokered in April 2022. Yet Houthis and Salih helped open a new frontier in aerial cross-border warfare, which the shock invasion of Israel’s highly regarded border frontier must be contextualized in–and perhaps also seen as a new proof of concept in cross-border warfare, making a truce all the more important.

This suggests that the Gaza War is the latest front in an expanse of unmanned aerial vehicles–a new era of remotely operated drones programmed in “autonomous mode” that require little human control. The use of swarms of drones have been used extensively in conflicts in the Middle East, including the wars in Yemen and Syria, before they swarmed the surveillance stations of the Gaza boundary wall. The regional spread of such drones is less openly mapped,

But the centrality of such unmanned drones able to focus and take out border surveillance stations may have been neglected in most news reports. The focus on the violation of Gaza’s borders and the overwhelming of the billion-dollar barrier war cannot reveal the danger that the firing of such a swarm of robot drones poses to Israeli sovereignty outside an international arms traffic. The rockets that began the raid that the Hamas al-Qassam Brigades began started not with the DIY “Qassam” rocket of nitrogen-rich fertilizer and sugar,–if the image was worthy of scrappy resistance against an occupier–

–but the use of drones did show scorn for the proud surveillance towers, disabled by the density consisting of 5,000 unmanned rockets that arrived in an interval of twenty minutes. Their spatial distribution overwhelmed the technical tracking abilities of the Iron Dome, confusing the smart wall that would supposedly withstand any advance. If Samson in Gaza seemed to no longer be the legendary warrior who “ran on embattled armies clad in Iron,/and weaponless himself,/Made arms ridiculous” as he scorned “proud arms and warlike tools,” the army of aerial drones that initiated the unexpected cross-border attack overwhelmed the geospatial intelligence and sensors with which the border barrier was equipped, allowing the advance of men who were armed to the teeth.

In the biblical story of Judges, the rage of a blinded Samson, reduced of his powers of martial strength, is seen as “in slavish habit, ill-fitted weeds/o’re worn and soil’d,” seemed far from that image of the Samson who “weaponless himself,/Made Arms ridiculous” before he, in his rage, lifted the doors of Gaza, carried away the gates of the city, “unarm’d” but summoning his strength as his hair grew that again after he lay in reflection in prison, blinded and distraught as he reflected gloomily on his fate, is remembered as lifting the city gates of Gaza in his rage, bars an all.

Samson carrieth away the Gates of the City, designed by Francois Verdier (1698)

Eyeless Samson is remembered as un superhuman rage, lifting the doors of Gaza by his hands alone, before he carried them off in the dead of night by bare hands to Hebron by superhuman strength.

But this is not a biblical story, even if it happened in a place of the same name. The firing of an army of aerial drones seems to emulate a home-made “shock and awe” that Hamas was sold as a working plan became a proof of concept that impressed the world. The critical use of kamikaze drones to disable the security towers, communication relays, and border surveillance system before the ground assault incapacitatingly “blinded” Israel to the attack, enabling the brutal strike on kibbutzim by a functional mapping of surveillance tools, as much as of the territory that was attacked: the territory existed as a surveillance apparatus, in other words, as a territory, but left the territory vulnerable. The barrage of weapons used did not rely, as in previous years, on the unguided Chinese-designed, Syrian- made rocket, a major element of the Palestinian rocket arsenal that Fatah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad have often used in attacks on cities near Jerusalem and Haifa–and are commemorated on this mural in Gaza, before which schoolchildren are shown passing–

Children Passing Mural Celebrating Capture of Israeli Soldier Galid Shalit/December 11, 2021/Said Khatib/AFP

–or that Hamas has even invited kids to take selfies before a public display of the missiles themselves in the aftermath of increased Israeli-Palestinian violence in July, 2023.

Mahmoud Issa/SOPA Images

Much attention has been devoted, and alarms raised, about the cross-border and transnational ties of Hamas to military intelligence services of Hezbollah in Lebanon, long before the rise of cross-border skirmishes on the Lebanon border began during the Gaza War.

Yet the routes of intelligence and the uses of older missiles were less central to this conflict. And this time, in other words, we were all reminded the territory was shown to be only a map–increasingly rendered vulnerable as its surveillance structures were disabled by explosive drones.

The place of Gaza on the map is critical, but we need more than arrows to define its space, and to use weapons to erase the boundary barriers that were built by Israel to contain its presence on the map. For the strip has existed in reflection of the guarding of its borders, and the “metro” of tunnels that have let it be linked to the west have become turbo-charged, of course, from the barrage of rockets to the troops who followed, ignited by the giddy vertigo of crossing the border fence that may be missing form our maps as we map the conflict.

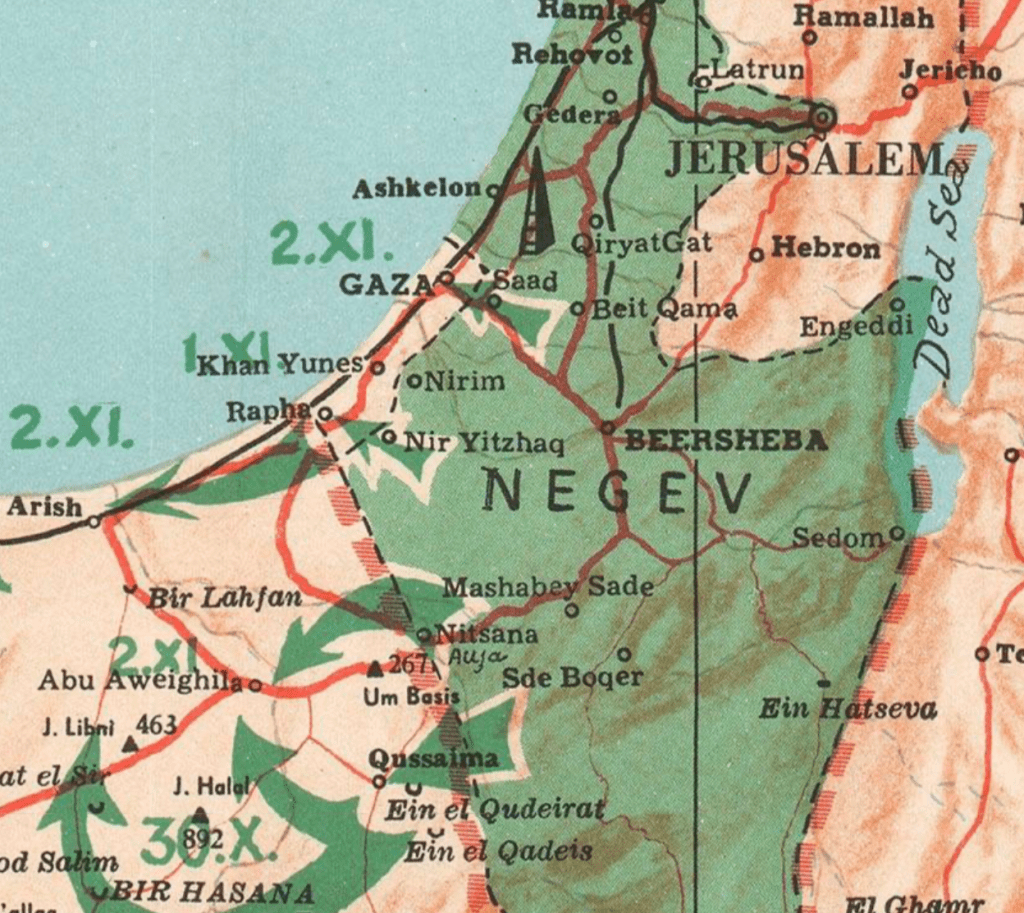

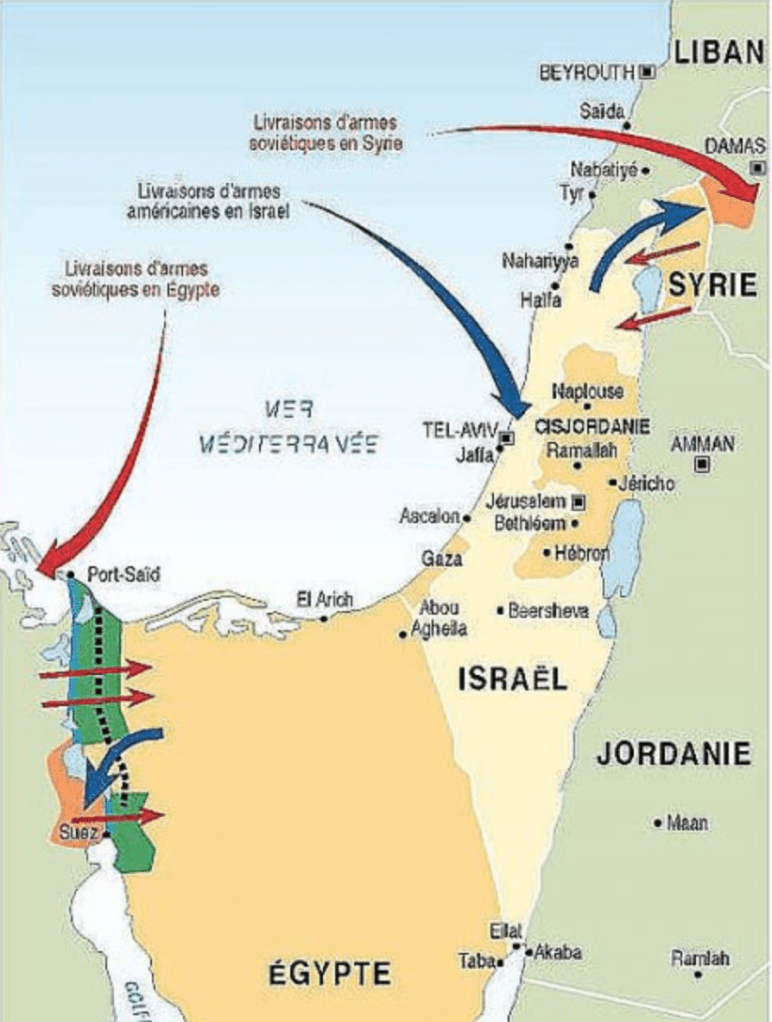

We might best consider the trans nationality of Gaza as a reprisal of the border strikes that were enabled by the funneling of arms int eh Cold War from the former USSR to Syria and Egypt in order to restrain the ambitions of Israel that American arms bolstered, although the size, apparatus, and techniques of armaments have existed–and the mapping tools that are now part of the arms.

Philippe Rekacewicz, The October War [Yom Kippur War) (1973), Monde Diplomatique, April 1998

The war on two fronts was, as it occurred, a war for Israel’s existence. But as the above visualization nicely reminds us, the strategic alignment of troops in the Yom Kippur war are best mapped not only by military advances, but against the backdrop of importing weapons that fomented the war that felt inevitable. This time, the borders and divides are more defined, and the flows of weapons demand to be mapped. But the combination of the eery flow of Gaza workers into Israel, and the possibility of a flow of cross-border weapons that arrived into Gaza, even as Israel tightened its noose, have inspired a violence that leaves many hoping that the other is wiped off the face of the map. But whatever the map we chose to study, we may misunderstand the locked-in nature of the current war as local, or rooted only in local history: if it is rooted in an occupation, it is also a new stage of the diffusion of swarms of remotely guided missiles, produced on the cheap and not dependent on arms providers in removed areas, as the United States and Russia, but able to be produced in mass quantities on the cheap to reveal vulnerabilities all countries may soon feel.

Bill Pugliano–Getty Images

Bill Pugliano–Getty Images

Google

Google  Google

Google  Google

Google  Google

Google  Google

Google

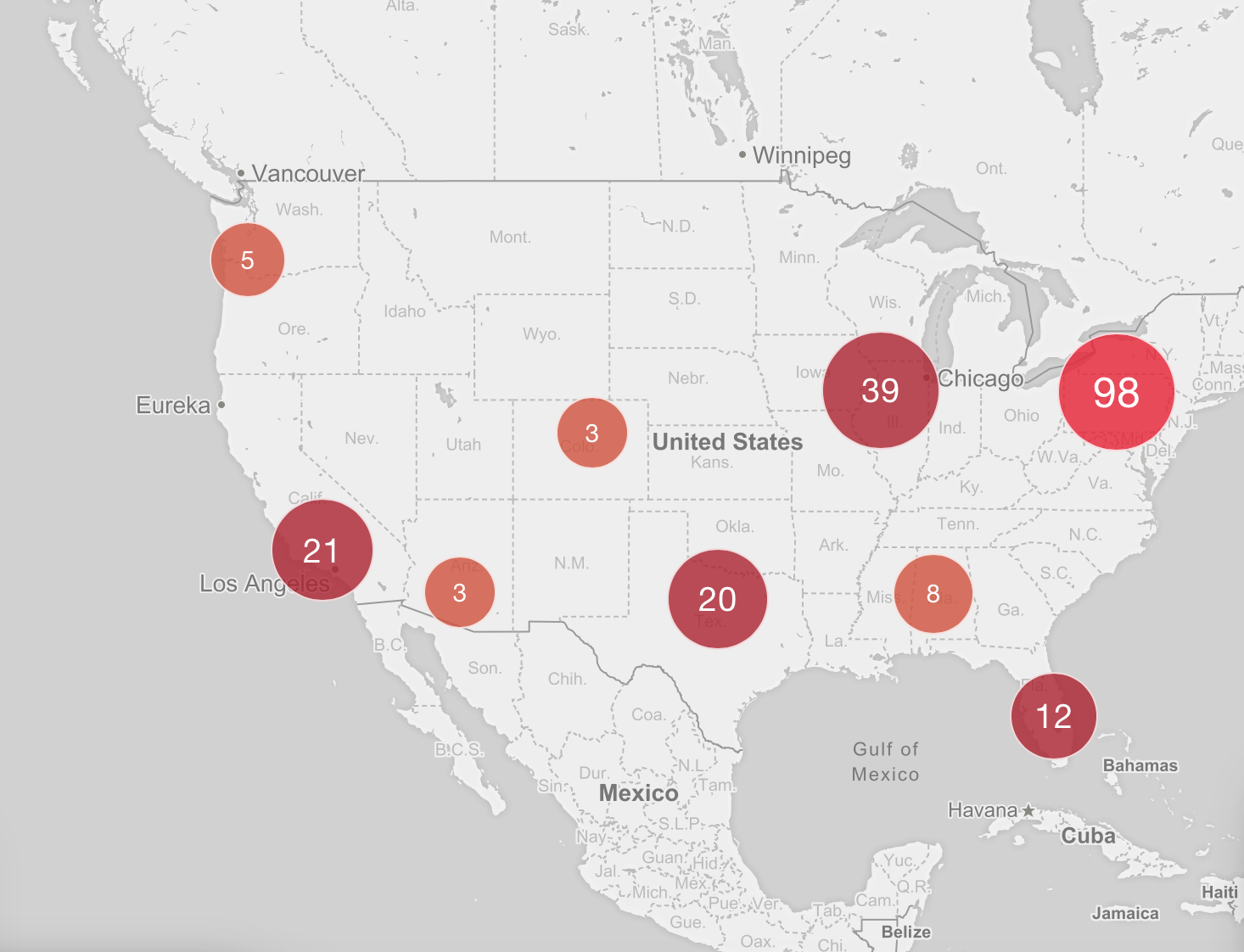

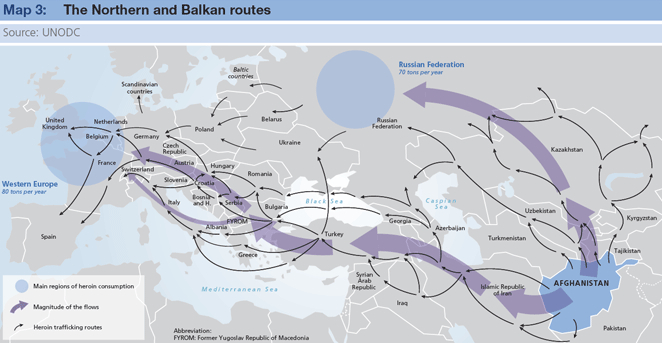

UNODC

UNODC UNODC

UNODC

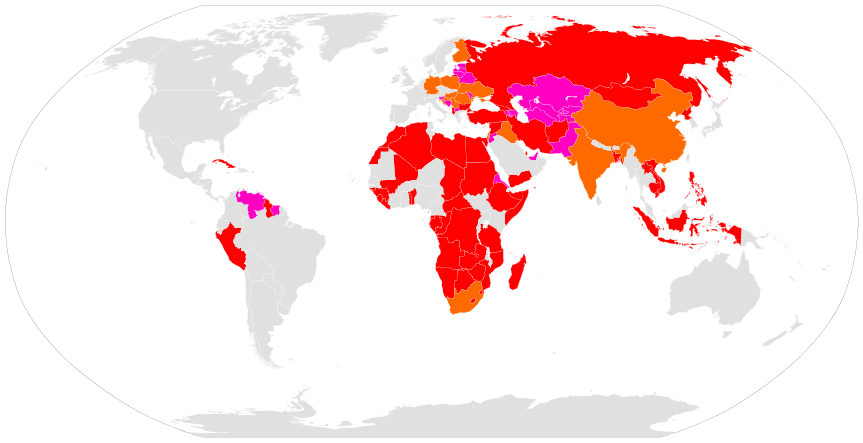

Михаи́л Тимофе́евич

Михаи́л Тимофе́евич

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,