The Google Doodle reminds us that the Pizza Margherita of cheese, tomatoes, and basil remains the If the “most popular topping variation” in Neapolitan style pizza, and indeed tat the universally accessible status of the pizza in fact had a local origin. If the slice–that ubiquitous urban signage announcing the possibility of a mouth-watering delight–led itself to multiple neon variations and a familiarity with food-on-the-go, the increasing slipperiness of the smooth surfaces of a globalized world find an increasing instability and currency of pizza that has created new categories of eating, consumption, and indeed baking as this most quotidian of foods deriving from the sea-port of Naples has gained a currency far from its earliest ovens, and become a token and vehicle–if not a magic carpet–of migration itself, as much as an immigrant food.

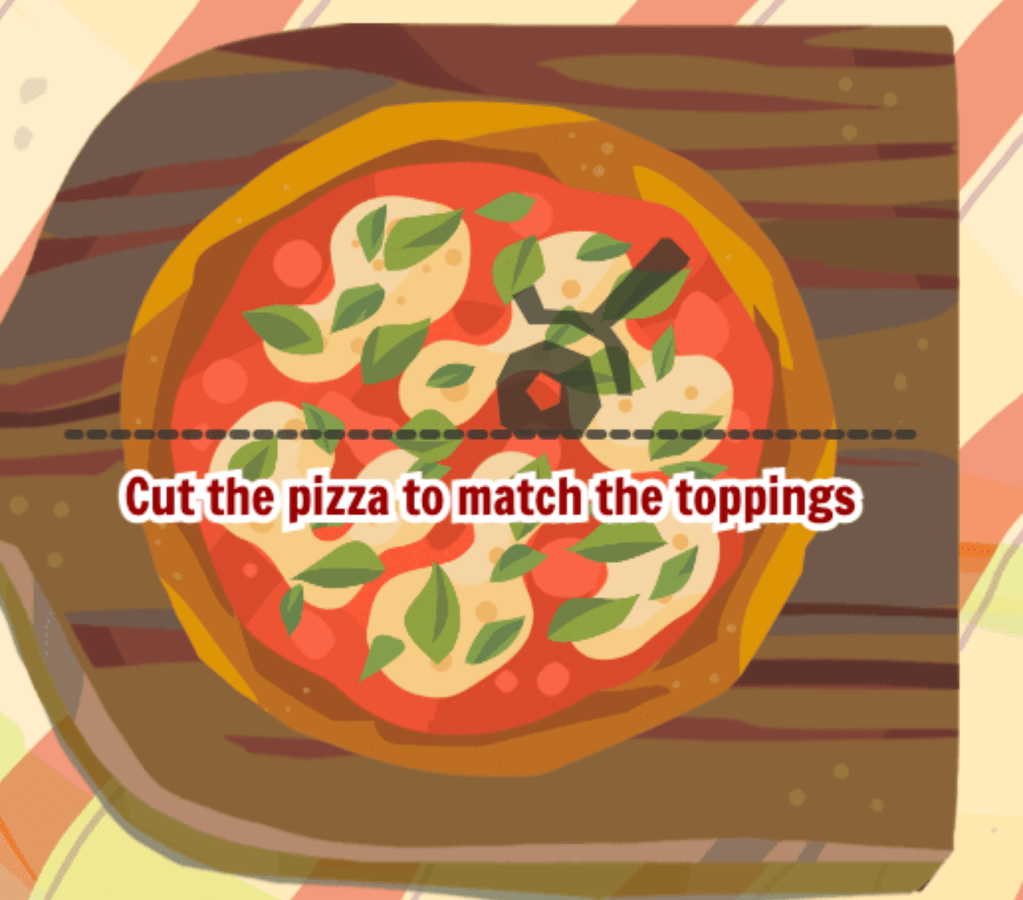

The balance between the global significance that pizza has gained as a sign of satisfaction confirmed by how a Google Doodle of a circular pizza was divided by a pizza wheel, its slices grabbed as soon as they were cut from a basil-laden pie of melted mozzarella cheese. The doodle, as if product tested by Google, was both local but global, a recognizable sight and site of comfort that as clickbait triggered Pavlovian associations in one’s mouth, even as cut slices vanished off the screen, the taste of a tangy warm pizza sauce eerily triggering sense-baed responses even if no melted cheese was in one’s mouth. This existential irresistibility of the taste of pizza–even cold! “Cold pizza, can’t beat it/Yeah, I know it’s not strictly vegan,/ . . . just eat it!” croons American singing legend Jonathan Richman–may be made of flour for the most part in weight, but has a flavor we anticipate. As the editions to pizza, from hot pepperoni and golden honey to pineapple and processed meats, have grown, in ways that have changed the surface of the slice, the mapping of its preparation–and its national identity–demand mapping.

As much as a destination of the city nomad, eager to grab food when pressed for time or between meals, the neon-lit pizzerie of New York and other cities now dot a landscape that once proclaimed the cultural arrival of status for a new group of immigrants, even in streets dominated by smoke shops and dispensaries, still suggest an echo of the early immigrant patterns that defined the city as a unique site for ethnic cuisine. Long transcending the simple advertisement or calling card but offering a promise of mouth-watering and heart-warming warmth as a destination, the personal familiarity of the beacon of the warm pizza shop was, in a sense, an alternative home, a domestic space of recognizable tastes–now called ‘authentic’ and ‘authentically New York Style”–as if they are custodians of a cultural memory, beyond a recipe. While the immigration cauldron may have made the slice an invented tradition, the culinary currency of the modern metropolis made the pizza sign not only a sign of the cultural hybridity of the city, but the wealth it had on offer, long before the frozen pie was imagined. The shock that th e’slice’ is an immigrant invention in America, a new apple pie, aside, the tussle over ownership and property of the pizza is a conundrum given that its common denominator is a caloric pleasure of settling one’s appetite, more than settling a New World. The pizza slice once clearly part of the urban landscape has gained a currency that makes it hard to root in place and space and challenges the stability of place in a fully globalized marketplace.

But even before the victory of the emoji, the neon sign was a hallmark of fulfilling appetites, indeed triggering hunger, and promising a satisfaction few foods seemed able to equal or provide–before they became vector files or objects of home decoration.

Even in our world of smooth borders and opening frontiers, the pizza has gained global currency as a comfort food. For pizza has developed such a physical if not neuroloic Pavlovian tie to our sense of taste, curried in new ways as marketers of pizza champion hot honey as the “best thing to happen to pizza since pepperoni”–most likely added as a topping from stores of German migrants in lower Manhattan–the history and quality of pizza as a calorically rich tongue pleaser demands to be traced and the glutinous layers of the shiny surface of the gleaming slice of pizza tried to untangled. in space–and how much the melted surface of the modern slice immigrated to America, via the melting pot, or the roots of authenticity from which this increasingly globalized concoction sprung.

And so it was the only response to the global reach of Google, and something of an inevitable sign of pizza’s new global reach as food of specific provenance, that the margherita pie became, in the midst of its growing consumption of take out in the pandemic, a pleasant graphic interface that attracted heightened attention if not some joy. In an era of sheltering in place, the social and most demotic of street foods was presented on our screens as a hope of good cheer, if not pizza and beer.

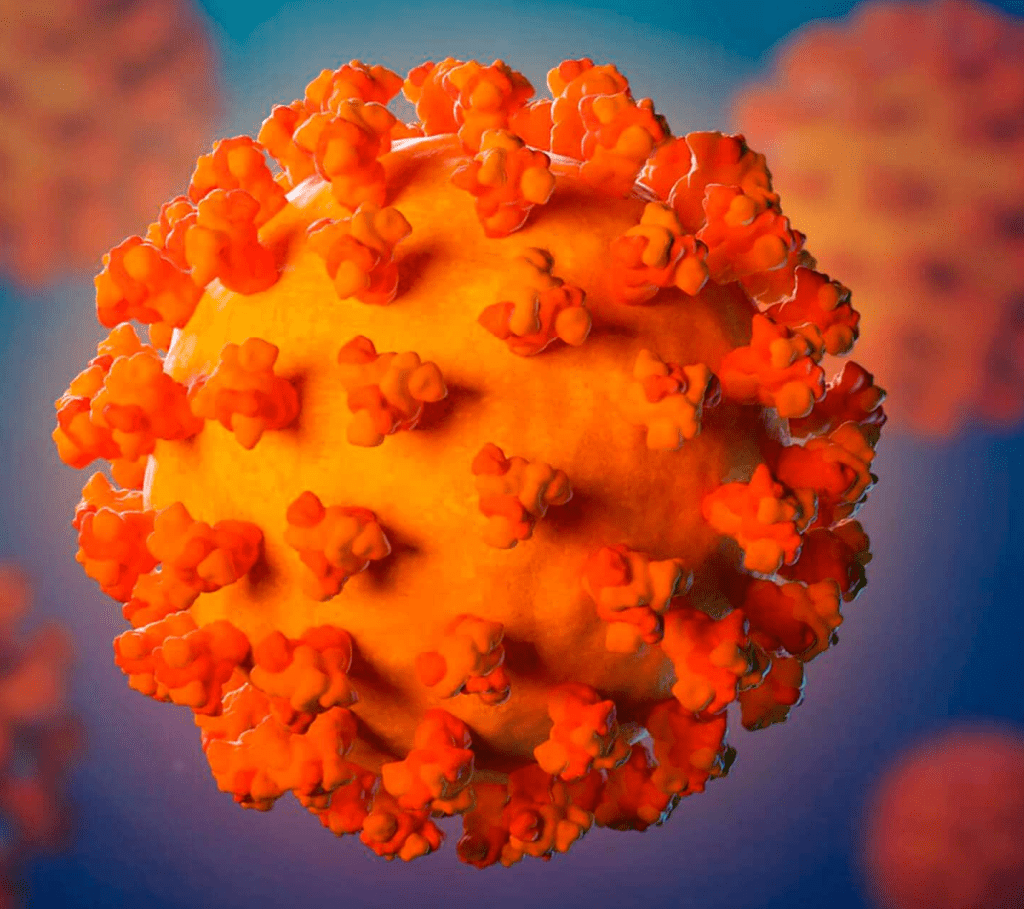

The Google GIF was a gift at the close of a particularly tiring if not emotionally exhausting year, a form of nourishment we feared we wouldn’t have, we hoped, to repeat, but also feared we well might. Even if we hoped that with the first Pfitzer COVID vaccine approved by moths previous, we were emerging, we knew, if we suspected the virus would continued long after the arrival of bivalent boosters. Could the warm pizza emerging from the oven, or being sliced on our screens, offer needed meaning, in an age of Zoom, as if it might be a welcome surrogate for sociability, in lettering made of bubbling cheese set atop a rich tomato-based foundation?

Google Doodle GIF, December 6, 2021

But for many who lived behind screens, the arrival of pizza was a promised respite of comfort in the day. Long before the increased currency of pizza delivery in the current pandemic, pizza was the classic to-go food, born for the street: the global server reminded us that the comforts of the pizza has been recognized for its origins in Naples, home of the ancient and timeless festival of gluttonous festival of the Piedigrotta, whose ancient Roman fertility festival is preserved in the eating of roast meat, wine, and cheese–as well as pizza!

If “Piedigrotta” now lends its name not only to local festival but pizzerie across the peninsula, the Google Doodle invited us in the midst of winter to ponder the pizza’s unmistakable comfort, a comfort nourished over the pandemic that even in a cartoon rendering of the slices that disappear quickly as soon as they are virtually cut, or indeed before we “cut” the pie by a virtual wheel, placed in proximity to a brightly colored avatar to “celebrate pizza” on our screens, in an intimate act of feeding ourselves, cutting slices from a wooden sheet covered with tasty toppings.

Cutting into the pizza we could almost imagine as fresh from the oven, mozzarella melted, was almost sure to stimulate a Pavlovian reaction of salivation, as anticipation for the melted mozzarella dripped into umami seas of tomato paste. The undeniable umami of pizza is translated as comfort, instant gratification of melted cheese and tangy tomato sauce. As its status as a food of urban resistance and survival under duress has dulled, what was the cheap city snack, hardly a meal, became the food of choice for creating a sense of domestic contentment even as global insecurity and fear grows.

I saw the remaking of pizza, something now of a barometer of urban sociability and gemütlichkeit, has gained a mobility that seems, so long as on a paddle that resembles being fresh from the oven, the pleasure of being an edible mad lib of its own, infinitely personalized, and the lovely luxury of cheap eats. The availability of pizza even in the pandemic a way of finding some contentment in a comfort food, a respite from the visually eerily similar coronavirus that so dominated our minds, with spikes and not toppings, that it seemed to augr a new era or period of humanity, and had made us scour the internet for historical precedents. Was not the pizza also affording a tie to a material, comforting human past?

The diffusion of pizza in frozen form, ready delivery, and instant gratification even before the pandemic. The conferral of a status of intangibility as a global heritage–and a global heritage site in Naples, site where the Margherita is the preferred pizza, transformed this most material of food craft to local arts amidst a globalization of pizza so unprecedented to blur cultural boundaries and render the world’s surface as flat as a pizza pie, as pizza, once described as a food of sailors in the port of Naples who made pizza marinara the classic to-go food before disembarking on Mediterranean travels. Yet it was in the New World, in the immigrant communities in New York and Staten Island, and after the Great Depression, when many Italian-American family matriarchs regularly cut off part of the dough prepared for bread-making to provide the basis for pizzas, that pizza emerged. If with origins as a special family treat, garnished with leftover tomato sauce, the rise of economic immigrant prosperity introduced at the first parlors that life blood of culinary preparation, anchovies, pecorino romano, and sliced mozzarella, to meld in a pre-heated oven, a magical transformation of melted cheese unlike the magic filler of bread.

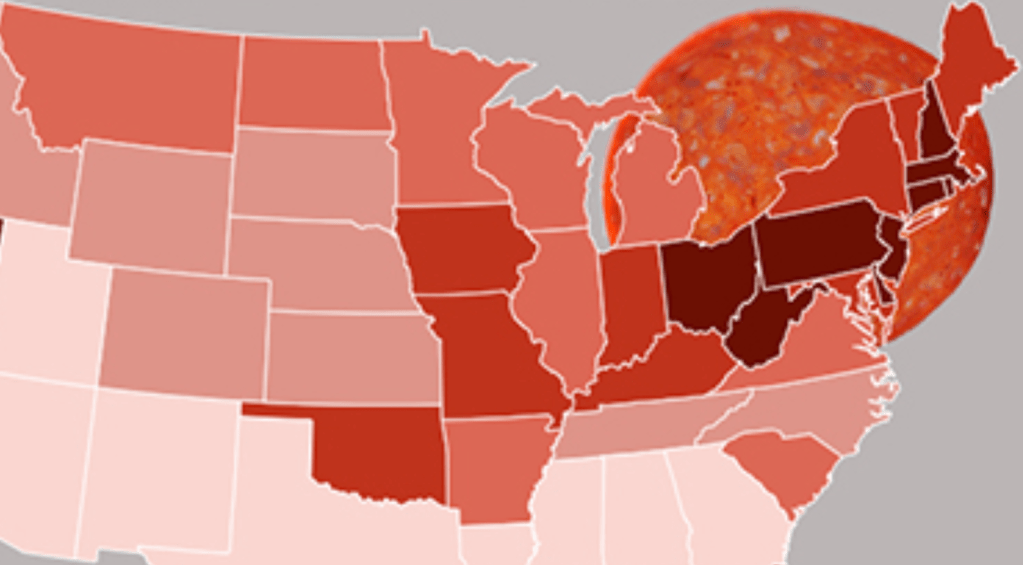

The expansion of chains of pizza parlors, pizza cutters, pizza toppings, and pizza sauce, grew on both coasts of America, first in prosperous immigrant centers, but soon in Depression era America. Even though current pizza shops per capita are greatest in northeastern states New Jersey, Delaware, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, parsing pizzerie per capita by state “density” somewhat misleadingly skews the spatial distribution from those dense urban hot-spots of pizza ovens like New York or Chicago–true hotspots, of course. Among the oldest pizzerie are found in New Jersey, dating back to 1912 and 1917, if the oldest shop still functioning resides in New York City; the expansion of the stores in economic downturn reflected the birth site of a transplanted food set to Americanize, with a pizzeria opening in San Francisco in 1935, as well as Boston, New Haven, and, outside New Jersey, that early site of Italian American immigrants’ upward mobility. (It may be New Jersey afforded beefsteak tomatoes perfect for saucing, an agrarian epicenter of prepared foods, intensified by the truckloads of fresh tomatoes that arrived at Campbell Soup’s Camden factory, that had a role–true story–in making Campbell’s Tomato Soup the favorite lunch of the young Andrew Warhola in Philadelphia, who by 1968 silk-screened the label of its can to make it a visual icon of twentieth-century American art.). But the emergence of “Pizza alla napolitana” in an American cookbook printed in Boston by 1936 cemented its place in the home-cooking repertoire, mandating hand-stretched dough, smoked mozzarella, and dried oregano, but advising readers they can skimp as dough “can be purchased in any Italian bake shop.”

Density per capita of Pizzerie in Northeastern United States/ Estately (2016)

This is perhaps to speak nothing of quality. The mobility of pizza seems to have everything to do with the license to eat, as much as its readiness of preparation. But perhaps because of the market driven expansion of pizza globally, the placement of pizza as a cultural artifact becomes problematic, if not entirely lost to memory, and removed from place. The pizza became a classic immigrant food in the United States and American cities from New York to other east coast metropoles, its warmness transforming the crowded tables or expanded family-style restaurants to an expansive immigrant sense of home, as the arrival of rotating wheels, akin to lazy Susans, those elegant dining trays dating from the eighteenth century in mahogany wood, were diffused in mass eating booths of the 1950s and 1960s, offered a model for the rotating ovens bearing the circular pizza by ball bearings able to withstand the 500°F heat needed to create the perfect setting for the pizza crust’s rise, and the transformation of the raw layers of a pizza to meld together in an umami taste. The melding of pizza seems to be able to be made wherever there is an oven–wherever one can impart a blast of needed heat for the alchemy of pizza dough that distinguished it from bread–that the place of pizza is difficult to establish, and the place of pizza in memory difficult to separate from an actual map.

The certification of the local roots of spinning and stretching was restored to Neapolitan pizzaiuoli in 2017–not five years ago–after being petitioned to throw its international weight behind the local certification of provenance. The attempt to push back on the globalization of what they insisted was not a national but a “native” food, demanding to be seen and recognized as born nowhere else but Naples, and from DOC ingredients often reserved for classy wines, suggested a desperate defense of the prestige of the local amidst an age of globalization, a defense that in the midst of a global pandemic only grew.

The announcement led to a collective skeptical raising of eyebrows worldwide. Despite the need to protect endangered cultural goods, might it be compromised to apply the modifier “intangible” to one of the most pedestrian of hand-held foods, the treasured urban delight of those opting out of multi-course meals, long conveyed in “to-go” in cardboard containers if not readily grasped in one hand for easy eating, as a folded slice for added convenience, newspaper-style? If globalization has produced an untold range of appropriations of “variations” of the pizza qua pie, the UNESCO certification seemed a reminder that allowed future variations to proliferation, but also to anchor the mobile food–famously mapped in proximities to subway stations in New York, as if to prove this was the basic food on the go–in a site of origin as a sit-down food. To be sure, the pizza was a bit of a celebration of the long-denigrated southern identity,

The sense of accessibility of pizza was altered as the combinatorial nature of the pie created a sense of plentitude from a shifting cast of characters of local resources and add ons. The simple combination of fresh tomatoes, fresh basil leaves, and tangy mozzarella cheese was reduced in the Doodle to a holy trinity–“cheese, tomatoes, basil”–and not the globally available substitutes or processed cheese long used in American pizza flourishing in the post-war period across the processed mozzarella-rich midwest.

Google Doodle GIF, Dec 6 2021

Rather, a rather recherché fresh basil, perhaps familiar in Silicon Valley, was but one of the many “topping variations” on hand. Promoting the ease of translation seemed one of the major tasks that Google–or Alphabet–made to its users, as if the letters might be as legible as in a bowl of minestrone, reconfigured to result in the same meaning in any tongue.

“Pizza” was a bit of a universal signifier, by the new millennium, universally recognizable from Holland to Brazil to Croatia to Russia, to Japan, Korea, to Turkish, to Vietnamese. Its global presence that didn’t demand translation, not even from Google Translate: but the local origin Google gave the ubiquitous “pizza” only confirmed the ease of drawing relations between any space on the globe in the age of globalization. The optional add-ons from pineapple to bacon to chicken pieces betrayed its global appeal, apart from slightly more particular local salumi or meatballs. The pie, seemingly created to promote gastro-intestinal challenges with quasi-operatic bravado, might be seen as corruptions or appropriations and claims of ownership, given the near-universality of pizza’s umami appeal, and the sprezzatura of the pizzaiolo able to fashion a pizza’s surface with a fistful of olives, mushrooms, or oregano, if not green onions, squid, baby clams, red peppers, garlic, even nettles or pine nuts.

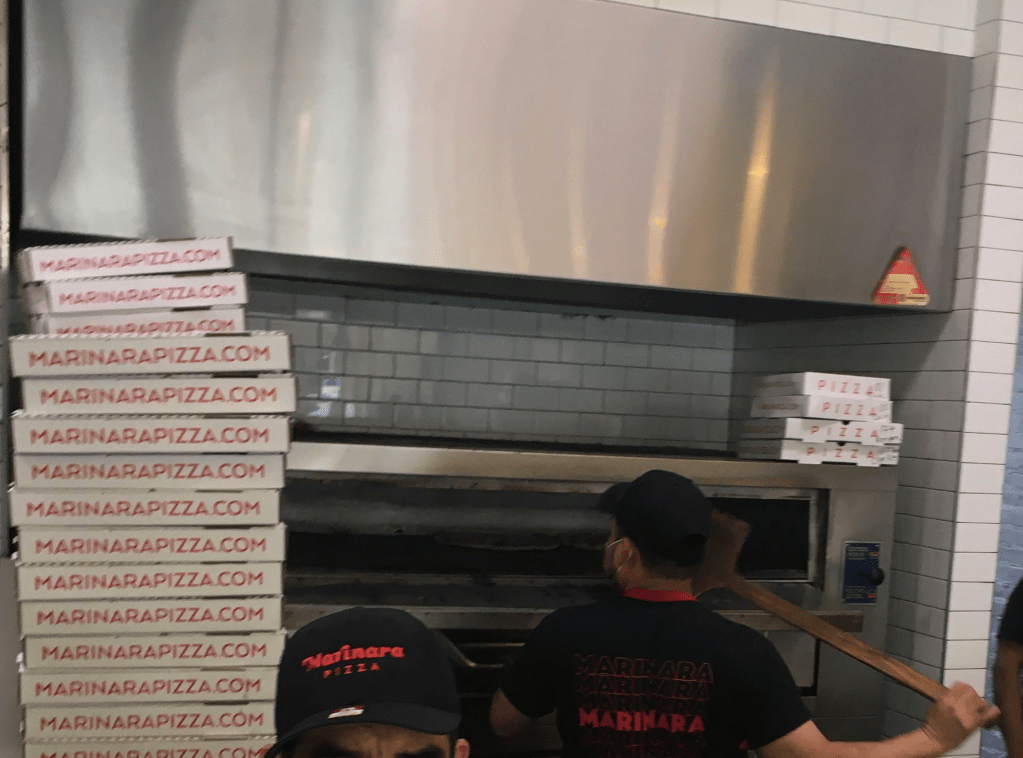

Before the pandemic, pizza’s diffusion was paralleled by the rise of the art of pizza-making as a visible sign if not tool of gentrification, and distinction, far from the Italian-American import of past or the frozen pizza that I was apprenticed to prepare with a thread of olive oil across its still-frozen surface to add elusive freshness. The recent rebirth of pizza as artisanal food that was prepared by a consummate chef–marketed to home cooks by Wolfgang Puck as an “Italian favorite” that in 1991 nailed the coffin on the “watershed decade” of 1974-1984 starting from Jeremiah Towers’ embrace of “gourmet pizza” of 1974 promised yeast-based crusts adorned with fresh toppings, reflected the return of wood-fired stone ovens. The recent hipster slice, evoking early gas ovens, recoups the pizza’s Italian-American origins to promise a nostalgic specificity, down to the glistening rings of pepperoni, as if to champion the pizza’s authenticity–even if this pizza was born in the era of mobile food consumption, whose promise of mobility indeed prepared for the food’s globalization. From the return. of pizza to artisanal roots as a home-made dish of something other than gas or electric ovens, the pizza as a rite of barbeque and a heat-blasted melding of cheese and tomatoes, the attraction to the dish became in demand to pin on a place, if only to distinguish it from its global appeal, and to create “pins” for, least the dish circulate as a disk on the frictionless world, situating it on a map with more precision than ancient mosaics of the brick oven.

But this pizza, one must remind readers, if one wants to find its “birth certificate” among Italian-American communities, was itself of course a hybrid breed apart, made not for an eat-in restaurant but for eat-out delivery in a restless world. The easy materialization of pizza from go-to ingredients led to the proliferation of “local” pizzas not only in Oakland, where I live–“Chicago” style; “Detroit” pizza, as if on an auto grill; Roman pizza; Neapolitan style; California pizza; slow food pizza, most very unlike the Margherita–each of which seemed variations on the umami of melted cheese and hearty tomato, with the addition, in the most American versions, of the rich and richly non-“Italian” pepperoni slices atop “New York” and “Detroit” slices, using beef pepperoni of midwestern German-American immigrants, to approximate the more finely sliced prosciutto of Italian forbears, profiting from the ready supply of cheap meat in ethnic neighborhoods, in a culinary improvisation of the New World. Personally, it was the addition of rings of pineapple in “Hawai’ian style” pizza, profiting from the rings that Dole Co. canned supplies at the ready, that suggested a globalization of what seemed local variaties.

New York Pizza Pie

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/__opt__aboutcom__coeus__resources__content_migration__serious_eats__seriouseats.com__2017__02__20170216-detroit-style-pizza-47-1500x1125-1-233d75e6021048b3bf3cf28bd59d310b.jpg)

Detroit-Style Pizza

–or the recent hybrids of bespoke slices with actual or faux artisanal–or retro–toppings, that increasingly seem to approximate “Italian” styles of pizza, inflected by global tourism. The days when I babysat for the grandchildren of a noted Italian historian, who ran a center of study from a villa outside Florence, might let me in on the secret that in Italy, pizza was “truly horrible” were long past. The high-style pizza of more fresh-tasting ingredients not only drew less from the canned tomatoes, but suggested a sense of a refreshening of American pizza tastes, recuperating a distinctly European feel that might be more easily paired with a rich or a crisp red wine.

Gourmet “New York” Style with Artisanal Blend

Pollara Pizzeria/Berkeley, CA

It was as if the pizza was a sign of globalization in that had spread from New York, in my imagination, but migrated globally in ways that any city could appropriate and imprint with its own stamp, to be exchanged in any site as a lingua franca of the street, perhaps furthered by the easy bake oven that once served as an incubator of english muffin pizzas in the not distant past that had already appropriated the pizza to a food easy to cook “under adult supervision” even for the eight-and-over crowd. Did the development of the oven lie at the heart, as it were, of the transformation of the pizza slice?

Unlike shops for single slices to national franchises, the audience for the ‘craft’ pizza in tonier urban areas, promising the restoration of an artisan like practice as pizza has joined the broad category of craft foods, nurtured in the capacious definition of “whenever a skilled person makes something using their hands, that’s craft.” Within this broad umbrella, one must place not only the rise of gentrified pizzeria and hand-thrown crusts, but the recent decision by UNESCO to affirm the dough thrown by Neapolitan pizzaiuoli as an intangible heritage of humanity, as Google reminds us, is in ways the final arbiter of the global: global recognition that the primary comfort food of globalization began from local roots, and from a glorious tricolore of simplicity–cheese, tomatoes, and basil–which is the hidden standard in the global currency of pizza-making, and, by coincidence, echoes the colors of the national flag it was long proclaimed in a rebus.

1. Situating or mapping the “art” of pizza-making obscured the ubiquity pizza had gained of providing a sense of plenty or satiety, at low overhead; the food industry had helped remove pizza-making from the place of growing tomatoes, whose historic hearth of the pizza oven had been reproduced first in the 1940s in America, but iconically lingered as an designation of the fresh-baked, if not an atavistic survival in the food industry. The push-back of the local origins of pizza-making as an art, and a traditional one, transcends the currents of Italian out-migration, but seeks to affirm a touchstone of global craft and cuisine.

The survival of the aura of the hearth disguised its ready mobility, across oceans and indeed to any site, to be sure, affording temperatures far higher than a baking oven, conjured usually in brick, if developed as a site for warming up slices that tasted fresh, and for defrosting disks of frozen dough; the diffusion of pizza globally had threatened a sense of alienation, and the rapid recession of any sense of pizza as a local food in the mirror of global memory. If Walter Benjamin was so intrigued by Naples’ relation to food to suggest that families in the million residents of the city saved money for the yearly Piedigrotta festival with the dedication with which Germans would buy life insurance policies, or against accidents, the consumption of pizza provides more than a restorative ritual but a sense of communing with deep traditions, and indeed affirming national ties. And so nineteenth century admirers of Italy turned to the pizza, with a sense of recognition, to celebrate the sprezzatura and elegance of the food produced at high temperatures and the satisfaction that it brought as a genius specific to the place.

We can already see some continuity in the certification with the pride of place pizza-making occupied a place of prominence in Francesco de Bourcardo’s lavishly printed work of Neapolitan customs of 1857 that, several years before his far more ascetic cousin from Basel, Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, canonized the univeral man and corpus of Renaissance art as a product of a new individualistic political geography of city states of “Italy,” a region he contrasted to the mass culture of mid-nineteenth century Europe. And yet, the mass appeal of pizza has provided the taste that perhaps won out in the end, a victory of southern Italian tastes whose blend of rustic tomatoes and hearty spices lie far from the connoisseurship the trained observer would be able to study its art or to “detect the modern political spirit of Europe,” or the foods of Renato Guttoso or Elizabeth David, but a populism the Swiss art historian was less interested to include in his account of a Renaissance.

The status pizza holds as a cultural monument to culinary immigration or as a crowd-pleaser endures. And it will endure: the improvised pies long seen as a sign of bravado in conditions of duress at southern sea ports, the satisfaction of a simple pasto for those on the run without time for a full meal service, was difficult to see as a cultural monument by many, but a street food that migrated a tavola in the twentieth century. In ways, the elevation of the pizza-maker as a monument of Italian cooking, and of Italian culture, rewrote not only the global currency of pizza, but the restored pizza to pride of place among national monuments of a sort that Francesco de Bourcard, unlike his cousin, was able to appreciate. The Swiss cultural historian whose work had channelled the idea of a Renaissance to scholarship, the Basel patrician Jacob Burckhardt, had condensed from three moths in central and northern Italy in 1838, studiously avoiding the south, with a diligence continued in returns below the Alps in his long life as a historian and public figure, as well as an intellectual; Naples remained conspicuous by its absence from the fierce passions he aw in the cradle of modernity, effecting art–sculpture and painting, and architecture–in an ennoblement of mind prominently associated with kultur or cultural formation, a transcendent effect of the subjectivity of the universal man.”

It was not that the uomo universale, overcoming the constraints of place, time and nation, did not eat; universality was imagined to tap a vein of inspiration far removed from the material world. In contrast, his fellow Basilean Francesco de Bourcard willingly indulged in the pastries, food, and varieties of sweets available in his adopted city. De Bourcard, if a northern gourmand by family lineage, celebrated the Neapolitan theater as a true ex-pat gone native: among the customs that catalogued in encyclopedic fashion, the trusty pizzaiuolo braving the cold in his warming capotto was almost a counterpart to the Renaissance Man. The pizza seller was poised, stolidly, offering to use a sharpened knife above a stack of freshly baked pies. No doubt de Bourcard himself readily indulged in piazza, and even esteemed erudite Neapolitans as Giambattista Vico partook–especially those who, like Vico, had no fixed jobs at the University, and appreciated food on the go, a convenience for those who might appreciate the pizzas sold by itinerant bakers, stoves balanced o their heads and wrapped in wet towels, perhaps forcing the partially employed philosopher to chose between scholarly debates on the healthiness of tomatoes, a question recently debated by botanists and cooks, and the acceptance of tomatoes as staples of in Neapolitan cuisine as he confronted th warm wares of ambulatory artisans hawking a meal of warm bread. If Frascari entertained Vico’s own search for a “sentient solution” to debates about the tomato’s toxicity and harmful effects and the metaphysics of making food into a social rite–

–the pizza might have provided an early instance of the serum-factum, a folk-recipe of sorts in the head o the Pizzaiolo, but a metaphysics of the edible, releasing himself from rational fears as to the edible nature of the New World fruit by enjoying the transformed product remade by the knowledge of the street sellers of Naples who sold this new innovation of garnished Mediterranean flat breads as a manifestation of the genius loci. (How many part-time lecturers or graduate students subsisting on mediocre pizza can reach up to the model of the Neapolitan philosopher for some consolation, even if the undoubtedly canned tomatoes in their pies are ever so fresh?). The sentient solution of the good taste of locally grown tomatoes was the basis to dispatch learned botanists as Luca Ghini, Mattioni, and Ulysses Aldrovandi.

Although the Swiss emigre Francesco had in fact been born in Naples, he was no immigrant. If cast as from a distinct non-native elite, he hardly occupied the margins of Neapolitan society as the grandson of the Marshall of the Spanish King in Naples. But seeking to define himself as a local, or boost his adopted home to deserved status, he poured his journalistic efforts into this work of local history, following Vico much more than Jacob’s esteemed teacher, Ranke. If Jacob Bucrkhardt’s work was known for its collation of photographs of artworks in its later editions, Francesco refused to spare cost or attention to a work he saw as “useful in its literary expression, beautiful in artistic appearance, or the luxury of its binding.” What Benedetto Croce saw as a neglected if authoritative work of local cultural history that promoted the local color of a city Jacob B. had rather unconscionably omitted, with deep effects on the cultural imagination and tourist trade, and did so in striking colors that were designed to stimulate interest by aquatints.

Francesco de Bourcard had crafted a compendious and colorfully illustrated catalogue of local professions after the maxim of a model of Jacob’s cultural history–the dictum of independence of the Florentine historian and second chancellor Niccolò Machiavelli, “scrivete i vostri costumi, se volete la vostra storia.” He affirmed a return to local color, which was emblematized by pizza. Did Croce’s attention recognize how de Bourcard seeks to engage, consciously or unconsciously, Jakob’s conviction of the contribution of northern cities as the sources of transcendental art with an aesthetic purchase that could not be rooted in space or time, but belonged to the global civilization and seemed the ursprung of the modern? Jacob Burckhardt’s Civilization was famously unkind to Naples, and Francesco inverted the very claims of historical modernity by the historical validity of custom; he didn’t need to cite Giambattista Vico’s identity of what humans made and historical truth–the “factum” was the “verum”–and among the factum included the baked, in his own affirmation of pizza-making, long before Glenn Adamson wrote, as a craft.

The “world-spirit” that historian Jacob Burckhardt detected in the political independence of city life was confined for the most part to Northern Italy, perhaps replicating the prejudices of Italians he encountered in Milan, Florence, and Ravenna, not to mention Geneva. But his focus on the northern “city states” h a deep if less known counterpart in the local flourishing of Neapolitan culture even under Spanish dominance of the Bourbon monarchs, who Francesco de Bourcard’s uncle had so proudly served as a military officer. The Neapolitan pizzauolo provided a prominent place in the hundred color watercolored lithographs of the book of “colore locale,” but also a hinge from the city that hinted its ties to a globalized world that lay at the intersection with global trade.

If the image was local, it featured food salesmen hawking “fichi d’India” (prickly pears), juicy fibrous fruits native to Mexico now grown across Sicily and Catania, and peanuts (“nocelle americane“). Such local trades placed Naples at the center of a network of global food trade, if not an early globalization, the first testimonies to pizza being tied to the sailors who devoured it without cheese–marinara, or with anchovies–at Naples’ Mediterranean port, where the early arrival of cultivated tomatoes–even if naturalist Costanzo Felice admitted, in a terse confession of a work of alleged objectivity, that the yellow and red fruit are “to my taste, look much better than they taste” [al mio gusto, è pui’ presto bello che buono]; tomato sauce was first elevated to a recipe book for modern cooking in the 1690s in Naples, alla Spagnuola–Spanish style. The tomatoes that would become regulated to protect regional growth guaranteed as “DOC”–“denominazione di origine controllata e garantita“–in the region were imports.

Yet pizza became a pre-eminently Neapolitan food by the mid-nineteenth century, as vineyards of tomatoes dominated the Vesuvian plain. The ambulatory “pizza -man” was soon replaced at the cusp of modernity in a newly motorized form in postwar Naples as navigating the local streets atop a motorino—

–but was perhaps, we fear, only a prototype of an ever-widening scope of delivery–recently rolled out in drone delivery–in the ever-expanding space of fast-furious commercial transactions where all sold melts to air, unmanned drones being the ultimate sublimation of the urban face-to-face gemeinschaft, in a widening scope of delivery whose IS interfaces provide new records of fresh delivery places pizza in a cash nexus of the increased uncertainty and agitation of social relations, stretched so thin to be alienated from proprietary recipes let alone any sense of the local, as the pizza was accepted, embraced, and reprocessed within first the American and then the global food-industry, with the translation and transformation of the pizza to a food of machine-cut vegetables linked by the glue of processed cheese, that has shifted the “arts” of pizza-making to a Taylorist assembly line of food prep, removed from the kitchen or hearth, but assembled by folks working in what might be rather mechanized unskilled jobs.

The globalization of the prepared food is dissolved in money relations in markets expanding on the smooth surface by promising geolocated drops of customized orders of comfort food, fresh from the oven, the interfaces of unmanned drones guarantee to break record delivery times of piping hot “artisan” pies. The drone-delivery services, improbably named after the fossilized non-flying bird, in 2015 promised a new frontier of franchising unmanned pizza delivery systems, its software capturing the contradictions of globalized personal pie.

Drone Pizza Delivery/Business Insider

2. The global and domestic popularity of pizza has been greatly accentuated during the recent pandemic and the expansion of order-in foods to counteract isolation and working from home. But integrated delivery platforms and food preparation assembly-lines of multi-nationals dilute all proprietary relations to pizza promising global access: in modern riff on bread and circuses, is this proof the market met contentment in a promise of umami satisfaction? The unmanned drones, leaving the not-so-Italian-anyway Dodo Pizza’s Syktyvkar shop in northwestern Russia, have set record delivery times across Eurasia, breaking a frontier of “local” pizza delivery and redefining ‘pie in the sky; pizza is an apt business model to engineer incentivized IS interfaces far removed from the face-to-face, in a profaning of the local.

The praise Croce reserved for the “magnificence” of Francesco de Bourcard’s elegantly illustrated tomes responded to the omission of Naples from the other Burckhardt’s near-omission of Naples from his own richly illustrated study of book on Renaissance civilization, in which the cultural historian whose shadow must have laid across de Bourcard’s life had expanded his popular Cicerone–a work on the geography of Renaissance art that would later be used to track a sense of cultural expression–“Der kunst aber will ewig sein“–that emphasized values of universality and everlasting endurance in its common ideals and forms of expression. The centrality of “costumi” radically shifted from the written records on which Burckhardt devoted so many hours in Basel’s library to privilege the sense of the fleeting as uncovering the local meaning and truths that Burckhardt believed he could assemble from historical fragments sense of Italy. The city-states of the Renaissance were intellectually severed from food, for Burckhardt, who sought a higher form of kultur in their eager exit from medieval corporatism and individual freedom in the floating of a treasured sense of individuality that wafted far above the material in the enjoyment of artworks able to communicate passionate intensity and “open a world of intense feeling, beauty, strength, and happiness”–as a second level of creation, akin to the theological creation, a tradition of tranquil transcendence removed from the messiness of. the material marketplace. If Jakob had, at the start of his career, left Basel to work as the Parisian correspondent for the Basler Zeitung, in the 1840s, before pursuing the study of history, that may have left a deep imprint on his aesthetic tastes, in his attack on the salon as arbiter of aesthetic tastes, de Boucard developed his sense as a native information of Naples in his much longer journalistic career for the Corriere del Mattino. The later enterprise to include a hundred watercolor vignettes within the urban compendium was an ethnography of the local, rooted in the city, even if the sales of pizza have since spread not only elsewhere in Italy, but across the globe, to the extent that pizza might constitute a universal food of globalization.

The prominence of pizza as a signifier of imaginative invention, from the simplest of local produce, cultivation, pressing of oil, and milled flour, remediated the absence of attention to the pizza at its site of ‘birth,’ against the growing global currency of the pizza as a heavily subsidized and engineered food “product,” using part-skim shredded mozzarella devised in America, mass-produced tomato puree posing as a “vegetable” in school lunches, and assembly of frozen pies at a fraction of cost. The redesign of frozen pizzas as a global commodity, blurring borders, seems to affirm the absence of the local and the growth of a global flattening of sorts across borders or local foods, the food of the global that leads local cognoscenti to reveal sophistication in prizing redoubts where pizza is still hand made.

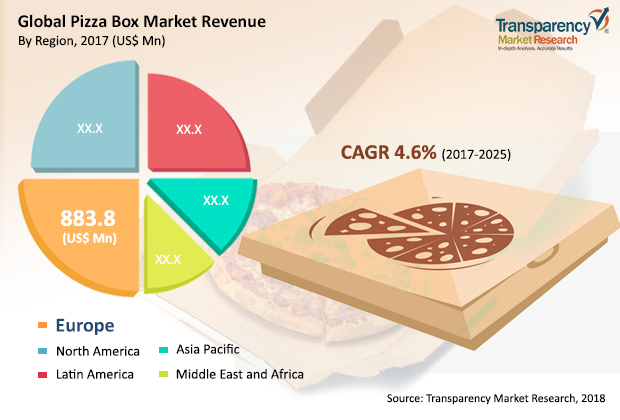

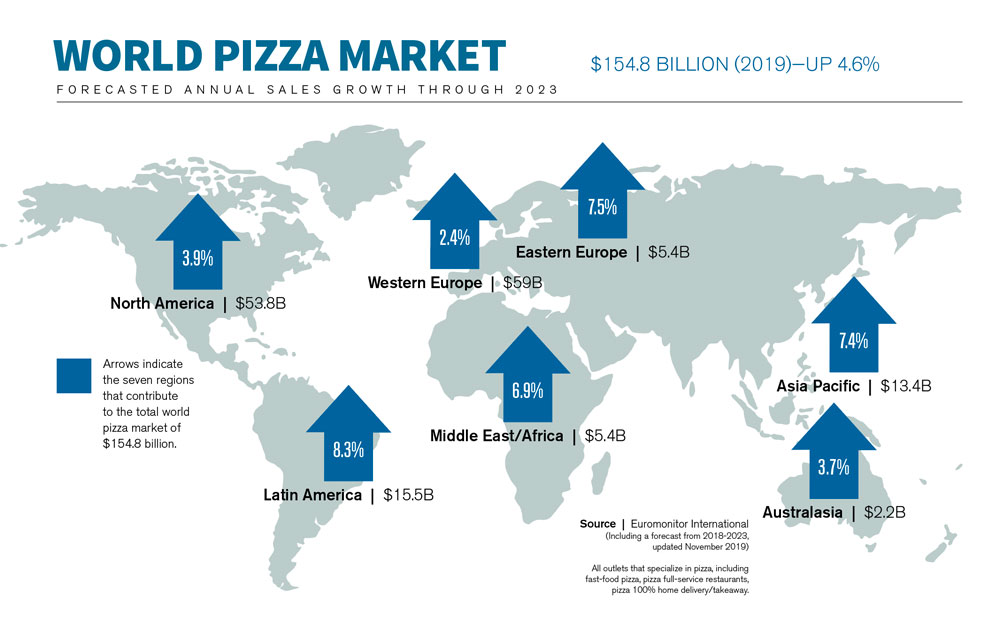

For in this context, as frozen pizza totaled a full tenth of all frozen food sales in the United States by 2010, topping $3.2 billion, a share forecast to surpass $20 billion by 2025, the non-local pizza shipped, sold, and favored across the world that has subtracted fantasy or creativity from our collective culinary horizons has brought us to remap the pizza within the Italian peninsula, and to champion the tradition of blending tomato sauce on bread as a birthplace of a global food. For the expanding consumption of pizza seemed to have proved that the world was indeed flat, delivered not only from a flat box, but reducing the globe to a pie chart of slices of global revenue, less inspired by invention than the marketing strategies that had allowed profits to grow along global “regions,” stripped of much local variation in fresh foods or fantasy of the arranging freshly cooked ingredients on a pie.

Placing pizza-making as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in Naples may provoke whimsical smiles from Americans habituated to pizza as a go-to to-go food arriving in large cardboard boxes. And in the context of the globalization of pizza as a food delivered to markets worldwide, the reclaiming of a stolen identity comes late in the game indeed, akin to the restoration of the wealth and prosperity actively transferred from Palermo and Naples to Turin after their invasion joined them to the Kingdom of Victor Emanuele in 1860–recasting of the violence and backwardness, violence, and immorality of the south framed during Italy’s unification. Recognizing the local contribution of pizza-making, Italians were reminded, as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in the shadow of its globalization was a national affair, rebuking the food’s global ubiquity, and pinning this most consumed food to one place on the map.

The nation got behind what was a point of local pride for the 3,000 pizzaiuoli who had declared themselves part of the “True Pizza-Makers of Naples” (Pizzaiuoli Veraci di Napoli) in local terms, as if longstanding lack of recognition remedied–affirming the global organization’s role and importance in defending pizza-making as an institution of truly global export of global import.

Yet the economic need to assert the centrality of the city of Naples as a sort of fons et origo for the orgy of global consumption of pizza is above all a reaction to the extent to which global consumption has transformed pizza-making as an art; while pizza is questionably able to inculcate moral virtue, the virtue of preserving the traditions of pizza making as an art was what UNESCO affirmed: not the ingredients but transmission of a pie made by the “hands, heart and soul of the pizzaiuolo,” in the words of one Neapolitan, as an alchemical stretching and turning of dough as much as its garnishing with cheese, arising from humble beginnings of feeding that morphed to satisfying a demand for the readiness whose reach, feed by food delivery apps during the global pandemic.

Has not the globalization of pizza perforce only further displaced it from its geographic origins or the locally produced foods it once expressed, so that the multiple origins of different varieties of pizza are now entertained, and the economic need to affirm the cultural capital of pizza in the depressed south becomes a real demand for the local food industry in a city whose appeals in part revolves on the perfection of pizza that is ordered in its pizzerie and restaurants? The demand to identify pizza as a patrimony of humanity responded to the remaking of pizza, long after the food’s outmigration from the Campagna or region of Naples, to affirm the artisanal traditions of pizza-making as a local tradition. The acknowledgement of pizza-making as a local craft that belonged to humanity–rather than a globalized food able to move, as if frictionlessly, across the globe, on networks of food-distribution by -engineering–claimed a sense of meaning as if pizza demanded reclaiming as a form of Intellectual Property, as if this would boost the lagging economy of the mezzogiorno, and canonically affirm the patrimony of pizza as a local good, now that it had gained global popularity as able to be discovered anywhere on the map.

The range of comments that tourists of Anglophone persuasions now bring to Neapolitan pizzas even as they make pilgrimages of quasi-spiritual zeal–“You can’t pick really it up”; “Can’t they just make it crisper?”–provokes frequent back-and forth from the locals who don’t understand the reluctance of visitors to use silverware, or to order a personal pie, but the entitled ownership of the pizza as American–or a recognized version of what was an Italian-American food–has become almost a cultural tussle over expectations about what is called a pizza, and what one wants to find in a pie: a meal, or a rush of super-refined flour coated with a dispersion of cheese and healthy toppings, often assembled in industrial terms en masse.

The taste that had become associated with the local For the pizza was long ago elevated as a new sign of the local, a slow food that had origins in the eighteenth century, if not long earlier, as a from of making meaning, whose preparation was privileged as a sign of the local customs if not moral economy of bread–if the copiously illustrated 1832 treatise on Neapolitan gesture preferred describing the gluttony of Neapolitans for food foregrounded roasted “Indian corn,” alluringly sold from boiling cauldrons for a soldo, and mimed for barter by the ear by female street vendors, or the macaroni eaters devouring platefuls of pasta removed directly from cauldrons of water, suspending six pounds pasta “twisting and writing . . . as if they were descending from heaven” above their open throats “in the correct perpendicular position,” that entered the open esophagus without an interval between mouthfuls, pizza was not featured as so gesturally rich. Pizza was less theatrically eaten, but the absence of the dance of selling pizza reserved to ambulatory vendors, by balancing cylindrical coal stoves on their heads with shelves that warmed round bread boasting the appetizing nature of the tomatoes Europe had largely disdained as inedible led the Neapolitan by adoption, Francesco de Bourcard, to describe the variety of pizzas sold on Naples’s streets by 1853 as nonetheless a central part of everyday Neapolitan life. The Swiss patrician transplant from Basel’s patrician families was not slumming when he boasted his adopted city to sell pizzas from tomatoes increasingly used for cooking, garlic, oil, and oregano, in varieties as well as anchovies, lard, grated cheese, and basil, or thinly sliced mozzarella, prosciutto, or clams, whose base was not only tomato–a resilience and some sprezzatura predating pizza rossa or preparing a rich tomato base. Tossing pizza dough demanded skill, was less a gestural dialogue, and indeed far less a transatlantic import than a remaking of the meaning and preparation of pizza as a pie.

The distance of these appetizing pies marketed in the pizza chains and stores that dot New York streets are not only different from the pies made in Italy (or born in Naples), but a food that celebrate the upscale indulgence pizza continues to provide as a gigantic confection of pleasurable indulgence, even with the illusion of healthy vegetables.

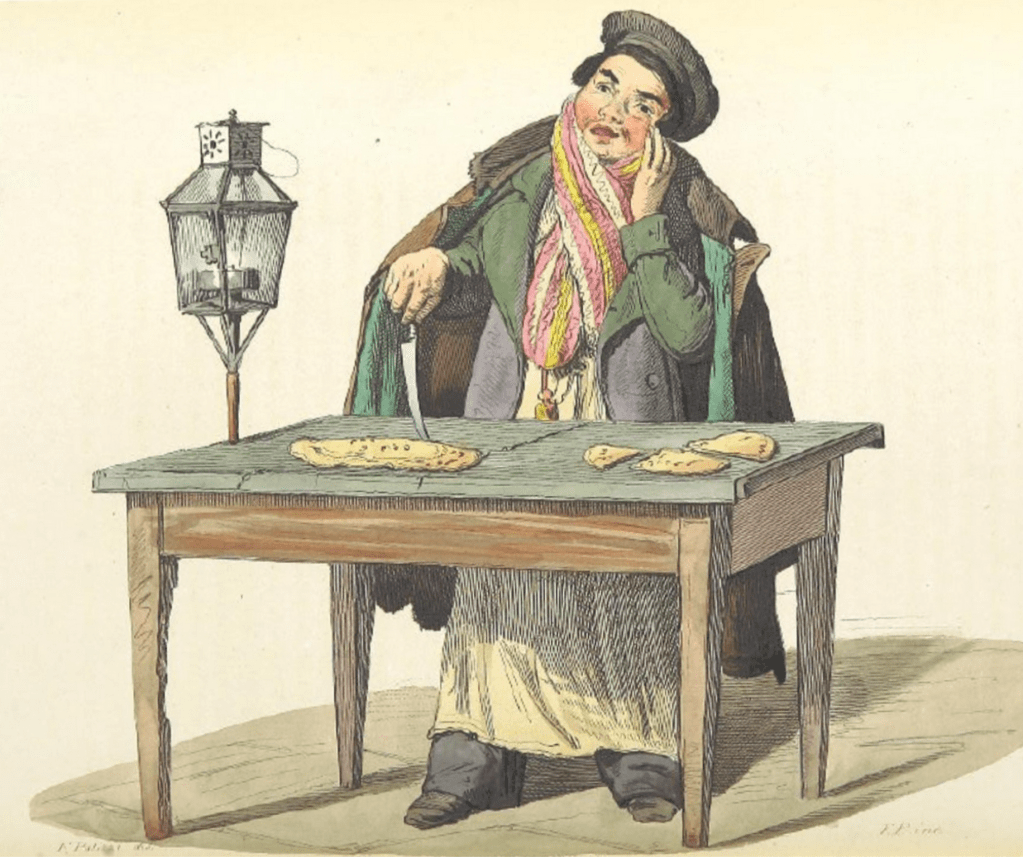

3. The distance of such upscale chains from Neapolitan pizzas is of course not only geographic, but suggests a new land of pizza, as much as a new pizza for a New World of food consumption. The Basel patrician transplant Francesco de Bourcard, who loved his adopted city of Naples, respected by local historians, including Croce, for his fluency with local manners–no doubt in contrast with the uncle who had idolized northern Italy as a sight of the transmission of a vital classical heritage of civic independence, by tapping into the street life and customs of Naples to fill a copious catalogue of encomiastic character that speaks tot he modern pizza lover in unique ways. The prominent place Bourcard gave to the popularity of pizza-making is one of the first references to a custom Vico may himself have appreciated and knew well, even if it fell beneath Jacob’s wide ranging purview–for Francesco, the streets of Naples offered an important alternative to Basel’s library. In keeping with its focus on the customs of his adopted city of Napes, the younger de Bourcard quite prominently featured a pizza seller as central part of Naples’ fabric and local economy, broadcasting the figure of the pizzaiuolo to a lettered tradition that prefigured the inclusion of pizza-sellers among the images of street scenes that were widely sold in nineteenth century Naples to portray the repertory of urban profession so distinctive to the south, long before pizza was widely consumed outside the Campania, and before many Europeans ate tomatoes or viewed the nightshades as an edible fruit.

The inexpensive production of tomatoes on the volcanic plains of Campania may have allowed them to produce a satisfactory meal or tasty treat. The third generation of Swiss Burckhardts residing in Naples, since his grandfather Emmanuele (1744-1820) had arrived in service to Ferdinand IV, founding a line of Burckhardts never to return to the old Basel manse, would have despaired at the apparent provincialism with which Jacob looked down his nose at Norman Italy in his account of “rediscovery” of classical culture and modern politics. For Jacob Burckhardt, the inhabitants of Naples remained in another age, “destitute of will” and stuck in Spanish ways, less economically or commercially adroit, without elegance of movement, and diminished by criminality and impiety arising from the “cheapness of human life”: Francesco’s celebration of the democracy of everyday Naples as if a rapprochement of Naples to cultural history, if not Renaissance art, citing the three variety of Neapolitan pizza, as a cicerone of the local than connoisseur of”high” art Jacob saw as fundamental to an individual’s cultural formation.

The place of pizza as a cultural monument was in other words long contested, and up for debate. Francesco de Bourcard did not praise pizza was as a democratic food of sailors who preferred marinara, but a sense of deep democracy comes through in his discussion of the pizzaiuolo who serves this peasant bread as the needed snack for working Neapolitans, even if he hawked his wares with few gestures. Is the pizza man who hawks several varieties of pizza a figure of modernity avant la lettre? De Bourcard’s pizza-man is wistfully rooted in place with no ken of coming global appeal: a ruddy pizzaiuolo hawks wares on the side of the street, almost a tragic figure offering slices of pizza and calzone by a gas lamp, well-insulated in a cappotto, not surrounded by crowds. Behind his wooden table from which he sold pizza, his apparent melancholy stands in sharp contrast and is unlike the remaking of pizza as a global commodity, at the intersection of food markets and space, driven by the comfort food or the pleasures offered by a marginal trade. De Boucard elevated the cultural figure of the pizza maker on Neapolitan streets, as part of the local social fabric of Naples, in a book on “customs” of Naples and Neapolitans echoing Vico in its insistence on telling the history of the usi e costumi. Perhaps the theatricality of the pizza-maker who spins, throws, and tosses dough was so concealed in its gestures that they hardly bore revealing as a social type.

The resulting urban anthropology of the city that his removed cousin, the historian Jacob Burckhardt, conspicuously omitted from his study of the Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy–or indeed cited Naples often in his panoramic purview of the arts and sciences in Die Cultur. While the streets of Naples that the local erudite de Bourcard sketched as populated by pizzaiuoli and other merchants were eviscerated in the 1880s, in large part by public health fears of cholera, by Italy’s first monarch, as if the preference for pizza by his consort, Queen Margherita, compensated for emptying the city’s hold heart–vico delle Campane, vico Rotto San Carlo, vico Sant’Antonio Abate–that were replaced by large boulevards by the 1890s, destroying many of the houses of pizzeria founded since 1850. The pizza was a form of one’s orientation to Naples’ streets, and street life, after all, sold by vendors who carried coal ovens wrapped in balanced under coils of wet towels; pizza was a local variation on Mediterranean round bread. The prized pizza was heir to the bread all Roman subjects were all entitled, a democratic food of Naples unlike those Romans graded breads by social rank, from the panis civilis to which all citizens, panis plebeius of plebs and panis sordidus of slaves, to the panis palatius of the Caesars; pizza was a step above the panis gradilis distributed for free on the steps of Rome’s Coliseum.

Even without cheese, pizza was as sort of social glue, a food of the piazza, its making no doubt as important as the collective nature of its consumption, and the common street scene of pizza-sellers eagerly hawking their edible wares and freshly baked foods, still warm from the oven. Was pizza the glue of a silent social compact, born of a sense of the dignity of the consumption of local foods, long before it was sold in multiple variations for upscale Americans at Whole Foods, trying to address consumers seeking the low-calorie satisfying dinner fix?

Perhaps no gestures were required for the Neapolitan hawking pizza to passersby for ready consumption in the 1830s was sold as one of the picturesque “street-views” of professions in Naples, in a precursor to the pizza slice, chef’s hat, and long white apron, occupying a clear social role held in an urban environment–and conducting a quintessential face-to-face encounter on a Neapolitan street promising a populist mini-meal, prepared with pride even if served on a improvised wooden stand.

As the most democratic form of food, the spread of pizza seemed a sort of social equivalence, and a social glue even if the binding agent is shredded low-fat mozzarella coated with vegetable oil. Pizza has become far flatter as pizza chains have gained increasing profits, artisanal shops claiming an imaginary pedigree of the local and the fresh, or promising a reduced sense of fresh, as if the pie has come to be a platform of tomatoey tang from the oven provides a basis to promote savoring freshness in a world already inundated with fast food, an industry that runs on recognizability of flavors and tastes.

The open-mouthed winsome pizzaiuolo seeking customers hardly suggests a high art, but as a food of transience, for those on the run, before the back door of a bakery, emerged from an unseen kitchen, ready to cut slices on his wooden plank from freshly cooked calzoni to all passersby, an egalitarian food in a city of pretensions to upper class elegance in the early nineteenth century, in an unintentionally mournful image that seems, when viewed through the lens of history, to be read as a cry for pizza’s lost soul given the current remove of pizza not only from history but from localized production.

It is hard to tell what the distinctively garbed yellow vested pizzaiolo is serving up, but it is definitely by slice–“New York” style–and ready for quick consumption, probably ferried right out of the oven lying behind the door before which he stands, hawking his wears as loudly as his choker allows without loosing decorum. I’d venture it was bearing anchovy fillets and onions, two conspicuous toppings, and it doesn’t seem to show any of the distinctive tomato sauce that we most always tie to pizza today. The important thing is that it is hot, fresh from the oven, and good.

Continue reading