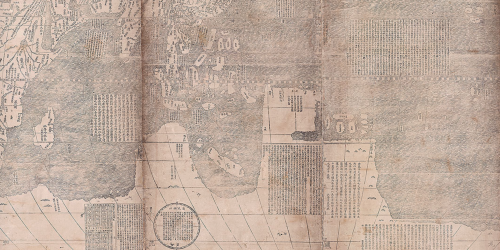

The map “Java La Grande,” an imagined continent that invited close inspection from viewers, gives new meaning to the assertion that the map is the territory. For although this territory never existed, it was mapped: the medieval construction of the antipodes, a mode to balance the continents, was an artifact of early modern European cartography of considerable duration and lasting power. When Matteo Ricci mapped the world’s regions in 1607 for his Chinese hosts, his copy of the Ortelian map included a large discussion of “Guinea” as a place not studied or known well by Europeans, and perhaps an independent island or attached to the southern pole–albeit one that was not known to be inhabited, and with which little if any contact had been made. In this sense, Guinea remained an outlier in the age of discoveries, and a somewhat rare blank spot on Ricci’s global map.

As an artifact with an esteemed cartographical lineage, the image of the continental landmass continued to be mapped into existence by the mid-nineteenth century. But its appearance in the below chromolithograph of a Renaissance map from the library of baronet Sir Thomas Philips was declared the first map ever recorded of nothing less than the very continent of Australia, as ostensibly witnessed by the Portuguese sailors in the pristine state of nature in which they had allegedly first discovered it. The map was prized as an image of initial discovery.

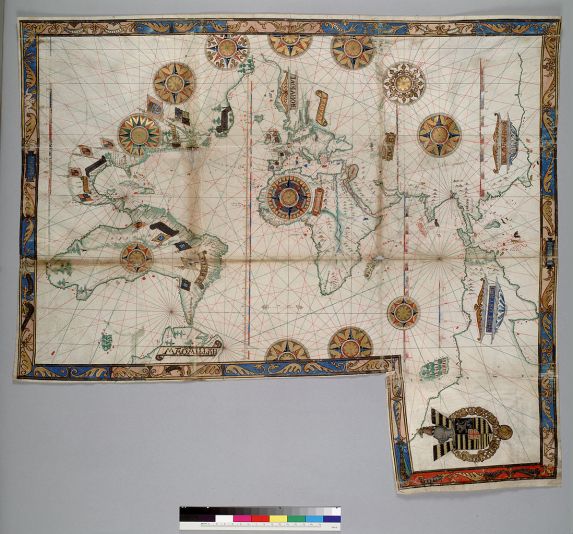

The anonymous artist-cartographer recorded the recession of space in this map, which as it recedes its inhabitants are registered in brownish tracery, foregrounded the idyllic life of this entirely unknown land. You get the idea of arriving in a region taken as Australia that was the entrance to a landscape of untold wonders in the map of “Java La Grande” designed for Nicolas Vallard’s nautical atlas of 1547 in Dieppe, a center for the diffusion of Portuguese nautical charts for an elite audience of European nobility, reproduced in this 1856 facsimile now stored among the jewels of the Australian National Library.

The pictorial landscape chart was a luxury embellishment of the sorts of rutters that were drawn with artists of local topography. The material object was prized and promoted by Phillips as a record of the first encounter with the territory of Australia, reproduced with such painstaking care in the mid-nineteenth century as a chromolithograph from the first baronet’s library when he tried to disperse the Vallard atlas and other early modern books to the British Library, inspiring the reproduction of the map, which he mis-titled “The First Map of Australia,” to promote the value of his collection The map made for the Vallard atlas by an unknown painter was probably valued because it seems to record an image of Portuguese encounter with the indigenous inhabitants of Australia. As part of the corpus of Dieppe charts that were, unlike earlier nautical maps, pictorial syntheses Portuguese discoveries of almost ethnographic qualitative richness as depictions of inhabitants for elite audiences, the image has provided a touchstone of a vanished native culture that is particularly powerful as an imagined precursor of the discovery of Australia, valued as an image of imagined contact. The Vallard map possesses the distinctively attractive qualitative lushness peculiar even to the Dieppe school of which it forms part.

The identification of Australia with the mythical “Java La Grande” is not entirely rooted in geographic fancy. Java La Grande was described by Marco Polo as the largest island in the world–but reflected some recognition of this unknown landmass that extended to Antarctica, and recurs in the Dieppe maps as a cosmographical idée fixe as not an island, but terra firma: at the same time as the current-Java was described by geographers of the 1540s, the Dieppe school identified La Grande Jave as an extension of the Antarctic Terra Australis, and it was taken as an early evidence of the southern continent’s early discovery.

The map became taken as the territory. And so why not preserve this map as a treasure of the collections of the Australian National Library, even if it is a nineteenth-century copy–and quite a faithful one–of a map that represented quite a different imagined land?

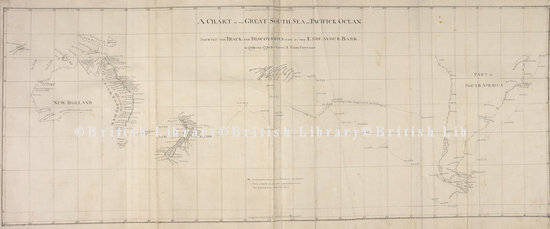

Early identified as the first map made of the continent, this map provided a list of coastal ports that an artist proceeded to fill in with imagined views of inhabitants advancing as if to greet newly arriving visitors with arms literally open in welcoming signs, if not in a ritual procession. The intensity of play of imagination is evident in contrast to a later 1777 nautical map showing two ships’ circumnavigation of the world under the command of Antoine de Bougainville, whose cartographer constrained himself to parts of the Eastern coast observed with sufficient detail to establish for readers, allowing far more local detail to the as yet unsettled continent, and confined himself to the better-known shorelines of its coast:

Yet what was later prized as the “first map of Australia” is distinct from a roughly contemporary 1543 chart by Guillaume Brouscon of the same school in Dieppe, who synthesized information from prized Portuguese charts to a new audience of landlocked European nobles. This earlier map devoted a considerable space to “Java La Grande,” extending the rectangular format of the engraved global projections later standardized after their printing by Mercator and Ortelius, if already adopted by humanist geographers, and offering far more detailed depictions of the settled interior than nautical charts that confine themselves to coastal towns. The almost ornamental multiplication of compass roses that proliferate like heraldic crests on this map suggest its ornamental nature in a corpus of maps.

A fair amount of extension of the topos of cartographical invention or the mediation of new discoveries that animated these excited atlases of the late 1540s in Dieppe are reflected the map of Java le Grand among the 56 maps that the nautical sailor and self-styled cosmographer Guillaume le Testu included in his Comosgraphie Universelle, selon les Navigateurs, tant anciens que modernes. The work’s comprehensive claims derived from its use of a range of Spanish and Portuguese charts together with maps of his own design that synthesized recent maps of the Americas:

He readily presented this map as rife with cartographical invention, as well as following cartographical conventions, as if suggesting the frequent embellishment of persuasive or recognizable detail in maps, more than the license his own achievements in mapping much of the Americas may have merited: “what I have marked and depicted is only by imagination, and I have not noted or remarked on any of the commodities or incommodities of the place, nor its mountains, rivers or other things; for there has never yet been any man who has made a certain discovery of it.” The absence of “certain discovery” is an odd juxtaposition with his own discoveries, and the admission of the absence of such “certain discovery ” led to a land that was entitled to be created by the imagination.

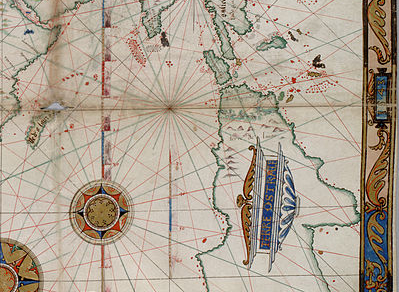

The imagined land’s expanse was documented as well in nautical maps limited to shorelines, offering far less qualitative local details than the expanse of its coast, but suggesting in an enticing fashion its expanse, and multiplying elegant compass-roses as if for an excuse to include more gold leaf, as a sophisticated ornamental boundary of decorative motifs:

The narwhale rising from the waters just off the coast, shown without regard for the scale of islands or inlets on the coast, paired with a resting bobcat or lynx. This image of the Eastern coast of Australia is only slightly embellished from Vallard’s original.

It’s been recently suggested that the inventive maps of the Dieppe school fabricated the entire continent out of geographic legends to evoke a potential land for colonization by the French monarch, as in this earlier 1566 Desliens world-map. Indeed, these deluxe manuscripts reflect the broader interest of the materializing of wealth on the map, and, on the surface, seem to cast Java La Grande as something of the potential equivalent of what the Spaniards found in the Americas.

The notion of this fabrication of continent seems absurd, but had confirmation in geographic theory. Java La Grande is projected as a land of potential conquest and wealth, and is a survival of medieval written geographies that was transposed to a recognizably modern cartographical form, if it antedated the imagined expansive island of Taprobana, identified with Madagascar but often shown as a land of wealth, and in ways moved this target of European interest further East toward the Spice Islands and Indonesia.

The exquisitely tangible nature of the contents of the Vallard map may give some confirmation to its invention. The upper register of this first image of the original Vallard atlas, now in the Huntington library, showed the region’s aboriginal inhabitants in a monochrome hues of striking similarity to a cave-painting as proud hunters bearing spears:

The image now held in Canberra is a striking copy of this image of the inhabitants of Java le Grande, which featured its inhabitants in a procession across the newly mapped land:

The placement of initial folio perhaps as it was the most pressing communication of cartographical news–pays particular attention to the forms of habitation in Java, and the houses in which the inhabitants live and the palm-nuts on which they live: as if to embody the information displayed in disembodied form in later world map projections: in the years before Mercator’s Theatrum orbis terrarum, nautical charts concretized viewers’ material relation to spatial particularity.

The map offers something like a luxurious window into the newly discovered land for viewers to contemplate in ways that simple terrestrial projections did not allow.

The imagined continent of luxury and untold riches, filled with nutmeg and cloves as well as “idolatrous inhabitants,” made its way onto the globe by 1583, if somewhat assimilated to Antarctica:

This might explain the staying power of nautical charts, based on observational practices of sailors and possessing a clearer pedigree as transcriptions of space, into the seventeenth century. At the same time as material goods were arriving in Europe from west Africa and southeast Asia, maps provided something of a spatial catalogue to understand their arrival and place them somewhere in a lived topography, as much as they offered tools of orientation. Java La Grande was attractive as something of an evidence of the inhabitation of a region later identified with Australia, before the arrival of Captain Cook, in ways that depicted the inhabitants that occupied its expanse in something of a romantic light.