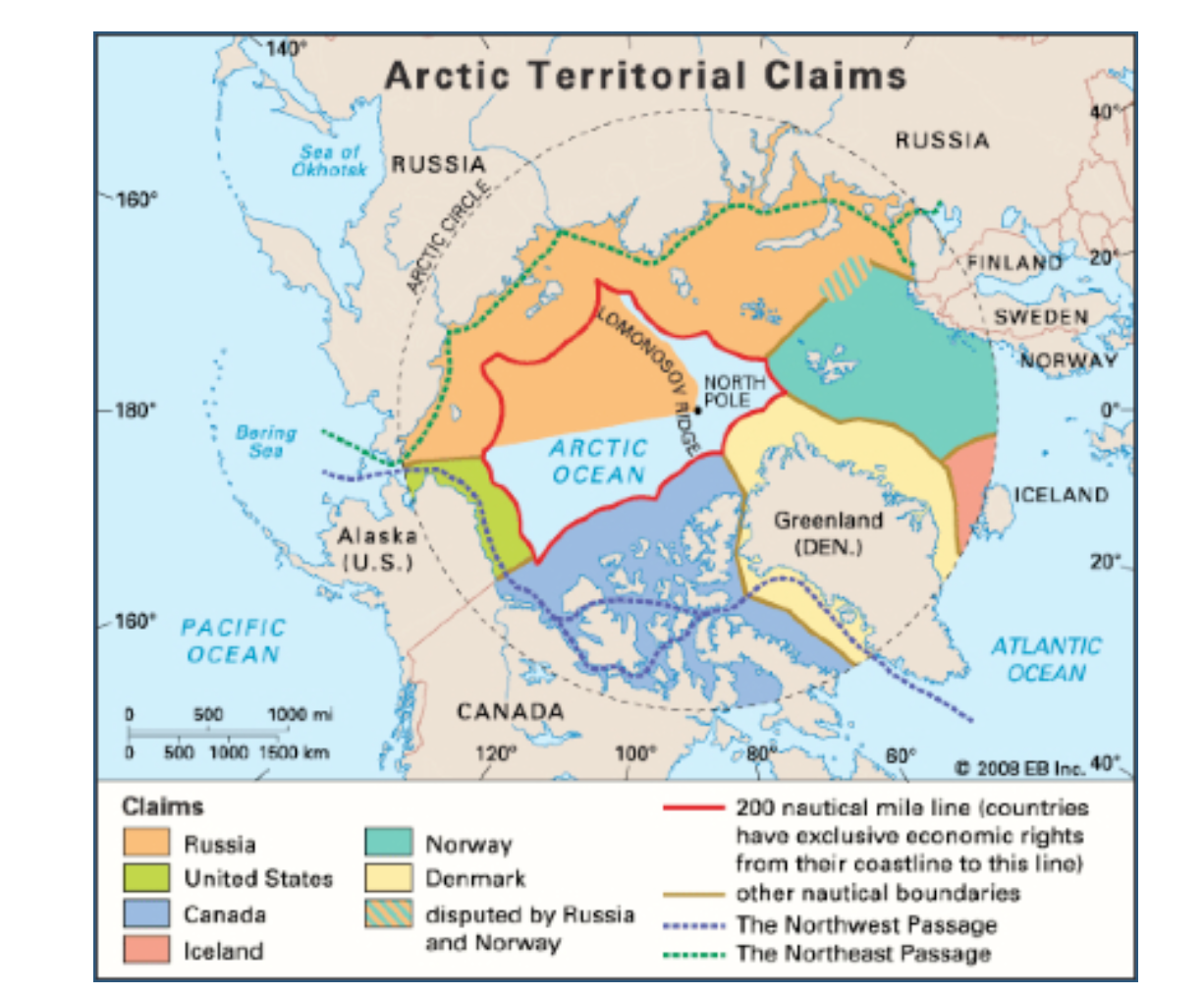

On our annual northward migration to Ottawa this December, we gathered around the unused fireplace in an unheated living room during the warmest Canadian Christmas in personal experience–as well as in the public record for Atlantic Canada, where local records for rainfall have surpassed all earlier recorded years. Perhaps because of this, discussion turned to ownership of the North Pole for the first time for some time, as what was formerly a featureless area of arctic ice has become, as a receding polar ice-sheet exposes possible sites of petroleum mining, to become an area of renewed land grabs and claims of territoriality, as their value for nations is primarily understood in a global market of energy prospecting.

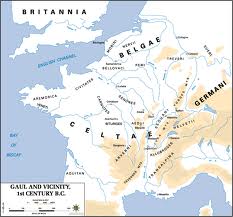

The story of the new mapping of territorial claims around the arctic ice cap goes back decades, to the exploration of offshore polar drilling, but the exposure of land raises new questions for mapping because boundaries of polar sovereignty are contested, even as oil companies have speculated by modeling sites of future exploration for petroleum deposits. In sharp contrast to the clear lines of sovereignty that were drawn along Antarctica, the ongoing disputes of the Arctic have become protracted indeed, only more contested as global warming and polar melting open the long-frozen shipping routes that have long been imagined across polar regions, opening up new fantasies and geographic imaginaries of globalization. While Antarctica remains sectorized with clear stability in the geopolitical maps per the C.I.A.’s World Factbook, the stability seven claims to ownership far less contested or open to international debate as no petroleum has been detected under the ice shelf, the southern lands that host McMurdo Station host stations occupied by sixteen governments, in a sort of tacit comity for goals of research, distributing rights but with both Russia and the United States refusing so far to recognize any as valid. And so although Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and UK are eager to claim regions as their own, as if everyone can have a slice of the frozen pie, the lack of contestation and minimal interest in the sector between 90 degrees west and 150 degrees west stands in contrast to the intense mapping and remapping of the North Pole.

Maps are long primarily used as strategic tools to assert land claims and sovereign bounds. But this may seem increasingly foolhardy in an age that is defined by globalization, and where global warming seems to threaten to further blur the staking out of sovereign divides. Is this only another reason to the multiplication of assertions of arctic claims to melting lands? Although one assumption circulated that the place was Canadian by birthright—birthright to the Arctic?–since it is so central to national mythistory.

But there’s as much validity for its claims as the more strident claim the explorer Artur Chilingarov made to justify his planting of a Russian tricolor in the murky ocean bed 2.5 miles below the North Pole, during the 2007 polar expedition of the Mir submarine, with the timeless claim of Soviet-era bluntness, “The Arctic has always been Russian.” Canadian PM Steven Harper did not hesitate a bit before decrying these claims to territoriality, warning his nation of the danger of Russian plans for incursions into the arctic in his tour of Canada’s North, thumping his chest and professing ongoing vigilance against Russia’s “imperial” arctic “imperial” as a national affront in addressing troops participating in military maneuvers off Baffin island as recently as in 2014.

Harper’s speech might have recalled the first proposal to carve pie-shaped regions in a sectorization of the North Pole first made by the early twentieth-century Canadian senator, the honorable Pascal Poirier, when he full-throatedly proposed to stake Canada’s sovereign claims to land “right up to the pole” and transform what had been a terra nullius into an image of objective territory seemed once again at stake. Poirier claimed jurisdictional contiguity in declaring “possession of all lands and islands situated in the north of the Dominion.” Poirier’s project of sectorizing the frozen arctic sea and its islands, first launched shortly after Peary’s polar expedition, has regained its relevance in an age of global warming, arctic melting and climate change. But the reaction to the expanding Arctic Ocean in a language of access to a market of commodities has inflected and infected his discussion of the rights of territoriality, in ways that have obscured the deeper collective problems and dilemmas that the eventuality of global warming–and arctic melting–broadly pose.

Encyclopedia Brittanica

The question of exactly where the arctic lies, and how it can be bounded within a territory, or, one supposes, how such an economically beneficial “good” that was part of how parts of the north pole might get away from Canada, has its roots in global warming–rather than in conquest. The dramatically rapid shrinkage of ice in the Arctic Sea has raised newly pressing issues of sovereignty; the widespread melting of arctic ice has made questions of the exploitation of its natural resources and potential routes of trade has made questions of the ownership of the Arctic ocean–the mapping of the territorial rights to the seas–increasingly pressing, as some 14 million square kilometers of Arctic Ocean have emerged not only as open for exploration, but as covering what has been estimated as 13% or more of total reserves of oil remaining to be discovered world wide.

The Economist

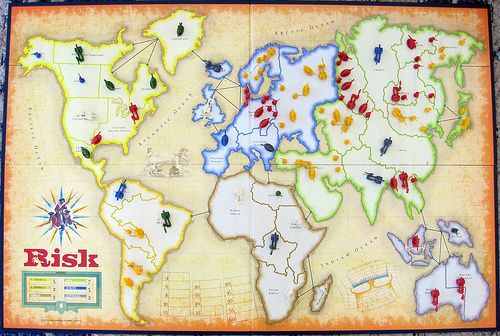

While it seemed unrelated to the ice melting from nearby roofs, or large puddles on the streets of Ottawa, conflicting and contested territorial claims that have recolored most maps of the Arctic so that its sectors recall the geopolitical boardgame RISK, that wonderful material artifact of the late Cold War. Rather than map the icy topography of the region as a suitably frosty blue, as Rand McNally would long have it, we now see contested sectors of the polar regions whose borderlands lie along the Lomonosov Ridge (which runs across the true pole itself). The division of the pole so that it looks like post-war Berlin is an inevitable outcome of the fact that the arctic is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the planet, resulting in the opening of an area that was for so long rarely mapped, and almost always colored white with shades of picturesque light blue to suggest its iciness.

The lands newly revealed in the northern climes have however led territorial claims of sovereignty to be staked by a four-color scheme of mapping. The uncovering of arctic lands–in addition to new technologies for underwater oil extraction and sensing–have complicated the existing maps of ocean waters premised upon expanding existing territorial waters an additional 278 kilometers beyond what can be proven to be an extension of a landmasses’ continental shelf–expanding since 1984 the rights to Arctic waters of the United States, Denmark, and Canada, according to consent to the United Nation’s Law of the Sea Convention (UNICLOS) which sought to stabilize on scientific grounds competing claims to arctic sovereignty.

The issues have grown in complex ways as the melting of Arctic ice has so dramatically expanded in recent years, exposing new lands to territorial claims that can be newly staked on a map that unfortunately seems more and more to resemble the surface of a board games. Even more than revealing areas that were historically not clearly mapped for centuries, the melting of the polar cap’s ice in the early twenty-first century has precipitated access to the untapped oil and gas reserves—one eight of global supplies—and the attendant promise of economic gains. Due to the extreme rapidity with which polar temperatures have recently risen in particular, the promises of economic extraction have given new urgency to mapping the poles and the ownership of what holes will be drilled there for oil exploration: instead of being open to definition by the allegedly benevolent forces of the free market, the carving up of the arctic territories and disputes over who “owns” the North Pole are the nature follow-through of a calculus of national interests. The recent opening up of new possibilities of cross-arctic trade that didn’t involve harnessed Alaskan Huskies drawing dog sleds. But the decline in the ice-cover of the arctic, as it was measured several years ago, already by 2011 had opened trade routes like the Northwest Passage that were long figures of explorers’ spatial imaginaries, but are all of a sudden being redrawn on maps that raise prospects of new commercial routes. New regions assume names long considered but the figments of the overly active imaginations of early modern European arctic explorers and navigators in search of the discovery of sea routes to reach the Far East.

On the one hand, these maps are the end-product of the merchant-marine wish-fulfillment of the eighteenth-century wishful mapping of the French Admiral Bartholomew de Fonte, whose maps promised that he had personally discovered several possible courses of overcoming a trade-deficit caused by British domination of the Atlantic waters, allowing easy access to the South Seas. The imagination of such routes proliferated in a set of hopeful geographies of trade which weren’t there in the late eighteenth century, of which de Fonte’s General Map of the Discoveries is an elegant mixture of fact and fiction, and imagined polar nautical expeditions of a fairly creative sort, presenting illusory open pathways as new discoveries to an audience easily persuaded by mapping pathways ocean travel, even if impassable, and eager to expand opportunities for trade by staking early areas of nautical sovereignty to promise the potential navigational itineraries from Hudson Bay or across the Tartarian nation of the polar pygmies:

Open-ended geographies of land-masses were given greater credibility by the dotted lines of nautical itineraries from a West Sea above California to Kamchatka, a peninsula now best-known to practiced players of the board-game RISK:

As well as imagine the increase potential shipping routes that can speed existing pathways of globalization, in fact, the meteorological phenomenon of global warming has also brought a global swarming to annex parts of the pole in confrontational strategies reminiscent of the Cold War that tear a page out of the maps, which give a similar prominence to Kamchatka, of the board game ‘RISK!’ Will their growth lead to the naming of regions that we might be tempted to codify in a similarly creatively improvised manner–even though the polar cap was not itself ever included in the imaginative maps made for successive iterations of the popular game of global domination made for generations of American boys–and indeed provided a basis for a subconscious naturalization of the Cold War–even while rooting it in the age of discoveries and large, long antiquated sailing ships, for the benefit of boys.

RISK (1968)

Following versions took a less clearly vectorized approach, imagining a new constellation of states, but also, for the first time, including animals, and updating those schooners to one sleeker ship!

Risk!, undated

The more updated current gameboard is curiously more attentive to the globe’s shorelines, as if foregrounding their new sense of threatened in-between areas, on some subconscious areas, that are increasingly prone to flooding, and less inviolable, but also suggesting an increasingly sectorized world of geopolitics, less rooted in individual. nation-states..

Risk–current board

Will future editions expand to include the poles as well, before they melt in entirety, as the ways that they become contested among countries percolate in the popular imagination?

We must await to see what future shorelines codified in the special ‘Global Warming Edition’ of RISK–in addition to those many already in existence in the gaming marketplace.

If the game boards suggest Christmas activities of time past, the ongoing present-day game of polar domination seems to be leading to an interesting combination of piece-moving and remapping with less coordinated actions on the parts of its players. We saw it first with Russia’s sending the Mir up to the North, which precipitated how Norway claimed territoriality of a sizable chunk of Arctic waters around the island of Svalbard; then Denmark on December 15 restocked its own claims, no doubt with a bit of jealousy for Norwegian and Swedish oil drilling, to controlling some 900,000 square kilometers of arctic ocean north of Greenland, arguing that they in fact belong to its sovereign territories, and that geology reveals the roots of the so-called Lomonosov Ridge itself as an appendage of Greenland–itself a semi-autonomous region of Denmark, upping up the ante its claims to the pole.

While the Russians were happy to know that their flag was strategically but not so prominently placed deep, deep underwater in the seabed below the poles, the problem of defining the territorial waters of the fast-melting poles upped the ante for increasing cartographical creativity. Recognized limits of 200 nautical miles defines the territorial waters where economic claims can be made, but the melting of much of the Arctic Ocean lays outside the claims of Canada (although it, too, hopes to stake sovereignty to a considerable part of the polar continental shelf), by extending sovereign claims northward from current jurisdictional limits to divide the mineral wealth. Were the Lomosonov Ridge–which isn’t moving, and lies above Greenland–to become a new frontier of the Russian state, Russian territory would come to include the pole itself.

Bill Rankin/National Geographic

The actual lines of territorial division aside, the diversity of names of the single region indicate the competing claims of sovereignty that exist, as if a historical palimpsest, within an actual map of the polar region: from the Amundsen Basin lies beside the Makarov Basin, the Yermak Plateau beside the Lena Trough and Barents Plain, suggesting the multiple claims of naming and possession as one approached the North Pole, without even mentioning Franz Josef Land.

While the free market isn’t able to create an exactly equanimous or impartial division of land-claims, the new levels of Denmark’s irrational exuberance over mineral wealth led the country to advance new claims for owning the north pole, and oil-rich Norway eager to assert its rights to at least a sixth of the polar cap, given its continued hold on the definition of the northern lands. The increasing claims on proprietary rights of polar ownership among nations has lead international bodies such as the United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Seas (UNICLOS) to hope to codify the area peaceably by shared legal accords–presumably before the ice-cover all melts.

The maps of speculation of the “Arctic Land Grab” is economically driven and suggests an extension of offshore speculation for oil and gas that has long roots, but which never imagined that these claims would be able to be so readily concretized in terms of a territorial map as the melting of the ice cap now suggests. But as technical maps of prospecting are converted into maps with explicit territorial claims, planned or lain lines of pipe are erased, and the regions newly incorporated as sites of territoriality in ways that earlier cartographers would never have ventured.

The existence of laid or planned pipeline by which to pump and stream oil across much of Upper Canada from the Chukchi Sea, North Slope, and MacKenzie Delta have long been planned by Canadians. Similarly, the Russian government, echoing earlier claims of Russian stars to straddle the European and Asian continents, have claimed the underwater Lomosonov Ridge as part of the country’s continental shelf, even if it lies outside the offshore Exclusive Economic Zone, as is permitted by UNICLOS–so long as the edge of the shelf is defined.

Canada has taken the liberty to remap its own territory this April, in ways that seem to up the ante in claims to arctic sovereignty. In updating the existing map of 2006 to make it appear more ice exists in the Arctic than it had in the past, the Atlas of Canada Reference Map seems to augment its own sovereign claims to a region in ways clothed in objectivity: even as arctic ice-cover undeniably rapidly melts in a decades-long trend, the ice-cover in the region is greatly expanded in this map, in comparison to that of 2006, and the northern parts of Canada are given a polemic prominence in subtle ways by the use of a Lambert conformal conic projection and a greatly expanded use of aboriginal toponymy to identify lands that even belong to different sovereignty–as Greenland, here Kalaalit Nunaat–in terms that link them to indigenous Canadians, and by extension to the nation. Both tools of mapping appear to naturalize Canadian claims to the Arctic in a not so subtle fashion. Moreover, the map stakes out exclusive economic zones around Arctic regions: even as the Arctic rapidly melts, for example, disputed islands near Greenland, like Hans Island, are shown clearly as lying in Canadian waters.

Perhaps what exists on paper trumps reality, creating an authoritative image of an expanded Arctic–a white plume that expands the amount of Arctic ice beyond the rendering of the Arctic Sea in its earlier if now outdated predecessor.

It is instructive to look backwards, to grasp the earlier strategic sense invested in the Kamchatka Sea, before it migrated into Risk! The earlier pre-fifty-states rendering of this Russian area as an independent sea, fed by the Kamchatka River, was seen as an area apart from the Pacific, bound by the archipelagos of a future Alaska that were imagined to bound the region, as if to create an oceanic theater of entirely Russian dominance, above the “eastern ocean” of the Pacific, and almost entirely ringed by what must have seemed to have been essentially Russian lands.

The above map has, of course, nary a reference to a pole, but an expanded sea remaining fully open to navigation with charts.

What exists on paper, once officially sanctioned, seems to stand as if it will continue to trump the rapidly shrinking extent of arctic ice. The map trumps reality by blinding the viewer, ostrich-like fashion, or keeping their head deeply buried in the proverbial sand. The decision to show the thirty-year median of sea-ice extent in September in the years between 1981 to 2010 brings the map into line with the way that Environment Canada computes sea-ice extent. And the augmentation of Inuit toponymy for regions near the Arctic recognizes the indigenous role in shaping Canada’s toponym. But it would be hard to say that either would be advanced if they did not have the effect of expanding Canadian sovereignty to the arctic. The reality it maps clearly mirrors the shifting interests of the state at a time of the shrinking of Arctic ice due to climate change, more closely than it shows the effects of global warming on the ice-cover of the northern regions, let alone in the Arctic itself. With more maps that diminish the effects of global warming, the orienting functions of the map seem to be called into question in themselves.

Merry Christmas indeed!