We now map mega-regions that extend along highways far beyond the former boundaries of cities, along roads and through suburbs increasingly lack clear bounds. The extent of such cities seem oddly appropriate for forms of mapping that seem to lack respect for physical markers of bounds. These maps reflect the experience of their environments as networks more than sites, to be sure. It may be surprising to see the mapping of the ancient world as a similar network, and to try to understand the mobility of the ancient world and Mediterranean in terms of modern tools of mapping travel–that would put NATO to shame, demanded to be studied as mobility research.

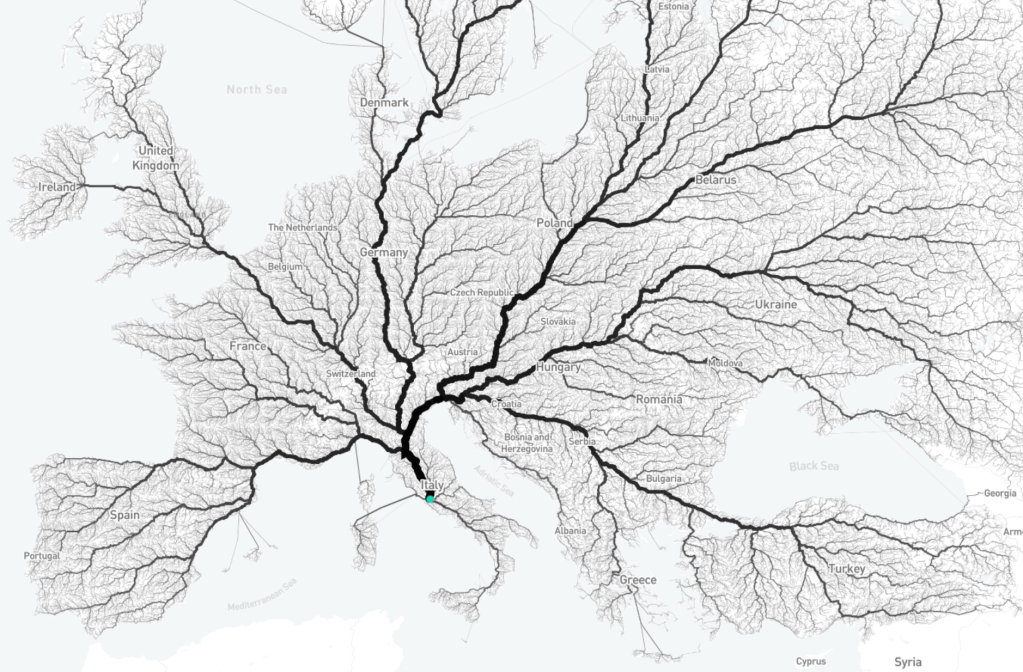

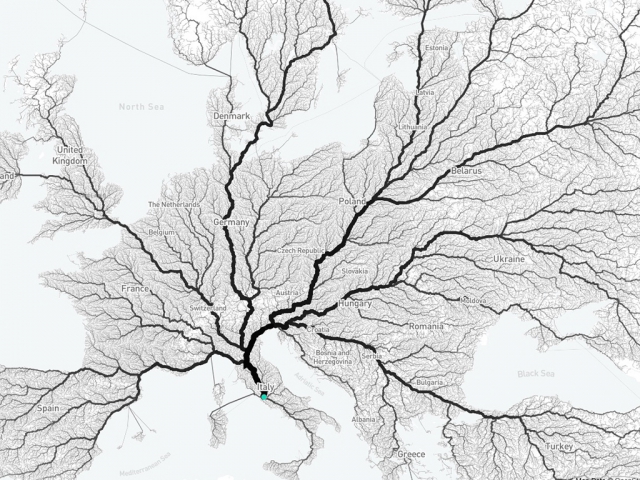

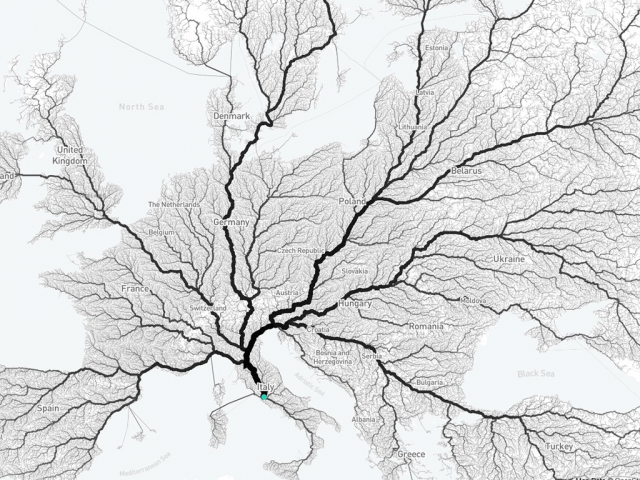

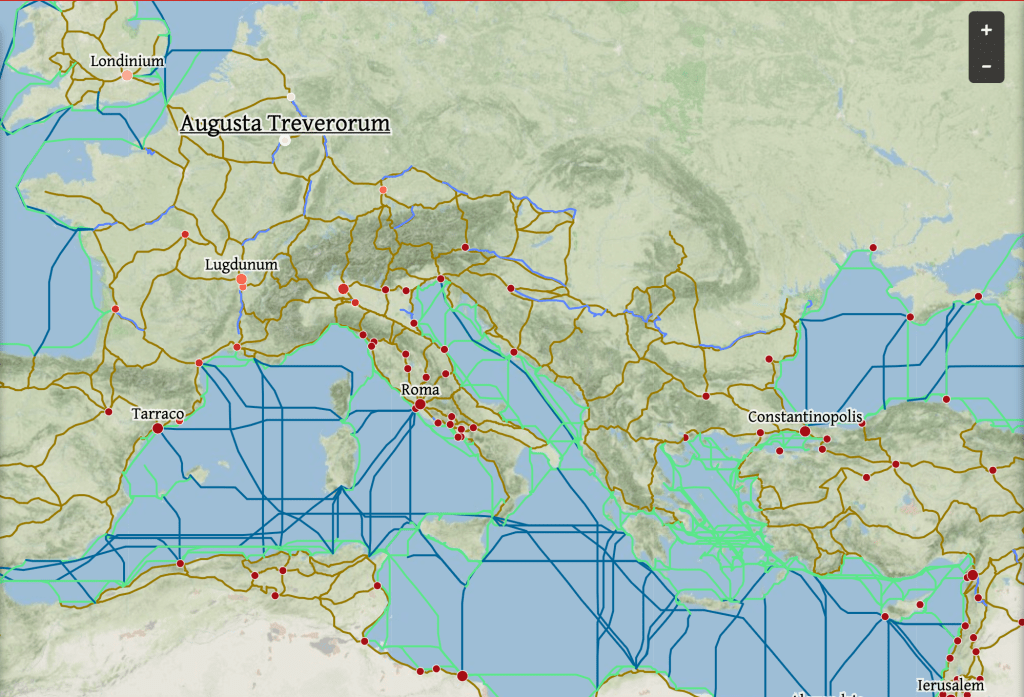

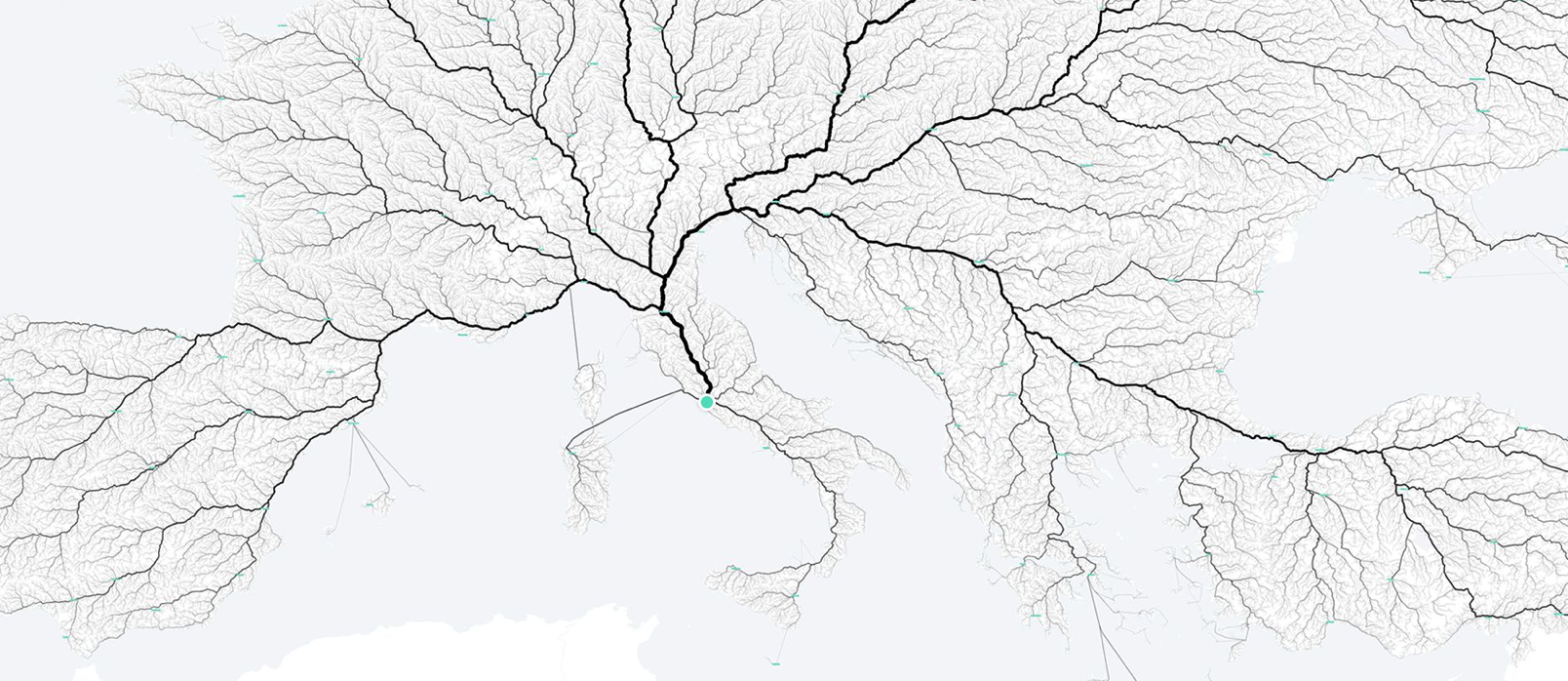

Roads to Roads to Rome,” by Moovel Lab

–that now provides a way to imagine travel in the pedagogic aids, as well as visual candy, by which we imagine the coextensive nature of an ancient past, mapping travel times, interconnectedness, and flow in the Roman Mediterranean, as if it were a smoothly interconnected network of transit enabling civilization, as varied digital humanities sites from Stanford to Europe assure us.

To privileged flow echoes the absent edges we have lost in our global mapping, tied to globalization, as William Rankin and others argue, more tightly that we are still unaware. Using algorithms to render overland flows of mobility that converged on the city of Rome in the ancient world may mix more metaphors and tools to digitize the past in distorting ways. These are uncanny resemblances to the maps in which we live, as much as told of the past, if they are used in heuristic ways: tracing the spatial extension of extra-urban areas along distended networks of paved space suggests not only a conquest of the antique, but its transcendence, mapping ties within as well as to an ancient world. The analogical nature that Freud gave the expertise of archeology staked out the claims he made for a new science firmly planted in objectivity of a personal past, by a powerful conflation of the personal past with the objectivity of sedimented layers of time.

If Freud understood the self as able to be revealed as a sort of substrate created by interactions of instincts and society, of which the psyche was the result, archeology provided a metaphor, but also a model for excavation and for storytelling to understood psyche as an objective map. And if we are coming to acknowledge not only that archeology was a guiding metaphor for Friedrich Nietzsche that Freud adopted and embraced in his explorations of the psychic traces of personal pasts, in concrete terms that were more rooted to the tie between seeing and saying in their works–and in the therapeutic cure–that explored a terrain hardly able to be seen as transcendent, so much as excavating deep labyrinths in the psyche. For Nietzsche’s use of archeology as a metaphor of knowledge was more rooted in the visual and the concrete helped Freud focus on the “trace” as part of an artifact through the maps he had encountered of the physical situation of a past in Rome, in ways that he was able to transpose so creatively to the physical sites of the psyche not only in the human brain, but in the textures of memory that were, for Freud, quite compellingly concrete.

For Freud’s maps of memory are hardly transcendent, but relied on archeological maps that recuperate the detail of the local, and are hardly able to transcend the suffering or traumatic, or imagine space in algorithmic contours but ones deeply specific and self-made: whose contours and specific way stations are able to be narrativized in telling, and are explored as they are retold with attention to their imagery, psychic and remembered, and unable to transcend individual experience They play with the immediacy of the remote, and the delivery of a past into a tactile present, that was mediated by archeological maps, however, and a sense of the accessibility of a lost past, or past thought lost, that the fantasy of archeology allowed, an ability to shift between temporal registers at the same with a dexterity that the analyst claimed his won special sleight of hand if not intellectual property, rooted in the specific and concrete detail in the psychic past but able to be narrativized as objective discovery in the privileged studio from the layers of narrative and words of the analysand.

1. If the metaphor of the historical map paralleled with uncanny temporal precision in twenty-seven sheets of the Palestine Exploration Fund’s gambit to illustrate the Old Testament as collective history, the map of Rome became the most famous typos for excavating a personal, rather than the maps of Old Testament History that even presumed to detail the prophetic divisions of Ezekiel. Freud had higher aspirations, far more removed from religious divination or airs of prophecy. He eagerly affirmed the task that faced “great discoveries are made by the great discoverers” on New Years Day 1886, as he pondered questions of nerve pathologies that might be allowed by indulging in cocaine, as doors of consciousness, that affirms the scale of his desire for still deeper discoveries. He late rued it as his “fate to discover only the obvious: that children have sexual feelings, which every nursemaid knows; and that night dreams are just as much wish fulfillment as day dreams,” he had claimed his “discovery” of the infant attachment to its mother in 1931 as fundamentally important to world-view that it paralleled “the [recent] discovery of [the 4,000 year old] Minoan-Mycenaean civilization behind that of Greece,” by Sir Arthur Evans had heralded, readily coopting the interest in recovering “vestiges” of psychic attachment and trauma in the human mind in archeological terms. While the milky grey matter resists a road map of intertwined nerves, veins and arteries that nest in musculature around bones.

Freud claimed to have been prevented from his own profession aspirations to be a surgeon as “anti-semitism had closed those ranks . . . to the point where they kept the Jews out.” But the deep concerns he voiced about forsaking his professional vision for himself were in part met by the identity of an archeologist, a compelling figure and metaphor for individuating traumatic memory and healing: he represented himself in the trenches of archeology, as a sort of purified version of his excavation of emotions, rather than raking through the psychosexual muck. If Freud has been cast as a crypto-biologist, a modernist, a fabulist, a detective, the inventor of the dynamics of psychology, and as a hopeless positivist, the figure of the archeologist, one might suggest, capacious to hold all these roles and historicize them in ways that suggest a distinctly specific unity,–especially if we remember the modernity of archeology as a science. For Freud was ready to see symptoms as able to be excavated as psychological strata through the process of analysis.

While this might be traced to the excavation of primal emotions in the fifth century BC archeological statues of Pheidias, revealed in the terror in the bulging eyes, flaring nostrils and gaping jaw of a single horse of a chariot drawing the Goddess of Night in the Parthenon–

Pheidias, Head of Horse from Pediment of Parthenon Sculptures/British Museum

–what Freud called the dream-work opened overlapping memories in the mind that he rendered as the physical plant of a city, a living object that was wrongly seen and regarded as dead. The chariot that carried one of the Moon Goddesses of the Night across the evening sky–Selene, sister of Helios and Zeus, most likely–echoes the intense cathartic shock of the excavation of emotional encounters Freud claims that the surface of dreams allowed him to work with his patient to extract.

The figure of archeological discovery both purified and monumentalized his discoveries. They figure of the archeologists not only lent status to his new profession but the analogy exaggerated the objectivity of his discoveries and purified them in objective form. His discovery of the oedipus complex, dated to October, 1897, was described an alarmingly definite moment of realization, and later intimations of future discoveries filled his notebooks and diaries in ways that have assumed an epochal character of a new topographic landscape of a world submerged in the individual mind. Even as Freud moved from physiological interpretations to hermeneutic interpretations, figures of cartography and the archeologic status of maps were metaphors that dignified “discoveries” of infantile sexuality, Oedipus complex, or keys to dream-interpretation heralded to be of the same rank “as a genuine ancient discovery” (SE I: 263). These discoveries were, he increasingly came to believe, a “royal road to the unconscious,” in a figural construct modeled on networks of Roman roads built for to facilitate the transit and transportation, a figural basis for future discoveries?

Freud rewrote the language of discovery–and scientific discovery–from positive perceptions by locating insight in recovery of the “memory trace” by remapping the human psyche as tangible landmarks recovered from lost sedimentary strata with considerable flair. Did not the recent inscribing the name of the father of psychoanalyst on a neoclassical facade of an abandoned church in Oxford, England not exploit the conceit of an ancient temple as a doorway for the initiated?

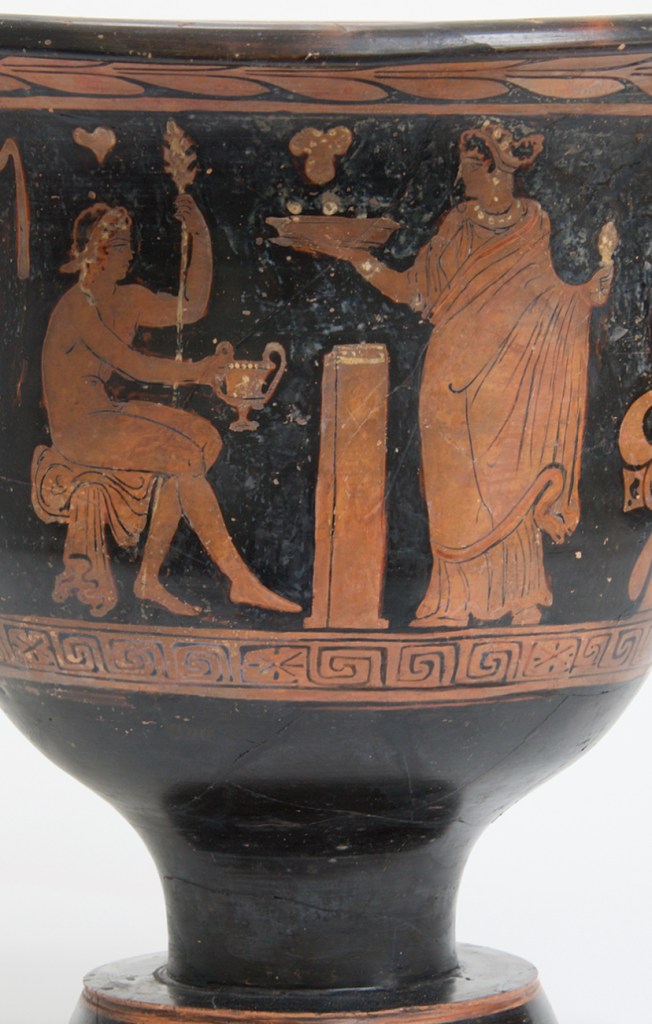

Freud’s passion for the totemic role of archeological antiquities as aestheticized objects was perhaps not the sold reason his aristocratic student Marie Bonaparte gifted him a red-figure vase of the ancient God Dionysius that had been recently excavated from grounds in the south of Italy. The valuable urn was long displayed in his office, winning a privileged place among the two thousand of antiquities in his own personal , echoed the deep analogical role of archeological excavation in Freud’s thought, confirmed to some extent by how Bonaparte’s telling gifting of the urn came to be selected as the final resting place for his ashes in Guilder’s Green–a sort of pilgrimage site holding the ashes of Freud and his wife, the former Martha Bernays; the vessel where the family placed his cremated ashes would have situated his place in a clear intellectual pedigree of excavating lost pasts intertwined with a sexual psyche, but seemed a sort of assumption of identity as a pilgrimage site from 1939, removed from Jewish funerary rites or custom, in the ancient context of the offering to a god. Freud was long respectful of “Princess Marie”–as he called her, assuring his grandson she would be his own “first patron” of art, and gifting her the first sculptures Lucien Freud made in art school, the exchange of objects was heavily charged. The archeological analogies of antiquities consolidated his own cultural status in a self-made field he sought to invent.

The image of an enthroned Dionysus, god of regeneration, fertility, ecstatic transport, and insanity, relaxing with a caduceus like staff, wreathed with laurels, was entertaining a maenad, a fanatical female follower, in a slightly perverse token of the reverence Bonaparte felt for her teacher, lay among the Egyptian and Roman funeral urns that he had collected with a passion, and while no funeral mask was made of the psychoanalyst who cheek had physically degenerated, that image of regeneration seemed apt.

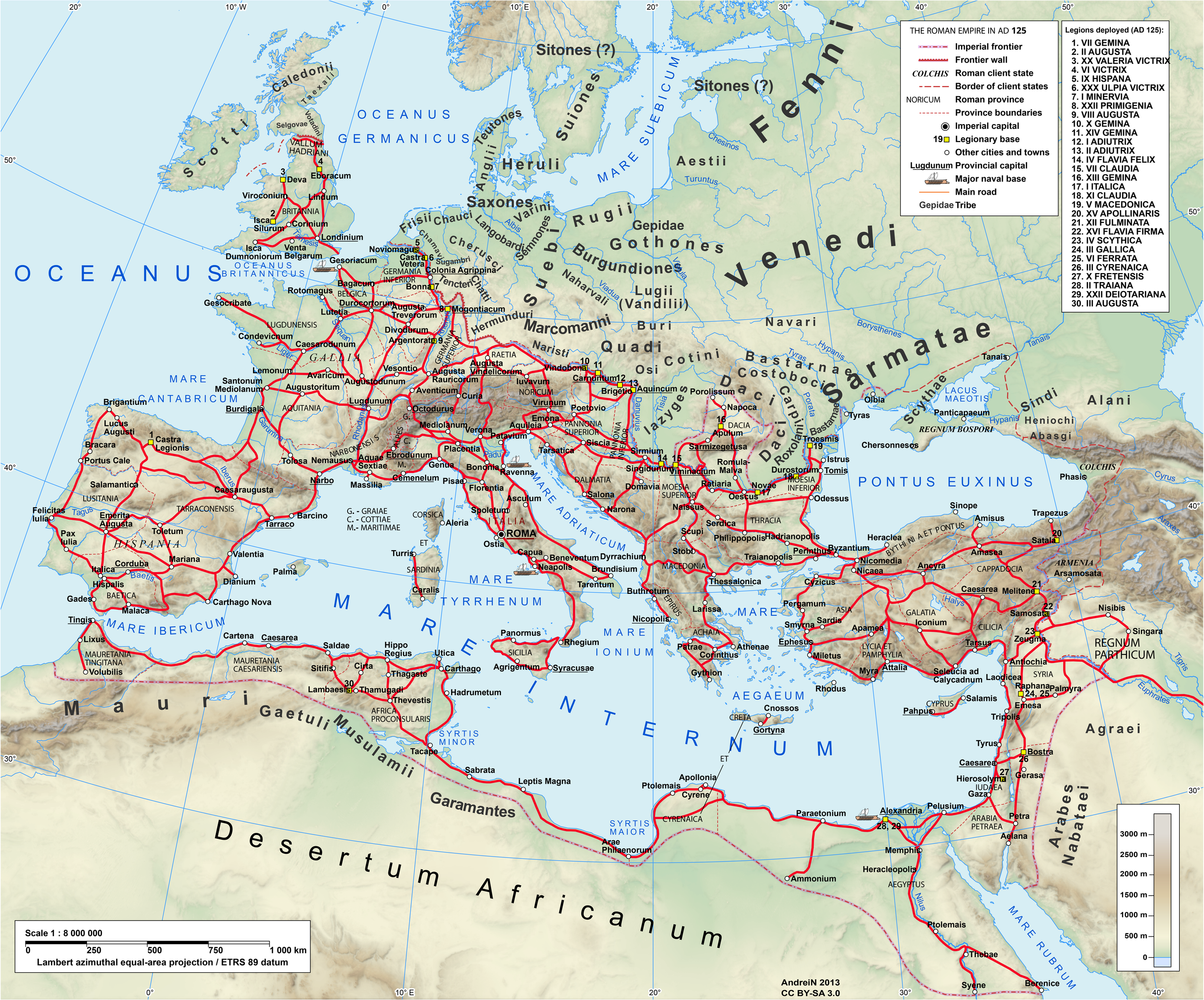

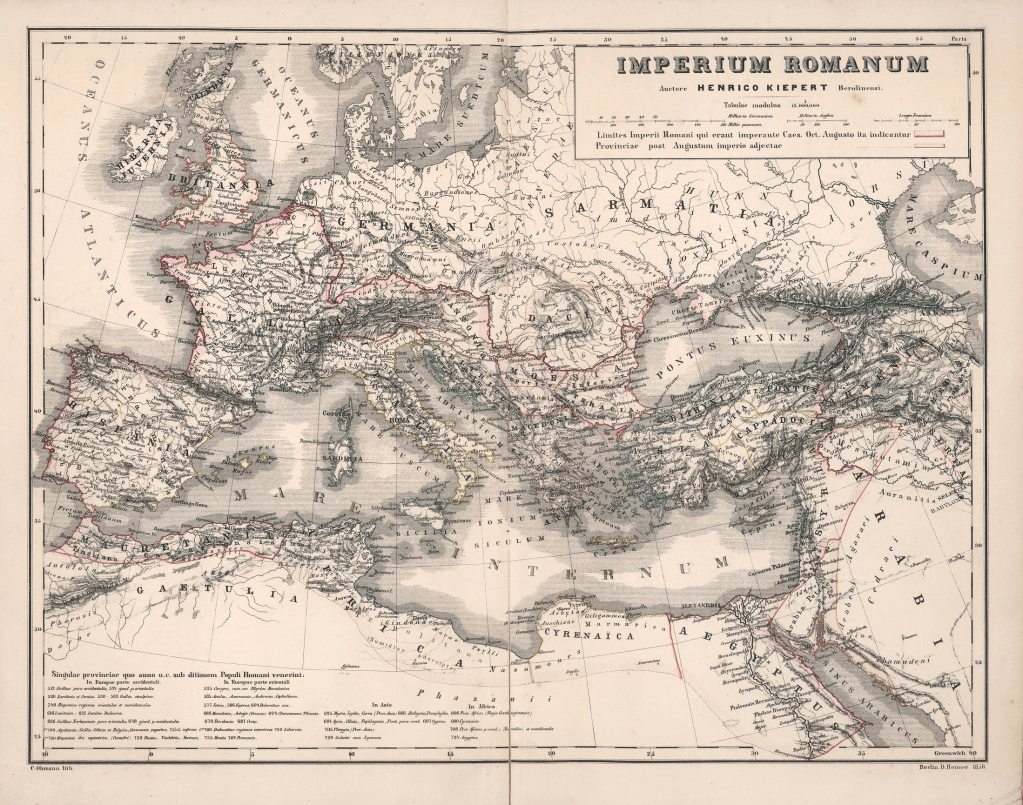

But they offered a far more pervasive basis to map the psychical world in ways that a surgeon might never be able to attain by their simpler instruments and tools. For they cast claims of pschyoanalytic insight as finds by far more than an analogy, as many note; the power of the map of an excavation is less appreciated as a claim for objectivity at the culmination of an Enlightenment inquiry, however, joining materia medica with art in a sleight of hand. The “royal road” to the unconscious Freud claimed to offer was a rhetorical reconstruction o the psychic formation of the subject not nearly as tangible as a cultural tour of Italy in a Grand Tour of historical monuments, but situated in the cultural aesthetic formation that linked archeological expertise to the individual mind, and resonated with the archeological maps of the Roman ruins of ancient cities quickly adopted as forms of building on Viennese and Central Europeans walls as descriptions that were iconic signs of their intellectual pedigree as mirrors of their own cultural stature and prestige. The analogical argument located heightened intellectual transport of the uncovering psychical layers as a fixed topographic terrain of archeological finds,—akin to how Poole’s famous Historical Atlas of the Roman Empire. Archeology, as much as neurology, offered convincing criteria for Freud to pronounce the terrain of his discovery, beyond any interest in therapeutic judgement.

Reginald Stuart Poole, Romanum Imperium (1896-1902)

To affirm his discoveries Freud wanted–or needed–such a detailed analogical map. Only it was able to offer a sufficiently powerful rhetorical figure of sorts able to announce and lend status to truly major discoveries, and he was, by extension, a great man. As the ancient world was mapped in the late nineteenth century of the archeologist, numismatist and orientalist Reginald Stuart Poole’s tracing of the boundaries of the Roman Empire and other antiquarians raised hopes of rendering the discovery of a submerged roadways materially present across Europe, the recovery of the pasts present in the individual mind was similarly explained by the superimposed fabrics of past selves–akin to the Palestine Exploration Fund’s own public relations campaign by detailed maps.

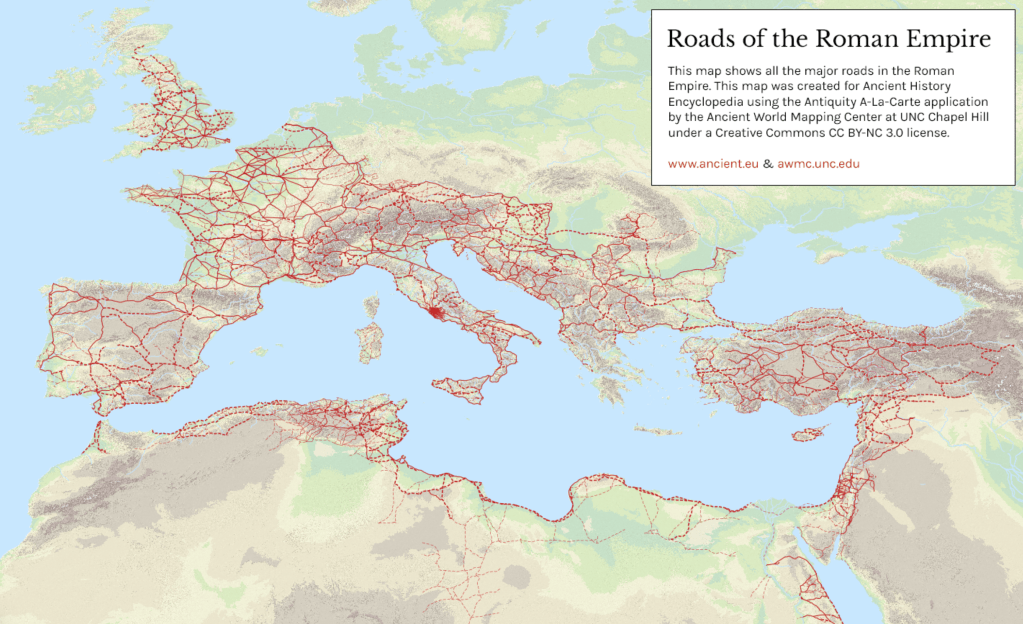

2. Was not the fiction of a historical atlas a powerful way to recast the materiality of past experience in familiar scientific terms? The hopes for remapping the underground network of identity was present in the extent of ancient stone aqueducts, eleven of which fed Rome and a network feeding the Bay of Naples, that brought water to cities’ public baths, and the public roads of the empire on which messengers, couriers, and soldiers traveled, the palimpsestic network of Roman roads that appeared both a civilization of space and empire. It was indeed an organic substrata of civilization, and the organization of urban space of Rome offered a concrete figures Sigmund Freud seized with eagerness as a rational basis basis to describe and monumentalize the material presence to the mind of an individual’s past. Freud’s adoption of such powerful figures of speech for his own discoveries benefitted from of a growing concrete relation to urban space perpetuated and broadly reproduced in maps, which themselves mediated a romantic fantasy of securing immediate access to past spaces and to the unity of space, that became central to the construction of a unity of psychic space, if not the uncovering of the engineering and indeed economy of the psyche–and a very physical metaphor of the discovery and “unearthing” of its map.

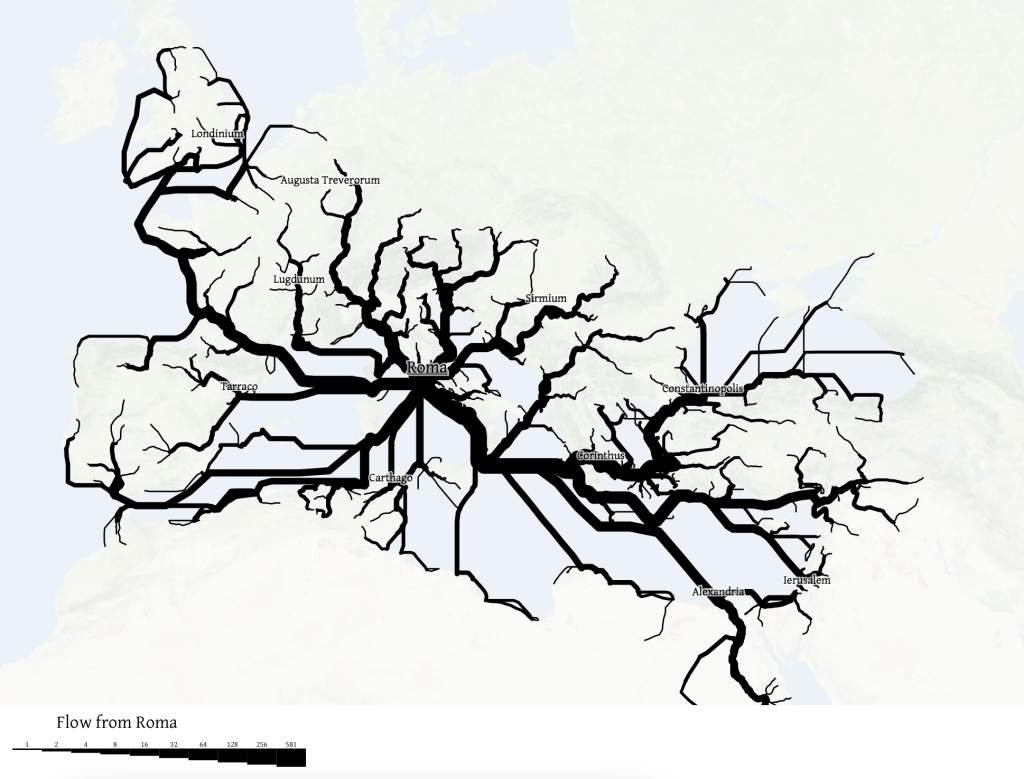

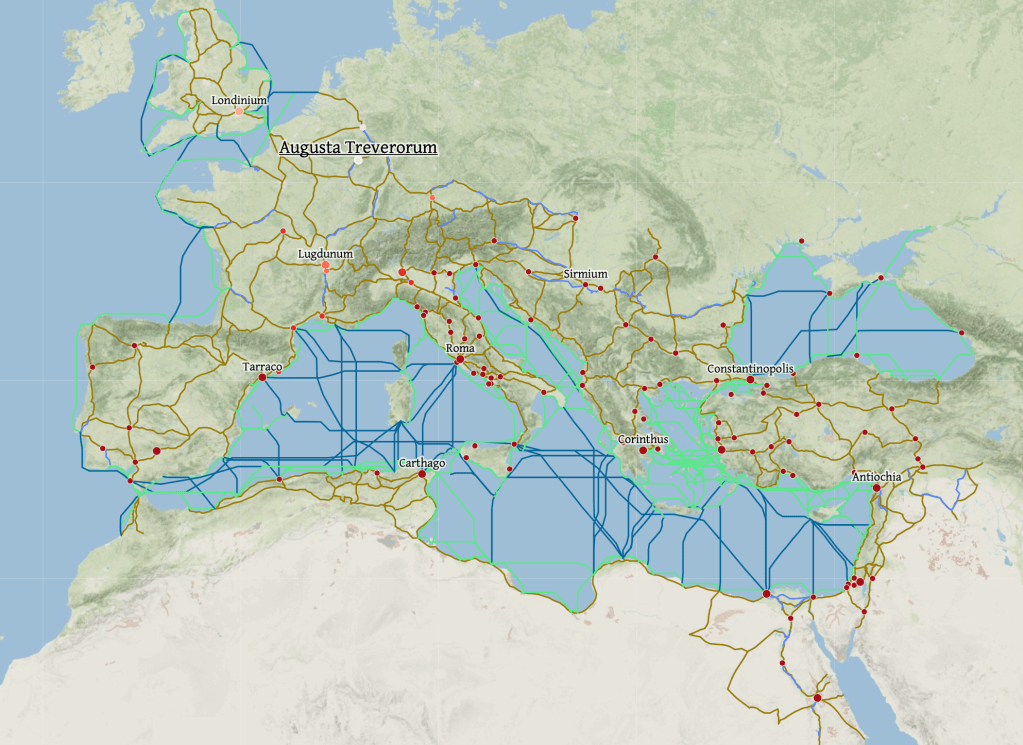

If the totality of Roman roads were mapped from the nineteenth century to the growth of online encyclopedia circa 2000 to concretize ancient history, the role of maps to concretize a relation to the past has since grown exponentially. The network has a new iteration from Stanford’s ORBIS in a brilliant interactive form of mapping Roman roadways–a “GPS for the Roman Empire,” with costs of transport and time of travel included, as an ancient UPS system or FedEx key–to represent important arguments of the spatialities of the ancient world. But the mania of mapping the ancient networking of the Roman Empire as a unity. The maps prompted me to do a deep dive in the materialities of “Rome” that maps have conveyed, hoping to excavate subjective relations to early maps of Rome and perhaps in the virtual interactive web-maps’ geospatial emphasis.

If the demand for mapping the Mediterranean expanse of the Roman Empire is perhaps motivated by deep interests in placing Rome within a global history–a global scope all too evident in the very name of ORBIS and its website–the mapping project offers the different perspective on the ancient world contrast to the competing layers that were long understood as essential in Rome itself.

The current geospatial turn has emphasized the map as a network to plan travel, by seasons, modes of mobility, and route, as if on a modern travel network, projecting flows, nodes, and network, in a conceptualized in unique if not much more graphically embodied than earlier GIS overlays, if offering a dazzling array of ancient options of of mobility on hand–ship, horse, foot, river–and breadth of spatial expanse as a rich board game of open source data from ancient times as much as an invitation to “explore” the ancient world, as Elijah Meeks and Walter Scheidel exhort users.

ORBIS, The Stanford Geospatial Network of the Ancient World, W. Scheidel and E. Meeks

The warping of time evident in recent web maps of the ancient world does a neat double-trick, both s them from historical time and erasing the complex techniques of reconstructing past space. But the relation to travel networks is predominantly flat, as if spatiality exists in an easy translation or iterability of online resources, using the Google template–or other online networks–as a matrix for antiquity.

Rather than the painstaking assembly of a familiar palimpsestic relation to known space, the ancient roads of Roman Empire are converted to a known space, akin to a known world, whose routes open up to us as if a space for walking. There is a disturbing loss of all complexity of processing time and space, in these graphic analogues of the medieval precept, “All roads lead to Rome,” literally ‘”mille viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam [a thousand roads lead men forever to Rome]” as Alain of Lille had it in 1175, in his Liber Parabolarum, have long merited data visualization, so present are they in the collective European unconsciousness. (That they would flow through Denmark, Hamlet’s home, Estonia, and Ukraine, seems perhaps a fitting sort of surprise.)

In tracing the ties of the self through the unconscious, Freud was very clear in an early work: given the incomplete nature of clear records of the unconscious or the past, he worked as a “conscientious archeologist,” not omitting any authentic fragments, and noting the gaps between reconstructions and the “priceless though mutilated relics of antiquity” which it has been the “good fortune” of the archeologist to be a bee to “bring to the light of day after their long burial.” The tie is obvious one, in part, but a deeply poetic act, as well. Freud’s reference to the science of archeology–often seen as a means of legitimization of psychoanalysis as a discursive project of investigation, apart from purely poetic framing, elevating the level of science of neurology to the epistemic plateaux of archeology to manufacture or support its claims to rigorous certainty.

3. In the years when Freud was fresh from the coining of the term “psycho-analysis” in 1896 in Vienna, a plumbing of the mind, seeking prestige for the term and the therapeutic practice mirrored Freud’s interest in collecting antiquities. He was both drawn perhaps to the assembly of fragments as central forms of reconstructing knowledge, defining both the status and ethical quandaries posed by his claims to be mapping the human mind. The etiological hope to “elucidate,” “reawaken,” or “reveal” personal histories about which patients had “no inkling of the the causal connection between [submerged memories] and the pathological phenomenon” was to be “exposed . . . in a most precise and convincing manner,” as Freud and Breuer wrote triumphantly in 1895, as if convinced they uncovered the “pathogenesis of hysteria as a source of psychic traumas, even as they promised to “refrain from publishing those observations which savored strongly of sex.” To chart repression of past sexual encounters, they aspired to a far more sanitized plane of writing, of which archeological plans provided a model if not a fons et origo. If hypnosis provided the basis for recreating hysterical phenomena, in all their associative relations, Freud’s turn from hypnosis as a revelation of a trauma or repression demanded a new syntax of tools of unveiling and revelation.

For late nineteenth-century archeology was, for many, Freud included, first and foremost a form of mapping, mutilated and buried if the “relics” of antiquity were, and the analogy of mapping as a form of bringing to knowledge, and indeed sharing among readers, as much as the creation of a given dramatic scene or “primal” scene that was repressed, and that the patient might be liberated from in its detailed reconstruction. The freighted sense of psychoanalysis as a new form of mapping, and indeed as a form of cartographic knowledge, indeed jostled with the poetic nature of interpretation in Freud’s works, and deserves to be uncovered and excavated in full.

The learning of Rome, and of archeology, suggested a model both as tied to art and as objective in its referents, but dignified a field of interpretive action of digging for memories, removing them from the muck of their associations or even of the human action of embodied life. But the scalpel-like precision of the archeologist assembling and reassembling fragments to piece together a compelling narrative of a past mystery–as much as plumbing the messiness of sexual memories. The emphasis of Carlo Ginzburg on the reading of clues in the dream-interpretation is perhaps a “paradigm” of study, but was dependent on the visual nature of evidence that allowed Freud to put dream-interpretation on secure footing, positing the individuation of key traumatic memories in dreams or psychic visions as a condensation of meaning in one moment of personal history. (The figure of the Gradiva to which Freud kept returning was an image of the Eleusian mysteries of rebirth: the secrete rites depicted by the dancing Maenads that the figure of Norbert Hannold saw, so crucial to the defining of psycho-analysis as a resolution of neurosis, is from a dancing group of Maenads engaged in the most secret of ancient religious ceremonies, but is taken for the striking figure of an individual woman: is the ancient mysteries, associated with an annual fertility rite and the return of Spring, to which only initiates and priests were allowed to see or participate, and ceremonies of initiation thought to have been accompanied by a psychoactive stimulant. The rites, often reproduced in reliefs, became a basis for Carl Gustav Jung to understand psychoanalytic treatment, long after Freud; as a reconciliation with death, the mysteries suggested a cartharsis Freud was increasingly understanding as a moment of psychic cleansing able to eliminate hysteria by its roots in one’s memory by calling it to conscious awareness. Was this present in the frieze?)

Yet the personal history that Freud sought to elevate by dream-interpretation was doing a lot of lifting, borrowed from the excavation of archaeological diagrams of a collective European past. The pervasive network of roads Roman endures as an overlay of imperial roads, present to most students in the nineteenth-century, whose elusive coherence as an “Orbis Romani” and “Imperium Romanum” was widely studied in cartographic form. From the time of their printing as teaching aids in post-Napoleonic Europe through the emergence of archeological sciences, included the 100,000 km of ancient public roads as the nervous system of its imperial unity, the image of a Europe that was continuous and defined–as much as a network of nations or a puzzle of territorial clusters–provided a new image of the peace at the end of the wars, and of a coherent culture.

Keipert, “Imperium Romanum” 1858, Edinburgh (Courtesy Donald Rumsey Library and Map Collection)

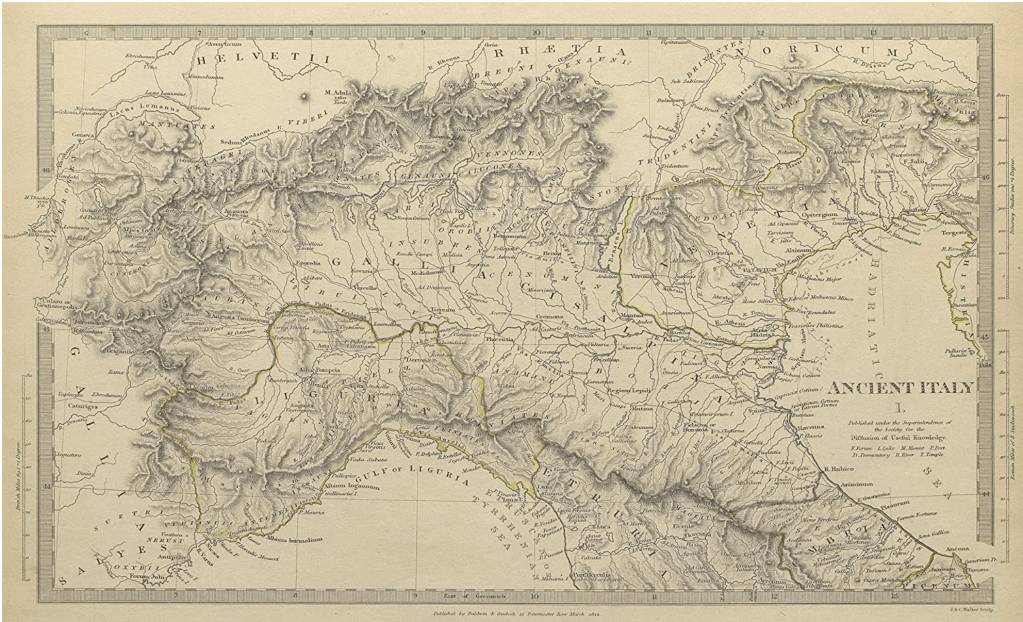

The diffusion from 1844 of a strikingly map of the roman public roads in “Ancient Italy” produced by The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge may have aided Emerson to treat the road network nothing less than a template of human knowledge, if not a common point of reference for learning, if not for reading works of ancient Roman history.

We may be compelled to apply the same data driven images to ancient Rome, driven due to our own continuing and increased disorientation on the proliferating data maps. But does their logic maintain the complexity of time, space, and place in the ancient world, or how might it better attract interest, by casting the map as a site of investigating not only space, but time? In Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “History,” delivered about 1836, Emerson felt compelled to locate the beginning of the history of man’s relation to nature in the “life is intertwined with whole chain of organic and inorganic being” from the totality of how Rome’s system of “public roads beginning at the Forum [that] proceeded north, south, east, west, to the center of every province of the empire, making each market-town of Persia, Spain and Britain pervious to the soldiers of the capital” as an image of the extension of the individual ties to the world by pathways extending from the human heart.

Ancient Italy, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1832, rep. 1844)

Emerson long preceded Freud, of course, but eerily echoed his points about human psyche when he waxed rather eloquently that as the organic looking map of roads of the Roman Empire, “man is a bundle of relations, a knot of roots, whose flower and fruitage is the world.” Emerson’s notion of the individual as a changed by engagement in nature, and hence always in flux, sharply contrasted to Freud’s famous sedimentary construction of the human psyche in terms borrowed from archeology, but both are searchingly constructed not only in cartographical terms, but in reference to tactile maps of Rome’s past.

The start of these roads–in the below visualization the light blue point anchoring a record of ancient Rome’s primary routes of travel–marked the Forum, the very site Edward Gibbon claims he conceived the scope and scale of his multi-volume Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776), and, if the point is taken as the city of Rome, where Freud attempted to reprise Emerson in more positivistic terms, in the famous figural description of the temporal layers of personal experience existing as so many archeological strata or laminated sheets of time in the human brain, telling readers they might understand the psyche if they “suppose Rome is not a place where people live, but a psychical entity with a similarly long and rich past,” before, out of frustration, abandoning the metaphor as a way to grasp the interaction of personal history in the mind, before admitting a spatial analogy not able to capture the historical landscape any psychical entity creates.

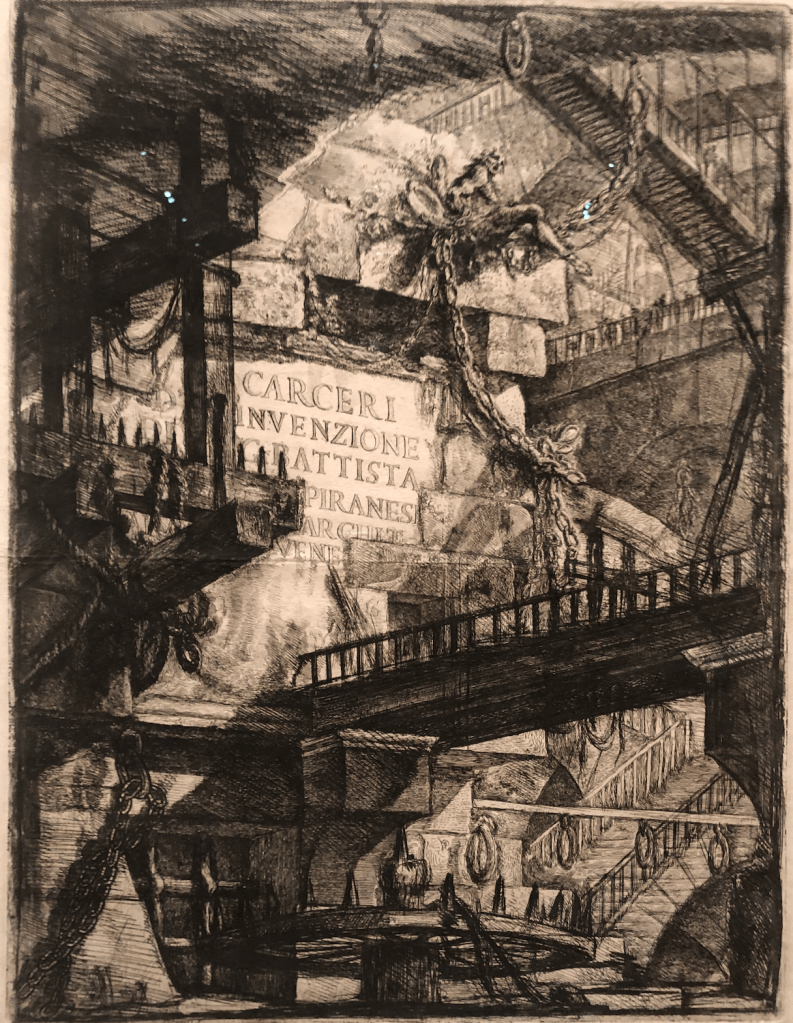

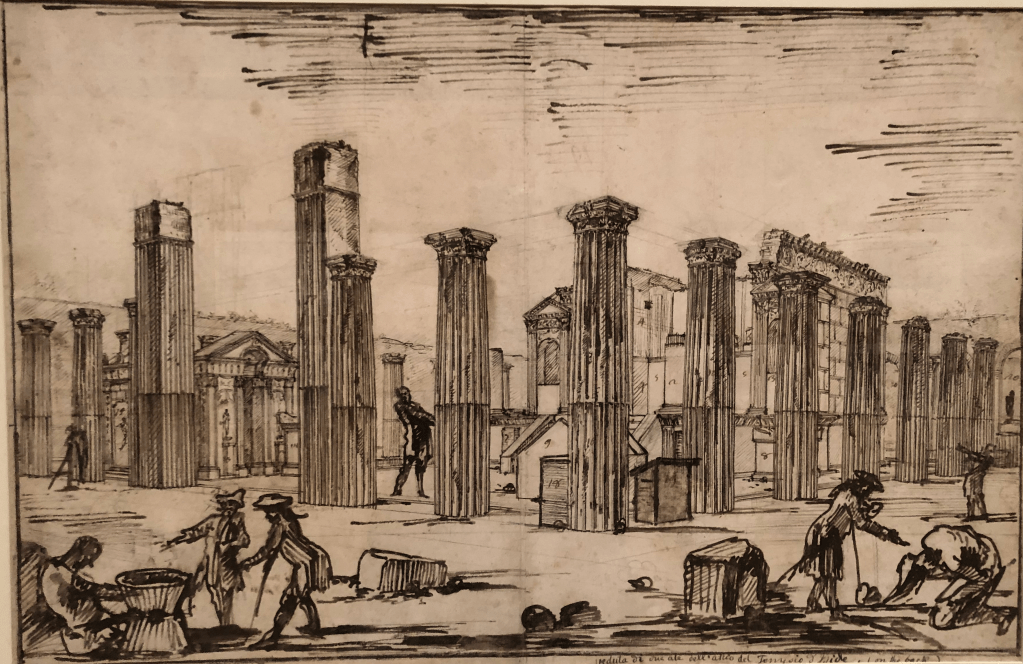

The imagination of Rome as a “universal past” may be deemed overly Eurocentric and dated today, but the cartographic origins of Freud’s hopes for promoting access to the multi-planar or multi-dimensional nature of psychic realities have been less grasped as a model not only of universality, but of the legibility that maps claim to provide, untangling a network not only of roads but allowing the eye to untangle historical periods, by a palpable relation of the past. The image of access to the past through its material structures was offered nowhere more than in the engravings of the architect artist who oversaw the excavation of Pompeii–Giovanni Battista Piranesi, architect and archeologist as well as accomplished draftsman. Piranesi was involved rooted in the esteem of archeological investigations, whose artistic cartography became a guide to the ruins of Rome’s classical world. Venetian-born, his virtuosity became Rome’s perpetual touristic visual guide, who had oriented Enlightenment Europe to its ruins, unveiling the hidden pasts eighteenth-century Enlightened tourists looked to orient themselves to Rome. If Piranesi began exploring the cavernous monumental ruins of Rome soon after he was –working to realize Clement VIII’s program of a new classicized monumental architecture of the Lateran church and other cathedrals–only to end his career designing imaginary prisons whose cavernous interiors invention had a darkness perhaps with other metaphorical parallels to Freud’s excavation of the unconscious.

But that is another story, less tied to the architecture of the ancient world, more to the monstrosity of modernity than the archeology of the past, or the pastness of the past. If Piranesi in the 1770s captured the astounding recovery of Pompeii’s Temple of Isis with an unimaginable materiality of a recovery of the past, akin to a time portal–the ruins of the Temple were European-wide phenomena of a physical, tactile recovery of Roman ruins seen mostly as fragments after their archeological discovery in t1760s–spaces to navigate and explore among erudite and learned voyagers, akin to the entrance into another world by an unimagined or unimaginable portal, whose drawing sought to capture the astounding contact with a lost past era–

–Piranesi would only later turn, as Freud turned to the prison of consciousness, to the terrifying recovery of the prison ruins of his later invention late in his career as a prolific draftsman of the uncanny the are able to be taken as illustrations of the psychosocial prisons of modernity.

Perhaps Piranesi’s actively broad reflection on the imagining and imaging of Rome’s pasts was born out of the attempt to map the network of travel from and to Rome. The success of mapping the distances of travel from Rome on Roman roads, that might have some power as an organic material manifestation not only of the past, but of the Emersonian idea for seeing the roads of Rome as a master metaphor for man’s relation to nature or to the natural world–but raises questions of the deep power not of Rome’s universality, but the power with which cartographic attention has so valiantly attempted to use its tools to untangle Rome’s pasts.

Moovel Labs, 2019

Despite the limitations of their coverage of space, and the limited benefits of imagining the ability to measure times of travel or distances to monuments as a record of ancient space or Roman life, it is tempting to be satisfied with placing it in a network. For to do so offers a way of envisioning ancient Rome as a mega-city and hub of transit. But the erasure that this brings in humanistic experience of the map is striking. If we now move to Rome on paved roadways with utter facility and ease, the sense of unpacking Rome’s significance in the European landscape–or its significance in time–seems washed away in the data map, as if the historical significance of what was once understood not only as a historical center, or center of cultural ties, but the focus of a network of paved roads that united the Roman Empire is all but erased, and is now only an example of the visualization of urban mobility, and of a time when all roads might lead to a privileged city–Rome. There is something suspicious utopic at foot, if also something visually entrancing.

The risk of a loss of materiality is steep: for we seem to lose a sense of the presence of the map of the city, visualizing the distances of travel, costs of economic transit, and time of travel in a web of commercial exchange we both project back our own sense of disorientation. When we use modern notions such as that of the urban mobility fingerprint as the folks at Moovel labs did in concretely visualizing the medieval saying that “all roads lead to Rome” in its project of mapping distances from the ancient city, we run the risk of insisting on the transparency of data, reducing maps and the pattern of mapping to a substrate of spatial relations sufficient in an almost ahistorical sense, and risk asserting the authority of an app over material processes of building and mapping Rome across time.

Continue reading