While we’ve been driving ourselves to distraction with the distortion of the electoral maps, projecting the failure of our system of government in the specter of “tied” electoral contests in which the vote is thrown to the House of Representatives, rather than anyone having a vote, we as if realizing the real fears of disenfranchisement that are all too palpable in the current status quo. The possibilities of choosing a President in a polarized nation have led, not only to consecutive weeks of polling so closely within the margin of error to be set many to rip out their hair, but also inevitably ratcheting up the fears of violence–and violent confrontation–at the polls.

As if a concrete version of swinging, the fears of fists swinging at the polls seemed all too real, perhaps in the memory of January 6 still fresh in some minds, and the major actors, decentralized and all-male actors seeming to respond to Trump’s rhetoric, claiming that they would “show up” at the polls, as Ohio-based groups posted “the task is simply too important to trust to regular normies,” legal norms, or boards of election. All ratcheted up fears that the election would be stolen, amplifying anxieties about the authority or legitimacy of the election. by taunts that “FREE MEN DO NOT OBEY PUBLIC SERVANTS” on alt right social messaging platforms before Election Day. The Proud Boys, famous for having been told by Donald Trump in past Presidential debates to “stand down and stand by,” now stood “locked, loaded, and ready for treasonous voter fraud.” The demonization of public servants and the civil service, only to be amplified by the Trump White House in later months, was indeed launched within the election.

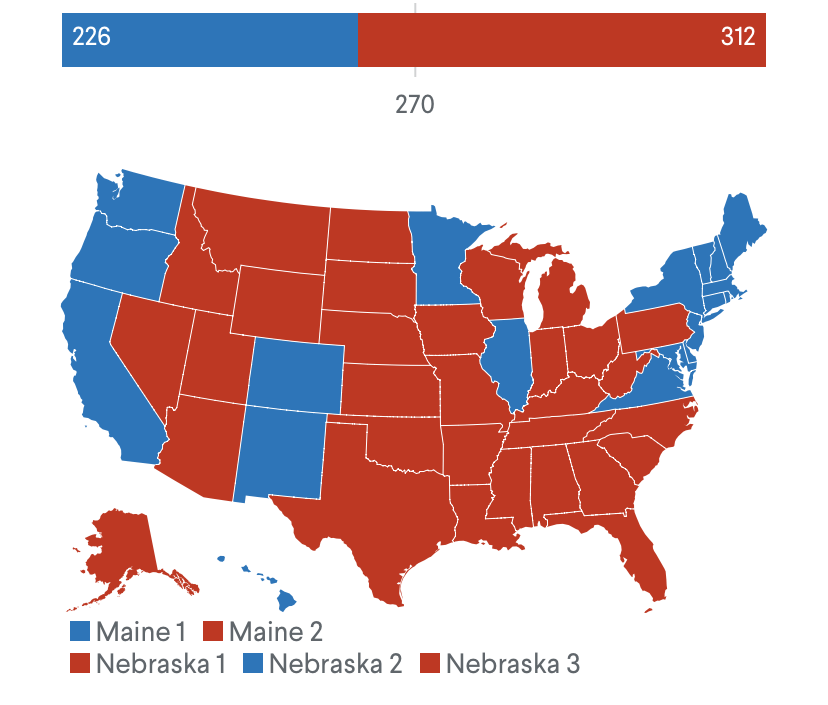

The feared violence did not happen, but a violent shock seemed present as votes were counted in a new electoral map, as the battleground states that had long been contested seem to have folded, and shifted red. But Trump’s ties to the Proud Boys–or the ties that were not only seen on January 6, but even back to the “stand down and stand by” remarks in the Clinton-Trump debate that curried so much favor with the radical alt right group. Indeed, they raise the question of whether, even if violence at the polls or voter intimidation did not occur, it still makes sense to map the electors in purely partisan terms, in this most polarized of ages, and how much that polarization rests on the personal power that Donald Trump has gained. But we have retained the map of “red” and “blue” states as a visual shorthand, dating twenty years ago on the television news, that has dominated our understanding of partisan divisions, and indeed been naturalized as a shorthand of political brand, able to take the metaphorical temperature of the nation and “decide” its leadership–even if the cartographic shorthand may be outdated in the era of the strongman. And we have forgotten how narrow the election was, as Trump has claimed a “mandate” while in fact loosing the popular vote, on the basis of winning six swing states–as if those close margins of victory, and a failure to gain a majority of the votes in what was for all practical purposes a two-candidate race, led to an electoral map that was rather divided–and offered little consensus–despite an illusion of a continuity of red states, rooted in the less educated and more economically disadvantaged ones, who bought Trump’s deceptive assurances of the arrival of lower prices on food and gas.

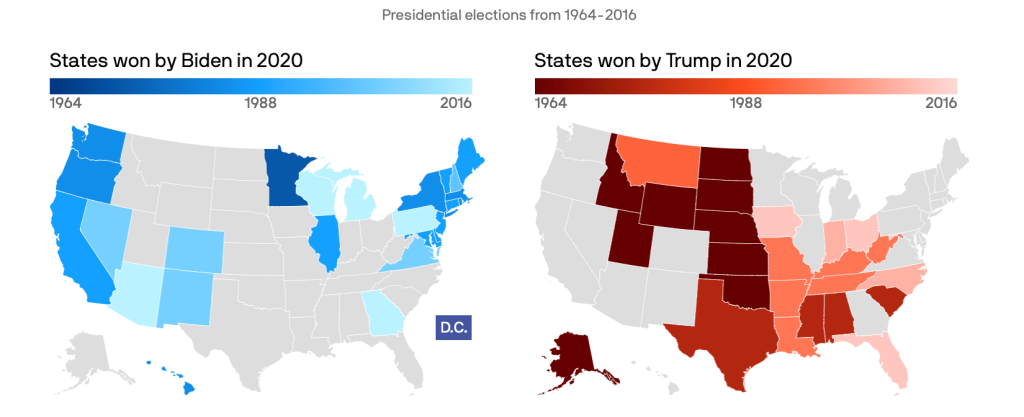

Have we allowed our minds–and our journalists’ minds–to become too filtered by the distorting principles of electoral maps? William Galston, an observer of elections and insider who worked for four presidential campaigns, ran with this cartographic metaphor, noting that if political parties had gained and lost ground in states and regions in earlier eras, we “live in an era of closely contested presidential elections without precedent in the past century.” As one candidate promises to divide us like we have never been divided, we are divided by the smallest of shifts in voting patterns, the electoral map of “the contemporary era resembles World War One, with a single, mostly immobile line of battle and endless trench warfare”–that reflect the increasingly and unprecedentedly sharp partisan tenor of our politics. Galston argued this was increasingly true in 2020, the election when states’ partisan opposition seemed to harden over forty years–if not sixty?–despite the interruptions of the Clinton and Obama years, the rare excerptions. But this divided landscape gained a terrifying sharpness that crystallized in how seven “battlegrounds” decided the election in 2024, justifying outsized attention from Presidential campaigns in the 2024 election.

Even as the United States Justice Dept. monitored twenty-seven states–and some eighty-six jurisdictions!–to ensure compliance with federal voting rights laws, prevent voter intimidation, and law enforcement agencies were braced for violence, no cases occurred–despite tangible fears of violence or intimidation. But the shock of the red map lead to existential worries of a story that ended in the wrong way. If 77,000 votes from Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania put Trump in the White House the first time, in 2016, a big push from all three states did the trick by promises to a Christian Right. Even if Harris cut Trump’s lead in the battleground states, Trump continued his advantage in battlegrounds of the light blue Democratic victories of 2020. And so the first returns in the Election Day scenario of the 2024 suggested a shift in the landscape rightwards, a mass shift Trumpwards, in fact, that had not been seen before, a shift in collective action and identity voters adopted en masse–as if rejecting partisan allegiances to run against the polarization of the past–

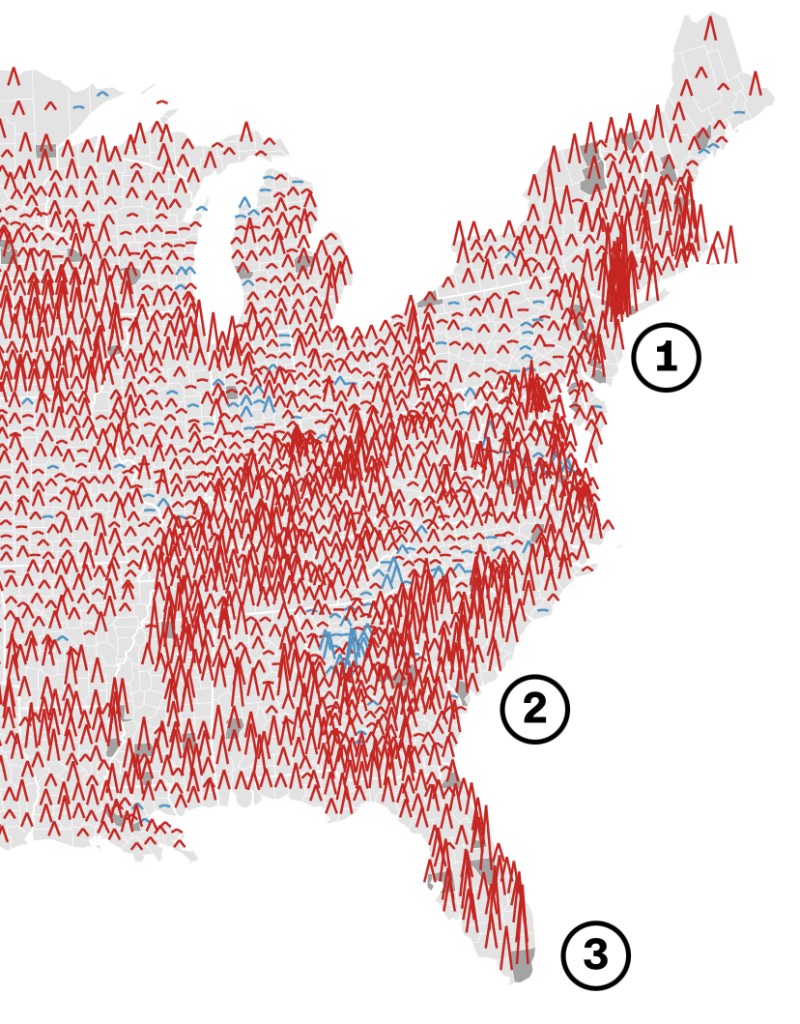

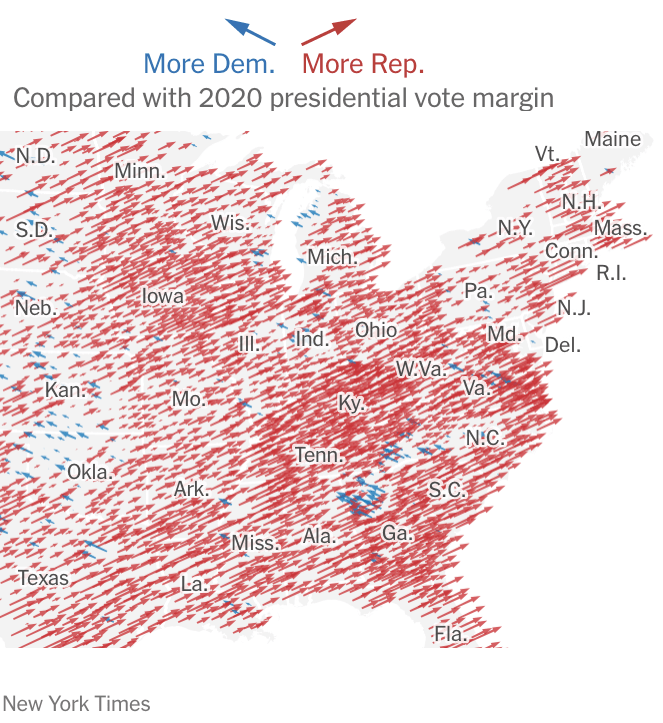

CBS News/November 7, 2024

–that provided a new landscape by the evening of November 7 of increased margins of victory from 5% to as much as 20% among for the party that had undeniably become, as many fretted, the Party of Trump, in ways that tested the carving up of the electorate into demographic groups or genders.

The array of arrows lurching red seemed to blanket the nation appeared nothing less than a major electoral paradigms. And the victory of Trump was not a victory of the GOP, but a confirmation, in some sense, of the full takeover of the Republican Party by Trump’s promises of making things right again, promises that seemed more concrete in its details–even if they were largely vague assurances, moral victories of slim benefit like the restoration of values and end of access to abortion–promises at well in exurbs, far from cities and urban disturbances, from private equity to prisons to gaming to casinos to gun advocates, finding a gospel of mall government and low taxes, a salve to anger at pandemic restrictions, an exurbia on the edges of cities, fleeing all disturbances to an elusive status quo, believing hopes of bracketing costs of global warming and near gaining a critique of Trump’s abundant lack of any actual economic plans.

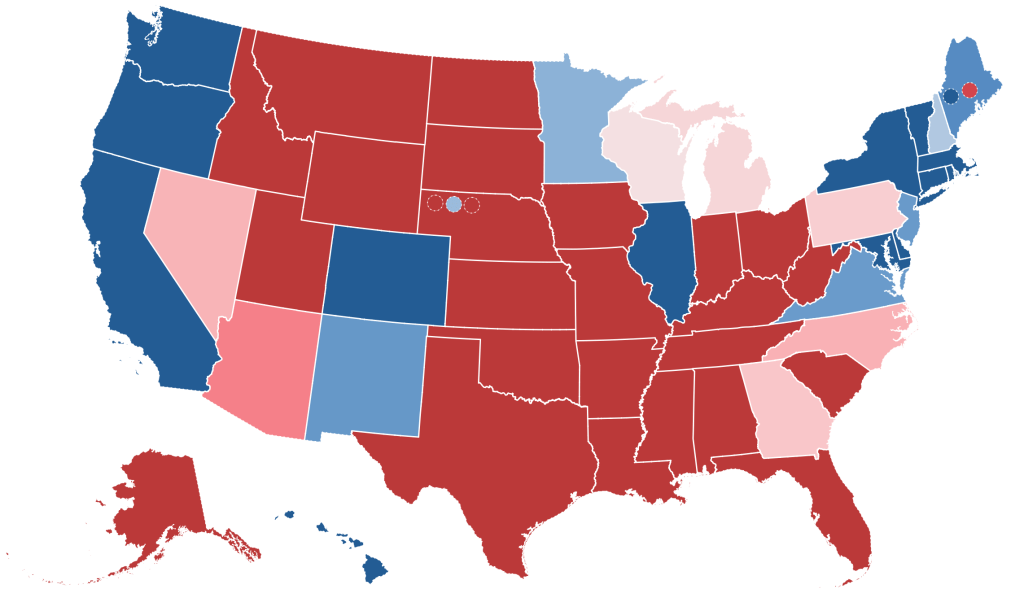

CNN, November 7, 2024

The sudden parsing of the flow of margins erased the red state-blue state electoral map, with a precinct- or county-based tally of margins from the previous election, seeking to size up candidates by socioeconomic or other groups, but confronting an apparent large-scale shift of the electorate. Trump’s victory was not overwhelming in its margins, but re-mapped most large stretches of the country red left the notion of “red” states in the past, to augur a new landscape for the United States–not only in domestic policies, but, of course, its relations to the wider world. But it was more than decisive, and the “break” in many districts once dependably mapped as Democratic voters to Republican suggested a wake-up call, even if the election was by no means a landslide: it felt like one, and that nagged one’s mind and would in days to come. And, perhaps more importantly, the perception of a landslide–even if it was by small margins–was exultantly viewed as a license to remake the government, remake the presidency, and redefine the role of government.

The bitter truth Trump did well among, non white voters, lower-income Americans, and women cannot be explained easily, and surely not by class-based disaffection from Democratic candidates.

Red Shift across American Landscape Showed a Decrease in but 240 Political Counties/New York Times

Despite fears of violence, the eery absence of any disturbances paralleled the rightward swing of the American electorate, evident in the rightward swing of voters not only in those seven “swing states” but the great majority of counties across the nation evident as the first votes were tabulated on election night. This was a punch to the right, a lurch right save spots in Georgia, South Carolina and Michigan–once considered swing states, to be sure, but now trending red. How did all the so-called “swing states,” uncertain in their voting practices but which we had been reminded from the summer, would, in fact, be selecting the President as much as the country, swing red in ways that seemed more overdetermined than seeming news?

The map hit viewers like a slap in the face, a rude awakening of heart-breaking disconnect with America, but was also cause for a recognition of deep-lying and relatively dark undercurrents that found grounds to turn away from a convincing female candidate, even in favor of a convicted felon. The bomb threats on election across swing states provoked fears of a conspiracy of Russian origins, but the lurch seemed terrifyingly home-grown and domestic, and seemed profound. It was only as more votes came in, early results revealed a shift of over 90% toward Donald Trump, a terrifying landscape indeed, but as the votes continued to be tabulated nationwide, the electoral map and the tally of votes suggested a narrow victory, in many senses, as more votes came in from California–but revealed the stubborn draw of this year’s Republican candidate, former President Donald Trump, who attracted voters across many of the states once thought in play. Candidate Trump currently only leads the vote count by 2.5 million votes nationwide, but the large turnout paradoxically benefitted him, suggested the special draw that he had as a candidate among many voters, from a far more “diverse” background than Republicans had indeed ever assembled.

Cook’s Political Report/2024 U.S. Presidential Election

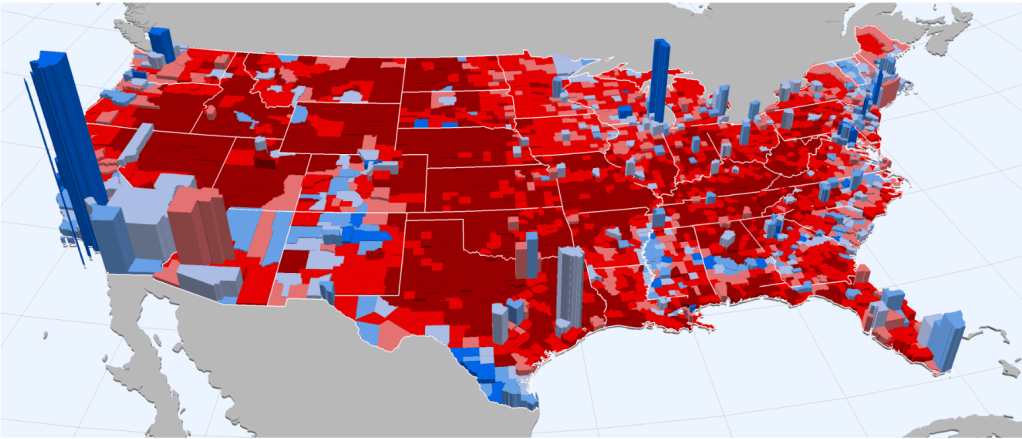

The light pink areas that were not so dominated by Republican voters presented a fractured landscape that broke the wrong way, and did so by small margins and very much perhaps for not the right reasons. But the break in votes was striking, as if able to be mapped as continuous regions. We are still haunted and traumatized by the mapping of the way the national population had split in 2016,–of siloed blue towers, removed from he rest of the land, a hived off vision of politics that we faced with frustration as Trump entered the White House for the first time–winning the backing of the interior forty-eight with an intensity not reflected in any earlier polls.

Three-Dimensional Map of 2016 United States Presidential Election at County Level Light to Dark Red and Blue Showing Democratic and Republican Votes and Voting Density

We had pored over those maps that haunted our minds with endless precision as data arrived on county and district level, to search for signs of the anatomy of the loss, hoping to grasp the gaping division of the national vote. Did Trump’s continued appeal redraw the political landscape, or was there something wrong baked into aggregating the general will? Did tailored talking points about access to abortion and an attack on price-gouging fail to motivate voters, or provide a convincing narrative of steering a more vital economy, or at least a convincing trust in the law?

Or, the voting map almost seems to beg the question, were we relying on the wrong maps as we focus on electoral maps, and ceaselessly made new maps for electoral prediction, seeking to craft multiple scenarios for how electoral votes would fall out this time, scenarios whose endless proliferation seemed a suspension of agency? The real maps of the election lie far outside demographic metrics not mapped by demographics or class or race or gender divides, but a space of a lost community, where the battle cry to Make America Great Again exercised undeniable appeal.

The massive scale of the red shift evident by the morning after Election Day was a wake-up call that suggested a changed landscape. The red arrows lurching right seemed evidence of a disconnect of Democratic campaigns and candidates that provoked an immediate introspection and conveyed the shock many felt in he nation. Amazingly, rather than the election being close in any way, it seemed, the election that was long said to come down to thin margins of voters, per the polls, were upended. Trump’s margins built on 2020 and significantly grew in 2,367 counties nationwide. The red arrows overwhelmed any of the fears of heightened violence in Trump’s political rhetoric elected, with the demonization of opponents, or indeed just suggested they were meaningful rallying cries far more successful than polls had showed or political junkies had expected.

Continue reading