The Atlas of True Names (2008) promises a legible cartographical surface clarifying confusions–although this enterprise is, in fact, less of a rebuttal to the deceptions of maps than based on whimsical fancy, the placid surface and mutely authoritative capitals of its densely written surface are something like a response to the comprehensive coverage of Google Maps. Here, erudition crowds the visual surface of the map that draws its viewer onward across its surface on something more like a treasure hunt for amusement than a normal trajectory through space. The text-based format of the map, whose traditional appearance and muted topographic coloring are equivalent to a calm reassuring voice, are a very retro surface, but as one looks closer, familiarity gives way to surprise: for the translation of each place-name into the literal meaning of its signifier unpacks the familiar surface of the map. The product on view gives new meaning to legible cartographical representations of expanse–or for that matter to maps as texts–by providing a map of the “true meanings” of toponymy in other maps, by a kind of reductio ad absurdum of etymological origins.

As we look at it, to be sure, we seem to be falling down something of a rabbit-hole, of which maps hang on each side, as for Alice; for the map retains few familiar names. The maps in the Atlas of True Names remind us of the extent to which our understanding of mapped space is determined by the location of names we read on maps’ surfaces, as much as other map signs. Rather than use big data, the map of North America boasts data as small, and apparently as old, as one can get:

There’s more than a bit of wacked-out humor in the map’s subversion of the schoolroom hanging map used to study the states’ capitals or high-school text of history. But just as the notion of “United States of The Home Ruler” seems inconceivable in a pre-Homeland Security world, and independent of etymological reconstruction, between the staid “Land of Settlement” and prosaic “Navel of the Moon,” the politics by which this atlas retrofits the map as object merit examination as remapping an inhabited space. As much as a novelty, the marketing of this atlas returns us to the map we grew up with, and winkingly suggests what good map-readers we are.

In recasting such a familiar region with “true” place-names, map-reading becomes an exercise not only of re-reading toponyms with a thesaurus in hand, but an exercise of refamiliarizing ourselves with the naming of places that we know. The notion of locating truth in maps might unintentionally echo an eery undercurrent scarily similar to the right-wing thirst for transparency in politics: the shifted place-names of this project of re-mapping boasts the title of the “The Atlas of True Names” as if to curry to a skepticism in how place-names determined by multiple interests–even if the exercise in whimsy also aspires to enchantment. Replacing the names we’d expect encourages to read the cartographical surface with the sort of pleasure of discovery of place-names we might have while headed to a radiant Emerald City past Truth Mountain, Winkie River and Rigamarole.

But we’re in Kansas; not in Winkie-Land. For American readers, the flattening of places into a register of quasi-scriptural authority of place seems to be an echo of the sort of national essentialism of the map–even if this was far removed from what the pleasant couple who designed it in their native Lübeck, here the “Lovely City,” might have actually intended. Indeed, the negotiation of place names that began from custom and usage, is all but erased in the replacement of toponymy with a “true” origin that leaves Texas “Land of Friends” and Maine the “Land of Folks” and just reminds us of the darned problems of relating signifiers to signified. Cuba as “Place to Find Gold” is transposed from a treasure map, but once removed from “X-marks-the-spot” deictic pointers, seems robbed of meaning.

Consider, for one, the range of names that were lost or purged from the maps that we use to navigate the Bay Area alone, let alone the entire American West, in this intensive compilation of native names for place in circa 1760 since erased from our own cartographical records of the same area:

Or consider the active role of colonizers in the renaming of regions, places and islands over time and human history so evident in the band around the equator:

Which brings us to the odd title of the atlas, sold for an unclear audience. The claim to be “true” seems particularly questionable in its flattening of the historical richness of the thick descriptions any map recapitulates. While I don’t want to question or assail the attempt to “re-enchant” a space whose meanings mutated over time, the problem of viewing the layers of history as a matter of direct translation forgets that the past of any place is itself another country, if not a sequence of multiple worlds, that a one-to-one re-matching also threatens to impoverish at the same time as essentialize. And as much as re-enchanting, there’s the sense that this pair of married cartographers, Stephan Hormes and Silke Peust, put their readers in the position of Alice, who “had not the slightest idea what Latitude was, or Longitude either, but she thought they were nice grand words to say,” but found the words compelling and so intelligent. Truthfulness and maps are an odd combination: the map is a register of actuality, but a polyglot rendering of actuality.

Yet as if disclosing hidden knowledge, even while barely maintaining a straight face, the unwitting effect of the “True Names” project is to flatten the historical accretion but also multi-cultural negotiations that provide the back story of the formation of place-names on the map. The heaviness of “The Land of Settlement” that overhangs the familiar forty-eight, and the prosaic “Land of Cloudy Water” and “Land of the Shallow Water” aside, and even the romance of the “Land of the People with Dugout Canoes,” or “Land of Folks,” the notion is that this map has the true stuff for its readers. Like the “Houses at the Foot of the Mountains” or the “Land of the People with Tall Caps” north of modern Pakistan.

The Anglicized toponymy of place is not only an etymological translation, but a sort of re-rendering of loci that invests the surface of the map with a epic-like declarative identification. Of course, you don’t have to wander far: Paris is the “City of Boat-Men,” and England (Great Britain) “Great Land of the Tattoed,” as any reader of Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars might remember his description of the blue-painted men standing on the cliffs of Dover. Hormes created the map together with his wife with aspirations to recreate ” an insight into what the people saw when they first looked at a place, almost with the eyes of children” as they encountered its topography, as if wandering for the first time in a country before time and seeking to capture local particularities, or to see the place for the mythical primeval time.

The inspiration of this map, and indeed for the treatment of mapping as a commercial enterprise, is less a report actual localities or surveying, than a removed activity of toponymic transcription, here under the guise or mask of Teutonic erudition more than compilation of unknown spaces; the idea is to make known space unknown or known again. The aim is a sort of time-travel and a wiping clean of the slate of culture: “Through the maps, we wanted to show what they saw,” he explained, eliding the palimpsestic quality of the map itself. But the standards are not particularly high, as the goal seems to be to amuse. There’s a certain failure to capture the acts of translation whereby a current English or American name descended from a French or other place-name, as Buffalo NY from belle fleuve, or for that matter recast “Rome” which appears as “Central City,” or even New York’s stint as New Amsterdam until 1644: and even as late as 1630, colonists noted the divergent spellings of Mattachusetts, Massatusetts Bay, and Massachusetts, without seeing the need to arrive at orthographic stability. And so perhaps a history of toponyms’ mutation can be included in the online version, bedecked with hypertext. But learning is not the point, of course; and neither is a history of usage.

There is quite a bit of fun in imagining the renaming of the continuous 48 states with new identities like recasting Illinois as the “Land of Those Who Speak Well” or “Land of the Pale Faces,” even though the latter might now cover the entire continent:

The imaginative etymological reconstructions are a source of delight, if they don’t always successfully re-enchant mapped space and may also raise eyebrows. Few won’t love such place-names like the “Land of the Cloud Water” or “The Sea of Weeds” or “Navel of the Moon” that give a quasi-biblical authority to what we usually read on the surface of the map most of us have known from first or second grade. Even despite the familiarity of some names–“Oakland” and “Salt Lake City” among them on the map, the diversity and history of the transmission of place-names are somehow flattened out to a single surface in one fell typographical stroke. It might be, moreover, that the location of ‘trueness’ in the names suggests both a sense of what the surface of the map usually hides and a barely conceals the right-wing paranoia at a conspiracy perpetrated even against us map-readers–echoing if not somehow analogous to the fears of a conspiracy that the falsity of Barack Obama’s Hawaiian birth-certificate has been recently reconfirmed which vigilant readers of the Wall Street Journal continue to post in the responses to articles for whoever is listening. The renaming of “true” place-names somehow contains an element of rectifying the deceits long perpetuated by state-trained cartographers obscure, with a healthy skepticism toward the authority transmitted in maps: this almost seems the latest echo of Richard Hofstadter’s paranoid streak that shapes politics, in which politics was an “arena for angry minds” –if not in such Manichaean terms as Hofstadter argued, but rather a sense that the signifiers associated with the place might be better decoupled from them, lest we naturalize the map’s surface, or mistake it for the territory.

One can imagine the scriptural significance that certain readers would paradoxically invest in the 2008 corpus of maps. Although the two practiced cartographers mobilized an array of Old World erudition, and they clearly took some pleasure in tracing back, from the port of Halifax, “Remote Corner where Rough Grass Grows,” the act of renaming was something of an inversion of the cartographer’s task of “put[ting] as much information as possible in a single image.” For in this case, the image is not what makes the information assembled accessible after all, so much as a the quasi-scriptural authority invested, with some imaginative leaps, in place-names that repopulate its surface, and shift the ground beneath one’s feet. How is Hudson’s Bay (and other places linked to proper names) given true immediacy when Heartion’s Bay? Quasi-scriptural is not a misnomer given the solemn intoning of places like “Land Towards which the Sea Flows” or “Mountainous Land” across the map.

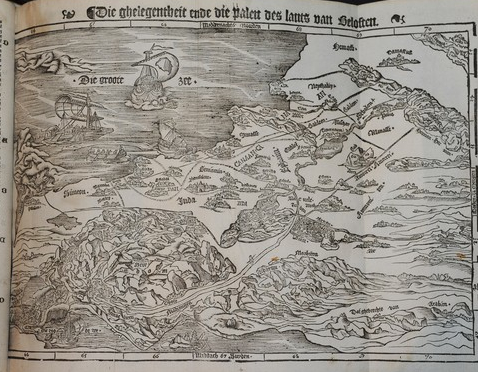

The sort of transparent legibility of the printed word seems vaguely Lutheran in its notion of a return to a scriptural truth, and indeed it echoes the enjoyment Luther himself took in including in his German-language Bible a supplemental map of the Holy Land. The map, derived from the circa 1509 map Lucas Cranach had engraved of the region, was intended to satisfy readers’ curiosity of Holy place-names. The reprinted version of Cranach’s map, with its toponymy expanded, is an example of the promise print offered to the legibility of the surface of the map. Here is a version reprinted in a Dutch Bible of the 1542, revealing the course of Exodus and lending concrete meaning to those temporally removed events so that one could witness them anew:

The sort of legibility that print promised provided access to an assembly of spatial relations that was not earlier in the ken of most readers. The landscape map that provides a basis to understand Exodus invested a material presence to a set of quasi-mystical names long transmitted without a clear sense of their actual locations. We are now perhaps not reading a map, but playing something like a post-modern parlor game. In contrast to Cranach’s useful collation of toponyms in the sacred text, many of these etymological reconstructions are amusing to imagine as modern road maps.

“Mom and Dad! We’re finally at the City of Many Fish! And I can see the Peak of the Bearer-of-the-Annointed-One Dove in the distance!” “Hurray! We’re at Place by the Meadow in the Land of Friends! Let’s get out of the car!” This is the absurdism of etymological archeology, erasing the traces of population or local history in the hopes of a new essentialism of world myth. While all this is overwhelming, a focus on one contested region of the world–and attendant diminishing of wacky amusement that comes with time and repeated map-reading–suggests the odd comfort that comes from an erasure of the multicultural contexts of the evolution of place-names discussed, among others, by how George R. Stewart famously romanced American toponymy in his historical account of place-naming that traced in a somewhat dry manner the negotiation of practices place-naming, ceremonies of possession, and textual corruptions mediated and brokered by inter-cultural contact and aspirations, documenting the translation of French or Indian terms to Anglicized place-names or orthographic shifts over time.

Indeed, a somewhat reverse pattern of trying to map primeval names for places from their modern proper nouns seem to cast some doubt on the philological rigor of the project as a whole: the city first identified in the map’s first edition as “New Wild Boar Village,” was back-traced from “Nova Eboraca” (New York), despite the boar having questionable homonymic relationship. (‘New Yew-Tree Village,’ reads the current map, although one isn’t sure how that relates to an earlier encounter with space not mediated by a number of encounters with lexicons; old maps, which might have provided “New Amsterdam,” are not noted or considered.) Yet the prosaic image of yew-trees offer little sense of what York meant to the Romans or Britons, and the Latin toponymy might not even have been primarily vegetal in intent. Other familiar places seem similarly distorted by an etymological imaginary or fanciful but sloppy erudition: “Saint Little Frank One” seems a forced upstream etymology of “San Francisco,” inanely confounding “frank” as proper name and adjective. And how does “United States of the Home,” with its unintended echo of the Homeland Security Department, line up with Amerigo Vespucci? Why (on earth) is the city of fallen angels, “Los Angeles,” more transparently or truly registered as “The Messengers”?

What’s gained in the new linguistic transparency that this re-insertion of English toponymy for a rich cultural canvas of the surface of the map? The more circumscribed focus on a map of the western US and southern California make more clear what’s lost in the flattening of historical encounter with space, however much it might satisfy the English Only crowd, a sanitized landscape where we are given the impression of being able to truly understand what the foreign tongue both mystified and masqueraded as euphonious for our ears, so present in much of the American midwest.

Some of the unsettling unheimlichkeit of the map may derive from the impression that the place-names have been taken off the map, put in a vat of acid, or a very hot rinse, and then put back in place on its surface. Recasting the map as something like a Google Translator program’s reading of place seems to respond to fears of the messiness of globalization, by rewriting the maps in our own lingua franca to erase the multicultural messiness found on the map. With everything has now been translated to English, at last, a properly legible text promises a true uniformity to project English only on any foreign labeling of place, extricating the map entire from its web of polyglot diversity in a newly proprietary way. The result is something of a comic fantasy of map-reading that has a somewhat J. R. R. Tolkein-ish tinge, or, in the case of the Land of Five Rivers, Horsemen, and Turtles, the sound of Dada-ist language poetry that calls into question the cultural specificity of very process of naming places on maps. “Once the names have been taken back to their roots and translated into English,” Hormes and Peust boast, “it is immediately apparent that our own world has an extraordinary affinity with Middle-earth,” we learn, “clearly rooted in Man’s observation of his natural environment and [the] physical location of a settlement.” (Holmes admitted that his own interest in maps can be traced back to a childhood obsession with The Lord of the Rings, which presents a toponymy “so clear that every child understands it,”–even before the cinematic recreation of Mt. Doom let it enter most kids’ imaginations–in his map the Mediterranean is after all “The Sea of Middle Earth.”)

Am I wrong to see something monolithic and oddly neo-fascist in their alleged “re-enchantment” of a drawn, or re-written, cartographical space? The sort of verbal dominance over localities may be less explicit, but it is somehow just as insidious, if not tongue-in-cheek about the authority maps hold. I don’t mean to be so harsh. Although its authors openly aspired “restore an element of enchantment to the world we all think we know so well,” and allow readers to “take a look at the world with fresh eyes,” even the Atlas of True Names “United States of the Home Ruler” or “Great Land of the Tattooed” playfully suggests a level of transparency to the map that seems to push back against globalization by returning to a familiar idiom and tongue.

If Stewart’s classic study of American toponymy traced the negotiation with American Indian place-names, the reduction to one language is a cultural flattening of the surface of the map, in a somewhat paradoxical Enlightenment project of making inhabited space visible–or lisable–in the sense that legibility trumps space or cultural remove. But the mobilization of this linguistic erudition into an enterprise pushing back against the world connected by the internet to restore wonder of creating an identifiable relation to space onto the surface of the individual map. The problem with attempting to restore such a sense of wonder is magnified when we deal with other cultures, where one finds echoes of the land of Marco Polo on the Spice Route, from the “Land of the Tribal Homelands” and “Land of the Fire-Keepers” (Azerbajan) along the “Golden Mountains” to “Riceland” (China); the “Town of Happiness” lies comfortably near the “City of One Who Aspires to Enlightenment,” perhaps the city of naked philosophers or gymnosophists inhabiting the edges of the worlds mapped by medieval men.

There is a certain Teutonic Enlightened strain in the bleaching of past history in the name of one mother (or father) tongue. Shifting the names of places is a way of getting you to pay attention to the entire surface of the map for something surprising or out of the ordinary, but also flattens the aura of far-off places in a sadly normative fashion, creating something like a new level of two-dimensionality by robbing places of the imagined accretions and associations all place-names have. There’s something sad of the absence of the romance of the map that results, in which even London seems pretty absurd as the “Unfordable River Town,” though the unaffordable river town it might be.

Indeed, the romance of space is entirely tied to the euphonious nature of place. Even Frances Mayes herself might have trouble writing about the Tuscan Sun by living outside The Blossoming One, in the sun-drenched Hilly Mountains–the very practice of cross-cultural translation that she professes is itself flattened by the absent assonance in the toponymy that these maps of Italy and Tuscany afford budding poets. Even though “The Land of Calves” and “Rainland” seem romantically appealing in their own right: but they don’t sound like the euphonious landscape filled with ginestre and tromboni, as well as the lovely vibrant tastes of basilico.

White-washed to an English rooted in etymological derivations, the landscape is in an odd way de-peopled or depopulated as it is removed from how place is spoken, and re-mapped, by the people living in its landscape. There’s a child-like naiveté we get from reading the maps’ place-names, which mystify even the locations that we know all too well. There is the odd sense that from a space in fragments, these cartographers are trying to create a new wonder of the whole, arrogating authority of naming to themselves in the name of recuperating an initial primeval confrontation with a topographic landscape. The task seems in part to invest immediacy in the world as it is encountered in each place in a comprehensive topographic map–without considering the synthetic nature of the fabrication of cartographical space, and although this seems at odds with the synthetic construction of a uniform distribution of spatial relations. It seems the cartographers took a digitized image to re-write the toponyms they found with evocative substitutes, but chose to keep some, as “Oakland,” “Riverside,” “Long Beach,” or “Salt Lake City,” as such were sufficient topographic descriptors in themselves. In seeking to preserve the essence of each name as much as they can, they may unwittingly undermine forging continuity in the heterogeneous surfaces of mapped space.