The recent official prohibition issued in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar against tattooing a map of the country “below the waist” at the risk of carceral punishment suggests an unlikely overlap between mapped geography and bodily topography. In according symbolic status to tattooed maps is not particularly new–but the degradation of the country by a permanent tattoo inked below the waist has rarely been seen as meriting fines and a sentence of up to three years imprisonment. The decree reveals a heightened concern for the debasing of a national map in a country riven by some of the longest running ethnic strife and civil wars in the world: U Ye Aung Mint informed a regional assembly at Mandalay that the government worried that while “this [same] symbol tattooed on the upper part of the body because it might demonstrate the wearer’s pride in their country, but a tattoo on the lower part disgraces the country’s pride,” he sought at a time of civil unrest to prevent “disgrace” of the map when it was transposed to “an inappropriate part of the [human] body” and written on one’s skin as an intentional insult to the nation inscribed on the body.

Perhaps because the art of tattooing has been an import of Americans into Iraq, rather than a local art, that was prohibited by the dictator Saddam Hussein under Islamic law, when it was considered haram and a desecration of God’s creation of the human body, an increasingly adoption of the map-tattoo was more of a conscious imitation of American occupiers, and an import of the American invasion of the country: indeed, often inspired by the tattoos seen on the skin of foreign soldiers, the rise of tattoo parlors in Baghdad is something of a novelty–as are the mostly angry designs illustrating flaming skulls, razor coils of wire, or heavy metal band logos that were increasingly sought out in tattoo parlors in the war zone–even if Iraqi-American artist Wafaa Bilal used his body to create a map of American and Iraqi casualties, the latter of which were revealed to audiences under uv light. But the emergence of maps as signs of bodily resistance to ISIL‘s hopes to redraw a Levantine map–in an eery reworking of the growth of tattooing as a means to identify the bodies of those fearful of dying unclaimed in the Iraqi War–seems a particularly striking oddity as an illustration of patriotism and iconic badge inscribed on the body:

The tattooing of world or national maps on one’s own body is more often less intended as an elevation or degradation than a celebration of a map’s formal elegance–dissociated from a form of spatial orientation. But the newfound popularity of maps as tattoos reveals an only somewhat unexpected transposition of the virtuosic artisanal craft of map making to one of the most productive areas of inventive printmaking, or perhaps the arena of artisanal production that touches the greatest growing not-that-underground audience of visual consumption and display. While graphic designers readily transpose any image to any surface, there is something neatly cheeky about transposing the global map to the most local site of the body: a return of the scriptural forms of mapping in an age of the hand-held, and an assertion of the individual intimacy of reading a map–reducing the inhabited world to a single surface–in the age of the obsolescence of the printed map.

The bodily inscription of maps might be seen as an act of political protest in Myanmar, and tattooing offers a declarative statement not easily removed from one’s body, but the abstract image of the map seems more often cast as a decorative art among groups rapidly searching for engaging (and ultimately visually entrancing) forms of bodily adornment rarely seeking to insult the integrity of the territory by linking it to the lower-regions of the body authorities seem to fear. Given the proliferation of tattooed maps, we might join a hero in Geoff Nicolson’s crime novel which features the forcible tattooing of territorial maps on the bodies of victims in observing, once again, that “the map is not the territory.”

Despite the relatively recent decline of the printed map, the elegance of the map’s construction makes a widespread migration of the format and symbolism of engraved maps onto human flesh across the world as a decorative form of bodily marking an almost foregone conclusion. Could the elegance of the delineation of the map’s surface not have migrated to body art sooner or later? The vogue seems to correspond not to a shifting threshold of pain, but the expansion of tattooers’ repertoire, and the search for increasingly inventive images to be written onto the skin. Unlike the expansion of tattoos that mark place or origin, or offer bearings of travel, the growing popularity of its most highly symbolic forms recuperate the deeply scriptural origins of cartography, as the stylus of tattooing consciously imitates the elegance of the burin and imitates a lost art of map making whose formally elegant construction is now displayed on one’s skin. The humiliation implied of degrading the territory by mapping it to the “lower” body parts in Myanmar seems removed, however, from the recent fad of appropriating the map’s design as a form of visual expression. Historians of cartography, take note of this new surface of cartographical writing.

Seafarers used tattoos to plot their oceanic migrations without regard for territorial bounds, and sites for public reading, as it were, of one’s past travels. The tattoos of sailors or merchant marines used to be symbols of world travel, by charting oceanic migrations: tattoos offered self-identifying tools to a seagoing group and evidence of sea-faring experience–the “fully-rigged ship” a sign of rounding Cape Horn; the old standard of the anchor the sign of the Merchant Marine or the sign of Atlantic passage; dragons signified transit to the Far East; a tattoo of Neptune if one crossed the equator–and the ports often noted, in the form of a list, on a sailor’s forearm. (The icon seems repeated with some popularity in the eight-point compasses often observed on inner wrists among the tattooed crowd in Oakland, CA.) Only recently did the prevalence of modern tattooing led to the circumscription of permissibility for tattoos as a form of “bodily adornment”: in January, 2003, Navy personnel were newly prohibited from being inked with “tattoos/body art/brands that are [deemed] excessive, obscene, sexually explicit or advocate or symbolize sex, gender, racial, religious, ethnic or national origin discrimination . . . . [as well as] tattoos/body art/brands that advocate or symbolize gang affiliations, supremacist or extremist groups, or drug use.” The fear that conspicuous gang-related affiliations would challenge the decorum of membership in the Navy eclipsed the innovation of marking experience of world travel, in an attempt to contain the practice of tattooing that was already widespread among Navy officers.

So popular is the tattoo as an art of self-adornment that the Navy’s explicit proscription was partially rescinded by 2006, suggesting the inseparability from the navy and the tattoo, and the separation of tattoo from travel: tattooing would from then be permitted, the US Navy ruled, only if the tattoo in question was neither “indecent” or above the neckline, so long as it also remained registered in the tattooed individual’s military file. In a country of which over one-fifth of whose population possesses at least one tattoo, according to a 2012 national survey, the practice was less easily tarred with accusations of indecorousness, and might even hamper the number of eligible naval recruits. The diffusion of tattooing as a form of self-adornment has in part made maps particularly popular genres of tattooing, as a way to track mobility and worldliness beyond the seafaring set. The adoption of the map as a flat declaration has a sort of nostalgic whimsy born of anachronism. In an age when our locations–and travels–are stored on smartphones that encrypt data of geolocation into KML files, the map is a trusty declaration of intention as much as of orientation, the tattooed map reveals a public form of reading and a fetishization of the map as legible, if coded, space–although cartographical distortion is rarely an issue with the tattooed, who prize the map’s elegance more than debate about its exactitude of the precision of transferring expanse to a flat surface: what is written on the body seems distorted perforce, given the curvature of body parts as the upper back or its irregular surface. And for whatever reasons, the difficulty of ordering uniform graticules seems to make them rare in the tattoo art collected below from Pinterest–where the growing popularity of the map as icon seems something like a popular logo of individual worldliness, if not an inscription of something like a personal atlas–or whatever one is to make of the map in the age of digital reproduction.

The proliferation of the map as a form of invention, both as form of generic wonder and a potentially personalized site of self-decoration, might be said to reflect the expanded audiences that emerged for the first printed maps as treasured commodities for public (and personal) display in early modern Europe. But the popularity of noting space and place personalized tattooing represents one of the best instances in which one can make the map one’s own. Mr. William Passman, a retired 59 year old financial planner from Louisiana, collects maps of the countries he’s visited in an interesting and highly personal manner as a basis for his own personal travelogue that he has inscribed (or dyed) on his upper back. Passman’s decision to tattoo a graphic travelogue of his journeys to different continents stands at the intersection between a culture of conspicuous tattooing and the age of the info graphic: he chose the template of a blank world map, roughly in the iconic corrected Mercator projection, actually inscribed on his back in an unusual way, as a chart or mnemonic device to note countries he visited during his life, treating his skin as the canvass for an atlas for his travels.

The backpacker, outdoorsman and blogger treated the tattooing practice as something like a diary–or log of travels written on his own back–that could be readily updated and expanded at tattoo parlors, and ready updated as it was reposted online. And so when Mr. Passman had time to visit Antarctica, a new favorite tourist destination, he added the country that was omitted from the already expansive tattoo on his back, significantly expanding its coverage and apparently taking up (or taking advantage of) most all the available surface skin that remained–creating a virtual (if also quite physical) travelogue of his experiences:

Passman intends to “update” his set of tattoos beyond the 75-80 countries he had visited when last interviewed, and is eager to add countries upon his return, treating his body as a legible diary. A recent visit to Antigua hence prompted a visit back to the local Tattoo parlor to alter his personal map:

The coloration of the back dispenses with the four-color system of cartography, seeming to use a stylized system of its own. Passman began to tattoo a blank map on his upper back, delineated carefully to thicken certain coastal shorelines, and a blank slate as if to facilitate their coloration–

–most cartographical tattoos remain monochrome, as if in order to better preserve their graphical design and to recall the aesthetic of early modern map engraving, and push the limits of personal adornment by inscribing something like a cartographical text on one’s own body. (Tattooing was, in early modern Europe, viewed as distinguishing indigenous peoples who imprinted “finer figures” into their skin, unlike Europeans.)

The deep-skin-dying of maps of global expanse seems to court the macrocosm-microcosm conceit of the Renaissance, locating the whole world on the single body of one resident, condensing expanse to a symbolic form in ways that only maps can do, complete with the visual devices of engravers to signify the spaciousness of the chart and the substantiality of territories by darkening their edges’ interior, in vague imitation of the shading on the coasts of land regions in engraved shaded lines of intaglio maps.

Other maps formats of world map tattoos suggest the format of Old World/New World transposes nicely onto two feet, with an eight-point compass inset:

It is striking that he is not alone, although it seems that Antarctica and Greenland may be absent from the templates of other tattoo artists, and which Fed Jacobs judged to be “the most popular cartographic tattoo”, of the maps on upper backs, usually appearing without the addition of the southernmost continent:

If these images of the generic upper back tattoo–a bodily region not the most painful to be inked, if fairly high on the pain scale, taking longer to tattoo and also to heal–although that compass rose to the right of the spinal column seemed to have hurt given its pink surrounding skin–suggest the map as a form of bourgeois adornment among a Facebook-using set, one can see this map-tattoo catching on as a conscious sign of cosmopolitanism, in this image from Inked magazine, at times revising the conspicuous display of globalism in this Atlas-like image of sustaining the earth on one’s shoulder, for a far less exhibitionist image befitting the pedestrian world-traveller:

Glyphs from maps, like compass roses, are especially treasured forms of adornment, with directional signs or without, like this exquisitely colored compass rose from a nautical chart, designed in Crucial Tattoo in Salisbury, MD by Jonathan Kellogg:

More rare is a map that emphasizes the graticule’s transposition of terrestrial curvature–or a map that is actually antique in its inscription of separate hemispheres:

Henricus Hondius, Nova Todas Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula (1641)

Or, in a widely repinned work by Annie Lloyd of considerable elegance:

Is there a sense that the tattoo shows one in morning for the disappearance of the paper map? Or a devaluation of the real world, whose form is now effectively incorporated as a form of purely personal adornment?

The pleasure of the world map’s spatial curvature might, however, might be better transposed to the present in one image posted from Miami, Florida, whose contour lines seem inscribed onto the curvature of embodied flesh in ways that invite the experience of map reading more than only celebrate the map as a static symbolic form, as “infinitely entertaining . . . to give you pause,” expanding the cartographical canvas to the entire back, arms, and side, as well as the tops of the shoulder, treating the body as the ultimate surface of inscription:

What is the logic of making such maps, not too easily consulted by oneself, for one to carry around, save as providing the extension of making one’s own body a text for others to read? If, to be sure, this can be achieved in fairly exhibitionist ways, the imaging of the world can literally transform one’s body to texts that recuperate the elegance of the engraved map, replete with the transposition of parallels and meridians to the curves of the back and arms, in ways can’t help but invite the body’s surface to be close read that almost seem a dare or challenge to even a passing observer, expanding the inscribed surface of the body to almost make the body no longer recognizable as flesh:

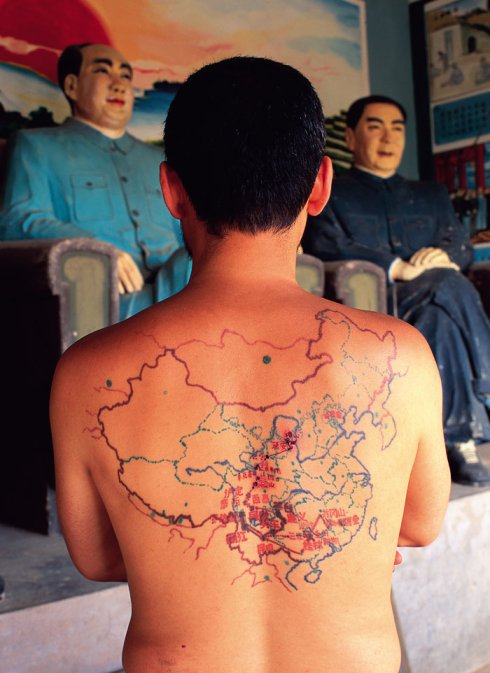

And the practice of taking the back as the surface for world-mapping may have heavily ironic, as much as celebratory or encomiastic ends. The encomiastic function of maps lends itself to something like mockery in this retracing of the itinerary of the Red Army’s Long March, here before life-like wax images of two icons of the March, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, which cannot help but evoke the costs that the March wrecked on actual living bodies:

China mapped on one’s back, facing Mao Zedong and Chao En Al

The exhibitionism of cartography can mutate what is an emblem of unity for personal ends, as this image that transforms the surface of a strictly cartographical text, inscribing the map not on shoulders but one’s chest, and rewriting the contours of mapped space as a glyph-like colored design:

Given the popularity of the heart-shaped sign as an almost plastic tattoo, not only a currently fashionable, but a compellingly popular graphic to inscribe one’s emotional commitment on one’s flesh,or as an anatomically precise image, is it a matter of time that we see the occurrence beside the flaming heart tattoo, or “heart lock,” of the cordiform world of the Renaissance cartographer Oronce Finé? Or is it too challenging to needle?

More modest in scope, the tattooed map can of course also offer a nice example of locally rootedness, rather than cosmopolitanism, as in this person from the French region of Brittany, hearkening back to something like a sailing chart or the scroll of a treasure map in its cursive toponyms:

Or of a the bathymetric conventions of the precipitous depth of the mountain lake to depict sites even more specific as a place and time, making them somehow more mysteriously compelling by a detailed map than the mere addition of the name could offer:

For those inclined to more literary identifications, and whimsical definitions of provenance in an anti-territory, rather than an actual one, one might express the limitless of one’s affiliation by an image of the map, as if it were a badge of affinity to C.S. Lewis’ secret world, as well as invite acknowledgment of a sign of common readership–in ways that broadcast the scriptural significance of the Narnian map and the domains of the kings and queens of Cair Paravel (and land of Aslan):

Or, in ways that great one’s body as an even more expansive text, the equally mythologized territory of Middle Earth as a way of expressing an alternative orientation to the world, replete with J. R. R. Tolkein’s own cartographical evocation of a neo-medieval scriptural realm, as if to invite viewers to enter into the complexities of its imaginary space of Middle Earth, with a detail that evokes true fandom in apparently obsessive form, if not a battle between good and evil:

These tattoos are particularly difficult to remove, and not particularly legible, but that seems beside the point.

The migration of the map from the paper to the skin seems to treat the map as the ultimate aestheticization of body and the expansion of the treatment of flesh as inscribed surface: the tattoo is most often an image of transcendence than of pinning one to a location, using the power of maps to escape spatial categorization.

But perhaps the utmost expression of the obsolescence of the map in tattoo remains the simple contrast between tattoo and image, and the apparent revenge, in this photo, of the body against the map, which seems to remind us in the deliberately anachronic juxtaposition of contemporary technologies of travel from the antiquated map:

This is a terrific post–so full of ideas and connections. Do you think that wearing the world on your sleeve, or back, or wherever is a response to the fear that the planet is insufficiently valued? ________________________________________

It certainly is a way of turning attention away from its environment. Perhaps it’s a way of throwing up one’s hands as to the many ways in which parts of the world are increasingly interconnected.