When William Rankin mapped city income donuts across urban America in 2006, the radical cartographer aimed to correlate wealth distributions onto a geometry of concentric circles. But the donuts of income distribution within the Bay Area do suggest the wedded nature of the bay’s shorelines with distinctly lower incomes, reflecting the deep historical association–outside Marin, but only partly–of the bay’s shore with heavy industry and piers. The distribution reveals the reduced desirability of living by its often polluted shorelines before their restoration–as much as it recalls the concentric rings of the mapping of flight paths.

Inlaid map in San Francisco Airport (SFO), International Terminal

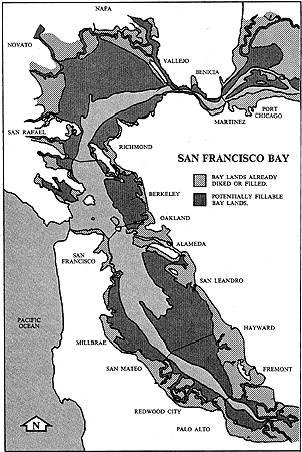

In part, this is due to the pronouncedly low-lying nature of downtown Oakland and the low density housing of the shoreline. It also reflects how the shoreline–after being reclaimed from marshland–was rebuilt after World War II, when the shoreline of Oakland was substantially rebuilt and emerged as a center of industry. That industrial shoreline is now fading. But the distinct social topography it created transformed (and transmogrified) reflect the ecotonal aspects of the bay’s shore from San Jose to Richmond that have not been explored: the transformation of the bayshore into the site of hazardous waste extended to recent times, when the reclaiming of the coastal shore became a major project of civic attention in the Bay Area–far after the projects of saving the Bay itself. While running the risk of being too map-obsessed–a challenge, I admit, that is hard to avoid on this blog–the shaping of the shores of the bay can be traced through the avoidance of the bay, a region of intense sociability in pre-Anglo California that is only being slowly returned to in recent years.

The trend of flight from the shores was solidified by the concentration of the highest incomes at the greatest remove from the shorelines that were associated with commerce and shipping–the peninsula–the deepest red of the region, and the similar remove of the Piedmont and Oakland hills, as if to reflect the wonders of automotive transportation that allowed the wealthiest to live at the greatest remove from the urban center. Tiburon be damned: to withdraw to lofty peaks far away from the commerce of the shoreline seems to be the distribution of the most desirable land. (Tiburon, if an outlier to this region, itself stands at such remove from the commercial shorelines of the bay to confirm the trend–Marin City is of course the bit closest to the bay as we know it.) The economic panorama of the Bay Area makes some sense of region’s socioeconomic distribution and settlement that reflects its industrial past, even though that industry–with the exception of some shipping and oil reserves–is less present in the region today. Is this a ghost or a legacy? This mapping makes a sense of the Bay Area’s social topography: it both clearly privileges panorama that peaks afford, but somehow doesn’t like to look directly at the bay around which it lives.

For living along and beside the bay–or beside the water that were the centers of social interaction for its native inhabitants–was historically rejected both because the waters were the sites of refuse and waste, but also as they became the site of trading, industry, naval yards and slaughterhouses in historical San Francisco and Oakland. One can see the same income distribution echoed in the map of those buildings in San Francisco whose residents were recently cleared by legalized evictions, based on the Ellis Act that permits landlords to issue legal eviction notices to the tenants of multi-unit buildings, very few of whom lived–or rented–residences that faced or were even near to the East Bay, as one can see in this less elegant–and far more crowded–real estate map, which shows the less desirable nature of properties from the piers to Mission Bay to Hunter’s Point, and the relative clustering of valued homes from the commercial or industrial shoreline:

Bill Rankin’s elegant geographical donut mapped local incomes in ways that offers a gloss on the odd historic relation to mapping the distribution of incomes around the San Francisco Bay–a neglected area partly defined by landfill–and later residences–but also by proximity to a body of water that was never that desirable an area of residence save at the Pacific side: the low-lying shores of the bay facing Oakland were far more associated with commerce, shipyards, and treacherous waters, whose shoreline in 1905 was less bulked up by landfill and far more polluted. Removed from the hilly topography of the ocean-facing heights. To offer something of a cartographical archeology of how Rankin mapped the distribution of incomes in the Bay Area, one might begin from the Langley map of 1861, when te Western addition grew around docks allowing nautical approaches, more densely inhabited and built than the rockier shoreline of the Ranchos and government lands on the Pacific or Golden Gate, named from Marin’s golden hills as an uninhabited gate to the Bay.

Copyright Rumsey Collection

Copyright Rumsey Collection

The shores of the city’s peninsula was understood around magnetic lines of nautical approach from 1897 from the Rumsey collection, which measured the coastline as a site of disembarkation and arrival, tracing the topography of the coast in ways that reflect the distance of its use from residential regions.

Copyright Rumsey Collection

Copyright Rumsey Collection

Viewing the city in Charles B. Gifford’s 1862 map of the city from Russian Hill, one can see the areas of settlement perched above the harbor that ringed the city, resting as if it was elevated above the smells, fray, and commerce of the shores, with park-goers sitting in the higher grounds far removed from the traffic of ships sailing in the San Francisco Bay.

Bancroft Library, University of California

Bancroft Library, University of California

From the late nineteenth century, the downtown was ringed by zones of forbidden anchorage, suggesting dense traffic of ships at its piers. Shorelines on the city’s eastern half were notoriously dense, outside of the Presidio, the hilly site of the US Reserve, rather than sites of residential housing, to judge by this 1905 US Coastal Survey of the entrance to the Port of San Francisco, in which the eastern half of the city is far more densely built, and its buy shores surrounded by zones of forbidden anchorage of dense water-traffic. Indeed, the aquatic environment seems far more closely attached to the city in this 1905 map, which suggests a close familiarity of the shorelines at a time when the city was far more often approached by ship, rather than by car, and the deeper waters offered easier approach to the protected cove of San Francisco’s Embarcadero piers without risk of running ashore.

Copyright Rumsey Collection

Copyright Rumsey Collection

The prominence of such grey “Forbidden Anchorage” zones–sort of like metered parking–provide a reflection of the populated traffic within the bay’s shore that removed it from desirable residence even if it increased its value. The expansion of areas of port along the Addition up to Potrero Hill created a sparsely populated region of the city as primary port for the region. The flats off of the shore of Oakland, in contrast, suggested a far shallower areas of docking, no doubt less desirable area of living–refuse must have been washed out by tides from the more stagnant urban shores, where ships arrived by the San Antonio River into Oakland’s port.

Copyright Rumsey Collection

Copyright Rumsey Collection

The port of Oakland was beset by fetid shallow waters, and a marshy inland, that would have rarely attracted sites of denser residences, despite its clearly planned plant, and its shoreline featured a prominent silt belt around its shallow muddy shoreline.

The conspicuous “redlining” of neighborhoods near to the shore in Oakland from the 1930s–effectively rendering them less eligible for any financial mortgages or loans that might create neighborhood consolidation or development as a site of residence–created deep divides that have been willfully perpetuated in the city’s current socio-economic landscape, dividing more prosperous Piedmont from African American residents of other areas of the city who could not afford to buy homes there. Practices of redlining divides in neighborhoods that were granted residential refinancing, captured in the below map of the Home Owners Loan Corporation, reflected existing differences, to be sure, but inscribed socioeconomic divides by formalizing them as formal divides in the existing realty market by destroying the possibility of investment for families living in zones dominated by blacks or African American families, defining four grades of property, and encouraging clauses to be written into titles to not sell to non-whites.

Maps as the above graded neighborhoods that merited increased caution to lenders in Yellow, and “infiltration of a lower grade of population,” whereas green areas are “hot-spots” and blue “still good” neighborhoods; red “represent those neighborhoods in which the things that are now taking place in the Yellow neighborhoods have already happened,” were home ownership is rare and poor maintenance results, as well as vandalism typical of the slums they often contain. The area by the water was an area for piers, rather than the elegant Victorian townhouses that lined the substantially higher ground of neighborhoods like Fillmore or Noe Valley, not to mention those elegant multi-room mansions in Pacific Heights, in ways that have migrated into the current social landscape, where the bay is spanned by bridges that define two major traffic arteries.

To what extent has the social topography of the city remained the same? The value of low-lying areas by the shore has not diminished, but the flight of wealthy populations inland has led to concentrations of wealthier communities far inland from the shore–both in San Francisco and, far more pronouncedly, across the Bay. One can see a similar large brown swath of (low-income) water in the San Francisco Bay within the American Community Survey, of which Rankin’s distribution is (to some extent) a forbear: in the recent Survey, the city of San Francisco and Oakland Hills are flush with green, as is Tiburon: there is, however, as if by a perverse computer glitch reflecting county lines, an odd mismapping that extends to the pockets of low incomes in the Tenderloin downtown, and over across the Bay.

The brown-hued bay of course has few human residents or renters, but is somehow the greatest continuous low-income area, even if uninhabited, by a software responding to fixed county lines, despite the extension of San Francisco county to a tiny sliver of the Naval Base airfield, that one sees outside of inner Oakland:

When did the odd division of the San Francisco Bay arise that included a slice of Alameda in its scope?

The area was excluded from the naval airstrips on the northern end of the island, but reflect a line drawn across San Francisco Bay, a triangulation from small rock outcroppings on the Bay drawn from the almost-island “Red Rock,” and still visible in the OSM mapping of the corner of Alameda that enters into San Francisco County’s parsing of the bay, and the resulting odd mapping of Oakland’s boundaries that left it with limited water rights–and Oakland’s harbor or port confined to the area between Alameda and its shoreline. The same low-lying port region–which Henry Kaiser so dramatically expanded as a militarized area, with Point Richmond and Hunter’s Point, during World War II, together with Marin City, and as centers of lower-income housing–transformed the shoreline from an area of wetlands and ecotones to a region of heavy industry. It’s tempting to excavate the maps as a repository of sort of social history of the human relation to the shore across the bay in Oakland, where the port emerged as a site of commerce and industry, as a sort of poorer cousin to the San Francisco piers, remained a second site of the withdrawal of the wealthier populations from the shore. The limited nature of Oakland’s possession of the bay–marked her by the boundaries of the City of Alameda–offer a canvas of the parameters of shoreline commerce along the former San Antonio river.

A somewhat submerged history of the settled bay shore–before the redefinition of the shore as a center of industry that constituted the built periphery of the land–is evident in the layered archeology of the bay’s history in early maps, that offer the possibility of recovering a narrative of the somewhat idiosyncratic bounding of the bay’s shores as the area shifted from a maritime port.

San Francisco Bay extended the county past Treasure Island so that it brushed lightly against the island of Alameda, for some odd reason of territorial jurisdiction, that predates the Flea Market, the naval station at Point Alameda, peculiarly carved out for reasons little to do with military bases, left a sliver of landfill on Alameda cut off from Alameda County, and lying in San Francisco–not the city, but the County, protective of its water and air rights. The Office of the Surveyor of Alameda helped in inscribing a line “southwesterly in a direct line to a point in San Francisco Bay, said point being four and one-half statute miles due southeast of the northwest point of Golden Rock (also known as Red Rock); thence southeasterly in a direct line to the point on which the lighthouse on the most southerly point on Yerba Buena island bears south seventy-two degrees west, four thousand seven hundred feet,” reads the Senate Journal of 1919. And so it still appears, in something of an artifact of geodata, outlived its time as a basis for negotiating shoreline and sea. Already, in the 1859 United States Coast Survey, the unique shelf off the shore of Oakland suggested a narrow point of arrival for larger ships–even if the bay suggested a readiness existed to define the San Francisco bay exactly along the shelf of land that extended just out to the spit of man-made land of the mole that ran out to Red Rock, which were less suitable for sailing.

A few early printed maps preserve traces of the redrawing of the bay shore, and note that region where the water intersects with land and probably also lines of county taxation are drawn around the bays’ islands and shores. The artificial slivering of the island Alameda in the late nineteenth century is echoed long before the building of the Naval Base, in a Leipzig engraving of the early 1890s, an image attributed to James Blick, San Francisco und Umgebung, which illustrated the island of Alameda is mapped as cut by a secant of railroad track at the point, as Alameda bracketed Oakland’s own harbor and port. But there is no clear delineation of the county line, and the shore area seems primarily defined by the railway lines that run along it.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The division of San Francisco Bay postdates the complex settlement of the shores in the East Bay recorded in this openly acknowledged apparent official settlement which evokes a treaty between San Francisco and Oakland. Derived from surveys that Theodore Wagner compiled c. 1894, which George Sandow so eloquently engraved, the comprehensive map of the bay charted the oyster beds that Indians had long cultivated, whose mound of clam shells rose some sixty feet high, barely remembered in Emeryville’s Shellmound Road–and is now home to Best Buy and P.F. Chang’s. The Bayshore area had become, by the late nineteenth century, a site actively contested and divided by prospectors of oysters, which constituted a very important micro-economy of aquaculture for Oakland’s Morgan Oyster corporation, even in the end of the age of its rancho, at a time shortly after when the city’s amalgamation was formalized, until the increasing waste dumped directly into the waters decreased the imported population of bivalves, and led to declines in local sturgeon by 1920. The mosaic of lots of oyster beds were mapped some distance offshore, in ways that reveal the dense interaction between the tidal regions where the Ohlone had earlier lived intimately with, that maps allow one to excavate from the late nineteenth century–when the importation of oysters had led to their widespread cultivation in the relatively shallow waters along much of the coast of the East Bay.

It is eery that the same shores, so long fertile with the shellfish that sustained the Pomo and Ohlone, were later almost filled with landfill, by the mid-twentieth century, and almost so readily sacrificed. It’s humanizing to look back at the shore divided by oyster prospectors, however, and to see a far more permeable divide that existed between water and land. The distribution of shell heaps was in a way a reminder of the close relations between land and water that had earlier existed in the physical geography of the Bay, where a mound of shells near the current Emeryville, built over thousands of years of the harvesting of shellfish from the bay–not oysters, but abalone, mussels, and clams–was a notable part of local topography, extending some three football fields in length, a sacred site of burial in the large estuary and Temescal creek, from which some seven hundred burial sites were removed in the 1920s, which were mined for fertilizer in earlier years, and partially leveled in the 19th century to become the site of a dancing pavilion, before being leveled in 1924. The distribution of such middens extended around the East Bay:

If the shoreline was a permeable region of wetlands circa 1860, the subsequent hardening of the boundary between land and sea had already occurred by the 1920s, when the region was prepared for industrialization–the wetlands and creeks that were so pronouncedly visible in this early state atlas had been paved over and erased with time, as the shoreline was defined as a fixed boundary of trade and its substantial wetlands disappeared and a clearer division between land and water in the region was effectively over time engineered.

An relatively early perspective of the settlement around the Bay’s shores from 1915 that suggests a clearer bathymetric projection of the ocean floors of the bay. The elegant lithograph indicated the emergence of early landfill of the marshlands of Alameda island, situating the deep water channel for entering the San Antonio Creek fully in Alameda county, and placing a county boundary line in the middle of the San Francisco Bay. While it notes significant estuaries in Alameda, the particularly low-lying lands of the East Bay that it depicts at a certain time became the basis for the cartographic fantasy of extending landfill from the shores to increase the amount of land for sale–or for industry–in the Bay Area.

The same map reveals a Bay whose bearings were of course primarily aquatic, marked by islands that offered mariners primary points of orientation, and the waters linked by spidery lines.

Subsequent post-WWII entertainment of the sacrifice of sunsets and the Bay’s open waters reveals the readiness to development of the coastal waters as an industrial zone that emerged shortly after World War II, as the rise of military bases and the industrial port of Oakland was bracketed apart from the regions of Contra Costa or Alameda County inhabited by a wealthier demographic. The proposal for “Lake San Francisco” sacrificed the bay as if it were dispensable: This compelling evocation of the ecological threat of a proposed narrowing bay waters hinged upon the idea of building over a watershed increasingly seen as a dispensable, whose wasteland of refuse an imagined plateaux would replace, built over a Bay that remained quite polluted, but whose waters seemed as if they would be rendered more manageable:

The imagined “highway outlet” for ships alone was cast as a project of land-reclamation, in surprising ways, and seems to have included a surprisingly ecological view of the seven rivers that emptied into the bay as now filling a freshwater lake–and San Francisco Bay being displaced to Baker Beach and the Golden Gate.

The vision compelled collective resistance–long before the civil rights movement–in a wave of ecological awareness that exploited the power of maps for all they were worth to resist the proposed complex of dams, transportation corridors, and landfill that became identified as John Reber’s plan–drafted at wartime, when the local beds of oysters were no doubt no more, and the Bay had become something of a city of industry. Reber vividly imagined the commerce to be created by facilitating shipping lanes on a redrawn shore, purged of estuaries and irregularities, lined with a sequence of piers and docks. If adopted, it would make something of a mockery of the Bay Bridge’s first span, and the eagerness to link the Bay that that Bridge’s celebrated completion seemed to inaugurate back in 1936. The never-completed but almost-adopted fantasy for redesigning the bay as a lake or freshwater region, shared by Marin, Contra Costa County, and Alameda, as well as San Francisco, was based on building multiple barriers in the bay that expunged or limited saltwater from the waters, drawing the sort of imaginary line that seems to have leaped off of an engineer’s drafting table to incorporate Point Richmond, Clark Island, the Albany Bulb and Berkeley Marina with fill that pushed the piers imagined for East Bay ports in the post-war period almost out to Treasure Island, overrunning the Bayshore as if to displace the port and ship locks half-way to San Francisco. Perhaps this was to alter the property-values of the Bay Area, if only to fill the landfill with an infinite supply of workers’ houses at a time when the rapid expansion of shipping was the order of the day, more than the marine environment; and the workers on the Bayshore could be moved into new prefabricated houses that the landfill would support.

Bancroft Library, University of California

John Reber’s 1941 plan for radically restricting the Bay’s waters was never adopted, nor was his notion of creating two artificial lakes of freshwater, divided from the sea by ocean barriers. But the serious contemplation of Reber’s plans and others through 1962–the plans elicited active defense of the Bay as a region for the first time–suggest that the bay was seen, even after the boom of commerce in the 1950s, as little more than a source for some marine traffic that could be effectively built or beaten back to the Bay itself, and imagined as an area to grow new industry.

And Reber and his wife were sufficiently joyous to communicate the expansion of coastal building–a gift to realtors, perhaps, but also a plan of industrial expansion–in the future map they staged for their own family New Year’s Card as a misguidedly optimistic celebration of the acceptance of Reber’s plan for expanding landfill on the Oakland and Berkeley shores, and even to divide the bay into separate freshwater lakes, as if in the hope of recreating two sites of Arcadia in the m “Joyous Map” that both balanced and contrasted with the industry of the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, or along the planned extension of the canal from Alameda and to the new “City of Industry” in South San Francisco near the new airfields: Reber imagined lakes filled with fish, in which moved poetic sailboats, while the big boats of industry were enclosed by a newly reduced San Francisco Bay.

Bancroft Library

Bancroft Library

The “joyous” vision of an industrialized bay was beaten back–in large part by a “Save the Bay” group of East Bay Residents, ancestor of the current Save the Bay that, back in 1961, crystallized, momentarily, priorities of the current San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission. But the image of erecting barriers across the Bay left the image of a sort of aquatic parcellization, as if treating its waters as a built environment, no doubt reflecting the dredging of its waters to allow ships.

Bancroft Library

Bancroft Library

The battle of the fate of the bay was itself waged in maps, cast in terms of competing visions in relation to the shoreline that would be sacrificed, and with it the relation to the water that had been so dramatically rewritten over time, as residents withdrew from the bay around Oakland, even as they valued the beach at Alameda as a sole point of contact with the sea. What of that odd divide of Alameda County and San Francisco County that persisted, and would be defined by a Trans-Bay Barrier in the above Savage Plan of 1962? This detail of the map, a telling boundary of the San Francisco Bay, seems to be a holdover of the vision of proposed barriers to the bay. The landfill on which the Naval Supply Center, Army Terminus and Naval Air Station lie had indeed gained new prominence after World War II in defining the areas topography. But San Francisco County defined the Bay, and that slim corner of Alameda, drawn here as if at the convenience of a surveyor’s line that ran from Red Rock, sliced a sliver off of Alameda County, almost as if foretelling the later line of the toll-crossing on the Bay Bridge. But the line itself seems not only fortuitous in placement, but contingent of a redrawing of the bay, perhaps reflecting the vagaries of lines of marine jurisdiction, to judge from the bay’s rendering in this section of the 1915 map, in which Red Rock fails to appear, or have the boundary line function that it later would: and one can see public lines of transit that linked Oakland to the Key line on the San Francisco-Oakland terminal and to its own deepwater channel.

Indeed, the dirtiness and disdain for the Bay’s waters seems to have led it to be regarded as something like an expansive parking lot in the years around Reber’s plan, to be sacrificed for the expansion of automobile-friendly space, as is evident in this plan for a “Southern Passage,” never built, but evoking the imagined “Northwest Passage” of the Hudson Bay Company, that would guide traffic in two places across the bay, that was repeatedly entertained from the 1950s, which treated the bay as something of an extension of the city of San Francisco, bridging Alameda and an offshoot of the 101.

Returning again to the bayshore as it was shown in the elegant Wagner-Sandow map, waters on the coasts of Richmond and San Pablo were similarly clustered with oyster beds, a micro-economy at the Rancho San Pablo. The history of the lots of oyster-beds in the East Bay may be even more forgotten, but their mapping seems to unveil a lost tie to the ecology of the estuaries and shallow waters that blessed the region, making it a popular site of native congregation, just before the industrialization of Point Richmond’s or Oakland’s shore.

The once-living shorelines remembered in the lithographic engraving show a lost site of commerce, but of sociability, one determined and experienced by the rising and the falling of the tides, in ways that captured a knowledge of landscape we no longer share, but from which the money, flying from commerce and industry, seems to have fled, until the shore might be restored to not only a habitat for birds, but something more than the washing up of detritus along its sandy shores that not only existed before the 1972 Clean Water Act ended the dumping of refuse directly into its waters.

The overlapping of the waters and lands in the bay was, however, recuperated at a time shortly after the enacting of the 1972 Clean Water Act, an attempt to rid the Bay of the waste that was directly pumped into its waters–without any treatment plants. The attempt to revision the ecotonal intersection of the region seems something of a rehabilitation of its shoreline, if the abandoned stretches of shores persisted in Point Richmond and in the Emeryville Mud Flats seen from the highways.

But the way that public transit system of the Bay Area bridges land and sea is, to an extent, commemorated in the simple “BA” logo of the seventies, whose “B” and “A” interlock and overlap in something like a bold rounded font, whose overlap, as if a Venn Diagram, is a cognitive bridging of land and water on the edges where land and water so gracefully intersect–the ecotones of the Bay Area that the Rapid Transit can bridge. The iconic lexeme maps the region, if in abstractly oversimplified form, indicating the ecotonal mix by the smooth font of the registered trademark and copyrighted logo–although it erases the far more complex history of negotiations with the shores we have lost. But the environmental optimism it expresses of public transportation across the bay link the regions in something like a neat resolution of the final rejection of plans for more building around the bay.

Several of the above maps shown open an area of the muddy shoreline, although that shoreline still seems a barrier for the city’s own far less fluid income divides.

This post was begun before seeing the successful “Above and Below: Stories from Our Changing Bay” at Oakland’s Museum of California, but was revised and expanded with its benefit.