4. The grimly menacing image of a a dangerous seismic threat stands in sharp contrast to the cornucopia of habitats and biodiversity of a city like San Francisco sustains. The power of the image of devastation asks incredulously how San Francisco has allowed the construction of large downtown buildings on such shaky terrain, as if the lessons of the past weren’t ever learned, lest the fears of fault-lines be forgotten, and the dangers of devastation that led to longstanding opposition to skyscrapers that have rampantly transformed New York City’s skyline be introduced.

The image seen from the airplane, as it were, and off the ground, cast this change as local–or the charge of a local New York Times correspondent who arrived in San Francisco–is a projection of the parochial. But is this elevated perspective on verticality also missing the point of what’s on the ground? To be sure, changes in urban skylines are nothing if not global, and the concession to building of skyline allowed the risk posed by underground fault-lines to be forgotten by the extent to which realtors have persuaded the San Francisco Department of Building Inspection to undertake a building boom despite seismic risk. The disturbing fantasia of the city destroyed by nature is no doubt an echo of the increased natural risks posed by climate change, risks of sea-level rise, and surging seas. The unharmonious relation to a world out of joint seems brilliantly condensed in the nightmarish image of urban apocalypse, echoing the struggles for global survival in early 1970s flicks like Earthquake! or 1998’s Armageddon, the benefits of cultivating a harmonious relation to nature, in response to the distance from nature in the shadows high rises cast on litter-strewn paved streets.

William Wordsworth worried about psychically degrading nature on man of the “outrageous stimulation” city-dwellers sought–as if urban life provoked a change in the nervous constitution. A better example of the stimulation of the urban imaginary cannot be found than in the transformation of the skyline by vertical building,–even if the creation of urban canyons wasn’t what Wordsworth meant–the fear that a quest for excesses of sensory stimulation would fail to meet an “inborn inextinguishable thirst/Of rural scenes,” the question of how to compensate the losses that Wordsworth saw as the primary casualties of the build environment has found a new source of nourishment.

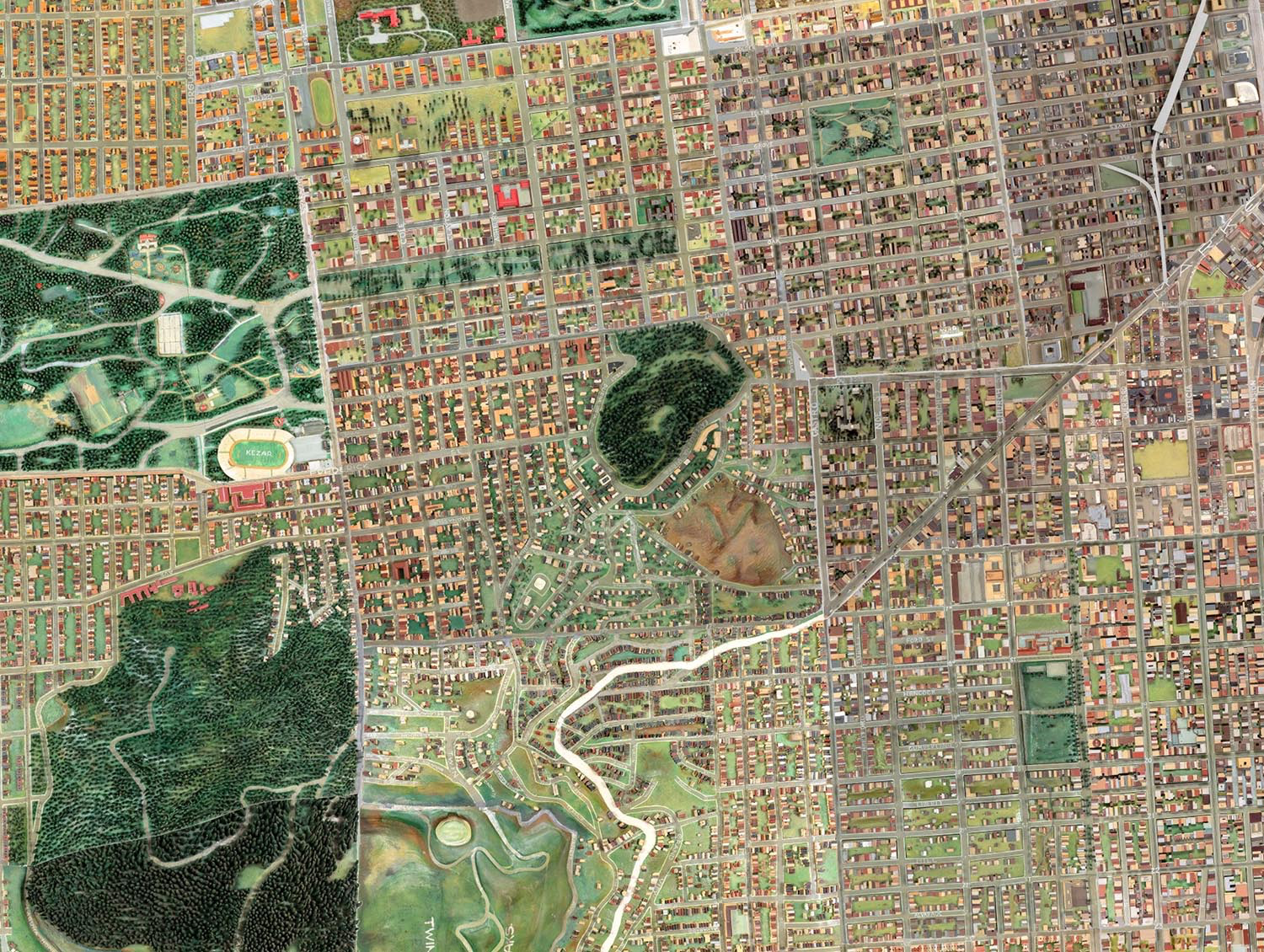

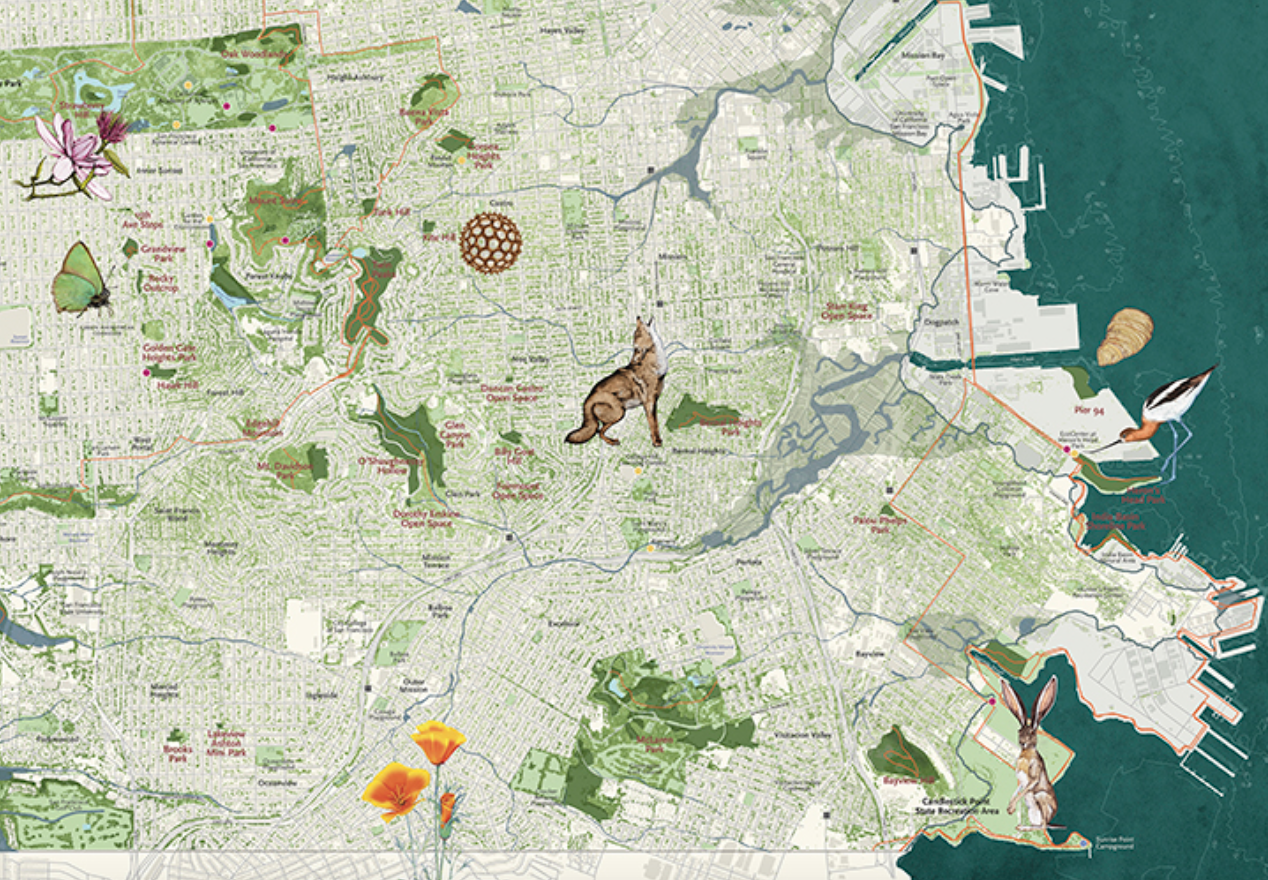

For the marriage of art and cartography to which Nature in the City aspires in its recent map of San Francisco seeks to register the unique combination of natures that we often can lose sight of in San Francisco, or may be in danger of missing. This includes lush parks contain live oaks, man-made lakes, sprawling botanical gardens, and mountainous natural preserves, which the fold-out map seeks to integrate in its mosaic of green. In ways that still pop out at the viewer, even in a static form, the ambitious 2-D project pushes against our addiction to phones and handheld navigation, to orient us to a space filled in of a green urban environment. The image that the fold-out map involves the viewer seeks to put you in a new space of the city, by cutting-edge LiDAR technologies. For if it mediates modern technologies measuring tree density and canopy height, it captures a space that recasts the paved landscapes as something more like a living habitat–rather than the potted plants that Gass described most city-dwellers as spectators, or urban zoos where we watch great cats from behind bars that confirm their remove from a living habitat.

Indeed, by putting nature into a place that you can be a part of, the animals or wildlife that dot the map suggest a direct access to a space that you can be a part of, and an existing set of habitats that you can understand, as a sort of effort of public science that draws awareness to the past shorelines of the city–as the 1854 map that registered the triumph of building out landfill areas for streets, earlier in this post, but by involving viewers in the importance of preserving greenspace, and inhabiting it as well. If the map invites us to explore the city as an environment that is not built, but that holds habitat, it seeks to engage us to encourage the habitat growth that sustains what animal life remains, and its obverse helps us understand the critical ways in which city-dwellers can best engage in doing so, as well as better know their world.

For by asking observers to place themselves in relation to nature in the city, more than observe the residents of greenspaces, readers of the map are asked to help build them and the better to experience and to enjoy them–to notice them in ways that makes this a truly participatory map, able to generate a rich interface of its own and instill a sense of participation in a range of urban habitat, and possibilities of future habitat protection, nourishment, and growth.

Even by placing this image of nature within the urban setting, against an image of the historical shoreline of a city whose modernization accommodated piers along its bay-facing waterfront, dramatically extended by landfill, it invites viewer to immerse themselves in the city as a non-built space, either by peeling back the earlier contours of its coast, as if to bring the nature of the city back into balance with its built space, or by focussing on the green spaces that exist, and the habitat corridors that Nature in the City helps reinforce. The map raises questions about the ethics of mapping place, and ethical roles a map–even a textured paper map!–can still have by replicating an immersive experience of its own, in your hands, that you can use to engage the actual city and urban life around.

Or could it be that the paper map provides the best alternative for examining the role of parks, green spaces and open spaces in the city, and allowing visitors and local residents to reorient themselves to space on the ground, incorporating but displacing the omnipresence of screens as orientational tools?

The best compliment to the map that one might make is that it invites us to experience that space differently, and engage with its space. Since engaging in such a tactile way means walking, and getting off your phone while walking, a reference to Henry David Thoreau seems particularly apt and indeed needed as much as appropriate, for he is as much as Wordsworth a poetic muse of the project. For the non-profit has worked to create a reflection on the ethics of mapping urban space and reading maps built into navigating and living in urban space in new ways. And the ethics of reading maps is particularly needed today, and the sorts of deliberate and intensive reading that Thoreau championed–as well as attention to a range of natural forms–is demanded by the third edition of the paper map, whose text, content, and style were deliberated by a team over a long gestation period lasting multiple years–in which the text, as much as the map, which I have been perhaps wrong and remiss not to engage more fully, is as important as its imagery, but whose imagery compels one to engagement in an even deeper, more sensory way.

For the anti-web or -handheld map is a new sort of handheld, one that invites observers to attend to the rich range of non-human elements most often excluded from how we map the built urban environment–trees, birds, animals, and insects. It grants visibility to what we wrongly see as fleeting residents of incidental presence, granting them greater visibility by foregrounding habitats and tree cover, and uncovering corridors that raise questions about the livability of urban space. As much as getting us to look at the overlooked, it asks we attend to the inhabitants who are in fact the longer term residents of the region, even if we now rarely attend to their presence in our obsession with built space.

For the richly pictorial map that inspires a tactile intensity encourages the intensive observation of the world in its saturation with local detail, looking further into neighborhoods like the Castro and Noe Valley, not as residences for real estate, as seen on Zillow, or the crime maps of urban life that we see at times in a pockmarked view of the Financial District, Chinatown or the Outer Sunset, but as an accumulation of the rewards of stead attention to the lived inhabitants that we too often forget in driving through urban space, mediating a truly scientific picture of who else lives in our urban space, and showing why we want to keep them there.

And if few are reluctant to go car-free, and navigate space with a similar level of intent, the map encourages a different way of experiencing urban nature–indeed, it frames one, putting it into a space you can look at so that you can go back, recursively, and return to the original actual site with a renewed sense of purpose and engagement. It asks you to develop a way of engaging with the inhabited nature of the city, or the nature inhabiting the city, in ways that you want to find, or teaches you some of the ways that you might develop skills worth appreciating to do so. In this sense, it is a reparation for environmental dysphoria, and a break form handhelds, even from iNaturalist surveys of nature in urban life.

5. The dangerous vulnerability of cities has paralleled an attempt to try to take better stock of urban space than the map servers we use provide. For as any server only foregrounds a selective level of local detail, replicating a dominant focus on roads, paved spaces, and buildings, to the exclusion of the constricted habitat that remains on the edges of a city’s built space?

The historical attempt to design a wooden model encompassing a “Huge San Francisco” in detail, back in the 1930s’ era of public mapping and public art, to preserve a record of the lived city in a set of interlocking 3D pieces that served as a snapshot of the lived city suggests just how much of the city was long green and open to “natural space” in a way that contrasts sharply with the image of the changing built environment of the city to give us pause–

–and to take stock of the natures of San Francisco, and the benefits of different forms of mapping its urban environment in less melancholy ways, and indeed of the importance of taking new stock of a city’s remaining open space–or what that open space is, and how we might best interact with greenspace remaining in the city, and the importance of how we map the urban spaces we live.

While San Francisco was long a center for nature preservation, and indeed the preservation of the country in the city, as the perceptive Bay Area geographer Richard Walker put it so eloquently, the organization of tools to uncover and preserve the current relation between ecological niches, natural environments and the built city becomes the project of the recent Nature in the City map, now in its third edition, offers the symbolic tools built on data to explore the urban environment–absent in most street maps or apps that we use to navigate the city, and to revalue the critical importance of native habitat in the open spaces existing within the city’s built environment, and offers an engaging and timely injunction to attend to and help cultivate its inhabited spaces for the future.

The suggestion of the city’s integration with not only its bay and shoreline, here shown as a thin strip of brown that borders on the Pacific, tied to historic estuaries, rivers, creeks, and current parks, presents an image of the city as an integrated whole, in which the blocks and streets foregrounded in GoogleMaps are far less prominent than the deeper continuities that create unique habitats, which are finally presented to the reader. We don’t see the Great Highway, for example, but the sand dollars and , and in Hunters Point find oysters and shorebirds–and in place of navigating a grid of grey, explore a region of butterflies, poppies, and jackrabbits, as well as a coyote, and even, out in the Pacific, the image–in the selection below just a glimpse–of a whale’s tail. The plentiful creatures within the vivid map, which breaks the barrier between cartography and art, reveals a far more engaging, and ethically challenging, question of what it is to map a city and to attend to the built space of a city as a place.

6. The map seeks us to experience place in ways by walking about it, in ways that makes a reference to Thoreau seems particularly appropriate, as the non-profit has worked to create a reflection on the ethics of mapping urban space and reading maps. The more modern problem it addresses–in spite of its static form–raises questions about the ethics of reading maps is particularly needed today. And as such it echoes not the old drawn map, or the web map, but the sorts of deliberate and intensive reading and attention to nature that Thoreau championed–as well as attention to a range of natural forms–is demanded by the third edition of the paper map, whose text, content, and style were deliberated by a team over several years. The non-human elements most often excluded from the built urban environment as transient and fleeting residents–trees, birds, animals, and insects–consciously gained amazing visibility by foregrounding habitats and tree cover, uncovering corridors that raise questions about the livability of urban space–even if we rarely attend to them.

Even if the map is printed surface of two dimensions, it encourages the intensive observation of the world that its degree of local detail arranged on its surface, from its depictions of lost streams and watersheds, arboreal density, hidden lakes, and islands of urban forest. Its significant harvest of point-based data that serve as the base-map for attending to lived space that we too often overlook, and do so at our own risk.

For rather than compile a survey of the built environment, and orient the river to streets, main highways and the neighborhoods we give to urban space, the static map offers an engaging relation to the habitability of a city so often bemoaned as increasingly unhabitable due to skyrocketing rents, gentrification, and evictions.

The quite distinct base-map that folks at Nature in the City organization adopted to invite us to view San Francisco helps to shift that set of associations, and to open up hidden spaces within the city to viewers in ways they might never have had access, putting the place of San Francisco as a part of the thin line of green coast and as a potentially rich set of open spaces, habitat and green.

The recent revisioning of the greenspaces that distinguish San Francisco displace the rush of commuting and explosion of jobs and rents for which the Bay Area may be increasingly known–

–and effectively invite viewers to navigate, and explore, a city where rents have withdrawn most of our attentions from the lived environment. The base map rich with data sets of the multiple green spaces in the city, from parks to all street trees and gardens, as if they and the surrounding waters afforded a palette–which if pictorial in nature, offers a synthesis of public data on open space.

The benefit of an amazing expansion of the availability of open data, in part specific to San Francisco’s ecosystem and forms of governance, helps situate the existing habitat that the non-profit has dedicated its energies to encourage, inviting viewers–and residents–to shift their attention from the city streets and built spaces to the conscious cultivation of the wild. The result is to re-focus attention on the habitats of specific animals, birds, fish, and plants across its urban space, in a static map that is made for an audience familiar with interactive mapping forms, and the coding of a rich natural space, extending to imagining its lost estuaries, underground rivers and watersheds, and even the historical shorelines of San Francisco before the addition of landfill.

Nature in the City 2018 (detail)

Pingback: The Built World | Musings on Maps