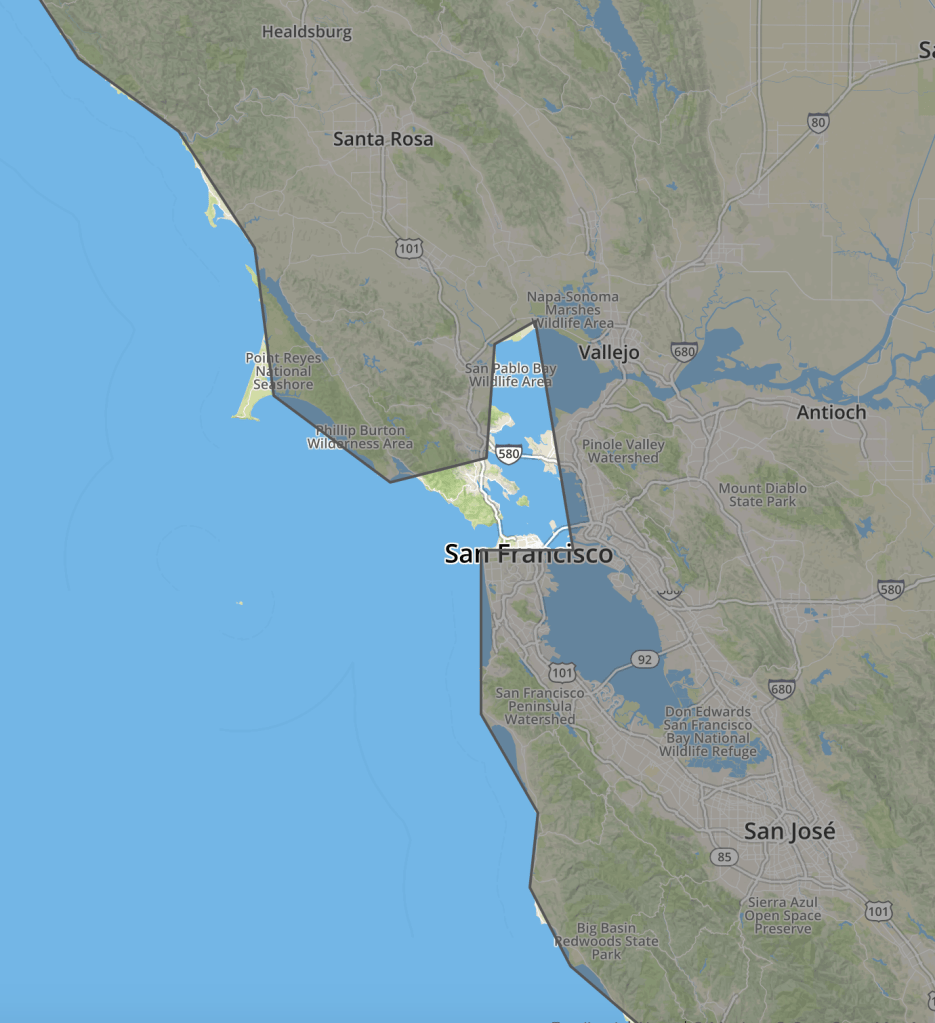

The mappping of kelp beds and sea weed density is challenging remotely, and indeed often doesn’t fit within the polygons we usually use for coastal maps that privilege territory, and allow us to use a point-based mapping tool to cover extent and expanse, as in the most elegant Mapbox formulation of space–

–whose format will depend, as it must, on the use of point-based location data, to describe the contours of land, and property, which often neglect estuaries or the sea, and unfairly compromise the shore that demands more experiential examination than passive sensing, and leads us back to earlier Admiralty Charts, engraved in the mid-nineteenth century, with the explicit end to register the dangers to casting anchor posed by immensity of banks of kelp off the coastline of British Columbia, in an attempt to assay a proper sense of the range of older kelp beds, and even an adequate iconography to map kelp beds in the near offshore.

Even as Darwin’s popular work helped direct increased attention to seaweeds, evolutionary biology encouraged the variety of kelp to be appreciated as a record or vestige of an evolutionary past, and as preserving a historical richness of speciation that was often removed from its generative nature or role. As seaweed became of increased interest form the mid-nineteenth century, as a source of life and as evidence of earlier life forms in their exquisite variety of biomorphic form, resembling an underwater record of the building blocks of life or of prehistoric time, the presence of seaweed bridged a sense of natural history and the material presence of beauty.

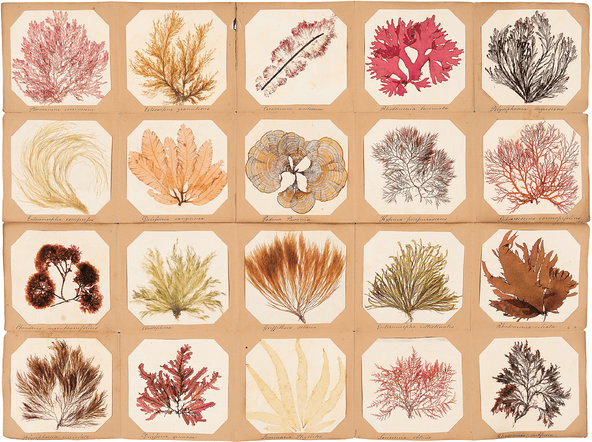

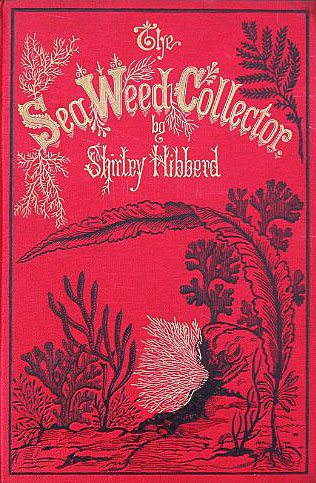

So much is evident in the glorious album of species of seaweeds that sorts some twenty different seaweeds collected in the Channel Islands attests, in a veritable compendium of life-forms and exemplary records of the evolutionary record, bordering on the commodification of the natural and on the appreciation of the handiwork of created forms–often associated with ornament, decoration, and artifice, as much as its vital role in marine population was preserved. The rage of pressing seaweed to illustrate its aesthetic properties, was to an extent emblematized by the Victorian interest in preserving seaweed samples in samplers, removed from their ecosystems, as if preserving a legacy of Darwin’s attention to the speciation of marine environments uprooted from the environments themselves, that still to some extent is a popular legacy of the romanticization of the coast as a site for seaweed observation.

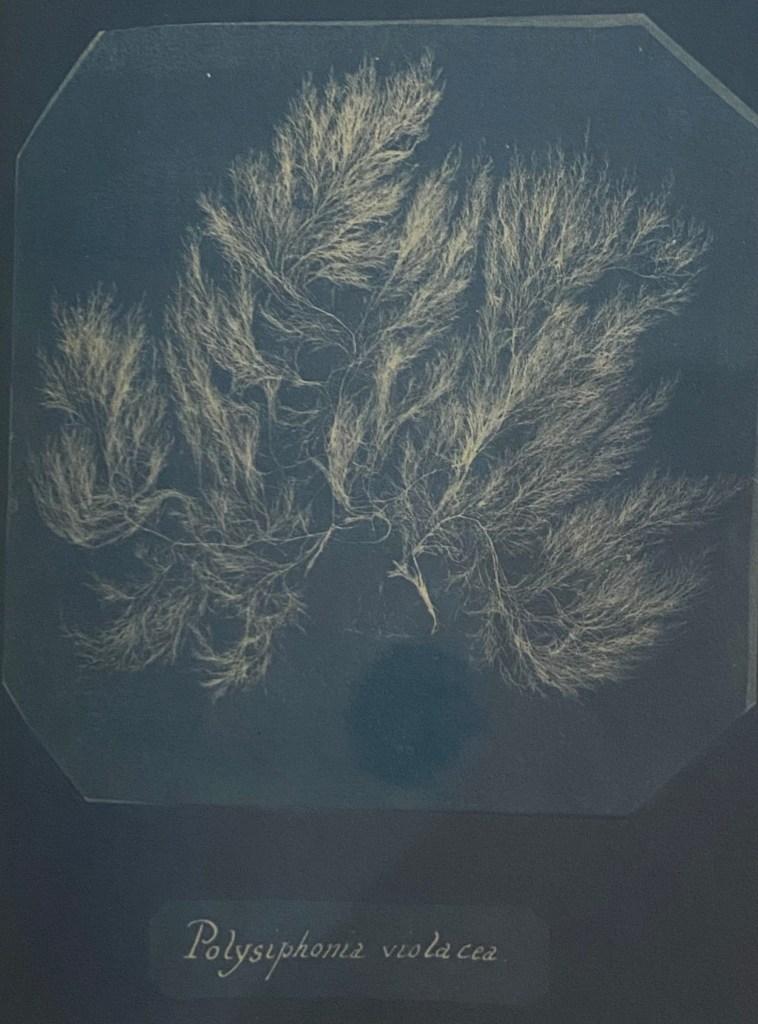

The opportunities of observation within these carefully assembled seaweed collections, however, which provided opportunity to study the infinite variety of nature, evident in the rage for collections of pressed seaweeds–as if in a form of postage stamp collecting, often performed by women and children, in an extension of the pressing of flowers or leaves or ferns into the edges of the underwater world, leading marine macroaglae to be preserved in Port Arthur, Australia, the Cape of Good Hope, and Ireland, as the enterprise of cataloguing their variety for naturalists or phycologists from Ferdinand von Mueller toWilliam Henry Harvey, or Joseph Hooker, of Kew and Carl Agardh of Sweden led to the assembly of large collections of the sea plants that produced not by flowers, but spores, in dignified scrapbooks like Anna Atkins’ s “Photographs of British Algae,” some of the very earliest examples of one-color photographic processes that used marine-like cyan hues of vivid colors we associate with sun-prints to create exquisitely detailed mid-century “prints” of algae as scientific records in elegant cyanotypes of almost etherial effect. Atkins, who worked on sunprints before the invention of the photographic cameras, pioneered the sun-print cyanotype with nearly four hundred prints, printing sets of impressions from 1843-50 of twelve volumes that catalogued the algae on British shores, in the first effort to use photographic images for scientific ends by the cyanotype process invented in 1842: did the effect of illustrating a deep blue sea on paper lend itself to the practice of photograms of underwater seaweed?

Analogous to collections of antiquities, the photograms of seaweed catalogued by scientific name was an early effort of “blueprinting” that promised to allow women to integrate themselves in a respectable scientific enterprise through botany–an area more open to women practitioners, which had lead her to collect and preserve plants from the 1830s, perhaps under the influence of her father’s etymological expertise: the new medium of cyanotype photography allowed her to catalogue the feathery varieties of weed by a scientific manner with which she was familiar as the illustrator of Lamarck’s work on seashells. Was the project of documenting seaweed forms not only more challenging to render in pencil or engraving, but lent itself to a more fitting record of their complexity?

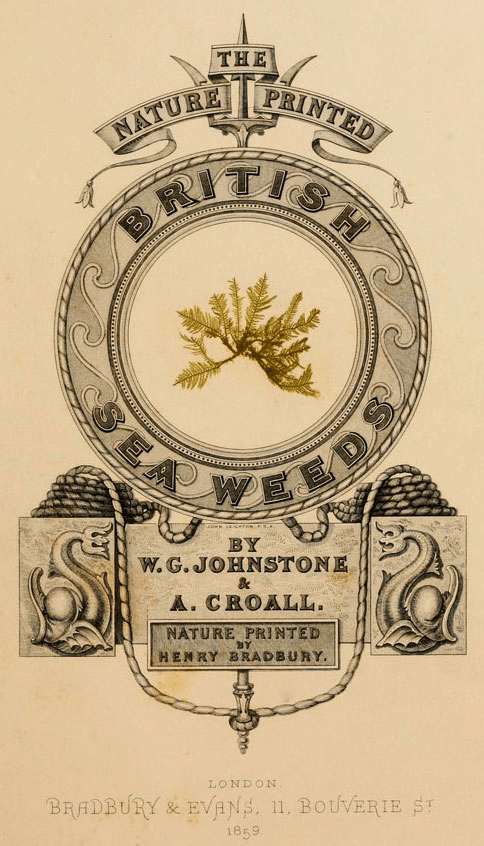

These collections are echoed in Mary Carrington’s careful constructed seaweed samplers, privately reproduced cabinets of curiosity that were the product of beach walks that bridged middle class enterprises of collecting, arts of engraving, from 1859 to 1872. Such albums offered a sort of productive collecting, beneficial natural inquiry, and exotic learning of uncovering the offshore–if the title of Carrington’s elegant book of keepsakes might be misread a radical Bay Area steam punk group dedicated to kelp harvesting.

The deep aeastheticization of the seaweed plant, however, as a sort of aesthetic adventure, suggested a sense of domestication of the underwater, and removal of the algae from any environment, in ways that we are only recently coming to turn away from, in an attempt to better understand the actual underwater scene..