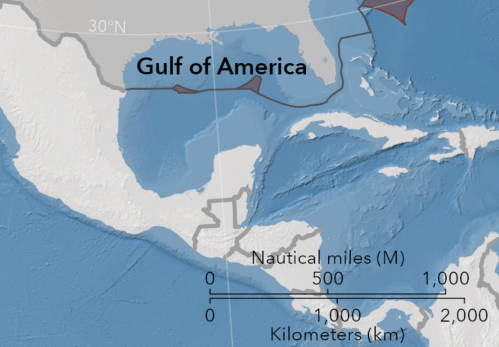

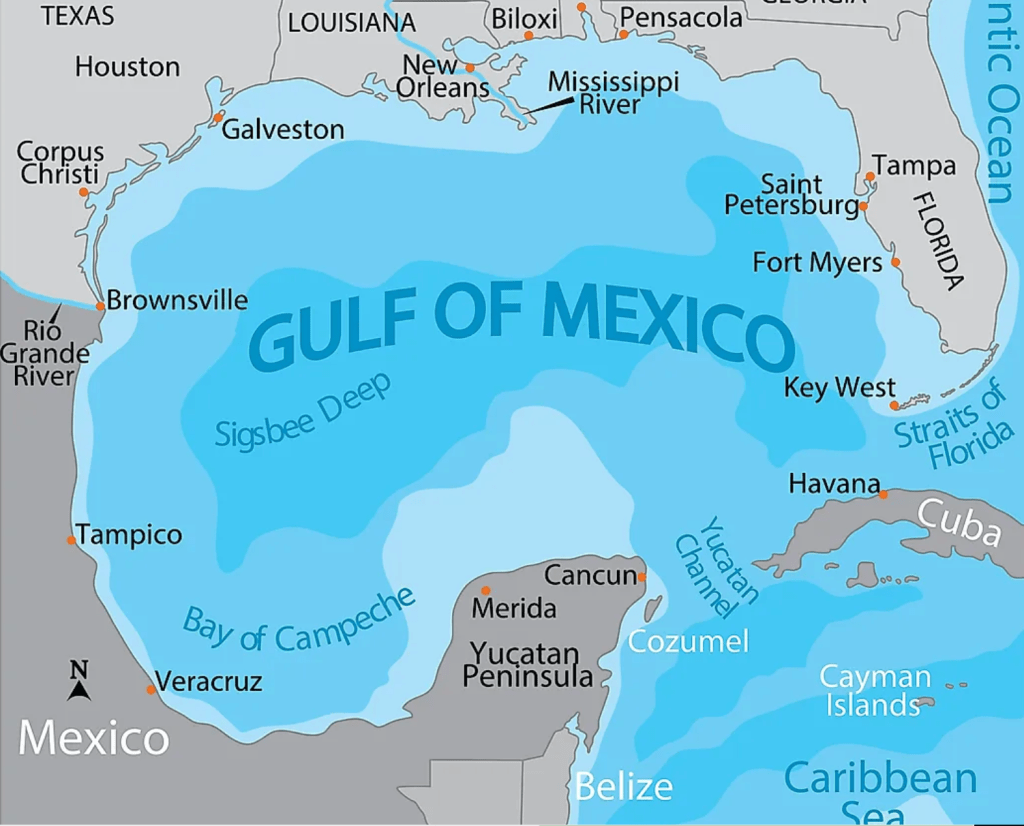

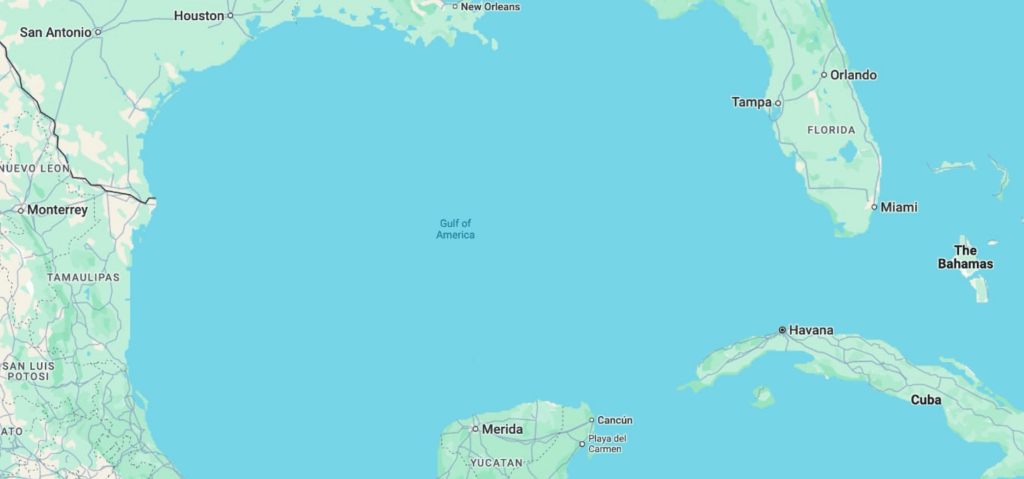

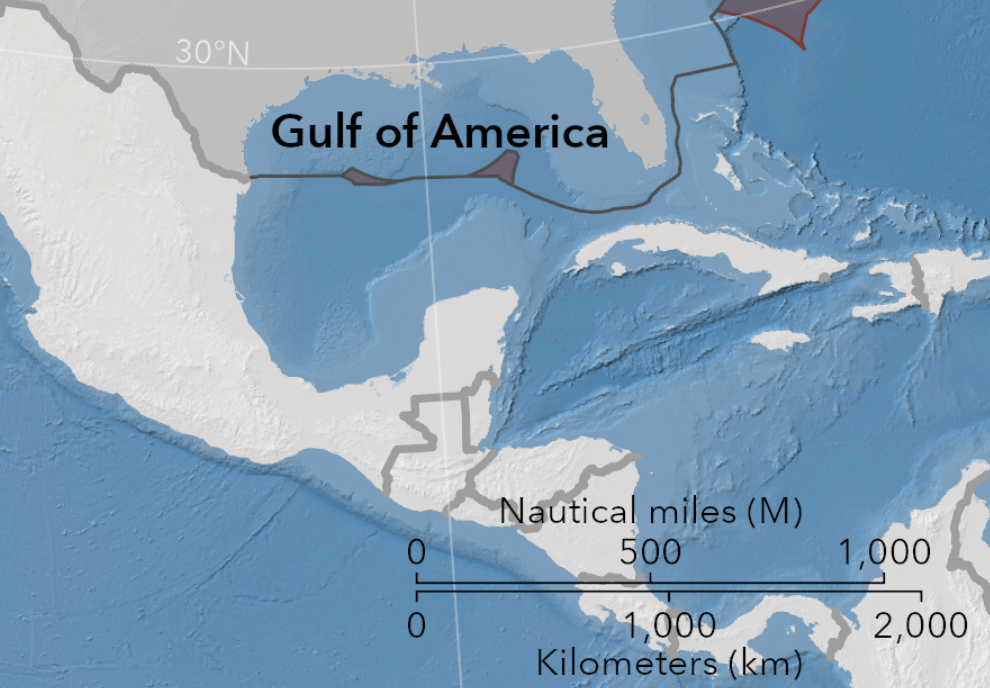

Conquests often lead to a renaming of place, a denial of the rights to land or water by former inhabitants, that is only confirmed by a map. As if sensing the need to administer a national shot of dopamine without much to accomplish for ending war in Ukraine–despite assurances of its imminent ending–or the transformation of Gaza’s rubble to beachfront properties, realizing our short attention spans, President Trump declared victory on the television screens and Google Maps feeds in the relative safety of the Brady Press Room, and declared victory over the maps to be provided Americans in the future of the offshore waters of the southern coast of the United States for the foreseeable future. While the font is shrunken over the deepsea area, the expansive claim to expand far beyond the nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone or the continental shelf is an act of what might seem bravura, but is also of a false patriotism, a patriotic rallying cry that conceals craven catering to the interests of the petrochemical companies to whom Trump’s campaign was indebted, and disguised the hopes to open bids on offshore lots to extract oil and gas in claims of hemispheric dominance. The aim to secure the popularity of his Presidency by lowering gas and oil prices was the rather simplistic hope of jump-starting the American economy, disguised in jingoistic claims that map servers like Google Maps and many news agencies were all too ready to accommodate.

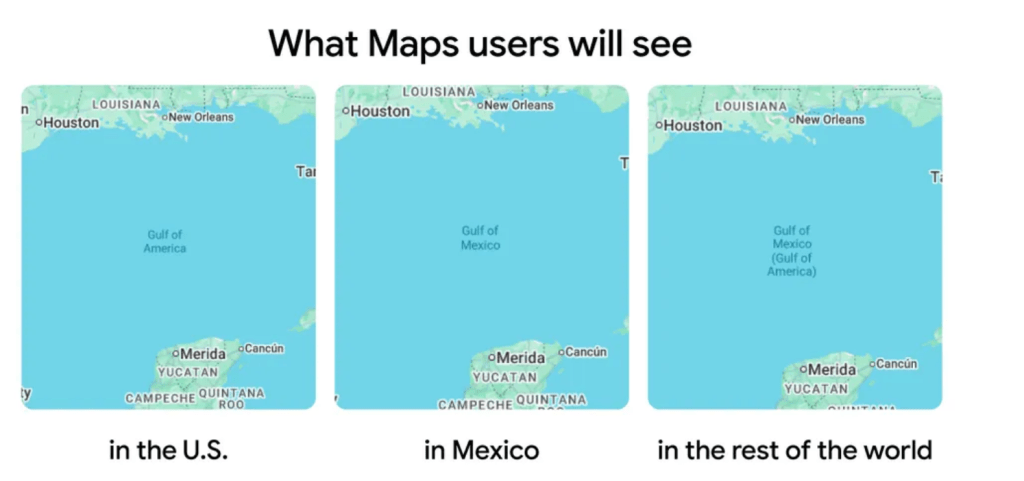

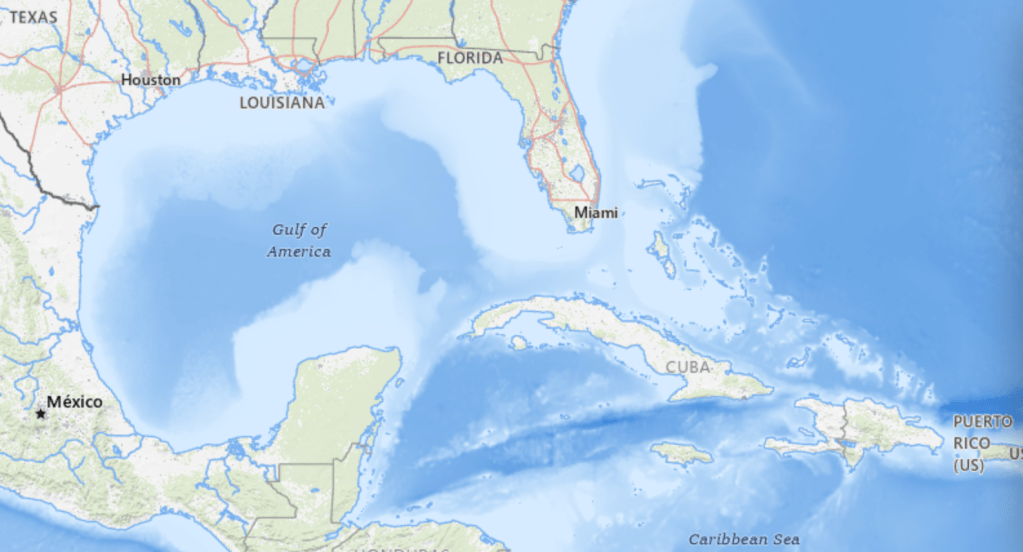

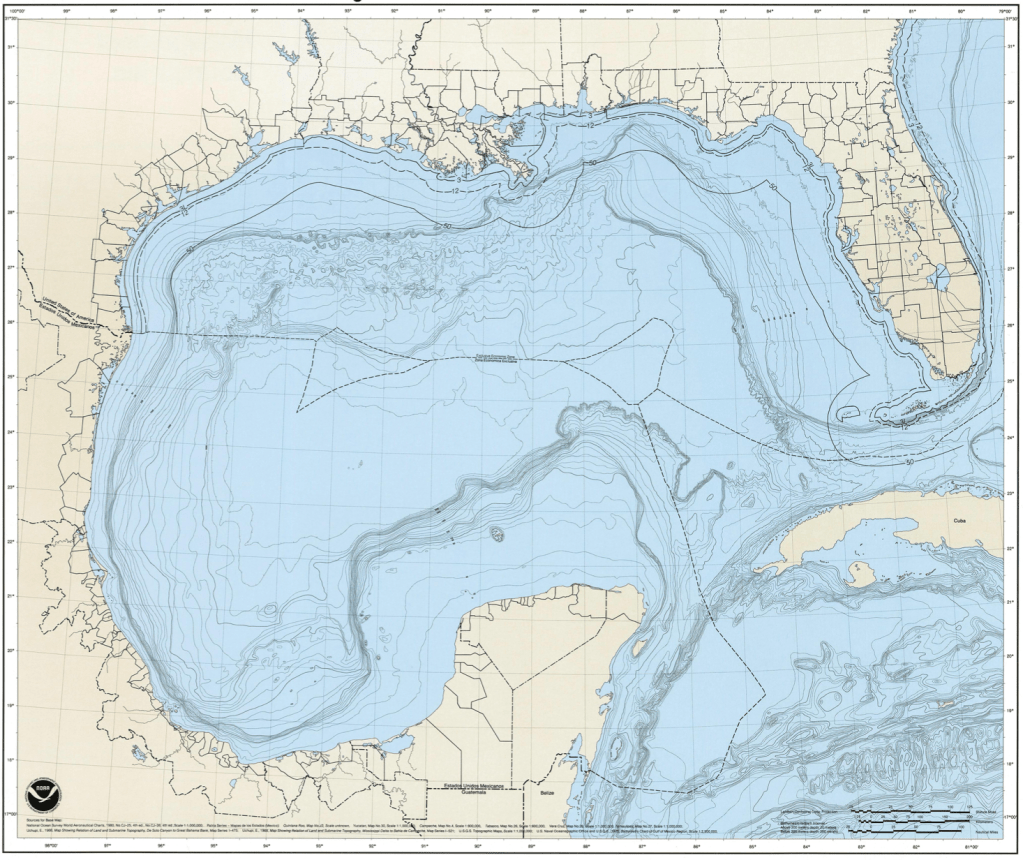

Google Maps

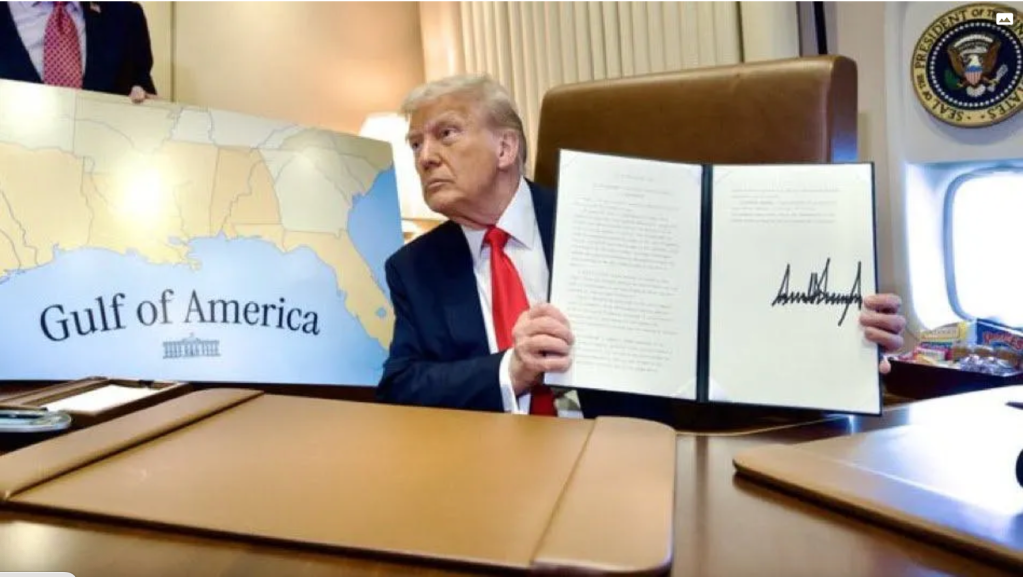

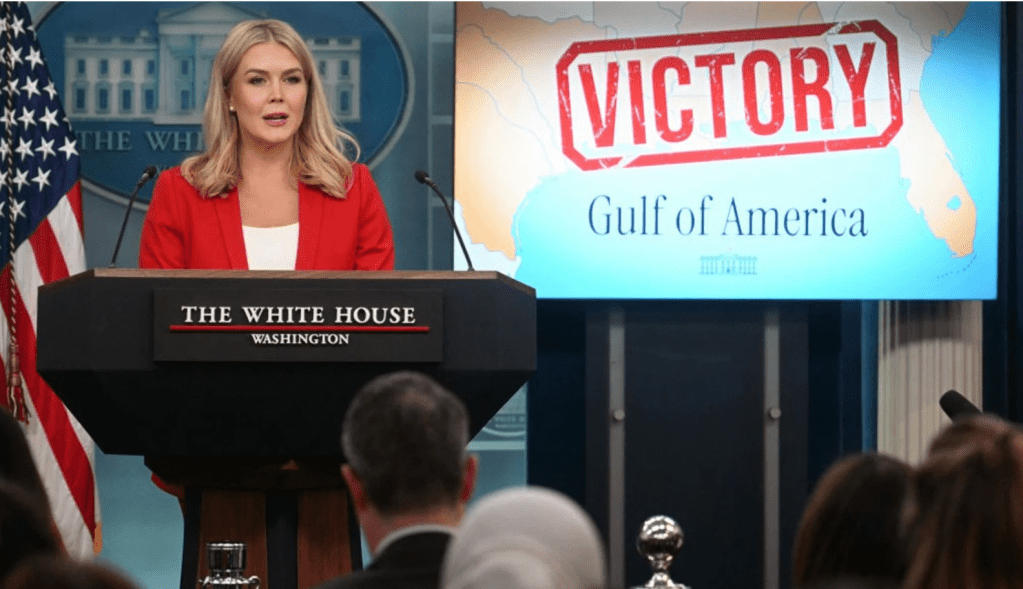

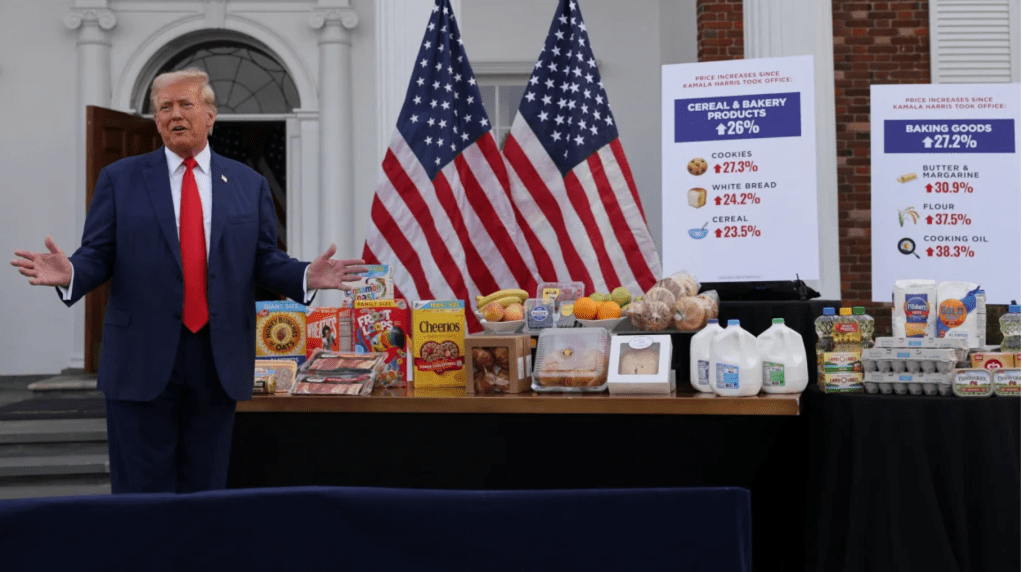

This rather brazen declaration of victory included a cartographic bill of goods and a dictation of the new policies of mapping servers and news agencies not only for the cameras. It was for smart phones and online maps, a stage-managed as a campaign event–which it sort of was. The celebratory display of a banner of victory above twin maps that illustrated a renaming of a body of water asserted its reclaiming for national destiny as a needed shot of endorphins to project victory in the global race. The Gulf of America was no mere outlier, but a gauntlet, expanding the earlier extension of offshore waters beyond the current continental shelf, as Trump moved its line, with great bravado, to erase the name of ‘Mexico’ as if the waters were contested, as the result of a war, if this was a war that never occurred, but was being staged for national news agencies he clearly expected to parrot his alternation of the hemispheric map, and the right to stage a name change.

‘Gulf of America’ seems, in retrospect, the terrain of the series of victory marches Donald Trump had mapped out in anticipation of his return to the Oval Office with an entirely new administration. His full-throated adoption of the terminology in news industries that went off so smoothly–indeed, without a hitch!–left him exultant at quick adoption of the new designation among news media, transformed to a spokesperson and portavoce of his truly dark geopolitical designs. With a new grim perseverance in the face of international blowback, Trump glided obliviously over the question of how international waters were being renamed by a nation on unilateral grounds, concealing most of the grounds he sought to be able to claim–and extract oil and gas–lay in the deepwater reserves that previous American administrations have taken off the lots auctioned to the petrochemical industries, that Trump openly wanted to put back on the table without regulatory oversight.

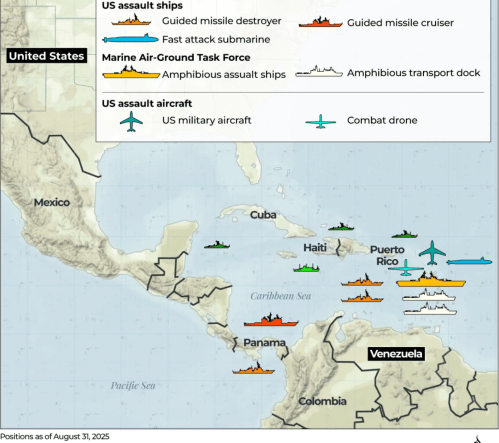

While we didn’t yet imagine that the Gulf of America would be a brand tod be taken on the road to the beaches of Florida–promoted as if it were a “another Trump Development” in its dedicated red, billed cap–the renaming led a rewriting of human rights in international waters, and a new chapter in American unfreedoms rolled out in the Trump regime. But the renaming was a way to push the project to Make American Great Again into international waters, a military patrolling of the expanded waters of America that might be patrolled by drones and bombed at will, if the U.S. military saw something untoward or criminal like a boat that was advancing in international waters suspected of possibly carrying drugs–a criminal but non-capital offense–toward American shores. For the predesignation of a Gulf of America as a part of the map needed to be made Great Again had expanded, as a side-benefit, the area of the nation or ‘national waters’ we needed to defend, because they were suspected of an intent to smuggle drugs across the border–“Every boat that we knock out we save 25,000 American lives”–so that killing three or five or fifteen people wouldn’t be that bad in the calculus where “you lose three people and save 25,000 people,” as Trump clarified, explaining how the elimination of the ships was ‘actually an act of kindness.’

While “Make America Great Again” was mostly understood as a metaphor for the interior, embracing economic issues and global stature, the Gulf of America skirts the boundaries of hemispheric dominance. For the new designation of the largest body of water in the hemisphere literalized the remade greatness of America as a question of magnitudes, embracing a new map of the Expanded Continental Shelf, to be sure planed and mapped by his first administration, from 2017 at the behest of the American Petroleum Institute. The expanded continent served as a way to promote the development of offshore resources of energy extraction, as a cartographic boondoggle that would coincide with the Trump Presidency–and conveniently erase the cartographic history of the negotiation of borders with Mexico, trumping them all by declaring the largest body of water in North America to be a natural extension of American sovereign space. And the new designation of the body of water got rid of a term that, it had to be admitted, predated the birth of the United States, as if this might allow its consignment to the dustbin of history, a relic of the world of a past era that fails to reflect how the United States has remade the world in its image.

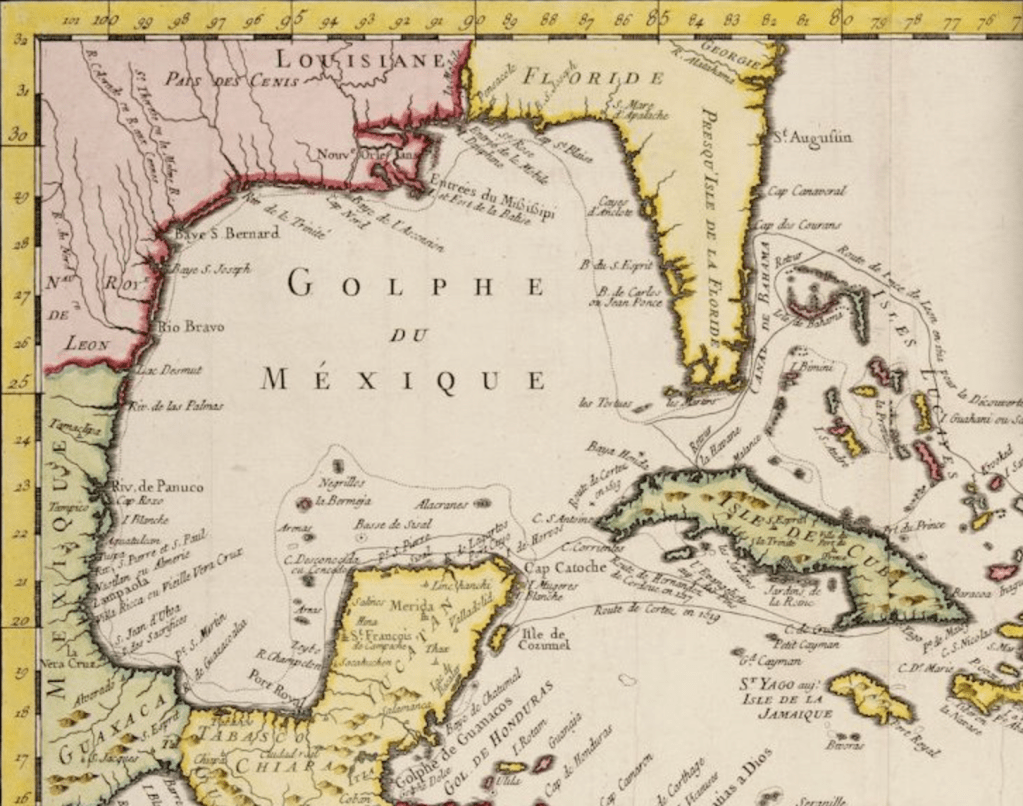

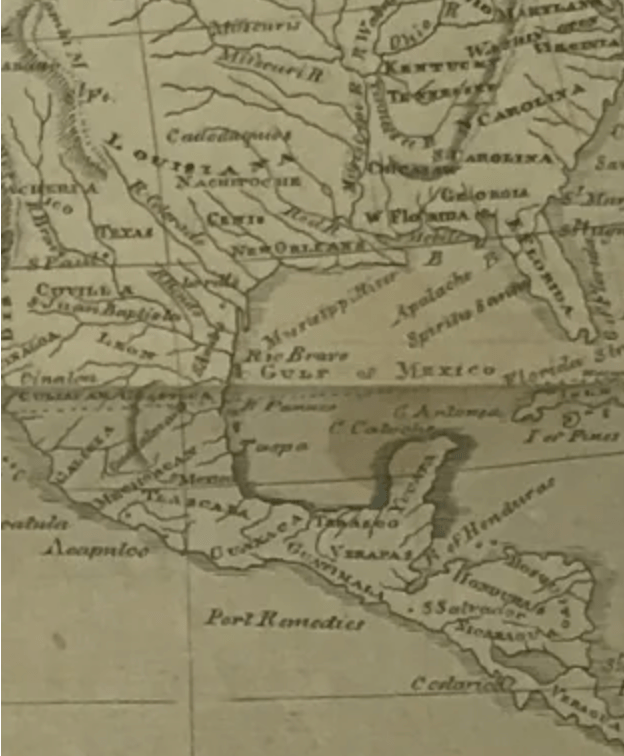

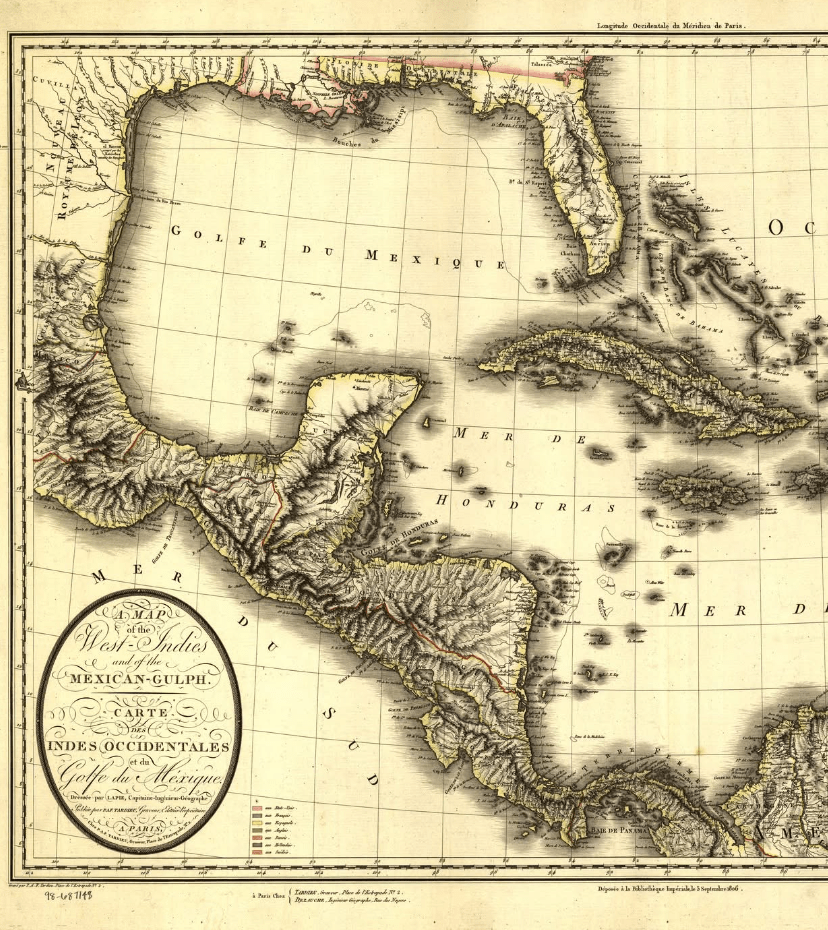

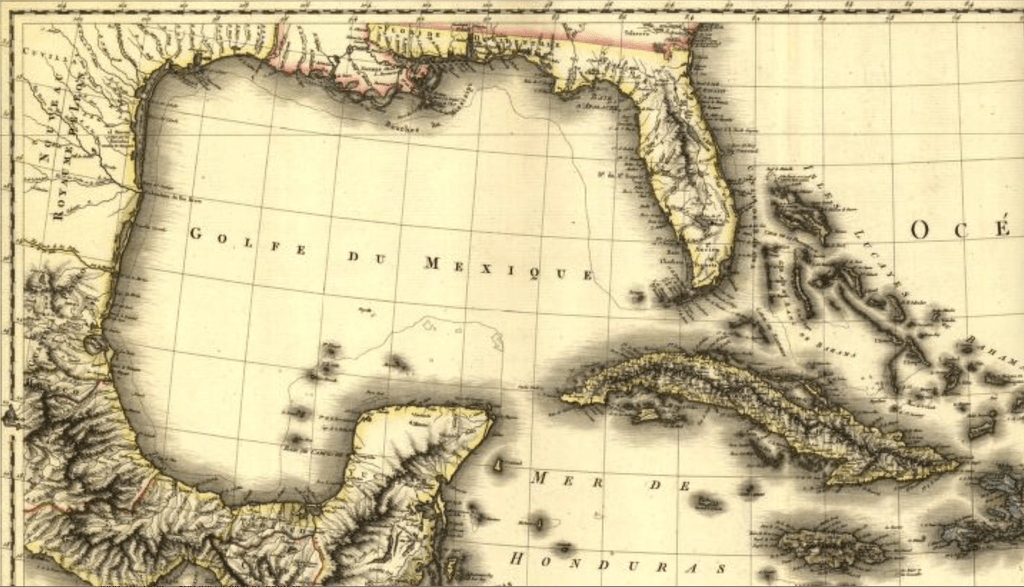

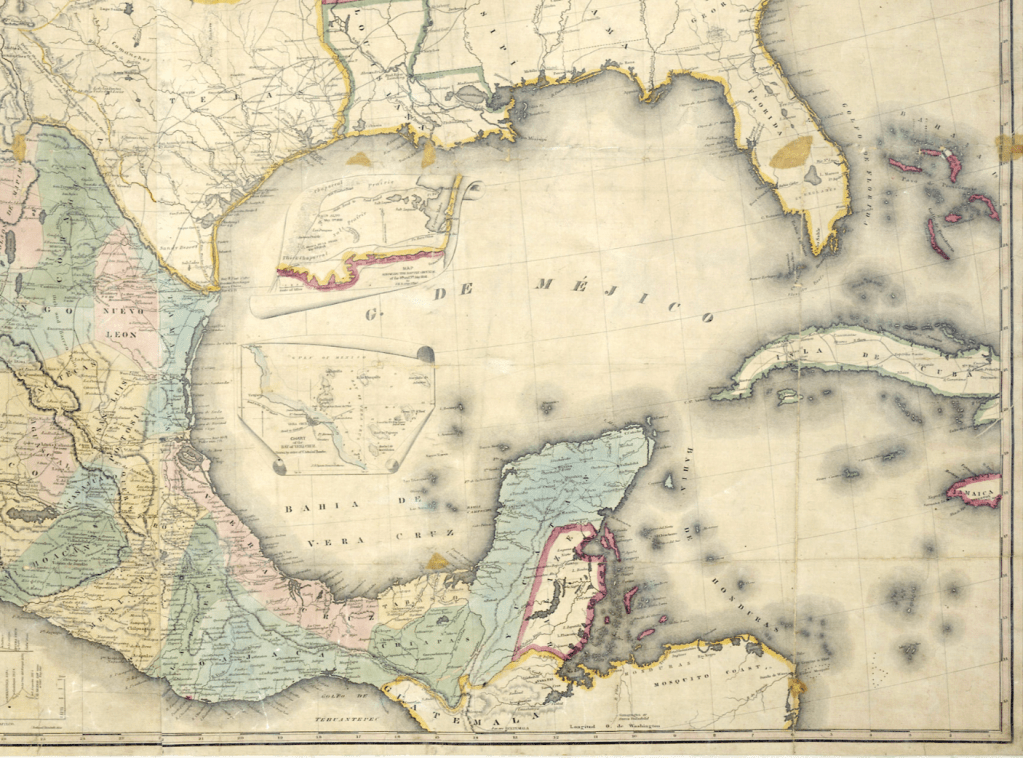

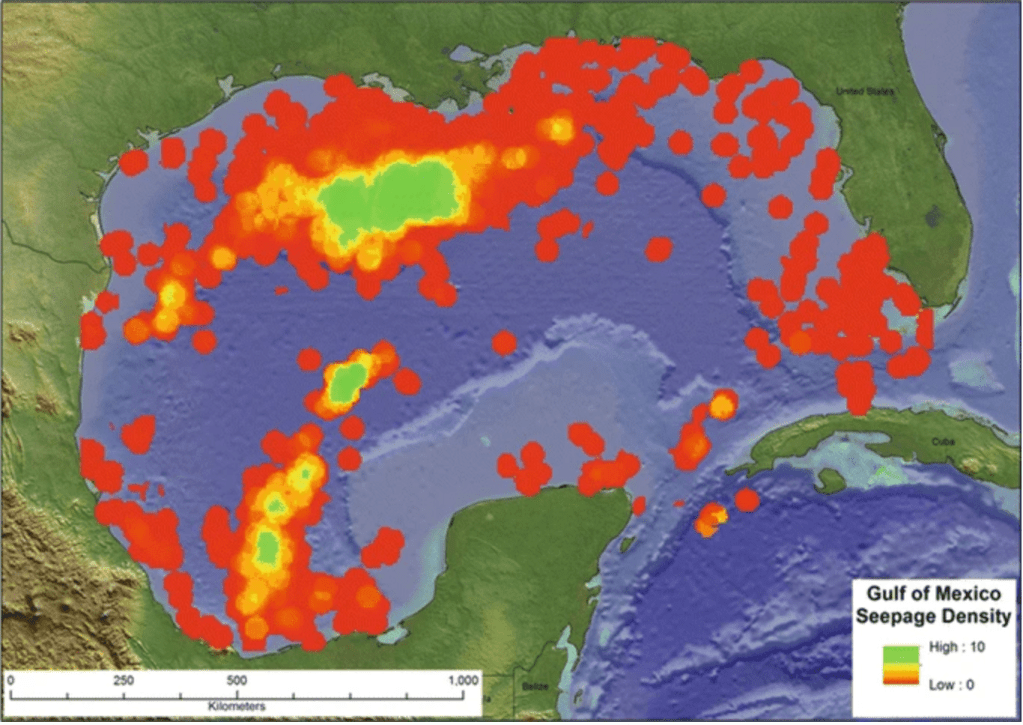

While the earliest authoritative treatise on the New World, compiled by the erudite Johannes de Laet based on the clearing house of the Dutch West Indies Company, described the separation of north from South America, or dividing the Terra Nuova to the north from Brasil to the south, by a gulf shaped like a half moon and filled with islands, like the Mediterranean, as the “Gulf of New Spain or of Mexico,” four hundred years of time seem to be compressed and elided by the renaming of the body of water as a Gulf of America. While the question of sovereignty was a bit up for grabs in De Laet’s day–there was the issue of Spanish sovereignty over the islands and ports, as well as the gold and sugarcane–the Gulf of America is in truth far less as a body of water for maritime travel: the blatant ploy focuses attention on underwater mineral reserves as the new mercantilistic logic of Donald Trump’s MAGA policy. If Spain claimed the gulf in the old mercantilism as a shipping route for precious metals mined in the New World, the new mineral wealth lies off the shore of petrochemical America, in the deep sea, rather than on the shipping routes of the past. If Spain wanted to ensure that the crown profited from mining mineral resource in the colonies, and the extracting of silver by mercury amalgamation and benefitting from the labor of large enslaved populations, allowing the metal of a new coin to be minted from New World silver, the extracting of gas and oil from underseas will demand an even more intensive extraction of oil reserves, by which the United States is increasingly ready to believe might keep its own economy afloat in increasingly unpredictable global energy markets of signifiant cash flow, the environment or biodiversity of the waters of the Gulf be damned–

–not to mention the precarious nature of its long settled shores and benthic coastal habitat.

The Trump Presidency dispenses with legal norms or precedent, seeing what it identifies as “worth it,” and trying to grab it in a desperate race to Make America Great Again by a new mercantilism of expanding the borders of maps, making obsolete the indexical frames as a way to read marine routes that the maps transcribe and organize oceanic space by itineraries in favor of the geolocation of deep sea wells that can be mapped to increase the national wealth by a region whose “bountiful geology” contains “one of the most prodigious oil and gas regions in the world,” already providing a sixty of America’s crude-oil production and whose seafloor contains abundant natural gas, whose opening to unregulated business would drive “new and innovative technologies able “to tap into some of the deepest and richest oil reservoirs in the world.” Renaming of the region was claimed to be merely restoring a body of water to its rightful place in the national map, but the very idea of “restoring” the name to “honor American greatness” was rooted in expanding the underwater reserves beneath it to a reserve of national wealth. And Trump was pleasantly surrrised that the gambit worked, in the sense that even if that name never existed on a map, it was adopted by collective assent on map servers in the first month of 2024. This was mercantilism by putting the cart before the horse, or expanding the map of minimal regulation before the economic business even had begun, outside of any adherence to the complex evolution of ocean regulations, flying into the face of international governance of the oceans by removing the old name from maps as if it were an obsolete inheritance of an old geography–fit for the history of cartography–

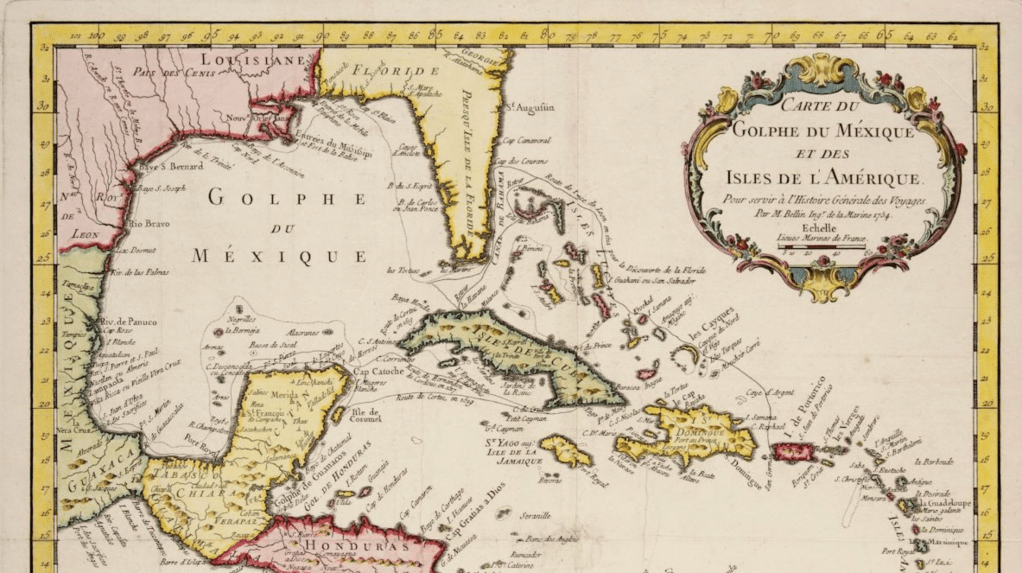

Jacques Nicolas Bellin, Carte Du Golphe Du Mexique et des Isles de L’Amerique (Paris, 1754)

to recognize a new economic reality. To be sure, Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi and Texas were states now, not just areas of land, entitled to sovereign wealth funds in the Gulf that America whose oil deposits United States companies had mined more than any other nation, the states bordering the Gulf, as much as the oil companies that have released the buried wealth.

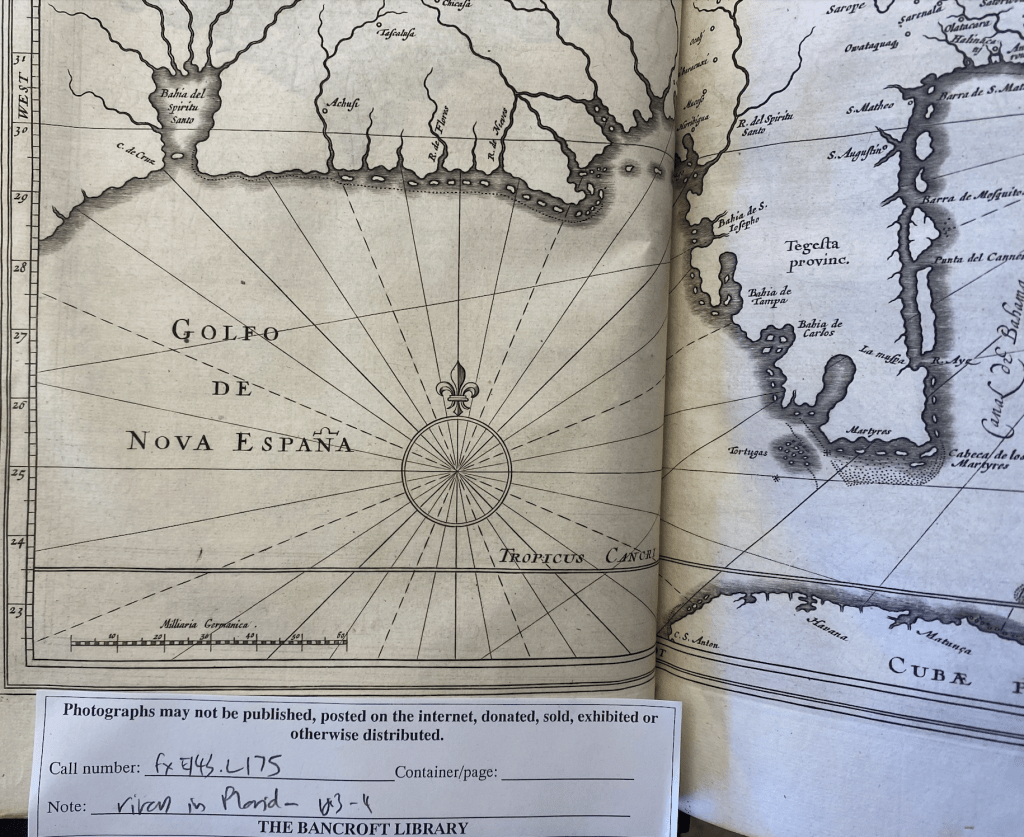

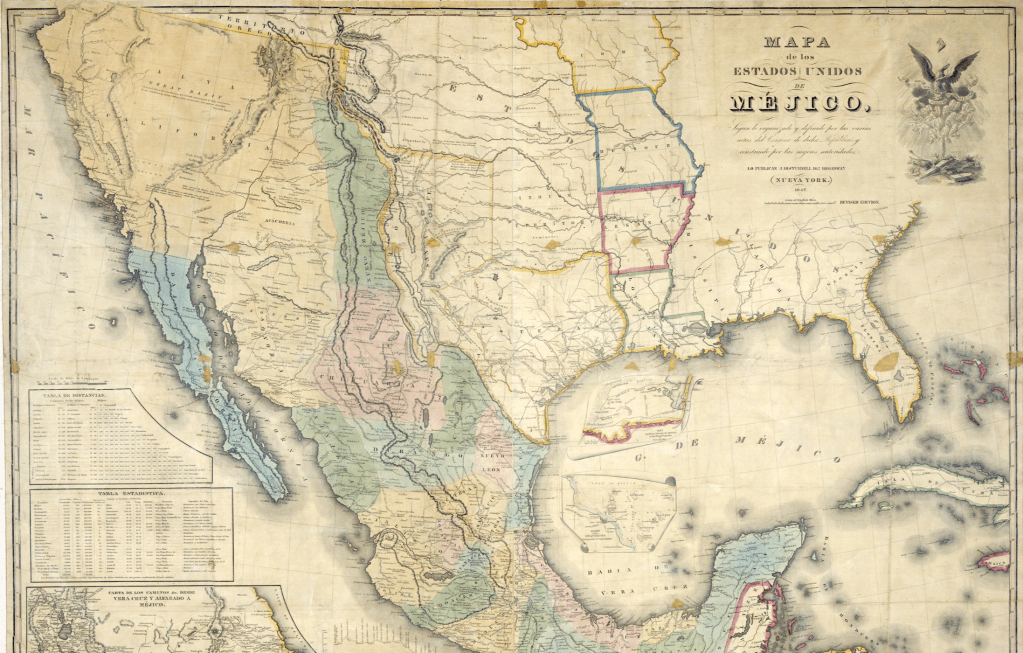

To be sure if one went a bit father back through the centuries, the neo-imperial act of renaming was consonant and of a piece with how the same body of water had been a bit different seen in 1640, when it was mapped as a part of New Spain–when Florida was far more sketchily mapped, indeed, if the rivers that fed what was then simply the “Gulf of New Spain” fed a body of water whose naming reflected the global dynamics of colonization, removed from any sense of local nationhood, as if the mapping of a new body of water were indeed only fit for the projection of national dominion.

Johannes de Laet, Histoire du Nouveau Monde ou Description des Indes Occidentales (1640)

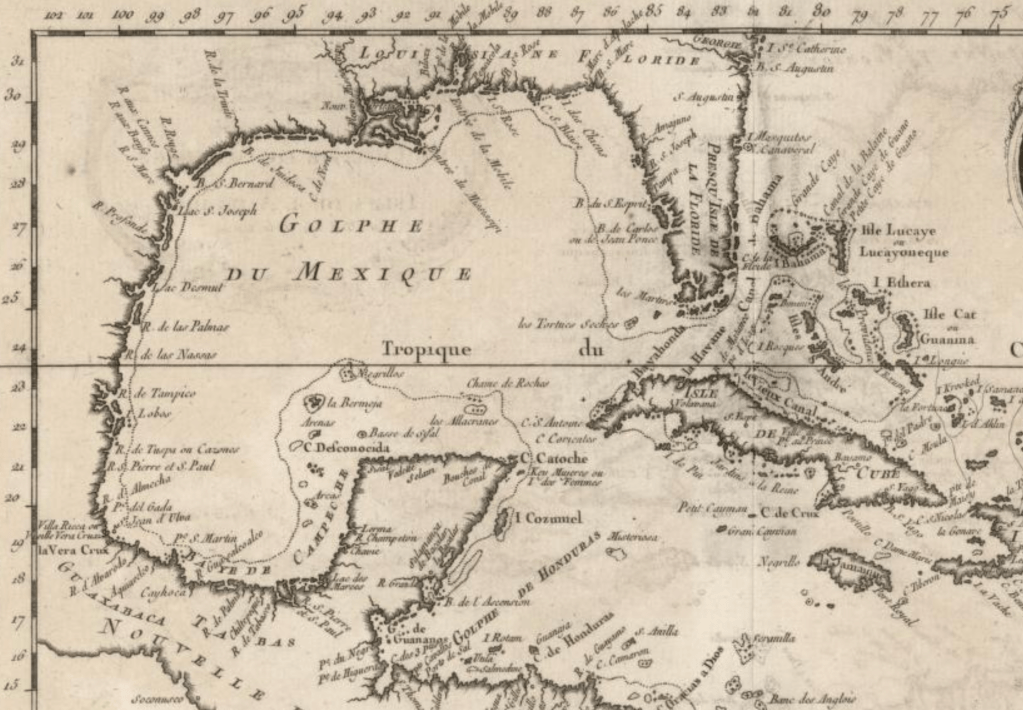

The rationale for renaming was of course then to define the control over routes for the silver trade, and ensure a monopoly on traffic through this bay that became a focus of economic traffic to the New World. Centuries later, the historical nature of this shift of names laid a claim American oil companies had staked to extract the region’s submerged wealth. The Gulf of America was a Sovereign Wealth Fund waiting to be extracted, there for the taking by multinationals with the Trump White House’s happy imprimatur. To be sure, the idea of a Sovereign Wealth Fund was never part of American government, but it fit the lines of Donald Trump and Don, Jr.’s friends in Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi–some states, as Texas, already had one, and the other bayshore states from Louisiana (then under French sovereignty) and Florida (then under Spanish dominion) had long changed to states in the union. Yet it is hard to cast the Executive Order simply as an updating of claims to sovereign in an area long known as the Gulf of Mexico–as if the name change reflected a pressing need to be bought into line with the Adams-Otis Treaty that freed Florida from Spanish sovereignty or Louisiana Purchase–rather than rely on antiquated mid-eighteenth century maps that identified “America” only with the surrounding islands, long out of date-and not a land grab of underseas wealth of hidden treasure that the United States felt itself empowered to annex.

Golphe du Mexique et des Isles de l’Amérique (Paris, 1754)/Library of Congress

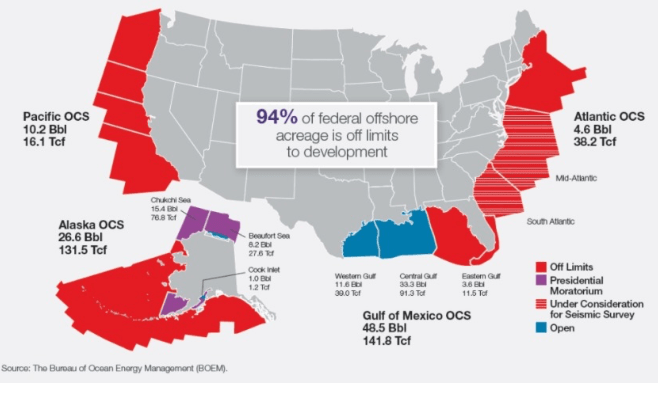

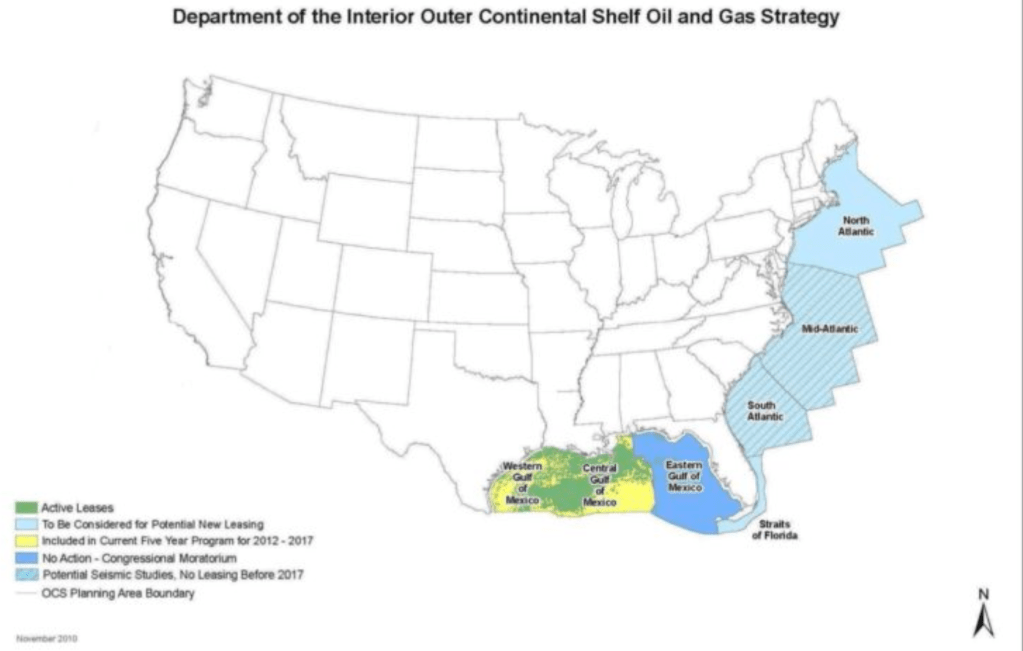

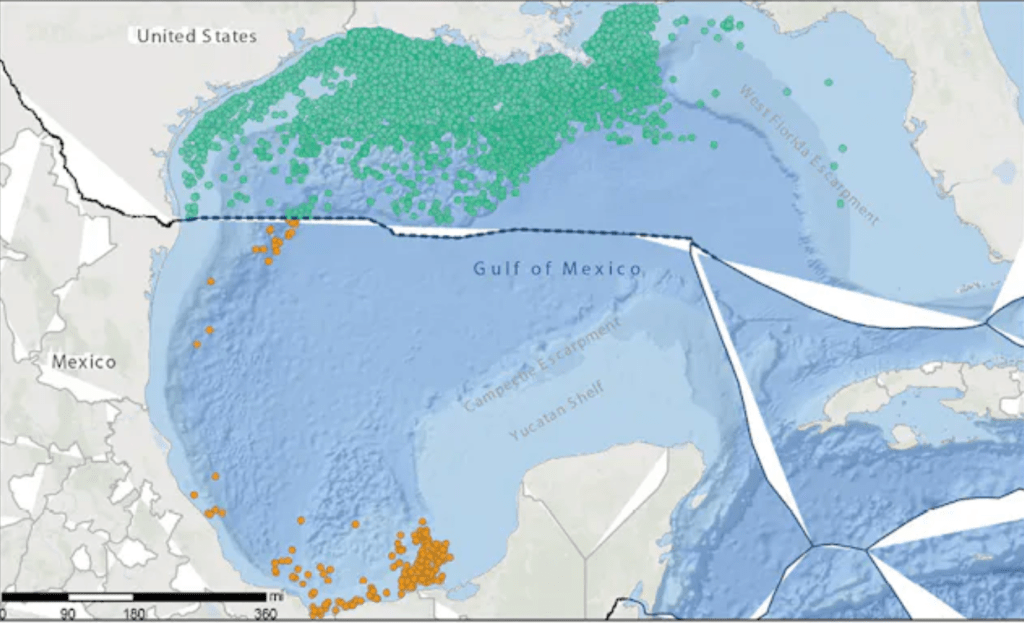

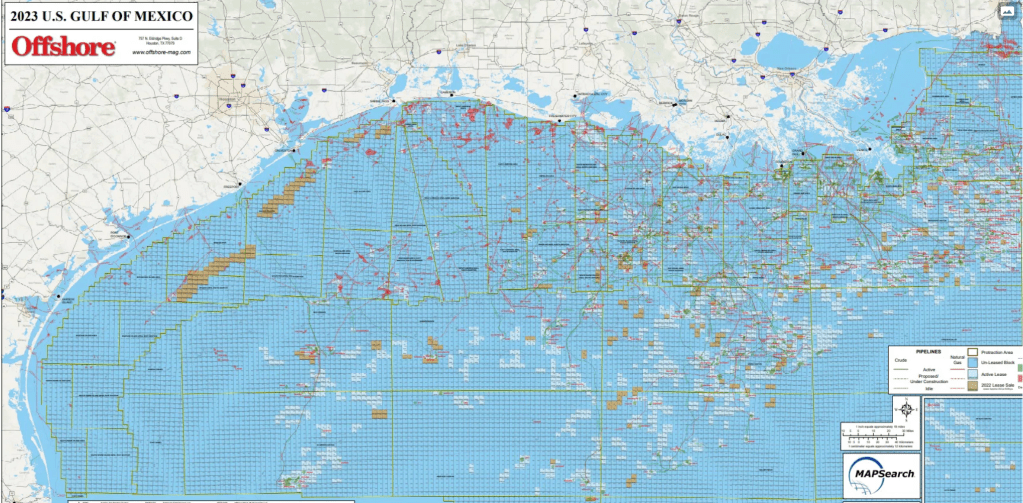

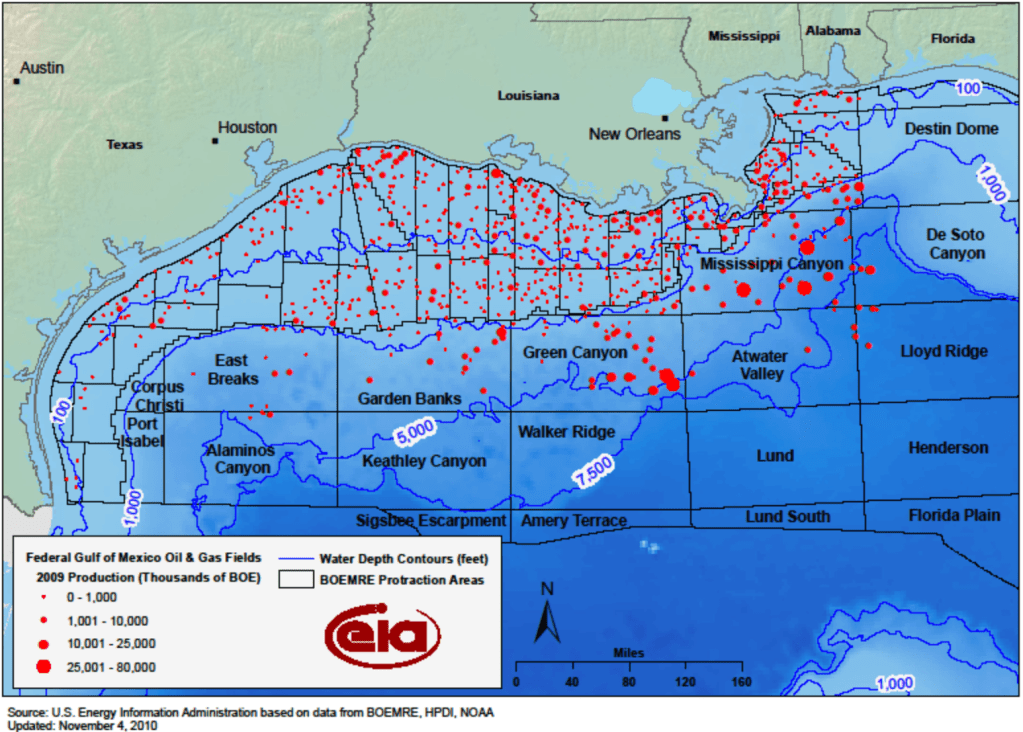

Although promoting offshore development had roots in the commission to remap the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) to oil and natural gas exploration to redress the status quo in which 94 percent of federal offshore waters remained inaccessible to plans for expanded energy extraction, a huge multiplier of state revenue streams of potentially untold dimensions, free from regulatory oversight. Indeed, the renaming of the “Gulf of America” is an annexation of mineral wealth, in case you hadn’t noticed, in what is far more than a media stunt.

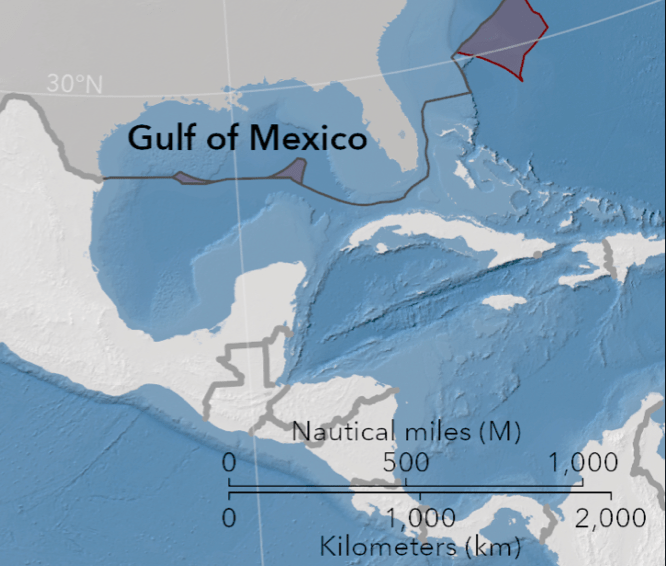

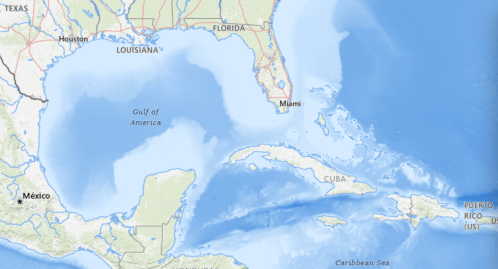

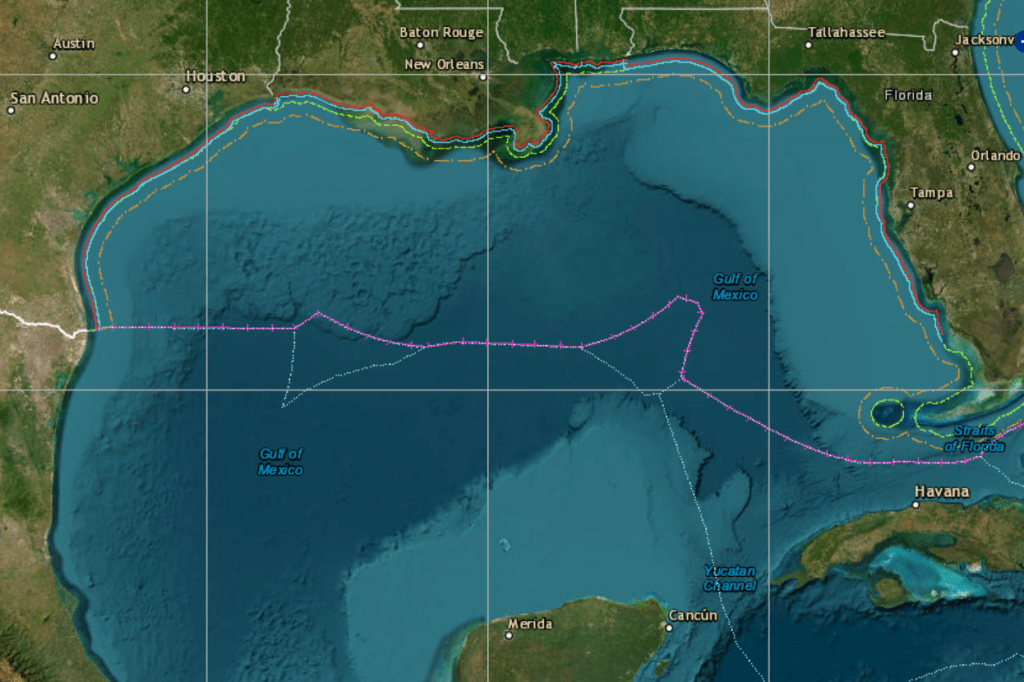

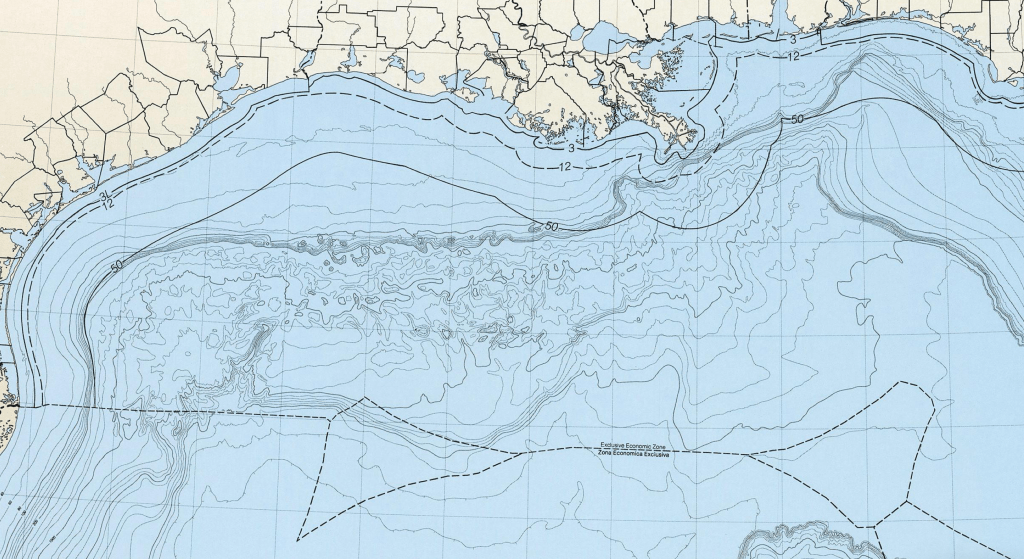

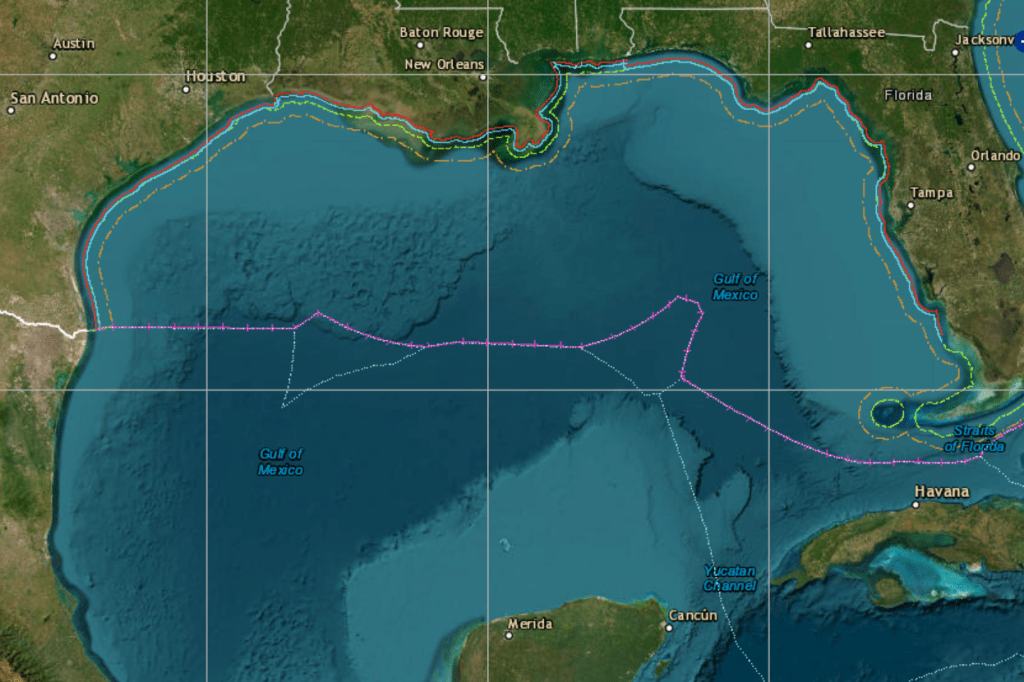

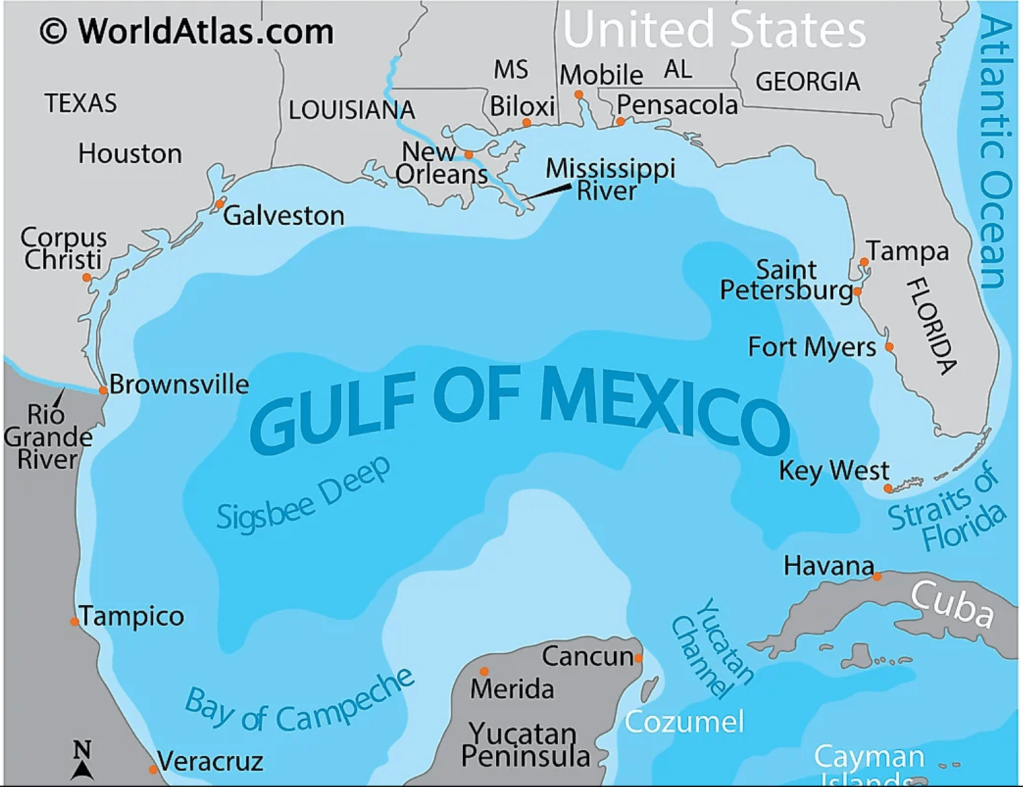

The problem of mapping the inlet of ocean water known for centuries as the “Gulf of Mexico” is illustrated by the MapBox imagery that locates the new name preciselyat its deepest waters, the contested areas body of water Mexican and American petroleum and gas seek to claim possession, adding a substantial amount of wealth to corporate ledgers, and boosting one national economy or another in ways that maps have suddenly put on the front burner of the Trump Presidency.

The problem of remapping is located in deep waters in either alternative name for the region, as the deepest areas of its waters–the “deepwater” sites of drilling and extraction–that were long held off the table during administrations with more concerns about environmental consequences, has long been targeted as a goal that the oil industry put on the front burner of the Presidential election, and Trump was, this time, more ready than ever to coopt as a platform as if it would Make America Great Again–or be an issue of domestic policy for the Secretary of the Interior to plan.

As much as the renaming of the Gulf of Mexico undercuts history and cartographic custom with a vengeance, the neo-imperial renaming seem to herald victory in an intense fight for underseas minerals waged by oil companies for leasing more offshore lands around the nation. For the un-naming the Gulf of Mexico is not only Newspeak of a dangerous sort, a spin on the rebordering of America that is a core MAGA principle, but is a craven advancement of oil companies’ interests. The renaming was presented free from any fingerprints, as if it was a right of the nation that would be at last rectified by the Trump Presidency, more than a priority of energy industries and petroleum extraction: the declaration on Inauguration Day that “[t]he area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico has long been an integral asset to our once burgeoning Nation and has remained an indelible part of America” conjured the cartographic indelibility of a map of clear borders. The new name of this “integral asset” was a claim of ownership and property, as if the real estate agent in chief was able to annex what was already “indelible” just to remind us of what one has long known. The new name was a way of restoring to America what was hers, lest we be ripped off, as much as asserting the demand for expanding offshore oil production.

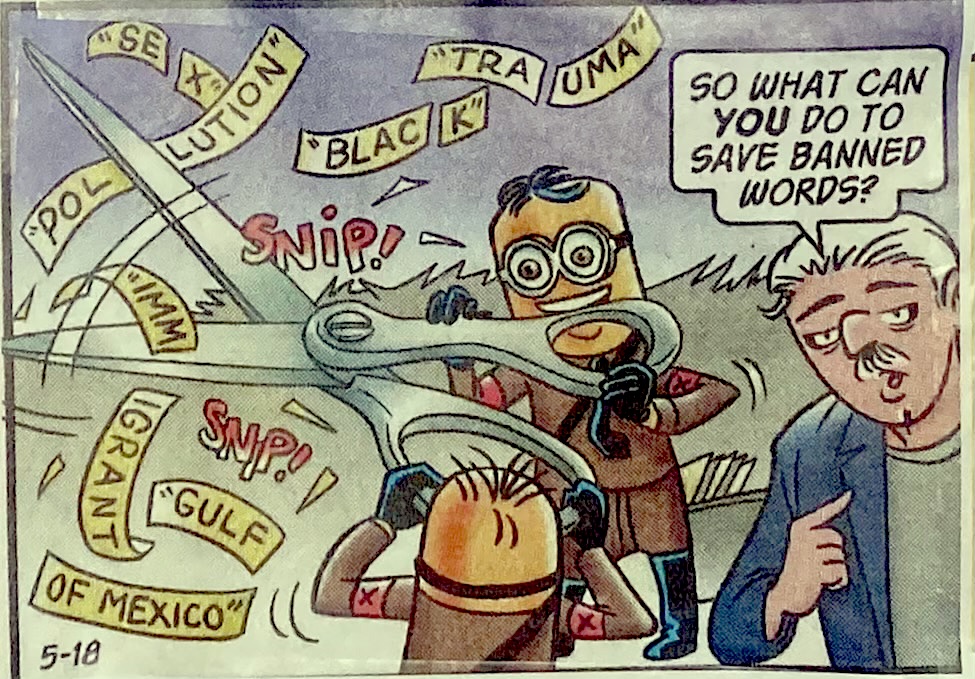

The un-naming of the Gulf of Mexico may mirror the un-naming Confederate monuments to Civil War Confederate generals, of slave-owners, or indeed of Columbus. For as an act of restoration and memory, renaming of the largest body of water in North America was a restoration of “American pride in the history of American greatness,” a rectified history more than asserting hemispheric eminent domain. (The name was to be reinforced as indelible by commemorating the February 9 edict as Gulf of America Day.) And as much as the parsing of other phrases suggested a snipping concepts was a Newspeak undermined cognitive abilities and mental tools, the severing of “Gulf” from “Gulf of Mexico” was an annexing of watery expanse in hopes to stake claims to energy reserves deep beneath the ocean floor, a search for wealth that, in the minds of the government and new Secretary of Interior, might be integrated into the nation’s economy and indeed be a promoted as a new foundation for national wealth, gained by cartographic fiat. As much as we abandoned terms as the results of the zealousness of complaint MAGA mixions wielding scissors gleefully to cut red tape and bureaucracy allegedly to keep down costs, sheering the language of governance by severing of “Gulf” from its less patriotic modifier to shift the hemispheric balance of wealth. The renaming planted a flag in an expanded underseas mineral and seabed–severing it from Mexico, in a voluntary act of Dada it was hoped public memory might mindlessly comply.

G. B Trudeau, Doonesbury 2025

This was nothing less than the perpetuation of a new religion of American grandiosity, an expansion of the boundaries of America to claim those areas of the Expanded Continental Shelf as if they were included in the Book of Mormon, and a recognition of American grandiosity recent maps had omitted and elided that placed the nation at a disadvantage, if one needed reminding, in a global marketplace. Yet this patriotic rhetoric of promoting a new religion, a truly revolutionary rhetoric worthy of the Festival of the Supreme Being, was a manufacturing of a new nation out of whole cloth, urging the nation to rally to “take all appropriate actions to rename as the ‘Gulf of America’ the U.S. Continental Shelf area bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the State of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida and extending to the seaward boundary with Mexico and Cuba” that would kill the spectral monster of “the area formerly named as the Gulf of Mexico,” an entity forthwith recognized as against the interests of state, and as thwarting American greatness. If global resistance mounted against the unilateral name change, that provoked perplexity and seemed an appropriation of a global map for national ends, the undoing of the maps recognized by the United Nations seemed as chrome-headed and obstinate as America itself, a vision of going it alone that seemed both bull-headed and deeply provincial, but was perhaps best understood as a crass claiming of power and hemispheric domination, aimed at ending global consensus.

How, Trump seemed to be asking the nation, did we ever allow this body of water in which so much offshore oil lay underseas, to be called the Gulf of Mexico, if much of our national wealth lay there? Trump seemed to relish calling for the collective brainwashing of the nation by beseeching “public officials and all the people of the United States to observe this day with appropriate programs, ceremonies, and activities,” as if the presence of the word “Mexico” in America’ offshore waters might be finally expunged, and we no longer need to ask why its presence was so long tolerated.

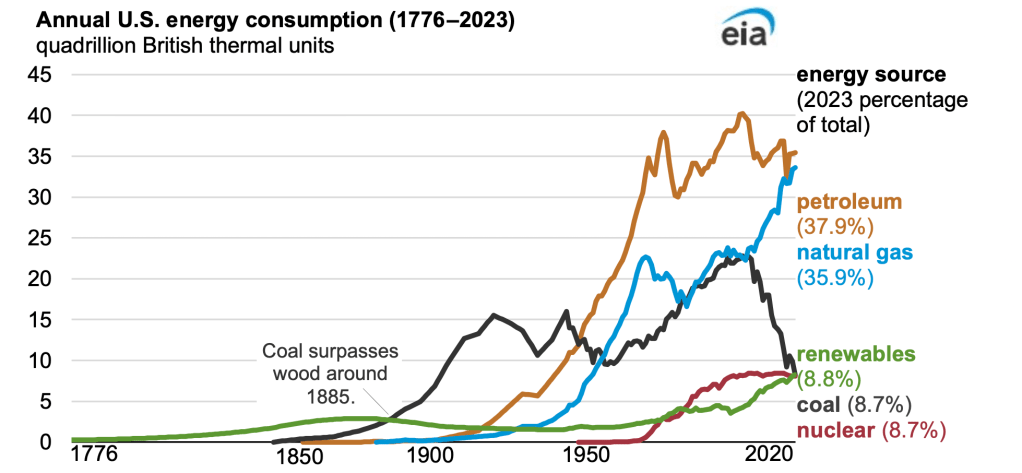

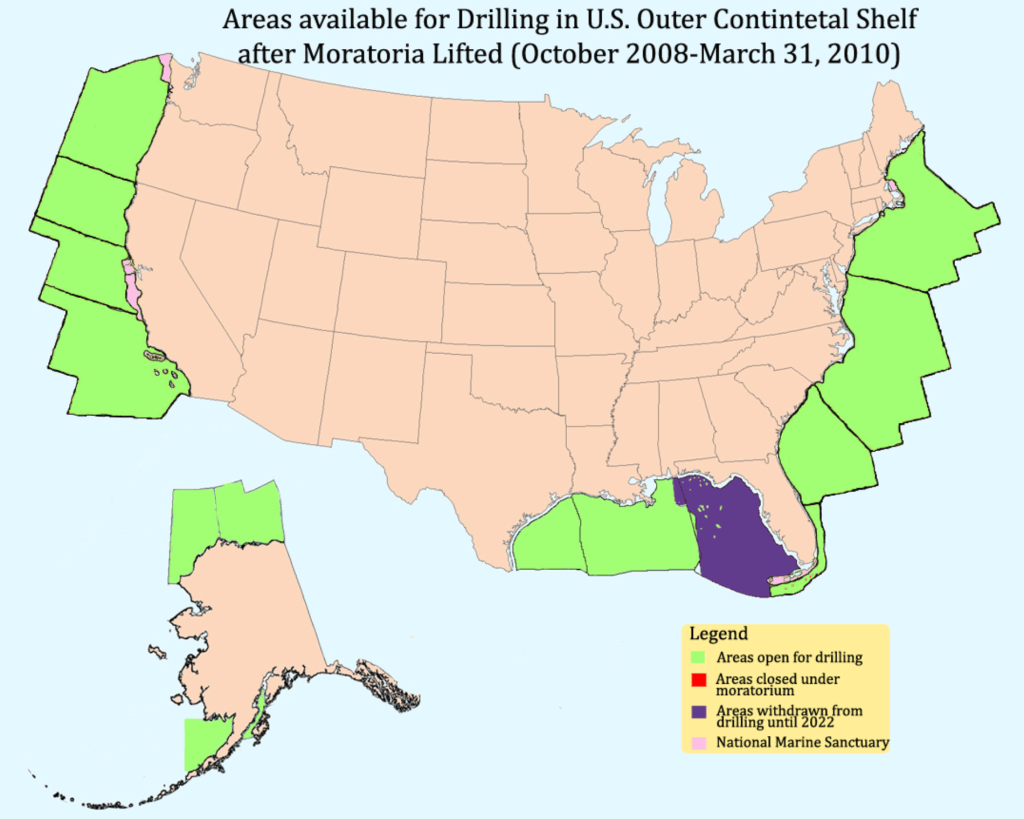

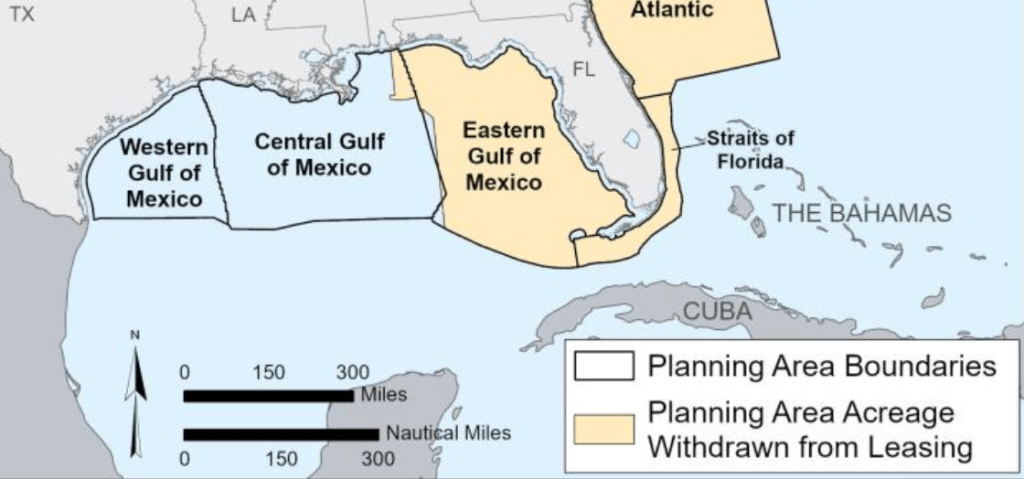

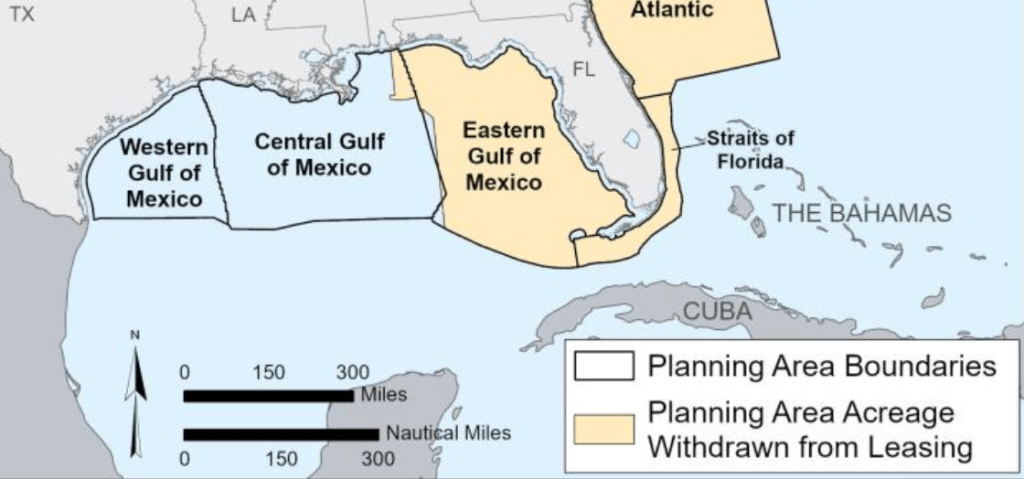

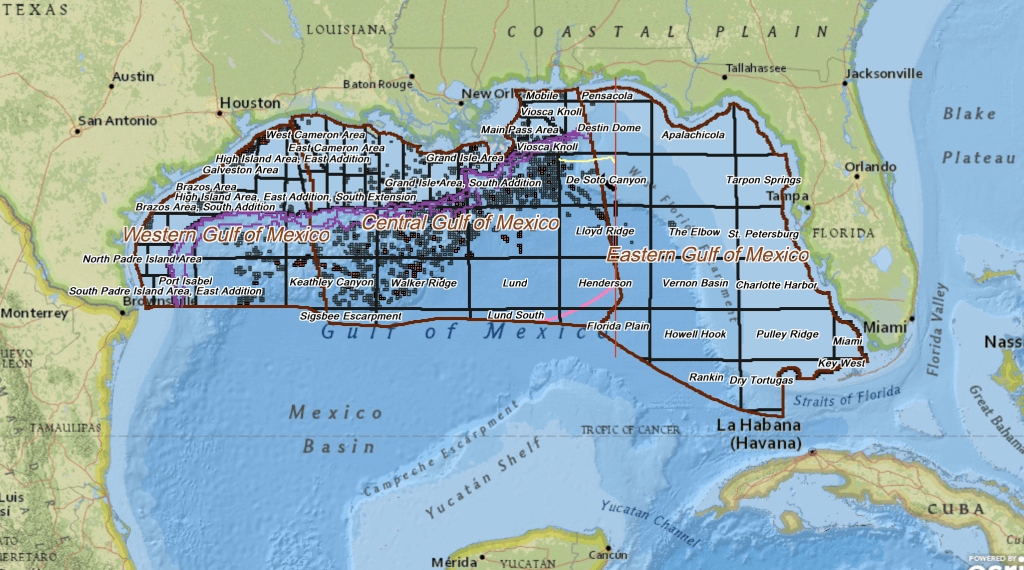

The rewriting of revenue streams from the Gulf Stream states by drilling outside the Western and Central Gulf of Mexico lead to the renaming of the region as a Gulf of America, as Trump seemed ready to see it–and remap it–as the new basis for a Sovereign Wealth Fund, What better place for staging such a performative statement than on the twin monitors of the Brady Press Briefing Room, demonstrating the usage newspaper reporters and the real guys on television would be compelled to adopt in order to be able to attend? This new expansion of American sovereignty that was being proclaimed in the Briefing Room was in a sense evidence of the generative nature of maps of the offshore regions in the erstwhile Gulf of Mexico, and Exclusive Economic Zone, as the Gulf of America was only the prime and currently privileged seat of extraction that was located in the expanded continental shelf to which the United State was ready to claim full jurisdiction. As much as being a reflection of Make America Great Again, the Gulf’s surprise renaming can be traced to the decision of oilman George W.Bush to end to the decades-long ban on offshore drilling in the summer of 2008, opening 500 million additional acres for new energy production that contain an estimated 14 billion barrels of oil and 55 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

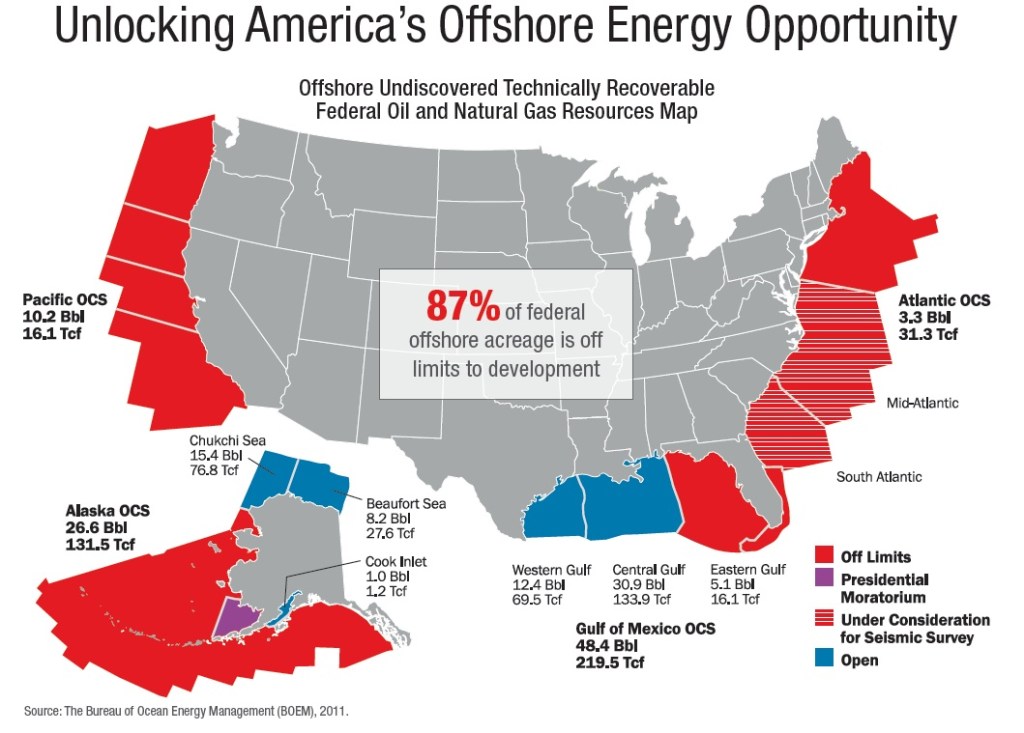

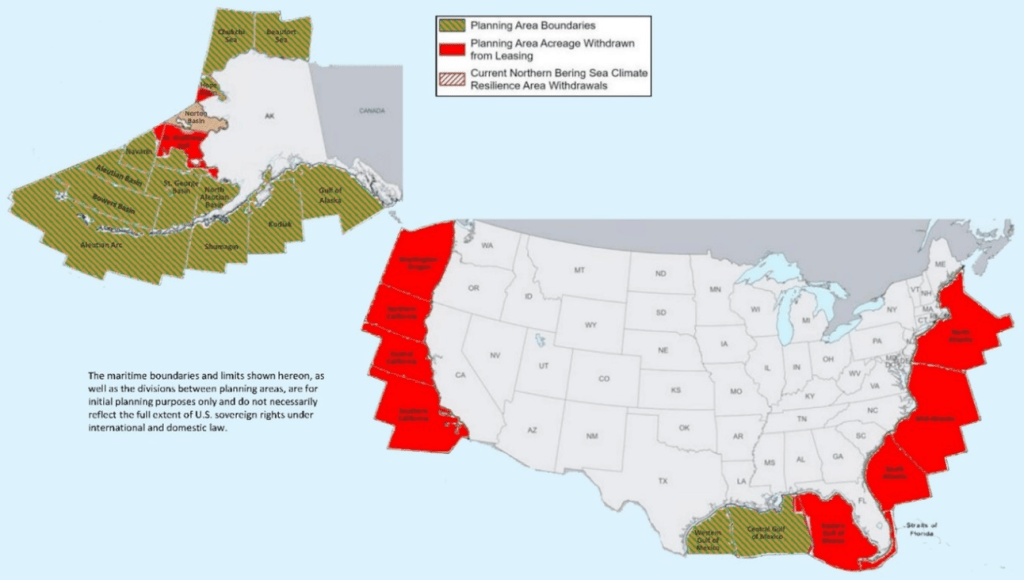

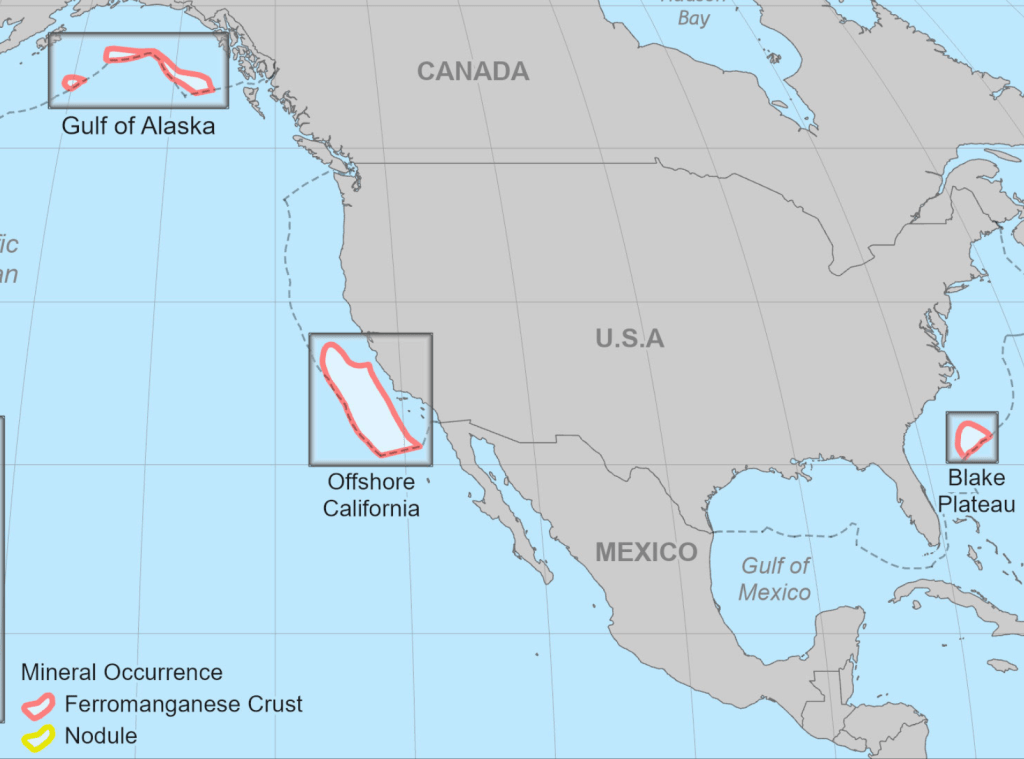

The map of “energy opportunity” dated back ages ago, rather than being a creation of the Trump Era, or even Trump 2.0. But the Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management had been eager to assess “undiscovered oil and gas reserves of the nation’s Outer Continental Shelf” as a new bonanza of a new Wild West, having claimed the discovery of a new reserve of a “technically recoverable” 90.2 billion barrels of oil and 404.6 trillion cubic feet of gas waiting to be unlocked, in ways that would make the debates about fracking in Pennsylvania that played such a prominent role in the 2024 election as mere window dressing and just a fig leaf of the emissions risks and costs of offshore pollution of the new map of energy resources that were central to the underseas research of the Bush administration, and an inheritance of the Reagan years.

Bush envisioned a Wild West of the OCS–Offshore Continental Shelf–long floating around in maps, but which then-Senator Barack Obama vowed he would, if elected, stand firmly against. Yet the only “open” area seemed the Gulf of America, and it might as well be called what it was, and embraced into our national waters and territorial jurisdiction, even if submerged. To understand this map, despite the dominance of the flat, two-dimensional visualizations of the API and the Trump Presidency, only by looking at the maps of geolocation of offshore energy reserves that led to the mapping of the “OCS” as a geographic concept can the remapping of the region of the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America be fully fathomed.

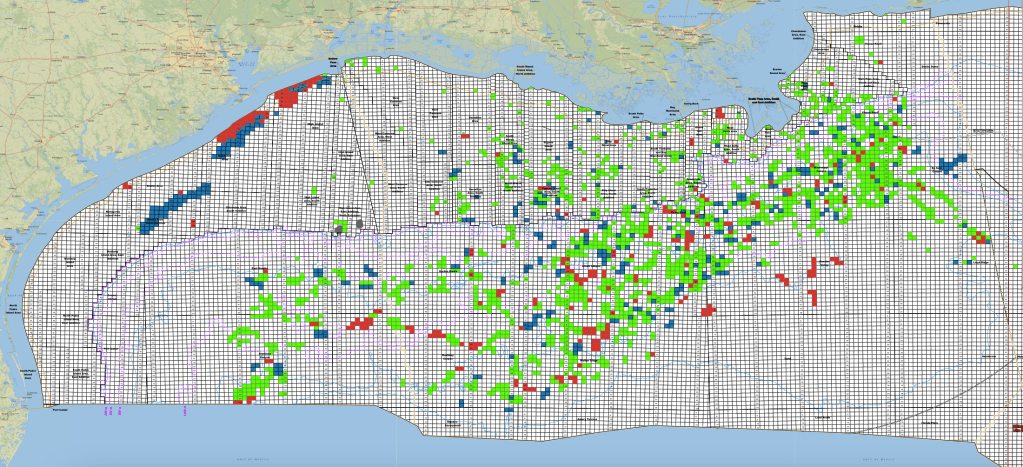

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, 2011

While a nominal victory over reporters who bucked the Executive Order to retain usage of that quite storied nomenclature,”Gulf of Mexico,” in the face of guidances from the Trump White House.

Donald Trump 2.0 seems particularly eager to retire the qualification of Mexican territoriality as a geographic reference points of the twenty-first century. To be sure, the hopes for expunging “Gulf of Mexico” from all maps is less easily accomplished than by issuing guidances on geographic names. But the guidances demand to be understood not only a shift of names, but a demand for compliance, and a needed boost to map a new relation of the United States to the world order, akin to a wall on the southwestern border. If building is what Donald Trump has long described himself as qualified for the United States Presidency, the basis for a promise to Make America Great Again, the new mapping staked out the hydrocarbon reserves in the expansive basin once known by the nation of Mexico as a totem of the growth of American gas and oil, offshore areas that were opened by President Bush on an “Outer Continental Shelf” but taken off the table in 2010 by a former President who Trump has long antagonized to a degree that demands to be acknowledged as the prompt for his entrance to the American political scene–Barack Obama–whose every political act has been seen as a basis for Trump’s triangulation of his own political positions, in ways that go far beyond partisan divides–from the American Cares Act, DEI initiatives, immigration, climate change, coastal preservation, and the very celebration of America’s diversity–so much that he acknowledged bitterly the existence of a “through line for all of the challenges we face right now.”

The deep anxieties that Trump’s 2016 victory and nomination of Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State in 2017 led Obama to ban all future offshore oil and gas drilling from nearly 120 million acres of land in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans, from underwater canyons along the Atlantic stretching from Massachusetts to Virginia, virtually all of the U.S. Arctic, the entire Chukchi Sea and all but a slice of the U.S. Beaufort Sea, trusting that the permanent withdrawal of leases of underwater lands would sent a precedent that Trump would be an unlikely violation of decorum to revisit, would be difficult to rescind and violate all according of decorum to predecessors. But after her had opened some areas of the Gulf of Mexico to exploration, and even asked Congress to lift a ban on drilling in the oil-rich waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the areas withdrawn from drilling until 2022 were open for being revisited by the Trump White House–

–creating the perfect storm to retake the offshore areas once “open for drilling” that were withdrawn by 2010 to be open for energy extraction. For all the banning of offshore drilling in Trump 1.0 back in 2020, that withdrew areas of the Outer Continental Shelf from drilling, after being poised to open the offshore areas to oil and gas drilling–retricting OCS development in the face of open resistance from East and West Coast states–even as it also halted the development of coastal wind farms he has long opposed.

The new Gulf of America was a slap against the notion of international development of what was once the Gulf of Mexico, as if building a virtual wall across the Outer Continental Shelf in a hazy patriotic bluster. While President Trump did not suggest he was undermining precedent, by actively excising a long cartographic history that placed the Gulf of Mexico in American maps–from teaching aids to atlases to cartographic reference points–works of reference were beside the point to a focus on offshore oil and gas. One might cite, to little effect, the accord of the Disturnell Map that was appended to the Treaty of Guadulpe Hidalgo in 1847, and marked the first survey of the 2,000 mile US-Mexico border, the boundary survey that led to the placement of a line of obelisks set in the arid plains “with due precision, upon authoritative maps, . . . to establish upon the ground landmarks which shall show the limits of both republics” from an age when few had actual paper maps who lived in the region–and would rely for property lines, farming, and territorial policing by marking the border with obelisks twenty feet in height visible from a “great distance” completed in 1857, to render the map visible on the ground by fifty-two monuments of mortar and dressed stone situated in barren and uncultivated lands.

That map of a “true line” to “end uncertainty” of the “Estados Unidos de Méjico” took at a reference point the “G. de México” and the rump to which Trump would reduce the Gulf of Mexico, by Executive Order, of “Bahia de Veracruz.” By opening all United States waters for offshore drilling, the President was boosting an illusory image of “wealth” of America–promoting rights of renaming that smelled of the nineteenth century more than the twenty-first–by declaring a windfall national economic reserve and wealth as if none of his predecessors were ever assured to stake. By magnifying the seigneurial right over the Gulf–renaming the largest basin in North America by its deserved name–the right of the nation to the underseas reserves of energy that were possessed by Norway, Canada, Argentina, New Zealand, Australia, and Mexico–in ways that would suddenly amplify, as if by a needed magic trick, the offshore reserves of the United States by discovering the newly named Gulf of America.

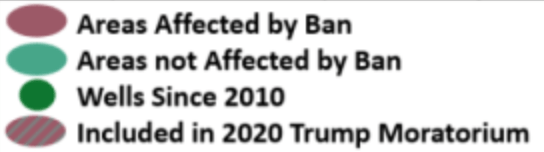

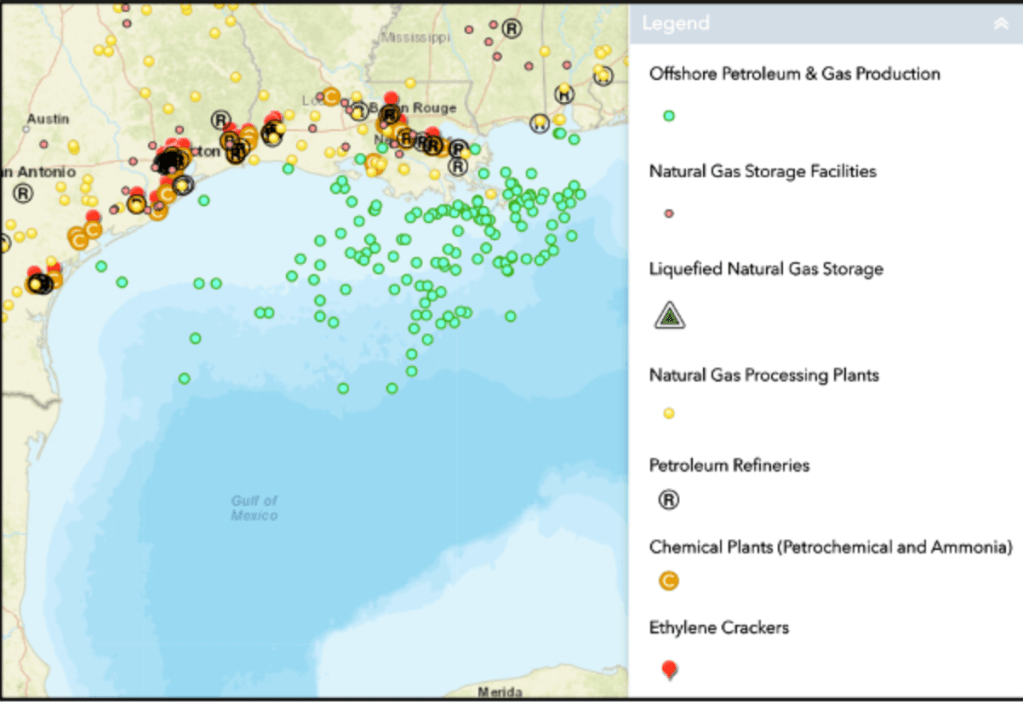

Early mapping of the “offshore” region of the OCS suggested an area of planer that Trump didn’t have his eyes on, but had a rather spectacular way of unveiling for open leasing on national television, performing as the pitch-man for the offshore drilling companies that had so generously bankrolled and funded his campaign, and which the opening of leases was the final quid pro quo, in the transactional presidency that so deeply relies on an essentially premodern notion of “patrimonialism,” in which the President empowers oil companies to exploit the hidden resources that lie underseas off the continental shelf, and augments its own power by declaring the ability to symbolically open the area to drilling by renaming it–and indeed revealing in how the offshore Outer Continental Shelf Areas of the United States are open to federal control–and the sites for some of the greatest public-private cooperations of all time. What more profitable way to reveal a President’s personal control than dispensing of rights to lease expanded areas for offshore Petroleum and Gas Production that augment areas currently operating in the Gulf of Mexico?

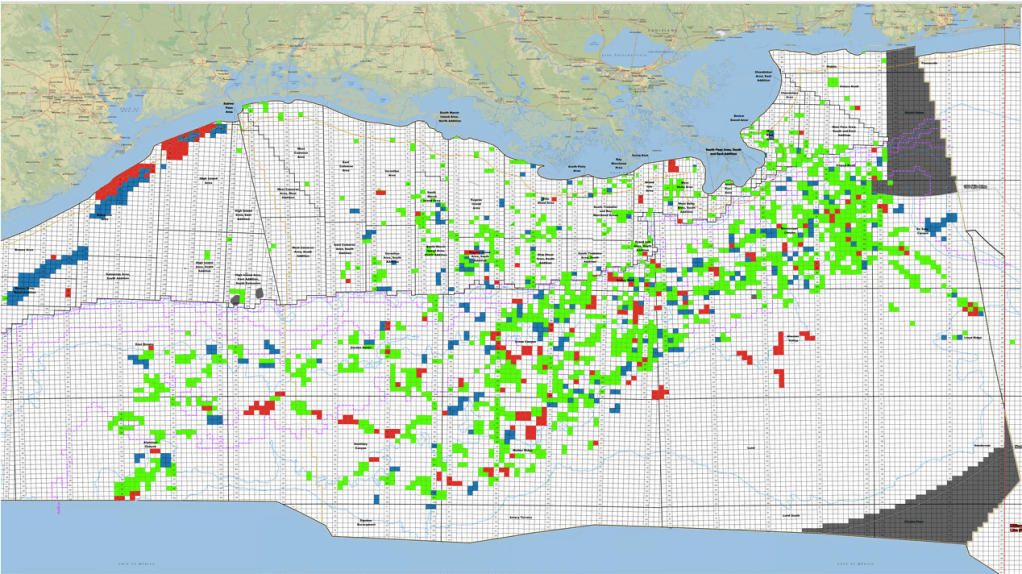

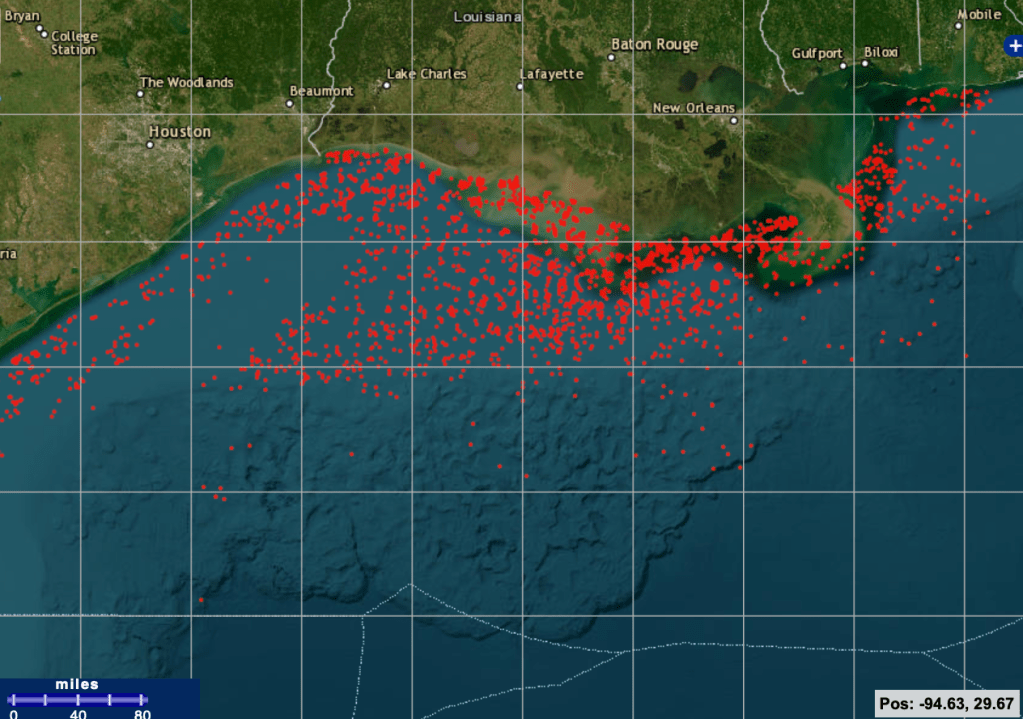

Offshore Production of Gas and Petroleum in Gulf of Mexico, Refineries (R), and Chemical Plants/Whistleblowers.org

While the initial decision to rename the Gulf date from the raft of executive orders that include withdrawing form the Paris Climate Accords signed a decade ago to reign in global climate emissions, as part of the “Restoring Names that Honor American Greatness” to rename waters of the “US Continental Shelf area bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the States of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida and extending to the seaward boundary with Mexico and Cuba.” White House guidances discourage federal agencies form publicly referencing clean energy, Gulf of Mexico, Paris Accords or environmental quality on public-facing websites–

–that run the gamut to shift the relation of governance to cognitive equipment that seem designed to compel renaming the Gulf of Mexico to remap Americas’s relation to the globe. For as much as the attention to the region as a repository of offshore wealth removed from sovereign jurisdiction and taxation, the real riches seem to have been mapped in the BOEM’s assessment based on a “comprehensive appraisal that considered relevant data and information available as of January 1, 2009”–or just before Barack Obama took office as U.S. President–of the new “potentially large quantities of hydrocarbon resources that could be recovered from known and future fields by enhanced recovery techniques” which were never on the map–or visible–to energy multi-nationals of the past, but which Trump is now ready to claim as the seedbed for a Sovereign Wealth Fund.

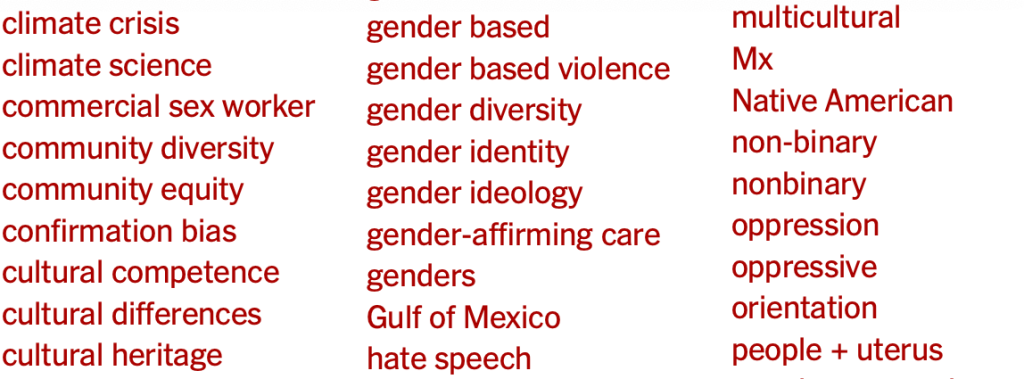

Federal Outer Continental Shelf of the United States/Bureau for Ocean and Energy Management

So long, that is, as it is not being restricted in any way by the Environmental Protection Agency, and areas of drilling for gas and oil are taken off of the map for the seemingly petty reasons of preserving our coastlines and national shores. The triumph of a governance over these reserves, technically recoverable but taken off the table by the priorities a few Democratic Presidents set, meant that energy industries were ready to fund Donald Trump’s campaign, to have a person in the White House who as First Among Equals, Primus inter pares, was able to understand the priorities of the energy multinationals to evade regulations and restrictions, and indeed, as a poster boy of the type of evasion of regulation that had hindered energy exploration in the past, would be just what the doctor ordered after the restrictions on offshore drilling boded by the Biden and Obama years. For the areas “withdrawn” from drilling that Trump put back on the table as soon as he returned to office suggested a virtual orgy of offshore drilling with full abandon, of which the Gulf of America could be the poster child for recovering underseas reserves for a new Sovereign Wealth Fund.

If the areas that President Biden removed from future leasing for oil and gas are now indeed unavailable online, having been purged from the newly unveiled Department of Interior website, as if the Gulf Waters were internal to the nation. Amidst discussion of the attempts of the government to preserve coastal economies, protect marine ecosystems, and protect local economies from the environmental impact of drilling for gas and oil were taken off the table by the Trump administration, to end the “war on offshore drilling” that Democratic presidents had long been waging at huge economic costs to the nation.

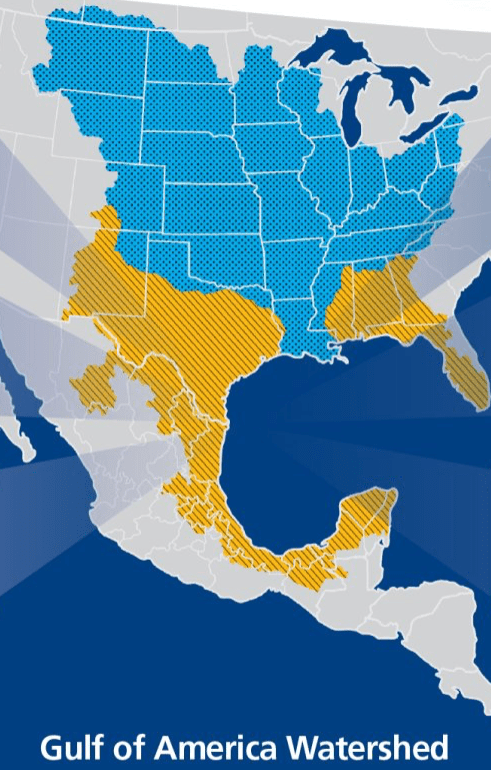

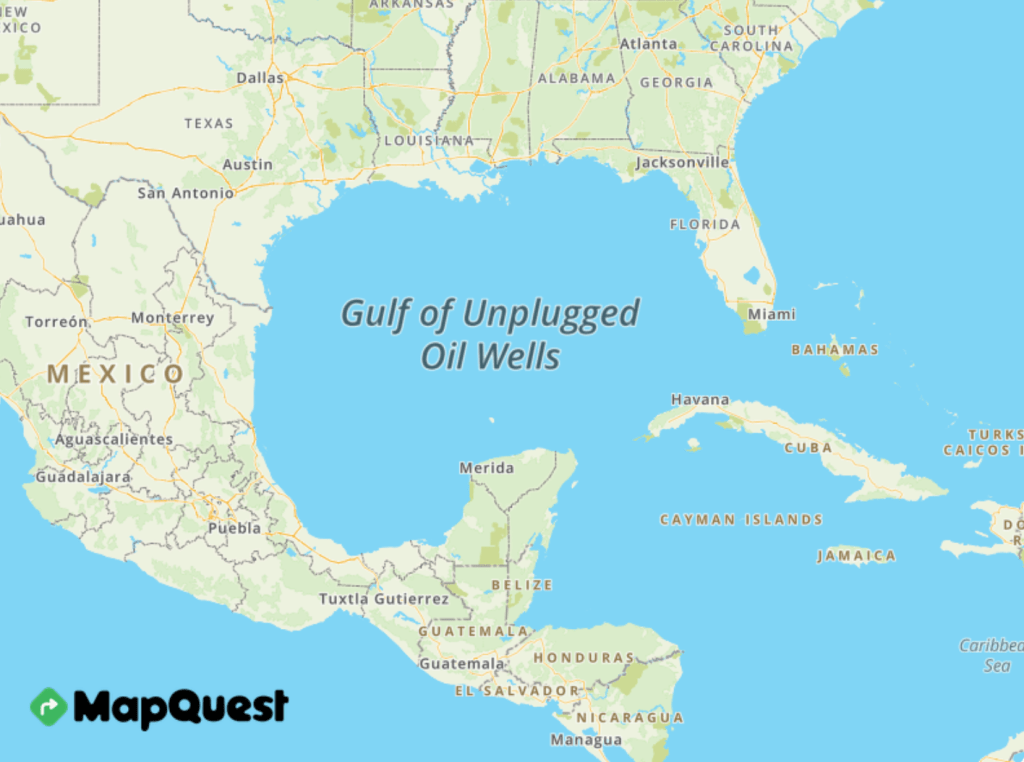

The suggesting of eliminating the Climate Crisis, Gulf of Mexico, and climate science at one blow from the national lexicon of governance suggests an inauspicious triad. The shuttering of office of environmental justice by the Environmental Protection Agency to assess environmental damages is a nation-wide blitzkrieg of unprecedented scale, transforming the environmental monitoring of the hundred and fifty factories packed into an eighty-five mile stretch of the Mississippi River recently mapped as a Cancer Corridor–suggest the new mandate of the agency as preserving business more than a healthy environment. Indeed, the map of the Gulf of America watershed below shifts focus from that river’s watershed to a coast that “is ready to protect” to “power our Great American Comeback”–placing a premium on a vision of government as a business-model of enabling metro-chemical industries by tapping the rich reserves of hydrocarbons that are so abundant on its floor.

If the “Gulf of America” is seen as an extension of the United States even beyond Central America in the public-facing map of the region the Environmental Protection Agency sports as its splash page-

EPA/Supranational Gulf of America Watershed

–the map is odd in its erasure of the United States-Mexico national border that was so foregrounded in Trump’s first Presidential campaign, and suggests the new view of autocratic government from Washington Big Oil wants to promote, of a blue watershed from rivers that flow to a bay rich in reserves of hydrocarbons in its depths, where 97% of offshore energy gas and oil are extracted, without environmental oversight.

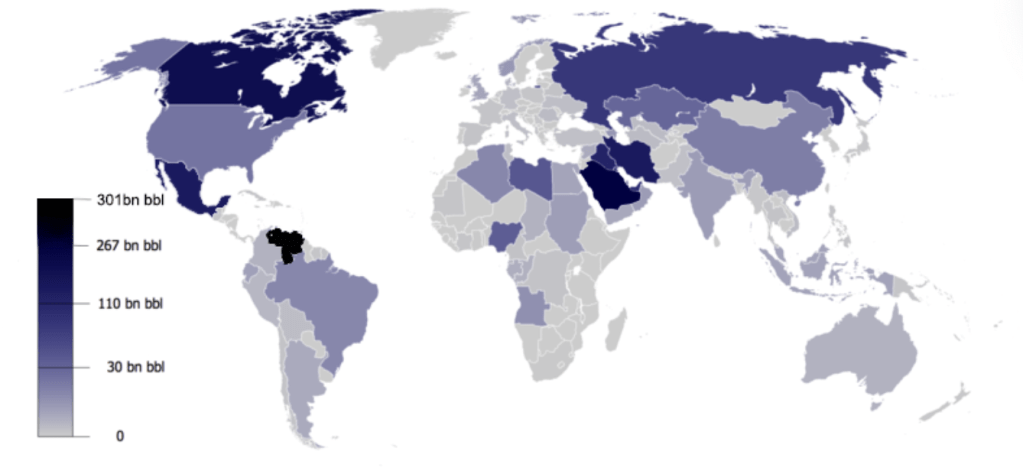

The largest body of water in North America is now firmly part of American territoriality–and the area producing a fifth of crude production in the United States was gonna get bigger, boosting the onshore oil refineries already refining 45% of the nation’s oil and processing 51% of its natural gas. The boondoggle gift to energy companies would be quite the bonanza for the petrochemical hub. Indeed, if the United States ranks relatively low on the list of nations with proven reserves of oil, the sudden amplification of offshore oil production would not only reverse the ban Jospeh R. Biden issued on his way out of office–

–but boosted the low-ranking of the United States, one of the largest consumers of oil, among global nations with proven reserves of crude of their own.

The map illustrates the seriousness of seeing government as a business, not a duty of governance. The five million acres of the watershed suggest the of which only 2.4–less than half–are currently used for offshore oil and gas development, of which 1.7 million acres were but recently auctioned off by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) the previous year, but more deepwater sights are to come. And even if the Supreme Court has deferred the recent demand of Gulf States to obstruct environmental lawsuits from being brought, a further curtailing of EPA authority, the prospect of an “EPA [that] is ready to protect” a region that combined the drainage basins of the Mississippi River and the Drainage of Basin of the Gulf from other waters, is a virtual land grab, not by any war but as a fait accompli. But the new nomenclature seems a bit like herding sheep; Google is sort of ready to play along with the name purge, and the sovereignty claimed over the deepwater regions of the Gulf in the newly mapped “territorial waters” of an Expanded Continental Shelf (ECS), surveyed over the past twenty years as if in preparation for a Trump Presidency, augmenting grounds to extract hydrocarbons and mineral wealth–expanding the national offshore perimeter to the continent’s “submerged edges” expanded, for ten million, the nation with the “right” to remap waters proximate to its national territory–and considerably expanded its wealth. (And these are the folks who call Social Security a Ponzi scheme! They know from where they speak.)

Google Maps

Google Maps rather lightly adopted the new terminology in a modestly sized low-visibility font, perhaps as if hoping that the name of aqua font seep into the waters that it colors baby blue that almost masked the real territory on the deepsea floor over which Trump sought to assume leverage by disassociating it from Mexico entirely, and promoting the deepsea regions believed rich with gas and oil alike of the Extended Continental Shelf as American territory.

Offshore Gas and Oil Production in the former Gulf of Mexico/National Whistleblowers’ Center

Compliance was shockingly swift in the weeks before the map was rolled out–on Trump’s flight to the Gulf States to attend the Super Bowl in New Orleans, where he must have shared high fives with Louisiana big wigs. The Coast Guard proudly adopted the change form January 21 to describe the maritime border between Mexico and the United States, as weather alerts across the Gulf States, but the remapping of the Gulf faced some pushback as a new way to envision the nation won. Despite the resistance of the AP, the apparent victory of a legal decision that the White House could ban news offices who failed to adopt the name from the White House and AirForce One if they retained Gulf of Mexico seemed a victory of sorts. Trump’s Press Secretary claimed befuddlement and a false outrage that befit the Trump administration, while deflecting where the decision to adopt the new name originated in government. News outlets who disseminated “lies” as they “don’t want to call it that” disguised “it is a fact that the body of water off the coast of Louisiana is called the Gulf of American” Apple and Google do, she noted. (The New York Times and Washington Post considerately don’t to not confuse global news markets; FOX embraced the new nomenclature.)

The new map was presented on twin monitors at a news conference after the judge supported the new policy of disinviting the Associated Press to the Briefing Room, Oval Office, and Air Force One, as if it to spoke for itself, revealing an objective reality following the guidances for “Gulf of Mexico” among the growing list of name to disappear from public facing website, federal communications, and instruction–the list from “clean energy crisis” to embraced “Native American,” “hispanic American,” and even “orientation,” that might make one think the purge was cartographic, as well

For in excluding words from governmental language, we are impoverishing our own relation to the world. And the apparent victory came that the White House was not being punitive to restrict access to the President to those adopting the change in name of the largest body of the water in North America surely recast that body’s relation to sovereign space in ways that curtailed our understanding of global warming, and global relations, as well as concluding all transnational projects that were hoped to attract investment in the prospecting of energy from the Gulf.

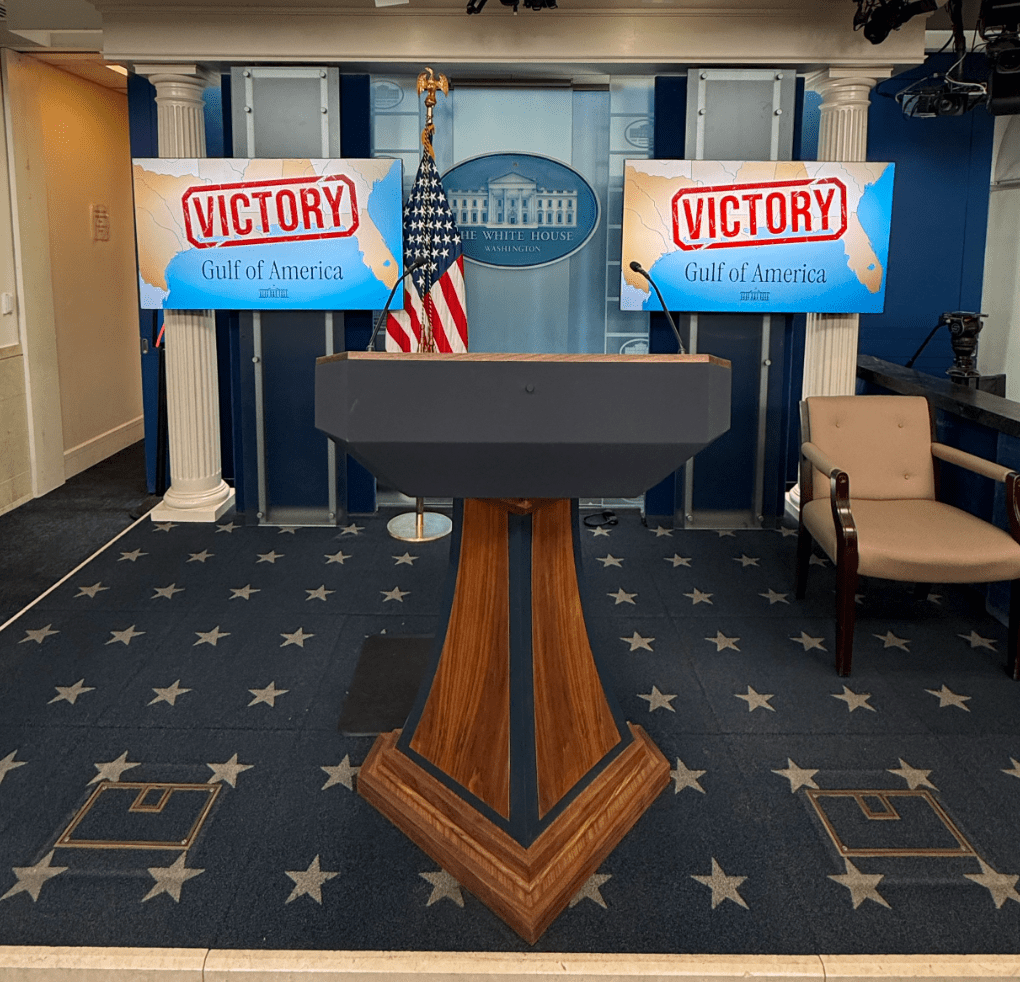

The renaming is the latest foray of a decisive turn to running government like a business, rather than a government. The purging of the Gulf of Mexico from the Geographic Names Information Systems served “to reflect the renaming of the Gulf and remove all references to the Gulf of Mexico” was mapped on the two monitors placed on either side of the podium, emblazoned with VICTORY in telltale all caps, feeding news agencies with their basic talking points as a way of remapping America’s orientation toward the world. By visualizing a body of water on which American oil companies have long had their eyes, the Trump administration seeks to leverage as a vital resource for sovereign wealth–and the seedbed of a Sovereign Wealth Fund for the United States.

The maps foregrounded the gulf states’ new ties to the body of water had premiered on Air Force One, quite eerily as it flew above the waters, as if a mobile White House, as the President, flanked by the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and his telegenic wife, symbolically claimed the region as a part of the interior. This was a declaration of enforcing compliance with the new mapping of the United States in the world in an era committed to make America Great Again.

The Executive Order to “honor American Greatness” was already a lot to unpack–partly because it assumed, MAGA style, that American Greatness exists and was able to be restored. The rebranding of a body of water uncannily transposed the language of conservation and coastal restoration to monetize the region as a hidden and untapped reserve. “Names that Honor American Greatness” mapped the basin’s “bountiful geology” not as a site of migrating wildlife or coastal habitat, but as “one of the most prodigious oil and gas regions in the world,” offering untapped reserves of crude and “an abundance of natural gas,” for big oil industries to “tap into some of the deepest and richest oil reservoirs in the world.” Beside being “home to vibrant American fisheries, teeming with snapper, shrimp, grouper, stone crab, and other species,” the environmental map dismissed risks to its delicate habitat before “the multi-billion dollar U.S. maritime industry.”

The excuse of adopting patriotic language sought to access untold bounty and plenty. The renaming mapped the waters to hint at the potential benefit of extractions–not yet mapped for public audiences–optimistically estimated by Trumpian exaggeration of “truthful hyperbole” at a hundred trillion dollars in “assets” of untapped oils and minerals. The hyperbole set the stage to create an expansive Sovereign Wealth Fund for United States overnight by clever mapping tools, of the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. Despite recent hopes to combine a “US GoM” and “Mexican GoM” into a single commercial unit in an international investment community, renaming part of the Gulf so bluntly diminished any potential hopes for regional synergy, expanding access to the West Florida shelf and Louisiana slope, as well as the Mississippi fan, for Big Oil: extant offshore maps had constrained the expansion of offshore drilling in a basin where proliferating technologies of extraction were poised to exploit its resources far beyond the million oil wells already drilled in offshore shelves. The hope of expanding the number of deepwater rigs, without attracting any investment in the fifty-five deepwater rigs in Mexico’s national waters, was designed to promote America’s wealth, rather than to maximize resources of extraction.

The removal of the deepwater reserves ‘from’ the Gulf of Mexico seek to move the deepwater regions into the Expanded Continental Shelf of the United States, making it a source for sovereign wealth for future generations, in ways that move deepwater reserves into sovereign territory–

Of the Fifty Thousand Wells Drilled in the Gulf of Mexico, only Fifty-Five Existed in Mexican Waters

–as if moving the boundaries of marine territorial to include licenses to lease deepwater lands after the congestion of existing drilled wells, the name change conceals the hope to sell rights for drilling new wells into a region that was quite recently named the Gulf of Mexico. The body of water was defined mostly by American wells–but fifty-five were drilled in Mexican waters when Trump was elected–expanding offshore abilities to drill shelf and fans would end a moratorium on offshore drilling suggested a huge cash windfall to boost Trump’s ideas of a Sovereign Wealth Fund.

The name change decreed via Executive Order was proclaimed en route to New Orleans above the Gulf of Mexico in Air Force One, the newly mobile White House. Trump revealed the map, flanked by his Interior Secretary, as if with the blessing of the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum–whose presence suggested what sort of sleight of hand of making the waters part of the waters administered by there expansion of the “interior” department–if the in-air stunt of a proclamation seems pure Trump. Indeed, in using a map of offshore wealth to suggest the presidents’ sturdiness in steering the country to uncharted waters to reclaim its offshore mineral wealth, the debut of the map of coastal states provided a new image of the nation–

Interior Secretary Burgum and Wife Accompany Trump to Super Bowl Championship Game in Air Force One, February 9/Roberto Schmidt, AP

–of newly official status was eagerly presented by a pitchman-in-Chief.

For the map issued form a God’s Eye view of a podium that the Air Force One from a mobile stage in the sky of truly Orwellian character won accolades for its dramatic effect. “Did you see in the Air Force One they announced that this is the first time a president is ever flying over the Gulf of America, the newly named Gulf of America?” enthused Joe Rogan on his podcast. The map embodied the new name as a form of hemispheric dominance, as much as energy dominance, claiming expanded national energy resources. It was of a piece with the departure of the United States form the Paris Climate Accords of 2015, a declaration of hemispheric economic lebensraum, and a map of isolationism, tethering reserves of hydrocarbons deep under the ocean sea to sovereign wealth. The declaration of possession seemed half the game, and really the debut of a new map of the nation, ready for visual consumption and geography textbooks. It was not only a censorship of the press in the Briefing Room; the assertion of the objectivity was a proactive sally on the stability of geographic knowledge. it was an assertion of the objectivity of the sovereign map shaped with input from Big Oil, whose point man in the Trump administration 2.0 Doug Burgum had been long expected to be.

As much as renaming the Gulf “in recognition of this flourishing economic resource and its critical importance to our Nation’s economy,” the new relation of the Gulf renamed America to the state eerily coopted an environmental lexicon of ‘flourishing” and “critical importance” to dampen our collective critical sense, and displace the ecological complexity of its health. The new map arrived in the Press Briefing Room as a triumphal occasion that suggested victory for the United States, as if a battle had been won we hadn’t realized was being fought–it hadn’t–and a legal victory over the free press. And even without the obligatory exclamation point, the all caps announcement was enough to let the pressroom know that they had been collectively brought to heel. It was, however, also anticipating a real hemispheric trade war, that was about to brew, as the White House took the time to proclaim a declaration of victory on social media, exhibiting twin maps in the Press Briefing Room as if the maps were the message, and spoke for themselves.

Brady Press Briefing Room, February 28, 2025/White House Social Media

This victory was of course in contrast largely symbolic at this point, and virtual. Born of a court tussle with the Associated Press to assure its journalists access to the White House Press Pool to do their job, without conceding the unilateral change of the body of water in the press style sheet, it was not really about sovereignty, if it extended an unwritten frontier. Resistance to naming the Gulf of America to extend the territorial waters of the United States to the largest body of water in North America in some journalists’ style sheets was not only quashed. The promotion of the name in maps became a victory of promoting the MAGA agenda, by expanding the submerged lands of the United States government claimed territorial rights to lease, in its search for “energy dominance”–a critical pillar of the administration. Trump supporters felt the renaming kitsch–71% of those in the Gulf states opposed it; 72% of registered voters are refuse to support the name change.

Arriving in Miami February 19, 2025 for Meeting Sponsored by Saudi Arabia’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (Joe Raedle)

But the value of that name-change was clearer to Burgum, that Microsoft executive turned outdoorsman in North Dakota, Doug “he’s-not-just-an-oil-man-from-an-oil-and-gas-producing-state” Burgum, a graduate of Stanford University’s School of Business modeling his Teddy Roosevelt ethos, vowed to take a monetary tally of natural resources that he saw primarily as a proxy for national wealth. The gulf states foregrounded as set off the union by a light shade of tan–almost as if sand-colored–didn’t include clustered of oil platforms, rigs, or offshore refineries, but provided a tacit reminder for the rationale of renaming the Gulf, as if a declaration of hemispheric dominance in energy markets.

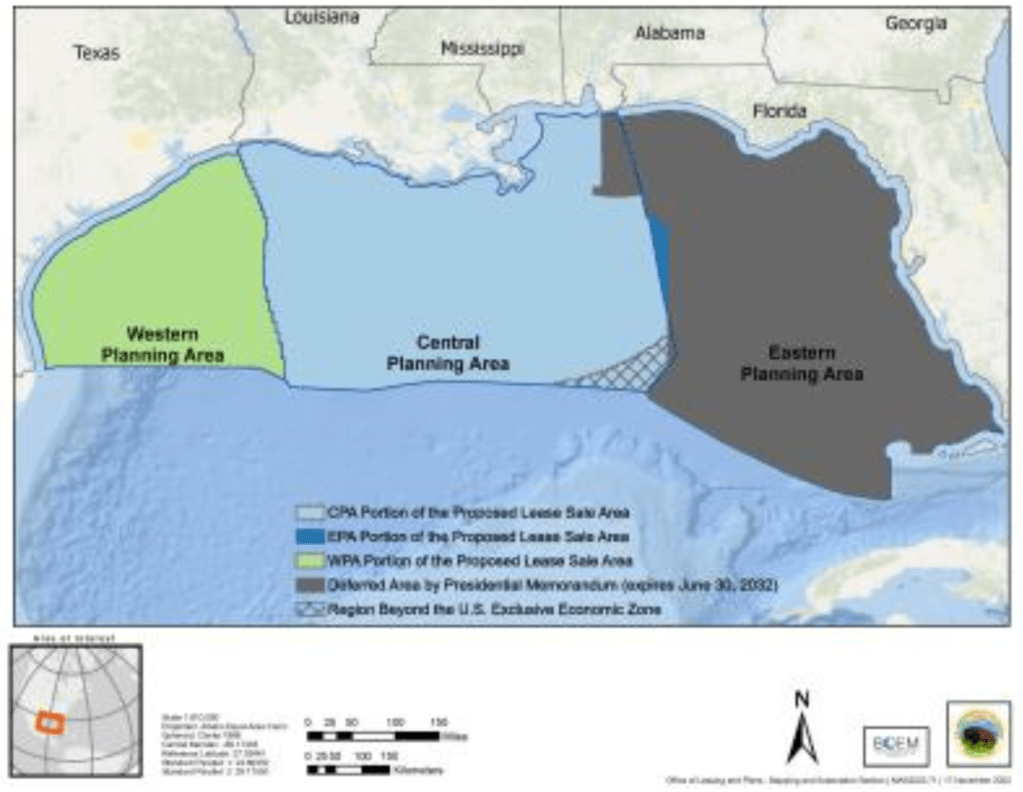

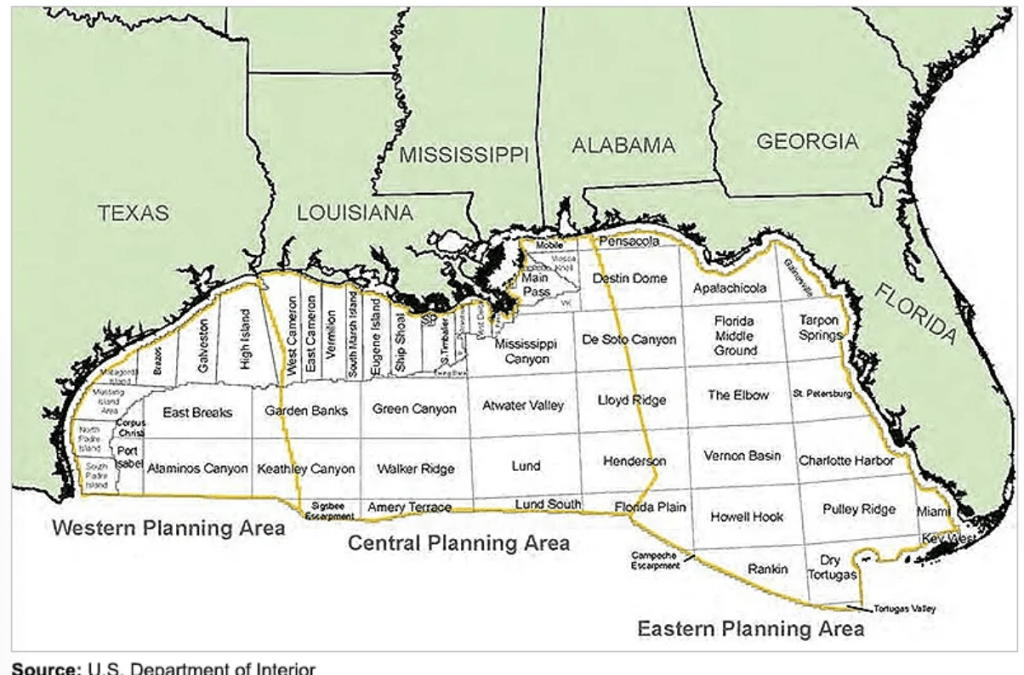

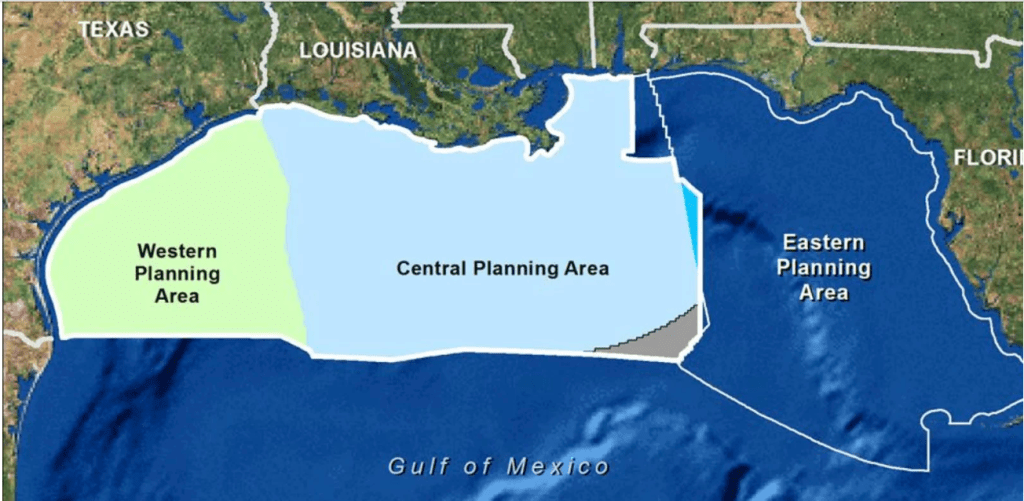

For Doug Burgum had long fiercely defended of the mining of fossil fuels and minerals form the national waters, less we loose energy dominance to those autocratic nations–not only Russia, China, and Iran, but Venezuela. And a demand for hemispheric energy dominance underlay remapping the submerged lands south of the border as the Gulf of America–the name change remapped national wealth. For Burgum hinted that the body of water that is one of the basins richest with energy reserves and hydrocarbons in the world with might provide the “foundation of American prosperity” if leases sold quickly to the highest bidder to lease lots to whole and partial blocks of the 94 million acres of the Gulf of Mexico’s ocean floor–although the vast majority of oil produced in the Gulf from 2018 had come from its central region.

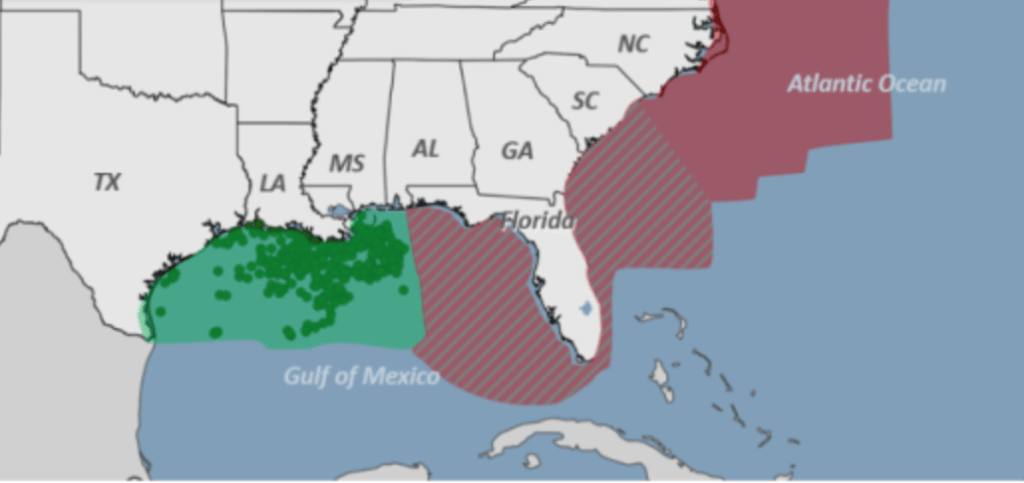

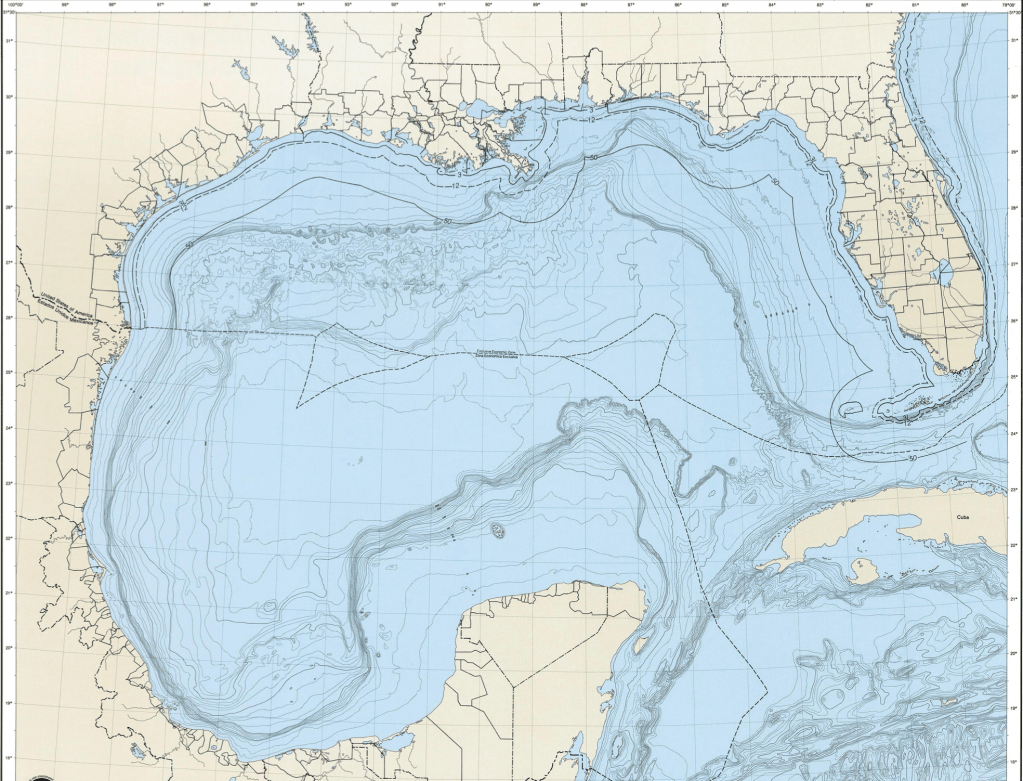

United States’ Sovereign Waters in Gulf of Mexico, 2024

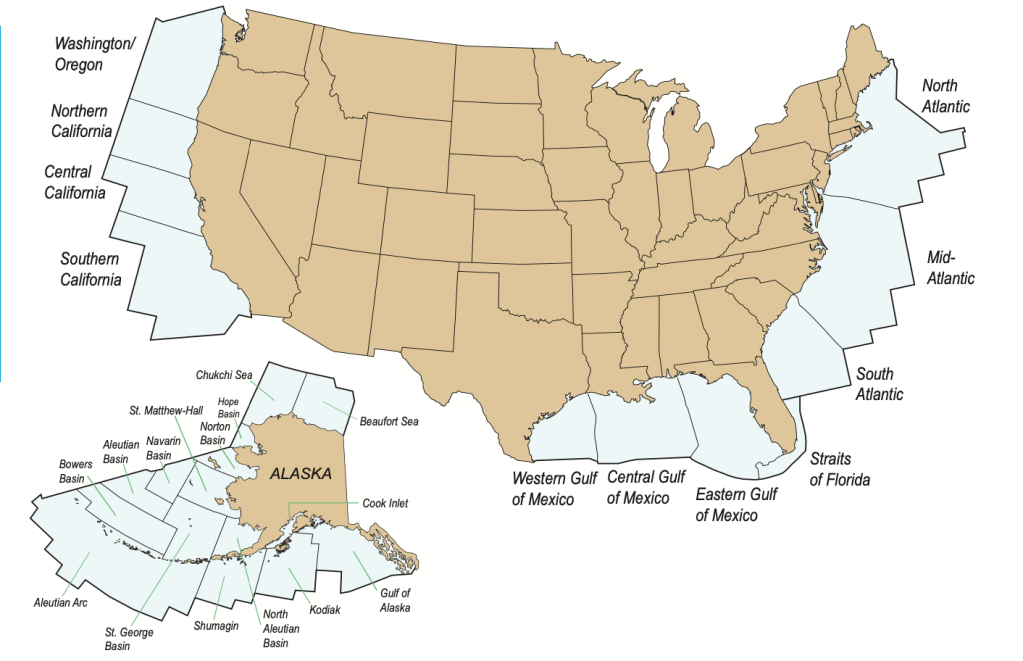

If the Biden administration had auctioned off only 1.6 million acres of waters in the Gulf of Mexico in its last public auction of thousands of individual blocks, entirely in the Western and Central Planning Areas, on the Outer Continental Shelf, the hope to expand the leasing of oil and gas reserves into the entire Gulf south to dramatically expand the wanted to expand their claims to the 73-3 million acres of waters–apparently believing that the opening up of such a windfall would not lead to an energy glut. If Biden had used the moneys from the sales to direct them toward conservation and mitigation of the effects of further offshore drilling on the region, reserving leases from the Eastern Planning Area and Florida shelf–withdrawing areas of the Outer Continental Shelf from being new leases for drilling and offshore oil and gas prospecting.

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, 2024

The shift in naming the body of water was about discovery–not of America, but of the deposits of minerals and hydrocarbons that would be mined in the Gulf, off the shores of four gulf states, presumably not limited to the Exclusive Economic Zone administered by the Department of the Interior, that interior secretary Burgum, promised he would recognize as part of the country’s “balance sheet” and assets, that the former Governor of the landlocked state of North Dakota who would lead the National Energy Council described as the nation’s assets, which belonged, “surface, subsurface and offshore” worth upwards of $100 trillion–a Trumpian hyperbole rooted in remaking government as a business. Scott Burgum had demanded a federal assessment of the value of oil, gas, timber, and minerals in the United States and its waters–seeing the role of the a tally as financial, and easily monetized, more than in terms of stewardship or best practices of conservation–notions that seem entirely foreign to his modus operandi,–even as he blithely ignores that the value of petroleum nestled in submerged waters is not a static good to be monetized, but based on petroleum demand.

Yet the premium on unleashing the full potential value of federal lands was revealed in Burgum’s quick declaration of a National Energy Emergency to encourage oil and gas exploration in lands and waters and on the Outer Continental Shelf. Following the American Petroleum Institute’s demand for an “energy-secure feature,” the sanctioning of extraction in one of the richest hydrocarbon basins of the world, with estimated hydrocarbon endowment far exceeding the national debt, may commit the U.S. to long-term fossil fuel dependency and greater carbon emissions But by expanding the waters over the which the government exercised sovereignty, the White House is keen on erasing the words “Gulf of Mexico” from the geographic maps of the federal government,– and effectively remapping waters administered by the Dept. of the Interior beyond previously negotiated marine borders, scrapping international treaties to for the tally of mineral and energy wealth Burgum, as a relentless champion of massive energy pipelines and Big Oil’s trusted ally in the Trump administration, advocated, and as leader of the newly created National Energy Council, gained enhanced powers of energy policy as well as control over leasing lands in the Gulf. (Burgum stands to redefine the interior secretary’s role; he has promised to reverse Joe Biden’s reduction of offshore mining in favor of environmental conservation, advocating “energy dominance” to reflect the annexation of the Gulf of Mexico to the lands leased by the Dept. of Interior in place of the conservation or protection of coastal environments recently prioritized by previous lease sales.)

Naming was not only a performative exercise, but was a celebration of the remapping of sovereignty over the submerged lands in that body of water. For the renaming of the3 body of water entitled the Dept. of Interior to sell further submerged plots, increasing, if you will, the liquidity of the resources underneath the current Gulf that is already the United States’ most productive region of oil extraction and gas mining, whose lease operators extend far offshore to the limits of the territorial water marked above bye a purple line, extending the US-Mexico Border.

The expansion of offshore commerce that runs through some 26,000 miles of pipeline is already a market for energy industires. And although the victory being celebrated in the Brady Press Room was virtual–as we’ve become accustomed-it was also almost mythic, and very tangible in its economic benefits as a claim of hemispheric energy dominance. For it was a calculated move of renaming that the renaming of the region was a leverage to gain energy dominance, monetize the leases of offshore lands in something akin to the Sovereign Wealth Fund he has long promised–a fund more typical of creditor nations as Saudi Arabia, Norway, China, Kuwait, or Alaska and Texas–the Gulf of America would provide, by renaming the offshore waters as part of the nation, and extracting the seafloor–“Drill, baby, drill!”–to unearth hundred of trillions of newly discovered assets, reducing the current national debt of $36.22 trillion in a single gesture.

Executive Order Creating United States’ Sovereign Wealth Fund, February 3, 2025

Would the renaming of the Gulf of Mexico suddenly only allow the United States to create a sovereign wealth fund of its own–which Trump had declared his intent in February 3, less than a week before he declared the name of the Gulf of Mexico to be expunged form federal maps in the Geographical Names Information System (GNIS)-and ten days before declaring the name change from the White House. As much as changing a name, or an exercise of vanity, or a foolish branding attempt, the interested nature of renaming was one of remapping– affirming the manifest destiny of expanding our frontiers as Trump had promised, reviving the Great Frontier as a platform in the party of Make America Great Again, under the guise of exercising energy domination and a way to “amplify the financial return to a nation’s assets and leverage those returns for strategic benefit”–even before any sovereign wealth was extracted from the submerged lands off off the Gulf states.

Trump Speaking at White House after Signing Executive Order on February 13, 2025

The point was not only to increase the appearance and dominance of the word on the world map. What was this renaming of the Gulf of Mexico but a distillation of MAGA? The meeting of MAGA and the United States of Amnesia was every more on show, with the erasure of a longstanding point of reference for American cartographers abolished from the register of geographic names. What of the early teaching maps of the 1820s, that promoted a vision of “Universal American Cartography,” but had noted the “sources of the Mississippi, 3038 m. above the Gulf of Mexico,” or even mapped the nation against that body of water in 1805?

Thomas and Andrews, 1805

“Sources of the Mississippi, 3038 m. above the Gulf of Mexico,” in Morse’s School Geography, circa 1820

Even before the Sovereign Wealth Fund began to fill its coffers, it became clear that doing so from submerged lands in someplace named the Gulf of Mexico wasn’t clearly the best idea. But the name change mapped the region’s as part of the nation’s own sovereign funds, to maximize American wealth and promote American leadership for “greater long-term wealth generation,” by language seemingly exported from Business School distilled into a simple name change–and indeed by symbolically placing the White House, if in reduced form, squarely in the Gulf of America, as if on a game board. Indeed, the Gulf was no longer simply a body of water, as it was historically mapped with the name “Mexico”–

–in the West Indies, but instead an extension of the patrimony of the state, and a seat of sovereign wealth, ready to be “discovered” and claimed by Donald Trump for American’s future redemption.

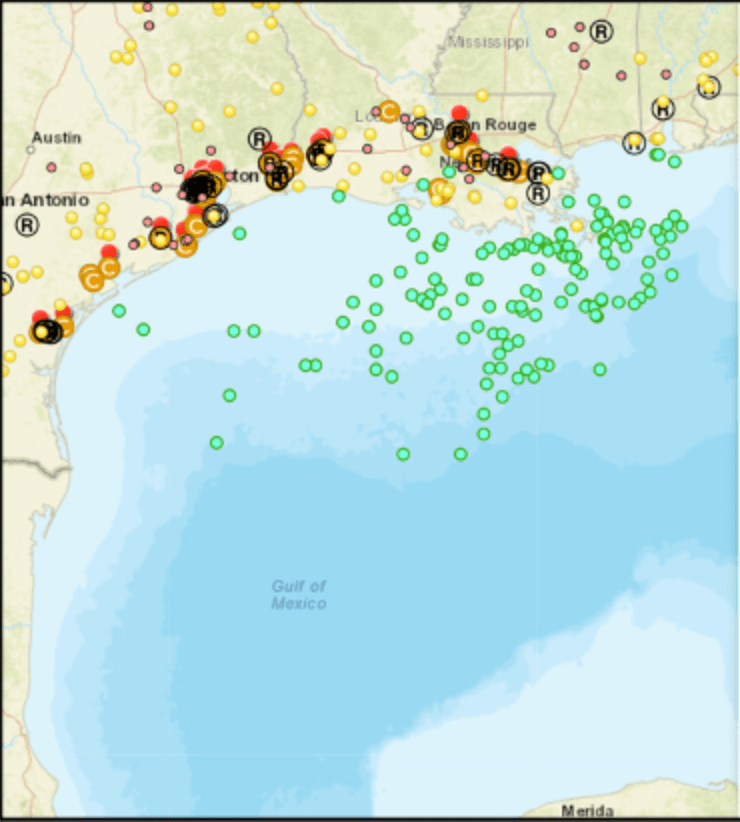

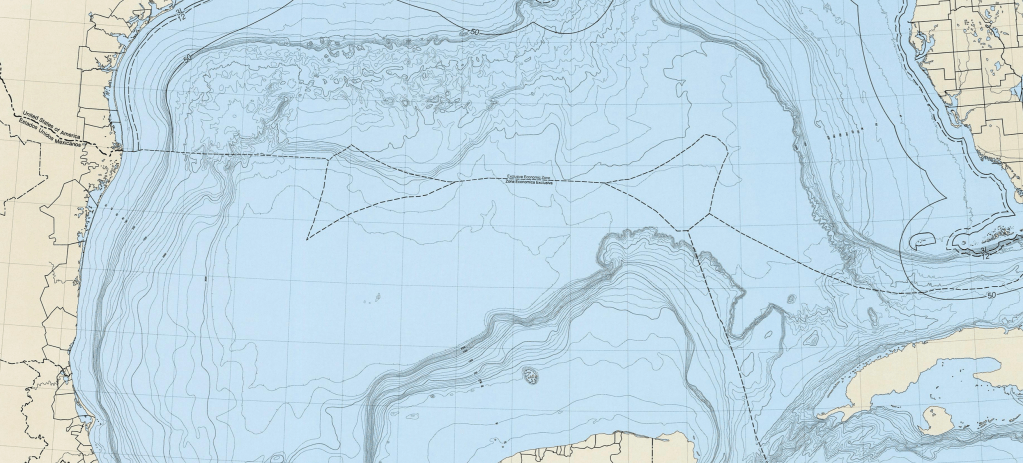

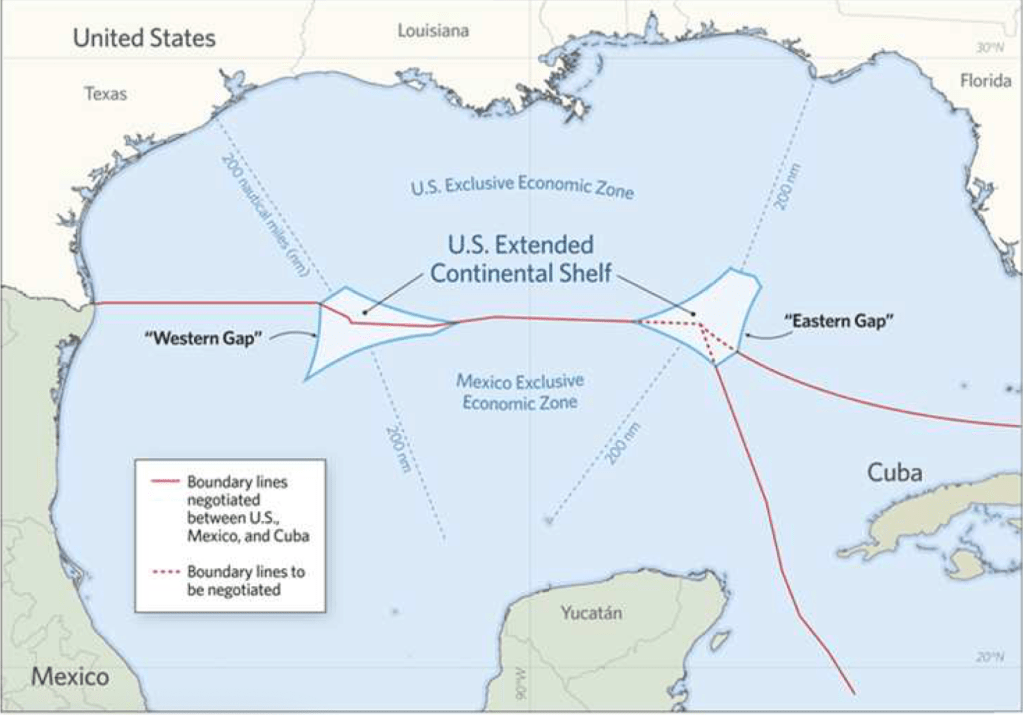

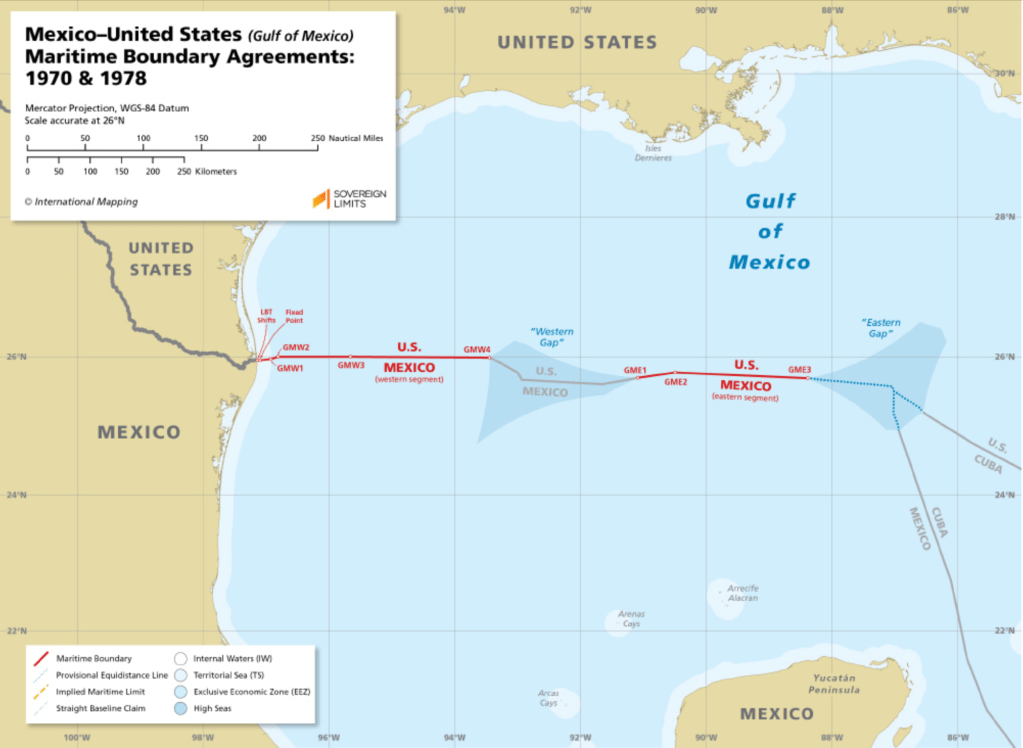

The apparent victory to enforce a change in newspapers’ style sheets was a combination of Manifest Destiny and lebensraum, a shift in cartographic terminology that challenged the Law of the Seas that had sent a clear maritime boundary between the United States, Mexico, and Cuba. Did the name refer to those part of the Gulf of Mexico within the EEZ, that extension of the international border that stretched across the Gulf of Mexico, outside North America’s Outer Continental Shelf (OCS)–

Gulf of Mexico, Political Boundaries and Maritime Zone

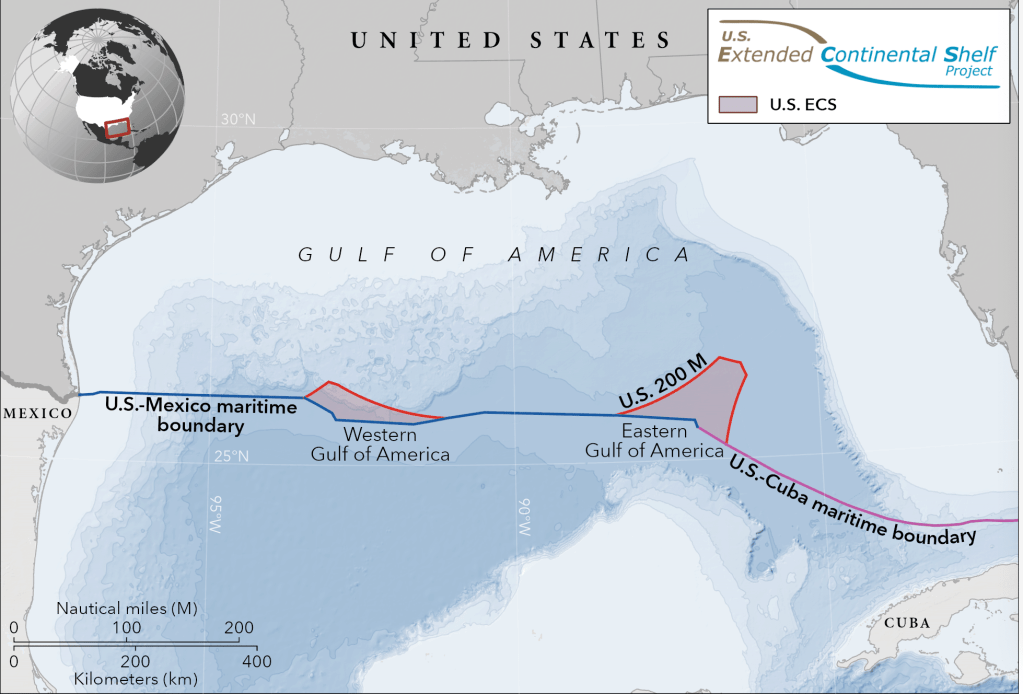

–or to waters within the Exclusive Economic Zone, the region over which Joe Biden had halted offshore oil and gas leasing in 2021, only to be reversed by a federal court order? And even as the Extended Continental Shelf had expanded what were argued to be American submerged lands and waters–expanding the land claims quite significantly beyond the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the nation, by about a million sq km, per a new finding that quite dramatically expanded “the extension of a country’s land territory undersea, the expanded underseas regions of the Gulf of Mexico lay in a body of water that was distractingly named after another nation.

“Extended Continental Shelf Project,” U.S. State Department, 2023

It wasn’t at all clear, but not much was, given the boosterish and downright expansionist MAGA rhetoric of previous weeks. Was the international boundary line to be respected? It was unclear, but the boundary seemed less the point than the name-change that extended across the entire body of water, if NOAA still notes the EEZ as a continuous extension of the international boundary line, but Trump seemed to erase reference to the Gulf of Mexico at all, and was victorious in preventing those reporters working for news organizations persisting in referring to it from access to briefings, as if he had won victory over the entire Gulf, by symbolically and linguistically annexing it to the nation.

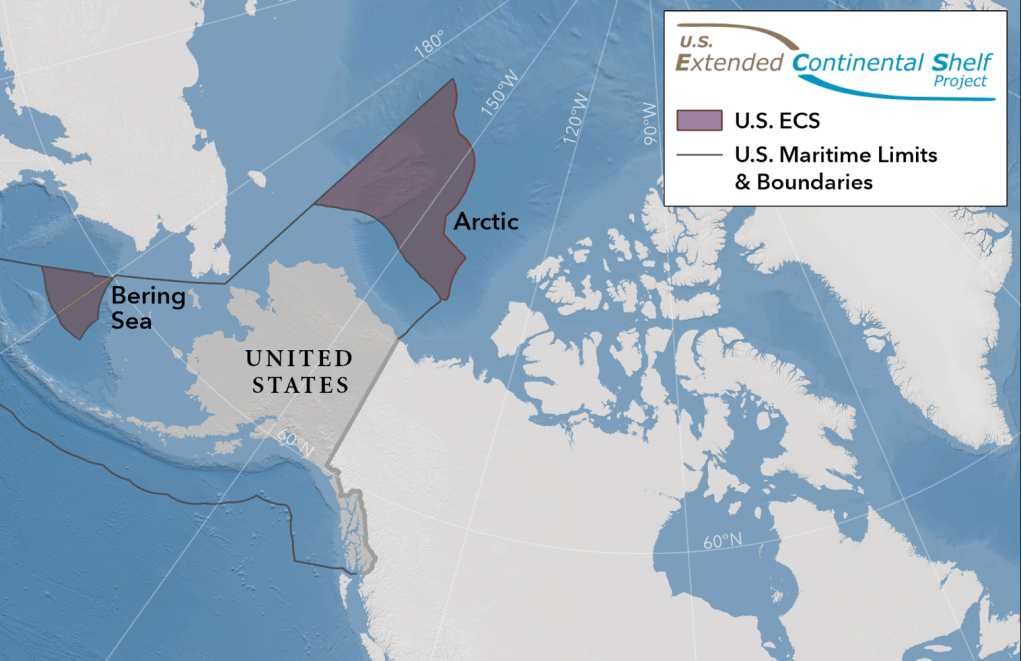

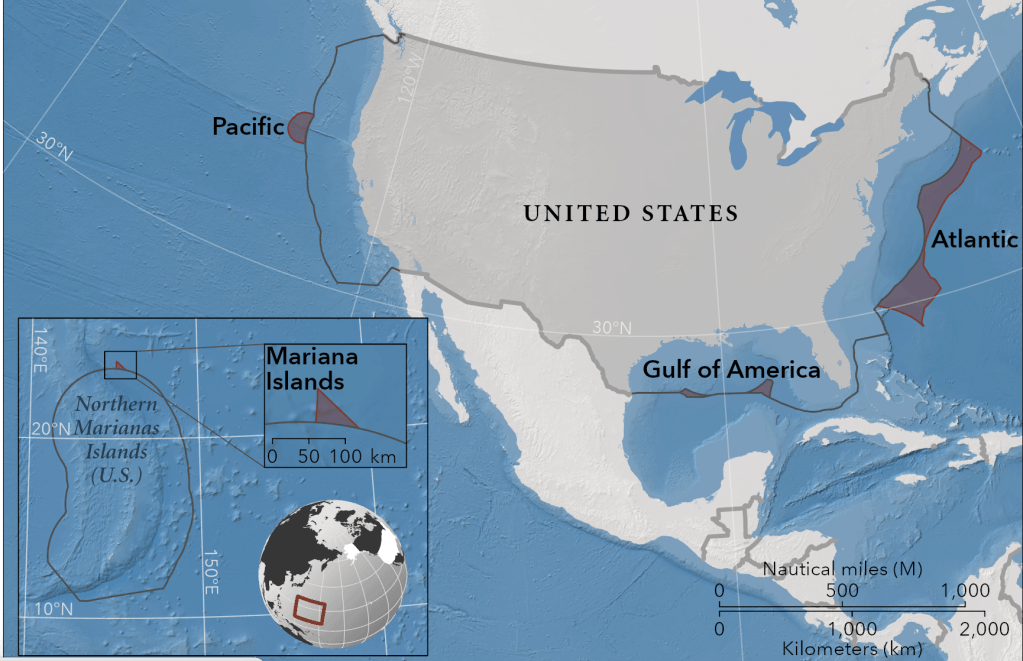

Indeed, the ongoing redefinition of “open seas” as maritime seabed that extended beyond the accepted perimeter of the continental shelf had not only grown around the nation by the long-term remapping of the submerged seabed of the Gulf of Mexico–as well as the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and the Bering Sea–but promised a new grounds for extracting hydrocarbons and mineral wealth. After a master project of the remapping of the American shores and offshore perimeter, at a cost of tens of millions, a twenty year project of mapping the continents submerged edges or shelf had concluded in 2023, after twenty years, hoping to exploit these reclaimed underseas mineral and petroleum resources by claiming them within the jurisdiction of American territoriality–the fruit of longstanding resistance of Republicans since Ronald Reagan in rejecting any limitation to seabed mining the restriction of American sovereignty to two hundred nautical miles posed. And despite negotiating the United Nations’ Law of the Seas (UNICLOS) in the 1980s, the United States remained outside that convention lest it pose a “dangerous loss of American sovereignty,” as the Heritage Foundation warned in 2024. Remapping the Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) not only expanded the lands over which the nation claims sovereignty including trillions of dollars in mineral wealth.

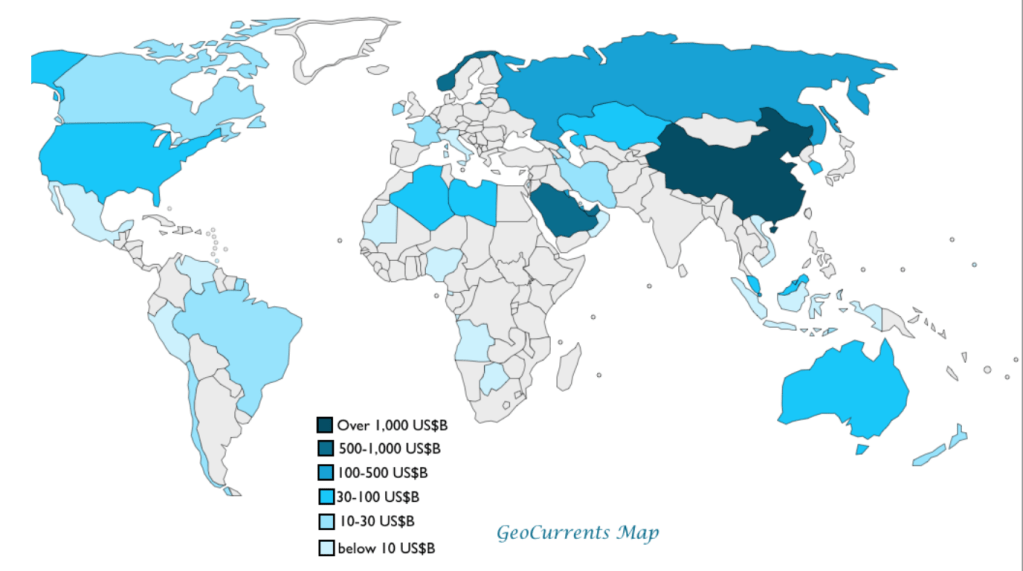

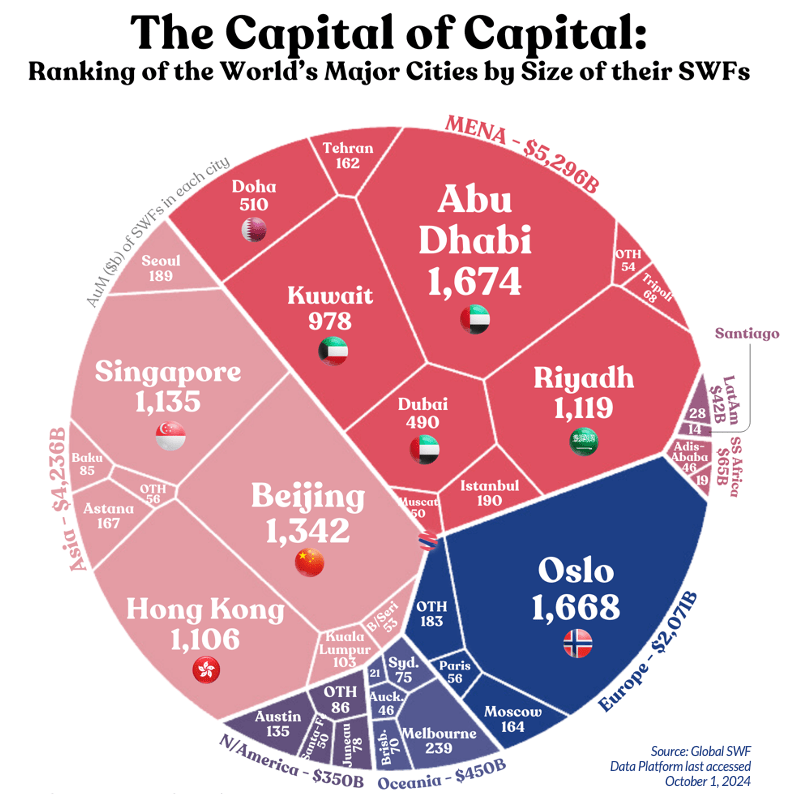

Remapping the Gulf of Mexico as American reflected the enlarged territoriality of the Extended Continental Shelf–not the OCS–seems a gambit to bolster sovereign wealth in ways that would create Trump’s vaunted Sovereign Wealth Fund, akin to Saudi Arabia, the Emirates or Kuwait–a race China leads by far, at $2,750 Bn, not far ahead the United Arab Emirates, at $2304 BN, Singapore’s $2,074 BN, or Saudi Arabia’s $1,345 BN–based on oil and gas and minerals on public lands–or the diminished place of the SWF’s of American cities in a new global map of wealth.

Geo Currents (2012)/Martin W. Lewis

Global Cities Ranked by Sovereign Wealth Funds, October 1, 2024

Was this infographic of sovereign wealth, recently promoted by Global SWF in Abu Dhabi in ways that promoted a new map of moneyed global cities, the “Capital of Capitals,” been able to provide a basis to boost the presence of American cities on the map–confined here to Austin, Santa Fe, and Juneau–by declaring the Gulf of Mexico part of the future Sovereign Wealth Fund of the US? Would not the prominence of Oslo–Oslo?? Singapore?? Hong Kong??? Seoul???–have inspired an anger in Trump’s vainglory, independently from the venting that the prominence of Teheran? A deep sense of competition, as much as of global markets, has no doubt fed the vision of the Sovereign Wealth Fund for the United States, even if the realignment of national power and industry goes against Alexander Hamilton’s vision for the United States as a sovereign state embodied in a bank.

Trump must have been particularly sensitive to the redrawing of wealth in a map of global power, in which Austin, Santa Fe, and Juneau were removed from any central role, as Abu Dhabi appeared as outside dominance with Riyadh, and Oslo and Beijing were a close second: one could not even see the American flag, in the range of Saudi, Kuwaiti, Norwegian and Chinese flags fluttering on that map. America was perhaps a late entrant into the world of state capital–and the concept of state capital foreign to the separation of the state from markets, and national wealth from the GDP.

What would an American Sovereign Wealth Fund, akin to the Saudis, Norwegians, Emirates, or even China, look like? The project of remapping of the Extended Continental Shelf had been long in the works, and offered something of an idea dear to the Republican Party and a give to energy lobbyists since the Reagan years. In contrast to UNICLOS, the surveying of submerged lands has been promoted as a key to energy dominance to secure national rights to drilling beyond the marine border. Rather than set limits on the offshore areas of which nations exercise sovereignty to two hundred nautical miles, energy lobbyists long agitated government for the expansion of the United States’ territorial waters, as Ronald Reagan dragged his heels on a Convention for a Law of the Seas as being in national interests. Did MAGA offer a chance to rehabilitate the idea?

The wealth in submerged waters was long on the back burner of revisionary images of sovereignty. The American Heritage foundation dismissively calls UNICLOS as “a fatally flawed treaty,” to which the United States should never be party. For its circumscription of territorial waters only boded a radical curtailment of American sovereignty as unduly compromising national sovereignty and wealth. Recent estimates by BOEM that 25 billion barrels of oil and 124 trillion cubic feet of natural gas lie in the extended continental shelf of Alaska, an estimated 4.87 billion barrels in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico, recently protected from leasing to offshore drilling for oil and gas, provided the keys to extract sovereign wealth. Despite the recent 2006 moratorium on drilling offshore by the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act, untapped resources of the outer continental shelf provided a potential windfall if restrictions on offshore oil drilling could be reversed. Would waving a cartographic magic wand of nomenclature to remap America’s bountiful “natural” offshore wealth free the region from environmental monitoring, helping open natural gas reserves in the Atlantic of an estimated 32 trillion cubic feet? Opening a door to a renegotiation of boundaries of national waters with Mexico and Cuba suggested a new horizon of energy production, eclipsing hopes for international investment and transnational cooperation drilling for gas and oil in a Gulf of Mexico?

If all maps elide nature and culture, naming a region as if it is naturalized in the mind’s of the viewer, this act of renaming was a means of censorship, if not of mind control, a wishful reality born of truthful hyperbole, a remapping of the nation that was the fruit of twenty years of surveying and mapping the Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) of the nation, from 2003 to 2023, when the new coordinates of national waters beyond the two hundred nautical miles from the coast, but their repackaging and rebranding were staged-managed by a Pitchman-in-Chief. The renaming was a willful remapping–a massive monetization of the gulf waters to enhance “sovereign wealth.”

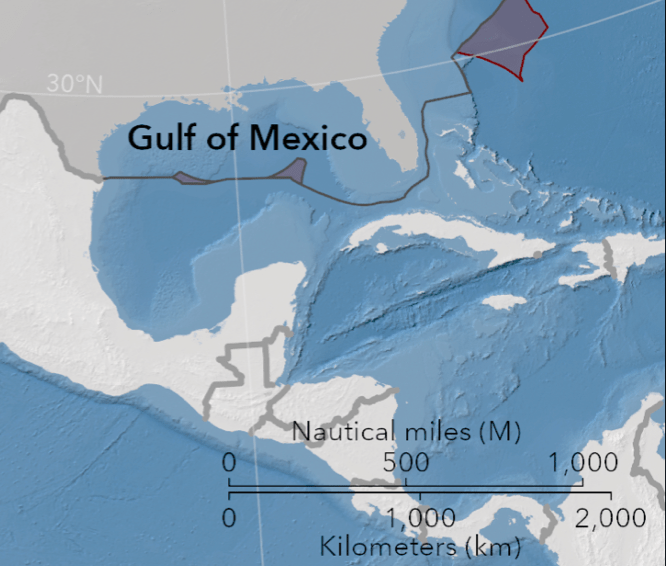

Gulf of America in Regions of Extended Continental Shelf/U.S. State Department, 2025

If you wondered whether the Gulf of America would be taught to your kids in elementary school, or marked on school maps, you were not wrong: the new imaginary of the nation provided an immediate expansion of the “wealth” of the nation, potentially erasing a monumental debt by the expansion of the United States to a full seven “offshore” areas–in the Arctic, Atlantic, Bering Sea, Pacific, Mariana Islands, and the newly named Gulf of America. The radical remapping of ocean waters as submerged lands stood to expand American territoriality limited by a million sq km, or about twice the size, as the State Department boasted on its website, of the state of California–a million sq km–comparable only to the doubling of the United States by the Louisiana Purchase for a mere $15 million, stood to expand national territory, the ten million of remapping national waters grew the land by a tenth, and potentially avenue to erasing its mounting national debt. The waters of the gulf were not imagined as waters, in other words, or as “offshore,” but as a site of extraction. The “Gulf of Mexico” was no more, as the deepest waters of that body of water were included in American sovereignty, and open to leasing to oil and gas industries, by unleashing them to “drill, baby, drill.”

In contrast, the underseas enlargement of the United States would rewrite and supersede previous definition of a division of the Exclusive Economic Zone–to include the “gaps” that would be outside American Jurisdiction in a treaty negotiated in 2000–and indeed reveal an extremely broad geographic shelf that extended into the erstwhile Gulf of Mexico.

Rather than set aside two pockets beyond national waters in the Gulf, as the 2000 Treaty affirmed–the expanded Extended Continental Shelf not only had added 30% to waters and submerged lands claimed under American jurisdiction, as two pockets of the Gulf formerly known as “of Mexico” optimistically described as adding up to the size of Kuwait were declared part of the expanded continental shelf outside the 200 nautical miles from shore within American sovereignty–

Detail of Dividing Line between Exclusive Economic Zones in Gulf of Mexico/NOAA

–naturalizing two “gaps” of deepwater exploration as now belonging the Gulf of America, and open to energy prospecting.

For the real triumphal map of the “Extended Continental Shelf,” a project that the United States government had invested since 2003 and the administration of George W. Bush, directing NOAA and USGS to amass data beyond the existing Continental shelf of the nation, to expand the existing maritime boundaries by geophysical surveys of the basin’s floor, and the surrounding seafloor, was an attempt to give “hard edges” to claims to American sovereignty, over-riding any government mandate for coastal protection, coastal restoration, or habitat renewal, emptying conservationist language of its logic–by twisting or nudging the “rules” and margins of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Seas (1982) to revise that map in order to promote national interests, rather than international consensus. Since theUnited States asserted its own jurisdiction over natural resources on the continental shelf off its coasts in 1945, the expanding margin of national sovereignty has been radically extended, in order to benefit extractive industries, first expanding them in 1953 to the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) and now pushing that a bit farther into the oil- and gas-rich basin mapped below. The new data and documents–reflected in the map below–

Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) in Gulf of Mexico, 2025/State Dept.

–offer a new understanding of sovereignty in the age of globalization, and a new basis to expand not only sovereignty but, more importantly, sovereign wealth, in an age of increasing isolationism, to push the neoliberal doctrine of public-private partnership into new unexplored waters. While created, quite perversely, by the very scientific institutions that the Trump administration wants to downsize and diminish, their job for sovereign mapping done, the revised continental margins delineate the “outer limits” of the extended shelf, amassing 18,100 sq km in the Gulf of Mexico’s waters as part of the sovereign territory, mapping the basin by state-of-the-art multi-beam echo sounders to trace the bathymetry of the basin for national use, remapping seafloor and sediment in the Gulf that seek to resolve “unresolved maritime boundaries” that are cast as existing boundary disputes, not only with Mexico and Cuba, but, all of a sudden, Canada, Japan, the Russian Federation and The Bahamas, resituating the United States within global oceans.

But don’t say we weren’t prepared. Trump had promised he would restore a once “integral asset to our once burgeoning Nation” into “an indelible part of America,” as part of his Presidential effort to move mountains (and oceans) to Make America Great Again. And by “reinforcing . . . the lawful geographic name change of the Gulf of America,” as he declared while flying over what was for the pilot of Air Force One the Gulf of Mexico, he bleached the map of the name of the largest body of water that was in fact of Nahuatl origin, as if to purge the map of indigenous presence and not be a mirror of American grandeur.

After being alerted that the Associated Press, a venerable organization, would keep the traditional usage, access of journalists and photographers who were not ready to embrace the name change were immediately revoked to the Oval Office, and Air Force One and Press Briefing Room. After January 20, the servers of both Apple Maps and Google Maps acquiesced in naming greatest body of water in North America “Gulf of America,” but the impudent Associated Press had retained the older usage, meant their access was ended. The new name that replaced the Gulf identified in early navigational maps provoked to a rush to map libraries for the earliest naming of the Gulf by a name of Nahuatl origins in a printed cartographic record of 1550–two centuries before the United States was ever imagined or mapped. But the renaming echoed the name of the Renaissance cartographer, Amerigo Vespucci–whose name is tied to the first naming of the continent–as a way of taking possession of these waters, increasingly sites to stake American hopes for energy independence in fluctuating energy markets of a globalized world, after an election where the promise of lower gas prices led to a sizable share of his electoral report. The President made his pitch to rename the region from cruising over the very body of water, as if from a a God’s Eye view of Air Force One.

Trump Beside Map of Gulf of America in Air Force One/courtesy of the White House

Trump staked a pitch of his Presidency on television while in flight over the Gulf of Mexico, addressing the nation to announce its new name. The act of renaming met by bemusement among residents, but the pitch was not only to Gulf states’ media markets. While flying to the Superdome to the “showdown” of Super Bowl LIX. Indeed, the first sitting President to attend the popular American sporting even posed for the cameras before a map that foregrounded the Gulf States’ reaction to the body of water, proclaiming the renaming to be “even bigger than the Super Bowl” as if it were a major media event and a pitch for his own leadership.

Trump had directed attention to a portion of the former Gulf of Mexico to celebrate the region’s “pivotal role in shaping America’s future and the global economy” on February 9, but the claim soon mutated to expand to repatriating not only the coastal waters of the Gulf on what was henceforth to be celebrated as Gulf of America Day,–to rename the entire body of water, by obliterating any reference to the Gulf of Mexico in state records, pressing ‘Replace All’ in the national cartographic database: the Gulf of Mexico for American purposes simply didn’t even exist as he flew over it. The survey of submerged mineral wealth Burgum felt was a to-do list for the nation, one felt, was not far behind. Was the very image of the different sovereign wealth funds on the map–and how tragically behind the United States lagged–if only Norway, China, and UAE were securely over $1Tn–funds in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana already existed, that might be transferred from some magic over the unleaded oil and gas deposits in the Gulf of Mexico.

Displaying the declaration of the Executive Order beside a map as he traveled over the Gulf, Trump affirmed the proprietary role of the United States to the Gulf as a body of water–though most of the former Gulf of Mexico lay outside its national waters. Perhaps the revelation of the map while he traveled over its waters was a model of taking possession over its submerged lands. The poster was if nothing else a pitch to unlock the riches of oil and gas that lay in submerged lands of the United States was an act of deception and a watering down of the truth–the body of water wasn’t administered by the President or Dept. of Interior, but the Bureau of Land Management had been conducting a brisk business leasing out plots in sectors of the water to extractive corporations, and Trump wanted the auctioning off of leases to extract oil from submerged lands to only expand. The ownership seemed something he was able to claim, and then wait to see how it was adopted, as if throwing spaghetti at the wall as he had on January 6, 2016. The remapping of sovereignty was on the front burner of the Trump administration, eager that “the United States once again consider itself a growing nation — one that increases our wealth, expands our territory . . . and carries our flag into new and beautiful horizons.” This was not rebranding, but mapping as national therapy.

The debut of the infographic renaming the offshore waters affirmed the commitment of January 20 to extend the boundaries of the United States. The proclamation of “Gulf of America Day,” remapping the region formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico to recognize it has” long been an integral asset to our once burgeoning Nation” as a truly “indelible” part of it, linking the water to the land once the ink dried on his signature of his Executive Order by a cartographic prop. The Graphic Names Information System (GNIS) quickly replaced all reference so the Gulf of Mexico in the official federal database of all US geographic names, expunging all references to the Gulf of Mexico, so that it ceased to exist on any maps–and presumably henceforth changed the name of the entire body of waters from the point of view of the United States government. Would reality keep up was the only question that remained.

The fulsome boast for inaugurating a new world view, and abandoning the name used in sixteenth century globes, celebrated on February 9 “Gulf of America Day,” was deflated after AP executive editor Julie Pace revealed they were not changing their style sheet. Trump threatened that if AP “did not align its editorial standards with President Donald Trump’s executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America, AP would be barred from accessing an event in the Oval Office,” starting a shit-show more about Freedom of the Press as much as Freedom of Speech, and imposing a new world view on the United States. As Trump’s Press Secretary sought to disabuse journalists in the Briefing Room that they should expect the right to enter the Oval Office or Air Force One to be extended as a matter of course, the question of who should have the right to a Green Card, and whether the Green Card could be seized by criminalizing political speech, and didn’t include protections of Free Speech, even if there Constitution prevents any abridging of Freedom of Speech by Congress in any way, suggest the contingent nature of freedoms, green cards, visas and speech through Executive Orders, as if the Executive Order had priority to settled laws.

Did this tempest mark the superrcessioc of online v. print cartography, as the mandating of a name on map servers that might trickle down as a tool of mind control throughout the national consciousness? What sort of assent would this simple name-change command, and were such name-changes expected to be de rigeur in a world where maps commanded and demanded consent? Were we approaching the world of Oceania? Or was it not a truly Orwellian maxim ‘Freedom is Tyranny,’ a cognitive tool tying Gulf to Nation that wormed its way into citizen’s minds? If the name change was mocked at first, the flaunting of privileges of renaming bodies of water over the The name change of that body of water should be handled thru the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names, planed to convene from 28 April to the 2 May 2025 at the United Nations in New York, suggests that entering the name change when the Group of Experts is out of session cued the name change, even if it was more likely prompted by the urgency of a need for economic good news as stocks plummeted Perhaps this is ignoring the larger issue, however: for the name change was not only rolled out in a theatrical fashion in the Brady Press Briefing Room, but was preparation for rolling out a pitch of the expanded offshore areas of the “Extended Continental Shelf Project” that would be announced as open for extracting minerals and energy in the Arctic–