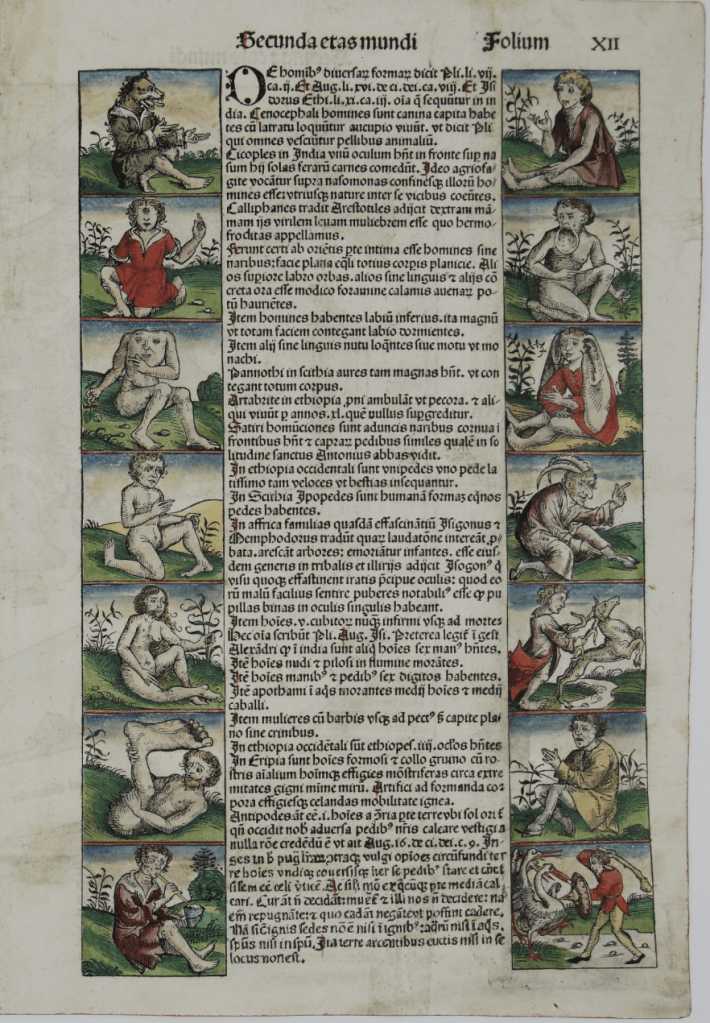

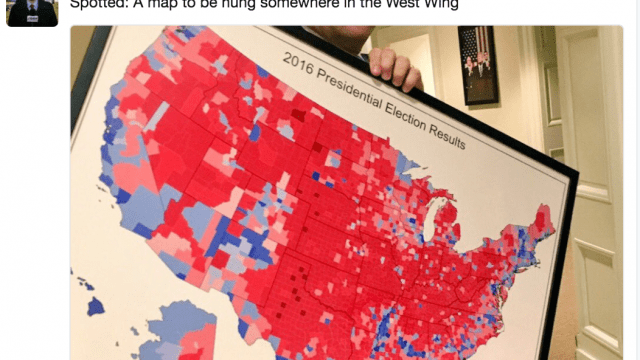

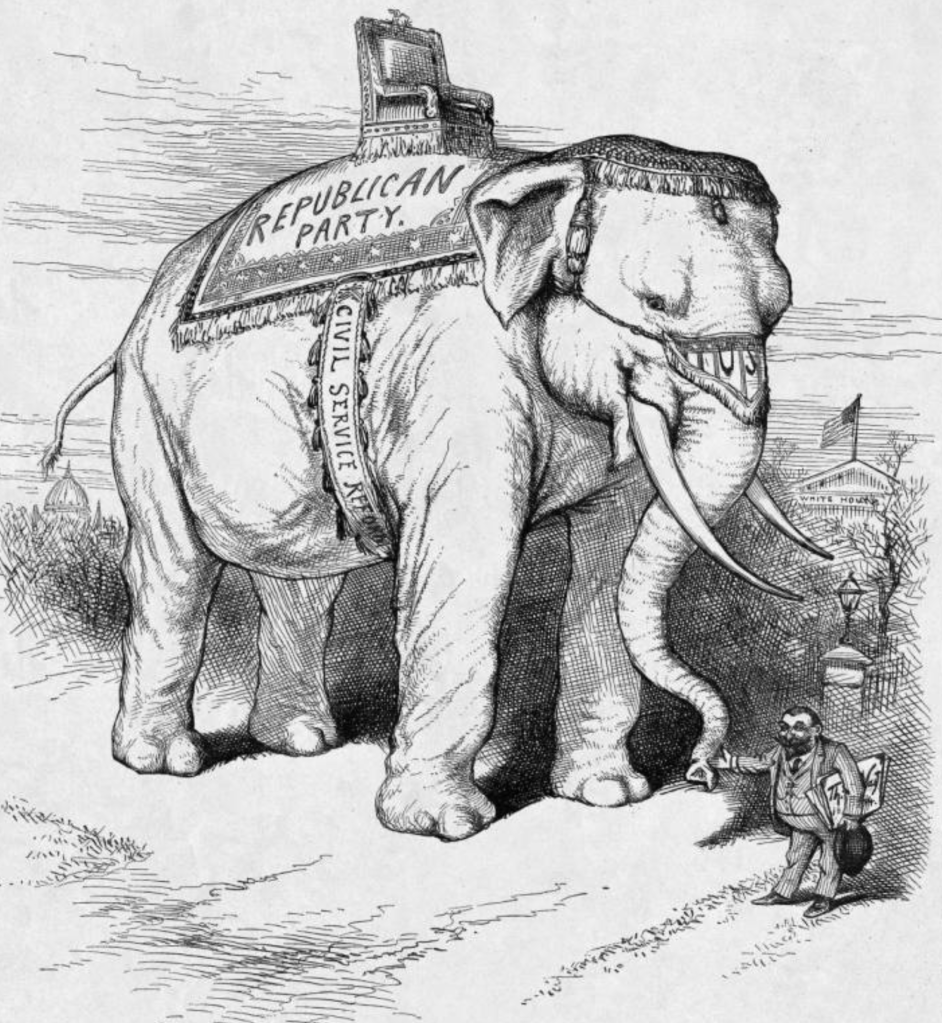

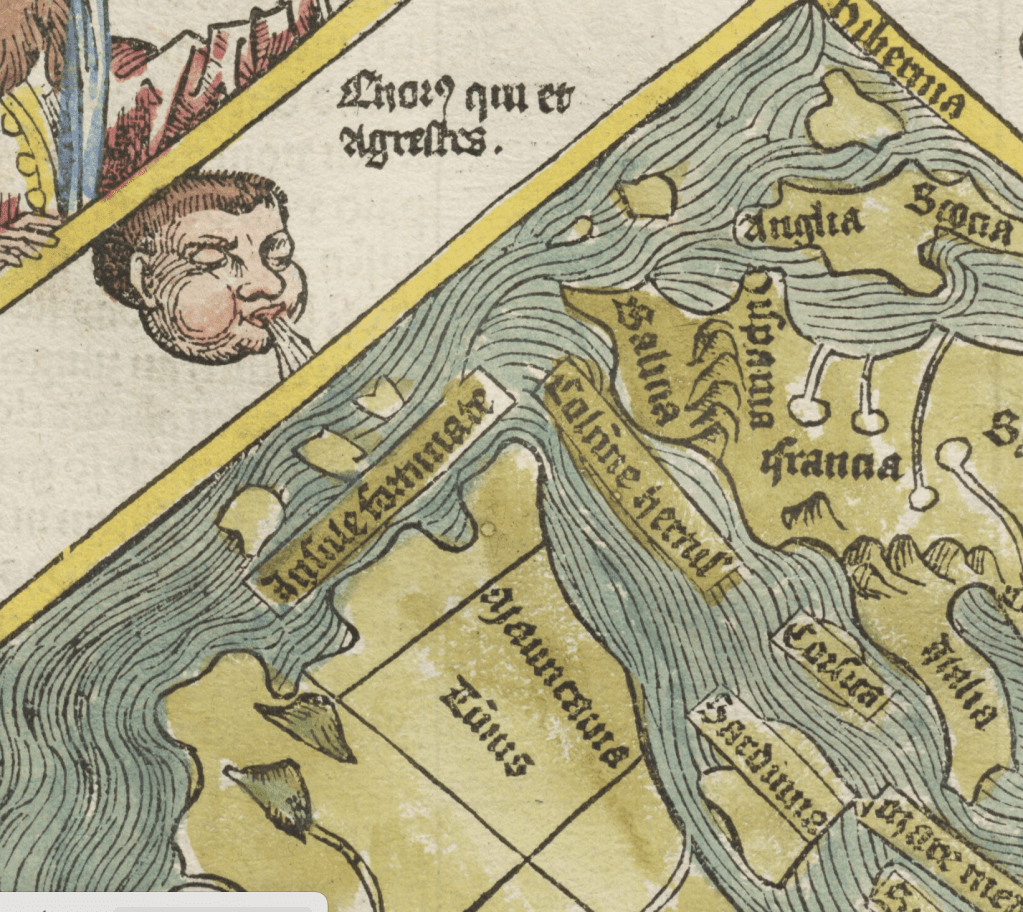

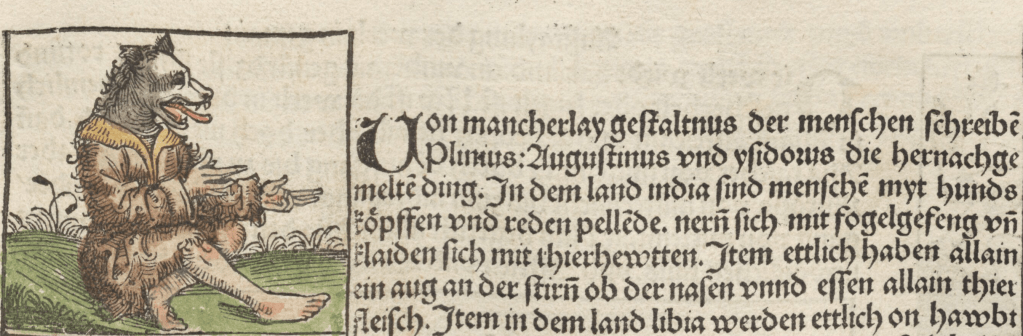

As non-human animals inhabited the edges of the inhabited world in medieval cosmologies, it may be unsurprising that the MAGA candidate who has done much to resurrect the contours of theocratic neo-medieval maps perpetuated stories of the consumption of pet dogs–the “pets of the people who live here”–as the latest hidden news fallen under the radar that he dredged up from the darker reaches of the internet. Donald Trump has long supercharged fears of migrants before the 2024 Presidential election. But the claim that Haitian immigrants who arrived illegally in Ohio were eating the pet dogs and cats of American citizens was a Hail Mary move of the 2024 election. As much as merely re-presenting the dark face of immigration unfurled as the banner of Trump’s 2016 Presidential campaign, delivered as he descended the golden escalator in Trump Tower, the fake news Trump was pedaling without foundation evoked an anxiety dating from the discovery of the New World, and the image of dog-headed men on the margins of comfort and of the inhabited world was registered in the first world maps,–not even intended to be truthful, but hoped to sell books that narrated a global history in the first age of the printed book–

Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

–as a facile combination of the barely credible that courted anxieties of the unknown. The telling combination of the cartographic and hysteric, announcing discovery of New Lands with evocation of monstrous races off of its margins, drawn from a repertoire of medieval mythology, by presenting the new worries of the Modern Age in circa 1493, featuring not only a range of fantastic creatures–from monopods, headless men whose mouths were situated in their chests, to creatures with a large single foot, but human-like creatures on the margins of the known with heads of dogs.

Monstrous Races on the Edges of the New World and Beyond, Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

And as much as the unfounded charges that Trump evoked in his bid to be U.S. President had a basis in law, or pretended to be grounded in fact, they trafficked in rumor and stereotype, drawn from the oldest anxieties of threats to stability and knowledge, myths of existential threats more than actual dangers, and a premonition of the baseless charges and illegal conduct and disrespect for legal norms that the Trump Presidency would encourage and indeed make its brand. While widely identified as from the internet, and quickly decried by local city authorities in Springfield as scurrilous, the outrageous charges held weight among all terrified to admit Haitians into the United States, as if an existential terrors to the American families that captured the charges of criminality and deviance identified with the immigrants accepted from below the southern border. The absurd claim was lent currency in the debate as valid evidence of the dangers migrants posed to residents of in the bucolically named Springfield, Ohio, was unfounded and without documentation. The theater of fear, and the theater of the unknown, was however the theater of American politics, at the start of a new Information Age stunningly removed from fact, but enmeshed in if not parasitic on maps.

But the imaginary dangers to “people who live there” have been accentuated, with brutal and compelling stories related to migrants retold to create a sense that the country is under attack, in ways that takes voters’ eyes off of the role that the United States might play to bolster regional security rather than build walls and deny asylum to migrants seeking to flee political persecution. In response to a question about immigration, the pivot to eating dogs was presented as evidence of fears that the twenty-thousand immigrants from Haiti in Springfield, Ohio, launched for all its absurdity as an attempt to resurrect fears of immigration across America, as a specter of the flouting of American values and identity across the border, and taking advantage of an alleged “open borders” policy that put America at risk: the arrival of even a small number of Haitian immigrants, even if the immigrants had boosted the local economy. The Haitians were seen as sites of deep anxieties of disruptions to normality, as dangers to personal safety, and as disrupting the all American family by the sacrifice of its pet–the friendliest family dog or cat–

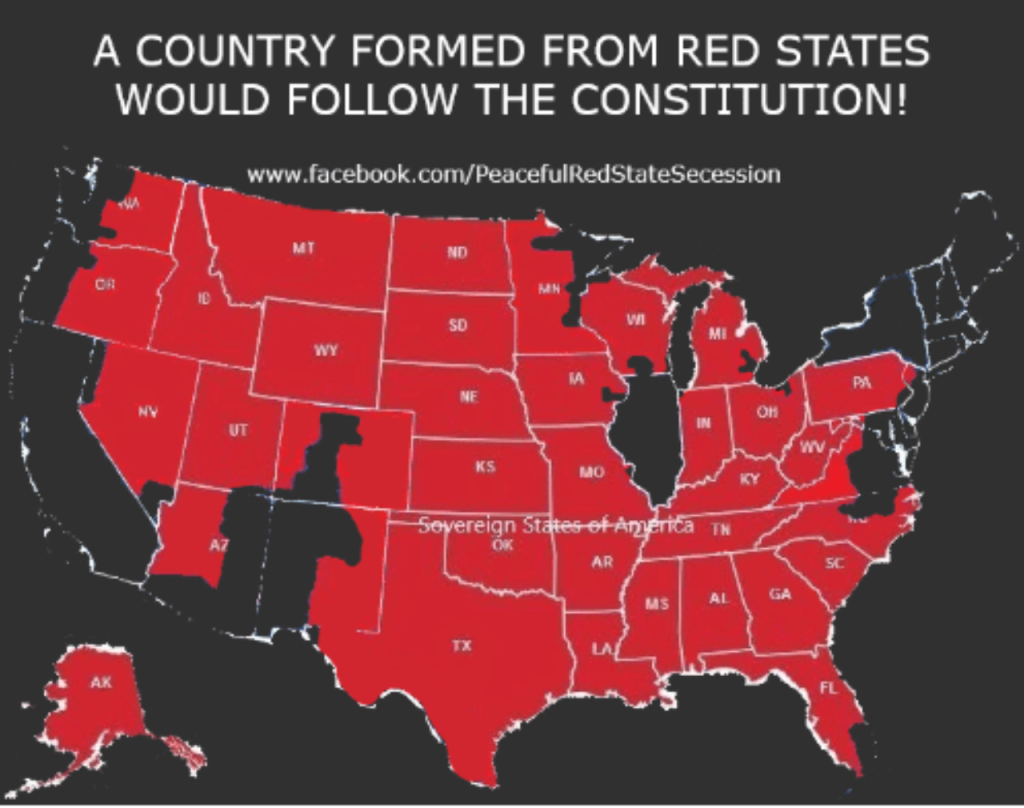

–taken as an icon of American identity. For Trump wanted to cast them, not tacitly but explicitly, as proof of a “great replacement” of whites that that did not need to be located in a state–Springfield might be in Missouri, Florida, Massachusetts, Kentucky, Illinois, or Ohio, where like-named towns existed–but denoted a replacement of American values that American needed to be paid attention to. And given the almost generic image of a Middle American society at risk. To be sure, social media provided a willing megaphone to expand these fears, that the Biden-Harris team ignored. The Haitian refugees were conjured as a danger to the nation, a synecdoche for the figure of the migrant in its most un-American form in the only Presidential Debate between Harris and Trump. A set of talking points that emerged from an interview stating that there was no evidence that Haitians had eaten animals–ducks, geese, or dogs–was shamelessly manipulated in the coming weeks by Charlie Kirk, the head of Turning Point who has never shown much respect for the truth in making vitriolic points, as if it was all the proof he needed to confirm a vicious internet meme.

The Speaker at the Republican National Convention Who Eagerly Spread False Rumors of Dog Eating Haitian Immigrants

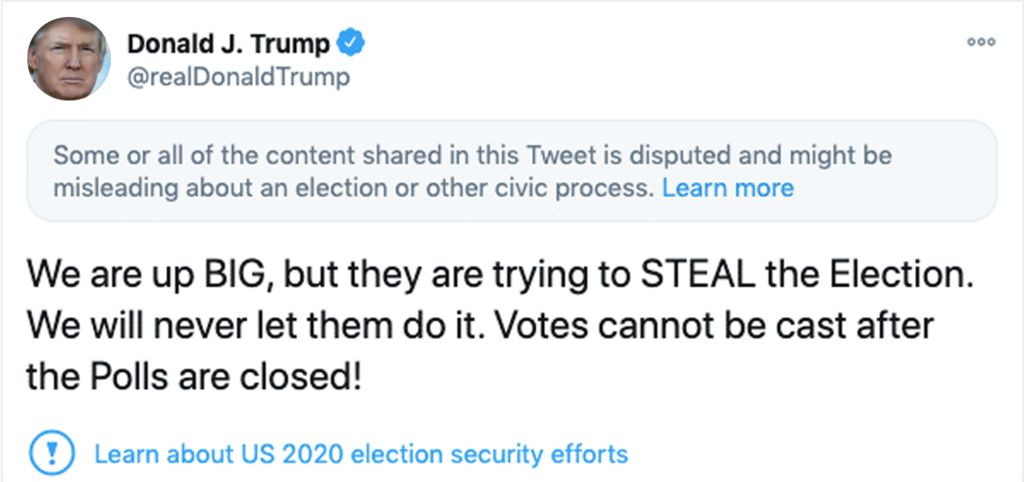

But if the talking points became central to energize audiences at the Presidential Debate, they gained a life of their own on social media that seemed to erase any question of reality, as the image of disappearance of ducks, geese, and dogs had quickly conjured an enemy from within that boosted calls to enforce the investment of public funds to guard the border. The former President showed little sense of responsibility that would make him merit the Presidency, of course, as he mapped migration by local and not global terms in declarative sentences: “In Springfield, they’re eating the dogs. The people that came in. They’re eating the cats. They’re eating — they’re eating the pets of the people that live there. And this is what’s happening in our country. And it’s a shame . . .”

The generic third person plural was left unidentified, but asked one to map one’s relation to the country–as in “they’ve shot the President” or “they’ve killed the Senator!”–to distribute collective guilt across all migrants, in ways that were, to be sure, readily echoed after Charlie Kirk’s shooting with the blurring of the motives of his assassination as the product of “Democratic left” and “Democratic assassination culture” (John Kass), out to kill the real inspiration to America’s young, “the political left” (Governor Spencer Cox), and “an attack on [President Trump’s] political movement” (Lindsay Graham), or Joe Biden’s attempt to “silence people who spoke the utter truth” (J.D. Vance), and even “the damage that the internet and social media are doing to all of us” (Spencer Cox again, this time on Meet the Press and not a news conference). Yet the drumming up of internet rumors, as much as Kirk’s genius in organizing outreach to younger voters, was the basis of the sordid stock racist accusations of immigrants eating dogs. “They” did not need to be identified; “they” were the people we needed to keep out of the country.

The fears of the “open borders” policy that the Biden-Harris team had willfully persisted was cutting short America, as the Republican congressmen on the Judiciary Committee investigating the injust policy hadgenerated on what seemed official masthead, a waste of official papers to distract American voters–

–in a waste of official congressional paper, to make the meme material in the national news media and the consciousness of Americans who worried about those “leaky borders” as being a threat to American society. And now, it had gotten so bad that even the dogs would suffer.

Not only Charlie Kirk ran with this, but the entire right wing media system seems to have kicked in as the story materialized. The insinuation profited from how the “pet dogs”–even if they did not exist, or were not eaten as per rumor–had become red meat as clickbait within the Turning Point media empire and social media of the Alt Right. The alternative reality Trump dignified was imported wholesale from social media. Indeed, when the moderator questioned the basis for the statement in a forum for selecting the future President, Trump offered no actual proof but returned to innuendo: “Well, I’ve seen people on television . . . people on television say their dog was eaten by the people that went there,” revealing the wrong of offering migrants asylum as a threat to domestic pets. “Cats are a delicacy in Haiti,” offered the video that Kirk made to give wider currency to rumors of the abduction of pets–as if it were the 2024 version of the international pedophilia ring Hillary Clinton allegedly “ran” out of a pizza joint–and “ducks are disappearing,” as if to map the Springfield as a “tinderbox” of the crisis of immigration, and the 20,000 Haitian migrants who arrived in Springfield over the last four years who have helped to drive the small city’s economic boom became evidence of illegals taking open advantage of the Immigration Parole Program of Joe Biden to sacrifice American pets as if they were cannibals, eating the dogs that became a synecdoche for all Americans–and the American Dream.

Even as Haitians had themselves insisted on the news that “We’re here to work, not to eat cats,” in response to the outlandish accusation, the footage of their protests offers, however circularly, footage that was consumed as evidence of an admission of their alleged guilt. The protests became evidence for the need for a new Immigration Ban, and stoked fears of the Great Replacement. What was red meat for social media clickbait became passed off as truth, in the false currency occasioned by Presidential elections, that have become sanctioned rumor mills since Whitewater if not Watergate, as charges of incompetency materialize in disproportionate commensurability to the weightiness of the office of U.S. President.

The feast of hate male that the MAGA movement has invited has opened up the sluices on social media innuendo, inviting us into the society of spectacle of online memes to launch a bid to defend the nation. Trump’s brusk adoption of the first-person reminded us that he was in charge, and should be, effectively asking viewers of the debate to join him, watching TV in his home. He seemed to call for a need vigilance to supervising the crisis of migration that Vice President Kamala Harris had permitted to threaten the country, papering over a national emergency that the Democratic Party refused to acknowledge as an invasion as he had called-even at the risk of endangering the safety of Springfield’s domestic pets. He’d be watching . . .

For her part, it was utterly unsurprising Kamala Harris was unable to respond to the outrageous charge with concreteness. Did she fail to connect in any similarly visceral way or was she just unable to reply to the outrageous claim? Trump had outflanked the outrage that his constituency had come to expect. The fictional charge perpetuated myths of aliens endangering Americans’ pets J.D. Vance used to reveal the threat admitting immigrants–even granting asylum–as a threat undermining civil behavior and the American family, but pushed the boundaries of civil norms. There was no sense that the charges aiming to dehumanize the immigrant and to blame her for the endangerment of American pets could be presented on national television as evidence of the danger she would cause the nation: it was all but impossible for her to enter that rabbit hole. Could one even trust Kamala Harris to be a defender of America against these Haitians, her very appearance and hair suggesting that she could not be trusted to protect white Americans from the arrival of migrants who failed to understand American values, and failed to integrate in white America? This proclaimed the reclaiming of tacit racism on steroids by Trump, Kirk, Vance and Stephen Miller.

Presidential Debate in Ohio, September 10, 2024

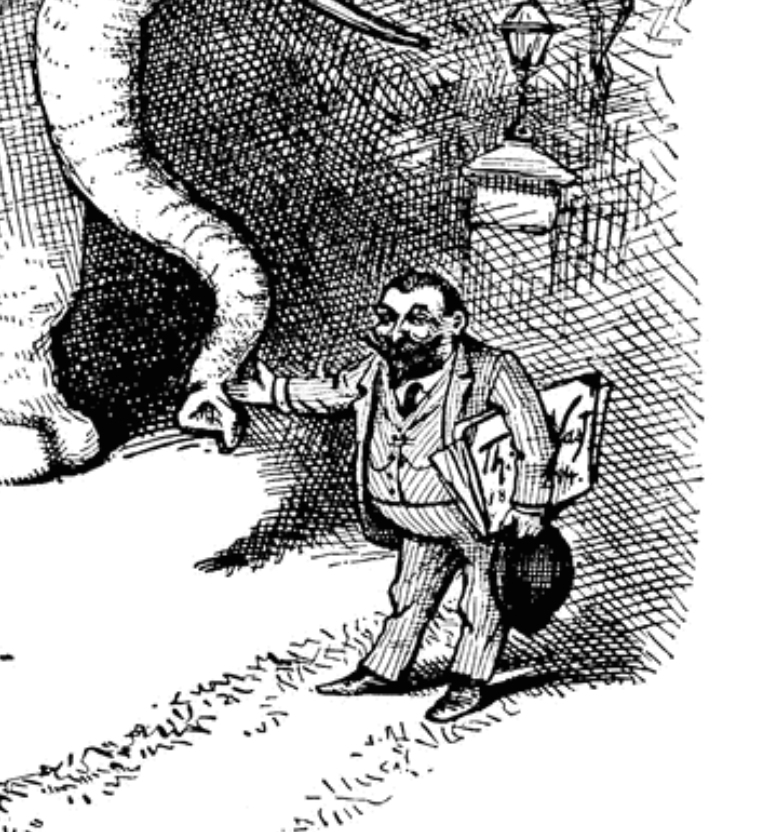

The outrageous and ungrounded accusation against Haitian immigrants of being cannibals recycled old fears of the beast-like nature of an island colonized by Spain and long used for American enterprise at low wages, was rather tired. After all, it was one of the more striking images of the Governor of the colonial administrator who had served as Governor of New York State, the Irish-born Cadwallader Colden’s colorful description of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, based on his early position as the first colonial representative to the Iroquois nation. His familiarity with the Five Nations of the Confederacy had featured the puzzled anthropological observation that “the young men of these nations feast on dog’s flesh,’ although Colden, in 1747, confessed he was unsure “whether this be, because dog’s flesh is most agreeable to Indian palates, or whether it be as an emblem of fidelity, for which the dog is distinguished by all nations.” Whatever the reason, he admired the indigenous “boast of what they intend to do, and incite others to join, from the glory there is to be obtained: and all who eat of the dog’s flesh, thereby enlist themselves” in a gory potlatch of canine flesh to display their martial bravery. The dog-eating indigenous males revealed their militant character that Colden felt worthy of the virtue, discipline, and honor of Romans, if their modern use of muskets, hatchets, and sharply pointed knives, if abandoning bows and arrows, accompanied fierce adornment of themselves with red war-paint, “in frightful manner, as they always are when they go to war,” rivaling the military discipline and honor of Romans.

Not so for the Haitians Trump painted who arrived across our open borders. The accusation Trump leveled suggested a third reason for the eating of dogs: the Haitians’ absolute inhumanity, which needed to be separated by a wall. It clearly bore fingerprints of his speechwriter Stephen Miller, who had just crested 100.000 views on X after questioning allowing “millions of illegal aliens from failed states” in “small towns across the American Heartland.” Donald Trump could not help himself in echoing Miller’s charge, as he held his ground on the debate stage, summoning a sense of grievance by lamenting as if to himself “What they have done to our country by allowing these millions and millions of people to come into our country . . . to the towns all over the United States. And a lot of towns don’t want to talk — . . . a lot of towns don’t want to talk about it because they’re so embarrassed by it.”

September 19, 2024

Was this not itself an open violation of social norms? It mapped Haitian migrants in the United States, if not openly criminal, as endangering the nation that demanded to be fully revealed. The outrageous charge of “eating the dogs” was not only unfounded, but pushed the nightmarish scenarios of migration, a stock trick of the 2016 election, mapping an invasion migrants allowed under the poor vigilance of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris: an outrageous charge fabricated out of whole cloth dominated post-debate discourse, becoming remarkably effective in social media, resurrecting the worst stereotypes of deep prejudice that subverted any debate on immigration policies by purported evidence no one in the White House was willing to acknowledge. The protection of domestic pets started to seem like it was about the enforcement of border policy. Was this pandering not a sort of primal fear of othering, tracking the approach of a race not like us who didn’t share our basic customs or social codes as they crossed the southwestern border?

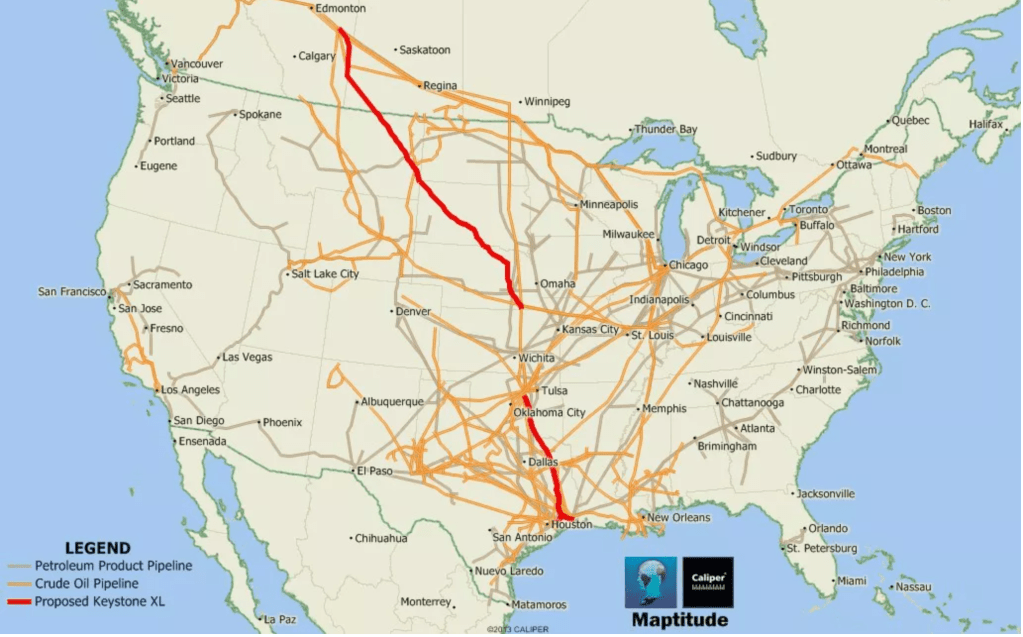

Planting the rhetorically powerful fears of dog-eating immigrants as invasive revealed the Haitian as an attack on values that need not be brooked–an attack on American values passing under the radar of the current administration that failed to screen migrants in promoting a CBP One™ Mobile App as an open portal for undocumented migrants to allow migrants provisional I-94 entry, schedule appointments at points of entry, or gain temporary visas–a program he immediately shuttered after his 2025 inauguration. The mobile app reduced illegal immigration grew popular among Haitians, Cubans, Venezuelans, and Mexicans as it streamlined opaque processed of applying for residence, but Trump reviled it as evidence of a policy of open borders, attracting almost a million users for tens of thousands appointments with migration courts. It would abruptly cease functionality in January 2025, cancelling pending appointments migrants made, leaving many without any basis to pursue the hopes some 280,000 had had hopefully logged into daily, as he pledged to use the army to remove 11 million he claimed in the country illegally by mass deportations, and canceled court appointments of some 30,000 migrants made for coming weeks. The need for an “immediate halt to illegal entry” he asserted, began with a need to to restore human agency to define who gets to become an American citizen and ending refugee resettlement.

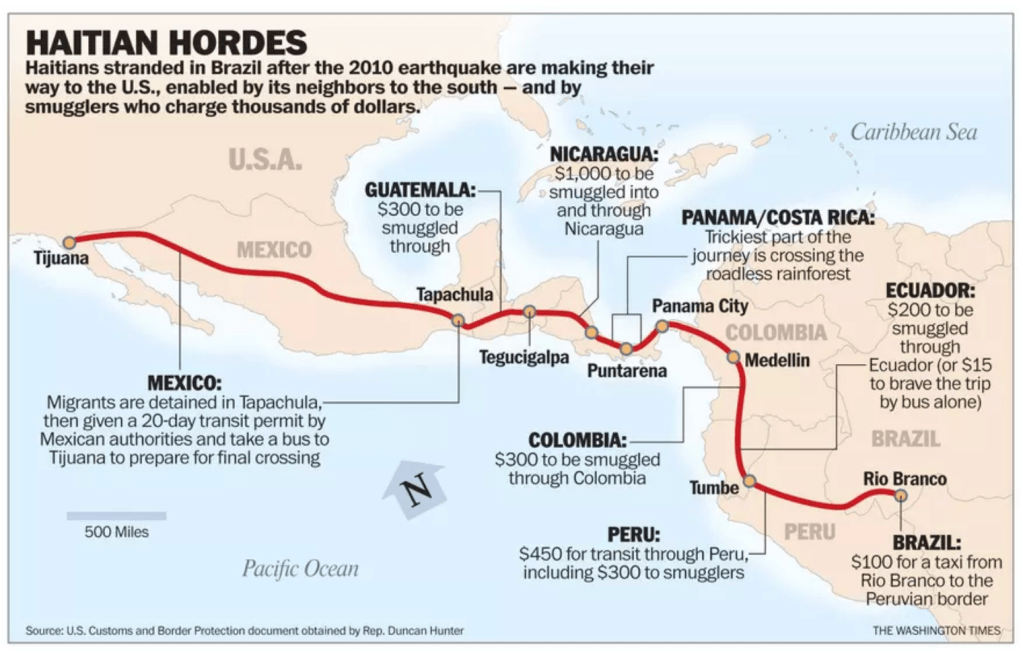

Trump has of course vowed to end illegal and legal entry of migrants, asserting as illegal border crossings had plummeted that the current pathways of migration were not sufficiently controlled. He cast the expedited streamlined avenues of legal migration by Apps as oversteps of Presidential authority, affording provisional entry of undesirables who the Haitians were a recognized token; the MAGA movement outrageously tagged Kamala Harris as having abetted illegal smuggling by an app that allowed nearly a million migrants to enter the United States. The sudden suspension of the app’s functionality be executive order would reduce the reliability, speed, and assistance available to migrants, as if they creating what he called illegal smuggling routes. echoing outdated MAGA maps that accused the Mexican government for enabling the smuggling of “Haitian words” into the United States illegally back in 2016, a map that probably lay at the back of his mind as he cast aspersions on the smuggling of Haitians into America that the CBP One™ mobile app allowed.

“Mexican Officials Quietly Helping Thousands of Haitian Make their Way to the United States Illegally,” Washington Times, October 10, 2016

“Hatian Hordes” did not emerge as a meme in the 2016 election, but it may have lay hidden at the back of Trump’s capacious mind. Did this outdated map of “Haitian Hordes” of the alt right Washington Times not rolled out as fodder in advance of his own earlier campaign for President, eight years ago, underly the logic of his new rather extravagant claim about “eating the dogs,” made without any grounds at all? Candidate Donal d Trump had repeatedly promised audiences of rallies he intended to “end asylum” most Americans did not want or desire, as if the Biden-Harris had enabled an unprecedented national invasion. The figure of the Haitian demanded to be contextualized in the escalating illegal immigration that Biden and Harris had abetted. At his rallies, he had promised the liberation of the nation he would bring about by “return[ing] Kamala’s illegal migrants to their homes,” explaining his intent to replace immigration with “remigration,” or forced rendition, vowing in rallies and social media to “save our cities and towns in [the swing states of] Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and all across America!” Perversely, he would do so by ending an app the app directs each type of user to the appropriate services based on their specific needs. indeed, “the United States lacks the ability to absorb large numbers of migrants, and in particular, refugees, into its communities in a manner that does not compromise the availability of resources for Americans,” read the Executive Order he signed upon inauguration in 2025, cutting off access to jobs in America or migrants fleeing persecution, or even American allies from Afghanistan, as if drawing up a drawbridge that had long existed on the grounds that the nation was “full up.”

August 20, 2024/Trump Rally in Howell, Michigan/Nic Antaya

The charge of dog-eating Haitians elevated the gutter of the internet to Presidential debates, as an exemplification of the false statistics displayed at rallies in order to make his point to the nation. The salacious accusation picked up off of social media was presented as if objectively true, elevated from social media to the forum of a Presidential debate as a basis to chose the next President. Trump recycled a hurtful and demeaning meme as if it were a charge, and evidence of the clear need to restrict and stop migration outright–and discontinue granting asylum to refugees, legal or illegal. The charge elided the right to asylum, or the persecution that immigrants faced–or, indeed, the dependence it would throw migrants into on smugglers. For by revealing the true identity of foreign-born immigrants as dangerous outsiders, ready to consume domestic pets, Trump tagged the Haitians as threats to the nation by mapping their foreign origins, introducing a logic of mapping the threats by their nation of origin as needing to be expelled from the social body to make it healthy again–and in suggesting the need of a strongman able and ready to confront the eaters of dogs to expel the migrants for breaking the deepest social bonds of American society.

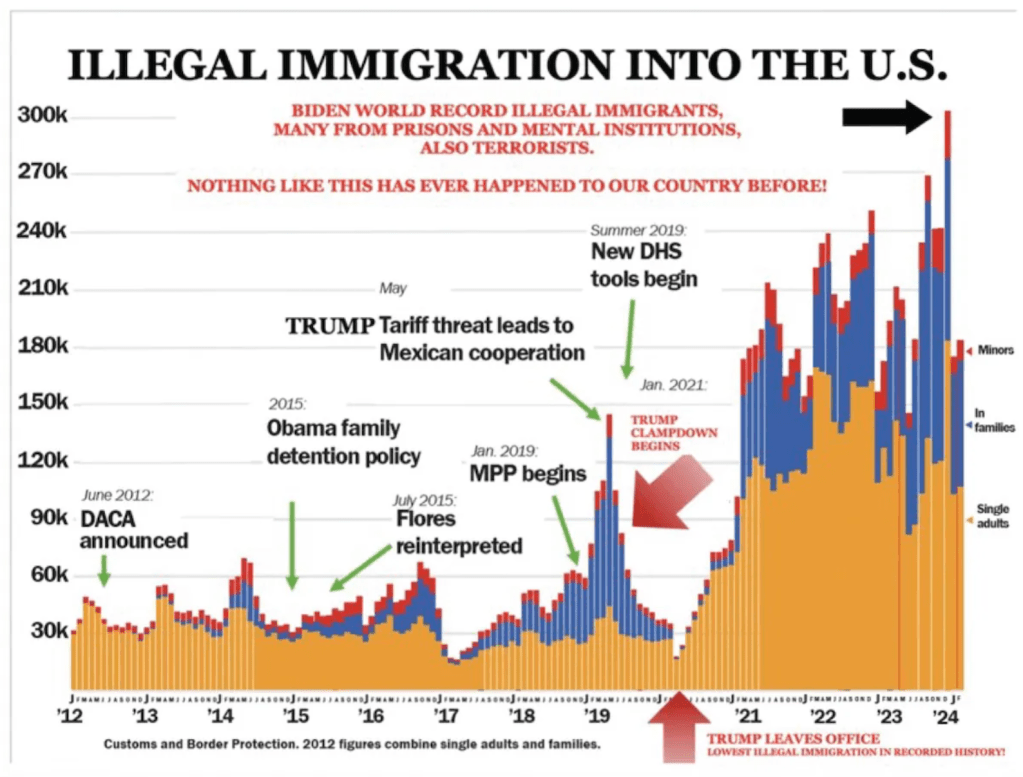

Indeed, the rhetorical image of migrants suggested an image of rounding up stray migrants, posing a danger to naturally born Americans, and the limits to which the Biden-Harris migration policies had pushed the nation to the bursting point–a powerful narrative if one hardly grounded in fact. The charge was but the latest dog whistle designed to stir up anti-immigrant fear resurrected old tropes not only of casting Haiti as the target of fear as a rare outpost of the European colonies where slavery was outlawed, where black majority rule stood to upset racial hierarchies and upset a civilized order. Fears of an imbalance in racial hierarchies fed unwarranted fears of immigrants fleeing repression as a known vector of infectious disease. Trump had long attacked a “Phone App for Smuggling Migrants” as a way to facilitate illegal immigration that Harris and Biden created for the sole purpose of “smuggling” migrants into the United States–an app Trump vowed to terminate, and did as soon as he entered the Oval Office. He blamed Harris for allowing migrants to access App dating from his Presidency, available from Google play stores and Apple since 2020, that he identified with Harris–maliciously vowing to “terminate the Kamala phone app for smuggling illegals (CBP One App), revoke deportation immunity, suspend refugee resettlement, and return Kamala’s illegal migrants to their home countries”–as if the presence of migrants eating pet dogs was due to Harris’ negligence in outsourcing human intelligence, rather than an effort to increase border security. The “big reveal” during the debates revealed the inner nature of the migrant as a threat, undetected by an app, and demanding human intelligence and vigilance he could provide, promising to end the spike of an alleged “Biden world record illegal immigrants, many from prisons and mental institutions, also terrorists”–as undesirable as the dog-eating Haitians seem to be.

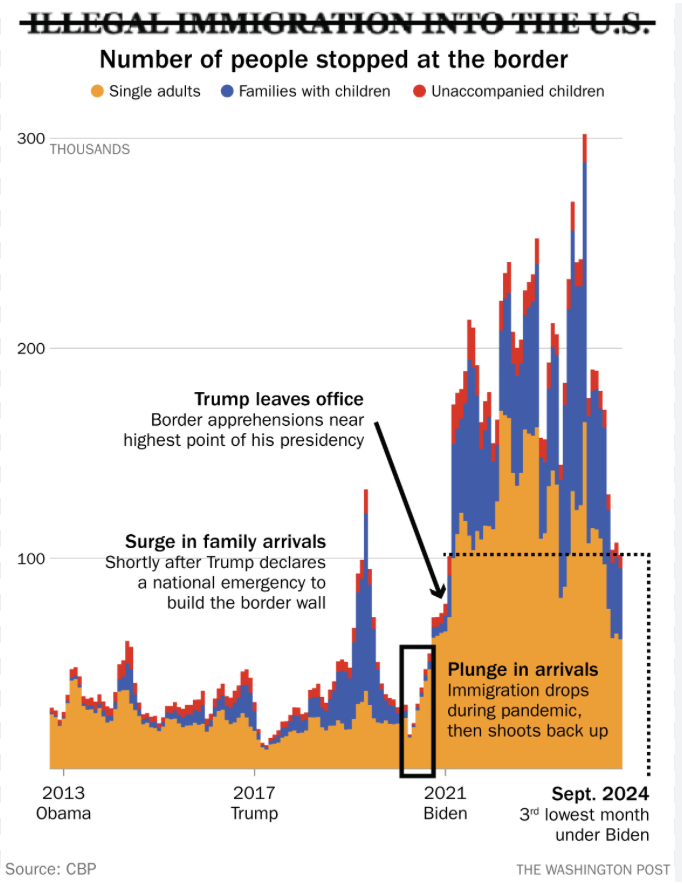

The vignette was a theatrical reminder of the need to “immediately end the migrant invasion of America,” blurring the need to “stop migrant flights, end all illegal entries, [and] terminate the Kamala phone app for smuggling illegals as if they were all contributing to an invasion we allowed–although the misleading chart he was so fond of displaying that suggested an emergency indicated not “illegal immigration” at all, but Border Patrol statistics on those stopped at the border, not admitted, and the drop in immigration arrivals of the pandemic shot up in his Presidency, readers of the Washington Post, before it became an organ of government, were reminded over a month after Trump presented the meme domestic pets had been injured by immigrants who crossed the border.

The misleading charts later touted as the “chart that saved Trump’s life” not because of its inaccuracies, but that had grabbed his attention for a moment as he looked toward it in the rally of July 14, 2024, moving his head to the chart that became the basis to boost his political fortunes, he dodged an assassin’s bullet. But for all its abundance of stubby red arrows and acronyms, was a story that he was massaging all along:

Washington Post/October 24, 2024

The statistics he presented of the escalation of illegal migration into the county. The insinuation animal-like people had attacked the pets of American families appeared grounds to impose discriminatory immigration policies that would abandon longstanding principles of granting asylum.

The baseless charge pushed us back in time, stoking fears of globalization opened the nations to attacks on white American families that dated from the first age of globalization. While presented as the latest evidence of the wiles of these immigrants Biden and Harris allowed to enter our borders by their Border App, it seemed evidence of their readiness to sacrifice the safety of the nation to a dog-eat-dog world that existed outside the safety of American borders, rather than expedite the complicated process of cross-border migration. If the partnership of man and dog has been long a sturdy basis for cooperation, and indeed a paradigm for human companionship, if not of parallel evolution, the immigrants were upsetting of categorical distinctions fundamental to the nation by treating pets as meat. This was not only evidence of their alleged desperate hunger, but an insidious attack on the stability of the social order–upsetting of naturalized hierarchies of man and animal feared since first contact with the New World and the naming of Hispaniola in 1492.

What was presented as the big “reveal” at the debates of the failure of the Harris-Biden team to look at the evidence before his own eyes was grounded in stereotype, it recycled fears dog-headed men inhabited New World islands on the edges of the inhabited world–among other monstrous races–in the first printed book to recycle attention-grabbing images in the encyclopedic images used in 1493 Liber chronicarum known as the “Nuremberg Chronicle”–a historic achievement of the early press–their wagging tongues colored red in deluxe editions to suggest their inarticulacy–

–where the corrupted tongues of the inhabitants of New World islands were imagined as a focus of concern, lacking rational speech.

Dog-Headed Man, or Cynocephali, from Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

There was almost the sense in Trump’s odd declaration in response to question about immigration to the United States that he expected us to believe at least some of those twenty-thousand might actually have, even if legal immigrants, crossed a threshold of civil behavior and violated one of the greatest taboos in the lands the AI image in the header to this post tries to conjure. “They’re eating the dogs” launched the most recent addition to the laundry list of the hidden cost Americans pay for a poorly policed border–but it raised the bar beyond criminality; dealing drugs; belonging to gangs; taking jobs; and taking housing. When I canvassed for Kamala Harris in Nevada, it was memorable that a friendly man on whose door I knocked in Carson City smiled as he lifted his cute kitty before me, assuring me at once that he would soon be voting Democratic and loved his pet– “[’cause] I don’t eat dogs; I don’t eat cats.”

In the month and a half since Trump delivered the unfounded accusation on national television it had percolated within the political discourse, taking shape as a hateful accusation and a venting of anti-immigrant sentiment. The confession was a joke, more than a confession, but an admission of the power of the Trump-Vance trope that extended to a theatrical appropriation of citizenship by a prospective voter, jokingly confessing to me the absurdity of the situation where migrants were so thoroughly demonized in ways that even if I weren’t the son of a psychoanalyst would make me think of Sigmund Freud’s reminder that jokes are deeply related to the unconscious–and even the collective unconscious that Trump had so successfully tapped–that reservoir of rhetorical figures of “women, fire, and dangerous beasts” that led Freud to ponder in 19054 how “only a small number of thinkers can be named [in western philosophy] who have entered at all deeply into the problems of jokes,” plumbed the relations of the comic to caricature, rooted in the comic nature of the verbal contrast between apparently arbitrary connections or links seem to discover a sense of truth in its verbal economy–a compression of meaning that creates a new statement, where the allusion to the monstrous may be a stimulus to revealing the nonsensical nature of the statement, as if it imagined the half-human people on the worlds’ edges imagined in 1493, as the first news of the New World filtered back to Germany, by the printing house in Nuremberg, blurring fact and fancy be medalling visually inventive if vertiginous half-truths.

The widely performed song adopted as a call and response by touring bands in clubs, audiences recite a chorus of dog sounds and cat purrs to personify the purported victims of Haitian migrants. If Freud reminded us that jokes rely on operations of condensation and displacement to subvert judgements by releasing what we might repress, Trump seemed to tap a long repressed collective unconscious of New World cannibals that cast migrants as non-humans, as much as not living legally in the land, drawing lines of exclusion to affirm the rights of nativism long repressed to assert them on the debate stage about the carnage faced by domestic pets–as it became a central point on which to determine who would occupy the White House.

This is not only interrupting consensus on immigration statistics, but elevating internet rumors to the stage of political debate of a Presidential election that is comic enough as displacement of speech acts. Eating pets powerfully indexed otherness and terrifyingly tagged a threat to domestic tranquility; in a nation where pets are in fact among perhaps the best-fed and most-protected of its inhabitants, the threat to domesticated animals violating a salient border of civil behavior, marking a moment of catharsis for its patent absurdity but evoking a long repressed image of the other. Harris had to laugh when Trump stressed “they’re eating the PETS of the people who live there” as if a refrain of moral outrage: the White House had just taken their eyes, the hidden message ran, at what is happening in small towns “across America”–and the state of affairs confronted by the people of Springfield or Aurora: “they don’t even want to talk about it,” because “it is so bad.”

The debate, widely promote4d as determining the next executive to lead the nation, may have allowed him to ask viewers who voters in America wanted to put into the White House, and who would have their best interests in mind–not only global warming, revealing a hidden “real threat” that immigrants posed in ways that Biden and Harris blithely overlooked from Washington, DC.

This wasn’t “news,” but demanded to be included among the issues confronted on the debate stage. For Trump specializes in escalating his oratory to stentorian tones, in explaining political elites had neglected that “they’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the pets, of the people that live there,” weighting each syllable as Harris reflexively laughed, and tried to preserve composure while wondering what she might say to reassure Americans as he uncorked a disclosure of the violence on unleashed on American soil. “This is what is happening in our country, . . . and it’s a shame,” Trump gravely intoned, masking his reach into the dark gutters of the internet with gravitas. Harris barely processed the outrageous claim clothed in faux seriousness as a peril. Harris clearly never expected to hear a displacement so extreme on the debate stage before a national audience, or an issue that the nation was taking seriously in a debate on their visions for the nation’s future. The red flag that was raised alleging that immigrants with government “protection” were engaged in eating pets gained national attention, as it coursed through the internet in ways that amplified a rumor to a story, gaining a faux credibility among anxious Americans, so that Springfield was forced to close its public schools and offices during the presidential campaign, after attracting numerous bomb threats from vigilantes interested in protecting American values that were allegedly under attack.

U.S. Presidential Debate, September 10, 2024

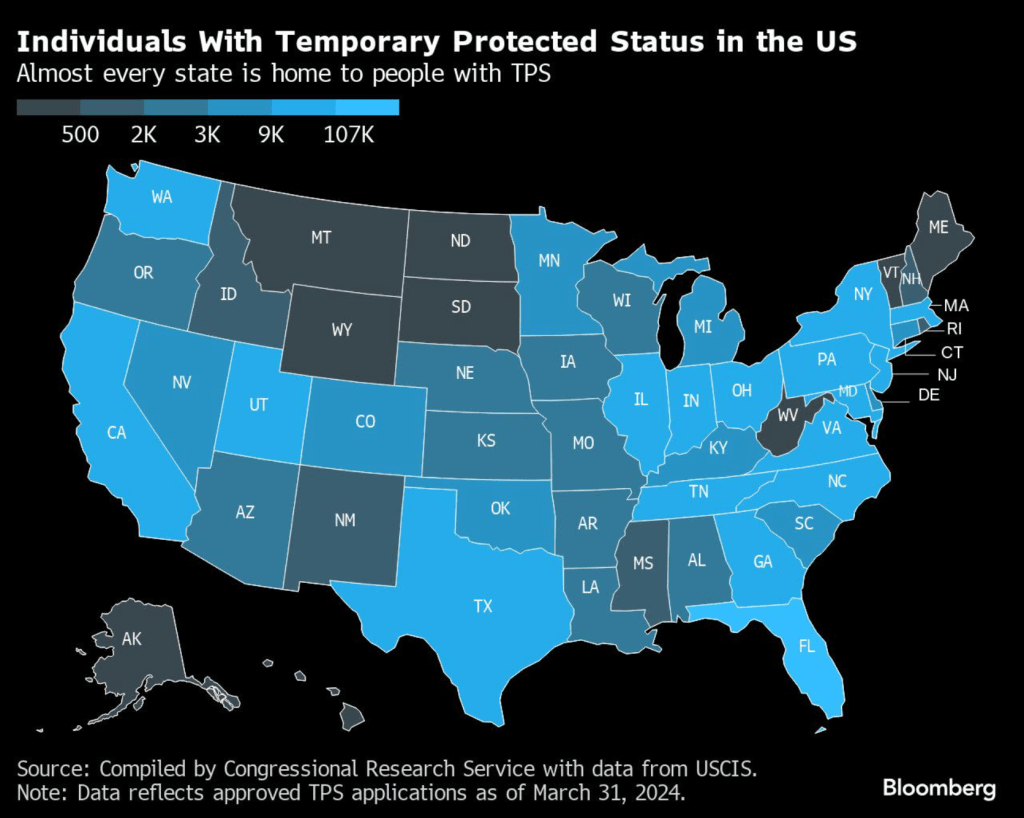

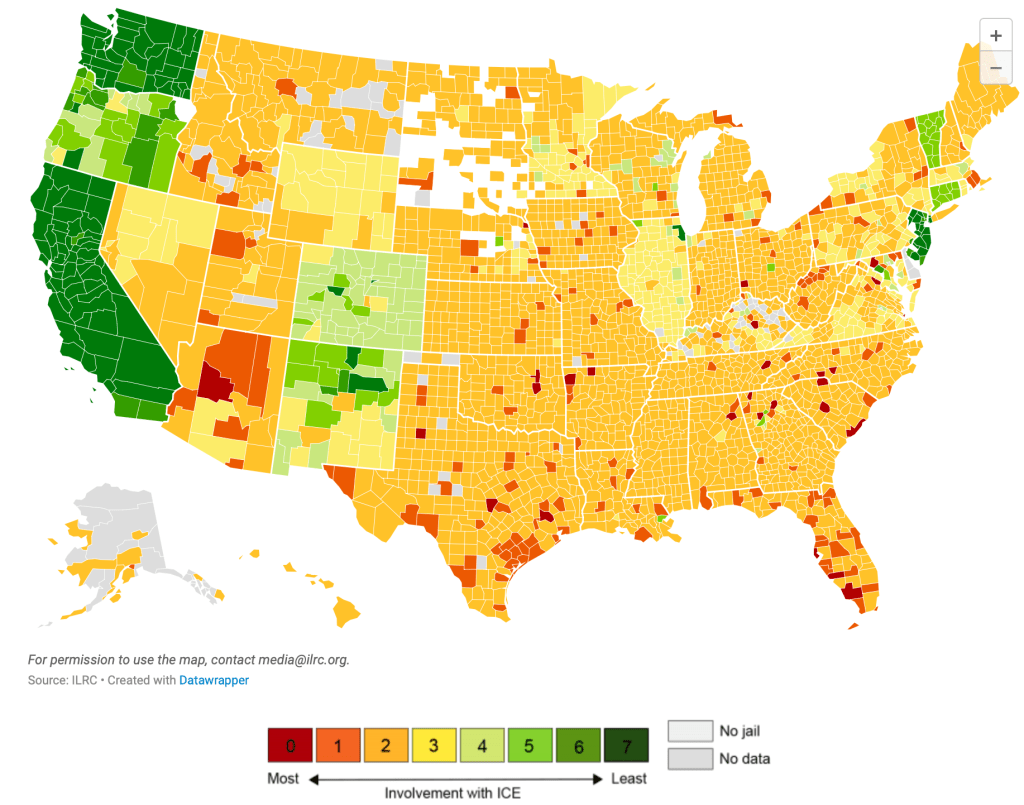

The question was rooted in anxieties that were not rooted in Springfield, or limited to Haitians, but the demographic proved a particularly scary straw man: the charge that an influx of below 135,000 Haitian immigrants Social services and the local health care system in a county of about 15,000 people was magnified in ways that reached the nation. Springfield’s public health officials have struggled to cope with the influx of an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Haitian migrants during the past three years, but the rage was directed to the fact that the US government was offering “Temporary Protected Status” to those fleeing violence and widespread poverty, a humanitarian action that Trump wanted to demonize, long before shuttering USAID: the idea that Americans might help others flee tough circumstances they didn’t deserve was identified as an example of international largesse that the United States couldn’t, in a global economy, afford to continue, as it had encouraged the destabilization of local communities and redirected assistance not to Americans, but to foreigners. And the Temporary Protected Status program had been filling many jobs across the country, but was a subject that was able to come in for a lot of wrath, as s displacement of the focus of government from Americans–even if maintaining a good relation to local states and populations was definitely in national interests. The presence of persons benefitting from Temporary Protected Status whose protections Trump had boasted he would immediately revoke were distributed across much of America, in fact–

–and the notion that these protections were granted seemed a great way for Trump to bring back the sort of cooperations of local law enforcement with federal immigration authorities that were a priority of his first presidency, and which, while Biden had attempted to roll them back, had split the country by 2019, when Biden was elected, as many counties had begun the very sort of close involvement with ICE that Trump was about to promise to restore.

The huge incommensurability between the safety of pets and migrants fleeing persecution was so great it was truly comic in its slippage, as Trump seemed to be spinning facts in ways that seemed to be about borders, but was doing so by peddling utterly unsubstantiated fears. If Harris was trying to process how seriously this fabricated claim might be taken by the viewing audience, amazed that there would be many ready to fall for the bait, and ignore the debate, the direction of which seemed like it might be in danger of suddenly slipping away, as easily as Trump had seemed to recover from the questions she raised about the size of his rallies by attacking her for fabricating the rallies she had held for the previous days. But the issue of a debate about elections seemed less important than the identitarian fears of endangered pets that Trump seemed to be saying had been neglected by the Biden administration.

Fears of dog-eating immigrants were outlandish. They echoed the fearsome nature of the unknown featured prominently in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle as an image of otherness outside the inhabited world–the dog-headed people who gestured, lacking recognizable human speech, were placed at the edges of the known world, talismans of the fake news about “barbarous” peoples and “marvelous races” that early modern readers might expect to define a threshold of the known.

Cynocephalus in Nuremberg Chronicle (Buch Der Chroniken und Geschichten,Blat XII), 1493

The woodcut of dog-headed exotics placed prominently on the edges of the known world circa 1493 in Buch Der Croniken und Geschichten to grab readers attention in the compendium of texts purporting to synthesize all known history, by situating many woodcuts to encourage reading its derivative text. While this motif can be seen as a classic–if not primal–dehumanizing of foreign peoples–the implicit question it raised in the early modern era was whether these dog-headed men possess souls. At a time when Europe was understood to lie on the boundary of an expansive ocean and bounded more clearly, revealed in the edges of early global map featured in the popular book–

Nuremberg Chronicle, detail of world map at Blatt XIIv-XIII Munich State Library, Staatsbliliothek

–the dog-headed men that lay among the fantastic races that ring the global planisphere of Ptolemaic derivation were inhabitants of the edges of the known world described not by Ptolemy, but Pliny Augustine, and Isidore of Seville, and Pliny, authorities one was loath to contradict, whose assertions demanded to be reconciled with the new maps that increasingly included New Worlds. The men who seemed to gesticulate with animation spoke no recognizable tongue, and may have been of some sort of diabolical creation, even if they seem to us early modern cartoons.

Nuremberg Chronicle, Blatt XII, Munich State Library/Staatsbliothek

Are not the dog-eating immigrants not their most recent iteration, people who don’t have respect for pets, fail the affection and citizenship test in one go,–and maybe even lack souls? They surely were imputed to lack patriotism and be un-American, putting aside for now the question of souls– even though the legal migrants in Springfield do not eat dogs. They were terrified at the charge that they did, as the Haitians of Springfield must have wondered what a weird, tortured, social media world they had moved to, where they might be accused of stealing their neighbor’s pets.

Yet these hoary old recycled images of dog-headed men, whose long, loose tongues seemed to compensate, if one notices their animated gestures, for their inarticulateness, emblematized babble in an early book of global history cobbled together from sources of dubious authority and biblical paraphrases. The synthesis of world history was in fact akin to a sort of early modern internet, recycling images and legends circulating in flysheets and leaflets in visually entertaining ways helped readers navigate derivative text that purported to summarize global history. At the same time the edges of Europe were defined, dog-headed Cynocephali were located at the edges of the known world as it was being remapped in real time, situating an upsetting of the divine order of creation that were echoed in fears of dog-eating immigrants who had the edges of the nation.

The eating of dogs has, incidentally, only been legally forbidden in the United States, with the exception of Native American religious ceremonies, and in New York specifically illegal to “slaughter or butcher domesticated dog” for human or animal consumption, suggesting how our legislators take the matter quite seriously–and even if the majority of dogs globally are free-roaming or stray (70% per one estimate at PetPedia, the existence of “dog meat markets” in Viet Nam, the Philippines, China, Indonesia, and Cambodia suggests a blindspot for animal suffering–South Korea will ban meat markets from 2027. The consumption and slaughter of dogs and cats for human consumption was part of the reconciled version of the Farm Bill the Trump White House helped pass in 2018, featuring the “Dog and Cat Meat Prohibition Act,” signed into law by President Trump. The ban on eating dogs was an achievement of the Trump Era, holding there was no place in America for the eating of dogs or cats–both animals “meant for companionship and recreation” and imposed penalties for “slaughtering these beloved animals for food” of up to $5,000. (While China tolerated such meat markets, its sponsor held, “should be outlawed completely, given how beloved these animals are for most Americans” on American territory.)

A part of Making American Great Again was criminalizing killing of dogs and cats, save for religious practices of indigenous,, by imposing federal penalties for slaughtering cat or dog meat for consumption, not protecting animal welfare. While there is no clear coherence for the alliance of the Animal Hope and Wellness Foundation, the nonprofit that promoted the bill’s passage in Congress, dedicated to protecting dogs and cats from being butchered abroad for customer markets in China and Viet Nam, as a step in “making America a leader in putting an end to this brutal practice worldwide,” seeking “to move towards bringing an end to the suffering of these animals who are like our children, our family,” identified two species sought to be banned from foreign meat markets was always a local exercise in response to global problems. The refugees escaping a human rights crisis in the hemisphere would perhaps be both a proxy and symbolic surrogate to the crisis of “illegal” migrants moving across the southwestern border.

The number of Haitian immigrants to the United States had for some precipitously risen–doubling since 2000–as immigration became a hot-button issue, and seems on track to grow tenfold since 1980, creating an irregular influx in response to economic crises, natural disasters as the 2010 earthquake, rising gang violence following the assassination of the Haitian President Jovenal Moïse in 2021, that make Haitians an ever larger immigrant community–and given the threefold increase in immigration since 1990, the community is easily othered, perhaps explaining their targeting by outrageous conspiracy theories about eating pets.

Continue reading