3. Fostering of a changed relation to urban habitat has left the Bay Area and city far less insularly defined in relation to nature than most other places in the United States: Rebecca Solnit rightly observed the old geographers were wrong only in one–if one significant–way in describing California as an island, which extends to San Francisco. In California, one finds, still, significant surviving greenspace, cultivable land, and open space, that while under threat, in proportion to much of the eastern seaboard extends to San Francisco and much of northern California, and significant parts of the southern coast. If the state is known for giant redwood forests and sequoia groves, strikingly significant habitats enter San Francisco’s own natural ecology in its urbanized space.

The recalibration of the place of nature to which San Francisco has been long open has long been measured as something that is threatened and endangered in its scarcity, as paving of asphalt and concrete have dramatically changed its landcover, toward a shift to appreciate and embrace its nature, and indeed embrace the benefits of cultivating not only plants, but rather ecophilia. The celebration of an urban environment far often reduced to being mapped for seismic peril and proximity to fault-lines offers a deep picture of the specific formation and sustainment of a rather unique coastal habitat, both based on accurate data and pushing the boundaries of data visualization to excavate a rich record of–and promote a wonderfully tactile relationship to–broad concerns of ecology and environmental history.

The engaging design of the 2018 map commissioned by Nature in the City begins from a datapoint of each and every tree and green space the city offers, but fosters a productive way of looking at the urban environment, different in that it focusses far less on the pests we often seek to eliminate from our homes with urban fastidiousness, than to appreciate the range of species beside which city dwellers live, despite their frequent focus on roads of paved concrete: in a map that embraces the city at the end of the peninsula from bay to sea, the living cornucopia of habitat that spans the urban environment offers a new way to understand this urban space.

Although ecosystems are the most living areas of cities, they remain hidden from view on city maps of the built landscape or paved roads that define the mobility of “urban” life.

But we often fail to orient ourselves to the extent of urban environments in most maps–especially as we privilege the images of the city seen from the air, as if on landing and take-off, rather than on the ground. The changing vulnerability of cites to climate change and extreme weather has directed increased attention to the vulnerability and instability of urban space, in ways we are still taking stock through maps, the question of what maps best orient us to the future of the city have provoked increased attention from maps of sea-level change, to maps of vulnerability to earthquakes and seismic risks. No city has been more subject to such demands for recalibrating its lived space, perhaps, than San Francisco, the city that is most conspicuously built on several fault lines–so much that the expansive recent downtown rebuilding is cast as a “seismic trap” or a disasters waiting to happen–showing the spate of high-rise construction–

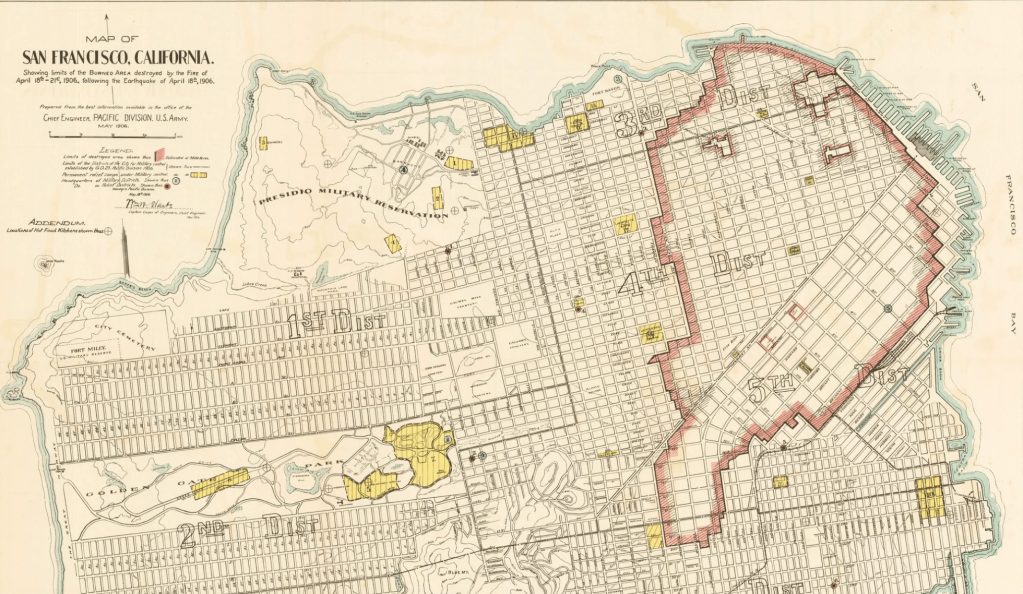

–against the backdrop of the widespread urban devastation of the 1906 earthquake on its hundred and twelfth anniversary, as if to suggest that the memory of that devastating event has receded into the past of public memory.

And if San Francisco was long haunted by the devastating downtown fire that spread through the city with the earthquake of 190 destroyed a good section of the inhabited city, as if it is burned into public memory. The recent shift in rebuilding of elevated buildings allowed to be constructed in the downtown region half almost reflexively prompted the worries or concern of a “seismic trap” in which recurrent seismic tremors threaten the city, and an incursion of nature of underground plate tectonics might even more consequentially disrupt the urban plant of the city once again.

Extent of Burned Area April 16, 1906, US Army Engineers (1906)

Are the danger of such seismic shocks a different image of the sudden entrance of nature into the city?

“Map of San Francisco, California, Showing Bounds of the Burned Area Destroyed by the Fire of April 16, 1906,”

US Army Corps of Engineers, May 1906

–and an even more expansive, and more problematic, expanse of widespread damage due to subsidence, ground failure, landslides, and mapped by 1907, extending form the marshes south of Market Street to the Van Ness and Seventh and Mission, as surface ruptures, slips, and broken water mains left much of the downtown area difficult to build, across a much larger area, all the way up to Golden Gate Park.

Pingback: The Built World | Musings on Maps