What relevance do maps have in a world often organized by database systems that are in themselves often impossible to visualize? One answer is that the map is not only a visual register of data, but prepares an active correlation of information patterns and raises questions about human relations. Rather than arranging data, maps show or highlight selective relations between data in graphic form. Maps do so in ways that generate questions about our relations to space, if not the variety of relations each of us occupy to an otherwise uniform expanse, in order to make space our own; they are as a result particularly useful tools to ask us to consider our sense of place in ways that we might not otherwise find a way to puzzle over and consider, or find a way to concretize. Although the size of massive database systems escape the kind of an individual, the maps that guerilla cartographer Darin Jensen has solicited and assembled in FOOD: An Atlas raise chart the spaces we organize around through food, and understand place through the intersection of place with how food is produced, exchanged and consumed.

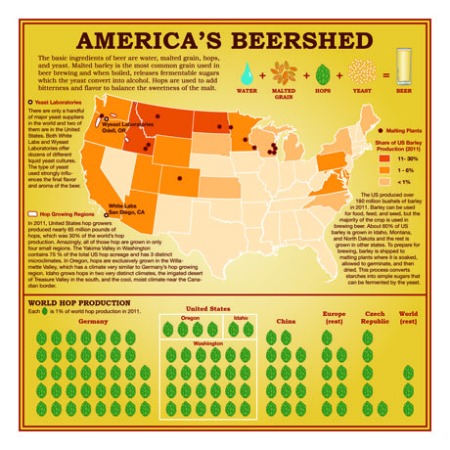

In an age of the unwarranted expansion globalization of food consumption patterns and trade, where the importation and circulation of foods to their consumers often seem shaped by processes irrational in nature, the rationality of the map provides a way to raise questions about how to understand the ways that food sources and substances travel across space both in commercial ways and in raising questions about the efficiency of these systems. In identifying and rendering a joint database of food production and consumption, we can grasp in an entertaining visual form multiple questions about how we value the place of our food and how food is now valued and exchanged over spaces far beyond the places where it is grown. We may not know what bacillus of yeast helped the fermentation of the glass of beer we are drinking, even if we prize the origin of our coffee; we can’t visualize or often even know what field of tomatoes provided the basis for our pasta sauce, or the huge range of regions united in the foodstuffs in a plate of school lunch, or where the almonds of northern and central California travel in order to reach consumers from the Central Valley. The maps in FOOD: An Atlas provides a range of provocative maps of how food interacts with space that provide a compelling set of questions about our relation to place, and indeed the relation of food to space. Maps of the global distribution of grains, or of the costs of the same foodstuffs, remind us of how food exists in relation to place, even if food travels globally—as well as the places where food grows.

The compilation is a true atlas of modern life—or of modern tastes for foodstuffs. The Dutch engraver and cartogapher Abraham Ortelius compiled the first global atlas by sourcing maps from different areas in Europe from his multiple correspondents in the 1560s, obtaining a range of extant cartographical forms of nautical and terrestrial form that he collated in a synthesis of terrestrial coverage that canonically redefined the image of the inhabited world. Refined and expanded in his own lifetime and after his death, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum bound these multiple maps obtained from different parts of Europe and vetted in Amsterdam in a single commodity that was immensely popular and, though dedicated to Philip II of Spain, was disseminated over a huge geographic expanse.

The crowd-sourced maps collected in FOOD were sourced in a considerably shorter period of time over the global internet, solicited from cartography listserves and Berkeley classrooms alike, starting from the North American Cartographic Information Society (NACIS) and coordinated through a GIS lab where proposals for mapping were often linked to potential owners of databases, and submitted maps refined for their persuasive visual organization, the transparency of their cartographical iconography and the appeal of their format. The variety of graphic skills that are applied to map food and food’s distribution are themselves inventive exercises, and suggest the degree of invention that

The crowd-sourcing of the atlas is not only a question of pragmatics, but itself an instance of informational exchange. On the one hand, Jensen describes how he arrived at “a project of guerrilla cartography and publishing” as the result of a natural desire to make the sort of compilation of maps that “take too long to make,” which led him to “an experiment in doing it faster,” both by relying on crowd-sourcing and local publishing. “It doesn’t have to take two or three years to put out a book or an atlas.” The anonymity of the crowd sourcing generated a far more imaginatively diverse use of mapping conventions—unlike Ortelius’ interest in universalized norms, they celebrate local diversity of mapping abilities in keeping with the polycentrism of a post-modern age. Rather than conforming to a single style or aesthetic, each crystallizes specific issues in an individual fashion. The maps provoke us to consider the relations of place and food, and alter or tweak our relations to the world in mapping the circulation of food wastes, the sites for importing tomatoes for that pasta sauce, or the “food swamps” where junk food constitutes a dominant share of the foods for sale. Each is brilliant in its own way. Whereas we know the many authors of the maps that Ortelius collected primarily from his extensive correspondence, as well as the “elencum auctorum” that provided a comprehensive list of the different authors of maps in his atlas and sources that were consulted in its creation, Jensen lists the individual or joint authors of each map–and even invites us to construct our own!

Why create a set of maps of the relations between food and space? This volume is a way to rehabilitate the use of the map as a way to consider and contemplate relations we construct between place, as well as the product of a local culture of food. All food is local, even if the world we live in has globalized food as a resource. The open arguments of maps Darin Jensen and his team assembled in FOOD: An Atlas provide a collective tool to understand what might be called the irrationality of the globalization of food sources in the transparent and supremely rational language of cartographical forms. Much as the previous MISSION: POSSIBLE led us to view one neighborhood in San Francisco in new terms of the distribution of coffee-shops, trees, ethnicities, restaurants, underground gas reserves, parking spaces or sounds, each map in FOOD: An Atlas provides a distinct corner of the exchange of food as commodities and elegant goods we value for their local origins, as well as celebrating the recent growth in the valuation of the locally produced good. As Jensen’s map of the Mission noted the rise of artisans in the neighborhood, the mapping of Farmers’ Markets—both in Berkeley and in the United States—offers a view of the rising value of the locally farmed (and even the changing definition of what local farming means) as well as the access and audiences of these markets. As MISSION: POSSIBLE provides both a map of a region of San Francisco and a sort of surrogate for orienting oneself in any modern city, FOOD: An Atlas provides a tool to orient oneself within the global exchange and local production of foods. The map of areas of urban agriculture in San Francisco that is included in FOOD is a great model of a collective interest in the local production of food in that city, and a sort of template for resisting a growing divorce of food and a local landscape.

To order a copy, visit http://www.guerillacartography.net/home.html

How better to understand the pathways by which select regions of almond-growing enter the chocolate bars sold across our nation, or consider the inequalities of food that dominate the urban and rural landscapes in an era that celebrates famers’ markets?