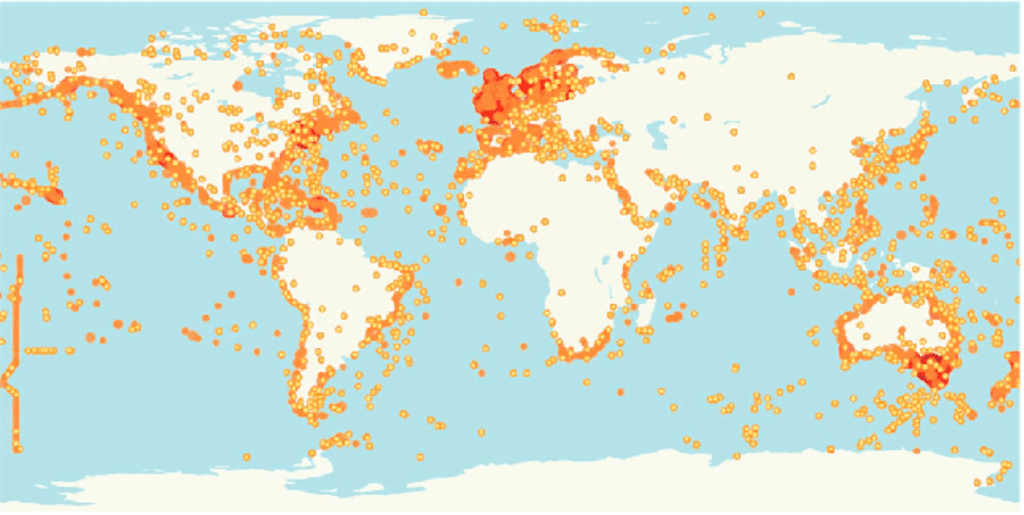

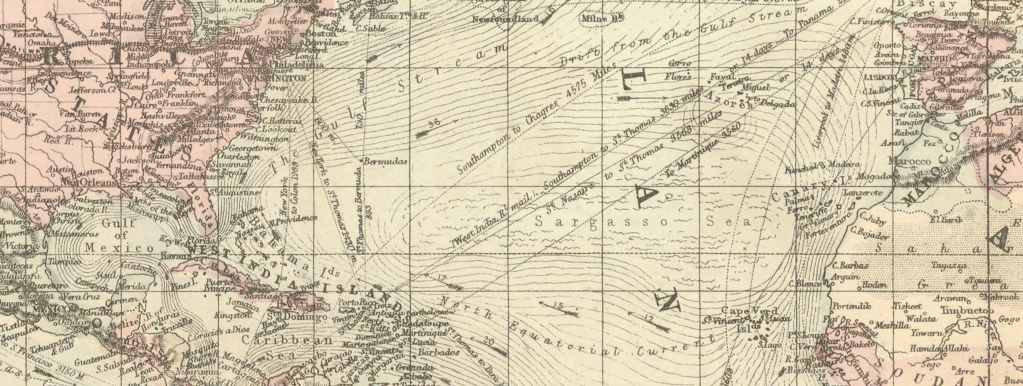

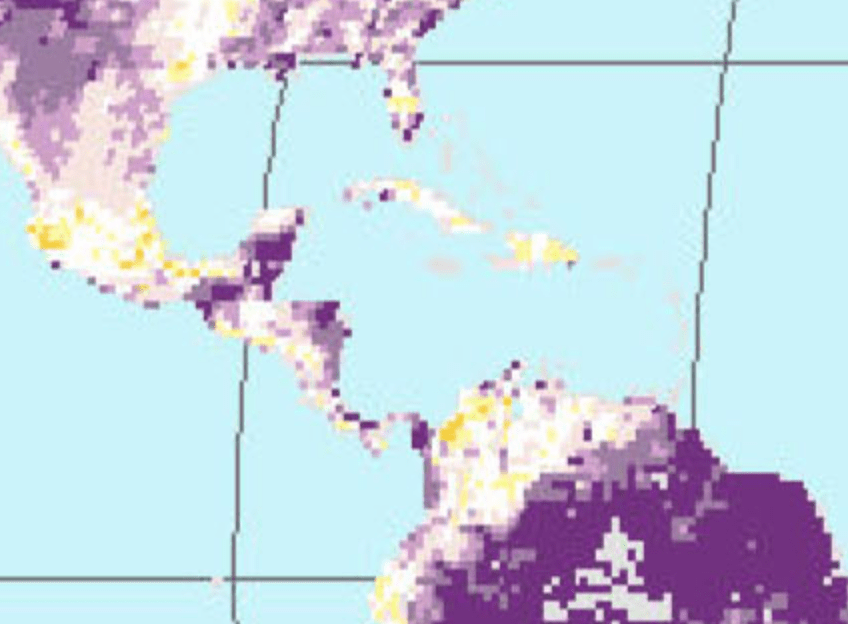

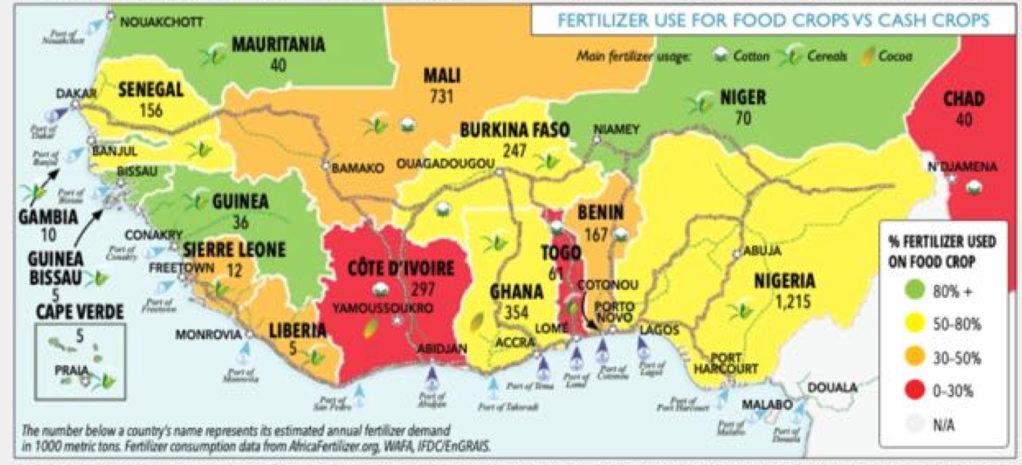

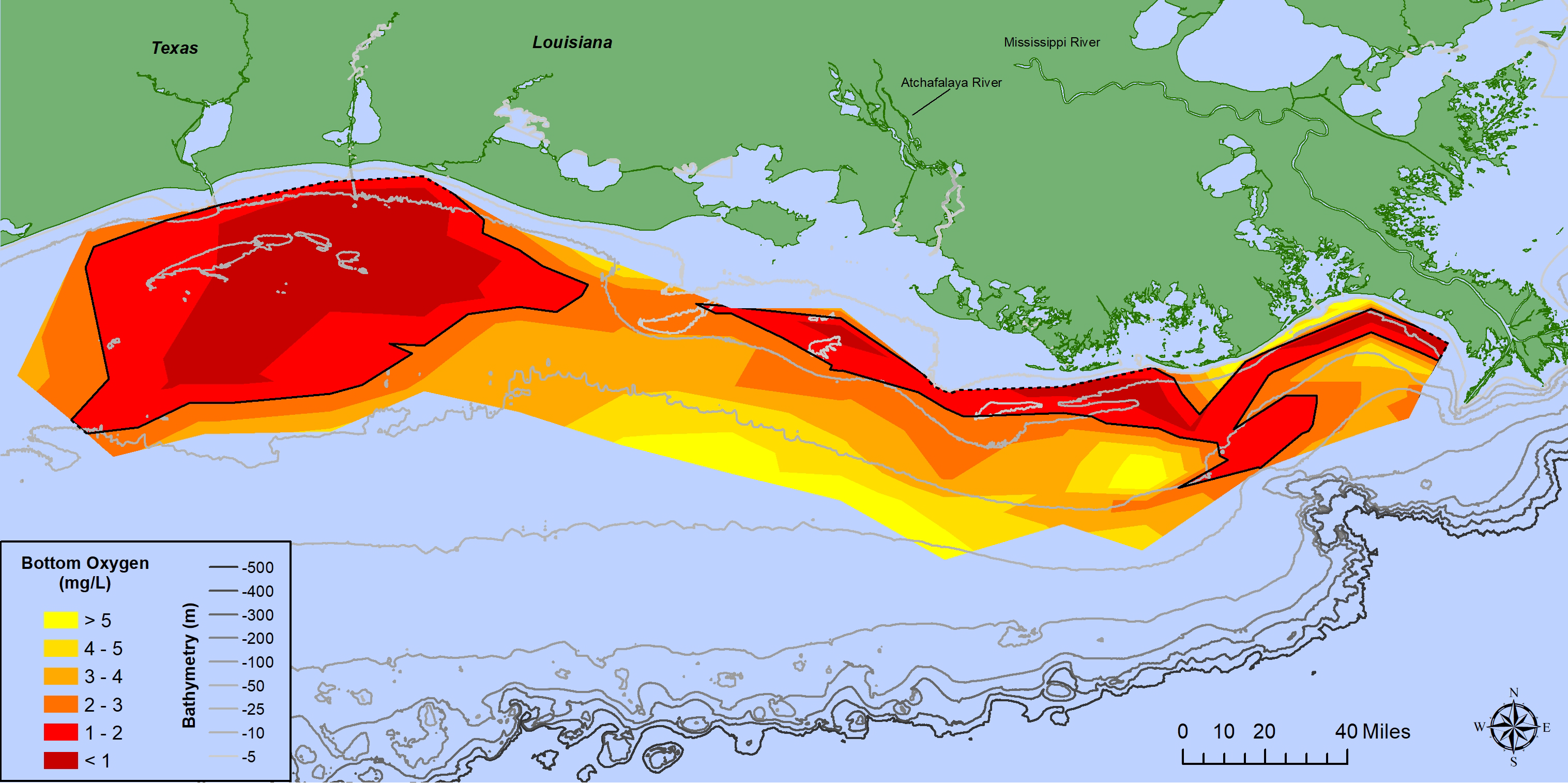

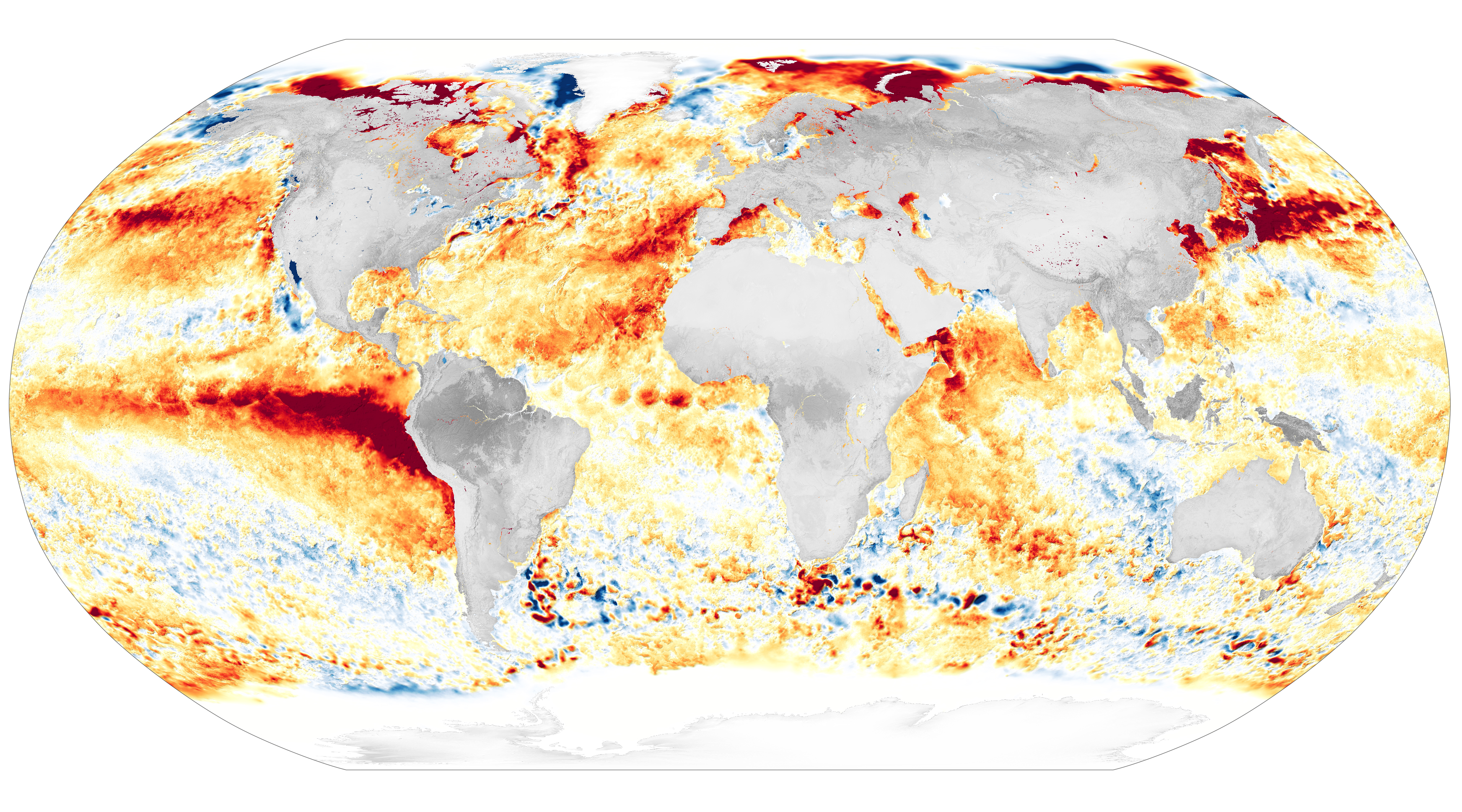

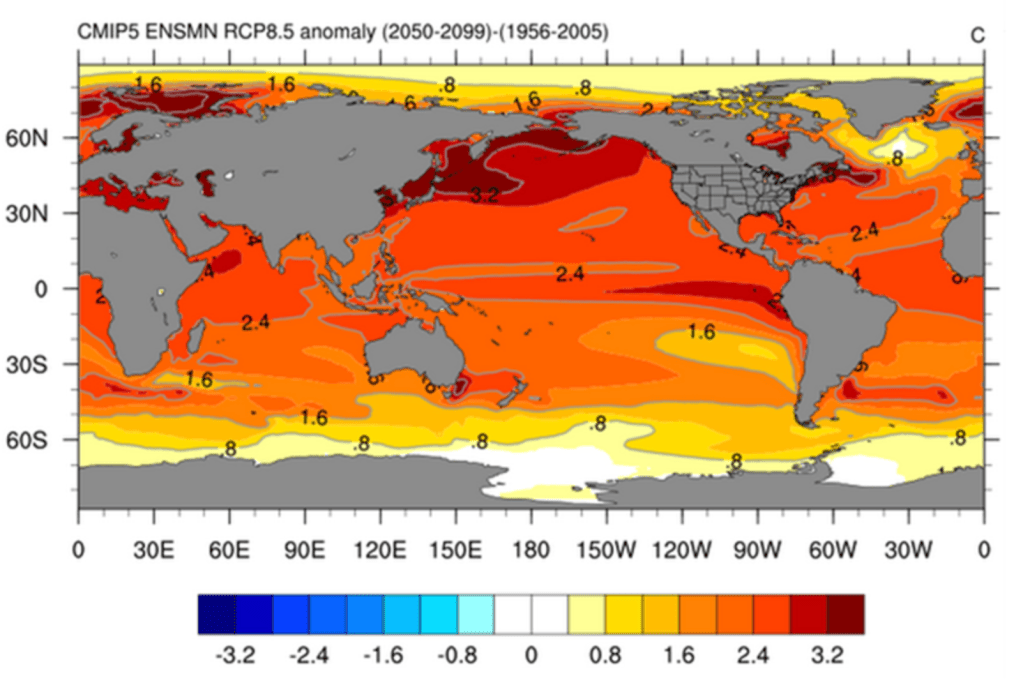

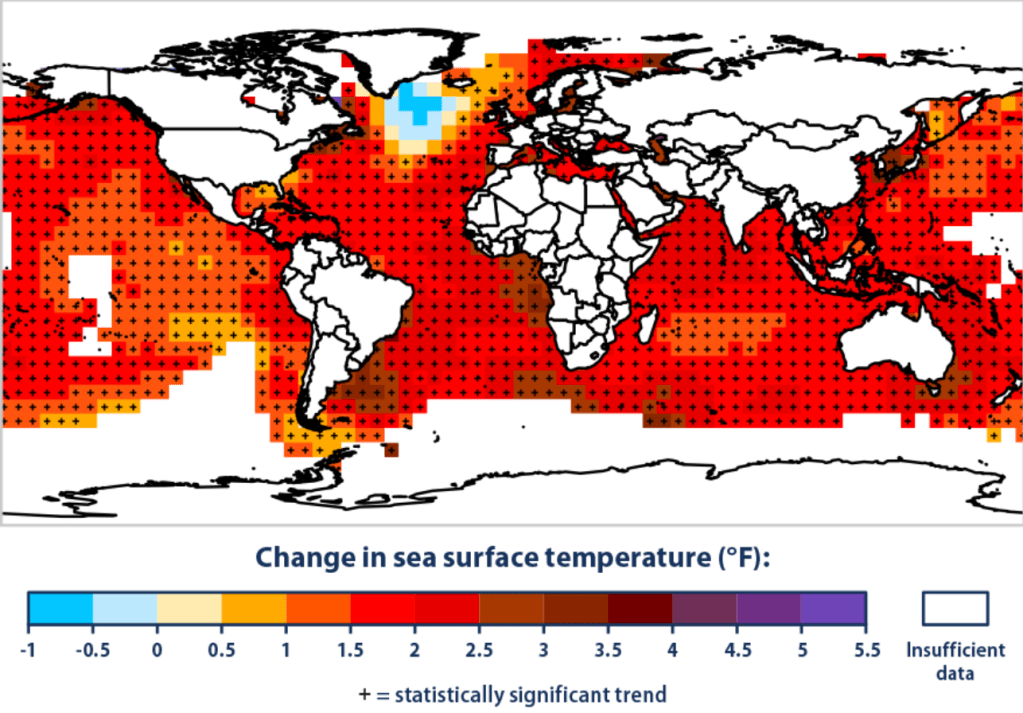

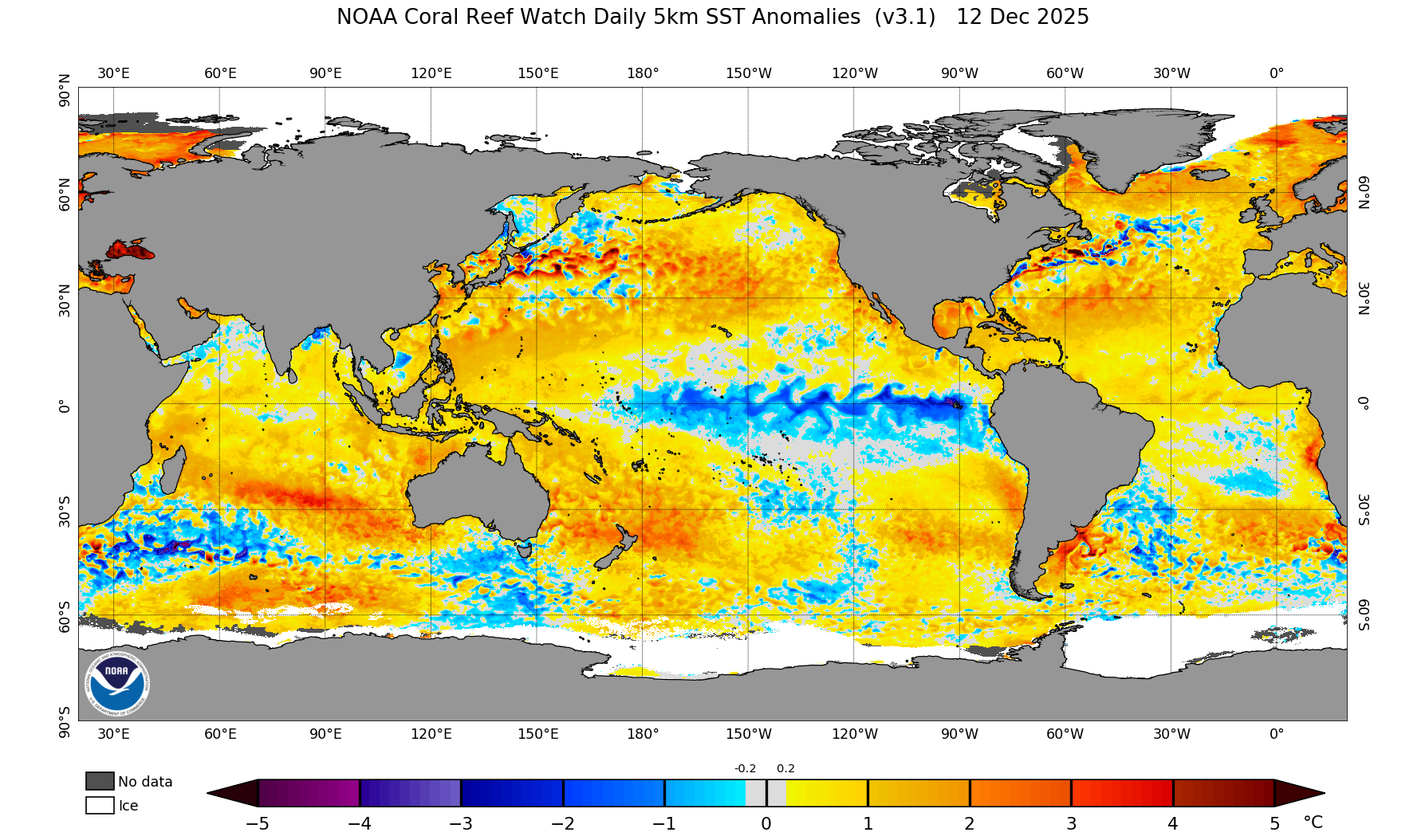

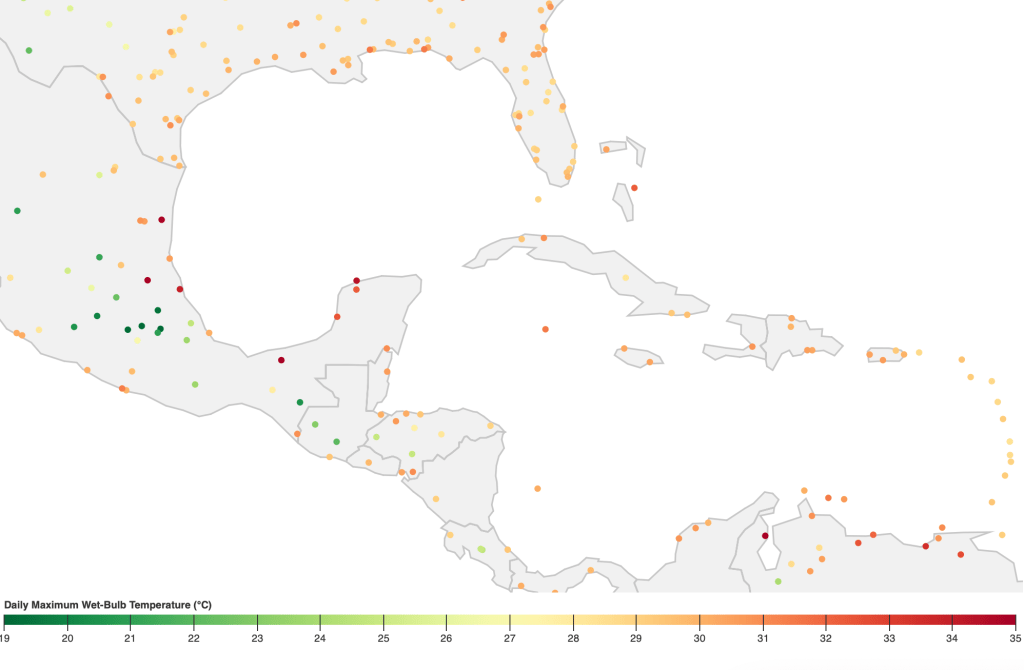

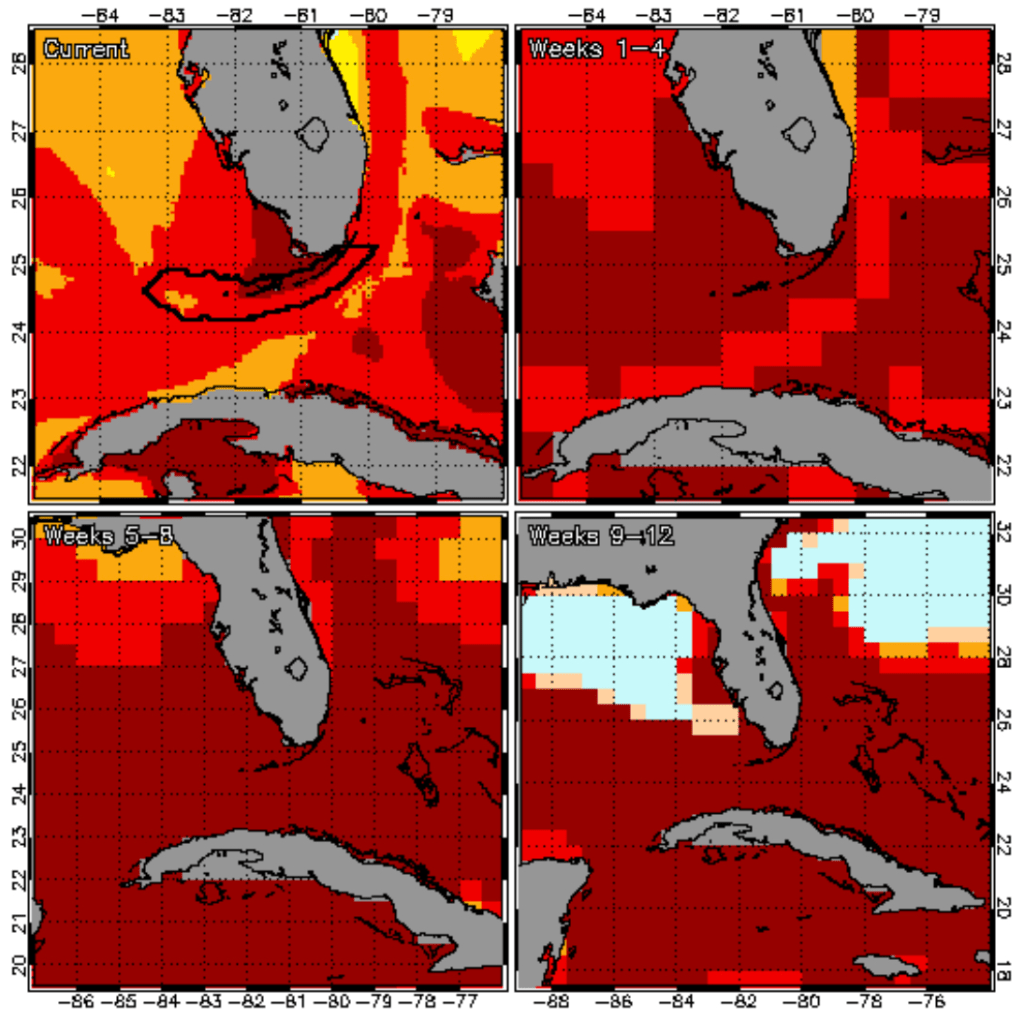

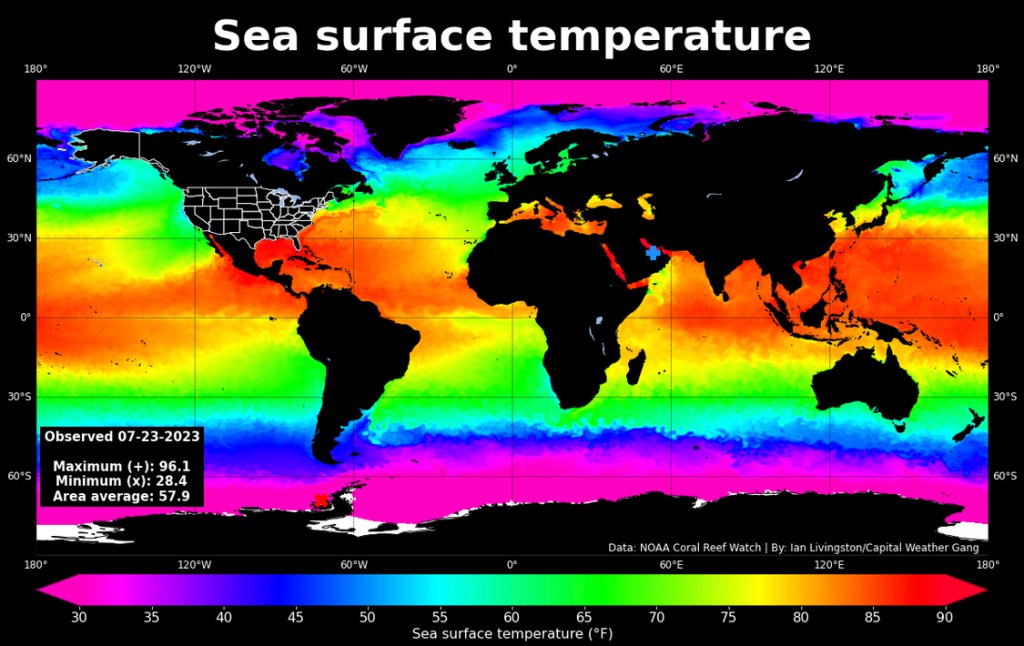

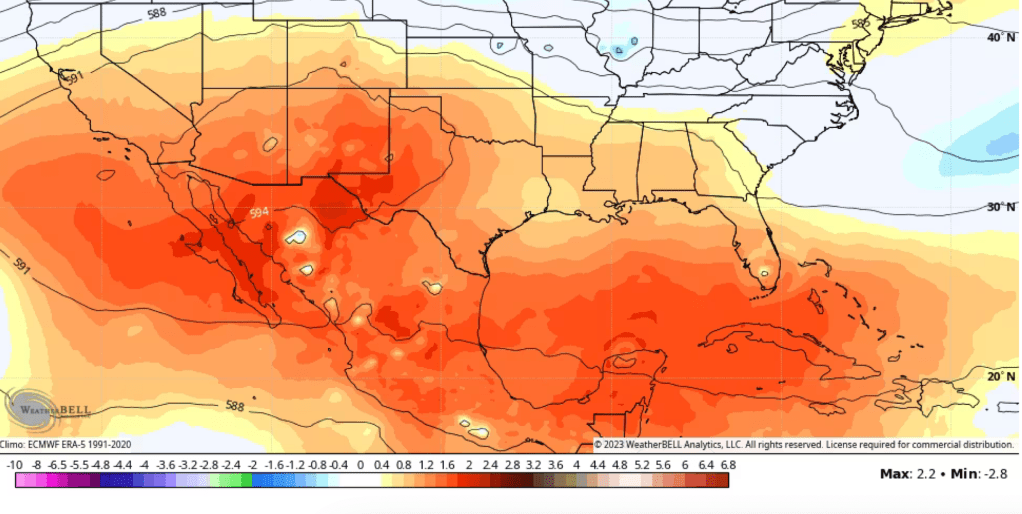

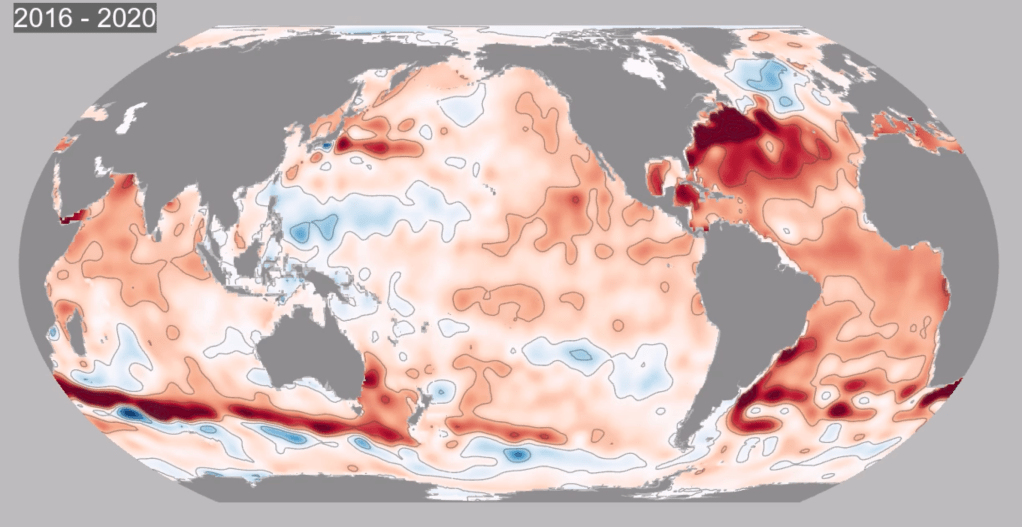

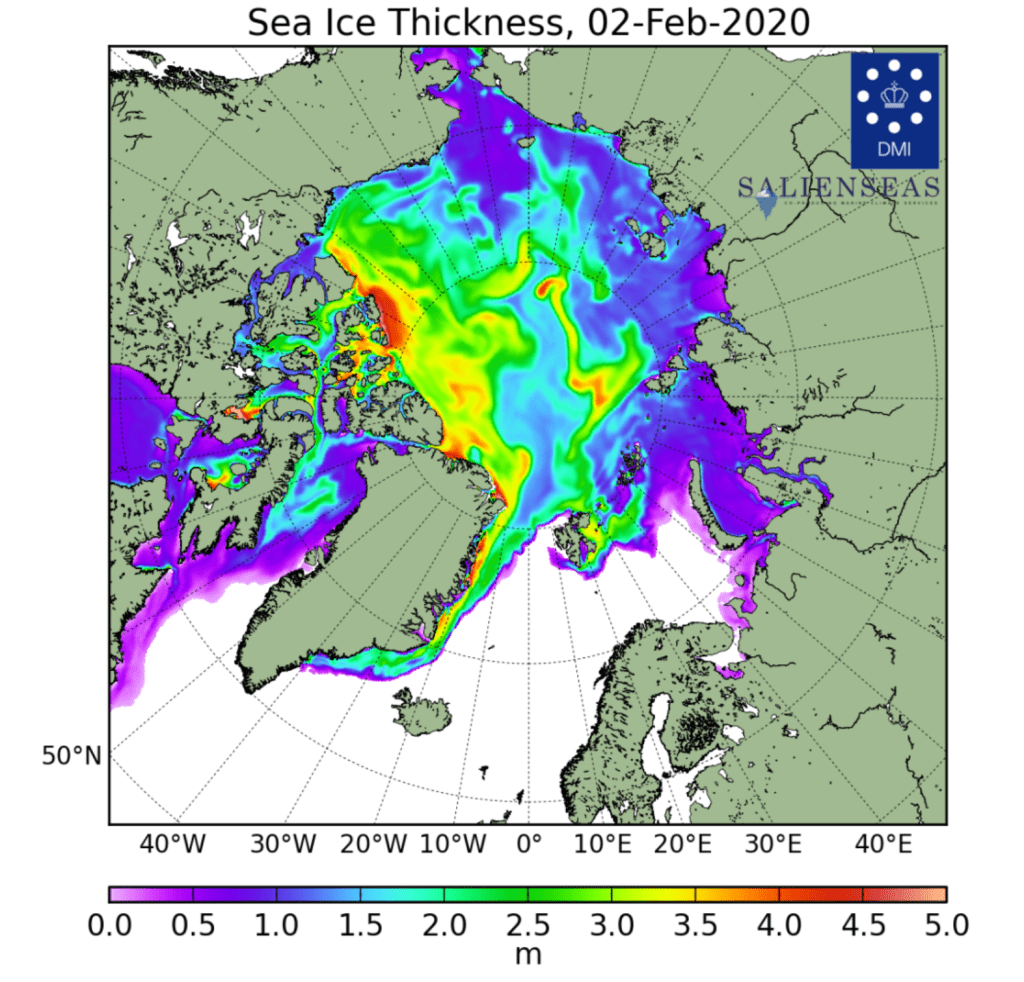

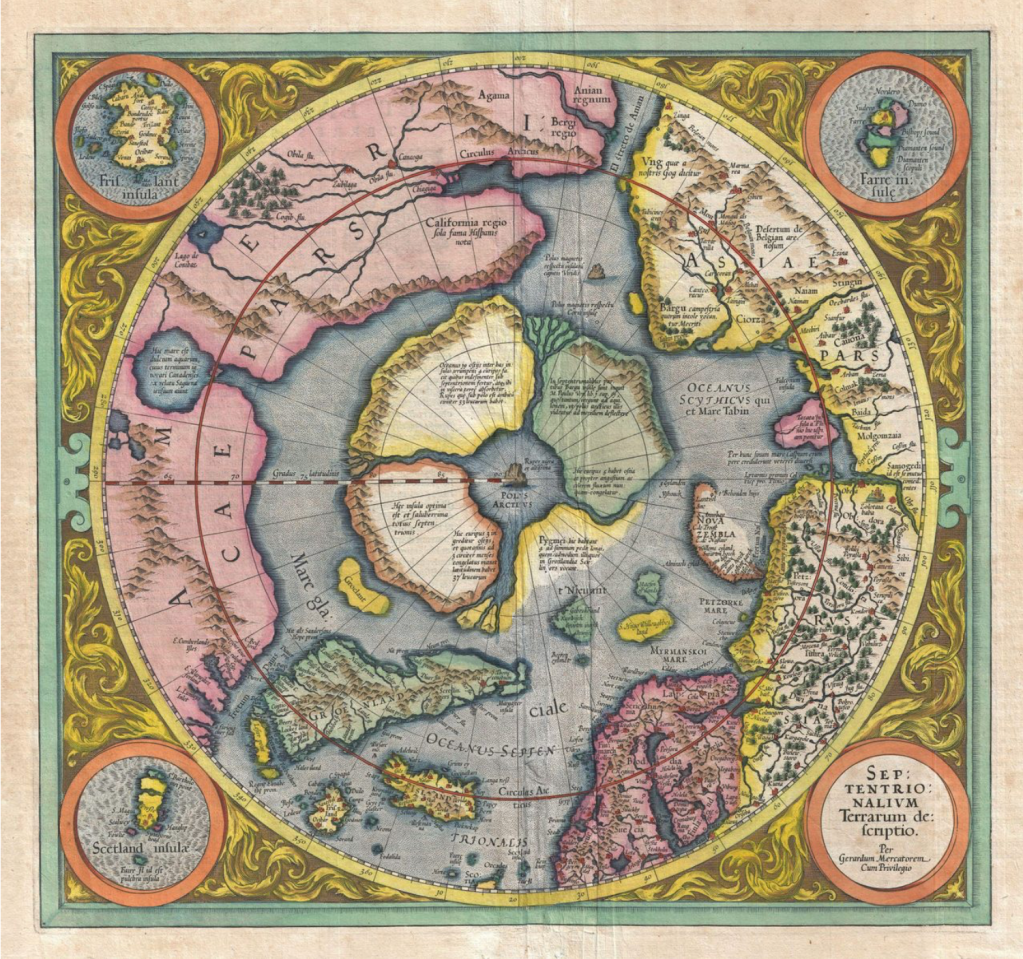

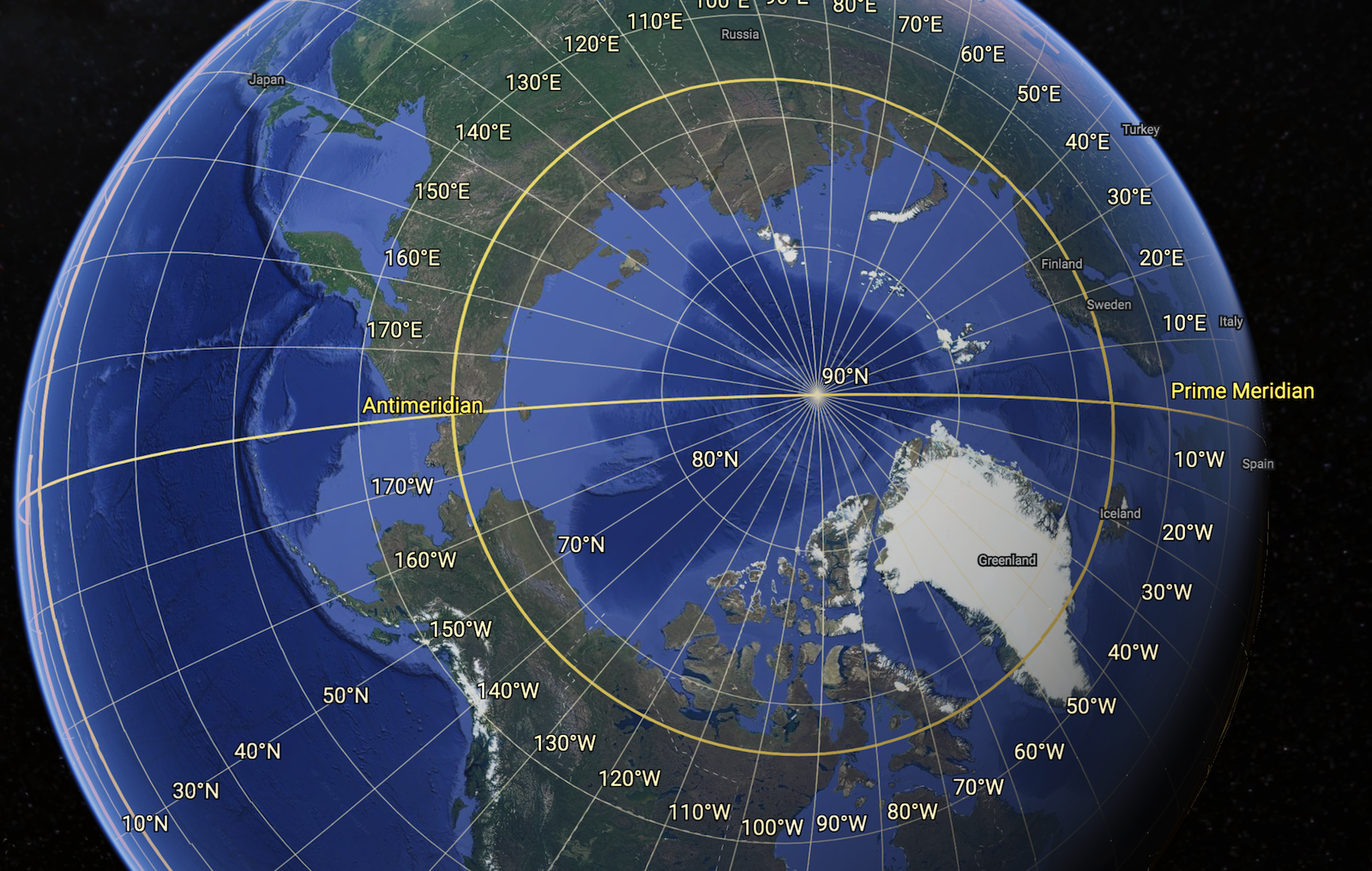

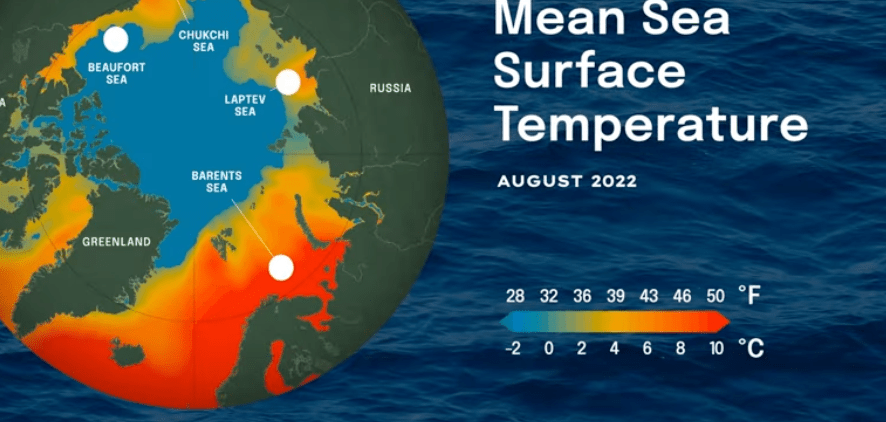

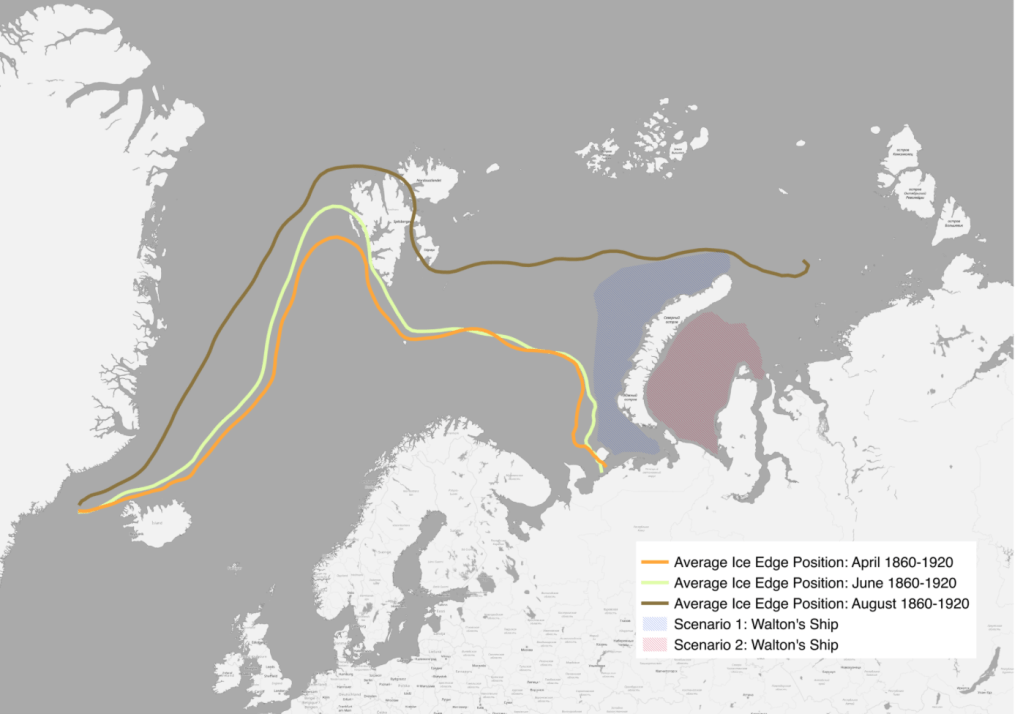

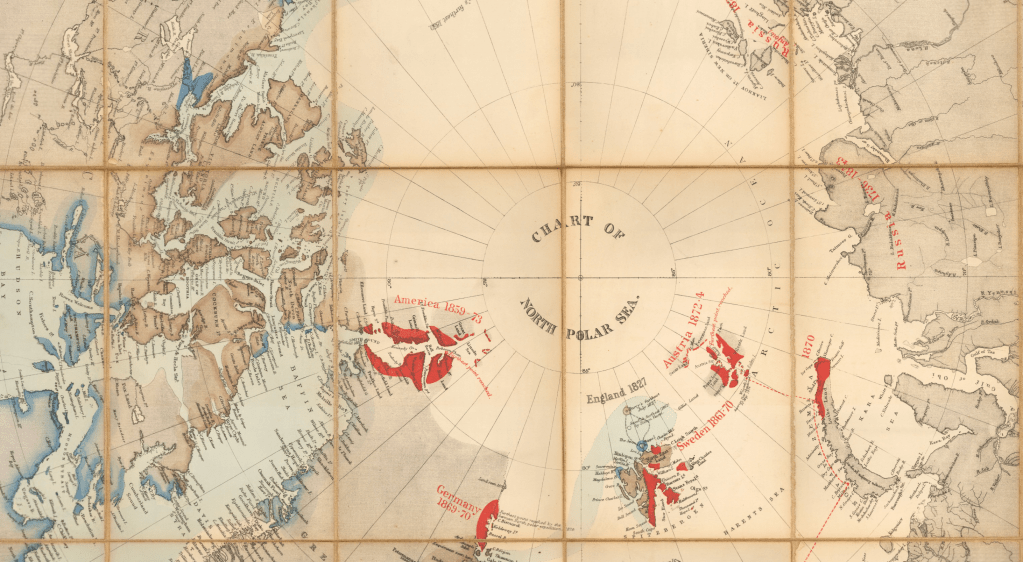

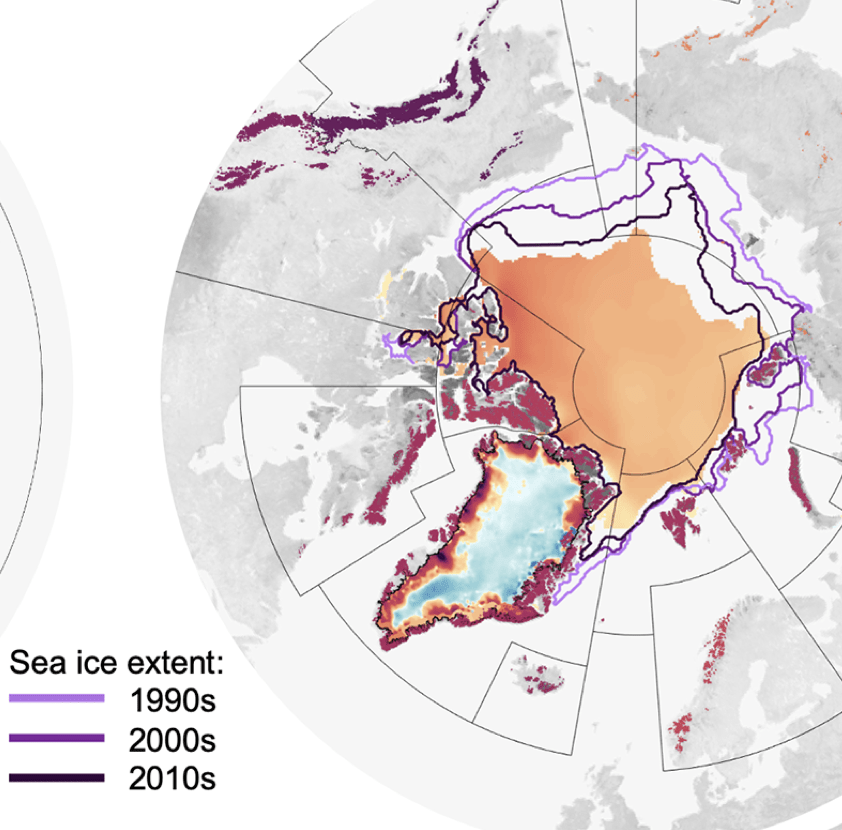

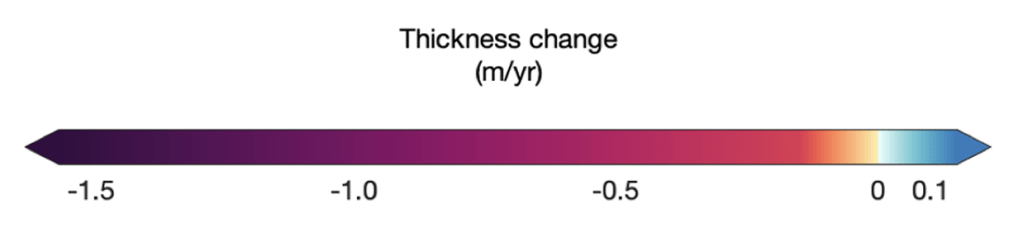

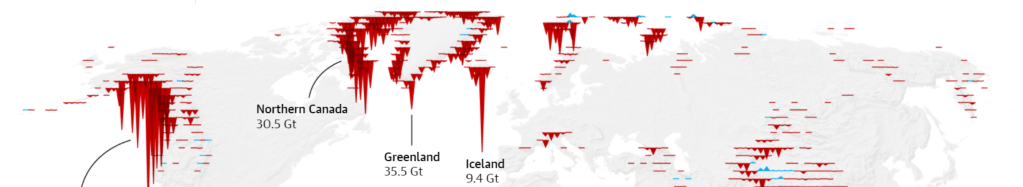

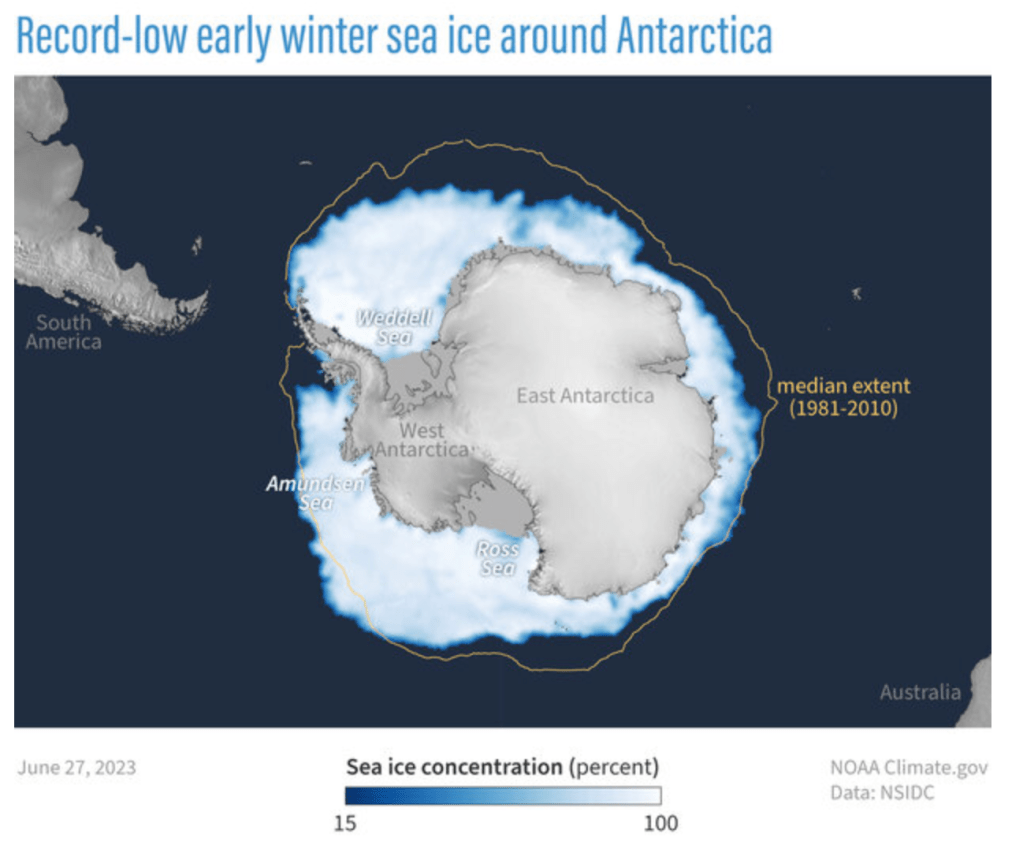

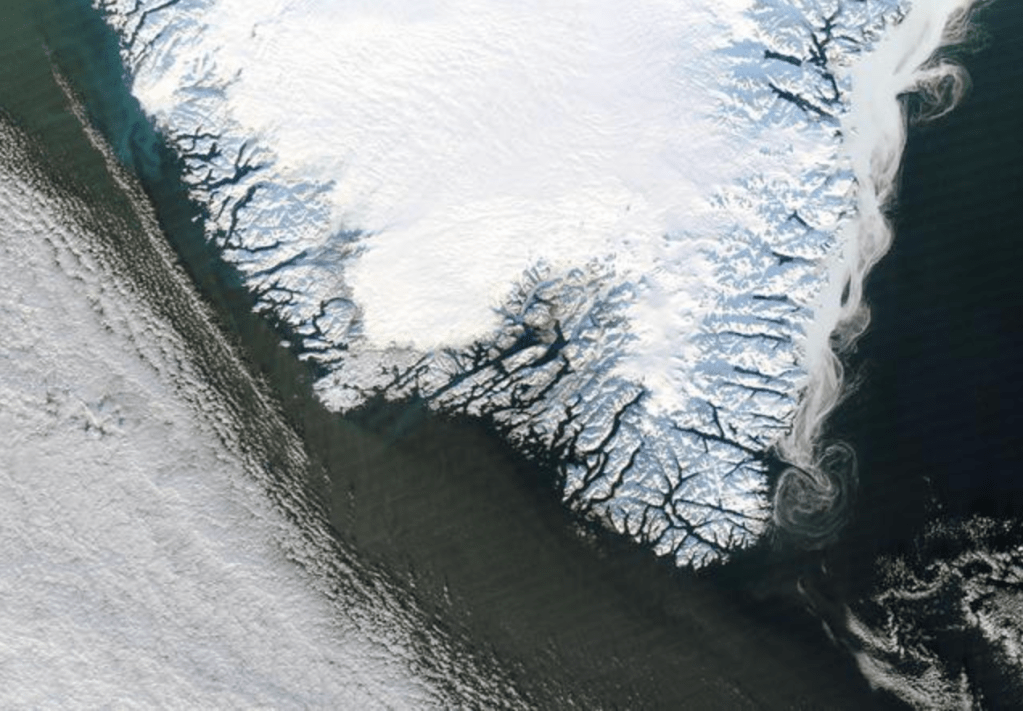

With global ocean surface temperatures shot way off the charts by mid-March, beyond forty years satellites have monitored sea surface temperatures, we’ve been struggling valiantly to map the changes in sea-surface temperatures, both globally and locally, in satisfactory and meaningful ways. The disruption poised to cascade across the planet in what might be the summer able to make climate change a less contentious issue of politics or partisan polarization. Maps of the remote sensing of surface temperature–sea surface temperature in specific–are shocking as they broker even deeper forms of estrangement, rendering the global temperatures against a baseline of the postwar period. The accumulated data from the first era of remote earth observation by satellite has generated a terrifying picture about which we lack a storyline, or a way to narrate our own relation. The problems of a metageography of impending global collapse that lacks any narrative resolution, more properly, and compels us to attend more closely to the conventions and imagery of how we map sea surfaces to interrogate more closely what we are actually seeing in such maps.

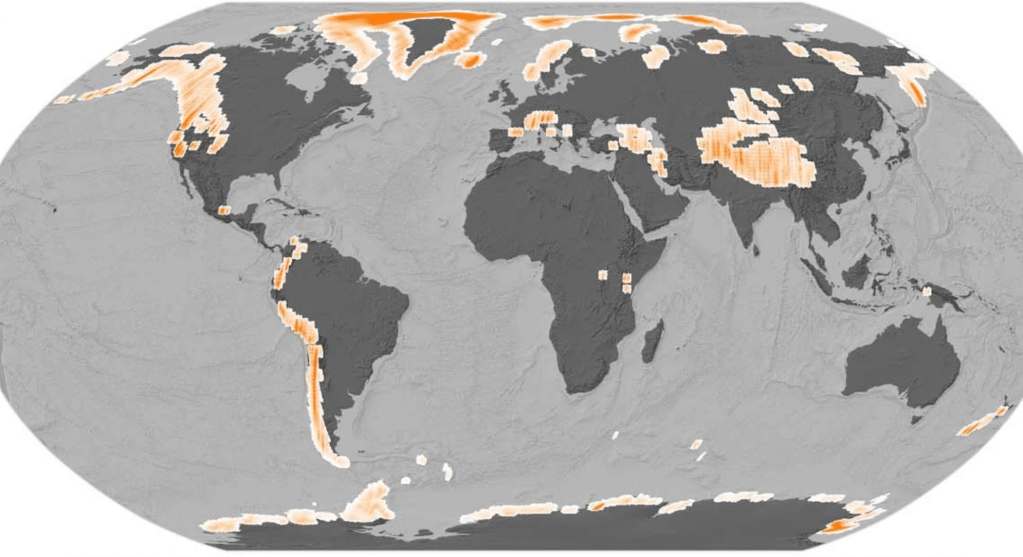

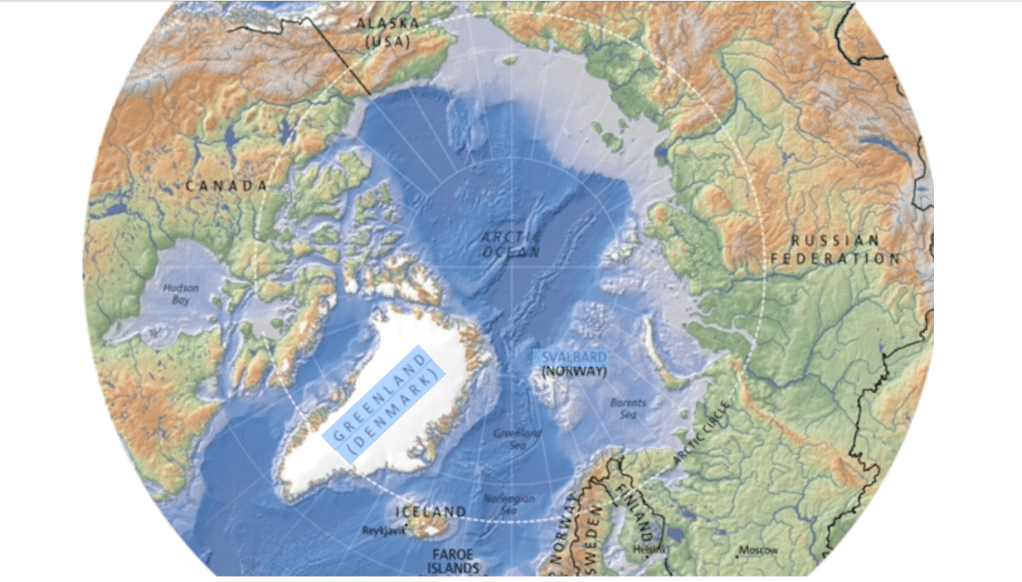

The totality of global warming are nowhere more evident than in the charts of sea-surface anomalies of temperatures, which pool red and orange on the planisphere in unearthly ways, but the correlation of remotely observed temperatures that deviate with standards of a century ago that showed foxing or burning over a decade ago, as the “hotspots” of intense rising temperatures near Greelnaldn, in Hudson’s bay, or off the coast of Maine and Siberia in July 2009 or even more strongly in September, 2011–but demand us to investigate the changing relation of land and sea.

July 2009/ NASA Earth Observatory

September, 2011/NASA Earth Observatory

–that have reached such record levels to lead Earth Observatory scientists to describe long-term effects of global warming by diagnosing that the global ocean “has a fever,” with disparities from past averages above three degrees C, not a lexicon of hyperbole, but suggest the inevitability of what early modern physicians would call fast approaching critical days–the discrimination of the moment when the patient will become “critically ill” or persevere, but that challenge us to classify the nature of such critical onset, as the ancient physician Galen felt fevers turn to more severe or worse forms at measurable moments, registering the temporal progression of fevers in his case histories that form the basis for modern clinical records to classify the effects of the fever in its ‘quotidian’, ‘tertian’ or ‘quartan’ stage. But we sadly seem to lack the same sophistication for record-keeping of global warming, in the age of the Anthropocene. If Galen distinguished fevers by the responses they required from physicians between those that were acute (‘fast’, oxys, or celer) and chronic (‘slow’, chronios, tardus), the action of this oceanic fever requires is particularly acute.

Although Galen suggested that the “best physician” would take care to distinguish and discriminate the causes understanding the imbalances of vital humors that he argued caused illness, the causes that underlie such entirely anthropogenic rises in ocean heat have been increasingly debated and even suppressed, even if there is more than adequate indications that the consumption of energy and burning of extractive fuels have creat4ed and exacerbated temperature anomalies–and little interruption has occurred in the increased extraction of oil and gas under the optimistic slogan of “energy independence”–not actually providing or producing sufficient energy for a nation but exporting more fuels than one imports.

August 21, 2023/NASA Earth Observatory

The startling results of remote earth and sea observation stands as an odd counterpart to the iconic “blue marble” that became such a slogan of aspirations to global environmentalism almost a full half century ago. Yet the layers of these mapping tools seem, as the rage for composite forms of IKEA furniture, that arrives in assemblage components, to suggest a readymade far from Marcel Duchamp, as if to respond to the magnification of an imagined “migration crisis” by which the nation is challenged. If that crisis may be in fact false, or imaginary, even if migration rates have changed, and most migrants have arrived in the United States for work. The assemblage of the Border Wall is an elision of the identities and the experiences of migrants themselves, or the routes they travel or their work and trades.

IKEA Börder Wåll (2017)

The layers of our environmental maps of ocean temperature anomalies carry ideological presuppositions leaving us purblind to the massive scale of ecological changes in the global ocean, or ability to steer the results of global warming and planetary change by better grasping its effects, rather than creating indelible images of fear. As the practicalities of building a “Border Wall” with the cheapness Candidate Trump had promised, the proposal to create a readymade Börder Wåll that was a far more affordable option at less than $10 million–exactly $9,999,999,999.99 with a five-year guarantee–used the iconic instructions of the Swedish furniture company to imagine a version able to be assembled by screws and Allen wrenches whose pressboard standing a full ten meters tall. If the more affordable assemblage of the border wall was a potent figure for the political emergence of a salesman with little to offer the nation save the image of security, the layers of the remotely sensed map offer a similarly terrifying othering of the global surface, as if the known world were suddenly at variance from the world that we knew, if not destabilizing the very blueness of the seas.

In the famous “Blue Marble” images taken by those aboard the final Apollo 17 to the moon in 1971, we recognize the continents bathed in a sea of bright blue–continents we recognize from the map, but now see, for the first time, a powerful map, lit by the sun before our eyes. The blue nature of the earth is its most overwhelming aspect, however, unlike a map, as if we can see the sea below sparse cloud cover against the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian Ocean visible from the polar ice cap, with the earth’s other continents for the first time ever: we recognize and identify Africa, Madagascar off its coast, and clouds swirling over the ocean, no nations in evidence. It is othered, but made more recognizable, defined more than by nations by the brilliantly illuminated azure of oceanic blue that seems for all practical purposes to dominate the world’s surface beneath clouds.

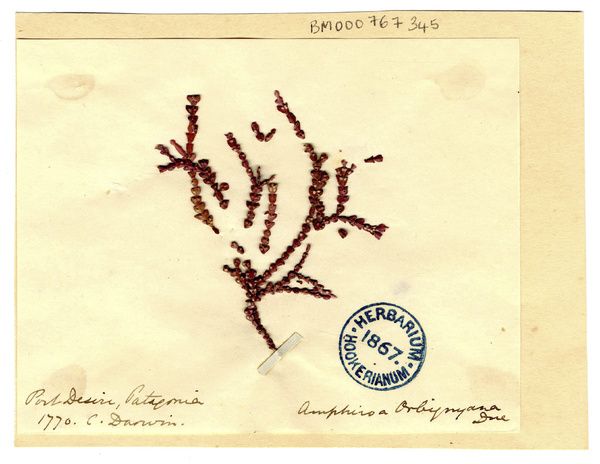

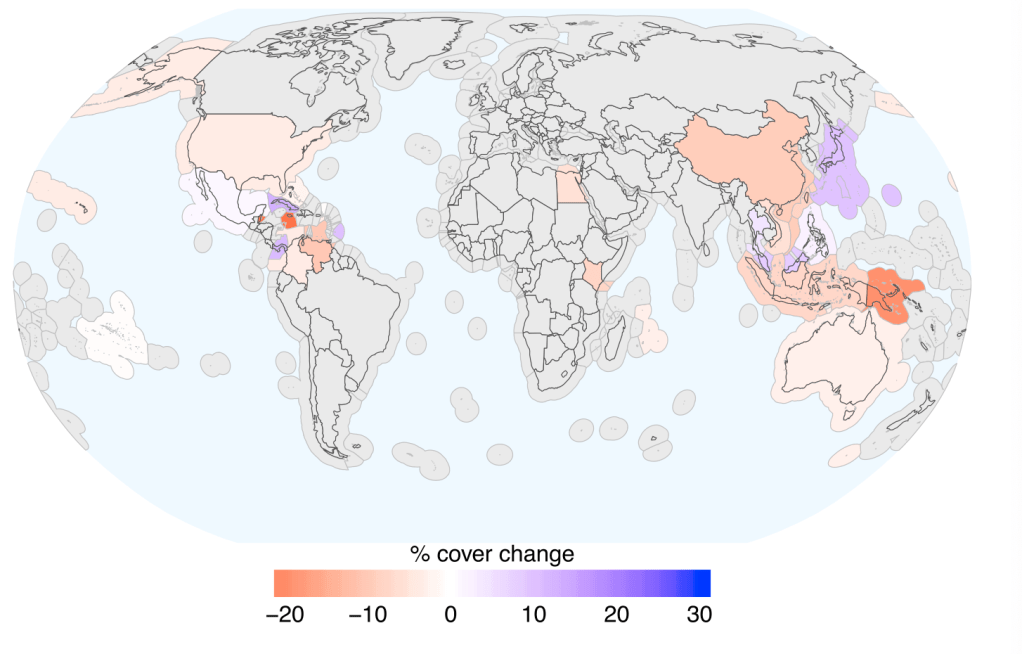

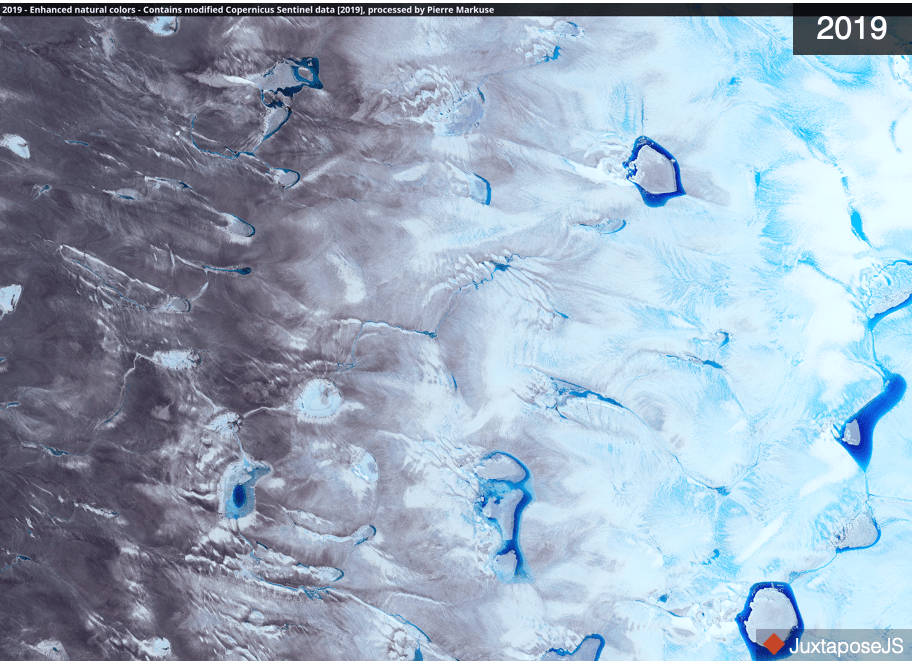

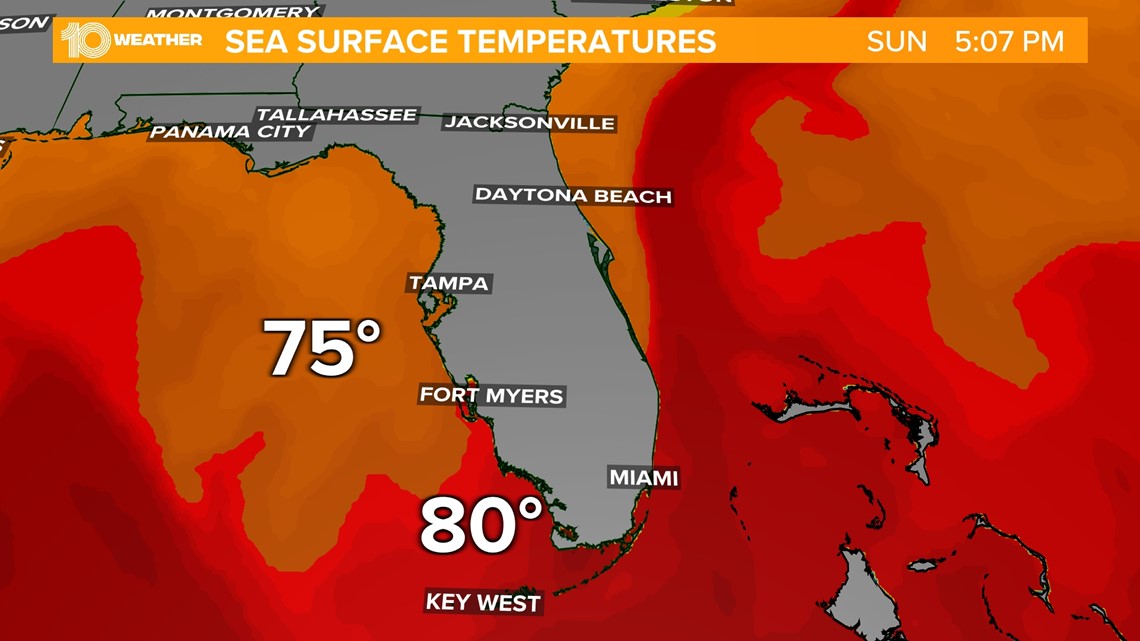

The icon of “Apollo’s Eye” soon the most reproduced in world history–an image of technological progress, but also a snapshot from space, taken off-hand at 20,000 miles per hour, a disappearing or receding planet, lit up by the sun, even thought the 70 mm camera on board was not intended for non-scientific ends, and the aweing nature of the film snaphsot was only recognized as it was develped by a film technician as a portrait of the planet. Although its authorship of who reached for one of the several Hasselblad’s not stowed away for more properly “scientific” purposes on the Moon in order to taken one of the great images of space tourism: one of the first remotely “sensed” images of the earth tilting toward the sun’s rays illuminates its blue oceans that are recognizable under swirls of cloud-cover, revealing recognizable continents–Africa; South Asia; Antarctica–from a perspective never before experienced. MODIS satellite reveal show the current oceans no longer as blue, but greenwith phytoplankton as oceans warm the acceleration anthropogenic carbons in the ocean, incubated by human-caused climate change or “planetary warming.” The Blue Marble now definitively receded so that it seems not a Hasselblad image but might be a photoshopped, the seas no longer offer an image of the Blue Marble. And nowhere is the alteration of sea-surfaces evident than in their temperatures, a gradient relatively new to GIS, but all too compelling if also problematic to render in convincing ways. Can we better render the layers of the warming ocean in ways that allow us to better come to terms with the effects of planetary warming?

Blue Marble Photograph by member of Apollo 17 Crew Commanded by Eugene A. Cernan

The Blue Marble image was widely reproduced in global newspapers. But it was only recognized as of interest soon after it was developed by a technician. What NASA called “AS17-148-2272” would be quickly adopted as the “Earth Day” flag. But if it was never definitively credited, and was only in a sense “discovered” by the technician who developed it, its appeal grew as it was consumed by an audience eager to imagine what the members of the space flight teams saw, and as they existed the Earth’s atmosphere. Its immediately recognizable emotive and inspirational power as an image of the earth’s totality as never seen grew, in part, because it was snapped as the winter solstice approached; the full illumination of planet Earth’s vibrant blue oceanic surface appealed as a moral centering, as it became a basis for the Earth Day Flag. Its recognizable nature was not only the crispness of its geographic outlining of continents as they lay and appeared on a terrestrial map,, but, unsurprisingly perhaps, as they echoed and modernized the very claims of divinity that early American environmentalist Henry David Thoreau found as he left Concord ‘s society and his daily job to contemplate the blue waters of Walden Pond he had praised as “cerulean” a hundred and twenty five years earlier, in a wor that was widely read by modern environmentalists in the 1950s and 1960s. The deep blue ocean surfaces from the polar cap of Antarctica to the Mediterranean, around the coast of the entire African continent and stretching to the Persian Gulf, was a counter-map to national maps of borders familiar from school maps, but asking we alter perceptions of the “blue marble” delicately suspended without strings as an image of strength and stability, without any, or at least apparently without any, technological mediation.

But the image of the blueness of those oceans is now undeniably an image that has receded in space, not an eternal image of timelessness, and transcendence, but a definitively receding past, as satellite observations of unprecedented oceanographic detail and range that allowed high-quality ocean color data by the MODIS-Aqua satellite systems announce an inevitably greening of the surfaces of the global ocean. The blue marble icon i, confined to the past, and an artifact of the past, after the anthropogenic alterations of phosphorus and carbons in the global ocean has, in an era of anthropogenic global warming, so boosted phytoplankton populations to recolor the ocean. The new surface ecosystem indicate new variety of microscopic organisms photosynthesizing in the global ocean, and carbon-enriched phytoplankton populations whose abundance in global oceans have “turned the seas green” and “othered” the ocean that was once such a pristine blue.

The iconic call to environmental consciousness map of the blue-drenched seas taken 28,000 miles from Earth at a point where the manned spacecraft crossed the point an Earth fully illuminated by the sun is definitively of the past. Eugene A. Cernan, the commander of the last manned lunar mission who claimed to have taken the photograph claimed to capture the crew’s collective astonishment at the spaceship’s transit before the sun. But he has returned multiple times to the sense of deep surprise by which undoubtedly melancholy window-gazing brought a sudden defamiliarization of earth and disorientation of the observer as much as a feeling of transcendence. It was removed from technology, but made him the most privileged observer of earth with a clarity and simplicity that had in fact been never experienced in history. The placement of himself was as strongly resonant as the fleeting nature of the perspecive, and “Do you know where you are at this point in time and space, and in reality and in existence, when you can look out the window and you’re looking at the most beautiful star in the heavens — the most beautiful because it’s the one we understand and we know, it’s home, it’s people, family, loved, life — and besides that it is beautiful?” The stunning image comprehending oceans and continents with “no strings holding it up,” “in a blackness that is almost beyond conception” in a soothing defamiliarization of awe.

The “blue marble” immediately hat was reproduced globally in print newspapers was an icon of globalism and an image of transcendence before it was an icon of environmentalist Earth Day that would spur a new consciousness of those blue waters’ preciousness and purity by showing them as if they were indeed Walden Pond. The photograph registered an oceanic expanse that appears timeless, and so intensely blue, a pocket of living life that might be modern version of Henry David Thoreau’s praise of the transcendent vitality of Walden Pond’s “cerulean” blues that reflected the sky so intensely as a mirror. (Let’s dwell a bit on this comparison: if Thoreau described the pond as “the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature” as “earth’s eye,” “looking into which one the beholder measures his one nature,” and his most prized companion during in “this mode of life” away from Concord, as he grew “suddenly sensible” of a sufficient space nature afforded, we are filled with dread at maps of rising surface temperatures that seem to bode an end to seasonality.) The awe the Apollo 17 Commander Eugene Cernan claimed to be compelled to snap the first image of the earth’s surface, entirely illuminated by the sun’s rays from Apollo 17, the south pole tilted sunward before the winter solstice and oceans illuminated as a seat of life seem a modern updating of Henry David Thoreau’s sensation of being in a privileged site of contact with the divine at Walden Pond. (Cernan’s claim was contested, but he felt the image akin to a re-centering of self.)

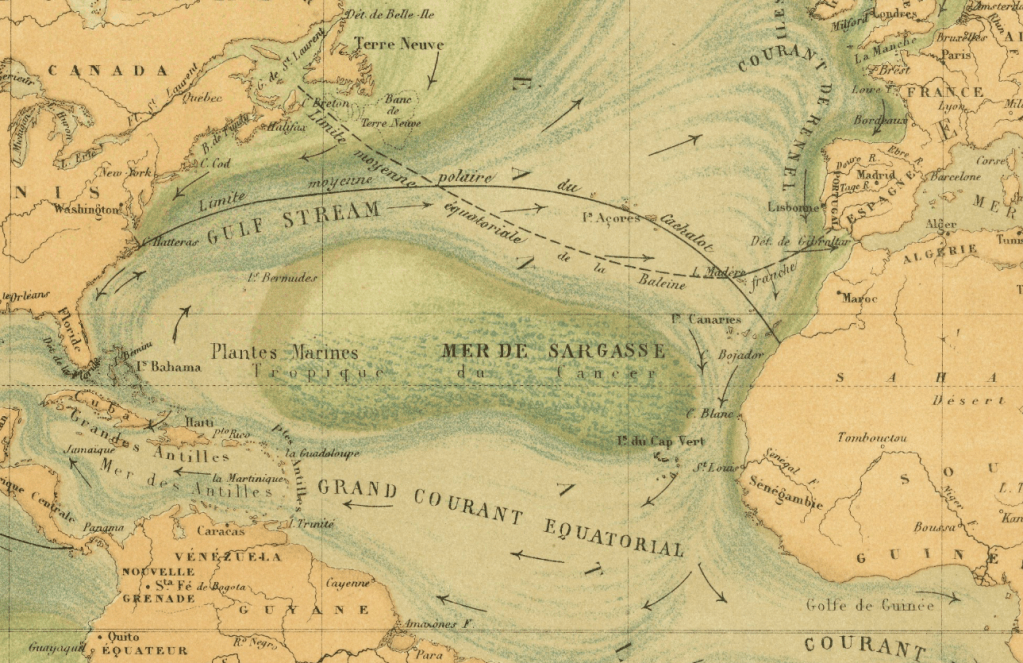

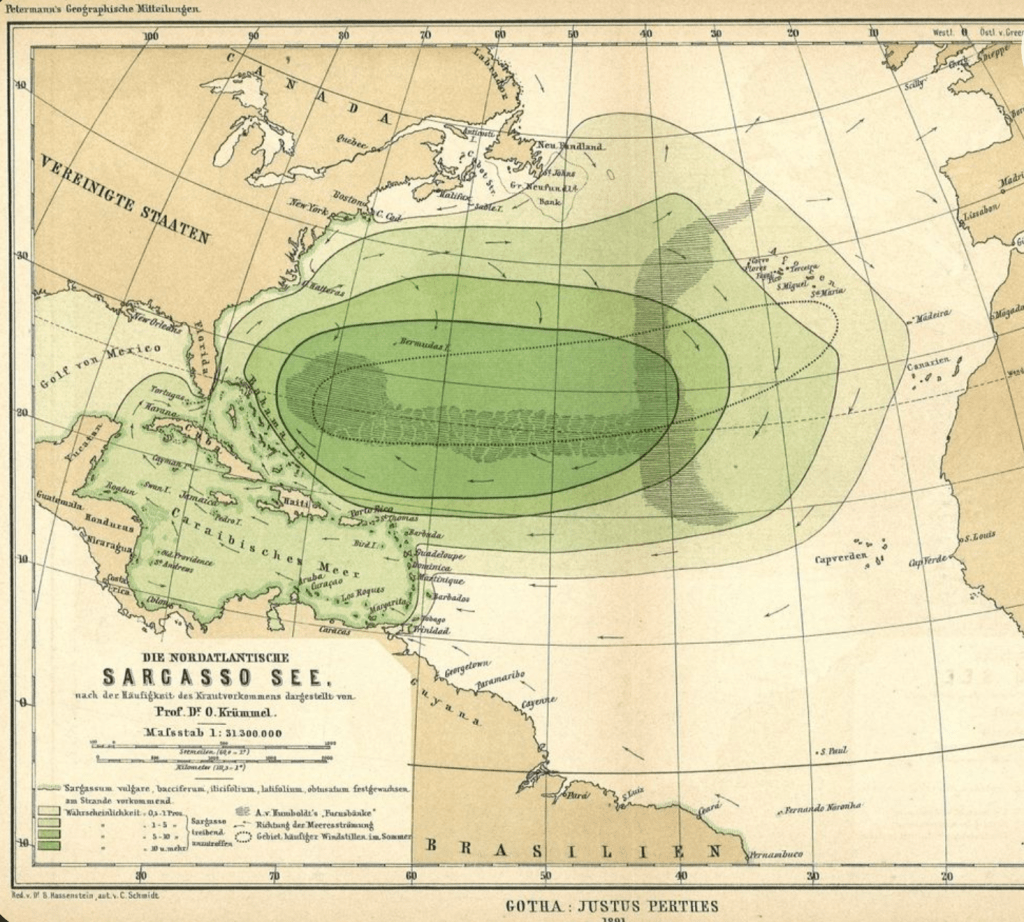

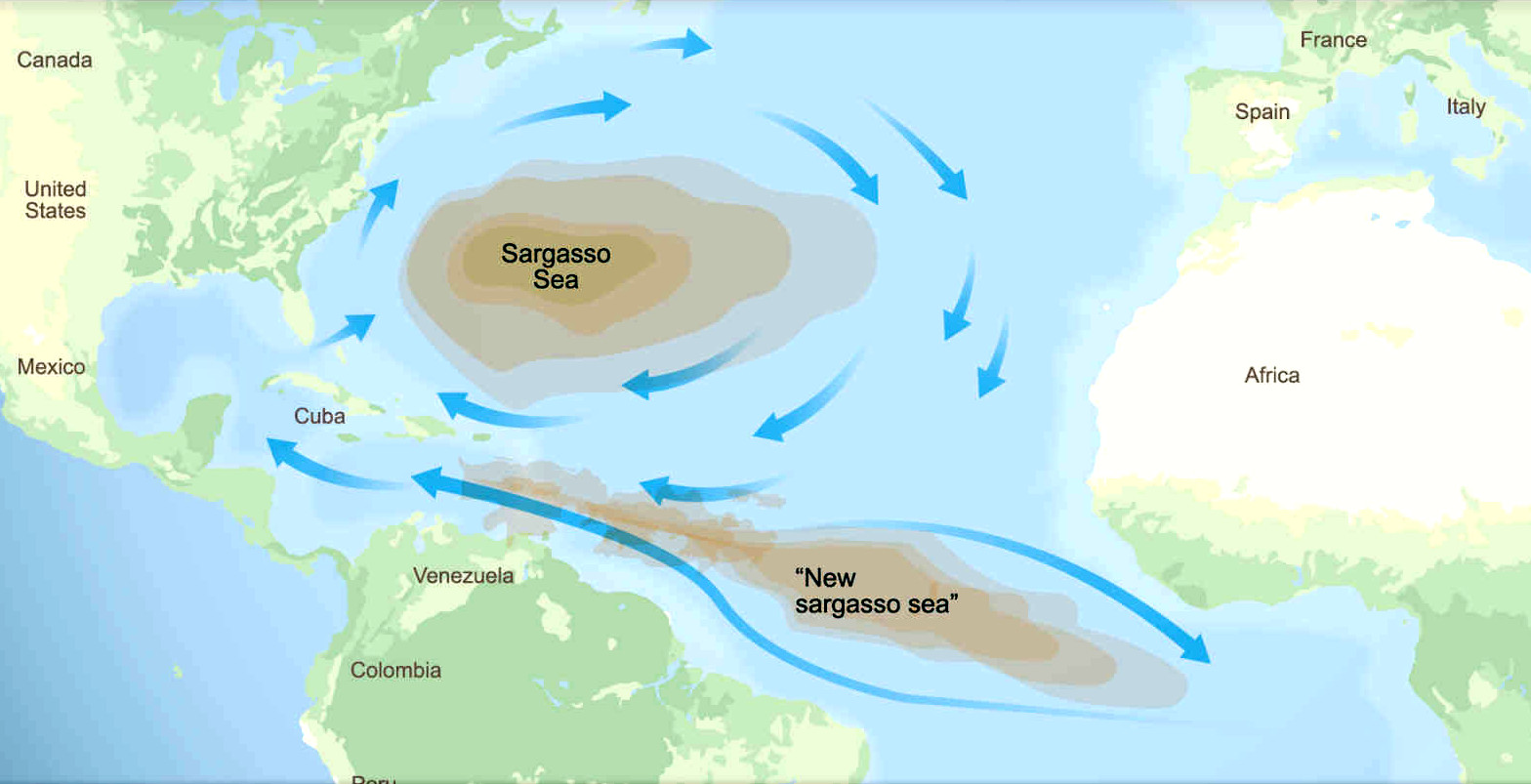

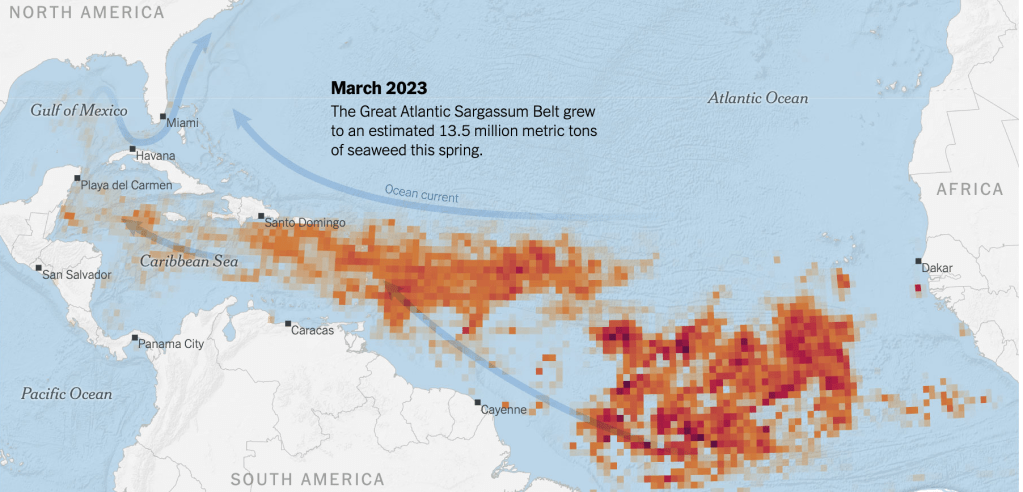

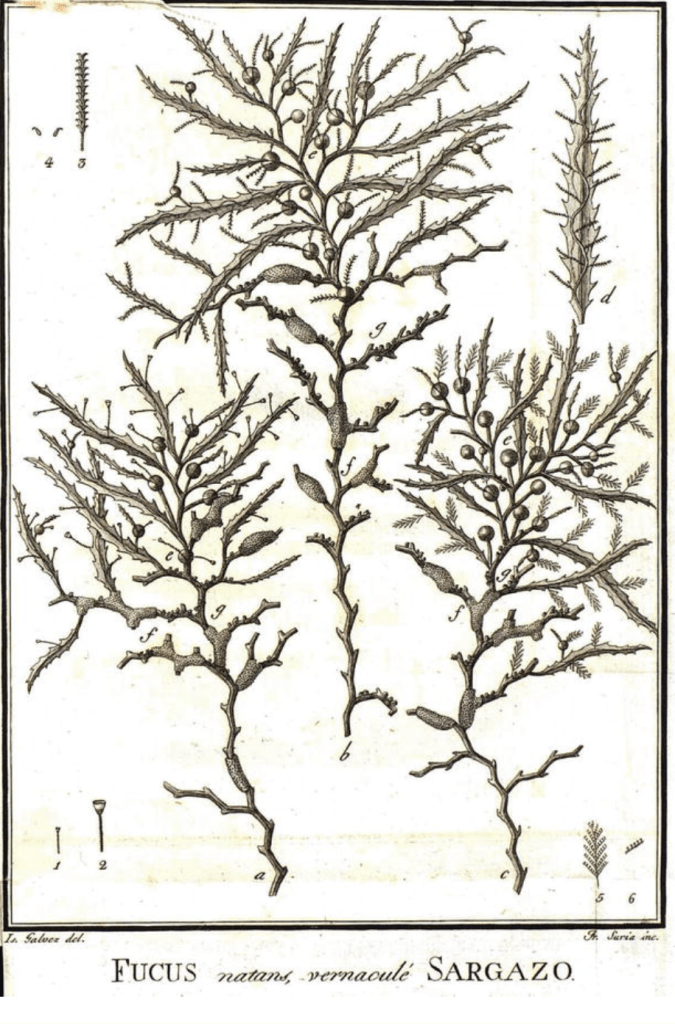

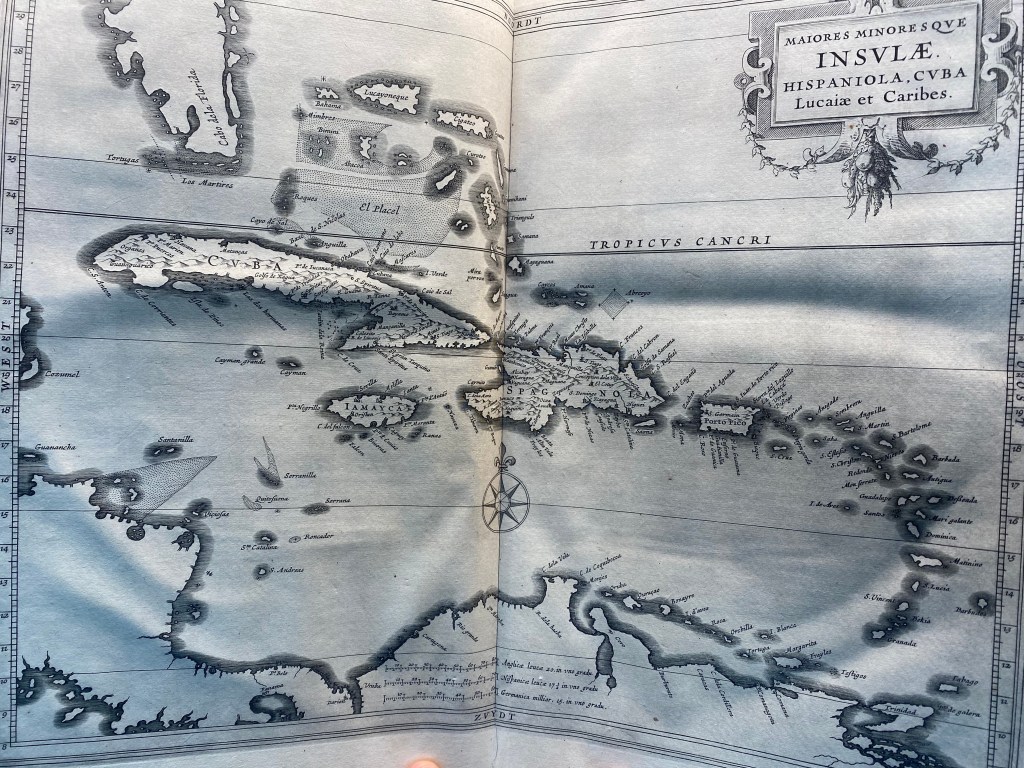

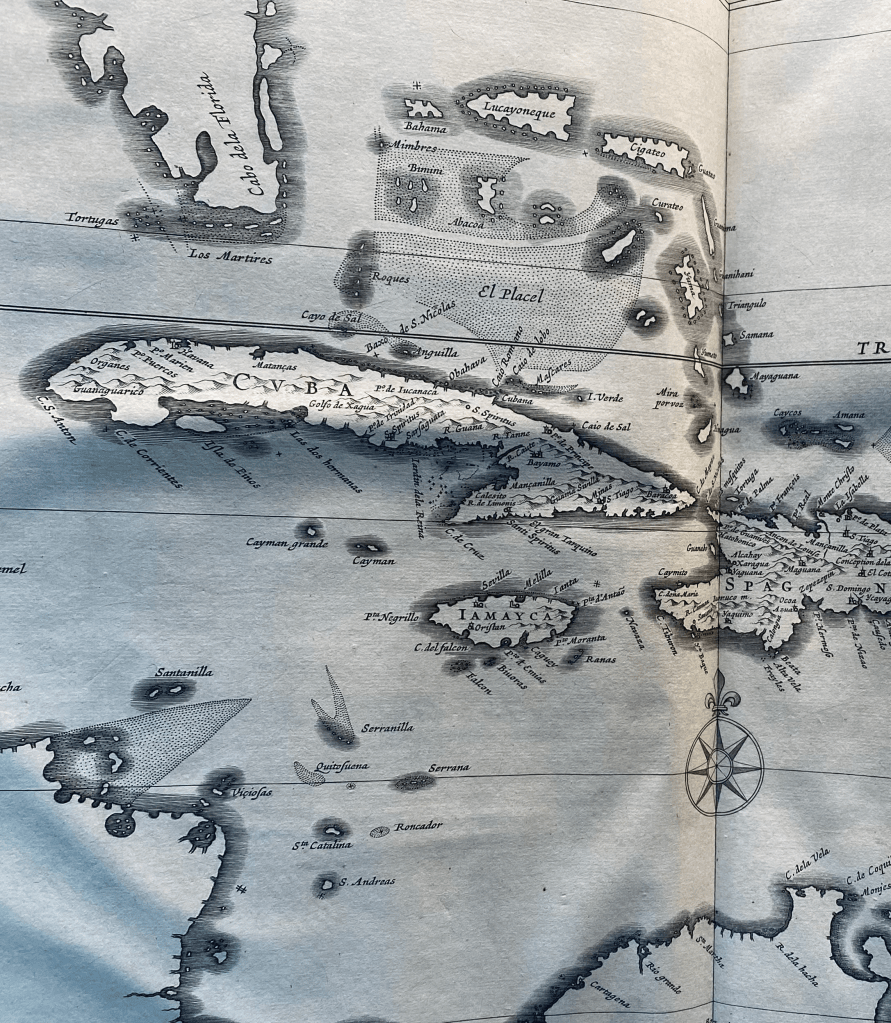

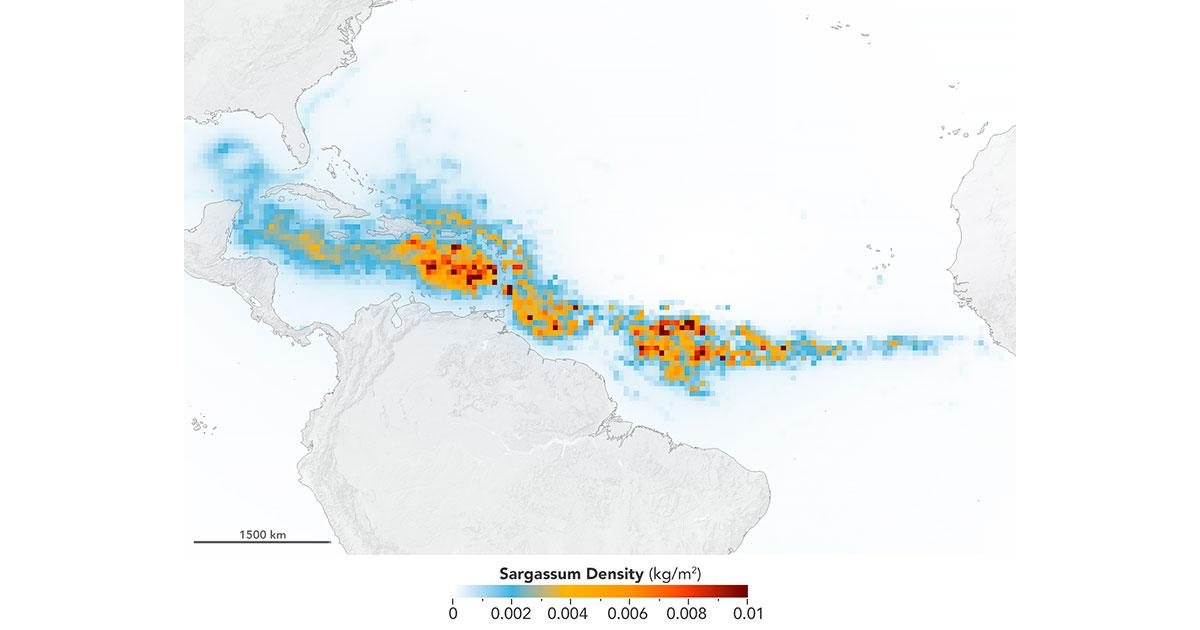

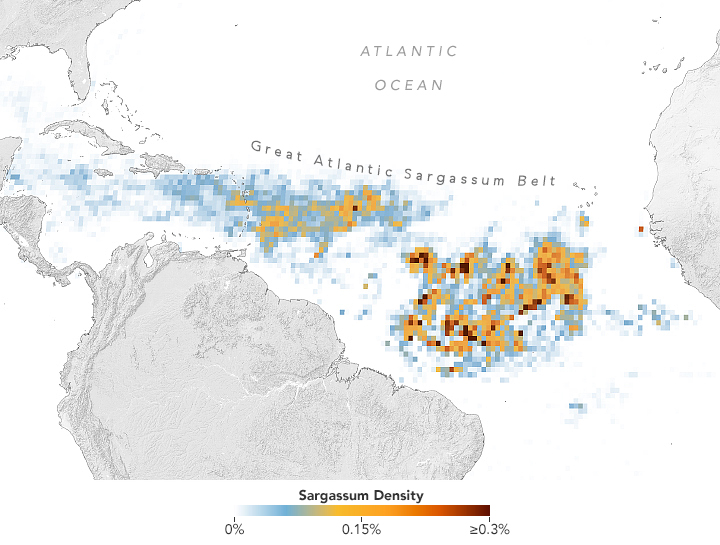

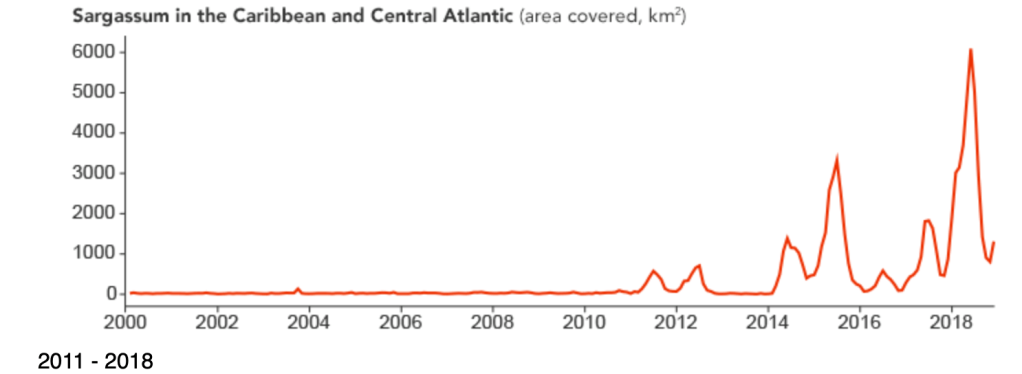

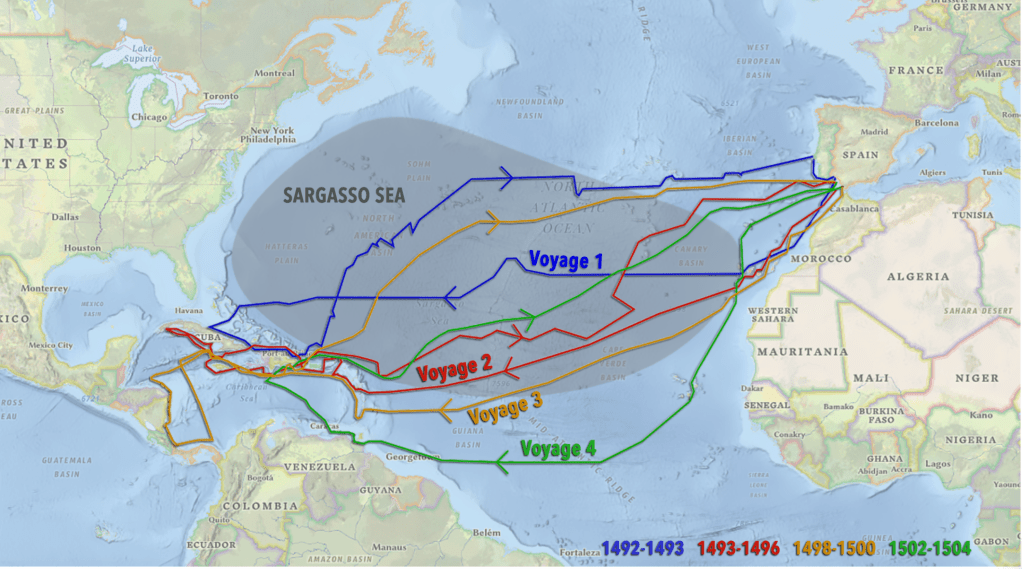

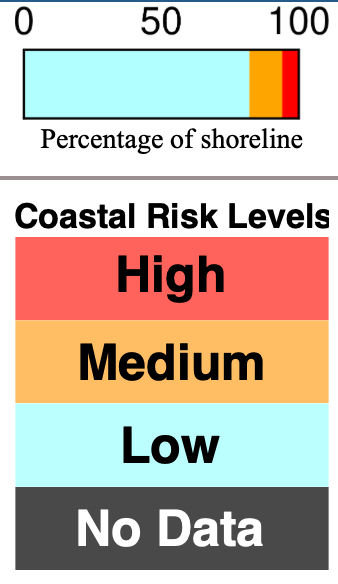

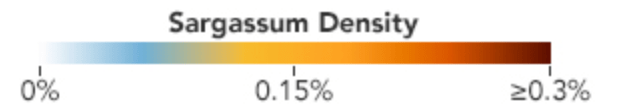

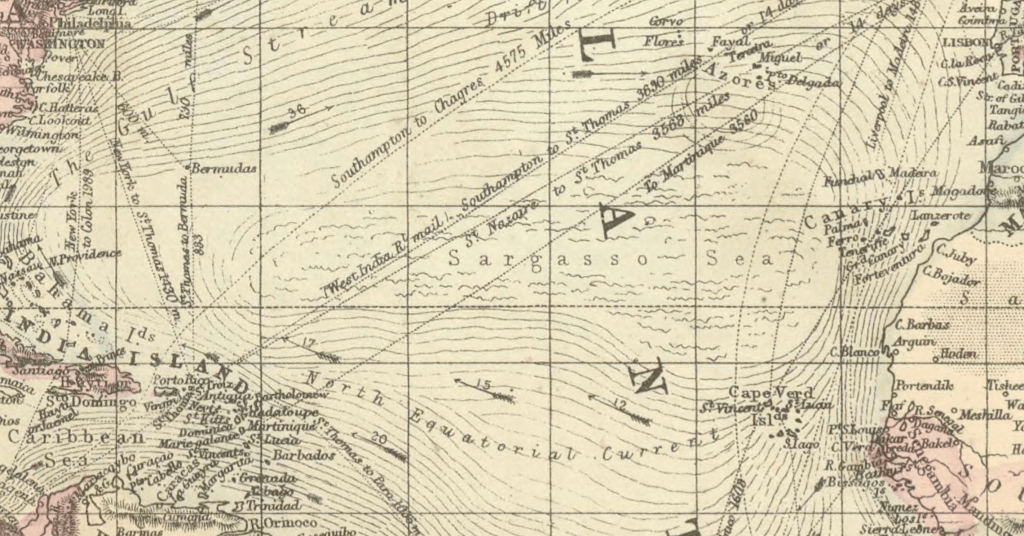

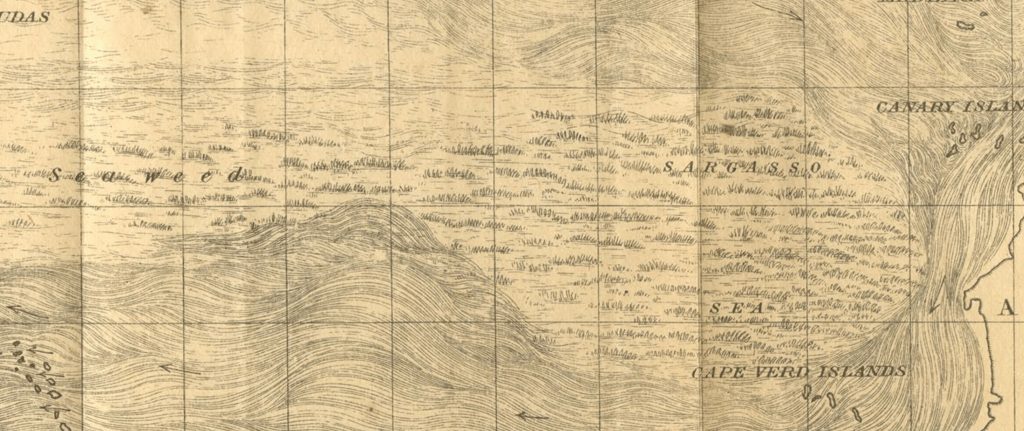

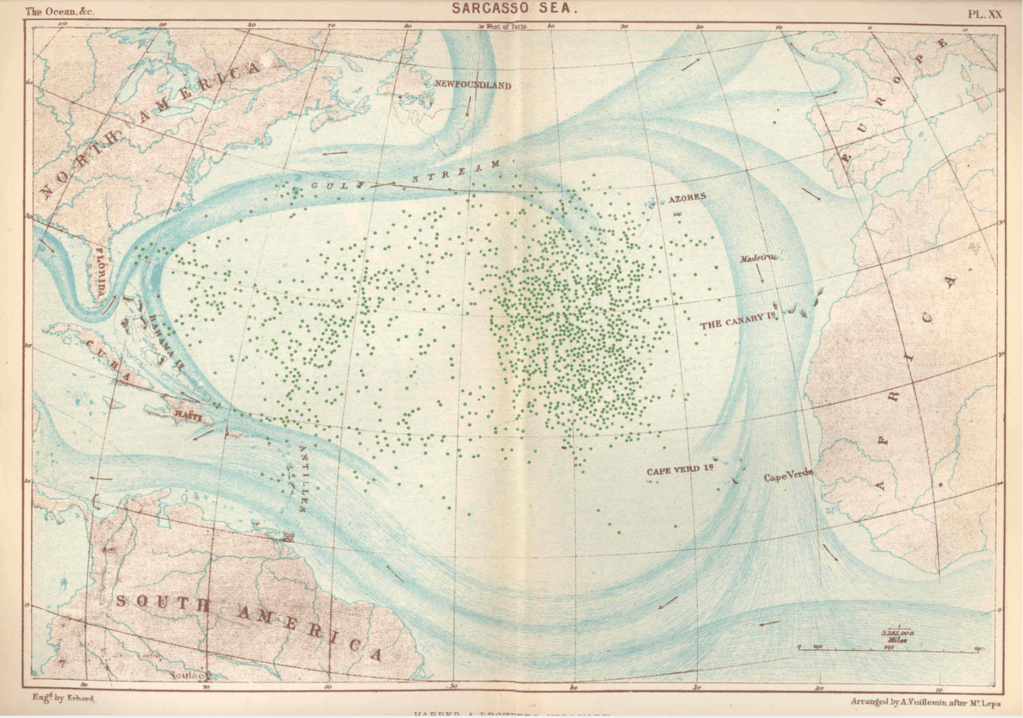

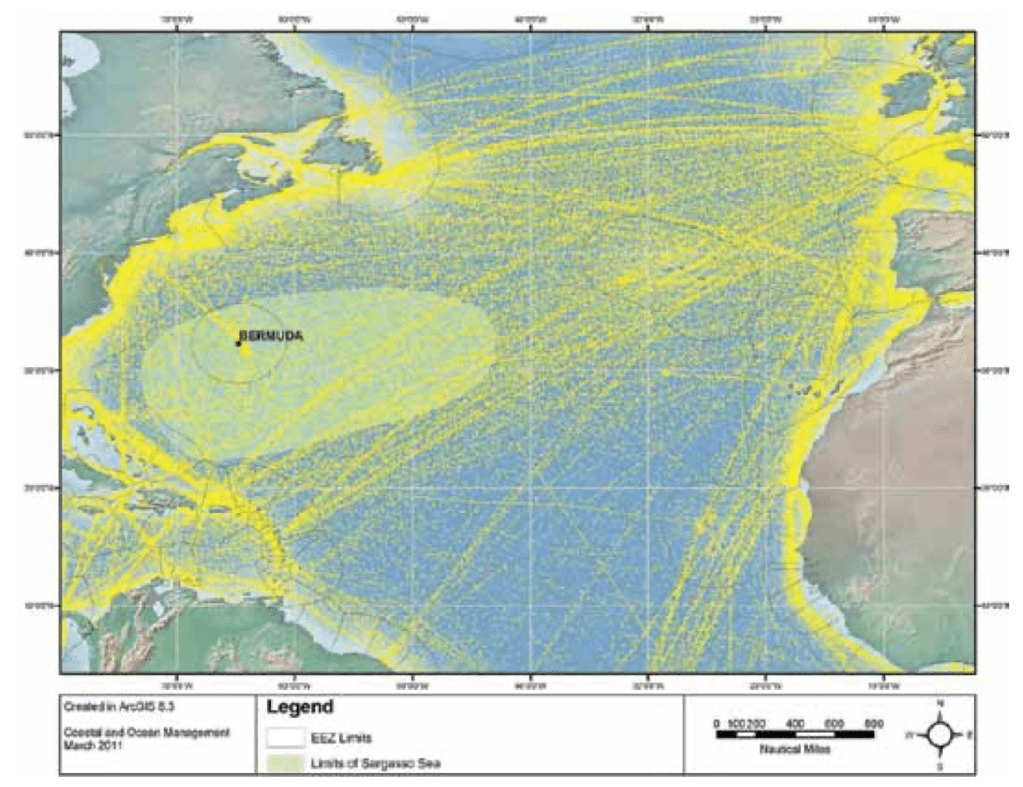

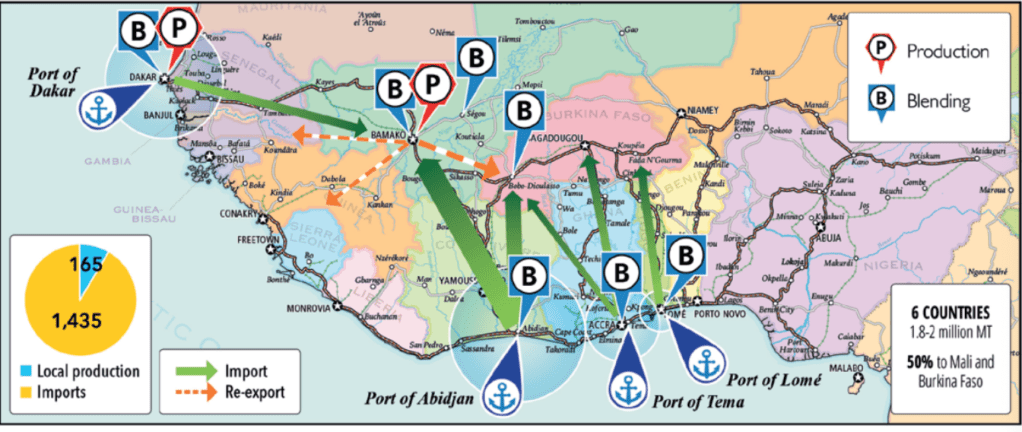

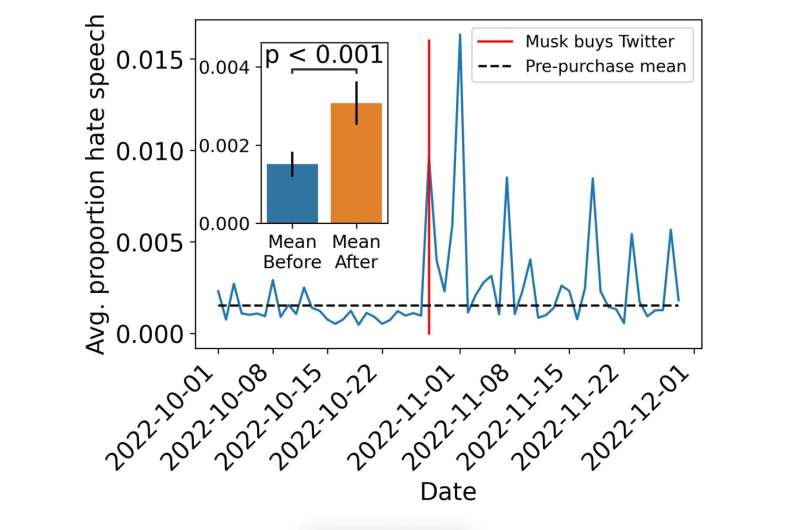

The Apollonian view that was communicated globally became an icon of technological progress and of re-familiarization of the earth. This was so much so was this the cast that the image that was reproduced globally with an unprecedented rapidity–a signe of the new globalization of the news–became adopted as an icon of the ecological movement of the first Earth Day, first observed two years previous in 1970, as if to acknowledge how the photograph taken by Cernan or another of his crew effected a changed relation to global space. In sharp contrast, the planispheric image of the increases in global temperatures is a deep dread, provoking an absence of orientation or storyline: dread is the only word for viewers’ disorientation before maps of rising surface temperatures that reveal the disparity of recent global temperatures from the recent past. Is it any coincidence that the seaborne Sargassum proliferated in the mid-Atlantic in record-setting ambient ocean water?

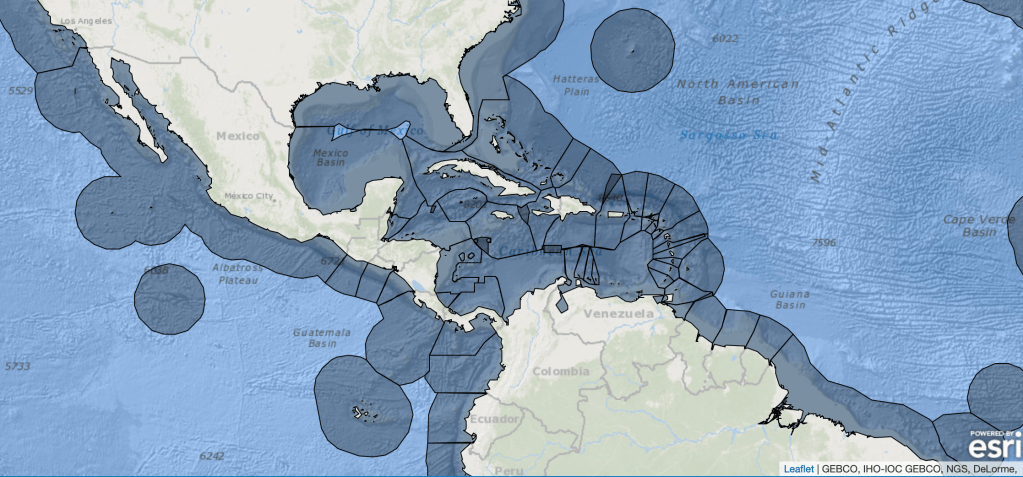

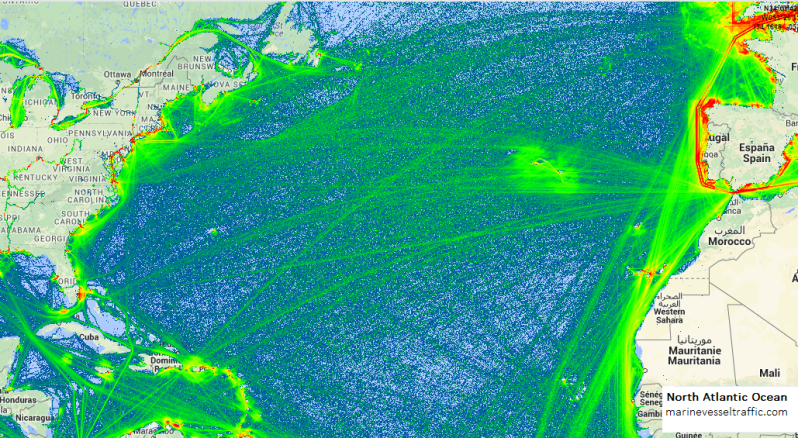

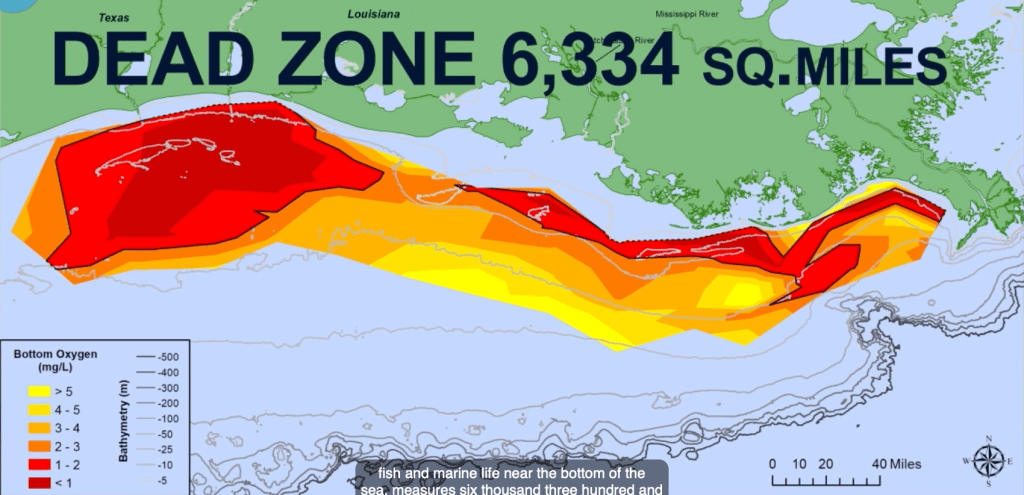

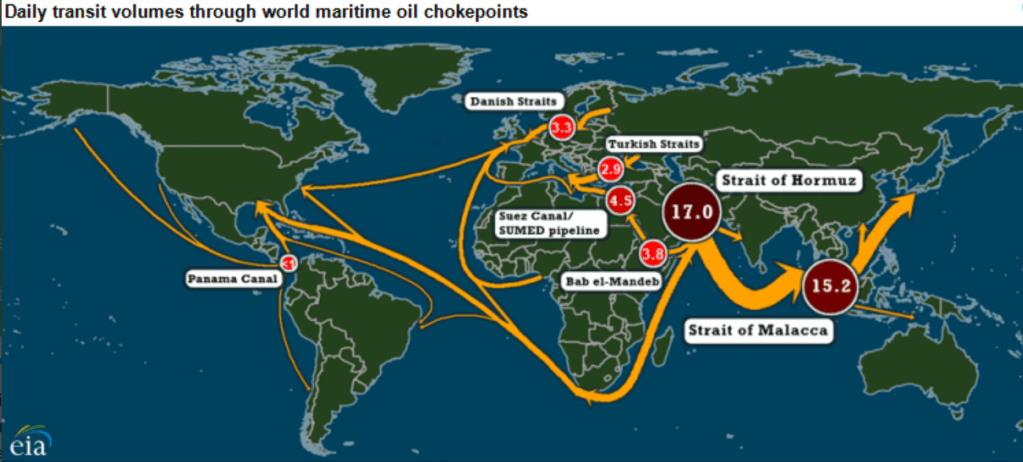

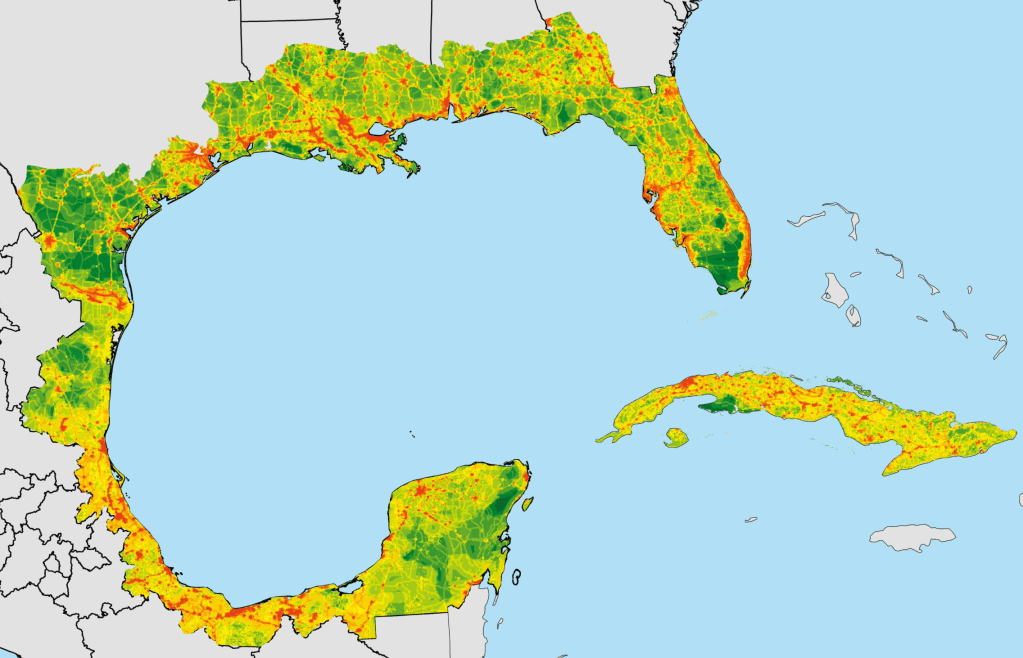

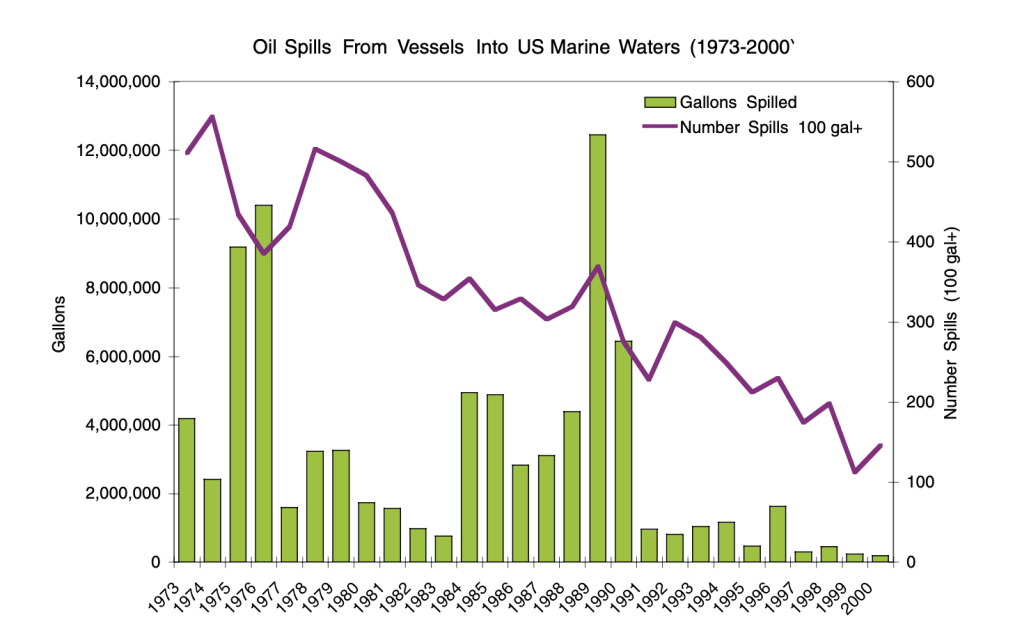

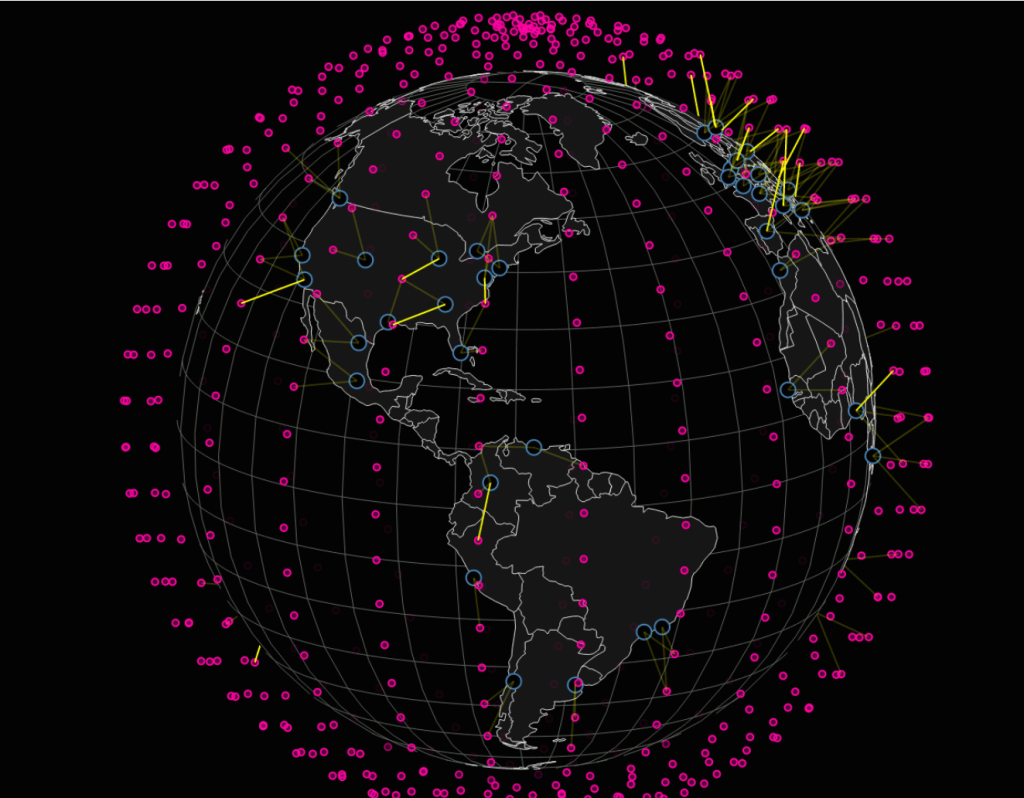

They bode an end not only to seasonality, but the vitality of the global oceans–if not the vitality of the habited world itself. Nowhere is this more apparent than the slick of petroleum that have appeared at the great site of marine diversity and vitality–the Gulf of Mexico–that has become a hub of the offloading of global oil supplies to the Americas for processing, seen as a “chokehold” for daily maritime oil transport of the 56.5 million barrels that traveled on maritime routes–about 63% of world’s total oil production. Indeed, the critical maritime routes for the global transit of oil were long referred to as “chokepoints”–

U.S. Energy Administration, based on 2013 data of Lloyd’s Intelligence, Panama Canal Authority, Suez Canal Authority

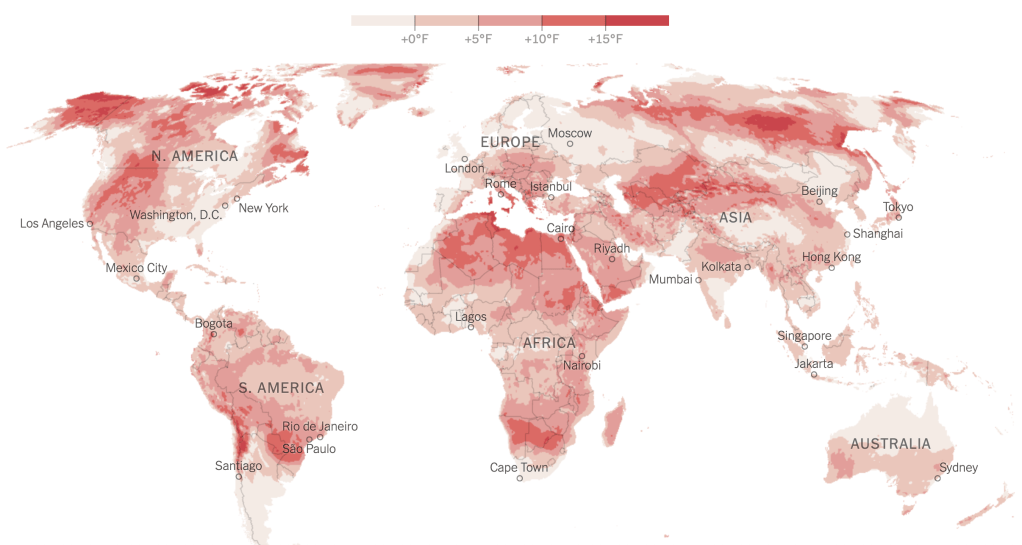

The registering of land temperatures monitored from satellites at a closer distance has created far more terrifying images of defamiliarization this summer and in recent years. The temperatures anomalies is hard to recognize as anything like a map that we might easily recognize, and indeed push the boundaries between cartography and art. If all art may be about estrangement–ostranenie for Russian formalist literary critic Victor Shklovsky and his circle–or “defamiliarization” of the known, the estrangement of global warming temperatures area shocker and an artistic narrative we do not know what to make of save as a learning model for the entrance into the new era of the Anthropocene.

If the politics of estrangement was for Shklovsky rooted in a new sense of life become art, and a revolutionary estrangement of self, global warming seems the utmost in estrangement, although what living through global warming honestly remains hard to come to terms or conceive. It is, for one, outside of our familiar narratives, save the apocalyptic, and we may tend to the apocalyptic as a result. But, this post will suggest, the danger is in a sense deeper than a failure of narrative alone and in ways that we may take a clue from the Russian formalists themselves to understand: for the formal presuppositions of visualizing and of mapping sea temperatures as continuous with land, and as able to be mapped in the same terms as the anomalies of land temperatures, is an ideologic construct and choice, independent of the content of the global maps of raising temperature: for we flatten the sea temperatures at our own risk. Flattening the ocean expanse as if it were akin to land temperatures ignores the extent to which greater heat that drive increasing global temperatures have been storied within the ocean, and the risks of rapidly cascading nature of changes in ocean temperatures that anthropogenic change has produced.

Indeed, the critical ways that mapping sea surface temperatures and mapping ocean resuources as if they were sites for extraction, akin to land-extraction, has led to an increased dependence and sanctioning of offshore waters for extractive drilling, as nations from Canada to Russia to the United States to Argentina to Mexico aim to expropriate underground reserves of oil to boost their national economies and trade, auctioning off lots to the highest bidde, or subsidizing offshore drilling of gas and oil. These huge anthropogenic changee masked or concealed by relying on the relatively surperficial maps of remote satellite sensing of sea surface temperatures alone.

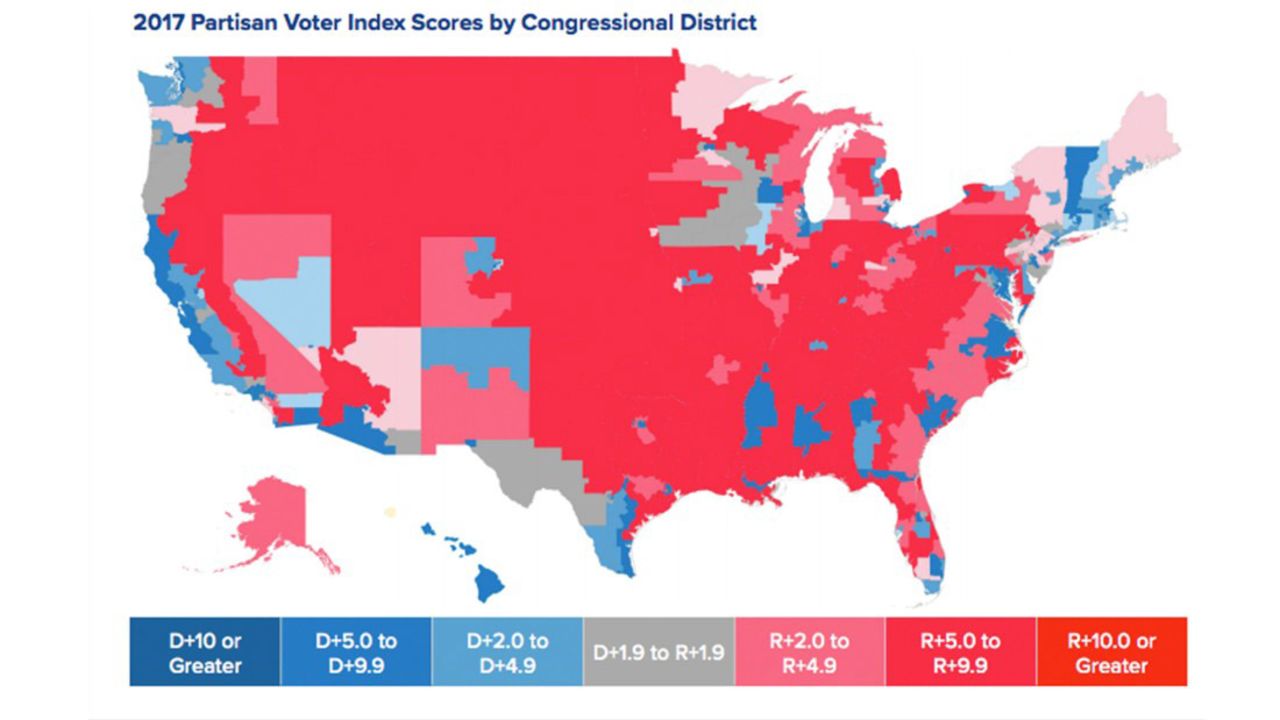

By the middle of June, the GIS anomalies of global temperatures from a baseline of my pre-college years revealed how much personal history had intersected with a radical change in global climate. One’s life memories somewhat incredibly and suddenly in synch with global epochs, reminding me of how very unlike global temperatures for most were compared to the normal in my own memory as well as that of the planet–a daunting prospect and possibility indeed to get one’s mind around. (It’s hard, however, not to wince at the echo of the fractured partisan topography in this map of global temperature change, even if the confine of blue to the arctic regions and western and northeastern United States ; the carmine warming temperatures looming over Canada is quite hard to dissociate from the dry forests that ignited in fires across so much of the nation this summer.)

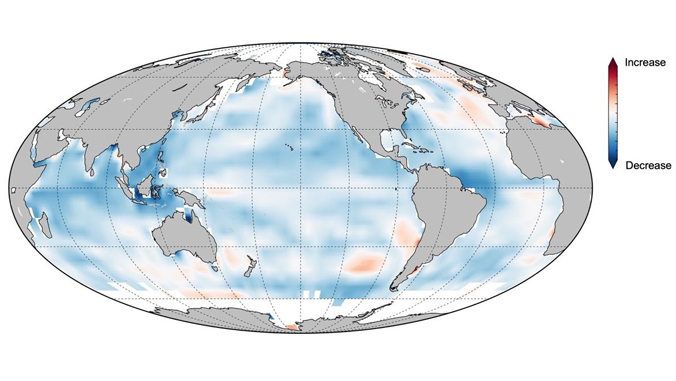

The view from a generation–if not a life perspective–showed a modeled planisphere hard to get one’s mind around, scorched by temperature anomalies, from the ocean off of South America, the arc under the Aleutian Islands, the hot-spot off of west Africa and burn holes of Europe and Siberia. The warming of the global atmosphere was long seen as “one of the most pressing problems of the twenty-first century,” the global maps of heightened atmospheric warming due to elevated carbon levels now a full 50% above preindustrial levels–and larger than ever seen on earth since three to five million years ago–according to paleoclimatic data–make it hard to place the climate changes amplified by greater methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. It is a register of the all too human art to burn carbon, if not just a deeply depressing image leaves one drained of any agency; it is hard to stand before it with anything like the exultant transcendence of fifty years previous.

As carbon levels continue to crest above 420 ppm, we look back at the high levels of CO2 fifty million years ago, average temperatures reached about 10°C warmer than today and the planet ice-free, with sea-levels lapping shores two hundred feet higher above current sea-level. One can segment it many ways, but the huge escalation of temperatures of the oceans–which have stored a vast amount the growing heat we experience on earth, or a whopping 93%–moves unlike how heat is experienced in land, but reflects the most densely populated coasts–and densest sites of anthropogenic waste–

–in the global ocean.

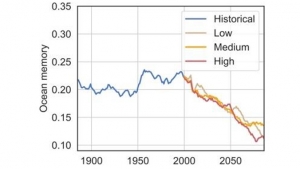

The warming of seas were long recognized just several years ago–in relation to a dataset from the twentieth century and first two decades of the twenty-first–in ways that call attention to just how much atmospheric heat the global ocean has absorbed into its own waters in the past century–and how much more it has additionally absorbed, perhaps putting it over the top as a site able to sustain life, in recent years. If death was the “master fear” that philosophy was able to conquer for stoic philosophers from Seneca to later Romans, able to be overcome to conquer fear itself, the increasingly inhospitable global oceans suggest little to meditate upon we have an ability to process save their own evanescence as habitat for life: the images are perhaps not records of a life lived, but are literally the collective residues of “lives lived” in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. There is no known script of how to live that they offer for virtue or nobility.

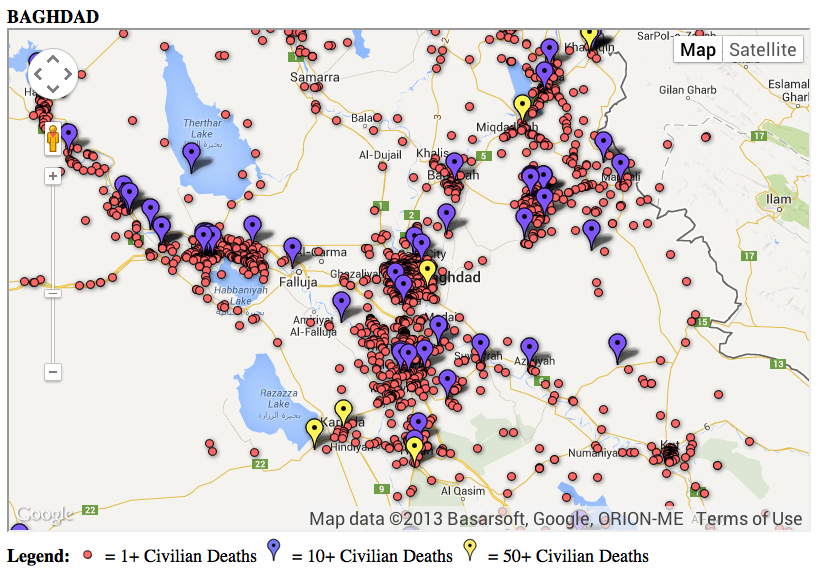

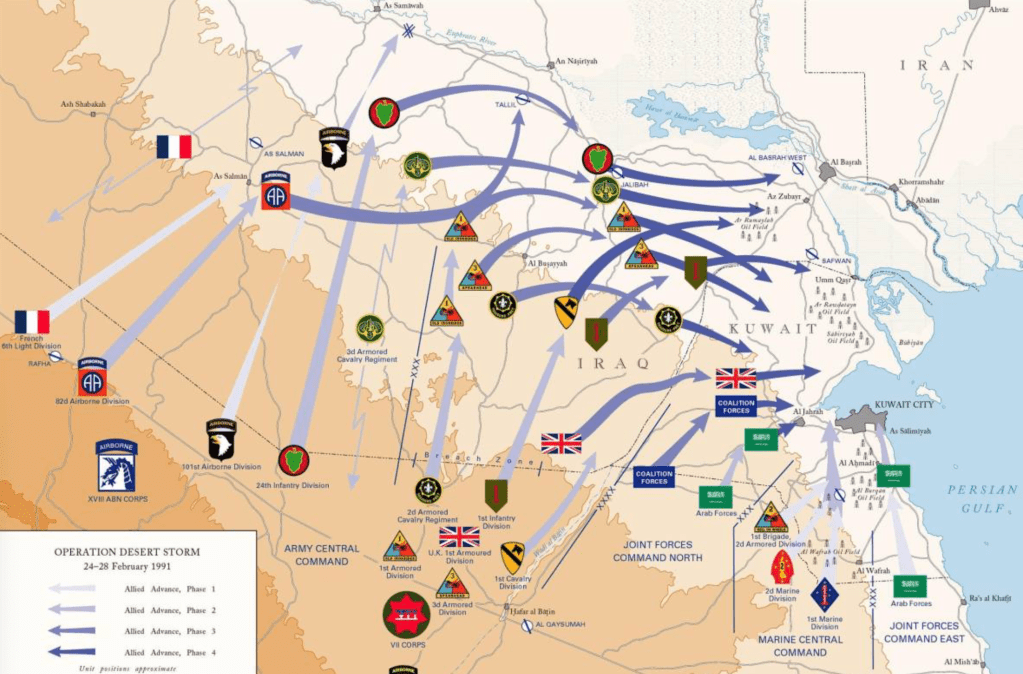

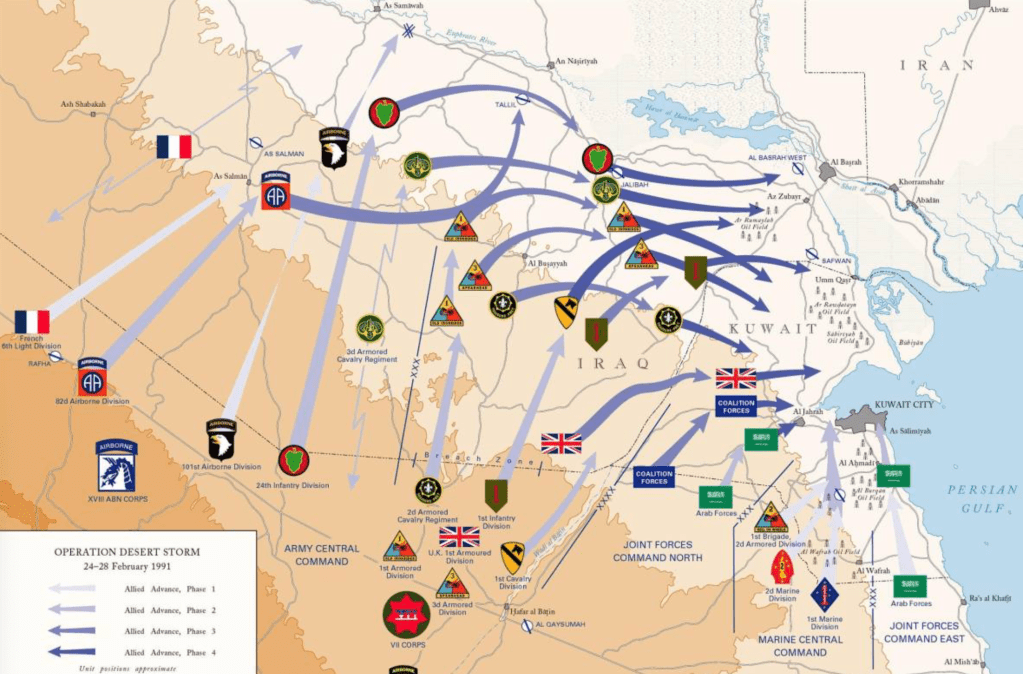

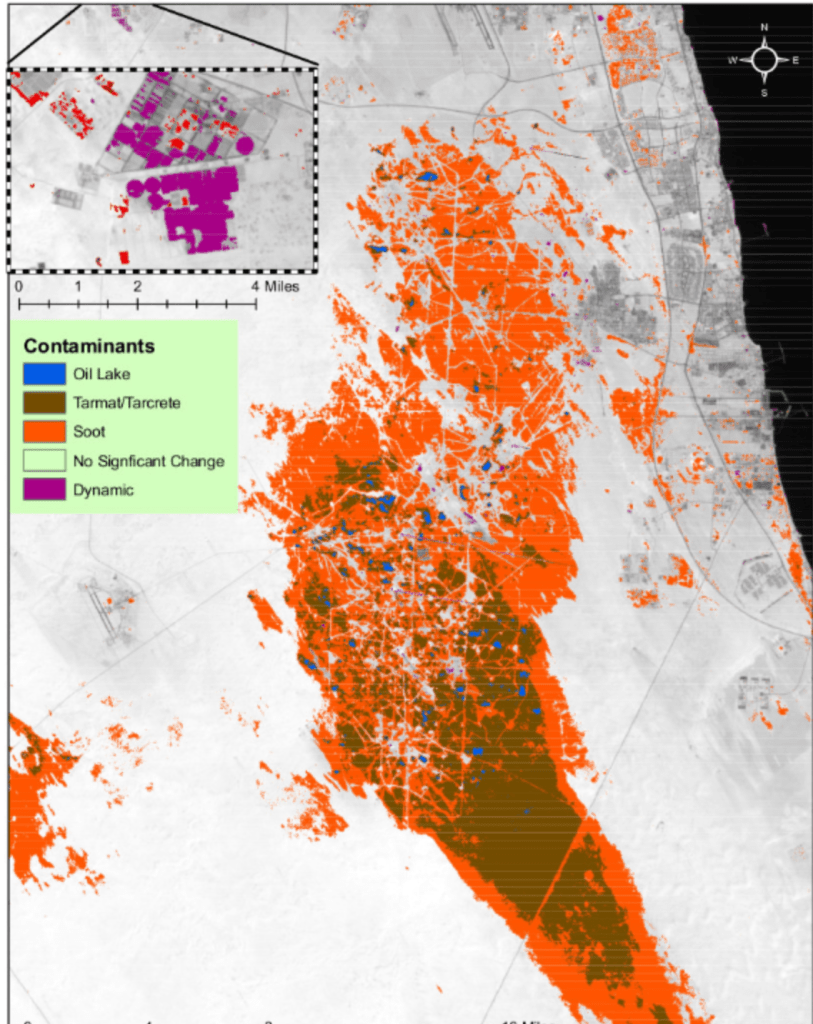

We are increasingly pessimistic about our world view, and the maps of global warming fit with an increasingly pessimistic world view that has been seen as a problem of global purpose, at least from the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 without debate that after eight years of conflict saw “shock and awe” lead to wide questioning if it was worth fighting. If the 3.4 million aircraft sorties that dropped the equivalent of 640 Hiroshima bombs in Cambodia and Laos had cast a shadow over America’s global purpose for one generations, the burning of 700 out of control oil field fires lit by retreating Iraqi forces as they withdrew from Kuwait under fire: as U.S. and allied troops arrived to defend the fields in a war of a hundred hours, of bombing sorties of air-launched cruise missiles, Iraqis lit wells as they retreated to blanket the air rendered unbreathable for soldiers without gas masks in improvised smoke screens of toxic with particulate matter. As “allied” intervention destroyed an amazing 3,000 tanks and 1,400 armed personnel carriers in a matter of days, with countless other vehicles, the plumes of 700 gushing wells were lit, creating up to 300 oil lakes in the desert whose pollution of the soil is as deep as four meters today, now hardened to sludge leaving lakes that are toxic today, even as almost two and a half million cubic meters of sand were cleared. Concservationists remained concerned about continued effects on humans and the environment.

The very commodity over which the war was fought became an aggressive act for the military advantage, squandering petroleum resources the west valued in an age of ecological aggression the transformed the Greater Burgan oil fields into an anthropogenic inferno. Wells were commandeered in a scorched earth policy of unprecedented scale, an environmental disaster that cost over a billion to extinguish, individual wells only able to be extinguished at a rate of one or two a day, as forces were anticipating billions to reconstruct the fields the United States led “allied” forces to defend. The anthropogenic effects may be obscured by of the sovereignty of Empire, far beyond the bounds of the nation state, and the bounds of the Kuwaiti oil fields.

If the logic of direct intervention in the 100 hour war depended on the myth of effective global military apparatus ready to wage a “just” war, asserting military control over Iraqi and Kuwaiti oil fields in the logic of war, the lighting of oil rigs and gas rigs by retreating troop and bombs improvised a network of resistance, blanketing the region with smoke that made aerial surveillance impossible and useless, and offered deep health risks to those troops with “boots on the ground.” As wells burned they ignited the very source of one of the sources of shipments of crude to be refined in the Gulf of Mexico, where much global petroleum is offloaded. The arrival of petroleum in the Gulf’s dispersed system of refineries and multinational companies was a basis for the extension of “American interests” to a region in the Gulf seen as so critical to the globally extended economy to justify the “just war” by American-led forces. The global web of oil refineries across the coastal region was a way in which the wealth of the United States was preserved and transportation economy fed. If oil spills had declined in recent years in U.S. marine waters, the offloading of forign oil in a network of refineries established in American waters in a site of deepewater oil and gas production was a basis for the extension of American “sovereignty” that had ignored the anthropogenic effects of oil toxins was released in the war, if far beyond the US coasts.

If America was stunned that the United States had coordinated the Iraqi invasion of the oilfields in Kuwait, the new source of most oil refined by American oil companies on shore, the war that was fundamentally about blurred borders, and control over the continued flow of extracted petroleum and gas for commodities, the burning oil fields took back the very grounds of production by lighting the oil rigs as torches in the night.

“Kuwait Oil Spill, 1991” by Christopher Gomez (2016)

The anthropogenic scars of the 1991 war with Iraq created warnings of a nuclear winter never to materialize in 1991, burning of hundreds of thousands of barrels released one and a half billion barrels of crude into the environment including “oil lakes” burning for months created but 2% of global emissions. A further hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil from oil field rigs gushed through most of 1991–a record of anthropogenic harm predating Paul Crutzen’s popularization of the concept of a geological epoch distinguishable by its environmental archeology. While the Anthropocene is dated as most evident from the 1950s, as the acceleration of technologies and explosion of atomic bombs left new residues on mountainsides and the planet, the invasion came at the end of the Cold War, at a time when the mobility of troops across the planet had grown in a converse of globalization. The ability to move troops to “invade” or “free” Kuwaiti oil field by aerial bombardment, that mobilized thirty one nation alliance against “military targets” by B-52 strikes and hellfire missiles to prevent Iraq from occupying the oil reserves on which America depended was called a “just war,” but the intervention led to the combustion of eight hundred oil well rigs, three quarters catching fire and burning, and fifty gushing oil onto the ground, until they were capped in October 1991.

The drive to protect oil and gas led to oil fires burning, releasing about 355,000 tons of crude. Their destruction was a retaliation of the sovereign control of speedy troop movements in an intervention that paradigmatically revealed a new sense of Empire asserting sovereign control over Kuwaiti oil fields in a self-defined “just war.” It became a monument of anthropogenic alteration of the landscape by an environmental disaster of new proportions and scale. If the term “boots on the ground” only gained currency in the Invasion of Kuwait, the term that dates in the military from the hostage crisis in Iran suggests the limits and frustration of global mobility, but conceals how the grounds of the region were altered in decisive ways, responding to how the United States showed its readiness to move anywhere in the world with a massive show of force of unprecedented scale, in a new multi-national effort difficult to map or narrate as a story of “boots on the ground,” or to register in the consequences of how multi-national forces intervened in oil fields in Desert Storm.

Operation Desert Storm/U.S. Aarmy

The burning of wells by retreating Iraqi troops left a residue left across the desert sands. Accumulated soot from petroleum refineries and carbon–“tarcrete”–spread as a residue of the war; the dark plumes continued to spew400 metric tons of particulate matter of 2.5μm daily from oil wells with over a hundred million cubic meters of natural gas; sixty to eight million barrels of oil directly entered the Gulf in a major environmental disaster that affected the entire ecosystem, as at least fifty oil wells gushed to the ground and eight hundred were destroyed with explosives, if the total carbon emissions were 2-3% of the global annual anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels and but 0.1% of global CO2 emissions. The local density of soot in the Arabian peninsula lowered climate temperatures by 10 degrees C, and covered extensive areas in Kuwait, Northern Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. Gushing wells flooded the oil fields with lakes of petroleum of up to ten hectares, polluting the Gulf, nearly fifteen thousand million cubic meters of oil leaching in Burgan alone–a site of major air attacks–and 22.5 thousand million in total, much from the armored tanks an munitions were abandoned by soldiers in the desert.

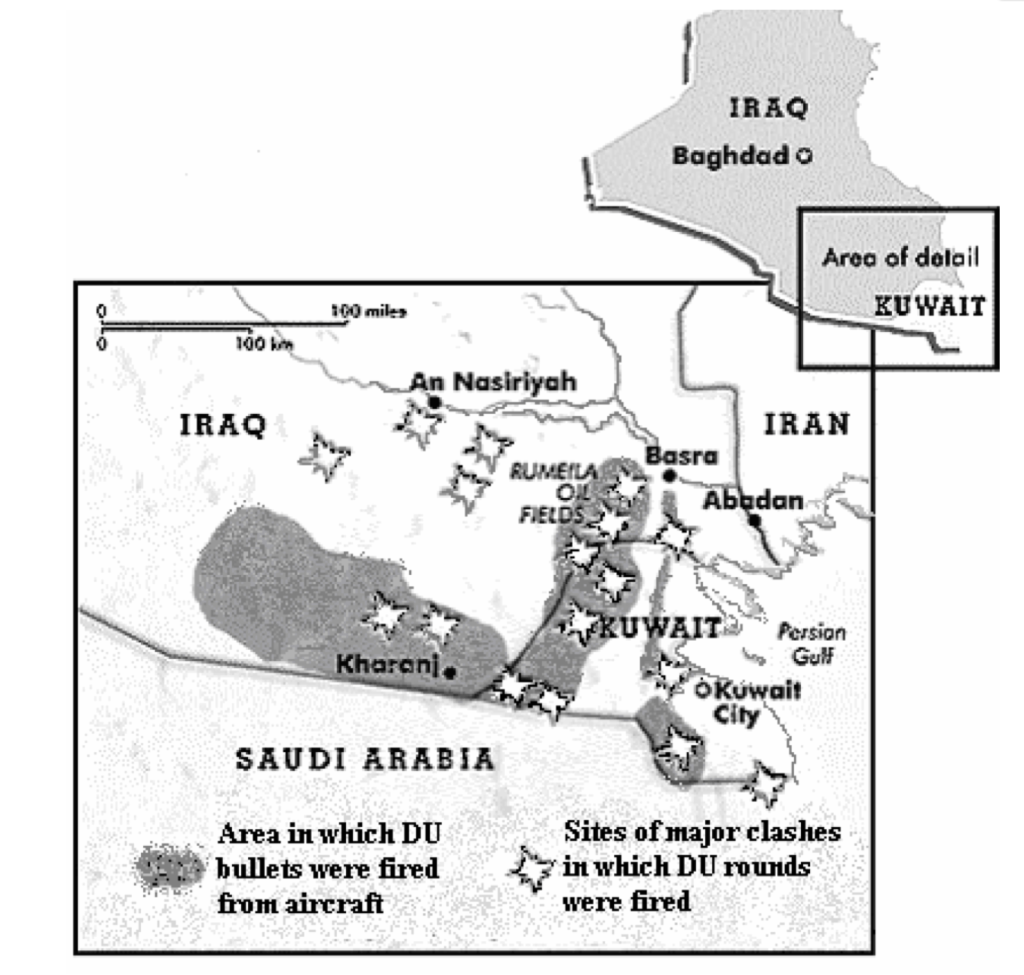

Air Attacks and Major Clashes where Depleted Uranium Rounds Fired into Kuwaiti Oilfields

If the 1991 invasion was a critical starting point in staging a deep environmental estrangement than the rise of the new form of military intervention Negri and Hardt argued epitomized the global interventions for just wars in the new legal formation of Empire. The aggressive American-led military intervention ostensibly to “maintain peace and order” by ensuring the smooth circulation of petroleum extraction from the oil fields of Kuwait and Iraq that were the true targets of western desire. But was the burning of oil wells on the border of Iraq not an active rejection of the claims of this new formation of Empire to the Kuwaiti oil fields? Before a feared economic disintegration of multinational claims, the military intervention and conquest sought to construct a global order superseding time to replace it with “free markets,” Negri and Hardt argued, beginning from the military interventions that precipitated the Gulf War.

In response, Iraqi troops set rigs on fire by wresting control of the very underground deposits of petroleum defined as the economic resources of the region, using the infrastructure of energy companies to upend the peaceful new neoliberal order so blithely unilaterally proclaimed. The consumption by combustion of the gushing rigs that were an infrastructure of global energy networks were appropriated as the sites of resistance against the western “peace-keeping” forces that arrived from the air. Who is to say it was not staging resistance on the ground, from the ground up? The redirected anthropogenic effects of a massive project of extraction as Iraqi troops unexpectedly released improvised smoke-cover undermined the organization of a planned international military intervention of a “just war” monitored from above by satellites as a massive disproportionate show of force and deployment of troops by obscuring it from satellite monitoring from a new theater of war. If the war depended on an effective image and logic of military control over Iraqi airspace, the seven hundred oil rigs that burned as a monument to the Anthropocene offered an improvised network of resistance, blanketing the region with smoke that made air surveillance impossible, subverting mapping military progress by satellite from the ground and subverting the smooth exercise of power over the space of what was define as a Just war against Iraq.

When Oil Fields Burned (1991), Sebastião Salgado/Amazonas

If the months leading up to the invasion of Iraqi-held Kuwait met the criteria of Christian “just war” doctrine formulated by St. Augustine, and refined by the scholastic theologian Thomas of Aquinas, the claims of legitimacy of an invasion to secure peace in the region was closely tied to apocalyptic outcomes: as retreating Iraqi forces lit the abandoned oil fields, even if the feared “Nuclear Winter” or year without summer did not materialize, the dense plumes of smoke spreading hundreds of kilometers from multiple points in oil fields set a new standard of fear in haunting images of burning oilfields streaming black smoke, as periodic oil fires have since haunted the region. The model of imperial authority was maudlin if not blatantly absurd. Could the pastoralism of Kuwaiti shepherd corralling sheep and goats–most of whom are in fact migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh or other Indian states–be more mismatched than against the apocalyptic billowing black clouds that drove streams of particulate matter across the skies?

Was the fear not an attempt to come to terms with the unprecedented global scale of such then-devastating environmental aftermaths? The oil plumes streaming hundreds of kilometers across the horion have provided a topos to which later wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have returned, an image of the iconic burning of oil once stored underground, in reserves–releasing more than twice as many barrels of oil into the Persian Gulf as the Deepwater Horizon would release in the Gulf of Mexico, and spreading eight times as many across the desert.

The jarring image of the burning blazes of the swells in a region defined by its pastoral economy suggested the deeply dissonant historical circularity of the claims to Empire that were at stake across borders, as troops on the ground were sent to defend multinationals’ interests–if with democratic pieties–the first great neoliberal war defined by alleged defense of Kuwaiti sovereignty by a “line in the sand” was the first war of Empire, for Negri and Hardt, in a boundless, universal space: the plumes spreading to international air space–as well as a hazard for those breathing on the ground:

Plumes from Kuwaiti Oil Wells Burning around Kuwait City in April 7, 1991 from Space Shuttle Atlantis/ NASA’s Earth Observatory

The streams of black particulate matter that was so toxic to the lungs of those with “boots on the ground” defending oil fields in Kuwait were grasped in global terms, less in terms of Empire than another global climactic events–if this time released by man, blaming the Iraqi troops for loosing the fires in response to massively disproportionate air fire launched against them for a famously brief hundred hour war entitled “Operation Desert Storm,” a multinational military seizing of oil fields cast as a “just war” but revealing increased global energy dependence on extracted crude.

The black smoke issuing from burning rigs were feared to englobe the world in a “little ice age” akin to the black ash clouds that were emitted into the global atmosphere at the 1883 volcanic explosion of Krakatoa, or four volcanic eruptions that had earlier led to the expansion of the Arctic Sea circa 1275-1300, leading to the expansion of glacial valleys in Europe from the Alps to Norway, in a similarly global cataclysm of man-made origin, and came to be paradigmatic of the definition of barbarism versus civilization, or the economic status quo, or democracy versus totalitarianism. Burning of oil fields, many not fully exhausted or capped until November, 1991, spewed or released petroleum into the desert and river or Gulf for up to eight months, creating new “oil seas” of toxic character, set a stage for the burning of gushing and roaring in future wars in northern Iraq that have colored the desert landscape with a dark anthropogenic pall of thick, dark smoke, repurposing a geography of oil fields as geopolitical tools of, normalizing the burning of 4.6 million barrels/day by 2016-17 whose blanket of fine carbon dust blocked solar rays to cool local temperatures.

The pessimism of purpose in the world extends to the and infects the warming of our global temperatures, as if to condemn us to a history of carbon extraction of which the Gulf War was the iconic turning point. Temperature rise is easily seen as part of a pessimistic world picture we cannot intervene, as if evidence of inevitable products of life of a carbon-burning age, the rise of temperatures. the age was spurred by the billions made from the postwar extraction of carbon-rich fuels have been the stimulus of an overheating planet, bringing temperatures of oceans and land alike–albeit in importantly different ways–to a tipping point, starting from that harrowing moment of apparent apocalyptic images of burning oil wells in 1991, the spewing of tarcrete seemed to confirm the arrival of an age of the Anthropocene before the word emerged in the critical literature–an age defined by the spread of economies of extraction as the dominant means of moving far beyond sovereign bounds.

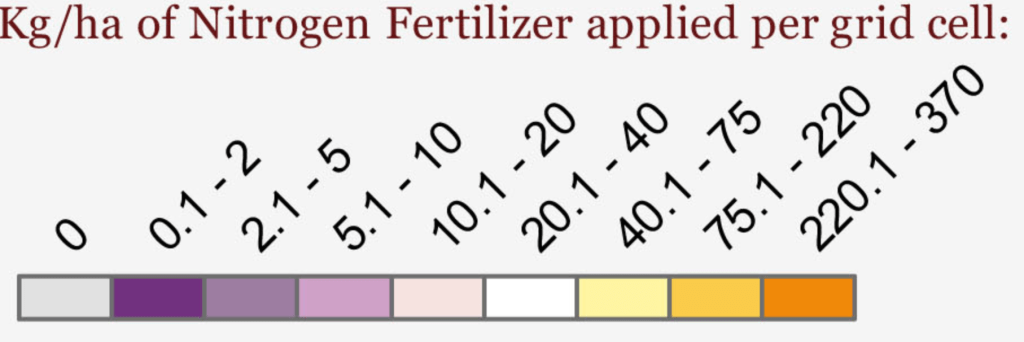

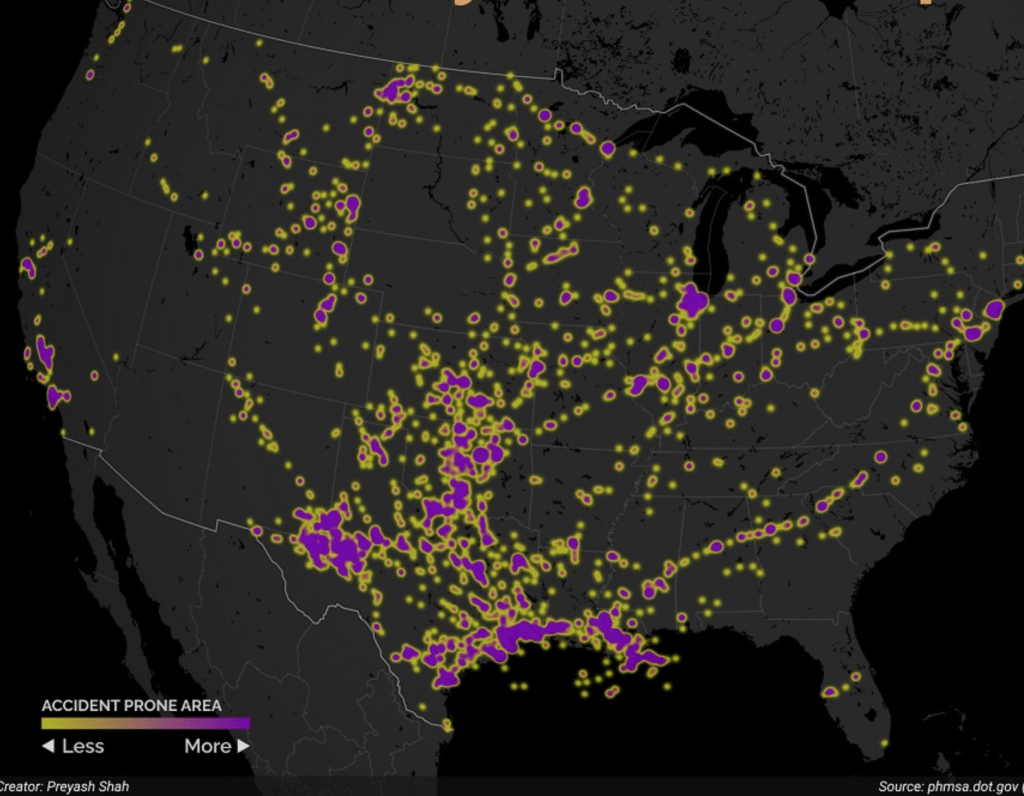

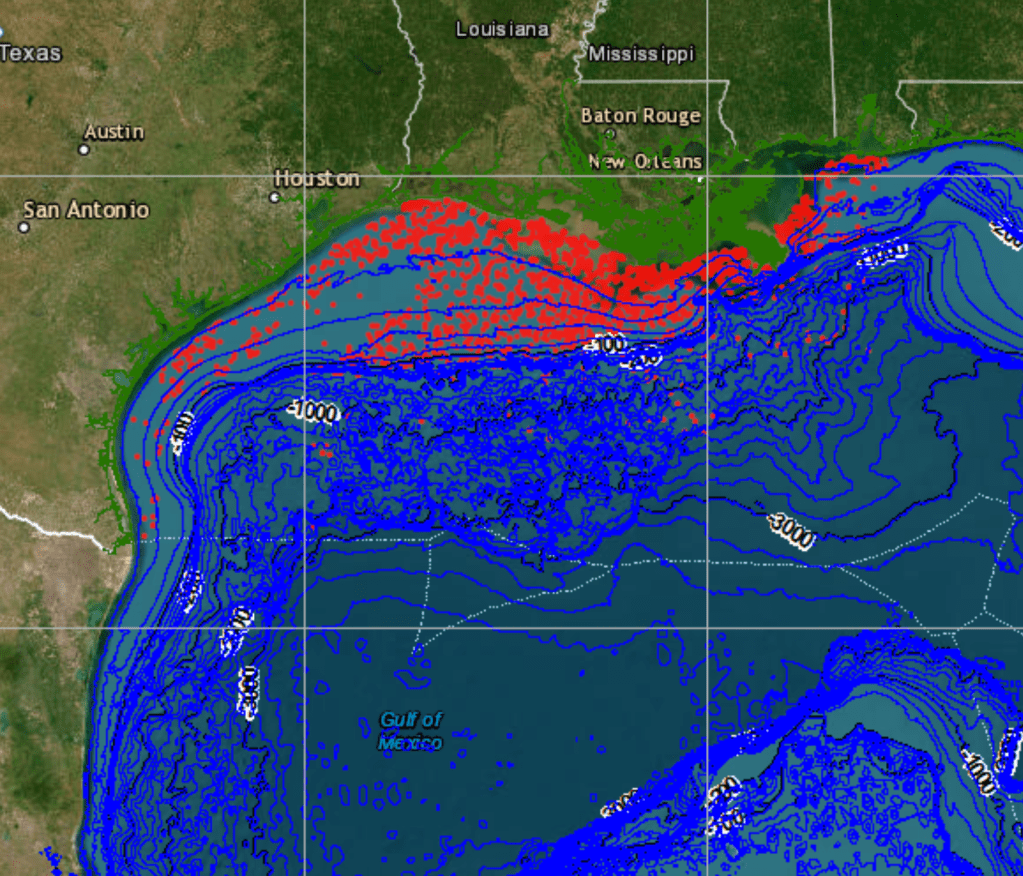

The increasing quantities of “accidental” spills that have been occurring in the United States since 2010 alone have led to a blossoming of pipeline leaks, shipping accidents, train derailments and industrial disasters that have revealed the downside of the extractive industries the government overabundantly subsidizes and funds: over half the spills were of crude oil, and a further third petroleum products, and a sixth highly flammable gas. The small number of leaks of ammonia and other highly volatile liquids made from petroleum should not detract from their high levels of their toxicity: the greatest number of accidents of costly crude spills whose clean-up can continue for years range from petroleum products such as diesel or gasoline, to liquefied natural gas or crude, have an unsurprising epicenter around the Gulf of Mexico, per Visual Capitalist‘s Preyash Shah, and can include the very liquified CO2 products under high pressure regularly transported in pipelines, commonly used for carbon capture storage. If almost have of such spills have been mapped in Texas (site of 40% of the almost 5,000 spills that were mapped in the twelve years 2010-2022, the leaking of crude and natural gas plumes across the density of offshore platforms along the Louisiana Coast is downright terrifying.

U.S. Oil and Gas Spills, 2010-20122/Visual Capitalist, 2022

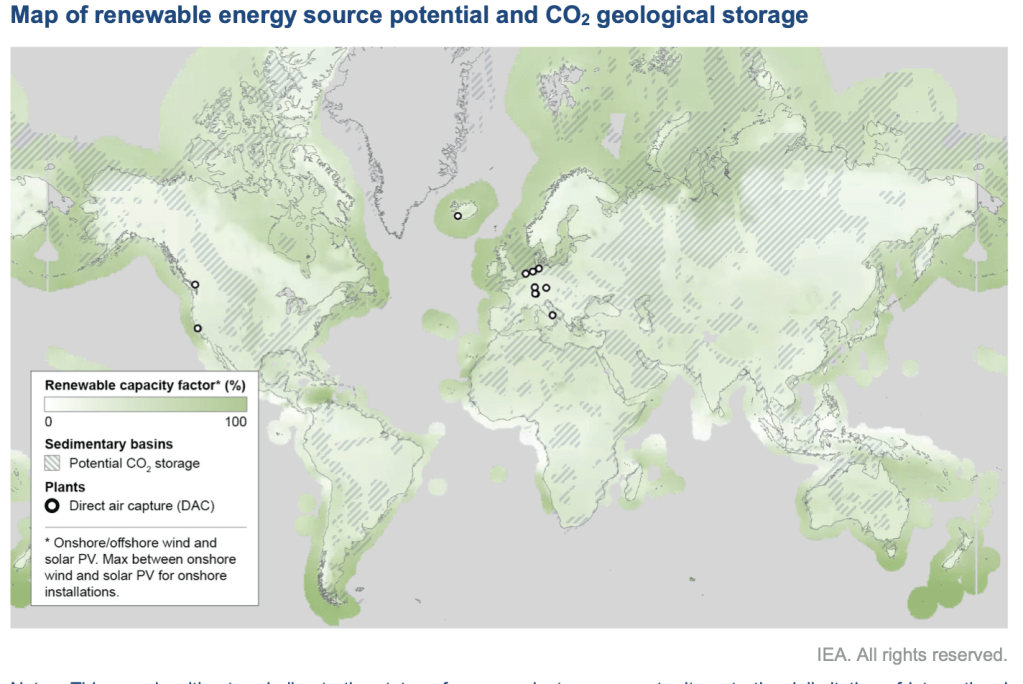

It is all too problematic that the very same companies benefitting form gas and oil extraction are now at work–from Occidental Petroleum to Exxon Mobil to Chevron to Shell–on the unproven Direct Air Capture technologies, misleadingly billed as a means to achieve emissions reduction goals set in the recent Paris Climate Accords and as the corporate ticket to “carbon neutrality.” This is the new gospel of a soft neoliberalism in which the government would outsource aging infrastructure of energy extraction to capture carbon from the air at the very site of its release by energy corporations. If a “soft neo-liberalism” at the edges of the nation state, the expansion of public-private partnerships that extend offshore into Gulf of Mexico, beyond the edges of the nation, are haunted by the terrifying LandSat images of a landscape of hundreds of oil fields burning out of control.

For in reaction to the 1991 arrival of American-led “boots on the ground” forces in Kuwait, who waged all-night battles on the Euphrates, Iraqi troops repurposed the underground reserves of subterranean oil fields to super-abundant Molotov cocktails thrown into the atmosphere far beyond sovereign bounds. The striking televised footage of the global dispersion of carbon ash, that almost replaced teh expectant footage of a ready and easy victory, anticipated the billowing towers of the foormer World Trade Center, belching black smoke from the combusting contents of the tankers of airlines that later flew into the twin towers. If the towers billowing black smoke in lower Manhattan was an icon of the War on Terror and of the Gulf War, the unstoppable release of those hundreds of oil fields senselessly burning oil, as if to reappropriate the crude bound for western tankers in the Gulf, and energy markets abroad, the staking of oil sovereignty in the Atlantic seems to bring the reserves extracted far, far closer to home. T he unpromising and unproven promise of carbon removal by Direct Air Capture seems to rewrite the wounds of Middle Eastern wars of oil sovereignty closer offshore, mapping a new image of petrosovereignty in an age of Empire. Carbon removal is promoted as a way of justifying petroleum and gas extraction in an era of extreme climate change–and climate activists urged to support carbon removal by Direct Air Capture even as oil companies have treat it as grounds to continue drilling, producing and using fossil fuels.

We are argued to have no other option, but our backs are up against the wall if we hope to stay the rising of ocean temperatures. There may be virtue in recycling, but the density of this color spectrum, tending from red to carmine, only illuminate a massive shift on a scale we have no clear ability to presume a personal relation to–or perhaps even the cognitive ability to grasp fully. We stand before these maps haunted by a deep dread, a fear that is perhaps debilitating more than empowered, but perhaps diminished by what has preceded, and with no sense of rational decision–although we are tempted to arrive at many a quick fix to steer back from the apocalypse of warming oceans. Can the deep reds be anything other than a warning of warming to come, a continuation of the global trends of dramatically increased ocean warming and sea surface heat.

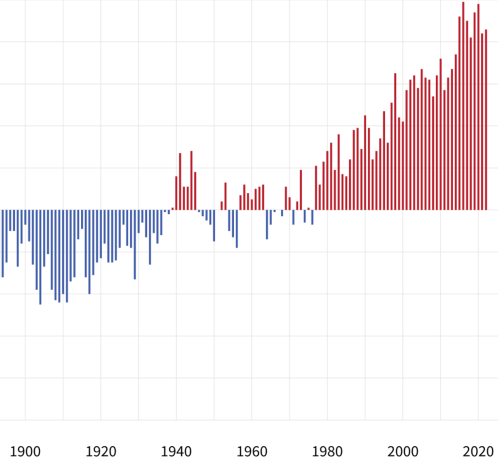

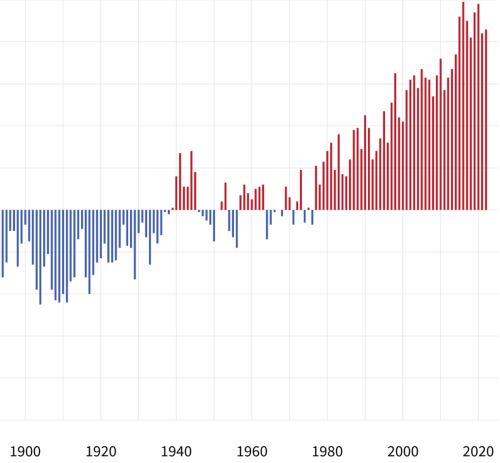

Trends in Global Sea Temperatures in Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries (1901-2020)/EPA

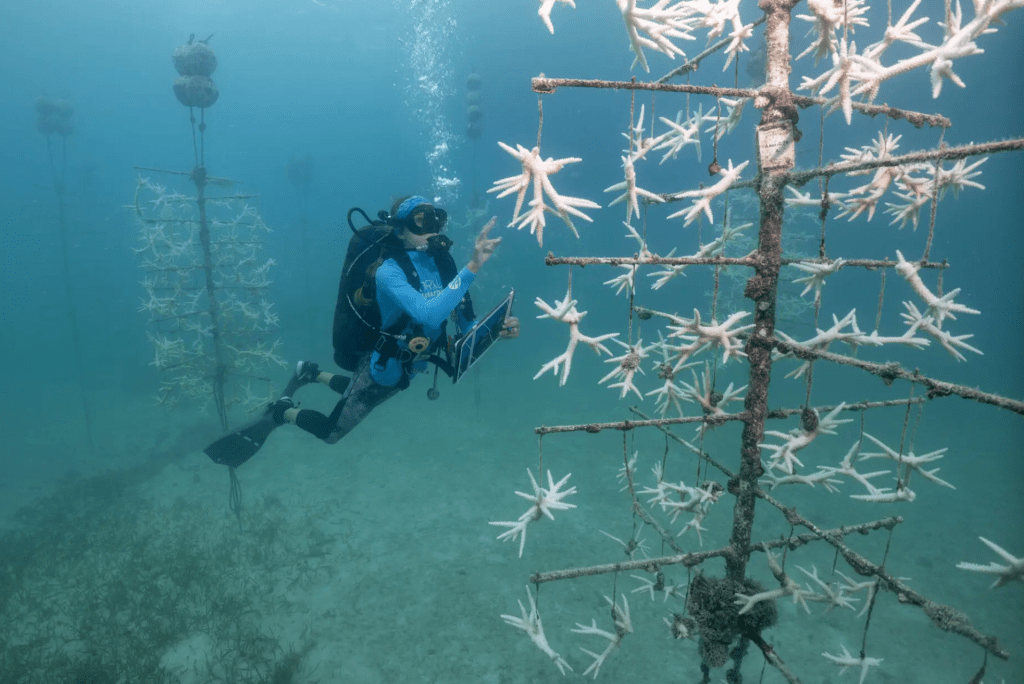

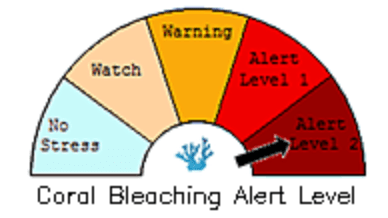

The rasterization of the global ellipsoid suggests a dangerous distance from the mechanics of warming, even if it maps the globe on a jarring color ramp we have not seen before, or are likely to be able to interpret. The very etheriality of these raster maps of temperature anomalies are striking as they cast the ocean on a distinctly red color ramp. As if in synchony with the massive waves of coral bleaching in global oceans–whose impact and scale we cannot yet calculate–we find things of the impending nature of ecosystemic colapse that fills with palpable dread, but is more striking in its absence of any fitting narrative. If the story is tragic, and existential in scope, the cognitively disarming nature of these pixellated maps are as strikningly removed from any material basis, and lacks any clear distance to comprehend as it is bereft of any narrative.

It seems the lack of clear narrative, and the alarm of red, leads to such perhaps well-intentioned but tragically desperate cries for help as Just Stop Oil protestors calling for the immediate end of fossil fuels by using orange florescent spray paint to target the neoclassical Radcliffe Camera icon of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, spraying a fluorescent orange on a structure built 1737-1749 to embody Enlightenment ideals. The Palladian domed building might typify the Enlightenment, targeted as if the root of deep ignorance of the consequences of extraction, but also illustrates an inability to imagine any end-game save cessation of use of extractive fuels across the entire global economy. The rugged demand–Just Stop Oil!–suggests a purblind view of the interests at play–is it only government or any government, or isn’t the problem a little more manifold? can orange spraypaint to deface a heritage structure really make a mark, or is it just a muffled cry for help?

Hugh Warwick/October 10, 2023

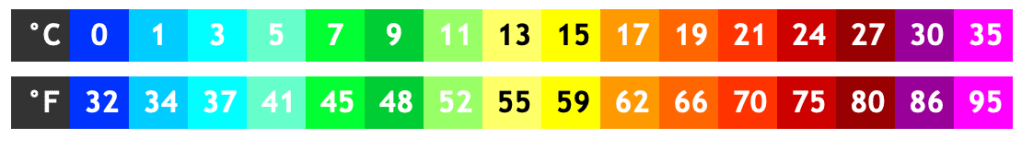

Welcome to truly desperate times. The intense orange removed by power0hoses hours after a disgruntled Oxford student and his mate seem to have repurposed the immediacy of Nike’s corporate slogan suggest nothing less than an existential sense of the teetering image of the world’s environment that could not but echo the insisted on recent temperature trends that have lasted the lives of the ecological activists, twenty-one and eighteen year respectively, taking a stand against the markedly uncontrolled increased warming of land areas and wildly shifting extremes of seasonal temperature that had led to the expansive melting of arctic regions. Following the alarming colors of temperatures changes NOAA features on the Climate Dashboard, the spread of rising temperatures by over half a degree Fahrenheit/decade are truly causes for alarm.

Climate Dashboard: Changes in Climate Temperature by Decade , 1993-2022

But the deep orange hues of the slogan of the Just Stop Oil folks earnestly demanding “no new oil, no new gas or coal” are calling for a “deliberate disobedience” that the spray-painting of Radcliffe Hall–a symbol of Oxford–inaugurates across three weeks of action from October 29, akin to a reckoning, designed to appeal to students, promises a greater sense of agency and empowerment in a world where “No-one’s going to save us, we have to come together to do that for ourselves” in time for Halloween, as if to grab the steering wheel on a car that has been driving out of control, and force the hand of civil government by collective actions of “deliberate disobedience”– assuming equivalent existential urgency of the dispossessed: “what will the Government do? Concede to our demand, or crack down and arrest us all?” The Oxford protests, on the heels of the spraying of Bristol’s Queens building with the same bright orange paint, urging all faculty and students to join in the “civil resistance,” led to the Oxford student to claim to be “taking action to resist the destruction of my generation,” noting the scale of the climate crisis of which “Oxford academics are fully aware of,” but despite knowledge of fast-approaching “unsurvivable heat and humidity” that will force “hundreds of millions of people will be forced to move, or die” is tantamount to genocide.

Before “the annihilation of everything we care about,” the Oxford student who defaced a site of study by florescent orange paint seemed to interrupt quiescent study. On the heels of the spraying of a building in Bristol’s Queens building with analogously orange industrial paint, asking all university students and faculty to unite in a “civil resistance” to extractive energy, the Oxford undergraduate felt he was “taking action to resist the destruction of my generation” in existential terms, decrying how “Oxford academics are fully aware of the scale of the climate crisis” but ignore it. As a member of Just Stop Oil, a coalition committed to forcing the government to end “all new licences and consents for the exploration, development and production of fossil fuels in the UK,” he was confined of the need to stop a narrative of planetary warming that has an inevitably tragic end.

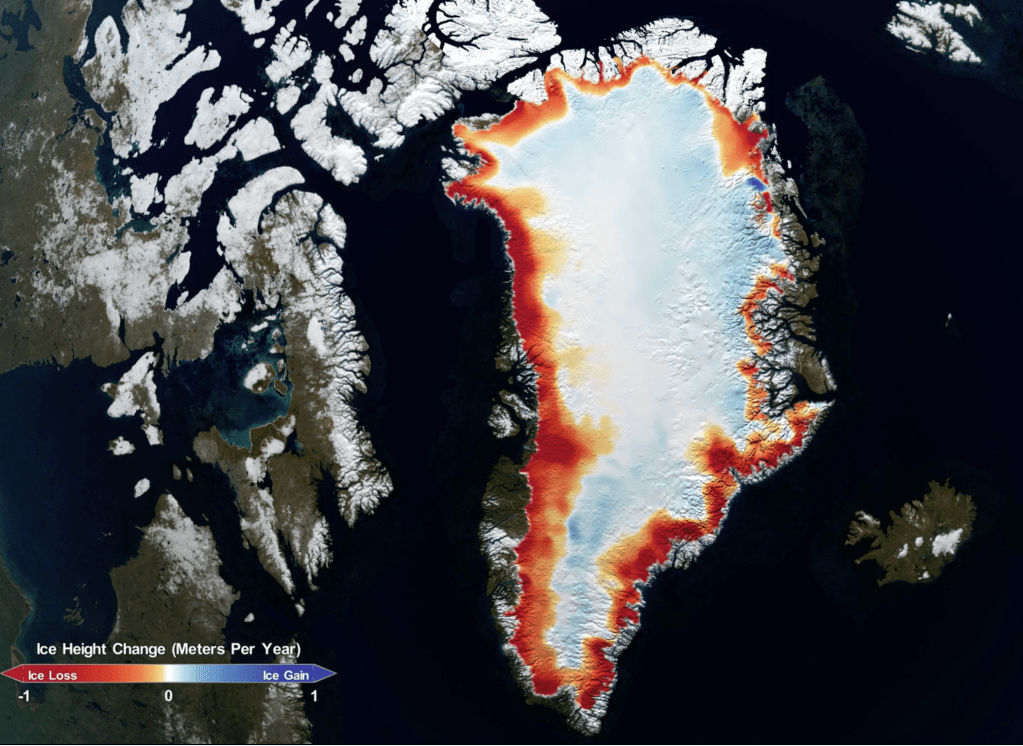

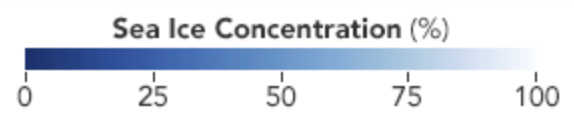

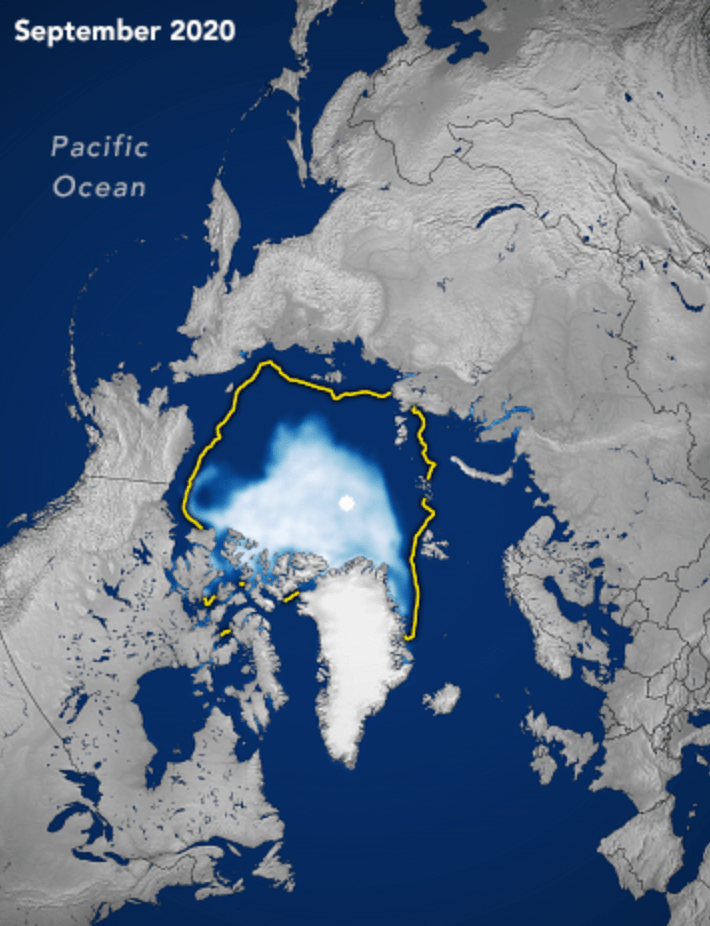

Have we failed this generation, and indeed failed the cause of climate change, by maps that assume an impending disaster of warming that offer no possibility of change or berth of safety or remove? This seems a Eurocene, to be sure, as much as an Anthropocene, of unconscionable harm to habitat range, environment, and ecosystems as a massive amount of energy has been insistently raising global temperatures by extra unwanted heat. The recent rasterization of our ocean maps–we map less bathymetry than temperature anomalies in the daily coral reef watch–recast the ocean as haunted by color ramps we have never seen before, pressing us to create stories and gain a grasp on what has been happening with the oceans as they warm in dangerous directions across the north.

The liability of such raster maps may lie in their eery ethereality: a pixellated space distances us from the materiality of climate change. For rasterization problematically offers an eerily immaterial way to view global warming unhelpful in its terrifying immateriality, as if blocks of predestined pigment sprayed across the ellipsoid outlines globe at a distance and from on high mark the bleaching of ocean life. It is terrifyingly inappropriate not only in its lack of narrative–if the story is tragic, and it is existential to boot–but cognitively disarming as it is removed from any precedent, wrapping the surface of a globe as if spray-painted across the flat ellipsoid disk we struggle to map to particular losses, filled with forebodings of increaed global warmth.

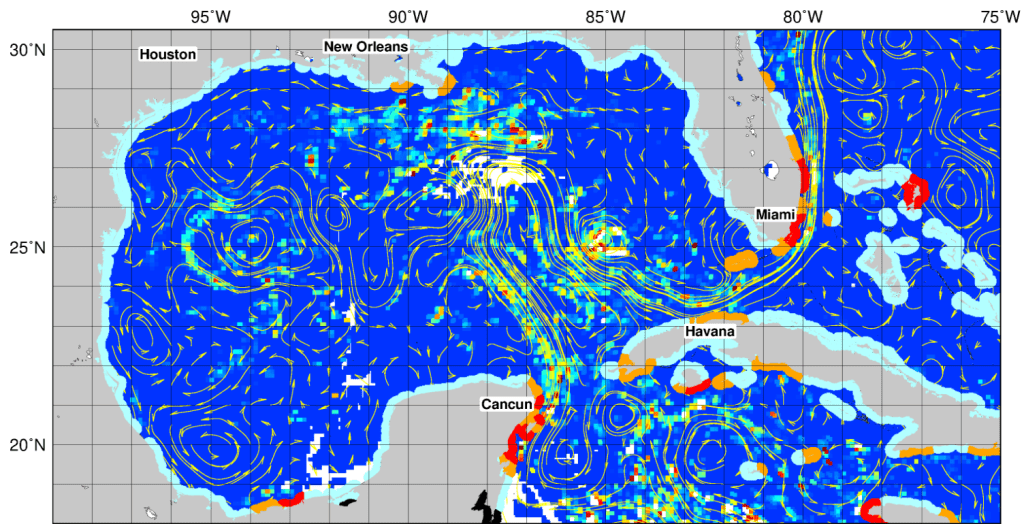

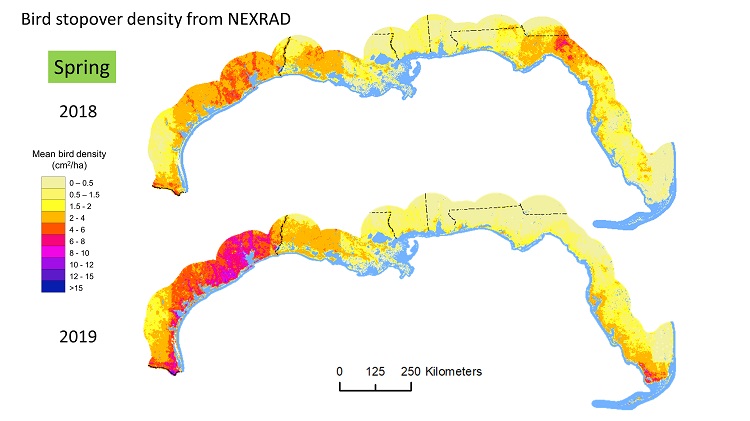

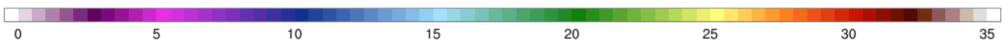

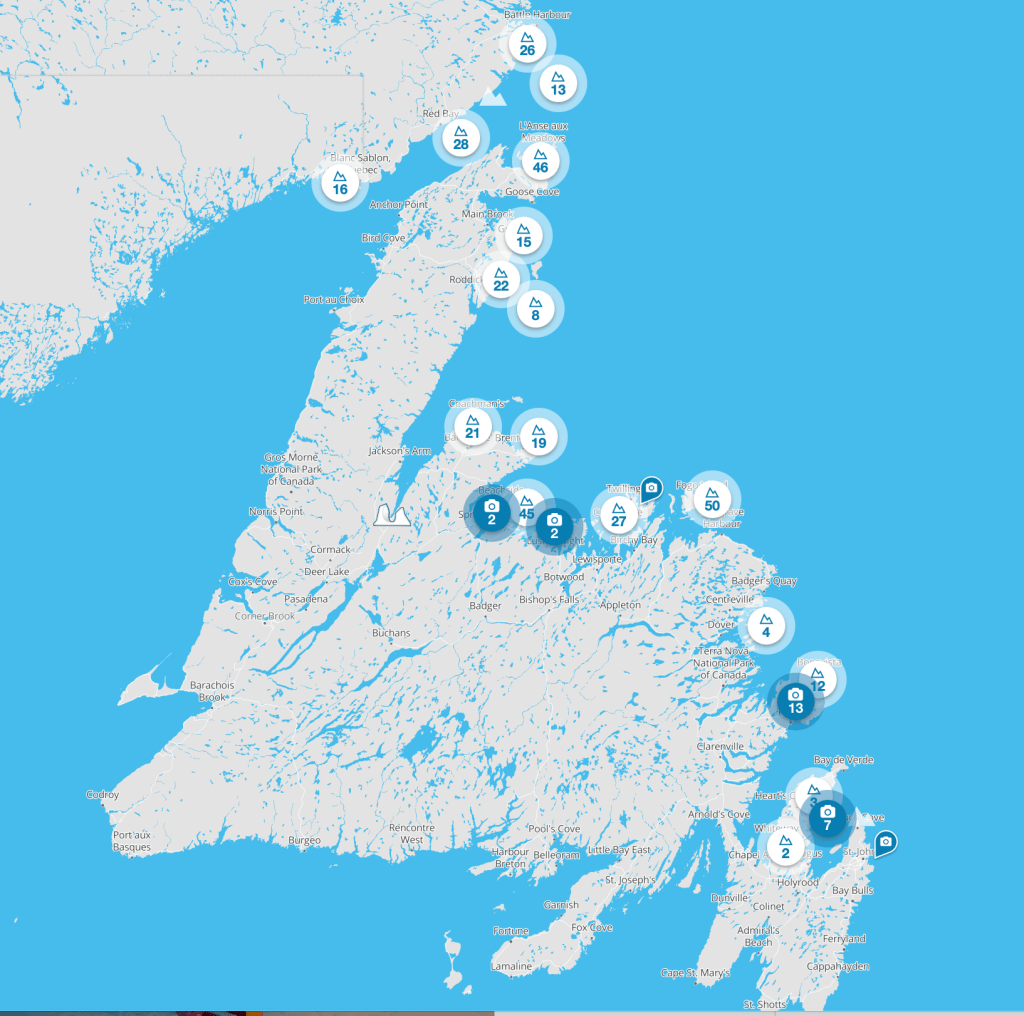

But we have hard time focussing on the shores as endangered areas by the disproportionately warming global ocean, overwhelmed by data that we are cognitively challenged to process. The late historian John Gillis warned us often of the danger of such assertive and short-sighted “turning one’s back on the sea”–and Gillis was worried that we had done so as a culture and society to our great detriment–rising ocean heat and sea surface temperatures remind us of the disproportionate amount of heat that has been absorbed in global oceans, and the danger of having remade the ocean as a vital habitat. For the shores have been unjustly ignored, as a space whose ecology we might do well to focus as sites suffering from anthropogenic change. We have a hard time focus on the vulnerability of the shores as ecosystems, indeed, so often do we see surging seas as a threat to human habitation of the shoreline, rather than having a broader sense of the threat to the ocean biome as a threat from largely anthropogenic warming. Yet as they are so vulnerable, and so potentially rich with significance as vital membranes of the planet. they are precisely where we must attend with greater atteniotn, as we try to parseunprecedented risks of overheating.

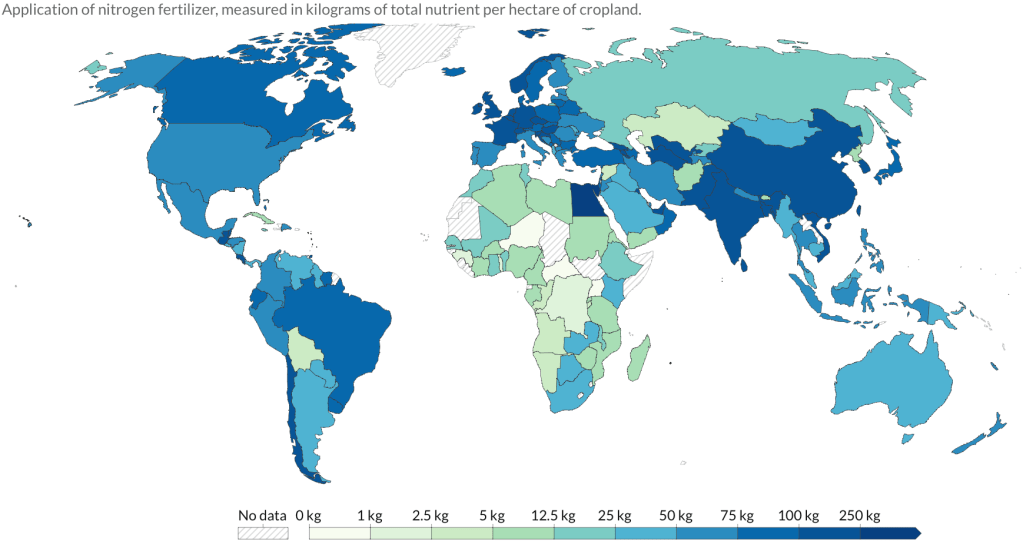

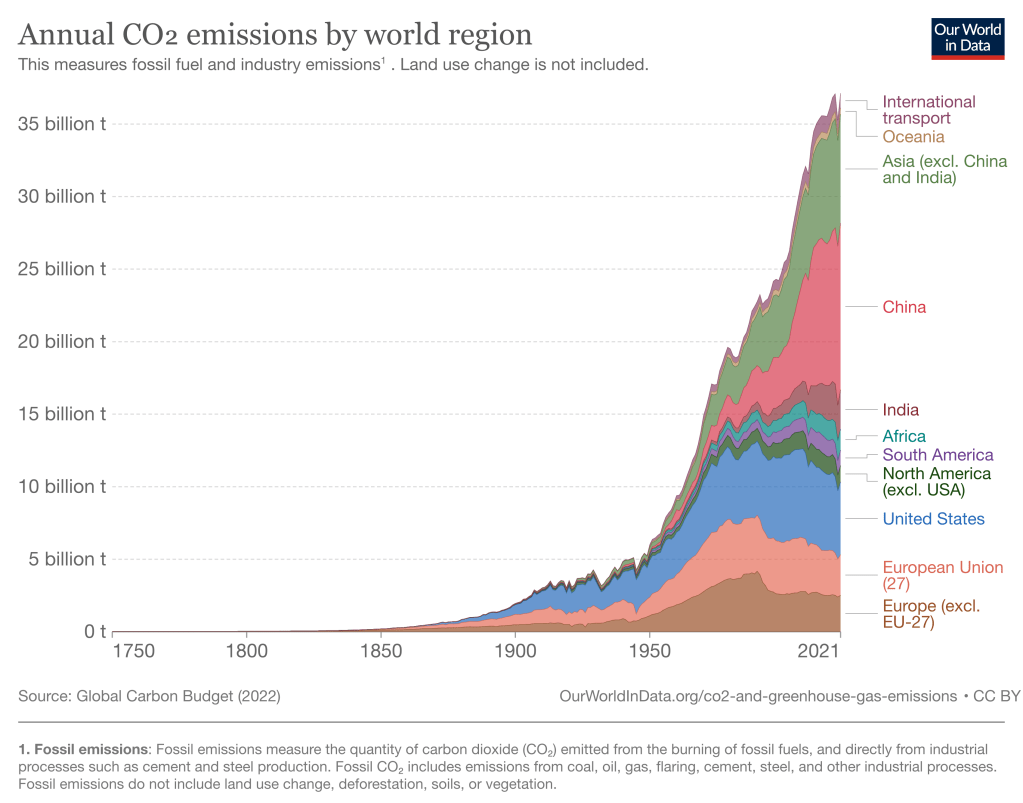

Even as country-based promises to reduce rates of carbon emissions became the talk of the town after the Paris Accords, with few imagining reductions likely for most of the developed world, before the United States withdrew from the global accord, which had pledged to cut 52.4 billion tonnes of emissions, on a global scale, little probability of the reduction to goals by the highest emitters–China; Western Europe (EU); Brazil; Canada; Japan–we face the global impact of planetary warming with few guideposts, precedents, or narratives to process catastrophic climate change.

We risk casting anomalies of surface temperatures and indeed looming rises in surface temperature as but the latest flattening of the world’s surface, eliding differences of land and sea temperatures that fails to come to terms with the cascading consequences and scale of anthropogenic climate change. For the most striking aspects of the rising surface temperatures on the planet may be the rising warmth of ocean waters. And the registering of global waters suggests, not paradoxically, both the liability of a focus of most mapping on the land–and extension of terrestrial coordinates to the oceanic surface, as if the anthropocentric claims of land maps might be extended, with brash or unwarranted assurance, into the ocean, without appreciation of the degree to which oceans have absorbed the great preponderance of anthropogenic heat: does an anthropocentric map of land effectively elide the extent of anthropogenic influences on global surface temperatures? Offering a private record to observe temperature variations that are remotely sensed, we may be foreclosing our relations to our own surroundings, and indeed of the relation of species beyond the human to the oceans as globally vital habitats.

But in mapping temperature rises as part of a continuation of land temperature anomalies, we may not grasp the full extent of the problem–and only risk entering into a climate apocalypse. So, indeed, runs the presuppositions implicit in the newly vaunted technologies of Direct Air Capture (DAC), the neo-liberal promise of carbon sequestration, by projects promising to capture carbon at the sites where it is produced that is being entrusted–bottled at the source!–that seven of the largest oil and gas companies are promoting as a public-private venture to “remove legacy emissions” even as the oceans warmed. For DAV is billed as the new mission of energy companies to use their existing infrastructure in offshore a reas to make good on the danger of the climate scenarios such maps threateningly propose, treating the recent promise of Direct Air Capture, if unproven, as a awaits public funds to “flow into the [existing energy] sector so it can scale,” with Occidental Petroleum floating promises to remove one million metric tons of CO2 every year by what is billed as a model for what the “best, most sophisticated, most committed companies” in the oil and gas businesses who are rooted in extractive industries should do “to preserve our industry over time.” Occidental Petroleum’s CEO is making a rather desperate argument as the nation’s energy companies have their backs up against the wall if they want to continue to emit more carbon, with carbon being the prime contributor to and accelerator of anthropogenic climate change.

For if its technology is unproven, it ostensibly or plausibly offers carbon-based energy companies an basis to sustain DAC can leverage a write-off able to balance out costs of future carbon emissions by using machines on the drawing boards to “pull carbon from the air” of unproven efficiency, erasing future costs of carbon burning, and overlooking the past costs of carbon emissions energy companies have themselves so conspicuously historically contributed.

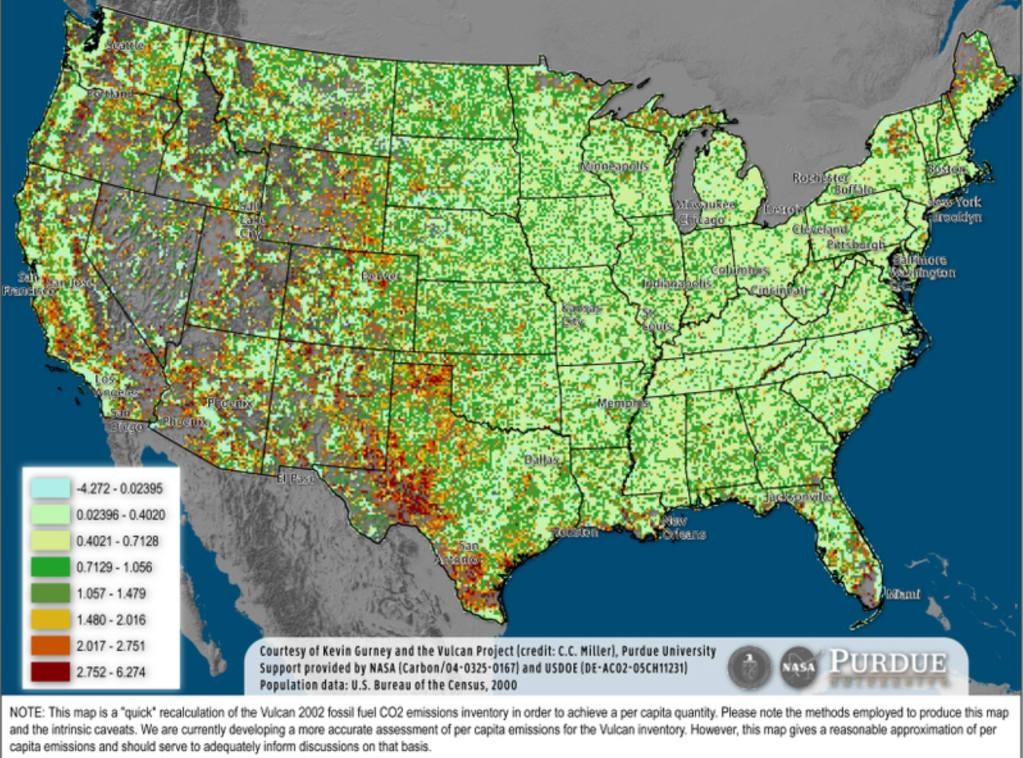

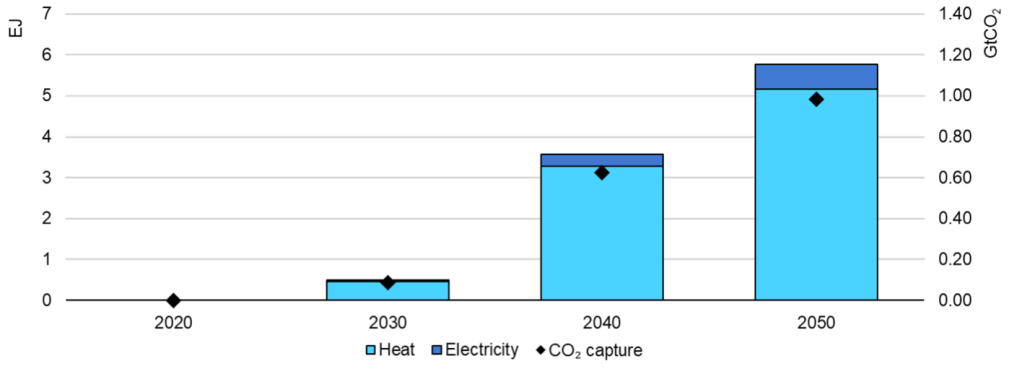

Fossil Fuel Emissions Inventory per Capita based on 2000 Census/Kevin Gurney and Vulcan Project, Purdue

The unproven technology uses the very tools of extractive industry to inject and store carbon in the earth’s surface, , creating a tool akin to double-entry bookkeeping to balance the costs of future energy develpment against the removal of carbon that may well in the end return to the earth’s atmosphere without ever needing to reduce emissions. “Direct Air Capture” is a new language of soft neoliberalism, fulfilling needs to acknowledge the untenable scale of costs of carbon emissions, but scaling up their own responsibilities to reduce emissions by promises to sequester carbon in underground reserves, of putting the greenhouse gases back where the oil was extracted years ago, and indeed filling up old empty oil mines with carbon reserves in the Permian basin. Although the largest DAC plant removes only 4,000 tonnes of CO2 from the air per year, the logic of an enormous growth of investing in technologies of Direct Air Capture plants could eventually and only by the middle of the twenty-first century extract a full gigaton of the carbon released into the atmosphere.

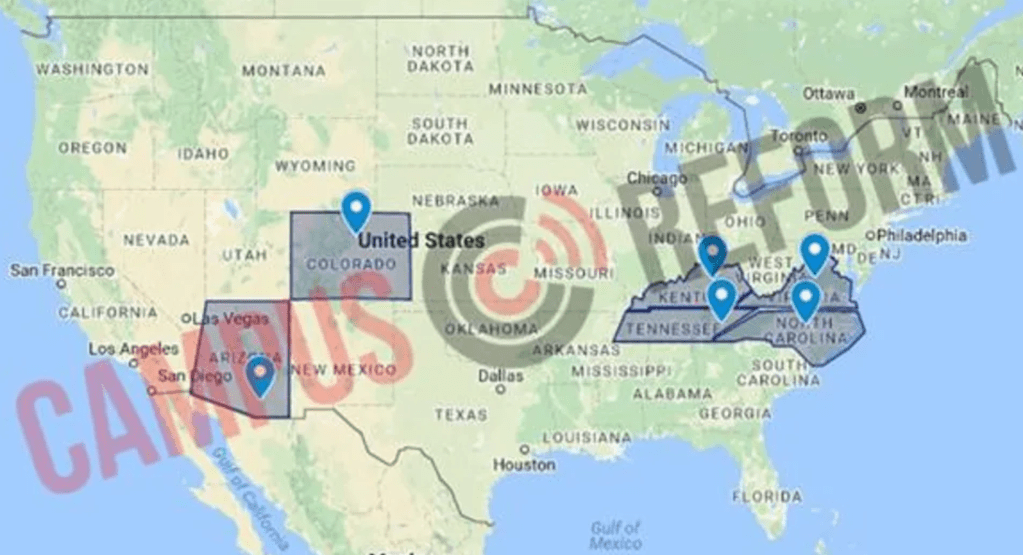

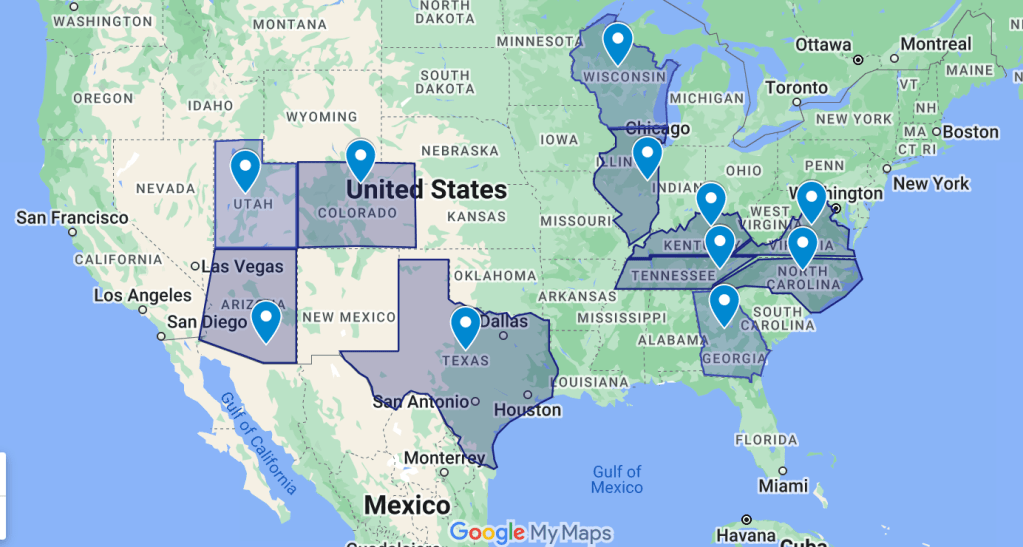

Proposed and Operational Direct Air Capture Facilities, 2018/Global CCS Institute

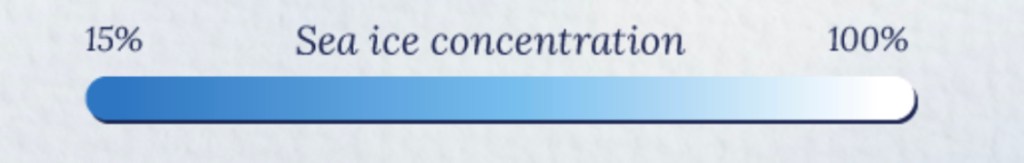

Global oceans have absorbed a preponderance of anthropogenic heat over the past seventy years– some ninety percent of excess heat that was trapped in the earth’s atmosphere since 1955–that makes them perhaps the clearest single register of the extent of anthropogenic contribution to climate change. Yet our monitoring of sea surface temperature adequate, based on a points, hinders rather than help the scale of climate change that is occurring in the global oceans. It is perhaps a hard pill to swallow, that cannot be sugar-coated, but the deep reds of temperature anomalies present a stronger picture than the levels of temperature rise of the planet’s surface, and its detail demands far more unpacking and deeper drilling into its detail, to use a poor metaphor, to unpack in satisfactory ways.

It is otherwise hard to grasp the alarm registered in the header to this post. The very land-based tools of mapping that have allowed us to track landcover and agricultural productivity by GIS overlays may have been far less helpful in grasping the scale and of the anthropogenic modification of global oceans–and the to grasp the changes in global oceans that will help to process or come to terms with the consequences and scale of rising sea surface temperatures, and the contribution of anthropogenic contributions to rising global temperature that are at risk of changing the global habitat and our relation to the surrounding world at the levels we demand to understand. Fort he very tools of geographic mapping are ones that arose in terms of mapping from the perspective of a state–effectively, of seeing like a state–that led us to understand land use, as much as anthropogenic change. Yet the state has sold increased offshore drilling rights to many oil companies, in ways that have set the stage for planning offshore Direct Air Capture plants in sites like the Gulf of Mexico, increasingly treated by 2018 as a pubic-private density of point-based drilling sites, even as sea temperatures rise. The network of old wells abandoned permanently and temporarily on lands that the the US Government leased to energy corporations suggest a basis for the encouragement of a man-made shoreline tied to an infrastructure of energy extraction by 2018 that was difficult to change or every fully separate ourselves.

Permanently or Temporarily Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells Leased in Gulf of Mexico, 2018/Enverus 2018, National Energy Technology Laboratory, Undated

GIS layers helped engineer the most effective site of carbon sequestration in offshore regions of the well-mapped geological terrain of the Gulf of Mexico, already crisscrossed by a density of pipelines for optimal sites for low-cost offshore storage of optimal geologic suitability, despite the existence of clear risks of locating extractive industries offshore beside a wetlands that bordered on a rich marine ecosystem that was delicately stuctured as a complex oceanic habitat. The reference points for storing are the cities where workers at the new plants would live–Mobile; Houston; Corpus Christi; Biloxi–rather than the ecologically delicate salt marshes, wetlands, and estuaries that are critical to shorebirds, and spawning sites for crayfish, oysters, shrimp, mink and alligators. The choice sites for subzero storage of the coast of Louisiana lie within the offshore continental shelf, as if an extension of territorial claims of the well-mapped underseas regions long studied by the energy industry.

Favorable Locations for Offshore Storage of Captured Atmospheric Carbon, 2022

This may be the fate of the pointilistically mapped seabed, a weirdly compromised cartographic flattening of the offshore. For the oceans–the very life-giving areas from which we arose, and on whose edges human society long lived–offer the clearest register of the anthropogenic image of human-caused temperature rise, although, perhaps paradoxically or more probably circularly, the deeply anthropocentric systems we have mapped or registered land by a point-based system may be inadequate to register the impact of rising sea surface temperatures on planetary health.

Change in Global Sea Temperatures in Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries (1901-2020)/EPA

–but how much our recent maps of marine monitoring are not evident as much in point-based registering of anomalies, but specific sites of ocean heat, with a troubling density off the coast of Japan, in the Persian Gulf, and in the Gulf of Mexico,as well as the Eastern Seaboard.

Marine Monitoring of Global Ocean Heat Trends, 2005-2019

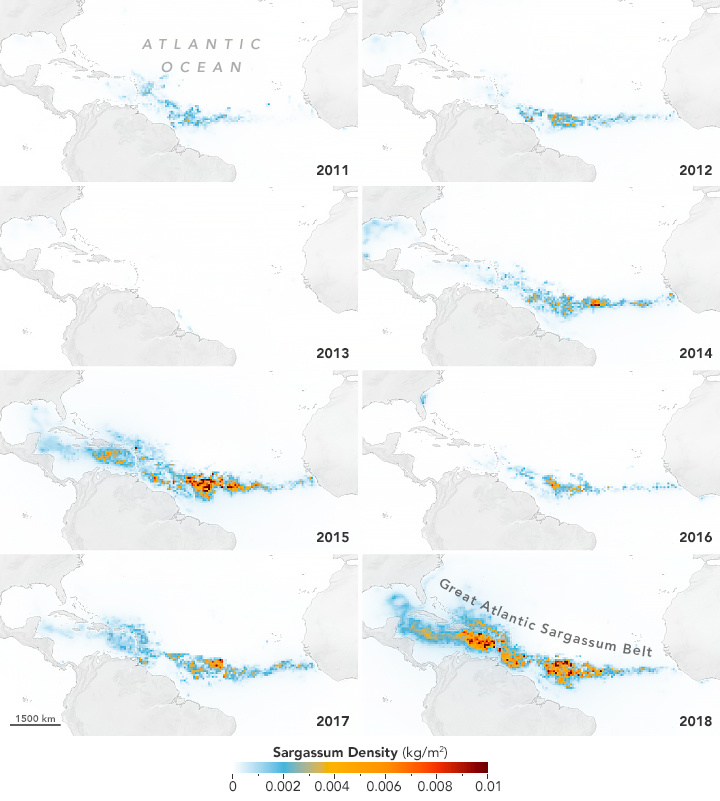

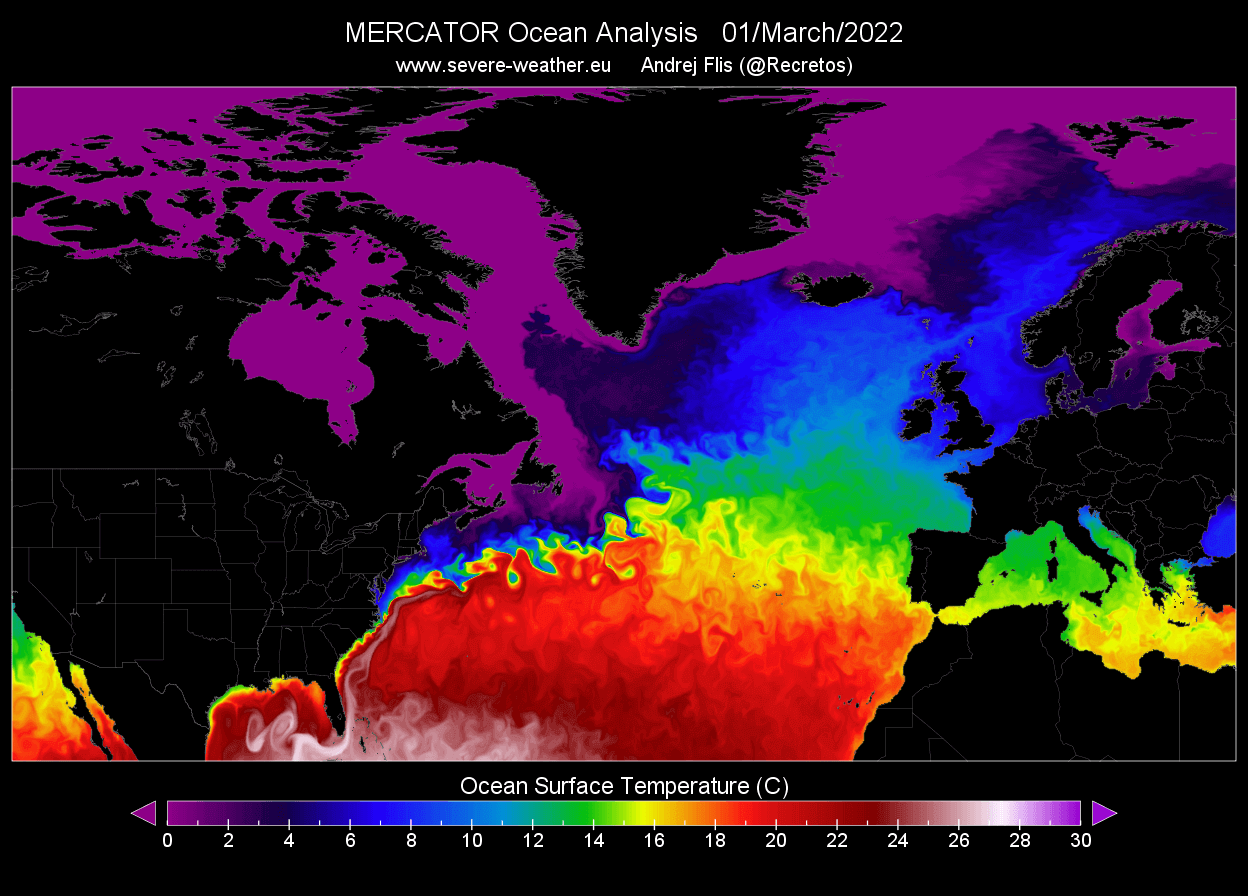

This contribution is difficult to map, or map to satisfaction as the result of human activities. But the stubborn nature of these deep carmine reds suggest, of course, a change that goes far beyond politics, and, if we might be glad for the light blue airbrushing on part of the Arctic Ocean and Greenland’s edge, the ice-free arctic and warming of antarctic ice shield seems much more terrifying signs of where we are headed, with a warming Atlantic–and Gulf of Mexico–a cause for alarm. If Canadian rock singer Neil Young dryly lamented in “Mother Nature on the Run” that 1970s would change the environment of the planet, his dreamy, druggy, hallucinogenic if anthemic call for help paralleled major breaks from the baseline of global temperatures. For from the postwar era through the 1970s, weather changes reveal the deeply disruptive nature of the global climate to which we are headed–and the step difficulties of visually communicating temperature anomalies. Were increasing surface temperature from 1900-2020 already hinting at the consequences of a failure to incorporate rapidly shifting temperatures farmers would faced by the late 1960s, in a 1970 album reflecting on how rising temperatures of the late 1960s and increased pollution created a powerlessness before a changing landscape, parallel to declining agricultural productivity?

If Young was not necessary a student of the Canadian Land Inventory, as a twelve year old set his sites to be an egg farmer–and to be a student of scientific agriculture at the Ontario Agricultural College to “learn to be a scientific farmer” after having tallied the improvised inventory of “Neil Eggs” as he organized sales of a chicken coop in close contact with Ontario farmers before listening to Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, and Elvis Presley replaced his raising chickens and selling eggs. The environmental anthem anticipates Young’s fierce opposition to factory farming since the mid 1980s, shunning venues serving foodstuffs from factory farms–venues “fed by factory farms.” But the oracular nature of the song covered by Patti Smith, after I’d written much of this blogpost, in Golden Gate Park, first made me wonder how the roots of the Canadian Land Inventory was unsuited to measure the changes in sea surface temperatures and indeed offer a meaningful narrative context for global temperature changes.

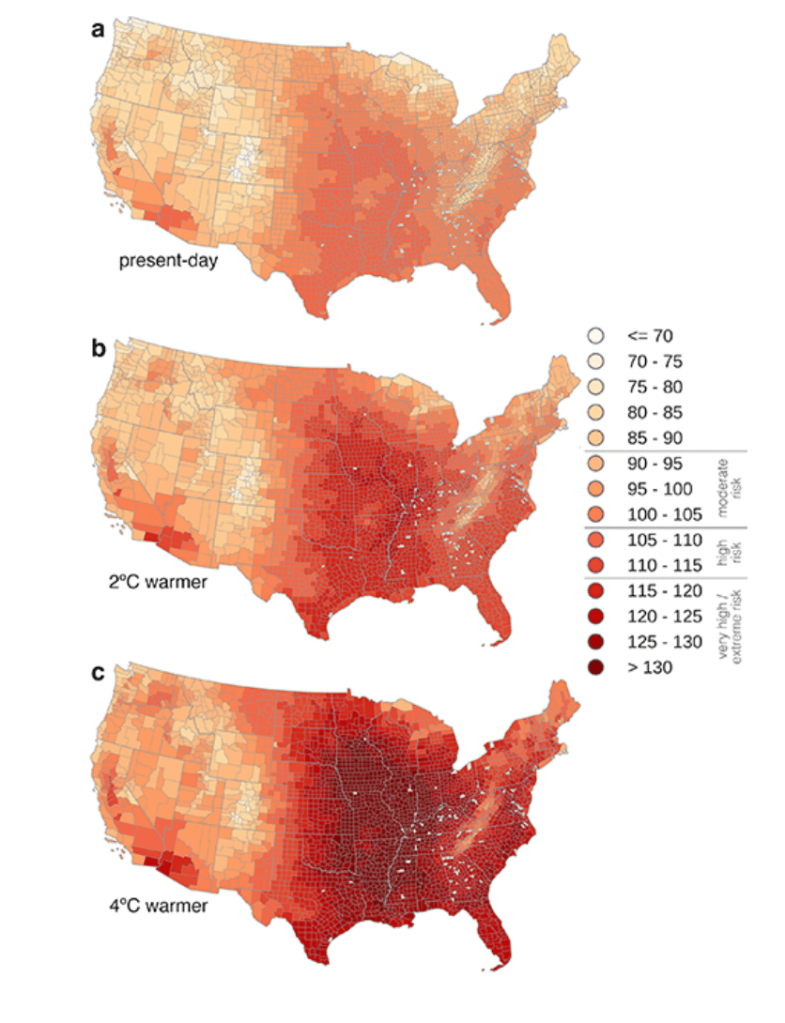

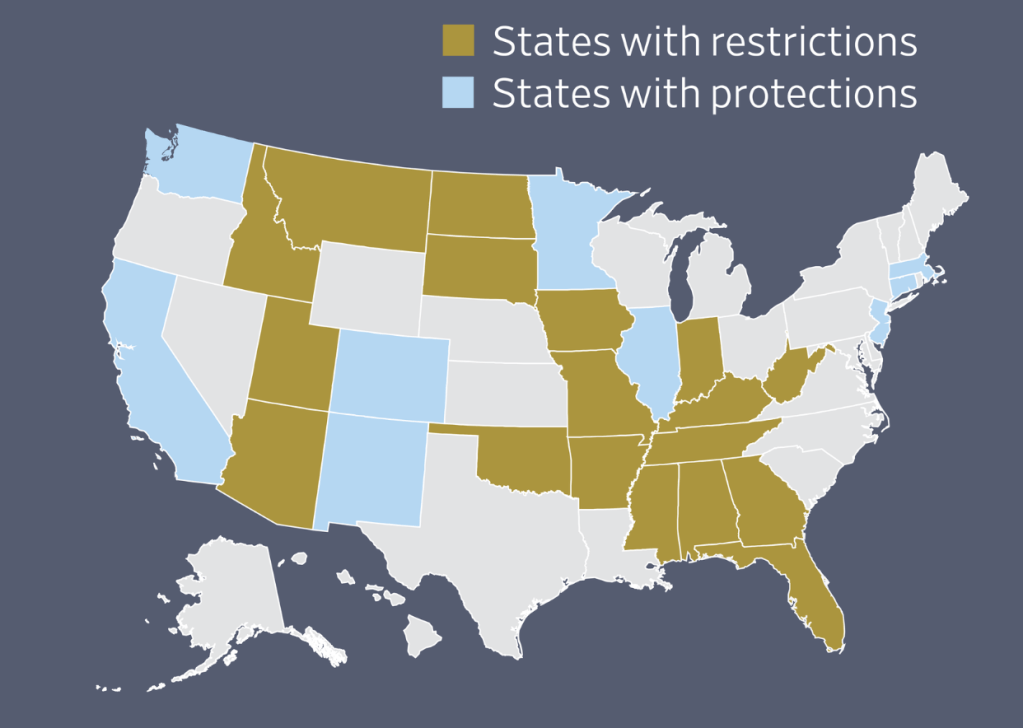

Extreme heat itself endangers farm workers–most U.S. farmworkers endure dangerous levels of heat three weeks of each year, beyond historical levels of heat exposure, growing to two months by the current century’s close per a recent study of the actual concentration of agricultural workers in America who will suffer from such a shift against the regions that are in upper quartiles for community resilience–suggesting the lack of abilities we will have to absorb or respond to such critical even if apparently “small” changes in temperature across the United States, shifting the productivity of farms in an era of climate change projected under different models or scenarios.

How to include people in the map, or how to include lived experience of other animals? We have perhaps all retreated into the comfort of our own buildings, retiring to contemplate rasterized images of modeled temperature changes in air conditioned rooms. The shifts in temperatures captured by eye-catching rasters offer limited narrative context to process such rapidly accelerating shifts of global surface temperatures. And if we presume to hope to “capture” carbon to turn back such rapid and unsustainable swings of surface temperatures in future years by continuing to allow carbon emissions, we are perhaps allowing ourselves to be the victims of cartographic distortions that fail to register the consequences of how oceans–in ways we have not fully been aware–have been absorbing up to 90% of anthropogenic global warming.

The arrival of July brought the warmest July on record–tempting a bitter riff on Stevie Wonder’s album by calling it “Hotter than Julys” about “making the earth a burning fire,” over a full degree centigrade–1.12°C (2.02°F)–above the 20th-century average of 15.8°C (60.4°F), raising questions of mapping anomalies meaningful, as the monitoring revealed a level of warming so beyond average that one might distinguish record temps warmest as something that the entire planet had not experienced, and that raises questions not only about the world, but our relations to the world–the Umwelt, that zoologists appropriated from idealistic philosophy at the turn if the twentieth century to acknowledge how different species used the senses to map external lived environments –that we are going to be forced to come to terms as our environments reached record heats.

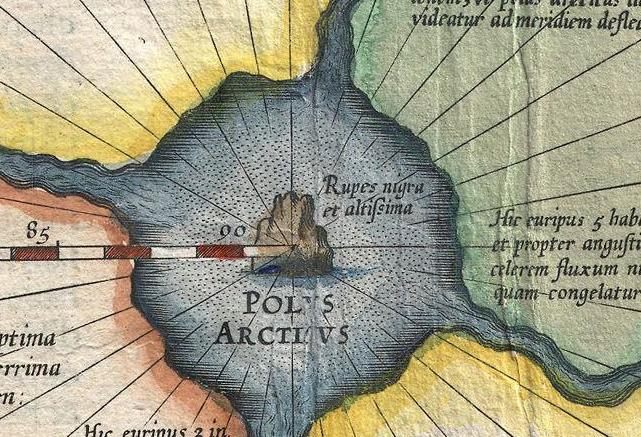

The agency of animals in perceiving the world is less the point of this post, however, than the radical accomodation of Umwelt that such record shifts in ambient land and sea temperatures pose–and how we can recognize and communicate them beyond simple color ramps. The recent record marine temperatures raise questions of the warming of sea surfaces, in fact, that demand to be distinguished as a reservoirs of heat we have perhaps poorly mapped in describing the land-sea continuity of maps–a continuity that was long heralded as a modern innovation of terraqueous cartography in the early modern world–that might be less helpful when it comes to grasping the effects of heating oceans and the rising sea-surface temperatures and oceanic heat waves remote sensing tools currently reveal.

Record Land and Ocean Temperature Percentiles in July, 2023/NOAA

The pinning of heat to pixels renders not political polarization, but even more toxic disturbances of equilibria of global temperatures–but an even more bracing problem of organizing our relation to a rapidly warming world. These quite literal heat maps paint a scary picture of the complex distribution of warming across land and sea over a century of of warming, synthesized from the first era of fairly uniform data in global temperature maps.

But are the rasters tracking warming able to communicate the imbalances of these significant anomalies of global warming by almost three degrees in some spaces of the global ocean–and some a few regions–an increase that follows the yearly rising of surface temperatures from just before 1980. This was the very time that Young–son of a prominent Canadian newspaperman who as a daily columnist for the Globe and Mail had a knack for reporting–was chronicling quite recent spiking in global surface temperatures before 1970 when Neil Young called our attention to the new scale of pressures we put on the planet, at what would be watershed of rising temperatures that only escalated over the next fifty odd years. By some odd coincidence that may not have been that odd, Canadian government began to monitor land-use management in ways that would lead to the formation of early geographic information systems, as Canadian geographer Roger F. Tomlinson began using aerial surveys–using large-scale photogrammetric maps–to create visual information forms bridging computers and geographic data. By collating data about wildlife, forestry and the census to increase agricultural productivity, Tomlinson offered new ways of seeing like a state rather than like a farmer, in ways that claimed a benefit for farmers and farms across Canada..

But data on resources was privileged beyond data on warming–“heat” was not even a category of inventorying land information in maps, at a uniform scale and overlay, in ways that allowed “layers” to be read overlapping factors on a basic dot-grid, able to incorporate census data, that would reduce the manpower for resource mapping beyond the capacities of actual staff. Canadian surveys amassed databanks beyond human abilities to assimilate an inventory of land-use information, able to store information in readily usable form in a computerized inventory of overlapping layers jto process the scale of information overload in maps of environent, land use, and productivity that humans cannot process or analyze in an instant library of statistics stored on tape, but not maps–even as any point on the earth’s surface “can be identified by numbers” to allow a synoptic inventory of land quality to devise new practices of land use.

Tomlinson coined of “Geographic Information Layers”–long before he joined ESRI, down in he San Bernardino Valley outside of Los Angeles on the Pacific coast–as a public respository of land use. The weighty term itself predates a century of rising heat, however, and its inventories largely bracketed temperature and the effects of heat waves’ differently deleterious effects on land and sea. The Canadian government was presented by Tomlinson as the landowner akin akin to a farmer forced to make decisions but who had “hasn’t got too much idea about the climate” or the water on his property he has just inherited, forced to make decisions about how to plant the right seed for his family. The very same questions, he explained in a classic CBC promotional short, were pressing to addressed both by the farmer who inherits a plot of land, but can be extrapolated to the nation’s management of millions of miles across Canada in an inventory.

The result that “the map has been converted into numbers” allowed readings of land quality at every hundred feet across the country, now readily accessed in hours, stored on tape on a grid aligning census tracts, water rights, and the fertility of the soil, placing jdata in the hands of decision makers in a public library of land. By replacing the human eye’s relation to landscape by an interface of soils, climate, topography, wildlife, forest capabilities and census tracts by subdivision in a profile of the nation, map layers were analyzed at multiple scales to zoom in on local land use at points and polygons,–

Saskatchewan’s Land Capaibility for Wildlife, Canadian Land Inventory (1976)

–merging files and coordinates of the Canada Land Inventory that have provided abasis for optimal land use and government investment that offered a tempting basis for similar inventory of the nature of atmospheric changes on a global scale. Yet a farmer’s local knowledge is different in feel and texture than the point-based layers Tomlinson optimistically advocated as a national mapping model–in ways that is not captured in the massive inventory that classified the land.

But the land use inventory presumed a stable definition of “nature,” that he current escalation of temperatures when Neil Young composed his anthemic song about Mother Nature being “on the run” as a fugitive or convict around 1970s, as temperatures started to rise yearly, shifting the crop yields in the data that Tomlinson measured for he Department of Forestry and Rural Development by stacking up layers that would align point-based data for cartographers’ benefit on any land-map.

Neil and his father Scott Young famously lived outside of Toronto, on an Ontario farm, and would have been aware of the Land Use Inventory, but also of the problems of a shifting sense of nature that it did not easily capture in its discrete point-based layers of information. Yet the rising surface temperatures of the late 1960s and later years that won a large and continued audience for Canadian guitarist Neil Young’s anthem in his first great solo record was rooted on working on a farm responded to the increasing anthropogenic nature of rapid temperature change–as much as the fears of nuclear apocalypse and technological advances–that inaugurated an escalation of above-average land temperatures through the first fifth of the twenty-first century far beyond what Young himself had feared or envisioned, difficult to reduce to but a single layer of a map.

Surface Temperature against Average (°C/NOAA, data: National Centers for Environmental Information

We are not cognitively attuned to imbalances, and dramatic departures from the status quo. If cognitive biases that lead us to prefer status quo relations where things remain the same are common basis for poor decision-making, the desire to prefer that things stay the same is an especially pernicious error in assessing the anthropogenic contribution to climate change: we allow ourselves to be seduced to maintain the status quo, to minimize risks, but have occluded the imperative and huge benefits of reducing the disruptive cascade of ecosystemic shifts of such consequence to be impossible to process in terms of the two-color schema of red and blue.

It is hard not to worry that the tools of registering such rapid shifts of surface temperatures offer a poor sense of our relation to the natural world–or help to clarify the rapid shifts in the biological of the world that will be and are experienced by other creatures. For the stark shifts of temperature changes map a misleading balance sheet of environmental change that is oddly distanced from the relation of organism to the planet, or a tally of benefits and costs that occlude the relation of organisms to the to the surrounding world, that should be the true centering of any understanding of climate change. The compromised relation to surrounding environments that the plotting of value in underground deep-sea energy reserves is a distortion privileging the point-based location of value, removed from the oceanic environment or critical dangers of warming waters of the global ocean waters. As the habitats of oceans shift in irreversible ways, the ability of creatures to relate to the world, or to perceive their surroundings, changes, and we are caught, as a deer in the headlights, without a clear way to grasp either the scale or effects of changes in the global ocean.

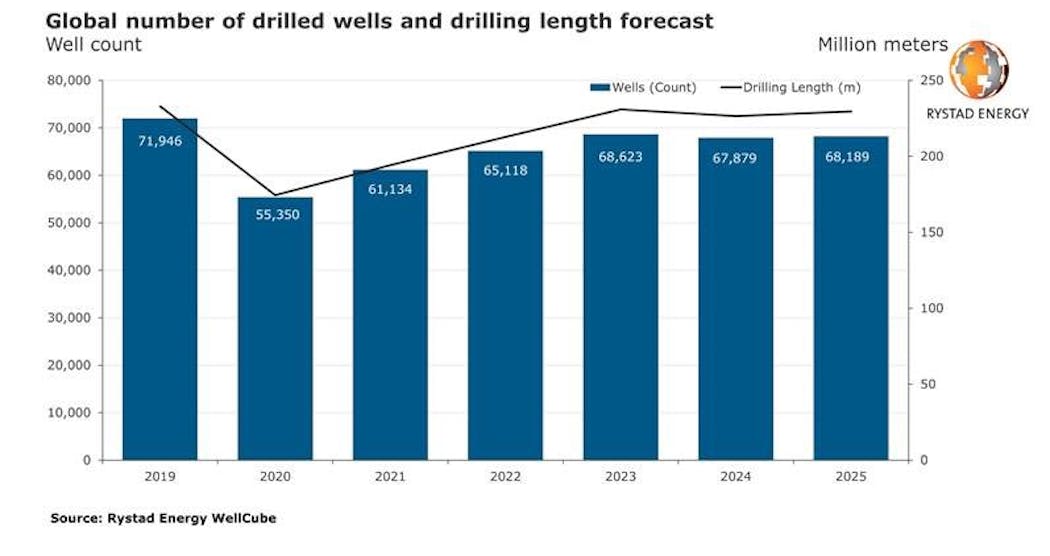

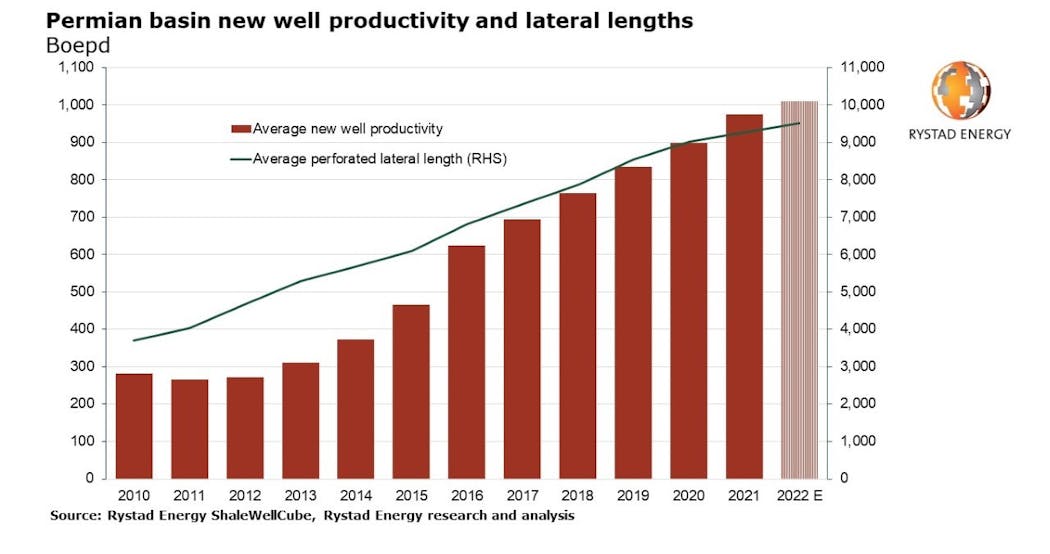

We trust we still have time to withhold judgment–as if fears of losses of once abundant petrochemicals can occlude an appreciation of potentially hugely favorable gains, driven by fears that declining oil prices might hinder profits to drill over 50-60,000 more new oil wells annually–

and as the expansion of inland drilling in the southwest’s Permian basin has continued to expand of every increasing depth, reaching unwarranted heights, driven by demand for profits and continued petrochemical security, driven by the illusion of an abundance of underground petroleum reserves. nd the increased depletion of near-shore wells that were drilled off the Louisiana coast in the Gulf of Mexico back in 1938 have led to the growth of an offshore archipelago of 3,500 platforms off the continental shelf of the United States, and along the continental slope, leading to a boom in wells under a thousand feed of water on federally leased land–deepwater and ultradeep rigs, whose risks challenge notions of environmental responsibility in a larger network of active gas and oil pipelines, processing plants and offshore structures in leased lands on the outer continental shelf.

New Wells Drilled Annually in Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico

Perhaps we have little clear ways of registering the scale at which anthropogenic contributions add to the warming of the global ocean, or of planetary seas. We have no clear basis to represent this growing contribution, let alone to narrativize or narrate our own relations to the rapid acceleration of climate change and its multitude of consequences of a warming world. Our maps are not at fault, but have their limits as they reify the conditions we live in–rather than our contribution to them, whose specter is perhaps all too evident in the world’s largest gulf, a marginal sea of the Atlantic whose seaward boundaries provide one of the greatest challenges of coastal management.

The Gulf of Mexico is itself an anthropogenic space, where’s the seamless bridging of land and sea: as well as a proof-of-concept of liabilities of mapping a continuity of land and sea by leasing of federal lots for platforms for extracting oil and gas of increasing depth, far deeper than five to six thousand feet below sea-level. The expansion of deepwater mapping has grown dramatically since 2000, by energy companies growth eager to match demand for gas and oil as abundant in “national” waters; the government is eager to license to ensure the ability to “keep” energy prices down. If the current plans to invest billions in unproven tools of “direct air” carbon-capture promises a reduction of greenhouse grasses and new commitment of industry to greening, by “vacuuming” emissions at their source,” that would allow us to address the “carbon problem” with no change in our consumption of fossil fuels. Even as it promises of erasing the onerous emissions are unproven the promise to allow carbon dependence is widely promoted by energy companies: public funding of Carbon Capture and Sequestration would sanction the continued expansion of the largest offshore energy infrastructure in Texas and Louisiana, and boast the adoption of the best mapped geological region to sequester captured carbon for 559 BN metric tons of carbon storage.

Offshore Carbon Sequestration in the Gulf of Mexico/Helen G. Prieto

The promise of investing public funds in a boondoggle of corporate “greenwashing” is promoted as the “evolution” of a new American landscape of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), by subsidizing Occidental Petroleum to build corporate-sized “direct air” carbon capture and storage plants ready to imagine as a a new national infrastructure dedicated to construct “hubs” of carbon capture to be piped to “injection” sites where it might be stored or “sequestered.” Planned carbon “sequestration” projects are paired with green-lighting bids for offshore sequestration on federal lands lying in one of the most studied geological basins and potential sinks, the Gulf of Mexico–a site of expansive offshore energy infrastructure that is currently promoted as “the largest volume regional geological sinks in the United States for large-scale Carbon Capture and Sequestration.” The region that has a large number of depleted oil fields, already owned or leased by energy companies, essentially, is promoted (and extrapolated) as a bonanza of Gigatons of carbon storage.

The continued mapping of the man-made offshore environment of the Gulf of Mexico is plotted as a prime site to capture of carbon. The transformation of the Gulf of Mexico to a site of future carbon storage fulfills a fantasy of absorbing fossil fuels’ pollution from the skies without reduced dependence on petrochemical fuels, detracting attention from the very edges of marine habitat oil and gas extraction threatens. The very premise of “Direct Air Capture” takes eyes of the maps of global warming and many modeling of the effects of ocean warming.

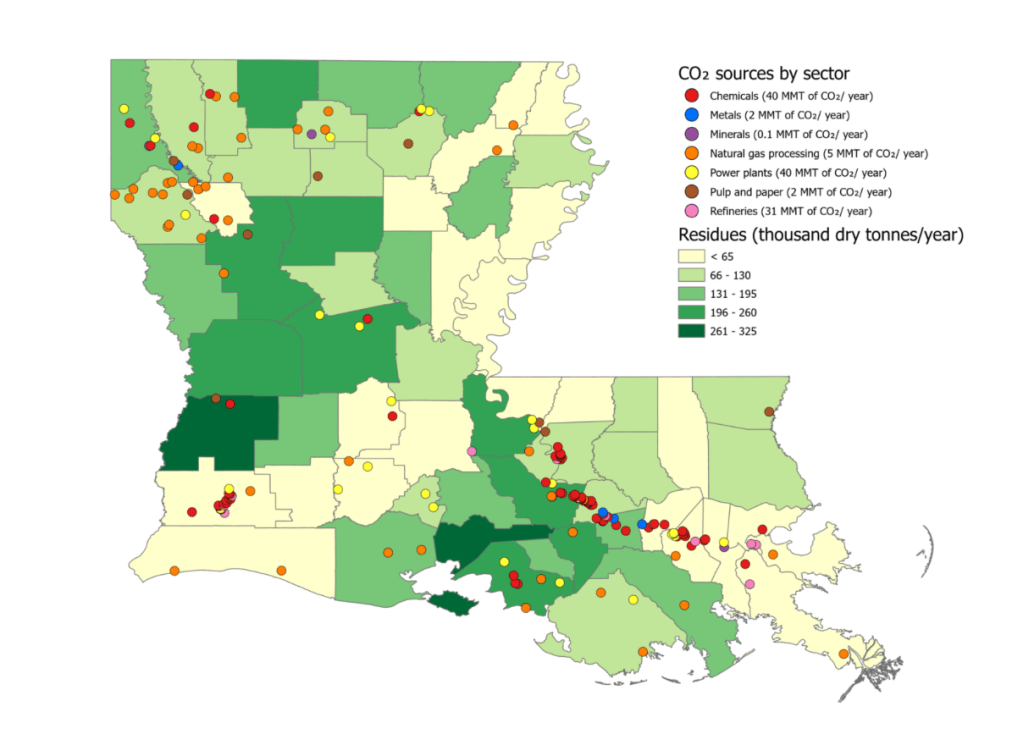

Proposed “Direct Air Capture” plants would imitate the very functions performed by the very coastal ecosystems–salt tidal marshes; kelp ecosystems; and even the open ocean–or are argued to do so on a broader scale than the sequestering and absorbing of one to two tons of carbon per hectare in existing salt tidal marshes, or the Florida Everglades, whose mangroves and peat soils have huge carbon stocks, and carbon sinks valued at $3 billion, if reduced by pollution and climate change. Spending over $6 billion in carbon capture projects along the Louisiana coast to sequester the carbon produced at refineries, making the state’s coastline into the carbon capture capital of the American South–but suggest the abstraction of costs and balances of carbon in maps of unproven possibilities of capturing carbon across the state, even as ocean temperatures rise at rapid rates.

Industrial CO2 Emitters against Potential Biomass Residue Availability/Carbon Mitigation Initiative